ar

الأسماء في صفحات التنقل

Nelson’s antelope squirrels are omnivorous and active foragers. They feed primarily on insects, green vegetation, and seeds, but will sometimes also feed on small vertebrates. With regards to the latter, the San Joaquin antelope squirrel consumes rodents, lizards and members of its own species as carrion. Their diet preferences are largely dependent on the amount of moist vegetation available. With respect to green material, red-stemmed filaree (Erodium cicutarium) and the red brome (Bromus rubens) are preferred. Other food sources include the ephedra, a species of clover and locoweed. When moist food becomes very scarce turpine weed is eaten. A preference for a particular type of insect has not been documented. The San Joaquin squirrel eats seeds only when easily obtainable green material and insects are not available.

Nelson’s antelope squirrel assumes a distinctive posture while feeding. It squats on its rear limbs with the tail cocked behind the back and holds its food in the forepaws. Its enlarged incisors and abrasive cheek teeth help in breaking down food.

The Nelson’s ground squirrel does not live near a source of water and so water does not constitute a great part of its diet. It can be inferred that its principal source of moisture is from the vegetation eaten. Although it accepts large amounts of water in laboratory conditions, it can survive for seven months in the shade, without water.

Animal Foods: reptiles; carrion ; insects

Plant Foods: leaves; seeds, grains, and nuts

Foraging Behavior: stores or caches food

Primary Diet: carnivore (Eats terrestrial vertebrates, Insectivore , Scavenger ); herbivore (Folivore , Granivore ); omnivore

Nelson's antelope squirrels are preyed upon by mid-sized predators, and serve as host to varius endoparasites and ectoparasites. They are hosts to cestodes (Hymenopelis citelli), nematodess (Spirura infundibuliformis and Physaloptera spinicauda), and also acanthocephalans (Moniliformes dubius). The ectoparasites they are host to include fleas (Siphonaptera) and ticks (Ixodes). Nelson's antelope squirrels have a symbiotric relationship with kangaroo rats Dipodomys deserti, taking refuge in their burrows. They further impact their habitat by continuing to burrow. Because they are seed collectors, they also disperse seeds in their environment.

Ecosystem Impact: disperses seeds; creates habitat

Mutualist Species:

Commensal/Parasitic Species:

Nelson’s antelope squirrels do not generally live close to human settlements. They may contribute to controlling insect populations by eating them and they may help to disperse the seeds they gather and store.

In laboratory conditions, Nelson's antelope squirrels have been positive for western equine encephalomyelitis, St. Louis encephalitis, Powassan virus, and Modoc virus. However, there is no documented instance their role in spreading disease to humans or domestic animals.

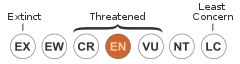

Nelson’s, or San Joaquin, antelope squirrels are classified as endangered on the IUCN Red List. According to the California Department of Fish and Game, the biggest threat to Nelson’s antelope squirrels is habitat destruction due to crop cultivation and urbanization. Excessive grazing by livestock affects these squirrels and also causes soil erosion. Uses of rodenticides and insecticides, which destroy prey populations, negatively impact Nelson’s antelope squirrels. The Endangered Species Recovery Program (2006) of California has suggested a list of conservation measures that stress the importance of land use practices and management strategies. A detailed conservation program for San Joaquin antelope squirrels includes determining habitat management, protecting additional habitat in surrounding areas of the squirrel’s range, habitat enhancement in areas like Kern County, and reintroduction to protected areas, such as Pixley National Wildlife Refuge.

US Federal List: no special status

CITES: no special status

State of Michigan List: no special status

The main senses used by the Nelson's antelope squirrels are hearing and olfaction, but the species also relies on vision and will scan its environment before making the decision to fully exit its burrow. Olfaction is used to detect danger, to find food and to communicate. Nelson's antelope squirrels also twitch their tails rapidly, in fore and aft movements when frightened or excited.

The Nelson’s antelope squirrel gives out alarm calls, which are indicative of altruistic behavior as it compromises the safety of the individual. These calls are in the form of trills that are low-pitched and are characteristic of antelope squirrels that live in closed habitats. In fact, the call is accomplished by a convulsive motion of its body rather than by vocal stress. The female uses this call to communicate with her family when she is weaning.

Communication Channels: visual ; acoustic ; chemical

Perception Channels: tactile ; acoustic ; chemical

The genus Ammospermophilus has a rich fossil record. Its divergence can be dated to the Miocene as post-Pleistocene fossils resembling Nelson’s antelope squirrels have been found near Kern County, California. They are thought to have invaded the area over the passes of southern Sierra Nevada and Tehachapi mountains. Due to the change in the moisture levels to less arid conditions in the corridor between Mojave Desert and San Joaquin valley, Nelson’s antelope squirrels became restricted to the San Joaquin valley.

The distribution of Ammospermophilus nelsoni is restricted to the floor of the southern San Joaquin Valley, California, the Cuyama and Panoche valleys in San Luis Obispo County, and the Carrizo and Elkhorn Plains of the United States. The species is Nearctic and endemic to the above range.

Biogeographic Regions: nearctic (Native )

Nelson's antelope squirrels are found in hot deserts that comprise the Lower Sonoran life zone. Lower Sonoran deserts of North America include areas in Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, and California. Nelson's antelope squirrels are found in arid grasslands and shrub lands. They have been recorded in areas where shrub cover ranges from light to medium density and ranges from xerophytic, alkali desert scrub and annual grassland receiving less than 15 cm annual precipitation, to halophytic, alkali desert scrub and annual grassland receiving 18 to 23 cm of annual precipitation. Nelson's antelope squirrels prefer alkaline, loamy soils from 50 to 1100 meters elevation. Nelson’s antelope squirrels depend on kangaroo rat burrows, so areas they inhabit may be limited to areas with kangaroo rat popuations.

Range elevation: 50 to 1100 m.

Habitat Regions: temperate ; terrestrial

Terrestrial Biomes: desert or dune

Nelson's antelope squirrels usually live for less than a year in the wild because of high infant and young mortality rates. They have been documented to live for about 4 years in captivity, with the longest captive lifespan being 5.7 years. Adult mortality rate is 80% and the average lifespan is 8 months.

Range lifespan

Status: captivity: 5.7 (high) years.

Average lifespan

Status: wild: 8 months.

Average lifespan

Status: captivity: 4 years.

Nelson's antelope squirrels have fusiform bodies, small, rounded ears, short legs, and short tails. The dorsal head and neck and the outer surfaces of the legs are a dull yellowish-brown or buffy-tan. The tail has thick fringes of hair and the underside is light grey to white. A distinctive light-colored stripe runs along the side of the body from behind the shoulder to the rump. Males are slightly larger than females, with total length of males ranging from 234 to 267 mm (average 249 mm). Female length ranges from 230 to 256 mm (average 238 mm). Nelson's antelope squirrels have distinct summer and winter pelages, with the autumn or winter pelage being darker than the summer pelage.

Nelson's antelope squirrels can be distinguished from white-tailed antelope squirrels by its larger size and grey coloring of the pelage. Nelson's antelope squirrels have wider zygomatic arches, more inflated auditory bullae, and larger nasal bones. They also have larger upper incisors and first upper molars.

Range mass: 142 to 179 g.

Average mass: 155 g.

Range length: 230 to 267 mm.

Average length: 249 mm.

Average basal metabolic rate: 0.8 cm3.O2/g/hr.

Other Physical Features: endothermic ; homoiothermic; bilateral symmetry

Sexual Dimorphism: male larger

Nelson's antelope squirrels employ a variety of techniques to guard against predators. The complex burrow systems serve as protection against predators. When emerging from a burrow, they exercise extreme caution and do not exit quickly. They rely on olfaction and use this capability while foraging and fleeing danger. They use characteristic alarm calls to communicate danger and may also rely on the warning calls of birds like horned larks and white-crowned sparrows for detection of predators. Nelson's antelope squirrels use their surroundings while evading predators. They use shrubs and burrows of kangaroo rats as sites of refuge. Their buffy or tan pelage make them difficult to see in their arid habitats. When foraging, these squirrels move close to the ground in a very distinctive manner, by a series of short, rapid jumps. American badgers are the most important predators of these squirrels. They dig into the burrows to prey on young and adults. They are also eaten by coyotes (Canis latrans) and (kit foxes Vulpes macrotis).

Known Predators:

Anti-predator Adaptations: cryptic

Nelson's antelope squirrels have a promiscuous mating system in which females and males mate with multiple partners. Not much is known about specific mating behaviors, but an interesting observation was made regarding mate searching behavior. Mates are typically found within the home range, but there have been instances of females travelling up to 1 km from their home range in search of a mate. Mate guarding and mate defense have not been observed in Nelson's antelope squirrels.

Mating System: polygynandrous (promiscuous)

The breeding season of Nelson's antelope squirrels extends from late winter to early spring and this species breeds once annually. Males achieve reproductive maturity earlier than females. Brood size varies from 6 to 11 young; with the average being 9. The average gestation period is 26 days. Females give birth to offspring in burrows. The young come above ground approximately on the 30th day after birth. Weaning can start or be completed before the young emerge from their burrow, but this is highly variable. Females wean the young by refusing to nurse and visiting the burrow less frequently.

Breeding interval: Nelson's antelope squirrels breed once annually.

Breeding season: Nelson's antelope squirrels breed from late winter to early spring.

Range number of offspring: 6 to 11.

Average number of offspring: 9.

Range gestation period: 25 to 30 days.

Average gestation period: 26 days.

Range weaning age: 30 (high) days.

Average weaning age: 15 days.

Range time to independence: 3 to 4 weeks.

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female): 377 days.

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male): 377 days.

Key Reproductive Features: iteroparous ; seasonal breeding ; gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); sexual ; viviparous

Nelson's antelope squirrel young are born in an altricial state. Males do not play a large role in caring for the young, as females perform all activities of nursing and weaning. When weaning, the female distances herself from the young and does not respond even when young make attempts to nurse. The female maintains contact with the young by visiting them sometimes or by just using calls to communicate. In captivity, at times when foraging opportunities were limited, instances of cannibalism have been observed.

Parental Investment: altricial ; female parental care ; pre-fertilization (Provisioning, Protecting: Female); pre-hatching/birth (Provisioning: Female, Protecting: Female); pre-weaning/fledging (Provisioning: Female, Protecting: Female)

L'esquirol antílop de Nelson (Ammospermophilus nelsoni) és una espècie de rosegador de la família dels esciúrids. És endèmic de Califòrnia (Estats Units). S'alimenta de vegetació verda, insectes i llavors d'herbes i fòrbies. El seu hàbitat natural són les zones de sòl herbós o amb pocs arbustos. Està amenaçat pel desenvolupament agrícola, l'expansió urbana i la prospecció de petroli i gas.[1]

Aquest tàxon fou anomenat en honor del naturalista i etnòleg estatunidenc Edward William Nelson.[2]

L'esquirol antílop de Nelson (Ammospermophilus nelsoni) és una espècie de rosegador de la família dels esciúrids. És endèmic de Califòrnia (Estats Units). S'alimenta de vegetació verda, insectes i llavors d'herbes i fòrbies. El seu hàbitat natural són les zones de sòl herbós o amb pocs arbustos. Està amenaçat pel desenvolupament agrícola, l'expansió urbana i la prospecció de petroli i gas.

Aquest tàxon fou anomenat en honor del naturalista i etnòleg estatunidenc Edward William Nelson.

Der Nelson-Antilopenziesel oder San-Joaquin-Antilopenziesel (Ammospermophilus nelsoni) ist eine Hörnchenart aus der Gattung der Antilopenziesel (Ammospermophilus). Er kommt endemisch im San Joaquin Valley im südlichen Kalifornien vor. Benannt wurde die Art nach Edward William Nelson.

Der Nelson-Antilopenziesel erreicht eine Kopf-Rumpf-Länge von etwa 23 bis 27 Zentimetern und eine Schwanzlänge von 6,6 bis 7,8 Zentimetern bei einem Gewicht von etwa 150 Gramm.[1] Die Rückenfärbung ist gelblich bis braun-sandfarben und an beiden Körperseiten zieht sich eine einzelne helle Linie parallel zur Wirbelsäule. Die Bauchseite ist weiß bis cremefarben gefärbt. Der Schwanz ist oberseits sandfarben-grau und unterseits creme-weiß.[1]

Der Nelson-Antilopenziesel kommt endemisch im San Joaquin Valley im Süden Kaliforniens vor.[1] Dabei beschränkt sich das Vorkommen auf den zentralen und westlichen Teil des Valleys und greift in die benachbarten Bereiche des Inneren Küstengebirges in den Bereichen der Cuyama Valley, Panoche Valley, Carrizo Plain und Elkhorn Plain über.[2][3] Die Höhenverbreitung reicht dabei von 50 bis etwa 1100 Meter in der Temblor Range, wobei die Tiere oberhalb von 800 Meter selten sind.[2] Signifikante Vorkommen beschränken sich auf den Westen des Kern County in den Elk Hills sowie auf den Carrizo und Elkhorn Plains, im nördlichen Teil kommen die Tiere in geringer Dichte in den Panoche und Kettleman Hills vor.[2]

Der Nelson-Antilopenziesel lebt in flachen und trockenen Talregionen mit Hängen von weniger als 10 bis 14° Steigung. Die Vegetation besteht aus spärlichem Grasland mit vereinzelten Büschen, der Boden ist lehmig bis sandig und kiesig, der sehr hart und trocken ist.

Die Tiere sind tagaktiv und im gesamten Jahr anzutreffen, Ruhephasen legen sie in Perioden extremer Hitze ein und häufig halten sie sich im Schatten von Pflanzen und Steinen auf, um abzukühlen. Aufgrund ihrer Färbung sind sie sehr gut an die Wüste angepasst und obwohl sie vor allem am Boden leben, sind in der Lage, auf Büsche zu klettern. Sie ernähren sich vor allem von grünen Pflanzenteilen sowie von Pflanzensamen, die sie in ihren Backentaschen sammeln. Je nach Saison stellen Aas und Insekten ebenfalls einen bedeutsamen Anteil der Nahrung dar.[1] Die Tiere leben in flachen und teilweise komplexen Bauen mit mehreren Ausgängen, wobei sie in der Regel verlassene Baue von Kängururatten übernehmen.[1] Die Dichte der Tiere ist in der Regel klein aufgrund der trockenen Habitate, innerhalb der Kolonien kann es jedoch durch die Grabaktivität der Antilopenziesel und anderer Kleinsäuger zu einer deutlichen Bodenverbesserung kommen. Der Aktivitätsradius umfasst geschlechtsunabhängig eine Fläche von etwa 4,4 Hektar. Die Kommunikation erfolgt über kurze und verglichen mit den Rufen anderer Antilopenziesel tiefe Pfiffe, die als Alarmrufe genutzt werden. Ansonsten sind die Tiere sehr leise und geben nur leise Rufe ab. Die Fortbewegung erfolgt über ein Laufen mit über dem Rücken aufgerolltem Schwanz, bei dem die Tiere schnell vorwärts und rückwärts huschen und bei potenziell Gefahr oder Störung durch Laute bewegungslos verharren.[1]

Die Paarungszeit findet im späten Winter und im Frühjahr statt. Die Jungtiere werden im März in den Bauen nach einer Tragzeit von 26 Tagen geboren, wobei ein Wurf aus sechs bis elf, im Durchschnitt 9, Jungtieren besteht. Die Jungtiere verlassen den mütterlichen Bau im April, wenn es durch die Regenfälle des Frühjahrs zu einem vermehrten Pflanzenwachstum kommt.[1] Die Mortalität ist sehr hoch, wobei mehr 80 % der Tiere im ersten Jahr versterben. Die wichtigsten Fressfeinde sind der Silberdachs (Taxidea taxus), Füchse, Kojoten und Greifvögel.[1]

Der Nelson-Antilopenziesel wird als eigenständige Art innerhalb der Gattung der Antilopenziesel (Ammospermophilus) eingeordnet, die aus fünf Arten besteht.[4][1] Die wissenschaftliche Erstbeschreibung als Spermophilus nelsoni stammt von Clinton Hart Merriam aus dem Jahr 1893 anhand von Individuen aus der Umgebung von Tipton, Tulare County, im San Joaquin Valley in Kalifornien.[4][3] 1909 wurde die Art durch Marcus Ward Lyon und Wilfred Hudson Osgood in die bereits 1862 von Merriam eingerichtete Gattung Ammospermophilus überstellt.[3] Eine enge Verwandtschaft soll zum Texas-Antilopenziesel (Ammospermophilus interpres) bestehen.[4]

Innerhalb der Art werden neben der Nominatform keine weiteren Unterarten unterschieden.[1]

Der Nelson-Antilopenziesel wird von der International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) als bedroht (endangered) eingestuft. Begründet wird dies durch das sehr kleine Verbreitungsgebiet von weniger als 5.000 km2, die starke Fragmentierung des Lebensraums und zunehmende Verschlechterung der Lebensraumbedingungen.[2] Die Hauptbedrohungen für die Arte gehen von einer Umwandlung der Lebensräume in landwirtschaftliche Flächen sowie der Verbreitung von Neophyten mit dichtem Pflanzenwuchs aus. Die Art wird nicht bejagt und gilt nicht als Agrarschädling.[1]

Die Bestandsgröße ist unbekannt, nach Schätzungen von drei bis zehn Tieren pro Hektar und einer Fläche von etwa 41.000 Hektar wird auf eine Mindestgröße der Populationen von 124.000 bis 413.000 geschätzt. Die Art ist häufig im Carrizo Plain National Monument anzutreffen.[2]

Der Nelson-Antilopenziesel oder San-Joaquin-Antilopenziesel (Ammospermophilus nelsoni) ist eine Hörnchenart aus der Gattung der Antilopenziesel (Ammospermophilus). Er kommt endemisch im San Joaquin Valley im südlichen Kalifornien vor. Benannt wurde die Art nach Edward William Nelson.

The San Joaquin antelope squirrel or Nelson's antelope squirrel (Ammospermophilus nelsoni), is a species of antelope squirrel, in the San Joaquin Valley of the U.S. state of California.

The San Joaquin antelope squirrel is found in the San Joaquin Valley, including slopes and ridge tops along the western edge of the valley.[2] It is endemic to the region, and is found in a much smaller range today than it originally inhabited. Since the San Joaquin Valley fell under heavy agricultural cultivation, habitat loss combined with rodenticide use has reduced the squirrels numbers enough that it is now listed as a threatened species.

Most of today's remaining San Joaquin antelope squirrels can be found in the Carrizo Plain, where their original habitat remains undisturbed. The squirrels live in small underground familial colonies on sandy, easily excavated grasslands in isolated locations in San Luis Obispo and Kern Counties. Common vegetation associated with the squirrel includes Atriplex and Ephedra, and some junipers.[3] The binomial of this species commemorates the American naturalist Edward William Nelson.

The San Joaquin antelope squirrel is dull yellowish-brown or buffy-clay in color on upper body and outer surfaces of the legs with a white belly and a white streak down each side of its body in the fashion of other antelope squirrels.[2] The underside of the tail is a buffy white with black edges.[2] Males are approximately 9.8 inches and females are approximately 9.4 inches in length.[2]

Studies by Hawbecker provide abundant information on breeding and the life cycle of Nelson's antelope squirrel.[3][4][5] They breed in late winter to early spring and have nearly all their young in March.[5] Once pregnant, gestation lasts a little less than a month.[3] The young do not emerge from their dens until approximately the first week of April.[4] Nelson's antelope squirrel has only one breeding season, which is timed appropriately so that the young are born during the time of year when green vegetation is the most abundant.[4]

Weaning is thought to start or be completed even before the young emerge.[3] Once above ground, young are seen foraging for food independently.[3] During the weaning period, the mother feeds alone and ignores any attempt of the young trying to nuzzle or nurse from her.[3] A mother will sometimes spend the night in a different den if necessary.[3] By early to mid-May the young squirrels have had their juvenile pelage for some time and begin to show the changes into adult pelage.[3] By summer, the adult pelage is present.[3] Once an individual has reached adulthood it is difficult to tell differences in age.[4] Nelson's antelope squirrel is a short-lived species that often does not survive to a year.[4] However, several individuals have been observed to live more than four years in the wild.[4]

Colonies have about six or eight individuals, however these individuals are not distributed evenly across their range.[6] There is usually about 1 per hectare.[7] Nelson's antelope squirrel prefers deep, rich soil types since they are easy to dig through in both winter and summer temperatures.[5][8] Although these squirrels may dig for food, they do not make their own burrows. Instead they claim abandoned Dipodomys (kangaroo rats) burrows as their own.[5] Both males and females have the same size home range of about 4.4 hectare.[4] Of course, there are areas of concentration within this range where the squirrels spend the majority of their time.

It is omnivorous, feeding on seeds, green vegetation, insects, and dried animal matter.[7] It occasionally caches food. Redstem fialree (Erodium cicutarium) and brome grass (Bromus rubens) are important food items for the squirrels.[5] However, their diet may differ depending on the time of day or time of year. Green vegetation is the most common diet type from December to mid-April because it is the most abundant during this period.[3] Likewise, insects make up more than 90% of the squirrel's diet from mid-April to December because they are more abundant.[3] Although seeds are available for most of the year, it is not the preferable diet of the squirrels.[3] They will choose insects or green vegetation when available over seeds, even if the seeds are more abundant and easier to access.[3] Some speculate that this could be due to the higher amount of water in insects and green vegetation, which would be necessary for the species to survive in such a hot, dry climate.[3] Unfortunately for the Nelson's antelope squirrel, there is not an abundant water source nearby.[8] Under laboratory conditions, the squirrels readily accept water.[8] However, they can also survive at least 7 months in the shade without water.[8] At the end of 7 months they appeared relatively healthy and not at all emaciated.[8]

Nelson's antelope squirrels are social animals.[7] When individually taken out of their home range and released in an unknown area, they seem helpless and confused.[8] They do not expend much energy throughout the day because of the extreme temperatures in their environment.[5] In fact, when in the direct sunlight, a temperature of 31-32 °C can kill them.[4] Therefore, there is little activity from the squirrels during the heat of the day. Although there is no evidence of hibernation, the squirrels are not bothered by the cold and can survive temperatures below freezing, in their burrows.[4] They are not early risers and are usually not seen until after sunrise, however it does forage in the morning and evening, avoiding the midday heat.[7][8] Around noon the squirrels disappear into their burrows and are not seen again until about 2 pm at the earliest.[7] On moderate days, the squirrels will take their time foraging, in contrast to bringing as much food back to their burrows as quickly as possible on hot or cold days.[5] The squirrels are also known to fully stretch out and roll over in the dust on the ground. These dust baths appear to be very enjoyable activities for the squirrels and may also be used to prevent infestation of parasites.[9]

Nelson's antelope squirrels are cautious when emerging from their burrows.[7] They have a specific route that they follow when foraging for food. If danger seems near, they will run into a burrow along their foraging route to get to safety.[5] They move quickly and do not spend much time in one place.[3] They are particular about what they choose to eat and very rarely even waste time to pick up food they are not interested in.[2] There are other features in addition to their quick movements that help keep them from danger. They whitish color of the underside of their tail can be seen when they run. The squirrels will curl their tail forward over their back and flick and twitch it back and forth as it runs.[7] This movement can present the illusion of thistledown fluttering in the wind, which could be ignored by any potential predators.[7]

To further help prevent predation, the Nelson's antelope squirrel has an alarm call. These alarm calls are not loud, but associated with convulsive body movements.[6] Horned larks and the white-crowned sparrow also aid in predator detection.[5] Squirrels will listen to alarm calls given by these two birds. The badger (Taxidea taxus) is a main predator of Nelson's antelope squirrel and will destroy burrows to get its meal.[2] Coyotes (Canis latrans) and San Joaquin Valley Kit Fox (Vulpes macrotis mutica) are also known to consume the squirrels, but they are not a main part of their diet.[5][10]

Increasing agriculture and urban development is an increasing problem for Nelson's antelope squirrel.[2][11][12] This species will not colonize cultivated land. Therefore, an increase in agriculture land is taking away their habitat and leaving them with no alternative. Grazing livestock further destroys what habitat may be left, and exotic plants are able to take over native grasses that the squirrel forages upon and relies on for shade and cover.[12] Also, pesticide drift from nearby agricultural fields encroaches in on the existing squirrel habitat.[11] Not only are these practices affecting the population of the Nelson's antelope squirrel, but they are also causing problems for other native animal and plant species in the San Joaquin Valley. Native plant species such as the kern mallow, San Joaquin woolly threads, California jewelflower, and Bakersfield cactus are all federally endangered plant species that are being outcompeted by invasive plant species.[12] Many invasive plants grow in very dense patches. These dense patches are not adequate habitats for Nelson's antelope squirrel and many other San Joaquin Valley Species.

There have been attempts to manage the invasive species and other anthropogenic causes to species decline in the San Joaquin Valley.[2][11][12][13] Prescribed burns are one option to control invasive plant species, however this method can cause native species to also be killed and can be expensive.[12] Studies determining the effects of cattle grazing on the land are also being done so that plans can be developed to reduce the impact on the land. Suggestions of using prescribed grazing to help reduce the growth of non-native species in the valley.[12]

Other control efforts include chemical and mechanical treatments, however these too can be time consuming and expensive, especially for large areas.[12] Also, the use of herbicides could potentially negatively affect species in the San Joaquin Valley if there are significant winds that spread the chemicals.[12] The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) has a recovery plan dated 1998 that includes the ideas of using Safe Harbor Agreements (SHA's) under Section 10 of the Endangered Species Act.[13] This could potentially begin a relationship between the USFWS and the farm landowners to help determine the best compromise in order to manage the endangered species of the valley.

A multispecies approach to conservation is important because of the increasing number of native species becoming threatened and endangered in the San Joaquin Valley. Management on an ecosystem level would allow the role of all the species to be taken into account. Also, an increase in awareness and education of the public around the Valley may further help increase funding for conservation and management plans. Monitoring and studying of the species is needed to determine just how threatened the species is and what needs to be done to reestablish stable populations in the valley.[2][12]

Unfortunately, most information found on the Nelson's antelope squirrel discuss the problems and reasons of declines, but do not give much insight on the potential recovery of the species. Even in 1918, Grinnell and Dixon believed it to only be a matter of time before the species faces extinction.[7]

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires |journal= (help). The San Joaquin antelope squirrel or Nelson's antelope squirrel (Ammospermophilus nelsoni), is a species of antelope squirrel, in the San Joaquin Valley of the U.S. state of California.

Ammospermophilus nelsoni Ammospermophilus generoko animalia da. Karraskarien barruko Xerinae azpifamilia eta Sciuridae familian sailkatuta dago.

Ammospermophilus nelsoni Ammospermophilus generoko animalia da. Karraskarien barruko Xerinae azpifamilia eta Sciuridae familian sailkatuta dago.

Ammospermophilus nelsoni

L'écureuil-antilope de San Joaquin (Ammospermophilus nelsoni) est une espèce de mammifères rongeurs de la famille des Sciuridae, endémique de la vallée de San Joaquin, dans l'état de Californie aux États-Unis.

Il citello antilope di Nelson o di San Joaquin (Ammospermophilus nelsoni (Merriam, 1893)) è uno scoiattolo appartenente al genere dei citelli antilope (Ammospermophilus). È endemico della valle di San Joaquin nel sud della California. Il suo nome commemora Edward William Nelson.

Il citello antilope di Nelson raggiunge una lunghezza testa-tronco di circa 23-27 centimetri, ai quali si aggiungono 6,6-7,8 centimetri di coda, e un peso di circa 150 grammi.[2] Il colore del dorso va dal giallastro al marrone-sabbia; su entrambi i lati del corpo corre una singola linea chiara parallela alla colonna vertebrale. Il lato ventrale è di colore da bianco a crema. La coda è grigio-sabbia nella parte superiore e bianco-crema su quella inferiore.[2]

Il citello antilope di Nelson è endemico della valle di San Joaquin nel sud della California.[2] La sua presenza è limitata alla parte centrale e occidentale della valle e si estende fino alle aree limitrofe del versante interno della Catena Costiera nelle zone delle valli di Cuyama e Panoche e delle pianure di Carrizo e Elkhorn.[1][3] La distribuzione altitudinale varia da 50 a circa 1100 metri sulla Temblor Range, sebbene gli esemplari siano rari sopra gli 800 metri.[1] Popolazioni consistenti si trovano nella parte occidentale della contea di Kern sulle Elk Hills e nelle pianure di Carrizo e Elkhorn; più a nord se ne trovano a bassa densità sulle Panoche e Kettleman Hills.[1]

Il citello antilope di Nelson vive in regioni caratterizzate da valli pianeggianti e asciutte con pendenze inferiori a 10-14°, vegetazione costituita da prati radi con cespugli isolati e terreno da limoso a sabbioso e ghiaioso, molto duro e secco.

I citelli sono diurni e attivi in ogni periodo dell'anno; riposano nei periodi di caldo estremo e spesso stanno all'ombra di piante e sassi per rinfrescarsi. Grazie alla loro colorazione, si adattano molto bene alla vita nel deserto e, sebbene vivano principalmente a terra, sono in grado di arrampicarsi sui cespugli. Si nutrono principalmente di parti verdi delle piante e di semi che raccolgono nelle tasche guanciali. A seconda della stagione, anche le carogne e gli insetti rappresentano una parte significativa della dieta.[2] Questi animali vivono in tane poco profonde e talvolta complesse, dotate di diverse uscite, per cui di solito occupano le tane abbandonate dei ratti canguro.[2] A causa dell'aridità degli habitat in cui vivono, la loro densità è solitamente bassa, ma all'interno delle colonie l'attività di scavo e movimento del terreno ad opera dei citelli antilope e di altri piccoli mammiferi può portare ad un significativo miglioramento della qualità del suolo. Il raggio di attività, indipendentemente dal sesso, copre un'area di circa 4,4 ettari. La comunicazione avviene tramite fischi brevi e profondi rispetto a quelli di altri citelli antilope, che vengono utilizzati come richiami di allarme. Altrimenti, questi animali sono molto silenziosi ed emettono solo richiami delicati. Si spostano correndo velocemente avanti e indietro con la coda arrotolata sul dorso, rimanendo immobili in caso di potenziale pericolo o se disturbati da suoni improvvisi.[2]

La stagione degli amori ha luogo a fine inverno e primavera. I piccoli nascono nella tana a marzo dopo un periodo di gestazione di 26 giorni; ogni cucciolata è costituita da un numero variabile da sei a undici piccoli, mediamente nove. I giovani lasciano la tana materna ad aprile, quando le piogge primaverili portano ad un aumento della crescita delle piante.[2] Il tasso di mortalità è molto alto: più dell'80% dei citelli muore durante il primo anno di vita. Tra i predatori principali vi sono il tasso americano (Taxidea taxus), le volpi, i coyote e i rapaci.[2]

Il citello antilope di Nelson viene classificato come specie indipendente all'interno del genere Ammospermophilus, che comprende quattro specie.[4][2] La prima descrizione scientifica come Spermophilus nelsoni venne effettuata nel 1893 da Clinton Hart Merriam sulla base di individui provenienti dalla zona di Tipton, contea di Tulare, nella valle di San Joaquin, in California.[4][3] Nel 1909 la specie venne trasferita da Marcus Ward Lyon e Wilfred Hudson Osgood nel genere Ammospermophilus, istituito da Merriam nel 1862.[3] La specie sembra essere strettamente imparentata con il citello antilope del Texas (Ammospermophilus interpres).[4]

Oltre alla forma nominale, non ne vengono riconosciute sottospecie.[2]

Il citello antilope di Nelson viene classificato dall'Unione internazionale per la conservazione della natura (IUCN) come «specie in pericolo» (Endangered). Tale status trae giustificazione dalla ridottissima superficie dell'areale, inferiore a 5000 km², dalla forte frammentazione dell'habitat e dal crescente degrado delle condizioni di quest'ultimo.[1] Le minacce principali derivano dalla trasformazione dell'habitat in aree agricole e dalla diffusione di specie invasive che coprono il terreno di fitta vegetazione. La specie non è oggetto di caccia, né considerata dannosa per l'agricoltura.[2]

Il numero di esemplari è sconosciuto, ma secondo stime basate su una densità compresa tra tre e dieci animali per ettaro e una superficie dell'areale di circa 41000 ettari si ritiene che la popolazione sia costituita da un numero compreso tra 124000 e 413000 esemplari. La specie è piuttosto comune nel Carrizo Plain National Monument.[1]

Il citello antilope di Nelson o di San Joaquin (Ammospermophilus nelsoni (Merriam, 1893)) è uno scoiattolo appartenente al genere dei citelli antilope (Ammospermophilus). È endemico della valle di San Joaquin nel sud della California. Il suo nome commemora Edward William Nelson.

De nelsongrondeekhoorn (Ammospermophilus nelsoni) is een zoogdier uit de familie van de eekhoorns (Sciuridae). De wetenschappelijke naam van de soort werd voor het eerst geldig gepubliceerd door Merriam in 1893.

De soort komt voor in de Verenigde Staten.

Bronnen, noten en/of referentiesDe nelsongrondeekhoorn (Ammospermophilus nelsoni) is een zoogdier uit de familie van de eekhoorns (Sciuridae). De wetenschappelijke naam van de soort werd voor het eerst geldig gepubliceerd door Merriam in 1893.

Ammospermophilus nelsoni[2][3][4][5][6][7][8] är en däggdjursart som först beskrevs av Clinton Hart Merriam 1893. Ammospermophilus nelsoni ingår i släktet Ammospermophilus och familjen ekorrar.[9][10] Inga underarter finns listade.[9]

Kroppen är cylindrisk och avsmalnande i båda ändar, med små, rundade öron, små, men kraftiga ben, och en lång, yvig svans. Den har gulbrun till rödbrun päls med en vit strimma längs varje sida. På huvudet har den en vit ring kring varje öga. Vinterpälsen är mörkare än sommarpälsen.[11][12] Hanen är något större än honan, med en kroppslängd mellan drygt 23 till nästan 27 cm, mot honans 23 till drygt 25 cm. Vikten varierar mellan 142 och 179 g.[11]

Arten vistas på slätmark eller flacka sluttningar och låga bergstrakter som är upp till 1 100 meter höga. Den går dock sällan högre än 800 m. Habitatet utgörs av torra gräsmarker eller halvöknar med glest fördelade buskar på sedimenterade, lösa jordarter.[1]

Individerna lever i underjordiska bon som ofta grävs av andra djur som känguruspringmöss (Dipodomys). De bildar vanligen familjegrupper på 6 till 8 individer. Ammospermophilus nelsoni stannar vanligen i boet när vädret är för varmt eller för kallt (under 10ºC eller över 32ºC) men arten håller varken sommar- eller vinterdvala. Arten är starkt revirhävdande och ger sig sällan utanför sina egna revir. Genomsnittlig revirstorlek är 4,4 ha.[11]

Den genomsnittliga livslängden är mindre än ett år på grund av ungarnas höga dödlighet,[11] men enskilda individer kan bli över fem år gamla.[1] I fångenskap har arten lyckats bli 5 år och 8 månader.[11]

Arten är allätare, och söker aktivt efter insekter, gröna växtdelar och frön, men kan även äta små ryggradsdjur som ödlor, andra smågnagare och as (även av sin egen art).[11]

Själv utgör arten föda för främst nordamerikansk grävling, som brukar gräva ut deras underjordiska bon, men även för prärievarg och ökenkatträv.[11]

Ammospermophilus nelsoni är polygynandrisk, båda könen har flera sexualpartners. Dessa hämtas vanligen från det egna reviret, men man har sett exempel på honor som vandrat upp till en kilometer för att hitta en hane.[11] Parningen sker oftast under våren när tillgången till föda är störst. Efter ungefär 26 dagars dräktighet föder honan 6 till 12 ungar. Ungarna stannar sina första veckor i boet.[1]

Hanen tar ingen del i vården av ungarna.[11]

Denna gnagare förekommer bara i två mindre områden i centrala till västra San Joaquin Valley med angränsande land i Kalifornien.[1]

IUCN kategoriserar arten globalt som starkt hotad, och populationen minskar. Främsta anledningen är habitatförlust till följd av uppodling, byggnation och oljeutvinning. En bevarandeplan föreligger för området som man förmodar skall ha gynnsam inverkan på arten.[1]

Ammospermophilus nelsoni är en däggdjursart som först beskrevs av Clinton Hart Merriam 1893. Ammospermophilus nelsoni ingår i släktet Ammospermophilus och familjen ekorrar. Inga underarter finns listade.

Sóc linh dương San Joaquin hay Sóc linh dương Nelson, tên khoa học Ammospermophilus nelsoni. là loài động vật có vú trong họ Sóc, bộ Gặm nhấm. Loài này được Merriam mô tả năm 1893,[2] chúng được tìm thấy ở thung lũng San Joaquin, California.[3]

Sóc linh dương San Joaquin hay Sóc linh dương Nelson, tên khoa học Ammospermophilus nelsoni. là loài động vật có vú trong họ Sóc, bộ Gặm nhấm. Loài này được Merriam mô tả năm 1893, chúng được tìm thấy ở thung lũng San Joaquin, California.

分類 界 : 動物界 Animalia 門 : 脊索動物門 Chordata 亜門 : 脊椎動物亜門 Vertebrata 綱 : 哺乳綱 Mammalia 目 : ネズミ目(齧歯目) Rodentia 亜目 : リス亜目 Sciuromorpha 科 : リス科 Sciuridae 亜科 : Xerinae 族 : Xerini 属 : レイヨウジリス属 Ammospermophilus 種 : ネルソンレイヨウジリス

分類 界 : 動物界 Animalia 門 : 脊索動物門 Chordata 亜門 : 脊椎動物亜門 Vertebrata 綱 : 哺乳綱 Mammalia 目 : ネズミ目(齧歯目) Rodentia 亜目 : リス亜目 Sciuromorpha 科 : リス科 Sciuridae 亜科 : Xerinae 族 : Xerini 属 : レイヨウジリス属 Ammospermophilus 種 : ネルソンレイヨウジリスネルソンレイヨウジリス(Ammospermophilus nelsoni)は、ネズミ目(齧歯目)リス科レイヨウジリス属に属するジリスの1種。

カリフォルニア州サンホアキン・バレーに分布する絶滅危惧種。

谷の西の端に沿った斜面と尾根を含む、サンホアキン・バレーに分布する[2]。この地域の固有種で、今日の生息範囲は本来の生息地よりもかなり狭まっている。大規模な農地開発による生息地の喪失と、殺鼠剤の使用とが合わさって、絶滅危惧種に指定されるほどに個体数が減少した。

今日生存しているネルソンレイヨウジリスの大半は、元々の生息地で、手付かずで残っているカリーゾ平原(Carrizo Plain)に見られる。サンルイスオビスポ郡とカーン郡の孤立した場所の、砂に覆われた、穴の掘りやすい草地に家族で小さなコロニーを作って住む。本種と関連のあるよく見かける植物には、ハマアカザ属、マオウ属、いくつかのビャクシン属が含まれる[3]。種小名の nelsoni は、アメリカの動物学者エドワード・ウィリアム・ネルソン(Edward William Nelson)への献名である。

体長は、オスが約249ミリメートル、メスが約238ミリメートル[2]。 被毛は、背部がくすんだ黄褐色で、 腹部は白色、他のレイヨウジリス属の外見と同じく、体の両側面に白色の縞がある[2]。尾の下側は、黄褐色がかった白色で黒い縁取りがある[2]。

ハウベッカーの研究によって、本種の繁殖とライフサイクルについて豊富な情報を得ることができる[3][4][5]。繁殖は、晩冬から早春にかけて行い、3月に出産する[5]。妊娠期間は、1か月未満[3]。子供は、4月の第1週頃まで巣穴から出てこない[4]。繁殖は年1回で、子供は一年のうち緑の植物が最も豊富な時期に生まれる[4]。

離乳は、子供が地上に姿を表す前に始まっているか、既に終わっている[3]。いったん地上に出ると、子供は独りで食べ物を探し回るようになる[3]。離乳期の間、母親は独りで食料を食べ、子供が鼻をこすりつけようとしたり、乳を飲もうとしたりするのを無視する[3]。必要に応じて、母親は違う巣穴で夜を過ごすこともある[3]。5月中旬頃には、子供の被毛から大人の被毛へと変化し始め、夏までに生え変わる[3]。大人に成長すると、年齢の違いは見分けがつかなくなる[4]。寿命は短く1年に満たないことも多いが、いくつかの個体は、野生下で4年以上生き延びた[4]。

コロニーは6-8匹からなるが、各個体が縄張りに均一に分散しているわけではない[6]。通常、1ヘクタールあたりおよそ1匹である[7]。 冬や夏の気温でも穴を掘り進みやすいため、深く、肥沃な土壌を好む[5][8]。放置されたカンガルーネズミの巣穴を、自分たちの巣穴にすることもある[5]。雌雄ともに同じ広さの、約4.4 ヘクタールの縄張りを持つ[4]。

雑食性で、種子、植物、昆虫などを食べる[7]。たまに貯食をする。オランダフウロ (Erodium cicutarium) とチャボチャヒキ (Bromus madritensis rubens) は重要な食料である[5]。しかしながら、食料は季節や時間によって変化する。緑の植物は、12月から翌年4月中旬までの間、最も豊富にあるため、最もよく食べられる食料である[3]。同様に、昆虫は4月中旬から12月にかけて豊富になり、食料の90パーセント以上になる[3]。種子は、1年のうちほとんど食べることができるが、好ましい食料ではない[3]。種子の方が豊富で手に入れやすい時でさえ、昆虫または緑の植物を選ぶ[3]。これは、暑く乾燥した気候を生き抜くために必要な水分が、昆虫や緑の植物により多く含まれることによると推測される[3]。残念なことに、近くに豊富な水源はない[8]。研究所の環境下では、彼らはすぐに水を飲むことができる[8]。しかしながら、日陰で水のない状態でも、少なくとも7か月は生き延びることができ、その7か月後、彼らは比較的健康で、全くやせ衰えていなかった[8]。

社会性がある[7]。個別に縄張りの外に連れ出し、知らない土地に放すと、独りでは動けず混乱してしまう[8]。生息環境の厳しい暑さのため、日中は多くのエネルギーを消費しない[5]。実際に、直射日光の下では、31-32°Cという気温で死んでしまう[4]。したがって、日中の暑い時間帯にはほとんど活動しない。冬眠に関する証拠はないが、巣穴の中では寒さに悩むことはなく、氷点下の気温でも生き延びることができる[4]。早起きではなく、通常日の出後までに見かけることはないが、真昼の暑さを避けて、朝と夕方に巣穴から出て食事をする[7][8]。正午頃になると巣穴に消え、最も早くても午後2時頃までは姿を現さない[7]。気候の穏やかな日には、食糧探しに時間をかけ、対照的に暑い日や寒い日には、急いで食べ物を巣穴に持ち帰る[5]。砂浴びを好み、地面の土埃の上で体を伸ばしたり、転がったりすることは、寄生虫が蔓延するのを防ぐのにも役立つ[9]。

巣穴から出てくる際はとても用心深い[7]。食べ物を探しに行く際に通る特定のルートがあり、近くに危険を感じると、そのルート沿いにある巣穴に駆け込んで安全を確保する[5]。素早く動き、一箇所に長く止まらない[3]。食べ物の好き嫌いがあり、興味のない食べ物は手に取って確かめることさえ滅多にない[2]。危険から逃れる際の素早い動きに加えて、走る際に、尾の裏側の白っぽい色を見せるという特徴がある。走りながら、尾を背中の上に乗るように丸めて、素早く振ったり、前後にぴくぴくと動かす[7]。この動きは、アザミの冠毛が風になびく錯覚を引き起こし、捕食者に気づかれないようにするためのものである[7]。

さらに、捕食されるのを防ぐために、彼らは警戒鳴きをする。この警戒鳴きの音量は大きくはないが、激しい体の動きと関連している[6]。鳥類のハマヒバリとミヤマシトドもまた、捕食者を発見する助けとなる[5]。ネルソンレイヨウジリスは、これら2種の鳥の警戒鳴きを聞いて敵の存在を知ることができる。アメリカアナグマは、主な捕食者で、ネルソンレイヨウジリスを捕まえるために巣穴を破壊する[2]。また、コヨーテとキットギツネも本種を捕食することで知られているが、彼らの主食ではない[5][10]。

農地開発と都市開発の増加は、本種にとって増えつつある問題である[2][11][12]。本種は、耕された土地ではコロニーを作らないため、農地の増加は彼らの生息地を奪い、代わりの選択肢を残してはくれない。家畜の放牧は、残された生息地をさらに破壊し、外来植物は、本種が食料にしたり日陰や覆いとして頼ったりする在来植物を乗っ取ってしまう[12]。また、近くの農場から漂ってくる殺虫剤も生息地を侵害する [11]。これらの行為は、本種の個体数に害を及ぼすだけではなく、サンホアキン・バレーの他の在来生物や植物にも問題を引き起こしている。アオイ科の kern mallow Eremalche parryi、キク科の San Joaquin woolly threads Monolopia congdonii、アブラナ科の California jewel flower Caulanthus californicus、そしてサボテンの一種の Bakersfield cactus Opuntia basilaris などの在来植物は、外来植物に追いやられており、すべてアメリカ連邦政府の絶滅危惧植物となっている[12]。

サンホアキン・バレーでは、種の減少を引き起こしている外来種および他の人為的な原因を管理する試みが行われている[2][11][12][13]。規定された野焼きは、外来植物を管理するためのひとつの方法だが、この方法は在来種も同様に殺してしまうし、また費用が高い[12]。牛の放牧が土地に与える影響についての研究も行われており、土地に与える影響を減らす計画を発展させることができる。規定された放牧を使用する案は、谷の外来植物の生長を減少させるのに役立つ[12]。

他にも化学的、機械的な処置があるが、これらの方法は、特に広い地域では時間と費用がかかる[12]。また、除草剤の使用は、風によって化学物質が拡散すると、潜在的に生物種に悪い影響を及ぼす[12]。合衆国魚類野生生物局は、1998年に絶滅の危機に瀕する種の保存に関する法律10節においてセーフ・ハーバー協定を使用する案を含む復旧計画を立てた[13]。これにより、サンホアキン・バレーの絶滅危惧種を管理する最も望ましい妥協案を決定するため、合衆国魚類野生生物局と農園の地主との連携が始まった。

サンホアキン・バレーでは絶滅の危機に瀕した在来種の数が増加しているため、複数の種を同時に保護する取り組みが重要である。生態系レベルでの管理は、すべての種の役割が考慮される。また、周辺住民の知識を高め、教育することは、保護への基金を増やし、計画の運営をさらに助けるだろう。ネルソンレイヨウジリスの観察と研究は、サンホアキン・バレーにおいて本種がどのように絶滅に瀕しているのか、また安定した個体数を再構築するためには何をすることが必要かを特定するために必要である[2][12]。しかし、本種に関するほとんどの情報は、個体数の減少の問題と原因については議論しているが、見込みのある回復への多くの見識を与えてはくれない。1918年の時点で、グリネルとディクソンは、本種が絶滅するのは時間の問題だと考えていた[7]。

|date= (help)CS1 maint: Uses authors parameter

ネルソンレイヨウジリス(Ammospermophilus nelsoni)は、ネズミ目(齧歯目)リス科レイヨウジリス属に属するジリスの1種。

カリフォルニア州サンホアキン・バレーに分布する絶滅危惧種。

샌와킨영양다람쥐 또는 넬슨영양다람쥐(Ammospermophilus nelsoni)는 다람쥐과에 속하는 설치류의 일종이다.[2] 미국 캘리포니아주 샌와킨 계곡에서 발견된다.

샌와킨영양다람쥐는 샌와킨 계곡의 경사면과 계곡 서부 끝단을 따라서 능선 정상에서 발견된다. 샌와킨 계곡의 토착종이지만, 현재는 초기에 서식하던 곳보다 더 넓은 지역에서 서식한다. 샌와킨 계곡이 농경지로 크게 잠식되어 서식지가 줄어듬에 따라서 개체수가 감소되어 멸종위협종으로 분류되고 있다.