Associations

(

英語

)

由BioImages, the virtual fieldguide, UK提供

Foodplant / pathogen

Armillaria mellea s.l. infects and damages Tsuga heterophylla

Foodplant / saprobe

fruitbody of Mycena capillaripes is saprobic on dead, decayed needle of litter of Tsuga heterophylla

Comments

(

英語

)

由eFloras提供

Tsuga heterophylla is a dominant species over much of its broad distributional range. It has become the most important timber hemlock in North America. The wood is superior to that of other hemlocks for building purposes and it makes excellent pulp for paper production.

Tsuga × jeffreyi (Henry) Henry was described from southwestern British Columbia and western Washington as a hybrid between T . heterophylla and T . mertensiana . Hybridization is rare, if it occurs at all, and it is therefore of little consequence (R.J. Taylor 1972). At the upper elevational limits of its distribution and under stressful conditions, T . heterophylla tends to resemble T . mertensiana , e.g., leaves are less strictly 2-ranked and stomatal bands on the abaxial leaf surfaces are less conspicuous than at lower elevations.

Western hemlock ( Tsuga heterophylla ) is the state tree of Washington.

- 許可

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- 版權

- Missouri Botanical Garden, 4344 Shaw Boulevard, St. Louis, MO, 63110 USA

Description

(

英語

)

由eFloras提供

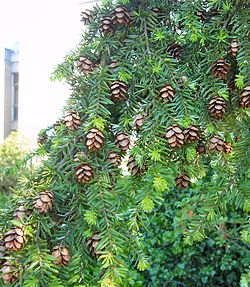

Trees to 50m; trunk to 2m diam.; crown narrowly conic. Bark gray-brown, scaly and moderately fissured. Twigs yellow-brown, finely pubescent. Buds ovoid, gray-brown, 2.5--3.5mm. Leaves (5--)10--20(--30)mm, mostly appearing 2-ranked, flattened; abaxial surface glaucous with 2 broad, conspicuous stomatal bands, adaxial surface shiny green (yellow-green); margins minutely dentate. Seed cones ovoid, (1--)1.5--2.5(--3) ´ 1--2.5cm; scales ovate, 8--15 ´ 6--10mm, apex round to pointed. 2 n =24.

- 許可

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- 版權

- Missouri Botanical Garden, 4344 Shaw Boulevard, St. Louis, MO, 63110 USA

Habitat & Distribution

(

英語

)

由eFloras提供

Coastal to midmontane forests; 0--1500m; Alta., B.C.; Alaska, Calif., Idaho, Mont., Oreg., Wash.

- 許可

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- 版權

- Missouri Botanical Garden, 4344 Shaw Boulevard, St. Louis, MO, 63110 USA

Synonym

(

英語

)

由eFloras提供

Abies heterophylla Rafinesque, Atlantic J. 1: 119. 1832

- 許可

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- 版權

- Missouri Botanical Garden, 4344 Shaw Boulevard, St. Louis, MO, 63110 USA

Common Names

(

英語

)

由Fire Effects Information System Plants提供

western hemlock

Pacific hemlock

west coast hemlock

- 書目引用

- Tesky, Julie L. 1992. Tsuga heterophylla. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Description

(

英語

)

由Fire Effects Information System Plants提供

More info for the term:

treeWestern hemlock is a large, native, evergreen tree. At maturity it is

generally 100 to 150 feet (30-46 m) tall and 2 to 4 feet (0.6-1.2 m) in

trunk diameter [

72]. On best sites, old-growth trees reach diameters

greater than 3.3 feet (1 m); maximum diameter is about 9 feet (3 m).

Heights of 160 to 200 feet (49-61 m) are not uncommon; maximum

height has been reported as 259 feet (79 m) [

57].

Western hemlock has a long slender trunk often becoming fluted when

large and has a short, narrow crown of horizontal or slightly drooping

branches. The needles are short-stalked and 0.25 to 0.87 inch (6-22 mm)

long, flat and rounded at the tip. The twigs are slender [

72]. The

bark is thin (1 to 1.5 inches [0.39-0.59 cm]) even on large trees; young

bark is scaly and on old trunks it is hard with furrows separating wide

flat ridges [

60]. Western hemlock is shallow rooted and does not

develop a taproot. The roots, especially the fine roots, are commonly

most abundant near the surface and are easily damaged by harvesting

equipment and fire. Maximum ages are typically over 400 years but less

than 500 years. The maximum age recorded is in excess of 700 years

[

57].

- 書目引用

- Tesky, Julie L. 1992. Tsuga heterophylla. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Distribution

(

英語

)

由Fire Effects Information System Plants提供

Western hemlock occurs in the Coast Ranges from Sonoma County California

to the Kenai Peninsula in Alaska. Inland it occurs along the western

and upper eastern slopes of the Cascade Range in Oregon and Washington

and west of the Continental Divide in the northern Rocky Mountains of

Montana and Idaho, north to Prince George, British Columbia

[

10,

56,

57,

78].

- 書目引用

- Tesky, Julie L. 1992. Tsuga heterophylla. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Fire Ecology

(

英語

)

由Fire Effects Information System Plants提供

More info for the terms:

fire intensity,

fire interval,

fire regime,

forest,

frequency,

habitat type,

lichen,

mean fire interval,

mesic,

wildfireWestern hemlock has a low degree of fire resistance [

20,

58]. It has

thin bark, shallow roots, highly flammable foliage, and a low-branching

habit which make it very susceptible to fire. Western hemlock tends to

form dense stands and its branches are often lichen covered, which

further increases its susceptibility to fire damage [

15,

29,

57].

The frequency of fire in western hemlock stands tends to be low because

it commonly occupies cool mesic habitats which offer protection from all

but the most severe wildfire [

22,

64]. In western hemlock forests of the

Pacific Northwest, the fire regime is generally from 150 to 400 or more

years [

58]. At Desolation Peak, Washington, western hemlock forest

types had a mean fire interval of 108 to 137 years [

3]. In the western

hemlock/Pachistima habitat type described by Daubenmire and Daubenmire

[

21], the mean fire interval is 50 to 150 years, and fire intensity in

these stands is quite variable [

9]. In the Bitterroot Mountains,

western hemlock stands are more likely to be destroyed by

stand-replacing fires because they often occupy steep montane slopes

which favor more intense burning [

8].

FIRE REGIMES : Find fire regime information for the plant communities in which this

species may occur by entering the species name in the

FEIS home page under

"Find FIRE REGIMES".

- 書目引用

- Tesky, Julie L. 1992. Tsuga heterophylla. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Fire Management Considerations

(

英語

)

由Fire Effects Information System Plants提供

Fire danger increases with the increasing volume of logging residue.

Logging old-growth stands or western hemlock can leave huge volumes of

residue compared with logging young stands, which leave little residue.

Burning cleans up the area and facilitates planting. Therefore burning

is often favored by land managers who intend to plant Douglas-fir to

obtain a mixture of Douglas-fir and western hemlock. The general trend

in western hemlock management, however, is away from broadcast burning

except where a huge accumulation of residues constitutes a fire hazard

[

64].

Burning in western hemlock stands is a valuable treatment when seedlings

and saplings are infected with dwarf mistletoe and need to be destroyed.

Fire is helpful in rehabilitation of brushy areas; burning brush to

ground level facilitates planting and favors planted seedlings in

keeping ahead of the brush sprouts [

64].

Fire spreads more slowly in western hemlock slash than in western

redcedar slash. Western hemlock slash drops its foliage. The slash of

western hemlock is less flammable when chipped [

52]. Slash from western

hemlock/western redcedar/Alaska-cedar forests produce greater nutrient

losses to the atmosphere when the slash composition has a greater

proportion of Alaska-cedar and western redcedar. One can expect smaller

nutrient losses when western hemlock makes up the majority of the slash

[

28]. For further details on burning of western hemlock slash, refer to

the

Fire Case Study in the Alaska-cedar Fire Effects Information System

Species Review.

- 書目引用

- Tesky, Julie L. 1992. Tsuga heterophylla. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Growth Form (according to Raunkiær Life-form classification)

(

英語

)

由Fire Effects Information System Plants提供

More info on this topic. More info for the term:

phanerophytePhanerophyte

- 書目引用

- Tesky, Julie L. 1992. Tsuga heterophylla. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Habitat characteristics

(

英語

)

由Fire Effects Information System Plants提供

More info for the terms:

density,

fern,

herb,

shrub,

vineWestern hemlock thrives in humid areas of the Pacific Coast and northern

Rocky Mountains. Growth is best in mild, humid climates where frequent

fog and precipitation occur during the growing season. The best stands

occur in the humid coastal regions. In subhumid regions with relatively

dry growing seasons, western hemlock is confined primarily to northerly

aspects, moist stream bottoms, or seepage sites [

10,

57,

59]. In Alaska,

western hemlock attains its largest size on moist flats and low slopes

[

72].

Precipitation and temperature: In the coastal range, western hemlock

occurs on sites with a mean annual precipitation of less than 15 inches

(380 mm) in Alaska to at least 262 inches (6,650 mm) in British

Columbia. In the Rocky Mountains it occurs on sites with mean annual

precipitation ranging from 22 inches (560 mm) to at least 68 inches

(1,730 mm). Mean annual temperatures where western hemlock commonly

occurs range from 32.5 to 52.3 degrees Fahrenheit (0.3-11.3 deg C) on

the coast and 36 to 46.8 degrees Fahrenheit (2.2-8.2 deg C) in the Rocky

Mountains. The frost-free period within the coastal range of western

hemlock averages less than 100 to more than 280 days. In the Rocky

Mountains the frost-free period is 100 to 150 days [

57].

Elevation: The elevational range of western hemlock is from sea level

to 7,000 feet (2,130 m). On the coast, western hemlock develops best

between sea level and 2,000 feet (610 m); in the Rocky Mountains, it

develops best between 1,600 and 4,200 feet (490-1,280 m) [

57].

Soils: Western hemlock grows on soils derived from all bedrock types

(except serpentines) within its range [

57]. It grows well on

sedimentary, metamorphic, and igneous materials. Western hemlock is

found on most soil textures. Height growth, however, decreases with an

increase in clay content or soil bulk density. This is attributed to

inadequate soil aeration or the inability of roots to penetrate compact

soils. Western hemlock does not do well on sites where the water table

is less than 6 inches (15 cm) below the soil surface. The pH under

stands containing western hemlock ranges from less than 3.0 to nearly

6.0 in the organic horizons. The pH in the surface mineral horizons

ranges from 4.0 to 6.3 and that of the C horizons from 4.8 to 6.2. The

optimum range of pH for seedlings is 4.5 to 5.0. Western hemlock is

highly productive on soils with a high range of available nutrients.

The productivity of western hemlock increases as soil nitrogen increases

[

57].

In the Coast Range, western hemlock is commonly associated with the

following shrub species: vine maple (Acer circinatum), dwarf

Oregongrape (Mahonia nervosa), Pacific rhododendron (Rhododendron

macrophyllum), stink currant (Ribes bracteosum), salmonberry, trailing

blackberry (R. ursinus), Pacific red elder (Sambucus callicarpa),

Alaska blueberry (Vaccinium alaskaense), big huckleberry (V.

membranaceum), oval-leaf huckleberry (V. ovalifolium), evergreen

huckleberry (V. ovatum), and red huckleberry (V. parvifolium)

[

12,

31,

32,

57].

In the Rocky Mountains, western hemlock is commonly associated with the

following shrub species: Oregon grape (Mahonia repens), russet

buffaloberry (Shepherdia canadensis), birchleaf spirea (Spiraea

betulifolia), dwarf blueberry (Vaccinium caespitosum), globe huckleberry

(V. globulare), and grouse whortleberry (V. scoparium) [

55,

57,

59,

69,

73].

Common shrub associates of both coastal and Rocky Mountain regions are

as follows: Sitka alder (Alnus sinuata), snowbush ceanothus (Ceonothus

velutinus), oceanspray (Holodiscus discolor), rustyleaf mensziesia

(Menziesia ferruginea), devilsclub, Pacific ninebark (Physocarpus

capitatus), prickly currant (Ribes lacustre), thimbleberry, and common

snowberry (Symphoricarpos albus) [

57].

Common herb associates with western hemlock include maidenhair fern

(Adiantum pedatum), ladyfern (Athyrium filix-femina), deerfern (Blechnum

spicant), mountain woodfern (Dryopteris austriaca), oakfern

(Gymnocarpium dryopteris), swordfern (Polystichum munitum), bracken fern

(Pteridium aquilinum), vanillaleaf (Achlys triphylla), wild ginger

(Asarum caudatum), princes-pine (Chimaphila umbellata), queenscup

beadlily (Clintonia unifora), cleavers bedstraw (Galium aparine),

sweetscented bedstraw (G. triflorum), twinflower (Linnaea borealis),

one-sided pyrola (Pyrola secunda), feather solomonplume (Smilacina

racemosa), white trillium (Trillium ovatum), roundleaf violet (Viola

orbiculata), and beargrass (Xerophyllum tenax) [

55,

57,

59,

69,

73].

- 書目引用

- Tesky, Julie L. 1992. Tsuga heterophylla. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Habitat: Cover Types

(

英語

)

由Fire Effects Information System Plants提供

More info on this topic. This species is known to occur in association with the following cover types (as classified by the Society of American Foresters):

202 White spruce - paper birch

205 Mountain hemlock

206 Engelmann spruce - subalpine fir

210 Interior Douglas-fir

212 Western larch

213 Grand fir

215 Western white pine

218 Lodgepole pine

221 Red alder

222 Black cottonwood - willow

223 Sitka spruce

224 Western hemlock

225 Western hemlock - Sitka spruce

226 Coastal true fir - hemlock

227 Western redcedar - western hemlock

228 Western redcedar

229 Pacific Douglas-fir

230 Douglas-fir - western hemlock

231 Port-Orford-cedar

232 Redwood

- 書目引用

- Tesky, Julie L. 1992. Tsuga heterophylla. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Habitat: Ecosystem

(

英語

)

由Fire Effects Information System Plants提供

More info on this topic. This species is known to occur in the following ecosystem types (as named by the U.S. Forest Service in their Forest and Range Ecosystem [FRES] Type classification):

FRES20 Douglas-fir

FRES21 Ponderosa pine

FRES22 Western white pine

FRES23 Fir - spruce

FRES24 Hemlock - Sitka spruce

FRES25 Larch

FRES26 Lodgepole pine

FRES27 Redwood

FRES28 Western hardwoods

- 書目引用

- Tesky, Julie L. 1992. Tsuga heterophylla. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Habitat: Plant Associations

(

英語

)

由Fire Effects Information System Plants提供

More info on this topic. This species is known to occur in association with the following plant community types (as classified by Küchler 1964):

More info for the term:

forestK001 Spruce - cedar - hemlock forest

K002 Cedar - hemlock - Douglas-fir forest

K003 Silver fir - Douglas-fir forest

K004 Fir - hemlock forest

K005 Mixed conifer forest

K006 Redwood forest

K008 Lodgepole pine - subalpine forest

K012 Douglas-fir forest

K013 Cedar - hemlock - pine forest

K014 Grand fir - Douglas-fir forest

K015 Western spruce - fir forest

- 書目引用

- Tesky, Julie L. 1992. Tsuga heterophylla. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Immediate Effect of Fire

(

英語

)

由Fire Effects Information System Plants提供

More info for the term:

crown fireWestern hemlock is commonly killed by fire. High-severity fires often

destroy all western hemlock [

24]. After a severe crown fire at Olympic

Mountain, Washington, overstory western hemlock suffered 91 percent

mortality [

4]. Even light ground fires are damaging because the shallow

roots are scorched [

57]. Postfire mortality of western hemlock is

common due to fungal infection of fire wounds [

29]. Most western hemlock

seedlings are killed by broadcast burning [

27,

64].

- 書目引用

- Tesky, Julie L. 1992. Tsuga heterophylla. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Importance to Livestock and Wildlife

(

英語

)

由Fire Effects Information System Plants提供

More info for the terms:

climax,

cover,

forest,

seed,

treeRoosevelt elk and black-tailed deer browse western hemlock in coastal

Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia [

57]. In the Oregon Cascades

deer mice consumed about 22 percent of the western hemlock seed fall.

This consumption occurred just before or during the germination process

[

76]. Black bear girdle pole-size western hemlock and larger saplings

or damage the bark at the base of the trees. Snowshoe hare and rabbit

clip off the main stems of western hemlock seedlings. Mountain beaver

clip the stems and lateral branches of seedlings and girdle the base of

saplings [

57].

Old-growth western hemlock stands provide hiding and thermal cover for

many wildlife species. In the southern Selkirk Mountains of northern

Idaho, northeastern Washington, and adjacent British Columbia, grizzly

bear have been known to use heavily timbered western hemlock forests

[

48]. In the western Oregon Cascades, western hemlock provides habitat

for many species of small mammals, including the northern flying

squirrel and red tree vole [

7,

67]. In Washington and Oregon, the

northern spotted owl is often found in forests dominated by Douglas-fir

(Pseudotsuga menziesii) and western hemlock. The majority of barred

owls observed in British Columbia have occurred in the Columbia Forest

Biotic Area in which western hemlock and western redcedar are the major

climax species [

6]. Western hemlock is used for nest trees by cavity

nesting bird species such as the yellow-bellied sapsucker and northern

three-toed woodpecker [

51].

- 書目引用

- Tesky, Julie L. 1992. Tsuga heterophylla. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Key Plant Community Associations

(

英語

)

由Fire Effects Information System Plants提供

More info for the terms:

association,

climax,

codominant,

cover,

cover type,

forest,

naturalWestern hemlock commonly occurs as a dominant or codominant on low- to

mid-elevation moist sites. In northern Idaho, plant communities

dominated by western hemlock occupy the moist, moderate temperature

sites within the maritime-influenced climatic zone of the northern Rocky

Mountains. Here, western hemlock can be found as the climax dominant

from 2,500 to 5,500 feet (760-1,680 m) and can dominate sites of all

exposures and landforms except wet bottomlands where it is replaced or

codominant with western redcedar (Thuja plicata) [

19]. In the Gifford

Pinchot National Forest of Washington, the western-hemlock-dominated

zone includes the lower elevation moist forests of the western Cascades

[

68]. In Mount Rainier National Park, Washington, the western

hemlock/devil's club (Oplopanax horridus) community occupies wet

benches, terraces, and lower slopes at low elevations [

32]. The western

hemlock riparian dominance type in Montana described by Hansen and

others [

39] is an infrequent cover type restricted to northwestern

Montana on toe-slope seepages, moist benches, and wet bottoms adjacent

to streams. Published classifications identifying western hemlock as a

dominant or codominant are as follows:

Classification and management of riparian and wetland sites in northwest

Montana [

14].

Classification of montane forest community types in the Cedar River

drainage of western Washington, U.S.A. [

54].

The forest communities of Mount Rainier National Park [

32].

Forest habitat types of Montana [

59].

Forest habitat types of northern Idaho: A second approximation [

19].

Forest types of the North Cascades National Park Service complex [

5].

Forest vegetation of eastern Washington and northern Idaho [

21].

A guide to the interior cedar-hemlock zone, northwestern transitional

subzone (ICHg), in the Prince Rupert Forest Region, British

Columbia [

36].

Natural vegetation of Oregon and Washington [

31].

Plant association and management guide [

41].

Plant association and management guide for the western hemlock zone.

Gifford Pinchot National Forest [

68].

Plant association and management guide for the western hemlock zone: Mt.

Hood National Forest [

37].

Plant association and management guide. Willamette National Forest [

42].

A preliminary classification of forest communities in the central

portion of the western Cascades in Oregon [

25].

Preliminary forest plant association management guide. Ketchikan area,

Tongass National Forest [

23].

Preliminary forest plant associations of the Stikine area Tongass

National Forest [

70].

Preliminary plant associations of the Siskiyou Mountain province [

12].

Preliminary plant associations of the southern Oregon Cascade Mountain

Province [

11].

Reference material Daubenmire habitat types [

69].

Riparian dominance types of Montana [

39].

A study of the vegetation of southeastern Washington and adjacent Idaho

[

73].

Vegetation mapping and community description of a small western cascade

watershed [

40].

Vegetation of the Abbott Creek Research Natural Area, Oregon [

53].

- 書目引用

- Tesky, Julie L. 1992. Tsuga heterophylla. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Life Form

(

英語

)

由Fire Effects Information System Plants提供

More info for the term:

treeTree

- 書目引用

- Tesky, Julie L. 1992. Tsuga heterophylla. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Management considerations

(

英語

)

由Fire Effects Information System Plants提供

More info for the terms:

competition,

forest,

natural,

seed,

seed tree,

selection,

treeInsects and disease: The major root and butt pathogens of western

hemolock are: Armillaria mellea, Heterobasidion annosum, Phaeolus

schweinitzii, Laetiporus sulphureus, Inenotus tomentosus, Poria

subacida, Phellinus weiri, and Indian paint fungus (Echinodontium

tinctorium) [

30,

57]. Western hemlock is severely damaged by Indian

paint fungus in the high Cascades; cull due to this rot may run as high

as 80 percent in old-growth stands [

30]. Dwarf mistletoe (Arceuthobium

campylopodum) is a common parasite on western hemlock which causes

wide-spread growth loss and mortality in old-growth stands [

62].

Important insects attacking western hemlock are a weevil (Steremnius

carinatus), western larch borer (Tetropium velutinum), western

blackheaded budworm (Acleris gloverana), western hemlock looper

(Lambdina fiscellaria lugubrosa), green striped forest looper

(Melanolophia imitata), saddleback looper (Ectropis crepuscularia), and

hemlock sawfly (Neodiprion tsugae). The western hemlock looper has

caused more mortality of western hemlock than any other insect pest.

Outbreaks can last 2 to 3 years on any one site. Although mortality is

greatest in old-growth western hemlock, vigorous 80- to 100-year-old

stands can also be severely damaged by this insect. The hemlock sawfly

is considered the second most destructive insect of western hemlock in

Alaska [

57].

Other damaging agents: Pole-sized and larger stands of western hemlock

are subject to severe windthrow. Uprooting is increased in areas where

a high water table or impenetrable layer in the soil causes trees to be

shallow rooted [

62]. Blowdown is a major problem in western hemlock

forests, and the need to leave windfirm borders is always present. If

only part of the stand will be removed, the leave trees need to be as

windfirm as possible [

64].

Western hemlock suffers frost damage in the Rocky Mountains, especially

along the eastern edge of its range [

57].

On droughty sites, top dieback is common; in exceptionally dry years,

entire stands of western hemlock saplings die [

57]. Western hemlock

seedlings and saplings are susceptible to sunscald following exposure of

young stems by thinning. Sunscald lesions often become infected with

decay organisms [

62].

Western hemlock is one of the conifers most sensitive to damage by

sulfur dioxide.

Spring applications of the iso-octyl esters of 2,4-D and 2,4,5-T in

diesel oil can kill up to 3 years of leader growth [

57].

Fertilization: The response of western hemlock to nitrogen fertilizer

is extremely variable. For overstocked stands, a combination of

precommercial thinning and fertilizer often gives the best response

[

57].

Silvicultural considerations: In terms of biomass production, western

hemlock forests are among the most productive forests in the world.

Natural stands of western hemlock along the Pacific Coast attain higher

yields than Douglas-fir stands having the same site index [

57,

64]. Pure

stands of western hemlock are so densely stocked that an acre of

100-year-old western hemlock forest can yield more timber (150,000 to

190,000 board feet on a good site) than a comparable stand of larger,

less dense Douglas-fir [

10,

64].

Western hemlock can be regenerated by most standard harvest methods. In

the past, clearcutting was the most common method used in western

hemlock stands [

64,

74]. As an aesthetically viable alternative to

clearcutting, shelterwood cutting has been proposed as a means of

controlling brush competition and favoring western hemlock seedlings

[

77]. The shelterwood method has been used successfully in even-aged

stands. Observations suggest that cutting of uneven-aged stands by the

individual tree selection method will be successful in obtaining western

hemlock regeneration [

38,

64]. In the grand fir (Abies

grandis)-cedar-hemlock ecosystem, Graham and Smith [

34] found that the

individual tree selection method of harvest promotes the regeneration

and growth of shade-tolerant species, such as western hemlock. The seed

tree method will work, but rarely is used in harvesting of western

hemlock stands because many seed trees blow down during wind storms

[

64].

A common problem in regeneration of western hemlock is overtopping by

competing vegetation such as alder, thimbleberry (Rubus parviflorus),

and salmonberry (Ribes spectabilis). When exposed to full sunlight

after clearcutting, these brush species tend to form dense thickets and

exclude hemlock regeneration. These species can be controlled with

herbicides [

64].

Western hemlock responds well to release after long periods of

suppression. Advance regeneration up to 4.5 feet (1.4 m) tall appears

to respond better to release than taller individuals. Poor response to

release has been noted for suppressed trees over 100 years old [

57].

- 書目引用

- Tesky, Julie L. 1992. Tsuga heterophylla. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Occurrence in North America

(

英語

)

由Fire Effects Information System Plants提供

AK CA ID MT OR WA AB BC

- 書目引用

- Tesky, Julie L. 1992. Tsuga heterophylla. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Other uses and values

(

英語

)

由Fire Effects Information System Plants提供

Alaska Indians made coarse bread from the inner bark of western hemlock

[

72]. Young western hemlock saplings can be sheared to make excellent

hedges. In Britain western hemlock is often planted as an ornamental

[

46].

- 書目引用

- Tesky, Julie L. 1992. Tsuga heterophylla. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Phenology

(

英語

)

由Fire Effects Information System Plants提供

More info on this topic. More info for the terms:

cone,

phenology,

seed,

treeThe reproductive cycle of western hemlock occurs over 15 to 16 months

from the time of cone initiation in early summer, until seeds are shed

in the fall of the following year. Fertilization and seed development

occur in the second year. Phenology varies between coastal and interior

regions [

56,

57,

76]. Trees in the interior region or at higher

elevations begin development later in the spring and complete

development earlier in the fall than do trees growing in coastal and

low-elevation regions [

56].

At low-elevation coastal British Columbia locations, pollination

commonly occurs in early to mid-April, whereas in the interior of

British Columbia, it may occur from May until mid-June. Records from

western Washington and Oregon show that pollination may occur from

mid-April until late May [

56]. Fertilization occurs in coastal western

hemlock about mid-May. The time from pollination to seed release ranges

from 120 to 160 days in western hemlock. It can vary according to

weather and temperature during cone maturation. Dry, warm weather in

late summer may cause more rapid drying and earlier opening of cones

with consequently, earlier seed release. Wet, cool weather may delay

cone opening and seed release. Most seeds are shed in the fall when

cones first open [

50,

56,

76]. Cones may close in wet weather and reopen

more fully with subsequent dry weather. As a result, seeds may be shed

throughout the winter or even during the next spring. Mature cones

often persist on the tree throughout the second year but contain few

viable seeds [

56,

57].

- 書目引用

- Tesky, Julie L. 1992. Tsuga heterophylla. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Plant Response to Fire

(

英語

)

由Fire Effects Information System Plants提供

More info for the terms:

competition,

naturalBurning may or may not benefit natural regeneration of western hemlock.

The response of seedlings to burning varies according to aspect, slope,

latitude, climate, etc. After broadcast burning in coastal hemlock

zones, more seedlings were found in burned areas than in unburned areas

due to elimination of brush competition and reduction of dense patches

of slash [

76]. On Vancouver Island after the third growing season,

burned seedbeds had 58 percent more seedlings with better distribution

than unburned seedbeds [

57]. However, on a site near Vancouver, British

Columbia, due to sunscald, all new germinants on burned humus were dead

by mid-July [

76].

- 書目引用

- Tesky, Julie L. 1992. Tsuga heterophylla. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Post-fire Regeneration

(

英語

)

由Fire Effects Information System Plants提供

More info for the terms:

root crown,

secondary colonizerTree without adventitious-bud root crown

Secondary colonizer - off-site seed

- 書目引用

- Tesky, Julie L. 1992. Tsuga heterophylla. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Regeneration Processes

(

英語

)

由Fire Effects Information System Plants提供

More info for the terms:

cone,

duff,

epigeal,

layering,

litter,

natural,

root collar,

seed,

stratification,

treeSeed production and dissemination: Western hemlock is generally a good

cone and seed producer. Cones may form on open-grown trees that are

less than 20 years old, but good cone crops usually do not occur until

trees are between 25 and 30 years old. Individuals usually produce some

cones every year and heavy cone crops every 3 or 4 years. Each cone

contains 30 to 40 seeds. The number of viable seeds ranges from fewer

than 10 to approximately 20 per cone [

18,

56]. Seeds are light and

small, ranging from 189,000 to 508,000 cleaned seeds per pound, with an

average of 260,000 seeds per pound (371,000-900,000/kg, average 530,000

seeds/kg) [

56,

63].

Western hemlock seeds have large wings enabling them to be distributed

over long distances. In open, moderately windy areas, most seeds fall

within 1,968 feet (600 m) of the parent tree. Some seeds can travel as

far as 3,772 feet (1,150 m) under these conditions. In dense stands,

most seeds fall much closer to the base of the tree [

56].

Germination: Germination is epigeal. Stratification for 3 to 4 weeks

at 33 to 39 degrees Fahrenheit (1-4 deg C) improves germination. The

optimum temperature for germination is 68 degrees Fahrenheit (20 deg C)

[

57,

63]. For each 9 degrees Fahrenheit (5 deg C) below the optimum, the

number of days required for germination is nearly doubled [

63]. Given

sufficient time (6-9 months) and an absence of pathogens, western hemlock

will germinate at temperatures just above freezing. Western hemlock

seeds remain viable only into the first growing season after seedfall

[

57]. Viability seems to vary between 36 and 55 percent with an average

of about 46 percent [

76].

Western hemlock seed appears to germinate well and seedlings grow well

on almost all natural seedbeds whether rotten wood, undisturbed bed duff

and litter, or bare mineral soil. The principal requirement for

adequate development on any seedbed appears to be adequate moisture.

For drier situations, mineral soils appear to be best for hemlock

seedlings [

76].

Seedling development: Most seedling mortality occurs in the first 2

years after germination [

76]. Seedlings are very shade tolerant but are

sensitive to heat, cold, drought and wind [

56]. In British Columbia,

the main cause of mortality appeared to be either drought or frost [

76].

Initial growth is slow; 2-year-old seedlings are commonly less than 8

inches (20 cm) tall. Once established, seedlings in full light may have

an average growth rate of 24 inches (60 cm) or more annually [

57]. In

inland regions, one study showed partial shade to be beneficial in

reducing mortality caused by high temperatures and drought. Once

seedlings are over 2 years old, survival appears to be very good [

76].

Vegetative reproduction: Western hemlock will reproduce vegetatively by

layering or cuttings. Seedlings that die back to the soil surface

commonly sprout from buds near the root collar. Sprouting does not

occur from the roots or the base of larger saplings. Western hemlock

grafts readily. Growth of grafted material is better than that of

rooted material [

57].

- 書目引用

- Tesky, Julie L. 1992. Tsuga heterophylla. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Regional Distribution in the Western United States

(

英語

)

由Fire Effects Information System Plants提供

More info on this topic. This species can be found in the following regions of the western United States (according to the Bureau of Land Management classification of Physiographic Regions of the western United States):

1 Northern Pacific Border

2 Cascade Mountains

4 Sierra Mountains

5 Columbia Plateau

8 Northern Rocky Mountains

- 書目引用

- Tesky, Julie L. 1992. Tsuga heterophylla. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Successional Status

(

英語

)

由Fire Effects Information System Plants提供

More info on this topic. More info for the terms:

climax,

forest,

successionWestern hemlock is very shade tolerant. Only Pacific yew (Taxus

brevifolia) and Pacific silver fir are considered to have equal or

greater tolerance of shade than western hemlock. Western hemlock is

generally considered a climax species either alone or in combination

with its shade-tolerant associates, but it can be found in all stages of

succession [

57]. It is an aggressive pioneer because of its quick

growth in full overhead light and its ability to survive on a wide

variety of seedbed conditions [

29,

57]. It also invades seral stages of

forest succession after a forest canopy has formed [

35]. If several

centuries pass without a major disturbance, a climax of

self-perpetuating, essentially pure western hemlock can result [

10]. On

drier upland slopes in Glacier National Park, western hemlock often

achieves dominance over western redcedar. Western hemlock rarely

replaces western redcedar entirely [

35]. In Idaho, western white pine

(Pinus monticola) stands are slowly replaced by a western

hemlock-western redcedar climax [

52].

- 書目引用

- Tesky, Julie L. 1992. Tsuga heterophylla. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Taxonomy

(

英語

)

由Fire Effects Information System Plants提供

More info for the term:

naturalThe scientific name for western hemlock is Tsuga heterophylla (Raf.)

Sarg. [

57,

60]. There are no recognized subspecies, varieties, or forms.

A natural hybrid between western hemlock and mountain hemlock (Tsuga mertensiana),

Tsuga x jeffreyi (Henry) Henry, has been reported [

57].

- 書目引用

- Tesky, Julie L. 1992. Tsuga heterophylla. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Value for rehabilitation of disturbed sites

(

英語

)

由Fire Effects Information System Plants提供

More info for the term:

naturalWestern hemlock is suitable for planting on moist, nutrient very poor to

nutrient medium sites in pure or mixed species stands (mainly with

Pacific silver fir [Abies amabilis], Sitka spruce [Picea sitchensis],

alder [Alnus spp.], or western redcedar). Natural regeneration is

preferred over planted stock [

44]. Western hemlock is difficult to grow

in outdoor nurseries. Container-grown stock appears to result in higher

quality seedlings with less damage to roots and better survival than

bareroot stock [

57]. Methods for collecting, storing and planting

western hemlock seeds and seedlings have been detailed [

63].

- 書目引用

- Tesky, Julie L. 1992. Tsuga heterophylla. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Wood Products Value

(

英語

)

由Fire Effects Information System Plants提供

Western hemlock wood is recognized as an all-purpose raw material. It

is one of the best pulpwoods for paper and paper board products [

57,

72].

It is the principal source of alpha cellulose fiber used in the

manufacture of rayon, cellophane, and many plastics [

10]. Other uses

are lumber for general construction, railway ties, mine timbers, and

marine piling. The wood is suited also for interior finish, boxes and

crates, kitchen cabinets, flooring, and ceiling, gutter stock, and

veneer for plywood [

57,

72].

- 書目引用

- Tesky, Julie L. 1992. Tsuga heterophylla. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Distribution

(

西班牙、卡斯蒂利亞西班牙語

)

由IABIN提供

Chile Central

Associated Forest Cover

(

英語

)

由Silvics of North America提供

Western hemlock is either a major or a minor component in at least 20

forest cover types of the Society of American Foresters (6).

Pacific

Coast

Rocky Mountains

202 White Spruce-Paper Birch

x

205 Mountain Hemlock

x

x

206 Engelmann Spruce-Subalpine Fir

x

210 Interior Douglas-Fir

x

212 Western Larch

x

213 Grand Fir

x

215 Western White Pine

x

218 Lodgepole Pine

x

x

221 Red Alder

x

222 Black Cottonwood-Willow

x

223 Sitka Spruce

x

224 Western Hemlock

x

x

225 Western Hemlock-Sitka Spruce

x

226 Coastal True Fir-Hemlock

x

227 Western Redcedar-Western Hemlock

x

x

228 Western Redcedar

x

229 Pacific Douglas-Fir

x

230 Douglas-Fir-Western Hemlock

x

x

231 Port Orford-Cedar

x

232 Redwood

x

The forest cover types may be either seral or climax.

Tree associates specific to the coast include Pacific silver fir (Abies

amabilis), noble fir (A. procera), bigleaf maple (Acer

macrophyllum), red alder (Alnus rubra), giant chinkapin (Castanopsis

chrysophylla), Port-Orford-cedar (Chamaecyparis lawsoniana), Alaska-cedar

(C. nootkatensis), incense-cedar (Libocedrus decurrens), tanoak

(Lithocarpus densiflorus), Sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis),

sugar pine (Pinus lambertiana), redwood (Sequoia

sempervirens), and California laurel (Umbellularia californica).

Associates occurring in both the Pacific coast and Rocky Mountain

portions of its range include grand fir (Abies grandis), subalpine

fir (A. lasiocarpa), paper birch (Betula papyrifera), western

larch (Larix occidentalis), Engelmann spruce (Picea

engelmannii), white spruce (P. glauca), lodgepole pine (Pinus

contorta), western white. pine (P. monticola), ponderosa pine

(P. ponderosa), black cottonwood (Populus trichocarpa), Douglas-fir

(Pseudotsuga menziesii), Pacific yew (Taxus brevifolia), western

redcedar (Thuja plicata), and mountain hemlock (Tsuga

mertensiana).

Western hemlock is a component of the redwood forests on the coasts of

northern California and adjacent Oregon. In Oregon and western Washington,

it is a major constituent of the Picea sitchensis, Tsuga heterophylla,

and Abies amabilis Zones and is less important in the Tsuga

mertensiana and Mixed-Conifer Zones (7). In British Columbia, it is a

major element of the Tsuga heterophylla-Picea sitchensis, Tsuga

heterophylla-Abies amabilis, Tsuga heterophylla, Abies amabilis-Tsuga

heterophylla, and Abies amabilis-Tsuga mertensiana Vegetation

Zones; it is confined to a distinct understory portion or to moist sites

in the Pseudotsuga menziesii-Tsuga heterophylla and Pseudotsuga

menziesii Zones (25). In the Rocky Mountains, it is present in

the Thuja plicata and Tsuga heterophylla Vegetation Zones

and the lower portion of the Abies lasiocarpa Zone (26).

Various persons have described the plant associations and biogeocoenoses

in which western hemlock is found; more than 75 are listed for the west

coast and more than 30 for the Rocky Mountains (25). Little effort

has been made to correlate the communities with one another.

Because of its broad range, western hemlock has a substantial number of

understory associates. In its Pacific coast range, common shrub species

include the following (starred species are also common associates in the

Rocky Mountains): vine maple (Acer circinatum), Sitka alder* (Alnus

sinuata), Oregongrape (Berberis nervosa), snowbrush ceanothus*

(Ceanothus velutinus), salal (Gaultheria shallon), oceanspray*

(Holodiscus discolor), rustyleaf menziesia* (Menziesia

ferruginea), devilsclub* (Oplopanax horridus), Oregon boxwood*

(Pachistima myrsinites), Pacific ninebark* (Physocarpus

capitatus), Pacific rhododendron (Rhododendron macrophyllum), stink

currant (Ribes bracteosum), prickly currant* (R. lacustre),

thimbleberry* (Rubus parviflorus), salmonberry (R.

spectabilis), trailing blackberry (R. ursinus), Pacific red

elder (Sambucus callicarpa), common snowberry* (Symphoricarpos

albus), Alaska blueberry (Vaccinium alaskaense), big

huckleberry (V. membranaceum), ovalleaf huckleberry (V.

ovalifolium), evergreen huckleberry (V. ovatum), and red

huckleberry (V. parvifolium). The following are other common

associates in the Rocky Mountains: creeping western barberry (Berberis

repens), russet buffaloberry (Shepherdia canadensis), birchleaf

spirea (Spiraea betulifolia), dwarf blueberry (Vaccinium

caespitosum), globe huckleberry (V. globulare), and grouse

whortleberry (V. scoparium).

Common herbaceous species include the ferns: maidenhair fern (Adiantum

pedatum), ladyfern (Athyrium filix-femina), deerfern (Blechnum

spicant), mountain woodfern (Dryopteris austriaca), oakfern

(Gymnocarpium dryopteris), swordfern (Polystichum munitum),

and bracken (Pteridium aquilinum). Herb associates include

vanillaleaf (Achlys triphylla), wild ginger (Asarum caudatum),

princes-pine (Chimaphila umbellata), little princes-pine (C.

menziesii), queenscup (Clintonia uniflora), cleavers bedstraw

(Galium aparine), sweetscented bedstraw (G. triflorum), twinflower

(Linnaea borealis), Oregon oxalis (Oxalis oregana), one-sided

pyrola (Pyrola secunda), feather solomonplume (Smilacina

racemosa), starry solomonplume (S. stellata), trefoil

foamflower (Tiarella trifoliata), coolwort foamflower (T.

unifoliata), white trillium (Trillium ovatum), roundleaf

violet (Viola orbiculata), evergreen violet (V. sempervirens),

and common beargrass (Xerophyllum tenax).

Climate

(

英語

)

由Silvics of North America提供

Western hemlock thrives in a mild, humid climate where frequent fog and

precipitation occur during the growing season. Best stands are in the

humid and superhumid coastal regions. In subhumid regions with relatively

dry growing seasons, western hemlock is confined primarily to northerly

aspects, moist stream bottoms, or seepage sites.

Within the coastal range of western hemlock, mean annual total

precipitation ranges from less than 380 mm (15 in) in Alaska to at least

6650 mm (262 in) in British Columbia. The range in the Rocky Mountains is

560 mm (22 in) to at least 1730 mm (68 in) (25).

Mean annual temperatures range from 0.3° to 11.3° C (32.5°

to 52.3° F) on the coast and 2.2° to 8.2° C (36.0° to

46.8° F) in the Rocky Mountains. Observed mean July temperatures lie

between 11.3° and 19.7° C (52.3° and 67.5° F)

along the coast and 14.4° and 20.6° C (58.0° and 69.0°

F) in the interior. Mean January temperatures reported for the two areas

range from -10.9° to 8.5° C (12.4° to 47.3° F) and

-11.1° to -2.4° C (12.0° to 27.6° F), respectively.

Recorded absolute maximum temperature for the coast is 40.6° C (105.0°

F) and for the Rocky Mountains, 42.2° C (108.0° F). Absolute

minimum temperatures tolerated by western hemlock are -38.9° C (-38.0°

F) for the coast and -47.8° C (-54.0° F) for the interior.

The frost-free period within the coastal range of western hemlock

averages less than 100 to more than 280 days (25). In the Rocky Mountains,

the frost-free period is 100 to 150 days (20).

Damaging Agents

(

英語

)

由Silvics of North America提供

Many agents adversely affect the growth,

health, and quality of western hemlock trees and stands.

Because of its thin bark and shallow roots, western hemlock is highly

susceptible to fire. Even light ground fires are damaging. Prescribed

burning is an effective means of eliminating western hemlock advance

regeneration from a site.

Because of its shallow roots, pole-size and larger stands of western

hemlock are subject to severe windthrow. Thousands of hectares of young

stands dominated by coastal western hemlock have originated after such

blowdown.

Western hemlock suffers frost damage in the Rocky Mountains, especially

along the eastern edge of its range where frost-killed tops are reported

(20,26). Snowbreak occurs locally; it appears to be most common east of

the Cascade and Coast Mountains, and especially in the Rocky Mountains. On

droughty sites, top dieback is common; in some exceptionally dry years,

entire stands of hemlock saplings die. Suddenly exposed saplings may

suffer sunscald. Excessive amounts of soil moisture drastically reduce

growth.

Western hemlock is one of the species most sensitive to damage by sulfur

dioxide (16). Spring applications of the iso-octyl esters of 2,4-D and

2,4,5-T in diesel oil can kill leader growth of the last 3 years.

Severe fluting of western hemlock boles is common in southeast Alaska,

much less common on Vancouver Island, and relatively uncommon in

Washington and Oregon. There appears to be a clinal gradient from north to

south; the causal factor is not known.

No foliage diseases are known to cause serious problems for western

hemlock.

Dwarf mistletoe (Arceuthobium tsugense) is a serious parasite

along the Pacific coast from California nearly to Glacier Bay, AK; its

presence on western hemlock in the Rocky Mountain States is unconfirmed.

It increases mortality, reduces growth, lowers fiber quality, and provides

an entryway for decay fungi. Uninfected to lightly infected trees may have

a greater growth in volume (40 percent) and height (84 percent) than

severely infected trees; in mature stands, volume losses as high as 4.2 m³/ha

(60 ft³/acre) per year have been reported (29). Dwarf mistletoe in

western hemlock is easy to control; success is nearly 100 percent if

methods of sanitation are good.

Armillaria mellea, Heterobasidion annosum, Phaeolus schweinitzii,

Laetiporus sulphureus, Inonotus tomentosus, Poria subacida, and Phellinus

weiri are the major root and butt pathogens of western hemlock. Armillaria

mellea occurs widely, seldom kills trees directly, and is not a major

source of cull.

Heterobasidion annosum, the most serious root pathogen of

western hemlock, can limit the alternatives available for intensive

management (3). The incidence of infected trees in unthinned western

hemlock stands ranges from 0 to more than 50 percent. In some thinned

stands, every tree is infected. Heterobasidion annosum spores

colonize freshly cut stumps and wounds; the spreading mycelium infects

roots and spreads to adjacent trees through root grafts. Treating stumps

and wounds with chemicals can reduce the rate of infection.

Phellinus weiri is a common root pathogen where Douglas-fir is

or was a major component of the stand. In the Rocky Mountains, a similar

relationship may exist with western redcedar. Phellinus weiri rapidly

extends up into the bole of western hemlock. The first log is frequently

hollow; only the sapwood remains. The only practical controls for P.

weiri are pulling out the stumps and roots or growing resistant

species.

High risk bole pathogens include Echinodontium tinctorium,

Heterobasidion annosum, and Phellinus weiri. Echinodontium

tinctorium causes extensive decay in overmature stands in the Rocky

Mountains. It is less destructive in immature stands, although it is found

in trees 41 to 80 years old; 46 percent of the trees in this age group in

stands studied were infected. Echinodontium tinctorium is of

little consequence on the coast. Heterobasidion annosum spreads

from the roots into the bole of otherwise vigorous trees. On Vancouver

Island, an average of 24 percent (range 0.1 to 70 percent) of the volume

of the first 5-m (16-ft) log can be lost to H. annosum (24).

Rhizina undulata, a root rot, is a serious pathogen on both

natural and planted seedlings on sites that have been burned. It can kill

mature trees that are within 8 m (25 ft) of the perimeter of a slash burn

(3).

Sirococcus strobilinus, the sirococcus shoot blight, causes

dieback of the tip and lateral branches and kills some trees in Alaska;

the potential for damage is not known (27).

Of the important insects attacking western hemlock, only three do not

attack the foliage. A seed chalcid (Megastigmus tsugae) attacks

cones and seeds; the larva feeds inside the seed. This insect normally is

not plentiful and is of little consequence to seed production (14). A

weevil (Steremnius carinatus) causes severe damage in coastal

British Columbia by girdling seedlings at the ground line. In the Rocky

Mountains, the western larch borer (Tetropium velutinum) attacks

trees that are weakened by drought, defoliated by insects, or scorched by

fire; occasionally it kills trees (9).

Since 1917, there have been only 10 years in which an outbreak of the

western blackheaded budworm (Acleris gloverana) did not cause

visible defoliation somewhere in western hemlock forests (28). Extensive

outbreaks occur regularly in southeast Alaska, on the coast of British

Columbia, in Washington on the south coast of the Olympic Peninsula and in

the Cascade Range, and in the Rocky Mountains. In 1972, nearly 166 000 ha

(410,000 acres) were defoliated on Vancouver Island alone. Damage by the

larvae is usually limited to loss of foliage and related growth reduction

and top kill. Mortality is normally restricted to small stands with

extremely high populations of budworms.

The western hemlock looper (Lambdina fiscellaria lugubrosa) has

caused more mortality of western hemlock than have other insect pests.

Outbreaks last 2 to 3 years on any one site and are less frequent than

those of the budworm. The greatest number of outbreaks occurs on the south

coast of British Columbia; the western hemlock looper is less prevalent

farther north. Heavy attacks have been recorded for Washington and Oregon

since 1889. The insect is less destructive in the interior forests.

Although mortality is greatest in old growth, vigorous 80- to 100-year-old

stands are severely damaged.

Two other loopers, the greenstriped forest looper (Melanolophia

imitata) and the saddleback looper (Ectropis crepuscularia), cause

top kill and some mortality. The phantom hemlock looper (Nepytia

phantasmaria) in the coastal forest and the filament bearer (Nematocampa

filamentaria) play minor roles, usually in association with the

western hemlock looper (28).

The hemlock sawfly (Neodiprion tsugae) occurs over most of the

range of western hemlock. Its outbreaks often occur in conjunction with

outbreaks of the western blackheaded budworm. The larvae primarily feed on

old needles; hence, they tend to reduce growth rather than cause mortality

(9). The hemlock sawfly is considered the second most destructive insect

in Alaska (13).

Black bear girdle pole-size trees and larger saplings or damage the bark

at the base of the trees, especially on the Olympic Peninsula of

Washington. Roosevelt elk and black-tailed deer browse western hemlock in

coastal Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia. The snowshoe hare and

the brush rabbit damage hemlock seedlings, principally by clipping off the

main stem; clipping of laterals rarely affects survival of seedlings (5).

Mountain beaver clip the stems and lateral branches of seedlings and

girdle the base of saplings along the coast south of the Fraser River in

British Columbia to northern California. Four years after thinning,

evidence of girdling and removal of bark was present on 40 percent of the

trees (5). Mortality results from both kinds of damage.

Flowering and Fruiting

(

英語

)

由Silvics of North America提供

Western hemlock is monoecious; male and

female strobili develop from separate buds of the previous year. Female

strobili occupy terminal positions on lateral shoots, whereas the male

strobili cluster around the base of the needles (4). Flowering and

pollination begin from mid-April to late April in western Oregon and

continue into late May and June in coastal Alaska. The solitary, long (19

to 32 mm; 0.75 to 1.25 in), pendent cones mature 120 to 160 days after

pollination. Time of maturity of cones on the same branch is variable;

ripe cones change from green to golden brown. The cone-scale opening

mechanism does not appear to develop fully until late in the ripening

period. Seeds are usually fully ripe by mid-September to late September,

but cone scales do not open until late October. Empty cones often persist

on the tree for 2 or more years.

Although flowering may begin on 10-year-old trees, regular cone

production usually begins when trees reach 25 to 30 years of age. Mature

trees are prolific producers of cones. Some cones are produced every year,

and heavy crops occur at average intervals of 3 to 4 years; however, for a

given location, the period between good crops may vary from 2 to 8 years

or more. For example, in Alaska, good seed crops occur on an average of 5

to 8 years.

Genetics

(

英語

)

由Silvics of North America提供

A natural cross between western hemlock and mountain hemlock, Tsuga

x jeffreyi (Henry) Henry, has been reported from the Mount

Baker area in Washington. Analysis of polyphenolic pigment suggests that

chemical hybrids between western hemlock and mountain hemlock occur but

are rare. Intergeneric hybridization between western hemlock and spruce

has been discussed in the literature; although similarities exist between

the two genera, they do not suggest hybridization (31).

Albino individuals or those similarly deficient in chlorophyll have been

observed in the wild.

Growth and Yield

(

英語

)

由Silvics of North America提供

Western hemlock may form pure stands or be a

component of mixed stands. Young stands vary in stocking, but

understocking is infrequent. Natural 20-year-old stands can have 14,800 to

24,700 or more stems per hectare (6,000 to 10,000/acre). Stocking levels

of 1,480 to 1,790 stems per hectare (600 to 725/acre) at crown closure are

believed to provide the best yields if commercial thinnings are part of

the management regime (12). If thinnings are not planned, stocking levels

as low as 740 well-distributed trees per hectare (300/acre) can provide

maximum yields at rotation age (27).

The response of western hemlock to nitrogen fertilizer is extremely

variable. It appears to vary by geographic location and stocking level.

For overstocked stands, a combination of precommercial thinning and

fertilizer often gives the best response.

Comparative yield data from paired British plantations strongly suggest

that western hemlock commonly outproduces two of its most important

associates, Douglas-fir and Sitka spruce (1). Natural stands of western

hemlock along the Pacific coast attain appreciably higher yields than

Douglas-fir stands having the same site index (34); the weighted mean

annual increment of western hemlock for some common forest soils in

Washington is 33 to 101 percent more than the mean annual increment for

Douglas-fir (30). On the Olympic Peninsula, western hemlock out-produces

Douglas-fir by 25 to 40 percent. Similar relationships occur in south

coastal British Columbia (12). The higher mean annual increment of western

hemlock apparently is due to the ability of western hemlock stands to

support more trees per hectare; individual trees also have better form

than other species and hence better volume (at least 4 to 14 percent)

(34).

Mixed stands of western hemlock and Sitka spruce are especially

productive. In the Picea sitchensis Zone of Oregon and Washington,

the mean annual increment of such stands frequently exceeds 42 m³/ha

(600 ft³/acre). At higher elevations and farther north, mixed stands

of western hemlock and Pacific silver fir are also highly productive.

Yield data for natural stands are given in table 1. Volumes predicted

for normally stocked stands may actually underestimate potential yields by

20 to 50 percent. Data from British Columbia suggest greater yields can be

had if a high number of stems per hectare are maintained (12). Yields of

western hemlock on the best sites can exceed 1848 m³/ha (26,400 ft³/acre)

at 100 years of age.

Table 1- Characteristics of fully stocked, 100-year-old

western hemlock stands in Oregon (OR), Washington (WA), British Columbia

(BC), and Alaska (AK) (adapted from 2)

Average site index at

base age 100 years¹

Item

61 m or 200 ft

52 m or 170 ft

43 m or 140 ft

34 m or 110 ft

26 m or

85 ft

Avg. height, m

OR/WA

58.8

49.7

40.8

31.7

-

BC

-

50.0

40.8

31.7

22.3

AK

-

-

38.4

29.3

20.7

Avg. d.b.h., cm

OR/WA

58

54

49

42

-

BC/AK

-

44

40

31

22

Stocking², trees/ha

OR/WA

299

339

400

526

-

BC/AK

-

482

573

865

1,384

Basal area², m²/ha

OR/WA

83.3

81.7

79.0

75.3

-

BC/AK

-

75.5

73.0

67.5

59.9

Whole tree volume², ft³/acre

OR/WA

1771

1498

1218

938

-

BC

-

1449

1228

938

612

AK

-

-

1158

868

560

Avg. height, ft

OR/WA

192.0

163.1

133.9

104.0

-

BC

-

164.0

133.9

104.0

73.2

AK

-

-

126.0

96.1

67.9

Avg. d.b.h., in

OR/WA

23.0

21.4

19.2

16.5

-

BC/AK

-

17.5

15.6

12.4

8.8

Stocking², trees/acre

OR/WA

121

137

162

213

-

BC/AK

-

195

232

350

560

Basal area², ft²/acre

OR/WA

362.9

355.9

344.1

328.0

-

BC/AK

-

328.9

318.0

294.0

261.0

Whole tree volume², ft³/acre

OR/WA

25,295

21,394

17,406

13,405

-

BC

-

20,693

17,549

13,405

8,746

AK

-

-

16,549

12,405

8,003

¹Site indices

range within 4.6 m (15 ft) of the averages.

²Trees larger than 3.8 cm (1.5 in) in d.b.h.

Western hemlock forests are among the most productive forests in the

world. The biomass production of several western hemlock stands with a

site index (base 100 years) of 43 m (140 ft) was investigated at the

Cascade Head Experimental Forest near Lincoln City, OR. The biomass of

standing trees of a 26-year-old, nearly pure western hemlock stand was 229

331 kg/ha (204,614 lb/acre) and that of a 121-year-old stand with a spruce

component of 14 percent was 1 093 863 kg/ha (975,966 lb/acre). Net primary

productivity per year for these two stands was estimated to be 37 460 and

22 437 kg/ha (33,423 and 20,019 lb/acre). Net primary productivity appears

to peak at about 30 years, then declines rapidly for about 50 years.

Foliar biomass in the stands at Cascade Head averages 22 724 kg/ha (20,275

lb/acre) with a leaf area of 46.5 m²/m² (46.5 ft²/ft²)

(8, 10). By comparison, available data indicate much lower values for

highly productive Douglas-fir stands- 12 107 kg/ha and 21.4 m²/m²

(10,802 lb/acre and 21.4 ft²/ft² ), respectively.

On the best sites, old-growth trees commonly reach diameters greater

than 100 cm (39.6 in); maximum diameter is about 275 cm (108 in). Heights

of 50 to 61 m (165 to 200 ft) are not uncommon; maximum height is reported

as 79 m (259 ft). Trees over 300 years old virtually cease height growth

(27). Maximum ages are typically over 400 but less than 500 years. The

maximum age recorded, in excess of 700 years, is from the Queen Charlotte

Islands (16). Several major associates (Douglas-fir, western redcedar,

Alaska-cedar) typically reach much greater ages.

Reaction to Competition

(

英語

)

由Silvics of North America提供

Western hemlock is rated to be very

tolerant of shade. Only Pacific yew and Pacific silver fir are considered

to have equal or greater tolerance of shade than western hemlock.

Western hemlock responds well to release after a long period of

suppression. Advance regeneration 50 to 60 years old commonly develops

into a vigorous, physiologically young-growth stand after complete removal

of the overstory; however, poor response to release has been noted for

suppressed trees over 100 years old. Advance regeneration up to 1.4 m (4.5

ft) tall appears to respond better to release than taller individuals.

Because of its shade tolerance, it is an ideal species for management that

includes partial cutting; however, if it is present and the management

goal is for a less tolerant species, normal partial cutting practices are

not recommended.

Under conditions of dense, even-aged stocking, early natural pruning

occurs, tree crowns are usually narrow, and stem development is good.

Given unrestricted growing space, the quality of western hemlock logs is

reduced because of poorly formed stems and persistent branches. Trees that

develop in an understory vary greatly in form and quality.

The successional role of western hemlock is clear; it is a climax

species either alone or in combination with its shade-tolerant associates.

Climax or near-climax forest communities along the Pacific coast include

western hemlock, western hemlock-Pacific silver fir, western

hemlock-western redcedar, Pacific silver fir-western hemlock-Alaska-cedar,

and western hemlock-mountain hemlock. The longevity of some associates of

western hemlock makes it difficult to determine if some of these

near-climax communities will develop into pure western hemlock stands or

if western hemlock will ultimately be excluded.

Climax or near-climax communities in the Rocky Mountains include western

hemlock, western hemlock-western redcedar, and occasionally subalpine

fir-western hemlock. In the last community, western hemlock plays a

distinctly minor role (26).

Rooting Habit

(

英語

)

由Silvics of North America提供

Western hemlock is a shallow-rooted species; it

does not develop a taproot. The roots, especially the fine roots, are

commonly most abundant near the surface and are easily damaged by

harvesting equipment and fire.

Seed Production and Dissemination

(

英語

)

由Silvics of North America提供

There are 56,760 to 83,715

cones per hectoliter (20,000 to 29,500/bu). Each cone contains 30 to 40

small seeds. Extraction and cleaning yields an average of 0.79 kg of seed

per hectoliter (0.61 lb/bu) of cones. There are 417,000 to over 1,120,000

with an average 573,000 seeds per kilogram (189,000 to 508,000/lb; average

260,000). Slightly less than one-half of the seeds extracted from the

cones are viable.

In coastal Oregon, more than 19.8 million seeds per hectare (8

million/acre) were released during each of two good seed years from

100-year-old stands, or about 30.3 kg/ha (27 lb/acre). In 1951, a

hemlock-spruce stand in Alaska produced 96.4 kg/ha (86 lb/acre) of western

hemlock seed. In the Rocky Mountains, western hemlock consistently

produces more seed than its associates in the Tsuga heterophylla Zone.

Cone scales of western hemlock open and close in response to dry and wet

atmospheric conditions. Under wet conditions, seed may be retained in the

cones until spring. Western hemlock seed falls at a rate of 80 cm (31 in)

per second (27). Released in a strong wind, it can be blown more than 1.6

km (1 mi). In a wind of 20 km (12.5 mi) per hour, seed released at a

height of 61 m (200 ft) traveled up to 1160 m (3,800 ft); most fell within

610 m (2,000 ft) of the point of release (19). Seedfall under a dense

canopy is 10 to 15 times greater than that within 122 m (400 ft) of the

edge of timber in an adjacent clearcut.

Seedling Development

(

英語

)

由Silvics of North America提供

Western hemlock seeds are not deeply

dormant; stratification for 3 to 4 weeks at 1° to 4° C (33°

to 39° F) improves germination and germination rate. The germination

rate is sensitive to temperature; optimum temperature appears to be 20°

C (68° F). For each 5° C (9° F) drop below the optimum, the

number of days required for germination is nearly doubled. Given

sufficient time (6 to 9 months) and an absence of pathogens, western

hemlock will germinate at temperatures just above freezing (4).

Germination is epigeal. Western hemlock seeds remain viable only into the

first growing season after seedfall.

Provided adequate moisture is available, seed germination and germinant

survival are excellent on a wide range of materials. Seeds even germinate

within cones still attached to a tree. Western hemlock germinates on both

organic and mineral seedbeds; in Alaska, establishment and initial growth

are better on soils with a high amount of organic matter. Mineral soils

stripped of surface organic material commonly are poor seedbeds because

available nitrogen and mineral content is low.

In Oregon and Washington, exposed organic materials commonly dry out in

the sun, resulting in the death of the seedling before its radicle can

penetrate to mineral soil and available moisture. In addition, high

temperatures, which may exceed 66° C (150° F) at the surface of

exposed organic matter, are lethal. Under such moisture and temperature

conditions, organic seedbeds are less hospitable for establishment of

seedlings than mineral seedbeds (27). Burning appears to encourage natural

regeneration on Vancouver Island; after the third growing season, burned

seedbeds had 58 percent more seedlings with better distribution than

unburned seedbeds (17).

Decaying logs and rotten wood are often favorable seedbeds for western

hemlock. Decayed wood provides adequate nutrition for survival and growth

of seedlings (23). In brushy areas, seedlings commonly grow on rotten wood

where there is minimum competition for moisture and nutrients. Seedlings

established on such materials frequently survive in sufficient numbers to

form a fully stocked stand by sending roots into the soil around or

through a stump or log.

Because western hemlock can thrive and regenerate on a diversity of

seedbeds, natural regeneration can be obtained through various

reproduction methods, ranging from single-tree selection to clearcutting.

Through careful harvesting of old-growth stands, advance regeneration

often results in adequately stocked to overstocked stands.

Western hemlock is difficult to grow in outdoor nurseries.