pt-BR

nomes no trilho de navegação

Die Nylkrokodil (Crocodylus niloticus) is die grootste van die vier krokodilspesies wat in Afrika voorkom. Die krokodille het lang sterte en kragtige kake. Hulle agterpote is geweb om hulle te help swem. Hulle word tot 6 meter lank en kan tot 1000 kg weeg.[1] Die mannetjies is gewoonlik groter as die wyfies.

Nylkrokodille kom wydverspreid oor Afrika suid van die Sahara en in Madagaskar voor. Hulle het vantevore selfs in die Middellandse See, Israel en Jordanië voorgekom. Hierdie krokodille leef in verskillende habitats, insluitend mere, riviere en riviermondings.

Onvolwasse nylkrokodille vreet insekte en klein vissies. Die volwasse nylkrokodille vang groter diere om te vreet, soos sebras, wildsbokke, wildebeeste en buffels,[1] en vreet ook mense.

Dié krokodille paar in die water, waarna die wyfie 'n gat in die grond grawe waarin sy haar eiers lê. Hulle kan tot 60 eiers lê wat ongeveer 90 dae neem om uit te broei.[1] Die wyfie pas die nes gedurende hierdie tyd op. Jong krokodille kan vanaf 12-jarige ouderdom voortplant.[1]

Die Nylkrokodil (Crocodylus niloticus) is die grootste van die vier krokodilspesies wat in Afrika voorkom. Die krokodille het lang sterte en kragtige kake. Hulle agterpote is geweb om hulle te help swem. Hulle word tot 6 meter lank en kan tot 1000 kg weeg. Die mannetjies is gewoonlik groter as die wyfies.

Nylkrokodille kom wydverspreid oor Afrika suid van die Sahara en in Madagaskar voor. Hulle het vantevore selfs in die Middellandse See, Israel en Jordanië voorgekom. Hierdie krokodille leef in verskillende habitats, insluitend mere, riviere en riviermondings.

Onvolwasse nylkrokodille vreet insekte en klein vissies. Die volwasse nylkrokodille vang groter diere om te vreet, soos sebras, wildsbokke, wildebeeste en buffels, en vreet ook mense.

Dié krokodille paar in die water, waarna die wyfie 'n gat in die grond grawe waarin sy haar eiers lê. Hulle kan tot 60 eiers lê wat ongeveer 90 dae neem om uit te broei. Die wyfie pas die nes gedurende hierdie tyd op. Jong krokodille kan vanaf 12-jarige ouderdom voortplant.

Krokodýl nilský (Crocodylus niloticus) je nejhojnější a nejznámější druh krokodýla, patří rovněž k druhům, dorůstajícím největší velikosti. Vyskytuje se na většině území Afriky a v Izraeli. Navzdory lovu i úbytku stanovišť zatím nepatří mezi ohrožené druhy. Pro svou kůži i maso se chová na krokodýlích farmách po celém světě.

Vědecký název Crocodylus niloticus dal zvířeti roku 1768 rakouský přírodovědec Josph Nicolaus Laurenti, toto pojmenování však má antické kořeny. Slovo krokodýl pochází z řečtiny a poprvé je doloženo v díle Hérodota. Doslova znamená "dlážděný červ", což má odkazovat na tvrdé hřbetní destičky. Už starověcí autoři jako Diodóros Sicilský používali označení crocodylus niloticus, tedy doslova nilský dlážděný červ. Podle pozdně antických Etymologií Isidora ze Sevilly je slovo crocodylus odvozeno od květiny krokusu, protože krokodýli mají stejně žluté břicho jako šafrán, získávaný z krokusu. Tento výklad však není obecně přijímán.

Afričtí domorodci nazývají krokodýla nilského mnoha názvy. V Súdánu je krokodýl znám pod arabským názvem timsah, v západní Africe ho Hausové nazývají kada a Jorubové öni, ve východní Africe je znám pod svahilským názvem mamba, v Burundi je nazýván ingona, v Kongu ho mluvčí jazyka lingala nazývají nkóli, v jižní Africe ho Zuluové, Khosové, Tswanové či Vendové nazývají ngwena či kwena a Malgaši na Madagaskaru mu dali jméno voay.

Krokodýl nilský patří mezi největší druhy krokodýlů. Za vhodných podmínek může dorůst délky až okolo 6,5 m a hmotnosti 1100 kg, ale jedinci delší než cca 5 m jsou extrémně vzácní. Největší žijící krokodýl nilský se jmenuje Gustav a žije ve volné přírodě na řece Ruzizi v Burundi, při posledním pozorování roku 2008 měřil více než 610 cm a vážil asi 1000 kg.[zdroj?] Pohlavní dimorfismus je spíše nevýrazný, spočívá především ve velikosti; samci zpravidla dorůstají větších rozměrů než samice. Samci měří v průměru okolo 4 metrů, samice mírně přes 3 metry.

Jako všechny druhy krokodýlů má krokodýl nilský kůži pokrytou hranatými šupinami, které se vzájemně nepřekrývají. Ty jsou na hřbetě a ocase podloženy kostními štítky (osteodermy), zatímco na hlavě je kůže pevně přirostlá k lebce. V zadní části hřbetu a na ocase tvoří šupiny dvojitý hřeben, který asi ve dvou třetinách délky ocasu splývá do jediného, vyššího hřebenu. Vzhledem k tomu, že pod kůží na břiše nemá vyvinuty osteodermy (tvrdé kostěné štíty), jeho kůže se hodí pro komerční využití. Z toho důvodu je hojně loven a rovněž chován na farmách.

Zbarvení je olivově zelené, šedé až modrozelené, často s tmavými skvrnami a proužky, především na bocích. Břicho je žlutavé, světle zelené nebo špinavě bílé. Končetiny jsou silné, přední mají pět prstů, zadní mají prsty jen čtyři, spojené malou plovací blánou. Hlava krokodýla nilského je dlouhá a poměrně široká, na konci poněkud zúžená. Počet zubů je 64 až 68, čtvrtý spodní zub vyčnívá, jako u všech krokodýlovitých, ze zavřené tlamy. Zuby jsou kuželovité a neumožňují žvýkání. Zuby jsou zasazeny do jamek v čelistech (thekodontní typ chrupu) a během života se poměrně často vyměňují. Velcí, staří krokodýlové během života prodělali výměnu zubů nejméně čtyřicetkrát.

Krokodýl nilský žije obvykle samotářsky, i když na vhodných stanovištích dosahuje jeho populace značné hustoty. Samci jsou teritoriální a zejména v období páření neváhají napadat jiné krokodýly. Přes den se krokodýli nejčastěji sluní na břehu, odkud při vyrušení prchají do vody. Nejaktivnější jsou za soumraku, kdy také zpravidla loví. Přestože krokodýl na souši působí neohrabaně, při útěku nebo útoku na kořist dokáže vyvinout značnou rychlost. Ve vodě krokodýl nilský plave horizontálním vlněním dlouhého ocasu. Při útoku na kořist se krokodýl dokáže prudce vymrštit z vody do výšky 1-2 m. K odpočinku si krokodýli nilští vyhrabávají pod břehem prostorné nory, které mohou měřit až 10 m. Zde přečkávají i dlouhotrvající sucha nebo období nedostatku potravy, často i více zvířat pohromadě.

Ke v vzájemné komunikaci využívají krokodýlové širokou škálu optických, akustických a pachových signálů. Podčelistní pachové žlázy se uplatňují zejména v době páření. Na rozdíl od většiny plazů mají krokodýlové nilští poměrně široký hlasový repertoár. Samci v období páření hlasitě řvou, mláďata při líhnutí komunikují s rodiči zvláštním kvákáním, které se podobá kvákání kachny. Při ohrožení mláďata přivolávají matku kvákáním a pištěním.

Mezi krokodýlem nilským a některými ptáky, zejména kulíkem nilským (Pluvianus aegyptius) a čejkou ostruhatou (Vanellus spinosus) existují komenzální vztahy, podobně jako mezi velkými africkými savců a klubáky či volavkou rusohlavou. Ptáci se pohybují mezi krokodýly, slunícími se na břehu, odstraňují jim parazity i zbytky potravy, uvázlé mezi zuby. Mohou krokodýly rovněž varovat před nebezpečím.

Krokodýl nilský se ve starověku vyskytoval v celé Africe, na Madagaskaru a na Blízkém východě, např. v řece Jordán. V Egyptě a v asijské části svého areálu však byl v průběhu 19. století vyhuben. V současné době se vyskytuje v Africe jižně od Sahary, od Mali, Senegalu a Súdánu až po Kapsko. Na Madagaskaru je poměrně vzácný, v Izraeli byl reintrodukován koncem 20. století. Je vázán na vodní plochy, především řeky a jezera, k životu mu ale stačí i rozsáhlejší bažina. Izolovaná populace žije dokonce i saharských oázách pohoří Tassíli. Zdejší krokodýli dosahují délky jen do 2 m a jejich populace je ohrožena vyhubením. Na Madagaskaru žije i jeskynních řekách (např. rezervace Ankarana) a nevyhýbá se ani brakické vodě.

Krokodýl nilský je výlučně masožravý. Skladba potravy se mění v závislosti na věku a velikosti krokodýla. Mláďata do délky 1 m se zdržují při břehu, kde loví především hmyz (přes 60% potravy), dále žáby, korýše, pavouky či malé rybky. Starší zvířata v délce 1-3 m se živí téměř výhradně rybami, jen malá část potravy připadá na korýše, měkkýše, žáby, vodní hmyz a drobné savce či plazy. Dospělá zvířata dorůstající 4-6 m loví velké ryby (zvláště sumce, okouna nilského, bahníky), želvy a jiné plazy, vodní ptáky, ale také savce, až do velikosti žirafy, buvola, mladého hrocha či slůněte. Častější kořistí jsou však pakoně, prasata bradavičnatá, vodušky, sitatungy či jiné antilopy.

Menší kořist krokodýl usmrtí stiskem čelistí, větší savce obvykle uchopí za přední končetinu nebo za čenich, stáhne pod hladinu a utopí. Protože krokodýli nemohou žvýkat, trhají kořist nejčastěji tak, že se pevně zakousnou a pak otáčením kolem své osy vytrhnou kus masa. Větší úlovek často ukládají v norách pod podemletým břehem , kde ho konzumují několik dní. Konzumují také mršiny, naproti tomu kanibalismus je pouze výjimečný. Krokodýl má v čelistech mimořádný stisk, dosahující síly až 13 kN.

V období páření krokodýli vydávají bučivé zvuky, zesiluje také jejich pach. v obou případech se jedná o prostředky komunikace mezi pohlavími. Po páření, které probíhá ve vodě, si samice na břehu vyhrabe jámu, hlubokou asi 50-80 cm. Do ní naklade 20 až 80 vajec, která zahrabe. Počet vajec závisí na velikosti a kondici samice. Vejce mají ovální tvar a měří asi 8 x 6 cm. Po nakladení jámu s vejci samice zahrabává. Pohlaví mláďat není dáno geneticky, ale závisí na teplotě, při níž se vejce inkubují (podobně jako u mnoha druhů želv a některých ještěrů). Při teplotách nižších než 29 stupňů Celsia se líhnou samičky, při teplotě kolem 30 stupňů je poměr pohlaví vyrovnaný, při vyšších teplotách převažují samci. Inkubace zpravidla trvá 85-95 dnů. Po celou dobu inkubace samice snůšku obvykle hlídá před predátory, přesto mnoho vajec padne za oběť dravým ptákům, čápům marabu, varanům nilským, hyenám, promykám či paviánům. Po vylíhnutí mláďata přivolávají matku kvákavými zvuky. Samice mláďatům pomáhá vyhrabat se z jámy a často je v tlamě odnáší do vody, kde je nějakou dobu (1-5 měsíců) hlídá. U příbuzných druhů bylo pozorováno, jak v období sucha samice převádí mláďata z vysychajícího jezírka do řeky.

Staří Egypťané uctívali boha řeky Nilu jménem Sobek, jenž byl zobrazován s hlavou krokodýla. V jeho chrámech byli chováni krokodýli, které věřící krmili. Uhynulé krokodýly Egypťané také balzamovali. Krokodýlí kult ale nebyl rozšířen v celém Egyptě a místy, zvláště v Horním Egyptě, byli krokodýli naopak loveni a pojídání. V římské době byl krokodýl symbolem Egypta a jeho obraz se objevoval i na mincích. Římané krokodýly zneužívali při hrách v cirku. Zde byli krokodýli zabíjeni, štváni proti jiným zvířatům nebo jim byli předhazováni odsouzenci.

Ve středověkých bestiářích či Mandevillově cestopise se tradovalo mnoho představ o krokodýlech, kteří zabíjejí lidi a před jejich pozřením roní pokrytecké slzy, podle jiných legend žere krokodýl pouze muslimy a pohany, zatímco křesťanů si nevšímá.

V Africe a na Madagaskaru mnohé kmeny pokládají krokodýly za své předky, nebo věří, že se zemřelí lidé proměňují v krokodýly. Krokodýlí kult je dosud rozšířen např. mezi Šilúky v Jižním Súdánu, u etnika Dan v Pobřeží slonoviny nebo u Mossiú v Burkině Faso. Někde, zvláště na Madagaskaru nebo v oblasti Velkých jezer (království Buganda a Buňoro) byli krokodýlové používáni k ordálům, při nichž měl obviněný proplavat mezi krokodýly. Po celé Africe jsou rozšířeny představy o čarodějích, kteří se mohou teriantropicky proměňovat v krokodýly nebo je alespoň ovládat. V oblasti Pobřeží slonoviny, Libérie a delty Nigeru existovaly tajné společnosti krokodýlích lidí, kteří nosili krokodýlí masky a provozovali obřady, včetně rituálních vražd a kanibalismu (obdoba známějších společností Levhartích lidí).

K lovu krokodýlů slouží v Africe především udice s velkým dvojhákem, případně harpuna, loví se rovněž odstřelem, především v noci, za pomoci reflektoru, kterým lovci krokodýly oslní. Dost rozšířené jsou i krokodýlí farmy, které se objevují v poslední době i v Evropě. V České republice jsou zastoupeny kontroverzním podnikem ve Velkém Karlově na Znojemsku. Využívá se kůže, především z břišních partií a také maso. Afričtí domorodci využívají pachové žlázy, tuk i orgány krokodýlů k magickým, medicínským nebo kosmetickým účelům. Vzhledem k velkým rozměrům a relativně rychlému růstu se krokodýl nilský nehodí pro chov v bytových podmínkách. Rovněž v ZOO se s ním setkáváme poměrně zřídka, v České republice je chová jen krokodýlí ZOO Protivín.

Krokodýl nilský (Crocodylus niloticus) je nejhojnější a nejznámější druh krokodýla, patří rovněž k druhům, dorůstajícím největší velikosti. Vyskytuje se na většině území Afriky a v Izraeli. Navzdory lovu i úbytku stanovišť zatím nepatří mezi ohrožené druhy. Pro svou kůži i maso se chová na krokodýlích farmách po celém světě.

Nilkrokodille (Crocodylus niloticus) er en af 4 arter krokodiller i Afrika, og den næststørste af arterne. Nilkrokodillen findes i det meste af Afrika syd for Sahara, og på øen Madagaskar. Nilkrokodillen kan blive op til 6.50 m lang og veje 1100 kg, De største eksemplarer er blevet målt i Tanzania og var 6,45 m lange og vejede 1090 kg.[2]

Nilkrokodillen er et af de dyr på jorden med den kraftigste bidestyrke. Den bider med 3500 kg/cm².[3] Til sammenligning er menneskets bidestyrke på 105 kg/cm².

Nilkrokodille (Crocodylus niloticus) er en af 4 arter krokodiller i Afrika, og den næststørste af arterne. Nilkrokodillen findes i det meste af Afrika syd for Sahara, og på øen Madagaskar. Nilkrokodillen kan blive op til 6.50 m lang og veje 1100 kg, De største eksemplarer er blevet målt i Tanzania og var 6,45 m lange og vejede 1090 kg.

Nilkrokodillen er et af de dyr på jorden med den kraftigste bidestyrke. Den bider med 3500 kg/cm². Til sammenligning er menneskets bidestyrke på 105 kg/cm².

Das Nilkrokodil (Crocodylus niloticus) ist eine Art der Krokodile (Crocodylia) aus der Familie der Echten Krokodile (Crocodylidae). Die normalerweise 3–4 m lang werdende Art bewohnt Gewässer in ganz Afrika und ernährt sich größtenteils von Fischen. Gelegentlich können Nilkrokodile jedoch auch große Säugetiere (z. B. Zebras) unter Wasser zerren und ertränken. Das Nilkrokodil betreibt intensive Brutpflege, die Mutter bewacht ihr Nest und beschützt die Jungtiere in den ersten Lebensmonaten. Die Art nahm eine wichtige Rolle in der ägyptischen Mythologie ein und war einst wegen starker Bejagung gefährdet. Nachdem die Jagd in den 1980ern verboten wurde, haben sich die Bestände weitgehend erholt.

Das Nilkrokodil ist das größte Krokodil Afrikas und erreicht normalerweise Längen von 3 bis 4 m.[1] Große Weibchen werden über 2,8 m lang, während große Männchen über 3,2 m lang werden können.[2] Sehr selten werden über 6 m Länge erreicht, als Maximum gelten 6,5 m. Die Schnauze ist 2-mal so lang wie an der Basis breit. Der Ruderschwanz ist kräftig und seitlich abgeflacht. Erwachsene Nilkrokodile sind oberseits dunkel-olivfarben, der Bauch ist einheitlich porzellanfarben. Die Jungtiere sind hell olivfarben und dunkel gefleckt und gebändert. Die Färbung der Krokodile wird stark von den im Wasser gelösten Stoffen beeinflusst.

Das Nilkrokodil bewohnt nahezu ganz Afrika inklusive Madagaskar, fehlt aber im äußersten Südwesten Afrikas, in der Sahara (bis auf ein isoliertes Vorkommen im Guelta d’Archei) und im Osten Madagaskars. Früher bewohnte es auch den Nil auf der gesamten Länge, findet sich heute aber nur noch im Oberlauf bis Assuan. Die Art bewohnt zahlreiche Lebensräume, so etwa Flüsse, Teiche, Seen, Sümpfe und Mangroven.

Es werden aktuell sieben geographische Unterarten unterschieden. Genetische Untersuchungen führen zu Spekulationen, dass möglicherweise einige davon auch als eigene Arten anzusehen sind:[3]

Die Unterarten werden anhand ihrer Pholidose unterschieden.

Nilkrokodile wurden in den letzten Jahren auch vereinzelt in den Everglades in Florida gesichtet. Man vermutet, dass diese durch den Menschen illegal eingeschleppt worden sind und sich dort als Neozoon vermehrt haben.[5]

In historischer Zeit kam das Nilkrokodil auch in Algerien, Israel und den Komoren vor.[6]

Tagsüber sonnen sich Nilkrokodile meist am Ufer, nachts gehen die Krokodile ins Wasser. An den großen afrikanischen Flüssen, die nicht saisonal austrocknen, sind Nilkrokodile das ganze Jahr über aktiv. In saisonal austrocknenden, kleineren Gewässern lebende Krokodile bleiben wesentlich kleiner (2,4–2,7 m) als Krokodile in permanenten Gewässern. Sie verbringen die Trockenzeit in 9–12 m langen Erdhöhlen, die in einer Kammer mit einigen Luftlöchern enden. In einer solchen Kammer überdauern bis zu 15 Krokodile die Trockenheit.

Nilkrokodile gehen nachts ins Wasser um zu jagen – sie sind generalistische Fleischfresser. Der Hauptbestandteil der Nahrung adulter Nilkrokodile ist Fisch; im Rudolfsee im Norden Kenias machen Fische 90 %,[3] im Okavango-Delta von Botswana bei subadulten Exemplaren 68 % der Nahrung aus.[7] Weitere Beutetiere sind Vögel, Schildkröten und kleine Säuger.[1] Große Nilkrokodile können auch Großsäuger erjagen. Sie lauern der Beute meist unter den Oberflächen von Flüssen oder Wasserstellen auf, an denen die Tiere zum Trinken eintreffen, und bleiben durch das flache Profil des Kopfes und die nahezu geräuschlose Fortbewegung unbemerkt. Das Opfer wird dann angesprungen, im Sprung gepackt, ins Wasser gezerrt und ertränkt. Unter anderem wurde von Zebras, Antilopen, Stachelschweinen, jungen Flusspferden und auch Raubtieren wie Hyänen oder Löwen berichtet, die von Nilkrokodilen erbeutet worden waren.[1] Aas gehört ebenfalls zur Nahrung des Nilkrokodils.

Junge Nilkrokodile ernähren sich von deutlich kleineren Beutetieren. Einjährige Nilkrokodile im Okavango-Delta ernähren sich zu 45,6 % von Insekten und Spinnen, zu 30,8 % von kleinen Säugern und nur zu 11,6 % von Fischen. Ebenfalls zum Nahrungsspektrum junger Krokodile gehören Amphibien und Reptilien, welche jedoch vergleichsweise selten erjagt werden.[7]

Nilkrokodil-Weibchen sind nicht territorial. Die Männchen bilden Reviere und verteidigen einen Uferabschnitt hartnäckig gegen andere Männchen. Sie schwimmen regelmäßig die Grenzen ihres Territoriums ab und vertreiben Eindringlinge. Gelegentlich kommt es zu Kämpfen.[8]

Die Paarungszeit ist innerhalb des großen Verbreitungsgebiets sehr variabel. Wenn ein Männchen ein Weibchen trifft, hebt es seinen Schwanz und Kopf an und brüllt. Es schwimmt dem Weibchen entgegen, welches schließlich ebenfalls seinen Kopf anhebt und brüllt. Das Männchen legt zur Paarung seine Vorderbeine auf das Weibchen und steigt von der Seite auf ihren Rücken. Nach 5 Monaten legt das Weibchen dann 16–80 Eier, die 85–125 g wiegen. Der Zeitpunkt der Eiablage ist ebenso wie die Paarungszeit höchst variabel. In Tansania werden die Eier zum Beispiel im November gelegt, am Victoria-Nil und Albertsee Ende Dezember bis Anfang Januar, am Ruzizi zwischen April und August und auf Madagaskar von September bis Oktober. Das Weibchen gräbt mit seinen Hinterbeinen etwa 5–10 m vom Wasser entfernt ein 35–40 cm tiefes Erdloch, in welches die Eier gelegt werden. Das Loch wird anschließend zugedeckt und zusätzlich ein Nisthügel aus Substrat und Pflanzenresten aufgeschüttet. Während der Inkubation bewacht das Weibchen sein Nest vor Nesträubern wie etwa dem Nilwaran (Varanus niloticus), an den die Krokodile dennoch oft Eier verlieren. Nach 84–89 Tagen kündigen die Jungtiere in den Eiern mit froschartigen Lauten ihren Schlupf an. Das Weibchen gräbt dann das Nest wieder aus und trägt die Schlüpflinge in ihrem Maul ins Wasser. In den ersten Lebensmonaten bleiben die Jungtiere immer dicht bei ihrer Mutter, die sie bewacht. Auf sich nähernde Feinde macht die Mutter durch starke Körpervibrationen aufmerksam, worauf die Jungtiere sofort abtauchen. Jungtiere, die von der Gruppe abgesondert wurden oder angegriffen werden, stoßen einen Hilferuf aus, worauf das Weibchen sofort zum Jungtier eilt, um es zu verteidigen. Die Nacht verbringen die Jungtiere auf dem Rücken ihrer Mutter. Dennoch werden in den ersten Wochen oft mehr als 50 % der Jungtiere Opfer von Krabben, großen Fischen, Nilwaranen, Reihern, Störchen, Hyänen und Mungos.

In der ersten Hälfte des 20. Jahrhunderts waren Nilkrokodile in ganz Afrika sehr häufig. In den folgenden Jahrzehnten sank der Bestand drastisch, da sie wegen ihrer Haut stark bejagt wurden. Krokodilleder wird zu zahlreichen Produkten wie Handtaschen, Gürteln etc. verarbeitet. Zusätzlichen Anreiz zur Jagd gaben Abschussprämien auf die Krokodile, da sie als Bedrohung für die Bevölkerung gesehen wurden. In den 1980er Jahren ging die Jagd aufgrund von Verboten zurück und Krokodilfarmen können heute den Bedarf der Lederindustrie decken. Auf diesen Farmen ist das Nilkrokodil eine der am häufigsten gehaltenen Arten.

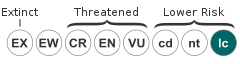

Die Rote Liste gefährdeter Arten der IUCN führte das Nilkrokodil bis 1996 als gefährdet (vulnerable), inzwischen gilt die Art als nicht bedroht (least concern).[9] Im Nil kommen die Tiere trotzdem kaum freilebend vor, sie leben in Naturschutzreservaten in breiten trägen Buchten.

Siehe Krokodile im alten Ägypten.

Bei Ausgrabungen von historischen Grabanlagen wurden auch mumifizierte Nilkrokodile gefunden. Im Jahr 2012 erhielten einige gut erhaltene Exemplare ein Museum an der Tempelanlage von Kom Ombo.[10]

Dem Nilkrokodil sind einige Lieder gewidmet, beispielsweise Das Krokodil am Nil oder Krokodil Theophil und weitere.[11][12]

Große Nilkrokodile können Menschen angreifen, die sich unvorsichtig in Krokodilgewässer begeben; Angriffe sind jedoch durch die enormen Bestandseinbrüche im 20. Jahrhundert weit seltener als früher geworden. Die meisten Zwischenfälle sind auf Übermut oder Unaufmerksamkeit der Opfer zurückzuführen.[13] CrocBITE, die weltweite Datenbank für Krokodilangriffe der Charles Darwin University, registrierte bisher (Stand: Jan. 2014) 557 Attacken durch Nilkrokodile auf Menschen, 394 davon endeten für das Opfer tödlich. Nur vom Leistenkrokodil sind mehr Angriffe auf Menschen bekannt.[14]

Zu Beginn des 21. Jahrhunderts ergeben sich verstärkt Konflikte zwischen Krokodilen und ansässigen Menschen, da einerseits die Bevölkerung rapide zunimmt, andererseits sich auch die Bestände der Krokodile erholen. Ebenso beklagt die lokale Bevölkerung, dass verstärkt Vieh gerissen wird und Fischernetze immer häufiger von Krokodilen beschädigt werden.

Das Nilkrokodil (Crocodylus niloticus) ist eine Art der Krokodile (Crocodylia) aus der Familie der Echten Krokodile (Crocodylidae). Die normalerweise 3–4 m lang werdende Art bewohnt Gewässer in ganz Afrika und ernährt sich größtenteils von Fischen. Gelegentlich können Nilkrokodile jedoch auch große Säugetiere (z. B. Zebras) unter Wasser zerren und ertränken. Das Nilkrokodil betreibt intensive Brutpflege, die Mutter bewacht ihr Nest und beschützt die Jungtiere in den ersten Lebensmonaten. Die Art nahm eine wichtige Rolle in der ägyptischen Mythologie ein und war einst wegen starker Bejagung gefährdet. Nachdem die Jagd in den 1980ern verboten wurde, haben sich die Bestände weitgehend erholt.

Aɣucaf n Nnil (assaɣ usnan: Crocodylus niloticus) d yiwen n uɣucaf meqqren (seld aɣucaf awlal) id yegran ur yengir ara, Yettidir ɣef yirawen n wasif n Nnil aladɣa deg tamiwin n uneẓul n Tefriqt adda n tneẓruft.

Azal n tiddi n uɣucaf n Nnil yessawad gar n 4,5 m ar 5 m, Ma d azuk-is azal n 410 kg.

Aɣucaf n Nnil (assaɣ usnan: Crocodylus niloticus) d yiwen n uɣucaf meqqren (seld aɣucaf awlal) id yegran ur yengir ara, Yettidir ɣef yirawen n wasif n Nnil aladɣa deg tamiwin n uneẓul n Tefriqt adda n tneẓruft.

Ang buwaya ng Nilo (Crocodylus niloticus) ay isang buwaya sa Aprika, ang pinakamalaking freshwater predator sa Africa, at maaaring isaalang-alang ang pangalawang pinakamalaking nabubuhay na reptilya sa mundo, matapos ang buwaya sa dagat (Crocodylus porosus). Ang buwaya ng Nilo ay napakalawak sa buong Sub-Saharan Africa, na kadalasang nagaganap sa gitnang, silangan, at timog na rehiyon ng kontinente at nabubuhay sa iba't ibang uri ng mga nabubuhay na kapaligiran tulad ng mga lawa, ilog at marshlands.

![]() Ang lathalaing ito ay isang usbong. Makatutulong ka sa Wikipedia sa nito.

Ang lathalaing ito ay isang usbong. Makatutulong ka sa Wikipedia sa nito.

Crocodylus niloticus es un specie de Crocodylus.

The Nile crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus) is an African crocodile an mey be conseedered the seicont lairgest extant reptile in the warld, efter the sautwatter crocodile (Crocodylus porosus).[2]

The Nile crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus) is an African crocodile an mey be conseedered the seicont lairgest extant reptile in the warld, efter the sautwatter crocodile (Crocodylus porosus).

Nėla krakuodėls (luotīnėškā: Crocodylus niloticus) ī ruoplis, prėgolons prī krakuodėlu (Crocodylidae), dėdliausis ė pavuojingiausis vėsuo Afrėkuo. Paplėtė̄s vėsom žemīnė, skīros Sakaras dīkoma. Gīven opiū ėr ežerū pakronties. Ėlgoms lėgė 6 m, sonkoms lėgė 750 kg. Jied žėndoulius (tēpuogi gal' ožpoltė ėr žmuonis), ruoplius, žovis.

Ο Κροκόδειλος του Νείλου (επιστημονική ονομασία: Crocodylus niloticus - Κροκόδειλος ο νειλοτικός) είναι ένας κροκόδειλος ο οποίος απαντάται στην Αφρική, από την Σενεγάλη μέχρι την Αίγυπτο και την Νότια Αφρική, ενώ έχουν βρεθεί πληθυσμοί και στην Μαδαγασκάρη. Παλιότερα ζούσε και στο Δέλτα του Νείλου, αλλά σήμερα έχει εξαφανιστεί εκεί. Θεωρείται το δεύτερο μεγαλύτερο κροκοδείλιο που ζει σήμερα μετά τον θαλάσσιο κροκόδειλο, με μήκος που μπορεί να φτάσει μέχρι τα 5,5 μέτρα σε πολύ ηλικιωμένα ζώα και βάρος μέχρι 750 κιλά. Ο μεγαλύτερος που έχει μετρηθεί ήταν ένα αρσενικό στην Τανζανία μήκους 6,47 μέτρων και βάρος 1.090 κιλά.

Το όνομα κροκόδειλος προέρχεται από την Αρχαία Ελλάδα, όπου σύμφωνα με τον Ηρόδοτο κροκόδριλος (από το κρόκος=κροκάλα=βότσαλο και δρίλος=σκουλήκι, άρα κρόκος+δρίλος=κροκόδριλος=το σκουλήκι που βγαίνει από τις πέτρες) ονομαζόταν το σημερινό κροκοδειλάκι ή κουρκουτά (Agama stellio). Πάντως, το μόνο κοινό ανάμεσα στον κροκόδειλο και την κουρκουτά είναι μόνο η κίνηση που κάνουν. Νειλοτικός σημαίνει αυτός που κατοικεί στο Νείλο. Άρα, κροκόδειλος ο Νειλοτικός λέγεται ο κροκόδειλος που κατοικεί στο Νείλο.

Ο κροκόδειλος του Νείλου κατατάσσεται στην τάξη των κροκοδειλίδων που περιλαμβάνει τρεις οικογένειες: την οικογένεια των αλλιγατορίδων στην οποία περιλαμβάνονται οι αλλιγάτορες και οι καϊμάν, στην οικογένεια των γαβιαλίδων που περιλαμβάνεται ο γαβιάλης του Γάγγη και στην οικογένεια των κροκοδειλίδων, στην οποία ανήκει ο κροκόδειλος του Νείλου. Οι κροκοδειλίδες υποδιαιρούνται σε 3 γένη: το Crocodylus, το Osteolaemus και στο Tomistoma. Ο κροκόδειλος του Νείλου ανήκει στο γένος Crocodylus, που εκτός από αυτόν περιλαμβάνει και τον κροκόδειλο της θάλασσας, τον κροκόδειλο του βούρκου και άλλα είδη.

Ο κροκόδειλος του Νείλου συναντάται κατά μήκος των οχθών του Νείλου και σε όλη την υποσαχάρια Αφρική. Παλιά είχε μια ευρύτατη κατανομή παό το Ακρωτήριο της Καλής Ελπίδας ως την Παλαιστίνη. Σήμερα η κατανομή του είνια αρκετά περιορισμένη, στη Μαδαγασκάρη, την Τανζανία, τη Σενεγάλη την Αίγυπτο, το Σουδάν, το Κονγκό, την Κένυα και τη Νότια Αφρική. Τα δύο κύρια πάρκα στα οποία προστατεύεται είναι το Εθνικό Πάρκο της λίμνης Ροδόλφου στην Κένυα και στο Εθνικό Πάρκο του Μούρχισον στο Βικτωριανό Νείλο. Οι κροκόδειλοι του Νείλου κατοικούνε κυρίως σε αμμουδερές και χορταριασμένες όχθες ποταμών ή λιμνών, δεν αποκλείουν όμως και στην ανάγκη βραχώδεις όχθες ή και όχθες με χαλίκια. Καμιά φορά οι κροκόδειλοι του Νείλου πηγαίνουν κατά την περίοδο των βροχών μέσα στα έλη, τα ρυάκια και τις λιμνούλες που δημιουργούνται στα τροπικά δάση και ύστερα από την απόσυρση των νερών παγιδεύονται εκεί μέσα. Αν περάσει πολύς καιρός και παγιδευτούν στον πυθμένα της λίμνης ή του ποταμού, πέφτουν σε λήθαργο ωσότου να καλυτερέψει ο καιρός και να μπορέσουν να βγουν, όσοι όμως μπορούν μεταναστεύουν σε γειτονικό ποταμό ή λίμνη.

Ο κροκόδειλος του Νείλου έχει μήκος 5-7 μέτρα και είναι καλυμμένος εξ' ολοκλήρου με φολίδες οι οποίες είναι λείες στην κοιλιά, τετράγωνες και εύκαμπτες. Οι φολίδες της ράχης είναι τραχείες και σκληρές και θωρακίζουν στην κυριολεξία τα ερπετά. Οι κροκόδειλοι που ζουν σε κατηφορικά ποτάμια έχουν πιο σκληρό δέρμα ενώ οι κροκόδειλοι των λιμνών, των ήρεμων ποταμών και των βάλτων έχουν πιο μαλακό δέρμα.

Ο Κροκόδειλος του Νείλου (επιστημονική ονομασία: Crocodylus niloticus - Κροκόδειλος ο νειλοτικός) είναι ένας κροκόδειλος ο οποίος απαντάται στην Αφρική, από την Σενεγάλη μέχρι την Αίγυπτο και την Νότια Αφρική, ενώ έχουν βρεθεί πληθυσμοί και στην Μαδαγασκάρη. Παλιότερα ζούσε και στο Δέλτα του Νείλου, αλλά σήμερα έχει εξαφανιστεί εκεί. Θεωρείται το δεύτερο μεγαλύτερο κροκοδείλιο που ζει σήμερα μετά τον θαλάσσιο κροκόδειλο, με μήκος που μπορεί να φτάσει μέχρι τα 5,5 μέτρα σε πολύ ηλικιωμένα ζώα και βάρος μέχρι 750 κιλά. Ο μεγαλύτερος που έχει μετρηθεί ήταν ένα αρσενικό στην Τανζανία μήκους 6,47 μέτρων και βάρος 1.090 κιλά.

Нил крокодилĕ (лат. Crocodylus niloticus) — «шуса çӳрекенсен» ушкăнĕн чăн крокодилсен йышне кĕрекен пысăк чĕрчун.

Африкара пурăнакан крокодилсен виçĕ тĕсĕсенчен чи пысăкки.

Нил крокодилĕ (лат. Crocodylus niloticus) — «шуса çӳрекенсен» ушкăнĕн чăн крокодилсен йышне кĕрекен пысăк чĕрчун.

Африкара пурăнакан крокодилсен виçĕ тĕсĕсенчен чи пысăкки.

Нилскиот крокодил (Crocodylus niloticus) е рептил од фамилијата Crocodylidae, кој ги населува повеќето региони во Африка (со исклучок на Северна Африка, Сејшели и Комори островите).

Просечната должина на ворасна индивидуа изнесува 4 метри, но забележани се и индивидуи кои надминуваат 7 метри како крокодилот од Бурунди наречен Густав.

Во антиката, нилските крокодили ја населувале делтата на реката Нил. Херодот запишал дека го населувале и езерото Моерис. Се смета дека изумреле во пределот на Сејшелите во почетокот на 19тиот век. Според пронајдените фосилни остатоци се знае дека го населувале и езерото Едвард. Нилискиот крокодил денес е распространет од реката Сенегал, езерото Чад и Судан до делтата на Окаванго. На Мадагаскар ги среќаваме во западните и јужните делови на островот. Повремено, овие животни се забележани и во Занзибар и на Комори [1].

Во западна Африка, нилскиот крокодил најчесто се сретнува во крајбрежните лагуни, делтите и во реките кои граничат со екваторијалниот шумски појас. Во источна Африка живеат во реки, езера, мочуришта и брани. Се случува понекогаш и да навлезат во океанот, па еден примерок во 1917та година бил забележан на 11 км од брегот на Санта Луција [1].

Нилскиот крокодил има темно бронзена боја на грбот со црни точки, додека стомакот му е со темно жолта боја. Страните кои се со жолто-зелена нијанса имаат темни дамки кои се протегаат како коси пруги. Постои и варијација на бојата на кожата во зависност од живеалиштето. Така, крокодилите што живеат во реки со брз тек се со посветла боја на кожата од крокодилите кои престојуваат во езера или мочуришта. Овие крокодили имаат очи со зелена боја[1], кои се заштитени со трепкачка ципа. Поседуваат и жлезди кои лачат солзи и го чистат окото.

Како и останатите крокодили и овие поседуваат четири кратки расчекорени нозе, долга опашка и моќни вилици. Кожата им е крекриена со крлушки и редови од коскени израстоци кои се протегаат во долж на нивниот грб и опашка.

Ноздрите, очите и ушите се наоѓаат на врвот на главата, што им овозможува додека го држат целото тело под вода, истовремено да слушаат и да ја гледаат околината. Младите крокодили имаат сива или кафеава боја со потемни пруги на телото и опашката. Како растат тие добиваат се потемна боја, а пругите, поготово оние на телото, исчезнуваат.

Овие крокодили најчесто лазат на стомак, но исто така можат и да одат со телото издигнато од земјата. Помалите индивидуи можат и да галопираат, а некои од поголемите крокодили можат да достигнат брзина и до 12-14 km/h. Овие животни се одлични пливачи, и пливаат со тоа што го мрдаат телото и опашката на синусоиден начин. Можат да пливаат подолго и со брзина од 30-35 km/h.

Нилскиот крокодил поседува срце со 4 комори, кое е доста ефикасно во оксидирање на крвта. Најчесто нуркаат само неколку минути, но доколку се во опасност можат да останат под вода и до 30 минути, а доколку не се движат можат да го задржат здивот и до 2 часа.

Силата на загризот на возрасен нилски крокодили измерена од страна на доктор Брејди Бар (Brady Barr) изнесува 22 kN. Сепак мускулите кои служат за отварање на вилицата се доста слаби, што му овозможува на човекот да ја држи затворена устата на крокодилот употребувајќи малку сила[2]. Овие животи поседуваат помеѓу 64 и 68 заби. Младите крокодили поседуваат специфичен тврд кожен израсток на врвот на устата кој служи за кршење на лушпата на јајцето при нивното изведување, и кој брзо го снемува.

Нилскиот крокодил е најголемото крокодиловидно животно во Африка и се смета за втор најголем крокодил после морскиот крокодил. Најчесто достигнуваат должина од 3,7 до 5 метри, но регистрирани се индивидуи и од 6 метри[3]. Просечен мажјак тежи околу 545 килограми[4], но во ретки случаи достигнуваат и до 909 килограми[5]. Најголемиот мажјак нилски крокодил бил убиен во Танзанија и бил дол долг 6,45 метри и тежел околу 1090 килограми[6]. Како и останатите крокодиловидни животни, и кај нилскиот крокодил постои полов диморфизам, така што мажјаците се за околу 30% поголеми од женките. Возрасните женки достигнуваат должина од 4 метри и тежат околу 300 килограми.

Постојат пријави за крокодили кои биле долги 7 метри, меѓутоа поради честото преценување на големината, постојат големи сомневања во веродостојноста на овие изјави. Најголемиот жив примерок се чини дека е човекојадниот нилски крокодил од Бурунди со име Густав, за кој се верува дека е долг 6 метри. Вакви џинови се ретки денес, но биле многу чести во минатото кога имало многу поголеми популации на крокодили, многу повеќе природно живеалиште и пред претераниот лов во 1940тите и 1950тите години.

Постојат одредени докази кои укажуваат на тоа дека нилските крокодили кои живеат на поладна клима, како во јужните делови на Африка, се помали и достигаат должина од само 4 метри. Постојат и џуџести нилски крокодили во Мали и во пустината Сахара кои растат само 2 до 3 метри во должина. Се претпоставува дека нивната големина се должи на лошите услови за живот а не на генетските предиспозиции.

Нилскиот крокодил е опортунистички суперпредатор кој го напаѓа било кое животно. Младите крокодили се доста мали, па затоа на почетокот се хранат со мал плен како инсекти и мали без’рбетници, а потоа брзо напредуваат кон водоземци, рептили и птици. Иако се суперпредатори, дури и на возрасните крокодили главна храна им претставуваат рибите и други мали рбетници. Сепак возрасните индивидуи преферираат поголем плен со цел да заштедат енергија. Нилските крокодили не пребираат многу во однос на исхраната, па напаѓаат скоро било кое животно кое доаѓа да пие вода на работ од реката[7]. Најчест плен од цицачите се зебра, дива свиња, антилопа, коза, овца, гну и домашно говедо. Поголеми хербивори како жирафа или бафало се исто така плен повремено[1]. Предатори како хиените, леопардите и други крокодили, вклучувајќи и индивидуи од истиот вид, се исто така регистрирани пленови на нилскиот крокодил. За крај, постои најмалку еден запис за група крокодили кои убиваат женка од Црн носорог во реката Тана во Кенија [1].

Возрасните нилски крокодили ги употребуваат телото и опашката за да ги насочат јатата риби кон плитак и потоа ги јадат со нагло завртување на главата. Крокодилите знаат и да соработуваат, односно тие се групираат и формираат полукруг во реката со што ги блокираат рибите кои мигрираат. Доминантниот мажјак секогаш јаде прв.

Способноста да лежат скриени во вода, комбинирано со големата брзина на кратки дистанци, ги прави овие животни ефикасни опортунистички ловци на голем плен. Тие го зграбуваат пленот со моќните вилици, го одвлекуваат во вода и го држат под вода сè додека не се удави. Групи на крокодили можат да патуваат стотици метри во должина на реката за да се хранат со мрша.

Кога пленот е мртов тие го јадат со откинување на парчиња месо. Кога група на крокодили го дели убиениот плен, ја користат силата на загриз и на другите крокодили за да откинуваат поголеми парчиња месо. Тие загризуваат и потоа го превртуваат целото тело. Ова движење се нарекува и „смртоносно превртување“. Доколку крокодилот е сам, како поддршка може да користи и гранки или камења на кои го прикачуваат пленот.

Нилските крокодили се познати и по симбиотската врска со некои птици, како пловерот. Според одредени записи, крокодилот широко ја отвора устата, птицата влегува и ги чисти забите од малите парченца месо кои се заглавени меѓи нив. Ова сѐ уште е тешко да се докаже, и најверојатно не претставува вистинска симбиотска врска.

Мажјаците достигнуваат сексуална зрелост кога се долги околу 3 метри, додека женките кога се долги 2-2,5 метри. И на двата пола, за да ги достигнат овие должини им се потребни околу 10 години во нормални услови.

За време на сезоната за парење, мажјаците ги привлекуваат женките со рикање, плескање по водата со муцката, исфрлање вода низ носот како и испуштање на многу други звуци, кои сепак се многу помалку вокални од американсиот алигатор [1]. Според набљудувањата поголемите мажјаци се доста поуспешни во привлекување на женките. Женките ги несат јајцата околу 2 месеци после парењето.

Градењето гнездо се одвива во ноември или декември, односно за време на сувиот период во Северна Африка, и за време на дождовниот период во Јужна Африка. Најчесто гнездата ги градат на песочни брегови и пресушени речни текови. Женката копа дупка длабока 50тина сантиметри оддалечена неколку метри од брегот, во која положува од 25 до 80 јајца. Бројот на јајцата се разликува во различни популации, но во просек изнесува 50 јајца. Се случува повеќе женки да ги изградат гнездата многу блиску едни до други.

За разлика од останатите крокодили, кои гнездата ги прават од растенија, женката од нилски крокодил јајцата ги закопува во песок[1]. Откако ќе ги закопа, идната мајка го чува гнездото за време на целиот период на инкубација кој трае 3 месеци. Идниот татко исто така останува во близина на гнездото, и заедно со мајката постојано напаѓаат доколку некој се доближи до јајцата. И покрај постојаната грижа на двајцата родители, гнездата многу често се уништувани од луѓето, гуштерите или некои други животни, за време кога мајката е на кратко отсутна.

Пред да излезат од јајцата, младите крокодили испуштаат пискави звуци кои се сигнал за мајката да го откопа гнездото. И мајката и таткото ги земаат јајцата во устата и ги тркалаат помеѓу јазикот и горниот дел од устата со што помагаат во кршењето на лушпата и излегувањето на младите. Кога ќе излезат од јајцата, мајката ги носи младите до водата.

Одредувањето на полот на младите крокодили е зависен од температурата, што значи дека полот не е одреден генетски, туку во зависност од просечната температура за време на втората третина од периодот на инкубација. Ако температурата во гнездото е пониска од 31,7 °C или повисока од 34.5 °C, младите ќе бидат женски. Ако температурата е во рамките на овие степени, младите крокодили ќе бидат машки.

Младите крокодили се долги околи 30 сантиметри, и одприлика ја растат истата должина секоја година. Мајката се грижи за младите во следните две години, а доколку има повеќе гнезда во околината мајките формираат колонија каде сите заедно се грижат за своите и за младенчињата на другите женки. За ова време, мајката ги заштитува младите носејќи ги во својата уста или на нејзиниот грб.Младите крокодили не можат сами да се исхрануваат,и затоа ги храни нивната мајка.Додека не направат 2 години тие се сеуште мали за да се бранат и затоа не се одделуваат од својата мајка.Ако некое од малите крокодили умре не мајката го јаде.Кон крајот на втората година, младите крокодили веќе достигнуваат должина од 1,2 метри и го напуштаат регионот, но истовремено и ги избегнуваат териториите на поголемите и поворасните крокодили.

Должината на животниот век на крокодилите не е доволно познат, но се смета дека поголемите крокодили како Нилскиот живеат доста долго. Се претпоставува дека просечниот животен век изнесува помеѓу 70 и 100 години.

Од 1940тите до 1960тите, нилскиот крокодил е ловен најмногу поради неговата високо-квалитетна кожа, но исто така и поради неговото месо. Популацијата била драстично намалена, и видот се соочувал со изумирање. Националните закони и регулативите за тргување со крокодилска кожа, го спречиле ова изумирање и видот не е повеќе загрозен. Програмите за заштита на овие крокодили се всушност вештечки околини каде крокодилите живеат на сигурно и каде не се загрозени од ловци.

Се проценува дека има помеѓу 250 000 и 500 000 индивидуи во дивината. Нилскиот крокодил е доста распространет, со стабилни регистрирани популации во многу земји во источна Африка вклучувајќи ги Сомалија, Етиопија, Кенија и Замбија. Поради постојаната побарувачка на крокодилска кожа, постојат и фарми на крокодили. Во 1993 година, произведени се 80 000 крокодилски кожи, од кои повеќето се од крокодилските фарми во Зимбабве и Јужна Африка.

Ситуацијата е многу посериозна во централна и западна Африка, што сочинува околу две третини од живеалиштето на нилскиот крокодил. Крокодилските популации во овој регион се доста поретки и недоволно проучувани. Се смета дека природните популации се поретки поради лошите услови и компетицијата со африканскиот крокодил и џуџестиот крокодил. Дополнителни фактори се загубата на мочуриштата кои се природни живеалишта на овие животни како и ловењето во 1970тите години. Потребни се дополнителни програми за заштита за да се решат овие проблеми.

Нилскиот крокодил е суперпредатор во неговата околина, и е одговорен за регулирање на популациите на одредени видови на риби. Нилскиот крокодил се храни и со мртви животни кои доколку не се изедени можат да ја загадат водата. Најголемата опасност за нилскиот крокодил е човекот. Со заштитата ловокрадствотото веќе не претставува проблем, но затоа опасноста доаѓа од загадувањето на околината и сличајните заплеткувања во рибарските мрежи.

Како оправдување за ловот на овие крокодили се наведува опасноста за луѓето и е познат како голем човекојадец. За разлика од останатите човекојадни крокодили како морскиот крокодил, нилскиот живее во региони во близина на човечки популации, па затоа контактот со луѓе е многу почест. Иако нема сигурни бројки, се смета дека нилскиот крокодил убива неклоку стотици луѓе годишно, што е повеќе од сите други крокодили заедно[8]. Некои проценуваат дека бројката на годишни жртви надминува и илјада[9].

Заштитниот статус на Нилскиот крокодил од Црвената листа на IUCN од 1996 година спаѓа во видови со најмала загриженост од изумирање. Според листата на CITES овој крокодил спаѓа во Апендикс I (загрозен вид) во повеќето региони каде што е распространет, и во Апендикс II (незагрозен, но трговијата мора да биде контролирана).

Луѓето од Стар Египет го обожувале Собек, крокодил-бог кој бил повржуван со плодноста, заштитата и моќта на фараонот. Собек бил насликуван како крокодил, како мумуфициран крокодил или како човек со глава од крокодил. Центар на неговото обожување било Средното Кралство, градот Арсиное, кај грцитe познат како Крокодополис.

Според Херодот, во 5тиот век п.н.е., некои еѓипјани чувале крокодили како домашни миленичиња. Во храмот на Собек кој се наоѓал во Арсиное, еден крокодил бил чуван во безенот во храмот, каде бил хранет, прекриван со накит и обожуван. Кога крокодилот умирал тој бил балсамиран, мумифициран, ставан во саркофаг и потоа закопуван во света гробница. Многу мумифицирани крокодили па дури и крокодилски јајца се пронајдени во египетските гробници.

Во Стар Египет биле употребувани магии за да се смират крокодилите, па дури и во денешно време, нубијските рибари закачуваат крокодили над праговите за да ги заштитат од зло.

Биномното име Crocodylus niloticus е добиено од грчкиот збор kroko („камен“), deilos („црв“ или „човек“), што се однесува на неговата специфична кожа, и niloticus, што значи „од реката Нил“.

Нилскиот крокодил (Crocodylus niloticus) е рептил од фамилијата Crocodylidae, кој ги населува повеќето региони во Африка (со исклучок на Северна Африка, Сејшели и Комори островите).

Просечната должина на ворасна индивидуа изнесува 4 метри, но забележани се и индивидуи кои надминуваат 7 метри како крокодилот од Бурунди наречен Густав.

நைல் முதலை (விலங்கியல் பெயர்:குரோக்கோடைலஸ் நைலோட்டிகஸ்) ஆப்பிரிக்காவில் காணப்படும் மூன்று முதலைச் சிற்றினங்களில்(species) ஒன்றாகும். மேலும் இவை முதலைச் சிற்றினங்களிலேயே இரண்டாவது பெரியதும் ஆகும். நைல் முதலைகள் ஏறக்குறைய ஆப்பிரிக்கா முழுதும் சகாராவின் தென்பகுதியிலும் மடகாஸ்கர் தீவிலும் காணப்படுகின்றன.

நைல் முதலை (விலங்கியல் பெயர்:குரோக்கோடைலஸ் நைலோட்டிகஸ்) ஆப்பிரிக்காவில் காணப்படும் மூன்று முதலைச் சிற்றினங்களில்(species) ஒன்றாகும். மேலும் இவை முதலைச் சிற்றினங்களிலேயே இரண்டாவது பெரியதும் ஆகும். நைல் முதலைகள் ஏறக்குறைய ஆப்பிரிக்கா முழுதும் சகாராவின் தென்பகுதியிலும் மடகாஸ்கர் தீவிலும் காணப்படுகின்றன.

Nkɔli (latɛ́ : Crocodylus niloticus) ezalí nyama o libóta lya nyóka ya nzelá ya mái. Ezalí ngandó eye elíyaka bato mpé nyama isúsu, evándaka o mái ya ebale tǒ ya molúká, ekokí kobima o mokili na makáká ma mikúsé ma yangó. Ezalí na monɔkɔ ya molaí .

Nkɔli (latɛ́ : Crocodylus niloticus) ezalí nyama o libóta lya nyóka ya nzelá ya mái. Ezalí ngandó eye elíyaka bato mpé nyama isúsu, evándaka o mái ya ebale tǒ ya molúká, ekokí kobima o mokili na makáká ma mikúsé ma yangó. Ezalí na monɔkɔ ya molaí .

Ọ̀ni Nílò (Crocodylus niloticus) je iru ọ̀ni ti Afrika to wopo si Somalia, Ethiopia, Uganda, Kenya, Egypt, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

The Nile crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus) is a large crocodilian native to freshwater habitats in Africa, where it is present in 26 countries. It is widely distributed throughout sub-Saharan Africa, occurring mostly in the central, eastern, and southern regions of the continent, and lives in different types of aquatic environments such as lakes, rivers, swamps, and marshlands.[4] In West Africa, it occurs along with two other crocodilians.[5] Although capable of living in saline environments, this species is rarely found in saltwater, but occasionally inhabits deltas and brackish lakes. The range of this species once stretched northward throughout the Nile, as far north as the Nile Delta. Generally, the adult male Nile crocodile is between 3.5 and 5 m (11 ft 6 in and 16 ft 5 in) in length and weighs 225 to 750 kg (500 to 1,650 lb).[6][7] However, specimens exceeding 6.1 m (20 ft) in length and 1,000 kg (2,200 lb) in weight have been recorded.[8] It is the largest freshwater predator in Africa, and may be considered the second-largest extant reptile in the world, after the saltwater crocodile (Crocodylus porosus).[9][10] Size is sexually dimorphic, with females usually about 30% smaller than males. The crocodile has thick, scaly, heavily armoured skin.

Nile crocodiles are opportunistic apex predators; a very aggressive crocodile, they are capable of taking almost any animal within their range. They are generalists, taking a variety of prey.[11][10] Their diet consists mostly of different species of fish, reptiles, birds, and mammals. They are ambush predators that can wait for hours, days, and even weeks for the suitable moment to attack. They are agile predators and wait for the opportunity for a prey item to come well within attack range. Even swift prey are not immune to attack. Like other crocodiles, Nile crocodiles have a powerful bite that is unique among all animals, and sharp, conical teeth that sink into flesh, allowing a grip that is almost impossible to loosen. They can apply high force for extended periods of time, a great advantage for holding down large prey underwater to drown.[10]

Nile crocodiles are relatively social.[12] They share basking spots and large food sources, such as schools of fish and big carcasses. Their strict hierarchy is determined by size. Large, old males are at the top of this hierarchy and have first access to food and the best basking spots. Crocodiles tend to respect this order; when it is infringed, the results are often violent and sometimes fatal.[13] Like most other reptiles, Nile crocodiles lay eggs; these are guarded by the females and males, making the Nile crocodiles one of few reptile species whose males contribute to parental care.[14] The hatchlings are also protected for a period of time, but hunt by themselves and are not fed by the parents.[11][15]

The Nile crocodile is one of the most dangerous species of crocodile and is responsible for hundreds of human deaths every year.[16] It is common and is not endangered, despite some regional declines or extirpations.

The binomial name Crocodylus niloticus is derived from the Greek κρόκη, kroke ("pebble"), δρῖλος, drilos ("worm"), referring to its rough skin; and niloticus, meaning "from the Nile River". The Nile crocodile is called[17] timsah al-nil in Arabic, mamba in Swahili, garwe in Shona, ngwenya in Ndebele, ngwena in Venda, kwena in Sotho and Tswana, and tanin ha-yeor in Hebrew. It also sometimes referred to as the African crocodile, Ethiopian crocodile, and common crocodile.[18][10][19]

Although no subspecies are currently formally recognized, as many as seven have been proposed, mostly due to variations in appearance and size noted in various populations throughout Africa. These have consisted of C. n. africanus (informally named the East African Nile crocodile), C. n. chamses (the West African Nile crocodile), C. n. cowiei (the South African Nile crocodile), C. n. madagascariensis (the Malagasy or Madagascar Nile crocodile, regionally also known as the croco Mada, which translates to Malagasy crocodile), C. n. niloticus (the Ethiopian Nile crocodile; this would be the nominate subspecies), C. n. pauciscutatus (the Kenyan Nile crocodile) and C. (n.) suchus (now widely considered a separate species).[20][21]

In a study of the morphology of the various populations, including C. (n.) suchus, the appearance of the Nile crocodile sensu lato was found to be more variable than that of any other currently recognized crocodile species, and at least some of these variations were related to locality.[22] For example, a study on Lake Turkana in Kenya (informally this population would be placed in C. n. pauciscutatus) found that the local crocodiles have more osteoderms in their ventral surface than other known populations, and thus are of lesser value in leather trading, accounting for an exceptionally large (possibly overpopulated) local population there in the late 20th century.[23] The segregation of the West African crocodile (C. suchus) from the Nile crocodile has been supported by morphological characteristics,[22][24] studies of genetic materials[21][24] and habitat preferences.[25] The separation of the two is not recognized by the IUCN as their last evaluations of the group was in 2008 and 2009,[2][26] years before the primary publications supporting the distinctiveness of the West African crocodiles.[22][24][25]

Although originally thought to be the same species as the West African crocodile, genetic studies using DNA sequencing have revealed that the Nile crocodile is actually more closely related to the crocodiles of the Americas, namely the American (C. acutus), Cuban (C. rhombifer), Morelet's (C. moreletii), and Orinoco crocodiles (C. intermedius).[24][27][28][29][30][31] The fossil species C. checchiai from the Miocene in Kenya was about the same size as the modern Nile crocodiles and shared similar physical characteristics to the modern species,[27][28][32] and analysis of C. checchiai supports their close relationship and the theory of the Nile crocodile being the base of the evolutionary radiation of the New World crocodiles.[33] Dispersal across the Atlantic from Africa is thought to have occurred 5 to 6 million years ago.[34][35]

At one time, the fossil species Rimasuchus lloydi was thought to be the ancestor of the Nile crocodile, but more recent research has indicated that Rimasuchus, despite its very large size (about 20–30% bigger than a Nile crocodile with a skull length estimated up to 97 cm (38 in)), is more closely related to the dwarf crocodile (Osteolaemus tetraspis) among living species.[23][27] Two other fossil species from Africa retained in the genus Crocodylus appear to be closely related to the Nile crocodile: C. anthropophagus from Plio-Pleistocene Tanzania and C. thorbjarnarsoni from Plio-Pleistocene Kenya. C. anthropophagus and C. thorbjarnarsoni were both somewhat larger, with projected total lengths up to 7.5–7.6 m (24 ft 7 in – 24 ft 11 in).[27][28][32] As well as being larger, C. anthropophagus and C. thorbjarnarsoni, as well as Rimasuchus spp., were all relatively broad-snouted, indicating a specialization at hunting sizeable prey, such as large mammals and freshwater turtles, the latter much larger than any in present-day Africa.[27][28] Studies have since shown these other African crocodiles to be only more distantly related to the Nile crocodile.[30][31]

Below is a cladogram based on a 2018 tip dating study by Lee & Yates simultaneously using morphological, molecular (DNA sequencing), and stratigraphic (fossil age) data,[30] as revised by the 2021 Hekkala et al. paleogenomics study using DNA extracted from the extinct Voay.[31]

CrocodylinaeVoay†

CrocodylusCrocodylus Tirari Desert†

Asia+AustraliaCrocodylus johnstoni Freshwater crocodile ![]()

Crocodylus novaeguineae New Guinea crocodile

Crocodylus mindorensis Philippine crocodile

Crocodylus porosus Saltwater crocodile ![]()

Crocodylus siamensis Siamese crocodile ![]()

Crocodylus palustris Mugger crocodile ![]()

Crocodylus suchus West African crocodile

Crocodylus niloticus Nile crocodile ![]()

Crocodylus moreletii Morelet's crocodile

Crocodylus rhombifer Cuban crocodile ![]()

Crocodylus intermedius Orinoco crocodile

Crocodylus acutus American crocodile ![]()

Adult Nile crocodiles have a dark bronze colouration above, with faded blackish spots and stripes variably appearing across the back and a dingy off-yellow on the belly, although mud can often obscure the crocodile's actual colour.[19] The flanks, which are yellowish-green in colour, have dark patches arranged in oblique stripes in highly variable patterns. Some variation occurs relative to environment; specimens from swift-flowing waters tend to be lighter in colour than those dwelling in murkier lakes or swamps, which provides camouflage that suits their environment, an example of clinal variation. Nile crocodiles have green eyes.[10] The colouration also helps to camouflage them; juveniles are grey, multicoloured, or brown, with dark cross-bands on the tail and body.[36] The underbelly of young crocodiles is yellowish green. As they mature, Nile crocodiles become darker and the cross-bands fade, especially those on the upper-body. A similar tendency in coloration change during maturation has been noted in most crocodile species.[20][37]

Most morphological attributes of Nile crocodiles are typical of crocodilians as a whole. Like all crocodilians, for example, the Nile crocodile is a quadruped with four short, splayed legs, a long, powerful tail, a scaly hide with rows of ossified scutes running down its back and tail, and powerful, elongated jaws.[36][38] Their skin has a number of poorly understood integumentary sense organs that may react to changes in water pressure, presumably allowing them to track prey movements in the water.[39] The Nile crocodile has fewer osteoderms on the belly, which are much more conspicuous on some of the more modestly sized crocodilians. The species, however, also has small, oval osteoderms on the sides of the body, as well as the throat.[37][40] The Nile crocodile shares with all crocodilians a nictitating membrane to protect the eyes and lachrymal glands to cleanse its eyes with tears. The nostrils, eyes, and ears are situated on the top of the head, so the rest of the body can remain concealed under water.[38][41] They have a four-chambered heart, although modified for their ectothermic nature due to an elongated cardiac septum, physiologically similar to the heart of a bird, which is especially efficient at oxygenating their blood.[42][43] As in all crocodilians, Nile crocodiles have exceptionally high levels of lactic acid in their blood, which allows them to sit motionless in water for up to 2 hours. Levels of lactic acid as high as they are in a crocodile would kill most vertebrates.[20] However, exertion by crocodilians can lead to death due to increasing lactic acid to lethal levels, which in turn leads to failure of the animal's internal organs. This is rarely recorded in wild crocodiles, normally having been observed in cases where humans have mishandled crocodiles and put them through overly extended periods of physical struggling and stress.[12][23]

The mouths of Nile crocodiles are filled with 64 to 68 sharply pointed, cone-shaped teeth (about a dozen less than alligators have). For most of a crocodile's life, broken teeth can be replaced. On each side of the mouth, five teeth are in the front of the upper jaw (premaxilla), 13 or 14 are in the rest of the upper jaw (maxilla), and 14 or 15 are on either side of the lower jaw (mandible). The enlarged fourth lower tooth fits into the notch on the upper jaw and is visible when the jaws are closed, as is the case with all true crocodiles.[12][38] Hatchlings quickly lose a hardened piece of skin on the top of their mouths called the egg tooth, which they use to break through their eggshells at hatching. Among crocodilians, the Nile crocodile possesses a relatively long snout, which is about 1.6 to 2.0 times as long as broad at the level of the front corners of the eyes.[44] As is the saltwater crocodile, the Nile crocodile is considered a species with medium-width snout relative to other extant crocodilian species.[5]

In a search for the largest crocodilian skulls in museums, the largest verifiable Nile crocodile skulls found were several housed in Arba Minch, Ethiopia, sourced from nearby Lake Chamo, which apparently included several specimens with a skull length more than 65 cm (26 in), with the largest one being 68.6 cm (27.0 in) in length with a mandibular length of 87 cm (34 in). Nile crocodiles with skulls this size are likely to measure in the range of 5.4 to 5.6 m (17 ft 9 in to 18 ft 4 in), which is also the length of the animals according to the museum where they were found. However, larger skulls may exist, as this study largely focused on crocodilians from Asia.[10][45] The detached head of an exceptionally large Nile crocodile (killed in 1968 and measuring 5.87 m (19 ft 3 in) in length) was found to have weighed 166 kg (366 lb), including the large tendons used to shut the jaw.[9]

The bite force exerted by an adult Nile crocodile has been shown by Brady Barr to measure 22 kN (5,000 lbf). However, the muscles responsible for opening the mouth are exceptionally weak, allowing a person to easily hold them shut, and even larger crocodiles can be brought under control by the use of duct tape to bind the jaws together.[46] The broadest snouted modern crocodilians are alligators and larger caimans. For example, a 3.9 m (12 ft 10 in) black caiman (Melanosuchus niger) was found to have a notably broader and heavier skull than that of a Nile crocodile measuring 4.8 m (15 ft 9 in).[47] However, despite their robust skulls, alligators and caimans appear to be proportionately equal in biting force to true crocodiles, as the muscular tendons used to shut the jaws are similar in proportional size. Only the gharial (Gavialis gangeticus) (and perhaps some of the few very thin-snouted crocodilians) is likely to have noticeably diminished bite force compared to other living species due to its exceptionally narrow, fragile snout. More or less, the size of the tendons used to impart bite force increases with body size and the larger the crocodilian gets, the stronger its bite is likely to be. Therefore, a male saltwater crocodile, which had attained a length around 4.59 m (15 ft 1 in), was found to have the most powerful biting force ever tested in a lab setting for any type of animal.[48][49]

The Nile crocodile is the largest crocodilian in Africa, and is generally considered the second-largest crocodilian after the saltwater crocodile.[10] Typical size has been reported to be as much as 4.5 to 5.5 m (14 ft 9 in to 18 ft 1 in), but this is excessive for actual average size per most studies and represents the upper limit of sizes attained by the largest animals in a majority of populations.[11][36][37] Alexander and Marais (2007) give the typical mature size as 2.8 to 3.5 m (9 ft 2 in to 11 ft 6 in); Garrick and Lang (1977) put it at from 3.0 to 4.5 m (9 ft 10 in to 14 ft 9 in).[50][9][13] According to Cott (1961), the average length and weight of Nile crocodiles from Uganda and Zambia in breeding maturity was 3.16 m (10 ft 4 in) and 137.5 kg (303 lb).[11] Per Graham (1968), the average length and weight of a large sample of adult crocodiles from Lake Turkana (formerly known as Lake Rudolf), Kenya was 3.66 m (12 ft 0 in) and body mass of 201.6 kg (444 lb).[51] Similarly, adult crocodiles from Kruger National Park reportedly average 3.65 m (12 ft 0 in) in length.[10] In comparison, the saltwater crocodile and gharial reportedly both average around 4 m (13 ft 1 in), so are about 30 cm (12 in) longer on average, and the false gharial (Tomistoma schlegelii) may average about 3.75 m (12 ft 4 in), so may be slightly longer, as well. However, compared to the narrow-snouted, streamlined gharial and false gharial, the Nile crocodile is more robust and ranks second to the saltwater crocodile in total average body mass among living crocodilians, and is considered to be the second-largest extant reptile.[9][51][10][37] The largest accurately measured male, shot near Mwanza, Tanzania, measured 6.45 m (21 ft 2 in) and weighed about 1,043–1,089 kg (2,300–2,400 lb).[9] Another large male measuring 5.8 m (19 ft 0 in) in total length (Cott 1961) was among the largest Nile crocodiles ever recorded. It was estimated to weigh 1,082 kg (2,385 lb).[52]

Like all crocodiles, they are sexually dimorphic, with the males up to 30% larger than the females, though the difference is considerably less compared to some species, like the saltwater crocodile. Male Nile crocodiles are about 30 to 50 cm (12 to 20 in) longer on average at sexual maturity and grow more so than females after becoming sexually mature, especially expanding in bulk after exceeding 4 m (13 ft 1 in) in length.[36][53] Adult male Nile crocodiles usually range in length from 3.3 to 5.0 m (10 ft 10 in to 16 ft 5 in) long; at these lengths, an average sized male may weigh from 150 to 750 kg (330 to 1,650 lb).[11][51][54][55][56] Very old, mature ones can grow to 5.5 m (18 ft 1 in) or more in length (all specimens over 5.5 m (18 ft 1 in) from 1900 onward are cataloged later).[9][10][57] Large mature males can reach 1,000 kg (2,200 lb) or more in weight.[58] Mature female Nile crocodiles typically measure 2.2 to 3.8 m (7 ft 3 in to 12 ft 6 in), at which lengths the average female specimen would weigh 40 to 250 kg (88 to 551 lb).[11][51][36][59]

An old male individual, named "Big Daddy", housed at Mamba Village Centre, Mombasa, Kenya is considered to be one of the largest living Nile crocodiles in captivity. It measures 5 m (16 ft 5 in) in length and weighs 800 kg (1,800 lb). In 2007, at the Katavi National Park, Brady Barr captured a specimen measuring 5.36 m (17 ft 7 in) in total length (with a considerable portion of its tail tip missing). The weight of this specimen was estimated to be 838 kg (1,847 lb), making it one of the largest crocodiles ever to be captured and released alive.[52] The bulk and mass of individual crocodiles can be fairly variable, some animals being relatively slender, while others being very robust; females are often bulkier than males of a similar length.[11][10] As an example of the body mass increase undergone by mature crocodiles, one of the larger crocodiles handled firsthand by Cott (1961) was 4.4 m (14 ft 5 in) and weighed 414.5 kg (914 lb), while the largest specimen measured by Graham and Beard (1973) was 4.8 m (15 ft 9 in) and weighed more than 680 kg (1,500 lb).[11][9][60] One of the largest known specimens from South Africa, caught by J.G Kuhlmann in Venda, which was 5.5 m (18 ft 1 in) long weighed 905.7 kg (1,997 lb).[61] On the other hand, another individual measuring 5.87 m (19 ft 3 in) in length was estimated to weigh between 770–820 kg (1,700–1,800 lb).[62] In attempts to parse the mean male and female lengths across the species, the mean adult length was estimated to be reportedly 4 m (13 ft 1 in) in males, at which males would average about 280 kg (620 lb) in weight, while that of the female is 3.05 m (10 ft 0 in), at which females would average about 116 kg (256 lb).[11][51][63][64] This gives the Nile crocodile somewhat of a size advantage over the next largest non-marine predator on the African continent, the lion (Panthera leo), which averages 188 kg (414 lb) in males and 124 kg (273 lb) in females, and attains a maximum known weight of 313 kg (690 lb), far less than that of large male crocodiles.[9][65]

Nile crocodiles from cooler climates, like the southern tip of Africa, may be smaller, reaching maximum lengths of only 4 m (13 ft 1 in). A crocodile population from Mali, the Sahara Desert, and elsewhere in West Africa reaches only 2 to 3 m (6 ft 7 in to 9 ft 10 in) in length,[66] but it is now largely recognized as a separate species, the West African crocodile.[24]

The Nile crocodile is presently the most common crocodilian in Africa, and is distributed throughout much of the continent. Among crocodilians today, only the saltwater crocodile occurs over a broader geographic area,[67] although other species, especially the spectacled caiman (Caiman crocodilus) (due to its small size and extreme adaptability in habitat and flexibility in diet), seem to actually be more abundant.[68] This species’ historic range, however, was even wider. They were found as far north as the Mediterranean coast in the Nile Delta and across the Red Sea in Israel, Palestine and Syria. The Nile crocodile has historically been recorded in areas where they are now regionally extinct. For example, Herodotus recorded the species inhabiting Lake Moeris in Egypt. They are thought to have become extinct in the Seychelles in the early 19th century (1810–1820).[10][36] Today, Nile crocodiles are widely found in, among others, Somalia, Ethiopia, Uganda,[69] Kenya, Egypt, the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Tanzania, Rwanda, Burundi, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Gabon, Angola, South Africa, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, Sudan, South Sudan, Botswana, and Cameroon.[26] The Nile crocodile's current range of distribution extends from the regional tributaries of the Nile in Sudan and Lake Nasser in Egypt to the Cunene river of Angola, the Okavango Delta of Botswana, and the Olifants river in South Africa.[70]

Isolated populations also exist in Madagascar, which likely colonized the island after the extinction of the endemic crocodile Voay.[71][72] In Madagascar, crocodiles occur in the western and southern parts from Sambirano to Tôlanaro. They have been spotted in Zanzibar and the Comoros in modern times, but occur very rarely.[10]

The species was previously thought to extend in range into the whole of West and Central Africa,[73][74] but these populations are now typically recognized as a distinct species, the West African (or desert) crocodile.[24] The distributional boundaries between these species were poorly understood, but following several studies, they are now better known. West African crocodiles are found throughout much of West and Central Africa, ranging east to South Sudan and Uganda where the species may come into contact with the Nile crocodile. Nile crocodiles are absent from most of West and Central Africa, but range into the latter region in eastern and southern Democratic Republic of Congo, and along the Central African coastal Atlantic region (as far north to Cameroon).[24][75] Likely a level of habitat segregation occurs between the two species, but this remains to be confirmed.[25][76]

Nile crocodiles may be able to tolerate an extremely broad range of habitat types, including small brackish streams, fast-flowing rivers, swamps, dams, and tidal lakes and estuaries.[53] In East Africa, they are found mostly in rivers, lakes, marshes, and dams, favoring open, broad bodies of water over smaller ones. They are often found in waters adjacent to various open habitats such as savanna or even semi-desert but can also acclimate to well-wooded swamps, extensively wooded riparian zones, waterways of other woodlands and the perimeter of forests.[77][78][79] In Madagascar, the remnant population of Nile crocodiles has adapted to living within caves.[10] Nile crocodiles may make use of ephemeral watering holes on occasion.[80] Although not a regular sea-going species as is the American crocodile, and especially the saltwater crocodile, the Nile crocodile possesses salt glands like all true crocodiles (i.e., excluding alligators and caimans), and does on occasion enter coastal and even marine waters.[81] They have been known to enter the sea in some areas, with one specimen having been recorded 11 km (6.8 mi) off St. Lucia Bay in 1917.[11][82]

Nile crocodiles have been recently captured in South Florida, though no signs that the population is reproducing in the wild have been found.[83] Genetic studies of Nile crocodiles captured in the wild in Florida have revealed that the specimens are all closely related to each other, suggesting a single source of the introduction. This source remains unclear, as their genetics do not match samples collected from captives at various zoos and theme parks in Florida. When compared to Nile crocodiles from their native Africa, the Florida wild specimens are most closely related to South African Nile crocodiles.[84] It is unknown how many Nile crocodiles are currently at large in Florida.[85][86] The animals likely were either brought there to be released or are escapees.[87]

Generally, Nile crocodiles are relatively inert creatures, as are most crocodilians and other large, cold-blooded creatures. More than half of the crocodiles observed by Cott (1961), if not disturbed, spent the hours from 9:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. continuously basking with their jaws open if conditions were sunny. If their jaws are bound together in the extreme midday heat, Nile crocodiles may easily die from overheating.[11][88] Although they can remain practically motionless for hours on end, whether basking or sitting in shallows, Nile crocodiles are said to be constantly aware of their surroundings and aware of the presence of other animals.[10] However, mouth-gaping (while essential to thermoregulation) may also serve as a threat display to other crocodiles. For example, some specimens have been observed mouth-gaping at night, when overheating is not a risk.[15] In Lake Turkana, crocodiles rarely bask at all through the day, unlike crocodiles from most other areas, for unknown reasons, usually sitting motionless partially exposed at the surface in shallows, with no apparent ill effects from the lack of basking on land.[60]

In South Africa, Nile crocodiles are more easily observed in winter because of the extensive amount of time they spend basking at this time of year. More time is spent in water on overcast, rainy, or misty days.[89] In the southern reaches of their range, as a response to dry, cool conditions that they cannot survive externally, crocodiles may dig and take refuge in tunnels and engage in aestivation.[36] Pooley found in Royal Natal National Park that during aestivation, young crocodiles of 60 to 90 cm (24 to 35 in) total length would dig tunnels around 1.2 to 1.8 m (3 ft 11 in to 5 ft 11 in) in depth for most, with some tunnels measuring more than 2.7 m (8 ft 10 in), the longest there being 3.65 m (12 ft 0 in). Crocodiles in aestivation are lethargic, entering a state similar to animals that hibernate. Only the largest individuals engaging in aestivation leave the burrow to sun on the warmest days; otherwise, these crocodiles rarely left their burrows. Aestivation has been recorded from May to August.[10][36]

Nile crocodiles usually dive for only a few minutes at a time, but can swim under water up to 30 minutes if threatened. If they remain fully inactive, they can hold their breath for up to 2 hours (which, as aforementioned, is due to the high levels of lactic acid in their blood).[20] They have a rich vocal range and good hearing. Nile crocodiles normally crawl along on their bellies, but they can also "high walk" with their trunks raised above the ground. Smaller specimens can gallop, and even larger individuals are capable of occasional, surprising bursts of speed, briefly reaching up to 14 km/h (8.7 mph).[11][90] They can swim much faster, moving their bodies and tails in a sinuous fashion, and they can sustain this form of movement much longer than on land, with a maximum known swimming speed of 30 to 35 km/h (19 to 22 mph), more than three times faster than any human.[91]

Nile crocodiles have been widely known to have gastroliths in their stomachs, which are stones swallowed by animals for various purposes. Although this is clearly a deliberate behaviour for the species, the purpose is not definitively known. Gastroliths are not present in hatchlings, but increase quickly in presence within most crocodiles examined at 2–3.1 m (6 ft 7 in – 10 ft 2 in) and yet normally become extremely rare again in very large specimens, meaning that some animals may eventually expel them.[11][10] However, large specimens can have a large number of gastroliths. One crocodile measuring 3.84 m (12 ft 7 in) and weighing 239 kg (527 lb) had 5.1 kg (11 lb) of stones in its stomach, perhaps a record gastrolith weight for a crocodile.[11] Specimens shot near Mpondwe on the Semliki River had gastroliths in their stomach despite being shot miles away from any sources for the stones; the same holds true for specimens from Kafue Flats, Upper Zambesi and Bangweulu Swamp, all of which often had stones inside them despite being nowhere near stony regions. Cott (1961) felt that gastroliths were most likely serving as ballast to provide stability and additional weight to sink in water, this bearing great probability over the theories that they assist in digestion and staving off hunger.[11][10] However, Alderton (1998) stated that a study using radiology found that gastroliths were seen to internally aid the grinding of food during digestion for a small Nile crocodile.[23]

Herodotus claimed that Nile crocodiles have a symbiotic relationship with certain birds, such as the Egyptian plover (Pluvianus aegyptius), which enter the crocodile's mouth and pick leeches feeding on the crocodile's blood, but no evidence of this interaction actually occurring in any crocodile species has been found, and it is most likely mythical or allegorical fiction.[92] However, Guggisberg (1972) had seen examples of birds picking scraps of meat from the teeth of basking crocodiles (without entering the mouth) and prey from soil very near basking crocodiles, so felt it was not impossible that a bold, hungry bird may occasionally nearly enter a crocodile's mouth, but not likely as a habitual behaviour.[10]

Nile crocodiles are apex predators throughout their range. In the water, this species is an agile and rapid hunter relying on both movement and pressure sensors to catch any prey unfortunate enough to present itself inside or near the waterfront.[93] Out of water, however, the Nile crocodile can only rely on its limbs, as it gallops on solid ground, to chase prey.[94] No matter where they attack prey, this and other crocodilians take practically all of their food by ambush, needing to grab their prey in a matter of seconds to succeed.[10] They have an ectothermic metabolism, so can survive for long periods between meals. However, for such large animals, their stomachs are relatively small, not much larger than a basketball in an average-sized adult, so as a rule, they are anything but voracious eaters.[12] Young crocodiles feed more actively than their elders, according to studies in Uganda and Zambia. In general, at the smallest sizes (0.3–1 m (1 ft 0 in – 3 ft 3 in)), Nile crocodiles were most likely to have full stomachs (17.4% full per Cott); adults at 3–4 m (9 ft 10 in – 13 ft 1 in) in length were most likely to have empty stomachs (20.2%). In the largest size range studied by Cott, 4–5 m (13 ft 1 in – 16 ft 5 in), they were the second most likely to either have full stomachs (10%) or empty stomachs (20%).[11] Other studies have also shown a large number of adult Nile crocodiles with empty stomachs. For example, in Lake Turkana, Kenya, 48.4% of crocodiles had empty stomachs.[51] The stomachs of brooding females are always empty, meaning that they can survive several months without food.[10]

The Nile crocodile mostly hunts within the confines of waterways, attacking aquatic prey or terrestrial animals when they come to the water to drink or to cross.[36] The crocodile mainly hunts land animals by almost fully submerging its body under water. Occasionally, a crocodile quietly surfaces so that only its eyes (to check positioning) and nostrils are visible, and swims quietly and stealthily toward its mark. The attack is sudden and unpredictable. The crocodile lunges its body out of water and grasps its prey. On other occasions, more of its head and upper body is visible, especially when the terrestrial prey animal is on higher ground, to get a sense of the direction of the prey item at the top of an embankment or on a tree branch.[10] Crocodile teeth are not used for tearing up flesh, but to sink deep into it and hold on to the prey item. The immense bite force, which may be as high as 5,000 lbf (22,000 N) in large adults, ensures that the prey item cannot escape the grip.[95] Prey taken is often much smaller than the crocodile itself, and such prey can be overpowered and swallowed with ease. When it comes to larger prey, success depends on the crocodile's body power and weight to pull the prey item back into the water, where it is either drowned or killed by sudden thrashes of the head or by tearing it into pieces with the help of other crocodiles.[19]