Associations

provided by BioImages, the virtual fieldguide, UK

In Great Britain and/or Ireland:

Foodplant / feeds on

gregarious, occasionally stromatic, covered, then piercing pycnidium of Phomopsis coelomycetous anamorph of Phomopsis exul feeds on twig of Maclura pomifera

Comments

provided by eFloras

In Pakistan, it is reported to be cultivated in gardens at Quetta, Peshawar, Wah and Lehtrar (near Rawalpindi), Abbotabad, Lahore etc. by R.R. Stewart (l.c. 194), but no specimens have been seen by the author.

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- Missouri Botanical Garden, 4344 Shaw Boulevard, St. Louis, MO, 63110 USA

Comments

provided by eFloras

Maclura pomifera is native to southwestern Arkansas, southeastern Oklahoma, and Texas; it is introduced and naturalized elsewhere in the United States. Collections in California, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Washington appear to represent isolated escapes.

Maclura pomifera has been widely used in fencerows on farms and along roadways in the midwest and eastern states as windbreaks and wildlife shelter.

The Comanches used Maclura pomifera as an eye medication (D. E. Moerman 1986).

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- Missouri Botanical Garden, 4344 Shaw Boulevard, St. Louis, MO, 63110 USA

Description

provided by eFloras

Tree, or rarely a large shrub, upto 15 (-20) m tall. Trunk 2.5-3 m in circumference with longitudinally deep fissured dark orange-brown bark. Young shoots olive green, pubescent to glabrous with 10-25 nun long axillary spines, rarely spineless. leaves with (1.5-) 2.5 an long petiole; lamina ovate to lanceolate-oblong, 5-12 (-16) cm long, (2-) 3-8 (-10) cm broad, entire, 5-costate from the cuneate to ± cordate base, shining above, finely pubescent to eventually glabrescent, apex acute-acuminate or rarely obtuse; stipules subulate, c. 2.5-3.5 mm long, acuminate, brownish-membranous, caducous. Male inflorescence a subglobose, 2.5-3.5 cm long, pseudoracemose clusters on slender, 1-2 cm long peduncles. Male flowers: pedicels 2-5 mm long, filiform; sepals basally connate, oval-oblong, c. 1.5 mm long, lanate hairy outside; staminal filaments longer than sepals with oval, exserted anthers. Female inflorescence a dense, axillary, subsessile to short peduncled globose head, c. 2 cm in diameter. Female flowers: subsessile; sepals united at the base, oblong c. 4 mm long, thick, lanate hairy at the apex; ovary with filiform, c. 20-25 mm long, hairy styles. Fruit large, sub-globose, 10-15 cm in diameter, orange-like but wrinkled and rough, yellowish-green. Seeds c. 1 cm long.

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- Missouri Botanical Garden, 4344 Shaw Boulevard, St. Louis, MO, 63110 USA

Description

provided by eFloras

Trees , to 20 m. Bark dark orange-brown, shallowly furrowed, ridges flat, often peeling into long, thin strips. Branchlets greenish yellow, becoming orange-brown; thorns stout, straight, to 1.5 cm, usually lateral to spur branch, spur branches often paired. Buds often paired, larger one red-brown, globose, 1.5-2 mm; scales ciliate; leaf scars half round, bundle scars arranged in oval. Leaves: stipules lanceolate, 1.5-2 mm, pubescent and long-ciliate; petiole 1-2.5 cm, pubescent. Leaf blade 4-12 × 2-6 cm, base rounded, apex acuminate; surfaces abaxially pale, glabrate, midrib and veins pubescent, adaxially lustrous, glabrous, midrib somewhat pubescent. Staminate inflorescences clustered on lateral spur branches; peduncle 1-1.5 cm, pubescent; heads globose or cylindric, 1.3-2.3 cm; pedicels 2-10 mm, glabrate. Pistillate inflorescences: peduncle 2-2.5 mm, glabrous or pubescent; heads globose, sessile on obconic receptacle, to 1.5 cm diam. Staminate flowers: sepals distinct, yellow-green, ca. 1 mm, apex acute, pubescent; filaments ca. 2 mm, closely appressed to sepals, flattened. Pistillate flowers: sepals green, obovate, 3 mm, enclosing and closely appressed to ovary, hoodlike, ciliate near tip; ovary ovoid, compressed, ca. 1 mm; style base green, ca. 3 mm, branches 4-6 mm, glabrous; stigma yellowish, papillose. Syncarps yellow-green to green, spheric, surface irregular, exuding milky sap when broken, peduncle short, glabrous or pubescent; achenes completely covered by accescent, thickened calyx lobes and deeply embedded in receptacle. Seeds cream colored, oval to oblong, 8-12 × 5-6 mm, base truncate or rounded with 1-3 minute points, margins with narrow groove, apex rounded, mucronate; surfaces minutely striated or pitted.

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- Missouri Botanical Garden, 4344 Shaw Boulevard, St. Louis, MO, 63110 USA

Distribution

provided by eFloras

Distribution: A native of N. America, introduced and cultivated in many parts of the world.

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- Missouri Botanical Garden, 4344 Shaw Boulevard, St. Louis, MO, 63110 USA

Distribution

provided by eFloras

Ala., Ark., Conn., Del., D.C., Fla., Ga., Ill., Ind., Iowa, Kans., Ky., La., Md., Mass., Mich., Miss., Mo., Nebr., N.J., N.Mex., N.Y., N.C., Ohio, Okla., Pa., R.I., S.C., S.Dak., Tenn., Tex., Va., W.Va., Wis.

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- Missouri Botanical Garden, 4344 Shaw Boulevard, St. Louis, MO, 63110 USA

Flower/Fruit

provided by eFloras

Fl. Per.: May-July.

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- Missouri Botanical Garden, 4344 Shaw Boulevard, St. Louis, MO, 63110 USA

Flowering/Fruiting

provided by eFloras

Flowering spring.

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- Missouri Botanical Garden, 4344 Shaw Boulevard, St. Louis, MO, 63110 USA

Habitat

provided by eFloras

Thickets; 0-1500m.

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- Missouri Botanical Garden, 4344 Shaw Boulevard, St. Louis, MO, 63110 USA

Synonym

provided by eFloras

Ioxylon pomiferum Rafinesque, Amer. Monthly Mag. & Crit. Rev. 2: 118. 1817; I. aurantiacum (Nuttall) Rafinesque; Maclura aurantiaca Nuttall

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- Missouri Botanical Garden, 4344 Shaw Boulevard, St. Louis, MO, 63110 USA

Common Names

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

osage-orange

hedge-apple

bois d'arc

- bibliographic citation

- Carey, Jennifer H. 1994. Liriodendron tulipifera.In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Description

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

More info for the terms:

fruit,

seed,

treeOsage-orange is a small, native, deciduous tree that averages 30 feet (9

m) in height. It has a short trunk and rounded crown. Shade-killed

lower branches remain on the tree for years, forming a dense thicket.

Branches growing in full sun have sharp, stout thorns 0.5 to 1 inch

(1.3-2.5 cm) long. Osage-orange has a large, round multiple fruit

composed of many fleshy calyces, each containing one seed. Osage-orange

generally has a well-developed taproot; a tree in Oklahoma had roots

more than 27 feet (8.2 m) deep. On shallow soils, roots spread

laterally [

4,

7,

34].

- bibliographic citation

- Carey, Jennifer H. 1994. Liriodendron tulipifera.In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Distribution

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

Osage-orange is native to a narrow belt in eastern Texas, southeastern

Oklahoma, southwestern Arkansas, and the extreme northwest corner of

Louisiana. This belt includes portions of the Blackland Prairies, Chiso

Mountains, and the Red River drainage [

4]. Osage-orange has been

introduced into most of the conterminous United States and has become

naturalized throughout much of the eastern United States and the central

Great Plains [

4,

8,

13,

28,

33,

35].

- bibliographic citation

- Carey, Jennifer H. 1994. Liriodendron tulipifera.In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Fire Ecology

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

More info for the terms:

fire regime,

top-killInformation about the fire ecology of osage-orange is lacking in the

literature. Osage-orange probably survives top-kill by fire.

FIRE REGIMES : Find fire regime information for the plant communities in which this

species may occur by entering the species name in the

FEIS home page under

"Find FIRE REGIMES".

- bibliographic citation

- Carey, Jennifer H. 1994. Liriodendron tulipifera.In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Fire Management Considerations

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

The dead, persistent, lower branches of osage-orange may promote crown

fires.

- bibliographic citation

- Carey, Jennifer H. 1994. Liriodendron tulipifera.In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Growth Form (according to Raunkiær Life-form classification)

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

More info on this topic. More info for the term:

phanerophytePhanerophyte

- bibliographic citation

- Carey, Jennifer H. 1994. Liriodendron tulipifera.In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Habitat characteristics

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

Osage-orange grows best in areas that receive 25 to 40 inches (640-1,020

mm) precipitation a year but tolerates a minimum of 15 inches (380 mm).

It is sensitive to cold and succumbs to winter-kill in the northern

Great Plains [

4,

34].

Osage-orange grows on a variety of soils but does best on rich, moist,

well-drained bottomlands. It occurs on alkaline soils, shallow soils

overlaying limestone, clayey soils, and sandy soils [

4,

26,

35]. It can

occur on bottomlands which are seasonally flooded [

4].

- bibliographic citation

- Carey, Jennifer H. 1994. Liriodendron tulipifera.In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Habitat: Cover Types

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

More info on this topic. This species is known to occur in association with the following cover types (as classified by the Society of American Foresters):

93 Sugarberry - American elm - green ash

- bibliographic citation

- Carey, Jennifer H. 1994. Liriodendron tulipifera.In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Habitat: Ecosystem

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

More info on this topic. This species is known to occur in the following ecosystem types (as named by the U.S. Forest Service in their Forest and Range Ecosystem [FRES] Type classification):

FRES13 Loblolly - shortleaf pine

FRES14 Oak - pine

FRES15 Oak - hickory

FRES16 Oak - gum - cypress

FRES17 Elm - ash - cottonwood

FRES18 Maple - beech - birch

FRES38 Plains grasslands

FRES39 Prairie

- bibliographic citation

- Carey, Jennifer H. 1994. Liriodendron tulipifera.In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Habitat: Plant Associations

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

More info on this topic. This species is known to occur in association with the following plant community types (as classified by Küchler 1964):

More info for the term:

forestK098 Northern floodplain forest

K100 Oak - hickory forest

K111 Oak - hickory - pine forest

K113 Southern floodplain forest

- bibliographic citation

- Carey, Jennifer H. 1994. Liriodendron tulipifera.In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Immediate Effect of Fire

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

More info for the terms:

fire severity,

severitySmall-diameter osage-orange are probably top-killed by most fires.

Depending on fire severity and root depth, they may be completely

killed. Larger individuals may survive.

- bibliographic citation

- Carey, Jennifer H. 1994. Liriodendron tulipifera.In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Importance to Livestock and Wildlife

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

More info for the terms:

cover,

fruit,

treeOsage-orange provides shelter and cover for wildlife. Small mammals and

birds use the thorny tree for cover. The bitter-tasting, fleshy fruit

is generally not eaten, but some animals including squirrel, fox, red

crossbill, and northern bobwhite occasionally eat the seeds

[

4,

14,

24,

34]. Seedlings and sprouts are browsed occasionally [

4].

Downy woodpeckers use osage-orange as forage sites [

10].

- bibliographic citation

- Carey, Jennifer H. 1994. Liriodendron tulipifera.In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Key Plant Community Associations

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

More info for the term:

forestNative and naturalized populations of osage-orange occur in rich

bottomland forests and on sandy terraces. On the Trinity River

floodplain in Texas, mostly small (less than 8-inch [20 cm] diameter)

osage-orange occurs in bottomland forests dominated by cedar elm (Ulmus

crassifolia), sugarberry (Celtis laevigata), green ash (Fraxinus

pennsylvanica), and western soapberry (Sapindus soponaria var.

drummondii) [

18]. In Iowa, osage-orange occurs in a honey-locust

(Gleditsia triacanthos)-black locust (Robinia psuedoacacia)-boxelder

(Acer negundo)-elm (Ulmus spp.) forest [

15]. On lower terraces of Salt

Creek in Illinois, osage-orange occurs in a bur oak (Quercus

macrocarpa)-hackberrry (Celtis occidentalis) forest [

16]. Osage-orange

is also associated with white oak (Quercus alba), white ash (Fraxinus

americana), and red mulberry (Morus rubra) [

4].

In Tennessee, Kentucky, and Alabama, osage-orange occurs with eastern

redcedar (Juniperus virginiana), black walnut (Juglans nigra), hickory

(Carya spp.), and elm [

4].

Osage-orange that has escaped cultivation often occurs as thickets along

fencerows and ditches, in ravines, and in overgrazed pastures. It

commonly occurs with honey-locust in disturbed areas [

4].

- bibliographic citation

- Carey, Jennifer H. 1994. Liriodendron tulipifera.In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Life Form

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

More info for the term:

treeTree

- bibliographic citation

- Carey, Jennifer H. 1994. Liriodendron tulipifera.In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Management considerations

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

Osage-orange is planted in shelterbelts and hedgerows of the Great

Plains. It is planted alone or in a row adjacent to a row of evergreens

or taller hardwoods [

34]. Osage-orange hedges are maintained as fences

by pruning [

24]. While a favorite of the past, osage-orange hedgerows

are now replaced with species that provide more benefit to wildlife

[

14]. Osage-orange is recommended for planting on deep, moist,

permeable soils and medium to shallow upland silty-clayey loams, sandy

loams, and loamy sands. It is not recommended for sandhills or wet,

poorly drained soils [

21].

Osage-orange hedges are often clearcut for posts. Winter cuttings

produce the most vigorous stump sprouts which regenerate the hedge [

27].

Three to five years after clearcutting, the new sprout stands should be

thinned to 240 stems per 100 meters. The sprouts are susceptible to

fire and grazing [

4].

Osage-orange is generally resistant to disease and insects; the only

serious affliction is cotton root rot (Phymatotrichum omnivorum) [

4,

22].

Eastern mistletoe (Phoradendron serotinum) occasionally parasitizes

osage-orange [

8].

Hamel [

9] describes herbicide application rates, methods, and seasons

for osage-orange control. Triclopyr or picloram, applied with a

chainsaw girdling treatment, are effective against osage-orange [

17].

Launchbaugh and Owensby [

12] describe preferred osage-orange herbicide

control methods for Kansas.

- bibliographic citation

- Carey, Jennifer H. 1994. Liriodendron tulipifera.In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Nutritional Value

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

More info for the term:

fruitThe fleshy fruit of osage-orange is more than 80 percent digestible [

25].

- bibliographic citation

- Carey, Jennifer H. 1994. Liriodendron tulipifera.In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Occurrence in North America

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

AL AR CA CO CT DE FL GA IL IN

IA KS KY LA ME MD MA MI MS MO

NE NH NJ NY NC OH OK OR PA RI

SC SD TN TX UT VT VA WA WV

- bibliographic citation

- Carey, Jennifer H. 1994. Liriodendron tulipifera.In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Other uses and values

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

More info for the term:

fruitEarly settlers of the Great Plains used osage-orange for hedgerows. The

diffuse, thorny branches form impenetrable hedges which were used to

fence in livestock [

24].

Osage-orange wood extractives are used for food processing, pesticide

manufacturing, and dye making. The Osage Indians used the wood for dye

and bows. The strong-smelling fruit repels cockroaches [

24].

Osage-orange is planted as an ornamental. There is an unusual thornless

male form which is clonally propagated [

19].

- bibliographic citation

- Carey, Jennifer H. 1994. Liriodendron tulipifera.In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Palatability

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

More info for the term:

fruitOsage-orange fruit and browse are generally not palatable [

4,

33,

34].

- bibliographic citation

- Carey, Jennifer H. 1994. Liriodendron tulipifera.In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Phenology

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

More info on this topic. More info for the term:

fruitOsage-orange generally flowers from April to June and the fruit ripens

from September to October [

2,

4]. It flowers in mid-May in Kansas and

Nebraska [

28].

- bibliographic citation

- Carey, Jennifer H. 1994. Liriodendron tulipifera.In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Plant Response to Fire

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

Osage-orange probably sprouts if top-killed by fire.

- bibliographic citation

- Carey, Jennifer H. 1994. Liriodendron tulipifera.In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Post-fire Regeneration

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

Tree with adventitious-bud root crown/soboliferous species root sucker

- bibliographic citation

- Carey, Jennifer H. 1994. Liriodendron tulipifera.In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Regeneration Processes

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

More info for the terms:

dioecious,

peat,

seedOsage-orange reproduces vegetatively and by seed. It is dioecious.

Female trees begin producing seeds at age 10 but are most productive

from age 25 to 65. Good seed crops are produced nearly every year.

Seeds are disseminated by animals, gravity, and water. Seeds have a

slight dormancy which is overcome by soaking in water for 2 days or

stratifying in sand or peat for 30 days. Seed germination requires

exposed mineral soil and full light. At 7 years of age, osage-orange is

about 8 feet (2.4 m) tall with a crown spread of about 6 feet (1.8 m)

[

2,

4,

40].

Seed collection, cleaning, storage, and planting techniques are

described [

2,

34].

Osage-orange sprouts vigorously from the stump [

4,

34]. Godfrey [

7]

suggested that it also sprouts from the roots.

- bibliographic citation

- Carey, Jennifer H. 1994. Liriodendron tulipifera.In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Regional Distribution in the Western United States

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

More info on this topic. This species can be found in the following regions of the western United States (according to the Bureau of Land Management classification of Physiographic Regions of the western United States):

14 Great Plains

- bibliographic citation

- Carey, Jennifer H. 1994. Liriodendron tulipifera.In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Successional Status

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

More info on this topic. More info for the terms:

forest,

hardwoodThe shade tolerance of osage-orange is not well defined. It has been

listed as intermediate in tolerance [

32] and intolerant [

4].

Osage-orange grows in the subcanopy of bottomland forests [

4,

16], but it

also invades overgrazed pastures and other open, disturbed sites with

eroding soil. Osage-orange regenerates naturally on sunny sites but

grows when planted in dense hedges [

4].

Osage-orange in remnant bottomland hardwood forests is negatively

associated with fragment size. In other words, the smaller the area of

remnant forest, the more likely that osage-orange will occur there.

Rudis [

23] suggested that fragmentation may promote and accelerate the

establishment of pioneer species and species adapted to disturbance.

- bibliographic citation

- Carey, Jennifer H. 1994. Liriodendron tulipifera.In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Taxonomy

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

The currently accepted scientific name for osage-orange is Maclura

pomifera (Raf.) Schneid. (Moraceae) [

8,

13,

28]. There are no currently

accepted infrataxa.

- bibliographic citation

- Carey, Jennifer H. 1994. Liriodendron tulipifera.In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Value for rehabilitation of disturbed sites

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

More info for the term:

reclamationOsage-orange is used for soil stabilization and strip mine reclamation

[

3,

4,

32]. It is adapted to most surface mine conditions but does better

in less acidic, well-drained mine soils. It has a lower soil pH limit

of 4.5. Osage-orange had a 33 percent survival rate 30 years after

planting on mine soils in Illinois and Indiana, and a 39 percent

survival rate after 30 years on mine soils in Ohio [

32]. Osage-orange

is sensitive to soil compaction [

4].

- bibliographic citation

- Carey, Jennifer H. 1994. Liriodendron tulipifera.In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Wood Products Value

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

Osage-orange wood is hard, durable, and resistant to decay. It is

primarily used for fence posts [

4,

24].

- bibliographic citation

- Carey, Jennifer H. 1994. Liriodendron tulipifera.In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Associated Forest Cover

provided by Silvics of North America

Osage-orange is not included in any of the forest types recognized by the

Society of American Foresters (13). In moist, well-drained minor bottom lands

in northwestern Louisiana and nearby parts of Oklahoma, Arkansas, and Texas, it

is found with white oak Quercus alba), hickories (Carya spp.),

white ash (Fraxinus americana), and red mulberry (Morus rubra)

(37). In Nebraska and Kansas, it invades overgrazed pastures, accompanied

by honeylocust (Gleditsia triacanthos) and is succeeded by black walnut

(Juglans nigra), oaks Quercus spp.), hackberry (Celtis spp.),

hickories, and elms (Ulmus spp.) (18). Among the most common

associates on lime stone- derived soils in middle Tennessee and neighboring

portions of Kentucky and Alabama are eastern redcedar (Juniperus

virginiana), black walnut, hickories, and elms (45).

- license

- cc-by-nc

- copyright

- USDA, Forest Service

Climate

provided by Silvics of North America

Within the natural range of Osage-orange, average annual temperature ranges

from about 18° to 21° C (65° to 70° F), July temperature

averages 27° C (80° F) and January temperature ranges from 6° to

7° C (43° to 45° F) with an extreme of -23° C (-10°

F). The frost-free period averages 240 days. Average annual precipitation

ranges from 1020 to 1140 min (40 to 45 in), and April to September rainfall

from 430 to 630 min (17 to 25 in).

Osage-orange is hardy as far north as Massachusetts but succumbs to

winter-kill in northeastern Colorado and the northern parts of Nebraska, Iowa,

and Illinois (34,36).

- license

- cc-by-nc

- copyright

- USDA, Forest Service

Damaging Agents

provided by Silvics of North America

Although Osage-orange is one of the healthiest tree

species in North America, it is attacked by some parasites. Cotton root rot,

caused by Phymatotrichum omnivorum, attacks Osage-orange and most other

windbreak species in Texas, Oklahoma, and Arizona (59). Losses are greatest in

plantings on dry soil where rainfall is scant. Cotton root rot is the only

serious disease.

Two species of mistletoe, Phoradendron serotinum and P.

tomentosum, grow in the branches and cause witches' brooms. Osage-orange

ornamentals in the Northeast have occasionally succumbed to Verticilliurn wilt,

caused by Verticillium albo-atrum. Leafspot diseases are caused by

Ovularia maclurae, Phyllosticta maclurae, Sporodesmium maclurae, Septoria

angustissima, Cercospora maclurae, and Cerotelium fici. Seedlings in

a Nebraska nursery have been killed by damping-off and root rot caused by

Phythium ultimum and Rhizoctonia solani (21). Phellinus ribis

attacks stemwood exposed in wounds. Poria ferruginosa and P.

punctata are the only two wood-destroying basidiomycetes reported on

Osage-orange; they occur only on dead wood, mainly in tropical and subtropical

parts of the western hemisphere (21). Maclura mosaic virus and cucumber mosaic

virus have been identified in leaf tissue of Osage-orange in Yugoslavia (35).

Osage-orange trees are attacked by at least four stem borers: the mulberry

borers (Doraschema wildii and D. alternatum) (4), the painted

hickory borer (Megacyllene caryae), and the red-shouldered hickory borer

(Xylobiops basilaris) (8). The twigs are parasitized by several scale

insects including the European fruit lecanium (Parthenolecanium corni),

the walnut scale (Quadraspidiotus juglansregiae) the cottony maple scale

(Pulvinaria innumerabilis) the terrapin scale (Mesolecanium

nigrofasciatum), and the San Jose scale (Quadraspidiotus perniciosus)

(25,46). The fruit-tree leafroller (Archips argyrospilus) feeds on

opening buds and unfolding leaves.

Osage-orange is attacked by, but is not a principal host of, the fall

webworm (Hyphantria cunea) (55), an Eriophyid mite, Tegolophus

spongiosus (51), and the fourspotted spider mite, Tetranychus canadensis

(4).

Osage-orange trees and several other species in 1 to 5-year-old plantations

on old fields in the prairie region of Illinois were partially or completely

girdled by mice. Severity of damage was greatest where weeds were most abundant

(26).

Windbreaks on the Great Plains, unless given cultivation during their early

years, are invaded by herbaceous vegetation, become sod bound, and are

permanently damaged (33,38,39). This vegetation may harbor rodents. Grazing is

not satisfactory for herbage control; multiple-row windbreaks should be fenced

to exclude livestock.

Osage-orange sustained less damage by insects, diseases, drought, hail, and

glaze than any other species planted in the Prairie States Forestry Project.

Along with bur oak (Quercus macrocarpa) it survived better than any

other deciduous species on uplands of the Southern Plains (7,38).

- license

- cc-by-nc

- copyright

- USDA, Forest Service

Flowering and Fruiting

provided by Silvics of North America

Osage-orange is dioecious. The simple, green,

four-part flowers appear soon after the leaves on the same spurs, opening from

April through June, and are wind pollinated. Male flowers are long peduncled

axillary racemes 2.5 to 3.8 cm (1 to 1.5 in) long on the terminal leaf spur of

the previous season; female flowers are in dense globose heads, axillary to the

leaves, about 2.5 cm (1 in) in diameter (2). The female flower in ripening

becomes very fleshy, forming a large multiple fruit or syncarp composed of

1-seeded drupelets. The fruit ripens from September through October. The ripe

fruit, 7.6 to 15 ern (3 to 6 in) in diameter, yellowish-green, resembles an

orange, often weighing more than a kilogram (2.2 lb). Fruits average 23/dkl (80

to the bu) (53). When bruised, the fruit exudes a bitter milky juice which may

cause a skin rash and which will blacken the fruit on drying.

Female trees often produce abundant fruit when no male trees exist nearby,

but such fruit contains no seeds.

- license

- cc-by-nc

- copyright

- USDA, Forest Service

Genetics

provided by Silvics of North America

There is no known literature on the genetics of Osage-orange, and no

information on geographic races is available. A thornless cultivar, Maclura

pomifera var. inermis (André) Schneid., can be propagated by

cuttings or scions taken from high in the crowns of old trees, where the twigs

are thornless (30,31). The only known hybrid, x Macludrania hybrida

André, is an intergeneric cross: x Macludrania = Cudrania x

Maclura. Cudrania tricuspidata (Carr.) Bureau is a spiny shrub or small

tree, native to China, Japan, and Korea. The Maclura parent is variety

inermis. The hybrid is a small tree with yellowish furrowed bark and

short, woody spines (2,41). Some authorities believe that the tropical

dye-wood, fustic & ChIorophora tinctoria (L.) Gaud.é belongs

in the genus Maclura; however, the majority opinion is that there is

only one species of Osage-orange (28).

- license

- cc-by-nc

- copyright

- USDA, Forest Service

Growth and Yield

provided by Silvics of North America

Osage-orange is a small tree or large shrub

averaging 9 m (30 ft) in height at maturity. Isolated trees on good sites may

reach heights of as much as 21 m (70 ft); crowded trees usually do not grow so

tall. In windbreak plantings on the Great Plains, Osage-orange grew 6 m (20 ft)

tall on average sites during a 20-year period; on some sites it grew 12 m (40

ft) tall (39).

Branchlets growing in full sunlight bear sharp, stout thorns. Slow-growing

twigs in the shaded portions of the crown of mature trees are thornless. The

thorns, 1.3 to 2.5 cm (0.5 to 1 in) long, are modified twigs. They form in leaf

axils on 1-year-old twigs. Shade-killed lower branches remain on the tree many

years. Regional estimates, based on the 19641966 Forest Surveys, indicated

virtually no Osage-orange of commercial size and quality on forest land in

Oklahoma, Texas, and Louisiana. There are two reasons for this: the species

usually grows on nonforest land, and merchantability standards for forest trees

do not apply to Osage-orange. Mature trees have short, curved boles and low,

wide, deliquescent crowns. Even in closed stands on good sites, less than half

the stems contain a straight log, 3 m (10 ft) long, sound and free of shake.

- license

- cc-by-nc

- copyright

- USDA, Forest Service

Reaction to Competition

provided by Silvics of North America

Osage-orange is tolerant according to some

authors (6,37) and very intolerant according to others (3). Overall, it is most

accurately classed as intolerant of shade. The occurrence and circumstances of

natural regeneration suggest intolerance, but the growth of planted

Osage-orange in hedges and shelterbelts, under strong competition, indicates

tolerance. How vigorously and at how advanced an age the species responds to

release has not been deter-mined. Severe competition does not prevent abundant

seed production. Osage-orange sprouts vigorously, even following cutting of

interior rows in windbreaks.

No literature on the silviculture of naturally regenerated forest stands of

Osage-orange is known.

- license

- cc-by-nc

- copyright

- USDA, Forest Service

Rooting Habit

provided by Silvics of North America

Osage-orange is characteristically deep rooted, but

because it has been planted so widely, the species is usually off-site, where

its rooting habit is variable. When the tree grows on shallow, fertile soils

over limestone, the lateral rootspread is tremendous (32).

Excavation of root systems in 7-year-old or older shelterbelts revealed a

lateral radius of 4.3 m (14 ft) and a depth of more than 8.2 m (27 ft) for

Osage-orange near Goodwell, OK (9). The soil was Richfield silt loam. Most of

the lateral roots were in the uppermost 0.3 m (1 ft) of soil. Excavations in

Nebraska revealed a lateral radius of 2.1 m (7 ft) and a depth of 1.5 m (5 ft)

for 3-year-old Osage-orange in Wabash silt loam; for 23-year-old Osage-orange

in Sogn silty clay loam, lateral radius was 4.9 m (16 ft) and depth was 2.4 m

(8 ft) (47). At both ages, there was a well-developed taproot, and most of the

long laterals originated within the first 0.3 m (I ft) of soil. At 3 years,

most of the long laterals were within the first 0.6 m (2 ft) of soil; at 23

years, laterals were as abundant in the eighth as in the first foot of soil.

- license

- cc-by-nc

- copyright

- USDA, Forest Service

Seed Production and Dissemination

provided by Silvics of North America

Female trees bear good seed crops

nearly every year, beginning about the 10th year. Commercial seed-bearing age

is optimum from 25 to 65 years, and 75 to 100 years may be the maximum (53).

Germinative capacity averages 58 percent. Seeds are nearly I cm (0.4 in) in

length. The number of clean seeds ranges from 15,400 to 35,300, averaging

30,900/kg (7,000 to 16,000, averaging 14,000/lb). Livestock, wild mammals, and

birds feed on the fruit and disseminate the seed. The seeds have a slight

dormancy that is easily overcome by soaking in water for 48 hours or by

stratifying in sand or peat for 30 days. Fruit stored over winter in piles

outdoors is easily cleaned in the spring, and the seed germinates promptly.

Viability can be maintained for at least 3 years by storing cleaned, air-dried

seeds in sealed containers at 5° C (41° F) (56). Recommended sowing

depth is about 6 to 13 min (0.25 to 0.5 in); soil should be firmed.

- license

- cc-by-nc

- copyright

- USDA, Forest Service

Seedling Development

provided by Silvics of North America

Germination is epigeal. Natural regeneration

apparently requires exposed mineral soil and full light. A study of survival

and growth in the Prairie States Forestry Project windbreaks indicated average

survival of Osage-orange at age 7 years to be 68 percent, ranking seventh of 16

"shrubs"; total height was 2.4 m (8 ft), ranking fifth of 16; and

crown spread was 1.8 m (6 ft). Osage-orange was usually planted in the shrub

(outer) rows and sometimes in the tree (inner) rows. It grows too fast,

however, to be considered a shrub and often overtops slower growing conifers

(33).

- license

- cc-by-nc

- copyright

- USDA, Forest Service

Special Uses

provided by Silvics of North America

Osage-orange has been planted in great numbers, first as a field hedge,

before barbed wire became available, secondly as a windbreak and component of

shelterbelts, and thirdly to stabilize soils and control erosion.

The single-row field hedge proved to be a valuable windbreak on the prairie;

evidence of this was the raised ground level under 15-year-old hedges, caused

by accumulation of windborne soil material. Hedges around every quarter-section

were common, especially in areas of deep sand (20,38). These hedges were a

source of durable posts. Prairie farmers customarily clearcut hedges on a 10-

to 16-year cycle, obtaining about 2,500 fence posts per kilometer (4,000 per

mi) of single-row hedge. The slash was piled over the stumps to protect the new

sprouts from browsing livestock. Pole-sized and larger Osage-orange trees are

practically immune to browsing, but seedlings and tender sprouts are highly

susceptible. Recommended practice is to thin the new sprout stands to 240

vigorous stems per 100 m (73/100 ft), 3 to 5 years after the clearcut, and to

protect the sprouts from fire. If inadvertently burned, the sprouts should be

cut back immediately to encourage new, vigorous growth (20).

Osage-orange heartwood is the most decay-resistant of all North American

timbers and is immune to termites. The outer layer of sapwood is very thin;

consequently, even small-diameter stems give long service as stakes and posts

(40,43). About 3 million posts were sold annually in Kansas during the early

1970's. The branch wood was used by the Osage Indians for making bows and is

still recommended by some archers today.

The chemical properties of the fruit, seed, roots, bark, and wood may be

more important than the structural qualities of the wood. A number of

extractives have been identified by researchers, but they have not yet been

employed by industry (11,12,23, 24,44,58). Numerous organic compounds have also

been obtained from various parts of the tree (16,44,57). An antifungal agent

and a nontoxic antibiotic useful as a food preservative have been extracted

from the heartwood (5,24).

Osage-orange in prairie regions provides valuable cover and nesting sites

for quail, pheasant, other birds, and animals (20,33), but the bitter-tasting

fruit is little eaten by wildlife. Reports that fruit causes the death of

livestock have been proven wrong by feeding experiments in several States.

Osage-orange has been successfully used in strip mine reclamation. Its ease

of planting, tolerance of alkaline soil, and resistance to drought are

desirable qualities (1,14,29). These qualities plus growth, long life, and

resistance to injury by ice, wind, insects, and diseases make Osage-orange a

valued landscape plant (15,30,31).

- license

- cc-by-nc

- copyright

- USDA, Forest Service

Vegetative Reproduction

provided by Silvics of North America

Osage-orange may be vegetatively propagated

using root cuttings or with greenwood cuttings under glass. To propagate

thornless male (nonfruiting) clones for ornamental use, scions or cuttings

should be taken only from the mature part of the crown of a tree past the

juvenile stage. Perhaps the easiest way to grow selected stock is by grafting

chip buds onto nursery-run seedlings and plastic-wrapping the graft area

(30,31).

- license

- cc-by-nc

- copyright

- USDA, Forest Service

Brief Summary

provided by Silvics of North America

Moraceae -- Mulberry family

J. D. Burton

Osage-orange (Maclura pomifera) produces no sawtimber, pulpwood, or

utility poles, but it has been planted in greater numbers than almost any other

tree species in North America. Known also as hedge, hedge-apple, bodark,

bois-d'arc, bowwood, and naranjo chino, it made agricultural settlement of the

prairies possible (though not profitable), led directly to the invention of

barbed wire, and then provided most of the posts for the wire that fenced the

West. The heartwood, bark, and roots contain many extractives of actual and

potential value in food processing, pesticide manufacturing, and dyemaking.

Osage-orange is used in landscape design, being picturesque rather than

beautiful, and possessing strong form, texture, and character.

- license

- cc-by-nc

- copyright

- USDA, Forest Service

Distribution

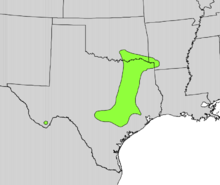

provided by Silvics of North America

The natural range of Osage-orange is in the Red River drainage of Oklahoma,

Texas, and Arkansas; and in the Blackland Prairies, Post Oak Savannas, and

Chisos Mountains of Texas (28). According to some authors the original range

included most of eastern Oklahoma (34), portions of Missouri (49,54), and

perhaps northwestern Louisiana (28,49).

Osage-orange has been planted as a hedge in all the 48 conterminous States

and in southeastern Canada. The commercial range includes most of the country

east of the Rocky Mountains, south of the Platte River and the Great Lakes,

excluding the Appalachian Mountains.

-The native range of osage-orange.

- license

- cc-by-nc

- copyright

- USDA, Forest Service

Maclura pomifera

provided by wikipedia EN

Maclura pomifera, commonly known as the Osage orange (/ˈoʊseɪdʒ/ OH-sayj), is a small deciduous tree or large shrub, native to the south-central United States. It typically grows about 8 to 15 metres (30–50 ft) tall. The distinctive fruit, a multiple fruit, is roughly spherical, bumpy, 8 to 15 centimetres (3–6 in) in diameter, and turns bright yellow-green in the fall.[5] The fruits secrete a sticky white latex when cut or damaged. Despite the name "Osage orange",[6] it is not related to the orange.[7] It is a member of the mulberry family, Moraceae.[8] Due to its latex secretions and woody pulp, the fruit is typically not eaten by humans and rarely by foraging animals. Ecologists Daniel H. Janzen and Paul S. Martin proposed in 1982 that the fruit of this species might be an example of what has come to be called an evolutionary anachronism—that is, a fruit coevolved with a large animal seed dispersal partner that is now extinct. This hypothesis is controversial.[9][10]

Maclura pomifera has many names, including mock orange, hedge apple, hedge, horse apple, crab apple, monkey ball, monkey brains and yellow-wood. The name bois d'arc (from French meaning "bow-wood") has also been corrupted into bodark and bodock.[11][12][13]

History

The earliest account of the tree in the English language was given by William Dunbar, a Scottish explorer, in his narrative of a journey made in 1804 from St. Catherine's Landing on the Mississippi River to the Ouachita River.[14] Meriwether Lewis sent some slips and cuttings of the curiosity to President Jefferson in March 1804. According to Lewis's letter, the samples were donated by "Mr. Peter Choteau, who resided the greater portion of his time for many years with the Osage Nation". (Note: This referred to Pierre Chouteau, a fur trader from Saint Louis.) Those cuttings did not survive. In 1810, Bradbury relates that he found two Maclura pomifera trees growing in the garden of Pierre Chouteau, one of the first settlers of Saint Louis, apparently the same person.[14]

American settlers used the Osage orange (i.e. "hedge apple") as a hedge to exclude free-range livestock from vegetable gardens and corn fields. Under severe pruning, the hedge apple sprouted abundant adventitious shoots from its base; as these shoots grew, they became interwoven and formed a dense, thorny barrier hedge. The thorny Osage orange tree was widely naturalized throughout the United States until this usage was superseded by the invention of barbed wire in 1874.[15][6][16][17] By providing a barrier that was "horse-high, bull-strong, and pig-tight", Osage orange hedges provided the "crucial stop-gap measure for westward expansion until the introduction of barbed wire a few decades later".[18]

The trees were named bois d'arc ("bow-wood")[6] by early French settlers who observed the wood being used for war clubs and bow-making by Native Americans.[14] Meriwether Lewis was told that the people of the Osage Nation, "So much ... esteem the wood of this tree for the purpose of making their bows, that they travel many hundreds of miles in quest of it."[19] The trees are also known as "bodark", "bodarc", or "bodock" trees, most likely originating as a corruption of bois d'arc.[6]

The Comanche also used this wood for their bows.[20] They liked the wood because it was strong, flexible and durable,[6] and the bush/tree was common along river bottoms of the Comanchería. Some historians believe that the high value this wood had to Native Americans throughout North America for the making of bows, along with its small natural range, contributed to the great wealth of the Spiroan Mississippian culture that controlled all the land in which these trees grew.[21]

Etymology

The genus Maclura is named in honor of William Maclure[13] (1763–1840), a Scottish-born American geologist. The specific epithet pomifera means "fruit-bearing".[13] The common name Osage derives from Osage Native Americans from whom young plants were first obtained, as told in the notes of Meriwether Lewis in 1804.[17]

Description

General habit

Mature trees range from 12 to 20 metres (40–65 ft) tall with short trunks and round-topped canopies.[6] The roots are thick, fleshy, and covered with bright orange bark. The tree's mature bark is dark, deeply furrowed and scaly. The plant has significant potential to invade unmanaged habitats.[6]

The wood of M. pomifera is golden to bright yellow but fades to medium brown with ultraviolet light exposure.[22] The wood is heavy, hard, strong, and flexible, capable of receiving a fine polish and very durable in contact with the ground. It has a specific gravity of 0.7736 or 773.6 kg/m3 (48.29 lb/cu ft).

Leaves and branches

Leaves are arranged alternately in a slender growing shoot 90 to 120 centimetres (3–4 ft) long. In form they are simple, a long oval terminating in a slender point. The leaves are 8 to 13 centimetres (3–5 in) long and 5 to 8 centimetres (2–3 in) wide, and are thick, firm, dark green, shining above, and paler green below when full grown. In autumn they turn bright yellow. The leaf axils contain formidable spines which when mature are about 2.5 centimetres (1 in) long.

Branchlets are at first bright green and pubescent; during their first winter they become light brown tinged with orange, and later they become a paler orange brown. Branches contain a yellow pith, and are armed with stout, straight, axillary spines. During the winter, the branches bear lateral buds that are depressed-globular, partly immersed in the bark, and pale chestnut brown in color.

Flowers and fruit

As a dioecious plant, the inconspicuous pistillate (female) and staminate (male) flowers are found on different trees. Staminate flowers are pale green, small, and arranged in racemes borne on long, slender, drooping peduncles developed from the axils of crowded leaves on the spur-like branchlets of the previous year. They feature a hairy, four-lobed calyx; the four stamens are inserted opposite the lobes of calyx, on the margin of a thin disk. Pistillate flowers are borne in a dense spherical many-flowered head which appears on a short stout peduncle from the axils of the current year's growth. Each flower has a hairy four-lobed calyx with thick, concave lobes that invest the ovary and enclose the fruit. Ovaries are superior, ovate, compressed, green, and crowned by a long slender style covered with white stigmatic hairs. The ovule is solitary.

The mature multiple fruit's size and general appearance resembles a large, yellow-green orange (the fruit), about 10 to 13 centimetres (4–5 in) in diameter, with a roughened and tuberculated surface. The compound (or multiple) fruit is a syncarp of numerous small drupes, in which the carpels (ovaries) have grown together; thus, it is classified a multiple-accessory fruit. Each small drupe is oblong, compressed and rounded; they contain a milky latex which oozes when the fruit is damaged or cut.[23] The seeds are oblong. Although the flowering is dioecious, the pistillate tree when isolated will still bear large oranges, perfect to the sight but lacking the seeds.[14] The fruit has a cucumber-like flavor.[23]

Fruit burrowed into by animal eating seeds

Distribution

Natural range of

M. pomifera in pre-Columbian era America.

Osage orange's pre-Columbian range was largely restricted to a small area in what is now the United States, namely the Red River drainage of Oklahoma, Texas, and Arkansas, as well as the Blackland Prairies and post oak savannas.[6] A disjunct population also occurred in the Chisos Mountains of Texas.[24] It has since become widely naturalized in the United States and Ontario, Canada.[6] Osage orange has been planted in all the 48 contiguous states of the United States and in southeastern Canada.[24]

The largest known Osage orange tree is located at the Patrick Henry National Memorial, in Brookneal, Virginia, and is believed to be almost 350 years old.[25][26][27] Another historic tree is located on the grounds of Fort Harrod, a Kentucky pioneer settlement in Harrodsburg, Kentucky.[28]

Ecological aspects of historical distribution

Because of the limited original range and lack of obvious effective means of propagation, the Osage orange has been the subject of controversial claims by some authors to be an evolutionary anachronism, whereby one or more now extinct Pleistocene megafauna, such ground sloths, mammoths, mastodons or gomphotheres, fed on the fruit and aided in seed dispersal.[21][29] An equine species that became extinct at the same time also has been suggested as the plant's original dispersal agent because modern horses and other livestock will sometimes eat the fruit.[23] This hypothesis is controversial. For example, a 2015 study indicated that Osage orange seeds are not effectively spread by extant horse or elephant species,[30] while a 2018 study concludes that squirrels are ineffective, short-distance seed dispersers.[9] The claim has been criticised as a "just-so story" that lacks any empirical evidence.[10]

The fruit is not poisonous to humans or livestock, but is not preferred by them,[31] because it is mostly inedible due to a large size (about the diameter of a softball) and hard, dry texture.[23] The edible seeds of the fruit are used by squirrels as food.[32] Large animals such as livestock, which typically would consume fruits and disperse seeds, mainly ignore the fruit.[23]

Ecology

The fruits are consumed by black-tailed deer in Texas, and white-tailed deer and fox squirrels in the Midwest. Crossbills are said to peck the seeds out.[33] Loggerhead shrikes, a declining species in much of North America, use the tree for nesting and cache prey items upon its thorns.[34]

Cultivation

Maclura pomifera prefers a deep and fertile soil, but is hardy over most of the contiguous United States, where it is used as a hedge. It must be regularly pruned to keep it in bounds, and the shoots of a single year will grow one to two metres (3–6 ft) long, making it suitable for coppicing.[14][35] A neglected hedge will become fruit-bearing. It is remarkably free from insect predators and fungal diseases.[14] A thornless male cultivar of the species exists and is vegetatively reproduced for ornamental use.[24] M. pomifera is cultivated in Italy, the former Yugoslavia, Romania, former USSR, and India.[36]

Chemistry

Osajin and pomiferin are isoflavones present in the wood and fruit in an approximately 1:2 ratio by weight, and in turn comprise 4–6% of the weight of dry fruit and wood samples.[37] Primary components of fresh fruit include pectin (46%), resin (17%), fat (5%), and sugar (before hydrolysis, 5%).[38] The moisture content of fresh fruits is about 80%.[38]

Uses

A tree

felled in 1954 exhibits little rot after more than six decades

Typical bright yellow newly-cut wood

The Osage orange is commonly used as a tree row windbreak in prairie states, which gives it one of its colloquial names, "hedge apple".[6] It was one of the primary trees used in President Franklin Delano Roosevelt's "Great Plains Shelterbelt" WPA project, which was launched in 1934 as an ambitious plan to modify weather and prevent soil erosion in the Great Plains states; by 1942 it resulted in the planting of 30,233 shelterbelts containing 220 million trees that stretched for 18,600 miles (29,900 km).[39] The sharp-thorned trees were also planted as cattle-deterring hedges before the introduction of barbed wire and afterward became an important source of fence posts.[13][40] In 2001, its wood was used in the construction in Chestertown, Maryland of the schooner Sultana, a replica of HMS Sultana.[41]

The heavy, close-grained yellow-orange wood is dense and prized for tool handles, treenails, fence posts, and other applications requiring a strong, dimensionally stable wood that withstands rot.[6][42] Although its wood is commonly knotty and twisted, straight-grained Osage orange timber makes good bows, as used by Native Americans.[6] John Bradbury, a Scottish botanist who had traveled the interior United States extensively in the early 19th century, reported that a bow made of Osage timber could be traded for a horse and a blanket.[14] Additionally, a yellow-orange dye can be extracted from the wood, which can be used as a substitute for fustic and aniline dyes. At present, florists use the fruits of M. pomifera for decorative purposes.[43]

When dried, the wood has the highest heating value of any commonly available North American wood, and burns long and hot.[44][45][46]

Osage orange wood is more rot-resistant than most, making good fence posts.[6] They are generally set up green because the dried wood is too hard to reliably accept the staples used to attach the fencing to the posts. Palmer and Fowler's Fieldbook of Natural History 2nd edition rates Osage orange wood as being at least twice as hard and strong as white oak (Quercus alba). Its dense grain structure makes for good tonal properties. Production of woodwind instruments and waterfowl game calls are common uses for the wood.[47]

Compounds extracted from the fruit, when concentrated, may repel insects. However, the naturally occurring concentrations of these compounds in the fruit are too low to make the fruit an effective insect repellent.[31][48][49] In 2004, the EPA insisted that a website selling M. pomifera fruits online remove any mention of their supposed repellent properties as false advertising.[43]

Traditional medicine

The Comanche formerly used a decoction of the roots topically as a wash to treat sore eyes.[50]

References

-

^ Stritch, L. (2018). "Maclura pomifera". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T61886714A61886723. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-1.RLTS.T61886714A61886723.en. Retrieved October 15, 2022.

-

^ "NatureServe Explorer 2.0". explorer.natureserve.org. Retrieved October 28, 2022.

-

^ "Maclura pomifera (Raf.) C.K. Schneid". Tropicos. Retrieved February 24, 2014.

-

^ "The Plant List". The Plant List. Retrieved February 24, 2014.

-

^ Boggs, Joe. "Bois D'Arc". Buckeye Yard & Garden Online. Ohio State University. Retrieved March 26, 2023.

-

^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Wynia, Richard L. (March 2011). "Plant fact sheet: Osage orange, Maclura pomifera (Rafin.)" (PDF). US Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service. Retrieved October 25, 2017.

-

^ Jesse, Laura; Lewis, Donald (October 24, 2014). "Hedge Apples for Home Pest Control?". Horticulture & Home Pest News. Iowa State University of Science and Technology. Retrieved January 29, 2016.

-

^ Wayman, Dave (March 1985). "The Osage Orange Tree: Useful and Historically Significant". Mother Earth News. Retrieved January 29, 2016.

-

^ a b Murphy, Serena (2018). "Seed Dispersal in Osage Orange (Maclura pomifera) by Squirrels (Sciurus spp.)". American Midland Naturalist. 180 (2): 312–317. doi:10.1674/0003-0031-180.2.312.

-

^ a b Sinnott‐Armstrong, Miranda A.; Deanna, Rocio; Pretz, Chelsea; Liu, Sukuan; Harris, Jesse C.; Dunbar‐Wallis, Amy; Smith, Stacey D.; Wheeler, Lucas C. (March 2022). "How to approach the study of syndromes in macroevolution and ecology". Ecology and Evolution. 12 (3): e8583. doi:10.1002/ece3.8583. ISSN 2045-7758. PMC 8928880. PMID 35342598.

-

^ "Maclura pomifera". Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN). Agricultural Research Service (ARS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Retrieved January 30, 2016.

-

^ Bobick, James (2004). The Handy Biology Answer Book. Detroit, Michigan: Visible Ink Press. p. 178. ISBN 1578593034. Retrieved January 30, 2016.

-

^ a b c d Wynia, Richard (March 2011). "Plant fact sheet for Osage orange (Maclura pomifera)" (PDF). Manhattan, Kansas: USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, Manhattan Plant Materials Center. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

-

^ a b c d e f g Keeler, Harriet L. (1900). Our Native Trees and How to Identify Them. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 258–262.

-

^ Barlow, Connie. "Anachronistic fruits and the ghosts who haunt them". Arnoldia 61, no. 2 (2001): 14–21.

-

^ Michael L. Ferro. "A Cultural and Entomological Review of the Osage Orange (Maclura pomifera (Raf.) Schneid.) (Moraceae) and the Origin and Early Spread of 'Hedge Apple' Folklore". Southeastern Naturalist, 13(m7), 1–34, (1 January 2014)

-

^ a b "Osage Oranges Take a Bough". Smithsonian Magazine, March 2004, p. 35.

-

^ Giannetto, Raffaella (2021). The culture of cultivation: recovering the roots of landscape architecture. Abingdon, Oxfordshire & New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0367356422.

-

^ Dillon, Richard (2003). Meriwether Lewis. Lafayette (California): Great West Books. p. 95. ISBN 0944220169. Retrieved January 30, 2016.

-

^ Rollings, Willard Hughes (2005). The Comanche. Philadelphia: Chelsea House Publishers. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-7910-8349-9.

-

^ a b Connie Barlow. Anachronistic Fruits and the Ghosts Who Haunt Them Archived 2007-01-06 at the Wayback Machine. Arnoldia, vol. 61, no. 2 (2001)

-

^ "Osage Orange | the Wood Database - Lumber Identification (Hardwood)".

-

^ a b c d e Barlow, Connie (2002). "The Enigmatic Osage Orange". The Ghosts of Evolution, Nonsensical Fruit, Missing Partners, and Other Ecological Anachronisms. New York: Basic Books. p. 120. ISBN 0786724897. Retrieved January 31, 2016.

-

^ a b c Burton, J D (1990). "Maclura pomifera". In Burns, Russell M.; Honkala, Barbara H. (eds.). Hardwoods. Silvics of North America. Washington, D.C.: United States Forest Service (USFS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Vol. 2. Retrieved October 5, 2012 – via Southern Research Station.

-

^ "Tree Information". Virginia Big Trees. Retrieved November 18, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) -

^ "The mystery of Patrick Henry's osage-orange: which enigma is greater; the age of the national champion or how it got to Virginia? - Free Online Library". www.thefreelibrary.com. Retrieved November 19, 2022.

-

^ "Osage-orange - VA". American Forests. Retrieved November 19, 2022.

-

^ Allen Bush. The Undaunted and Undented Osage Orange.

-

^ Bronaugh, Whit (2010). "The Trees That Miss The Mammoths". American Forests. 115 (Winter): 38–43.

-

^ Boone, Madison J.; Davis, Charli N.; Klasek, Laura; del Sol, Jillian F.; Roehm, Katherine; Moran, Matthew D. (March 11, 2015). "A Test of Potential Pleistocene Mammal Seed Dispersal in Anachronistic Fruits using Extant Ecological and Physiological Analogs". Southeastern Naturalist. 14 (1): 22–32. doi:10.1656/058.014.0109. S2CID 86809830.

-

^ a b Jauron, Richard (October 10, 1997). "Facts and Myths Associated with "Hedge Apples"". Horticulture and Home Pest News. Iowa State University. Retrieved October 22, 2014.

-

^ Murphy, Serena, Virginia Mitchell, Jessa Thurman, Charli N. Davis, Mattew D. Moran, Jessica Bonumwezi, Sophie Katz, Jennifer L. Penner, and Matthew D. Moran. "Seed Dispersal in Osage Orange (Maclura pomifera) by Squirrels (Sciurus spp.)." The American Midland Naturalist 180, no. 2 (2018): 312-317. Harvard

-

^ Peattie, Donald Culross (1953). A Natural History of Western Trees. New York: Bonanza Books. p. 482.

-

^ Tyler, Jack D (March 1992). "Nesting Ecology of the Loggerhead Shrike in Southwestern Oklahoma". The Wilson Bulletin. 104 (1): 95–104. JSTOR 4163119.

-

^ Toensmeier, Eric (2016). The Carbon Farming Solution: A Global Toolkit of Perennial Crops and Regenerative Agriculture Practices for Climate Change Mitigation and Food Security. Chelsea Green Publishing. p. 230. ISBN 978-1-60358-571-2.

-

^ Grandtner, Miroslav M. (2005). "Maclura pomifera". Elsevier's Dictionary of Trees, Volume 1: North America. Amsterdam: Elsevier. p. 500. ISBN 0080460186. Retrieved January 30, 2016.

-

^ Darji, K; Miglis, C; Wardlow, A; Abourashed, E. A (2013). "HPLC Determination of Isoflavone Levels in Osage Orange from the United States Midwest and South". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 61 (28): 6806–6811. doi:10.1021/jf400954m. PMC 3774050. PMID 23772950.

-

^ a b Smith, Jeffrey L.; Perino, Janice V. (January 1981). "Osage orange (Maclura pomifera): History and economic uses" (PDF). Economic Botany. 35 (1): 24–41. doi:10.1007/BF02859211. S2CID 35716036. Retrieved December 24, 2015.

-

^ R. Douglas Hurt Forestry of the Great Plains, 1902–1942

-

^ Kemp, Bill (May 31, 2015). "Hedgerows no match for bulldozers in postwar years". The Pantagraph. Retrieved April 18, 2016.

-

^ "Schooner Sultana". Sultanaprojects.org. Archived from the original on March 13, 2014. Retrieved February 24, 2014.

-

^ Cullina, William (2002). Native Trees, Shrubs, & Vines: A Guide to Using, Growing, and Propagating North American Woody Plants. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. p. 136. ISBN 0618098585. Retrieved January 31, 2016.

-

^ a b Grout, Pam. Kansas Curiosities: Quirky Characters, Roadside Oddities & Other Offbeat Stuff. Guilford, Conn: Globe Pequot Press, 2002.

-

^ Kays, Jonathan (October 2010). "Heating with Wood" (PDF). University of Maryland Extension. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 6, 2015. Retrieved January 31, 2016.

-

^ Prestemon, Dean R. (August 1998). "Firewood Production and Use" (PDF). Forestry Extension Notes. Iowa State University Extension Service. Retrieved January 31, 2016.

-

^ Kuhns, Michael; Schmidt, Tom. "Heating With Wood: Species Characteristics and Volumes". Utah State University Extension. Retrieved January 31, 2016.

-

^ Joe Duggan (November 20, 2018). "A block of wood and a waterfowl dream". Lincoln Journal Star. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

-

^ Ogg, Barbara. "Facts and Myths of Hedge Apples". University of Nebraska Lincoln. Retrieved November 11, 2013.

-

^ Nelson, Jennifer. "Osage Orange – Maclura pomifera". University of Illinois. Archived from the original on November 17, 2016. Retrieved November 11, 2013.

-

^ "Maclura Pomifera (search result)". Native American Ethnobotany Database. University of Michigan–Dearborn. Retrieved December 24, 2015.

- license

- cc-by-sa-3.0

- copyright

- Wikipedia authors and editors

Maclura pomifera: Brief Summary

provided by wikipedia EN

Maclura pomifera, commonly known as the Osage orange (/ˈoʊseɪdʒ/ OH-sayj), is a small deciduous tree or large shrub, native to the south-central United States. It typically grows about 8 to 15 metres (30–50 ft) tall. The distinctive fruit, a multiple fruit, is roughly spherical, bumpy, 8 to 15 centimetres (3–6 in) in diameter, and turns bright yellow-green in the fall. The fruits secrete a sticky white latex when cut or damaged. Despite the name "Osage orange", it is not related to the orange. It is a member of the mulberry family, Moraceae. Due to its latex secretions and woody pulp, the fruit is typically not eaten by humans and rarely by foraging animals. Ecologists Daniel H. Janzen and Paul S. Martin proposed in 1982 that the fruit of this species might be an example of what has come to be called an evolutionary anachronism—that is, a fruit coevolved with a large animal seed dispersal partner that is now extinct. This hypothesis is controversial.

Maclura pomifera has many names, including mock orange, hedge apple, hedge, horse apple, crab apple, monkey ball, monkey brains and yellow-wood. The name bois d'arc (from French meaning "bow-wood") has also been corrupted into bodark and bodock.

- license

- cc-by-sa-3.0

- copyright

- Wikipedia authors and editors