ar

الأسماء في صفحات التنقل

The scientific name for this species is somewhat misleading. Pan refers to the greek god of forests, and is not entirely inappropriate for these animals. However the term troglodytes means one who crawls into holes or caves. As demonstrated in the report above, these animals do not typically use caves.

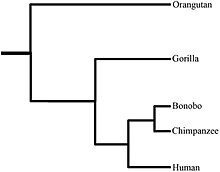

Relationships among the subspecies are of interest to many, especially those seeking to understand human diversity by looking at diversity in our closest relatives. Research on the DNA of these subspecies indicates that P. troglodytes troglodytes and P. troglodytes schweinfurthi are most closely related. Their lineages likely separated around 440,000 years before present. In contrast, the lineage of P. t. verus separated from the other common chimpanzees around 1.58 million years before present. Because of this relatively distant relationship, some researchers believe that P. t. verus may warrant elevation to species status.

Communication in this highly social species is an area of great interest to human researchers. Chimpanzees in captivity have been involved in a number of experiments designed to show how their minds work with regard to signs, signals, and speech. In this account, communication in wild chimpanzees will be discussed first, followed by a discussion of what language studies in captivity have helped us to understand about these animals.

Visual Communication

Chimpanzees communicate with a wide variety of gestures, postures, and facial expressions. In addition, body language and physical cues are used in communication.

Gestures such as arm raising, slapping the ground, or a direct stare are threatening signals used between individuals. Male courtship signals, like branch shaking or foot stamping, may be directed at particular female with whom he wishes to mate. Some facial expressions and vocalizations may also be directed at particular individuals. Loud arm scratching while looking at another individual may be interpreted as a request for grooming.

When excited or fearful, chimps may show low closed grins, full closed grins, or open grins. Snears may also be shown in a fearful context. When the distress is less severe, communicative facial expressions include pouts and horizontal pouts. Compressed lips are often used in threatening displays, and play is generally accompanied by a “play face”, in which the chimp has an open smile with top teeth covered.

Erection of body hair (piloerection) is an important signal communicating excitement. It occurs in most chimps when a strange or frightening stimulus is encountered, during times of aggression, and in other contexts of social excitment. This bristling of the hair is an autonomic response, so it is not under the conscious control of an individual animal. It is a reliable signal of excitement in this species, just as blushing is a reliable signal of embarrassment in humans.

In times of fear induced by the behavior or presence of a dominant animal, chimpanzees never show piloerection. Instead, they have incredibly sleek hair, making them appear smaller. Also, the alpha male chimpanzee in a community, although not frightened or excited, almost always has bristled hair--making him appear even larger than he is.

The swelling of the anogenital skin of females clearly communicates their sexual state to other members of the community. Because the bright pink swelling is highly visible, even at a distance, and can be seen by all, it is considered a non-directed signal.

Auditory Communication

All chimpanzee vocalizations are closely tied to their emotions. Their vocalizations are usually spontaneous, signalling the excitment of arriving at a food source, greeting of old friends, or moments of acute fear or distress. However, producing a particular vocalizations without experiencing the underlying emotion seems to be a task that surpasses a chimpanzee's abilities. Conversely, chimps can learn through experience to suppress a particular call in contexts where the vocalizations may lead to an unwelcome result.

Chimpanzees can be quite vocal. They use a variety of grunts, barks, squeaks, whimpers, and screams. Each call is typically tied to a particular emotional context, such as fear, excitment, bewilderment, or annoyance, so that vocalizations provide information to other chimps about what is happening to other members of their community, even if they cannot see them directly. Subordinate animals direct pant-grunts at more dominant animals. During grooming, chimpanzees often lip-smack or tooth-clack. Play is often accompanied by laughter which, although very raspy-sounding to humans, is similar enough to our own laughter to be easily recognized. Some vocalizations (food grunts) attract other party members to an plentiful food source. Some louder vocalizations (food aaa calls) may attract other chimpanzees in the community from a greater distance. The famous “pant hoot” call of chimps seems to serve as a means of individual identification, and allows friends and family to locate one another even though they may not be within visual range. A detailed listing of calls made by the chimps of Gombe is available in Goodall (1986), and should be consulted by those wishing to know more about specific calls.

That chimpanzees understand the meaning of their vocalizations is clear from contexts in which they purposefully supress vocalizations. Although typically vocal--especially when traveling in groups-- male chimpanzees are almost entirely silent when they are performing a border patrol, or when raiding into the home range of a neighboring group. It is as if they understand that the success of their mission depends upon remaining covert, and that vocalizations will assuredly attract the notice of neighboring animals whom they would prefer to surprise. Similarly, during the course of a consortship, both male and female remain almost entirely silent. This silence may serve two different functions. First, it may prevent the pair from being discovered by other males in the community, disrupting the temporarily monogamous union. Second, because most consortships take place on the outskirts of the community’s range, silence helps the consorting pair to avoid attracting the attention of neighboring males, who may themselves be out patrolling their borders.

Tactile Communication

Various forms of tactile communication occur between pairs of chimps. Physical contact helps to reassure distressed individuals, to placate aggressive individuals, and to appease stress. Embracing, patting, kissing, mounting, and touching all occur in a variety of contexts, including greetings, reconciliations, and reunions. As mentioned in the section on behavior, relaxed physical contact is provided by frequent bouts of social grooming. Such friendly contact helps to cement social bonds. Playful contact, such as finger wrestling or tickling may also occur.

Although the bulk of physical contact seen in chimpanzees is friendly, there is also physical contact associated with aggression. Hitting, slapping, kicking, and biting also occur, as do pounding, dragging, and stamping. Although such aggressive physical contact usually occurs between two individuals as the result of a specific conflict, it may also sometimes be incidental, as when a chimpanzee is in the wrong place at the wrong time, and becomes incorporated into the display of a dominant or irritated individual.

Chemical Communication

Chimpanzees are very interested in smells, and seem to be using them in a variety of contexts. However, the degree to which they use smells, or the specific information they obtain from smells, is not known. Chimpanzees sniff and smell at the anogenital swellings of females. They smell the ground after a mother with a new infant has moved away, apparently trying to catch the scent of the newborn. Individual chimps may have unique odors, recognized by their fellows, but research on this point is lacking. Wild chimpanzees sometimes appear to use scent cues in tracking missing family members. Olfactory cues may be used in helping males to identifiy the approach of ovulation in females, although the specific mechanism or chemicals used for this have not been described.

Communication Studies in Captivity

Although wild chimpanzees have complex communication, they do not possess what we would call language. They do not use specific calls to identify specific objects or individuals. Indeed, they seem unable to produce vocalizations at will, instead uttering cries and calls as a result of impulsive emotions. However, in spite of having no true language, the mental function of chimpanzees is well developed and they possess many of the cognitive abilities necessary for language to develop, as studies of their acquisition of lexigrams (keyboard symbols) and sign language have shown.

Chimpanzees can be taught large numbers of signs or symbols, which they can use to respond to questions reliably and repeatably. They can identify sizes, shapes, colors, and can distinguish what attributes of objects make them different (e.g., two circles, one blue, one red, differ in color). They can use abstract concepts and generalize. For example, they can know that a wrench is a tool and a banana is a food. They are able to spontaneously mix and use symbols they know to describe novel objects. For example, one chimpanzee described a cucumber as a “banana which is green”. Further, research has demonstrated that chimpanzees can understand spoken language, responding appropriately to requests, even though they are, themselves, unable to speak.

Communication Channels: visual ; tactile ; acoustic ; chemical

Perception Channels: visual ; tactile ; acoustic ; chemical

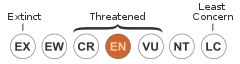

Chimpanzee populations are jeopardized by human expansion into rainforests and mixed forest environments. Humans destroy habitats required by chimpanzees for survival and hunt them for bushmeat. They are listed as an Appendix I species by CITES, and are considered endangered by IUCN redlist. The United States Fish and Wildlife Service consideres the species endangered in the wild, and threatened in captivity outside of the natural range.

US Federal List: endangered

CITES: appendix i

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: endangered

Chimpanzees have been known to prey upon young humans when the opportunity arises, although the propensity for this behavior is closely related to the presence of waste from human beer-making facilities. Chimpanzees eat these attractive, fermented leavings and become intoxicated, making them more likely to become aggressive. When frightened or aggressive chimpanzees can be dangerous, even to adult humans. In addition, because of their biological similarity to humans, they may serve as a reservoir or host for diseases that affect humans.

Negative Impacts: injures humans (bites or stings, carries human disease)

Chimpanzees, being among our closest living relatives, are of tremendous importance in medical research. They are also heavily used in studies of behavior, both in captivity and in the wild. They are the focus of valuable ecotourism enterprises and are popular in zoos. Finally, there is some illegal pet trade in chimpanzees and they are hunted for bushmeat.

Positive Impacts: pet trade ; food ; ecotourism ; research and education

As predators, chimpanzees may be a factor in structuring populations of their prey species. Certainly, they have a strong impact on red colobus monkeys (Colobus mitis) at Gombe, and they are likely to have effects on other species as well. As frugivores, chimps may help to disperse seeds of certain plants, either through transportation, or by processing the fruit. There are competitive interactions with other primates, and so chimpanzees may have an additional negative effect on other primate species.

Various parsites, such as intestinal helminths, trematodes, and schistosomes, have been reported in these animals.

Ecosystem Impact: disperses seeds

Commensal/Parasitic Species:

Chimpanzees are broadly omnivorous. They rely heavily on ripe fruits and young leaves, with additional consumption of stems, buds, bark, pith, seeds, and resins. This diet is supplemented by a variety of insects, small vertebrates, and eggs. Soil is sometimes consumed, especially that associated with termite mounds, presumably for the minerals it contains. Diets vary seasonally, as different foods are available at different times of year. Diets also vary geographically. Some foods eaten by chimpanzees in one location are not eaten by chimpanzees in another location, even when the food in question is present at both locations, making it possible that geographical differences in diet are cultural.

Chimpanzees spend the bulk their time feeding or moving from one food source to another. Although foods may be eaten at any time of the day or night, there are typically two major peaks in feeding activities. The first occurs in the morning between 7 and 9 AM. The other is in the afternoon, between 3:30 and 7:30 PM.

Chimps may use a food source until the food is gone, or they may leave before having consumed all of the food. This may depend upon how many chimps are feeding at the site. Variety in the diet seems to be important, and after consuming enough of a particular food, chimps may move on in search of something else to eat.

Chimpanzees are known to hunt other large vertebrates on occasion. The largest animals hunted are bush pigs (Potamochoerus larvatus), colobus monkeys (Colobinae) and baboons (Papio). Although adults are sometimes taken, it is more common for chimps to take young animals.

The predatory behaviors of chimpanzees vary between sexes, individuals, and locations. Males typically consume more meat than females, who seem to specialize more on insect foods than do males. Chimps in the Ivory Coast are known to use more cooperative hunting techniques than the chimpanzees in Tanzania and Uganda. This may be related to differences in the habitat and the behavior of prey. In the Ivory Coast, there is a well developed canopy to the forest, and monkeys may escape chimp predators by climbing high into the trees. In this situation, only cooperative hunting tactics work well for capturing prey. However, at both Gombe and Mahale in Tanzania, the forest is not as dense, and the upper portions of the canopy are not as well developed. As a result, individuals have high success at hunting without enlisting the aid of other chimps.

Another consequence of habitat differences between western and eastern populations of chimpanzees is that in the east, the colobus monkeys preyed cannot take refuge in areas inacessible to chimpanzees. Under these conditions, colobus monkeys are more aggressive toward the chimpanzees. Coupled with the smaller size of the subspecies of chimp found in this area (P. t. schweinfurthi), a different dynamic is established between predator and prey. Chimpanzees in this area are sometimes fearful of adult male monkeys, and are most likely to attack females with young, in the hope of snatching a baby monkey to eat.

Cannibalism has been reported in chimpanzees. The circumstances under which this behavior has been observed vary, although typically chimps do not kill and eat members of their own communities. Most commonly, infants killed during intercommunity aggression may be eaten by the males of the neighboring community. However, in a famous case at Gombe, an adult female and her adolescent daughter were responsible for killing several infants of other females in their community. These infants were eaten, often in front of the mother. This behavior ended when the adult female died. The daughter has shown no inclination toward cannibalism since her mother's death.

Captive chimps commonly exhibit coprophagy and repetitive regurgitation and reingestion. These behaviors appear to be an aberration seen in captivity, as they are not found in wild chimpanzees.

Finally, sick chimpanzees are known to consume a variety of plants with potentially medicinal value. For a more comprehensive discussion of this behavior, please refer to the behavior section.

Animal Foods: birds; mammals; reptiles; eggs; insects

Plant Foods: leaves; wood, bark, or stems; seeds, grains, and nuts; fruit; flowers; sap or other plant fluids

Primary Diet: omnivore

Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) inhabit the tropical forests of central Africa. They are distributed from about 10 degrees N to 8 degrees S, and from 15 degrees W to 32 degrees E. They are found from Gambia in the west to Uganda in the east, excluding the region bordered by the Congo and Lualaba rivers in central Zaire (Congo) where their sister species, bonobos (Pan paniscus), are found.

There are three recognized subspecies of common chimpanzee. Pan troglodytes verus occurs in the western portions of the range, from Gambia to the Niger river. From the Niger river to Congo, in the central portion of the range, P. troglodytes troglodytes inhabits forested regions. In the far eastern portion of the range, from the northwestern corner of Zaire into western Uganda and Tanzania, P. troglodytes schweinfurthi is found.

Biogeographic Regions: ethiopian (Native )

Chimpanzees utilize a great diversity of habitat types. Although they are typically thought of as living in tropical rainforests, they are also found in forest-savanna mosaic environments, as well as in montain forests at elevations up to 2,750 m. Some populations are known to inhabit primarily savanna habitat.

Range elevation: 0 to 2,750 m.

Habitat Regions: tropical ; terrestrial

Terrestrial Biomes: savanna or grassland ; chaparral ; forest ; rainforest ; scrub forest

Chimpanzees can live from 40 to 60 years.

A variety of ailments trouble chimpanzees in natural habitats, and affect survivorship and longevity. Respiratory diseases, such as colds and coughs, seem prevalent during the rainy season. Gastrointestinal problems, such as diarrhea, peritonitis, and enteritis have been seen and can be lethal, especially in young or very old chimps. Skin ulcers and osteoarthritis have affected some chimpanzees. One chimpanzee at Gombe had a goiter. Abcesses of various sorts have been seen, as have rashes, fungal diseases, and parasitic infections. Even human diseases may sometimes affect wild chimpanzees. A polio epidemic in local human populatons devastated the chimpanzees at Gombe Stream National Park in 1966, killing some and leaving many chimpanzees partially paralyzed.

In addition to disease, injuries are an important source of infections and can lead to mortality in chimpanzees. Injuries may be sustained during falls, or as a result of aggressive interactions within groups or among neighboring groups.

Range lifespan

Status: captivity: 59 (high) years.

Average lifespan

Status: wild: 51.0 years.

Average lifespan

Sex: male

Status: captivity: 56.0 years.

Average lifespan

Status: captivity: 44.5 years.

Average lifespan

Status: wild: 60.0 years.

Average lifespan

Status: captivity: 53.0 years.

Average lifespan

Status: wild: 45.0 years.

Average lifespan

Status: wild: 50.0 years.

Average lifespan

Status: captivity: 40.0 years.

Average lifespan

Sex: female

Status: captivity: 59.4 years.

Adult chimpanzees have a head and body length ranging between 635 and 925 mm. When standing erect, they are 1 to 1.7 m tall. In the wild, males weigh between 34 and 70 kg, whereas females are slightly smaller, weighing between 26 and 50 kg. In captivity individuals typically attain greater weights, with the top weight reaching 80 kg for males and 68 kg for females. Although data from individual subspecies are not available, it appears that P. t. schweinfurthi is smaller than P. t. verus, which is smaller than P. t. troglodytes. Some of the differences seen between captive chimps and wild chimps may be due to subspecific differences in size.

The arms are long, such that the spread of the arms is 1.5 times the height of an individual. Legs are shorter than are the arms, which allows these animals to walk on all fours with the anterior portion of the body higher than the posterior. Chimpanzees have very long hands and fingers, with short thumbs. This hand morphology allows chimpanzees to use their hands as “hooks” while climbing, without interference from the thumb. In trees, chimpanzees may move by swinging from their arms, in a form of brachiation. Although useful in locomotion, the shortness of the thumb relative to the fingers prevents precision grip between the index finger and thumb. Instead, fine manipulations require using the middle finger in opposition to the thumb.

The long hands of chimpanzees also function in quadrupedal locomotion. Fingertips are typically curled upward into the palm during locomotion, and the weight is borne along backs of the fingers. Much of the length of the hand thus contributes to the length of the forelimbs while walking. In combination with the short legs, this gives the back a downward slope from neck to rump, and orients the head into a forward facing position.

Chimpanzees have prominent ears, and a prominent superorbital crest. This gives the brows a somewhat rigid and bony appearance. A sagittal crest may be present on very large individuals, but is not common. There is no nuchal crest. Cranial capacity of these animals ranges from 320 to 480 cc. The face is slightly prognathic. The lips protrude and are very flexible, allowing an individual to accomplish many tasks through labial manipulation.

Dentition is typical of primates. The dental arch is square in shape, and there is a prominent diastema. Canines are large, as are molars. Molars decrease in size toward the back of the mouth, and lack the enamel wrinkling seen in orangutans.

The face of adults is typically black, or mottled with brown. Hair is black to brown, and there is no underfur present. There may be some white hairs around the face (looking a bit like a white beard in some individuals). Infant chimpanzees have a white tuft of hair on their rumps, which identifies their age quite clearly. This white tail tuft is lost as an individual ages.

Individuals of both sexes are prone to lose the hair on the head as they age, producing a bald patch behind the brow ridge. Graying of hairs in the lumbar region and on the back is common with age, also.

Range mass: 26 to 70 kg.

Range length: 635 to 925 mm.

Other Physical Features: endothermic ; homoiothermic; bilateral symmetry

Sexual Dimorphism: male larger

Chimpanzees are hunted as food by humans in many parts of their range. There is no direct evidence of predation on chimps by other animals, although there are some sympatric predators that are likely candidates for taking an occasional chimpanzee--especially young ones. These are leopards (Panthera pardus), pythons (Phython sabae), and martial eagles (Poleamaetus bellicosus).

Known Predators:

Chimpanzee reproduction is very complex, and many misconceptions arose early in the study of these animals about the nature of their mating system. Both males and females are known to mate with multiple partners, so they can be considered polygynandrous. However, at times a male may control sexual access to a female, preventing other males from mating with her. A male may do this either through force and dominance in a group mating situation, or by taking the female on a consortship away from other males and thereby securing exclusive sexual access to her. Each of these situations will be discussed at length below.

It is important to note that copulation may serve a number of social functions in this species. Females and males mate more often than would be necessary to ensure impregnation. Copulation may help to develop bonds between males and females. It may funtion in establishing and maintaining group unity.

Females have an estrus cycle which lasts approximately 36 days. During the course of this cycle, as her hormone levels change, a female experiences changes is the size, shape, and color of her genital skin. As circulating estrogens increase during the follicular phase of the cycle, the size of the swelling increases. When the anogenital skin is fully engorged, it is typically bright pink, and can measure from 938 to 1400 cc. The state of maximal tumescence is of variable length in different individuals and at different stages of maturity, but lasts an average of 6.5 days. It is during this time that females are sexually receptive and that the bulk of copulations with mature males occur.

The anogenital swelling of females is very important in the sexual behavior of these animals. Most copulations involving mature males and females (96.2%) seen at the Gombe Stream National Park in Tanzania were observed with females who were maximally tumescent. Of the few copulations observed when females were not maximally swollen, almost 75% were performed by one of two adult males, indicating that the propensity to copulate with females who are not at their peak swelling may be something of an individual idiosynchracy.

The role of the anogenital swelling is many-fold. First, it serves as a signal, visible to males from a great distance, that a female is sexually receptive. Since females tend to be relatively solitary, advertizement of their sexual state to potential mates is essential for reproduction to occur. Males are very interested in the condition of the genitals of each female they encounter. Second, the anogenital swelling may aid females in obtaining food resources including meat. Females who are maximally swollen are often able to supplant more dominant animals at a food source, and are more successful at begging food from males than are unswollen females. Finally, because the males find sexual swellings so attractive, having a maximally engorged genital region may help stranger females to interact peacefully with unfamiliar males as they disperse into new areas.

There are several possible mating scenarios that males and females may encounter. Each of these is based in part on the phase of the female’s cycle. A female may experience one or more of these scenarios during a particular cycle. The types of situations she encounters depend upon a female’s popularity as a sexual partner, how many other females are in estrus at the same time, how popular those females are, and how attractive the female is to the dominant male.

First, during early tumescence, females are mated by infants, juveniles and early adolescents. Infants and juveniles are probably gaining experience through the copulation, they are unlikely to sire offspring. Mature males do not typically copulate with females until they are maximally tumescent, although exceptions to this rule have been observed.

In the second sexual scenario, a female who has achieved maximal tumescence becomes the nucleus of a multi-male party. Other estrus females may travel in the same sexual party. These parties can include some or all of community males. During this phase of a female’s cycle, mating can be promiscuous. The males are typically not comepetitive in this situation, and different males may mate with the female in rapid succession.

The third situation a female might encounter occurs during the second half of maximal tumescence. As the timing of ovulation approaches, dominant males may become possessive and prevent subordinates from copulating with the female. This may involve outright conflicts or, because the dominance relationship between males is well established, may be as simple as the dominant male maintaining close proximity to the female, thereby communicating to his subordinates that the female is no longer up for grabs. Inhibition of the copulations of other males may also occur through threats or attacks. Interestingly, these attacks and threats are often directed at the female, should she express sexual interest in another male. Directing aggression toward the female benefits the male in several ways: 1) it prevents potentially costly fights with other large males, 2) it teaches the female not to copulate with anybody else, and 3) it prevents a third male from mating with the female while the possessive male is punishing another sexual rival. If the possesive male is the highest ranking male in a party, he can inhibit copulations between the female and all other males.

The result of this restriction of mates late in the course of maximal tumescence has the effect of reducing the number of potential sires for any offspring conceived during that estrus cycle. Since sperm remain viable in the fallopian tubes for 48 hours, only males copulating with a female during the last four days of her swelling could fertilize an egg. Even though a female may mate with many males during any particular cycle, not all of these matings have the potential of resulting in impregnation.

The fourth sexual mating situation is the consortship. During a consortship, the female may be led away from the group by a particular male. When consorting, male/female pairs often move to the periphery of the community range. Pairs can stay together up to 3 months. During consortship, both members of the pair maintain relative vocal silence, helping to avoid the attention of other community members, as well as attention from the males of neighboring communities who might behave with hostility toward the pair. Consortships inherently involve the cooperation of female.

Whether males engage in any of these sexual scenarios is highly variable among individuals. A male's preference for, or success in, group mating versus consortships may change depending upon the rise and fall of his fortunes in the constant struggle for dominance between community males. Males who are actively moving up the dominance heirarchy may not spend time away from other males frequently, as in doing so, they may sacrifice social status. Such males, who are in their prime, are more likely to be able to monopolize sexual access to a female in a group situation. High ranking males, especially the alpha male, may take females on consortships, but because of the need to maintain their social standing, these consortships tend to be short in duration.

It may benefit lower-ranking males to initiate consortships when possible, as in consortships there is no mating competition from other males. This may represent the most likely chance the male has to sire offspring. However, it is harder to entice a female to come on a consortship if she is close to ovulation because of competition/possessiveness of other males. A female may benefit from consortships by being able to choose the male with whom she mates. There may also be better access to food and reduced aggression during a consortship as compared to a group mating situation. However, these benefits must be weighed against the potential cost of encountering hostile neighboring chimpanzee groups when spending time in the periphery of the range.

Most consortships (40%) at Gombe Stream National Park were initiated when a female was maximally swollen. Only 16% of consortships were intiated when the female was at variable tumescence, and even fewer consortships began when females were flabby (12%) or pregnant (12%).

To initiate a consortship, a male may gaze toward the female he desires to consort with. This is often accompanied by piloerection (fluffed-out hair), branch shaking, arm stretching, and rocking. If the male succeeds in getting the female to follow him away from the group, he will often walk while looking over his shoulder to make sure she’s still tagging along. This sequence of behaviors may be repeated until the female follows him. If the female does not comply with the male’s wishes, he may become hostile, using aggression to force her to follow him.

During just over half of fertile cycles, females are confined to multi-male groups. About 21% of fertile cycles occur on consortships. The remaining 15% of cycles occur when young females visit males in other communities. In spite of the numbers of fertile cycles which fall under each mating situation, females are disproportionately likely to conceive during consortships. The exact mechanism of this is not understood.

Male mate choice

Because males become possesive of females only late in the course of maximal tumescence, it appears that they have some ability to discern the fertile period of females. The ability of male chimpanzees to gauge the potential fertility of a given female can unquestionably be inferred from patterns of copulations. The increase in the copulation frequency of dominant or older males as ovulation approaches demonstrates that males do not respond the same to females throughout the duration of maximal tumescence. Copulations increase as fertilization and impregnation become more likely. In addition, females who were presumed to be undergoing nonfertile cycles (such as during pregnancy and early in the postpartum period) are typically not sexually popular with mature males.

Aside from potential fertility, one characteristic involved in male mate choice is the age of the female. When presented with two receptive females, males typically show a preference for copulating with the older of the two. Personality traits of individual females may also contribute to males favoring them. A female who is relaxed in the presense of males may be prefered over a more skittish female. Novelty can also play a role in attracting males, since they seem to prefer unfamiliar females over those with whom they have longstanding relationships.

Female mate choice

Females have some ability to choose the males with whom they mate. They may choose to accept or decline a male’s invitation to consortship. This may allow a female to ensure that a particular male who is low in dominance standing, and therefore is less successful in group mating competitions, sires her offspring. The characteristics of males with whom females consort may vary. It seems that the overall “friendliness” of a female’s relationship with a male may play some role in her choice of him as a consortship partner. Whether the male has played with her, groomed her, or engaged in other friendly behaviors with her as she matured or when she is not maximally swollen, may play some role.

Although consenting to a consortship clearly demonstrates choice on the part of the female, it should not be assumed that by staying in a multi-male mating party as ovulation approaches, a female is relinquishing her mate choice. She may be choosing to mate with particular dominant individuals. Or, she may be enhancing her social status and familiarity to all the community males by remaining in the group.

That females discriminate between various males in mating situations is clear. Females avoid copulations with their mature sons and their brothers. There is also some evidence that young females avoid copulations with the older males in their communities (who may potentially have sired them). Although matings do occur between siblings, and occasionally between mothers and their mature sons, the frequency of such matings is much less than would be expected by random pairings of adults within the community.

Initiating a copulation

Copulations are typically initiated by males. The male sits in what is called the “male invite” posture, with his legs flexed and slightly splayed. This displays his erect penis to a potential mate. A male chimpanzee’s penis is bright pink, thin, and tapered to a point. It is very visible against the black hair and pale skin on the male’s lower abdomen and thighs. The value of the erect penis as a signal may be enhanced as the male “flicks” it-- causing the penis to make a rapid “tapping” movement.

In addition to displaying his penis, a courting male may show piloerection (fluffed-out hair). A male may gaze directly at a female. Such a gaze directed at a male rival is an unambiguous threat, but in a sexual context appears to serve as an invitation. He may place his raised hand on a branch overhead, and he may shake the branch. This is all a low-key invitation to the female to present her hindquarters to the male for copulation. If he fails to attract the notice of the female, he may incorporate one or more of the following behaviors into his display: arms outstretched toward the female, a bipedal swagger, a sitting hunch, side to side rocking, swaying of vegetation, or stamping with the foot or knuckes.

Copulation usually occurs in a squatting position after the female crouches and presents her rump to the male. Often, there is no contact between the participants in the mating except at their genitals, although sometimes the male may hold the female.

Ejaculation is usually achieved within 8.8 thrusts. The copulation is ended as the male scoots back or the female darts forward. Males and females have been seen to clean themselves with leaves after copulating. Females not infrequently consume the vaginal plug (congealed semen) after mating.

Mating System: polygynandrous (promiscuous) ; cooperative breeder

There is no clear seasonality in the reproduction of chimpanzees. Females cycle throughout the year, and males copulate with them when they are receptive. Females may have infertile cycles, such as are seen during the period of adolescent sterility, during pregnancy, and early in the postpartum period. Males copulate with females during infertile cycles as well as during fertile cycles. This indicates that there are social functions other than reproduction related to sexual behavior in these animals.

The female reproductive cycle lasts an average of 36 days. As hormone levels change during their cycle, so does the size of the female’s anogenital swelling. There are four main phases to the cycle, including inflation, as the size of the swelling increases, maximal tumescence. when the sexual skin is fully distended, detumescence, when the previously swollen skin looses all turgidity, and flat, when there is no sign of swelling in the anogenital area. Menstruation occurs about nine days after detumescence begins, and lasts for about three days. Ovulation typically occurs on the last day of maximal tumescence.

Females do not reproduce frequently. There is a prolonged period of juvenile dependence during which the offspring relies on the mother for milk, protection, and education. Becuse of the care required by a single offpspring, females cannot produce offspring frequently. The duration of the interbirth interval varies from population to population. Some of the variability may be due to ecological factors (highly productive habitats may allow females to wean their young sooner, or may result in higher rates of infant survival, both of which would affect interbirth intervals). Because different populations may also represent different subspecies, genetic differences in the timing of reproduction may also be involved.

Average interbirth intervals range between 3 and 6 years. Gestation lasts from 202 to 260 days, with a mean of 230 days. Typically, a single young is born, weighing about 2 kg. Twinning is rare, but may be more common than in humans. The infant is carried ventrally by the mother for about 3 to 6 months, after which infants may either ride on their mother’s ventrum or on her back. As the young chimp grows, it increasingly rides on its mother’s back during travel. Although young chimps sometimes walk on their own, they regularly ride on mom until the time of weaning at 3.5 to 4.5 years.

The age of independece is somewhat difficult to judge in this very social species. Young chimps can survive without their mother after they are weaned. However, orphaned chimps are often “adopted” by an older sibling or another close relative, who provides the young chimp with care similar to that which the mother would provide. Young typically travel all the time with their mother until they reach puberty. At puberty, females may become the focus of sexual parties, and males become very interested in establishing themselves in the dominance hierarchy. The activities of maturing chimps around the age of 10 years lead to the parting of ways between a mother and her son.

Females and males enter puberty around the age of 7 years. Females experience a period of adolescent sterility of about three years, during which they cycle, but do not ovulate. During this period, females may transfer into a neighboring chimpanzee community.

As in humans, there is a great deal of variability between different populations and between individuals within populations in the timing of first birth. Female chimpanzees in the wild give birth to their first offspring between the ages of 11 and 23 years. In Tanzania, the average age at which a female first gives birth is between 14.5 and 15 years. Captive chimpanzees reach sexual maturity at younger ages, and have been known to have babies at ages as young a 7.5 years. However, even for well-fed captive animals, the average age at which a female has her first offspring is between 10.5 and 11.15 years.

Like females, males enter puberty around the age of 7 years. Males of any age, including infants, may mate with females, but these copulations are unlikely to result in impregnation of the female. It is not until males attain social maturity that they can effectively compete for access to females who are fertile. In the wild, males are first seen to ejaculate around the age of 9 years. They do not reach adult weight and social maturity until they are about 15 years of age.

In general, chimpanzees can be classified into age categories that represent developmental stages. Until the age of 5 years, chimpanzees are infants. From 5 to 7 years of age, chimpanzees are called juveniles. From 7 to 10 years of age, females are called adolescents. Similarly aged males, from 7 to 12 years are also called adolescents. Females aged 10 to 13 years are considered subadults, as are males aged 12 to 15 years. Females are considered fully adult around the age of 13 years, whereas males reach maturity later, around 15 years.

Breeding interval: The breeding interval varies. Female cycles last about 36 days, and females mate during each cycle. However, if pregnancy ensues, a female may not begin cycling again for 2.5 to 5.5 years.

Breeding season: Chimpanzees may breed throughout the year.

Range number of offspring: 1 to 2.

Average number of offspring: 1.

Range gestation period: 202 to 260 days.

Average gestation period: 230 days.

Range weaning age: 30 to 54 months.

Average time to independence: 6 years.

Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female): 10 to 13 years.

Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male): 12 to 15 years.

Key Reproductive Features: iteroparous ; year-round breeding ; gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); sexual ; viviparous

Average birth mass: 1821 g.

Average number of offspring: 1.

As is true for most mammals, females provide the bulk of parental care. They carry their offspring, groom them, nurse them, and provide them with opportunites to learn all of the complex behavioral patterns of the species. Young are completely dependent upon their mother until weaning at 3 to 4 years of age, but continue to travel with her and rely heavily upon her for support until they reach adulthood. Bonds with the mother extend throughout an individual’s life. In spite of having achieved independence, both males and females may maintain social bonds with their mother for the remainder of their lives. Although females sometimes emmigrate into a new community of chimpanzees, thereby severing ties with their mother, females may also stay in their natal community as adults. In this case, they may occasionally travel with their mother. Males often use their mother for emotional support when establishing themselves in the male dominance hierarchy. When things are not going particularly well for them, some males may seek the comfort, stability, and quiet that only their natal family can provide.

Because multiple young of different ages may be traveling with their mother at any time, bonds between siblings are also strong. These bonds may remain strong during adulthood, and brothers are frequent allies in intragroup intrigues. Older siblings frequently help to carry infants and play with infants. If the mother should die, older siblings will often assume the care of their immature, weaned siblings.

Males do not provide any direct parental care for young, although they can be quite gentle and playful with young members of their community, especially those still possessing a white tail tuft. Males may indirectly provide protection for their young. Adult males in the community engage in border patrols, which may help to protect the young from potentially dangerous stanger males.

The relationship between a mother and her offspring can have many repercussions during the life of the offspring. Although rank is not technically inherited from the mother, the rank of a female does affect her offspring. A mother who has a high rank, who is confident and relaxed in dealing with other chimpanzees, is likely to have offspring who behave in a similar fashion. Nervous mothers may produce offspring who are fearful of other chimpanzees, and who may not do well in dominance competition.

Because young males do not emmigrate at maturity, they inherit the home range of dominant males. There is no certainty of paternity in this polygynandrous species, so transmission is not directly from father to son and it is unlikely that such relatives would recognize one another as such. Females may remain in their natal community also, although they may transfer to a different chimpanzee social unit upon reaching maturity.

Parental Investment: altricial ; pre-fertilization (Provisioning, Protecting: Female); pre-hatching/birth (Provisioning: Female, Protecting: Male, Female); pre-weaning/fledging (Provisioning: Female, Protecting: Male, Female); pre-independence (Provisioning: Female, Protecting: Male, Female); post-independence association with parents; extended period of juvenile learning; inherits maternal/paternal territory; maternal position in the dominance hierarchy affects status of young

The Niger Delta is an enormous classic distributary system located in West Africa, which stretches more than 300 kilometres wide and serves to capture most of the heavy silt load carried by the Niger River. The peak discharge at the mouth is around 21,800 cubic metres per second in mid-October. The Niger Delta coastal region is arguably the wettest place in Africa with an annual rainfall of over 4000 millimetres. Vertebrate species richness is relatively high in the Niger Delta, although vertebrate endemism is quite low. The Niger Delta swamp forests occupy the entire upper coastal delta. Historically the most important timber species of the inner delta was the Abura (Fleroya ledermannii), a Vulnerable swamp-loving West African tree, which has been reduced below populations viable for timber harvesting in the Niger Delta due to recent over-harvesting of this species as well as general habitat destruction of the delta due to the expanding human population here. Other plants prominent in the inner delta flood forest are: the Azobe tree (Lophira alata), the Okhuen tree (Ricinodendron heudelotii ), the Bitter Bark Tree (Sacoglottis gabonensis), the Rough-barked Flat-top Tree (Albizia adianthifolia), and Pycnanthus angolensis. Also present in its native range is the African Oil Palm (Elaeis guineensis)

There are a number of notable mammals present in the upper (or inner) coastal delta in addition to the The Endangered Chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes). The near-endemic White-cheeked Guenon (Cercopithecus erythrogaster, VU) is found in the inner delta. The Critically Endangered Niger Delta Red Colubus (Procolobus pennantii ssp. epieni), which primate is endemic to the Niger Delta is also found in the inner delta. The limited range Black Duiker (Cephalophus niger) is fournd in the inner delta and is a near-endemic to the Niger River Basin. The restricted distribution Mona Monkey (Cercopithecus mona), a primate often associated with rivers, is found here in the Niger Delta. The Near Threatened Olive Colobus (Procolobus verus) is restricted to coastal forests of West Africa and is found here in the upper delta.

Some of the reptiles found in the upper coastal Niger Delta are the African Banded Snake (Chamaelycus fasciatus); the West African Dwarf Crocodile (Osteolaemus tetraspis, VU); the African Slender-snouted Crocodile (Mecistops cataphractus); the Benin Agama (Agama gracilimembris); the Owen's Chameleon (Chamaeleo oweni); the limited range Marsh Snake (Natriciteres fuliginoides); the rather widely distributed Black-line Green Snake (Hapsidophrys lineatus); Cross's Beaked Snake (Rhinotyphlops crossii), an endemic to the Niger Basin as a whole; Morquard's File Snake (Mehelya guirali); the Dull Purple-glossed Snake (Amblyodipsas unicolor); the Rhinoceros Viper (Bitis nasicornis). In addition several of the reptiles found in the outer delta are found within this inner delta area.

Five threatened marine turtle species are found in the mangroves of the lower coastal delta: Leatherback Sea Turtle (Dermochelys coricea, EN), Loggerhead Sea Turtle (Caretta caretta, EN), Olive Ridley Turtle (Lepidochelys olivacea, EN), Hawksbill Sea Turtle (Eretomychelys imbricata, CR), and Green Turtle (Chelonia mydas, EN).

Other reptiles found in the outer NIger Delta are the Nile Crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus), African Softshell Turtle (Trionyx triunguis), African Rock Python (Python sebae), Boomslang Snake (Dispholidus typus), Cabinda Lidless Skink (Panaspis cabindae), Neon Blue Tailed Tree Lizard (Holaspis guentheri), Fischer's Dwarf Gecko (Lygodactylus fischeri), Richardson's Leaf-Toed Gecko (Hemidactylus richardsonii), Spotted Night Adder (Causus maculatus), Tholloni's African Water Snake (Grayia tholloni), Smith's African Water Snake (Grayia smythii), Small-eyed File Snake (Mehelya stenophthalmus), Western Forest File Snake (Mehelya poensis), Western Crowned Snake (Meizodon coronatus), Western Green Snake (Philothamnus irregularis), Variable Green Snake (Philothamnus heterodermus), Slender Burrowing Asp (Atractaspis aterrima), Forest Cobra (Naja melanoleuca), Rough-scaled Bush Viper (Atheris squamigera), and Nile Monitor (Varanus niloticus).

There are a limited number of amphibians in the inner coastal delta including the Marble-legged Frog (Hylarana galamensis). At the extreme eastern edge of the upper delta is a part of the lower Niger and Cross River watersheds that drains the Cross-Sanaka Bioko coastal forests, where the near endemic anuran Cameroon Slippery Frog (Conraua robusta) occurs.

Die sjimpansee (Pan troglodytes) is ’n spesie van mensape. ’n Nabyverwant is die bonobo. Fossiel- en DNA-toetse wys albei spesies is sustersgroepe van die moderne menslike lyn.

Die sjimpansee is bedek met growwe, swart hare, maar het ’n haarlose gesig, vingers, tone, handpalms en voetsole. Dit is sterker gebou as die bonobo; dit weeg tussen 40 en 65 kg en is van kop tot stert sowat 1,3 tot 1,6 m lank. Sjimpansees is agt maande lank dragtig. Babas word op sowat drie jaar gespeen, maar het gewoonlik jare daarna nog ’n sterk verhouding met die ma. Hulle bereik puberteit op sowat 10 jaar en hul lewensverwagting is sowat 50 jaar.

Sjimpansees woon in groepe van 15 tot 150 lede, hoewel individue bedags in veel kleiner groepe rondbeweeg. Die spesie word deur die manlike diere oorheers en lewe volgens ’n streng hiërargie, wat beteken verskille kan gewoonlik sonder geweld opgelos word. Byna alle sjimpanseebevolkings gebruik gereedskap, aangepaste stokke, klippe, gras en blare om heuning, termiete, miere, neute en water bymekaar te maak.

Die sjimpansee is op die Internasionale Unie vir die Bewaring van die Natuur (IUBN) se lys van bedreigde spesies. Daar is na raming tussen 170 000 en 300 000 sjimpansees oor in die woude en grasvelde van Wes- en Sentraal-Afrika. Hul grootste bedreiging is die vernietiging van hul habitat, wilddiefstal en siektes.

Die spesienaam troglodytes (Grieks vir "grotbewoner") is deur Johann Friedrich Blumenbach gebruik in sy boek De generis humani varietate nativa liber, wat in 1776 gepubliseer is.[2][3] Die boek is gebaseer op sy verhandeling ’n jaar voor die publikasiedatum slegs vir interne gebruik aan die Universiteit van Göttingen,[4] en die verhandeling self het dus nie voldoen aan die voorwaardes vir gepubliseerde werke met betrekking tot dierkundige naamgewing nie.[5]

Ondanks ’n groot aantal vondste van Homo-fossiele, is sjimpanseefossiele in 2005 vir die eerste keer beskryf. Bestaande sjimpanseebevolkings in Wes- en Sentraal-Afrika oorvleuel nie met die groot fossielvondste van mense in Oos-Afrika nie. Daar is egter nou sjimpanseefossiele uit Kenia aangeteken. Dit sou beteken mense sowel as lede van die Pan-klade het tydens die Middel-Pleistoseen in die vallei van die Groot Skeurvallei voorgekom.

John Gribbin en Jeremy Cherfas meen in hul boeke The Monkey Puzzle: Reshaping the Evolutionary Tree en The First Chimpanzee: In Search of Human Origins sjimpansees en bonobo's kan van Australopithecus afstam.

Volgens DNS-bewyse het die sjimpansee en bonobo moontlik minder as ’n miljoen jaar gelede van mekaar geskei (nes Homo sapiens en die Neanderdallers).[6][7] Die sjimpanseelyn het sowat 6 miljoen jaar gelede van die laaste gemeenskaplike voorouer van die menslike lyn geskei. Omdat geen spesie behalwe Homo sapiens van die menslike lyn oorleef het nie, is die twee sjimpanseespesies die mens se naaste verwante. Die sjimpanseegenus, Pan, het sowat 7 miljoen jaar gelede van die gorillas se genus afgeskei.

Vier subspesies van die sjimpansee word erken,[8][9] met die moontlikheid van ’n vyfde:[10]

Die manlike volwasse sjimpansee weeg tussen 40 en 60 kg en die wyfie tussen 32 en 47 kg.[11] Groot, wilde mannetjies kan egter tot 70 kg weeg en mannetjies in aanhouding het al tot 91 kg gehaal.[12][13][14] Die lengte van die neus tot die agterlyf wissel van 63 tot 94 cm.[14][15] Manntjies wat staan, kan tot 1,6 m lank wees en wyfies tot 1,3 m. Hul lywe is bedek met growwe, swart hare, behalwe die gesig, vingers, tone, handpalms en voetsole. Hul spiere is "tot vyf keer digter as mense s’n. So dig dat hulle nie kan swem nie."[16]

Sjimpansees kom in bome (snags) en op die grond (bedags) voor.[17] Hulle loop of staan gewoonlik op al vier pote, maar kan vir kort entjies op twee pote loop. Hulle loop op hul kneukels, nes gorillas en bonobos,[17] teenoor die orangoetang, wat op die buitekant van sy palms loop.

Sjimpansees is hoogs aanpasbaar. Hulle woon in ’n verskeidenheid habitats, onder meer droë grasvelde, immergroen reënwoude en moeraswoude.[18][19] Hulle het ’n goeie geheue wat hul tuiste aanbetref. Hulle maak elke aand ’n slaapplek in ’n nuwe boom en slaap apart, behalwe die baba- of jong sjimpansees, wat by hul ma slaap.[20] Wanneer hulle ’n indringer gewaar, sal hulle hard skree en enige voorwerp moontlik gebruik om hulle te verdedig.

Luiperds is ’n groot bedreiging en gevalle is aangemeld waar sjimpansees luiperdwelpies doodmaak,[21] blykbaar hoofsaaklik as ’n beskermingsmetode.

Sjimpansees verkies vrugte bo enige ander kos en sal dit selfs gaan soek as dit nie volop is nie. Hulle sal ook blare eet. Sade, bloeisels, boombas en gom maak die res van hul plantdieet uit.[19][22] Hoewel hulle hoofsaaklik planteters is,[23][24] eet hulle ook heuning, grond, insekte, voëls en hul eiers en klein tot mediumgrootte soogdiere, insluitende ander primate.[19][25] Soogdiere wat hulle eet, sluit in sekere soorte ape, bobbejane, blouduikers, bosbokke en vlakvarke.[26]

Sjimpansees jag soms alleen, en soms in groepe sodat hulle hul prooi makliker kan vaskeer.[27] As hulle saam in bome jag, het elke sjimpansee ’n rol. Sommige sorg dat die prooi in ’n sekere rigting hardloop en jaag hulle sonder om hulle te probeer vang. Ander sal onder bome staan en opklim om te keer dat die prooi in ’n ander rigting hardloop. Dan is daar dié wat vinnig beweeg en die prooi probeer vang, en dié wat wegkruip en die prooi vang as hulle nader kom.[27] Hulle sal sowel volwassenes as kleintjies vang. Hulle is egter bang vir sekere soorte ape en sal die kleintjies probeer gryp sonder om die ma aan te val.[19] Die mannetjies jag meer as die wyfies. Wanneer die prooi gevang is, sal dit verdeel word onder almal wat gejag het, en selfs onder die omstanders.[27]

Sjimpansees woon in gemeenskappe van gewoonlik tussen 15 en meer as 150 lede, maar loop meestal rond in kleiner, tydelike groepe van ’n paar individue – dié kan voorkom in enige kombinasie van ouderdom en geslag.[20] Beide mans en wyfies kan ook alleen rondloop.[20] Hulle het ingewikkelde sosiale verhoudings en bestee baie tyd daaraan om mekaar te versorg (groom).[28]

Mannetjies vorm die kern van die sosiale struktuur. Hulle loop rond, beskerm groeplede en soek kos. Hulle bly in die gemeenskappe waarin hulle gebore is, maar wyfies kan na ander groepe oorloop as hulle volgroei is. Daarom is mannetjies in ’n groep meer geneig om aan mekaar verwant te wees as aan die wyfies. Onder die mannetjies is daar gewoonlik ’n dominansie-hiërargie en hulle oorheers ook die wyfies.[29] Groepe of individue wyk ook gereeld van die groter gemeenskap af en sluit dan weer later by hulle aan.[19] Dié kleiner groepe kan in ’n verskeidenheid vorme voorkom, om verskeie redes. ’n Groep mannetjies kan byvoorbeeld bymekaarkom om te jag, terwyl ’n groep wyfies saam ’n paar kleintjies kan grootmaak.[30] ’n Individuele sjimpansee sal ander gereeld raakloop, maar feitlik nooit baklei nie – hulle baklei net in groot groepe.

Omdat groepe en individue voortdurend kom en gaan, is die struktuur van die gemeenskap baie ingewikkeld. ’n Mannetjie kan byvoorbeeld ná ’n tyd terugkeer en onseker wees of daar enige "politieke skuiwe" tydens sy afwesigheid plaasgevind het; dan sal hy sy heerskappy probeer hervestig. ’n Groot mate van aggressie vind dus plaas binne die eerste vyf tot vyftien minute nadat ’n mannetjie weer by die gemeenskap aangesluit het.[31][32]

Mannetjies behou en verbeter hul sosiale rang deur koalisies te vorm. Dié is gebaseer op ’n sjimpansee se invloed in vyandige interaksies.[33] As twee sjimpansees in ’n koalisie is, kan hulle ’n derde sjimpansee oorheers wat hulle nie op hul eie sou kon nie, want sjimpansees wat hul hand goed speel, kan mag in aggressiewe interaksies uitoefen ongeag hul rang. Hoe meer bondgenote ’n sjimpansee het, hoe ’n beter kans het hy om ’n oorheersende rol te spel. Mannetjies in ’n koalisie kan egter ook teen mekaar draai as dit hulle pas.[34]

Manntjies met ’n lae rang verander dikwels van kant in geskille tussen meer dominante sjimpansees. Hulle kan voordeel trek uit ’n onstabiele hiërargie en meer seksuele geleenthede kry.[33][34] Verder konsentreer dominante mannetjies op mekaar tydens ’n konflik in plaas van op dié met ’n laer rang. Die hiërargie tusen wyfies is swakker, maar ’n klein sjimpansee kan voordeel trek uit sy ma se status.[35] Sosiale versorging blyk ook belangrik te wees in die instandhouding van koalisies,[36] veral tussen mannetjies.

Sjimpansees paar regdeur die jaar, hoewel die aantal wyfies wat bronstig is, van seisoen tot seisoen in ’n groep wissel.[37][38] Hulle is meer geneig om bronstig te wees as kos volop is. Paring tussen sjimpansees is promisku – ’n wyfie kan met verskeie mannetjies in die groep paar terwyl sy bronstig is.[19] Die patrone wissel egter. Soms beperk dominante mannetjies toegang tot wyfies. ’n Mannetjie en wyfie kan ook buite hul gemeenskap paar – soms verlaat wyfies die groep om met ’n mannetjie van ’n ander groep te paar.[19][39]

Dis gewoonlik die ma wat ’n kleintjie versorg. Die oorlewing en emosionele gesondheid van ’n kleintjie hang van moederlike sorg af.[19] Die ma gee die kleintjie kos, hitte en beskerming en leer hulle sekere vaardighede. ’n Kleintjie se toekomstige rang in die gemeenskap kan ook afhang van die ma se status.[19][37] Vir die eerste 30 dae klou ’n kleintjie aan die ma se maag vas. Wanneer hulle vyf tot ses maande oud is, ry hulle op die ma se rug. Hulle het permanente kontak vir die eerste jaar. Wanneer hulle twee jaar oud is, kan hulle self rondbeweeg en sit.[40] Teen hul derde jaar sal kleintjies begin wegbeweeg van die ma af. Hulle word gespeen op tussen vier en ses jaar.[40]

Tussen hul sesde tot negende jaar sal die jong sjimpansee naby sy ma bly, maar ook meer interaksies met ander lede van die gemeenskap hê. Jong wyfies beweeg tussen groepe en word deur die ma bygestaan in vyandige situasies. Jong mannetjies bring tyd saam met die ouer mannetjies deur en sal saam met hulle jag of die gebied patrolleer.[40]

Sjimpansees gebruik ’n verskeidenheid gesigsuitdrukkings, houdings en klanke om met mekaar te kommunikeer.[19] Hulle kan grynslag, pruil en hul lippe teen mekaar druk.[19] ’n Aggressiewe mannetjie sal op twee voete staan en sy arms swaai om hom groter te laat lyk.[19] Soms stamp sjimpansees hul hande en voete teen ’n groot boomstam.[41]

As hulle opgewonde is, sal hulle sagte "hoe"-geluide maak, wat al hoe harder word tot dit ’n skree of soms blaf word. Dié sal dan weer sagter word en eindig in nog sagte "hoe"-geluide.[41] Hulle sal uitroep as hulle ander teen gevaar waarsku of kos sien.[19] Kort blafgeluide word ook gemaak wanneer hulle jag.[41]

Die gebruik van gereedskap is al in feitlik alle sjimpanseegemeenskappe waargeneem. Hulle sal stokke, rotse, gras en blare aanpas en dit gebruik om heuning, miere, neute en water te soek. Al is die gereedskap nie ingewikkeld nie, verg dit tog vaardigheid en lyk dit of vooraf daaroor gedink is.[42] Volgens die resultate van ’n ondersoek wat in 2007 gepubliseer is, lyk dit of die gebruik van gereedskap deur sjimpansees uit minstens 4 300 jaar gelede dateer.[43]

’n Sjimpansee in Tanzanië was die eerste nie-menslike dier wat waargeneem is terwyl hy ’n stuk gereedskap maak – ’n tak wat hy aangepas het om miere uit ’n miershoop te krap.[44][45][46] Wanneer hulle heuning kry, sal sjimpansees aangepaste, kort stokke gebruik om die heuning uit die bynes te skep as die bye hulle nie steek nie. As die bye gevaarliker is, sal hulle langer, dunner stokke gebruik.[47] Hulle sal op dieselfde manier miere uit miershope grawe.[19][42]

Sommige sjimpansees sal harde neute met klippe of takke kraak.[37][42] Daar is ’n vorm van voorbedagde rade, want die klippe en takke word nie aangetref op plekke naby neute nie. Om neute te kraak is ’n vaardigheid wat aangeleer moet word.[37] Sjimpansees sal ook blare gebruik om water mee te skep.[48]

In ’n onlangse studie is die gebruik van spiese selfs waargeneem wat sjimpansees in Senegal met hul tande skerp maak. Daarmee gooi hulle klein bosape uit gate in bome.[49]

Die Britse primatoloog Jane Goodall het die eerste langtermyn-veldstudie van sjimpansees gedoen. Dit het in 1960 in die Nasionale Park Gombe Stream in Tanzanië begin en 50 jaar geduur. Die kennis oor die spesie se tipiese gedrag en sosiale strukture is in ’n groot mate danksy Goodall se navorsing.[50]

Die mens en die sjimpansee is baie eenders. In Desember 2003 het ’n voorlopige ontleding van 7 600 gene wat die twee spesies deel, gewys sekere gene wat met spraakontwikkeling verband hou, het ’n vinnige evolusie in die menslike lyn ondergaan. ’n Voorlopige weergawe van die sjimpansee-genoom is op 1 September 2005 gepubliseer in ’n artikel deur ’n groep wetenskaplikes.[51]

Daar is baie min verskille tussen die mens en sjimpansee se DNA. Die duplisering van klein dele van chromosome was die grootste bron van verskille tussen die spesies se genetiese materiaal. Sowat 2,7% van die ooreenstemmende moderne genome verteenwoordig verskille, wat ontstaan het deur die duplisering of weglating van gene in die sowat 4 miljoen tot 6 miljoen jaar sedert die mens en die sjimpansee afgeskei het van hul gemeenskaplike voorouer.

Dit het al gebeur dat sjimpansees mense aanval.[52][53] Die gevare wat onverskillige menslike optrede teenoor sjimpansees inhou, word vererger deur die feit dat baie sjimpansees mense as moontlike mededingers beskou.[54]

Omdat ’n sjimpansee soveel sterker is, is dit vir hom maklik om ’n mens dood te maak as hy kwaad is, soos blyk uit ’n paar aangetekende voorvalle.[55][56][57][58] Daar is minstens ses aangetekende gevalle van sjimpansees wat menslike babas gegryp en geëet het.[59]

Twee tipes MI-virusse word in mense aangetref: HIV-1 en HIV-2. Eersgenoemde kom die meeste voor en word die maklikste oorgedra; HIV-2 is grootliks beperk tot Wes-Afrika.[60] Albei tipes het in Wes- en Sentraal-Afrika ontstaan – oorgedra van ape na mense. HIV-1 het ontwikkel uit ’n aap-immuniteitsgebreksvirus (SIVcpz) wat in die sjimpansee-subspesie Pan troglodytes troglodytes voorkom; hulle is inheems aan Suid-Kameroen.[61][62] Kinshasa, in die Demokratiese Republiek van die Kongo, het die grootste genetiese verskeidenheid van HIV-1 wat nog ontdek is, wat daarop dui dat die virus daar langer kan bestaan as op enige ander plek. HIV-2 is van ’n ander stam van die aap-immuniteitsgebreksvirus na die mens oorgedra – dit word in die roetmangabie van Guinee-Bissau aangetref.[60]

Sjimpansees word in die meeste wêrelddele waar hulle voorkom, deur die wet beskerm en word in en buite nasionale parke aangetref.[1] Daar is vermoedelik tussen 172 700 en 299 700 van hulle in die natuur oor.[1]

Hul grootste bedreiging is die vernietiging van hul habitat, wilddiefstal en siektes.[1] Hul habitats het kleiner geword weens ontbossing in beide Wes- en Sentraal-Afrika. Die bou van paaie het hul habitat verdeel en dit toegankliker gemaak vir wilddiewe.[1]

Sjimpansees word algemeen deur wilddiewe geteiken. In die Ivoorkus maak sjimpansees 1–3% uit van wilde diere se vleis wat op plaaslike markte verkoop word.[1] Hulle word ook gevang en as troeteldiere verkoop ondanks ’n verbod daarop in die meeste lande waarin hulle voorkom.[1] Verder word hulle in sommige gebiede vir medisyne gejag.[1] Om sjimpansees te vang vir wetenskaplike navorsing is steeds wettig in sommige lande soos Guinee.[1] Mense sal ook enige sjimpansee doodmaak wat hul oeste bedreig[1] en hulle beland per ongeluk in strikke wat vir ander diere bedoel is.

Aansteeklike siektes is die hoofoorsaak van dood onder sjimpansees. Hulle kry baie siektes wat mense ook bedreig aangesien die spesies so ooreenstem.[1] Namate menslike bevolkings toeneem, vergroot die gevaar dat siektes van die mens aan die sjimpansee oorgedra kan word.[1]

|publisher= (help) |work= (help) Die sjimpansee (Pan troglodytes) is ’n spesie van mensape. ’n Nabyverwant is die bonobo. Fossiel- en DNA-toetse wys albei spesies is sustersgroepe van die moderne menslike lyn.

Die sjimpansee is bedek met growwe, swart hare, maar het ’n haarlose gesig, vingers, tone, handpalms en voetsole. Dit is sterker gebou as die bonobo; dit weeg tussen 40 en 65 kg en is van kop tot stert sowat 1,3 tot 1,6 m lank. Sjimpansees is agt maande lank dragtig. Babas word op sowat drie jaar gespeen, maar het gewoonlik jare daarna nog ’n sterk verhouding met die ma. Hulle bereik puberteit op sowat 10 jaar en hul lewensverwagting is sowat 50 jaar.

Sjimpansees woon in groepe van 15 tot 150 lede, hoewel individue bedags in veel kleiner groepe rondbeweeg. Die spesie word deur die manlike diere oorheers en lewe volgens ’n streng hiërargie, wat beteken verskille kan gewoonlik sonder geweld opgelos word. Byna alle sjimpanseebevolkings gebruik gereedskap, aangepaste stokke, klippe, gras en blare om heuning, termiete, miere, neute en water bymekaar te maak.

Die sjimpansee is op die Internasionale Unie vir die Bewaring van die Natuur (IUBN) se lys van bedreigde spesies. Daar is na raming tussen 170 000 en 300 000 sjimpansees oor in die woude en grasvelde van Wes- en Sentraal-Afrika. Hul grootste bedreiging is die vernietiging van hul habitat, wilddiefstal en siektes.

Ar chimpanze boutin (Pan troglodytes), anvet ivez chimpanze hepken alies p’eo ar spesad chimpanzeed boutinañ, a zo ur "marmouz meur" rummataet e kerentiad an Hominidae. Eus ar memes genad hag ar bonobo eo, nemet ez eo brasoc'h ha postekoc'h. Bevañ a ra en Afrika. Hervez an DNA ez eo al loen tostañ d'an den. Ul loen en arvar ez eo.

Pevar isspesad a zo da vihanañ:

a vo kavet e Wikimedia Commons.

Ar chimpanze boutin (Pan troglodytes), anvet ivez chimpanze hepken alies p’eo ar spesad chimpanzeed boutinañ, a zo ur "marmouz meur" rummataet e kerentiad an Hominidae. Eus ar memes genad hag ar bonobo eo, nemet ez eo brasoc'h ha postekoc'h. Bevañ a ra en Afrika. Hervez an DNA ez eo al loen tostañ d'an den. Ul loen en arvar ez eo.

El ximpanzé comú (Pan troglodytes) és una espècie de primat de la família dels homínids pròpia de l'Àfrica tropical. Els ximpanzés —al costat dels bonobos— són els parents vius més propers a l'ésser humà; la seva branca evolutiva es va separar de la branca dels humans fa aproximadament 7 milions d'anys i comparteixen el 96% de l'ADN amb ells,[1] el que ha portat a Jared Diamond a utilitzar el terme "el tercer ximpanzé" per referir-se a la nostra pròpia espècie. Els mascles arriben a pesar uns 80 kg en captivitat i a mesurar fins a 1,7 m. Es caracteritza per la seva intel·ligència avançada sovint comparada a la dels éssers humans. Per exemple, s'ha observat que els ximpanzés joves es construeixen "ninots" i altres joguines amb pals i bastons.[2]

Actualment està en perill d'extinció a causa de la desforestació del seu hàbitat natural.

Podem trobar ximpanzés a les selves tropicals i a les sabanes humides de l'Àfrica central i occidental. Solien habitar la major part d'aquesta regió, però el seu hàbitat ha estat dràsticament reduït en els últims anys per la desforestació.

En posició erecta els adults mesuren entre 1 m i 1,7 m d'alçada. Els mascles en llibertat pesen entre 34 i 70 kg, mentre les femelles pesen entre 26 i 50 kg. En captivitat els mascles poden pesar fins a 80 kg i les femelles fins a 68 kg. Aparentment P. t. schweinfurthii pesa menys que P. t. verus, el qual és més petit que P. t. troglodytes. Els braços dels ximpanzés són molt més llargs que les seves cames. L'envergadura dels seus braços és d'aproximadament 1,5 vegades l'alçada de l'individu. Els braços llargs li permeten a aquests primats balancejar-se passant de branca en branca, aquesta modalitat de locomoció es denomina braquiació. També posseeixen dits i mans llargues, però el polze és curt. Això els permet sostenir-se de les branques sense interferir amb la mobilitat dels polzes.[3]

Els ximpanzés tenen una capacitat cranial de 320 a 480 centímetres cúbics, molt inferior a la dels humans moderns (Homo sapiens) que té de mitjana 1400 centímetres cúbics.

Tenen el cos cobert per un pelatge gruixut de color marró fosc, amb excepció del rostre, dits, palmells de la mà i plantes del peu. Tant els seus polzes com el dit gran del peu són oposables, permetent una agafada precisa. La gestació del ximpanzé dura vuit mesos. Les cries són deslletades aproximadament a l'edat de tres anys, però generalment mantenen una relació propera amb la seva mare diversos anys més. La pubertat és aconseguida a l'edat de vuit a deu anys i la seva esperança de vida és de 50 anys en captivitat.

La seva alimentació és principalment vegetariana (fruites, fulles, nous, arrels, tubercles, etc.), complementada per insectes i petites preses; existeixen instàncies de caceres organitzades. En alguns casos —com la matança de cadells de lleopard— aquesta cacera sembla ser un esforç de protecció dels ximpanzés, més que una motivació per la gana. Existeixen casos documentats de canibalisme, encara que és poc comú.

Els ximpanzés viuen en grups anomenats comunitats que oscil·len entre els 20 i més de 150 membres, consistint de diversos mascles, femelles i joves. No obstant això, la major part del temps es desplacen en petits grups d'uns pocs individus. Els ximpanzés són tant arboris com terrestres, passant la mateixa quantitat de temps sobre els arbres que sobre el terra. La seva manera de desplaçament habitual és de quatre grapes, utilitzant les plantes dels peus i les segones falanges dels dits de les mans, i poden caminar en posició bípeda únicament per distàncies curtes.

El ximpanzé comú viu en societats de fissió-fusió (en primatologia, una organització de fissió-fusió és aquella en què la composició canvia dia a dia, separant-se durant períodes de temps més o menys perllongats; per exemple, els individus dormen junts en un lloc, però busquen aliment en petits grups que es desplacen en diferents adreces durant el dia).[4] on l'aparellament és promiscu. Els ximpanzés poden tenir els següents grups: només mascles, femelles adultes i la seva descendència, grups amb membres de tots dos sexes, una femella i la seva descendència, o individus solitaris. En el centre de l'estructura social es troben els mascles, els qui patrullen i cuiden als membres del seu grup, i participen en la cerca d'aliment. Entre els mascles usualment hi ha una jerarquia de domini. No obstant això, la inusual estructura social de fissió-fusió, en la qual porcions del grup parental pot separar-se o tornar-se a unir a ell, és altament variable en termes de quins individus particulars es congreguen en un moment donat. Això es deu principalment al fet que els ximpanzés tenen un alt nivell d'autonomia dins de la fissió-fusió dels grups als quals pertanyen. També les comunitats de ximpanzés tenen grans rangs de territori que se solapen amb els dels altres grups.

Com a resultat, individus ximpanzés amb freqüència van sols en la cerca d'aliments, o en grups petits. Com s'indicava, aquests petits grups també emergeixen en una gran varietat de tipus per a una gran varietat de propòsits. Per exemple, una petita tropa de mascles pot organitzar-se per caçar i obtenir carn, mentre que un grup consistent d'un mascle madur i una femella madura poden establir-se com a grup amb el propòsit de copular. Un individu pot trobar-se amb altres individus amb certa freqüència però poden haver-hi baralles amb altres individus no freqüentats. A causa de la varietat freqüent de la forma com els ximpanzés s'associen, l'estructura de les seves societats és molt complicada.

Durant el segle XX s'han fet diversos treballs tendents a establir una taxonomia clara del ximpanzé. Va ser el zoòleg alemany Ernst Schwarz qui va descriure la majoria de les subespècies actualment acceptades, després de centenars de mesuraments d'esquelets i anàlisis de les pells portades als museus. Schwartz, qui va descriure el bonobo, el va considerar com una subespècie de Pan troglodytes i no com una espècie a part. Aquest autor va establir les subespècies de Pan troglodytes de la següent manera:

Recent evidència provinent de les anàlisis d'ADN suggereixen que el bonobo (Pan paniscus) i el ximpanzé comú se separaren fa un milió d'anys aproximadament. La línia del ximpanzé es va separar del llinatge que va desembocar en els humans aproximadament fa sis milions d'anys. Les dues espècies de ximpanzés estan igualment relacionades amb els éssers humans i atès que no han sobreviscut cap altra espècie dels gèneres Homo, Australopithecus o Paranthropus, són els seus parents vius més propers. El bonobo no fou reconegut com una espècie independent fins al 1929, i en l'idioma comú la designació "ximpanzé" sovint s'aplica a tots dos simis. Els primatòlegs prefereixen reservar el nom "ximpanzé" per a Pan troglodytes. Encara que les diferències anatòmiques entre ambdues espècies són petites, el seu comportament tant sexual com social mostren diferències marcades. Pan troglodytes posseeix un comportament de caça grupal basat en mascles beta liderats per mascles alfa relativament febles, una dieta omnívora i una cultura complexa amb forts llaços.

El ximpanzé comú (Pan troglodytes) és una espècie de primat de la família dels homínids pròpia de l'Àfrica tropical. Els ximpanzés —al costat dels bonobos— són els parents vius més propers a l'ésser humà; la seva branca evolutiva es va separar de la branca dels humans fa aproximadament 7 milions d'anys i comparteixen el 96% de l'ADN amb ells, el que ha portat a Jared Diamond a utilitzar el terme "el tercer ximpanzé" per referir-se a la nostra pròpia espècie. Els mascles arriben a pesar uns 80 kg en captivitat i a mesurar fins a 1,7 m. Es caracteritza per la seva intel·ligència avançada sovint comparada a la dels éssers humans. Per exemple, s'ha observat que els ximpanzés joves es construeixen "ninots" i altres joguines amb pals i bastons.

Actualment està en perill d'extinció a causa de la desforestació del seu hàbitat natural.

Šimpanz učenlivý (Pan troglodytes) je africký lidoop. Společně s bonobem je nejbližším žijícím příbuzným člověka a je mu ze všech primátů nejpodobnější. Nejbližším příbuzným šimpanze učenlivého je bonobo, s nímž tvoří společný rod Pan. Odhaduje se, že oba druhy se oddělily zhruba před 0,8-1,8 miliony let. Srst má tmavou, lysé části těla bývají u některých poddruhů světlé. Dorůstá obvykle délky 65 až 95 cm a hmotnosti od 32 do 70 kg. Přestože se převážně živí rostlinnou stravou, doplňuje svůj jídelníček o termity, mravence a jiný hmyz. V některých oblastech tvoří část jeho jídelníčku i maso získané lovem (malé antilopy, guerézy, kočkodani a mláďata paviánů). Samice je březí osm měsíců, rodí jediné mládě. Pohlavně dospělý je po 6–10 letech života.

Šimpanz učenlivý je intenzivně zkoumaným druhem, velmi zajímavé jsou např. kulturní odlišnosti jednotlivých tlup.

Šimpanz učenlivý je rozšířen v rovníkové Africe ve čtyřech poddruzích. Šimpanz učenlivý je nejbližším zvířecím příbuzným člověka. Obývá tropické deštné pralesy, husté stromové savany a křovinatou krajinu. Dokonce žije i v galeriových a horských lesích do výšky 3 000 metrů nad mořem.

I když jich žije ve své domovině zatím poměrně dost, jejich počet radikálně klesá a odhaduje se v divočině západní a východní Afriky již jen na 100 000 jedinců. Hlavním důvodem je, že je narušováno jejich přirozené prostředí.

Šimpanzi jsou zajímaví tím, že pokud se potkají dva – vítají se skoro lidským způsobem. A pokud se osobně znají, dokáží se dokonce políbit, poplácat po zádech či si dokonce podají i ruce. Dokáží si vyrobit i jednoduché nástroje, ale nikdy si je neuchovávají, protože si pokaždé vyrobí nové.

V zoologických zahradách se dožívají šimpanzi vysokého věku. Není výjimkou i dožití se skoro 50 let. Dlouho se tradovalo, že se bojí vody, ale dokáží si na ni časem zvyknout. Velmi rádi si vzájemně pečují o svou srst a díky tomu se zlepšuje i jejich případná nervozita.