pt-BR

nomes no trilho de navegação

Crocuta crocuta is one of the top predators in Africa. However, there are several species which may kill them. In one study 13 of 24 hyaena carcasses found were killed by lions. Hyaenas and lions compete directly for food and often scavenge each other's kills. This competition often leads to antagonistic encounters that may result in death. In addition, humans often kill hyaenas in numerous ways. Through the early 1960's, hyaenas were shot on sight in numerous parks and game reserves in East Africa. Otherwise, this species is free of predators.

Known Predators:

Crocuta crocuta is well known for the wide variety of vocal communication used. Groans and soft squeals are emitted during hyaena greetings. A whoop is used as a contact call in addition to a fast whoop which is used by excited hyaenas at a kill. Males give the fast whoop more often than females but are generally ignored. Female calls generally elicit much more of a reaction. Finally, a lowing call is used by impatient hyaenas who are kept waiting at a kill.

In addition to the previously mentioned calls, hyaenas give several calls related to aggression. These include grunting, giggling, growling, yelling, and a rattling growl. These calls are given in various aggressive interactions with clan members, other clans, or other species. The giggling is the trademark "laughing" call of the hyaena. Is associated with fear or excitement and is often given when an individual is being chased.

Spotted hyaenas also perform a phallic inspection as a greeting. Two individuals stand head to tail, lift the rear leg closest to the other and then sniff and touch each other's extended phallus for up to 30 seconds. Females usually do not greet males in this manner, and if they do it is usually only the highest ranking males. Cubs can perform this ritual within the first month of life.

Chemical communication occurs because of the use of common latrine areas, as well as in scent marking. Tactile communication is involved in the genital investigation greeting, as well as between mothers and their young, rival young, and mates.

Communication Channels: visual ; tactile ; acoustic ; chemical

Other Communication Modes: scent marks

Perception Channels: visual ; tactile ; acoustic ; chemical

Crocuta crocuta has been categorized as a "Lower Risk" species by the IUCN Hyaena Specialist Group. In addition, the group has identified this species as "Conservation dependent". This means that there is currently a conservation program aimed at this species, but without this program the species would most likely be eligible for threatened status within 5 years.

US Federal List: no special status

CITES: no special status

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: least concern

Crocuta crocuta is a common predator on domestic livestock in Africa. In addition, they have also been known to attack and kill humans, especially during human disease outbreaks.

Negative Impacts: injures humans; crop pest

Crocuta crocuta is a large, common carnivore in many parts of Africa and so it is quite a resource for safari companies and should be considered an important part of the tourist industry. The species is sport hunted in some places in Africa, although hyaenas are not much in demand from trophy hunters because they are not viewed as very attractive. They are also hunted sometimes for food or medicine.

Positive Impacts: food ; ecotourism ; source of medicine or drug

Hyaenas are the most numerous large predator in Africa in areas where ungulates are common. Thus, they are an extremely important component of this ecosystem. Hyaenas utilize almost every part of their prey except for horns and rumen, and scavenge often.

Ecosystem Impact: keystone species

Hyaenas have a reputation for being mostly scavengers, however, this is not accurate. A study in the Kalahari found that 70 % of the diet was composed of direct kills. Typically, clans split up into hunting groups of 2 to 5 individuals, although zebra are hunted in larger groups. In the Serengeti and Ngongoro crater, Tanzania, C. crocuta was observed eating a wide variety of items including wildebeest, zebra, Thompson's gazelle, Grant's gazelle, topi, kongoni, waterbuck, eland, Cape buffalo, impala, Warthog, hare, springhare, ostrich eggs, bat-eared fox, golden jackal, porcupine, puff adder, domestic animals, lion, other hyaenas, termites, and afterbirth. Fecal analysis in these same two areas revealed that about 80 % of the samples contained wildebeest, zebra, and various gazelle species. In a study in Senegal, Hyaenas were found to prey on large herbivores such as buffalo, hartebeest, kob, warthog, bushbuck. In addition, C. crocuta has been known to prey on the young of giraffe, hippopotamus and rhinoceros.

Crocuta crocuta uses its keen senses of sight, hearing and smell to hunt live prey and to detect carrion from afar. It often chases its prey long distances at speeds up to 60 km/hr. A chase in the Kalahari lasted 24 km before the prey, an eland, was captured. In the Serengeti, many prey species of ungulates are migratory and are not found in the clan territory during some parts of the year. When this occurs, the clan goes on hunting trips to the nearest concentrations of prey. The average round trip for these trips is about 80 km and a lactating female can make 40 to 50 trips per year for a total of 2800 to 3600 km per year.

Animal Foods: birds; mammals; fish; eggs; carrion ; terrestrial non-insect arthropods

Other Foods: dung

Primary Diet: carnivore (Eats terrestrial vertebrates, Scavenger )

Through the end of the Pleistocene, spotted hyenas, Crocuta crocuta, ranged throughout Eurasia and the reasons for its extinction there are not certain. Until very recently, spotted hyaenas were a common species in most of sub-Saharan Africa. Since 1970, confirmed records of C. crocuta have been recorded in Tanzania, Kenya, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Mozambique, South Africa, Botswana, Namibia, Congo, Sudan, Central African Republic, Cameroon, Nigeria, Burkina Faso, Ivory Coast, Mali, Senegal, and Sierra Leone. Hyenas occur throughout sub-Saharan Africa, but their density varies widely across this area. Only occasional animals are seen in some areas (forests of Mt. Kenya) and they have been extirpated from most areas of South Africa, High densities occur in the Serengeti and especially the Ngorongoro crater in Tanzania. Crocuta crocuta is the most numerous large predator in the Serengeti.

Biogeographic Regions: ethiopian (Native )

Crocuta crocuta is common in many types of open, dry habitat including semi-desert, savannah, acacia bush, and mountainous forest. The species becomes increasingly less common in dense forested habitat and is less common than Hyaena hyaena and Hyaena brunnea in desert habitats. Spotten hyaenas do not inhabit the coastal tropical rainforest of west or central Africa. In west Africa, the species prefers the Guinea and Sudan savannahs. Crocuta crocuta has been recorded from as high as 4,000 meters in east Africa and Ethiopia.

Range elevation: 4,000 (high) m.

Habitat Regions: tropical ; terrestrial

Terrestrial Biomes: desert or dune ; savanna or grassland ; forest ; scrub forest ; mountains

Other Habitat Features: riparian

Crocuta crocuta lives about 20 years in the wild. The longest known lifespan for this species in captivity is 41 years and 1 month.

Range lifespan

Status: wild: 20 (high) years.

Range lifespan

Status: captivity: 41 (high) years.

Average lifespan

Status: captivity: 12 years.

Average lifespan

Status: wild: 25.0 years.

Average lifespan

Status: captivity: 40.0 years.

Average lifespan

Status: captivity: 41.1 years.

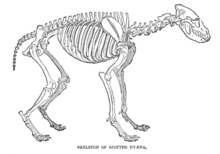

Crocuta crocuta has a sandy, yellowish or gray coat with black or dark brown spots on the over most of the body. The spots are darkest in younger animals and can be almost completely absent in very old animals. The coat is very coarse and wooly. The body length from head to tail is about 95 to 150 cm and the height at the shoulder is reported from about 75 cm to 85cm. The tail is about 30 to 36 cm long and ends in a bushy black tip. About two-thirds of the tail is composed of bone with the other one-third being solely hair. Crocuta crocuta is sexually dimorphic with females weighing around 6.6 kg more than males. Male weight ranges from about 45 to 60 kg whereas females weigh 55 to over 70 kg. Crocuta crocuta is strongly built, with a massive neck and large head topped by rounded ears, unlike the other hyaenas. The jaws are probably the strongest in relation to size of any mammal. The front legs are longer than the hind legs, which gives the back of C. crocuta a slightly odd, downward slope. The feet have four digits with short, non-retractable claws and broad toe pads.

C. crocuta females are extremely masculinated and the genitalia of females are almost indistinguishable from those of males. The clitoris is enlarged, looks like a penis, and is capable of erection. Females also have a pair of sacs in the genital region which are filled with fibrous tissue. These look much like a scrotum, but are covered with more hair than the male's scrotum. Thus, males and females look extremely similar. The female has no external vagina and must urinate, mate, and deliver young through the urogenital canal that exits through the pseudo-penis. High androgen levels were once thought to be a major cause of this masculinazation. One current hypothesis is that sexual mimicry is the driving force behind hyaena masculinization. Females that look like males may be protected from aggression from other females.

Range mass: 45 to 80 kg.

Range length: 95 to 150 cm.

Average length: 130 cm.

Other Physical Features: endothermic ; homoiothermic; bilateral symmetry

Sexual Dimorphism: female larger; ornamentation

Mating in spotted hyaenas is polygynous. Males perform a bowing display to females before mating. The male lowers his muzzle to the ground, advances quickly toward the female, bows again, and then paws the ground close behind the female. The dominance of females assures that males are timid and will retreat immediately if the female shows any aggression. The female's reproductive tract makes mating somewhat difficult. Male hyaenas approach and slide their haunches under the female to achieve intromission. Once intromission is acheived they move to a more typical mating posture, with the male's underside resting on the female's back. The female phallus is completely slack during mating.

Crocuta crocuta clans are matrilinear and females are dominant over males. Juvenile males emigrate after puberty and join new clans where their position in the dominance hierarchy may increase over time. Females, however, have stable linear dominance hierarchies. In addition, rank is inherited from the mother so, these hierarchies remain stable for many generations.

Crocuta crocuta is highly polygynous and mating is aseasonal. Although all females produce litters, alpha females have a younger age at first breeding, shorter interbirth intervals, and increased survival of offspring. These benefits are passed directly to female offspring. The mechanism responsible for the increased fitness of high ranking females is probably the increased access to food that alpha females receive. In addition, high ranking female hyaenas seem to preferentially give birth to sons. Infanticide has been witnessed several times in the wild both by hyaenas from neighboring clans and also by females from the same clan.

Mating System: polygynous

The gestation period is 4 months in C. crocuta. Females usually bear twins although 1 to 4 young are possible. The females give birth through their penis-like clitoris. During birth, the clitoris ruptures to allow the young to pass through. The resulting wound takes several weeks to heal. Cubs are not weaned until they are between 14 and 18 months of age. Females are capable of producing a litter every 11 to 21 months.

The newborns weigh from 1 to 1.6 kg and are quite precocious, being born with their eyes open. Newborns are almost entirely black. If siblings are the same sex, they begin fighting violently soon after birth, which usually results in the death of one of the two. Since single young receive more food and mature faster, this behavior is probably adaptive. Two to six weeks after birth, the mother transports young from the burrow in which they were born, often an abandoned aardvark, warthog or bat-eared fox burrow, to a communal den. The major source of food for the young during this time is milk from the mother.

Communal denning seems to be an important part of spotted hyaena social behavior, but no communal care of young takes place. One exception to this has been observed in the Kalahari during a particularly difficult period.

Breeding interval: Spotted hyaenas breed about every 16 months with a range from 11 to 21 months.

Breeding season: Breeding can occur throughout the year.

Range number of offspring: 1 to 4.

Average number of offspring: 2.

Average gestation period: 110 days.

Range weaning age: 12 to 16 months.

Average time to independence: 18 months.

Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female): 21 to 48 months.

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female): 40 months.

Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male): 2 (low) years.

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male): 3 years.

Key Reproductive Features: iteroparous ; year-round breeding ; gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); sexual ; fertilization ; viviparous

Average birth mass: 1390 g.

Average gestation period: 110 days.

Average number of offspring: 2.

Crocuta crocuta has the highest parental investment of any carnivore for several reasons. First, spotted hyaena milk has extremely high energy content. The mean protein content is 14.9 %, and the mean fat content is 14.1 %. This is only exceeded by some bears and sea otters. Weaning occurs from about the age of 12 to 16 months, which is extremely late. By the weaning age, juvenile hyaenas already have completely erupted adult teeth, which is also very rare. The age at sexual maturity is about three years, although some males may be sexually active at two. C. crocuta females are very protective of their young and do not tolerate other hyaenas around them at first. Finally, females intervene on behalf of their daughters in antagonistic encounters and form coalitions with them to secure the place of the daughters in the dominance hierarchy immediately below that of the mother. Males have not been reported to have a role in parental care.

Parental Investment: no parental involvement; precocial ; female parental care ; pre-fertilization (Protecting: Female); pre-hatching/birth (Provisioning: Female, Protecting: Female); pre-weaning/fledging (Provisioning: Female, Protecting: Female); pre-independence (Provisioning: Female, Protecting: Female); post-independence association with parents; extended period of juvenile learning; inherits maternal/paternal territory; maternal position in the dominance hierarchy affects status of young

Spotted hyenas(Crocuta crocuta)are the largest of the three hyena species.The earliest records first described hyenas as a dog hybrid but they are more closely related to cats.Spotted hyenas are identified by their sandy, yellowish coat with dark brown or black spots all over its body.These hyenas are strongly built and weigh between50 – 86 kgs.Females tend to be larger than males but both sexes look similar to each other.

If your first instinct is to look between a hyena’s legs in order to tell the sexes apart, you’re in for a surprise.Thegenitalia of female hyenasare remarkably similar to their male counterparts.The current theory for this sexual mimicry is that females that look like males are protected from aggression from other females in the clan.

Spotted hyenas are renowned for their scavenging behaviour but they are skilled hunters as well.They have exceptional hearing and excellent night vision.A clan will work together to isolate a herd animal and pursue it to its death.Common prey itemsare antelope, wildebeest, zebra but they also consume birds, reptiles and insects.Spotted hyenas act aggressively toward each other when feeding but they compete with each other by the speed of eating instead of directly fighting with one another.

Spotted hyenas have the greatest parental investment in their young.Females have a litter of 1 – 4 cubs that are only weaned at 14 months.Typically, only two cubs are born.Their mother’s milk is extremely high in protein and fat and females are highly protective of them.At first, a female will not tolerate other hyenas around her cubs.

Spotted hyenas are listed as a species of Least Concern by theIUCN Red list.

For more information on MammalMAP, visit the MammalMAPvirtual museumorblog.

Die gevlekte hiëna (Crocuta crocuta), ook bekend as die laggende hiëna,[1] is 'n soogdierspesie van 'n hiëna uit die orde Carnivora. Hulle is mediumgrootte karnivore wat inheems aan Sub-Sahara-Afrika is. Gevlekte hiënas is die enigste oorlewende spesie in die genus Crocuta. Hulle lyk op hondagtige diere (bv. wolwe, honde, ens.), maar dié diere behoort tot 'n heel ander familie.

Die gevlekte hiëna is gelys as van die minste kommer deur die IUCN weens sy wye verspreiding en groot getalle, beraam op tussen 27 000 en 47 000 individue.[2] Die spesie ervaar egter 'n daling in getalle buite beskermde gebiede, as gevolg van habitatverlies en stropery. Die spesie het waarskynlik ontstaan in Asië,[3] en was teenwoordig oor die hele Europa vir ten minste een miljoen jaar tot die einde van die Laat Pleistoseen.

Die gevlekte hiëna is die grootste bekende lid van die Hyaenidae, en is verder fisies onderskeibaar van ander spesies deur sy vaagweg beeragtige bou,[4] sy ronde ore,[5] minder prominente maanhare, gevlekte pels,[5] sy dubbeldoel tandgebit,[6] minder tepels[7] en die teenwoordigheid van 'n pseudo-penis by die vroulike lede. Dit is die enigste soogdier spesies met 'n gebrek aan 'n eksterne vaginale opening.[8]

Gevlekte hiënas is bekend vir hulle krysende geblawwery, wat soms met die histeriese lag van 'n mens vergelyk word. Hulle word dikwels foutiewelik as aasdiere beskryf, maar is egter kragtige jagters en die oorgrote meerderheid van hul dieet bestaan uit prooi wat hulle self vang. Gevlekte hiënas word as die mees effektiewe aasdiere beskou. Hulle is die enigste diere met 'n spysverteringstelsel wat bene, hoewe, horings en vel kan verteer.[9]

'n Gemiddelde volwasse hiëna weeg ongeveer 60 kg en bereik 'n hoogte van ± 75 cm; dit is ook die grootste van al die hiëna-soorte. Alhoewel dit 'n nagdier is, word dit dikwels gedurende die dag waargeneem. Die gevlekte hiëna het 'n loopsnelheid van 15 km/h, maar kan versnel tot 50 km/h wanneer hy hardloop.

'n Wyfie is vir drie maande dragtig en kan telkens geboorte skenk aan twee tot drie kleintjies. Gevlekte hiënas het 'n moontlike lewensduur van 25 jaar.

Die gevlekte hiëna (Crocuta crocuta), ook bekend as die laggende hiëna, is 'n soogdierspesie van 'n hiëna uit die orde Carnivora. Hulle is mediumgrootte karnivore wat inheems aan Sub-Sahara-Afrika is. Gevlekte hiënas is die enigste oorlewende spesie in die genus Crocuta. Hulle lyk op hondagtige diere (bv. wolwe, honde, ens.), maar dié diere behoort tot 'n heel ander familie.

Die gevlekte hiëna is gelys as van die minste kommer deur die IUCN weens sy wye verspreiding en groot getalle, beraam op tussen 27 000 en 47 000 individue. Die spesie ervaar egter 'n daling in getalle buite beskermde gebiede, as gevolg van habitatverlies en stropery. Die spesie het waarskynlik ontstaan in Asië, en was teenwoordig oor die hele Europa vir ten minste een miljoen jaar tot die einde van die Laat Pleistoseen.

La hiena enllordiada o hiena motuda (Crocuta crocuta) ye una especie de mamíferu carnívoru de la familia Hyaenidae.[1] Habita n'África al sur del Sáhara en praderíes y terrenes abiertos llanos, ausente de la cuenca del ríu Congo, Madagascar y cuasi toa Sudáfrica. Puen atopase inclusive abargana d'asentamientos humanos.[2] Ye la única especie del so xéneru y nun se reconocen subespecies vivientes. anque mientres el Pleistocenu vivió una subespecie, la hiena de los covarones (C. c. spelaea).[3]

Miden ente 100 y 170 cm de llargu y pesen ente 50 y 85 kg (los machos) y ente 55 a 75 kg (les femes) o ente 50 y hasta 90 kg, siendo les femes de mayor tamañu que los machos.[4][5][6][7][8] Tienen los miembros anteriores llixeramente más llargos que los posteriores. El so pelame ye curtiu, ente amarellentáu y acoloratáu, con llurdios ovalaos ya irregulares de color marrón escuru que falten en cabeza, gargüelu y tórax; clina curtia y arizada; la cola tien una guedeya de pelo llargu y negru. Anque paez un perru, la hiena ta más emparentada colos félidos, y especialmente, colos herpéstidos y vivérridos. La hiena enllordiada ye la especie más grande d'hiena. [9][10]

El periodu de xestación ye d'unos 110 díes, tres los cualos les femes paren dos críes, escepcionalmente una o trés. La críes nacen colos güeyos abiertos y pesen de media 1,5 kilogramos. En periodos de bayura tienen descendientes femes que suelen permanecer na cla y en periodos d'escasez machos que salen fuera. Los machos algamen el maduror sexual a los dos años, y les femes a los trés.

Cacen en grupos de 10 a 30 individuos, comandados por una fema dominante. Los sos poderosos quexales y potentes mueles tán preparaes pa una alimentación a base de carne, pudiendo encloyar los güesos, dientes y cornamentas de les sos preses.[11][12][13][14] Anque tán consideraes como carroñeres, son cazadores que carroñen cuando ye oportunu. La so dieta comprende dende inseutos a cebres, connochaetes ya inclusive xirafes, alimentándose tanto de cadabres como de preses vives, principalmente de los animales morrebundos y enfermos.[15] Les disputes por cadabre d'animales ente hienes enllordiaes y lleones son comunes.[16] Si'l grupu d'hienes nun ye bien numberosu, los lleones suelen ganar, polo que la dentición de les hienes afecha a romper güesos déxa-yos estazar el cadabre primero que lleguen otros carnívoros. Asina, cada hiena pue llevase un cachu, esvalixase y nun dexar nada. Suelen esconder los restos de comida nel fango y la so bona memoria déxa-yos recordar ónde lo dexaron. Les hienes son desaxeradamente intelixentes y munchos espertos les consideren intelectualmente comparables a los osos ya inclusive a los simios.[17][18]

La hiena enllordiada o hiena motuda (Crocuta crocuta) ye una especie de mamíferu carnívoru de la familia Hyaenidae. Habita n'África al sur del Sáhara en praderíes y terrenes abiertos llanos, ausente de la cuenca del ríu Congo, Madagascar y cuasi toa Sudáfrica. Puen atopase inclusive abargana d'asentamientos humanos. Ye la única especie del so xéneru y nun se reconocen subespecies vivientes. anque mientres el Pleistocenu vivió una subespecie, la hiena de los covarones (C. c. spelaea).

Xallı kaftar (lat. Crocuta crocuta) — Kaftarlar fəsiləsindən yırtıcı məməli heyvan növü.Ön ayaqları uzun arxa ayaqları isə nisbətən daha qısadır.Çənələri çox güclüdür

La hiena tacada (Crocuta crocuta), també anomenada hiena riallera[cal citació], és una espècie de mamífer carnívor de la familia Hyaenidae, de la qual és l'espècie viva més forta i gran.[2]

Es creu que la hiena tacada s'ajusta al chaus descrit per Plini el Vell, el qual fou descrit més tard per Linnaeus com a part de la tribu dels gats. També es pensa que es correspon amb la Crocotta d'Estrabó, el qual creia que es tractava d'un híbrid de gos i llop.[3] Representacions esculpides indiquen que l'espècie era una espècie rara pels antics egipcis, els quals la consideraven prou exòtica per incloure-la en la seva col·lecció d'animals ferotges i excloure-la dels seus animals sagrats.[3] Alguns estudiosos interpreten la descripció errònia d'Aristòtil de la hiena tacada com un animal hermafrodita, com a una confusió entre la hiena tacada i la hiena ratllada.[4]

En la dotzena edició del Systema Naturae, Linné va col·locar les hienes dins del gènere Canis, entre els llops i les guineus. Brisson ja havia donat forma a una distinció de gènere sota el nom Hyæna. En la seva edició del Systema Naturæ de Linné, Johann Friedrich Gmelin els donà a les espècies amb taques el nom binomial Canis crocuta, encara que Thomas Pennant les havia descrit prèviament sota el nom de Hyæna, i les havia col·locat dins la categoria de hienes tacades. Georges Cuvier va col·locar les Hyænas dins l'última subdivisió dels digitígrads, seguint als vivèrrids i precedint als fèlids.[4] Cuvier estava convençut que hi havia almenys dues espècies diferents de hiena tacada, basant-se en diferències regionals del color del seu pelatge. No obstant això, els naturalistes posteriors no ho van acceptar, donat que, tot i que van observar les diferències en el color del pelatge, no hi havia altres diferències que justifiquessin plenament classificar-les com espècies diferents.[5] John Edward Gray va trasllar la hiena tacada a la família dels Fèlids, situant-la en una categoria que incloïa altres hines i el pròteles. M. Lesson va ordenar els hyænids dins la seva tercera secció de digitígrads, una secció formada per animals sense una dent petita darrere del molar inferior. La hiena tacada fou col·locada entre els pròteles i els gats, i anomenada Hyæna capensis.[4]

Diverses llengües africanes, com el dioula, el ful, el suahili, el malinké, el mossi, el ngambay i el wòlof, no tenen nom distintiu per les hienes, i fan servir el mateix nom per totes les espècies de hiena. En altres llengües, les altres espècies simplement són anomenades hiena tacada petita, com el suahili, en què la hiena tacada rep el nom de fisi i el pròteles s'anomena fisi ndogo.[6]

El seu pèl és més curt que el de la hiena ratllada, i la seva crinera menys abundant.[7] Té unes extremitats anteriors i un coll poderosos que rivalitzen amb els del lleopard,[8] encara que les extremitats posteriors són comparativament petites. La gropa és arrodonida en lloc d'angular, el qual evita que els atacants que les persegueixen pel darrere, s'hi puguin adherir amb fermesa.[9] Les femelles són considerables més grans que els mascles, arribant a assolir fins a un 12% més de pes.[10] Els adults tenen una longitud del cos que varia entre 95 i 165 centímetres, i tenen una alçada a les espatlles que varia entre 70 i 91 centímetres.[11] Els mascles adults del Serengeti pesen entre 40,5 i 55 quilos, mentre que les femelles pesen entre 44,5 i 63,9 quilos. A Zàmbia tendeixen a ser més pesades, on els mascles tenen un pes mitjà de 67,6 quilos i les femelles de 69,2.[9] Macdonald (1992) va establir un pes màxim de 81,7 quilos,[10] mentre que Kingdon (1977) el va establir en 86.[11] Els cranis de les hienes a Zàmbia, són a més un 7% més grans i més amples que els de les poblacions del Serengeti.[9] S'ha estimat que el pes dels membres adults extints a les poblacions eurasiàtiques deuria ser d'uns 102 quilos.[12]

La seva dentadura té un propòsit més ampli que el d'altres espècies actuals de hiena, les quals són principalment carronyaires. Els tercers premolars, superior i inferior, són trituradors cònics, amb un tercer con per subjectar ossos sobresortint del quart premolar inferior. Tenen dents carnisseres darrere els premolars trituradors, la posició dels quals permet les hines a triturar els ossos amb les premolars sense esmussar les dents carnisseres,[10] les quals són més grans que les d'altres mamífers carnívors.[13] Tot i que tenen dents despropocionadament grans per contrarestar el desgast, les hienes tacades de tres anys tenen les dents gastades com un lleó de sis anys.[10] Aquestes dents combinades amb uns grans músculs a la mandíbula, li proporcionen una mossegada poderosa que pot arribar a exercir una pressió de 800 kg/cm²,[10] el qual representa un 40% més de la pressió que pot exercir la mossegada d'un lleopard.[14] Un experiment dirigit per Savage (1955) va demostrar que les mandíbules de la hiena tacada, tenen una capacitat més gran per triturar ossos que les de l'ós bru.[15] S'han observat hienes triturant i trencant ossos de girafa, els quals fan 7 centímetres de diàmetre.[16] Encara que es podria pensar que tenen les mandíbules més poderoses entre els mamífers carnívors, s'ha provat que altres animals, com els diables de Tasmània, tenen mossegades encara més fortes.[17]

Amb l'excepció de la mida, la hiena tacada presenta un petit dimorfisme sexual. Els genitals externs de la femella s'assemblen molt als dels mascles. El seu clítoris de 15 centímetres[10] és similar en forma i posició al penis, i és capaç de tenir una erecció.[9] L'única diferència visible entre el penis d'un mascle i el clítoris d'una femella, és que el penis té la punta roma.[10] Els llavis es fonen en un parell de sacs fibrosos semblants a un escrot. Generalment, quan observen animals madurs sexualment, els naturalistes fan servir la presència de mugrons com a indicador del gènere.[9] Les femelles tenen dos mugrons, encara que molt rarament en poden tenir quatre.[18] El color i les taques del pelatge varien amb l'edat i l'individu. El nombre de taques disminueix amb l'edat.[9]

Encara que no hi ha diferents subespècies existents, les hienes tacades mostren un grau de variació regional, especialment en la seva àrea de distribució del sud, on tendeixen a ser de color més fosc i marró, sobretot a l'esquena i les potes. A causa d'aquesta tonalitat més fosca, les taques de les hienes tacades del sud són menys definides i angulars que les dels seus cosins del Cap Occidental. A més, el cabell és més llarg en la forma sud-africana, en particular al voltant de les orelles.[5] Els individus de l'antic cameroons, al districte Epukiro de l'antiga Àfrica occidental alemanya i al nord i l'oest de Togo, tenen cues proporcionalment més llargues a la mitjana.[19]

La hiena tacada té una visió nocturna molt bona, el que els permet reconèixer-se mútuament en completa foscor, fins i tot si estan a favor del vent.[20]

Com altres hienes, tenen dues glàndules odoríferes anals, que s'obren en el recte dins de l'obertura anal,[21] encara que aquestes glàndules són menys sofisticades que les de les altres espècies de hiena.[10]

Les poblacions més grans de hiena tacada es troben a l'ecosistema del Serengeti (entre 7.200 i 7.700 individus) a Tanzània, al Parc Nacional Kruger (entre 1.300 i 3.900) a Sud-àfrica, i a la reserva natural de Masai Mara (entre 500 i 1.000) a Kenya. Diversos centenars d'individus no estudiats, viuen a les àrees de conservació de zimbabueses, a la reserva de caça de Selous a Tanzània, i a la conca del riu Okavango a Botswana.[22][23]

Viu en molts tipus d'hàbitats secs i oberts, incloent-hi semideserts, sabanes, matollars d'acàcies i boscos de muntanya. L'espècie es torna cada vegada menys freqüent en hàbitats de boscós densos i és menys comuna que la hiena bruna i la hiena ratllada en ambients desèrtics. No habiten a la selva tropical de la costa oest o el centre d'Àfrica. A l'Àfrica Occidental, l'espècie prefereix les sabanes de Guinea i del Sudan. Se l'ha vist en alçades de fins a 4.000 metres a l'est d'Àfrica i a Etiòpia.[22][24][23]

La hiena tacada dorm i dóna a llum en caus, que normalment no cava ella mateixa. Sovint fan servir caus abandonats pel facoquer africà, la rata llebre sud-africana o el xacal. Un cau pot albergar diverses femelles i dotzenes de cadells al mateix temps.[18] A diferència dels llops grisos, no és estrany que la hiena tacada doni cabuda als cadells de diferents ventrades en un mateix cau.[25] De vegades viuen força prop del facoquer africà, compartint els caus i dormint a pocs metres l'un de l'altre.[26] Poden dormir a l'aire lliure si el temps no és massa càlid, però en cas contrari dormen prop de llacs, rierols o en fangars o matolls densos.[27] A diferència de la majoria dels carnívors socials, les hienes tacades continuen mostrant alguns comportaments atàvics dels seus avantpassats solitaris, donat que encara van a cercar aliments per si soles, tot i que després tornen amb la seva comunitat.[28]

La hiena tacada té unes glàndules anals odoríferes que produeixen una pasta blanca. Aquesta pasta queda dipositada en les tiges d'herba, i produeix una olor de sabó de gran abast que fins i tot els éssers humans poden detectar. La pasta l'enganxen en diverses ocasions, com quan camina soles, al voltant d'una mata, quan hi ha lleons presents, l'enganxen els mascles i els cadells prop dels caus, i amb més freqüència en els seus límits territorials. Sovint, després d'enganxar la pasta, rasquen el terra amb les seves potes davanteres, el que afegeix encara més aromes que provenen de les secrecions de les seves glàndules interdigitals.[21]

La hiena tacada és un animal més social que el llop, però els seus grups no estan tan estretament units com els del gos salvatge africà.[25] Les associacions de hiena tacada són més complexes que les d'altres mamífers carnívors, les quals s'han descrit com a molt similars a les dels primats de la subfamília Cercopithecinae en la mida del grup, estructura, competició i cooperació. Com els primats, les hienes tacades utilitzen múltiples modalitats sensorials, reconeixen els seus congèneres individuals, són conscients que alguns companys de grup poden ser més fiables que d'altres, reconeixen grups familiars aliens i les relacions de rang entre clans propers, i fan un ús adaptatiu d'aquest coneixement en la presa de decisions socials. Tal com succeeix amb els primats Cercopithecinae, les posicions de dominància d'un individu dins les societats de hiena, estan determinades per les seves xarxes internes d'aliats, en lloc de la seva mida o agressivitat.[29] El nombre de membres d'un grup és molt variable. Un "clan" de hiena tacada pot incloure entre 5 i 90 membres, i és liderat per una única femella alfa, a la qual se la denomina matriarca. Els científics teoritzen que el domini hiena femella podria ser una adaptació al temps que els costa als cadells desenvolupar els cranis i mandíbules grans, i a la competència alimentaria intensa dins dels clans, el qual exigeix més atenció i dominar els comportaments de les femelles.[30] De vegades, el domini de la femella és explicat per la particularment elevada concentració d'andrògens produïda pels ovaris. No obstant això, els mascles adults tenen una concentració d'andrògens més elevada que la de les femelles. Aquest fet podria suggerir que les concentracions d'andrògens en els adults no es tenen en compte alhora d'establir els diferents rangs de dominància social.[31]

A diferència d'altres grans carnívors africans, les hienes tacades no tenen preferència per cap espècie, i només el búfal, la girafa i la zebra són significativament evitades. Generalment prefereixen preses amb un pes entre 56 i 182 quilos, amb una mitjana de 102.[32] Quan caça preses de mida gran o mitjana, tendeix a seleccionar determinades categories d'animals. Sovint selecciona animals joves, així com animals vells, encara que els animals vells no són significatius quan es tracta de zebres, a causa del seu comportament agressiu davant dels predadors.[33] Al contrari que els llops, quan cacen, les hienes tacades fan servir més la vista i l'olfacte, en lloc de seguir les petjades de les preses o viatjar en filera.[25]

Les hienes tacades cacen generalment nyus de forma individual, o en petits grups de 2 o 3 membres. Capturen nyus adults generalment després de perseguir-los uns 5 quilòmetres a velocitats de fins a 60 km/h. Les persecucions són generalment iniciades per una única hiena i, amb l'excepció de mares amb vedells, hi ha poca resistència activa per part del ramat. De vegades els nyus tracten d'escapar de les hienes entrant a l'aigua, encara que en aquests casos les hienes els capturen gairebé sempre.[26] Les zebres requereixen diferents mètodes de cacera que els utilitzats per caçar nyus, a causa del seu hàbit de córrer en grups compactes i la defensa agressiva que en fan els sementals. Sembla que les hienes planifiquen per avançat les caceres de zebres, donat que tendeixen a recrear-se en activitats com el marcatge de l'aroma abans de començar la cacera, un comportament que no es produeix quan seleccionen preses d'altres espècies. Els grups típics de cacera de zebres estan formats per entre 10 i 25 hienes. Durant una persecució, les zebres es desplacen generalment en ramats compactes, amb les hienes perseguint-les al darrere en una formació en mitja lluna. Les persecucions són generalment relativament lentes, amb una velocitat mitjana entre 15 i 30 km/h. Un semental tracta de situar-se entre les hienes i el ramat, encara que si una zebra queda enrere la formació de protecció s'estableix immediatament, generalment després d'una persecució de 3 quilòmetres. Tot i que les hienes poden assetjar al semental, generalment es concentren únicament en el ramat i en intentar esquivar els atacs del semental. A diferència dels sementals, les eugues només reaccionen agressivament contra les hienes quan les seves cries estan amenaçades. Les zebres rarament entren a l'aigua per escapar de les hienes com solen fer els nyus.[33] Una vegada la presa és capturada, les hienes la maten menjant-se-la viva.[26]

La hiena tacada augmenta la seva taxa de morts durant les temporades en les quals les seves preses donen a llum,[34] o quan es troben freqüentment desplaçades de les seves preses per altres predadors.[35]

A les zones on la hiena tacada i el lleó són simpàtrics, les dues espècies ocupen el mateix nínxol ecològic, i per tant es troben en competència directa l'un amb l'altre. En alguns casos, el grau d'encavalcament de la dieta d'ambdues espècies pot arribar a ser de fins al 68,8%.[32] Generalment els lleons ignoren les hienes, llevat que es trobin de cacera o assetjats per elles. Al mateix temps, les hienes tacades tendeixen a reaccionar visiblement en presència de lleons, hi hagi aliment o no. Els lleons s'apropien fàcilment de les preses de les hienes. Al cràter de Ngorongoro, és comú que els lleons subsisteixin en gran mesura de les preses robades a les hienes, el qual provoca que les hienes augmentin el seu índex de morts. Els lleons s'afanyen a seguir els crits de les hienes alimentant-se, un fet que va provar el Dr. Hans Kruuk, el qual trobà que els lleons s'apropaven repetidament a ell quan reproduïa una cinta amb sons de hienes alimentant-se.[35] Quan s'han d'enfrontar amb lleons per una presa, les hienes marxen o esperen pacientment a una distància entre 30 i 100 metres fins que els lleons han acabat de menjar.[36] En alguns casos, les hienes són suficientment valentes com per alimentar-se al costat dels lleons, i de vegades fins i tot poden forçar-los a deixar una presa.[18] Les hienes tacades generalment prevalen contra grups de lleones sense mascles si les superen en nombre de 4 a 1.[37] Les dues espècies poden actuar agressivament contra l'altre fins i tot quan no hi ha aliment involucrat. Els lleons poden atacar i ferir les hienes sense cap raó aparent: un mascle de lleó fou filmat matant en diferents ocasions dues hienes matriarques sense menjar-se-les.[38] La depredació d'un lleó pot representar fins a un 71% de les morts de hiena a Etosha. Les hienes tacades s'han adaptat a la pressió dels lleons que freqüentment entren als seus territoris.[39] A vegades, grups de lleons i de hienes tacades poden participar en enfrontaments totals, com en un cas que es produí a principis d'abril de 1999 a Etiòpia, en el qual 6 lleons i 35 hienas moriren en un període de dues setmanes.[40] Experiments sobre hienes tacades captives van desvelar que els espècimens sense experiència prèvia amb lleons actuaven amb indiferència quan els veien, però reaccionaven amb por a la seva olor.[18]

Tot i que els guepards i els lleopards cacen animals més petits que els que caça la hiena tacada, aquesta els roba les preses quan es presenta l'oportunitat. Els guepards són generalment fàcilment intimidats per les hienes, i ofereixen poca resistència,[35] mentre que els lleopards, particularment els mascles, poden enfrontar-se a les hienes. Hi ha registres d'alguns lleopards mascles capturant hienes.[8]

Les hienes tacades segueixen els grups de gos salvatge africà, per tal d'apropiar-se de les seves preses. Solen inspeccionar les àrees on els gossos salvatges han descansat i es mengen els excrements que es troben. Quan s'apropen en solitari a gossos salvatges amb una presa, ho fan amb cautela i tracten d'emportar-se un tros de carn discretament, encara que poden ser assetjats pels gossos en l'intent. Quan operen en grups, tenen més èxit en robar les seves preses, encara que la major tendència dels gossos per ajudar-se els uns als altres els posa en avantatge enfront de les hienes tacades, les quals poques vegades treballen a l'uníson. Els casos de gossos prenent les preses de les hienes tacades són rars. Malgrat que els grups de gossos salvatges poden rebutjar fàcilment a les hienes solitàries, en general, la relació entre les dues espècies té com a resultat un benefici unilateral per les hienes.[35]

La hiena tacada domina sobre altres espècies de hiena allà on els seus territoris s'encavalquen. La hiena bruna comparteix hàbitat amb la hiena tacada al Kalahari, on l'espècie bruna és més nombrosa que la tacada. Les dues espècies solen trobar-se als cadàvers, dels quals se sol apropiar l'espècie tacada, que és més gran. De vegades, la hiena bruna es manté al seu territori i cria els seus cadells mentre emet grunyits. Aquest fet, generalment, sembla que té l'efecte de confondre la hiena tacada, la qual actua desconcertada, però ocasionalment ataca i fereix als seus cosins més petits.[41] Al Serengeti s'han registrat interaccions similars entre la hiena tacada i la hiena ratllada.

Els xacals s'alimenten al costat de les hienes, encara que són perseguits si s'apropen massa. De vegades les hienes tacades segueixen els xacals durant la temporada de cria de la gasela, donat que són efectius seguint i capturant animals joves. En general, els dos animals s'ignoren mútuament quan no hi ha menjar o joves en joc.[35]

La hiena tacada manté generalment una distància de seguretat del cocodril del Nil. Encara que poden entrar fàcilment a l'aigua per capturar preses, eviten les aigües infestades de cocodrils.[35]

Les actualment extintes poblacions de hiena tacada que vivien a Itàlia van compartir la seva àrea de distribució amb el llop, però se les van arreglar per evitar la competència habitant les terres baixes, en lloc dels vessants afavorits pels llops. A més, les hienes s'alimentaven principalment de cavalls, mentre que els llops preferien els íbexs i els cabirols. No obstant això, llops i hienes tacades sembla que van mostrar abundants relacions negatives amb el temps, amb les poblacions de llops expandint-se a les regions on les hienes han desaparegut.[42]

La hiena tacada està millor adaptada per menjar carronya que altres predadors africans; no només són capaces de fer estelles i menjar-se els ossos del grans ungulats, també són capaces de digerir-los per complet. Poden digerir qualsevol compost orgànic dels ossos, no només la medul·la. Qualsevol compost inorgànic és eliminat amb els excrements, els quals estan formats gairebé exclusivament per una pols blanca amb uns pocs pèls. Reaccionen més fàcilment a l'aterratge dels voltors que altres carnívors africans, i són més propensos a romandre en les proximitats de les preses dels lleons o dels assentaments humans.[13] El nyu és la seva presa d'ungulat de mida mitjana més comuna tant a Ngorongoro com al Serengeti, amb la zebra i la gasela de Thomson seguides de prop.[43] Rarament ataquen al búfal africà a causa de la diferència de preferències en l'hàbitat, encara que s'han registrat atacs ocasionals a búfals adults.[26] També s'han vist hienes tacades capturant peixos,[44] testudínids,[45] humans,[46] rinoceronts negres,[47] cries d'hipopòtam,[48] elefants africans joves,[49] pangolins,[45] pitons, i un gran nombre de diferents espècies d'ungulats.[43] Els registres fòssils indiquen que les hienes tacades eurasiàtiques, en el que correspon actualment a la República Txeca, tenien com a presa principal al cavall de Przewalski. També formaven part de les seves preses el rinoceront llanut, el ren, el bisó de les estepes, el Megaloceros giganteus, l'isards i l'íbex.[50] A Itàlia, les seves preses eren el cérvol comú, l'ur, el cavall, el cabirol, la daina, el senglar i l'íbex.[42] Es creu que són responsables de la desarticulació i destrucció d'alguns esquelets d'ós de les cavernes. Els seus grans esquelets devien ser una bona font d'aliment per les hienes, especialment al final de l'hivern, quan l'aliment era escàs.[50] No obstant això, van tenir menys èxit que el lleó de les cavernes alhora d'entrar als caus de l'ós de les cavernes, a causa de les seves habilitats escaladores inferiors.[51]

Una hiena tacada ingereix com a mínim uns 14,5 quilograms de carn per àpat.[52] Encara que la hiena tacada pot actuar agressivament quan s'alimenta, competeix principalment amb els altres a través de la velocitat de menjar, en lloc de lluitant com fan els lleons.[35] Quan s'alimenta de cadàvers intactes, comença consumint primer la carn del llom i la regió anal. A continuació obre la cavitat abdominal i extreu els òrgans tous. Un cop l'estómac (les parets i el contingut) és consumit, es menja els pulmons i els muscles abdominals i de les potes. Quan s'ha menjat els muscles, el cadàver és esquarterat i les hienes s'emporten peces per menjar-se-les en pau.[52] La hiena tacada és experta en menjar-se les seves preses a l'aigua; s'han observat enfonsant-se sota l'agua per mossegar els cadàvers flotants, per després sortir a empassar. Una única hiena pot trigar menys de dos minuts en menjar-se una gasela jove,[43] mentre que un grup de 35 hienes pot consumir completament una zebra adulta en 36 minuts. La hiena tacada no necessita massa aigua, i generalment només passa uns 30 segons bevent.[52]

Les hienes tacades no són reproductors estacionals, i es poden reproduir en qualsevol moment de l'any, encara que ho fan més sovint durant l'estació humida. Les femelles són poliestriques, amb un cicle estral que té una durada de dues setmanes.[53] La ventrada sol estar formada per dues cries, encara que ocasionalment s'han registrat casos de tres cries.[53] El seu aparellament és relativament breu i generalment té lloc de nit sense la presència d'altres hienes. Els mascles mostren un comportament submís quan s'apropen a les femelles en zel, fins i tot si el mascle és més gran que la seva companya. A diferència dels cànids, les hienes no es queden enganxats després de copular.[18] Les femelles solen afavorir als mascles joves nascuts en el grup, o units al grup després d'haver nascut. Les femelles velles mostren una preferència similar, amb l'afegit de preferir mascles amb els quals han tingut relacions prèvies amistoses i llargues.[54] Els mascles passius tendeixen a tenir més èxit en festejar les femelles que els agressius.[55] Els mascles no prenen part en la cria dels cadells.[25] La durada del període de gestació tendeix a variar enormement, encara que la mitjana és de 110 dies.[53] A les últimes etapes de la gestació, les femelles dominants proporcionen nivells d'andrògens més elevats a les seves cries en desenvolupament, que les mares de menor rang. Es creu que nivells més elevats d'andrògens, resultat d'altes concentracions d'androstenediona a l'ovari, són els responsables de l'extrema masculinització del comportament femení i de la seva morfologia.[56] Això té l'efecte de fer que els cadells de femelles dominants siguin més agressius i sexualment actius que els de les femelles de menor rang, i que intentin muntar més aviat a les femelles que els de menor rang.[57]

El naixement és complicat, donat que les femelles donen a llum a través del seu clítoris estret. A més, els cadells de hiena tacada són els carnívors que neixen més grans en relació al pes de la mare.[10] En captivitat, moltes cries de mares primerenques neixen mortes, donada la llarga activitat que suposa el part, i a la natura, s'ha estimat que el 10% de les mares primerenques moren durant el part.[58] Les cries neixen amb un pèl suau i de color negre tirant a marró, i un pes mitjà d'1,5 quilograms.[18] Úniques entre els mamífers carnívors, les hienes tacades neixen amb els ulls oberts i uns canins de 6 a 7 mil·límetres i uns incisius de 4 mil·límetres. Les cries s'ataquen les unes a les altres des del moment en què neixen. Aquesta particularitat es produeix aparentment en ventrades del mateix sexe, i pot donar lloc a la mort del cadell més feble.[10] Aquest fraternicidi neonatal pot arribar a representar el 25% dels factors de mortalitat de la hiena tacada.[38] La jerarquia de la hiena tacada és nepotística, donat que les cries de femelles dominants superen automàticament en rang a les femelles adultes subordinades a la seva mare,[10] encara que poden perdre els seus privilegis si la mare mor.[38] Les femelles són molt protectores amb les seves cries, i no toleren que altres adults, particularment mascles, se'ls apropin. La hiena tacada mostra comportaments d'adult ben aviat: s'han observat cadells ensumar-se ritualment l'un a l'altre i marcar el seu espai vital abans del mes d'edat. Als deu dies del naixement, ja són capaços de moure's a una velocitat considerable. Els cadells comencen a perdre el pelatge negre i a desenvolupar el pelatge clar i amb taques dels adults als dos o tres mesos, a exhibir comportaments de cacera als vuit meses, i a participar completament en els grups de caça després del primer any.[18]

Les femelles lactants poden portar 3 o 4 quilos de llet a les seves mamelles.[10] La seva llet és molt rica, tenint el contingut proteic (14,9%) més elevat de tots els carnívors terrestres. El contingut de greixos (14,1%) és el segon més elevat després del de l'ós polar, per tant, a diferència dels lleons i els gossos salvatges, poden tenir sense alimentar als cadells durant una setmana.[59] Els cadells són alletats per la seva mare fins als 12 o 16 mesos, encara que als 3 metros ja poden processar aliment sòlid.[18]

La hiena tacada assoleix la maduresa sexual a l'edat de 3 anys.[53] L'esperança mitjana de vida als parcs zoològics és de 12 anys, amb un màxim de 25 anys.[53]

Es creu que els avantpassats de la hiena tacada se separaren de les altres hienes (hiena ratllada i hiena bruna) durant el Pliocè, fa entre 5.332 i 1.806 milions d'anys. Els ancestres de la hiena tacada probablement van desenvolupar comportaments socials en resposta a la creixent pressió dels seus rivals pels cadàvers, cosa que la va obligar a operar en grup. Les hienes tacades van desenvolupar dents carnisseres esmolades darrere dels seus premolars, per tant no els calia esperar a la mort de la seva presa, com és el cas de la hiena bruna i la hiena ratllada, i així es van convertir en grups de caçadors, així com de carronyaires. Van començar a ocupar territoris cada vegada més grans, necessaris pel fet que les seves preses sovint eren migratòries, i perquè les llargues persecucions en un territori petit hauria provocat envair el territori d'un altre clan.[10] L'evolució del comportament social de les hienes probablement va influir en els ancestres de lleó a formar les primeres manades, amb la finalitat de defensar millor les seves preses.[60][61]

Segons el registre fòssil, les espècies evolucionaren en primer lloc al subcontinent indi. La hiena tacada va colonitzar l'Orient Pròxim, Àfrica i les planes de l'edat de Gel des de l'Europa Atlàntica fins a la Xina, on va aparèixer una subespècie més gran anomenada hiena de les cavernes (Crocuta crocuta spelaea), desenvolupada com una resposta al clima fred.[62] Els naturalistes i paleontòlegs suposaren inicialment que la hiena de les cavernes era una espècie diferent a la hiena tacada, a causa de les grans diferències en les extremitats anteriors i posteriors. Björn Kurtén fou el primer a qüestionar-ho: “[…] hi ha proves que aquesta població europea tingué continuïtat amb seus representants típics del sud de les subespècies anomenades”. Això fou corroborat l'any 2004 per mitjà d'una anàlisi genètica, en la qual no es van mostrar diferències en l'ADN de les dues poblacions.[63]

Amb el declivi de les praderes fa 12.500 anys, Europa va experimentar una pèrdua massiva dels hàbitats de terres baixes que afavorien les hienes de les cavernes, i un augment corresponent de boscos mixtos. Sota aquestes circumstàncies, les hienes de les cavernes es trobaren en competència amb els llops i els humans, els quals es trobaven més a gust en els boscos i a les terres altes que en terrenys oberts i en terres baixes. Les poblacions de hiena de les cavernes van començar a disminuir després de fa aproximadament 20.000 anys, i van desaparèixer completament a l'Europa Occidental entre fa 14.000 i 11.000 anys, i abans en algunes zones.[42] La hiena tacada va desaparèixer de l'Orient Mitjà a principis de l‘Holocè, fa uns 8.000 anys, on fou substituïda per la hiena ratllada. Des de llavors, el seu rang de distribució s'ha limitat a l'Àfrica Subsahariana.[62]

En comparació amb altres hienes, la hiena tacada mostra una major quantitat relativa del lòbul frontal dedicada exclusivament al control de funcions motrius. Els estudis suggereixen fortament una evolució convergent de la intel·ligència de la hiena tacada i dels primats.[29]

Un estudi realitzat per antropòlegs evolucionistes ha demostrat que les hienes tacades superen als ximpanzés en les proves de cooperació per resoldre problemes: parelles en captivitat de hienes tacades posades a prova perquè tiressin de dues cordes a l'uníson per guanyar un premi de menjar, van cooperar amb èxit i aprendre ràpidament les maniobres sense formació prèvia. Fins i tot, les hienes experimentades van ajudar al membres del grup sense experiència a resoldre el problema. Per contra, els ximpanzés i altres primats, sovint necessiten un tractament intensiu, i la cooperació entre individus no sempre els és tant senzilla.[64]

La hiena tacada té un conjunt complex de postures per comunicar-se. Quan tenen por, les orelles estan doblegades en forma plana, sovint combinades amb mostrar les dents i aplanar la cabellera. Quan és atacada per altres hienes o gossos salvatges, baixa els seus quarts posteriors. Abans i durant un atac ferm i enèrgic, el cap es manté alt amb les orelles aixecades, la boca tancada, la crinera dreta i els quarts posteriors alts.[21] La cua generalment penja cap avall quan està relaxada, encara que pot canviar de posició segons la situació. La cua es corba per sota el ventre, quan mostra una evident tendència a fugir d'un atacant. Durant un atac, o quan està excitada, la cua es col·loca cap endavant a l'esquena. Una cua erecta no sempre va acompanyada d'una trobada hostil, ja que també s'ha observat que es produeix quan hi ha una interacció social inofensiva. Encara que generalment no mouen la cua, l'agiten quan s'apropen als animals dominants o quan tenen una lleugera tendència a fugir.[21] En acostar-se a un animal dominant, les hienes tacades subordinades caminen sobre els genolls de les seves potes davanteres en senyal de submissió.[21]

Les hienes tacades són animals molts vocàlics, produint un bon nombre de crits diferents. Generalment, els crits de tons alts volen dir por o submissió, mentre que els crits de tons baixos solen indicar una tendència a atacar.[21]

El crit fort és un so característic de la nit africana[21] audible des d'una distància de més de 5 quilòmetres.[10] És un crit de guerra, que varia de freqüència i to en funció de la urgència de la situació.[21] Les hienes tacades també emeten crits per mostrar-se com a individus, sent el ritme i l'estil un indicador de l'estatus social. A causa d'això, les hienes tacades criden per separat i no en cor com fan els grups de llops per mostrar la seva força col·lectiva. Encara que els mascles tendeixen a cridar més que les femelles de rang similar, les femelles dominants dediquen llargament als combats de crits.[10] Les rialletes i els grunyits tendeixen a ser emesos en situacions de gran excitació, i potser indiquen una tendència a fugir de conflictes o a romandre. Les rialles, crits i grunyits que acompanyen a l'alimentació en massa, tendeixen a ser dirigits als individus amb els que competeixen per un cadàver, i tenen l'efecte secundari perjudicial d'atreure lleons i altres hienes tacades.[18] El to d'un crit indica l'edat de la hiena, mentre que les variacions en la freqüència de les notes utilitzades quan emet sons, proporcionen informació sobre l'estatus social de l'animal.[65] Les femelles emeten grunyits suaus quan criden les seves cries.[18] Quan són atacades, les hienes tacades emeten grunyits forts i gemecs.[21]

Preses parcialment processades per l'home de Neandertal i posteriorment per hienes de les cavernes, indiquen que les hienes podrien prendre ocasionalment les captures de l'home de Neandertal, i que ambdós competien per les coves. Moltes coves mostren ocupacions alternants de hienes i Neandertals.[66] El descobriment d'una cova al massís de l'Altai, en la qual es trobaren proves que havia estat habitada per hienes tacades durant uns 40.000 anys, va conduir a l'especulació que la presència de hienes tacades podria haver evitat que els humans creuessin Beríngia cap Amèrica, el que explicaria perquè els humans van colonitzar el Nou Món molt més tard que es formés el pont de terra que unia Euràsia amb Amèrica. Aquest escenari es va plantejar a causa de l'existència d'un gran nombre de restes fòssils humans, datats entre fa 50.000 i 60.000 anys per sota de la latitud de Mongòlia, i comparativament poques restes de data anteriors a fa 12.000 anys més al nord, on vivien les hienes. El descobriment d'un crani de gos de 14.000 anys d'antiguitat, condueix a la teoria que la domesticació de gossos podria haver estat un factor que ajudés a creuar, donat que els gossos podrien haver estat valuosos sentinelles contra les incursions de hienes en campaments humans.[67]

Les representacions folklòriques i mitològiques de les hienes tacades, varien segons el grup ètnic en les quals s'originen. Sovint és difícil saber si les hienes representades en aquestes històries, són específicament espècies de hiena tacada, en particular a l'Àfrica Occidental, on tant les hienes tacades com les hienes ratllades sovint reben el mateix nom.[68]

Als contes de l'oest d'Àfrica, les hienes tacades de vegades són representades com musulmans dolents, que qüestionen l'animisme local que hi ha entre els Beng a Costa d'Ivori. A l'Àfrica oriental, la mitologia Tabwa retrata la hiena tacada com un animal solar que portà per primer cop el sol per escalfar la freda terra, mentre que el folklore d'Àfrica Occidental en general, mostra a la hiena com a símbol de la immoralitat, els hàbits bruts, de la perversió de les activitats normals, i altres trets negatius. A Tanzània, hi ha la creença que les bruixes fan ús de les hienes tacades com a muntures.[68] A la regió de Mtwara de Tanzània, es creu que els infants que neixen de nit mentre les hienes criden, probablement esdevindran lladres. A la mateixa zona, es creu que els excrements de hiena permeten al nens començar a caminar abans, per això no és infreqüent veure als nens amb fems de hiena embolicats a la roba.[6] Els Kaguru de Tanzània i els Kujamaat del sud de Senegal creuen que les hienes són éssers hermafrodites cobdiciosos i no comestibles. Un tribu mítica africana anomenada Bouda té la fama de tenir membres capaços de transformar-se en hiena.[69] Un mite similar té lloc a Mansoa. Aquests homes hiena són excutats quan se'ls descobreix, però un cop morts no recuperen la seva forma humana.[6]

Les hienes tacades ocupen un lloc destacat en els rituals d'algunes tribus africanes. En el culte Gelede del poble Yoruba de Benin i del sud-oest de Nigèria, s'utilitza una mascara de hiena tacada a la matinada, per assenyalar la fi de la cerimònia èfè. Donat que la hiena tacada generalment acaba amb els aliments d'altres carnívors, s'associa l'animal amb la conclusió de totes les coses. A Mali, en el culte Korè de la cultura bamana, la creença que les hienes tacades són hermafrodites apareix com un ideal enmig de l'àmbit dels ritus. El paper de la mascara de hiena tacada en els seus rituals, sovint serveix per convertir el neòfit en un ésser de moral completa, per mitjà de la integració dels seus principis masculins i femenins. El poble Beng creu que quan troben un hiena morta recentment amb l'anus invertit, cal posar-lo al seu lloc, per por a ser fulminat amb el riure perpetu. També consideren els seus excrements com a contaminació, i evacuen el poble si una hiena fa les seves necessitats dins dels seus límits. Els caçadors Kujamaat tradicionalment tracten les hienes tacades que maten, amb el respecte a causa dels ancians humans, per evitar represàlies per part dels esperits malèvols que puguin actuar en nom de l'animal mort.[68] En la tradició massai, i la d'altres tribus, els cadàvers són deixats a la intempèrie per alimentar les hienes tacades. Un cadàver rebutjat per les hienes és vist com una cosa negativa, i susceptible de provocar vergonya social, per això no és estrany que cobreixin els cossos amb greix i sang de bous sacrificats.[6]

La vocalització de la hiena tacada, similar al riure histèric humà, ha estat al·ludida en nombroses obres de literatura: riure com una hiena era un refrany comú, i apareix a The Cobbler's Prophecy (1594) de Richard Wilson, a La duquessa d'Amalfi (1623) de John Webster, i a la comèdia de Shakespeare Al vostre gust, Act IV. Sc.1.

Les hienes tacades són generalment tímides prop dels humans, i normalment fugen a una distància de 300 metres quan detecten humans apropant-se.[35] Encara que les hienes tacades han fet presa d'humans en els temps moderns, aquests incidents són rars. No obstant això, segons el SGDRN (Sociedade para a Gestão e Desenvolvimento da Reserva do Niassa Moçambique), els atacs de hienes tacades sobre humans és probable que siguin denunciats.[70] Es coneix que les hienes han atacat als humans a la prehistòria, donat que s'han trobat cabells humans en excrements fossilitzats de hiena datats entre fa 195.000 i 257.000 anys.[71] Segons el Dr. Hans Kruuk, les hienes tacades que devoren humans tendeixen a ser espècimens molt grans: una parella de hienes que van devorar homes, responsables de la mort de 27 persones l'any 1962 a Mlanje, Malawi, van pesar 72 i 77 quilos un cop abatudes.[72] El 1903, Hector Duff va escriure sobre com les hienes tacades del districte de Mzimba a Angoniland esperaven fora de les cabanes a la matinada, i atacaven les persones quan aquestes obrien les portes.[73] Segons el llibre A Book of Man-Eaters de R.G. Burton, les hienes tacades entren al campaments humans sense amoïnar-se pels focs de campament.[74] Les victimes de hiena tacada acostumen a ser dones, nens i malalts o homes dèbils. Theodore Roosevelt va escriure sobre com a Uganda entre 1908 i 1909, les hienes tacades mataven regularment a les víctimes de tripanosomosi africana mentre dormien fora dels campaments.[75] Quan ataquen a persones dormint, generalment els mosseguen al rostre i tracten d'arrossegar-les lluny d'altres humans.[76] Els Kikuyu de Kenya tenen més por a les hienes tacades que a les hienes ratllades.[77] Les hienes tacades són molt temudes a Malawi, on se sap que ataquen ocasionalment a les persones de nit, especialment durant l'estació càlida quan les persones dormen a l'aire lliure. S'han registrat molts atacs de hiena a la plana de Phalombe a Malawi, al nord del mont Michesi. El 1956 es van registrar cinc morts, cinc més l'any 1957 i sis el 1958. Aquest patró va seguir fins al 1961, any en què moriren vuit persones. Els atacs van tenir lloc generalment al setembre, quan les persones dormien a l'aire lliure, i els incendis de matolls van complicar la caça d'animals a les hienes.[70][73] Un informe de l'any 2004 del Fons Mundial per la Natura sobre notícies anecdòtiques, indica que 35 persones moriren a Moçambic a mans de hienes tacades en un període de 12 mesos, al llarg d'un tram de 20 quilòmetres de carretera prop de la frontera amb Tanzània.[70] Les actituds vers els atacs de hiena tacada tendeixen a ser silenciat en comparació amb les reaccions evocades en les zones on les hienes ratllades han atacat a persones.[6]

El grau d'impacte de les hienes tacades sobre els ramats varia segons la regió: al districte Laikipia de Kenya, l'impacte és petit en comparació a l'impacte que han produït lleons, lleopards o guepards.[78] No obstant això, el total de pèrdues a Tanzània el 2003 ascendia a 12.846 dòlars, dels quals la hiena tacada n'era responsable en un 98,2%. En un enquesta realitzada l'any 2007 a Tanzània a set poblats propers al Serengeti, les hienes tacades van resultar ser responsables del 97,7% de les pèrdues de ramats a causa de predadors.[79] A la regió dels Massai, al nord de Tanzània, la hiena tacada ataca freqüentment petits ramats (cabres, ovelles i vedells) i gossos, i ho fa generalment de nit, el qual fa més difícil d'impedir que en el cas dels lleons, els quals ataquen generalment a la llum del dia.[80]

Les hienes tacades van estar presents ocasionalment a les cases de feres dels Faraons.[3] Sir John Barrow, en la seva obra An Account of Travels Into the Interior of Southern Africa, va descriure com les hienes tacades eren entrenades en la caça a Sneeuberge, dient que eren tan fidels i diligents com qualsevol dels gossos domèstics comuns.[81] A Tanzània, els sangoma (xamans africans), de vegades, prenen cadells de hiena tacada dels seus caus, per tal d'augmentar el seu estatus.[6] Un article de la BBC d'abril del 2004, explicava com un pastor que vivia en un petit poblat de Qabri Bayah, a uns 50 quilòmetres de la ciutat de Jigjiga, a l'est d'Etiòpia, feia servir mascles de hiena tacada com a gos guardià dels seus ramats, suprimint el seu desig de marxar i trobar parella alimentant-lo amb unes herbes especials.[82] Si no es crien amb membres adults de la seva espècie, en captivitat exhibeixen comportaments de marcatge per mitjà de l'aroma molt més tard que els espècimens salvatges.[18] Poden ser molt destructives: un espècimen perfectament domèsticat, en captivitat a la Torre de Londres, va aconseguir esquinçar un tauler clavat de 2,4 metres de llarg, clavat al terra del seu recinte recentment reparat, sense aparent esforç.[83] Des del punt de vista de la cria, les hienes són fàcils de mantenir, ja que no presenten gaires problemes causats per malalties i poden arribar a viure, en captivitat, entre 15 i 20 anys.[84]

La hiena tacada és considerada per la UICN en risc mínim d'extinció a Botswana, Etiòpia, Guinea Bissau, Kenya, Namíbia, Sud-àfrica, Tanzània i Zimbabwe. Es troben en situació d'espècie amenaçada a Benín, Burundi (on es creu que està a la vora de l'extinció), Camerun, Mali, Mauritània, el Níger, Nigèria, Ruanda i Sierra Leone. Està extinta a Algèria i Lesotho. Es troba amb dades insuficients a Angola, Burkina Faso, República Centreafricana, Txad, República del Congo, Costa d'Ivori, República Democràtica del Congo, Djibouti, Eritrea, Guinea Equatorial, Ghana, Guinea, Malawi, Moçambic, el Senegal, Somàlia, Sudan, Swaziland, Togo, Uganda i Zàmbia.[85]

La hiena tacada (Crocuta crocuta), també anomenada hiena riallera[cal citació], és una espècie de mamífer carnívor de la familia Hyaenidae, de la qual és l'espècie viva més forta i gran.

Hyena skvrnitá (Crocuta crocuta) je největší druh hyeny vyskytující se v Africe jižně od Sahary. Je zároveň nejhojnější velkou africkou šelmou, celkový počet zvířat žijících ve volné přírodě se pohybuje mezi 27 000 a 47 000 (stav k roku 2015). Jedná se o potravního oportunistu – predátora i mrchožrouta zároveň, který žije ve smečkách obvykle zvaných klany. Ačkoliv dochází k postupnému poklesu počtu jedinců, Mezinárodní svaz ochrany přírody hodnotí hyenu skvrnitou jako málo dotčený druh.[2]

Hyena skvrnitá je poměrně velké zvíře, s robustní stavbou. Její tělo měří 95–166 cm, ocas 40 cm. Hmotnost se pohybuje nejčastěji mezi 45 a 70 kg,[3] ale ve výjimečných případech dosahuje až 88 kg. Samice jsou většinou větší než samci. Stavbou těla se podobá ostatním hyenám, má však ještě robustnější kostru se silným osvalením. Především její široká hlava s tupým čenichem a mimořádně silnými žvýkacími svaly působí až neforemně. Její chrup je výborně uzpůsoben k drcení kostí, pravděpodobně má nejsilnější stisk čelistí ze všech šelem. Na hlavě jsou nápadné i okrouhlé, odstávající boltce a hnědé, mírně šikmé oči. Tělo má porostlé krátkou, hrubou a dost řídkou srstí béžové, šedohnědé až rezavé barvy s černými či tmavohnědými skvrnami, hřbetní hříva je mnohem slabší než u hyeny žíhané či čabrakové. Jako ostatní hyeny má delší přední než zadní končetiny, přesto dokáže běžet velmi rychle a především vytrvale.

Hyena skvrnitá obývá savany a polopouště Afriky od Mali a Súdánu až po sever Jihoafrické republiky. Nevyhýbá se ani horským oblastem, například v Etiopii žije i ve výšce nad 2000 m n. m. Na většině území je poměrně běžná, místy, zvláště v jižní Africe, však byla vyhubena jako údajný škůdce domácích zvířat.

Hyena skvrnitá žije v rodinných klanech či tlupách, čítajících od 3 (suché oblasti s málem kořisti) až po 80 zvířat (savany s velkými stády kopytníků),[3] vedených dominantní samicí. Klany nemají tak stmelenou strukturu jako smečky psovitých šelem či lvů a málokdy operují zcela pospolu. Zatímco samice tráví ve svém klanu celý život, samci žijí kočovně – u jednoho klanu tráví většinou jen jedno období rozmnožování a poté se přesunou jinam. Teritorium klanu si hyeny značkují ostře páchnoucím výměškem análních žláz, ale také akusticky – hlasitým chechtavým vytím. Jsou aktivní především za soumraku a v noci, neplatí to však bez výjimky. Většinu dne tráví hyeny v podzemních norách, které si samy hrabou. Pokud však mají možnost, rády obsadí opuštěnou noru hrabáče, dikobraza či prasete bradavičnatého. Někdy přespávají také v jeskyních. Velmi rády se před svými doupaty sluní.

Hyeny buď aktivně loví nebo vyhledávají mršiny. Zabíjejí především kopytníky a to i velké druhy, jakými jsou třeba zebry. Někdy přepadnou i stádo domácích zvířat. Dokonce zraní i lva, nebo jej odeženou od kořisti (má se za to, že při poměru hyen ku lvicím 3:1 je rovnováha sil, při vyšším počtu hyen lvice zpravidla ustupují). I samotná hyena většinou odežene od kořisti i levharta, pravidelně krade kořist gepardovi. Pokud má možnost, zabíjí ostatním konkurenčním predátorům mláďata. Výjimečně si troufne i na lov sloních mláďat. Vlastní lov provádějí hyeny samostatně nebo v malých skupinách maximálně pěti jedinců, zcela výjimečně loví více zvířat najednou.[3] Ostatní se ale mnohdy připojí k požírání kořisti. Při získávání mršin, například od lvů, se nicméně může spojit do útoku i několik desítek zvířat. Svým mohutným chrupem rozdrtí i silné kosti. Hyena skvrnitá patří mezi úspěšné sprintery, dokáže vyvinout rychlost až okolo 60 km/h. Je i velmi vytrvalým běžcem, umí svou kořist pronásledovat i několik kilometrů (zaznamenaný rekord je 24 km).[3] Tomu odpovídá i velikost jejího srdce, které je v poměru k hmotnosti těla 2x těžší než srdce lva (cca 1 % vs. cca 0,5 %).

Březost trvá 99-130 dnů a samice rodí obvykle 1-3 mláďata, která se rodí již s otevřenýma očima a jsou porostlá jemnou černou srstí. Mláďata se mezi sebou často perou a nemá-li pro ně matka dost potravy, může se stát, že nejsilnější mládě zakousne a sežere své sourozence. Především sourozenci stejného pohlaví se k sobě chovají velmi agresívně. Matka se o mláďata pečlivě stará téměř rok, poté mladí samci klan opouštějí, zatímco samičky zůstávají i nadále v blízkosti matky. Mláďata hyen lze velmi snadno ochočit. Hyeny pohlavně dospívají ve věku 2-3 let a v zajetí se mohou dožít až 40 let, v přírodě se dožívají nanejvýš 20 let.

Pro svou nevzhlednost, podivný hlas i mrchožravost je hyena skvrnitá africkými domorodci velmi obávána a má pověst magického zvířete. Za jistých okolností může být hyena skvrnitá nebezpečná dětem či lidem, osaměle tábořícím v buši, jedná se ale jen o výjimečné případy. Etiopané v minulosti věřili, že se někteří lidé zvaní qora mohou teriantropicky proměňovat v hyeny a v této podobě škodit ostatním členům komunity nebo i zabít jiného člověka. Usvědčení qorové, patřící často ke kastě kovářů, byli v minulosti obvykle zabiti. Lidé, kteří údajně umí s hyenami komunikovat, žijí dosud v etiopském městě Hararu. Právě zde je krmení hyen skvrnitých masnými odpadky známou atrakcí pro turisty. V Súdánu i jinde v oblasti Sahelu je rozšířeno mnoho představ o nebezpečnosti hyen, které prý svým hlasem lákají lidi na osamělé místo a tam je napadnou. Pes, na kterého padne stín hyeny prý zahyne, oněmí nebo onemocní vzteklinou a zdejší čarodějnice na hyneách údajně v noci jezdí. Přesto podle Súdánců zabití hyeny přináší neštěstí a zbraň, jíž bylo zvíře zabito, není radno nadále používat, protože je magicky poskvrněná a jistě by v kritické situaci svého majitele zradila.[4] Východoafričtí Masajové, Karamodžané a další příbuzná etnika odnášejí své zemřelé do buše, aby se stali potravou hyen. Proto je pro ně hyena skvrnitá tabu. V jižní a východní Africe používají kouzelníci při přípravě tradičních léků či při obřadech různé části těla hyeny skvrnité, například její trus, chlupy, čenich, pohlavní orgány či žluč. Obdobné pověry přejali od domorodců i Evropané, kteří je dále šířili. Středověké bestiáře i díla pozdějších přírodopisců popisovaly hyeny jako zlá, zákeřná a zbabělá zvířata, která se živí mrtvolami a mohou napadat i slabé tvory včetně dětí. Neoprávněnost těchto názorů odhalil koncem 19. století Alfred Brehm a později především nizozemský zoolog Hugo van Lawick, který se pozorováním hyen soustavně zabýval. Přesto se obraz hyen jako zákeřných, zbabělých a odpudivých zvířat objevuje ještě v populárním animovaném filmu Lví král.

▪ Zoopark Na Hrádečku

Hyena skvrnitá (Crocuta crocuta) je největší druh hyeny vyskytující se v Africe jižně od Sahary. Je zároveň nejhojnější velkou africkou šelmou, celkový počet zvířat žijících ve volné přírodě se pohybuje mezi 27 000 a 47 000 (stav k roku 2015). Jedná se o potravního oportunistu – predátora i mrchožrouta zároveň, který žije ve smečkách obvykle zvaných klany. Ačkoliv dochází k postupnému poklesu počtu jedinců, Mezinárodní svaz ochrany přírody hodnotí hyenu skvrnitou jako málo dotčený druh.

Den plettede hyæne (Crocuta crocuta) er et dyr i hyænefamilien. Det er det eneste medlem af slægten crocuta. Den når en længde på 1,3 m og har en hale på 25 cm og vejer 62-70 kg. Den er dermed det største medlem af hyænefamilien og samtidig den bedst kendte hyæneart. Dyret lever i det centrale samt sydlige Afrika. Hyænen har de kraftigste kæber indenfor dyreriget.

Die Tüpfelhyäne oder Fleckenhyäne (Crocuta crocuta) ist eine Raubtierart aus der Familie der Hyänen (Hyaenidae). Sie ist die größte Hyänenart und durch ihr namensgebendes geflecktes Fell gekennzeichnet; ein weiteres Charakteristikum ist die „Vermännlichung“ des Genitaltraktes der Weibchen. Die Art besiedelt weite Teile Afrikas und ernährt sich vorwiegend von größeren, selbst gerissenen Wirbeltieren. Tüpfelhyänen leben in Gruppen mit einer komplexen Sozialstruktur, die bis zu 130 Tiere umfassen können und von Weibchen dominiert werden. Die Jungtiere, die zwar bei der Geburt schon weit entwickelt sind, aber über ein Jahr lang gesäugt werden, werden in Gemeinschaftsbauten großgezogen.

Tüpfelhyänen erreichen eine Kopfrumpflänge von 125 bis 160 Zentimetern, der Schwanz ist mit 22 bis 27 Zentimetern relativ kurz. Die Schulterhöhe beträgt 77 bis 81 Zentimeter. Das Gewicht liegt üblicherweise bei 45 bis 60 Kilogramm, einzelne Tiere können bis zu 86 Kilogramm wiegen.[1][2] Weibchen und Männchen unterscheiden sich nur geringfügig voneinander und nicht in allen Körpermaßen. Weibchen sind um 2,3 % länger und haben geringfügig größere Schädel und Brustumfänge aber keine längeren Beine als Männchen.[2] Dieser geringe Geschlechtsdimorphismus soll regional variieren und im südlichen Afrika ausgeprägter sein als in anderen Regionen des Kontinents.

Das Fell ist relativ kurz und rau, und die lange Rückenmähne ist bei der Tüpfelhyäne weniger ausgeprägt als bei den anderen Hyänenarten. Die relativ feinen Wollhaare sind 15 bis 20 Millimeter lang, die gröberen Deckhaare 30 bis 40 Millimeter. Die Grundfärbung des Fells ist sandgelb bis rötlich-braun; am Rücken, an den Flanken und an den Beinen befinden sich zahlreiche schwarze und dunkelbraune Flecken. Diese werden mit zunehmendem Alter bräunlicher oder können verblassen. Wie bei allen Hyänen sind die Vorderbeine länger und kräftiger als die Hinterbeine, wodurch der Rücken nach hinten abfällt. Die Vorder- und die Hinterpfoten enden jeweils in vier Zehen, die mit stumpfen, nicht einziehbaren Krallen versehen sind. Wie alle Hyänen sind Tüpfelhyänen digitigrad (Zehengänger). Der Schwanz endet in einer schwarzen, buschigen Spitze; ihre Haare überragen das Ende der Schwanzwirbelsäule um rund 12 Zentimeter.

Drüsen an beiden Seiten des Analkanals sondern ein Sekret an den zwischen Anus und Schwanz gelegenen Analbeutel ab. Aus diesem Analbeutel wird bei der Reviermarkierung das Sekret abgegeben. Die Weibchen haben meist nur ein Paar, selten zwei Paare Zitzen. Den Männchen fehlt wie bei allen Hyänen der Penisknochen.

Obwohl Hyänen optisch den Hunden ähneln, sind sie näher mit den Katzen verwandt.