zh-TW

在導航的名稱

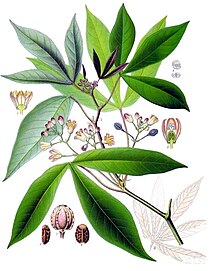

Die broodwortel word verkry van die broodwortelplant (Manihot esculenta) en is veral in die tropiese lande ʼn belangrike voedselbron. Dit word ook kassawe of maniok genoem. Die wortels bevat baie water en stysel, maar min eiwit, min vitamiene en byna geen vette nie. Dit word hoofsaaklik gebruik vir die setmeel daarin, waarvan onder meer brood gebak kan word.

Die broodwortelplant is houtagtig en het handvormige blare wat diep ingesny is en meestal uit 5 tot 7 lobbe bestaan. Die setmeel of stysel word in die wortels opgegaar. Die plant aard die beste in ʼn warm, vogtige klimaat, veral tussen ongeveer 30˚ NB of 30˚ SB. Die temperatuur moet verkieslik hoër as 10˚ wees en die reënval kan wissel tussen 500 tot 5000 mm per jaar. Die volwasse plant is redelik droogtebestand. Broodwortelplante kan in uiters arm grond groei en steeds ʼn redelike oes lewer.

Hulle word normaalweg nie volgens vasgestelde seisoene geoes nie, maar volgens voedselbehoeftes benut. Die groeiperiode is gewoonlik van 6 tot 12 maande, of kan strek tot 18 maande, wanneer dit die beste setmeelproduksie lewer.

Die plant stam uit Sentraal Amerika en uit Brasilië. Die Portugese het reeds in 1494 daaroor geskryf en het dit in die 16de eeu in Afrika ingevoer. In Asië het dit eers in 1835 bekend geword, maar in die tydperk 1919-'41 is 98% van broodwortelmeel op Java geproduseer.[1]

In sommige tropiese gebiede het die broodwortels as gevolg van die geweldige toename in die bevolkingstal die stapelvoedsel geword. Dit het belangrike graangewasse, soos byvoorbeeld rys, vervang en kan wanvoeding veroorsaak as daar nie aanvullende kosse by die dieet gevoeg word nie. Die broodwortel het nie naastenby die voedingswaarde van graan nie en kan met uitsluitlike inname eiwitvlakke gevaarlik laag laat daal. Die jong blare kan egter as ʼn groente gebruik word omdat dit ryk is aan eiwit.

Vir menslike inname moet spesiale voorsorg getref word voordat die broodwortel geëet word. Die wortels bevat 'n sianogeen-glukosied, wat onder die invloed van ʼn sekere ensiem blousuur (HCN) vorm. Die gifstof kan verwyder word deur die wortels te rasper, dit te laat gis en daarna te verhit. Deur dit net te kook, kan die ensiem vernietig word, hoewel dit dan nog glukosied bevat, wat op sigself egter nie giftig is nie. Die belangrikste lande waar die broodwortel gekweek word, is Brasilië, Indonesië, Nigerië, Demokratiese Republiek van die Kongo, Thailand, Indië en Burundi.

Behalwe vir menslike gebruik word die wortels ook as veevoer verwerk en dikwels in die vorm van gedroogte korrels na ander gebiede uitgevoer. In Suid-Afrika word die broodwortel gekweek vir die bereiding van tapioka, ʼn korrelrige meelstof wat onder andere in nageregte gebruik word. [2]

Die broodwortel word verkry van die broodwortelplant (Manihot esculenta) en is veral in die tropiese lande ʼn belangrike voedselbron. Dit word ook kassawe of maniok genoem. Die wortels bevat baie water en stysel, maar min eiwit, min vitamiene en byna geen vette nie. Dit word hoofsaaklik gebruik vir die setmeel daarin, waarvan onder meer brood gebak kan word.

Manihot esculenta, llamada comúnmente yuca,[1] ya internacionalmente reconocida como mandioca, tapioca, guacamota (del náhuatl cuauhcamohtli en Méxicu), casabe o casava, ye un parrotal perenne de la familia de les euforbiacees estensamente cultiváu en Suramérica, África y el Pacíficu polos sos tubérculos con almidones d'altu valor alimentario.

La yuca o mandioca ye endémica de les rexones con clima tropical de Bolivia, Brasil, Colombia, Ecuador, Méxicu, Panamá, Perú, República Dominicana, Puertu Ricu, Venezuela, Costa Rica, y Paraguái y foi cultiváu con gran ésitu en naciones africanes de similares condiciones climatolóxiques, y anque s'envalora que les variedaes güei conocíes son efeutu de la seleición artificial, hai variedaes xeneraes pol aislamientu xeográficu de la selva (casabe, que ye altamente venenosa) al de los altiplanos (yuca, mínimamente venenosa).

La mandioca ye un parrotal perenne qu'algama los dos metros d'altor. Ta afecha a condiciones de la zona intertropical, polo que nun aguanta les xelaes. Rique altos niveles de mugor —anque non anegamiento— y de sol pa crecer.

Reproduzse meyor de fraes que por grana nes variedaes anguaño cultivaes. La crecedera ye lentu nos primeros meses, polo que'l control de yerbes ye esencial pa un correctu desenvolvimientu. Nel so usu normal, la planta entera se desarraiga al añu d'edá pa estrayer los raigaños comestibles; si algama mayor edá, el raigañu endurecer hasta la incomestibilidad. De les plantes desarraigaes estrayer los retayos pa la replantación.

El raigañu de la mandioca ye cilíndrica y oblonga, y algama el metro de llargu y los 10 cm de diámetru. La pulgu ye dura y maderiza, y incomestible. La magaya ye firme ya inclusive dura enantes de la cocción, derrota por fibres llonxitudinales más ríxides; bien rica en hidratos de carbonu y azucres, aferrúñase rápido una vegada desprovista de la corteza. Según la variedá, pue ser blanca o amarellentada.

La evidencia más antigua del cultivu de la mandioca provién de los datos arqueolóxicos de que cultivar nel Perú fai 4.000 años y foi unu de los primeros cultivos adomaos n'América.[2]

Les siguientes referencies como al cultivu de yuca provienen de la cultura maya, fai 1.400 años en Xoya de Cerén (El Salvador).[3] N'efeutu, recién investigaciones tienden a demostrar que'l complementu alimentario de los mayes, el que-yos dexó sostener poblaciones bien numberoses, sobremanera mientres el periodu clásicu, y bien particularmente na rexón sur de Mesoamérica onde se concentraron importantes ensames (Tikal, Copán, Calakmul), foi la Manioca, tamién llamada Yuca, un raigañu con altu conteníu calóricu del que se preparar una farina bien nutritivo, en forma de torta redonda, llamada "casabe", qu'hasta la fecha ye parte importante de la dieta nes diverses poblaciones que viven na rexón maya y tamién na cuenca del Mar Caribe, cuantimás na República Dominicana y Venezuela y cuba[4]

Otra especie, la Manihot esculenta, anicióse posiblemente más al sur, en Brasil y Paraguái. Col so mayor potencial alimenticiu, convirtiérase nun alimentu básico de les poblaciones natives del norte de Suramérica, sur d'América central, y les islles del Caribe na dómina de la llegada de los españoles, y el so cultivu foi siguíu colos portugueses y españoles. Del estractu líquidu llógrase l'almidón pa planchar les ropes. Les formes modernes de les especies adomaes pueden siguir creciendo nel sur de Brasil.

En Paraguái anguaño la mandioca ye una de les especies más consumíes polos habitantes (sobremanera nes zones rurales, onde'l so consumu per cápita ye unu de los más elevaos del mundu),[5] y puede tar presente na mayoría de les comíes del día (nel almuerzu, media mañana, xinta y cena), sía fervida, frita o en platillos a base del so almidón. Coles mesmes, en munchos llares acompaña tolos díes a la comida principal (función similar al que n'otres partes cumple'l pan),[6] y alimenta al ganáu bovino. Nesti país cultívense como 300 variedaes de la mesma.[7] Los paraguayos llamar principalmente pol so nome en guaraní, Mandi'o.

Anque hai unes cuantes especies selvaxes de mandioca, les variedaes de Manihot esculenta son escoyíes pol ser humanu pa l'agricultura.[ensin referencies]

La producción mundial de la mandioca ta envalorada en 184 millones de tonelaes en 2002, la mayoría de la producción alcuéntrase n'África, onde crecen 99,1 millones de tonelaes, 51,5 n'Asia y 33,2 n'América Llatina.

En munchos llugares d'América, la mandioca ye l'alimentu básico. Esto traduzse nel abondosu usu d'imáxenes de la mandioca usaos nel arte de Perú pola xente de la cultura Moche quien la representen de cutiu na so cerámica.[8]

La presencia d'elementos cianogénicos, como por casu la linamarina nel raigañu, fai que la mesma sía inutilizable y venenosa en delles variedaes, ensin una enllargada cocción, necesaria amás p'amenorgar la rixidez de la magaya. Anque la variedá llamada Manihot aipi (considerada dacuando una subespecie de M. esculenta) contién concentraciones elevaes d'elementos venenosos, estos sumen al fervela.

Alternativamente, el raigañu puede arrallase en crudu, dempués de lo que ye prensada pa estrayer el zusmiu potencialmente tóxico (que contién ácidu cianhídricu - HCN). Una vegada ensugada al fueu o al sol, moler pa llograr una farina fina y delicada de la que se llogra, por sedimentación, l'almidón de mandioca y de ésti llógrase la tapioca, tamién llamada casabe. Por aciu esti procedimientu fáense comestibles inclusive les variedaes "amargoses" que tienen altu conteníu de toxines. Ciertes cultures africanes maceran el raigañu n'agua hasta la so fermentadura pa esaniciar les toxines enantes d'ensugala y molela.

El raigañu frescu tien de consumise nun plazu curtiu, yá que por cuenta del so altu conteníu d'almidones descomponse rápido pola aición de diversos microorganismos. Conxelada o envasada al vaciu caltiense mientres meses en bon estáu.

La mandioca utilízase estensamente na cocina llatinoamericana. Les variedaes dulces peracábense llargamente fervíes, o frites como sustitutu de les pataques.

Pa la so preparación n'alimentos, la mandioca someter a dellos procesos d'escaldiáu, ebullición, y/o fermentadura[9] Exemplos de productos alimenticios a base de yuca inclúin al garri (turraes los tubérculos de la yuca), fufu (similar a l'avena p'almuerzu), la masa d'agbelima y la farina de yuca.

Na mariña d'Ecuador la yuca ye bien típica en platos costeños, de los cualos destaca'l "encebollado", onde la yuca ye un elementu principal, acompañar con pexe (albacora, bonitu o atún) nun caldu especial, y tamién s'acompaña con verde fritu (chifles) llimón, aceite, ají y pan.

En Brasil la farina (farofa) emplegar pa entestar guisos o turrada direutamente sobre una plancha. La feijoada, un ensundiosu cocíu de gochu y fabes negres, acompáñase davezu con farofa tostada. Otros platos empleguen el raigañu, como la vaca atolada, en qu'ésta se cocina hasta eslleise nel caldu. Fervida y pisada hasta faer un puré emplegar pa postres.

Na cocina de Paraguái y na del nordeste arxentín, la fécula o almidón de mandioca entemecer con quesu y lleche pa faer bollitos enfornaos llamaos chipá, el tentempié más habitual de la rexón, o s'utiliza pa dar consistencia a guisaos de carne y verdura como'l mbaipy y el borí borí (vorí vorí) o como mbeyú (mbejú) o como caburé. El raigañu de la mandioca o yuca cómese fervida como acompañamientu de les comíes, a manera de papes (pataques), emplegar frita sola o con güevos (mandi`o chyryry). Ye tamién ingrediente principal na ellaboración del lampreado o payaguá mazcada. Tamién nel nordeste arxentín, la mandioca fervida sustitúi casi siempres a les papes.

Nel estáu de Tabasco, en Méxicu, prepárase una comida llamada pucheru, que contién carne y verdures mesmes que se dexen ferver, hasta que la yuca allandiar, de lo cual resulta un caldu bien apreciáu.

Nel estáu de Yucatán, en Méxicu, prepárase un postre que consiste en ferver mientres casi un día enteru la yuca en miel d'abeya; anguaño úsase azucre, pa la cocción utilízase lleña en llugar de faelo n'estufa. Podría dicise que son yuques en almíbar.

Na gastronomía de Puertu Ricu la yuca usase en dellos platos. En forma fervida ye un acompañante característicu del arroz con habichuelas o al escabeche; tamién se preparar frita, acompañada de mueyo. Al igual qu'otros países y rexones, acostúmase tamién faer casabe y otros panes. El mayor usu ye arrallada, en forma de masa pa llograr les alcapurrias frites y los pasteles fervíos de yuca.

Na gastronomía del Perú la yuca usase en numberosos platos. En forma fervida ye un acompañante característicu del cebiche; tamién se preparar frita, acompañándose col mueyu de la papa a la huancaína; na zona norte del Perú, mayormente en Piura y Lambayeque, prepárase un piqueo con base en yuca machucada conocíu como mayáu de yuca. Na Amazonia peruana la yuca tamién s'emplega como insumo pa preparar el masato, una bébora alcohólico indíxena, amás prepárase farina que s'utiliza en sopes y na preparación de panes. Abraham fariña que s'utiliza na preparación de refrescos, como'l shibé, tortielles, frituras, postres, como'l aradú, preparáu con güevu de pita o tortúa fluvial y otres combinaciones. Ente los platos típicos qu'utilicen la yuca ta'l picadiellu de majaz, chicharrón de llagartu y otros platos exóticos de la gastronomía de la Amazonía peruana.

En Venezuela y na República Dominicana utilizar pa preparar el casabe, una torta plana de farina de yuca, producida a partir de les variedaes amargoses, el casabe foi fechu primero polos aboríxenes. Tamién s'utiliza en Venezuela pa preparar buñuelos, dulces llamaos naiboes y como acompañante de la carne o pollu en caricotes (fervida o frita) ya inclusive forma parte del popular sancocho.

En Cuba prepárase fervida en cachos, que depués s'unten con un mueyo d'ayu machucáu y naranxa agria (o llimón), y dempués arrámase-y mantega (grasa) de gochu llimpia y bien caliente, sal al gustu. Nel oriente del país tamién se preparar el casabe, como más arriba descríbese.

En Colombia usase pa preparar enyucaos o carimañolas, casabe, pandeyuca, pastel de yuca, yuques remexaes, palitos de yuca, ajiaco, sancocho, pandebono o como acompañamientu de carnes. Ye importante señalar que la yuca ye un alimentu sagrao pa les cultures indíxenes que s'atopen allugaes na Amazonía colombiana, onde se conocen más de 10 especies, ente esa la yuca brava que ye venenosa pero qu'estes cultures pol so gran conocencia llograron procesala de tal manera que d'ella saquen bebíes, fariña y casabe ente otros.

En Panamá usase pa la preparación de carimañolas, bien típiques de la cocina panameña, tamién se consume sancochada con cilantro al mueyo, frita, mayada y como ingrediente del sancocho.

La fermentadura de la yuca produz una bébora llixeramente alcohólico llamada cauim, consumida con propósitos rituales polos pueblos aboríxenes.

Na actualidá vienden presentaciones de yuca frita en fueyuques, similar a los papes.

N'Hondures, en Nicaragua y n'El Salvador esiste un platu típicu conocíu como yuca con chicharrón, similar al platu cubanu de yuca al mueyo. Prepárase fervida en cachos y sírvese con rula de gochu con carne frito (chicharrón), sobre la yuca. Finalmente amiéstase-y un mueyu de tomate cocíu, al que se-y pueden amestar pequeños cachos de tomate, cebolla, chile duce o pimientu verde. Resulta un platu espectacular y delicioso. Quien asina lo deseyen amiésten-y picante a la mueyu de tomate o-y ponen mueyu picante al platu yá preparáu. En Nicaragua a esti platu denominar Vigorón.

La yuca ye la séptima mayor fonte d'alimentos básicos del mundu. Dalgunos calificar de "base de la vida" tropical, porque ye una de les más importantes fontes d'alimentación n'estenses árees de los trópicos. Ye un cultivu apreciáu pol so fácil y amplia adaptabilidá a diversos ambientes ecolóxicos, el pocu trabayu que rique, la facilidá con que se cultiva y la so gran productividá. Puede espolletar en suelos pocu fértiles, en condiciones de poca pluviosidá. En condiciones óptimas la yuca puede producir más caloríes alimenticies por hectárea que la mayoría de los demás cultivos alimenticios tropicales. Anguaño ye un cultivu con altes mires pa la producción d'etanol y prevese una crecedera espectacular na implantación d'esti cultivu.[10]

Producción en tonelaes. Datos 2003-2004

Fonte FAOSTAT (FAO)

En pruebes de llaboratoriu determinóse que'l pulgu secu de yuca somorguiada n'agua se rehidrata hasta 160 per cientu del so pesu en 25 minutos [ensin referencies]. Demostróse que'l pulgu secu de yuca absuerbe en promediu 120 per cientu del so pesu d'agua de mar [ensin referencies]. Esta agua nun ye salobre y ye apoderada pa usu agrícola. El pulgu secu de la yuca puede ser un modelu estructural pa llograr un productu qu'absuerba agua de mar pa usu agrícola.

La yuca contién cantidaes pequeñes pero abondes pa causar posibles molesties de sustances llamaes linamarina y lotaustralina. Estos son glucósidos cianogénicos que se converten n'ácidu prúsico (cianuru d'hidróxenu), pola aición de la enzima lanamarasa, que tamién s'atopa presente nos texíos del tubérculu.

La concentración del ácidu prúsico puede variar de 10 a 490 mg/kg de tubérculu frescu. Les variedaes de yuca "amargosa" contienen concentraciones más altes, especialmente cuando estes cultívense en zones grebes y en suelos de baxa fertilidá. Nes variedaes llamaes "dulce" la mayor parte de les toxines atopar nel pulgu. Dalgunes d'estes variedaes poder hasta comer crudes dempués de pulgales - como si fueren cenahorias. Sicasí en munches de les variedaes más frecuentemente cultivaes, que son amargoses, la toxina tamién se topa presente na carne feculenta del tubérculu, especialmente nel nucleu fibrosu que se topa nel centru.

Los tubérculos de yuca tamién contienen cianuru llibre, hasta'l 12% del conteníu total de cianuru. La dosis letal de cianuru d'hidróxenu ensin combinar pa un adultu ye de 50 a 60 mg, sicasí la tosicidá del cianuru combináu nun ye bien conocida. Los glucósidos descomponer nel tracto dixestivu humanu, lo que produz la lliberación de cianuru d'hidróxenu. Si fierve la yuca fresca, la tosicidá mengua bien pocu. El glucósido linamarina ye resistente al calor, y l'enzima linamarasa s'inactiva a 75 °C.

En dellos países d'África, la llamada enfermedá del konzo producióse pol consumu casi esclusivu mientres delles selmanes de yuca mal procesada.[11]

Los métodos d'ellaboración de la yuca pa desintoxicar los tubérculos básense fundamentalmente na hidrólisis enzimática p'amenorgar la concentración de glucósidos.

Pueden estremase los siguientes procesos:

Prepárase la fécula del tubérculu fresco y molío por aciu sedimentación, llaváu y ensugáu. Esti productu ye conocíu como farinha d'enagua en Brasil.

Referencia

Gastronomía

Esta páxina forma parte del wikiproyeutu Botánica, un esfuerciu collaborativu col fin d'ameyorar y organizar tolos conteníos rellacionaos con esti tema. Visita la páxina d'alderique del proyeutu pa collaborar y facer entrugues o suxerencies.

Esta páxina forma parte del wikiproyeutu Botánica, un esfuerciu collaborativu col fin d'ameyorar y organizar tolos conteníos rellacionaos con esti tema. Visita la páxina d'alderique del proyeutu pa collaborar y facer entrugues o suxerencies. Manihot esculenta, llamada comúnmente yuca, ya internacionalmente reconocida como mandioca, tapioca, guacamota (del náhuatl cuauhcamohtli en Méxicu), casabe o casava, ye un parrotal perenne de la familia de les euforbiacees estensamente cultiváu en Suramérica, África y el Pacíficu polos sos tubérculos con almidones d'altu valor alimentario.

La yuca o mandioca ye endémica de les rexones con clima tropical de Bolivia, Brasil, Colombia, Ecuador, Méxicu, Panamá, Perú, República Dominicana, Puertu Ricu, Venezuela, Costa Rica, y Paraguái y foi cultiváu con gran ésitu en naciones africanes de similares condiciones climatolóxiques, y anque s'envalora que les variedaes güei conocíes son efeutu de la seleición artificial, hai variedaes xeneraes pol aislamientu xeográficu de la selva (casabe, que ye altamente venenosa) al de los altiplanos (yuca, mínimamente venenosa).

Maniok (lat. Manihot esculenta)- Südləyənkimilər fəsiləsindən bir bitkidir. Tropik və Subtropik Amerikada yetişən bu bitkinin yüz əllidən çox növü var. Kökündə bol miqdarda nişasta olduğu üçün yerlilərin qidalanmasında böyük əhəmiyyət daşıyır, həmçinin nişastasından tapioka keçirildiyi üçün kommersiya cəhətdən də əhəmiyyəti böyükdür. Maniok kökləri, heyvan yemi kimi də istifadə edilir. Xüsusilə halqa və ya un halında satılan maniok, kiçik malları və donuz balalarını bəsləməkdə istifadə edilən, həzmi çox asan bir qidadır. Maniok Braziliyada bitən bir növündən kauçuk əldə edilir.Bitkinin əsas istehsalçıları Nigeriya, Tailand, İndoneziya, Braziliya və Konqo Respublikasıdır.

La mandioca (Manihot esculenta), a vegades anomenada també iuca (no s'ha de confondre amb el gènere iuca o Yucca sp), és una planta de la família Euphorbiaceae. D'aquesta planta s'obté la tapioca, aliment ric en glúcids com el midó.[1]

És un arbust perennifoli, monoic, amb arrels tuberoses engruixides, fusiformes i d'arrels fibroses. Les fulles són alternes, palmades i estipulades.

Es conrea com a aliment bàsic a molts països tropicals. La mandioca és la tercera font d'hidrats de carboni de la humanitat.[2][3] La mandioca es classifica com "dolça" o "amargant" depenent del nivell de la substància tòxica (glucòsids cianogènics) que conté. Una preparació poc acurada de la mandioca causa una malaltia anomenada konzo. Tanmateix els agricultors prefereixen conrear varietats "amargants", ja que són més resistents a les plagues.[4]

L'arrel de mandioca fa de 5 a 10 cm de diàmetre i arriba a fer de 50 a 80 cm de llarg. L'interior de l'arrel pot ser blanca o grogosa. És rica en midó, calci, fòsfor i vitamina C (25 mg/100 g) però pobra en proteïnes i altres nutrients.

La mandioca (Manihot esculenta), a vegades anomenada també iuca (no s'ha de confondre amb el gènere iuca o Yucca sp), és una planta de la família Euphorbiaceae. D'aquesta planta s'obté la tapioca, aliment ric en glúcids com el midó.

Maniok jedlý (Manihot esculenta), známý též pod jmény cassava či yuca, anebo tapioka v Asii, je kulturní tropická rostlina patřící do čeledi pryšcovité (Euphorbiaceae).

Pochází z tropické Ameriky a je zahrnován mezi klíčové okopaniny.[1] Pěstoval se již 4000 let př.n.l.[2] Vyznačuje se velmi atraktivním látkovým složením, jak pro výživu člověka, tak i hospodářských zvířat, a to hlavně nejen díky přítomnosti škrobu, ale i množství bílkovin.[1] Někdy se manioku podobně jako jamům a batátům přezdívá sladké brambory.

Maniok je bylina nebo keř dorůstající výšky 1 až 5 metrů.[3]

Kořenový systém tvoří pět až deset vějířovitě rozložených kořenových hlíz, které vznikly ztloustnutím adventivních kořenů. Tyto hlízy (20–100 cm dlouhé) dorůstají válcovitého nebo vřetenovitého tvaru. Mohou vážit až 2 kg. Jejich povrch je růžový až tmavě hnědý.[1]

Stonek o obvodu 2–7 cm je tvořen ztloustlými články.[1]

Listy manioku jsou dlouze řapíkaté a jejich čepele jsou hluboce dlanitě laločnaté. Počet laloků se pohybuje od tří do devíti. Zbarvení listů je velmi variabilní od žlutozelené až po červenou barvu.[3]

Barevnou variabilitou disponují kromě listů i květy, které bývají světle žluté nebo červené, bezkorunné, se zvonkovitým kalichem. Květenství, která vyrůstají v paždí listů, dosahují u samčích a samičích květů délky 10 cm.[3]

Plodem je asi 1,5 cm dlouhá tobolka s úzkými podélnými křídly. Ve zralosti tobolka praská a vymršťuje tak semena.[3]

Obsahuje glykosid linamarin, který je při narušení buněk pletiva hydrolyzován enzymem linamarázou na kyanovodík. K tomuto jevu dochází nejen při vaření a krájení, ale i sušení, pečení nebo kvašení hlíz.[1]

Podle obsahu linamarinu se rozlišují odrůdy hořké a sladké. Obě jsou jedlé a představují základní potravinovou složku pro více než 500 milionů lidí. Představují tak velmi cennou potravinu, zejména v Africe.[1]

Je to hlavně škrob, který se z hlíz získává a který se používá nejen v potravinářském a kosmetickém průmyslu, ale i při výrobě lepidel.[1]

Rovněž se využívá jako krmivo - zkrmuje se v podobě maniokové moučky hlavně prasatům, skotu, ovcím a kozám. Dále se z něj vyrábí škrobová šlichta používaná při šlichtování. Z kasavy se též připravuje i pivo a jiné alkoholické nápoje.[1]

Maniok jedlý se pěstuje zejména v tropických oblastech. V současné době v tropech takřka všech světadílů.[1] Minimum srážek v kombinaci s písčitými nebo písčitohlinitými půdami představuje pro maniok ideální růstové podmínky.[3]

Nevýhodou těchto klimatických podmínek je problematické skladování.[1] Hlízy manioku jedlého se totiž vyznačují vysokým obsahem vody, která v kombinaci s vysokou teplotou vzduchu urychluje proces kvašení a následného hnití.[1]

Maniok jedlý (Manihot esculenta), známý též pod jmény cassava či yuca, anebo tapioka v Asii, je kulturní tropická rostlina patřící do čeledi pryšcovité (Euphorbiaceae).

Pochází z tropické Ameriky a je zahrnován mezi klíčové okopaniny. Pěstoval se již 4000 let př.n.l. Vyznačuje se velmi atraktivním látkovým složením, jak pro výživu člověka, tak i hospodářských zvířat, a to hlavně nejen díky přítomnosti škrobu, ale i množství bílkovin. Někdy se manioku podobně jako jamům a batátům přezdívá sladké brambory.

Kassava (Manihot esculenta) også kaldet yuca, yucca eller maniok (af spansk cazabe, af taino (Caribien) casaví 'mel fra maniok'), stivelse udvundet af maniokplanten. Planten stammer fra oprindeligt fra Brasilien og Sydamerika, hvor den første gang blev avlet for ca. 10.000 år siden.

Det meste af rodknoldenes mælkesaft fjernes, de skæres i skiver og tørres, hvorefter de males til mel, der dels bruges til gryn med handelsnavnet tapioka, dels til stivelse, der bl.a. går under navnene kassava og arrowroot og er et surrogat for den ægte arrowroot. Kassava anvendes som stivelsesmiddel i madlavning i lighed med sago og kartoffel. [1]

Verdensproduktionen af kassava var ifølge statistik fra FN på 184 millioner tons i 2002. Majoriteten i Afrika med 99,1 millioner tons. 51,5 millioner tons blev dyrket i Asien og 33,2 millioner tons i Latinamerika og Caribien. Nigeria er verdens største producent af kassava.

Kassava (Manihot esculenta) også kaldet yuca, yucca eller maniok (af spansk cazabe, af taino (Caribien) casaví 'mel fra maniok'), stivelse udvundet af maniokplanten. Planten stammer fra oprindeligt fra Brasilien og Sydamerika, hvor den første gang blev avlet for ca. 10.000 år siden.

Det meste af rodknoldenes mælkesaft fjernes, de skæres i skiver og tørres, hvorefter de males til mel, der dels bruges til gryn med handelsnavnet tapioka, dels til stivelse, der bl.a. går under navnene kassava og arrowroot og er et surrogat for den ægte arrowroot. Kassava anvendes som stivelsesmiddel i madlavning i lighed med sago og kartoffel.

Verdensproduktionen af kassava var ifølge statistik fra FN på 184 millioner tons i 2002. Majoriteten i Afrika med 99,1 millioner tons. 51,5 millioner tons blev dyrket i Asien og 33,2 millioner tons i Latinamerika og Caribien. Nigeria er verdens største producent af kassava.

Der Maniok (Manihot esculenta) ist eine Pflanzenart aus der Gattung Manihot in der Familie der Wolfsmilchgewächse (Euphorbiaceae). Andere Namen für diese Nutzpflanze und ihr landwirtschaftliches Produkt (die geernteten Wurzelknollen) sind Mandi'o (Paraguay), Mandioca (Brasilien, Argentinien, Paraguay), Cassava, Kassave oder im spanischsprachigen Lateinamerika Yuca. Der Anbau der Pflanze ist wegen ihrer stärkehaltigen Wurzelknollen weit verbreitet. Die verarbeitete Stärke wird Tapioka genannt. Sie stammt ursprünglich aus Südamerika und wurde schon von den Ureinwohnern zur Ernährung verwendet. Mittlerweile wird sie weltweit in vielen Teilen der Tropen und Subtropen angebaut. Auch andere Arten aus der Gattung Manihot werden als Stärkelieferant verwendet.

Maniok ist unter verschiedenen Bezeichnungen bekannt. Die Bezeichnung Maniok stammt vom Wort Maniot der ursprünglich an der brasilianischen Atlantikküste verbreiteten Tupi-Guarani-Sprache ab. Heute wird das Guarani-Wort mandi'o[1] in Paraguay verwendet. In Brasilien wird Maniok heute als Mandioca bezeichnet, was vom Namen der Frau Mandi-Oca (oder mãdi'og)[2] abgeleitet ist – ihrem Körper soll, nach einer Legende der brasilianischen Ureinwohner, die Maniokpflanze entsprungen sein. Der Name Cassava stammt vom Arawak-Wort Kasabi ab und das Wort Yuca entstammt der Sprache der Kariben.[3]

Maniokpflanzen sind Sträucher mit einer Wuchshöhe von 1,5 m bis 5 m. Alle Pflanzenteile führen Milchsaft. Sämlinge bilden zunächst eine Pfahlwurzel. Die faserigen Seitenwurzeln verdicken sich und bilden große, spindelförmige Wurzelknollen. Die Stängel zeigen je nach Sorte unterschiedliche Wachstumsmuster: mit starker Verzweigung von der Basis oder mit einem durchgehenden, wenig verzweigten Leittrieb. Die Blätter sind handförmig in drei bis neun Segmente geteilt; jedes misst 8 cm bis 18 cm in der Länge und 1,5 cm bis 4 cm in der Breite. Die Blätter stehen an 6 cm bis 35 cm langen Blattstielen. Am Grund des Blattstieles befinden sich zwei dreieckige bis lanzettliche Nebenblätter. Diese werden 5 mm bis 7 mm lang, sie sind ganzrandig oder sind in wenige stachelspitzige Segmente geteilt. Die Blätter werden bei Trockenperioden abgeworfen.

Die rispigen, 5 cm bis 8 cm großen Blütenstände können endständig sein oder in den Blattachseln stehen. Es gibt männliche und weibliche Blüten, die beide auf einer Pflanze vorkommen (Monözie). Die kurz und dünn gestielten kleineren männlichen Blüten bestehen aus fünf gelblichen bis weißlichen und rötlichen bis purpurnen Tepalen, die bis zur Hälfte ihrer Länge oder weniger miteinander verwachsen sind. Auf der Innenseite sind sie behaart. Die länger, kurvig und dicker gestielten weiblichen Blüten besitzen ebenfalls fünf miteinander wenig verwachsene Tepale, diese sind mit 1 cm Länge größer als die der männlichen Blüten. Der dreikammerige, rippige Fruchtknoten ist oberständig, die Griffel sind sehr kurz mit fleischigen und rüschigen Narben. In den männlichen Blüten kann ein Pistillode vorhanden sein. Es sind zehn Staubblätter in zwei Kreisen mit länglichen Antheren ausgebildet, die äußeren sind länger. Bei den weiblichen Blüten können Staminodien vorhanden sein. Die Blüten besitzen jeweils einen mehrlappigen und fleischigen, gelblich bis rötlichen Diskus.

Die eiförmig bis rundliche, septizid-lokulizide Kapselfrucht ist oval, 1,5 cm bis 1,8 cm lang bei 1,0 cm bis 1,5 cm Breite. Sie weist sechs längs verlaufende Rippen auf und enthält drei glatte, leicht dreieckige, etwa 1 cm große, dunkelbraune, grau gesprenkelte Samen. An frischen Samen haftet noch die Caruncula an.[4][5][6]

Die Chromosomenzahl beträgt 2n = 36, seltener 30 oder 54.[7]

Die weiblichen Blüten reifen vor den männlichen (Protogynie), so dass eine Selbstbestäubung vermieden wird. Bei künstlich herbeigeführter Selbstbestäubung kommt es zu Inzuchtdepression. Die Blüten enthalten Nektar, der Insekten als Bestäuber anlockt. Die Früchte platzen bei der Reife auf und schleudern die Samen heraus.

Maniokpflanzen bevorzugen sandige oder sandig-lehmige Böden. Das Wachstum ist auf leicht saurem Substrat am besten, es wird jedoch ein weiter Bereich von pH-Wert 4 bis 8 toleriert. Maniok kommt gut mit typischen tropischen Böden zurecht, die einen hohen Gehalt an Aluminium und Mangan und wenig verfügbare Nährstoffe aufweisen. Trockenzeiten überstehen sie gut, indem sie das Laub abwerfen, nach dem Einsetzen von Regenfällen treiben sie schnell wieder aus. Maniok verlangt einen sonnigen Standort, Temperaturen unter 10 °C werden nicht vertragen.[5]

Maniok ist nur aus Kultur bekannt, er ist wahrscheinlich als allotetraploide Pflanze aus südamerikanischen Manihot-Arten entstanden.[5] Die Herkunft der Maniokpflanze ist nicht genau geklärt, sowohl Süd- als auch Mittelamerika kommen als Herkunftsort in Frage. Die ältesten archäologischen Funde von Manioküberresten wurden in Mexiko gemacht, ihr Alter wird auf 2800 Jahre geschätzt. Als weitere Ursprungsorte kommen Goiás, das Hinterland Bahias oder die Amazonasregion in Frage. Es ist auch denkbar, dass der Maniok in Mittel- und Südamerika unabhängig voneinander domestiziert wurde.[8] In der Moxos-Ebene wurde bereits vor über 10.000 Jahren Maniok angebaut.[9][10]

Fest steht, dass der Maniok von Südamerika aus in die Karibik kam. Die Kariben und Arawak kannten Maniok bereits, als sie die karibischen Inseln von Süden her besiedelten, und sie hatten bereits bei ihrer Migration auch das Wissen über Vermehrung, Anbau und Verarbeitung der Pflanzen.[8]

Die älteste europäische Beschreibung von Maniok stammt aus dem Jahre 1494. Die Spanier stießen in der Karibik und die Portugiesen im heutigen Brasilien auf die Pflanze, man berichtete von Brot aus giftigen Wurzeln.[11] In den mittel- und südamerikanischen Kolonialgesellschaften erlangte Maniok schnell große Bedeutung für die Ernährung der Siedler und der Sklaven. Während das fruchtbare Land zum Zuckerrohranbau genutzt wurde, bepflanzte man weniger fruchtbare Äcker mit Maniok. Verarmte Bauern und entlaufene Sklaven bauten Maniok an und verkauften ihn in die Städte und an die Zuckerpflanzer. Das auch bei tropischen Temperaturen haltbare Maniokmehl diente Soldaten und Eroberern (Bandeirantes) als Proviant.[11]

Die Portugiesen brachten Maniok nach Afrika, sowohl in der Form von Mehl oder Brot als Nahrung für die Sklaven während ihres Transportes von Afrika nach Amerika, als auch in Form von Pflanzen, die in Afrika vermehrt werden sollten. Zusammen mit den Pflanzen musste auch das Wissen über ihren Anbau und vor allem die richtige Verarbeitung weitergegeben werden. Es gelang den Portugiesen nur im heutigen Angola, Maniok einzuführen, was auf die guten Beziehungen zu den im 15. Jahrhundert herrschenden Bakongo-Königen zurückzuführen sein dürfte.[11] Vor allem im Regenwald des heutigen Kongo verbreitete sich der Maniokanbau rasch.[12]

In Westafrika, wo die Portugiesen vergeblich versucht hatten, den Maniok einzuführen, wurde die Pflanze erst im 19. Jahrhundert von der Bevölkerung akzeptiert. Die Maniokkultivierung wurde von befreiten Sklaven, die aus Amerika zurückgekehrt waren, vermittelt, die Kolonialherren förderten den Maniokanbau als Maßnahme zur Vermeidung von Hungersnöten.[12] In Ostafrika wurde Maniok im 18. Jahrhundert von den Portugiesen und Franzosen eingeführt, wobei auch letztere Schwierigkeiten hatten, die richtige Verarbeitung der Wurzeln zu vermitteln: auf Madagaskar waren die ersten Versuche des Maniokanbaus mit Massenvergiftungen verbunden.[12]

In Asien begann man bereits im 17. Jahrhundert, den Maniok einzuführen. Dies gelang zunächst auf den Molukken, später auf Java und im 18. Jahrhundert in Goa und auf den Inseln im indischen Ozean. In Indonesien und in Indien wurde mit dem Ziel des Vermeidens von Hungersnöten der Maniokanbau von den Kolonialmächten gefördert.[13] Maniok gelangte auch nach China, er wird dort jedoch nur in beschränktem Umfang als Viehfutter angebaut.[14]

Wie der Maniok auf die pazifischen Inseln gelangte, ist nicht genau geklärt. Eine spanische Expedition berichtete bereits 1770 von Maniokanbau auf der Osterinsel, was Theorien der Besiedlung Ozeaniens von Südamerika aus unterstützen würde. Besser dokumentiert ist, dass die Pflanze im 19. Jahrhundert von Engländern nach Tahiti gebracht wurde und sich von dort aus auf alle anderen pazifischen Inseln verbreitete.[14] Heute wird Maniok verbreitet in den Tropen angebaut, vor allem in Regionen mit einer trockenen Jahreszeit.[5]

2020 wurden laut der Ernährungs- und Landwirtschaftsorganisation FAO weltweit 302.662.494 t Maniok (Cassava) geerntet.[15]

Folgende Tabelle gibt eine Übersicht über die zehn größten Produzenten von Maniok weltweit, die insgesamt 73,6 % der Erntemenge produzierten.

Als Nahrungsmittel werden hauptsächlich die Wurzelknollen verwendet, gelegentlich auch die Blätter als Gemüse. Die 0,15 m bis 1 m langen und 3 cm bis 15 cm dicken Knollen können ein Gewicht von bis zu 10 kg erreichen. Sie werden von einer verkorkten, meist rötlich braunen äußeren Schicht umgeben, innen sind sie meist weiß, gelegentlich auch gelb oder rötlich.[5]

Im rohen Zustand sind die Wurzelknollen giftig, da sie Glucoside, hauptsächlich Linamarin, enthalten. Dieses cyanogene Glykosid wird in der Vakuole der Pflanzenzelle gespeichert und hat keine toxische Wirkung. Wird die Pflanze jedoch verletzt (z. B. durch Fraßfeinde), gelangt die Substanz in Kontakt mit dem Enzym Linamarase, und D-Glucose wird abgespalten. Das nun entstandene Acetoncyanhydrin kann, spontan oder katalysiert durch das Enzym Hydroxynitril-Lyase, zu Aceton und Blausäure zerfallen.[16] Der Gehalt an giftigen Stoffen ist stark sortenabhängig, sogenannte „süße“ Sorten enthalten nur wenig Glucosid.

Vergiftungserscheinungen sind zum Beispiel eine Ataxie oder Optikusatrophie.[17] Blausäure verflüchtigt sich zwar bei Zimmertemperatur, um jedoch ein vollständiges Ausgasen zu bewirken, muss die Knolle gründlich zerkleinert werden. Methoden, die Pflanzen zu entgiften, bestehen darin, die Pflanze zu Mehl zu mahlen und dann mit kochendem Wasser auszuwaschen, im Fermentieren und im Erhitzen.[5] Eine andere Methode wurde von Howard Bradbury und Kollegen entwickelt. Die Pflanze wird zu Mehl gemahlen und mit Wasser vermischt. Anschließend wird das Gemisch im Schatten dünn (ca. 1 cm) ausgebreitet. Dort lässt man es für fünf bis sechs Stunden ruhen. So kann fast die gesamte Blausäure ausgasen.[18]

Da Maniok einen geringen Gehalt an Protein (ca. 2–3 % der Trockenmasse) und sehr wenige essenzielle Aminosäuren (Gefahr des Kwashiorkor-Syndroms) hat, empfiehlt sich bei stark maniokbasierter Ernährung zum Beispiel der zusätzliche Verzehr der proteinreichen (ca. 30 % der Trockenmasse) Maniokblätter, um Mangelerscheinungen entgegenzuwirken.[5] Da dies in vielen afrikanischen Ländern nicht üblich ist, wird derzeit auch an einer Manioksorte gearbeitet, die Provitamin A und andere Mikronährstoffe in der Wurzel produziert.[19]

Da Maniok nur geringe Mengen an Eisen und Zink enthält, führt dies zu Mangelerscheinungen bei Menschen, die sich hauptsächlich von Maniok ernähren und damit nur etwa 10 % des täglichen Bedarfs an diesen Mineralien decken. Forscher haben durch den gentechnischen Einbau der Gene für das Eisen-Transporter-Proteins VIT1 und des Ferritin-Proteins FER1 von Arabidopsis thaliana eine Sorte erschaffen, die deutlich erhöhte Menge an Eisen und Zink aus dem Boden binden kann. In Feldtests nahmen diese Pflanzen die 7- bis 18-fache Menge Eisen und die bis zu 10-fache Menge Zink auf[20][21]

100 g Maniokknollen haben einen Brennwert von 620 kJ (148 kcal), die Blätter entsprechend 381 kJ (91 kcal).[5]

Die Bearbeitung beruht im Wesentlichen auf Verfahrensweisen, die von den Indianern im Amazonasgebiet insbesondere auch zur Entgiftung praktiziert wurden und von Chronisten bereits im 16. Jahrhundert erwähnt wurden, wie beispielsweise 1587 von Gabriel Soares de Sousa in seiner Schrift Tratado descriptivio do Brasil.[22] Traditionell werden die Knollen geschält, zerrieben oder geraspelt und dann eingeweicht. Nach einigen Tagen presst man die Masse aus, wäscht sie durch den sogenannten Tipiti und röstet sie in Öfen. Die in der Presse zurückbleibende Masse liefert das Maniok- oder Mandiokamehl. Ein Nebenprodukt der Herstellung von Maniokmehl ist Stärke, die in Brasilien Polvilho, auch Tapioka genannt wird. Es besteht bei manchen (glykosidarmen) Sorten auch die Möglichkeit, die geschälten und zerkleinerten Knollen in Salzwasser essbereit zu kochen.

Maniokmehl kann ähnlich wie Weizenmehl verwendet werden. Menschen mit Allergien gegen Weizen und andere Getreide verwenden deshalb häufig Maniokmehl als Ersatz.

Das Mehl wird je nach Region unterschiedlich weiterverarbeitet. Man bereitet unter anderem daraus eine Art Kuchen (zum Beispiel der brasilianische Beiju), der Brot mehr oder weniger ähnlich ist, oder vermischt das Mandiokamehl mit Weizenmehl, wie zum Beispiel beim Conaque auf den Antillen. In Brasilien werden auch die Beilage Farofa und das Getränk Tarubá aus Maniokmehl hergestellt. Während man in Deutschland unter der Bezeichnung Mehl das Weizenmehl versteht, so ist in Brasilien der Ausdruck farinha ein Synonym für Maniokmehl, während Weizenmehl als farinha de trigo bezeichnet wird.

In den meisten lateinamerikanischen Ländern wird Maniok auch ähnlich wie Salzkartoffeln zubereitet und als Beilage serviert. Die Maniokwurzel kann nach dem Kochen frittiert werden und ähnelt dann Pommes frites. Auch im Sudan werden Würfel der Knolle frittiert. Ein vor allem in Peru äußerst beliebtes Gericht ist Yuca á la Huancaína; frittierte Yuquitas gibt es dort bei allen großen Fastfood-Ketten als Snack.

Mit Wasser vermischt wird Maniokmehl zu Manioksaft, das von Indigenen in Südamerika Chimbé genannt, getrunken wird.[23]

In Afrika (vor allem Kamerun, Gabun und Kongo) wird das Mehl für eine Art Kloßteig (Fufu) verwendet. Die Knolle wird im Dampf oder in Wasser gekocht oder frittiert. Sehr beliebt und für europäische Gaumen gewöhnungsbedürftig sind in Palmblätter eingewickelte Maniokstangen, die Bobolo oder im Kongo Kwánga genannt werden.

Die frische Wurzel wird auch als Heilmittel bei Geschwüren benutzt. Die Samen einiger Sorten wirken abführend und brechreizerregend.

Maniok bzw. Tapioka kann als Futtermittelzusatz für die Fleischproduktion verwendet werden, da es ein billiger Rohstoff ist. Etwa 25 % der weltweiten Maniokproduktion werden heute für Futtermittel verwendet. In Afrika und Asien beträgt dieser Anteil 17 % bzw. 24 %, in Lateinamerika 47 %.[24] Der Anteil von Maniok in der Mischfutterzusammensetzung der EU-27 betrug 2007 lediglich 0,5 %. Anfang der 1990er Jahre betrug der Anteil noch 6 %. Von den gesamten Futtermittelimporten machte Maniok 2007 gerade noch 0,2 % aus.[25]

Ein großes Potenzial wird Maniok für die Bioethanolproduktion beigemessen. Derzeit findet die Ethanolproduktion aus Maniok allerdings nur in China und Thailand statt. Die Produktionskosten von Ethanol liegen bei etwa 0,27 €/l und der Ethanolertrag bei 3,5 bis 4 m³/ha. Als erzielbaren Kraftstoffertrag aus Maniok in Asien werden etwa 78 GJ/ha angegeben.[26]

Maniok spielt auch als Stärkelieferant für die Fermentationsindustrie eine Rolle. Die Maniokstärke kann zur Herstellung von bio-basierten Kunststoffen wie Polylactid auf der Basis von Milchsäure verwendet werden, wie dies zum Beispiel in Thailand geplant ist. Dadurch könnte sich das Marktvolumen der thailändischen Maniokindustrie nach Schätzungen der National Innovation Agency (NIA) auf nahezu drei Mrd. € mehr als verdoppeln.[27]

Auch die Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) sieht ein großes Potenzial für die Nutzung von Maniok als nachwachsendem Rohstoff vor dem Hintergrund, dass derzeitige Erträge nur bei 20 % des unter optimalen Bedingungen erreichbaren Niveaus liegen. Allerdings dürfte die Tatsache, dass Maniok etwa eine Milliarde Menschen mit bis zu einem Drittel ihrer täglichen Kalorienaufnahme versorgt und damit ein wichtiges Grundnahrungsmittel ist, der weiteren Nutzung als nachwachsender Rohstoff vor dem Hintergrund der Diskussion um den Konflikt zwischen Nahrungsproduktion und industrieller Nutzung entgegenstehen.[28]

Der Einsatz von Maniok als Rohstoff für die Bierherstellung wird von afrikanischen Regierungen gefördert, um den Import von Braumalz zu reduzieren.[29]

Der Maniok (Manihot esculenta) ist eine Pflanzenart aus der Gattung Manihot in der Familie der Wolfsmilchgewächse (Euphorbiaceae). Andere Namen für diese Nutzpflanze und ihr landwirtschaftliches Produkt (die geernteten Wurzelknollen) sind Mandi'o (Paraguay), Mandioca (Brasilien, Argentinien, Paraguay), Cassava, Kassave oder im spanischsprachigen Lateinamerika Yuca. Der Anbau der Pflanze ist wegen ihrer stärkehaltigen Wurzelknollen weit verbreitet. Die verarbeitete Stärke wird Tapioka genannt. Sie stammt ursprünglich aus Südamerika und wurde schon von den Ureinwohnern zur Ernährung verwendet. Mittlerweile wird sie weltweit in vielen Teilen der Tropen und Subtropen angebaut. Auch andere Arten aus der Gattung Manihot werden als Stärkelieferant verwendet.

Maniok ist unter verschiedenen Bezeichnungen bekannt. Die Bezeichnung Maniok stammt vom Wort Maniot der ursprünglich an der brasilianischen Atlantikküste verbreiteten Tupi-Guarani-Sprache ab. Heute wird das Guarani-Wort mandi'o in Paraguay verwendet. In Brasilien wird Maniok heute als Mandioca bezeichnet, was vom Namen der Frau Mandi-Oca (oder mãdi'og) abgeleitet ist – ihrem Körper soll, nach einer Legende der brasilianischen Ureinwohner, die Maniokpflanze entsprungen sein. Der Name Cassava stammt vom Arawak-Wort Kasabi ab und das Wort Yuca entstammt der Sprache der Kariben.

Cassava (Manihot esculenta), forby cried manioc, yuca, balinghoy, mogo, mandioca, kamoteng kahoy, tapioca-ruit (predominantly in Indie) an manioc ruit, a widdy shrub o the Euphorbiaceae (spurge) faimily native tae Sooth Americae, is extensively cultivatit as an annual crap in tropical an subtropical regions for its edible starchy tuberous ruit, a major soorce o carbohydrates. It differs frae the seimilar spellt yucca, an unrelatit fruit-bearin shrub in the Asparagaceae faimily. Cassava, whan dried tae a poudery (or pearly) extract, is cried tapioca; its fermented, flaky version is named garri.

Chhiū-chî (ha̍k-miâ: Manihot esculenta) sī 1 khoán tn̂g-nî-seⁿ (perennial) ê kē-bo̍k, in-ūi kin ê pō·-ūi hâm chin chē tiān-hún, chèng-choh ê hoān-ûi chiâⁿ khoah, chú-iàu tī jia̍t-tài, ē-jia̍t-tài ê tē-khu. Só·-ū ê chéng lóng sī cultigen.

Chhiū-chî ū chē-chē lō·-iōng, pau-koat bôa chò hún, sī hún-îⁿ ê ki-pún châi-liāu.

Chhiū-chî (ha̍k-miâ: Manihot esculenta) sī 1 khoán tn̂g-nî-seⁿ (perennial) ê kē-bo̍k, in-ūi kin ê pō·-ūi hâm chin chē tiān-hún, chèng-choh ê hoān-ûi chiâⁿ khoah, chú-iàu tī jia̍t-tài, ē-jia̍t-tài ê tē-khu. Só·-ū ê chéng lóng sī cultigen.

Chhiū-chî ū chē-chē lō·-iōng, pau-koat bôa chò hún, sī hún-îⁿ ê ki-pún châi-liāu.

Cuauhcamohtli (Manihot esculenta).

Jôdny maniok (Manihot esculenta) – to je ôrt roscënë z rodzëznë psotnikòwatëch (Euphorbiaceae). Òn je z Brazylsczi i nie rosce na Kaszëbach. Jôdny maniok je do jedzeniô.

Ang kamoteng-kahoy o kasaba (Ingles: cassava, tuber, ( /kəˈsɑːvə/),[2]) ay isang uri ng halamang-ugat na nagsisilbing pangunahing pagkain sa Pilipinas, katulad ng sa Mindanao.[3] Maharina ang ugat na ito na nagagamit sa paggawa ng mga tinapay at mamon.[4]

![]() Ang lathalaing ito na tungkol sa Gulay ay isang usbong. Makatutulong ka sa Wikipedia sa nito.

Ang lathalaing ito na tungkol sa Gulay ay isang usbong. Makatutulong ka sa Wikipedia sa nito.

Ang kamoteng-kahoy o kasaba (Ingles: cassava, tuber, ( /kəˈsɑːvə/),) ay isang uri ng halamang-ugat na nagsisilbing pangunahing pagkain sa Pilipinas, katulad ng sa Mindanao. Maharina ang ugat na ito na nagagamit sa paggawa ng mga tinapay at mamon.

Mga ugat

dahon

Manihot esculenta

Ketéla pohung utawa singkong utawa kaspé, utawa sajeroning Basa Indonésia ubi kayu utawa ubi pohon, iku tetuwuhan taunan tropika lan subtropika saka kulawarga Euphorbiaceae. Uwiné dikenal minangka panganan pokok sing ngasilaké karbohidrat lan godhongé minangka janganan.

Téla pohong ing tlatah Surabaya karan menyok, ing tlatah Banyumasan diarani bodin, yèn ing tlatah Kulon Praga sisih lor lan sapérangan Magelang sinebut jendal ya iku jinis tetuwuhan kang biyasa ditandur ana ing tegalan ing mangsa rendheng. Tela kang ditandur ing taun tropika lan subtropika asalé saka kulawarga Euphorbiaceae. Umbiné mumpangaté akèh, salah sijiné bisa kanggo bahan panganan pokok lan ngasilaké karbohidrat lan godhong bisa kanggo sayuran. Godhong téla iku jenengé jlegur. Umbi téla kang ana ing lemah (siti) mertandhakaké, tetuwuhan iki kagolong ing suku palakepedhem, duwé oyot kang dadi pohung utawa umbi. Kanthi duwé titikan wujudé rata-rata gilig lan lonjong. Ing pohong duwé garis tengah kurang luweh 2–3 cm lan dawané kira-kira 50–80 cm. Dawa lan gedhené téla bisa diprabawai saka jinisé kang ditandur ana ing tegalan. Werniné tela ana loro putih lan kuning.

Jinis ketéla pohung Manihot esculenta sepisanan dikenal ing Amérika Kidul banjur tumangkar ing mangsa pra-sajarah ing Brasil lan Paraguay. Jinis-jinis modhèren saka spésies sing wis dibudidaya bisa tinemu tuwuh ing Brasil kidul. Sanadyan spésies Manihot sing alasan akèh, kabèh varitas M. esculenta bisa dibudidaya.

Prodhuksi ketéla pohung donya dikira-kira ngancik 184 yuta ton ing taun 2002. Sapérangan gedhé prodhuksi diasilaké ing Afrika 99,1 yuta ton lan 33,2 yuta ton ing Amérika Latin lan Kapuloan Karibia. Téla ditandur ing Indonésia kanggo panganan pokok (mangsa iku Hindhia Walanda) lan didol ing taun 1810[1], lan sadurungé kawanuhaké karo wong Portugis ing abad kaping 16 ning Nuswantara saka Brasil.

Ing sawatara nagara, ketéla pohung wis akèh digawé bahan bakar ethanol, lan ketéla pohung dadi bahan bakar wigati [3].

Ketéla pohung biyasa kanggo panganan kéwan. Damèn godhong ketéla pohung sing wis digaringaké sadina utawa rong dina dianggo panganan kéwan kaya déné sapi, wedhus utawa wedhus gibas.

Ketéla pohung utawa singkong utawa kaspé, utawa sajeroning Basa Indonésia ubi kayu utawa ubi pohon, iku tetuwuhan taunan tropika lan subtropika saka kulawarga Euphorbiaceae. Uwiné dikenal minangka panganan pokok sing ngasilaké karbohidrat lan godhongé minangka janganan.

Téla pohong ing tlatah Surabaya karan menyok, ing tlatah Banyumasan diarani bodin, yèn ing tlatah Kulon Praga sisih lor lan sapérangan Magelang sinebut jendal ya iku jinis tetuwuhan kang biyasa ditandur ana ing tegalan ing mangsa rendheng. Tela kang ditandur ing taun tropika lan subtropika asalé saka kulawarga Euphorbiaceae. Umbiné mumpangaté akèh, salah sijiné bisa kanggo bahan panganan pokok lan ngasilaké karbohidrat lan godhong bisa kanggo sayuran. Godhong téla iku jenengé jlegur. Umbi téla kang ana ing lemah (siti) mertandhakaké, tetuwuhan iki kagolong ing suku palakepedhem, duwé oyot kang dadi pohung utawa umbi. Kanthi duwé titikan wujudé rata-rata gilig lan lonjong. Ing pohong duwé garis tengah kurang luweh 2–3 cm lan dawané kira-kira 50–80 cm. Dawa lan gedhené téla bisa diprabawai saka jinisé kang ditandur ana ing tegalan. Werniné tela ana loro putih lan kuning.

Mandi'o (poytugañe'ẽ, karaiñe'ẽ: mandioca, casava, lasioñe'ẽ: Manihot esculenta), ka'avo oñeñotýva tetã ijyvy akúvape, hapo yvyguýpe, ombotyra tembi'úpe, so'o mbichýpe. Mandi'o rapógui oñeguenohẽ aramirõ ojeporu haguã heta mba'épe.

Maniok (Manihot esculenta) as en plaantenslach uun det skööl Manihot, an hiart tu det famile Euphorbiaceae.

Ööder nöömer san Mandi'o (Paraguay), Mandioca (Brasiilien, Argentiinien, Paraguay), Cassava, Kassave of uun Madelameerikoo Yuca.

Mä detdiar plaant woort büüret, auer a ruter eden wurd kön. Hat wääkst uun a troopen an subtroopen. Uk mä ööder slacher uun det skööl Manihot woort büüret.

Maniok (Manihot esculenta) as en plaantenslach uun det skööl Manihot, an hiart tu det famile Euphorbiaceae.

Ööder nöömer san Mandi'o (Paraguay), Mandioca (Brasiilien, Argentiinien, Paraguay), Cassava, Kassave of uun Madelameerikoo Yuca.

Mä detdiar plaant woort büüret, auer a ruter eden wurd kön. Hat wääkst uun a troopen an subtroopen. Uk mä ööder slacher uun det skööl Manihot woort büüret.

Manioko (Manihot esculenta; anke nomizita kom kasavo) esas originale arboreto di la suda regioni di Amerika. Ol esas tuberkulala planto, qua povas travivar per skarsa aquo.

La radiko di manioko, liberigite de la veneno quan olu kontenas, donas farino uzata por facar sorto di pano, e fekulo nutriva (tapiokao). Olua tuberkuli kontenas multega amilo, kalcio ed anke B- e C-vitamini. Anke olua spinatatra folii esas manjebla.

Lo maniòc (Manihot esculenta) es una espècia de plantas dicotiledònas de la familha delas Euphorbiaceae, originària d'America centrala e d'America del Sud, subretot de sud-oèst del bacin amazonian[1],[2]. Es un arbust vivaç qu'es fòrça cultivat coma planta annala dins las regions tropicalas e subtropicalas per sa raiç tuberculizada rica en amidon. Lo tèrme « maniòc » designa mai tanben la quita planta que, per metonimia, sa raiç o la fecula que se n'extrai.

Se consoma mai sovent sas raiças fòrça ricas en glucid e sens glutèn, mas tanben sas fuèlhas en Africa, en Asia e dins lo nòrd del Brasil (per la confeccion del maniçoba). Al nòrd e al nòrd-èst del Brasil, lo mot « farina » (en portugués farinha) desinha d'en primièr la farina de maniòc, e non pas de blat. Aquela farina a pas l'aspècte de la farina de blat: sembla puslèu a una semola seca mai o mens grossa de color anant del jaune viu al gris passant pel blanc. Es de fach una fecula, mot mai adaptat per parlar de la « farina » eissida d'una raiç.

Manihot esculenta es un arbust o arbrilhon podent aténher 5 m de naut, de ram mai sovent tricotomic. Los rams, fragils, de rusca lissa, de color variant del blanc crèma al brun escur, an una mesolha fòrça espessa. Totas las partidas de la planta contenon un latèx blanc. Lo sistèma racinari se constituís de raiças traçantas podent aténher 1 m de long. De raiças realizan un fenomèn de tuberizacion, per creissença secondàrias deguda al cambium, que comença un a dos meses après la plantacion. Las raiças tuberizadas son farinosas e pòdon aténher 50 cm de long. Lor nombre varia segon los cultivars e dels factors environamentals coma lo fotoperiòde, mai sovent se'n compta de 4 a 8 per plant.

Las fuèlhas, altèrnas, an un limbe, de 6 a 25 cm de larg, pregondament palmatipartita, de color verd escur a la faça superiora, glauca a la fàcia inferiora. Lo nombre de lobes, totjorn impar es variable, sovent de 3 a 7 lobes. Lo limbe es a vegadas leugièrament peltat amb 1 a 2 mm de larg del limbe situada jos l'insercion del petiòl. Los lobes son mai sovent oblanceolats (lo lobe median, entièr, mesurant de 6,5 a 15 cm de long sur 2 a 6 cm de larg), progressivament aiguts-acuminats a lor extremitat, retrecits a la basa, en mejana pubescents près de la nervadura mediana o gaireben glabres. Lo petiòl, sovent rogenc, long de 4 a 25 cm, pòrta a sa basa dos estipuls, triangularis-lanceoladas, de 4 a 5 mm de long sus 2 mm de larg, rapidament caducs[3].

L'inflorescéncia es una panicula terminala de 2 a 11 cm de long, sostenduda per de bractèas semblant als estipuls. Las flors masclas e femas son separadas (planta monoïca), las primièras se situant al suc e las segondas, pauc nombrosas, a la base de l'inflorescéncia.

Las flors masclas son portadas per de pedicèlas primas, de 5 mm de long. Lo calici es format de lobes triangulars, subaiguts, glabres de 6 mm de long sus 4 mm de larg. Las etaminas, al nombre de 10 repartidas en doas verticillas, an un filat liure, prim, glabre, blanc, long de 7 mm per la mai longa, de 2,5 mm per las mai longas. Los antèras, pichonas (1,5 mm de long), jauna palla, presentan una tofa apicala. Lo disc receptacle presenta 10 lobes concaus, aiguts. Las flors femes, portadas per de pedicèlas de 7 mm de long, corbas, fan fins a 2,5 cm de diamètre. Los sepals triangulars-ovals, subaguts fan 1 cm de long sus 0,5 cm de larg. L'ovari, ròse, de forma botrioïdala, mesura 2 x 2 mm. Es un ovari trilocular suportat per un disc receptacle glandular de 5 lobes aisidament marcats. Presenta 6 alas estrechas e un estil terminat per un estigmat de 3 lobes. Caduna de las lòtjas conten un ovul simple[4].

Lo fruch es una capsula de forma ellipsoïda a subglobulosa, de 1,3 a 1,7 cm de diamètre. `presenta 6 alas longitudinalas, verdencas, creneladas o ondadas. L'endocarp linhós compta tres lòtjas contenon caduna una grana. Lo fruch se separa en tres còcas pendent la deiscéncia.

Las granas, ellipsoïdas a pentagonalas deprimadas, de 1,1 cm de long sus 5,5 mm de larg e 3,5 mm d'espessor, an una tèsta un pauc brilhanta, gris palle, a vegada pigalhada de negre. Presentan una granda caroncula de 3 mm de larg al tèrme del micropil.

Lo maniòc es una font pauc costosa d'idrats de carbòni, fòrça utilizadas subretot en Amazonia dempuèi de sègles e dins de païses d'Africa tropicala dempuèi de decennias, mas sa consomacion sens la preparacion que cal es font de greus riscs per la santat.

Lo maniòc amar conten de glucosids cianogenics toxics, la linamarina (per 90 %) e la lotaustralina (per 10 %), que quand las cellulas de la planta son damatjadas se descompausan jos l'ef!èch d'enzims, emanant d'acid cianidric.

Aquela descomposicion se realiza en dos estapas: l'idrolisi de la molecul de linamarina, jos l'efièch de la linamarasi, produch de glucòsi e de la cianidrina d'acetona. aquela darrièra molecula, instable, se descompausa en cianur d'idrogèn e en acetona, o espontanèament a un pH superior a 5 o una temperatura superiora a 35 °C, o jos l'efièch d'un autre enzim, l'idroxinitril liasi.

Los glicosids cianogèns son presents dins totes los teissuts de la planta (levat las granas). Lor taus es mai naut dins las fuèlhas (5 g de linamarina per quilograma de pes fresc). Dins las raiças aquel taus es mah fèble e varia de 100 a 500 mg/kg segon los cultivars. Existís pas de cultivar sens glicosids cianogèns[5].

Se decriu quatre tipes de toxicitat segon l'importança de las dòsis de cianur ingeridas[6] :

La cosesson dels tuberculs de maniòc sufisís pas a los far consomables. Se compta de cases d'intoxicacion - plan aurosament rares - avent provocat la mòrt après absorpcion de maniòc mal cuèch, subretot pendent la fregidura.

La carn blanca del tubercul deu èsser ruscada e lavada (o fermentada) puèi secada e cuècha, coma o fan d'amerindians de las regions amazoniana dempuèi de sègles. Un rapòrt de la FAO confirmèt que banhar lo maniòc dins d'aiga pendent 5 jorns abans de lo secar puèi lo manjar permet de mermar fortament lo nivèl de cianur e tanben de lo far comestible[7].

La consomacion de fuèlhas mal bolhidas pòt tanben èsser mortala sempre a causa de la preséncia de traças de cianur; pasmens se los taus de cianur son acceptables, serà transformat dins l'organisme en tiocianat (a condicion que l'alimentacion siá sufisentament rica en sulfurs, que se pòr trapar dins los acids aminats donats per las proteïnas animalas), çò que pòt causar d'ipotiroïdia, veire un gome per blocatge dels receptors a l'iòde sus la glandula tiroïda.

I a una multitud de varietats de maniòc diferentas. Los caractèrs distinctius mai utilizats in vivo son la coloracion e la forma d'organs.

Lo maniòc essent una planta de raiç, lo tèrme « raiç tuberosa » es scientificament mai apropriat que lo tèrme « tubercul ».

Los tuberculs son tanben utilizats per la preparacion de bevenda alcolizada distilladas, coma la bevenda indigèna cauim e la tiquira, cachaça comuna de l'estat brasilian del Maranhão.

La carn dels tuberculs a una color blanquinosa e remembra la fusta per sa textura e sa consisténcia. Après coseson dins l'aiga, sa carn venguda jauna se destrampa. La fregidura la fa cruissenta.

Las fuèlhas son alara consomadas coma de legums, per exemple en Africa, contenon de vitamina A e C.

Lo maniòc cultivat demuèi fòrça temps per las populacions localas foguèt descobèrta pels europèus en 1500 quand lo navigator portugués Cabral acosta lo Brasil amb sos òmes.

Las primièras mencions precisa de maniòc son fachs per Jean de Léry qu'aborda ls còstas del Brasil en 1557, e per manca de recapte tròca d'objèctes manufacturats contra de manjar que la farina de maniòc. De retorn en França Lery publica a La Rochèla lo raconta de son viatge ont fa mencion de la raiça de maniòc. Mai tard una descripcion scientifica se faguèt per Willem Piso dins son obratge Historia Naturalis Brasiliæ publicat en 1648 à Amsterdam. La fabricacion del tapiocà es atestada pel primièr còp dins un libre de John Nieuhoff que demora al Brasil entre 1640 e 1649, parla de la fabricacion d'una mena còca fach de farina de maniòc nomenada tipiacica[8].

L'espècia Manihot esculenta foguèt descricha pel naturalista Heinrich Johann Nepomuk von Crantz[9].

La cultura del maniòc es tocada per diferéncias malautiás bacterianas, viralas e fongicas. En Africa subretot se patís doas malautiás viralas importantas, lo mosaïc african del maniòc e l'estriura bruna del maniòc, e tanben una malautiá fongica, la bacteriòsi vasculara del maniòc[11].

Lo maniòc es la font màger alimentària de fòrça populacions africanas. Tanben, las mendres malautiás pòdon provocar de damtges près de las populacions (faminas en cas de non importacions).

Dempuèi la mitat dels ans 1990, una malautiá apareguda, jol nom de « mosaïc ». Aquela malautiá (un virus) s'espandís plan aisidament e rapidament d'un plant cap a l'autre. La mosca blanca seriá un vector de transmission. La malautiá se desvolopèt dins fòrça païses africans (coma Kenya, Republica de Còngo).

Lo mosaïc fai pèrdre las fuèlhas al plant de maniòc e fa los tuberculs raquitics. Lo principal dangièr per l'òme es de reduire fòrça sa consomacion alimentara.

La produccion de maniòc annala es de gaireben 250 milions de tonas per an. Es una de las tres grandas fonts de polisaccarids, amb lo nham e l'arbre de pin, dins los païses tropicals[12].

Principals païses productors en 2014[13] en MT :

Lo maniòc es utilizat coma semola o coma fecula (tapiocà).

Las fuèlhas al dessús de la planta pòdon èsser trissadas per realizar un legum tradicional.

Los plats mai coneguts son lo foufou, l'attiéké un coscós de maniòc, lo Mpondu a basa de maniòc e de peisson, lo Mpondu-Madesu, a basa de maniòc e de favòls.

Lo maniòc es tanben utilizat per realizar une tortilla, lo cassava, un pan lo chikwangue e de bièras tradicionalas coma la cachiri, lo munkoyo o la mbégé.

Lo maniòc es importat del Brasil al sègle XVI cap a Africa[14], ont es ara cultivat. Al Brasil e en America centrala, s'utiliza fòrça fregits per acompanhar las grasilhadas. En ivèrn, lo bolh de maniòc es fòrça popular. Es tanben utilizat en farina leugièrement rostida per accompanhar de fevòls. Aquela farina es l'ingredient màger de la farofa.

Se pòt prepar los tuberculs los còser, puèi los lavant longament amb d'aiga per levar los rèstes de cianur, e lo fasent secar al solelh.

Lo trissant, a la man o al molin, se realiza una farina blanca nomenada « fofo » dins los dos Còngo. Aquela farina es mesclat amb l'aiga bolhissenta a egala proporcion e constituís un aliment qu'accompanha los plats en salsa. Se pòt tanben èsser donada a d'enfants joves. Le fofo a una volor calorica seca de 250 a 300 Cal, es a dire près de la mitat que quand es pasta.

Un autre biais de lo consomar es en pans de maniòc (nomenats « chikwangue » en Republica Democratica del Còngo, « Bibôlô » al Cameron, e « mangbèré » en Centrafrica). Son rics en cellulòsa, consistissents, mas fòrça pauc noirissents. Lor prètz fòrça abordable favoriza lor consomacion de granda escala. Se recomanda de mastegar plan per aver pas de problèma de digestion.

A Maurici lo maniòc se produch e es consomat jos forma de bescuèchs, mai sovent aromatizats, amb canèla, crèma anglesa, cocò o encara sesam. Lo maniòc se pren jos forma d'una sopa o de vianda de buòu, pol (nomenats katkat manioc).

Las fuèlhas de maniòc son tanben consomadas amb de ris, en Republica de Còngo e en Republica Democratica de Còngo jol nom de mpondu, saka-saka o « ngunza » o « ngoundja » en Centrafrica. Lo matapa, plat tipic de Moçambic, (lo vatapá al Brasil), se prepara amb las jovas fuèlhas de maniòc plegadas amb d'alh e la farina tirada dels tuberculs, cuèchs amb de crancs o de cambaròtas. Als Comòras jol nom de mataba, las fuèlhas s'acompanha amb un talh de peisson.

En Còsta d'Evòri, lo maniòc se consoma jos forma de semola cuècha amb vapor, çò que se nomena l'attiéké. L'attiéké es un plat nacional, supretot consomat dins las regions sud del país. Es sovent acompanhat de salça locala. Lo maniòc de pòt prene jos forma de pan de maniòc nomenat foto de maniòc o de plakali, subretot constituit de substéncia amidonada. L'attiéké se consuna fresc de preferéncia. Se consèrva e s'expòrta o se comercializa jos forma seca. La produccion de maniòc comença a se far jos forma industriala per de pichonas unitats de produccion d'attiéké.

titre mancanttitre » mancant, sur Plant Resources of Tropical Africa (PROTA). titre mancant, 190 p. (ISBN 9789781310454) titre » mancant, sur CIRAD. titre » mancant, sur faostat3.fao.org Lo maniòc (Manihot esculenta) es una espècia de plantas dicotiledònas de la familha delas Euphorbiaceae, originària d'America centrala e d'America del Sud, subretot de sud-oèst del bacin amazonian,. Es un arbust vivaç qu'es fòrça cultivat coma planta annala dins las regions tropicalas e subtropicalas per sa raiç tuberculizada rica en amidon. Lo tèrme « maniòc » designa mai tanben la quita planta que, per metonimia, sa raiç o la fecula que se n'extrai.

Se consoma mai sovent sas raiças fòrça ricas en glucid e sens glutèn, mas tanben sas fuèlhas en Africa, en Asia e dins lo nòrd del Brasil (per la confeccion del maniçoba). Al nòrd e al nòrd-èst del Brasil, lo mot « farina » (en portugués farinha) desinha d'en primièr la farina de maniòc, e non pas de blat. Aquela farina a pas l'aspècte de la farina de blat: sembla puslèu a una semola seca mai o mens grossa de color anant del jaune viu al gris passant pel blanc. Es de fach una fecula, mot mai adaptat per parlar de la « farina » eissida d'una raiç.

Manyòk dous se yon plant. Li nan fanmi plant Kategori: Euphorbiaceæ. Non syantifik li se Manihot cassava O.F.Cook & G.N.Collins syn. M. esculenta Crantz.

Istwa

Manyòk dous se yon plant. Li nan fanmi plant Kategori: Euphorbiaceæ. Non syantifik li se Manihot cassava O.F.Cook & G.N.Collins syn. M. esculenta Crantz.

Muhogo (Kiing. cassava) ni mmea wa jenasi Manihot na chakula muhimu katika Afrika, Amerika Kusini na nchi za Asia Kusini. Sehemu ya kuliwa ni hasa viazi vyake (mizizi minene au mahogo) vilivyo na wanga nyingi halafu pia majani yake yenye protini na vitamini.

Kuna aina kadhaa za muhogo zinazotofautiana hasa katika kiwango cha sianidi (cyanide) ndani yake. Sianidi ni sumu inayoandaliwa ndani ya mmea kwa umbo la kemikali linamarin. Linamarin hubadilika kuwa sianidi.

Viwango vya sianidi vinatofautiana kati ya spishi mbalimbali za muhogo. Aina zenye kiwango kidogo sana hazina matatizo lakini kwa jumla zao linatakiwa kuandaliwa kabla ya kuliwa.

Dawa ya sianidi hupotea kwa kuacha mizizi katika maji kwa siku mbili tatu. Njia nyingine ni upishi kwa joto kali kwa mfano kukaanga katika mafuta. Njia nyingine inayotumiwa hasa Afrika ya Magharibi ni kusaga viazi na kukoroga unga katika maji; baada ya masaa kadhaa maji hubadilishwa na uji unapikwa kuwa aina ya ugali.

Muhogo (Kiing. cassava) ni mmea wa jenasi Manihot na chakula muhimu katika Afrika, Amerika Kusini na nchi za Asia Kusini. Sehemu ya kuliwa ni hasa viazi vyake (mizizi minene au mahogo) vilivyo na wanga nyingi halafu pia majani yake yenye protini na vitamini.

Ko e mānioke ko e fuʻu ʻakau siʻi ia, mo e aka fakameʻatokoni.

Pšawy maniok (Manihot esculenta) je rostlina ze swójźby wjelkomlokowych rostlinow (Euphorbiaceae).

Wědomnostne mě Mánihot póchada pśez starše francojske słowo manihot (něnto manioc) z tupiskego słowa mandioca a guaraniskego słowa mandio „na škrobje bogate kule pśi M. esculenta“.[1]

Pšawy maniok (Manihot esculenta) je rostlina ze swójźby wjelkomlokowych rostlinow (Euphorbiaceae).

Rogo (róógò[1]) (Manihot esculenta)

Rumu icha Yuka (Manihot esculenta) nisqaqa huk allpapi puquq chakra yuram.

Sampeu atawa dangdeur (sok disebut ogé hui tangkal; basa Inggris: cassava) nyaéta tangkal ti kulawarga Euphorbiaceae.[1] Beutina dipikawanoh minangka kadaharan poko panghasil karbohidrat sarta daunna minangka sayuran.[2] Sampeu tumuwuh di daérah tropis jeung daérah subtropis.[3]

Sampeu mangrupa beuti atawa akar tangkal anu panjang jeung boga garis tengah rata-rata 2–3 cm sarta panjang 50–80 cm, gumantung kana jinis sampeu anu dipelak.[4] Daging beutina boga warna bodas atawa semu konéng.[4] Beuti sampeu henteu bisa lila disimpen sanajan ditempatkeun dina lomari és.[4] Gambaran karuksakan ditandaan ku kaluarna warna biru kolot alatan kawangunna asam sianida anu boga sipat racun pikeun manusa.[4]

Beuti sampeu mangrupa sumber énergi anu beunghar ku karbohidrat tapi kacida kurang ngandung protéin.[4] Sumber protéin anu alus malahan aya dina daun sampeu alatan ngandung asam amino métionin.[4]

Jinis sampeu Manihot esculenta mimiti dipikawanoh di Amérika Kidul, saterusna dibudidayakeun dina mangsa pra-sejarah di Brasil sarta Paraguay.[5] Wangun-wangun modéren tina spésiés anu geus dibudidayakeun bisa kapanggih tumuwuh liar di Brasil kidul.[5]

Produksi sampeu dunya dikira-kira ngahontal 184 juta ton dina taun 2002.[5] lolobana produksi dihasilkeun di Afrika 99,1 juta ton sarta 33,2 juta ton di Amérika Latin sarta Kapuloan Karibia.[5]

Sampeu dipelak sacara komérsial di wewengkon Indonésia (waktu éta Hindia Walanda) dina kira-kira taun 1810 Payer, M. HBI weltweit. 5.3. Zur Geschichte Indonesiens. Édisi 1997-03-18. Diaksés 18 Méi 2007, sanggeus saméméhna diwanohkeun ku urang Portugis dina abad ka-16 (beunang mawa ti Brasil).[5]

Beuti akar sampeu réa ngandung glukosa sarta bisa didahar atah-atah.[6] Rasana rada amis, aya ogé anu pait gumantung kana kandungan racun glukosida anu bisa nyieun asam sianida.[6] Beuti anu rasana amis ngahasilkeun paling saeutik 20 mg HCN pér kilogram beuti akar anu seger kénéh, sarta 50 kali leuwih réa dina beuti anu rasana pait.[6] Dina jinis sampeu anu amis, prosés ngasakkeun pohara diperlukeun pikeun nurunkeun kadar racunna.[6] Tina beuti ieu bisa ogé dijieun tipung aci.[6]

Sampeu dikokolakeun ku sagala rupa cara, sampeu réa dipaké dina sagala rupa macem asakan.[6] Dikulub pikeun ngagantikeun kentang, sarta palengkep asakan.[6] Tipung sampeu bisa dipaké pikeun ngaganti tipung gandum, alus pikeun panyandang alergi.[6]

Sampeu ilahar dipaké minangka kadaharan pikeun ingon-ingon di nagara-nagara kawas di Amérika Latin, Karibia, Tiongkok, Nigéria sarta Éropa.[7]

Sampeu atawa dangdeur (sok disebut ogé hui tangkal; basa Inggris: cassava) nyaéta tangkal ti kulawarga Euphorbiaceae. Beutina dipikawanoh minangka kadaharan poko panghasil karbohidrat sarta daunna minangka sayuran. Sampeu tumuwuh di daérah tropis jeung daérah subtropis.

Η Μανιότη η εδώδιμος (Manihot esculenta) (κοινώς ονομάζεται κασάβα,[1] μανιόκα,[1] ދަނދިއަލުވި,[2] στις Μαλδίβες το αποκαλούν γιούκα), είναι ξυλώδης θάμνος που ευδοκιμεί στη Νότια Αμερική από την οικογένεια της γαλατσίδας, τις Ευφορβίδες. Καλλιεργείται ευρέως ως ετήσια καλλιέργεια στις τροπικές και υποτροπικές περιοχές για την εδώδιμη αμυλούχα κονδυλώδη ρίζα, μια σημαντική πηγή υδατανθράκων. Αν και συχνά αποκαλείται γιούκα, στα Ισπανικά και στις Ηνωμένες Πολιτείες, διαφέρει από το γιούκα, έναν άσχετο οπωροφόρο θάμνο στην οικογένεια Ασπαραγοειδή (Asparagaceae). Η μανιόκα, όταν αποξηρανθεί σε εκχύλισμα σκόνης (ή περλέ), ονομάζεται ταπιόκα· η νιφαδοειδής έκδοσή της η οποία έχει υποστεί ζύμωση, ονομάζεται garri.

Η κασάβα είναι η τρίτη μεγαλύτερη πηγή τροφίμων υδατανθράκων στις τροπικές περιοχές, μετά το ρύζι και τον αραβόσιτο.[3][4] Η μανιόκα είναι μια βασική τροφή στον αναπτυσσόμενο κόσμο, παρέχοντας τη βασική διατροφή για πάνω από μισό δισεκατομμύριο ανθρώπους.[5] Είναι μια από τις πιο ανθεκτικές στην ξηρασία φυτικές ποικιλίες, ικανή να αναπτύσσεται σε περιθωριακά εδάφη. Η Νιγηρία είναι η μεγαλύτερη παραγωγός μανιόκα στον κόσμο, ενώ η Ταϊλάνδη είναι ο μεγαλύτερος εξαγωγέας ξερής μανιόκα.

Η κασάβα ταξινομείται είτε ως γλυκιά είτε ως πικρή. Όπως και άλλες ρίζες και κόνδυλοι, τόσο οι πικρές όσο και οι γλυκές ποικιλίες μανιόκα, περιέχουν αντι-θρεπτικούς παράγοντες και τοξίνες, με τις πικρές ποικιλίες να περιέχουν πολύ μεγαλύτερες ποσότητες.[6] Θα πρέπει να είναι κατάλληλα προετοιμασμένοι πριν από την κατανάλωση, η ακατάλληλη προετοιμασία της κασάβα μπορεί να αφήσει αρκετά υπολείμματα κυανίου που προκαλούν οξεία δηλητηρίαση από το κυάνιο,[7] βρογχοκήλη, ακόμη και αταξία ή μερική παράλυση.[6] Οι πιο τοξικές ποικιλίες κασάβα είναι εφεδρική πηγή (μια "καλλιέργεια ασφάλειας των τροφίμων") σε περιόδους λιμού σε κάποιες περιοχές.[6] Οι αγρότες συχνά προτιμούν τις πικρές ποικιλίες, επειδή αποτρέπουν τα παράσιτα, τα ζώα και τους κλέφτες.[8]

Η ρίζα μανιόκα είναι μακρυά και κωνική, με σταθερή, ομοιογενή σάρκα εγκιβωτισμένη σε μια αποσπώμενη κρούστα, πάχους περίπου 1 χιλ., τραχιά και καφέ στο εξωτερικό. Οι εμπορικές ποικιλίες μπορεί να είναι 5 έως 10 εκ. (2,0 3,9 in) σε διάμετρο στην κορυφή και μήκους περίπου 15 έως 30 εκ. (5,9 στα 11,8 in). Μια ξυλώδης αγγειακή δέσμη, εκτείνεται κατά μήκος της ρίζας του άξονα. Η σάρκα μπορεί να είναι κατάλευκη ή κιτρινωπή. Οι ρίζες της μανιόκα είναι πολύ πλούσιες σε άμυλο και περιέχουν σημαντικές ποσότητες ασβεστίου (50 mg/100g), φωσφόρου (40 mg/100g) και βιταμίνη C (25 mg/100g). Ωστόσο, είναι φτωχές σε πρωτεΐνες και άλλα θρεπτικά συστατικά. Σε αντίθεση, τα φύλλα μανιόκα είναι μια καλή πηγή πρωτεΐνης (πλούσια σε λυσίνη), αλλά ανεπαρκή σε αμινοξύ μεθειονίνη και ενδεχομένως, τρυπτοφάνη.[9]

Άγριοι πληθυσμοί της Μ. η εδώδιμος (M. esculenta) υποείδος flabellifolia, φαίνεται να είναι ο πρόγονος των εξημερωμένων μανιόκα, επικεντρώνονται στη δυτική-κεντρική Βραζιλία, όπου ήταν πιθανό να πρωτο-εξημερώθηκε περισσότερα από 10.000 χρόνια πριν.[11] Μορφές των συγχρόνων εξημερωμένων ειδών μπορούν επίσης να βρεθούν στη φύση, στη νότια Βραζιλία. Κατά το 4600 π.Χ., γύρη μανιόκα εμφανίζεται στα πεδινά του Κόλπου του Μεξικού, στον αρχαιολογικό χώρο του San Andrés.[12] Η παλαιότερη άμεση απόδειξη της καλλιέργειας μανιόκα, προέρχεται από την Joya de Cerén, στο Ελ Σαλβαδόρ, τοποθεσία των Μάγια ηλικίας 1.400 ετών.[13] Με την υψηλή τροφική δυναμική, είχε γίνει βασική τροφή των ιθαγενών πληθυσμών της βόρειας Νότιας Αμερικής, της νότιας Κεντρικής Αμερικής και της Καραϊβικής από την εποχή της Ισπανικής κατάκτησης. Η καλλιέργειά του συνεχίστηκε από τους Πορτογάλους και Ισπανούς αποικιοκράτες.

Η κασάβα ήταν βασικό είδος διατροφής για τους προ-Κολομβιανούς λαούς στην Αμερική και συχνά απεικονίζεται στην τέχνη των ιθαγενών. Ο λαός των Μότσε συχνά απεικόνιζε γιούκα στα κεραμικά του.[14]

Η μαζική παραγωγή ψωμιού κασάβα, έγινε η πρώτη Κουβανική βιομηχανία που δημιουργήθηκε από τούς Ισπανούς.[1] Πλοία που αναχωρούσαν για την Ευρώπη από τους Κουβανέζικους λιμένες όπως την Αβάνα, Σαντιάγκο, Bayamo και Baracoa, όχι μόνο μετέφεραν προϊόντα προς την Ισπανία, οι Ισπανοί, χρειαζόντουσαν να αναπληρώσουν επίσης, τα πλοία τους με αποξηραμένο κρέας, νερό, φρούτα και μεγάλες ποσότητες ψωμιού κασάβα. [2] Ο καιρός στην Κούβα δεν ήταν κατάλληλος για την φύτευση σιταριού και η ταπιόκα δεν θα γινόταν τόσο σύντομα μπαγιάτικη, όπως το κανονικό ψωμί.

Η κασάβα εισήχθη από τη Βραζιλία στην Αφρική, τον 16ο αιώνα, από τους Πορτογάλους εμπόρους. Ο αραβοσίτος και η μανιόκα είναι τώρα σημαντικά βασικά τρόφιμα, αντικαθιστώντας γηγενείς καλλιέργειες της Αφρικής.[15] Η κασάβα μερικές φορές περιγράφεται ως το 'ψωμί από τους τροπικούς',[16] αλλά δεν πρέπει να συγχέεται με το τροπικό και ισημερινό αρτόδεντρο (Encephalartos), τον αρτόκαρπο (Artocarpus altilis) ή τον Αφρικανικό αρτόκαρπο (Treculia africana).

Η παγκόσμια παραγωγή της ρίζας κασάβα εκτιμάται ότι το 2002, είναι 184 εκατομμύρια τόνοι, αυξανόμενη σε 230 εκατομμύρια τόνους το 2008.[17] Η πλειονότητα της παραγωγής το 2002 ήταν στην Αφρική, όπου καλλιεργήθηκαν 99,1 εκατομμύρια τόνοι· 51,5 εκατομμύρια τόνοι καλλιεργήθηκαν στην Ασία· και 33,2 εκατομμύρια τόνοι στη Λατινική Αμερική και την Καραϊβική, ειδικότερα την Τζαμάικα. Η Νιγηρία είναι ο μεγαλύτερος παραγωγός στον κόσμο της κασάβα. Ωστόσο, με βάση τα στατιστικά στοιχεία από τον FAO των Ηνωμένων Εθνών, η Ταϊλάνδη είναι η μεγαλύτερη χώρα εξαγωγής αποξηραμένης μανιόκα, με συνολικά το 77% της παγκόσμιας εξαγωγής το 2005. Η δεύτερη μεγαλύτερη χώρα εξαγωγής, είναι το Βιετνάμ, με 13,6%, ακολουθούμενη από την Ινδονησία (5,8%) και την Κόστα Ρίκα (2,1%).

Το 2010, η μέση απόδοση των καλλιεργειών μανιόκα σε ολόκληρο τον κόσμο ήταν 12,5 τόνους ανά εκτάριο. Παγκοσμίως, τα πιο παραγωγικά κτήματα μανιόκα ήταν στην Ινδία, όπου το 2010, είχαν εθνικό μέσο όρο απόδοσης, 34,8 τόνους ανά εκτάριο.[18]

Οι μανιόκα, τα γιαμ (yam) (Dioscorea spp.) και οι γλυκοπατάτες (Ipomoea batatas),[Σημ. 1] είναι σημαντικές πηγές τροφίμων στις τροπικές περιοχές. Το φυτό κασάβα δίνει την τρίτη υψηλότερη απόδοση σε υδατάνθρακες ανά καλλιεργούμενη έκταση μεταξύ των καλλιεργούμενων φυτών, μετά το ζαχαροκάλαμο και τα ζαχαρότευτλα. [19] Η κασάβα παίζει στις αναπτυσσόμενες χώρες, έναν ιδιαίτερα σημαντικό ρόλο στον τομέα της γεωργίας, ιδίως στην υποσαχάρια Αφρική, επειδή ευδοκιμεί σε φτωχά εδάφη, με χαμηλή βροχόπτωση και επειδή είναι πολυετές (perennial)[Σημ. 2] που μπορεί να συγκομισθεί, όπως απαιτείται. Η μεγάλη περίοδος συγκομιδής της, της επιτρέπει να ενεργήσει ως αποθεματικό κατά του λιμού και είναι ανεκτίμητη στη διαχείριση των εργασιακών χρονοδιαγραμμάτων. Προσφέρει ευελιξία στους φτωχούς σε πόρους αγρότες, γιατί χρησιμεύει είτε ως προϊόν διαβίωσης, είτε ως αποδοτική καλλιέργεια.[20]

Καμία ήπειρος δεν εξαρτάται τόσο από τις ριζωματώδεις και κονδυλώδεις καλλιέργειες στη διατροφή του πληθυσμού της, όσο η Αφρική. Στις υγρές και υπόυγρες (subhumid) περιοχές της τροπικής Αφρικής, είναι είτε μια αρχική βασική τροφή είτε μια δευτερεύουσα βασική τροφή (costaple). Στην Γκάνα, για παράδειγμα, οι μανιόκα και τα γιαμ (yam), κατέχουν σημαντική θέση στην αγροτική οικονομία και συνεισφέρουν περίπου το 46% του γεωργικού ακαθάριστου εγχώριου προϊόντος. Στην Γκάνα, οι συγκεντρώσεις ημερήσιας θερμιδικής πρόσληψης κασάβα, ανέρχονται στο 30% και καλλιεργείται σχεδόν από κάθε αγροτική οικογένεια.[Σημ. 3]

Στην Ταμίλ Ναντού, Ινδία, υπάρχουν πολλά εργοστάσια επεξεργασίας μανιόκα, κατά μήκος της Εθνικής Οδού 68 μεταξύ Thalaivasal και Attur. Η κασάβα καλλιεργείται ευρέως και τρώγεται ως βασικό τρόφιμο στην Άντρα Πραντές και στην Κεράλα. Στο Ασσάμ είναι μια σημαντική πηγή υδατανθράκων, ειδικά για τους ιθαγενείς των ημιορεινών περιοχών.

Στην υποτροπική περιοχή της νότιας Κίνας, η μανιόκα είναι η πέμπτη μεγαλύτερη καλλιέργεια σε επίπεδο παραγωγής, μετά από το ρύζι, την πατάτα, το ζαχαροκάλαμο και τον αραβόσιτο. Η Κίνα είναι επίσης και η μεγαλύτερη εξαγωγική αγορά για τη μανιόκα που παράγεται στο Βιετνάμ και την Ταϊλάνδη. Πάνω από το 60% της παραγωγής μανιόκα στην Κίνα, ευρίσκεται συγκεντρωμένη σε μια ενιαία επαρχία την Κουανγκσί, κατά μέσο όρο πάνω από 7 εκατομμύρια τόνους ετησίως.

Σύμφωνα με τα στατιστικά δεδομένα από τη Διεθνή Οργάνωση Τροφίμων και Γεωργίας, οι 20 κυριότερες χώρες παραγωγής κασάβα κατά το 2012, ήσαν οι παρακάτω:

Τα αλκοολούχα ποτά που παρασκευάζονται από τη μανιόκα περιλαμβάνουν το: Cauim και tiquira (Βραζιλία), kasiri (Υποσαχάρια Αφρική), Impala (Μοζαμβίκη), masato (Περουβιανή τσίτσα Αμαζονίας), parakari ή kari (Γουιάνα), nihamanchi (Νότια Αμερική), επίσης γνωστό και ως nijimanche (Εκουαδόρ και Περού), ö döi (chicha de yuca, Ngäbe-Bugle, Παναμά), sakurá (Βραζιλία, Σουρινάμ).

Τα πιάτα με βάση την κασάβα καταναλώνονται όπου καλλιεργείται το φυτό, κάποια έχουν σημασία περιφερειακή ή εθνική.[21] Η μανιόκα πρέπει να μαγειρευτεί σωστά, ώστε να αποτοξινωθεί πριν φαγωθεί.

Η κασάβα μπορεί να μαγειρευτεί με πολλούς τρόπους. Η ρίζα από τη γλυκιά ποικιλία έχει μια λεπτή γεύση και μπορεί να αντικαταστήσει τις πατάτες. Χρησιμοποιείται στα cholent (ραγού),[Σημ. 4] σε ορισμένα νοικοκυριά. Αυτό μπορεί να γίνει σε αλεύρι που χρησιμοποιείται στο ψωμί, κέικ και μπισκότα. Στη Βραζιλία, οι αποτοξινωμένες μανιόκα αλέθονται και ψήνονται να στεγνώσουν, συχνά σε σκληρό ή τραγανό γεύμα, γνωστό ως farofa το οποίο χρησιμοποιείται ως καρύκευμα, ψημένο στο βούτυρο ή τρώγεται μόνο του ως ένα δευτερεύον πιάτο.