pt-BR

nomes no trilho de navegação

Romerolagus diazi lives on the upper slopes of an extinct volcanic range south of Mexico City, ranging from 2800 m to 4250 m, and an average elevation of 3252 m. Although it is near the equator and in the tropics, conditions are temperate as a result of high altitude and local weather patterns. Winters constitute the dry season, and summers are exceptionally rainy. Aside from the wet and dry seasons, conditions are relatively stable throughout the year, leaving a long growing season, with an average temperature of 9.6 C. Vegetation throughout consists of tall zacatón bunch grass under sparse pine and alder coverage. Romerolagus diazi relies heavily on these grasses for survival and evasion of predators. It can also be found in dense patches of secondary forest.

Range elevation: 2800 to 4250 m.

Average elevation: 3252 m.

Habitat Regions: temperate ; tropical ; terrestrial

Terrestrial Biomes: forest ; scrub forest ; mountains

Other Habitat Features: agricultural

Romerolagus diazi is native to the Chichinautzin range of extinct volcanoes 200 miles south of Mexico City. Primarily, they live in a 280 sq. km region spread across the slopes of the mountains Pelado, Tialoc, Popocatepetl and Ixtaccíhuatl. Romerolagus diazi is endemic to the Chichinautzin Mountains.

Biogeographic Regions: nearctic (Native )

Romerolagus diazi feeds primarily on zacaton grass, but also consumes young herbs and bark. During the summer rainy season, it sometimes feeds on cultivated plants. In captivity, R. diazi eats zacaton grasses provided in their enclosure, as well as other traditional rabbit foods, including high-protein chinchilla pellets, fruits, grasses, and other vegetable material. Young R. diazi begin eating solid food at 15 to 16 days after birth and are completely weaned by 3 weeks of age. Similar to other lagomorphs, R. diazi sometimes consumes their feces as a method of retaining as much nutrition and water as possible. Specific plant species eaten by R. diazi include aromatic mint plant, numerous species of zacaton grass (Festuca amplissima, Stipa ichu, Epicampes), two genera of spiny grass (Erynigium and Cyrsium), lady's mantle, and Museniopsis arguta.

Plant Foods: leaves; wood, bark, or stems; seeds, grains, and nuts; flowers

Other Foods: dung

Primary Diet: herbivore (Folivore ); coprophage

Little is known of the ecological role that Romerolagus diazi fills in its ecosystem. It is a folivore and may disperse seeds throughout its habitat. This species is prey for bobcats, long-tailed weasels, coyotes, red-tailed hawks and probably a number of other carnivorous mammals and birds. Romerolagus diazi is host to a number of endoparasites including roundworms (Boreostrongylus romerolagi, Thichostrongylus calcaratus, Longistrata dubia, Dermatoxys veligera), whipworms (Trichuris leporis), and flatworms (Anoplocephaloides romerolagi). It is also host to a number of ectoparasites, including various species of flies, ticks, and fleas.

Commensal/Parasitic Species:

There are no known positive effects of Romerolagus diazi on humans.

Romerolagus diazi occasionally feeds on cultivated plants. If it were more abundant, it may have a significant negative affect on local agriculture.

Romerolagus diazi lives immediately south of Mexico City, one of the largest metropolitan areas in the world containing nearly 21 million inhabitants. As a result, while populations are listed as increasing by IUCN's Red List of Threatened Species, growth and sprawl of the city continues to threaten the habitat of R. diazi. In addition to urban sprawl, other major threats include habitat fragmentation and destruction due to wild fires and agriculture. Recently, R. diazi has increased, likely due to protective legislation focused on habitat preservation. Additionally, part of their range is within protected national parks. Currently, around 7000 individuals are estimated to exist in the wild.

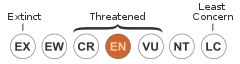

US Federal List: endangered

CITES: appendix i

State of Michigan List: no special status

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: endangered

Romerolagus diazi is the only member of family Leporidae that is known to vocalize, reacting to help their young and making noises themselves when startled, similar to pikas. They make two different types of calls: a short high-pitched bark, and a more subtle, slightly less audible squeak. They also communicate through thumping their hind feet on the ground. Reproductive status is communicated via scent glands located on the chin and groin.

Communication Channels: acoustic ; chemical

Other Communication Modes: pheromones ; scent marks

Perception Channels: visual ; tactile ; acoustic ; chemical

While there is no data on the lifespan of Romerolagus diazi, similar species have been observed to live less than a year in the wild. Some lagomorphs, however, may live up to 12 years in the wild.

Romerolagus diazi has small, short hind legs and feet; small, rounded ears; and a vestigial tail. Dorsal and lateral fur is yellowish brown, and individual hairs are black at the tips and base, resulting in a grizzled appearance. The venter is buff or light grey. Like all members of the family Leporidae, it has large, well positioned eyes that give it a broad viewing range. It is considered the most primitive of extant leporids and is often described as the second smallest leporid behind Brachylagus idahoensis. Romerolagus diazi is sexually dimorphic, with males weighing on average 417 g and females, 536 g. Newborns are altricial and have closed eyes, laid-back ears, and extremely fine brown fur at birth. The vestigial tail is visible in newborns, but not in adults. Romerolagus diazi bears a striking resemblance to members of the family Ochotonidae, and its skull resembles that of Ochotonidae, as both lack an anterior bony projection above the eye socket.

Range mass: 386 to 602.5 g.

Range length: 234 to 321 mm.

Other Physical Features: endothermic ; homoiothermic; bilateral symmetry

Sexual Dimorphism: female larger

Romerolagus diazi lacks the speed of many of its close relatives. Instead, it relies on finding cover in the grasses and rocks of its habitat. To protect their young, female volcano rabbits create burrows in and around patches of zacaton grass, digging slightly into the ground and reinforcing these burrows with the nearby grasses to offer both shelter and security. Romerolagus diazi has also been observed to make noise vocally when threatened. Major predators of this species include long-tailed weasels, bobcats, coyotes, and red-tailed hawks.

Known Predators:

Anti-predator Adaptations: cryptic

Only captive Romerolagus diazi have been observed during mating. Thus, no data are available concerning mating systems of wild populations. It communicates with conspecifics via scent glands under the chin and in their groin, and scent glands likely play a significant role in mating and signaling social status to conspecifics. In captivity, R. diazi is serially monogamous (e.g., multiple pair bondings). Mate access is determined by social status, and only the dominant female and dominant male mate. If either individual dies, however, they are replaced by the highest ranking individual in the hierarchy.

Mating System: monogamous

Breeding occurs year round in Romerolagus diazi but peaks during spring. Females have induced ovulation and in captivity reach sexual maturity by 8 months old. Captive males reach sexual maturity by 5 months old. Gestation lasts for 38 to 40 days and results in 1 to 4 offspring per litter, which weigh about 80 g per kitten. Females can have 4 to 5 litters per year. Typically, offspring are weaned by 3 weeks of age.

Breeding interval: Romerolagus diazi can mate 4 to 5 times per year

Breeding season: Breeding in Romerolagus diazi occurs year-round, but peaks in spring and early summer

Range number of offspring: 1 to 4.

Average number of offspring: 4.

Range gestation period: 38 to 42 days.

Average gestation period: 39 days.

Average weaning age: 3 weeks.

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female): 8 months.

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male): 5 months.

Key Reproductive Features: iteroparous ; year-round breeding ; gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); sexual ; induced ovulation ; fertilization ; viviparous

Little is known of parental care in Romerolagus diazi in the wild. In captivity, mothers nurse semi-altricial young until weaning is complete at around 3 weeks of age. In the wild, R. diazi digs shallow holes in clumps of zacaton bunch grass, which hide nests and protect young. Nests consist primarily of vegetation fragments and fur. In captivity, R. diazi females avoid their nests unless young vocalize distress calls.

Parental Investment: altricial ; female parental care ; pre-hatching/birth (Provisioning: Female, Protecting: Female); pre-weaning/fledging (Provisioning: Female)

El conill dels volcans (Romerolagus diazi), conegut a Mèxic com teporingo o zacatuche, és un petit conill que viu a les muntanyes d'aquest país. És el segon conill més petit del món, només superat pel conill pigmeu. Té unes petites orelles rodones, potes curtes i un espès pelatge curt. El conill dels volcans viu en grups d'entre dos i cinc animals dins de caus. A diferència de moltes espècies de conill (i de manera similar a les piques), el conill dels volcans emet sons molt aguts per avisar els altres conills d'un perill, en lloc de picar amb els peus a terra. És nocturn i molt actiu durant el crepúscul, l'albada i l'entremig. El conill dels volcans pesa aproximadament 390-600 g. El 1969 se'n van comptar entre 1.000 i 1.200 en estat salvatge.

El conill dels volcans (Romerolagus diazi), conegut a Mèxic com teporingo o zacatuche, és un petit conill que viu a les muntanyes d'aquest país. És el segon conill més petit del món, només superat pel conill pigmeu. Té unes petites orelles rodones, potes curtes i un espès pelatge curt. El conill dels volcans viu en grups d'entre dos i cinc animals dins de caus. A diferència de moltes espècies de conill (i de manera similar a les piques), el conill dels volcans emet sons molt aguts per avisar els altres conills d'un perill, en lloc de picar amb els peus a terra. És nocturn i molt actiu durant el crepúscul, l'albada i l'entremig. El conill dels volcans pesa aproximadament 390-600 g. El 1969 se'n van comptar entre 1.000 i 1.200 en estat salvatge.

Králík lávový (Romerolagus diazi Ferrari-Pérez, 1893) také známý jako Romerův a ve své domovině nazývaný také Teporingo nebo Zacatochin je nejvzácnější a nejohroženější králík světa.

Jeho domovem jsou borové lesy ve výškách od 2 800 m do 4 200 m na úbočích pouhých čtyř sopek u Mexika. Zde žije v porostech husté trávy, které se tamní řečí říká „zakaton“. Od toho také pochází jeden z domorodých názvů tohoto králíka Zacatochin. Tyto porosty tvoří tvrdé kostřavy, kavyl a další druhy trav. Králíci využívají možnosti skvělých úkrytů v zakatonu, které jsou zároveň zdrojem jejich potravy.

Králík lávový (Romerolagus diazi Ferrari-Pérez, 1893) také známý jako Romerův a ve své domovině nazývaný také Teporingo nebo Zacatochin je nejvzácnější a nejohroženější králík světa.

Das Vulkankaninchen (Romerolagus diazi) ist eine Säugetierart aus der Familie der Hasen (Leporidae). Es gehört zu den kleinsten Arten der Familie und kommt endemisch ausschließlich in der Gebirgsregion im zentralen Teil Mexikos vor und wird dort als Zacatuche oder Teporingo bezeichnet. Dort lebt es vorwiegend im Gebiet der Vulkane Popocatépetl und Iztaccíhuatl, worauf auch sein deutscher und englischer Trivialname Bezug nimmt. Die Tiere sind einheitlich gelbbraun bis schwarz gefärbt, sie haben vergleichsweise kurze Ohren und der Schwanz ist äußerlich nicht sichtbar. Sie leben im Unterwuchs von Kiefern- und Erlenwäldern in Höhen von 2800 bis 4250 Metern, wobei die Lebensräume stark von dicht wachsenden Büschelgräsern („zacatón“) und von steinigem bis felsigem Untergrund geprägt sind.

Die Tiere bilden Gruppen von zwei bis fünf Individuen und ernähren sich von Gräsern und Kräutern. Sie graben Baue in den Waldboden oder nutzen die verlassenen Höhlen anderer Tierarten. Vorwiegend zwischen April und September werden durchschnittlich zwei Jungtiere geboren. Die Art steht unter strengem Schutz und wird aufgrund des sehr kleinen Verbreitungsgebietes als bedroht eingestuft.

Das Vulkankaninchen hat eine Kopf-Rumpf-Länge von etwa 23 bis 35 Zentimetern und ein Gewicht von etwa 380 bis 600 Gramm. Kleiner ist in seiner Familie nur noch das im Westen der Vereinigten Staaten lebende Zwergkaninchen (Brachylagus idahoensis). Ein Sexualdimorphismus ist nur gering ausgeprägt, die Weibchen sind in der Regel etwas größer als die Männchen. Der Schwanz ist sehr kurz und von außen nicht sichtbar; wie bei den Pfeifhasen ist er durch einen ihn überdeckenden Hautlappen verdeckt. Die Länge der Schwanzwirbel beträgt etwa 18 bis 31 Millimeter. Die Hinterbeine und die Füße sind vergleichsweise klein, die Hinterfußlänge beträgt im Durchschnitt etwa 51 Millimeter mit einer Varianz von 42 bis 55 Millimetern. Die Ohren sind klein und gerundet, sie erreichen eine Länge von 40 bis 45 Millimeter.[1][2][3]

Das Fell ist sehr kurz und dicht, es ist auf der Rückenseite einheitlich dunkel gelbbraun bis grau oder schwarz gefärbt. Dabei sind die Basen und die Spitzen der Fellhaare schwarz und der mittlere Teil gelblich. Die Kehle, die Brust und die Bauchseite sind heller sandbraun mit dunkelgrauem Einschlag der Unterwolle. Auf der Brust befindet sich eine „Mähne“ aus etwas längeren und weicheren Haaren, die in der Farbe der restlichen Brustbehaarung entspricht und sich von dieser nicht absetzt. Die Hinterbeine und die Füße sind kurz, die Oberseiten der Vorderfüße sind hell sandgelb, die der Hinterfüße braun. Die Füße besitzen jeweils fünf Zehen, auch wenn ihre Spuren häufig nur vier Zehen zeigen. Die Seiten der Nase und die Augenregion sind hell sandbraun, die Basis der kurzen und runden Ohren ist etwas dunkler sandbraun.[1] Hinter den Ohren befindet sich ein undeutliches Dreieck aus gelblichen Haaren.[3]

Die Weibchen besitzen drei Paar Zitzen, jeweils eines im Brust-, im Abdomen- und im Lendenbereich.[2] Während der Stillzeit schwellen die Milchdrüsen auf eine Dicke von etwa einem Millimeter an und bilden zwei jeweils zwei Zentimeter breite Streifen, die die jeweils vorderen beiden Zitzen verbinden. Dabei produzieren die Weibchen nie in allen Zitzen Milch und besitzen in der Regel vier wechselnde aktive Zitzen.[1]

Der Schädel erreicht eine Gesamtlänge von etwa 45 bis 47 Millimetern und eine maximale Breite von 25 bis 27 Millimetern im Bereich der Jochbögen. Er entspricht in seinem generellen Aufbau dem eines typischen Hasenartigen. Die Länge der Nasenbeine beträgt etwa 22 bis 25 Millimeter bei einer Breite von 9,5 bis 11,5 Millimetern und das Gaumenbein ist mit einer Länge von etwa 6 bis 8 Millimetern im Vergleich zu anderen Arten verlängert. Der bei einigen Hasen typische Processus postorbitalis, ein Knochenvorsprung hinter dem Auge, ist bei dieser Art nur kurz ausgebildet. Die Paukenhöhlen sind nicht vergrößert und entsprechen dem Foramen magnum in der Größe. Die Gehörgänge sind dagegen im Vergleich zu anderen Hasenartigen verlängert und erreichen eine Länge von 5,2 bis 6,4 Millimetern.[1]

Die Tiere besitzen im Oberkiefer jeweils zwei Schneidezähne (Incisivi) gefolgt von einer längeren Zahnlücke (Diastema) sowie von drei Vorbackenzähnen (Praemolares) und von drei Backenzähnen (Molares). Im Unterkieferast sind außer den drei Backenzähnen nur ein Schneidezahn sowie nur zwei Prämolaren vorhanden. Insgesamt besitzen die Tiere also 28 Zähne. Die Länge der Zahnreihe beträgt etwa 10 bis 12 Millimeter.[1]

Der Karyotyp besteht aus einem diploiden Chromosomensatz von 2n = 48 Chromosomen mit einer Armanzahl (fundamental number, FN) von 78. Er entspricht dem aller Vertreter der Gattung Lepus sowie dem des Strauchkaninchens (Sylvilagus bachmani) und wird als ursprüngliches Merkmal betrachtet,[2] wobei andere Arten der Gattungen Sylvilagus und andere Kaninchenarten eine variable Chromosomenzahl von 2n = 42 bis 52 aufweisen. Es handelt sich um einen Karyotyp mit 16 metazentrischen und 7 telozentrischen Chromosomen sowie zwei großen Geschlechtschromosomen (subtelozentrisches X und metazentrisches Y).[1]

Die wichtigsten Spuren der Vulkankaninchen sind Fußspuren und Kotspuren. Erstere bestehen in der Regel aus Abdrücken der Vorder- und der Hinterfüße, wobei meistens je nur vier Zehen erkennbar sind. Die Vorderfußspuren haben eine Länge von etwa 3 Zentimetern und die Hinterfußspuren eine Länge von etwa 4,6 Zentimetern, die Breite beträgt bei beiden etwa 1,5 Zentimeter. Trittsiegel laufender Vulkankaninchen entsprechen denen anderer Kaninchen, aufgrund der geringeren Größe sind sie jedoch näher beieinander. Die Vorderfüße kommen in der Regel mit einem Abstand von 10 bis 12 Zentimetern hinter den letzten Hinterfußspuren auf. Die Kotpillen der Tiere sind linsenförmig mit einem Durchmesser von 5 bis 9 Millimeter. Frische Pillen sind ockerfarben und weich, später werden sie gelblich und trocken. Sie können vor allem nahe der Baue und der Hauptwege der Tiere gefunden werden.[1]

Das Vulkankaninchen kommt endemisch in Zentralmexiko vor. Das Verbreitungsgebiet beschränkt sich auf die Gebirgsregion im transmexikanischen Vulkangürtel um die Vulkane Popocatépetl, Iztaccíhuatl, El Pelado und Tlaloc (Sierra Volcánica Transversal) in Morelos, im Westen von Puebla und im südlichen Umland von Mexiko-Stadt („Distrito Federal“). Bei intensiven Suchen in den angrenzenden Gebieten in den 1980er Jahren konnten keine weiteren Vorkommen identifiziert werden.[4] Die Gesamtfläche des Verbreitungsgebietes beträgt maximal etwa 386 Quadratkilometer, wodurch das Vulkankaninchen wahrscheinlich das am engsten eingegrenzte Verbreitungsgebiet aller Säugetiere in Mexiko hat. Historisch war das Gebiet etwas größer: Die Art ist unter anderem von den östlichen Ausläufern des Iztaccihuatl sowie der Nevado de Toluca verschwunden; zudem verringert sich das Gebiet aufgrund der Fragmentierung und Umnutzung in der Region zunehmend.[5]

Der Lebensraum des Vulkankaninchens sind Kiefern- und seltener Erlenwälder der Höhenlagen mit dichtem Unterbewuchs aus hohen und dicht wachsenden Büschelgräsern („zacatón“) und einem steinigen bis felsigen Untergrund, durchsetzt von Bereichen mit dunklen und tiefen Böden. Die Höhenverbreitung der Art liegt zwischen 2800 und 4250 Metern, die höchste Bestandsdichte befindet sich allerdings in Höhen von 3150 bis 3400 Metern.[5] Sie besiedelt auch Gebiete mit plötzlichen und steilen Abhängen.[2] Diese Habitate im Grenzbereich zwischen der nearktischen und neotropischen Zone[4] sind geprägt von warmen und feuchten Sommern und kalten und trockenen Wintern, der jährliche Niederschlag beträgt durchschnittlich 1330 Millimeter und die Durchschnittstemperatur über das Jahr etwa 9,5 °Celsius. Die Vegetation besteht vor allem aus bis etwa 25 Meter hohen Beständen der Montezuma-Kiefer (Pinus montezumae), teilweise durchsetzt mit anderen Kiefernarten wie Pinus hartwegii, Pinus teocote, Pinus rudis, Pinus patula und Pinus pseudostrobus. Der Unterwuchs setzt sich aus bis zu 5 Meter hohen Gräsern, hauptsächlich Arten wie Muhlenbergia macroura, Festuca amplissima, Festuca rosei, Stipa ichu sowie Epicampus-Arten zusammen. Hinzu kommen sekundäre Bestände der Erle Alnus acuminata subsp. arguta (Syn. Alnus arguta) mit Höhen bis 12 Meter und der palmenähnlichen Agavenart Furcraea bedinghausii, die bis zu 6 Meter hoch wird, sowie einem Unterwuchs aus Sommerflieder (Buddleja), Brombeeren (Rubus), Wasserdost (Eupatorium) und anderen krautigen Pflanzen. Die Auflage erreicht zusammen mit den Gräsern Höhen von 2 bis 5 Metern mit einem hohen Anteil an Gräsern und Kräutern. Seltener besiedelt das Vulkankaninchen auch temporär Felder mit Saat-Hafer (Avena sativa) und verlässt diese nach der Haferernte Anfang Oktober.[2]

Vulkankaninchen leben häufig in kleinen Gruppen von zwei bis fünf Individuen. Sie sind vorwiegend dämmerungsaktiv am Abend und am frühen Morgen, können aber auch am Tag und in der Nacht außerhalb ihrer Baue angetroffen werden. Sie meiden allerdings die Mittagshitze. Während dieser Zeiten suchen sie nach Nahrung und gehen anderen Aktivitäten nach, darunter auch dem „Hinterherlaufen“, dem „Kämpfen“ und dem „Spielen“. Die Nahrung der Tiere besteht aus grünen Blättern verfügbarer Gräser und Kräuter, vor allem den „zacatón“-Gräsern Festuca amplissima, Festuca rosei, Muhlenbergia macroura und Stipa ichu. Hinzu kommen Kräuter wie Cunita tritifolium, Alchemilla sebaldiaefolia und Museniopsis arguta. Dabei fressen die Kaninchen in der Regel die jungen und noch grünen Triebe der Gräser und beißen die Blätter an der Basis des Stiels ab. Während der Regenzeiten fressen die Tiere auch junge Hafer- und Maispflanzen in landwirtschaftlich genutzten Flächen nahe ihrer Baue.[1]

Die Ruhezeiten verbringen sie in den Bauen, deren versteckte Eingänge sich an der Basis von Grasbüscheln befinden. Diese Baue sind bis zu 5 Meter lang und haben oft mehrere Ausgänge, oft teilen sich die Gruppen einen gemeinsamen Bau. Die Baue haben eine maximale Länge von etwa fünf Metern und sind aufgrund des steinigen Untergrunds selten geradlinig. Sie werden teilweise nicht selbst gegraben, sondern stammen von andern grabenden Tieren der Habitate wie dem Silberdachs (Taxidea taxus), dem Felsenziesel (Otospermophilus variegatus), dem Neunbinden-Gürteltier (Dasypus novemcinctus) oder der Merriam-Taschenratte (Cratogeomys merriami). Als temporärer Unterschlupf werden zudem Höhlen zwischen Steinen und Holzstämmen oder Erdlöcher genutzt.[2][1] Die Nester für die Jungtiere werden von den Weibchen in einem flachen Bau angelegt, der in der Regel an der Basis von Grasbüscheln in den Boden gegraben wird; der Nesteingang wird unter Pflanzenmaterial versteckt. Eher selten kommen auch Nester im Bereich von Geröll und Steinen vor. Ein einzelnes Nest hat einen Durchmesser von etwa 15 Zentimetern und eine Höhe von etwa 11 Zentimetern. Als Nestmaterial wird trockene Vegetation wie Gras, Blätter und Zweige verwendet, die durch Haare der Mutter ausgepolstert wird.[2]

Innerhalb ihrer Gruppen wurden Hierarchien mit einem dominanten Weibchen beobachtet, in der Regel sind ein männliches Tier und maximal ein oder zwei Weibchen sexuell aktiv. Untereinander verständigen sie sich mit variablen und hohen Pfeiftönen, die an die der Pfeifhasen erinnern und bei anderen Hasen und Kaninchen nicht ausgeprägt sind, sowie durch Trommeln mit den Hinterpfoten.[2] Nach einzelnen Beobachtungen erhöht sich die Ruffrequenz nach einem Regen.[1]

Innerhalb in Gefangenschaft gehaltener Gruppen wurden Aggressionen beobachtet, die in der Regel von dominanten Weibchen ausgehen und sich meist gegen andere Weibchen und seltener gegen Männchen richten.[2]

Eine feste Paarungs- und Fortpflanzungssaison gibt es für die Vulkankaninchen nicht, sie können das ganze Jahr über Nachwuchs zur Welt bringen. Die Männchen sind das gesamte Jahr fortpflanzungsfähig, ihre Hoden liegen entsprechend über das gesamte Jahr im Hodensack. Der Höhepunkt der Geburten liegt im warmen und regenreichen Sommer, es wurden jedoch trächtige Weibchen von Januar bis Oktober und laktierende Weibchen von Februar bis Dezember identifiziert. In der Gefangenschaft verpaaren sich die Männchen in der Regel immer mit dem gleichen Weibchen und erst, wenn dieses nicht mehr vorhanden ist, mit einem anderen Weibchen. Die Begattung kann während des gesamten Tages stattfinden. Zur Paarung nähert sich das Männchen in der Regel von hinten an das Weibchen an und bleibt dort stehen, häufig beschnüffelt es danach die Hinterbeine und das Hinterteil des Weibchens. Danach dreht sich das Weibchen zu dem Männchen um und flankiert es und es folgen mehrere rasche Umrundungen, bevor das Männchen das Weibchen besteigt und dieses mit ein paar Beckenstößen begattet.[2]

Die Nester für die Jungtiere finden sich vor allem zwischen April und September. Die Tragzeit beträgt rund 38 bis 41 Tage und ist damit etwas länger als die der meisten Baumwollschwanzkaninchen und Pfeifhasen, jedoch kürzer als bei Echten Hasen. Die Wurfgröße liegt bei einem bis (selten) fünf, durchschnittlich zwei, Jungtieren. Sie entspricht der von Hasenarten der Gattung Lepus, unterscheidet sich jedoch deutlich von den großen Würfen der Baumwollschwanzkaninchen (Sylvilagus) und der Wildkaninchen (Oryctolagus).[1] Die Geburt findet fast immer nachts statt. Die Jungtiere werden vollständig behaart und mit geschlossenen Augen geboren, die sie nach vier bis acht Tagen öffnen. Sie haben eine Körperlänge von etwa 8 bis 10 Zentimeter mit einem Schwanz von 8 bis 10 Millimetern Länge und einem Gewicht von etwa 25 Gramm. Ihre Rückenfärbung ist mattgrau, die Färbung des Kopfes und der Körperseiten ist gelblich mit einzelnen weißen Bereichen an den Flanken. Der Schwanz ist noch sichtbar und nicht wie bei den ausgewachsenen Tieren von einem Hautlappen bedeckt. Die Füße besitzen kräftige, dunkelbraune Krallen.[1] Die Jungtiere verbringen die ersten beiden Lebenswochen im Bau und werden von der Mutter gestillt. Dabei gibt die Mutter zumeist nur über vier der insgesamt sechs Zitzen Milch. Nach etwa drei Wochen beginnen die Jungtiere mit der Aufnahme fester Nahrung und mit einem Monat sind sie selbstständig, können aber noch eine Zeitlang Milch der Mutter bekommen.[2] Sie verlassen den Bau mit einem Gewicht von etwa 100 Gramm.[1] Die Muttertiere können direkt nach dem letzten Wurf und noch während der Jungenaufzucht wieder trächtig werden. Da mehrere noch stillende Weibchen identifiziert wurden, die zugleich trächtig waren, geht man von einem nachgeburtlichen Eisprung der Weibchen aus, nach dem sie wieder fruchtbar sind.[1]

Innerhalb des Verbreitungsgebietes tritt das Vulkankaninchen sympatrisch mit zwei Arten der Baumwollschwanzkaninchen auf, dem Mexikanischen Baumwollschwanzkaninchen (Sylvilagus cunicularius) und dem Florida-Waldkaninchen (S. floridanus). Dabei kommen die beiden Gattungen in etwa 8 % der Fläche gemeinsam vor, das Vulkankaninchen lebt allerdings vorwiegend in den höheren Lagen.[2]

Ebenso wie die Baumwollschwanzkaninchen stellt das Vulkankaninchen eine wichtige Beute der in der Region lebenden Kojoten (Canis latrans cagottis) und Rotluchse (Lynx rufus escuinapae) dar. Der Anteil an Vulkankaninchen an den Beutetieren beider Arten liegt jedoch niedriger als der der Baumwollschwanzkaninchen, auch unter Berücksichtigung des selteneren Vorkommens werden sie seltener erbeutet. Dies wird vor allem auf ihre geringe Größe und die Aktivität während der Dämmerung statt in der Nacht zurückgeführt.[6] Weitere Beutegreifer, die Vulkankaninchen erbeuten, sind das Langschwanzwiesel (Mustela frenata perotae), die Mexikanische Plateau-Klapperschlange (Crotalus triseriatus) und der Rotschwanzbussard (Buteo jamaicensis costaricensis).[7]

Als Endoparasit wurden der Fadenwurm Paraheligmonella romerolagi[8] aus dem Dünndarm wildlebender und in Gefangenschaft gehaltener Vulkankaninchen[9] sowie Teporingonema cerropeladoensis[10] und Dermatoxys romerolagi als artspezifische Parasiten aus dem Vulkankaninchen isoliert und beschrieben. Daneben wurden mit Trichostrongylus calcaratus, Trichostrongylus tatertaeformis, Trichuris leporis und Dermatoxys veligera weitere Nematoden als Endoparasiten identifiziert, die die Tiere in der Wildnis und im Zoo befallen können.[1] Unter den Bandwürmern konnten Cittotania ctenoides und Multiceps serialis im Darmtrakt der Art nachgewiesen werden,[1] zudem wurde die neue Art Anoplocephaloides romerolagi aus dem Gallengang der Art isoliert und beschrieben.[11] Auch Kokzidien wie Eimeria perforans, Eimeria coecicola und Eimeria stiedae, die eine Kokzidiose der Kaninchen auslösen, wurden in inneren Organen und in Kotpillen der Tiere gefunden.[1]

Unter den Ektoparasiten sind wie bei anderen Kleinsäugern vor allem Flöhe und Zecken relevant. Floh- und Zeckenbefall kommt bei den Tieren das gesamte Jahr vor und ist besonders stark in den warmen und feuchten Sommern, wobei die Zecken sich vor allem im Bereich der Ohren und am Gesicht befinden. Unter den Flöhen wurde Cediopsylla inequalis, Strepsylla mina und andere Strepsylla-Arten nachgewiesen sowie Cediopsylla tepolita und Hoplopsyllus pectinatus neu beschrieben. Die artspezifische Zecke Cheyletiella mexicanus wurde 1979 neu beschrieben, zudem wurden Cheyletiella parasitivorax und Ixodes spinipalpis[12] auf der Art identifiziert. Weitere Ektoparasiten an Vulkankaninchen sind nicht näher benannte Laufmilben (Trombiculidae) und Dasselfliegen (Cuterebridae), deren Larven unter der Haut leben.[1]

Das Vulkankaninchen wird als eigenständige und einzige Art der damit monotypischen Gattung Romerolagus den Hasen (Leporidae) zugeordnet.[13] Die wissenschaftliche Erstbeschreibung der Art erfolgte 1891 durch Fernando Ferrari-Pérez als Lepus diazi aus dem Umland von San Martin Texmelucan vom nordöstlichen Hang des Vulkans Iztaccíhuatl in Puebla, Mexico. Die Art wurde im Rahmen eines Katalogs zur Erfassung der Geographie der Region durch die Comision Geografico Exploradora unter Leitung des Ingenieurs Augustín Diáz unter der Bezeichnung „Conejo del volcán“ als neu beschriebene Art aufgeführt und abgebildet, jedoch nicht detaillierter beschrieben.[14]

1896 beschrieb Clinton Hart Merriam die Gattung Romerolagus und darin die Art Romerolagus nelsoni vom Popocatépetl als nomenklatorischer Typus. Gesammelt wurden die Typen von Edward William Nelson, nach dem er die Art benannte, und Edward Alphonso Goldman.[15] Romerolagus nelsoni wurde im Jahr 1911 durch Gerrit Smith Miller mit Lepus diazi synonymisiert und mit dem heute gültigen Artnamen Romerolagus diazi benannt. Gerrit Smith Miller ordnete die Erstbeschreibung allerdings Diáz zu und argumentierte, dass dieser die Publikation mit der Erstbeschreibung veröffentlicht hat. Gemeinsam mit Ferrari-Pérez untersuchte er weitere Individuen der Art und verglich diese mit den Typen von Merriam, um eine sichere Synonymisierung vornehmen zu können.[16] Erst 1955 wurde von P. Rojas vorgeschlagen, entsprechend den Regeln der Internationalen Regeln für die Zoologische Nomenklatur (ICZN) „(Ferrari-Pérez in Diáz)“ als Erstbeschreiber für Romerolagus diazi anzugeben.[1]

Pfeifhasen (Ochotonidae / Ochotona)

Buschkaninchen (Poelagus marjorita)

Rotkaninchen (Pronolagus)

Streifenkaninchen (Nesolagus)

Vulkankaninchen (Romerolagus diazi)

Wildkaninchen (Oryctolagus cuniculus)

Borstenkaninchen (Caprolagus hispidus)

Buschmannhase (Bunolagus monticularis)

Ryukyu-Kaninchen (Pentalagus furnessi)

Baumwollschwanzkaninchen (Sylvilagus)

Zwergkaninchen (Brachylagus)

Echte Hasen (Lepus)

Fossilbefunde für das Vulkankaninchen und potenzielle Vorfahren liegen nicht vor.[19] Bei Untersuchungen im Verbreitungsgebiet konnten nur die Überreste von Sylvilagus floridiana und Sylvilagus cunicularius identifiziert werden.[1]

Auf der Basis von molekularbiologischen Daten wurde von Conrad A. Matthee et al. 2004 und später von Robinson & Mathee 2005 ein Kladogramm entwickelt, das die phylogenetischen Verwandtschaften der Gattungen innerhalb der Hasen zueinander darstellt. Demnach wird das Vulkankaninchen innerhalb der Hasen einem Taxon bestehend aus den Echten Hasen (Gattung Lepus), den Baumwollschwanzkaninchen (Gattung Sylvilagus), dem Zwergkaninchen, dem Wildkaninchen (Oryctolagus cuniculus), dem Borstenkaninchen (Caprolagus hispidus), dem Buschmannhasen (Bunolagus monticularis) und dem Ryukyu-Kaninchen (Pentalagus furnessi) als basale Art gegenübergestellt. Das Buschkaninchen (Poelagus marjorita), die Rotkaninchen (Pronolagus) und die Streifenkaninchen (Nesolagus) bilden die Schwestergruppe zu den übrigen Hasen.[17] Der Kariotyp ist ursprünglich, über einen Vergleich verschiedener Allozyme wurde eine nähere Verwandtschaft der Art zu der Gattung Sylvilagus als zur Gattung Lepus bestätigt.[2]

Das Vulkankaninchen ist monotypisch, innerhalb der Art werden also neben der Nominatform keine Unterarten unterschieden.[2][1]

Fernando Ferrari-Pérez benannte das Vulkankaninchen nach Augustín Diáz, dem Leiter der geographischen Expedition in Mexiko. Die später von Clinton Hart Merriam erfolgte Gattungsbenennung Romerolagus leitet sich ab vom Namen des mexikanischen Politikers Martín Romero, der Nelson und Goldman bei ihren Arbeiten in Mexiko unterstützte, sowie von der griechischen Benennung des Hasen, „lagos“. Obwohl international in der Regel der englische Name „volcano rabbit“ bzw. im deutschsprachigen Raum „Vulkankaninchen“ gebräuchlich ist, wird die Art im Verbreitungsgebiet in der Regel Zacatuche oder seltener als Teporingo bezeichnet. Der lokale Name Zacatuche stammt aus der Sprache der Azteken und bedeutet „Grashase“, abgeleitet von „zacatl“ für „Gras“ und „tochtli“ für „Hase“. Über die Bedeutung der ebenfalls gebräuchlichen Benennung Teporingo gibt es keine Angaben.[1]

Die Art wird von der International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) aufgrund des sehr kleinen Verbreitungsgebietes und der starken Bestandsrückgänge als bedroht (endangered) eingestuft.[5] Die Hauptbedrohung für die Art ging und geht von der Umwandlung ihres Lebensraums in Felder und Weiden und die damit einhergehende Fragmentierung und Lebensraumverschlechterung durch die Beweidung und die landwirtschaftliche Nutzung der Gebiete aus. Hinzu kommen die Entfernung der Zacatón-Gräser sowie die Brandrodung der Zacatón-Gräser zur Vorbereitung neuer Nutzflächen oder zur Verbesserung der Weidebedingungen für Rinder und Schafe sowie die Entnahme der Gräser für die häusliche Nutzung.[4] Auch die Nähe zu Mexiko-Stadt und die Ausbreitung der Vorstädte in die Verbreitungsgebiete der Art führen zu Lebensraumverlusten und Bestandsrückgängen. Eine weitere Fragmentierung wird durch den Bau von Straßen und Highways verursacht. Nach Schätzungen gingen die verfügbaren Habitate entsprechend um 15 bis 20 % über die letzten drei Generationen der Kaninchen zurück.[5] Bestandsschätzungen nehmen eine Gesamtpopulation von etwa 2.500 bis 12.000 Tieren an.[2]

Ihr Verbreitungsgebiet ist heute in wenige, nach konkreteren Angaben 16, kleine Flecken zerstückelt, in denen die Tiere genetisch voneinander isoliert sind. Diese fragmentierte Verbreitung erhöht das Risiko der lokalen Ausrottung einzelner Populationen und damit verbunden den weiteren Rückgang der Bestände. Bei einer Landschaftsmodellierung im Jahr 2018 wurde eine Gesamtfläche von 75,44 km2 identifiziert, die potenziell als Lebensraum für die Art verfügbar ist, aufgeteilt in 957 Einzelflächen von in der Regel etwa 2500 m2 Größe. Dabei wurde vor allem die Region am Pelado und am Tlaloc als Rückzugsgebiet für die Tiere bestimmt, die bereits jetzt als Kernlebensraum für die Art gilt.[20] Obwohl die Art in Mexiko geschützt und die Bejagung verboten ist, wird sie von der einheimischen Bevölkerung manchmal immer noch als Fleischquelle bejagt, Jungtiere werden zudem häufig von Hunden getötet.[2][5]

Das Vulkankaninchen gehörte zu den ersten Arten der Hasenartigen, die in den Fokus des Artenschutzes gerückt sind. Gemeinsam mit dem Borstenkaninchen (Caprolagus hispidus), dem Sumatra-Kaninchen (Nesolagus netscheri) und dem Ryukyu-Kaninchen (Pentalagus furnessi) war es bereits 1972 und 1978 in den IUCN Reda Data Books vertreten und als gefährdete Tierart gelistet.[21] Es ist auf dem Appendix I des Washingtoner Artenschutzübereinkommen (CITES) von 1973 gelistet und somit streng geschützt. Der Import in die und der Handel in den Vereinigten Staaten ist ebenfalls verboten.[1] Es kommt im Parque Nacional Izta-Popo-Zoquiapan vor, ist jedoch auch hier nicht ausreichend vor Brandrodungen und Bejagung geschützt und die heimische Bevölkerung ist über den besonderen Schutz der Tiere nur wenig aufgeklärt. Zum Schutz der Bestände wurden Nachzuchtprogramme in Gefangenschaft gestartet, vor allem im Chapultepec-Zoo (Zoológico de Chapultepec) in Mexiko-Stadt, dem Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust sowie in Kawasaki in Japan und im Zoo Antwerpen in Belgien. Die Programme waren und sind teilweise erfolgreich, allerdings ist die Mortalität der Jungtiere in Gefangenschaft sehr hoch.[5]

Das Vulkankaninchen (Romerolagus diazi) ist eine Säugetierart aus der Familie der Hasen (Leporidae). Es gehört zu den kleinsten Arten der Familie und kommt endemisch ausschließlich in der Gebirgsregion im zentralen Teil Mexikos vor und wird dort als Zacatuche oder Teporingo bezeichnet. Dort lebt es vorwiegend im Gebiet der Vulkane Popocatépetl und Iztaccíhuatl, worauf auch sein deutscher und englischer Trivialname Bezug nimmt. Die Tiere sind einheitlich gelbbraun bis schwarz gefärbt, sie haben vergleichsweise kurze Ohren und der Schwanz ist äußerlich nicht sichtbar. Sie leben im Unterwuchs von Kiefern- und Erlenwäldern in Höhen von 2800 bis 4250 Metern, wobei die Lebensräume stark von dicht wachsenden Büschelgräsern („zacatón“) und von steinigem bis felsigem Untergrund geprägt sind.

Die Tiere bilden Gruppen von zwei bis fünf Individuen und ernähren sich von Gräsern und Kräutern. Sie graben Baue in den Waldboden oder nutzen die verlassenen Höhlen anderer Tierarten. Vorwiegend zwischen April und September werden durchschnittlich zwei Jungtiere geboren. Die Art steht unter strengem Schutz und wird aufgrund des sehr kleinen Verbreitungsgebietes als bedroht eingestuft.

Il-fenek tal-vulkan (Romerolagus diazi), magħruf ukoll bħala teporingo jew conejo zacatuche huwa mammiferu plaċentat erbivoru ċkejken tal-familja Leporidae li jgħix qalb il-muntanji vulkaniċi tal-Messiku. Dan huwa it-tieni l-iżgħar fenek fid-dinja u fenek tal-vulkan adult jiżen bejn 390 u 600 gramma, ftit akbar biss mil-fenek pigmew u għandu par widnejn żgħar ġejjin għat-tond, erba' saqajn qosra u pil qasir u oħxon.

Il-fenek tal-vulkan jgħix f'bejtiet taħt l-art fi gruppi minn 2 sa 5 u xi ħaġa rari fost il-fniek f'każ ta' periklu bħala komunikazzjoni, juża' ħsejjes bħal twerżieqa irqieqa u għolja minflok it-tisbit tas-saqajn mal-art li jużaw ħafna speċi ta' fniek oħra. Dan huwa fenek notturn u għalkemm attiv matul il-lejl kollu, il-quċċata tal-attività tiegħu tkun fi tlugħ u nżul ix-xemx.

Il-popolazzjoni fis-salvaġġ tal-fenek tal-vulkan fl-1969 kienet niżlet drastikament għal mhux aktar minn 1,200 fenek. Illum il-ġurnata bħala sigurtà kontra l-possibilità ta' estinzjoni ta' dan il-fenek fis-salvaġġ, jeżistu kolonji ta' ripproduzzjoni f'Jersey Zoo, fir-Renju Unit u f'Chapultepec Zoo, fil-Belt tal-Messiku (Olney & Ellis, 1993).

Il-fenek tal-vulkan huwa speċi endemika tal-Messiku u jgħix fuq il-ġnub tal-vulkani Iztaccihuatl, Pelado, Popocatépetl u Tlaloc f'għoli bejn 2,800 u 4250 metru ġo foresti tal-pinu fejn jikber ħafna ħaxix taħt is-siġar u f'artijiet b'ħagar vulkaniku li jissejħu assi transversali neo-vulkaniċi.

Il-fenek tal-vulkan (Romerolagus diazi), magħruf ukoll bħala teporingo jew conejo zacatuche huwa mammiferu plaċentat erbivoru ċkejken tal-familja Leporidae li jgħix qalb il-muntanji vulkaniċi tal-Messiku. Dan huwa it-tieni l-iżgħar fenek fid-dinja u fenek tal-vulkan adult jiżen bejn 390 u 600 gramma, ftit akbar biss mil-fenek pigmew u għandu par widnejn żgħar ġejjin għat-tond, erba' saqajn qosra u pil qasir u oħxon.

Il-fenek tal-vulkan jgħix f'bejtiet taħt l-art fi gruppi minn 2 sa 5 u xi ħaġa rari fost il-fniek f'każ ta' periklu bħala komunikazzjoni, juża' ħsejjes bħal twerżieqa irqieqa u għolja minflok it-tisbit tas-saqajn mal-art li jużaw ħafna speċi ta' fniek oħra. Dan huwa fenek notturn u għalkemm attiv matul il-lejl kollu, il-quċċata tal-attività tiegħu tkun fi tlugħ u nżul ix-xemx.

Il-popolazzjoni fis-salvaġġ tal-fenek tal-vulkan fl-1969 kienet niżlet drastikament għal mhux aktar minn 1,200 fenek. Illum il-ġurnata bħala sigurtà kontra l-possibilità ta' estinzjoni ta' dan il-fenek fis-salvaġġ, jeżistu kolonji ta' ripproduzzjoni f'Jersey Zoo, fir-Renju Unit u f'Chapultepec Zoo, fil-Belt tal-Messiku (Olney & Ellis, 1993).

The volcano rabbit (Romerolagus diazi), also known as teporingo or zacatuche, is a small rabbit that resides in the mountains of Mexico.[4] It is the world's second-smallest rabbit, second only to the pygmy rabbit. It has small rounded ears, short legs, and short, thick fur and weighs approximately 390–600 g (0.86–1.3 lb). It has a life span of 7 to 9 years. The volcano rabbit lives in groups of 2 to 5 animals in burrows (underground nests) and runways among grass tussocks. The burrows can be as long as 5 m and as deep as 40 cm. There are usually 2 to 3 young per litter, born in the burrows. In semi-captivity, however, they do not make burrows and the young are born in nests made in the grass tussocks.[5]

Unlike many species of rabbits (and similar to pikas), the volcano rabbit emits very high-pitched sounds instead of thumping its feet on the ground to warn other rabbits of danger. It is crepuscular and is highly active during twilight, dawn and all times in between. Populations have been estimated to have approximately 150–200 colonies with a total population of 1,200 individuals over their entire range.[6]

The volcano rabbit’s adult weight goes up to 500 g.[7] It has short, dense fur that ranges in color from brown to black.[8] The rabbit is a gnawing animal that is distinguished from rodents by its two pairs specialized of upper incisors that are designed for gnawing.[7] Their body size and hindlimb development demonstrates how they need extra grass-cover for evasion from predators.[4][7] Their speediness and their hind limb development relative to their body size correlate to their necessity for evasion action.[7] They are relatively slow and vulnerable in open habitats; therefore they take comfort in high, covered areas.[7] They also have difficulty breeding in small enclosures.[7] Volcano rabbits have a very narrow gestational period: In one study, all females gave birth between 39 and 41 days after coitus.[9] They create runways similar to those made by microtine rodents to navigate their habitat.[7] The burrows consist of dense grass clumps, with a length of 5 m and depth of 40 cm.[7] Their small size relates to their selective dietary habits.[7] As of 1987, they were used in one piece of scientific research.[10]

Volcano rabbits are an endangered species endemic to Mexico.[11] Specifically, the rabbit is native to four volcanoes just south and East of Mexico City, the largest of these volcanic regions is within the Izta-Popo National Park, other areas include the Chichinautzin and Pelado volcanos.[4][12][6] The range of the volcano rabbit has been fragmented into 16 individual patches by human disturbance. Vegetation within these patches is dominated by native grasslands and include Nearctic and Neotropical varieties. Elevation of these patches is between 2900 and 3660 meters above sea level.[11] The soil consists mostly of Andosol and Lithosol. The local climate is temperate, subhumid, and has a mean annual temperature of 11 °C. Annual rainfall averages at about 1000 millimeters. In the patches that are the most heavily populated with volcano rabbits, the plants Festuca tolucensis and Pinus hartwegii are most abundant.[11] Volcano rabbits show strong preferences for habitat types that are categorized as open pine forests, open pine woodland, and mixed alder pine forest. Human activity in the area has had a great impact upon the preferred habitat of the volcano rabbit.[11] Humans have fragmented the rabbits' habitat by constructing highways, farming, afforestation (i.e. planting trees where they don't belong), and lack of sound fire and grazing practices. Ecological fragmentation has been caused by environmental discontinuity.[4][12][13]

Volcano rabbits are commonly found at higher altitudes.[7] Almost 71% of volcano rabbits are found in pine forests, alder forests, and grasslands.[7] Volcano rabbits are more abundant near tall, dense herbs and thick vegetation, and are adversely affected by anthropogenic environmental disturbances like logging and burning.[7] A study on the effects of climate change upon volcano rabbit metapopulations concluded that fluctuations in climate most affected rabbits on the edge of their habitable range.[14] The volcano rabbit's range encompasses a maximum of 280 km2 of grasslands in elevated areas in the Trans-Mexican Neovolcanic Belt.[7]

The last unconfirmed sighting of the species at Nevado de Toluca (where no permanent colony has been historically documented) occurred in August 2003 when supposedly one volcano rabbit was observed. Since 1987, however, research conducted by Hoth et al., in relation to the distribution of the Volcano Rabbit already found no records of this species in the Nevado de Toluca, including the site where Tikul Álvarez (IPN) collected a specimen in 1975 (Nevado de Toluca, 4 km S, 2 km W Raíces, 3350 masl).[4] Notwithstanding, although no permanent colony has been documented in Nevado de Toluca, the volcano rabbit was declared "extinct" within this portion of its range in 2018;[15] populations exist elsewhere within the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt and in captivity.[4][5][16] Due to the above, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (Red Data Book, IUCN 2019), no longer mentions the Nevado de Toluca as a current or potential site for the distribution of this species.[17]

The IUCN/SSC Lagomorph Specialist Group has created an action plan for this rabbit that focuses upon the need to manage the burning and overgrazing of its Zacatón habitats and to enforce laws prohibiting its hunting, capture, and sale.[7] Studies about the volcano rabbit's geographical range, role in its habitat, population dynamics, and evolutionary history have been recommended.[7] In addition, habitat restoration and the establishment of Zacatón corridors to link core areas of habitat are needed.

The volcano rabbit feeds primarily on grasses such as Festuca amplissima, Muhlenbergia macroura, Stipa ichu, and Eryngium rosei.[18] The rabbits also use these plants as cover to hide from predators. M. macroura was found to be in 89% of pellets of the volcano rabbits, suggesting that this is the base of their diet, but it does not actually provide the necessary energy and protein needs of the rabbits. Supplementing their diet with 15 other forms of plant life, volcano rabbits can get their required nutrition. Other plant species that also are responsible for supporting the volcano rabbit are the Muhlenbergia quadidentata, the Pinus hartwegii, F. tolucensis, P. hartwegeii.[18] Volcano rabbits also consume leaves, foliage, and flowers indiscriminately under poor conditions, as habitat loss has eliminated much of their food sources.[18] In fact, protein acquisition is the primary limiting factor on the size of the populations of each of the four volcanoes on which the species is located. Studies show that many individuals of the population suffer from serious weight loss and starvation.[18]

Seasonal changes also affect the diet of the volcano rabbit greatly. The grasses it normally consumes are abundant during wet seasons. During the dry season, the volcano rabbit feasts on shrubs and small trees, as well as other woody plants. During the winter plants, these woody plants make up most of their diet, as well as the primary building material for their nests.[18]

Numerous studies conducted during the 1980s and 1990s agreed that the habitat of the volcano rabbit was shrinking due to a combination of natural and anthropogenic causes.[19] There is evidence that its range has shrunk significantly during the last 18,000 years due to a 5–6 °C increase in the prevailing temperature, and its distribution is now divided into 16 patches.[19] The fragmentation of the volcano rabbit's distribution has resulted from a long-term warming trend that has driven it to progressively higher altitudes and the relatively recent construction of highways that dissect its habitat.[19]

Declines in the R. diazi population have been occurring due a number of changes in vegetation, climate, and, thus, elevation. The volcano rabbit is extremely vulnerable to the effects of climate change and other anthropogenic intrusions because of its extremely limited range and specialized diet.[19] Patches of vegetation that R. diazi uses for survival are becoming fragmented, isolated and smaller, rendering the environment more open and therefore less suitable for its survival. Because the volcano rabbit inhabits the area surrounding Mexico City, Mexico's most populous region, it has suffered a very high rate of habitat destruction.[19]

The cottontail rabbit, Sylvilagus, is expanding into the volcano rabbit’s niche, but there is “no evidence that [volcano rabbits'] habitat selection is a response to competitive exclusion." The volcano rabbit has been severely pressured by human intrusion into its habitat. Anthropogenic disturbance enables other rabbit species to flourish in grasslands, increasing competition with the volcano rabbit.[7]

Volcano rabbits have been bred in captivity,[5] but there is evidence that the species loses a significant amount of genetic diversity when it reproduces in such conditions. A comparative study done on wild and captive volcano rabbits found that the latter lost a substantial amount of DNA loci, and some specimens lost 88% of their genetic variability. There was, however, one locus whose variability was higher than that of the wild population.[20]

Threats to R. diazi, or the volcano rabbit, include logging, harvesting of grasses, livestock grazing, habitat destruction, urban expansion, highway construction and too frequent forest fires.[4] More recent threats include unsound management policies of its habitat in National Parks and outside, mainly by afforestation (planting trees in grasslands where they do not belong). [12] These threats have resulted in a loss of 15–20% of the volcano rabbit’s habitat during the last three generations. They have also resulted in ecological displacement and genetic isolation of R. diazi. Hunting is another threat to the volcano rabbit, despite the fact that R. diazi is listed under Appendix 1 of CITES[21] and it is illegal to hunt R. diazi under Mexican law. However, many are unaware that R. diazi is protected and officials do not adequately enforce its protection. Hunting, livestock grazing, and fires can even harm R. diazi within national parks that are protected such as Izta-Popo and Zoquiapan National Parks. In terms of conservation efforts, various captive breeding programs have been established with relative success, but infant mortality in captivity is high.[8] Actions toward conservation should be focused on the enforcement of laws which forbid hunting and trading of the volcano rabbit. Furthermore, efforts must be put toward habitat management, specifically the control of forest fires and livestock overgrazing of grasses. Lastly, it would be beneficial to enact education programs regarding R. diazi and the various threats that face it. The public should also be educated about the volcano rabbit’s protected status, as many are unaware that it is illegal to hunt R. diazi.

The volcano rabbit (Romerolagus diazi), also known as teporingo or zacatuche, is a small rabbit that resides in the mountains of Mexico. It is the world's second-smallest rabbit, second only to the pygmy rabbit. It has small rounded ears, short legs, and short, thick fur and weighs approximately 390–600 g (0.86–1.3 lb). It has a life span of 7 to 9 years. The volcano rabbit lives in groups of 2 to 5 animals in burrows (underground nests) and runways among grass tussocks. The burrows can be as long as 5 m and as deep as 40 cm. There are usually 2 to 3 young per litter, born in the burrows. In semi-captivity, however, they do not make burrows and the young are born in nests made in the grass tussocks.

Unlike many species of rabbits (and similar to pikas), the volcano rabbit emits very high-pitched sounds instead of thumping its feet on the ground to warn other rabbits of danger. It is crepuscular and is highly active during twilight, dawn and all times in between. Populations have been estimated to have approximately 150–200 colonies with a total population of 1,200 individuals over their entire range.

La vulkankuniklo konata ankaŭ kiel teporingo aŭ zakatuĉe (Romerolagus diazi) estas malgranda kuniklo kiu loĝas en la montoj de Meksiko. Ĝi estas la dua plej malgranda kuniklo de la mondo, dua nur post la nana kuniklo. Ĝi havas malgrandajn rondoformajn orelojn, mallongajn krurojn, kaj mallongan, dikan felon kaj pezas proksimume 390–600 g. Ĝi havas vivodaŭron de 7 al 9 jaroj. La vulkankuniklo loĝas en grupoj de 2 al 5 animaloj en truoj (subgrundaj nestoj) kaj moviĝas inter herbotufoj. La trunestoj povas esti tiom longaj kiom ĝis 5 m kaj tiom profundaj kiom ĝis 40 cm. Estas kutime 2 al 3 idoj por idaro, naskiĝintaj en la trunesto.

Malkiel ĉe multaj specioj de kunikloj (kaj simile al Ochotona), vulkankunikloj elsendas tre altatonajn sonojn anstataŭ piedfrapi sur la grundo por averti aliajn kuniklojn pri danĝero. Ili estas krepuskemaj kaj estas tre aktivaj dum la sunsubiro, sunapero kaj aliaj epokoj intermeze. Populacioj estis ĉirkaŭkalkulitaj je 150–200 kolonioj kun totala populacio de 1.200 individuoj en la tuta teritorio.[1]

La vulkankuniklo konata ankaŭ kiel teporingo aŭ zakatuĉe (Romerolagus diazi) estas malgranda kuniklo kiu loĝas en la montoj de Meksiko. Ĝi estas la dua plej malgranda kuniklo de la mondo, dua nur post la nana kuniklo. Ĝi havas malgrandajn rondoformajn orelojn, mallongajn krurojn, kaj mallongan, dikan felon kaj pezas proksimume 390–600 g. Ĝi havas vivodaŭron de 7 al 9 jaroj. La vulkankuniklo loĝas en grupoj de 2 al 5 animaloj en truoj (subgrundaj nestoj) kaj moviĝas inter herbotufoj. La trunestoj povas esti tiom longaj kiom ĝis 5 m kaj tiom profundaj kiom ĝis 40 cm. Estas kutime 2 al 3 idoj por idaro, naskiĝintaj en la trunesto.

Malkiel ĉe multaj specioj de kunikloj (kaj simile al Ochotona), vulkankunikloj elsendas tre altatonajn sonojn anstataŭ piedfrapi sur la grundo por averti aliajn kuniklojn pri danĝero. Ili estas krepuskemaj kaj estas tre aktivaj dum la sunsubiro, sunapero kaj aliaj epokoj intermeze. Populacioj estis ĉirkaŭkalkulitaj je 150–200 kolonioj kun totala populacio de 1.200 individuoj en la tuta teritorio.

El conejo de los volcanes (Romerolagus diazi), también conocido como teporingo, zacatuche,[2] tepolito, tepol o burrito,[3] es una especie de mamífero lagomorfo de la familia Leporidae, la única del género monotípico Romerolagus.[2] Es endémica de las montañas del centro de México. Vive en bosques y zacatonales por arriba de los 2800 m. Está en Peligro de Extinción debido principalmente a la pérdida de hábitat y fragmentación.

La palabra zacatuche se deriva del náhuatl y significa "conejo de los zacatonales", de zacatl, zacate, y tochtli, conejo, lo cual concuerda con su hábitat natural de zacatonales o pastos altos. El origen y significado de la palabra teporingo no son tan claros, pero se cree que tiene relación con la palabra tepolito, que significa "el de las rocas", lo cual podría referirse al hábitat de este pequeño conejo.

En cuanto al nombre científico, el género Romerolagus se debe al embajador de México en Washington Matías Romero, en agradecimiento a las facilidades que este otorgó a los colectores estadounidenses E. W. Nelson y E. A. Goldman para trabajar en México. Por otro lado, el nombre específico se adoptó en honor de Agustín Díaz,director de la Comisión Geográfico Exploradora a fines del siglo XIX.0

Vive en la parte central del Eje Neovolcánico de México, en los volcanes Pelado, Tláloc, Popocatépetl, e Iztaccíhuatl[4][5] entre los 2800 y 4200 metros de altura, en pastizales nativos alpinos y subalpinos —conocidos también como zacatonales— donde abundan los bosques abiertos de pinos con una cubierta vegetal densa de pastizales.

Mide alrededor de 30 cm de largo, cola vestigial de unos 20 o 30 mm y orejas de 40 mm, pequeñas en comparación con otros conejos. Su peso medio es de 600 g. Su pelo, corto y uniforme, es de color amarillo y negro, salvo en la superficie dorsal de las patas y algunas zonas de la cara, que son de color ocre, y un triángulo de pelo rubio en la nuca.

Si bien es posible encontrarlos activos en el día o la noche, sus horas de máxima actividad se dan por las mañanas y bien entrada la tarde. Es probable que entre las 10 y las 14 horas estén fuera de sus refugios.[6] Viven en madrigueras, escondidas entre la pastizales nativos, en grupos de 2 a 5 individuos. No permiten la entrada de individuos extraños en la conejera y, al igual que las pikas, usan llamadas estridentes y agudas para alertar a los demás miembros de la madriguera de un posible peligro. Las madrigueras pueden llegar a medir 5 metros de largo y alcanzar 40 cm bajo la superficie del suelo. En semi-cautiverio, sin embargo, no usan las madrigueras para parir a sus críos, sino que forman nidos en los pastizales,[7] –observado también en condiciones silvestres. Se mueven habitualmente entre áreas con zacate, aunque salen de dichas áreas en busca de alimento hacia cultivos cercanos.[6]

Sus principales depredadores son la comadreja, las musarañas, el lince, el coyote, el zorro gris, la víbora de cascabel, el cacomixtle norteño, así como perros y gatos domésticos y el ser humano.[3]

El conejo zacatuche cría durante todo el año, aunque son más activos sexualmente durante el verano. Los nidos, pequeñas depresiones escondidas en los pastizales y recubiertas con sus pelos y trozos de plantas, solo son construidos de abril a septiembre. El periodo de gestación dura 39 días y pueden tener hasta 3 crías por camada. Los recién nacidos nacen con pelo pero con los ojos cerrados, y no podrán moverse ni alimentarse por sí mismos hasta pasadas 3 semanas, aunque en el nido sólo estarán hasta pasados 14 días.[8]

Es una especie endémica mexicana considerada en peligro de extinción por la UICN. Entre las principales causas que ponen en peligro a la especie se encuentran el avance de la agricultura y la "aforestación" (siembra de árboles donde no corresponden) —aun en áreas protegidas—, mal manejo del fuego y del pastoreo, así como avance de la urbanización, todo ello causando la fragmentación de su hábitat de pastizales nativos y por lo tanto la continua disminución de su área de distribución; y el crecimiento de la población humana cercana a su hábitat.[9] [10]

Ya desde 1987 investigaciones realizadas por Hoth, et al., en relación a la distribución del teporingo no encontraron registros de esta especie en el Nevado de Toluca, incluyendo el sitio donde Tikul Álvarez (IPN) colectó un espécimen en 1975 (Nevado de Toluca, 4 km S, 2 km W Raíces, 3350 msnm; ver Ceballos, et al., 1989 y CONANP, 2018). A pesar de que históricamente no se ha reportado de manera científica la existencia de una colonia permanente en el Nevado de Toluca, recientemente, según la Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México (UAEM), la especie se encuentra extinta en el Nevado de Toluca.[11] No obstante, la Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (SEMARNAT), la Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad (CONABIO) y la Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas (CONANP),[12] ante diversos medios que informaron en septiembre de 2018 que la especie estaba extinta basándose en el informe de la UAEM,[13] señalaron que el teporingo no puede declararse extinto, ya que se requieren más de cincuenta años sin avistamientos para hacerlo formalmente;[14] asimismo, tampoco puede ser declarada extinta en el Nevado de Toluca, puesto que ni siquiera se ha confirmado su presencia en esta zona.[15] Debido a lo anterior, el Libro Rojo de la Unión Internacional para la Conservación de la Naturaleza (UICN, 2019), ya no menciona al Nevado de Toluca como sitio actual ni potencial para la distribución de esta especie.[16]

El conejo de los volcanes (Romerolagus diazi), también conocido como teporingo, zacatuche, tepolito, tepol o burrito, es una especie de mamífero lagomorfo de la familia Leporidae, la única del género monotípico Romerolagus. Es endémica de las montañas del centro de México. Vive en bosques y zacatonales por arriba de los 2800 m. Está en Peligro de Extinción debido principalmente a la pérdida de hábitat y fragmentación.

La palabra zacatuche se deriva del náhuatl y significa "conejo de los zacatonales", de zacatl, zacate, y tochtli, conejo, lo cual concuerda con su hábitat natural de zacatonales o pastos altos. El origen y significado de la palabra teporingo no son tan claros, pero se cree que tiene relación con la palabra tepolito, que significa "el de las rocas", lo cual podría referirse al hábitat de este pequeño conejo.

En cuanto al nombre científico, el género Romerolagus se debe al embajador de México en Washington Matías Romero, en agradecimiento a las facilidades que este otorgó a los colectores estadounidenses E. W. Nelson y E. A. Goldman para trabajar en México. Por otro lado, el nombre específico se adoptó en honor de Agustín Díaz,director de la Comisión Geográfico Exploradora a fines del siglo XIX.0

Sumendi untxia, teporingoa edo zakatutxea (Romerolagus diazi), untxi espeziea da, Romerolagus genero monotipikoko espezie bakarra izanik. Mexikoko mendietan bizi da. Untxi pigmeoaren ostean untxien artean txikiena da. Belarri txiki biribilduak ditu, hanka motzak eta ile sendoa. 2 eta 5 animalietako taldetan bizi dira. Beste untxiek ez bezala frekuentzia altuko soinuak egiten ditu beste untxiak arriskuez ohartarazteko. Gautarra da. 390-600 gramo bitarteko pisua du. 1969an 1000 eta 1200 artean zeuden bakarrik.

Sumendi untxia, teporingoa edo zakatutxea (Romerolagus diazi), untxi espeziea da, Romerolagus genero monotipikoko espezie bakarra izanik. Mexikoko mendietan bizi da. Untxi pigmeoaren ostean untxien artean txikiena da. Belarri txiki biribilduak ditu, hanka motzak eta ile sendoa. 2 eta 5 animalietako taldetan bizi dira. Beste untxiek ez bezala frekuentzia altuko soinuak egiten ditu beste untxiak arriskuez ohartarazteko. Gautarra da. 390-600 gramo bitarteko pisua du. 1969an 1000 eta 1200 artean zeuden bakarrik.

Tulivuorikaniini[2] (Romerolagus diazi) on pienikokoinen jäniseläin, joka elää Meksikon vuorilla. Se on maailman toiseksi pienin jänis pikkukaniinin jälkeen. Tulivuorikaniini poikkeaa rakenteeltaan ja muodoltaan huomattavasti kaikista muista jäniksistä ja sen uskotaan erkaantuneen näistä evolutiivisesti jo miljoonia vuosia sitten. Tulivuorikaniinilla ei ole lähisukulaisia ja se on Romerolagus-suvun ainoa laji. [3]

Tulivuorikaniinilla on pienet pyöreät korvat, lyhyet jalat ja lyhyt, tiheä turkki. Tulivuorikaniini on 27–34 cm pitkä ja painaa 390–600 grammaa. Korvat ovat 4-5 cm ja häntä puuttuu (on niin lyhyt, ettei erotu eläintä päällisin puolin tarkastellessa). Tulivuorikaniini elää 2–5 eläimen ryhmissä, joissa on tyypillisesti vain yksi uros. Ryhmän hierarkian ylin jäsen on aina naaras. Lisääntymistä tapahtuu ympäri vuoden, mutta eniten lämpiminä ja kosteina kesäkuukausina. Pesät ovat koloissa, joita tulivuorikaniini ei yleensä kaiva itse, vaan se käyttää amerikanmäyrän, kalliosiiselin, yhdeksänvyöyötiäisen ja sierramadrentaskurotan vanhoja koloja. Tulivuorikaniinit kantavat poikasiaan 5–6 viikkoa ja saavat kerrallaan 1–4 poikasta.[4] Ääniä tulivuorikaniinit käyttävät usein ja ainakin viisi erilaista ääntelyä on erotettu, joista selkein on vaarasta varoittava terävä vihellys.

Samassa ympäristössä tulivuorikaniinin kanssa tavataan kahta muutakin jänistä; meksikonkaniini ja pumpulihäntäkaniini, mutta tulivuorikaniinit ovat näitä molempia pienempiä, tummempia ja lyhytkorvaisempia. [3]

Tulivuorikaniinia tavataan Keski-Meksikon tulivuorivyöhykkeellä. Sen levinneisyysalue on pienentynyt historiallisena aikana ja on enää hyvin pieni, arviolta alle 400 km². Nykyisellään lajia tavataan Morelosin, Pueblan ja Distrito Federalin osavaltioissa, Pelado-, Tlalloc-, Popocatépetl- ja Ixtaccíhuatl-vuorten rinteillä. Alimmillaan lajia tavataan 2 800 ja ylimmillään 4 250 metrin korkeudella merenpinnasta. Lajia tavataan etenkin mäntymetsissä ja se tuntuu olevan erityisen riippuvainen pohjakerroksen tuppaina kasvavasta zacatón-heinikosta, joka muodostuu Muhlenbergia-, Festuca- ja Stipa-sukujen heinistä, ja joka on jopa 1,5 m korkeaa. Heinät ovat samalla kaniinien tärkein ravinnonlähde. Zacatón-heinikon ylläpito on lajin suojelutyön kannalta keskeistä. Laji on suojeltu, mutta tieto tästä ei ole levinnyt kaikkien paikallisten keskuuteen.

Yhteensä tulivuorikaniineja on maapallolla muutamia tuhansia. 1964 niitä arvioitiin olevan 1 000 – 1 200 yksilöä ja 1980- ja 1990-lukujen laskennoissa (suoritettiin ratsain ja laskettiin papanakasoja) määräksi arvioitiin noin 2 500, mutta arvioiden luottamusväli on suuri. [3]

Tulivuorikaniini (Romerolagus diazi) on pienikokoinen jäniseläin, joka elää Meksikon vuorilla. Se on maailman toiseksi pienin jänis pikkukaniinin jälkeen. Tulivuorikaniini poikkeaa rakenteeltaan ja muodoltaan huomattavasti kaikista muista jäniksistä ja sen uskotaan erkaantuneen näistä evolutiivisesti jo miljoonia vuosia sitten. Tulivuorikaniinilla ei ole lähisukulaisia ja se on Romerolagus-suvun ainoa laji.

Le Lapin des volcans[1] ou Lapin de Diaz[2]. (Romerolagus diazi) est une espèce de petit lapin vivant principalement dans les montagnes du centre du Mexique. Là-bas, il est connu sous le nom de « Zacatuche » ou « Teporingo ». C'est l'unique espèce du genre Romerolagus.

Romerolagus diazi a un pelage brun foncé uniforme sur le dos et gris brunâtre sur le ventre ; sa queue est pratiquement invisible à cause de sa petite taille (23 à 32 cm pour une masse d'environ 500 g), ses pattes et ses membres sont courts, ses oreilles sont petites et arrondies.

Ce mammifère peut vivre 5 à 10 ans.

Cette espèce vit dans la vallée de Mexico au Mexique.

Le Lapin des volcans ou Lapin de Diaz. (Romerolagus diazi) est une espèce de petit lapin vivant principalement dans les montagnes du centre du Mexique. Là-bas, il est connu sous le nom de « Zacatuche » ou « Teporingo ». C'est l'unique espèce du genre Romerolagus.

Vulkanski zec (lat. Romerolagus), monotipski rod zečeva, jedan od najrjeđih predstavnika reda Lagomorpha. Živi kao endem jedino u Meksiku[1] na 16 izoliranih mjesta na padinama vulkana El Pelado[2], Monte Tláloc, Popocatépetl i Iztaccíhuatl, i to na visinama od 2800 do 4500 m.

To su prilično maleni sisavci, težine do 1,3 kg, što ih čini drugim po redu najmanjim zečevima na svijetu. Biljojedi su koji se hrane travom na svojim staništima, kao i korom drveta. Od grabežljivaca se štite tako da dan provode u skloništima, u podzemnim tunelima, a van izlaze pred večer i rano ujutro. Žive u skupinama od dvije do pet jedinki

Ove životinje su opremljene s dva gornja sjekutića posebno dizajnirana za glodanje, što je osobina koja ih razlikuje od glodavaca. Uši su im malene, a rep gotovo neprimjetan.[3]

Njegov lokalni naziv "zacatuche", izveden iz astečkog "zacatochtle".[4]

Vulkanski zec (lat. Romerolagus), monotipski rod zečeva, jedan od najrjeđih predstavnika reda Lagomorpha. Živi kao endem jedino u Meksiku na 16 izoliranih mjesta na padinama vulkana El Pelado, Monte Tláloc, Popocatépetl i Iztaccíhuatl, i to na visinama od 2800 do 4500 m.

To su prilično maleni sisavci, težine do 1,3 kg, što ih čini drugim po redu najmanjim zečevima na svijetu. Biljojedi su koji se hrane travom na svojim staništima, kao i korom drveta. Od grabežljivaca se štite tako da dan provode u skloništima, u podzemnim tunelima, a van izlaze pred večer i rano ujutro. Žive u skupinama od dvije do pet jedinki

Ove životinje su opremljene s dva gornja sjekutića posebno dizajnirana za glodanje, što je osobina koja ih razlikuje od glodavaca. Uši su im malene, a rep gotovo neprimjetan.

Njegov lokalni naziv "zacatuche", izveden iz astečkog "zacatochtle".

Il coniglio del vulcano (Romerolagus diazi Ferrari-Pérez, 1893) è un mammifero della famiglia dei Leporidi. È l'unica specie del genere Romerolagus Merriam, 1896.

Il coniglio del vulcano è lungo 27–31,5 cm, le orecchie sono lunghe 4–4,4 cm. Pesa 385–600 g. È forse il coniglio più piccolo del mondo, ha un naso corto e ispido, orecchie piccole, gambe corte e una coda praticamente inesistente. Il suo folto pelo color marrone scuro o nero presenta striature gialle nelle parti superiori del corpo.

Il coniglio del vulcano vive in foreste aperte di pini e in foreste di ontani con fitto sottobosco, ad altitudini di 2800-4250 m. La maggior parte di queste aree presenta siccità invernale, ma copiose precipitazioni estive. La specie è endemica del Messico centrale (lì chiamata Zacatuche o Teporingo[3]) e si trova soltanto sulle pendici di quattro vulcani: Popocatépetl e Iztaccíhuatl nella Sierra Nevada, El Pelado e Tlaloc nella Sierra Chichinautzin. È stato importato dagli inglesi in Sudafrica.

Questa specie principalmente notturna è più attiva prima dell'alba o dopo il tramonto, e si muove attraverso sentieri ben mantenuti nel sottobosco. Vive in gruppi da due a cinque esemplari in zone erbose chiamate zacaton. A volte utilizza tane sotterranee, ma più di frequente si nasconde nell'erba.

Questo coniglietto poco noto è recentemente scomparso da alcune aree a causa della caccia e della distruzione del suo habitat a causa degli incendi e dell'impoverimento dei terreni[2]. Si stima che la popolazione attuale sia di circa 6500 esemplari, e pertanto la specie, in base ai criteri della IUCN Red List, è considerata in pericolo di estinzione.

La Zoological Society of London, in base a criteri di unicità evolutiva e di esiguità della popolazione, considera Romerolagus diazi una delle 100 specie di mammiferi a maggiore rischio di estinzione.

Il coniglio del vulcano (Romerolagus diazi Ferrari-Pérez, 1893) è un mammifero della famiglia dei Leporidi. È l'unica specie del genere Romerolagus Merriam, 1896.

Beuodegis triušis (lot. Romerolagus diazi, angl. Volcano Rabbit, vok. Vulkankaninchen) – kiškinių (Leporidae) šeimos žinduolis. Tai vienintelė rūšis, priklausanti beuodegių triušių (Romerolagus) genčiai.

Kūnas 28-31 cm ilgio. Kailis minkštas, gana tankus. Nugaros pusė pilkai ruda, su geltonos spalvos priemaiša, pilvas pelenų spalvos. Ausys apie 4-4,4 cm ilgio. Užpakalinės kojos trumpos.

Paplitęs Meksikoje. Arealas labai mažas. Gyvena tankioje augalijoje, kur išmindžioja gerai matomus takus. Aktyvus naktį. Išsikasa urvus, kuriuose slepiasi dieną. Nėštumas trunka 38-40 dienų. Per metus būna viena vada (1-4 jaunikliai).

Beuodegis triušis (lot. Romerolagus diazi, angl. Volcano Rabbit, vok. Vulkankaninchen) – kiškinių (Leporidae) šeimos žinduolis. Tai vienintelė rūšis, priklausanti beuodegių triušių (Romerolagus) genčiai.

Kūnas 28-31 cm ilgio. Kailis minkštas, gana tankus. Nugaros pusė pilkai ruda, su geltonos spalvos priemaiša, pilvas pelenų spalvos. Ausys apie 4-4,4 cm ilgio. Užpakalinės kojos trumpos.

Paplitęs Meksikoje. Arealas labai mažas. Gyvena tankioje augalijoje, kur išmindžioja gerai matomus takus. Aktyvus naktį. Išsikasa urvus, kuriuose slepiasi dieną. Nėštumas trunka 38-40 dienų. Per metus būna viena vada (1-4 jaunikliai).

Arnab Gunung Berapi, juga dikenali sebagai teporingo atau zacatuche (Romerolagus diazi) ialah sejenis arnab kecil yang hidup di pergunungan Mexico. Ia merupakan spesies arnab kedua terkecil di dunia, mengekori Arnab Kerdil. Arnab ini mempunyai telinga kecil yang kebulatan, kaki yang pendek, dan bulu yang pendek dan nipis. Arnab Gunung Berapi tinggal secara berkelompok dua hingga lima ekor dalam sarang bawah tanah. Berbeza dengan kebanyakan spesies arnab (tetapi serupa dengan pika), Arnab Gunung Berapi tidak berdebap-debap atas tanah, sebaliknya mengeluarkan bunyi yang nyaring untuk memberikan amaran bahaya kepada arnab yang lain. Ia merupakan haiwan nokturnal yang cukup aktif mulai waktu senja hingga subuh. Berat Arnab Gunung Berapi sekitar 390–600 g (14–21 oz). Tepat pada tahun 1969, terdapat 1000 hingga 1200 ekor yang hidup secara liar.

Arnab Gunung Berapi tinggal di Mexico, terutamanya di lereng-lereng gunung berapi Iztaccíhuatl, Pelado, Popocatepetl, dan Tlaloc. Arnab Gunung Berapi sering dijumpai pada aras tinggi 2,800 m hingga 4,250 m, di hutan pokok pain dengan semak [[rumput rumpun yang tebal dan rupa bumi berbatu-batan yang bergelar paksi neovolkanik melintang.

Arnab Gunung Berapi memakan daun hijau rumput zacaton, daun muda hebra berduri dan kulit pokok alder. Pada musim tengkujuh, ia juga memakan oat dan jagung tanaman.

Arnab Gunung Berapi paling teruk diancam oleh kemusnahan habitat dan kegiatan memburu.[1]

Kumpulan Pakar Lagomorfa IUCN/SSC telah merangkakan pelan tindakan untuk arnab ini, yang bertumpukan perlunya mengawal pembakaran dan peragutan berlebihan habitan zacaton serta menguatkuasa undang-undang yang melarang penangkapan, penjualan dan pemburuan. Selain itu, pemulihan habitat serta penentuan koridor zacaton untuk menghubungkan kawasan habitan utama adalah diperlukan. Koloni pembiakan dalam kurungan wujud di Jersey Zoo, UK dan Zoo Chapultepec, Bandar Mexico.

Arnab Gunung Berapi, juga dikenali sebagai teporingo atau zacatuche (Romerolagus diazi) ialah sejenis arnab kecil yang hidup di pergunungan Mexico. Ia merupakan spesies arnab kedua terkecil di dunia, mengekori Arnab Kerdil. Arnab ini mempunyai telinga kecil yang kebulatan, kaki yang pendek, dan bulu yang pendek dan nipis. Arnab Gunung Berapi tinggal secara berkelompok dua hingga lima ekor dalam sarang bawah tanah. Berbeza dengan kebanyakan spesies arnab (tetapi serupa dengan pika), Arnab Gunung Berapi tidak berdebap-debap atas tanah, sebaliknya mengeluarkan bunyi yang nyaring untuk memberikan amaran bahaya kepada arnab yang lain. Ia merupakan haiwan nokturnal yang cukup aktif mulai waktu senja hingga subuh. Berat Arnab Gunung Berapi sekitar 390–600 g (14–21 oz). Tepat pada tahun 1969, terdapat 1000 hingga 1200 ekor yang hidup secara liar.

Het vulkaankonijn (Romerolagus diazi), in Mexico bekend als teporingo of zacatuche, is een klein konijn dat in de bergen van Mexico leeft. Het is, na het dwergkonijn, het op een na kleinste konijn ter wereld.

Dit kortharig konijn heeft kleine afgeronde oren en relatief korte poten. De bovenpels is voorzien van gele en zwarte haren. De lichaamslengte bedraagt 23 tot 32 cm, de staartlengte 1 tot 3 cm en het gewicht 375 tot 600 gram.

Anders dan veel konijnensoorten (en net als veel fluithazen) maakt het vulkaankonijn erg hoge geluiden om andere konijnen te waarschuwen voor gevaar, in plaats van te stampen met zijn poten. Het is een in groepsverband levend nachtdier en erg actief vanaf de schemering tot aan de dageraad. Het vulkaankonijn leeft in groepen van twee à vijf dieren in een hol. Zijn voedsel bestaat voornamelijk uit lange grassen. In 1969 leefden er tussen de 1000 en 1200 in het wild.

Deze soort komt voor in naaldbossen en open habitats op vulkaanhellingen in centraal Mexico.

Bronnen, noten en/of referentiesHet vulkaankonijn (Romerolagus diazi), in Mexico bekend als teporingo of zacatuche, is een klein konijn dat in de bergen van Mexico leeft. Het is, na het dwergkonijn, het op een na kleinste konijn ter wereld.

Króliczak wulkaniczny[3], królik wulkaniczny[4] (Romerolagus diazi) – gatunek ssaka z rodziny zającowatych (Leporidae). Średnia długość życia wynosi 7-9 lat. Zazwyczaj 2-5 osobników bytuje we wspólnej norze. R. diazi prowadzi nocny tryb życia. Przejawia największą aktywność podczas zmierzchu[5], chociaż może być również aktywny w dzień, gdy niebo jest zachmurzone[6]. W roku 1994 liczebność gatunku oszacowano na 1200 osobników[7].

Gatunek po raz pierwszy opisany naukowo przez F. Ferrari-Péreza w 1893 roku w publikacji A. Díaza Catálogo de los objetos que componen el contingente de la Comisión, precedido de algunas notas sobre su organización y trabajo pod nazwą Lepus diazi[8]. Jako miejsce typowe autor wskazał teren w pobliżu San Martín Texmelusán, na północno-wschodniej skarpie wulkanu Iztaccíhuatl w Meksyku[8]. Jedyny przedstawiciel rodzaju Romerolagus – króliczak[3], utworzonego przez C. H. Merriama w 1896 roku[9].

Gatunek typowy: Lepus diazi Ferrari-Peréz, 1893

Nazwa rodzajowa jest połączeniem nazwiska M. Romero (1838-1898), meksykańskiego polityka, ambasadora Meksyku w Stanach zjednoczonych oraz greckiego słowa λαγός lagós – „zając”[10]. Epitet gatunkowy honoruje A. Díaza (1829-1893), meksykańskiego inżyniera wojskowego, geografa i podróżnika.

Króliczak wulkaniczny to gatunek endemiczny,którego występowanie ograniczone jest do centralnych gór Transvolcanic Belt na południe od miasta Meksyk[11]. Populacja obejmuje zasięg 4 wulkanów (Popocatepetl, Iztaccihuatl, El Pelado,Tlaloc) w Transvolcanic Belt. R. diazi występuje na wysokości 2800–4250 m n.p.m.[2]. Największe zagęszczenie zanotowano na wysokości 3150 – 3400 m n.p.m. Areał wynosi w przybliżeniu 386 km². Preferuje siedliska trawiaste ze zgrupowaniami sosnowymi[12].

Samice rodzą młode w szczelinach skalnych i opuszczonych norach[12]. Prawdopodobnie króliczak wulkaniczny nie buduje własnych nor[13]. Ciąża trwa 38-40 dni. Wykazuje aktywność rozrodczą przez cały rok, której maksimum przypada w ciepłe, deszczowe dni lata. Całkowita długość ciała u noworodków waha się od 8,3-10,6 cm[5], przy masie ciała 25-27 g (samice) oraz 32 g (samce)[14]. Monogamiczny w niewoli. Do rozrodu przystępuje jedynie dominująca para[15].

Króliczak wulkaniczny żywi się zielonymi liśćmi i korą drzew. Główny składnik diety stanowią: Festuca amplissima, Muhlenbergia macroura, Stipa ichu oraz Eryngium rosei[2]. W porze deszczowej spożywa także owies i kukurydzę z upraw. Liczebność króliczaka wulkanicznego maleje na obszarach skalistych. Występują liczniej, tam gdzie środowisko obfituje w zioła i wyższe trawy. Zagrożenie dla tego gatunku stanowi wypas zwierząt, cięcie traw i pożary. Trawy są bardzo ważne dla króliczaka wulkanicznego w prawie wszystkich porach roku, a zwłaszcza w porze deszczowej. Podczas pory suchej królik opiera się głównie na konsumpcji fragmentów krzewów i drzew. Ilość białka w pokarmie należy do głównych czynników ograniczających wielkość populacji. Badania wskazują, że wiele osobników cierpi na poważną niedowagę[2].

Króliczak wulkaniczny przyczynia się do dyspersji nasion i owoców roślin w swoim otoczeniu. Króliczak wulkaniczny jest żywicielem licznych pasożytów m.in.: Boreostrongylus romerolagi, Thichostrongylus calcaratus, Longistrata dubia, Dermatoxys veligera, Trichuris leporis, Anoplocephaloides romerolagi. Stanowi również łup dla: łasicy długoogonowej, rysia rudego, kojota i myszołowa rdzawosternego[7].

Nie został stwierdzony żaden pozytywny wpływ na gospodarkę człowieka[16]. Niekiedy R. diazi żeruje na roślinach uprawnych, powodując straty w rolnictwie[17].