pt-BR

nomes no trilho de navegação

L'escheríchia coli (Escherichia coli, pronunciat /eʃe'ɾikia 'kɔli/ i abreujat E. coli habitualment) és una de les principals espècies d'eubacteris que viuen a la part més baixa dels intestins dels animals de sang calenta, incloent-hi ocells i mamífers i són necessaris per a la correcta digestió dels aliments. La seva presència en l'aigua subterrània és un indicador comú de la contaminació fecal ("Entèric" és un adjectiu que descriu els organismes que viuen en els intestins. "Fecal" és l'adjectiu per als organismes que viuen en la femta, de manera que amb freqüència s'empra com a sinònim d'"entèric.") El nom prové del seu descobridor, Theodor Escherich. Pertany a la família de les enterobacteriàcies, i és emprada com a organisme model per als bacteris en general.

De mitjana, un humà treu diàriament amb la femta entre cent mil milions i un bilió d'E. coli. Tots els diferents tipus de coli fecals i tots els bacteris semblants que viuen en el sòl. (en el sòl amb plantes marcint-se el més comú és l'Enterobacter aerogenes) són agrupades juntes sota el nom "coliforme" (que vol dir semblant a coli"). Tècnicament el "grup coliforme" es defineix com el conjunt de bacteris aerobis o anaerobis facultatius, no esporolables, gram-negatius, en forma de bacil i que fermenten lactosa amb producció de gas (els animals eliminen aquest gas en forma de flatulència).

Actualment es considera que l'E coli és l'organisme model i per tant l'ésser viu sobre el que se'n té més coneixement biomolecular. A més a més, gràcies al seguit d'eines desenvolupades al voltant de la seva bioquímica ha demostrat ser altament manipulable al laboratori. Per això mateix és l'eubacteri més emprat per fer als experiments consistents en estudiar les propietats de les biomolècules. Té capacitat per introduir una gran quantitat de proteïnes i fins i tot vies metabòliques senceres dins del seu metabolisme i de produir-les de forma barata en massa, gràcies als seus pocs requeriments del medi. Les seves limitacions són les cadenes d'ADN amb palíndroms, que no és capaç de manipular i que no té capacitat de processar proteïnes eucariotes que requereixin modificacions post-transcripcionals com ara glucosidacions. Actualment és per exemple el principal productor d'insulina.

L'alt coneixement que se'n té ha fet que sigui l'ésser viu que tingui més tecnologia desenvolupada amb la fi de modificar-lo com tota mena de fags i plasmidis. També hi ha moltes eines per tal de conservar i replicar informació com els BAC que es varen fer servir moltíssim en les genoteques implicades en la seqüenciació del genoma humà.

Hi ha, tanmateix, tres situacions en què la E. coli pot causar malalties:

La majoria no produeixen patologia i viuen a l'intestí de l'home i mamífers sense causar malaltia com a flora normal intestinal. El tipus de patologia més freqüent que produeixen són les infeccions del tracte urinari i les gastroenteritis. Moltes poden actuar com a patogen oportunista. E. coli és el principal agent causal de septicèmies i també produeix un tipus de meningitis. Diferents grups de soques produeixen diferents tipus d'infecció i patogènia:

Produeix una diarrea tipus còlera encara que menys severa (diarrea del viatger). La seua patogènia es deu a la producció de toxines. Les ETEC actuen a nivell de mucosa de l'intestí prim a la qual es fixa per mitjà d'unes adhesines fimbriades.

Provoca una diarrea persistent en infants. Forma agregats a la superfície de la mucosa intestinal.

Es desenvolupa a l'intestí prim on forma una alteració de l'estructura de les microvellositats. Els bacteris apareixen enganxats a la mucosa en unes projeccions. La penetració de la mucosa per les cèl·lules succeeix de forma esporàdica i produeix efectes importants sobre la fisiologia de la cèl·lula infectada com l'activació de la tirosina-cinasa i l'increment dels nivells de calci.

Important causa de brots epidèmics de gastroenteritis hemorràgica en països desenvolupats (carn picada). Dosi d'infecció molt baixa (quantitats molt petites poden comportar brots epidèmics seriosos). Similars a la de les EPEC però produeix símptomes semblants a Shigella, produeixen una toxina tipus Shiga (Verotoxina) que pot produir la síndrome hemolítica-urèmica (HUS). S'ha convertit en l'amenaça, a nivell d'infeccions gastrointestinals, més greu als països desenvolupats.

Patologia indistingible de la Shigella però no es produeixen toxines Shiga.

Responsables del 80% d'infeccions urinàries. Freqüents en dones en edat fèrtil. Pot afectar bufeta i uretra (cistitis) o ronyó (pielonefritis). Les infeccions urinàries són el segon tipus d'infecció més freqüent. També són freqüents en infants de menys de 5 anys (d'ambdós sexes). S'ha demostrat l'actuació d'adhesines que permeten adherència a la mucosa del tracte urinari. L'acció inflamatòria localitzada dels lipopolisacàrids (LPS) probablement té un paper important.

En els camps relacionats amb la purificació de l'aigua i tractament d'aigües residuals l'E.coli va ser escollida des de molt d'hora en el desenvolupament de la tecnologia com a "indicador" del nivell de pol·lució de l'aigua mitjançant l'Índex de Coliformes per controlar-ne la contaminació fecal humana. Les raons principals per emprar l'E. coli són que hi ha un munt de coliformes en la femta humana que són patògens (com la Salmonella typhi, que causa el tifus), i l'E. coli és normalment inofensiva, de manera que no es pot escapar de laboratori i fer mal algú. Pot ser enganyós emprar l'E. coli com a indicador de la contaminació fecal humana, ja que hi ha altres ambients en els quals l'E. coli creix bé, com per exemple les fàbriques de paper.

Filogènia de les soques de l'Escherichia coliL'escheríchia coli (Escherichia coli, pronunciat /eʃe'ɾikia 'kɔli/ i abreujat E. coli habitualment) és una de les principals espècies d'eubacteris que viuen a la part més baixa dels intestins dels animals de sang calenta, incloent-hi ocells i mamífers i són necessaris per a la correcta digestió dels aliments. La seva presència en l'aigua subterrània és un indicador comú de la contaminació fecal ("Entèric" és un adjectiu que descriu els organismes que viuen en els intestins. "Fecal" és l'adjectiu per als organismes que viuen en la femta, de manera que amb freqüència s'empra com a sinònim d'"entèric.") El nom prové del seu descobridor, Theodor Escherich. Pertany a la família de les enterobacteriàcies, i és emprada com a organisme model per als bacteris en general.

De mitjana, un humà treu diàriament amb la femta entre cent mil milions i un bilió d'E. coli. Tots els diferents tipus de coli fecals i tots els bacteris semblants que viuen en el sòl. (en el sòl amb plantes marcint-se el més comú és l'Enterobacter aerogenes) són agrupades juntes sota el nom "coliforme" (que vol dir semblant a coli"). Tècnicament el "grup coliforme" es defineix com el conjunt de bacteris aerobis o anaerobis facultatius, no esporolables, gram-negatius, en forma de bacil i que fermenten lactosa amb producció de gas (els animals eliminen aquest gas en forma de flatulència).

Escherichia coli (původním názvem Bacterium coli) je gramnegativní fakultativně anaerobní spory netvořící tyčinkovitá bakterie pohybující se pomocí bičíků. Spadá pod čeleď Enterobacteriaceae, jež také zahrnuje mnoho patogenních rodů mikroorganismů. E. coli patří ke střevní mikrofloře teplokrevných živočichů, včetně člověka. Z tohoto důvodu je její přítomnost v pitné vodě indikátorem fekálního znečištění. Člověku je jako součást přirozené mikroflory prospěšná, jelikož produkuje řadu látek, které brání rozšíření patogenních bakterií (koliciny) a podílí se i na tvorbě některých vitamínů (např. vitamín K). Byla objevena německo-rakouským pediatrem a bakteriologem Theodorem Escherichem v roce 1885[1].

E. coli patří k nejlépe prostudovaným mikroorganismům, jelikož je modelovým organismem pro genové a klinické studie. Joshua Lederberg jako první r. 1947 pozoroval a popsal na bakterii E. coli výměnu genetického materiálu tzv. konjugaci[2].

E. coli je nesporotvorná tyčinka, jež se pohybuje pomocí bičíku. Bakterie dosahuje délky 2–3 μm a šířky 0,6 μm. Některé druhy mohou tvořit slizovité obaly, jež jsou složeny z polysacharidů. Na svém povrchu nese dva typy fimbrií. První typ fimbrií se skládá z kyselého hydrofobního proteinu tzv. fimbrinu. Umožňuje bakterii přichytit se na epitel hostitele a následně jej kolonizovat. Kolonizace je usnadněna vysokým počtem fimbrií prvního typu na buňku (100-1000 ks/buňka). Tyto fimbrie jsou vysoce antigenní, jelikož obsahují tzv. F antigeny. Druhým typem fimbrií jsou tzv. sex pili, jež hrají důležitou úlohu při konjugaci.

Bakterie se může pohybovat pomocí bičíků. Ty jsou složeny z tzv. flagelinu (na lysin bohatý protein). Bičíky jsou stejně jako fimbrie vysoce antigenní, a to díky tzv. H antigenům. Na povrchu bakterie se při stresových podmínkách dále mohou tvořit polysacharidové kapsule, jež obsahují tzv. K a M antigeny.

Vnější membrána je pokryta lipopolysacharidem a skládá se z lipidové dvojvrstvy, kde je ukotveno množství membránových proteinů. Mezi proteiny, které tvoří póry, patří poriny Omp C, Omp F a Pho E. Poriny slouží jako vstupní a výstupní kanály pro buněčné metabolity a pro příjem vitaminů z okolí.

Prostor mezi vnější membránou a buněčnou stěnou se nazývá periplazmatický. Vyskytují se zde např. proteiny vázající aminokyseliny či cukry, enzymy degradující antibiotika (beta-laktamasy).

Buněčná stěna E. coli (jakožto zástupce gramnegativních bakterií) se skládá z tenké vrstvy peptidoglykanu, jenž je zodpovědný za rigidní tvar buňky. Pod vrstvou peptidoglykanu se nalézá cytoplazmatická membrána. Ta se skládá především z proteinů (70%), lipopolysacharidů a fosfolipidů. Je v ní lokalizováno mnoho biochemických pochodů, např. dýchací řetězec a syntéza ATP.

Cytoplazma bakteriální buňky je viskózní vodný roztok, jež obsahuje rozpuštěné anorganické a organické látky. Nachází se zde množství ribozomů (cca 40% hmotnosti celé buňky), díky nimž je proteosyntéza a dělení bakteriálních buněk velice rychlé. Při optimálních podmínkách (37 °C, dostatek živin) je doba generace zhruba 20 min. Bakteriální ribozomy jsou menší než eukaryotní. Mají sedimentační konstantu 70S.

Dále se zde nalézá molekula bakteriální DNA, ve které je uložena veškerá dědičná informace bakterie. Velikost DNA u E. coli K-12 je zhruba 4700 kbp a kóduje cca 4400 proteinů.[3] Cytoplazma bakterií na rozdíl od cytoplazmy eukaryot neobsahuje membránové organely.

E. coli je fakultativní anaerob, tj. využívá respirační i kvasný metabolismus (fermentace) pro přísun energie. E. coli jako chemoheterotrof je schopná využívat množství cukrů i aminokyselin jako zdroj uhlíku, nejrychleji však roste na glukose. Za anaerobních podmínek E. coli utilizuje glukosu za vzniku laktátu, sukcinátu, acetátu i ethanolu. Za aerobních podmínek je glukosa využita efektivněji a konečnými produkty je především oxid uhličitý. E. coli produkuje indol, avšak neroste na citrátu a neprodukuje sirovodík. Je kataláza-pozitivní, oxidáza-negativní. Těchto vlastností se využívá při její identifikaci pomocí tzv. Enterotestu[4]. E. coli je schopná růst za teploty 8 °C-48 °C, avšak optimální teplota je 37 °C. Rozsah pH pro růst je pH6-pH8[3].

E. coli můžeme taxonomicky dělit dle antigenních struktur na sérotypy. Mezi hlavní struktury patří somatické O antigeny (lipopolysacharid), jichž je 170 typů, a kapsulární K antigeny (80 typů), dalšími strukturami jsou např. H antigeny (flagelární proteiny) a F antigeny (bílkoviny fimbrií)[3].

E. coli je jednou z nejčastěji se vyskytujících bakterií v klinických vzorcích. Její přítomnost je u člověka fyziologická pouze ve střevech jako součást střevní mikroflory. Avšak patologicky se může vyskytovat i v krevních vzorcích, a být tak původcem bakterémie. Často způsobuje nosokomiální infekce tj. infekce získané v nemocnicích. Bakteriální infekce se léčí podáváním antibiotik. V dnešní době však nalézáme stále větší množství kmenů bakterií, které jsou k podávaným antibiotikům rezistentní.

Patogenní kmeny způsobují dva typy onemocnění. Prvním je extraintestiální onemocnění, kdy jsou napadeny především močové cesty, dochází k infekci ran a jejich hnisání. Pokud se bakterie dostává do intestinálního traktu člověka, vyvolává infekce provázené průjmy. Extraintestiální formy onemocnění jsou vyvolávány kmeny , jež mají polysacharidový kapsulární K antigen, příp P fimbrie, jimiž adherují na povrch sliznic. Pokud se bakterie E. coli dostane do zažívacího traktu, mluví se o ní jako o enteropatogenním kmenu E. coli. Ty se mohou dále dělit:

EPEC E. coli vyvolává vodnaté průjmy především u novorozenců. Může docházet k vysokému stupni dehydratace a následné smrti. Toto onemocnění je stále problémem v rozvojových zemích. Frekvenci infekce způsobené EPEC E. coli u dospělých jedinců je složité stanovit, jelikož u pacientů starších tři roky se po příčině nezávažného průjmu nepátrá.

ETEC E. coli též vyvolává průjmové stavy, jak u dětí, tak dospělých. Tento kmen se vyskytuje v teplých oblastech (Egypt, Bangladéš), do střední Evropy se může dostat s cestovateli. ETEC se vyznačuje tvorbou dvou typů enterotoxinů-termolabilního (TL) a termostabilního (TS). Informace pro tvorbu těchto toxinů je uložena na bakteriálních plasmidech.

TL enterotoxin se skládá z polypeptidové podjednotky A o molekulární hmotnosti 25 kDa a pěti podjednotek B o molekulární hmotnosti 11,5 kDa. Podjednotka B se váže na epitelové buňky a napomáhá translokaci podjednotky A do buňky. Ta katalyzuje aktivaci cAMP. Enzymatickou kaskádou dochází ke zvýšené sekreci sodíku z buňky, a tím i úniků chloridů a následně i vody. Následkem jsou vodnaté průjmy. ST enterotoxin je slabě imunogenní. Aktivuje guanylátcyklázu, a tím se zvyšuje koncentrace cGMP. Další mechanismus není přesně znám. Je možné, že určitou úlohu hraje vápník[5].

EIEC E. coli pronikají do buněk tlustého střeva, kde se množí. Toto onemocnění připomíná průběh bacilární dysenterie.

O epidemiologii EIEC není mnoho známo. Neexistuje její lidský ani zvířecí rezervoár. V oblastech s nedostatečnou hygienou způsobuje EIEC až 5% všech průjmů. Nejčastější sérologickou skupinou je O124.

EHEC E. coli, stejně jako EPEC, je schopen adheze na stěny endotelu. Na rozdíl od EPEC E. coli se však EHEC váže na endotelie tlustého střeva a produkuje zde toxin, tzv. shigella toxin, či jinak zvaný verotoxin. Verotoxin je zodpovědný za poškození sliznice tlustého střeva, což vede ke krvavým průjmům. Onemocnění, jež tento kmen způsobuje se nazývá hemoragická kolitida. U některých pacientů může dojít k poškození ledvin a onemocnění přechází do hemolyticko-uremického syndromu (HUS), jež bývá smrtelný. Zdrojem infekce je infikované hovězí maso. Identifikace EHEC E. coli se opírá o unikátní neschopnost utilizovat sorbitol[6]. Jedním ze zástupců kmene EHEC je sérotyp E. coli O157:H7.

Poprvé byl izolován v roce 1917 na východní frontě profesorem Alfrédem Nissle. Už on byl toho názoru, že přítomnost tohoto sérotypu ve střevní mikroflóře výrazně snižuje riziko vzniku ulcerózní kolitidy. V nedávné době byl tento objev znovu experimentálně potvrzován, přičemž se ukázalo, že ostatní sérotypy tuto schopnost nemají a dokonce jejich přítomnost ve střeve může snižovat účinnost E. coli nissle. V současnosti se mikrobiologové snaží vyvinout léčbu ulcerózní kolitidy pomocí osazení střeva pacienta E. coli nissle.

Sérotyp E. coli O157: H7 je z hlediska veřejného zdraví nejdůležitějším zástupce E. coli EHEC, jelikož způsobuje HUS. Reservoirem tohoto patogena je především dobytek a přežvýkavci. Na člověka se přenáší kontaminovanou potravou (tepelně neupravené maso a mléko), ale i při fekálním znečištění vody a křížovou kontaminací při přípravě pokrmů. Infekční dávka je velice nízká (jednotky bakterií na gram potravy). Poprvé byl tento serotyp izolován r. 1982[7].

Tento sérotyp byl poprvé izolován r. 1922 na univerzitě ve Stanfordu (USA) z lidské stolice. E. coli K-12 se nejprobádanějším zástupcem E. coli vůbec. Důvodem je jednak přítomnost lysogenního bakteriofága lambda v bakterii, jednak široká vybavenost E. coli K-12 množstvím plasmidů, což dává široké možnosti pro využití v genovém inženýrství.

Sérotyp E. coli K-12 byl použit např. při výzkumu metabolismu dusíku u bakterií, biosyntéze L-tryptofanu z indolu a L-serinu a také při studiích konjugace bakteriích[8].

Bakteriální infekce jsou léčeny antibiotiky (beta-laktamová antibiotika, fluorochinolony a aminoglykosidy). Jelikož E. coli má krátkou generační dobu, může se u ní stejně jako u ostatních bakterií velice rychle vyvinout rezistence k používanému antibiotiku.

Mechanismus účinku beta-laktamových antibiotik (penicilin, ampicilin, cefalosporiny) je založen na skutečnosti, že beta-laktamový kruh antibiotika naruší syntézu buněčné stěny bakterie, a ta, jelikož není chráněná, zahyne.

E. coli může produkovat enzym tzv. beta-laktamázu, jež hydrolyzuje beta-laktamový kruh antibiotika , a tím se stává imunní k působení tohoto antibiotika. Geny pro tuto rezistenci bývají uloženy na plasmidu, a proto je genetická informace velice snadno přístupná k předávání jiným bakteriím (i mezidruhově). Nevýhodou informace uložené na plasmidu, je skutečnost, že nemusí při dělení buňky dojít k jejímu předání oběma dceřiným buňkám. Rezistentní by byla pouze jedna z nově vzniklých buněk, druhá by rezistenci nenesla.

Dnes je známo, že v České republice je E. coli cca ze 60% případů rezistentní k podávání aminopenicilinů a z 15% k cefalosporinům[9].

Fluorochinolony jsou antibiotika, jež inhibují replikaci bakteriální DNA. Pokud si bakterie na ně vyvine rezistenci, může se jednat o dva různé mechanismy. Nejčastějším je tzv. efluxu – tj. po tom, co se antibiotikum dostane do bakteriální buňky, je pomocí membránových pump vyčerpáno mimo buňku.

Druhým způsobem, jak se bakterie brání působení fluorochinolonů je pozměnění (methylace, adenylace) jejich cílových struktur, tedy enzymů, jež jsou zodpovědné za replikaci bakteriální DNA. Tyto enzymy se nazývají DNA gyráza a topoisomeráza IV. V České republice se rezistence kmenů E. coli k fluorochinolonům pohybuje okolo 25% případů, což je zhruba evropský průměr.[9].

Aminoglykosidy jsou antibiotika, která blokují proces translace tj. přepis genetické informace z řeči nukleotidů do řeči aminokyselin. Enzymy, kde translace probíhá se nazývají ribozomy. Rezistence k těmto antibiotikům spočívá v modifikaci ribozomů (methylace, adenylace) tak, že se stanou pro aminoglykosidová antibiotika biologicky inertní.

V České republice se výskyt E. coli rezistentní k aminoglykosidům pohybuje okolo 10% případů, což je v rámci Evropy stále průměrné číslo[9].

Bakterie E. coli se vyskytuje jako součást přirozené mikroflóry teplokrevných živočichů v tlustém střevě a dolní části tenkého střeva. Člověk je touto bakterií kolonizován už od narození (kontaminace z potravy, přenos z již kolonizovaného jedince, nejčastěji matky). E. coli patří k nejlépe prostudovaným známým bakteriím, což je důvodem jejího využití v biotechnologiích a genovém inženýrství. Mezi její klady jakožto zástupce prokaryot patří rychlý růst a levná kultivační media, naopak nevýhodou použití E. coli může být její neschopnost provádět posttranslační modifikace, např. glykosylace. V takovýchto případech je v průmyslu využívána kvasinka Saccharomyces cerevisiae[3].

E. coli je nejběžněji používanou bakterií v metodách molekulární biologie. Její kultivace je úspěšná v médiích bohatých (kromě zdroje uhlíku, dusíku a dalších esenciálních látek tato média obsahují i aminokyseliny a vitaminy) i minimálních (obsahují pouze glukosu jako zdroj uhlíku a energie a soli jako zdroj síry, fosforu apod). Pro klonování se používají speciálně upravené kmeny E. coli, které jsou zbavené schopnosti syntézy restrikčních endonukleáz. Pro účely molekulární genetiky byla připravena řada mutantů E. coli:

Diabetes mellitus I.stupně je onemocnění, kdy slinivka břišní není schopna produkovat insulin. Léčba je substituční, kdy se pacientovi exogenně podává insulin. Dříve byl získáván z jatečních prasat. Docházelo však k alergickým reakcím na takto získaný insulin. Důvodem byla různá lokace glykosylace řetězců insulinu u prasat a u člověka. R. 1982 byl na trh uveden insulin získaný rekombinantně pomocí geneticky modifikované bakterie E. coli pod záštitou firmy Eli Lilly. Insulin se dále získává rekombinantními metodami i pomocí eukaryotních organismů, např. Saccharomyces cerevisiae (pod komerčním názvem Novokin od firmy NovoNordisk)[11].

Roku 1983 byla objevena schopnost bakterie E. coli syntetizovat textilní barvivo indigo. Jeho produkce byla však pro průmyslové účely malá a náklady vysoké (jako výchozí substrát byl používán indol, příp. aminokyselina L-tryptofan), proto byla pomocí rekombinace získána E. coli, jež by mohla jako výchozí substrát používat glukosu. Významným kladem této biotechnologické výroby s využitím modifikované E. coli oproti syntetické výrobě je ekologická nezávadnost, jelikož při syntetické výrobě mohou vznikat toxické meziprodukty[12].

Mezi další produkty rekombinantní E. coli patří např. příprava lidského růstového hormonu, interferonu alfa, interferonu gama, interleukinu-2 či produkce aminokyselin (L-valin, L-threonin). Pod záštitou firmy Eli Lilly se na trh s léčivy dostaly rekombinantní hormony jako jsou parathormon a kalcitonin, jež chrání před osteoporosou). Od r. 1999 je na trhu v USA vakcína proti lymské borelioze s názvem Lymerix. Opět se jedná o rekombinantní protein připravený z E. coli. Tato vakcína je účinná pouze na bakterii Borrelia burgdorferi, jež je majoritním původcem lymské boreloisy v USA (v Evropě je to nejčastěji Borrelia garinii)[13].

Escherichia coli (původním názvem Bacterium coli) je gramnegativní fakultativně anaerobní spory netvořící tyčinkovitá bakterie pohybující se pomocí bičíků. Spadá pod čeleď Enterobacteriaceae, jež také zahrnuje mnoho patogenních rodů mikroorganismů. E. coli patří ke střevní mikrofloře teplokrevných živočichů, včetně člověka. Z tohoto důvodu je její přítomnost v pitné vodě indikátorem fekálního znečištění. Člověku je jako součást přirozené mikroflory prospěšná, jelikož produkuje řadu látek, které brání rozšíření patogenních bakterií (koliciny) a podílí se i na tvorbě některých vitamínů (např. vitamín K). Byla objevena německo-rakouským pediatrem a bakteriologem Theodorem Escherichem v roce 1885.

E. coli patří k nejlépe prostudovaným mikroorganismům, jelikož je modelovým organismem pro genové a klinické studie. Joshua Lederberg jako první r. 1947 pozoroval a popsal na bakterii E. coli výměnu genetického materiálu tzv. konjugaci.

Escherichia coli (abgekürzt E. coli) – auch Kolibakterium genannt – ist ein gramnegatives, säurebildendes und peritrich begeißeltes Bakterium, das normalerweise im menschlichen und tierischen Darm vorkommt. Unter anderem auf Grund dessen gilt dieses Bakterium auch als Fäkalindikator.[1] E. coli und andere fakultativ anaerobe Organismen machen etwa 1 ‰ der Darmflora aus.[2]

Innerhalb der Familie der Enterobakterien (altgriechisch ἕντερον, lateinisch enteron „Darm“) gehört E. coli zur bedeutenden Gattung Escherichia und ist deren Typspezies.[3] Benannt wurde es nach dem deutschen Kinderarzt Theodor Escherich, der es erstmals beschrieb. Coli ist der lateinische Genitiv von colon (zu dt. Kolon), einem Teil des Dickdarms.[4]

Die meisten Angehörigen dieser Spezies sind nicht krankheitsauslösend, jedoch gibt es auch zahlreiche verschiedene pathogene Stämme.[5] Es zählt zu den häufigsten Verursachern von menschlichen Infektionskrankheiten.[1] Die Basensequenz des Genoms einiger Stämme ist vollständig aufgeklärt. Als Modellorganismus zählt es zu den am besten untersuchten Prokaryoten[6] und nimmt in der Molekularbiologie eine wichtige Rolle als Wirtsorganismus ein. Der Nobelpreis für Physiologie oder Medizin wurde an zahlreiche Forscher, die sich mit der Biologie von E. coli beschäftigt haben, vergeben.[7]

E. coli hat die Form gerader, zylindrischer Stäbchen mit runden Enden. Der Durchmesser beträgt 1,1–1,5 µm und die Länge 2,0–6,0 µm. Sie kommen paarweise oder einzeln vor. In der Gram-Färbung verhalten sie sich negativ (gramnegativ).[3] Es bildet keine Bakteriensporen.[6] Die Zellen bestehen überwiegend (70–85 %) aus Wasser, wobei die Trockenmasse zu 96 % aus Polymeren besteht, unter denen die Proteine dominieren. Es sind 4288 unterschiedliche Proteine annotiert. Im Cytoplasma als auch in der Zellhülle (bestehend aus Zellmembran, Periplasma, äußere Membran) erfüllen sie strukturelle, enzymatische und regulatorische Funktionen. Das Genom umfasst etwa 4600 Kilobasenpaare und kommt als kovalent in sich geschlossenes Bakterienchromosom vor.[8]

Viele Stämme besitzen Fimbrien (Pili). Eine Zelle des Stammes K-12 enthält typischerweise etwa 100–500 Typ 1 Fimbrien mit einer Länge von 0,2–2,0 µm und einem Durchmesser von ca. 7 nm. Es gibt mehr als 30 verschiedene Arten von Fimbrien, die in zwei nach ihren adhesiven Eigenschaften an rote Blutkörperchen eingeteilt werden: MS (Mannose-sensitive), die in Anwesenheit von Mannose rote Blutkörperchen nicht verklumpen können (Hämagglutination) und MR (Mannose-resistente), denen die Präsenz des Zuckers nichts ausmacht. Typ 1 Fimbrien, die zu den MS-Fimbrien gehören, kommen sowohl in symbiotischen als auch in pathogenen Stämmen vor und werden daher nicht zur Differenzierung herangezogen. MR-Fimbrien sind serologisch divers und fungieren häufig als Virulenzfaktoren. Ihr Anhaften ist sowohl spezies- als auch organspezifisch.[3] Zusätzlich bildet E. coli auch einen Sexpilus aus (auch F-Pilus, F für Fertilität) mit dem Zell-Zell-Kontakte zum Austausch von genetischer Information (Konjugation) möglich sind. Zudem dient der F-Pilus auch einigen Bakteriophagen als Rezeptor nach deren Bindung die Virus-DNA eingeschleust wird (Transduktion).[9]

Zellen von E. coli können sich durch peritriche Begeißelung aktiv bewegen (sie sind motil) oder sie sind – seltener – zur aktiven Bewegung unfähig. Motile E. coli bewegen sich mit ihrem proteinösen Flagellum fort, wobei sie wiederholt ihre Richtung ändern: Ein Bakterium bewegt sich in eine Richtung fort, indem sich die Flagellen bündeln und zusammenarbeiten. Die Fortbewegung wird zeitweise kurz durch Taumeln unterbrochen, indem sich das Flagellenbündel auflöst und die einzelnen Flagellen sich in verschiedene Richtungen wenden. Danach reformiert sich das Flagellenbündel und beschleunigt das Bakterium in eine neue Richtung. Die Stabilität des Bündels wird durch Chemorezeptoren verstärkt. Bietet man den Bakterien einen Nährstoff an, so wird die Stabilität des Flagellenbündels weiter verstärkt, und die Bakterien akkumulieren.

E. coli ist chemotaktisch: Schwimmen die Individuen in einem Konzentrationsgefälle eines Lockstoffs in Richtung ansteigender Konzentration, so ändern sie weniger häufig ihre Richtung. Schwimmen sie ein Konzentrationsgefälle herunter, ist ihr Bewegungsmuster nicht von dem in einer isotropen Lösung zu unterscheiden, und sie ändern häufiger die Richtung.[10] Neben positiver Chemotaxis kann E. coli sich auch aktiv von Schadstoffen entfernen (negative Chemotaxis), wobei niedrige Konzentrationen an Schadstoffen keine Lockstoffe darstellen und hohe Nährstoffkonzentration nicht abstoßend wirken. Es gibt Mutanten, die gewisse Schadstoffe nicht erkennen, und nicht-chemotaktische Mutanten, die auch keine Lockmittel erkennen können. Der Prozess benötigt L-Methionin.[11]

Die Signaltransduktion für akkurate chemotaktische Reaktionen hat sich im Laufe der Evolution auf optimale Arbeitsleistung bei minimaler Proteinexpression entwickelt. Aufgrund des hohen Selektionsdrucks ist die Chemotaxis bei E. coli sehr sensitiv, besitzt ein schnelles Ansprechverhalten und ist perfekt angepasst. Zudem scheint die Anordnung innerhalb des bakteriellen chemosensorischen Systems hochkonserviert.[12]

Zum Stoffaustausch besitzt E. coli Transportproteine in der Zellmembran. Unter den Porinen dominieren Outer-membrane-Proteine OmpF und OmpC, welche zwar nicht substratspezifisch sind, jedoch kationische und neutrale Ionen bevorzugen und hydrophobe Verbindungen nicht akzeptieren. Die Kopienzahl hängt von der Osmolarität der Umgebung ab und dient der Anpassung an den Lebensraum. Unter den Bedingungen im Dickdarm (Hyperosmolarität, höhere Temperatur) überwiegen OmpC-Kanäle. Verlässt das Bakterium seinen Wirt und findet sich in einem weniger bevorzugten Lebensraum, z. B. einem Gewässer (niedrigere Osmolarität und Temperatur) so wird die OmpF-Synthese gefördert. Für Substrate, die durch die unspezifischen Porine gar nicht oder unzureichend transportiert werden, gibt es substratspezifische Porine. Bei Phosphatmangel exprimiert E. coli das Protein PhoE. Zusammen mit Maltodextrinen entstehen daraus Maltoporine, die auch als Rezeptor für die Lambda-Phage fungieren und daher auch LamB genannt werden. Stämme, die Saccharose verwerten können, nehmen diese über das Kanalprotein ScrY auf. Langkettige Fettsäuren werden mit FadL in die Zelle transportiert.[13]

E. coli ist heterotroph, fakultativ anaerob und besitzt die Fähigkeit, Energie sowohl durch die Atmungskette als auch durch „Gemischte Säuregärung“ zu gewinnen. Die Gärungsbilanz bei E. coli sieht folgendermaßen aus:[14]

Glucose wird von E. coli unter Säurebildung vergoren, was mit Methylrot als pH-Indikator nachgewiesen werden kann. Neben Säure bildet E. coli aus Glucose auch Gas. Der Indol-Test auf Tryptophanase ist positiv. Die Voges-Proskauer-Reaktion zum Nachweis der Acetoin-Bildung fällt negativ aus. Auf Simmons Citrat-Agar ist keine Verfärbung sichtbar, da E. coli Citrat nicht als alleinige Energiequelle nutzen kann. Zudem kann es Malonat nicht verwerten. Acetat und Tartrat können verstoffwechselt werden (Test mit Methylrot nach Jordan). Nitrat kann zu Nitrit reduziert werden. Auf Triple Sugar Iron-Agar wird kein Schwefelwasserstoff gebildet. E. coli kann keinen Harnstoff und keine Gelatine hydrolysieren, einige Stämme jedoch Esculin. Lysin wird von vielen Stämmen decarboxyliert, Ornithin nur von wenigen. Im Kaliumcyanid-Wachstumstest wächst E. coli nicht. Es besitzt keine Phenylalanindeaminase, keine Lipase und keine DNase im engeren Sinne. Der Oxidase-Test mit Kovacs-Reagenz ist stets negativ. Des Weiteren kann von den meisten Stämmen L-Arabinose, Lactose, Maltose, D-Mannitol, D-Mannose, Mucinsäure, D-Sorbitol, Trehalose und D-Xylose fermentativ genutzt werden.[3]

Die Serotypisierung ist eine nützliche Möglichkeit E. coli anhand der zahlreichen Unterschiede in der Antigenstruktur auf der Bakterienoberfläche einzuteilen.[3]

Man unterscheidet vier Gruppen von Serotypen:

Selten zur Diagnostik eingesetzt werden:

E. coli kommt als universeller und kommensaler Begleiter im unteren Darmtrakt warmblütiger Tiere (inklusive des Menschen) vor. Im Stuhl befinden sich etwa 108–109 koloniebildende Einheiten pro g.[6] Es kann auch in anderen Habitaten überleben. Bei Neugeborenen spielt es als Erstbesiedler eine wichtige Rolle. Obwohl es selbst nur in geringer Zahl vorhanden ist, dient es der Ansiedlung obligater Anaerobier, die physiologische Bedeutung bei der Verdauung besitzen.[18] Trotz des geringen Anteils im Darm nimmt E. coli eine beherrschende Stellung im Darm ein, den es bei Menschen innerhalb von 40 Stunden nach der Geburt über Lebensmittel, Wasser oder andere Individuen kolonisiert. Die Fähigkeit zum Anhaften an den Mucus erlaubt E. coli, lange Zeit im Darm zu verweilen. Obwohl sehr viel über den Organismus bekannt ist, weiß man über seine Ökologie im Darm relativ wenig.[19]

Sporadische durch Trinkwasser übertragene Ausbrüche von enterotoxischen Stämmen (ETEC) sind bekannt. Zudem werden ETEC durch Konsum von Weichkäse und rohem Gemüse übertragen. Ausbrüche von enteropathogenen Stämmen (EPEC) werden häufig mit kontaminiertem Trinkwasser und einigen Fleischprodukten in Verbindung gebracht. Infektionen mit enterohämorrhagischen E. coli (EHEC) stammen häufig von Lebensmitteln oder geschehen mittels Wasser. Häufig infizierte Lebensmittel sind nicht durchgegartes Rinderhack, Rohmilch, kalte Sandwiches, Wasser, nicht-pasteurisierter Apfelsaft, Sprossen und rohes Gemüse.[20] Zudem standen Epidemien im Zusammenhang mit Hamburgern, Roastbeef, Kohlrouladen und Rohwurst (Teewurst).[21]

In 1–2 % des Rinderkots kann der für Rinder ungefährliche magensäureresistente Stamm Escherichia coli O157:H7 (EHEC) nachgewiesen werden, welcher bei der Schlachtung auch das Fleisch kontaminieren und bei Menschen schwere Lebensmittelvergiftungen auslösen kann. Der Grund hierfür ist, dass häufig stärkehaltiges Getreide gefüttert wird, das im Pansen unvollständig abgebaut und zu Säure fermentiert wird, so dass sich acidophile Bakterien dort anreichern. Die Fütterung von Heu oder Gras reduziert die Anzahl humanpathogener Stämme.[22]

Da eine komplette EHEC-Sanierung der Tierbestände nicht möglich ist, muss die Prophylaxe bei der Schlachthygiene ansetzen. Rindfleischprodukte sollten mindestens 10 Minuten bei mindestens 70 °C durchgegart werden. Aufgrund der hohen Umweltresistenz der Erreger sollten Lebensmittelhersteller Belastungstests und HACCP-Analysen durchführen. Risikogruppen (Kinder unter 6 Jahren und immunsupprimierte Personen) sollten rohe Produkte nicht verzehren.[21]

Nach der EU-Badegewässerverordnung von 2008 gelten für E.coli folgende Grenzwerte:[23]

Bei Trinkwasser gilt hingegen ein restriktiver Grenzwert von 0 CFU / 100 ml.[24]

Sandstrände können besonders von E.coli betroffen sein, da der Abbau der Abwasserbakterien im Sand länger dauert als im Meerwasser.[25]

Der Stamm Escherichia coli Alfred Nissle 1917 (Handelsname Mutaflor) zählt zu den am häufigsten untersuchten Probiotika. Er wurde während des Balkankriegs vom Stuhl eines Soldaten isoliert, der im Gegensatz zu seinen Kameraden nicht an Durchfall litt. Der Stamm ist mittlerweile sequenziert und besitzt sechs verschiedene Systeme, um Eisen aufzunehmen, wodurch er Konkurrenten aus dem Feld schlägt. Er besitzt Adhesine für eine effektive Kolonisierung und blockiert das Anhaften und Eindringen von pathogenen Bakterien an die Epithelzellen des Darms. Zudem besitzt es einen entzündungshemmenden Effekt auf die T-Zellen-Proliferation. Des Weiteren wird die Produktion von menschlichem β-Defensin 2 angeregt, das als Breitspektrumantibiotikum sowohl grampositive als -negative Bakterien, Pilze und Viren abtötet.[26]

Die meisten Stämme von E. coli sind nicht pathogen und damit harmlos. Einige Serotypen spielen jedoch eine wichtige Rolle bei Erkrankungen innerhalb und außerhalb des Darms.[27] In Wirten mit Immunschwäche ist E. coli ein opportunistischer Erreger, das heißt, erst durch die Schwächung des Wirts kann er wirksam werden.[3] Uropathogene E. coli (UPEC) sind für unkomplizierte Harnwegsinfektionen verantwortlich.[28][29] Neonatale Meningitis auslösende E. coli (NMEC) können die Blut-Hirn-Schranke passieren und bei Neugeborenen eine Hirnhautentzündung auslösen. NMEC und UPEC führen im Blutstrom zur Sepsis.[30]

Es wird vermutet, dass E. coli mit chronisch-entzündlichen Darmerkrankungen wie Morbus Crohn und Colitis ulcerosa assoziiert ist, da neben genetischer Prädisposition und Umweltfaktoren an der Krankheitsentstehung unter anderem auch eine fehlregulierte Immunantwort der Schleimhaut gegen kommensale Bakterien beteiligt sein könnte.[31] Die Schleimhaut der Patienten ist abnormal mit adhärent-invasiven E. coli (AIEC) kolonisiert, welche an den Epithelzellen anhaften und in sie eindringen.[32]

Die darmpathogenen E. coli werden in fünf verschiedene Pathogruppen unterteilt. Weltweit verursachen sie jährlich 160 Mio. Durchfallerkrankungen und 1 Mio. Todesfälle. In den meisten Fällen sind Kinder unter 5 Jahren in den Entwicklungsländern betroffen.[33]

Enteropathogene E. coli (kurz EPEC) sorgen bei Kleinkindern für schwere Durchfälle, die in industrialisierten Gesellschaften selten, in unterentwickelten Ländern jedoch häufig für kindliche Todesfälle verantwortlich sind. Mithilfe des EPEC Adhäsionsfaktor (EAF) heften sich die EPEC an die Epithelzellen des Dünndarms und injizieren dann Toxine in die Enterozyten mit Hilfe eines Typ-III-Sekretionssystems.[1] Es existieren auch sogenannte atypische EPEC. Sie zeigen die bei STEC gängigen Serotypen sowie Virulenz- und Pathogenitätsfaktoren wie beispielsweise das eae-Gen. Den Stx-Prophagen und die damit zugehörigen für STEC charakteristischen stx-Gene haben sie jedoch wahrscheinlich verloren.[34]

Enterotoxische E. coli (kurz ETEC) sind häufiger Erreger der Reisediarrhoe („Montezumas Rache“). Grund für diese Erkrankung ist ein hitzelabiles Enterotoxin vom A/B Typ (LT I und LT II), sowie ein hitzestabiles Enterotoxin (ST). Dieses 73 kDa große Protein besitzt zwei Domänen, von denen sich eine an ein G-Gangliosid der Zielzelle bindet (Bindende Domäne). Die andere Domäne ist die Aktive Komponente, die ähnlich dem Choleratoxin (etwa 80 % Genhomologie) die Adenylatcyclase aktiviert. Das etwa 15–20 Aminosäuren lange ST aktiviert die Guanylatcyclase. Die Aktivierung der Adenylatcyclase und der Guanylatcyclase endet in einer sekretorischen Diarrhoe, bei der viel Wasser und Elektrolyte verloren gehen. Die genetische Information erhält das Bakterium von einem lysogenen Phagen durch Transduktion.[33]

Enteroinvasive E. coli (kurz EIEC) penetrieren die Epithelzellen des Kolons und vermehren sich dort. Innerhalb der Zelle kommt es zur Aktinschweifbildung, womit sie wie Listerien und Shigellen in benachbarte Epithelzellen eindringen. Es kommt zu Entzündungen und Geschwürbildung unter Absonderung von Blut, Schleim und weißen Blutkörperchen (Granulozyten). Zudem können EIEC Enterotoxine abgeben, die zu Elektrolyt- und Wasserverlust führen. Das Krankheitsbild ähnelt einer Bakterienruhr mit Fieber und blutig-schleimigen Durchfällen, wobei häufig eine abgeschwächte Symptomatik mit wässriger Diarrhoe einhergeht.[33]

Enterohämorrhagische E. coli (kurz EHEC) sind Shigatoxin produzierende E. coli (STEC) mit zusätzlichen Pathogenitätsfaktoren. Das Shigatoxin wirkt enterotoxisch und zytotoxisch und zeigt Ähnlichkeiten mit dem von Shigellen gebildeten Toxin. Analog werden VTEC (Verotoxin produzierende E. coli) benannt. Durch EHEC verursachte Darmerkrankungen wurden vornehmlich unter dem Namen enterohämorrhagische Colitis bekannt. EHEC-Infektionen zählen zu den häufigsten Ursachen für Lebensmittelvergiftungen. Der Erreger ist hoch infektiös: 10 – 100 Individuen sind für eine Erkrankung ausreichend. Die niedrige Infektionsdosis begünstigt eine Übertragung von Mensch zu Mensch. Eine Infektion kann jedoch auch durch Tierkontakt (Zoonose) oder durch Verschlucken von Badewasser erfolgen. Typische Krankheitsbilder sind die thrombotisch-thrombozytopenische Purpura (TTP) und ein hämolytisch-urämisches Syndrom (HUS). Gefürchtet ist vor allem HUS aufgrund der Möglichkeit, an einem terminalen Nierenschaden zu sterben. Hierbei sind alle Altersgruppen betroffen, jedoch vor allem Kinder unter 6 Jahren. Das Nierenversagen verläuft in 10 – 30 % der Fälle mit dem Tod des Patienten innerhalb eines Jahres nach Beginn der Erkrankung.[21]

Enteroaggregative E. coli (EAggEC oder EAEC abgekürzt) besitzen die Fähigkeit zur Autoaggregation. Sie heften sich mit spezifischen Fimbrien an das Dünndarmepithel. Charakteristisch ist die erhöhte Schleimproduktion der Mukosazellen, die eine Ausscheidung verzögert. Es kommt zu einer Diarrhoe vom sekretorischen Typ aufgrund von Enterotoxinen (EAST). Durch EAEC werden sowohl akute als auch chronisch rezidivierende Durchfallerkrankungen, die sich über Wochen hinziehen können, verursacht. Neben wässrig schleimigem Durchfall kann es auch zu Fieber und Erbrechen oder blutigem Stuhl kommen. Bei Immunsupprimierten (z. B. HIV-Patienten) ist EAEC der häufigste Erreger einer bakteriellen Enteritis.[33]

E. coli ist für eine Vielzahl von Infektionskrankheiten bei Tieren verantwortlich. Spezifische veterinärmedizinische Krankheitsbilder sind:

Beim Hausschwein lösen extraintestinal pathogene (ExPEC) Stämme eine hämorrhagische Septikämie aus, die als Differentialdiagnose zur klassischen Schweinepest angesehen wird.[35]

Coliforme Bakterien werden als Indikator für die sanitäre Gewässergüte und die Hygiene bei der Lebensmittelverarbeitung verwendet. Fäkalcoliforme Keime gelten insbesondere bei Schalentieren als der Standardindikator für Verunreinigung. E. coli zeigt fäkale Verunreinigung sowie unhygienische Verarbeitungen an. Klassischerweise basieren die biochemischen Methoden zum Nachweis von E. coli, Gesamtcoliformen oder Fäkalcoliformen auf der Verwertung von Lactose. Eine Auszählung ist mittels MPN-Verfahren möglich. Gebräuchlich ist eine Brillantgrün-Galle-Lactose-Bouillon in denen Gasbildung beobachtet wird. Es gibt jedoch auch spezielle Nährböden wie Eosin-Methylen-Blau, VRB-Agar (Kristallviolett-Neutralrot-Galle-Agar), MacConkey-Agar[20] und Endo-Agar, die Lactoseverwertung anzeigen. Zur Differenzierung von anderen Enterobakterien kann der IMViC-Test durchgeführt werden.[36]

Pathogene E. coli werden ebenfalls zunächst angereichert. Das hitzelabile Enterotoxin (LT) der ETEC kann durch einen Y-1-Nebennieren-Zell-Assay, Latexagglutinations-Assay und ELISA nachgewiesen werden. Der Nachweis für das hitzestabile Toxin (ST) der ETEC kann ebenfalls mittels ELISA oder Jungmaus-Assay erfolgen. Die Gene für LT und ST sind bekannt und können mittels PCR oder mittels Gensonde nachgewiesen werden. In Verbindung mit Ausplattierung auf Agarkulturmedien können so ETEC-positive Kolonien gezählt werden. EIEC sind nicht-motil und anaerogen, da sie kein Lysin decarboxylieren und keine Lactose fermentieren. Der invasive Phänotyp von EIEC, der durch ein hochmolekulares Plasmid codiert wird, kann mittels HeLa-Zellen oder Hep-2-Gewebezellkulturen nachgewiesen werden. Alternativ können PCR- und Sondenmethoden für die Invasionsgene eingesetzt werden. Das Protein Intimin der EPEC wird durch ein eae-Gen codiert auf das mit PCR getestet werden kann. Des Weiteren wird der EPEC-adhärent-Faktor (EAF) über ein Plasmid codiert. Das Protein lässt sich mit Hep-2-Zellen nachweisen. EHEC kann über die Shiga-Toxine (Stx) nachgewiesen werden. Insbesondere Stx1 und Stx2 werden mit menschlichen Erkrankungen in Zusammenhang gebracht, wobei zahlreiche Varianten von Stx2 existieren. Die Produktion von Stx1 und Stx2 kann mit Zytotoxizitätstests auf Vero-Zellen oder Hela-Gewebekulturen sowie durch ELISA und Latexaggulationstests erfolgen. Zudem gibt es PCR-Assays für Stx1, Stx2 oder andere charakteristische Marker. EHEC zeichnen sich zudem durch keine oder langsame Fermentation von Sorbitol aus.[20] Eine weitere biochemische Differenzierung ist der LST-MUG-Assay, welcher auf der enzymatischen Aktivität von β-Glucuronidase (GUD) basiert. GUD setzt das Substrat 4-Methylumbelliferyl-β-D-glucuronid (MUG) in 4-Methylumbelliferon um, welches bei 365 nm (UV-Licht) eine blaue Fluoreszenz zeigt. GUD wird von>95 % der E. coli-Stämme produziert (inklusive denen, die kein Gas produzieren), jedoch nicht von EHEC des Serotyps O157:H7, weshalb es hier zur Differenzierung verwendet werden kann.[36]

Die Therapie bei fakultativ pathogenen Stämmen sollte immer gezielt nach Antibiogramm erfolgen. E. coli-Arten (insbesondere ESBL-Stämme im Gegensatz zum Wildtyp, der gut sensibel gegen Cephalosporine ist)[37] besitzen Antibiotikaresistenzen durch die Bildung zahlreicher β-Lactamasen, die in der Lage sind, β-Lactam-Antibiotika zu spalten (ESBL-Stämme, die resistent gegen alle β-Lactama-Antibiotika außer Carbapenem resistent sind, sind zudem häufig multiresistent – auch gegenüber Chinolonen[38]).

Mittel der Wahl sind Aminopenicilline, Ureidopenicilline, Cephalosporine (idealerweise ab der 2. Generation), Carbapeneme, Chinolon-Antibiotika und Cotrimoxazol. Aminoglycoside werden in Ausnahmesituationen kombiniert.

Bei Befall der Harnwege eignen sich insbesondere Cotrimoxazol (bei Sensitivität) und Cefuroxim, alternativ auch Levofloxacin, Ciprofloxacin und Fosfomycin; bei Bakteriämie und Sepsis Cefotaxim und Ceftriaxon, und alternativ Levofloxacin und Ciprofloxacin. Bei einer Meningitis durch E. coli eignen sich Ceftriaxon, Cefotaxim und alternativ Meropenem. Infektionen mit ESBL-positiven Stämmen werden mit Ertapenem, Imipenem, Meropenem, Levofloxacin oder (wenn sensibel) mit Ciprofloxacin therapiert.[38]

Bei obligat pathogenen E.-coli-Stämmen sind die Gastroenteritidien selbstlimitierend. Der starke Flüssigkeitsverlust muss jedoch insbesondere bei Säuglingen und Kleinkindern behandelt werden. Für den Wasser- und Salzverlust bieten sich orale Rehydratationslösungen an. Die zweimalige Gabe von Antibiotika (z. B. Ciprofloxacin und Cotrimoxazol) innerhalb von 24 h kann Dauer und Schwere der Erkrankung lindern.[39]

Eine rasche Keimzahlreduktion kann nur bei sehr frühem Einsatz erzielt werden. Bei der Therapie von enterohämorrhagischen E. coli mit Antibiotika kann es durch vermehrte Ausschüttung von Verotoxin zu Komplikationen kommen. Insbesondere bei der Gabe von Fluorchinolonen, Cotrimoxazol, Aminoglycosiden und Fosfomycin überwiegen die ungünstigen Wirkungen. Dies gilt nicht in gleichem Maße für Carbapeneme. Auch der Einsatz neuerer Makrolide und gegebenenfalls von Clindamycin sowie Rifampicin und Rifaximin bei gegebener Indikation (z. B. Sanierung von Meningokokken-Trägern) scheint nicht kontraindiziert. Jedoch bleibt der Einsatz dieser Substanzen im Sinne einer EHEC-Virulenzabschwächung durch Reduktion der Verotoxinproduktion kontrovers.[40]

In Deutschland ist der direkte oder indirekte Nachweis von Escherichia coli (enterohämorrhagische Stämme (EHEC) und sonstige darmpathogene Stämme) namentlich meldepflichtig nach des Infektionsschutzgesetzes, soweit der Nachweis auf eine akute Infektion hinweist.

Entdeckt wurde E. coli 1885 von Theodor Escherich, der es damals „Bacterium coli commune“ nannte.[41] 1919 wurde es ihm zu Ehren umbenannt.[42] 1892 wurde von Shardinger vorgeschlagen, E. coli als Indikatororganismus für fäkale Verunreinigung zu verwenden. In der Praxis war es jedoch schwierig, mit rein biochemischen Nachweismethoden E. coli von anderen Enterobakterien abzugrenzen, weshalb die nicht taxonomische Bakteriengruppe coliforme Bakterien definiert wurde.[36] 1997 wurde die DNA-Sequenz aufgeklärt.[8] Hierfür wurden 15 Jahre benötigt.[43]

Serotyp O7:K1 (Stamm IAI39 / ExPEC)

Stamm SMS-3-5 / SECEC

Serotyp O127:H6 (Stamm E2348/69 / EPEC)

Serotyp O6:H1 (Stamm CFT073 / UPEC)

Serotyp O45:K1 (Stamm S88 / ExPEC)

Serotyp O1:K1 / APEC

Stamm UTI89 / UPEC

Serotyp O81 (Stamm ED1a)

Serotyp O6:K15:H31 (Stamm 536 / UPEC)

Serotyp O157:H7 (Stamm TW14359 / EHEC)

Serotyp O157:H7 (Stamm EC4115 / EHEC)

Serotyp O157:H7 (Stamm EDL933 / EHEC)

Serotyp O139:H28 (Stamm E24377A / ETEC)

Stamm 55989 / EAEC

Serotyp O8 (Stamm IAI1)

Stamm SE11

Serotyp O103:H2 (Stamm 12009 / EHEC)

Stamm Crooks

Stamm B / BL21-DE3

Stamm B / BL21

Stamm K12 / MC4100 / BW2952

Stamm K12

Stamm K12 / DH10B

Stamm K12 / DH1

Serotyp O9:H4 (Stamm HS)

Serotyp O17:K52:H18 (Stamm UMN026 / ExPEC)

Das Kerngenom, das sich in allen Stämmen wiederfindet, macht lediglich 6 % der Genfamilien aus. Über 90 % der Gene sind variabel. Die Diversität innerhalb der Spezies und die überlappenden Geninhalte mit verwandten Spezies lassen einen Übergang anstelle einer scharfen Speziesabgrenzung innerhalb der Enterobacteriaceae vermuten.[45] Insbesondere zwischen der Gattung Shigella und enteroinvasiven E. coli gibt es eine enge evolutionäre Verwandtschaft sowohl in der chromosomalen DNA als auch bei dem Virulenzplasmid.[46]

Man unterscheidet anhand von phylogenetischen Analysen vier Hauptgruppen (A, B1, B2, und D), wobei die virulenten extraintestinalen Stämme hauptsächlich zu den Gruppen B2 und D gehören.[47] Innerhalb der Gattung Escherichia ist E. fergusonii die nächste verwandte Art.[48]

Der extraintestinal pathogene (ExPEC) Serotyp O7:K1 (Stamm IAI39) löst beim Hausschwein eine hämorrhagische Septikämie aus. Er hat keine ETEC (enterotoxische) oder EDEC (Ödemkrankheit-verursachende E. coli) Virulenzfaktoren. Stattdessen besitzt er P-Fimbrien und Aerobactin[35] Stamm SMS-3-5 / SECEC wurde in einem küstennahen Industriegebiet, mit Schwermetallen verseuchtem Gebiet isoliert. Es ist gegen zahlreiche Antibiotika in hohen Konzentrationen resistent.[49]

Serotyp O127:H6, Stamm E2348/69 war der erste sequenzierte und am besten untersuchte enteropathogene E. coli (EPEC).[50]

Im Vergleich mit anderen pathogenen Stämmen zeigt CFT073 des Serotyps O6:H1 das Fehlen eines Typ-III-Sekretionssystems und keine phagen- oder plasmidcodierten Toxine. Stattdessen besitzt er fimbriale Adhesine, Autotransporter, Eisen-Sequestierungssysteme und Rekombinasen. Schlussfolgernd kann man sagen, dass extraintestinal pathogene E. coli unabhängig voneinander entstanden sind. Die verschiedenen Pathotypen haben hohe Syntänie, die durch vertikalen Gentransfer entstanden ist und ein gemeinsames Rückgrat bildet, das durch zahlreiche Inseln aufgrund von horizontalem Gentransfer unterbrochen wird.[51]

Der Serotyp O45:K1 (Stamm S88 / ExPEC) wurde 1999 aus der Zerebrospinalflüssigkeit eines spät ausbrechenden Meningitisfalles in Frankreich isoliert. Er gehört zur phylogenetischen Gruppe B2.[52] Der Serotyp O1:K1 löst bei Vögeln Krankheiten aus und wird „avian pathogen Escherichia coli“ (APEC) genannt. Er ist mit drei menschlichen uropathogenen (UPEC) eng verwandt.[53] UTI89 ist ein uropathogener E.-coli-Stamm, der aus einem Patienten mit akuter Blaseninfektion isoliert wurde.[54] Der Stamm ED1a ist hingegen apathogen und wurde aus dem Stuhl eines gesunden Mannes isoliert.[55] Der uropathogene Stamm 536 (O6:K15:H31) stammt ursprünglich von einem Patienten mit akuter Pyelonephritis. Er ist ein Modellorganismus für extrainstestinale E. coli. Das Genom enthält fünf gut charakterisierte Pathogenitätsinseln und eine neu entdeckte sechste, die den Schlüsselvirulenzfaktor darstellt.[56]

Der gefürchtete Lebensmittelvergifter E. coli O157:H7 wurde vollständig sequenziert, um seine Pathogenität zu verstehen. Die Erklärung liefert ein massiver lateraler Gentransfer. Über 1000 neue Gene finden sich in diesem stammspezifischen Cluster. Enthalten sind mögliche Virulenzfaktoren, alternative metabolische Fähigkeiten sowie zahlreiche Prophagen, die für die Lebensmittelüberwachung genutzt werden können.[57] Das Virulenzplasmid pO157 besitzt 100 offene Leserahmen. Ein ungewöhnlich großes Gen hat ein mutmaßliches aktives Zentrum, das mit der Familie des großen clostridialen Toxins (LCT) und Proteinen wie ToxA und B von Clostridium difficile verwandt ist.[58] Der Stamm TW14359 wurde 2006 nach einem Ausbruch von E. coli O157:H7 in den USA aus Spinat isoliert. Es wurden neue Genabschnitte festgestellt, welche die erhöhte Fähigkeit zur Auslösung des hämolytisch-urämischen Syndroms oder alternativ die Anpassung an Pflanzen erklären. Zudem enthält der Stamm Gene für intakte anaerobe Nitritreduktasen.[54]

Der Serotyp O139:H28 (Stamm E24377A / ETEC) ist ein enterotoxisches Isolat. Er besitzt das Kolonisationsfaktorantigen (colonization factor antigen, CFA) Pili, um sich anzuheften. 4 % des Genoms bestehen aus Insertionssequenzen. Vermutlich kann der Stamm Propandiol als einzige Kohlenstoffquelle verwerten.[59] Stamm 55989 / EAEC ist ein enteroaggregativer Stamm, der 2002 in der Zentralafrikanischen Republik aus dem Stuhl eines HIV-positiven Erwachsenen, der an stark wässrigem Durchfall litt, isoliert wurde.[60]

Der Stamm IAI1 vom Serotyp O8 ist ein bei Menschen kommensaler Stamm, der aus den Fäzes eines gesunden Franzosen in den 1980ern isoliert wurde.[61] Bakterien des Stammes SE11 vom Serotyp O152:H28 wurden ebenfalls aus den Fäzes eines gesunden Menschen isoliert. Im Vergleich mit dem Laborstamm K-12 MG1655 besitzt der Stamm zusätzliche Gene für Autotransporter und Fimbrien, um sich an den Darmzellen zu befestigen. Zudem besitzt er mehr Gene, die für den Kohlenhydratstoffwechsel von Bedeutung sind. Alles deutet darauf hin, dass sich dieser Stamm an den menschlichen Darm angepasst hat.[62] Bakterien des Serotyps O103:H2 (Stamm 12009) wurden 2001 in Japan von einem Patienten mit sporadisch auftretendem blutigen Durchfall isoliert. Offenbar sind EHEC-Stämme mit den gleichen Pathotypen von verschiedener Abstammung unabhängig voneinander durch Lambda-Phagen, Inserationelemente und Virulenzplasmide entstanden.[63]

Crooks (ATCC 8739 / DSM 1576) ist ein fäkaler Stamm, der dazu verwendet wird, die Effizienz antimikrobieller Wirkstoffe zu testen. Er besitzt ein Insertionselement innerhalb von ompC und kann daher nur ompF als äußeres Membranporin exprimieren.[64] Der Stamm B dient als Forschungsmodell für Phagensensitivität, Restriktionsmodifikationssysteme und bakterielle Evolution. Ihm fehlen Proteasen. Zudem produziert er wenig Acetat, wenn ihm viel Glucose angeboten wird. Aufgrund einer einfachen Zelloberfläche ist die selektive Permeabilität verbessert. Daher wird er gerne zur rekombinanten Proteinexpression im Labormaßstab und in industriellen Dimensionen eingesetzt.[65] Der Stamm K12 von MC4100 ist sehr häufig eingesetzt. Eine Genomsequenzierung zeigte, dass er während seiner Anpassung an die Laborumgebung zusätzliche Unterschiede entwickelt hat, die nicht künstlich herbeigeführt wurden.[66] Der Stamm K12 wurde 1922 von einem Patienten mit Diphtherie isoliert und 1925 in die Stammsammlung von Stanford überführt. Da er prototroph und in definiertem Medium mit kurzen Generationszeiten einfach zu züchten ist, wurde er schnell zum bestuntersuchten Organismus und seit den 1950ern zum Verstehen zahlreicher fundamentaler biochemischer und molekularer Prozesse herangezogen. Zudem besitzt er die unter E-coli-Wildtypen seltene Fähigkeit zur Rekombination.[67] Der Stamm DH10B ist ein Derivat von K12, das aufgrund der leichten Transformation insbesondere großer Plasmide (nützlich bei der Genomsequenzierung) vielfach eingesetzt wird. Die Sequenz wurde aus „Kontaminationssequenzen“ bei der Genomsequenzierung des Rindes zusammengesetzt.[68]

Der Serotyp O9:H4 (Stamm HS) wurde von einem Laborwissenschaftler des Walter-Reed-Militärkrankenhauses isoliert. Im Humanexperiment zeigte sich, dass der Stamm HS den Gastrointestinaltrakt kolonisiert, aber keine Krankheitsbilder verursacht.[69] Der Stamm UMN026 ist ein extraintestinal pathogener Stamm (ExPEC), der 1999 in den USA von einem Patienten mit akuter Cystitis isoliert wurde. Er gehört zur phylogenetischen Gruppe D und besitzt den Serotyp O17:K52:H18. Er ist Repräsentant einer Gruppe resistenter Erreger.[70]

Der Serotyp O104:H4 Klon HUSEC041 (Sequenztyp 678) enthält Virulenzfaktoren, die sowohl für STEC als auch für EaggEC typisch sind. Im Zusammenhang mit der HUS-Epidemie 2011 in Norddeutschland wird dieser Hybrid für die besonders schwere Verlaufsform verantwortlich gemacht.[71]

Seit 1988 führt Richard Lenski ein Langzeitexperiment über die Evolution von E. coli durch. Jeden Tag werden die Kulturen in ein frisches Medium überimpft und tiefgefroren. So können neue besser angepasste Stämme wieder gegen ihre Vorfahren antreten und geprüft werden, ob sie sich besser an ihre Erlenmeyerkolbenumgebung angepasst haben. Es werden parallel die Veränderungen im Genom ermittelt, wobei die Innovationsrate kontinuierlich abnahm, je besser sich die Kulturen angepasst hatten. Es wurden auch Parallelversuche mit Myxococcus xanthus gemacht, das E. coli jagt und frisst, sowie Temperatur und Medium variiert. Unter konstanten Bedingungen ohne Fressfeinde und nur einem Zucker (Glucose) wurde dem Nährmedium auch Citrat zugegeben, obwohl E. coli dieses nicht verwerten kann. Im Jahr 2003 dominierte plötzlich ein Citrat-verwertender Mutant, der nachweislich von der Ursprungskultur abstammte.[72]

Mittels gentechnisch veränderter E. coli ist es möglich, Biosensoren für Schwermetalle wie Arsen herzustellen. Die natürlichen Mechanismen werden hierbei mit Reportergenen wie β-Galactosidase, bakteriellen Luciferasen (lux) oder dem Grün fluoreszierendem Protein (GFP) gekoppelt. Auf diese Weise ist es möglich, kostengünstig Arsenite und Arsenate unterhalb eines Mikrogramms zu detektieren.[73]

Die Kombination von ringförmiger separat in der Bakterienzelle vorliegender DNA, den sogenannten Plasmiden, mit der Entdeckung des Restriktionsenzyms EcoRI, das doppelsträngige DNA spezifisch schneidet und identische überstehende Enden zurücklässt, war die Geburtsstunde der Gentechnik. Um rekombinante DNA (künstlich hergestellte DNA) zu erhalten, wird bei einer typischen Klonierung zunächst das DNA-Fragment der Wahl und anschließend die plasmidische DNA eines so genannten Klonierungsvektors mit Restriktionsenzymen geschnitten. Durch eine Ligation werden die Enden des DNA-Fragmentes und des Plasmides zusammengefügt und anschließend in E. coli transformiert. Auf diese Weise können beispielsweise artfremde Gene in E. coli eingebracht werden, sodass dieses die auf der DNA codierten fremden Proteine synthetisieren kann.[74] Aus E. coli wird auch das Restriktionsenzym EcoRV verwendet.

Moderne künstlich hergestellte Plasmide (Vektoren oder „Genfähren“) wie pUC19 enthalten zusätzliche Antibiotika-Resistenzgene um Bakterienzellen ohne einklonierte Plasmide auf Selektivnährböden abzutöten. Eine weitere Möglichkeit zur Selektion transformierter Kolonien ist das blue-white-screening. Das Gen lacZ codiert das Protein β-Galactosidase, welches in Anwesenheit von IPTG synthetisiert wird und das künstliche Glycosid X-Gal in einen blauen Farbstoff spaltet. Nicht-transformierte Zellen erscheinen also blau auf einen Nährboden mit X-Gal. Schneidet ein Restriktionsenzym innerhalb des lacZ-Gens und wird erfolgreich ein Fremdgen eingebracht, so wird die Sequenz zur Expression von β-Galactosidase dermaßen zerstört, dass keine α-Komplementation mehr möglich ist. Erfolgreich transformierte Zellen erscheinen also weiß. Das lacZ dient hierbei somit als Reportergen. Der Test funktioniert nur mit der Deletions-Mutante lacZΔM15, deren defekte β-Galactosidase auf die α-Komplementation angewiesen ist.[75]

Zwingt man E. coli zur Überexpression von heterologen Proteinen, kann es zu Problemen bei der Proteinfaltung kommen. Es kommt zur Anhäufung fehlgefalteter und somit biologisch inaktiver Proteine (Einschlusskörperchen). Eine Strategie um die Ausbeute an löslichem Protein zu steigern, ist die Kultivierung bei niedrigen Temperaturen. Hierfür koexprimiert man im mesophilen E. coli die Faltungshelferproteine (Chaperonine) Cpn10 and Cpn60 aus dem psychrophilen Bakterium Oleispira antarctica, die bei 4–12 °C arbeiten. Sie werden unter dem Markennamen ArcticExpress von der Firma Agilent vertrieben. Zusätzlich werden Stämme angeboten, die weitere tRNAs besitzen um dem limitierenden Codon Bias bei der Translation DNA fremder Organismen in rekombinante Proteine entgegenzuwirken.[76]

E. coli XL1-Red ist ein Stamm, der in der Molekularbiologie und Gentechnik zur ungerichteten Mutagenese genutzt wird. Durch Defekte im DNA-Reparaturmechanismus zeigt der Stamm eine 5000-fache Mutationsrate gegenüber dem Wildtyp jedoch auch eine deutlich geringere Wachstumsrate (Verdopplung alle 90 min. bei 37 °C). Die Defekte im Reparaturmechanismus der DNA-Vervielfältigung gehen auf drei Mutationen der genomischen DNA zurück. Das Gen MutS enthält Mutationen der DNA-Mismatch-Reparaturproteine. Durch die Mutation erfolgt keine Fehlbasenreparatur nach der DNA-Replikation. MutD löst einen Defekt der 3'-5'-Exonukleaseaktivität der DNA-Polymerase III aus. MutT ist für die Unfähigkeit zur Hydrolyse des Basenanalogons oxo-dGTP verantwortlich.[77] Zur Mutationsauslösung werden also weder Mutagene noch Karzinogene benötigt. Die Generierung von Genmutationen ist ein klassisches Mittel in der molekularbiologischen Forschung, um generelle oder Teilfunktionen des entsprechenden Gens zu charakterisieren.

Die erste kommerzielle biotechnologische Anwendung war die Produktion des menschlichen Hormons Somatostatin von der Firma Genentech mittels genetisch veränderten E. coli. Die großtechnische Herstellung von Insulin und Wachstumshormonen folgte kurz darauf.[74] Das derart hergestellte Insulinpräparat wird in der Behandlung von Diabetes mellitus eingesetzt. Hierfür ist E. coli besonders geeignet, da es zur Darmflora des Menschen gehört und so gut wie keine Allergien verursacht. Auch in der industriellen Herstellung von Aminosäuren, Interferon sowie weiterer Feinchemikalien, Enzyme und Arzneistoffe, werden gentechnisch veränderte E. coli Bakterien verwandt.[78] So wurden neun von 31 therapeutischen Proteinen, die im Zeitraum von 2003 bis 2006 eine Arzneimittelzulassung erhalten haben, in E. coli hergestellt.[79]

Um E. coli in biotechnologischen Anwendungen leichter handhaben zu können, züchtete ein Team um Frederick Blattner (University of Wisconsin) einen Stamm, dessen Genom gegenüber natürlich vorkommenden Varianten um ca. 15 Prozent verkleinert wurde, und der dennoch lebens- und fortpflanzungsfähig ist. Hierfür wurden zwei unterschiedliche E. coli Stämme verglichen und diejenigen Gene entfernt, die kein Homolog im jeweils anderen Stamm haben und somit entbehrlich scheinen.[80]

Die Herstellung von Biotreibstoffen aus Proteinen ist mit genetisch veränderten E. coli, die drei exogene Transaminierungs- und Desaminierungszyklen enthalten, möglich. Die Proteine werden zunächst durch Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Bacillus subtilis, Mikroalgen (zur gleichzeitigen CO2-Fixierung) oder E. coli selbst hergestellt. Die Proteine könnten auch aus Abfällen von Fermentationen, Lebensmittelverarbeitung, und Bioethanolherstellung stammen. Anschließend werden die Hydrolysate in C4- und C5-Alkohole mit 56 % der theoretischen Ausbeute umgewandelt. Der entstehende Stickstoff kann in Düngemittel umgewandelt werden.[81]

Durch Veränderungen im Stoffwechsel von E. coli können höhere Alkohole wie Isobutanol, 1-Butanol, 2-Methyl-1-butanol, 3-Methyl-1-butanol und 2-Phenylethanol aus der C-Quelle Glucose produziert werden. Hierfür wird der hochaktive Biosyntheseweg für Aminosäuren verwendet und die 2-Ketosäureintermediate zur Alkoholsynthese verwendet. Verglichen mit dem klassischen Biotreibstoff Ethanol ist die höhere Energiedichte und die niedrige Hygroskopie hervorzuheben. Zudem haben verzweigtkettige Alkohole höhere Octanzahlen.[82]

Bakterien können sich bei Nährstoffmangel gegenseitig helfen. So wurde bei genetisch veränderten Escherichia coli und Acinetobacter baylyi beobachtet, wie sich E. coli mit Acinetobacter baylyi durch bis zu 14 Mikrometer lange Nanokanäle verbunden hat, um zytoplasmatische Bestandteile auszutauschen. Die beiden Bakterien wurden so verändert, dass sie für sich notwendige Aminosäuren nicht mehr produzieren konnten, die für die andere Art notwendigen Aminosäuren aber produzierten. Darauf hin bildete E. coli Nanokanäle aus, um sich mit Acinetobacter baylyi zu verbinden und zu überleben. Unklar ist noch, ob Bakterien gezielt steuern können, an welche Zelle sie sich anheften und ob diese Verbindung parasitischer Natur ist.[83]

Im Zuge der GeneSat-1-Mission wurden am 16. Dezember 2006 E. coli mittels eines Cubesat in den Orbit befördert, um genetische Änderungen aufgrund von Strahlungen im All und der Schwerelosigkeit zu untersuchen.[84]

Escherichia coli (abgekürzt E. coli) – auch Kolibakterium genannt – ist ein gramnegatives, säurebildendes und peritrich begeißeltes Bakterium, das normalerweise im menschlichen und tierischen Darm vorkommt. Unter anderem auf Grund dessen gilt dieses Bakterium auch als Fäkalindikator. E. coli und andere fakultativ anaerobe Organismen machen etwa 1 ‰ der Darmflora aus.

Innerhalb der Familie der Enterobakterien (altgriechisch ἕντερον, lateinisch enteron „Darm“) gehört E. coli zur bedeutenden Gattung Escherichia und ist deren Typspezies. Benannt wurde es nach dem deutschen Kinderarzt Theodor Escherich, der es erstmals beschrieb. Coli ist der lateinische Genitiv von colon (zu dt. Kolon), einem Teil des Dickdarms.

Die meisten Angehörigen dieser Spezies sind nicht krankheitsauslösend, jedoch gibt es auch zahlreiche verschiedene pathogene Stämme. Es zählt zu den häufigsten Verursachern von menschlichen Infektionskrankheiten. Die Basensequenz des Genoms einiger Stämme ist vollständig aufgeklärt. Als Modellorganismus zählt es zu den am besten untersuchten Prokaryoten und nimmt in der Molekularbiologie eine wichtige Rolle als Wirtsorganismus ein. Der Nobelpreis für Physiologie oder Medizin wurde an zahlreiche Forscher, die sich mit der Biologie von E. coli beschäftigt haben, vergeben.

Escherichia coli (/ˌɛʃəˈrɪkiə ˈkoʊlaɪ/)[1][2] is a Gram-negative, facultative anaerobic, rod-shaped, coliform bacterium of the genus Escherichia that is commonly found in the lower intestine of warm-blooded organisms.[3][4] Most E. coli strains are harmless, but some serotypes such as EPEC, and ETEC are pathogenic and can cause serious food poisoning in their hosts, and are occasionally responsible for food contamination incidents that prompt product recalls.[5][6] Most strains are part of the normal microbiota of the gut and are harmless or even beneficial to humans (although these strains tend to be less studied than the pathogenic ones).[7] For example, some strains of E. coli benefit their hosts by producing vitamin K2[8] or by preventing the colonization of the intestine by pathogenic bacteria. These mutually beneficial relationships between E. coli and humans are a type of mutualistic biological relationship — where both the humans and the E. coli are benefitting each other.[9][10] E. coli is expelled into the environment within fecal matter. The bacterium grows massively in fresh fecal matter under aerobic conditions for three days, but its numbers decline slowly afterwards.[11]

E. coli and other facultative anaerobes constitute about 0.1% of gut microbiota,[12] and fecal–oral transmission is the major route through which pathogenic strains of the bacterium cause disease. Cells are able to survive outside the body for a limited amount of time, which makes them potential indicator organisms to test environmental samples for fecal contamination.[13][14] A growing body of research, though, has examined environmentally persistent E. coli which can survive for many days and grow outside a host.[15]

The bacterium can be grown and cultured easily and inexpensively in a laboratory setting, and has been intensively investigated for over 60 years. E. coli is a chemoheterotroph whose chemically defined medium must include a source of carbon and energy.[16] E. coli is the most widely studied prokaryotic model organism, and an important species in the fields of biotechnology and microbiology, where it has served as the host organism for the majority of work with recombinant DNA. Under favourable conditions, it takes as little as 20 minutes to reproduce.[17]

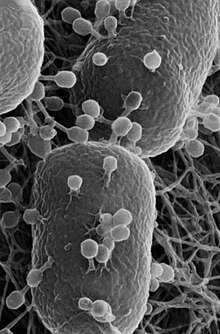

E. coli is a Gram-negative, facultative anaerobe, nonsporulating coliform bacterium.[18] Cells are typically rod-shaped, and are about 2.0 μm long and 0.25–1.0 μm in diameter, with a cell volume of 0.6–0.7 μm3.[19][20][21]

E. coli stains Gram-negative because its cell wall is composed of a thin peptidoglycan layer and an outer membrane. During the staining process, E. coli picks up the color of the counterstain safranin and stains pink. The outer membrane surrounding the cell wall provides a barrier to certain antibiotics such that E. coli is not damaged by penicillin.[16]

The flagella which allow the bacteria to swim have a peritrichous arrangement.[22] It also attaches and effaces to the microvilli of the intestines via an adhesion molecule known as intimin.[23]

E. coli can live on a wide variety of substrates and uses mixed acid fermentation in anaerobic conditions, producing lactate, succinate, ethanol, acetate, and carbon dioxide. Since many pathways in mixed-acid fermentation produce hydrogen gas, these pathways require the levels of hydrogen to be low, as is the case when E. coli lives together with hydrogen-consuming organisms, such as methanogens or sulphate-reducing bacteria.[24]

In addition, E. coli's metabolism can be rewired to solely use CO2 as the source of carbon for biomass production. In other words, this obligate heterotroph's metabolism can be altered to display autotrophic capabilities by heterologously expressing carbon fixation genes as well as formate dehydrogenase and conducting laboratory evolution experiments. This may be done by using formate to reduce electron carriers and supply the ATP required in anabolic pathways inside of these synthetic autotrophs.[25]

E. coli have three native glycolytic pathways: EMPP, EDP, and OPPP. The EMPP employs ten enzymatic steps to yield two pyruvates, two ATP, and two NADH per glucose molecule while OPPP serves as an oxidation route for NADPH synthesis. Although the EDP is the more thermodynamically favourable of the three pathways, E. coli do not use the EDP for glucose metabolism, relying mainly on the EMPP and the OPPP. The EDP mainly remains inactive except for during growth with gluconate.[26]

When growing in the presence of a mixture of sugars, bacteria will often consume the sugars sequentially through a process known as catabolite repression. By repressing the expression of the genes involved in metabolizing the less preferred sugars, cells will usually first consume the sugar yielding the highest growth rate, followed by the sugar yielding the next highest growth rate, and so on. In doing so the cells ensure that their limited metabolic resources are being used to maximize the rate of growth. The well-used example of this with E. coli involves the growth of the bacterium on glucose and lactose, where E. coli will consume glucose before lactose. Catabolite repression has also been observed in E. coli in the presence of other non-glucose sugars, such as arabinose and xylose, sorbitol, rhamnose, and ribose. In E. coli, glucose catabolite repression is regulated by the phosphotransferase system, a multi-protein phosphorylation cascade that couples glucose uptake and metabolism.[27]

Optimum growth of E. coli occurs at 37 °C (99 °F), but some laboratory strains can multiply at temperatures up to 49 °C (120 °F).[28] E. coli grows in a variety of defined laboratory media, such as lysogeny broth, or any medium that contains glucose, ammonium phosphate monobasic, sodium chloride, magnesium sulfate, potassium phosphate dibasic, and water. Growth can be driven by aerobic or anaerobic respiration, using a large variety of redox pairs, including the oxidation of pyruvic acid, formic acid, hydrogen, and amino acids, and the reduction of substrates such as oxygen, nitrate, fumarate, dimethyl sulfoxide, and trimethylamine N-oxide.[29] E. coli is classified as a facultative anaerobe. It uses oxygen when it is present and available. It can, however, continue to grow in the absence of oxygen using fermentation or anaerobic respiration. Respiration type is managed in part by the arc system. The ability to continue growing in the absence of oxygen is an advantage to bacteria because their survival is increased in environments where water predominates.[16]

The bacterial cell cycle is divided into three stages. The B period occurs between the completion of cell division and the beginning of DNA replication. The C period encompasses the time it takes to replicate the chromosomal DNA. The D period refers to the stage between the conclusion of DNA replication and the end of cell division.[30] The doubling rate of E. coli is higher when more nutrients are available. However, the length of the C and D periods do not change, even when the doubling time becomes less than the sum of the C and D periods. At the fastest growth rates, replication begins before the previous round of replication has completed, resulting in multiple replication forks along the DNA and overlapping cell cycles.[31]

The number of replication forks in fast growing E. coli typically follows 2n (n = 1, 2 or 3). This only happens if replication is initiated simultaneously from all origins of replications, and is referred to as synchronous replication. However, not all cells in a culture replicate synchronously. In this case cells do not have multiples of two replication forks. Replication initiation is then referred to being asynchronous.[32] However, asynchrony can be caused by mutations to for instance DnaA[32] or DnaA initiator-associating protein DiaA.[33]

Although E. coli reproduces by binary fission the two supposedly identical cells produced by cell division are functionally asymmetric with the old pole cell acting as an aging parent that repeatedly produces rejuvenated offspring.[34] When exposed to an elevated stress level, damage accumulation in an old E. coli lineage may surpass its immortality threshold so that it arrests division and becomes mortal.[35] Cellular aging is a general process, affecting prokaryotes and eukaryotes alike.[35]

E. coli and related bacteria possess the ability to transfer DNA via bacterial conjugation or transduction, which allows genetic material to spread horizontally through an existing population. The process of transduction, which uses the bacterial virus called a bacteriophage,[36] is where the spread of the gene encoding for the Shiga toxin from the Shigella bacteria to E. coli helped produce E. coli O157:H7, the Shiga toxin-producing strain of E. coli.

E. coli encompasses an enormous population of bacteria that exhibit a very high degree of both genetic and phenotypic diversity. Genome sequencing of many isolates of E. coli and related bacteria shows that a taxonomic reclassification would be desirable. However, this has not been done, largely due to its medical importance,[37] and E. coli remains one of the most diverse bacterial species: only 20% of the genes in a typical E. coli genome is shared among all strains.[38]

In fact, from the more constructive point of view, the members of genus Shigella (S. dysenteriae, S. flexneri, S. boydii, and S. sonnei) should be classified as E. coli strains, a phenomenon termed taxa in disguise.[39] Similarly, other strains of E. coli (e.g. the K-12 strain commonly used in recombinant DNA work) are sufficiently different that they would merit reclassification.

A strain is a subgroup within the species that has unique characteristics that distinguish it from other strains. These differences are often detectable only at the molecular level; however, they may result in changes to the physiology or lifecycle of the bacterium. For example, a strain may gain pathogenic capacity, the ability to use a unique carbon source, the ability to take upon a particular ecological niche, or the ability to resist antimicrobial agents. Different strains of E. coli are often host-specific, making it possible to determine the source of fecal contamination in environmental samples.[13][14] For example, knowing which E. coli strains are present in a water sample allows researchers to make assumptions about whether the contamination originated from a human, another mammal, or a bird.

A common subdivision system of E. coli, but not based on evolutionary relatedness, is by serotype, which is based on major surface antigens (O antigen: part of lipopolysaccharide layer; H: flagellin; K antigen: capsule), e.g. O157:H7).[40] It is, however, common to cite only the serogroup, i.e. the O-antigen. At present, about 190 serogroups are known.[41] The common laboratory strain has a mutation that prevents the formation of an O-antigen and is thus not typeable.

Like all lifeforms, new strains of E. coli evolve through the natural biological processes of mutation, gene duplication, and horizontal gene transfer; in particular, 18% of the genome of the laboratory strain MG1655 was horizontally acquired since the divergence from Salmonella.[42] E. coli K-12 and E. coli B strains are the most frequently used varieties for laboratory purposes. Some strains develop traits that can be harmful to a host animal. These virulent strains typically cause a bout of diarrhea that is often self-limiting in healthy adults but is frequently lethal to children in the developing world.[43] More virulent strains, such as O157:H7, cause serious illness or death in the elderly, the very young, or the immunocompromised.[43][44]

The genera Escherichia and Salmonella diverged around 102 million years ago (credibility interval: 57–176 mya), an event unrelated to the much earlier (see Synapsid) divergence of their hosts: the former being found in mammals and the latter in birds and reptiles.[45] This was followed by a split of an Escherichia ancestor into five species (E. albertii, E. coli, E. fergusonii, E. hermannii, and E. vulneris). The last E. coli ancestor split between 20 and 30 million years ago.[46]

The long-term evolution experiments using E. coli, begun by Richard Lenski in 1988, have allowed direct observation of genome evolution over more than 65,000 generations in the laboratory.[47] For instance, E. coli typically do not have the ability to grow aerobically with citrate as a carbon source, which is used as a diagnostic criterion with which to differentiate E. coli from other, closely, related bacteria such as Salmonella. In this experiment, one population of E. coli unexpectedly evolved the ability to aerobically metabolize citrate, a major evolutionary shift with some hallmarks of microbial speciation.

In the microbial world, a relationship of predation can be established similar to that observed in the animal world. Considered, it has been seen that E. coli is the prey of multiple generalist predators, such as Myxococcus xanthus. In this predator-prey relationship, a parallel evolution of both species is observed through genomic and phenotypic modifications, in the case of E. coli the modifications are modified in two aspects involved in their virulence such as mucoid production (excessive production of exoplasmic acid alginate ) and the suppression of the OmpT gene, producing in future generations a better adaptation of one of the species that is counteracted by the evolution of the other, following a co-evolutionary model demonstrated by the Red Queen hypothesis.[48]

E. coli is the type species of the genus (Escherichia) and in turn Escherichia is the type genus of the family Enterobacteriaceae, where the family name does not stem from the genus Enterobacter + "i" (sic.) + "aceae", but from "enterobacterium" + "aceae" (enterobacterium being not a genus, but an alternative trivial name to enteric bacterium).[49][50][51]

The original strain described by Escherich is believed to be lost, consequently a new type strain (neotype) was chosen as a representative: the neotype strain is U5/41T,[52] also known under the deposit names DSM 30083,[53] ATCC 11775,[54] and NCTC 9001,[55] which is pathogenic to chickens and has an O1:K1:H7 serotype.[56] However, in most studies, either O157:H7, K-12 MG1655, or K-12 W3110 were used as a representative E. coli. The genome of the type strain has only lately been sequenced.[52]