pt-BR

nomes no trilho de navegação

Douryar Lord Howe (Porphyrio albus) a oa un evn hag a veve en Aostralia, en enez Lord Howe. Aet e vije da get e penn kentañ an XIXvet kantved.

Douryar Lord Howe (Porphyrio albus) a oa un evn hag a veve en Aostralia, en enez Lord Howe. Aet e vije da get e penn kentañ an XIXvet kantved.

La polla blanca (Porphyrio albus) és un ocell extint de la família dels ràl·lids (Rallidae) que habitava l'illa de Lord Howe, a l'est d'Austràlia. Va ser observada per última vegada en 1834.

La polla blanca (Porphyrio albus) és un ocell extint de la família dels ràl·lids (Rallidae) que habitava l'illa de Lord Howe, a l'est d'Austràlia. Va ser observada per última vegada en 1834.

Das Lord-Howe-Purpurhuhn (Porphyrio albus) ist eine ausgestorbene, flugunfähige Ralle, die auf der australischen Lord-Howe-Insel endemisch war.

Es ähnelte dem Purpurhuhn (Porphyrio porphyrio) abgesehen von seiner weißen oder weißblauen Farbe und den roten Augen und Beinen sehr. Es soll laut Keith Alfred Hindwood auch völlig blaue Vögel gegeben haben. Die Kopfoberseite war rot. Beine und Füße waren kräftiger ausgebildet, die Zehen kürzer während der Schnabel kleiner war. Die Flügel waren kürzer, die Flugfedern kleiner und weicher als beim Purpurhuhn (Porphyrio porphyrio).

Der Vogel wurde durch zwei Bälge, einige subfossile Knochen und diverse Gemälde bekannt. Er hatte keine Scheu vor Menschen. Obwohl der Vogel, als die Insel 1790 entdeckt wurde, nicht selten war, wurde die Art innerhalb von kürzester Zeit durch die Jagd durch Matrosen von Segel- und Walfangschiffen ausgerottet. Ratten und Katzen wurden auf der Insel erst wesentlich später eingeschleppt. Das Lord-Howe-Purpurhuhn war wahrscheinlich schon 1834 bei der Besiedlung der Lord-Howe-Insel vollständig ausgestorben.

Das Lord-Howe-Purpurhuhn (Porphyrio albus) ist eine ausgestorbene, flugunfähige Ralle, die auf der australischen Lord-Howe-Insel endemisch war.

The white swamphen (Porphyrio albus), also known as the Lord Howe swamphen, Lord Howe gallinule or white gallinule, is an extinct species of rail which lived on Lord Howe Island, east of Australia. It was first encountered when the crews of British ships visited the island between 1788 and 1790, and all contemporary accounts and illustrations were produced during this time. Today, two skins exist: the holotype in the Natural History Museum of Vienna, and another in Liverpool's World Museum. Although historical confusion has existed about the provenance of the specimens and the classification and anatomy of the bird, it is now thought to have been a distinct species endemic to Lord Howe Island and most similar to the Australasian swamphen. Subfossil bones have also been discovered since.

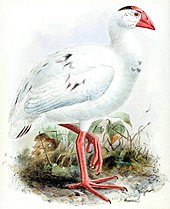

The white swamphen was 36 to 55 cm (14 to 22 in) long. Both known skins have mainly-white plumage, although the Liverpool specimen also has dispersed blue feathers. This is unlike other swamphens, but contemporary accounts indicate birds with all-white, all-blue, and mixed blue-and-white plumage. The chicks were black, becoming blue and then white as they aged. Although this has been interpreted as due to albinism, it may have been progressive greying in which feathers lose their pigment with age. The bird's bill, frontal shield and legs were red, and it had a claw (or spur) on its wing. Little was recorded about the white swamphen's behaviour. It may not have been flightless, but was probably a poor flier. This and its docility made the bird easy prey for visiting humans, who killed it with sticks. Reportedly once common, the species may have been hunted to extinction before 1834, when Lord Howe Island was settled.

Lord Howe Island is a small, remote island about 600 kilometres (370 mi) east of Australia. Ships first arrived on the island in 1788, including two which supplied the British penal colony on Norfolk Island and three transport ships of the British First Fleet. When HMS Supply passed the island, the ship's commander named it after First Lord of the Admiralty Richard Howe. Crews of the visiting ships captured native birds (including white swamphens), and all contemporary descriptions and depictions of the species were made between 1788 and 1790. The bird was first mentioned by the master of HMS Supply, David Blackburn, in a 1788 letter to a friend. Other accounts and illustrations were produced by Arthur Bowes Smyth, the fleet's naval officer and surgeon, who drew the first known illustration of the species; Arthur Phillip, governor of New South Wales; and George Raper, midshipman of HMS Sirius. Secondhand accounts also exist, and at least ten contemporary illustrations are known. The accounts indicate that the population varied, and individual bird plumage was white, blue, or mixed blue-and-white.[2][3]

In 1790, the white swamphen was scientifically described and named by the surgeon John White in a book about his time in New South Wales. He named the bird Fulica alba, the specific name being derived from the Latin word for white (albus). White found the bird most similar to the western swamphen (Porphyrio porphyrio, then in the genus Fulica). Although he apparently never visited Lord Howe Island, White may have questioned sailors and based some of his description on earlier accounts. He said he had described a skin at the Leverian Museum, and his book included an illustration of the specimen by the artist Sarah Stone. It is uncertain when (and how) the specimen arrived at the museum. This skin, the holotype specimen of the species, was purchased by the Natural History Museum of Vienna in 1806 and is catalogued as specimen NMW 50.761. The naturalist John Latham listed the bird as Gallinula alba in a later 1790 work, and wrote that it may have been a variety of purple swamphen (or "gallinule").[2][4][5]

One other white swamphen specimen is in Liverpool's World Museum, where it is catalogued as specimen NML-VZ D3213. Obtained by the naturalist Sir Joseph Banks, it later entered the collection of the traveller William Bullock and was purchased by Lord Stanley; Stanley's son donated it to Liverpool's public museums in 1850. Although White said that the first specimen was obtained from Lord Howe Island, the provenance of the second has been unclear; it was originally said to have come from New Zealand, resulting in taxonomic confusion. Phillip wrote that the bird could also be found on Norfolk Island and elsewhere, but Latham said it could be found only on Norfolk Island. When the first specimen was sold by the Leverian Museum, it was listed as coming from New Holland (which Australia was called at the time)—perhaps because it was sent from Sydney.[2][6] A note by the naturalist Edgar Leopold Layard on a contemporary illustration of the bird by Captain John Hunter inaccurately stated that it only lived on Ball's Pyramid, an islet off Lord Howe Island.[7][8]

The Zoologist Coenraad Jacob Temminck assigned the white swamphen to the swamphen genus Porphyrio as P. albus in 1820, and the zoologist George Robert Gray considered it an albino variety of the Australasian swamphen (P. melanotus) as P. m. varius alba in 1844. The belief that the bird was simply an albino was held by several later writers, and many failed to notice that White cited Lord Howe Island as the origin of the Vienna specimen.[2][9] In 1860 and 1873, the ornithologist August von Pelzeln said that the Vienna specimen had come from Norfolk Island, and assigned the species to the genus Notornis as N. alba; the takahē (P. hochstetteri) of New Zealand was also placed in that genus at the time.[10][11] In 1873, the naturalist Osbert Salvin agreed that the Lord Howe Island bird was similar to the takahē, although he had apparently never seen the Vienna specimen, basing his conclusion on a drawing provided by von Pelzeln. Salvin included a takahē-like illustration of the Vienna specimen by the artist John Gerrard Keulemans, based on von Pelzeln's drawing, in his article.[2][12]

In 1875, the ornithologist George Dawson Rowley noted differences between the Vienna and Liverpool specimens and named a new species based on the latter: P. stanleyi, named after Lord Stanley. He believed that the Liverpool specimen was a juvenile from Lord Howe Island or New Zealand, and continued to believe that the Vienna specimen was from Norfolk Island. Despite naming the new species, Rowley considered the possibility that P. stanleyi was an albino Australasian swamphen and considered the Vienna bird more similar to the takahē.[6][13] In 1901, the ornithologist Henry Ogg Forbes had the Liverpool specimen dismounted so he could examine it for damage. Forbes found it similar enough to the Vienna specimen to belong to the same species, N. alba.[14] The zoologist Walter Rothschild considered the two species distinct from each other in 1907, but placed them both in the genus Notornis. Rothschild thought that the image published by Phillip in 1789 depicted N. stanleyi from Lord Howe Island, and the image published by White in 1790 showed N. alba from Norfolk Island. He disagreed that the specimens were albinos, thinking instead that they were evolving into a white species. Rothschild published an illustration of N. alba by Keulemans where it is similar to a takahē, inaccurately showing it with dark primary feathers, although the Vienna specimen on which it was based is all white.[9] In 1910, the ornithologist Tom Iredale demonstrated that there was no proof of the white swamphen existing anywhere but on Lord Howe Island and noted that early visitors to Norfolk Island (such as Captain James Cook and Lieutenant Philip Gidley King) did not mention the bird.[15] In 1913, after examining the Vienna specimen, Iredale concluded that the bird belonged in the genus Porphyrio and did not resemble the takahē.[16]

In 1928, the ornithologist Gregory Mathews discussed a 1790 painting by Raper which he thought differed enough from P. albus in proportions and colouration that he named a new species based on it: P. raperi. Mathews also considered P. albus distinct enough to warrant a new genus, Kentrophorina, due to having a claw (or spur) on one wing.[17] In 1936, he conceded that P. raperi was a synonym of P. albus.[2] The ornithologist Keith Alfred Hindwood agreed that the bird was an albino P. melanotus in 1932, and pointed out that the naturalists Johann Reinhold Forster and Georg Forster (his son) did not record the bird when Cook's ship visited Norfolk Island in 1774. In 1940, Hindwood found the white swamphen so closely related to the Australasian swamphen that he considered them subspecies of the same species: P. albus albus and P. albus melanotus (since albus is the older name). Hindwood suggested that the population on Lord Howe Island was white; blue Australasian swamphens occasionally arrived (stragglers from elsewhere have been found on the island) and bred with the white birds, accounting for the blue and partially-blue individuals in the old accounts. He also pointed out that Australasian swamphens are prone to white feathering.[3][18] In 1941, the biologist Ernst Mayr proposed that the white swamphen was a partially-albinistic population of Australasian swamphens. Mayr suggested that the blue swamphens remaining on Lord Howe Island were not stragglers, but had survived because they were less conspicuous than the white ones.[19] In 1967, the ornithologist James Greenway also considered the white swamphen a subspecies (with P. stanleyi a synonym) and considered the white individuals albinos. He suggested that the similarities between the wing feathers of the white swamphen and the takahē were due to parallel evolution in two isolated populations of reluctant fliers.[20]

The ornithologist Sidney Dillon Ripley found the white swamphen to be intermediate between the takahē and the purple swamphen in 1977, based on patterns of the leg-scutes, and reported that X-rays of bones also showed similarities with the takahē. He considered only the Vienna specimen to be a white swamphen, whereas he considered the Liverpool specimen to be an albino Australasian swamphen (listing P. stanleyi as a junior synonym of that bird) from New Zealand.[21] In 1991, the ornithologist Ian Hutton reported subfossil bones of the white swamphen. Hutton agreed that the birds described as having white-and-blue feathers were hybrids between the white swamphen and the Australasian swamphen, an idea also considered by the ornithologists Barry Taylor and Ber van Perlo in 2000.[22] In 2000, the writer Errol Fuller said that since swamphens are widespread colonists, it would be expected that populations would evolve similarly to the takahē when they found refuges without mammals (losing flight and becoming bulkier with stouter legs, for example); this was the case with the white swamphen. Fuller suggested that they could be called "white takahēs", which had been alluded to earlier; the white birds may have been a colour morph of the population, or the blue birds may have been Australasian swamphens which associated with the white birds.[23]

In 2015, the biologists Juan C. Garcia-R. and Steve A. Trewick analysed the DNA of the purple swamphens. They found that the white swamphen was most closely related to the Philippine swamphen (P. pulverulentus), and the black-backed swamphen (P. indicus) more closely related to both than to other species in its region. Garcia-R. and Trewick used DNA from the Vienna specimen, but were unable to obtain usable DNA from the Liverpool specimen. They suggested that the white swamphen may have descended from a few migrant Philippine swamphens during the late Pleistocene (about 500,000 years ago), dispersing over other islands. This indicates a complex history, since their lineages are not recorded on the islands between them; according to the biologists, such results (based on ancient DNA sources) should be treated with caution. Although many purple swamphen taxa had been considered subspecies of the species P. porphyrio, they considered this a paraphyletic (unnatural) grouping since they found different species to group among the subspecies. The cladogram below shows the phylogenetic position of the white swamphen according to the 2015 study:[2][24]

P. alleni (1)

P. martinica (2)

P. flavirostris (3)

Clade AP. p. porphyrio (1 sample)

P. p. indicus (7 samples)

P. p. madagascariensis (1 sample)

P. hochstetteri (#4)

P. mantelli (#5)

Clade BP. p. melanotus (35 samples)

P. p. bellus (5 samples)

P. p. pulverulentus (1 sample)

P. albus (#6)

P. p. indicus (1 sample)

P. p. seistanicus (1 sample)

P. p. poliocephalus (8 samples)

The ornithologists Hein van Grouw and Julian P. Hume concluded in 2016 that many of the old accounts had errors in the bird's provenance, that it was endemic to Lord Howe Island, and suggested when the specimens were collected (between March and May 1788) and under which circumstances they arrived in England. They concluded that the white swamphen was a valid species which changed colouration with age, after reconstructing the colouration of juvenile birds before turning white (which was distinct from other swamphens). Van Grouw and Hume found the white swamphen anatomically more similar to the Australasian swamphen than the Philippine swamphen, and suggested that studies with more-complete data sets than the earlier DNA might yield different results. Due to their anatomical similarities, geographic proximity and the recolonisation of Lord Howe and Norfolk Island by Australasian swamphens, they found it likely that the white swamphen was descended from Australasian swamphens.[2]

In 2021, Hume and colleagues reported the results of their palaeontological reconnaissance of Lord Howe Island, which included the discovery of subfossil white swamphen bones. A complete pelvis and representatives of most limb bones were found in the dunes of Blinky Beach (situated at the end of an airport runway), and the authors stated these would provide new insight into the morphology and behaviour of the species.[25]

The length of the white swamphen has been given as 36 cm (14 in) and 55 cm (22 in), making it similar to the Australasian swamphen in size. Its wings were proportionally the shortest of all swamphens. The wing of the Vienna specimen is 218 mm (9 in) mm long, the tail is 73.3 mm (3 in), the culmen with its frontal shield (the fleshy plate on the head) is 79 mm (3 in), the tarsus is 86 mm (3 in), and the middle toe is 77.7 mm (3 in) long. The wing of the Liverpool specimen is 235 mm (9 in) long, the tarsus is 88.4 mm (3 in) and the middle toe is 66.5 mm (3 in). Its tail and beak are damaged, and cannot be reliably measured. The white swamphen differed from most other swamphens (except the Australasian swamphen) in having a short middle toe; it is the same length as the tarsus, or longer, in other species. The white swamphen's tail was also the shortest. Both specimens have a claw (or spur) on their wings; it is longer and more discernible in the Vienna specimen, and sharp and buried in the feathers of the Liverpool specimen. This feature is variable among other kinds of swamphen.[2][7][23] The softness of the rectrices (tail feathers) and the lengths of the secondary and wing covert feathers relative to the primary feathers appear to have been intermediate between those of the purple swamphen and the takahē.[22]

Although the known skins are mostly white, contemporary illustrations depict some blue individuals; others had a mixture of white and blue feathers. Their legs were red or yellow, but the latter colour may be present only on dried specimens. The bill and frontal shield were red, and the iris was red or brown. According to notes written on an illustration by an unknown artist (in the collection of the artist Thomas Watling, inaccurately dated 1792), the chicks were black and became bluish-grey and then white as they matured. The Vienna specimen is pure white, but the Liverpool specimen has yellowish reflections on its neck and breast, blackish-blue feathers speckled on the head (concentrated near the upper surface of the shield) and neck, blue feathers on the breast, and purplish-blue feathers on the shoulders, back, scapular, and lesser covert feathers. Some of the rectrices (tail feathers) are purplish-brown, and some of the scapular feathers and those on the mid-back are sooty-brown at the base and sooty-blue further up. The central rectrices are sooty-brown and bluish. This colouration indicates that the Liverpool specimen was a younger bird than the Vienna specimen, and the latter had reached the final stage of maturity. Since the Liverpool specimen preserves some of its original colour, van Grouw, and Hume were able to reconstruct its natural colouration before becoming white. It differed from other swamphens in having blackish-blue lores, forehead, crown, nape, and hind neck; purple-blue mantle, back, and wings; a darker rump and upper-tail covert feathers; and dark greyish-blue underparts.[2][4][7][22][23]

Phillip gave a detailed description in 1789, possibly based on a live bird he received in Sydney:

This beautiful bird greatly resembles the purple Gallinule in shape and make, but is much superior in size, being as large as a dunghill fowl. The length from the end of the bill to that of the claws is two feet three inches; the bill is very stout, and the colour of it, the whole top of the head, and the irides red; the sides of the head around the eyes are reddish, very thinly sprinkled with white feathers; the whole of the plumage without exception is white. The legs the colour of the bill. This species is pretty common on Lord Howe’s Island, Norfolk Island, and other places, and is a very tame species. The other sex, supposed to be the male, is said to have some blue on the wings.[2]

The Vienna specimen is today a study skin with its legs outstretched (not a taxidermy mount), but van Grouw and Hume suggested that Stone's 1790 illustration showed its original mounted pose. It is in good condition; although the legs are faded to a pale orange-brown, they were probably reddish in the living bird. It has no yellowish or purple feathers, contradicting Rothschild's observation. Forbes suggested that the Liverpool specimen was "remade" and mounted after Stone's illustration, though its present pose is dissimilar. Keulemans's illustration of the mount shows the present pose, so Forbes was either incorrect or a new pose was based on Keulemans's image. The Liverpool specimen is in good condition, although it has lost some feathers from its head and neck. The bill is broken, and its rhamphotheca (the keratinous covering of the bill) is missing; the underlying bone was painted red to simulate an undamaged bill, which has caused some confusion. The legs have also been painted red, and there is no indication of their original colouration. The reason only white specimens are known today may be collecting bias; unusually-coloured specimens are more likely to be collected than normally-coloured ones.[2][4][14][22][23]

The white swamphen inhabited wooded lowland areas in wetlands. Nothing was recorded about its social and reproductive behaviour and its nest, eggs and call were never described. Presumably it did not migrate.[22] Blackburn's 1788 account is the only one that mentions the diet of this bird:

... On the shore we caught several sorts of birds ... and a white fowl – something like a Guinea hen, with a very strong thick & sharp pointed bill of a red colour – stout legs and claws – I believe they are carnivorous they hold their food between the thumb or hind claw & the bottom of the foot & lift it to the mouth without stopping so much as a parrot.[2]

Some contemporary accounts indicated that the bird was flightless. Rowley considered the Liverpool specimen (representing the separate species P. stanleyi) capable of flight, due to its longer wings; Rothschild believed that both were flightless, although he was inconsistent about whether their wings were the same length. Van Grouw and Hume found that both specimens showed evidence of an increased terrestrial lifestyle (including decreased wing length, more robust feet and short toes), and were in the process of becoming flightless. Although it may still have been capable of flight, it was behaviourally flightless, similar to other island birds, such as some parrots. Though the white swamphen was similar in size to the Australasian swamphen, it had proportionally shorter wings and therefore a higher wing load – perhaps the highest of all swamphens.[2][6][9] Upon the discovery of subfossil pelvic and limb bones in 2021, Hume and colleagues preliminarily stated that these bones were much more robust in the white swamphen than in the volant Australasian swamphen, a trait common in flightless rails.[25]

Van Grouw and Hume pointed out that a white colour aberration in birds is rarely caused by albinism (which is less common than formerly believed), but by leucism or progressive greying – a phenomenon van Grouw described in 2012 and 2013. These conditions produce white feathers due to the absence of cells which produce the pigment melanin. Leucism is inherited, and the white feathering is present in juveniles and does not change with age; progressive greying causes normally-coloured juveniles to lose pigment-producing cells with age, and they become white as they moult. Since contemporary accounts indicate that the white swamphen turned from black to bluish-grey and then white, Van Grouw and Hume concluded that it underwent inheritable progressive greying. Progressive greying is a common cause of white feathers in many types of birds (including rails), although such specimens have sometimes been inaccurately referred to as albinos. The condition does not affect carotenoid pigments (red and yellow), and the bill and legs of the white swamphens retained their colouration. The large number of white individuals on Lord Howe Island may be due to its small founding population, which would have facilitated the spread of inheritable progressive greying.[2][4][26]

Although the white swamphen was considered common during the late 18th century, it appears to have disappeared quickly; the period from the island's discovery to the last mention of living birds is only two years (1788–90). It had probably vanished by 1834, when Lord Howe Island was first settled, or during the following decade. Whalers and sealers had used the island for supplies, and may have hunted the bird to extinction. Habitat destruction probably did not play a role, and animal predators (such as rats and cats) arrived later.[2][7][22] Several contemporary accounts stress the ease with which the island's birds were hunted, and the large number which could be taken to provision ships.[3] In 1789, White described how the white swamphen could be caught:

They [sailors] also found on it, in great plenty, a kind of fowl, resembling much of the Guinea fowl in shape and size, but widely different in colour; they being in general all white, with a red fleshy substance rising, like a cock’s comb, from the head, and not unlike a piece of sealing-wax. These not being birds of flight, nor in the least wild, the sailors availing themselves of their gentleness and inability to take wing from their pursuits, easily struck them down with sticks.[2]

The fact that they could be killed with sticks may have been due to their poor flying ability, which would have made them vulnerable to human predation. With no natural enemies on the island, they were tame and curious.[2][3][23] The physician John Foulis conducted a mid-1840s ornithological survey on the island but did not mention the bird, so it was almost certainly extinct by that time.[7] In 1909, the writer Arthur Francis Basset Hull expressed hope that the bird still survived in unexplored mountains.[27]

Eight types of bird have become extinct due to human interference since Lord Howe Island was discovered, including the Lord Howe pigeon (Columba vitiensis godmanae), the Lord Howe parakeet (Cyanoramphus subflavescens), the Lord Howe gerygone (Gerygone insularis), the Lord Howe fantail (Rhipidura fuliginosa cervina), the Lord Howe thrush (Turdus poliocephalus vinitinctus), the robust white-eye (Zosterops strenuus) and the Lord Howe starling (Aplonis fusca hulliana). The extinction of so many native birds is similar to extinctions on several other islands, such as the Mascarenes.[3]

The white swamphen (Porphyrio albus), also known as the Lord Howe swamphen, Lord Howe gallinule or white gallinule, is an extinct species of rail which lived on Lord Howe Island, east of Australia. It was first encountered when the crews of British ships visited the island between 1788 and 1790, and all contemporary accounts and illustrations were produced during this time. Today, two skins exist: the holotype in the Natural History Museum of Vienna, and another in Liverpool's World Museum. Although historical confusion has existed about the provenance of the specimens and the classification and anatomy of the bird, it is now thought to have been a distinct species endemic to Lord Howe Island and most similar to the Australasian swamphen. Subfossil bones have also been discovered since.

The white swamphen was 36 to 55 cm (14 to 22 in) long. Both known skins have mainly-white plumage, although the Liverpool specimen also has dispersed blue feathers. This is unlike other swamphens, but contemporary accounts indicate birds with all-white, all-blue, and mixed blue-and-white plumage. The chicks were black, becoming blue and then white as they aged. Although this has been interpreted as due to albinism, it may have been progressive greying in which feathers lose their pigment with age. The bird's bill, frontal shield and legs were red, and it had a claw (or spur) on its wing. Little was recorded about the white swamphen's behaviour. It may not have been flightless, but was probably a poor flier. This and its docility made the bird easy prey for visiting humans, who killed it with sticks. Reportedly once common, the species may have been hunted to extinction before 1834, when Lord Howe Island was settled.

El calamón de la Lord Howe o gallineta blanca (Porphyrio albus) es una especie extinta de ave gruiforme perteneciente a la familia Rallidae. Sólo habitaba la Isla de Lord Howe.[1][2]

Era muy similar al calamón común, aunque con las patas y dedos más cortos y robustos. Su plumaje era blanco, a veces con algunas plumas azules, y probablemente no volaba, como otros parientes cercanos del calamón takahe.

Esta ave fue descrita por John White en su obra Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales (1790),[3] que además contenía una ilustración. No era abundante en la época en la que fue descrita y en poco tiempo balleneros y otros marinos los cazaron hasta la extinción.

Quedan solo dos pieles de esta ave, una el la colección del World Museum en Liverpool y la otra en el Naturhistorisches Museum Wien de Vienna. Además hay varias pinturas y varios huesos fósiles.

El calamón de la Lord Howe o gallineta blanca (Porphyrio albus) es una especie extinta de ave gruiforme perteneciente a la familia Rallidae. Sólo habitaba la Isla de Lord Howe.

Era muy similar al calamón común, aunque con las patas y dedos más cortos y robustos. Su plumaje era blanco, a veces con algunas plumas azules, y probablemente no volaba, como otros parientes cercanos del calamón takahe.

Esta ave fue descrita por John White en su obra Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales (1790), que además contenía una ilustración. No era abundante en la época en la que fue descrita y en poco tiempo balleneros y otros marinos los cazaron hasta la extinción.

Quedan solo dos pieles de esta ave, una el la colección del World Museum en Liverpool y la otra en el Naturhistorisches Museum Wien de Vienna. Además hay varias pinturas y varios huesos fósiles.

Porphyrio albus Porphyrio generoko animalia zen, jada iraungia. Hegaztien barruko Rallidae familian sailkatzen zen.

Porphyrio albus Porphyrio generoko animalia zen, jada iraungia. Hegaztien barruko Rallidae familian sailkatzen zen.

Valkosulttaanikana (Porphyrio albus) oli Australiaan kuuluvalla Lord Howen saarella elänyt rantakana. Valaanpyytäjät ja merimiehet metsästivät sen sukupuuttoon 1800-luvun alussa. Lajista on säilynyt kaksi museonäytettä, toinen Liverpoolissa ja toinen Wienissä. George Shaw kuvaili lajin holotyypin vuonna 1790.

Valkosulttaanikana (Porphyrio albus) oli Australiaan kuuluvalla Lord Howen saarella elänyt rantakana. Valaanpyytäjät ja merimiehet metsästivät sen sukupuuttoon 1800-luvun alussa. Lajista on säilynyt kaksi museonäytettä, toinen Liverpoolissa ja toinen Wienissä. George Shaw kuvaili lajin holotyypin vuonna 1790.

Porphyrio albus

La Talève de Lord Howe (Porphyrio albus) est une espèce disparue d'oiseau que l'on ne connaît que par deux peaux naturalisées, l'une à Vienne et l'autre à Liverpool, plusieurs illustrations et des os subfossiles. Elle était endémique à l'île Lord Howe. Bien que non rare, elle n'est découverte qu'en 1790. L'espèce, faisant l'objet d'une chasse intensive par les baleiniers et les marins, a probablement disparu au moment de la colonisation de l'île en 1834. L'oiseau est parfois considéré comme conspécifique avec la Talève sultane Porphyrio porphyrio, malgré des différences morphologiques.

Il pollo sultano di Lord Howe (Porphyrio albus Shaw, 1790) era un uccello della famiglia dei Rallidi originario dell'isola omonima[2].

Il pollo sultano di Lord Howe misurava circa 36 cm di lunghezza. Negli esemplari imbalsamati il piumaggio è prevalentemente bianco, ma le raffigurazioni fatte dai contemporanei mostrano che alcuni esemplari adulti presentavano delle zone di colore blu, in special modo sulle ali; le piume del collo e del petto avevano dei riflessi giallastri, mentre quelle del resto del corpo avevano riflessi blu; le zampe erano gialle, e becco, scudo frontale e iride erano di colore rosso. Secondo George Robert Gray i pulcini erano di colore completamente nero, ma con la crescita divenivano prima grigio-bluastri, poi completamente bianchi.

Il pollo sultano di Lord Howe è noto a partire da due esemplari impagliati, da vari resti subfossili e da un certo numero di illustrazioni e testimonianze scritte. Sebbene presentasse alcune variazioni nel colore, era un grosso uccello prevalentemente bianco, incapace di volare, mansueto e facilmente catturabile. Dovrebbe essere stato un uccello davvero spettacolare.

Le differenze nella colorazione erano dovute quasi certamente a una variazione individuale: alcuni esemplari erano blu, altri bianchi, e altri ancora bianchi e blu, forse in relazione al sesso e all'età. Sfortunatamente, queste minori discrepanze nei dettagli del piumaggio, unite alla provenienza incerta di alcuni esemplari, hanno portato a una certa confusione nella letteratura tassonomica, e alcuni taxa sono stati descritti a partire da testimonianze del tutto infondate.

Non vi è alcun dubbio che su Lord Howe sia vissuta una popolazione di Rallidi bianchi scomparsa nel corso della prima metà del XIX secolo. Il pollo sultano di Lord Howe era presente unicamente su quest'isola, e non vi è alcuna prova sostanziale che suggerisca la sua presenza altrove. Alcuni dissero che era presente anche sull'isola di Norfolk, ma dato che quei grandi naturalisti che furono i Forster non fecero menzione di polli sultani bianchi al momento della scoperta di Norfolk è estremamente improbabile che alcuni esemplari di questa specie fossero ivi presenti.

Gli studiosi non sanno inoltre se classificare o no il pollo sultano di Lord Howe come una specie a parte. Polli sultani Porphyrio porphyrio della sottospecie australasiatica melanotus sono ancora presenti su Lord Howe, e per questo motivo andrebbe presa in considerazione l'ipotesi sostenuta da Hindwood, secondo la quale esemplari originari dell'isola di colore bianco si sarebbero occasionalmente incrociati con uccelli blu giunti dall'Australia. Tuttavia, gli uccelli di Lord Howe erano incapaci di volare, o almeno così sembra; i due esemplari impagliati giunti fino a noi, infatti, hanno penne rettrici soffici, caratteristica, questa, associata all'incapacità di volare. Alcuni polli sultani ancora presenti su Lord Howe mostrano un piumaggio in parte bianco, e secondo Ernst Mayr è probabile che esemplari blu siano sopravvissuti alla scomparsa di quelli bianchi, grazie al fatto di essere meno facilmente individuabili.

Il pollo sultano di Lord Howe venne descritto per la prima volta nel 1789 da Arthur Phillip, Governatore del Nuovo Galles del Sud:

«Questo bellissimo uccello ricorda moltissimo il pollo sultano nella forma e nelle fattezze, ma ha dimensioni maggiori, essendo grande quanto un gallo domestico. Dalla punta del becco a quella delle unghie misura due piedi e tre pollici [circa 68 cm]. Il becco è molto tozzo, e di colore rosso, come l'intera sommità del capo e l'iride; la regione ai lati della testa, attorno agli occhi, è rossastra, inframmezzata da piccole piume bianche; l'intero piumaggio è, senza eccezione, bianco. Le zampe sono dello stesso colore del becco. La specie è molto comune sull'isola di Lord Howe, sull'isola di Norfolk, e in altri luoghi, ed è un animale molto mansueto. Gli esemplari dell'altro sesso, che si ritiene essere i maschi, si dice che abbiano delle piume blu sulle ali.»

White, l'anno successivo, descrisse la facilità con la quale si potevano catturare questi polli sultani:

«Essi [...] trovarono [...] in gran numero, delle specie di polli, che ricordavano molto la faraona per forma e dimensioni, ma di colore notevolmente differente; in generale si può affermare che erano tutti bianchi, con una sorta di struttura carnosa rossa sulla sommità del capo, simile alla cresta di un gallo, non dissimile da un pezzo di ceralacca. Non essendo uccelli volatori, almeno allo stato selvatico, i marinai approfittarono della loro mitezza e dell'incapacità di fuggire in volo dai loro inseguitori, abbattendoli con dei bastoni.[3]»

Seppur ritenuto comune alla fine del XVIII secolo, il pollo sultano di Lord Howe scomparve piuttosto rapidamente, forse prima del 1834, anno nel quale venne fondato il primo insediamento sull'isola. Prima di questa data, balenieri e marinai utilizzavano l'isola per fare rifornimento, ed è quindi molto probabile che avessero cacciato l'uccello fino all'estinzione. Ratti e gatti, invece, giunsero sull'isola solo successivamente. Lo studioso Foulis, che visse sull'isola tra il 1844 e il 1847, esaminò dettagliatamente l'avifauna dell'isola, ma non fece alcuna menzione di polli sultani bianchi, all'epoca già scomparsi.

Il pollo sultano di Lord Howe (Porphyrio albus Shaw, 1790) era un uccello della famiglia dei Rallidi originario dell'isola omonima.

De Lord-Howepurperkoet (Porphyrio albus) is een uitgestorven vogel uit de familie van de rallen, koeten en waterhoentjes (Rallidae).

Deze vogel was endemisch op Lord Howe-eiland in Australië.

Bronnen, noten en/of referentiesDe Lord-Howepurperkoet (Porphyrio albus) is een uitgestorven vogel uit de familie van de rallen, koeten en waterhoentjes (Rallidae).

Modrzyk mały (Porphyrio albus) – gatunek średniej wielkości ptaka z rodziny chruścieli. Występował endemicznie na Lord Howe. Między pierwszym (1788) i ostatnim opisaniem żywego ptaka (1790) minęły zaledwie dwa lata. Gatunek uznany za wymarły, wyginął wskutek odłowu przez wielorybników i żeglarzy.

Po raz pierwszy naukowo gatunek opisał angielski botanik i zoolog George Shaw w dzienniku Johna White’a Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales dotyczącego ekspedycji z lat 1877–1878. Opis zawierał wzmiankę o upierzeniu oraz porównanie z innymi wówczas znanymi gatunkami z rodzaju; autor napisał, że modrzyk mały wyglądem, z wyjątkiem swej białej barwy, podobny jest do zwyczajnego (Porphyrio porphyrio). Do opisu dodana była tablica barwna oznaczona numerem 27 (po lewej). Nowemu gatunkowi nadał nazwę naukową Fulica alba[4]. Obecnie (2017) Międzynarodowy Komitet Ornitologiczny umieszcza modrzyka małego w rodzaju Porphyrio[5]. Opis Shawa nie był pierwszy; wcześniej, w 1889, modrzyka małego opisał Arthur Phillip, ówczesny gubernator Nowej Południowej Walii[6].

Istnieją dwa okazy muzealne – jeden znajduje się w zbiorach w Wiedniu, drugi w Liverpoolu[7]. Okaz, na podstawie którego narysowano ptaka na tablicy z 1790, trafił do Wiednia po tym, jak ówczesne Royal Museum kupiło go w 1806 od Leverian Museum[8]; jest to holotyp. Do spreparowanego ptaka dołączono informację: ‘Lot 2782: White fulica, Fulica alba, New Holland. Pochodzenie okazu z Liverpoolu jest nieznane[2]. Kiedy w 1940 K.A. Hindwood opublikował swój artykuł na temat ptaków, Lord Howe wspomniał, że znany jest tylko jeden okaz[8]. Poza tym znane są ilustracje, 6 opisów znanych z pierwszej ręki (1788–początek 1790?) i szczątki subfosylne[7][6].

Nie jest jasne, czy modrzyk mały był odrębnym gatunkiem. Wiadomo, że ptaki te były nielotne (a przynajmniej tak się zachowywały); u dwóch okazów muzealnych zachowały się miękkie lotki i sterówki, charakterystyczne dla nielotów. U przedstawicieli Porphyrio na wyspie zdarza się leucyzm. Mayr przypuszczał, że osobniki białe zostały wytępione, gdyż bardziej rzucały się w oczy od ptaków biało-niebieskich lub niebieskich[6]. Niejasności w systematyce pojawiły się po raz pierwszy, gdy G. Dawson Rowley opisał okaz z Liverpoolu pod nazwą Porphyrio stanleyi na cześć Edwarda Smitha-Stanleya, dodając, że pochodzi z Lord Howe lub Nowej Zelandii. Wskazał liczne powierzchowne różnice między okazem z Wiednia a tym z Liverpoolu, twierdząc przy tym, że ptak z Wiednia zbliżony jest do modrzyka zwyczajnego, a ten z Liverpoolu do takahe (Porphyrio hochstetteri); na podstawie długości skrzydeł uznał również, że był to ptak lotny (co nie zgadza się z obserwacjami żywych modrzyków małych[4]). Część autorów zaczęła kwestionować odrębność gatunkową obydwu białych modrzyków. Temminck (1820), Gray (1844) i Mayr (1941) uznawali przedstawicieli Notornis alba (pod taką nazwą był wówczas znany gatunek) za albinotyczną odmianę modrzyka zwyczajnego, podobnie jak Rowley w 1875, mimo że w tej samej własnej publikacji opisał tego ptaka jako odrębny gatunek[2].

Długość ciała wynosiła około 36 cm. Upierzenie było zmienne[7]. Arthur Bowes Smythe, który jako pierwszy zilustrował przedstawicieli tego gatunku, narysował jednego ptaka całkowicie białego i dwa o mieszanym upierzeniu[2]. Część ptaków była całkowicie biała, inne miały upierzenie mieszane lub całkowicie niebieskie. Możliwe, że ptaki z obecną barwą niebieską były hybrydami z modrzykiem (na Lord Howe występują przedstawiciele podgatunku P. p. melanotus). Dziób i rogowa tarcza były czerwone, nogi czerwone lub żółte. Szczegół ten różni się zarówno w opisach, jak i na ilustracjach[7]. W oryginalnym opisie Shaw zaznaczył, że u wyschniętego okazu nogi są żółte, tablica barwna również przedstawia ptaka z żółtymi nogami[4], jednak okaz z Wiednia, czyli holotyp, ma nogi czerwone. U spreparowanego modrzyka z Liverpoolu nogi i dziób zostały pomalowane na czerwono, nie wiadomo, jakiej barwy były najpierw[7]. Thomas Gilbert nogi opisał jako żółte[2]. Phillip (1789) przedstawił szczegółowy opis upierzenia tego ptaka, najprawdopodobniej wykonany na podstawie obserwacji żywego ptaka, którego otrzymał w Sydney. Miał on mieć czerwoną tęczówkę i nogi[2]. U okazu ze zbiorów w Wiedniu na zgięciu skrzydła występuje szpon[2].

Nie jest jasne, które opisy historyczne dotyczą modrzyków małych, które hybryd, a które modrzyków zwyczajnych. Wiadomo, że przez ostatnie 130 lat (stan z 2016) modrzyki zwyczajne pojawiały się na wyspie tylko jako ptaki zabłąkane, a zaczęły na niej gniazdować dopiero w 1987. Dane co do wielkości są sprzeczne. Okaz z Liverpoolu ma krótsze i mocniej zbudowane nogi niż modrzyki zwyczajne, mniej masywny dziób, miększe lotki i sterówki. Fuller (1987) twierdził, że modrzyki małe miały być większe od modrzyków zwyczajnych i mieć mocniej zbudowany dziób[7]. David Blackburn opisał dziób jako gruby i ostro zakończony[2].

Wymiary dla osobników odpowiednio z Liverpoolu i Wiednia: długość skrzydła 228 mm, długość ogona 88 i 75 mm, długość górnej krawędzi dzioba 63 (do nasady tarczy) i 79 (wraz z tarczą) mm, długość skoku 77 i 92 mm[7]. Należy jednak zaznaczyć, że u okazu z Liverpoolu całkowicie brakuje pochwy rogowej dzioba (ramfoteki), a sam dziób został przemalowany; fakt do 2016 pozostał niezauważony. Tłumaczy to znaczącą różnicę w długości dzioba obydwu okazów i jedynie długość dzioba dla okazu z Wiednia można uznać za wiarygodną[2].

Modrzyk mały występował wyłącznie na Lord Howe[7].

Pojawiały się również doniesienia o tym, że występowały na Norfolk i Piramidzie Balla, są one jednak nieprawdziwe[7]. Nieporozumienia wśród naukowców rozpoczął Phillip, który napisał, że ptaki te zamieszkują Lord Howe i inne miejsca, później zaś Latham napisał, że zasiedlają one tylko Norfolk. Miał się odnieść do informacji dostarczonych przez Phillipa i White’a, jednak wskazali oni tylko Lord Howe. Informacje przez nich dostarczone również nie są pewne, bowiem obydwaj nie odwiedzili osobiście Lord Howe. August von Pelzeln powtórzył informacje podane przez Lathama. W Leverian Museum do wiedeńskiego okazu dodano adnotację, wedle której ptak miał pochodzić z Australii (New Holland). Między Sydney a Norfolk często pływały statki, nierzadko zatrzymując się na Lord Howe, co mogło doprowadzić do pomyłek. Ostatecznie kwestię występowania modrzyków małych na Norfolk rozstrzygnął Iredale (1910), który wykazał, że w czasach bliskich wymienionym autorom modrzyk mały nie występował na żadnej innej wyspie niż Lord Howe[2].

Modrzyki małe były nielotami[4]. Zamieszkiwały zadrzewione nizinne obszary[7]. David Blackburn, który odwiedził Lord Howe w marcu i maju 1788, jako jedyny wspomniał o diecie ptaka. Były ponoć mięsożerne i zdolne do podawania sobie pokarmu do dzioba łapami, tak jak czyniły to papugi. W kolekcji Thomas Watlinga znajdowała się ilustracja nieznanego autora (obecnie w Muzeum Historii Naturalnej w Londynie) opatrzona dodatkowym opisem. Według niego pisklęta miały być całkowicie czarne, następnie stawały się niebieskoszare, później całkiem bielały[2].

IUCN uznaje modrzyka małego za gatunek wymarły (EX, Extinct). BirdLife International jako przyczynę wymarcia wskazuje odłów przez wielorybników i żeglarzy[9]. Między pierwszym a ostatnim opisaniem żyjącego ptaka minęły zaledwie dwa lata (1788–1790). Na Lord Howe ludzie na stałe zamieszkali w 1834, ale już wcześniej wyspę odwiedzali wielorybnicy i żeglarze. Arthur Bowes Smythe, chirurg z okrętu Lady Penrhyn, opisał uległość charakterystyczną dla ptaków wyspowych (island tameness) w odniesieniu do modrzyków małych i wodników brunatnych (Hypotaenidia sylvestris). Miały być one pozbawione lęku przed człowiekiem, dawały się łapać w ręce lub zabijać kijami[2]. Wspomniał o tym również White[4]. Foulis, który przebywał na wyspie między 1844 a 1847, jako pierwszy zbadał awifaunę wyspy; nie odnotował już jednak modrzyka małego[2].

Lista wymarłych gatunków za: Maas, P.H.J: Globally Extinct Birds. The Sixth Extinction, 2 stycznia 2017. [dostęp 24 maja 2017].

Modrzyk mały (Porphyrio albus) – gatunek średniej wielkości ptaka z rodziny chruścieli. Występował endemicznie na Lord Howe. Między pierwszym (1788) i ostatnim opisaniem żywego ptaka (1790) minęły zaledwie dwa lata. Gatunek uznany za wymarły, wyginął wskutek odłowu przez wielorybników i żeglarzy.

Porphyrio albus é uma espécie extinta de ave da família Rallidae, endêmica da ilha de Lord Howe, localizada no Mar da Tasmânia, a cerca de 600 km da costa da Austrália.[1]

A ilha de Lord Howe é uma ilha pequena e remota a cerca de 600 quilômetros a leste da Austrália. Os navios chegaram pela primeira vez à ilha em 1788, incluindo dois que abasteciam a colônia penal na ilha Norfolk e três navios de transporte da First Fleet Britânica. Quando o HMS Supply passou pela ilha, o comandante do navio a batizou em homenagem ao Primeiro Lorde do Almirantado Richard Howe. Tripulações dos navios visitantes capturaram aves nativas (incluindo caimões brancos), e todas as descrições e representações contemporâneas da espécie foram feitas entre 1788 e 1790. A ave foi mencionada pela primeira vez pelo mestre da HMS Supply, David Blackburn, em uma carta de 1788 para um amigo. Outros relatos e ilustrações foram produzidos por Arthur Bowes Smyth, o oficial naval da frota e cirurgião que desenhou a primeira ilustração conhecida da espécie; Arthur Phillip, governador de Nova Gales do Sul; e George Raper, guarda-marinha do HMS Sirius. Também existem relatos de segunda mão e são conhecidas pelo menos dez ilustrações contemporâneas. Os relatos indicam que a população variava e a plumagem de cada ave era branca, azul ou misturada com azul e branco.

Embora a espécie fosse considerada comum durante o final do século XVIII, parece ter desaparecido rapidamente; o período desde a descoberta da ilha até a última menção de aves vivas é de apenas dois anos (de 1788 a 1790). Provavelmente desapareceu em 1834, quando a ilha de Lord Howe foi colonizada pela primeira vez, ou durante a década seguinte. Baleeiros e caçadores de focas usaram a ilha como fonte de suprimentos e podem ter caçado a ave até a extinção. A destruição do habitat provavelmente não desempenhou um papel relevante, e animais predadores (como ratos e gatos) chegaram mais tarde. Vários relatos contemporâneos enfatizam a facilidade com que as aves da ilha eram caçadas e a grande quantidade dela que poderia ser levada para abastecer os navios. Em 1789, White descreveu como o Porphyrio albus poderia ser capturado:

Porphyrio albus é uma espécie extinta de ave da família Rallidae, endêmica da ilha de Lord Howe, localizada no Mar da Tasmânia, a cerca de 600 km da costa da Austrália.

Vit purpurhöna[2] (Porphyrio albus) är en utdöd fågel i familjen rallar inom ordningen tran- och rallfåglar.[3] Den förekom tidigare på Lord Howeön. Fågeln rapporterades senast 1834.[3] IUCN kategoriserar arten som utdöd.[1]

Vit purpurhöna (Porphyrio albus) är en utdöd fågel i familjen rallar inom ordningen tran- och rallfåglar. Den förekom tidigare på Lord Howeön. Fågeln rapporterades senast 1834. IUCN kategoriserar arten som utdöd.

Уперше цього птаха у своїй книжці Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales[2] (1790) описав Джон Вайт. Книжка містила, зокрема, ілюстрацію. Вид не був рідкісним на той час, але повністю вимер через полювання на нього китобоями та моряками.

На сьогодні збереглося два екземпляри цього виду: один — у Світовому музеї в Ліверпулі, другий — у Музеї природознавства у Відні. Існує також кілька зображень та субфосильних кісток.

Уперше цього птаха у своїй книжці Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales (1790) описав Джон Вайт. Книжка містила, зокрема, ілюстрацію. Вид не був рідкісним на той час, але повністю вимер через полювання на нього китобоями та моряками.

На сьогодні збереглося два екземпляри цього виду: один — у Світовому музеї в Ліверпулі, другий — у Музеї природознавства у Відні. Існує також кілька зображень та субфосильних кісток.

Porphyrio albus là một loài chim trong họ Rallidae.[1]

Белая султанка[1][2] (лат. Porphyrio albus) — вид вымерших птиц семейства пастушковых.

Крупная птица, размерами и телосложением напоминающая султанку. Ноги более короткие и сильные. Оперение белое, иногда с несколькими синими перьями. Полностью синие птицы, описанные как Porphyrio albus, вероятно, принадлежали к виду Porphyrio porphyrio, который тоже обитает на этом острове. Вероятнее всего, птица не летала.

Обитала на острове Лорд-Хау в Тасмановом море[3].

Впервые была описана в 1790 году английским врачом Джоном Уайтом в его журнале «Путешествие в Новый Южный Уэльс». В то время птица не считалась редкостью. Вымерла в первой половине XIX века. Причина вымирания — бесконтрольная охота. Почти не способные летать птицы становились лёгкой добычей высаживавшихся на остров китобоев и моряков.

Сохранилось два экземпляра в музеях Ливерпуля и Вены, а также несколько рисунков.

Белая султанка (лат. Porphyrio albus) — вид вымерших птиц семейства пастушковых.

新不列顛紫水雞(Porphyrio albus),又名羅德豪紫水雞或留尼汪白渡渡鳥,是澳洲豪勳爵島特有一種秧雞。牠們像紫水雞,但身體較為短及雙腳較钝。牠們的身體呈白色,有時會有一些藍色的雜色。牠們可能不能飛。另外有身體是完全藍色的形態,但不肯定是否屬於此物種或是紫水雞。現存的兩個標本的羽毛都是白色的。

新不列顛紫水雞首先是於1790年描述。當時牠們已經很稀少,但卻被獵殺至滅絕。

現時有兩個新不列顛紫水雞的標本,分別存放在利物浦及維也納。另外亦有一些圖畫及亞化石骨頭。

新不列顛紫水雞(Porphyrio albus),又名羅德豪紫水雞或留尼汪白渡渡鳥,是澳洲豪勳爵島特有一種秧雞。牠們像紫水雞,但身體較為短及雙腳較钝。牠們的身體呈白色,有時會有一些藍色的雜色。牠們可能不能飛。另外有身體是完全藍色的形態,但不肯定是否屬於此物種或是紫水雞。現存的兩個標本的羽毛都是白色的。

新不列顛紫水雞首先是於1790年描述。當時牠們已經很稀少,但卻被獵殺至滅絕。

保全状況評価 EXTINCT

保全状況評価 EXTINCT 分類 界 : 動物界 Animalia 門 : 脊索動物門 Chordata 亜門 : 脊椎動物亜門 Vertebrata 綱 : 鳥綱 Aves 目 : ツル目 Gruiformes 科 : クイナ科 Rallidae 属 : セイケイ属 Porphyrio 種 : ロードハウセイケイ

分類 界 : 動物界 Animalia 門 : 脊索動物門 Chordata 亜門 : 脊椎動物亜門 Vertebrata 綱 : 鳥綱 Aves 目 : ツル目 Gruiformes 科 : クイナ科 Rallidae 属 : セイケイ属 Porphyrio 種 : ロードハウセイケイロードハウセイケイ(学名:Porphyrio albus)は、ツル目クイナ科に属するセイケイの一種の鳥。

オーストラリアの東方約600kmに位置する孤島ロード・ハウ島に生息していたが、すでに絶滅した。体色は白で、クチバシは朱色。

18世紀末にロード・ハウ島で採集された2体の標本、絵、旅行者の記述のみによって知られる。ロード・ハウ島は1788年にイギリス人によって発見されたが、1834年にこの島に人が住むようになったときにはすでに見られなくなっていた。原因については、立ち寄った船乗りの食用として乱獲されたためと考えられている。絶滅年代を1800年前後とする説もある。

ロードハウセイケイ(学名:Porphyrio albus)は、ツル目クイナ科に属するセイケイの一種の鳥。

オーストラリアの東方約600kmに位置する孤島ロード・ハウ島に生息していたが、すでに絶滅した。体色は白で、クチバシは朱色。