en

names in breadcrumbs

Brook trout are found in three types of aquatic environments: rivers, lakes, and marine areas. Their living requirements in these environments are very specific. The freshwater populations occur in clear, cool, well-oxygenated streams and lakes (Scott and Crossman, 1985). Brook trout thrive in these environments with temperatures that remain below 18.8 C and where there is little to no siltation (LaConte, 1997). Stream dwelling brook trout require three habitat components, which include resting areas in pools, feeding sites near riffles or swiftly flowing water, and escape cover which normally is found along undercut banks, under woody debris, trees or large rock ledges ("Brook Trout," 1987). Brook trout that reside in marine environments migrate there from freshwater tributaries and tend to stay close to river mouths.

Habitat Regions: temperate ; saltwater or marine ; freshwater

Aquatic Biomes: lakes and ponds; rivers and streams; coastal ; brackish water

Other Habitat Features: estuarine

The brook trout's body is elongate with an average length of 38.1-50.8 cm, is only slightly laterally compressed; the body has its greatest depth at or in front of the origin of the dorsal fin (Scott and Crossman, 1985). Another physical characteristic of the brook trout is an adipose fin and a caudal fin that is slightly forked (Hubbs and Lagler, 1949). Brook trout have 10-14 principle dorsal rays, 9-13 principle anal rays, 8-10 pelvic rays, and 11-14 pectoral rays (Scott and Crossman, 1985). The brook trout also has a large terminal mouth with breeding males developing a hook or kype on the front of the lower jaw (Scott and Crossman, 1985).

The coloration of the brook trout is very distinct and can be spectacular. The back of the brook trout is dark olive-green to dark brown, sometimes almost black, the sides are lighter and become silvery white ventrally (Scott and Crossman, 1985). On the back and top of the head there are wormy cream colored wavy lines known as vermiculations which break up into spots on the side (Scott and Crossman, 1985). In addition to the pale spots on the side there are smaller more discrete red spots with bluish halos (Scott and Crossman 1985). The fins of the brook trout are also distinct; the dorsal fin has heavy black wavy lines, the caudal fin has black lines, the anal, pelvic and pectoral fins have white edges followed by black and then reddish coloration (Scott and Crossman, 1985).

Range mass: 1 to 6 kg.

Range length: 38.1 to 50.8 cm.

Other Physical Features: ectothermic ; heterothermic ; bilateral symmetry

Average lifespan

Status: wild: 24.0 years.

Average lifespan

Sex: female

Status: wild: 16.0 years.

Average lifespan

Sex: male

Status: wild: 16.0 years.

Average lifespan

Status: wild: 8.0 years.

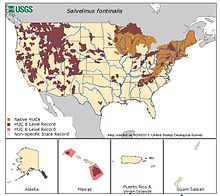

Brook trout are found as far south as Georgia in the Appalachian mountain range and extend north all the way to Hudson Bay. From the east coast their native range extends westward to eastern Manitoba and the Great Lakes (Willers, 1991). The fish has been introduced, very successfully in some areas, into many parts of the world including western North America, South America, New Zealand, Asia, and many parts of Europe (Scott and Crossman, 1973).

Biogeographic Regions: nearctic (Introduced , Native ); palearctic (Introduced ); oriental (Introduced ); neotropical (Introduced ); australian (Introduced )

The food habits of brook trout vary according to their age and life history stage. As fry, or very young fish, brook trout feed primarily on immature stages of aquatic insects (Everhart, 1961). In general a brook trout's diet can be likened to a smorgasbord of organisms with prey ranging from mayflies to salamanders (Wittman, 2001). A brook trout will virtually eat anything its mouth will accommodate, including mostly many aquatic insect larvae such as caddisflies, mayflies, midges, and black flies. Other organisms consumed include worms, leeches, crustaceans, terrestrial insects, spiders, mollusks, a number of other fish species (cannibalism is limited to spawning time and spring), frogs, salamanders, snakes and even small mammals like voles (e.g. Microtus, Cleithrionomys), should they find one in the water (Scott and Crossman, 1985). As brook trout become larger their diet shifts more towards a piscovourus one (Everhart, 1961). Sea-run brook trout eat fish and intertebrates that are commonly found in marine environments (Scott and Crossman, 1985).

Animal Foods: mammals; amphibians; reptiles; fish; insects; terrestrial non-insect arthropods; mollusks; aquatic or marine worms; aquatic crustaceans

Primary Diet: carnivore (Piscivore , Insectivore )

As a gamefish the brook trout is very highly sought after and one of the most popular, especially in north eastern North America (Scott and Crossman, 1985). The brook trout can be caught by fishing with artificial flies, spin casting, or with live bait (Scott and Crossman, 1985). Brook trout and their vastly popular sport fishing bring to a community related recreational activities such as camping, boating, and the need for gear, guides and transportation, all of which provide positive economic opportunities (Hubbs and Lagler, 1949). Brook trout have been raised in hatcheries and distributed world wide in hope of creating the above mentioned opportunities in places where they do not natively occur or to reestablish and strengthen native populations (Scott and Crossman, 1985).

Positive Impacts: food ; ecotourism

There are many extensive conservation efforts directed towards brook trout, especially naturally reproducing brook trout populations. This is because in many northeastern states and Canada brook trout, the only native stream dwelling trout in many of these places, are very susceptible to urbanization and deforestation and its effects on the surrounding aquatic ecosystems. Ohio for example has only two naturally reproducing populations of brook trout left and breeds these populations in hatcheries then placing them in other suitable habitats to reestablish these populations (LaConte, 1997). Many other states and areas in Canada are performing similar projects to preserve this treasured and threatened natural resource.

US Federal List: no special status

CITES: no special status

State of Michigan List: no special status

Perception Channels: tactile ; chemical

When in breeding colors the male brook trout are considered by many to be one of the most colorful and beautiful of all freshwater fishes (LaConte, 1997). Another interesting fact is that brook trout are actually a char not a trout (LaConte, 1997). The brook trout has also been hybridized with the brown trout, by combining brown trout (Salmo trutta) eggs with brook trout sperm, to produce a sterile tiger or zebra trout, which has proven itself to be a very good gamefish (Mills, 1971). The brook trout's sperm has also been combined with the eggs of a lake trout (Salvelinus namaycush) which results in a splake, a fish that has been introduced into some of the North American Great Lakes (Mills, 1971).

Usually only a single male is able to fertilize the eggs that a female lays in a redd, but occasionally more than one male is able to do so. Usually the largest males are the most successful breeders.

Mating System: monogamous ; polyandrous

Brook trout spawn in late summer or autumn depending on the latitude and temperature (Scott and Crossman, 1985). The type of area required for brook trout spawning is one that offers loose, clean gravel in shallow riffles or shoreline area with an excellent supply of upwelling, oxygen-rich water (LaConte, 1997). Mature fish have been known to travel many miles upstream to reach adequate spawning grounds (Scott and Crossman, 1985). Females are able to detect upwelling springs or other areas of ground-water flow, which make for excellent spawning grounds. Brook trout reach maturity on an average at the age of two and spawn every year, although their size at first maturity depends on growth rate and the productivity of thier habitat (Everhart, 1961). Males often outnumber females at the spawning site, but only rarely is more than one male able to fertilize the eggs in a particular redd (Scott and Crossman, 1985; Blanchfield et al., 2003). The females clear away debris and silt with rapid fanning of her caudal fin while on her side, creating a redd (Scott and Crossman, 1985). The redd is where the eggs will be deposited and fertilized after the males compete for spawning right to the female (Scott and Crossman, 1985). The redd actually resembles a pit that is 4-12 inches in depth (Everhart, 1961). To gain the spawning right of the female the males compete for position by nipping and displaying themselves to the competitor males (Mills, 1971). When spawning is actually taking place the male takes a position to hold the female against the bottom of the redd and both of the fish vibrate intensely while eggs and milt are simultaneously discharged (Scott and Crossman, 1985). Very shortly after this exchange takes place the female works to cover the fertilized eggs with gravel by digging slightly upstream and letting the current carry the gravel down to fill the redd (Everhart, 1961). The eggs are initially adhesive to prevent them from washing away so they are able to incubate within the gravel (Scott and Crossman, 1985). The total time of incubation depends on factors such as temperature and oxygen (Scott and Crossman, 1985). After hatch the fry remain in the gravel until the yolk sac is absorbed then the fry swim up out of the gravel to begin the next stage of their life (Scott and Crossman, 1985).

Breeding interval: Brook trout breed once per year

Breeding season: Spawning occurs in late summer or autumn

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female): 2 years.

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male): 2 years.

Key Reproductive Features: iteroparous ; seasonal breeding ; gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); sexual ; fertilization (External ); oviparous

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male)

Sex: male: 730 days.

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female)

Sex: female: 730 days.

The brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis) is a species of freshwater fish in the char genus Salvelinus of the salmon family Salmonidae. It is native to Eastern North America in the United States and Canada, but has been introduced elsewhere in North America, as well as to Iceland, Europe, and Asia. In parts of its range, it is also known as the eastern brook trout, speckled trout, brook charr, squaretail, brookie or mud trout, among others.[3] A potamodromous population in Lake Superior, is known as coaster trout or, simply, as coasters. Anadromous populations which are found in coastal rivers from Long Island to Hudson Bay are sometimes referred to as salters.[4] The brook trout is the state fish of nine U.S. states: Michigan, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Vermont, Virginia, and West Virginia, and the Provincial Fish of Nova Scotia in Canada.

The brook trout was first scientifically described as Salmo fontinalis by the naturalist Samuel Latham Mitchill in 1814. The specific epithet "fontinalis" comes from the Latin for "of a spring or fountain", in reference to the clear, cold streams and ponds in its native habitat. The species was later moved to the char genus Salvelinus, which in North America also includes the lake trout, bull trout, Dolly Varden, and the Arctic char.

There is little recognized systematic substructure in the brook trout, but two subspecies have been proposed. On the other hand, three ecological forms are distinguished.

The aurora trout, S. f. timagamiensis, is a subspecies native to two lakes in the Temagami District of Ontario, Canada.[5] The silver trout, (Salvelinus agassizii or S. f. agassizii), is an extinct trout species or subspecies last seen in Dublin Pond, New Hampshire, in 1930.[6] It is considered by fisheries biologist Robert J. Behnke as a highly specialized form of brook trout.[7]

Robert J. Behnke describes three ecological forms of the brook trout.[8] A large lake form evolved in the larger lakes in the northern reaches of its range and are generally piscivorous as adults. A sea-run form that migrates into saltwater for short periods to feed evolved along the Atlantic coastline. Finally, a smaller generalist form evolved in the small lakes, ponds, rivers, and streams throughout most of the native range. This generalist form rarely attains sizes larger than 12 in (30 cm) or lives for more than three years. All three forms have the same general appearance.

The brook trout produces hybrids both with its congeners Salvelinus namaycush and Salvelinus alpinus, and intergeneric hybrids with Salmo trutta.[9][10]

The splake is an intrageneric hybrid between the brook trout and lake trout (S. namaycush). Although uncommon in nature, they are artificially propagated in substantial numbers for stocking into brook trout or lake trout habitats.[11] Although they are fertile, back-crossing in nature is behaviorally problematic and very little natural reproduction occurs. Splake grow more quickly than brook trout, become piscivorous sooner, and are more tolerant of competitors than brook trout.[12]

The tiger trout is an intergeneric hybrid between the brook trout and the Eurasian brown trout (Salmo trutta). Tiger trout rarely occur naturally but are sometimes artificially propagated. Such crosses are almost always reproductively sterile. They are popular with many fish-stocking programs because they can grow quickly, and may help keep coarse fish (wild non "sport" fish) populations in check due to their highly piscivorous (fish-eating) nature.[13]

The sparctic char is an intrageneric hybrid between the brook trout and the Arctic char (S. alpinus).[14]

The brook trout has a dark green to brown color, with a distinctive marbled pattern (called vermiculation) of lighter shades across the flanks and back and extending at least to the dorsal fin, and often to the tail. A distinctive sprinkling of red dots, surrounded by blue halos, occurs along the flanks. The belly and lower fins are reddish in color, the latter with white leading edges. Often, the belly, particularly of the males, becomes very red or orange when the fish are spawning.[15] Typical lengths of the brook trout vary from 25 to 65 cm (9.8 to 25.6 in), and weights from 0.3 to 3 kg (0.66 to 6.61 lb). The maximum recorded length is 86 cm (34 in) and maximum weight 6.6 kg (15 lb). Brook trout can reach at least seven years of age, with reports of 15-year-old specimens observed in California habitats to which the species has been introduced. Growth rates are dependent on season, age, water and ambient air temperatures, and flow rates. In general, flow rates affect the rate of change in the relationship between temperature and growth rate. For example, in spring, growth increased with temperature at a faster rate with high flow rates than with low flow rates.[16]

Brook trout are native to a wide area of Eastern North America, but are increasingly confined to higher elevations southward in the Appalachian Mountains to northern Georgia and northwest South Carolina, Canada from the Hudson Bay basin east, the Great Lakes–Saint Lawrence system, the Canadian maritime provinces, and the upper Mississippi River drainage as far west as eastern Iowa.[8] Their southern historic native range has been drastically reduced, with fish being restricted to higher-elevation, remote streams due to habitat loss and introductions of brown and rainbow trout. As early as 1850, the brook trout's range started to extend west from its native range through introductions. The brook trout was eventually introduced into suitable habitats throughout the western U.S. during the late 19th and early 20th centuries at the behest of the American Acclimatization Society and by private, state, and federal fisheries authorities.[18] Acclimatization movements in Europe, South America, and Oceania resulted in brook trout introductions throughout Europe,[14] in Argentina,[19] and New Zealand.[20] Although not all introductions were successful, a great many established wild, self-sustaining populations of brook trout in non-native waters.

The brook trout inhabits large and small lakes, rivers, streams, creeks, and spring ponds. They prefer clear waters of high purity and a narrow pH range and are sensitive to poor oxygenation, pollution, and changes in pH caused by environmental effects such as acid rain. The typical pH range of brook trout waters is 5.0 to 7.5, with pH extremes of 3.5 to 9.8 possible.[21] Water temperatures typically range from 34 to 72 °F (1 to 22 °C). Warm summer temperatures and low flow rates are stressful on brook trout populations—especially larger fish.[22]

A potamodromous population of brook trout native to Lake Superior, which migrate into tributary rivers to spawn, are called "coasters".[23] Coasters tend to be larger than most other populations of brook trout, often reaching 6 to 7 lb (2.7 to 3.2 kg) in size.[24] Many coaster populations have been severely reduced by overfishing and habitat loss by the construction of hydroelectric power dams on Lake Superior tributaries. In Ontario and Michigan, efforts are underway to restore and recover coaster populations.[25]

When Europeans first settled in Eastern North America, semianadromous or sea-run brook trout, commonly called "salters", ranged from southern New Jersey, north throughout the Canadian maritime provinces, and west to Hudson Bay. Salters may spend up to three months at sea feeding on crustaceans, fish, and marine worms in the spring, not straying more than a few miles from the river mouth. The fish return to freshwater tributaries to spawn in the late summer or autumn. While in saltwater, salters gain a more silvery color, losing much of the distinctive markings seen in freshwater. However, within two weeks of returning to freshwater, they assume typical brook trout color and markings.[24]

Brook trout have a diverse diet that includes larval, pupal, and adult forms of aquatic insects (typically caddisflies, stoneflies, mayflies, and aquatic dipterans), and adult forms of terrestrial insects (typically ants, beetles, grasshoppers, and crickets) that fall into the water, crustaceans, frogs and other amphibians, molluscs, smaller fish, invertebrates, and even small aquatic mammals such as voles and sometimes other young brook trout[26]

The female constructs a depression in a location in the stream bed, sometimes referred to as a "redd", where groundwater percolates upward through the gravel. One or more males approach the female, fertilizing the eggs as the female expresses them. Most spawnings involve peripheral males, which directly influences the number of eggs that survive into adulthood. In general, the larger the number of peripheral males present, the more likely the eggs will be cannibalized.[27] The eggs are slightly denser than water. The female then buries the eggs in a small gravel mound; they hatch in 95 to 100 days.

The brook trout is a popular game fish with anglers, particularly fly fishermen.

Until it was displaced by introduced brown trout (1883) and rainbow trout (1875), the brook trout attracted the most attention of anglers from colonial times through the first 100 years of U.S. history. Sporting writers such as Genio Scott Fishing in American Waters (1869), Thaddeus Norris American Anglers Book (1864), Robert Barnwell Roosevelt Game Fish of North America (1864) and Charles Hallock The Fishing Tourist (1873) produced guides to the best-known brook trout waters in America.[30] As brook trout populations declined in the mid-19th century near urban areas, anglers flocked to the Adirondacks in upstate New York and the Rangeley lakes region in Maine to pursue brook trout.[30] In July 1916 on the Nipigon River in northern Ontario, an Ontario physician, John W. Cook, caught a 14.5 lb (6.6 kg) brook trout, which stands as the world record.[31]

Today, many anglers practice catch-and-release tactics to preserve remaining populations. Organizations such as Trout Unlimited have been at the forefront of efforts to institute air and water quality standards sufficient to protect the brook trout. Revenues derived from the sale of fishing licenses have been used to restore many sections of creeks and streams to brook trout habitat.[32]

The current world angling record brook trout was caught by Dr. W. J. Cook on the Nipigon River, Ontario, in July 1915. The 31 in (79 cm) trout weighed only 14.5 lb (6.6 kg) because, at the time of weighing, it was badly decomposed after 21 days in the bush without refrigeration.[33] A 29 in (74 cm) brook trout, caught in October 2006 in Manitoba, is not eligible for record status since it was released alive.[34] This trout weighed about 15.98 lb (7.25 kg) based on the accepted formula for calculating weight by measurements, and it currently stands as the record brook trout for Manitoba.[35]

Brook trout are also commercially raised in large numbers for food production, being sold for human consumption in both fresh and smoked forms.[36] Because of its dependence on pure water and a variety of aquatic and insect life forms, the brook trout is also used for scientific experimentation in assessing the effects of pollution and contaminated waters.

Brook trout are also raised commercially and sold to angling organizations or groups to stock their lakes or ponds. Some businesses hold a "U-fish license" where the public can fish at their lake or pond and buy the fish they catch.

Commercial fisheries do not commonly raise brook trout because they do not grow as fast as other types of fish.

Brook trout raised commercially are often kept in large circular tanks with a constant water flow going through them. This allows for a current to circulate through the tank and keep it clean, acting as a flush of water that takes fish waste with it. Some more elaborate systems operate on a re-circulation system where the water is filtered and reused.

The fish are typically fed a pelleted food consisting of 40–50% protein and 15% fat.[37] The fish food is usually made from fish oil, animal protein, plant protein and vitamins and minerals. The protein is often sourced from soy beans.[38]

Brook trout populations depend on cold, clear, well-oxygenated water of high purity. As early as the late 19th century, native brook trout in North America became extirpated from many watercourses as land development, forest clear-cutting, and industrialization took hold.[39] Streams and creeks that were polluted, dammed, or silted up often became too warm to hold native brook trout, and were colonized by transplanted smallmouth bass and perch or other introduced salmonids such as brown and rainbow trout. The brown trout, a species not native to North America, has replaced the brook trout in much of the brook trout's native water. If already stressed by overharvesting or by temperature, brook trout populations are very susceptible to damage by the introduction of exogenous species. Many lacustrine populations of brook trout have been extirpated by the introduction of other species, particularly percids, but sometimes other spiny-rayed fishes.[40]

In addition to chemical pollution and algae growth caused by runoff containing chemicals and fertilizers, air pollution has also been a significant factor in the disappearance of brook trout from their native habitats. In the U.S., acid rain caused by air pollution has resulted in pH levels too low to sustain brook trout in all but the highest headwaters of some Appalachian streams and creeks.[41] Brook trout populations across large parts of eastern Canada have been similarly challenged; a subspecies known as the aurora trout was extirpated from the wild by the effects of acid rain.[42] Today, in many parts of the range, efforts are underway to restore brook trout to those waters that once held native populations, stocking other trout species only in habitats that can no longer be recovered sufficiently to sustain brook trout populations.

Organizations such as Trout Unlimited and Trout Unlimited Canada[25] are partnering with other organizations such as the Southern Appalachian Brook Trout Foundation,[43] the Eastern Brook Trout Joint Venture,[44] and state, provincial, and federal agencies to undertake projects that restore native brook trout habitat and populations.

Although brook trout populations are under stress in their native range, they are considered an invasive species where they have been introduced outside their historic native range.[45][46][47] In the northern Rocky Mountains, non-native brook trout are considered a significant contributor to the decline or extirpation of native cutthroat trout (Oncorhynchus clarki) in headwater streams.[48] Non-native brook trout populations have been subject to eradication programs in efforts to preserve native species.[49][50] In Yellowstone National Park, anglers may take an unlimited number of non-native brook trout in some watersheds. In the Lamar River watershed, a mandatory kill regulation for any brook trout caught is in effect.[51] In Europe, introduced brook trout, once established, have had negative impacts on growth rates of native brown trout (S. trutta).[14]

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) The brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis) is a species of freshwater fish in the char genus Salvelinus of the salmon family Salmonidae. It is native to Eastern North America in the United States and Canada, but has been introduced elsewhere in North America, as well as to Iceland, Europe, and Asia. In parts of its range, it is also known as the eastern brook trout, speckled trout, brook charr, squaretail, brookie or mud trout, among others. A potamodromous population in Lake Superior, is known as coaster trout or, simply, as coasters. Anadromous populations which are found in coastal rivers from Long Island to Hudson Bay are sometimes referred to as salters. The brook trout is the state fish of nine U.S. states: Michigan, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Vermont, Virginia, and West Virginia, and the Provincial Fish of Nova Scotia in Canada.