pms

nòm ant ël fil

Foraminifera is ’n filum of klas amebiese protiste. Hulle het uitsteeksels wat ’n net vorm om kos te vang en het gewoonlik ’n eksterne dop wat uit verskeie soorte materiaal bestaan en verskeie vorms het. Die meeste organismes in dié klas kom in die water voor, veral die see. Die meeste leef op die seebodem, maar daar is ook spesies wat in verskillende dieptes water voorkom (plankton). Daar is ook al soorte op land ontdek.[1][2]

Foraminifera is ’n filum of klas amebiese protiste. Hulle het uitsteeksels wat ’n net vorm om kos te vang en het gewoonlik ’n eksterne dop wat uit verskeie soorte materiaal bestaan en verskeie vorms het. Die meeste organismes in dié klas kom in die water voor, veral die see. Die meeste leef op die seebodem, maar daar is ook spesies wat in verskillende dieptes water voorkom (plankton). Daar is ook al soorte op land ontdek.

Els foraminífers (Foraminifera) són un subfílum de protozous rizaris que segreguen una closca de carbonat de calci dins la qual viu l'animal, constituït per una sola cèl·lula que emet pseudopodis. L'esquelet, extern, acostuma a estar enrotllat i dividit internament mitjançant envans o septes en cambres que es comuniquen. Es coneixen més de 200.000 espècies que formen 220 famílies[1] i hi ha formes actuals i formes que es coneixen exclusivament a través dels fòssils. La mida dels foraminífers va de pocs micròmetres a més de 10 cm. Les formes petites s'anomenen microforaminífers i les grans macroforaminífers, essent aquests darrers característics de sediments carbonatats d'aigües poc profundes.

El subfílum Foraminifera forma, juntament amb el subfílum Radiozoa, el fílum Retaria, segons la classificació de 2003 de Thomas Cavalier-Smith.[2]

Els foraminífers tenen un gran interès en estudis bioestratigràfics i s'utilitzen per a la datació de sediments i també com a indicadors paleoecològics.

La cèl·lula que constitueix un macroforaminífer és excepcional per les seves mides i la seva complexitat. Són dels pocs grups d'éssers unicel·lulars que segreguen una closca mineralitzada que protegeix el protoplasma que inclou els orgànuls propis de les cèl·lules eucariotes i un o diversos nuclis. És possible la regeneració de l'organisme sempre que al fragment de protoplasma hi hagi un nucli.[1]

El protoplasma s'estén per l'exterior en forma de pseudopodis, fines expansions que surten a través d'un o diversos orificis i que es ramifiquen i s'anastomosen entre si tot formant una xarxa fina. L'organisme els utilitza tant per a la locomoció i l'ancorament al substrat com per a la captura de preses. Els pseudopodis dels foraminífers, al contrari dels d'altres protozous, són estructures més o menys permanents i el citoplasma que contenen té un aspecte granulat, amb grànuls que avancen en ambdós sentits en un moviment en el qual estan implicades molècules contràctils.[3]

L'element bàsic per a diferenciar els foraminífers, l'únic en el cas de les formes fòssils, és la closca. Segons el nombre de cambres que la formen es poden diferenciar:

Les cambres són limitades per una paret mineralitzada; la part interna de la cambra s'anomena lumen. Segons el tipus de paret es poden distingir:[1]

Les cambres se situen en línia, una darrere l'altra, a partir d'una cambra inicial anomenada prolòculus. Segons l'eix al llarg del qual es van disposant les cambres successives hi ha closques:[4]

És freqüent, però, trobar arranjaments combinats i fins i tot foraminífers que tenen dos tipus diferents de cambres: les que es formen a partir de l'embrió, anomenades cambres equatorials, i les que es formen a partir d'aquestes cambres equatorials, anomenades cambres laterals, i que tenen una disposició diferent.

El cicle biològic dels foraminífers, tot i ser variable segons les espècies, inclou una alternança entre formes haploides i formes diploides. En un cicle típic la forma haploide o gamont té, inicialment, un únic nucli que es divideix per a produir nombroses gàmetes, en general biflagel·lades. La unió d'aquestes gàmetes origina un zigot que creix fins a convertir-se en un agamont o esquizont, que correspon a la forma diploide. L'agamont té al principi un únic nucli però al llarg de la seva vida s'anirà dividint per mitosi de manera que en arribar a la maduresa l'organisme serà plurinucleat. Llavors cada nucli pateix una divisió meiòtica i per un procés d'esquizogònia l'organisme es disgrega en multitud de petits embrions haploides que creixeran fins a formar els gamonts. Els gamonts i els agamonts o esquizonts són semblants però els primers són uninucleats i haploides i presenten dimorfisme en les dimensions i disposició de les cambres.

Les formes actuals són principalment marines, en general estenohalins tot i que algunes espècies sobreviuen en aigua dolça; fins i tot s'ha descrit una espècie que viu al sòl de la selva plujosa.

Els macroforaminífers són bentònics i viuen sobre el fons marí o bé com a epífits, sobre plantes i algues, especialment a aigües poc fondes. Als moderns esculls de corall constitueixen més del 15% de les restes esquelètiques i en èpoques passades eren, sovint, els principals components orgànics de les roques.[1] La taxa estimada de carbonat de calci fixat pels foraminífers als esculls de corall és d'uns 43 milions de tones anuals, de manera que juguen un paper essencial en la producció d'aquests esculls.[5]

Els foraminífers planctònics presenten una diversitat molt menor a la dels bentònics: només es coneixen unes 40 espècies actuals i estan també menys representats al registre fòssil. Són típicament estenohalins (salinitat entre 34 i 36‰) i solen ocupar la zona fòtica, amb una profunditat límit de 200 m tot i que la major part de les espècies sol viure fins als 50 m.

El subfílum Foraminifera està subdividit en quatre classes:

Els foraminífers són coneguts des de l'antiguitat clàssica. Els romans, en trobar els nummulits a les pedres de les grans piràmides d'Egipte els van interpretar com a "llenties petrificades" que haurien servit d'aliment als esclaus que les van construir. L'estudi dels foraminífers va començar al segle XVII, amb l'invent de les lents d'augment i els primers microscopis i es va perfeccionar al llarg dels segles XVIII i XIX amb contribucions de naturalistes com Linné, Monfort, Waldheim i Lamarck. El 1835 Dujardin els reconeix com a protozous. La primera classificació la va fer el que es pot considerar "pare" del seu estudi i també de la micropaleontologia, el naturalista francès Alcide d'Orbigny que a la primera meitat del segle XIX en va arribar a identificar 1.500 espècies.

Al llarg del segle XX l'impuls de l'estudi dels foraminífers està lligat a l'exploració de jaciments de petroli. El 1923 es funda als Estats Units d'Amèrica el Cushman Laboratory for Foramminiferal Research i dos anys després, també als Estats Units, apareix la primera revista científica periòdica dedicada exclusivament als foraminífers, el Journal of Foraminiferal Research. Als anys seixanta el microspopi electrònic d'escandallatge va donar un nou estímul a l'estudi dels foraminífers.

L'aplicació de l'estudi dels foraminífers fòssils a la biocronostratigrafia, datació dels estrats de roques a partir de restes biològiques, va començar a finals del segle XVIII. Des de llavors, els foraminífers han esdevingut peces clau en la datació de roques i també en estudis de paleoecologia. Els foraminífers fòssils més freqüents a Catalunya permeten datar roques que van des del Cretaci inferior fins a l'Oligocè.

Els foraminífers com a fòssils estratigràfics[6] Grup de foraminífers Època Nummulites Oligocè - Paleocè/Eocè Alveolina Paleocè/Eocè Assilina Paleocè/Eocè Orbitoides Cretaci superior Lacazina Paleocè/Eocè i Cretaci superior Orbitolina final del Cretaci superior i Cretaci inferiorLa gran abundància de Nummulítids al Paleogen d'Europa va fer que al segle XIX s'anomenés aquesta època el Nummulític. La gran abundància de macroforaminífers a aquesta època ha permès establir escales biocronoestratigràfiques molt detallades. La calcària nummulítica que es va originar als mars eocens d'un sector de l'antic oceà mesozoic de Tethys és també anomenada pedra de Girona. Alguns dels afloraments més importants es troben als cingles de Tavertet i del Far, sobre la població d'Amer. Amb aquesta roca s'han construït edificis singulars com la catedral de Girona.

Els foraminífers (Foraminifera) són un subfílum de protozous rizaris que segreguen una closca de carbonat de calci dins la qual viu l'animal, constituït per una sola cèl·lula que emet pseudopodis. L'esquelet, extern, acostuma a estar enrotllat i dividit internament mitjançant envans o septes en cambres que es comuniquen. Es coneixen més de 200.000 espècies que formen 220 famílies i hi ha formes actuals i formes que es coneixen exclusivament a través dels fòssils. La mida dels foraminífers va de pocs micròmetres a més de 10 cm. Les formes petites s'anomenen microforaminífers i les grans macroforaminífers, essent aquests darrers característics de sediments carbonatats d'aigües poc profundes.

El subfílum Foraminifera forma, juntament amb el subfílum Radiozoa, el fílum Retaria, segons la classificació de 2003 de Thomas Cavalier-Smith.

Els foraminífers tenen un gran interès en estudis bioestratigràfics i s'utilitzen per a la datació de sediments i també com a indicadors paleoecològics.

Dírkonošci (Foraminifera, tedy v překladu „otvůrky nesoucí“) jsou jednobuněční mořští prvoci z říše Rhizaria. Vytvářejí vápnité, často velmi ozdobné schránky s mnoha drobnými otvůrky, z nichž vychází panožky. Jednobuněčnou nebo vícebuněčnou schránku vyplňuje protoplazma, která z něj částečně vystupuje ústím nebo drobnými póry. Dírkovci se vyskytují od prvohor dodnes. Mnohé rody se v určitých obdobích mimořádně rozšířily, jejich schránky měly podíl na tvorbě hornin (rod Fusulina v karbonu, Discocyclina a numulity v paleogénu). Na některých skupinách dírkovců je založená jemná stratigrafie druhohor (např. rody Globotruncana, Orbitoides) a třetihor (numulity, Miogypsina, Globorotalia), některé rody žijí v dnešních mořích (rod Globigerina).

Dírkonošci jsou blízkými příbuznými kmenu mřížovci (Radiozoa) a kmenu Cercozoa.

Klasifikace dírkonošců je v současné době velice problematická. Existují systémy založené na vzhledu schránek, ale ty se neshodují s molekulárně biologickými daty.[1] Podle fylogenetických výzkumů se zdá, že se dírkonošci dělí na dvě fundamentální linie, jedna zahrnuje zástupce bez schránky a druhá zahrnuje druhy se schránkou. Druhy se schránku s více komůrkami zřejmě vznikly v evoluční historii vícekrát.[2][3][4] Určité klasifikační systémy přesto existují, tento dělí například dírkonošce na 16 řádů:[5]

Mimo to byla popsána neobvyklá skupina Xenophyophorea, řazená rovněž do dírkonošců.[2]

Mezi dírkonošce řadíme jednoho z největších, dnes již vyhynulých prvoků, který se jmenuje penízek (Nummulites). Jeho spirálovité mnohokomůrkové schránky dosahují v průměru až 10 cm. Dnes tvoří mohutné vrstvy nummulitových vápenců. Další zástupce, kulovinka (Globigerina), se vyskytuje v mořích dodnes. Její schránky se usazují v podobě globigerinového bahna, které tuhne ve vápencové nebo křídové vrstvy.[6]

První zmínky jsou z 5. století před naším letopočtem. Hérodotos si všiml, že ve vápenci egyptských pyramid se nacházejí čočkovité útvary. Údajné „čočky“ nebyly nic jiného, než velké bentické foraminifery – numulité. V 17. století dírkovce zkoumali Robert Hooke a Anthony van Leeuwenhoek, kteří pořídili spousty nákresů. V průběhu 18. století popsal Carl Linné první organismy s pevnou schránkou, zařadil je ovšem mezi loděnky. V této době se uvažovalo o foraminiferách spíše jako o živočiších, než je v roce 1835 Dujarin zařadil do Protozoí. Krátce na to Alcide d'Orbigny vytvořil první klasifikaci. Dírkonošci byli hojně zakreslování, ovšem často bez jakékoli vědecké přesnosti, se zaměřením spíše na estetiku. Zlom nastal po expedici Challenger, která započala v roce 1872, a přinesla mnoho poznatků o organismech mořského dna, včetně obrovského množství detailních nákresů. Zkoumání foraminifer pokračuje i dnes (např. mechanismy vzniku aglutinované schránky).[7]

Dírkonošci jsou heterotrofní organismy, živící se substrátem, fytoplanktonem a zooplanktonem. Některé druhy mají symbiotické řasy Zooxantelly. Jedná se o mořské, převážně bentické organismy (infauna), které se vyskytují na písčitém i bahnitém substrátu. Existuje cca 4 000 recentních druhů, z toho asi 40 je planktonních. Jsou stenohalinní (snáší salinitu do 38‰), a pokrývají všechny mořské hloubkové zóny. Snáší i brakickou vodu. Vyskytují se ve všech zeměpisných šířkách, a jsou vhodnými indikátory znečištění. Obsah kyslíku je pro ně limitující. Ekologická flexibilita je velmi vysoká – díky tomu byly schopni přežít vymírání, které byly pro jiné druhy fatální. [8]

Formy bentické (žijí na dně, nebo pevném podkladu) jsou známy od kambria do recentu z mořských i brakických prostředí. Mají bohatě diverzifikované schránky (tvar, velikost i látkové složení). Schránka je tvořena jednou nebo více komůrkami, které jsou uspořádány do spirály, popř. jedné nebo více řad. Stěna může být slepená z různě velkých zrníček např. písku (aglutinovaná), organické hmoty, vzácně může být i křemitá. Karbonátové schránky jsou schopné akumulovat 1–5% stroncia, což je nejvyšší koncentrace ze všech mořských bezobratlých živočichů. Pod CCD (kompenzační karbonátová hloubka),se zachovávají pouze schránky aglutinované, díky rozpouštění CaCO3 v sedimentech. Rozdělení dírkonošců je umělé – podle rozměrů, dělí se na "velké" a "malé", hranice mezi nimi je kolem 5 mm. Horninotvorný význam mají především velké foraminifery, např. mladopaleozoické rody Fusulina a Schwagerina (mladší prvohory), rod Orbitolina (křída) a Nummulites (paleogén, schránky až 6 cm v průměru). Některé skupiny se živí diatomity.

Planktonické formy jsou známé už od svrchní jury. Vyskytují se v eufotické zóně vodního sloupce, což je zhruba od 50 do 100 m. Na vrcholcích středooceánských hřbetů tvoří "sníh" na dně oceánu. Schránky obsahují malé množství hořečnatého kalcitu, převažuje vápenec. Komůrky mají spirálovité uspořádání, stěny jsou hodně perforované póry. Čeleď Globigerinida se vyznačuje tím, že z povrchu schránek vybíhají dlouhé tenké jehlice, ovšem schránkám tvořícím sediment jehlice chybí. Pozdější ontogenetická stadia přecházejí do větších hloubek, proto se schránka modifikuje pomocí uložení silnější vrstvičky materiálu. Rozmnožování neprobíhá ve vodách s nižší salinitou než 30‰, tzn. nežijí v Černém moři, kde je salinita pouhých 17‰. Planktonní formy jsou hojné v hemipelagických sedimentech, v případě pelagických sedimentů se tvoří sediment spolu se zbytky vápnitého nanoplanktonu – tzv. foraminiferové kaly. Rychlost sedimentace je cca 1–8 cm za 1 000 let. V České republice se nachází v sedimentech České křídové pánve, a v křídových a třetihorních usazeninách Karpatské soustavy.

Existují i druhy bez schránky, ostatní organismy mají tři typy pevných schránek: organickou (tektinovou), aglutinovanou nebo vápnitou. Ve schránce můžeme najít otvory (lat. foramen – otvor) v podobě pórů a ústí, sloužící pro komunikaci jedince s okolním prostředím. Dírkovci mají panožky (rhizopodia) s granulátovou protoplazmou, různě modifikované pseudopodie, které slouží např. k nálezu a ulovení potravy, pohybu a stavbě schránky. Potrava dírkovců je variabilní. Typ a struktura schránky skvěle vypovídá o charakteru života daného jedince – zda byl epifaunní nebo infaunní. Epifaunní jedinci nemuseli dělat prostorové úspory, proto jsou zaoblené, naproti tomu infaunní jsou zploštělé, kvůli lepší pohyblivosti v substrátu. Lze tedy říci, že zde existuje vztah mezi tvarem a způsobem života. Schránka může být složena buď z jedné komůrky, nebo z více. Jednokomůrková schránka je fylogeneticky starší, a uvažuje se, že vznikla sekundárně z mnohakomůrkových. Mnohakomůrkové jsou fylogeneticky mladší a jsou členěné na více částí. První komůrka se nazývá proloculum. Mezi dalšími komůrkami nacházíme sutury (švy) a septa(přepážky).[9][10][11]

Nejpůvodnější typ. Je složen z tektinu (polysacharid), mívá lehce nazlátlou barvu. Dnes je spíše na ústupu.

Schránka je složena z mnoha drobných částeček – například zrnka písku, jehlice hub, schránky rozsivek a kokolitů, organický tmel, Ca, Si, a Fe. Dobře zachovatelný v fosilním záznamu.

Sekreční fosilní schránky jsou často kalcitové, v případě hlubokomořských schránek je časté prokřemenění. Člení se dále na 3 podtypy.

Tento typ je složen z oválných zrn kalcitu, které jsou obaleny v kalcitovém tmelu. Vypadá jako posypaný cukrem.

Jsou zde dvě vrstvy kalcitových krystalů, na světle se nápadně podobají porcelánu – odtud název.

Skládá se z více vrstev kalcitových nebo aragonitových krystalů uložených kolmo ke stěně schránky. Sklovitý vzhled.

Dochází k nepravidelnému střídání pohlavního a nepohlavního rozmnožování. Existuje zde pohlavní dimorfismus v podobě mikrosférických a makrosférických schránek. Při nepohlavním rozmnožování haploidní generace vytvoří velký proloculus (1. komůrka), a vzniká megalosferická schránka. Při pohlavním rozmnožování diploidní generace má tendenci vytvořit menší proloculus, jemuž se říká mikrosferický. Tyto generace se nepravidelně střídají, většinou ale chybí pohlavní cyklus.[9]

Podle molekulárních analýz mohou dírkonošci existovat 800 milionů až 1,2 miliardy let. Vyskytují se od kambria (cca před 550 miliony let) až dodnes. Planktonické formy zažily největší rozvoj v devonu (cca před 200 miliony lety), a ve spodní juře – celosvětově platné zónování křídy a terciéru podle foraminifer (uváděno s přesností až na 3–4 miliony let). Foraminifery přežily velká vymírání díky své adaptabilitě na změnu podmínek pro život. Velké foraminifery jsou známé od permokarbonu.

Díky kosmopolitnímu rozšíření jsou dírkonošci skvělými biostratigrafickými indikátory pro svrchní devon až recent. Díky nim máme materiál pro datování stáří, korelaci sedimentů, geochemické záznamy o teplotě moří a chemickém složení, salinitě, a mnoho dalšího. Foraminifery hrají zásadní roli v balancování a hospodaření v biosféře. Jsou ideální pro tvorbu paleoekologických rekonstrukcí. Velmi významné využití je rovněž v petrochemickém průmyslu, kdy na základě analýzy hornin lze najít ložiska.

Dírkonošci (Foraminifera, tedy v překladu „otvůrky nesoucí“) jsou jednobuněční mořští prvoci z říše Rhizaria. Vytvářejí vápnité, často velmi ozdobné schránky s mnoha drobnými otvůrky, z nichž vychází panožky. Jednobuněčnou nebo vícebuněčnou schránku vyplňuje protoplazma, která z něj částečně vystupuje ústím nebo drobnými póry. Dírkovci se vyskytují od prvohor dodnes. Mnohé rody se v určitých obdobích mimořádně rozšířily, jejich schránky měly podíl na tvorbě hornin (rod Fusulina v karbonu, Discocyclina a numulity v paleogénu). Na některých skupinách dírkovců je založená jemná stratigrafie druhohor (např. rody Globotruncana, Orbitoides) a třetihor (numulity, Miogypsina, Globorotalia), některé rody žijí v dnešních mořích (rod Globigerina).

Dírkonošci jsou blízkými příbuznými kmenu mřížovci (Radiozoa) a kmenu Cercozoa.

Foraminiferen (Foraminifera), selten auch Kammerlinge genannt, sind einzellige, zumeist gehäusetragende Protisten aus der Gruppe der Rhizaria. Sie umfassen rund 10.000 rezente und 40.000 fossil bekannte Arten und stellen damit die bei weitem größte Gruppe der Rhizaria dar.

Nur rund fünfzig Arten leben im Süßwasser, alle übrigen Foraminiferen bewohnen marine Lebensräume von den Küsten bis in die Tiefsee. Die Tiere besiedeln zumeist den Meeresboden (Benthos); ein kleiner Teil, die Globigerinida, lebt im Wasser schwebend (planktisch).

Die außerordentlich formenreiche Gruppe ist fossil seit dem Kambrium (vor rund 560 Millionen Jahren) nachgewiesen, Untersuchungen der molekularen Uhr verweisen jedoch auf ein deutlich höheres Alter von 690 bis 1150 Millionen Jahren.[1] Foraminiferen dienen in der Paläontologie aufgrund ihrer gut fossil erhaltungsfähigen, oft gesteinsbildenden Schalen als Leitfossilien der Kreide, des Paläogen und des Neogen.

Alle Arten der Foraminifera sind einzellige Lebewesen, die ein Alter von mehreren Monaten oder sogar einigen Jahren erreichen können.[2] Die Mehrheit der lebenden Arten ist zwischen 200 und 500 Mikrometer groß, die kleinsten Vertreter messen nur bis zu 40 Mikrometer (Rotaliella roscoffensis) und die größten bis zu 12 (Cycloclypeus carpenteri) oder sogar 20 Zentimeter (Acervulina).[3] Fast alle Arten besitzen ein in der Regel vielkammeriges Gehäuse. Durch dessen Perforation können in einzelnen Fällen fadenförmige, sehr dünne Cytoplasmateile austreten. Die Hauptmasse dieser rhizopoden Scheinfüßchen tritt aus der Mündung heraus und bildet untereinander ein Netzwerk, verteilt über das ganze Gehäuse.[4]

Die Gehäuse der Foraminiferen können sehr unterschiedlich gebaut sein, die Vielgestaltigkeit ihres Aufbaus dient als diagnostisches Merkmal zur Unterscheidung der Taxa. Relevant sind dabei zum einen das Material und zum anderen der zugrundeliegende Bauplan.

Anhand des Baustoffes ihrer Gehäuse lassen sich Foraminiferen in vier Gruppen einteilen:

Der bei weitem größten Gruppe dient sekretorisch ausgeschiedenes Calciumcarbonat (Kalk) als Baustoff, zumeist in Form des nicht stabilen Vaterit.[5] Später wird daraus Kalzit (Calcit), sehr selten Aragonit. Für eine genauere Untergliederung kann der Baustoff vor allem anhand seines Magnesiumsgehaltes (hoch/niedrig) weiter differenziert werden. Hingegen werden bei agglutinierenden Foraminiferen auf mineralischer oder proteinöser Basis aus dem Sediment aufgenommene Sandkörner oder andere Fremdkörper miteinander verklebt. Damit bilden sie eine höhere Form der rein proteinbasierten (selten sogar vollständig fehlenden) Gehäuse der Ordnung der Allogromiida, in die gelegentlich einzelne Partikel aus der Umgebung aufgenommen werden.[6]

Ein Sonderfall ist hingegen die nur aus der Gattung Miliammellus bestehende Ordnung Silicoloculinida, in der sich Gehäuse aus Opal finden (SiO2 x n H2O).[6]

Die Gehäuse können aus nur einer Kammer bestehen (monothalam), aus einer Reihe von miteinander verbundenen Kammern (polythalam) oder – sehr selten – ganz fehlen (athalam).[2] Die Trennwände der Kammern („Septa“) sind jeweils durchbrochen (lat. foramen ‚Öffnung, Loch‘) und erlauben dem Protoplasmakörper so, sich innerhalb des Gehäuses zu bewegen; die Öffnung der jeweils letzten Kammer („Apertur“) dient als Tor zur Umgebung.[7]

Mehrkammerige Gehäuse können unterschiedlich angeordnet sein. Die schlichteste Form ist der uniseriale Bau, bei dem eine Kammer auf die nächste folgt. Wenn die Kammern zwei zueinander versetzte Reihen bilden, spricht man von biserialen Gehäusen. Triseriale Gehäuse, also aus drei versetzten Reihen gebildet, heißen auch trochospiral und bilden einen Gegensatz zu planspiralen Gehäusen. Bei letzteren findet jeder Umlauf der Spirale auf der gleichen Ebene wie der vorhergehende statt, in der Seitenansicht bleibt das Gehäuse also flach. Trochospirale Gehäuse hingegen stellen sich mit jedem Umlauf in verbreiternden, schraubenförmigen Spiralen dar; ihre Spiralseite ist aufgewölbt und die Unterseite abgeflacht. Sonderformen sind miliolide Gehäuse, bei denen ein Umlauf der Spirale aus nur zwei länglich-röhrenförmigen Kammern entsteht und annuläre Gehäuse, die – ähnlich wie Jahresringe – kreisförmig angelegt sind. Im Zentrum der Spiralen liegt der Nabel, der sogenannte Umbilikus.[7]

Die Gehäuse der sandschaligen Textulariida sowie aller kalkschaligen Arten mit Ausnahme jener der porzellanschaligen Miliolida weisen 1 bis 10 Mikrometer messende Poren auf, die dem Gasaustausch sowie der Aufnahme und Abgabe von Nährstoffen dienen.[8]

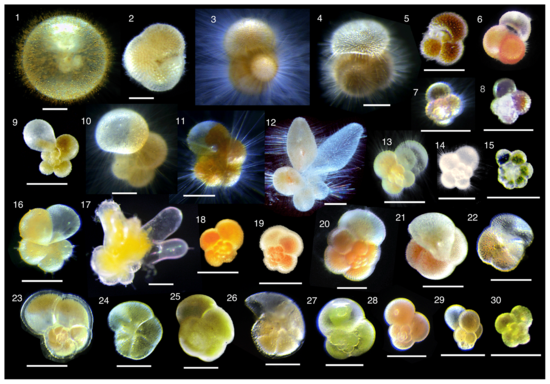

Die Gehäuse mehrkammeriger Foraminiferen sind oftmals nur zeit- oder teilweise mit Zytoplasma gefüllt, insbesondere jüngere Kammern bleiben oft leer. Das Zytoplasma ist zäh bis gelatinös und eigentlich farblos, wird aber durch Nahrung oder auch Endosymbionten vielfältig eingefärbt, von weißlich über gelblich, grünlich, orange, rötlich bis hin zu bräunlich. Die Färbung ist variabel und hängt auch davon ab, unter welchen ökologischen Umständen ein Individuum lebt oder in welcher Phase seines Lebenszyklus es sich befindet.[9]

Eine deutliche Differenzierung in Endoplasma und Ektoplasma gibt es nicht, das Gehäuse ist allerdings von einer dünnen Schicht Zytoplasma überzogen, das auch die Retikulopodien ausbildet.[9]

Wie alle Wurzelfüßer besitzen auch die Foraminiferen Scheinfüßchen (Pseudopodien). Diese Ausstülpungen aus dem Zytoplasma dienen der Verankerung im Untergrund, der Fortbewegung, der Aufnahme von Teilchen für den Gehäusebau sowie der Sammlung von Nährstoffen, dem Fang von Beute und gelegentlich der Verdauung außerhalb des Gehäuses. Sie sind lang, fadenförmig und dünn, an ihren jeweiligen Enden verjüngen sie sich auf einen Durchmesser von weniger als einen Mikrometer.[2][4]

Im Unterschied zu anderen Wurzelfüßern verfügen die Scheinfüßchen der Foraminiferen über die Fähigkeit der Anastomosie, können sich also verzweigen und mit anderen Scheinfüßchen wieder verschmelzen. Auf diese Weise können Foraminiferen ein komplexes Netz außerhalb ihres Körpers ausbilden, das sich über eine Fläche von mehreren hundert Quadratzentimetern ausbreiten kann. Man spricht in diesem Fall von Retikulopodien.[2]

Die Retikulopodien werden durch gelegentlich einzeln, meist jedoch in Bündeln auftretende Mikrotubuli verfestigt, die auch Bewegungen vermitteln, darunter als Besonderheit der Foraminifera eine bidirektionale Strömung des Zytoplasmas innerhalb der Retikulopodien.[2] Die Leitstruktur für die sogenannte „Körnchenströmung“ stellen Mikrotubulibündel dar, durch die mikroskopisch als Körnchen erkennbare Mitochondrien, Dichte Körper, Ummantelte und Elliptische Vesikel innerhalb der Retikulopodien in zwei Richtungen gleichzeitig (bidirektional) transportiert werden. Die ebenfalls als Körnchen in Erscheinung tretenden Phagosomen und Defäkationsvakuolen werden hingegen nur unidirektional transportiert.[10]

Die Lebenszyklen von Foraminiferen-Arten sind bis in die Gegenwart nur spärlich erforscht; vollständig bekannt sind sie nur für weniger als 30 der rund 10.000 Arten. Als typisch gilt ein heterophasischer Generationswechsel zwischen sexueller, haploider und asexueller, diploider Generation. Dieser Generationswechsel ist in einigen Gruppen evolutionär wieder modifiziert worden. Die beiden Generationen sind dabei in ihrer Gestalt verschieden (Dimorphismus). Die Variabilität des Lebenszyklus ist innerhalb der Foraminiferen jedoch außerordentlich hoch, von fast jedem Merkmal des typischen Lebenszyklus findet sich auch eine abweichende Form.[4]

Neben geschlechtlicher Vermehrung können sich insbesondere einkammerige Foraminiferen-Arten auch ungeschlechtlich fortpflanzen, und zwar über Knospung, Zellteilung und Cytotomie[11].

Ökologisch lassen sich Foraminiferen in vier Gruppen teilen. Klassisch ist die Trennung zwischen den nur rund fünfzig als Plankton lebenden Arten und der größten Gruppe, den auf dem Meeresboden lebenden benthischen Foraminiferen. Eine Sondergruppe der benthischen Foraminiferen bilden die rund fünfzig in lichtdurchfluteten Flachgewässern zu findenden Großforaminiferen. Erst in den letzten Jahren zeichnen sich dazu die Umrisse einer vierten Gruppe ab, jene der unbeschalten, in Süßgewässern lebenden Foraminiferen. Von ihnen sind bisher rund fünfzig Arten bekannt. Über den endgültigen Umfang dieser Gruppe lassen sich derzeit noch keine Angaben machen.[12]

Die benthischen Foraminiferen sind die nach Artenzahl bei weitem größte Gruppe und umfassen rund 10.000 Arten. Sie lassen sich bis an den tiefsten Punkt der Ozeane im 10.900 Meter tiefen Challengertief nachweisen, wo sie überaus häufige Elemente der dortigen Fauna sind.[13] Am Boden können sie fest mit dem Substrat verbunden sein oder frei umherschweifen, die Übergänge sind aber fließend, die Zustände häufig temporär.[14]

Zur Anheftung bedürfen benthische Arten fester Untergründe, auf denen sie sich meist mittels ihrer Pseudopodien (so z. B. bei Astrorhiza limicola, Elphidium crispum, Bathysiphon spp.), aber auch mit organischen Membranen (Patellina corrugata), Haftscheiben (Halyphysema) oder schwefelsauren Mucopolysacchariden (Rosalina spp.) verankern. Die Anheftung ist häufig nur temporär, in der Vorbereitung zur Fortpflanzung z. B. werden die Verbindungen wieder gelöst. Manche Arten können mit Geschwindigkeiten von bis zu 12 Zentimetern pro Stunde wandern. Als Untergründe dienen jedoch nicht allein Felsen oder ähnliches, sondern z. B. auch Schalen von Muscheln, Hydrozoen oder Brachiopoden, wo sie als Kommensalen im Nahrungsstrom agieren. Epiphytisch finden sie sich in Algen- oder Seegrasvegetationen, wo anfallender Detritus ihre Nahrungsgrundlage bildet. Auf weniger festen Untergründen finden sie sich als sogenannte „endobenthische Foraminiferen“ nicht allein auf der Sedimentoberfläche, sondern auch in Tiefen von bis zu 16 Zentimetern im Sediment (z. B. Elphidium spp.), teils aktiv Nahrung aufnehmend oder sich reproduzierend.[14]

Lichtlos lebende Arten fungieren vielfach als Zersetzer des Detritus insbesondere phytoplanktischen Ursprungs. Arten der Tiefsee leben dabei von bereits stärker zersetztem Material. Darüber hinaus gibt es fleisch-, pflanzen- oder allesfressende Arten, die sich beispielsweise als Weidegänger, Destruenten, Filtrierer oder Parasiten ernähren; viele Arten sind in ihrer Ernährung auf einzelne Beutegruppen spezialisiert. Die Lebensweise einiger dieser Arten ist zeitweise auch planktisch.[14][4]

Aus den benthischen Foraminiferen ausgegliedert wird meist die spezielle Gruppe der Großforaminiferen, die rund fünfzig Arten umfasst.[15] Sie zeichnen sich nicht allein durch ihre teils außerordentliche Größe von bis zu 13 Zentimetern aus, sondern vor allem durch ihre Lebensweise. Großforaminiferen kommen ausschließlich in flachen Gewässern von der Gezeitenzone bis rund 70, selten bis zu 130 Meter Tiefe vor. Sie beherbergen Algen (vereinzelt auch nur deren Chloroplasten) als Endosymbionten in ihren lichtdurchlässigen Gehäusen, über deren Photosynthese sie ihren Energiebedarf decken und Kalk zum Gehäusebau gewinnen. Großforaminiferen tragen rund 0,5 % zur weltweiten Karbonat-Produktion bei. Diese Symbiose ist mehrfach unabhängig voneinander entstanden und umfasst je nach Familie als Symbionten Rotalgen, Chlorophyten, Dinoflagellaten oder Kieselalgen. Die Symbionten finden sich als Zoochlorellae bzw. Zooxanthellae im Zytoplasma benthischer Foraminiferen und können bis zu 75 % des Gehäusevolumens einnehmen; ihre Anzahl beträgt nach Schätzungen über 100.000 bei Peneroplis pertusus bzw. rund 150.000 bei Heterostegina depressa.[16][17]

Großforaminiferen sind rein tropisch oder subtropisch verbreitet. Ihre höchste Artenvielfalt erreichen sie im indopazifischen Raum. Sie finden sich aber auch in der Karibik, im Zentralpazifik sowie im Golf von Akaba. Vertreter finden sich in den Familien Nummulitidae, Amphisteginidae und Calcarinidae der Ordnung Rotaliida, sowie Alveolinidae, Peneroplidae und Soritidae der Ordnung Miliolida. Die wohl bekanntesten Vertreter sind die Arten der Gattung Baculogypsina, deren charakteristisch geformte Gehäuse an den Stränden der Ryukyu-Inseln den sogenannten „Sternensand“ bilden. Die am weitesten verbreitete Art hingegen ist Heterostegina depressa.[17]

Die bestehenden Populationen der Großforaminiferen gelten als Relikte wesentlich diverserer Gruppen, die z. B. im Karbon und Perm (Fusulinida) bzw. im Tertiär sedimentbildende Verbreitung besaßen. Sie leben meist in großen Gruppen und sind sogenannte K-Strategen, die begrenzte Ressourcen nutzen und zu deren adäquater Nutzung nur langsam wachsen und in konstanten Populationsgrößen auftreten. Bemerkenswert ist ihre Lebensdauer, die mehrere Jahre betragen kann und von keinen anderen Einzellern erreicht wird.[15]

Mit nicht ganz fünfzig bekannten Arten, die sämtlich zur Ordnung Globigerinida gehören, ist der Anteil der im Plankton lebenden Foraminiferen rein nach Artenzahl gering. Die Tatsache, dass planktische Foraminiferen als die bedeutendsten Karbonat-Produzenten rund 20 % der jährlichen Menge produzieren, verdeutlicht jedoch ihre große Biomasse. Sie sind in polaren bis tropischen Meeren verbreitet, besonders viele Arten finden sich in subtropischen bis tropischen Gewässern. Gehäuft kommen sie vor allem in oberflächennahen Wasserlagen zwischen 10 und 50 Metern vor, reichen aber auch in Tiefen bis zu 800 Metern.[18] Viele Arten beherbergen wie die Großforaminiferen photosynthetisierende Symbionten in Gestalt des spezialisierten Dinoflagellaten Gymnodinium beii oder Goldbrauner Algen.[17]

Die klassische Vorstellung von Foraminiferen als exklusiv marine Lebewesen mit Gehäusen wurde durch Forschungsergebnisse seit der Jahrtausendwende in Frage gestellt. Zwar waren bereits in der zweiten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts mehrere Süßwasser-Arten aus dem Genfersee erstbeschrieben worden, ebenso wie bei der seit 1949 bekannten Reticulomyxa filosa aber war ihre systematische Position unklar, meist wurden sie zu anderen Gruppen als den Foraminiferen gestellt. Auch der Umfang der Gruppe, ihre Verbreitung und Lebensweise waren annähernd unerforscht, noch 2003 schrieb Maria Holzmann: „Süßwasserforaminiferen sind eine der rätselhaftesten Gruppen der Protisten.“[19] Über molekularbiologische Untersuchungen konnte nicht nur für einige von ihnen der Nachweis erbracht werden, dass es sich um Foraminiferen handelt,[20][21] sondern anhand von Sequenzierungen von Umweltproben verschiedener Herkunft konnte auch festgestellt werden, dass es zahlreiche noch unbekannte Arten gibt. Als Resümee dieser Proben konnte entgegen bisherigen Annahmen festgestellt werden, dass „Foraminiferen in Süßwasserumgebungen weitverbreitet sind“.[19] Die Erstbeschreibung einer sogar terrestrisch lebenden Art wie Edaphoallogromia australica zeigt, dass Foraminiferen auch außerhalb von Gewässern Verbreitung finden.[22][19]

Foraminiferen sind unter anderem in der Paläontologie von Bedeutung. Verwesungsresistente Gehäuse können nach dem Absterben der Zelle durch Fossilisation erhalten bleiben. Anhand von fossilen Foraminiferen-Vergesellschaftungen kann man die Umweltbedingungen vergangener Zeiten rekonstruieren und die sie enthaltenden Gesteine relativ datieren (Biostratigraphie). Ab der Kreidezeit stellen planktische Foraminiferen aufgrund ihrer marinen Lebensweise und somit fast weltweiter Verbreitung wichtige Leitfossilien. Einige fossile Formen traten in solchen Mengen auf, dass sie gesteinsbildend wurden, so die Globigerinen (Globigerinida), die Fusulinen (Fusulinida) und die Nummuliten (Nummulitidae).[23] Berühmte derartige Gesteine sind die eozänen Nummulitenkalke, die beim Bau der ägyptischen Pyramiden verwendet wurden.[11][24][25]

Von großer Bedeutung ist dies für die Erdölindustrie. Bei Bohrungen kann anhand der Arten erkannt werden, ob hier zu früheren Zeiten für die Entstehung von Erdöllagern günstige klimatische Bedingungen geherrscht haben.[24]

Auch in der Paläoklimatologie spielen Foraminiferen eine wichtige Rolle als Proxy für die Rekonstruktion des Klimas vergangener Erdzeitalter. Speziell für die Erstellung der Sauerstoff-Isotopenstufen, aufgrund derer zwischen Warm- und Kaltzeiten unterschieden wird, kommen Foraminiferen aus limnischen oder marinen Sedimentbohrkernen zum Einsatz. Dabei erfolgt eine Altersdatierung anhand des Verhältnisses der Isotope 16O und 18O. Lokal wirken sich die reduzierten Ozeantemperaturen während der Kaltzeiten auch auf das Isotopenverhältnis der Kalkschale der Foraminifere aus, denn diese fraktioniert beim Einbau des Kalziumkarbonats in ihr Gehäuse das 16O/18O-Verhältnis bei geringeren Temperaturen hin zum schwereren Isotop (Temperatureffekt). Eine erhöhte Verdunstung im Lebensraum der Foraminifere, aber auch ein erhöhter Eintrag von isotopisch leichterem Schmelzwasser führen zu einer Verschiebung des 16O/18O-Verhältnisses im Wasser und somit im Gehäuse (Salinitätseffekt).[26][27]

Adl et al. ordneten 2007 die Foraminiferen als eines der fünf Taxa innerhalb der Rhizaria ein, deren bei weitem größte Gruppe sie sind. Auf der Basis von molekularbiologisch ermittelten Stammbäumen stellten die Foraminiferen die Schwestergruppe der Gattung Gromia dar und bildeten entsprechend mit diesen ein gemeinsames Taxon.[28] Neuere molekularbiologische Untersuchungen von 2012 ergeben laut Adl et al. jedoch, dass die Gattung Gromia keine Schwestergruppe ist.[29] Die nächsten Verwandten sind wahrscheinlich die Acantharia und die Polycystinea.[29]

Die Foraminiferen umfassen rund 10.000 rezente und 40.000 fossil bekannte Arten[30] in rund 65 Überfamilien und 300 Familien, rund 150[17] davon rezent.

Die innere Systematik der Gruppe hingegen gilt unter molekulargenetischen Gesichtspunkten noch als weitgehend unklar. Vor allem die Tatsache, dass die dazu notwendige DNA meist nur in unzureichender Menge gewonnen werden kann, da sich die meisten Foraminiferen im Labor nicht kultivieren lassen und nur von extrem wenigen Arten überhaupt DNA zur Verfügung steht, erschwert umfangreiche und repräsentative Untersuchungen.[31] Auch technische Hindernisse machen die Erstellung phylogenetischer Stammbäume schwierig: Sogenannte Long-branch-attraction-Artefakte führen im Rahmen der für Untersuchungen häufig gebrauchten SSU rDNA oft zu schweren statistischen Fehlern. Daher konnte erst der Gebrauch experimenteller Markergene (Aktin-[32], RNA-Polymerase-II-Gen[31]) die anfänglichen Ergebnisse stabilisieren. Deutlich zeichnet sich in allen Untersuchungen ab, dass die Ordnungen Allogromiida und Astrorhizida zusammen mit einigen oft als Athalamidae geführten schalenlosen Foraminiferen eine paraphyletische Gruppe bilden und dass die Miliolida aus ihnen hervorgingen. Auch sind die Globigerinida ebenso wie die Buliminida wohl ein Teil der Rotaliida.

Alle bisherigen Systematiken basieren daher, auch aufgrund der großen Anzahl der ausschließlich durch ihre Gehäuse bekannten fossilen Arten, noch immer auf morphologischen Merkmalen[33]. Die derzeit aktuelle umfassende Systematik der Foraminiferen geht auf Alfred R. Loeblich und Helen Tappan zurück und wurde 1992 vorgestellt. Sie diente auch als Grundlage für die modifizierte und ergänzte Systematik von Barun Sen Gupta aus dem Jahre 2002, die hier herangezogen wird. Die Foraminiferen werden dort als Klasse verstanden und in 16 Ordnungen untergliedert († = ausgestorben).[6]

Spätere molekularbiologische Untersuchungen weisen darauf hin, dass auch die bis dato als eigene Klasse unsicherer Stellung verstandenen Xenophyophoren zu den Foraminiferen zu zählen und eng verwandt mit der Gattung Rhizammina (Astrorhizida) sind. Ihre genaue Position innerhalb des obigen Systems ist allerdings nicht definiert.[34]

Lange wurden vom Menschen nur die fossilierten Schalen der Foraminiferen wahrgenommen. Frühe Autoren erkannten nicht deren Ursprung als Gehäuse von Lebewesen. So deutete Strabo die Nummuliten im Kalk der Pyramiden von Gizeh als Kotreste der Arbeiterschaft und noch vom 16. bis 18. Jahrhundert wurde wie bei allen Fossilien meist angenommen, es handele sich schlicht um Steine.[24]

Antoni van Leeuwenhoek dokumentierte 1700 den Fund einer Foraminiferenschale „nicht größer als ein Sandkorn“ im Magen einer Garnele. Von ihm als Weichtier angesehen, lässt sie sich anhand seiner Zeichnung sicher als Art der Gattung Elphidium bestimmen.[35] Unabhängig davon meinte Johann Jakob Scheuchzer zu gleicher Zeit, dass „diese Steine wahrhaft Schnecken und nicht in der Erden durch ich weiß nicht was vor einen Archeum gebildet worden“.[24] Diese Zuordnung zu den Weichtieren war zwar falsch, immerhin jedoch war nunmehr der Charakter der Foraminiferen als Lebewesen erkannt. Die Pionierarbeit von Janus Plancus, der 1739 einige Foraminiferen vom Strand von Rimini beschrieb, diente Carl von Linné 1758 als Grundlage für seine Platzierung der Arten bei den Perlbooten (Nautilus).[24]

Als eigenständige systematische Gruppe wurden sie jedoch erst 1826 durch die Erstbeschreibung der Foraminiferen von Alcide d’Orbigny manifest. Sah er sie ursprünglich noch als Ordnung der Kopffüßer an und blieb damit innerhalb der traditionellen Vorstellung der Foraminiferen als einer Gruppe von Weichtieren, so erhob er sie 1839 zu einer eigenen Klasse.

Dem voraus gingen die ersten Erkenntnisse zur Biologie der Foraminiferen, insbesondere die von Félix Dujardin (1801–1860) zum Aufbau des eigentlichen "Körpers". Er nannte den kontraktilen internen Stoff, der sich spontan durch die Poren der Kalkschalen in Form von Pseudopodien drängte, Sarkode; später wurde diese Bezeichnung von Hugo von Mohl (1805–1872) durch die bis heute gültige Protoplasma ersetzt. Félix Dujardin sah in den Foraminiferen Einzeller, Rhizopoden, wie er diese nannte, mit Schalen (Rhizopodes á coquilles).

D’Orbigny war es auch, der die paläontologische Erforschung der Foraminiferen begann, während zugleich vornehmlich britische Forscher erste ökologische Forschungen durchführten. In der zweiten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts erwies sich die zwischen 1873 und 1876 unternommene Challenger-Expedition auch für die Foraminiferenkunde als außerordentlich erfolgreich. Henry Bowman Bradys 1884 erschienener „Report on the Foraminifera dredged by H.M.S. Challenger“ gilt bis in die Gegenwart als ein klassisches Werk über rezente Arten. Zu gleicher Zeit konnten auch grundlegende Fragen des Zellaufbaus (z. B. Nachweis eines Zellkerns durch Hertwig und Schulze 1877) und des Lebenszyklus (Entdeckung von Gehäusedimorphismen durch Maximilian von Hantken 1872, Grundlagen der Vermehrung von Schaudinn und Lister 1894/95) geklärt werden.[24]

Im 20. Jahrhundert wurden die Kenntnisse über die Foraminiferen vor allem durch drei US-amerikanische Forscher bereichert. Joseph Augustine Cushman legte den Grundstein der modernen Foraminiferenforschung, indem er neben der Beschreibung einer gewaltigen Anzahl neuer Arten auch das Cushman Laboratory for Foraminiferal Research sowie das bis in die Gegenwart bedeutende Fachmagazin „Contributions from the Cushman Laboratory for Foraminiferal Research“ gründete, heute „Journal of Foraminiferal Research“. Im Jahrzehnt zwischen 1931 und 1940 wurden 3800 Arten neu aufgestellt, im Jahr 1935 erschienen rund 360 Arbeiten über Foraminiferen, 1936 bereits doppelt so viele. Diese Wissensexplosion war einerseits auf die Materialzunahme durch Meeresexpeditionen zurückzuführen, andererseits aber auch auf das gestiegene Interesse der Erdölindustrie an Foraminiferen als Leitfossilien (Anzeiger für das geologische Alter der Erdschicht) bei der stratigraphischen Analyse von Erdölbohrungen.[24]

1940 erschien der erste Band des Catalogue of Foraminifera von B. F. Ellis und A. R. Messina, von dem bis heute 94 Bände erschienen sind, die annähernd jede je beschriebene Foraminifere aufführen.[11] Das noch immer weitergeführte Werk liegt mittlerweile in digitaler Form vor und enthält annähernd 50.000 Arten.[36]

Nach Cushmans Tod 1949 dominierte die Arbeit des Ehepaares Helen Tappan und Alfred R. Loeblich in der zweiten Hälfte des Jahrhunderts. War Cushman systematisch noch älteren Ideen verhaftet gewesen, überarbeiteten Loeblich und Tappan die Systematik der Foraminiferen grundlegend und publizierten ihre Ergebnisse in zwei großen monographischen Veröffentlichungen 1964 und 1989, die bis in die Gegenwart maßgeblich sind. Neuere systematische Ansätze wie die von Valeria I. Mikhalevich[37] sind weder vollständig noch haben sie sich bisher durchgesetzt, ebenso wenig molekularbiologische Untersuchungen (insbesondere durch Jan Pawlowski).

Fußnoten direkt hinter einer Aussage belegen die einzelne Aussage, Fußnoten hinter einer Leerstelle vor Satzzeichen den gesamten vorangehenden Satz. Fußnoten hinter einer Leerstelle beziehen sich auf den kompletten vorangegangenen Text.

Foraminiferen (Foraminifera), selten auch Kammerlinge genannt, sind einzellige, zumeist gehäusetragende Protisten aus der Gruppe der Rhizaria. Sie umfassen rund 10.000 rezente und 40.000 fossil bekannte Arten und stellen damit die bei weitem größte Gruppe der Rhizaria dar.

Nur rund fünfzig Arten leben im Süßwasser, alle übrigen Foraminiferen bewohnen marine Lebensräume von den Küsten bis in die Tiefsee. Die Tiere besiedeln zumeist den Meeresboden (Benthos); ein kleiner Teil, die Globigerinida, lebt im Wasser schwebend (planktisch).

Die außerordentlich formenreiche Gruppe ist fossil seit dem Kambrium (vor rund 560 Millionen Jahren) nachgewiesen, Untersuchungen der molekularen Uhr verweisen jedoch auf ein deutlich höheres Alter von 690 bis 1150 Millionen Jahren. Foraminiferen dienen in der Paläontologie aufgrund ihrer gut fossil erhaltungsfähigen, oft gesteinsbildenden Schalen als Leitfossilien der Kreide, des Paläogen und des Neogen.

Foraminifera utawi asring dipunwastani foram inggih punika salah satunggaling organisme sèl satunggal ingkang gadhah thothok kalsit lan asring kawastanan rhizopoda (suku semu).[1] Foraminifera kalebet golongan ageng saking krajan protista kanthi pseudopodia.[2] Foraminifera mèmper kaliyan amoeba, nanging amoeba boten gadhah thothok kados foraminifera kanggé ngayomi protoplasmanipun.[1] Cangkang utawi kerangka saking foraminifera saged dipundadosaken pitedah kanggé ngupadi sumber daya lenga, gas alam, kaliyan mineral ing salebeting bumi.[2] Cangkang foraminifera ngandhut kalsium karbonat (CaCO3).[3] Manawi foraminifera mati, thothokipun lajeng mbentuk siti (tanah) globerina.[3] Siti punika ingkang fungsinipun dados pitedah wontenipun sumber lenga.[3] Foraminifera angsal panganan saking kasil fotosintesis alga ingkang nindakaken simbiosis wonten ing sangandhaping thothok foraminifera.[3] Foraminifera padatanipun gesang wonten ing segara.[3]

Jinis-jinis foraminifera punika manéka werni. Foraminfera dipunklasifikasikaken miturut wangunipun thothok kaliyan miturut caranipun gesang.[1]

Miturut wangun thothokipun, foraminifera dipunpérang dados 3, inggih punika:

Miturut caranipun gesang, foraminifera dipunpérang dados 2, inggih punika:

|coauthors= (pitulung) De Foraminifera sünd en Stamm vun de Rhizeria in't Riek vun de Protisten. Dat sünd Planktons un anner Formen. Dat gröttste Exemplar hett en Grött vun 19 cm.

Circa 250.000 Arten sünd bekannt, levend un fossil. De Steen vun de Pyramiden in Ägypten weern ut Forminifera.

The University of California Berkeley's Museum of Paleontology's

The Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of Natural History

Foraminifera (Laitin for "hole beirers"; informally cried "forams") are members o a phylum or cless o amoeboid protists chairacterised bi streamin granular ectoplasm for catchin fuid an ither uises; an commonly an fremmit shell (cried a "test") o diverse forms an materials.

Foraminifera (značenje na latinskom: nosači rupa) ili krednjaci je i koljeno ili razred ameboidnih protista s obilježavajućim strujanjem granulirane ektoplazme kroz otvore na ljušturici, za hvatanje hrane i druge namjene. Obično imaju vanjsku ljusku, različitih oblika i materijala. Za testove hitinske testove (koji se nalaze u nekim jednostavnim rodovima, posebno Textularia) vjeruje se da je najprimitivniji tip. Većina foraminifera su morske, od kojih većina kojih živi na sedimentu morskog dna ili unutar njega (bentoske), dok manje varijante plutaju u vodenom stubu na različitim dubinama (planktonske). Manje ih je poznato iz slatkovodnih ili bočatih uvjeta, a neke vrlo rijetke (neakvatične) koje žive u tlu itentificirane su analizom malih molekulskih podjedinica iRNK.[1][2]

Foraminifere tipski proizvode krečnjačku oblogu ili ljusku, koja može imati jednu ili više komora, od kojih neke postaju prilično složene strukture.[3] Njihove ljušture su obično napravljene od kalcij-karbonata (CaCO3) ili aglutiniranih čestica sedimenta. Prepoznato je preko 50.000 vrsta, živućih (10.000) i fosilnih (40. 000).[4][5][6] Obično su manje od 1 mm, ali neke su I mnogo veće, kao što je najveća od njih Xenophyophore sp., koja doseže do oko 20 cm.[7]

Dužna im je obično od oko 20 μm do 15 cm (numuliti). Tijelo im je u kućici (ljušturi), koja može biti ravna, stožasta, spiralna, obično s više komorica (politalamni oblici) s mnogim otvorima (foramina), za lažne nožice (pseudopodije) u obliku dugih niti. U ciklusu razmnažavanja imaju smjenu nespolne i spolne generacije. Većinom žive na dnu mora, a manji broj vrsta živi u pelagijskoj zoni u planktonskim zajednicama. Kućice uginulih životinja padaju na morsko dno i tokom dugih perioda nagomilaju se i tvore debele naslage krečnjaka. Tako se na obalama Mediterana i u nekim dijelovima Sahare nalaze debele naslage iz tercijara, koji se sastoje od krupnih ljušturica (do 15 cm) fosilnih numulita. Drugi fosilni rod, Fusulina, bio široko i bogato rasprostranjen u karbonu. Dno Atlantika pretežito se sastoji od globigerinskoga mulja, u kojem krednjaci (uglavnom roda Globigerina) čine 75% ukupne mase.

Taksonomska pozicija Foraminifera varirala je od Schultzeova priznanja kao protozoa (protista) 1854. godine,[8] gdje se spominje kao red Foraminiferida. Loeblich i Tappan (1992.) rerangirali su Foraminifera kao razred[9] kao što se i sada uobičajeno čini.

Foraminifera su obično uključivane u Protozoa,[10][11][12] ili u carstvo Protoctista ili Protista.[13][14] Prihvatljivi dokazi, zasnovani prvenstveno na molekulskoj filogeneti, postoje za njihovu pripadnosti velikoj grupi Protozoa, poznatoj kao Rhizaria.[10] Prije prepoznavanja evolucijskih odnosa među članovima Rhizaria, Foraminifera su uglavnom grupirane s drugim amoeboidima kao phhum Rhizopodea (ili Sarcodina) u klasi Granuloreticulosa.

Rhizaria su problematične, jer se često nazivaju "supergrupa", umjesto da se koristi utvrđeni taksonomski rang kao što je koljeno. Cavalier-Smith definira Rhizaria kao infracarstvo unutar carstva Protozoa. Neke taksonomije postavljaju Foraminifere u posebno carstvo, stavljajući ih uz rame sa ameboidnimm sarkodinama u koje su smještene.[10] Iako još nisu podržani morfološkim korelirajućim dokazima, molekularni podaci snažno sugeriraju da su Foraminifere usko povezane sa Cercozoa i Radiolaria, a oba uključuju amoeboide sa kompleksnim kućicama; ove tri grupe čine Rhizaria. Međutim, još uvijek nisu u potpunosti jasni tačni odnosi krednjaka s ostalim skupinama i jednih prema drugima. Usko su povezani sa testatne amebe.[15]

Krednjaci galerija:

Krednjaci kroz mikroskop:Krednjak Baculogypsina sphaerulata s otoka Hatoma u Japanu. Širina vidnog polja = 5,22 mm.

Krednjak Heterostegina depressa., Indonezija. Širina vidnog polja = 5,22 mm.

Foraminifere iz Jadranskog mora, otok Pag.

Koralni fosilni krednjaci Nummulites, Ujedinjeni Arapski Emirati.

Foraminifera utawi asring dipunwastani foram inggih punika salah satunggaling organisme sèl satunggal ingkang gadhah thothok kalsit lan asring kawastanan rhizopoda (suku semu). Foraminifera kalebet golongan ageng saking krajan protista kanthi pseudopodia. Foraminifera mèmper kaliyan amoeba, nanging amoeba boten gadhah thothok kados foraminifera kanggé ngayomi protoplasmanipun. Cangkang utawi kerangka saking foraminifera saged dipundadosaken pitedah kanggé ngupadi sumber daya lenga, gas alam, kaliyan mineral ing salebeting bumi. Cangkang foraminifera ngandhut kalsium karbonat (CaCO3). Manawi foraminifera mati, thothokipun lajeng mbentuk siti (tanah) globerina. Siti punika ingkang fungsinipun dados pitedah wontenipun sumber lenga. Foraminifera angsal panganan saking kasil fotosintesis alga ingkang nindakaken simbiosis wonten ing sangandhaping thothok foraminifera. Foraminifera padatanipun gesang wonten ing segara.

Foraminifera (Laitin for "hole beirers"; informally cried "forams") are members o a phylum or cless o amoeboid protists chairacterised bi streamin granular ectoplasm for catchin fuid an ither uises; an commonly an fremmit shell (cried a "test") o diverse forms an materials.

Foraminifera (značenje na latinskom: nosači rupa) ili krednjaci je i koljeno ili razred ameboidnih protista s obilježavajućim strujanjem granulirane ektoplazme kroz otvore na ljušturici, za hvatanje hrane i druge namjene. Obično imaju vanjsku ljusku, različitih oblika i materijala. Za testove hitinske testove (koji se nalaze u nekim jednostavnim rodovima, posebno Textularia) vjeruje se da je najprimitivniji tip. Većina foraminifera su morske, od kojih većina kojih živi na sedimentu morskog dna ili unutar njega (bentoske), dok manje varijante plutaju u vodenom stubu na različitim dubinama (planktonske). Manje ih je poznato iz slatkovodnih ili bočatih uvjeta, a neke vrlo rijetke (neakvatične) koje žive u tlu itentificirane su analizom malih molekulskih podjedinica iRNK.

Foraminifere tipski proizvode krečnjačku oblogu ili ljusku, koja može imati jednu ili više komora, od kojih neke postaju prilično složene strukture. Njihove ljušture su obično napravljene od kalcij-karbonata (CaCO3) ili aglutiniranih čestica sedimenta. Prepoznato je preko 50.000 vrsta, živućih (10.000) i fosilnih (40. 000). Obično su manje od 1 mm, ali neke su I mnogo veće, kao što je najveća od njih Xenophyophore sp., koja doseže do oko 20 cm.

De Foraminifera sünd en Stamm vun de Rhizeria in't Riek vun de Protisten. Dat sünd Planktons un anner Formen. Dat gröttste Exemplar hett en Grött vun 19 cm.

Circa 250.000 Arten sünd bekannt, levend un fossil. De Steen vun de Pyramiden in Ägypten weern ut Forminifera.

Τα τρηματοφόρα (foraminifera) αποτελούν τη συνομοταξία Foraminifera και χαρακτηρίζονται ως μονοκύτταροι οργανισμοί με δίκτυο από ψευδοπόδια. Έχουν ετεροφασικό κύκλο ζωής και στις περισσότερες περιπτώσεις φέρουν κέλυφος που συνίσταται κυρίως από ανθρακικό ασβέστιο (CaCO3) και καλύπτει το πρωτόπλασμα του οργανισμού. Ακόμα είναι ετερότροφοι οργανισμοί, δηλαδή φέρουν ζωικά χαρακτηριστικά, ενώ αξιοσημείωτος είναι ο αριθμός ειδών που χρησιμοποιούν για την τροφή τους το μεγαλύτερο μέρος των προιόντων της φωτοσύνθεσης που λαμβάνουν από ενδοσυμβιωτικούς οργανισμούς. Των περισσοτέρων τρηματοφόρων τα κελύφη έχουν μέγιστη διάμετρο 100-500 μm. Ωστόσο τα μεγάλου μεγέθους βενθονικά τρηματοφόρα χαρακτηρίζονται από διάμετρο εώς και 20cm και πολύπλοκη εσωτερική κατασκευή. Τα τρηματοφόρα γενικά ζουν σε όλα τα θαλάσσια οικοσυστήματα, ενώ ορισμένα είδη τους και σε υφάλμυρα. Ανάλογα με τον τρόπο ζωής τους χωρίζονται σε βενθονικά και πλαγκτονικά τρηματοφόρα.

Τα τρηματοφόρα λαμβάνουν σημαντικό ρόλο στους βιογεωχημικούς κύκλους του άνθρακα και του ασβεστίου των ωκεάνιων συστημάτων και μαζί με τα κοκκολιθοφόρα θεωρούνται ως οι κύριες ομάδες της βιογενούς ανθρακικής ιζηματογένεσης. Η συνολική συνεισφορά των βενθονικών και πλαγκτονικών τρηματοφόρων στην απόθεση ανθρακικού ασβεστίου είναι γύρω στα 1,4 δισεκατομμύρια τόνους το χρόνο, περίπου δηλαδή το 25% της συνολικής παραγωγής πελαγικών ανθρακικών ιζημάτων.

Langer, M.,1993. Epiphytic foraminifera. Marine Micropaleontology 20, 235-265

Τα τρηματοφόρα (foraminifera) αποτελούν τη συνομοταξία Foraminifera και χαρακτηρίζονται ως μονοκύτταροι οργανισμοί με δίκτυο από ψευδοπόδια. Έχουν ετεροφασικό κύκλο ζωής και στις περισσότερες περιπτώσεις φέρουν κέλυφος που συνίσταται κυρίως από ανθρακικό ασβέστιο (CaCO3) και καλύπτει το πρωτόπλασμα του οργανισμού. Ακόμα είναι ετερότροφοι οργανισμοί, δηλαδή φέρουν ζωικά χαρακτηριστικά, ενώ αξιοσημείωτος είναι ο αριθμός ειδών που χρησιμοποιούν για την τροφή τους το μεγαλύτερο μέρος των προιόντων της φωτοσύνθεσης που λαμβάνουν από ενδοσυμβιωτικούς οργανισμούς. Των περισσοτέρων τρηματοφόρων τα κελύφη έχουν μέγιστη διάμετρο 100-500 μm. Ωστόσο τα μεγάλου μεγέθους βενθονικά τρηματοφόρα χαρακτηρίζονται από διάμετρο εώς και 20cm και πολύπλοκη εσωτερική κατασκευή. Τα τρηματοφόρα γενικά ζουν σε όλα τα θαλάσσια οικοσυστήματα, ενώ ορισμένα είδη τους και σε υφάλμυρα. Ανάλογα με τον τρόπο ζωής τους χωρίζονται σε βενθονικά και πλαγκτονικά τρηματοφόρα.

Τα τρηματοφόρα λαμβάνουν σημαντικό ρόλο στους βιογεωχημικούς κύκλους του άνθρακα και του ασβεστίου των ωκεάνιων συστημάτων και μαζί με τα κοκκολιθοφόρα θεωρούνται ως οι κύριες ομάδες της βιογενούς ανθρακικής ιζηματογένεσης. Η συνολική συνεισφορά των βενθονικών και πλαγκτονικών τρηματοφόρων στην απόθεση ανθρακικού ασβεστίου είναι γύρω στα 1,4 δισεκατομμύρια τόνους το χρόνο, περίπου δηλαδή το 25% της συνολικής παραγωγής πελαγικών ανθρακικών ιζημάτων.

फोरामिनिफेरा (Foraminifera ; /fəˌræməˈnɪfərə/ लैटिन अर्थ- hole bearers, informally called "forams") ) अथवा पेट्रोलियम उद्योग का तेल मत्कुण (oil bug), प्रोटोज़ोआ संघ के वर्ग सार्कोडिन के उपवर्ग राइज़ोपोडा का एक गण है। इस गण के अधिकांश प्राणी प्राय: सभी महासागरों और समुद्र में सभी गहराइयों में पाए जाते हैं। इस गण की कुछ जातियाँ अलवण जल में और बहुत कम जातियाँ नम मिट्टी में पाई जाती हैं। अधिकांश फ़ोरैमिनाफ़ेरा के शरीर पर एक आवरण होता है, जिसे चोल या कवच (test or shell) कहते हैं। ये कवच कैल्सीभूत, सिलिकामय, जिलेटिनी अथवा काइटिनी (chitinous) होते हैं, या बालू के कणों, स्पंज कंटिकाओं (spongespicules), त्यक्त कवचों, या अन्य मलवों (debris) के बने होते हैं। कवच का व्यास .०१ मिमी. से लेकर १९० मिमी. तक होता है तथा वे गेंदाकार, अंडाकार, शंक्वाकार, नलीदार, सर्पिल (spiral), या अन्य आकार के होते हैं।

कवच के अंदर जीवद्रव्यी पिंड (protoplasmic mass) होता है, जिसमें एक या अनेक केंद्रक होते हैं। कवच एककोष्ठी (unilocular or monothalamus), अथवा श्रेणीबद्ध बहुकोष्ठी (multilocular or polythalmus) और किसी किसी में द्विरूपी (dimorphic) होते हैं। कवच में अनेक सक्षम रध्रों के अतिरिक्त बड़े रंध्र, जिन्हें फ़ोरैमिना (Foramina) कहते हैं, पाए जाते हैं। इन्हीं फोरैमिना के कारण इस गण का नाम फ़ोरैमिनीफ़ेरा (Foraminifera) पड़ा है। फ़ोरैमिनीफ़ेरा प्राणी की जीवित अवस्था में फ़ोरैमिना से होकर लंबे धागे के सदृश पतले और बहुत ही कोमल पादाभ (pseudopoda), जो कभी कभी शाखावत और प्राय: जाल या झिल्ली (web) के समान उलझे होते हैं, बाहर निकलते हैं।

वेलापवर्ती (pelagic) फ़ोरैमिनीफ़ेरा के कवच समुद्रतल में जाकर एकत्र हो जाते हैं और हरितकीचड़ की परत, जिसे सिंधुपंक (ooze) कहते हैं, बन जाती है। वर्तमान समुद्री तल का ४,८०,००,००० वर्ग मील क्षेत्र सिंधुपंक से आच्छादित है। बाली द्वीप के सानोर (Sanoer) नामक स्थान में बड़े किस्म के फ़ोरैमिनीफ़ेरा के कवच पगडंडियों और सड़कों पर बिछाने के काम आते हैं।

अधिकतर खड़िया, चूनापत्थर और संगमरमर फ़ोरैमिनीफ़ेरा के संपूर्ण कवच, अथवा उससे उत्पादित कैल्सियम कार्बोनेट से निर्मित होता है।

कैंब्रियन-पूर्व समुद्रों के तलछटों में फ़ोरैमिनीफ़ेरा का विद्यमान रहना पाया जाता है, किंतु कोयला युग (coal age), या पेंसिलवेनिअन युग (Pennsylvanian) के पूर्व इनका कोई महत्व नहीं था। आदिनूतन (Eocene) युग में फ़ोरैमिनीफ़ेरा गण आकार, रचना की जटिलता, निक्षेप की मोटाई तथा वितरण में अपनी चरम सीमा पर पहुँच गया था। हिमालय में एवरेस्ट पर्वत की २२,००० फुट ऊँचाई पर २०० फुट मोटा फ़ोरैमिनीफ़ेरीय चूना पत्थर का शैलस्तर वर्तमान है।

संपूर्ण धरा के २/३ भाग में समुद्र तलछट स्थित है और उसमें फ़ोरैमिनीफ़ेरा के जीवाश्म पाए जाते हैं। कालपरिवत्रन के साथ साथ फोरैमिनीफ़ेरा की नई जातियों का आविर्भाव हुआ और कुछ पुरानी जातियाँ विलुप्त हो गईं। अतएव किसी अलग हुए क्षेत्र के अलग होने और उसके निर्माण काल में भूवैज्ञानिक समन्वय स्थापित करने में फ़ोरैमिनीफ़ेरा बहुत ही उपयोगी सिद्ध होते हैं।

पेट्रोलियम भूविज्ञान में फ़ोरैमिनीफ़ेरा का स्थान महत्वपूर्ण है। पेट्रोलियम के लिए क्षेत्र का वेधन (drilling) करते समय विभिन्न स्तरों से प्राप्त पदार्थों को एकत्र कर प्रयोगशाला में उनकी जाँच की जाती है। यदि जाँच में किसी विशेष प्रकार के फ़ोरैमिनीफ़ेरा के जीवाश्म मिलते हैं, तो उसे यह अनुमान हो जाता है कि वेधन क्षेत्र में पेट्रोलियम विद्यमान है अथवा नहीं।

फ़ोरैमिनीफ़ैरा के कवच छोटे बिंदु के आकार से लेकर अनेक इंचों के व्यास का हो सकता है। कुछ सीमित समूह के अंतर्गत ऐसे स्पीशीज़ (species) हैं जो समुद्री अमीबों से बड़े होते हैं और काइटिनी झिल्ली या असंस्कृत (primitive) कवच से रक्षित रहते हैं। इस सरल रचना से प्रारंभ कर ऐसे स्पीशीज़ विकसित हुए हैं जिनमें असंस्कृत कवच के बालू अभ्रक, स्पंज कंटिका, अथवा अन्य तलछट पदार्थों से ढकने से, या कैल्सियम कार्बोनेट के घने जमाव के कारण गोलाकार (globular) आकृति बन गई।

ये गोलाकार कवच प्रारंभिक कोष्ठों (chambers), अथवा साधारण बहुखंडीय प्रोलॉकुलस (Proloculus) के सदृश हैं। ऐसे सरल कवच में एक विसर्पी (meandering), या घुमावदार कोष्ठ बाहर से जुड़ गया, या कुछ कोष्ठ इस प्रकार व्यवस्थित हो गए कि एक लपेटदर शुरूआत (coiled beginning) हो सके और अनेक वलयी (annular) कोष्ठ जुड़ सकें। कवच की ये ही आधारभूत रचनाएँ थीं और इन्हीं से अनेक स्पीशीज़ के चोलों (tests) का प्रादुर्भाव हुआ। किसी कवचन में कोष्ठों की संख्या एक या कई सौ हो सकती है। प्राय: अतंस्थ कोष्ठ (terminal chamber) में एक या अनेक रंध्र होते हैं और जब नया कोष्ठ जुड़ता है तब इन रध्रों से (foramina) कोष्ठ के बीच आवागमन का मार्ग बन जाता है। एक बृहद समूह के अधिकांश कोष्ठों की दीवारों में सूक्ष्म पादाभीय रंध्र पाए जाते हैं और कुछ ऐसे समूह हैं जिनमें कवच की दीवारों में विस्तृत नहर प्रणाली रहती है।

बहुत सी स्पीशीज़ के कवच कूटकों (ridges), शूलों (spines), या वृत्तस्कंधों (bosses) से अलंकृत रहते है। इस सुंदरता और जटिलता के कारण फ़ोरैमिनीफ़ेरा का अध्ययन बहुत दिनों से हो रहा है। कवचों की, आकृति और संरचना के आधार पर, निम्नलिखित चार समुदायों में विभाजित किया जा सकता है:

अधिकतर जीवित फ़ोरैमिनीफेरा कीचड़, या बालुकामय तलों, या छोटे छोटे पौधों पर रहते हैं। कुछ थोड़े समूह वेलापवर्ती (pelagie) होते हैं और साधारण गहराई में खुले समुद्र में पाए जाते हैं। तलीय फ़ोरैमिनीफ़ेरा में इतनी और इस प्रकार की गति होती है कि अधिकांश फ़ोरमिनीफ़ेरा कुछ इंच के अंदर ही जन्म से मृत्युपर्यंत गति कर पाते हैं।

जिन स्पीशीज़ में बृहद छिद्र होता है उनके कवच के जीवद्रव्य (protoplasm) में जीवाणु, कशाभिक प्रोटोज़ोआ, शैवाल के बीजाणु (spores of algae), डायटम (diatoms) तथा जैविक अपरद (detritus) पाए जाते हैं। जब छिद्र इतना लघु होता है कि उनसे होकर बड़े बड़े खाद्यकरण प्रवेश न कर सकें, तब उनका पाचन पादाभों में विद्यमान किण्वों (ferments) द्वारा होता है।

पादाभ कवच के छिद्र के समीपस्थ जीवद्रव्य से, अथवा पादाभ रध्रों से निकलते हैं और क्षीण हो जाते हैं। जहाँ अनेकों पादाभ निकलते हैं वे एकाकार हो जाते हैं, अथवा शाखामिलन (anastomese) होता है। जीवद्रव्य से निर्मित इन तंतुओं (filaments) में निरंतर प्रवाह के कारण गति होती रहती है और इस प्रवाह द्वारा खाद्य को पकड़ने और उसके पाचन का कार्य होता है तथा ठोस या तरल उत्सर्ग का उत्सर्जन (excretion) होता है। यहीं नहीं, बल्कि कवच के बाहर आच्छादित, जीवद्रव्य के सहयोग से श्वसन का कार्य भी होता है। कवच के अंदर जीवद्रव्य के प्रवाह के कारण परिसंचरण (circulation) होता है और सभी कोष्ठों में भोजन इत्यादि पहुँचता रहता है।

फ़ोरैमिनीफ़ेरा का रंग उसके कवच के रंग, घनत्व और, कुछ अंश तक, कवच की रचना पर निर्भर करता है। जब कवच की दीवार पारभासी (translucent) होती है तब जीवद्रव्य का हरा, भूरा या लाल रंग उसके अंतर्वेश (inclusion) कवच के रंग का प्रमुख कारण होता है। काइटिन (chitin) भूरा होता है और प्राय: कवच को भूरापन प्रदान करता है, अन्यथा वह श्वेत होता है। प्रवालभित्ति (coral reefs) के ईद गिर्द विविध रंगों, जैसे चीनाश्वेत, नारंगी, लाल, भूरे और हरे रंग से लेकर लैवेंडर और नीले रंग, के चमकीले स्पीशीज़ पाए जाते हैं। लैवेंडर और नीले रंग अपवर्तन के कारण होते हैं। गहरे जल में जो स्पीशीज़ आंशिक रूप से पारभासी कवचों के साथ पाए जाते हैं, वे हरे होते हैं और ऐरेनेसस कवच खोल पदार्थ का रंग ग्रहण कर लेते हैं, अथवा कणों को जोड़नेवाले सीमेंट में विद्यमान लौह लवणों के कारण लाल या भूरे दिखाई पड़ते हैं, जब कि अनेक स्पीशीज़ के चूनेदार कवच श्वेत पोर्सिलेन सदृश होते हैं। उष्ण समुद्र के छिछले जलवासी फोरैमिनीफेरा के जीवद्रव्य के अंदर ज़ोओज़थेली (Zooxanthellae), जो सहजीवी शैवाल हैं, पाए जाते हैं, किंतु उनके स्वर्णिम रंग का प्रभाव फ़ोरैमिनीफ़ेरा के रंग पर बहुत ही कम पड़ता है।

अधिकांश फ़ोरैमिनीफ़ेरा के जीवन में लैंगिक (sexual) और अलैंगिक (asexual) चक्रीय पीढ़ियाँ होती हैं, जिनसे दो प्रकार के प्राणी उत्पन्न होते हैं।

लैंगिक अवस्था में कशाभिक (flagellated) युग्मक (gametes) जोड़े आपस में मिलते हैं और समागम करते हैं और इसके फलस्वरूप युग्मनज (zygote), अथवा निषेचन अमीबा (fertilization amaeba) एक गोलाकार कवच में परिवर्तित हो जाता है। लैंगिक विधि से उत्पन्न प्राणी में कवच का प्रारंभिक काष्ठ बहुत ही सूक्ष्म होता है। अतएव वे 'सूक्ष्मगोलीय कवच' (microspheric tests) कहलाते हैं।

अलैंगिक अवस्था (Asexual phase) - उपर्युक्त सूक्ष्मगोलीय प्राणी अलैंगिक विधि से प्रजनन करता है। अलैंगिक विधि से केंद्रक का क्रमिक विभाजन होता है और उनकी संख्या पूर्वविद्यमान केंद्रक की चार गुनी हो जाती है। तत्पश्चात् प्रत्येक केंद्रक के चारों तरफ का जीवद्रव्य साधारण पिंड (common mass) से अलग हो जाता है और एककेंद्रक (mononucleate) अमीबा बनाता है। इस प्रकार उत्पन्न अमीबा के प्रारंभिक कोष्ठ बृहत् होते हैं। अतएव ये 'दीर्घगोलीय कवच' (megaspheric tests) कहलाते हैं।

जीवनचक्र के लैंगिक अथवा अलैंगिक दोनों ही अवस्थाओं में अधिकांश स्पीशीज़ में प्रजनन की गतिविधि के लिए दो-तीन दिनों की आवश्यकता होती है। नए कोष्ठ के जुड़ने के लिए एक दिन की आवश्यकता होती है और उसके अनेक दिनों बाद दूसरा कोष्ठ जुड़ता है। इन प्रोटोज़ोआ की आयु कुछ सप्ताह से लेकर एक साल या अधिक की होती है। यह स्पीशीज़ और ऋतु (season) पर निर्भर करती है और लैंगिक तथा अलैंगिक पीढ़ियों को मिलाकर जीवनचक्र के लिए अनेक सप्ताहों से लेकर दो या अधिक साल तक की आवश्यकता होती है।

एक विद्यमान फोरामिनिफेरा की बहुत सी वे जातियाँ जो एक विशेष गहराई में पाई जाती हैं, सर्वत्र उसी गहराई में मिलती हैं। पृथ्वी के इतिहास में अन्यकाल में भी इसी प्रकार की स्थितियाँ रही हैं। छिछले जल में रहनेवाली जातियों का वितरण जल के ताप के कारण प्राय: सीमित होता है। अन्य जातियाँ, ताप के अतिरिक्त अन्य बातों पर, जैसे जल की लवणता, अध:स्तर (substratum) की प्रकृति, भोजन की उपलब्धि इत्यादि, पर निर्भर करती हैं और ये बातें स्वयं जल की गहराई से प्रभावित होती हैं। इस समूह में वृद्धि और प्रजनन उपयुक्त भोज्य जीवाणुओं पर बहुत अधिक निर्भर करता है। फोरामिनिफेरा की बहुत सी जातियाँ तृण तथा घास से आच्छादित क्षेत्रों में ही सीमित होती हैं और जिस गहराई तक ये पौधे उगते हैं वह तल की प्रकृति और सूर्य विकिरण (solar radiation), जो जल के गँदलापन तथा अक्षांश (latitude) के अनुसार बदलता है, निर्भर करती है।

गहरे जल में जीवित फोरामिनिफेरा की संख्या प्रति इकाई क्षेत्र में कम होती है, किंतु छिछले जल में उनकी संख्या प्रत्येक वर्ग फुट में सैकड़ों से लेकर हजारों तक होती है।

फोरामिनिफेरा के कुछ वंश निम्नलिखित हैं :

यह समुद्र में पाए जानेवाले फोरामिनिफेरा का एक अच्छा उदाहरण है। यह समुद्र के किनारे तल में पाया जाता है। सूक्ष्मदर्शी से देखने पर यह एक छोटे घोंघे के छिलके जैसा दिखाई पड़ता है। इसका कवच कड़ा, अर्धपारदर्शी और कैल्सियमी होता है। इसमें आकृति के प्रकोष्ठ बने होते हैं। ये प्रकोष्ठ समीपवर्तीं, चिपटे और सर्पिल हाते हैं। अन्य प्रोटोज़ोआ और डायटम (diatoms) इसके भोजन हैं, जिन्हें यह कवच छिद्र से निकले बाह्य जीवद्रव्य स्तर से उत्पन्न, लंबे, पतले, शाखावत् और उलझे पादाभ द्वारा पकड़ कर लगभग कवच से बाहर ही पचा लेता है।

पॉलिस्टोमेला के जीवनचक्र में निरंतर पीढ़ी परिवर्तन होता है और उसमें केंद्रीय कोष्ठ के आकार में द्विरूपता (dimorphism) पाई जाती है।

फोरामिनिफेरा का यह वंश बहुत ही व्यापक है। ग्लोबिजराइना बुलायड्स (G. bulloids) विश्वव्यापी समुद्र के छिछले जलवासी स्पीशीज हैं, जो समुद्र के तल की कीचड़ों में, ३,००० फ़ैदम की गहराई में पाए जाते हैं। मृत प्राणियों के कवच समुद्रतल में बहुत अधिक मात्रा में इकट्ठा होकर एक प्रकार के पंक, जिसे सिंधुपंक या गलोबिजराइना सिंधु पंक (Globigerina ooze) कहते हैं, बना देते हैं। विद्यमान महासागरों का एक तिहाई तल इसी ग्लोबिजराइना सिंधुपंक से आच्छादित है। इनका कवच प्राकृतिक खड़िया का एक प्रमुख संघटक होता है।

सरल रचनावाले फोरामिनिफेरा में से माइक्रोग्रोमिया भी एक है। जीवद्रव्य पिंड के अंदर केवल एक केंद्रक (nucleus) और एक संकुचनशील रिक्तिका (vacuole) होती है, जो एक साधारण अंडाकार और काइटेनीय कवच (chitinoid shell) से घिरे हाते हैं। इस कवच (shell) के चौड़े मुख से जीवद्रव्य निकला होता है, जो लंबे, मृदुल सूक्ष्म और विकीर्णक रेटीकुलो पाडों (radiating reticulopods) का निर्माण करता है। इसमें दो कशाभिकाएँ (flagella) होती हैं, जिनकी सहायता से यह जल में तैरता है।

इसकी रचना माइक्रोग्रोमिया के सदृश होती है, किंतु यह हानिकारक परोपजीवी के रूप में मनुष्य, अथवा अन्यस्तनपोषी, की अँतड़ियों में पाया जाता है। इसका कवच नाशपाती की आकृति का और काइटिनायी होता है। कवच के एक छोर पर एक संकीर्ण छिद्र होता है, जिससे होकर जीवद्रव्य निकला होता है और शाखामिलनी रेटिकुलोपोडिया का निर्माण करता है। इसमें अलैंगिक प्रजनन द्विभाजन (binary fission) की विधि से और लैगिक प्रजनन बहुविभाजन की विधि से होता है।

इसमें छोरीय कवचछिद्र से निकला हुआ जीवद्रव्य कवच के चारों तरफ प्रवाहित होता रहता है, जिससे कवच जीवद्रव्य के अंदर आ जाता है। पादाभ (pseudopodia) विलक्षण रूप से लंबे, उलझे हुए और जालिकारूपी (reticulate) होते हैं और शिकार को पकड़ने और उनका पाचन करने का कार्य करते हैं।

फोरामिनिफेरा (Foraminifera ; /fəˌræməˈnɪfərə/ लैटिन अर्थ- hole bearers, informally called "forams") ) अथवा पेट्रोलियम उद्योग का तेल मत्कुण (oil bug), प्रोटोज़ोआ संघ के वर्ग सार्कोडिन के उपवर्ग राइज़ोपोडा का एक गण है। इस गण के अधिकांश प्राणी प्राय: सभी महासागरों और समुद्र में सभी गहराइयों में पाए जाते हैं। इस गण की कुछ जातियाँ अलवण जल में और बहुत कम जातियाँ नम मिट्टी में पाई जाती हैं। अधिकांश फ़ोरैमिनाफ़ेरा के शरीर पर एक आवरण होता है, जिसे चोल या कवच (test or shell) कहते हैं। ये कवच कैल्सीभूत, सिलिकामय, जिलेटिनी अथवा काइटिनी (chitinous) होते हैं, या बालू के कणों, स्पंज कंटिकाओं (spongespicules), त्यक्त कवचों, या अन्य मलवों (debris) के बने होते हैं। कवच का व्यास .०१ मिमी. से लेकर १९० मिमी. तक होता है तथा वे गेंदाकार, अंडाकार, शंक्वाकार, नलीदार, सर्पिल (spiral), या अन्य आकार के होते हैं।

कवच के अंदर जीवद्रव्यी पिंड (protoplasmic mass) होता है, जिसमें एक या अनेक केंद्रक होते हैं। कवच एककोष्ठी (unilocular or monothalamus), अथवा श्रेणीबद्ध बहुकोष्ठी (multilocular or polythalmus) और किसी किसी में द्विरूपी (dimorphic) होते हैं। कवच में अनेक सक्षम रध्रों के अतिरिक्त बड़े रंध्र, जिन्हें फ़ोरैमिना (Foramina) कहते हैं, पाए जाते हैं। इन्हीं फोरैमिना के कारण इस गण का नाम फ़ोरैमिनीफ़ेरा (Foraminifera) पड़ा है। फ़ोरैमिनीफ़ेरा प्राणी की जीवित अवस्था में फ़ोरैमिना से होकर लंबे धागे के सदृश पतले और बहुत ही कोमल पादाभ (pseudopoda), जो कभी कभी शाखावत और प्राय: जाल या झिल्ली (web) के समान उलझे होते हैं, बाहर निकलते हैं।

वेलापवर्ती (pelagic) फ़ोरैमिनीफ़ेरा के कवच समुद्रतल में जाकर एकत्र हो जाते हैं और हरितकीचड़ की परत, जिसे सिंधुपंक (ooze) कहते हैं, बन जाती है। वर्तमान समुद्री तल का ४,८०,००,००० वर्ग मील क्षेत्र सिंधुपंक से आच्छादित है। बाली द्वीप के सानोर (Sanoer) नामक स्थान में बड़े किस्म के फ़ोरैमिनीफ़ेरा के कवच पगडंडियों और सड़कों पर बिछाने के काम आते हैं।

Foraminifera (/fəˌræməˈnɪfərə/ fə-RAM-ə-NIH-fə-rə; Latin for "hole bearers"; informally called "forams") are single-celled organisms, members of a phylum or class of amoeboid protists characterized by streaming granular ectoplasm for catching food and other uses; and commonly an external shell (called a "test") of diverse forms and materials. Tests of chitin (found in some simple genera, and Textularia in particular) are believed to be the most primitive type. Most foraminifera are marine, the majority of which live on or within the seafloor sediment (i.e., are benthic),[2] while a smaller number float in the water column at various depths (i.e., are planktonic), which belong to the suborder Globigerinina.[3] Fewer are known from freshwater[4] or brackish[5] conditions, and some very few (nonaquatic) soil species have been identified through molecular analysis of small subunit ribosomal DNA.[6][7]

Foraminifera typically produce a test, or shell, which can have either one or multiple chambers, some becoming quite elaborate in structure.[8] These shells are commonly made of calcium carbonate (CaCO

3) or agglutinated sediment particles. Over 50,000 species are recognized, both living (6,700–10,000)[9][10] and fossil (40,000).[11][12] They are usually less than 1 mm in size, but some are much larger, the largest species reaching up to 20 cm.[13]

In modern scientific English, the term foraminifera is both singular and plural (irrespective of the word's Latin derivation), and is used to describe one or more specimens or taxa: its usage as singular or plural must be determined from context. Foraminifera is frequently used informally to describe the group, and in these cases is generally lowercase.[14]

The earliest known reference to foraminifera comes from Herodotus, who in the 5th century BCE noted them as making up the rock that forms the Great Pyramid of Giza. These are today recognized as representatives of the genus Nummulites. Strabo, in the 1st Century BCE, noted the same foraminifera, and suggested that they were the remains of lentils left by the workers who built the pyramids.[15]

Robert Hooke observed a foraminifera under the microscope, as described and illustrated in his 1665 book Micrographia:

I was trying several small and single Magnifying Glasses, and casually viewing a parcel of white Sand, when I perceiv'd one of the grains exactly shap'd and wreath'd like a Shell[...] I view'd it every way with a better Microscope and found it on both sides, and edge-ways, to resemble the Shell of a small Water-Snail with a flat spiral Shell[...][16]

Antonie van Leeuwenhoek described and illustrated foraminiferal tests in 1700, describing them as minute cockles; his illustration is recognizable as being Elphidium.[17] Early workers classified foraminifera within the genus Nautilus, noting their similarity to certain cephalopods. It was recognised by Lorenz Spengler in 1781 that foraminifera had holes in the septa, which would eventually grant the group its name.[18] Spengler also noted that the septa of foraminifera arced the opposite way from those of nautili and that they lacked a nerve tube.[19]

Alcide d'Orbigny, in his 1826 work, considered them to be a group of minute cephalopods and noted their odd morphology, interpreting the pseudopodia as tentacles and noting the highly reduced (in actuality, absent) head.[20] He named the group foraminifères, or "hole-bearers", as members of the group had holes in the divisions between compartments in their shells, in contrast to nautili or ammonites.[14]

The protozoan nature of foraminifera was first recognized by Dujardin in 1835.[18] Shortly after, in 1852, d'Orbigny produced a classification scheme, recognising 72 genera of foraminifera, which he classified based on test shape—a scheme that drew severe criticism from colleagues.[17]

H.B. Brady's 1884 monograph described the foraminiferal finds of the Challenger expedition. Brady recognized 10 families with 29 subfamilies, with little regard to stratigraphic range; his taxonomy emphasized the idea that multiple different characters must separate taxonomic groups, and as such placed agglutinated and calcareous genera in close relation.

This overall scheme of classification would remain until Cushman's work in the late 1920s. Cushman viewed wall composition as the single most important trait in classification of foraminifera; his classification became widely accepted but also drew criticism from colleagues for being "not biologically sound".

Geologist Irene Crespin undertook extensive research in this field, publishing some ninety papers—including notable work on foraminifera—as sole author as well as more than twenty in collaboration with other scientists.[21]

Cushman's scheme nevertheless remained the dominant scheme of classification until Tappan and Loeblich's 1964 classification, which placed foraminifera into the general groupings still used today, based on microstructure of the test wall.[17] These groups have been variously moved around according to different schemes of higher-level classification. Pawlowski's (2013) use of molecular systematics has generally confirmed Tappan and Loeblich's groupings, with some being found as polyphyletic or paraphyletic; this work has also helped to identify higher-level relationships among major foraminiferal groups.[22]

"Monothalamids" (paraphyletic)

"Monothalamids"

Tubothalamea"Monothalamids"

Globothalamea"Textulariida" (paraphyletic)

Phylogeny of Foraminifera following Pawlowski et al. 2013.[22] The monothalamid orders Astrorhizida and Allogromiida are both paraphyletic.The taxonomic position of the Foraminifera has varied since Schultze in 1854,[23] who referred to as an order, Foraminiferida. Loeblich (1987) and Tappan (1992) reranked Foraminifera as a class[24] as it is now commonly regarded.

The Foraminifera have typically been included in the Protozoa,[25][26][27] or in the similar Protoctista or Protist kingdom.[28][29] Compelling evidence, based primarily on molecular phylogenetics, exists for their belonging to a major group within the Protozoa known as the Rhizaria.[25] Prior to the recognition of evolutionary relationships among the members of the Rhizaria, the Foraminifera were generally grouped with other amoeboids as phylum Rhizopodea (or Sarcodina) in the class Granuloreticulosa.

The Rhizaria are problematic, as they are often called a "supergroup", rather than using an established taxonomic rank such as phylum. Cavalier-Smith defines the Rhizaria as an infra-kingdom within the kingdom Protozoa.[25]

Some taxonomies put the Foraminifera in a phylum of their own, putting them on par with the amoeboid Sarcodina in which they had been placed.

Although as yet unsupported by morphological correlates, molecular data strongly suggest the Foraminifera are closely related to the Cercozoa and Radiolaria, both of which also include amoeboids with complex shells; these three groups make up the Rhizaria.[26] However, the exact relationships of the forams to the other groups and to one another are still not entirely clear. Foraminifera are closely related to testate amoebae.[30]

The most striking aspect of most foraminifera are their hard shells, or tests. These may consist of one of multiple chambers, and may be composed of protein, sediment particles, calcite, aragonite, or (in one case) silica.[24] Some foraminifera lack tests entirely.[32] Unlike other shell-secreting organisms, such as molluscs or corals, the tests of foraminifera are located inside the cell membrane, within the protoplasm. The organelles of the cell are located within the compartment(s) of the test, and the hole(s) of the test allow the transfer of material from the pseudopodia to the internal cell and back.[33]

The foraminiferal cell is divided into granular endoplasm and transparent ectoplasm from which a pseudopodial net may emerge through a single opening or through many perforations in the test. Individual pseudopods characteristically have small granules streaming in both directions.[34] Foraminifera are unique in having granuloreticulose pseudopodia; that is, their pseudopodia appear granular under the microscope; these pseudopodia are often elongate and may split and rejoin each other. These can be extended and retracted to suit the needs of the cell. The pseudopods are used for locomotion, anchoring, excretion, test construction and in capturing food, which consists of small organisms such as diatoms or bacteria.[35][33]

Aside from the tests, foraminiferal cells are supported by a cytoskeleton of microtubules, which are loosely arranged without the structure seen in other amoeboids. Forams have evolved special cellular mechanisms to quickly assemble and disassemble microtubules, allowing for the rapid formation and retraction of elongated pseudopodia.[24]

In the gamont (sexual form), foraminifera generally have only a single nucleus, while the agamont (asexual form) tends to have multiple nuclei. In at least some species the nuclei are dimorphic, with the somatic nuclei containing three times as much protein and RNA than the generative nuclei. However, nuclear anatomy seems to be highly diverse.[36] The nuclei are not necessarily confined to one chamber in multi-chambered species. Nuclei can be spherical or have many lobes. Nuclei are typically 30-50 µm in diameter.[37]

Some species of foraminifera have large, empty vacuoles within their cells; the exact purpose of these is unclear, but they have been suggested to function as a reservoir of nitrate.[37]