fr

noms dans le fil d’Ariane

The Indigo Milk Cap (Lactarius indigo) is entirely blue to blue-gray, sometimes with greenish stains when old. When broken, it oozes indigo blue latex, which turns gradually greenish when exposed to air. It grows on the ground, typically in oak or pine woods. This mushroom has a broad geographic distribution, occurring throughout eastern North America and from Arizona to Mexico, but is most common along the Gulf Coast of the southeastern United States and in Mexico. It is generally considered edible, but reports vary regarding its desirability. (Lincoff 1981; Arora 1986, 1991; McNight and McNight 1987)

Lactarius indigo, és una espècie de fong comestible de la família Russulàcia. El seu basidiocarp presenta colors que van des del blau fosc en espècimens frescos al gris blavós pàl·lid en els més vells. La "llet", o làtex, que emana quan el teixit del bolet és tallat o trencat, una característica comuna a tots els membres del gènere Lactari, també és de color blau indi, però lentament es torna en verd en entrar en contacte amb l'aire. El Píleu sol mesurar entre 5 i 15 centímetres de diàmetre, i el estípit aconsegueix entre 2 i 8 centímetres de longitud i entre 1 i 2,5cm de grossor.

És una espècie d'àmplia distribució, i pot trobar-se en l'est d'Amèrica del Nord, l'est d'Àsia i a Centreamèrica.[3][4] L. indigo creix punt en boscos caducifolis com de coníferes, on forma micorizes amb roures i pins.

Va ser descrita per primera vegada en 1822 com Agaricus indigo pel micòleg nord-americà Lewis David de Schweinitz,i situada en el gènere Lactarius en 1838, pel suec Elias Magnus Fries.

Hesler i Smith, en el seu estudi de 1960 de les espècies nord-americanes de Lactarius, la defineixen com a espècie tipus de la subsección Caerulei, un grup caracteritzat pel seu làtex i el barret blaus.[5] El nom de l'espècie indigo significa, en llatí, "blau".[6] En anglès se li coneix amb diversos noms comuns com indigo milk cap —literalment "barret lletós indi"—, indigo Lactarius —"Lactarius indi"—, o blue Lactarius —"Lactarius blau"—.[7][8]Al centre de Mèxic, és conegut com añil, blau, fong blau, zuin, zuine. A Veracruz i en Pobla també se li coneix com quexque (que significa "blava").

Les espores són translúcidas (hialines), de forma el·líptica o gairebé esfèriques. Les seves dimensions oscil·len entre 7 i 9 µm de llarg entre 5,5 i 7,5 d'ample. Per mitjà del microscopi electrònic d'escombratge poden observar-se reticulaciones en la superfície de les espores. Els basidis sostenen quatre espores d'entre 37 i 45 µm de llarg i de 8 a 10 d'ample.[9] Els pleurocistidios tenen entre 40 i 56 µm de llarg i entre 6,4 i 8 d'amplada, i tenen forma de fus, amb l'àpex molt estret. Els cheilocistidios són abundants, i les seves dimensions oscil·len entre 40 i 45,6 µm de llarg i entre 5,6 i 7,2 d'ample.[10]

El característic color blau del cos fructífer i del làtex fa que aquesta espècie sigui fàcilment recognoscible. Existeixen altres Lactarius que presenten colors azulados:

Aquest bolet forma micorriza amb pins i roures, creixent sobretot durant la tardor. Es troba en gairebé tothom exceptuant Europa

El color blau de L. indigo es deu principalment al pigment químic anomenat azuleno. El compost, 1-estearoiloximetilen-4-metil-7-isopropenazuleno, extret i purificat del cos fructífer, és únic d'aquesta espècie.[12]

Lactarius indigo, és una espècie de fong comestible de la família Russulàcia. El seu basidiocarp presenta colors que van des del blau fosc en espècimens frescos al gris blavós pàl·lid en els més vells. La "llet", o làtex, que emana quan el teixit del bolet és tallat o trencat, una característica comuna a tots els membres del gènere Lactari, també és de color blau indi, però lentament es torna en verd en entrar en contacte amb l'aire. El Píleu sol mesurar entre 5 i 15 centímetres de diàmetre, i el estípit aconsegueix entre 2 i 8 centímetres de longitud i entre 1 i 2,5cm de grossor.

És una espècie d'àmplia distribució, i pot trobar-se en l'est d'Amèrica del Nord, l'est d'Àsia i a Centreamèrica. L. indigo creix punt en boscos caducifolis com de coníferes, on forma micorizes amb roures i pins.

Ryzec indigový (lat. Lactarius indigo) je jedlá houba z čeledi holubinkovité (Russulaceae). Je specifický tím, že celá plodnice je zbarvena do odstínů modré. Vyskytuje se především v Americe, ale také v Číně a Indii. I přes svoje neobvyklé zbarvení se jedná o jedlý a chutný druh.

Byl nejdříve popsán v roce 1822 americkým mykologem Lewisem Davidem de Schweinitzem, ale vědecky klasifikován byl až v roce 1838 švédským botanikem a mykologem Eliasem Magnusem Friesem.

Ryzec indigový se vyskytuje především v listnatých, ale i jehličnatých lesích, zejména pod borovicemi (Pinus). Nejčastěji na americkém kontinentě (především v Mexiku a Guatemale), také byl nalezen i v Číně a Indii.

Přestože se tento ryzec vyskytuje v teplých oblastech, obsahuje v průměru 950 mg/g vody. „Stavebními kameny“ jsou jako u každé houby vláknina, proteiny a kyselina stearová. Modré zbarvení způsobuje organické barvivo azulen, jedno z mála modrých barviv u hub. Dalšími barvivy v ryzci indigovém jsou sesquiterpen, matricin a chamuzelén, z nichž se již zmíněný azulen tvoří.

Ryzec indigový (lat. Lactarius indigo) je jedlá houba z čeledi holubinkovité (Russulaceae). Je specifický tím, že celá plodnice je zbarvena do odstínů modré. Vyskytuje se především v Americe, ale také v Číně a Indii. I přes svoje neobvyklé zbarvení se jedná o jedlý a chutný druh.

Byl nejdříve popsán v roce 1822 americkým mykologem Lewisem Davidem de Schweinitzem, ale vědecky klasifikován byl až v roce 1838 švédským botanikem a mykologem Eliasem Magnusem Friesem.

Der Indigo-Reizker (Lactarius indigo) ist eine Pilzart aus der Familie der Täublingsverwandten. Der Milchling ist im östlichen Nordamerika, Zentralamerika und in Ostasien weit verbreitet. Aus Europa sind bisher nur Vorkommen in Südfrankreich bekannt.[1] Der Pilz wächst sowohl in Laub- als auch im Nadelwäldern, in denen er Mykorrhizen mit diversen Baumarten bildet. Die Farbe reicht von Dunkelblau bei jungen Exemplaren bis zu einem fahlen Blaugrau bei älteren Fruchtkörpern. Die bei Verletzung des Fruchtfleisches austretende, ebenso indigoblaue Milch verfärbt sich bei Luftkontakt grünlich. Der Hut misst typischerweise 5 bis 15 cm im Durchmesser, der Stiel ist 2 bis 8 cm hoch und 1 bis 2,5 cm dick. Der Pilz ist essbar und wird auf Bauernmärkten in Mexiko, Guatemala und China angeboten.

Der Hut des Fruchtkörpers ist 5-15 cm breit, zunächst konvex und entwickelt allmählich eine flache Trichterform. Im Alter wird er sogar noch stärker eingedrückt, wobei sich der Rand aufwärts wölbt. Im jungen Zustand ist der Hutrand nach innen eingerollt, entfaltet und hebt sich aber, wenn der Pilz wächst. Bei jungen Exemplaren ist der Hut indigoblau, wird aber bei alten Pilzen graublau oder silberblau, manchmal auch mit grünlichen Flecken. Er ist häufig ringförmig gezont mit dunkelblauen Flecken zum Hutrand hin. Die Kappen junger Exemplare haben eine klebrige Oberfläche.

Das Fleisch ist blass bläulich und färbt sich bei Kontakt mit Luft langsam grün; sein Geschmack ist mild bis leicht bitter. Das Fleisch des gesamten Pilzes ist spröde und der Stiel bricht sauber durch, wenn man ihn biegt. Die aus Verletzungen austretende Milch ist ebenfalls indigoblau und färbt den Anschnitt grünlich; wie auch das Fleisch schmeckt sie mild. Lactarius indigo ist dafür bekannt, nicht so viel Milch zu produzieren, wie andere Lactarius-Arten[2] und insbesondere alte Exemplare können derart ausgetrocknet sein, dass sie gar keine Milch mehr absondern.[3]

Die Lamellen sind am Stiel angewachsen oder leicht bogig und stehen dicht zusammengedrängt. Ihre Farbe reicht von indigoblau im jungen Stadium bis zu einem fahlen graublau im Alter, bei Beschädigung treten grüne Flecken auf. Der Stiel ist 2-6 cm hoch und 1.2,5 cm dick, der Durchmesser ist über den gesamten Stiel gleich oder manchmal an der Basis etwas geringer. Der Stiel ist gleichfalls indigo- bis silber- und graublau gefärbt. Das innere des Stiel ist zunächst fest und kompakt, im Alter wird er jedoch oft hohl. Wie der Hut ist er zu Anfang klebrig oder schleimig, trocknet aber später ab. Normalerweise ist der Hut zentral am Stiel angewachsen, kann aber auch dezentral verschoben sein. Die Fruchtkörper des Indigo-Reizkers haben keinen besonderen Geruch.

Lactarius indigo var. diminutivus (der "Kleine Indigo-Reizker", engl.: smaller indigo milk cap), eine kleinere Unterart mit Hüten von 3-7 cm Durchmesser und Stielhöhen von 1,5-4 cm, wird häufig in Virginia gefunden.[4] Helser und Smith, die die Unterart als erste beschrieben, bemerken dazu als typischen Lebensraum: "entlang der Ränder von schlammigen Gräben unter Gräsern und Kräutern mit Weihrauch-Kiefern in der Nähe (along [the] sides of a muddy ditch under grasses and weeds, [with] loblolly pine nearby)."

Der Sporenabdruck ist cremefarben bis gelb. Unter dem Lichtmikroskop betrachtet, sind die Sporen durchsichtig (hyalin), sie sind elliptisch bis beinahe rund mit amyloiden Warzen und haben Dimensionen von etwa 7–9 mal 5,5–7,5 µm. Die Rasterelektronenmikroskopie zeigt Runzelkörner auf der Oberfläche der Sporen. Das Hymenium ist das Sporen produzierende Gewebe des Fruchtkörpers und besteht aus Hyphen, die sich zu den Lamellen hin ausdehnen. Im Hymenium wurden verschiedene Zellarten gefunden und die Zellen weisen mikroskopische Eigenschaften auf, anhand derer man Arten identifizieren oder unterscheiden kann, sofern die makroskopischen Merkmale nicht eindeutig sind. Die sporentragenden Zellen, die Basidien, tragen jeweils vier Sporen und messen 37–45 µm Länge mal 8–10 µm Breite.[5] Sogenannte Zystiden sind die Endzellen der Hyphen im Hymenium, die keine Sporen produzieren, sondern der Sporenverbreitung dienen und für die nötige Feuchtigkeit rund um sich entwickelnde Sporen sorgen. Die Pleurozystiden sind Zystiden, die auf den Lamellen selbst gefunden werden; sie messen 40–56 mal 6,4–8 µm sind grob spindelförmig und weisen eingeschnürte Spitzen auf. Die Cheilozystiden auf den Kanten der Lamellen sind häufig und weisen Abmessungen von 40–45,6 mal 5,6–7,2 µm auf.[6]

Der Indigo-Reizker ist im südlichen und östlichen Nordamerika verbreitet und kommt häufig entlang des Golfs von Mexiko und in Mexiko vor. Seine Verbreitung in den Appalachen der Vereinigten Staaten wurde mit "gelegentlich bis lokal häufig (occasional to locally common)" beschrieben.[7] Arora schreibt, dass die Art in den USA bei Gelb-Kiefern in Arizona gefunden wird, jedoch in den kalifornischen Gelb-Kiefer-Wäldern fehlt.[8] Die Art wurde auch in Eichenwäldern in China, Indien, Bhutan, Kolumbien, Guatemala und Costa Rica gefunden. Eine Studie zum saisonalen Auftreten von L. indigo in den subtropischen Wäldern von Xalapa/Mexiko zeigte, dass die Maximalproduktion von Fruchtkörpern mit der Regenzeit von Juni bis September zusammenfällt.[9]

L. indigo bildet Mykorrhizen und geht daher mit den Wurzeln verschiedener Baumarten eine Symbiose ein, wobei der Pilz Mineralien und Aminosäuren aus dem Boden gegen fixierten Kohlenstoff mit dem Wirtsbaum austauscht. Die unterirdischen Hyphen des Pilzes spannen ein Geflecht von Zellgewebe, das sogenannte Ektomykorrhizum, um die Wurzeln des Baumes – eine enge gegenseitige Beziehung, die insbesondere für den Wirt von Vorteil ist, da der Pilz Enzyme produziert, die organische Verbindungen mineralisieren und so den Transport von Nährstoffen zum Baum ermöglichen.

Aufgrund ihrer engen Symbiose mit Bäumen finden sich die Fruchtkörper des Indigo-Reizkers typischerweise am Boden, verstreut oder in Gruppen, sowohl in Laub- als auch in Nadelwäldern. Man findet den Pilz auch häufig in Flussauen, die kürzlich überschwemmt wurden.[3] In Mexiko wurden Gemeinschaften mit Mexikanischer Erle (Alnus jorullensis), Amerikanischer Hainbuche, Virginischer Hopfenbuche (Ostrya virginiana) und Amberbäumen beobachtet,[6] während sich der Pilz in Guatemala an Pinus pseudostrobus und andere Kiefern- und auch Eichenarten hält. In Costa Rica geht der Indigo-Reizker Verbindungen mit verschiedenen Eichenarten ein. Unter kontrollierten Laborbedingungen konnte gezeigt werden, dass L. indigo Verbindungen mit den neotropischen Kiefernarten Mexikanische Weymouth-Kiefer, Pinus hartwegii, Pinus oocarpa, Pinus pseudostrobus und auch mit eurasischen Arten wie Aleppokiefer, Schwarzkiefer, See-Kiefer und Waldkiefer eingeht.[10]

Der Indigo-Reizker ist als essbare Art bekannt, jedoch unterscheiden sich die Meinungen über seinen Speisewert: So nennt der amerikanische Mykologe David Arora ihn „vorzüglich (superior edible)“,[11] während ein Bestimmungsbuch für Pilze in Kansas ihn mit „mittlerer Qualität (mediocre in quality)“ bewertet.[12] Er kann leicht bitter oder pfeffrig schmecken und hat eine grobe, körnige Textur. Das feste Fruchtfleisch wird am besten zubereitet, indem man den Pilz in dünne Scheiben schneidet. Beim Kochen verschwindet die blaue Farbe und der Pilz wird grau. Wegen des körnigen Fleisches ist der Pilz nicht leicht zu trocknen. Exemplare mit besonders reichlichem Milchgehalt eignen sich zur Färbung von Marinaden.

In Mexiko werden wild wachsende Indigo-Reizker typischerweise von Juni bis November für den Verkauf gesammelt, wobei sie als Speisepilz zweiter Wahl angesehen werden.[13] Der Indigo-Reizker wird auch in Guatemala von Mai bis Oktober auf Märkten angeboten. Er ist eine von 13 Lactarius-Sorten, die in Yunnan im Südwesten Chinas verkauft werden.

Eine chemische Analyse von mexikanischen Exemplaren zeigte, dass L. indigo 95,1 % Feuchtigkeit, 4,3 mg Fett pro Gramm Masse und 13,4 mg Protein enthält. Es sind 18,7 mg Ballaststoffe enthalten, viel mehr als z. B. im Zuchtchampignon, der nur 6,6 mg enthält. Im Vergleich zu drei anderen wild vorkommenden Pilzarten, die auch in dieser Studie untersucht wurden (Perlpilz, Boletus frostii und Ramaria flava), hatte der Indigo-Reizker mit 32,1 mg/g den höchsten Gehalt an gesättigten Fettsäuren, einschließlich Stearinsäure – etwas mehr als die Hälfte des Gesamtgehaltes an freien Fettsäuren.[14]

Die blaue Farbe des Indigo-Reizkers wird durch das Azulen-Derivat (7-Isopropenyl-4-methylazulen-1-yl)-methylstearat hervorgerufen. Das Molekül kommt nur im Indigo-Reizker vor, ist aber ähnlich einer Verbindung, die im Edel-Reizker gefunden wurde.[15]

1822 von dem amerikanischen Mykologen Lewis David von Schweinitz als Agaricus indigo beschrieben,[16] wurde die Art 1838 von dem Schweden Elias Magnus Fries der Gattung Lactarius zugeordnet. Der deutsche Botaniker Otto Kuntze nannte die Art in seiner Schrift Revisio Generum Plantarum von 1891 Lactifluus indigo,[17] jedoch wurde diese Namensänderung nicht von anderen Autoren aufgegriffen. In ihrer Studie zu den nordamerikanischen Arten von Lactarius von 1960 definierten Hesler und Smith L. indigo als Typspezies der Unterteilung Caerulei, einer Gruppe, die sich durch blaue Milch und einen klebrigen, blauen Hut auszeichnet.[18] 1979 zogen sie ihre Meinung zu den Unterteilungen der Art Lactarius zurück und ordneten L. indigo stattdessen in die Untergattung Lactarius ein, basierend auf der Farbe der Milch und deren Farbänderung, die bei Kontakt mit Luft beobachtet werden konnte.[19] Sie erklären dazu:[20]

"Die allmähliche Entwicklung von blauer zu violetter Pigmentierung, wenn man sich von Art zu Art bewegt, ist ein interessantes Phänomen, das weiterer Forschung bedarf. Der Höhepunkt wird bei L. indigo erreicht, der durch und durch blau ist. L. chelidonium und seine Abarten chelidonioides, L. paradoxus, und L. hemicyaneus können als Meilensteine auf dem Weg zu L. indigo angesehen werden. (The gradual development of blue to violet pigmentation as one progresses from species to species is an interesting phenomenon deserving further study. The climax is reached in L. indigo which is blue throughout. L. chelidonium and its variety chelidonioides, L. paradoxus, and L. hemicyaneus may be considered as mileposts along the road to L. indigo.)"

Der Artname indigo bezieht sich auf die lateinische Bezeichnung für "indigoblau".

Die charakteristische blaue Farbe des Fruchtkörpers und der Milch machen diese Art leicht bestimmbar. Andere Arten von Lactarius mit blauer Farbe umfassen L. paradoxus aus dem östlichen Nordamerika, der im Jungstadium einen graublauen Hut hat, aber rotbraune bis purpurne Lamellen und Milch aufweist. L. chelidonium hat einen gelblichen bis graublauen Hut und gelbbraune Milch. L. quieticolor hat einen rötlichgrauen bis zimtbraunen Hut mit blauem Fleisch und orangefarbenes Fleisch in der Stielbasis.[1][11] Obwohl die blaue Färbung des L. indigo als selten innerhalb der Gattung Lactarius gilt, wurden 2007 fünf neue Arten mit bläuender Milch oder bläuendem Fleisch auf der Malaiischen Halbinsel gefunden: Lactarius cyanescens, L. lazulinus, L. mirabilis und zwei noch unbenannte Arten.

Der Indigo-Reizker (Lactarius indigo) ist eine Pilzart aus der Familie der Täublingsverwandten. Der Milchling ist im östlichen Nordamerika, Zentralamerika und in Ostasien weit verbreitet. Aus Europa sind bisher nur Vorkommen in Südfrankreich bekannt. Der Pilz wächst sowohl in Laub- als auch im Nadelwäldern, in denen er Mykorrhizen mit diversen Baumarten bildet. Die Farbe reicht von Dunkelblau bei jungen Exemplaren bis zu einem fahlen Blaugrau bei älteren Fruchtkörpern. Die bei Verletzung des Fruchtfleisches austretende, ebenso indigoblaue Milch verfärbt sich bei Luftkontakt grünlich. Der Hut misst typischerweise 5 bis 15 cm im Durchmesser, der Stiel ist 2 bis 8 cm hoch und 1 bis 2,5 cm dick. Der Pilz ist essbar und wird auf Bauernmärkten in Mexiko, Guatemala und China angeboten.

Lactarius indigo, commonly known as the indigo milk cap, indigo milky, the indigo (or blue) lactarius, or the blue milk mushroom, is a species of agaric fungus in the family Russulaceae. It is a widely distributed species, growing naturally in eastern North America, East Asia, and Central America; it has also been reported in southern France. L. indigo grows on the ground in both deciduous and coniferous forests, where it forms mycorrhizal associations with a broad range of trees. The fruit body color ranges from dark blue in fresh specimens to pale blue-gray in older ones. The milk, or latex, that oozes when the mushroom tissue is cut or broken — a feature common to all members of the genus Lactarius — is also indigo blue, but slowly turns green upon exposure to air. The cap has a diameter of 5–15 cm (2–6 in), and the stem is 2–8 cm (0.8–3 in) tall and 1–2.5 cm (0.4–1.0 in) thick. It is an edible mushroom, and is sold in rural markets in China, Guatemala, and Mexico. In Honduras, the mushroom is called a chora, and is generally eaten with egg; generally as a side dish for a bigger meal.

Originally described in 1822 as Agaricus indigo by American mycologist Lewis David de Schweinitz,[3] the species was later transferred to the genus Lactarius in 1838 by the Swede Elias Magnus Fries.[4] German botanist Otto Kuntze called it Lactifluus indigo in his 1891 treatise Revisio Generum Plantarum,[2] but the suggested name change was not adopted by others. Hesler and Smith, in their 1960 study of North American species of Lactarius, defined L. indigo as the type species of subsection Caerulei, a group characterized by blue latex and a sticky, blue cap.[5] In 1979, they revised their opinions on the organization of subdivisions in the genus Lactarius, and instead placed L. indigo in subgenus Lactarius based on the color of latex and the subsequent color changes observed after exposure to air.[6] As they explained:

The gradual development of blue to violet pigmentation as one progresses from species to species is an interesting phenomenon deserving further study. The climax is reached in L. indigo which is blue throughout. L. chelidonium and its variety chelidonioides, L. paradoxus, and L. hemicyaneus may be considered as mileposts along the road to L. indigo.[7]

The specific epithet indigo is derived from the Latin word meaning "indigo blue".[8] Its names in the English vernacular include the "indigo milk cap",[9] the "indigo Lactarius",[8] the "blue milk mushroom",[10] and the "blue Lactarius".[11] In central Mexico, it is known as añil, azul, hongo azul, zuin, and zuine; it is also called quexque (meaning "blue") in Veracruz and Puebla.[12]

Like many other mushrooms, L. indigo develops from a nodule that forms within the underground mycelium, a mass of threadlike fungal cells called hyphae that make up the bulk of the organism. Under appropriate environmental conditions of temperature, humidity, and nutrient availability, the visible reproductive structures (fruit bodies) are formed. The cap of the fruit body, measuring between 5–15 cm (2.0–5.9 in) in diameter, is initially convex and later develops a central depression; in age it becomes even more deeply depressed, becoming somewhat funnel-shaped as the edge of the cap lifts upward.[13] The margin of the cap is rolled inwards when young, but unrolls and elevates as it matures. The cap surface is indigo blue when fresh, but fades to a paler grayish- or silvery-blue, sometimes with greenish splotches. It is often zonate: marked with concentric lines that form alternating pale and darker zones, and the cap may have dark blue spots, especially towards the edge. Young caps are sticky to the touch.[14]

The flesh is pallid to bluish in color, slowly turning greenish after being exposed to air; its taste is mild to slightly acrid. The flesh of the entire mushroom is brittle, and the stem, if bent sufficiently, will snap open cleanly.[15] The latex exuded from injured tissue is indigo blue, and stains the wounded tissue greenish; like the flesh, the latex has a mild taste.[8] Lactarius indigo is noted for not producing as much latex as other Lactarius species,[16] and older specimens in particular may be too dried out to produce any latex.[17]

The gills of the mushroom range from adnate (squarely attached to the stem) to slightly decurrent (running down the length of the stem), and crowded close together. Their color is an indigo blue, becoming paler with age or staining green with damage. The stem is 2–6 cm (0.8–2.4 in) tall by 1–2.5 cm (0.4–1.0 in) thick, and the same diameter throughout or sometimes narrowed at base. Its color is indigo blue to silvery- or grayish blue. The interior of the stem is solid and firm initially, but develops a hollow with age.[9] Like the cap, it is initially sticky or slimy to the touch when young, but soon dries out.[18] Its attachment to the cap is usually in a central position, although it may also be off-center.[19] Fruit bodies of L. indigo have no distinguishable odor.[20]

L. indigo var. diminutivus (the "smaller indigo milk cap") is a smaller variant of the mushroom, with a cap diameter between 3–7 cm (1.2–2.8 in), and a stem 1.5–4.0 cm (0.6–1.6 in) long and 0.3–1.0 cm (0.1–0.4 in) thick.[21] It is often seen in Virginia.[20] Hesler and Smith, who first described the variant based on specimens found in Brazoria County, Texas, described its typical habitat as "along [the] sides of a muddy ditch under grasses and weeds, [with] loblolly pine nearby".[22]

When viewed in mass, as in a spore print, the spores appear cream to yellow colored.[8][9] Viewed with a light microscope, the spores are translucent (hyaline), elliptical to nearly spherical in shape, with amyloid warts, and have dimensions of 7–9 by 5.5–7.5 μm.[8] Scanning electron microscopy reveals reticulations on the spore surface.[12] The hymenium is the spore-producing tissue layer of the fruit body, and consists of hyphae that extend into the gills and terminate as end cells. Various cell types can be observed in the hymenium, and the cells have microscopic characteristics that may be used to help identify or distinguish species in cases where the macroscopic characters may be ambiguous. The spore-bearing cells, the basidia, are four-spored and measure 37–45 μm long by 8–10 μm wide at the thickest point.[23] Cystidia are terminal cells of hyphae in the hymenium which do not produce spores, and function in aiding spore dispersal, and maintaining favorable humidity around developing spores.[24] The pleurocystidia are cystidia that are found on the face of a gill; they are 40–56 by 6.4–8 μm, roughly spindle-shaped, and have a constricted apex. The cheilocystidia—located on the edge of a gill—are abundant, and are 40.0–45.6 by 5.6–7.2 μm.[12]

The characteristic blue color of the fruiting body and the latex make this species easily recognizable. Other Lactarius species with some blue color include the "silver-blue milky" (L. paradoxus), found in eastern North America,[20] which has a grayish-blue cap when young, but it has reddish-brown to purple-brown latex and gills. L. chelidonium has a yellowish to dingy yellow-brown to bluish-gray cap and yellowish to brown latex. L. quieticolor has blue-colored flesh in the cap and orange to red-orange flesh in the base of the stem.[9] Although the blue discoloration of L. indigo is thought to be rare in the genus Lactarius, in 2007 five new species were reported from Peninsular Malaysia with bluing latex or flesh, including L. cyanescens, L. lazulinus, L. mirabilis, and two species still unnamed.[25]

Although L. indigo is a well-known edible species, opinions vary on its desirability. For example, American mycologist David Arora considers it a "superior edible",[9] while a field guide on Kansas fungi rates it as "mediocre in quality".[26] It may have a slightly bitter,[27] or peppery taste,[28] and has a coarse, grainy texture.[8][26] The firm flesh is best prepared by cutting the mushroom in thin slices. The blue color disappears with cooking, and the mushroom becomes grayish. Because of the granular texture of the flesh, it does not lend itself well to drying. Specimens producing copious quantities of milk may be used to add color to marinades.[29]

In Mexico, individuals harvest the wild mushrooms for sale at farmers' markets, typically from June to November;[12] they are considered a "second class" species for consumption.[30] L. indigo is also sold in Guatemalan markets from May to October.[31] It is one of 13 Lactarius species sold at rural markets in Yunnan in southwestern China.[32]

A chemical analysis of Mexican specimens has shown L. indigo to contain moisture at 951 mg/g of mushroom, fat at 4.3 mg/g, protein at 13.4 mg/g, and dietary fiber at 18.7 mg/g, much higher in comparison to the common button mushroom, which contains 6.6 mg/g. Compared to three other wild edible mushroom species also tested in the study (Amanita rubescens, Boletus frostii, and Ramaria flava), L. indigo contained the highest saturated fatty acids content, including stearic acid with 32.1 mg/g—slightly over half of the total free fatty acid content.[33]

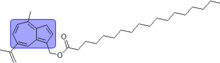

The blue color of L. indigo is due to (7-isopropenyl-4-methylazulen-1-yl)methyl stearate, an organic derivative of azulene, which is biosynthesised from a sesquiterpene very similar to matricin, the precursor for chamazulene. It is unique to this species, but similar to a compound found in L. deliciosus.[34]

Lactarius indigo is distributed throughout southern and eastern North America but is most common along the Gulf Coast, Mexico, and Guatemala. Its frequency of appearance in the Appalachian Mountains of the United States has been described as "occasional to locally common".[8] Mycologist David Arora notes that in the United States, the species is found with ponderosa pine in Arizona, but is absent in California's ponderosa pine forests.[35] It has also been collected from China,[32] India,[36][37] Guatemala,[38] Costa Rica (in forests dominated by oak),[39] and as its southernmost distribution in the Humboldt oak cloud forests of Colombia.[40] In Europe, it has so far only been found in southern France.[41] A study on the seasonal appearance of fruiting bodies in the subtropical forests of Xalapa, Mexico, confirmed that maximal production coincided with the rainy season between June and September.[42]

L. indigo is a mycorrhizal fungus, and as such, establishes a mutualistic relationship with the roots of certain trees ("hosts"), in which the fungi exchange minerals and amino acids extracted from the soil for fixed carbon from the host. The subterranean hyphae of the fungus grow a sheath of tissue around the rootlets of a broad range of tree species, forming so-called ectomycorrhizae—an intimate association that is especially beneficial to the host, as the fungus produces enzymes that mineralize organic compounds and facilitate the transfer of nutrients to the tree.[43]

Reflecting their close relationships with trees, the fruit bodies of L. indigo are typically found growing on the ground, scattered or in groups, in both deciduous and coniferous forests.[44] They are also commonly found in floodplain areas that have been recently submerged.[17] In Mexico, associations have been noted with Mexican alder, American Hornbeam, American Hophornbeam, and Liquidambar macrophylla,[12] while in Guatemala the mushroom associates with smooth-bark Mexican pine and other pine and oak species.[38] In Costa Rica, the species forms associations with several native oaks of the genus Quercus.[45] Under controlled laboratory conditions, L. indigo was shown to be able to form ectomycorrhizal associations with the neotropical pine species Mexican white pine, Hartweg's pine, Mexican yellow pine, smooth-bark Mexican pine,[31] and the Eurasian pines Aleppo pine, European black pine, maritime pine, and Scots pine.[46]

Lactarius indigo, commonly known as the indigo milk cap, indigo milky, the indigo (or blue) lactarius, or the blue milk mushroom, is a species of agaric fungus in the family Russulaceae. It is a widely distributed species, growing naturally in eastern North America, East Asia, and Central America; it has also been reported in southern France. L. indigo grows on the ground in both deciduous and coniferous forests, where it forms mycorrhizal associations with a broad range of trees. The fruit body color ranges from dark blue in fresh specimens to pale blue-gray in older ones. The milk, or latex, that oozes when the mushroom tissue is cut or broken — a feature common to all members of the genus Lactarius — is also indigo blue, but slowly turns green upon exposure to air. The cap has a diameter of 5–15 cm (2–6 in), and the stem is 2–8 cm (0.8–3 in) tall and 1–2.5 cm (0.4–1.0 in) thick. It is an edible mushroom, and is sold in rural markets in China, Guatemala, and Mexico. In Honduras, the mushroom is called a chora, and is generally eaten with egg; generally as a side dish for a bigger meal.

Lactarius indigo, ofte konata kiel la indiga lakta kaskedo, la indiga (aŭ blua) laktario aŭ la blulakta agariko, estas specio de agarika fungo en la familio Russulaceae. Ĝenerale distribuita specio, ĝi kreskas nature en orienta Nord-Ameriko, Orienta Azio kaj Centr-Ameriko; ĝi estis raportita ankaŭ en la suda Francio. L. indigo kreskas sur la tero en kaj falfoliaj kaj koniferaj arbaroj, kie ĝi formas mikorizajn asociojn kun larĝa gamo de arboj. La fruktaj korpaj koloraj gamoj de malluma bluo en freŝaj specimenoj paliĝas al blua-griza en plej malnovaj specimenoj. La lakto aŭ latex, kiu eliĝadas kiam la agarika histo estas tranĉita aŭ rompita — ĉefaĵo ofta al ĉiuj membroj de la Lactarius-genro — estas ankaŭ indige blua, sed malrapide turniĝas al verda je ekspono al aero. La kaskedo havas diametron de 5 al 15 cm kaj la tigo estas 2 al 8 cm alta kaj 1 al 2.5 cm dika. Ĝi estas manĝebla agariko kaj estas vendita en kamparaj merkatoj en Ĉinio, Gvatemalo kaj Meksiko.

Origine priskribita en 1822 kiel Agaricus indigo de la usona mikologo Lewis David de Schweinitz,[1] la specio estis poste translokigita al la genro Lactarius en 1838 fare de la svedo Elias Magnus Frajoj.[2] Germana botanikisto Otto Kuntze nomis ĝin Lactifluus indigo en sia traktato de 1891 Revisio Generum Plantarum,[3] sed la sugestita nomoŝanĝo ne estis adoptita de aliaj. Hesler kaj Smith en sia studo de 1960 pri nord-amerikaj specioj de Lactarius, difinis L. indigo kiel la tipa specio de subsekcio Caerulei, grupo karakterizita de blua latex kaj algluiĝa, blua kaskedo.[4] En 1979, ili reviziis siajn opiniojn pri la organizo de subdividoj en la genro Lactarius kaj male lokis L. Indigo en subgenron Lactarius bazite sur la koloro de latex kaj la posta kolorŝanĝo observita post malkovro al aero.[5] Kiel ili klarigis:

La specifa epiteto indigo estas derivita de la latina vorto signifanta "indiga blua".[7] Ĝiaj nomoj en la angla vulgara inkluzivas la "indiga lakta kaskedo", la "indiga laktario", la "blulakta agariko" kaj la "blua laktario".[8][7][9][10] En centra Meksiko, ĝi estas konata kiel añil, azul, hongo azul, zuin kaj zuine; ĝi estas ankaŭ nomita quexque ([KEKSke], signifanta "bluon") en Veracruz kaj Puebla.[11]

Ŝatas multaj aliaj agarikoj, L. Indigo evoluigas de nodule aŭ pinhead, kiu formas ene de la subtera mycelium, amaso de threadlike fungal ĉeloj vokita hyphae kiu faras supre la grandecon de la organismo. Sub konvenaj ekologiaj kondiĉoj de temperaturo, humideco kaj nutraĵa havebleco, la videbla reproduktiĝa struktura (frukto korpoj) estas formita. La kaskedo de la frukta korpo, mezuranta inter Ŝablono:Convert/and cm (2.0 kaj 5.9 je) en diametro, estas komence malkava kaj poste evoluigas centran melankolion; en aĝo ĝi fariĝas eĉ pli profunde deprimita, fariĝanta iom funelo-formita kiel la rando de la kaskedo levas supren.[12] La marĝeno de la kaskedo estas rulita inwards kiam juna, sed disvolvas kaj levas kiel ĝi maturigas. La kaskeda surfaco estas indigo bluo kiam freŝa, sed senkoloriĝas al pli pala grayish- aŭ silvery-bluo, foje kun greenish splotches. Ĝi estas ofte zonate: markita kun samcentraj linioj kiu formas alternanta palajn kaj pli mallumajn zonojn kaj la kaskedo povas havi mallumajn bluajn punktojn, precipe al la rando. Junaj kaskedoj estas algluiĝaj al la tuŝo.[13]

La karno estas pallid al bluish en koloro, malrapide turnanta greenish post kiam estanta malkovrita al aero; ĝia gusto estas milda al iomete acrid. La karno de la tuta agariko estas fragila kaj la tigo, se fleksita sufiĉe, klakos malferman cleanly.[14] La latex eligita de vundita histon estas indigo bluo kaj makulas la vundita histon greenish; kiel la karno, la latex havas mildan guston.[7] Lactarius indigo estas notita por ne produktanta tiom multe latex kiel alia Lactarius specio kaj pli malnovaj specimenoj en aparta povas esti tro elsekigita produkti ajna latex.[15][16]

La gills de la agarika gamo de adnate (squarely alligita al la tigo) al iomete decurrent (kurado malsupren la longeco de la tigo) kaj amasiĝita egale kune. Ilia koloro estas indigo bluo, fariĝanta pli pala kun aĝo aŭ makulanta legomon kun difekto. La tigo estas Ŝablono:Convert/– cm (0.8–2.4 en) alta de Ŝablono:Convert/– cm (0.4–1.0 en) dika kaj la sama diametro dum aŭ foje mallarĝigita ĉe bazo. Ĝia koloro estas indigo bluo al silvery- aŭ grayish bluo. La interno de la tigo estas solida kaj firmao komence, sed evoluigas kavan kun aĝo.[8] Kiel la kaskedo, ĝi estas komence algluiĝa aŭ slimy al la tuŝo kiam juna, sed baldaŭ elsekigas.[17] Ĝia alligitaĵo al la kaskedo estas kutime en centra pozicio, kvankam ĝi ankaŭ povas esti de-centro.[18] Fruktaj korpoj de L. Indigo havas ne distinguishable odor.[19]

L. Indigo var. Diminutivus (la "pli malgranda indigo lakta kaskedo") estas pli malgranda varianto de la agariko, kun kaskeda diametro inter Ŝablono:Convert/and cm (1.2 kaj 2.8 je) kaj tigo Ŝablono:Convert/– cm (0.6–1.6 en) longa kaj Ŝablono:Convert/– cm (0.1–0.4 en) dika.[20] Ĝi estas ofte vidita en Virginio.[19] Hesler kaj Smith, kiu unue priskribis la varianton bazita sur specimenoj trovita en Brazoria Gubernio, Teksaso, priskribis ĝian tipan vivejon kiel "laŭ [la] flankoj de kota fosaĵo sub herboj kaj trudherboj, [kun] loblolly pine proksime".[21]

Kiam vidita en amaso, kiel en spora gravuraĵo, la sporoj aperas kremo al flava kolorita.[7][8] Vidita kun luma mikroskopo, la sporoj estas diafanaj (hyaline), elipsa al preskaŭ sfera en formo, kun amyloid verukoj kaj havi dimensiojn de 7–9 de 5.5–7.5 µm.[7] Skananta elektronon microscopy rivelas reticulations sur la spora surfaco.[11] La hymenium estas la sporo-produktanta histan tavolon de la frukta korpo kaj konsistas de hyphae kiu etendas en la gills kaj fini kiel finaj ĉeloj. Diversaj ĉelaj tipoj povas esti observita en la hymenium kaj la ĉeloj havas mikroskopajn karakterizaĵojn kiu povas esti uzita helpi identigi aŭ distingi specion en kazoj kie la macroscopic karakteroj povas esti ambiguaj. La sporo-portanta ĉelojn, la basidia, estas kvar-spored kaj mezuro 37–45 µm longe de 8–10 µm larĝe ĉe la plej dika punkto.[22] Cystidia estas mortaj ĉeloj de hyphae en la hymenium kiu ne produktas sporojn kaj funkcio en helpanta sporan disvastigon kaj daŭriganta favoran humidecon ĉirkaŭ evoluiganta sporojn.[23] La pleurocystidia estas cystidia kiu estas trovita sur la vizaĝo de gill; ili estas 40–56 de 6.4–8 µm, malglate konuklo-formita kaj havas limigita apogeon. La cheilocystidia—troviĝita sur la rando de gill—estas abunda kaj estas 40.0–45.6 de 5.6–7.2 µm.[11]

La aparta blua koloro de la fruiting korpo kaj la latex faro ĉi tiu specio facile rekonebla. Alia Lactarius specio kun iu blua koloro inkluzivas la "arĝentan-blua milky" (L. Paradoxus), trovita en orienta Nord-Ameriko, kiu havas grayish-blua kaskedo kiam juna, sed ĝi havas ruĝetan-bruna al purpura-bruna latex kaj gills.[19] L. Chelidonium havas flavecan al dingy flava-bruna al bluish-griza kaskedo kaj flaveca al bruna latex. L. Quieticolor havas bluan-kolorita karnon en la kaskedo kaj oranĝa al ruĝa-oranĝa karno en la bazo de la tigo.[8] Kvankam la blua discoloration de L. Indigo estas pensita esti malofta en la genus Lactarius, en 2007 kvin nova specio estis raportita de Peninsular Malajzio kun bluing latex aŭ karno, inkluzivanta L. Cyanescens, L. Lazulinus, L. Mirabilis kaj du specioj ankoraŭ nenomita.[24]

Kvankam L. Indigo estas puto-sciita manĝeblan specion, opinioj varias sur ĝia desirability. Ekzemple, amerika mycologist David Arora konsideras ĝin "supera manĝebla", dum kampa gvidilo sur Kansaso fungi aprezas ĝin kiel "mezbona en kvalito".[8][25] Ĝi povas havi iomete amaran aŭ peppery gusto kaj havas krudan, grainy teksturo.[26][27][7][25] La firma karno estas plej bone preparita de tranĉanta la agarikon en maldikaj tranĉaĵoj. La blua koloro malaperas kun kuirado kaj la agariko fariĝas grayish. Pro la granular teksturo de la karno, ĝi ne pruntedonas ĝin mem bone al sekiganta. Specimenoj produktanta abundajn kvantojn de lakto povas esti uzita aldoni koloron al marinades.[28]

En Meksiko, individuoj rikoltas la sovaĝajn agarikojn por vendo ĉe la merkatoj de kultivistoj, tipe de junio al novembro; ili estas konsiderita "duan klasan" specion por konsumo.[11][29] L. Indigo estas ankaŭ vendita en Guatemalan merkatoj de majo al oktobro.[30] Ĝi estas unu el 13 Lactarius specio vendita ĉe kamparaj merkatoj en Yunnan en sudokcidenta Ĉinio.[31]

Kemia analizo de meksikaj specimenoj montris L. Indigo enhavi malsekecon ĉe 951 mg/g el agariko, graso ĉe 4.3 mg/g, proteino ĉe 13.4 mg/g kaj dieta fibro ĉe 18.7 mg/g, multe da pli alta en komparo al la ofta butona agariko, kiu enhavas 6.6 mg/g. Komparita al tri alia sovaĝa manĝebla agarika specio ankaŭ elprovita en la studo (Amanita rubescens, Boletus frostii kaj Ramaria flava), L. Indigo enhavis la plej altan saturis fatty acida enhavo, inkluzivanta stearic acido kun 32.1 mg/g—iomete super duono de la totala libera fatty acida enhavo.[32]

La blua koloro de L. Indigo estas pro (7-isopropenyl-4-methylazulen-1-yl)methyl stearate, organika derivaĵo de azulene. Ĝi estas unika al ĉi tiu specio, sed simila al konstruaĵaro trovita en L. Deliciosus.[33]

L. Indigo estas distribuita dum suda kaj orienta Nord-Ameriko, sed estas plej ofta laŭ la Golfa Marbordo, Meksiko kaj Gvatemalo. Ĝia ofteco de apero en la Appalachian Montoj de Usono estis priskribita kiel "foja al loke ofta".[7] Mycologist David Arora notas ke en Usono, la specio estas trovita kun ponderosa pine en Arizono, sed estas neĉeesta en ponderosa de Kalifornio pine arbaroj.[34] Ĝi ankaŭ estis kolektita de Ĉinio, Barato, Gvatemalo kaj Costa Rica (en arbaroj superregita de kverko).[31][35][36][37][38] En Eŭropo, ĝi havas tiel ege nur estita trovita en suda Francio.[39] Studo sur la laŭsezona apero de fruiting korpoj en la subtropical arbaroj de Xalapa, Meksiko, konfirmita ke maksimuma produktado koincidita kun la rainy sezono inter junio kaj septembro.[40]

L. Indigo estas mycorrhizal fungo kaj kiel tia, establas mutualistic interrilato kun la radikoj de certaj arbaj ("gastigantoj"), en kiu la fungi interŝanĝaj mineraloj kaj aminaj acidoj eltirita de la grundo por fiksa karbono de la gastiganto. La subterranean hyphae de la fungo kreskas ingon de histo ĉirkaŭ la rootlets de larĝa gamo de arba specio, formanta laŭdiran ectomycorrhizae—intima asocio kiu estas precipe utila al la gastiganto, kiel la fungo produktas enzimojn ke mineralize organikaj konstruaĵaroj kaj faciligi la translokigon de nutraĵoj al la arbo.[41]

Reflektanta iliajn proksimajn interrilatojn kun arboj, la fruktaj korpoj de L. Indigo estas tipe trovita kreskanta sur la tero, disigita aŭ en grupoj, en ambaŭ deciduous kaj coniferous arbaroj.[42] Ili estas ankaŭ ofte trovita en floodplain areoj kiu estis ĵus mergita.[16] En Meksiko, asocioj estis notita kun meksika alder, amerika Hornbeam, amerika Hophornbeam kaj Liquidambar macrophylla, dum en Gvatemalo la agarikaj asociitoj kun glata-bojo meksika pine kaj alia pine kaj kverka specio.[11][37] En Costa Rica, la specio formas asociojn kun pluraj indiĝenaj kverkoj de la Quercus genus.[43] Nesufiĉe kontrolita laboratoriajn kondiĉojn, L. Indigo estis montrita esti kapabla formi ectomycorrhizal asocioj kun la neotropical pine specio meksika blanka pine, pine de Hartweg, meksika flava pine, glata-boja meksikano pine kaj la Eurasian pines Aleppo pine, eŭropa nigra pine, mara pine kaj Scotoj pine.[30][44]

Lactarius indigo, ofte konata kiel la indiga lakta kaskedo, la indiga (aŭ blua) laktario aŭ la blulakta agariko, estas specio de agarika fungo en la familio Russulaceae. Ĝenerale distribuita specio, ĝi kreskas nature en orienta Nord-Ameriko, Orienta Azio kaj Centr-Ameriko; ĝi estis raportita ankaŭ en la suda Francio. L. indigo kreskas sur la tero en kaj falfoliaj kaj koniferaj arbaroj, kie ĝi formas mikorizajn asociojn kun larĝa gamo de arboj. La fruktaj korpaj koloraj gamoj de malluma bluo en freŝaj specimenoj paliĝas al blua-griza en plej malnovaj specimenoj. La lakto aŭ latex, kiu eliĝadas kiam la agarika histo estas tranĉita aŭ rompita — ĉefaĵo ofta al ĉiuj membroj de la Lactarius-genro — estas ankaŭ indige blua, sed malrapide turniĝas al verda je ekspono al aero. La kaskedo havas diametron de 5 al 15 cm kaj la tigo estas 2 al 8 cm alta kaj 1 al 2.5 cm dika. Ĝi estas manĝebla agariko kaj estas vendita en kamparaj merkatoj en Ĉinio, Gvatemalo kaj Meksiko.

Lactarius indigo es una especie de hongo comestible de la familia Russulaceae. Su cuerpo fructífero presenta colores que van desde el azul oscuro en especímenes frescos al gris azulado pálido en los más viejos. La "leche", o látex, que emana cuando el tejido de la seta es cortado o roto —una característica común a todos los miembros del género Lactarius— también es de color azul añil, pero lentamente se torna en verde al entrar en contacto con el aire. El sombrero suele medir entre 5 y 15 centímetros de diámetro, y el pie alcanza entre 2 y 8 centímetros de longitud y entre 1 y 2,5 cm de grosor.

Es una especie de amplia distribución, y puede encontrarse en el este de Norteamérica,[3] el este de Asia[4] y en Centroamérica.[4] L. indigo crece tanto en bosques caducifolios como de coníferas, donde forma micorrizas con robles y pinos.[4]

Fue descrita por primera vez en 1822 como Agaricus indigo por el micólogo estadounidense Lewis David de Schweinitz,[5]y ubicada en el género Lactarius en 1838, por el sueco Elias Magnus Fries.[6]Hesler y Smith, en su estudio de 1960 de las especies norteamericanas de Lactarius, la definen como especie tipo de la subsección Caerulei, un grupo caracterizado por su látex y el sombrero azules.[7] El nombre de la especie indigo significa, en latín, "azul".[8] En inglés se le conoce con varios nombres comunes como indigo milk cap —literalmente "sombrero lechoso índigo"—,[9] indigo Lactarius —"Lactarius índigo"—,[8] o blue Lactarius —"Lactarius azul"—.[10]En el centro de México, es conocido como añil, azul, hongo azul, zuin, zuine. En Veracruz y en Puebla también se le conoce como quexque (que significa "azul").[11]

Las esporas son translúcidas (hialinas), de forma elíptica o casi esféricas. Sus dimensiones oscilan entre 7 y 9 µm de largo por entre 5,5 y 7,5 de ancho.[8] Por medio del microscopio electrónico de barrido pueden observarse reticulaciones en la superficie de las esporas.[11] Los basidios sostienen cuatro esporas de entre 37 y 45 µm de largo y de 8 a 10 de ancho.[12] Los pleurocistidios tienen entre 40 y 56 µm de largo y entre 6,4 y 8 de anchura, y tienen forma de huso, con el ápice muy estrecho. Los cheilocistidios son abundantes, y sus dimensiones oscilan entre 40 y 45,6 µm de largo y entre 5,6 y 7,2 de ancho.[11]

El característico color azul del cuerpo fructífero y del látex hace que esta especie sea fácilmente reconocible. Existen otros Lactarius que presentan colores azulados:

Esta seta forma micorrizas con pinos y robles, creciendo sobre todo durante el otoño. Se encuentra en casi todo el mundo exceptuando Europa

El color azul de L. indigo se debe principalmente al pigmento químico llamado azuleno. El compuesto, 1-estearoiloximetilen-4-metil-7-isopropenazuleno, extraído y purificado del cuerpo fructífero, es único de esta especie.[14]

Lactarius indigo es una especie de hongo comestible de la familia Russulaceae. Su cuerpo fructífero presenta colores que van desde el azul oscuro en especímenes frescos al gris azulado pálido en los más viejos. La "leche", o látex, que emana cuando el tejido de la seta es cortado o roto —una característica común a todos los miembros del género Lactarius— también es de color azul añil, pero lentamente se torna en verde al entrar en contacto con el aire. El sombrero suele medir entre 5 y 15 centímetros de diámetro, y el pie alcanza entre 2 y 8 centímetros de longitud y entre 1 y 2,5 cm de grosor.

Es una especie de amplia distribución, y puede encontrarse en el este de Norteamérica, el este de Asia y en Centroamérica. L. indigo crece tanto en bosques caducifolios como de coníferas, donde forma micorrizas con robles y pinos.

Lactarius indigo on pilvikuliste sugukonda riisika perekonda kuuluv seen.

Esimesena kirjeldas seda seent teaduslikult 1822 nime all Agaricus indigo saksa päritolu USA loodusteadlane Lewis David de Schweinitz, keda nimetatakse ka Põhja-Ameerika mükoloogia isaks. Niisuguse liiginime valis ta seenele sellepärast, et selle piimmahl on indigosinine. Esimesena paigutas seene riisikate hulka Rootsi loodusteadlane Elias Magnus Fries 1838.

Seen kasvab Põhja-Ameerika idaosas, Kesk-Ameerikas ja Ida-Aasias. Väidetavalt on liiki kohatud ka Indias, Euroopas üksnes Lõuna-Prantsusmaal. Kõige tavalisem on ta Guatemalas, Mehhikos ja USA Mehhiko lahe äärsetes osariikides, Apalatšides on ta harv ja üksnes kohati sage.

Seenekübar on 5–15 cm lai. Kübar on noorelt kumer, vanana muutub nõgusaks. Pole haruldane, et kübaral moodustuvad kontsentrilised ringid. Peale selle võib kübara servas esineda tumesiniseid täppe või isegi tumesiniste täppide rivi. Noore seene kübara alumine osa on sissepoole kaardus, aga vanal seenel nii-öelda rullub lahti. Vars on 2–8 cm pikk ja 1–2½ cm paks. Vars on kogu ulatuses ühesuguse läbimõõduga, ehkki on ka täheldatud, et see on alt kitsam. Vars kinnitub tavaliselt kübara keskkohta, aga siiski ei ole see kõigil seentel nii. Vars on rabe ja kui seent piisavalt painutada, siis tuleb see puhtalt ära. Vars on noorena tihke, aga vanal seenel muutub õõnsaks. Nii kübar kui vars on noorel seenel pisut kleepuvad või limased, aga vanal seenel on piimmahla vähem ning vars ja kübar muutuvad kuivaks. Seen ei lõhna.

Värske piimmahl on indigosinine, aga õhu käes muutub pikkamööda roheliseks. Kõik seene viljakeha koed on pimmahlaga läbi imbunud ja sellepärast on see kõikjalt sinakas. Viljakeha värv sõltub vanusest: noored seened on tumesinised, vanad seened kahvatusinised või hallid.

Eosepulber on kollakas. Eosed on 7–9 μm pikad ja 5½–7½ μm laiad. Eoskand on neljaeoseline, 37–45 μm pikk ja 8–10 μm lai.

Lactarius indigo moodustab mükoriisa mitut liiki puudega. Seeneniidistiku kaudu annab seen puule mineraalaineid ja aminohappeid ning saab vastu pinnasest seotud süsinikku. Seene maa-alused hüüfid kasvavad puu juurekeste ümber, moodustades koest koosneva tupe, mida kutsutakse ektomükoriisaks. Seen toodab ensüüme, mis mineraliseerivad orgaanilisi ühendeid ja hõlbustavad toitainete edastumist puule.

Nõnda on Lactarius indigo tihedalt seotud puudega ja sellepärast leidub tema viljakehi eelkõige puude lähedal, nii hajali kui rühmiti. Tavaliselt eelistavad seened kindlat liiki puid, aga Lactarius indigol eelistusi pole. Ta võib elada koos nii leht- kui okaspuudega. Peale selle on ta sagedane lammidel, mida sageli üle ujutatakse. Laboratoorsetel katsetel on ilmnenud Lactarius indigo võime moodustada mükoriisat paljude männiliikidega, isegi nendega, mis peaksid talle võõrad olema, sest ei kasva Põhja-Ameerikas.

Mehhiko seente keemiline analüüs on näidanud, et Lactarius indigo koosneb 95,1% ulatuses veest. Valke sisaldab ta 13,4‰ ja rasva 4,3‰. Kiudaineid sisaldab ta 18,7‰, märksa rohkem kui šampinjonides, kus on neid 6,6‰. Uuringus võrreldi teda veel kolme söödava seenega, milleks olid Amanita rubescens, Boletus frostii ja Ramaria flava ning Lactarius indigo sisaldas neist kõige rohkem küllastunud rasvhappeid. Pisut üle poole seenes sisalduvatest rasvhapetest moodustab steariinhape, mida seenes leidub 32,1‰.

Sinist värvi põhjustab asuleeni-nimeline orgaaniline ühend. Seda ei kohta üheski muus seenes. Analoogilist ainet sisaldab porgandriisikas, mille piimmahl on porgandikarva.

Lactarius indigo on hästituntud söögiseen. Maitseomadustes arvamused siiski lahknevad, teda on nimetatud nii ülimalt maitsvaks kui keskpäraseks. Guatemalas müüakse seda seent maist oktoobrini ja Mehhikos juunist novembrini, aga Mehhikos ei peeta Lactarius indigot heaks söögiseeneks.

Tal võib olla kergelt kibe või piprane maitse ning tal on jämedateraline seeneliha. Seeneliha soovitatakse enne toiduks valmistamist lõigata õhukesteks liistakateks. Keetmise käigus sinine värvus kaob ja seen muutub hallikaks. Teralisuse tõttu ei muutu seenelihatükid kuivatamise käigus pikemaks. Seeni saab kasutada marinaadi värvimiseks.

Lactarius indigo est une espèce de champignons de la famille des Russulaceae. Cette espèce pousse dans l'est de l'Amérique du Nord, l'Asie de l'Est et l'Amérique centrale. En Europe, elle a jusqu'à présent été trouvée uniquement dans le sud de la France.

Lactarius indigo croît dans les forêts de feuillus et de conifères, où il forme des associations mycorhiziennes avec une large gamme d'arbres.

La couleur du sporophore varie du bleu foncé au bleu-gris pâle en fonction de son âge. Le latex qui suinte quand le tissu du champignon est coupé ou brisé — une caractéristique commune à tous les membres du genre Lactarius — est aussi bleu indigo, mais il se transforme lentement en vert lors de l'exposition à l'air.

C'est un champignon comestible.

Selon NCBI (1 janv. 2011)[1] :

Lactarius indigo est une espèce de champignons de la famille des Russulaceae. Cette espèce pousse dans l'est de l'Amérique du Nord, l'Asie de l'Est et l'Amérique centrale. En Europe, elle a jusqu'à présent été trouvée uniquement dans le sud de la France.

Lactarius indigo croît dans les forêts de feuillus et de conifères, où il forme des associations mycorhiziennes avec une large gamme d'arbres.

La couleur du sporophore varie du bleu foncé au bleu-gris pâle en fonction de son âge. Le latex qui suinte quand le tissu du champignon est coupé ou brisé — une caractéristique commune à tous les membres du genre Lactarius — est aussi bleu indigo, mais il se transforme lentement en vert lors de l'exposition à l'air.

C'est un champignon comestible.

Lactarius indigo adalah jamur yang dapat dimakan dari kelas Russulaceae.[3] Nama indigo pada jamur ini dikarenakan warna biru tua pada bagian tubuhnya.[4] Jamur ini memiliki batang berukuran 2,5-7,5 cm dan lebar tudung 5-12,5 cm.[3] Tudung berbentuk cembung dengan bagian tengah yang tampak melengkung ke bawah.[3] Spora yang dihasilkan L. indigo berukuran 7-9 x 5,5-7,5 µm, berbentuk elips hingga hampir bundar, dan kadang-kadang membentuk kerutan, dan dihiasi oleh amiloid.[3] Jamur ini ditemukan hidup sendiri atau berkelompok di bagian dasar kayu konifer atau kayu tumbuhan berdaun lebar.[4] Bagian batang berukuran pendek, cepat berongga, memiliki warna yang sama dengan tudung dan sering ditemukan adanya bintik-bintik kebiruan.[3]

Lactarius indigo adalah jamur yang dapat dimakan dari kelas Russulaceae. Nama indigo pada jamur ini dikarenakan warna biru tua pada bagian tubuhnya. Jamur ini memiliki batang berukuran 2,5-7,5 cm dan lebar tudung 5-12,5 cm. Tudung berbentuk cembung dengan bagian tengah yang tampak melengkung ke bawah. Spora yang dihasilkan L. indigo berukuran 7-9 x 5,5-7,5 µm, berbentuk elips hingga hampir bundar, dan kadang-kadang membentuk kerutan, dan dihiasi oleh amiloid. Jamur ini ditemukan hidup sendiri atau berkelompok di bagian dasar kayu konifer atau kayu tumbuhan berdaun lebar. Bagian batang berukuran pendek, cepat berongga, memiliki warna yang sama dengan tudung dan sering ditemukan adanya bintik-bintik kebiruan.

Lactarius indigo (Schwein.) Fr., è un fungo appartenente alla famiglia delle Russulaceae. È diffuso in centro America, Nord America e in Estremo Oriente. Cresce sia nelle foreste di decidue che nelle foreste di conifere dove forma associazioni micorriziali con diverse specie di alberi.

Il lattice che rilascia quando il fungo viene spezzato è di colore indaco-blu ma lentamente diventa verde dopo esposizione all'aria.

Il Lactarius indigo è un fungo commestibile.

Nel novembre 2019, il Lactarius Indigo è cresciuto in un bosco di quercia nella Sicilia orientale. L'eccezionale ritrovamento, primo in Europa, è stato effettuato dal micologo Nicola Amalfi.[1]

Lactarius indigo (Schwein.) Fr., è un fungo appartenente alla famiglia delle Russulaceae. È diffuso in centro America, Nord America e in Estremo Oriente. Cresce sia nelle foreste di decidue che nelle foreste di conifere dove forma associazioni micorriziali con diverse specie di alberi.

Il lattice che rilascia quando il fungo viene spezzato è di colore indaco-blu ma lentamente diventa verde dopo esposizione all'aria.

Il Lactarius indigo è un fungo commestibile.

Nel novembre 2019, il Lactarius Indigo è cresciuto in un bosco di quercia nella Sicilia orientale. L'eccezionale ritrovamento, primo in Europa, è stato effettuato dal micologo Nicola Amalfi.

Lactarius indigo é um fungo da família de cogumelos Russulaceae. Pode ser facilmente distinguido dos outros integrantes do gênero devido a sua característica cor azul. A espécie forma corpos de frutificação cujo tronco mede até 6 cm de altura. O píleo, o "chapéu" do cogumelo, é inicialmente convexo e com as margens enroladas para baixo, mas quando o fungo amadurece ele adquire um formato semelhante a um funil. Pode atingir 15 cm de diâmetro e sua superfície, pegajosa ao toque, tem faixas concêntricas com diferentes tons de azul. A face inferior do chapéu apresenta as lamelas. Inicialmente azuis, com o passar do tempo ficam mais pálidas e manchadas de verde pelo látex que escorre quando são danificadas.

A espécie foi descrita pela primeira vez em 1822 por Lewis von Schweinitz. A princípio batizada de Agaricus indigo, teve seu nome modificado para o atual em 1838 pelo sueco Elias Magnus Fries, considerado o "pai da micologia". O epíteto específico "indigo" é derivado da palavra latina que significa "azul índigo", uma referência à cor predominante do cogumelo. Vários nomes populares do fungo também remetem a esta característica, a exemplo de blue milk mushroom em inglês, e hongo azul em espanhol. A cor lhe é conferida pela presença do pigmento azuleno.

L. indigo é um cogumelo comestível, mas devido à textura granular da carne e sabor um pouco amargo e picante, sua qualidade gastronômica é considerada por alguns especialistas como "medíocre". Ainda assim, é um dos fungos mais tradicionais utilizados na culinária mexicana. Fica melhor preparado quando o cogumelo é cortado em fatias finas, e espécimes com grandes quantidades de látex podem ser usados para dar cor a marinadas. A cor azul desaparece com o cozimento e o fungo se torna acinzentado.

Na natureza, pode ser encontrado em todo o sul e leste da América do Norte, mas é mais comum ao longo da Costa do Golfo dos Estados Unidos, México e Guatemala. Também já foi coletado na China, Índia e França. Tal como um típico fungo micorrízico, forma uma relação simbiótica com várias espécies de árvores, especialmente betuláceas e pinheiros. Os cogumelos crescem sobre o solo de florestas, espalhados ou em grupos. Também são comumente vistos em áreas de planícies inundadas.

A primeira descrição científica da espécie conhecida atualmente como Lactarius indigo foi feita pelo micologista norte-americano Lewis David von Schweinitz, numa publicação de 1822. Na época, o cogumelo recebeu o nome de Agaricus indigo.[3] O fungo foi posteriormente transferido para o gênero Lactarius, em 1838, pelo cientista sueco Elias Magnus Fries, formando assim a nomenclatura binominal aceita na atualidade.[4] O botânico alemão Otto Kuntze ainda viria a chamar a espécie de Lactifluus indigo no tratado Revisio Generum Plantarum de 1891, mas a mudança de nome sugerida não foi adotada por outros especialistas, sendo hoje considerado um sinônimo.[2]

Os norte-americanos Hesler e Smith, em seu estudo de 1960 sobre as espécies de Lactarius da América do Norte, definiram L. indigo como a espécie-tipo da subseção Caerulei, um grupo caracterizado por ter tronco, látex e chapéu azuis.[5] Em 1979, eles revisaram suas opiniões acerca da organização das subdivisões do gênero Lactarius, e decidiram classificar L. indigo no subgênero Lactarius, utilizando como critério a cor do látex e sua mudança de tonalidade observada após a exposição ao ar ambiente.[6] Eles explicaram que "o desenvolvimento gradual da pigmentação azul para violeta, como um processo de espécie a espécie, é um fenômeno interessante que merece um estudo mais aprofundado. O clímax é atingido em L. indigo, que é todo azul. L. chelidonium e sua variedade chelidonioides, L. paradoxus, e L. hemicyaneus podem ser considerados como estágios intermediários ao longo do processo que culminou com o L. indigo".[7][nota 1]

O epíteto específico "indigo" é derivado da palavra latina que significa "azul índigo".[8] Seus nomes populares em língua inglesa incluem indigo milk cap,[9] indigo Lactarius,[8] blue milk mushroom,[10] e blue Lactarius.[11] Na região central do México, é conhecido como añil, azul, hongo azul, zuin, e zuine; também é chamado de quexque (que significa "azul") nos estados de Veracruz e Puebla.[12]

Como muitos outros cogumelos, Lactarius indigo se desenvolve a partir de um nódulo ou cabeça de alfinete que se forma dentro de um micélio, uma massa de células fúngicas filamentosas chamadas de hifas e que constituem a maior parte do organismo. Sob condições ambientais adequadas de temperatura, umidade e disponibilidade de nutrientes, as estruturas reprodutivas visíveis, os corpos frutíferos, são formados. O píleo ou "chapéu" do corpo frutífero, mede entre 5 e 15 cm de diâmetro, é inicialmente convexo e depois desenvolve uma depressão central; com o passar do tempo a região central se afunda ainda mais, assumindo quase que a forma de funil, com as bordas do chapéu voltadas para cima.[13] A margem do píleo é enrolada para dentro quando jovem, mas se desenrola e se eleva à medida que o fungo amadurece. A superfície do píleo é azul índigo quando fresco, mas depois se desbota e fica cinzento-prateado pálido ou azul, ocasionalmente com manchas esverdeadas. Muitas vezes possui zonas, com linhas concêntricas alternando tonalidades mais pálidas e mais escuras, e o chapéu pode ter manchas em azul escuro, especialmente na margem. Píleos jovens são pegajosos ao toque.[14]

A carne tem cor azul pálido, ficando lentamente esverdeada depois de exposta ao ar ambiente; seu sabor é suave a levemente acre. A carne do cogumelo inteiro é frágil, e o tronco se quebra se encurvado o suficiente.[15] O látex exsudado a partir do tecido lesado é azul índigo, e o tecido danificado fica manchado com um tom esverdeado; tal como a carne, o látex tem uma sabor suave.[8] Lactarius indigo é conhecido por não produzir látex em abundância, diferente do que acontece com muitas outras espécies de Lactarius,[16] e espécimes mais velhos podem ser demasiados secos por produzir uma quantidade mínima de substância leitosa.[17]

As lamelas do cogumelo variam de adnatas (diretamente ligadas ao tronco) a ligeiramente decorrentes (prolongando-se para baixo do comprimento da estipe), e estão dispostas bastante próximas umas das outras. Sua cor é azul índigo, ficando mais pálidas com o passar do tempo ou se manchando de verde quando danificadas. O tronco mede de 2 a 6 cm de altura por 1 a 2,5 cm de espessura, com o mesmo diâmetro em todo o seu comprimento ou às vezes mais estreito na base. Sua cor é azul índigo ao azul-prateado ou cinzento. O interior do tronco é sólido e firme inicialmente, mas desenvolve uma cavidade com a idade.[9] Assim como o píleo, o tronco do cogumelo jovem é pegajoso ou viscoso ao toque, mas logo torna-se seco.[18] Geralmente o tronco se liga ao chapéu na região central deste, embora essa junção possa também estar levemente deslocada lateralmente.[19] Os corpos de frutificação L. indigo não têm um odor distinguível.[20]

Lactarius indigo var. diminutivus é uma variedade menor do cogumelo, com um diâmetro de chapéu entre 3 a 7 cm, e uma estipe mais baixa e mais fina, medindo 1,5 a 4 cm de comprimento e 0,3 a 1 cm de espessura.[21] É frequentemente encontrado no estado norte-americano da Virgínia.[20] Hesler e Smith foram os primeiros a descrever esta variedade, com base em espécimes coletados no condado de Brazoria, Texas. Eles descreveram seu habitat típico como "ao lado de um fosso lamacento sob gramíneas e ervas daninhas, [com] pinheiros nas proximidades".[22]

Quando vistos em massa, como numa impressão de esporos (técnica usada na identificação de fungos), os esporos aparecem de cor creme a amarela.[8][9] Ao microscópio óptico, os esporos são translúcidos (hialinos), elípticos ou quase esféricos, com verrugas amiloides, e têm dimensões de 7 a 9 por 5,5 a 7,5 micrometros (µm).[8] A microscopia eletrônica de varredura revela reticulações na superfície dos esporos.[12] O himênio é a camada de tecido do corpo de frutificação que produz os esporos, e é composto por hifas que se estendem para as lamelas e acabam como células terminais. Vários tipos de células podem ser observadas no himênio, e elas possuem características microscópicas que podem ser usadas para ajudar a identificar o cogumelo ou diferenciar espécies nos casos em que os caracteres macroscópicos sejam ambíguos. Os basídios, as células portadoras de esporos, possuem quatro esporos cada e medem 37 a 45 µm de comprimento por 80 a 10 µm de largura no ponto mais largo.[23] Os cistídios são as células terminais das hifas do himênio que não produzem esporos, e sua função é ajudar na dispersão dos esporos, além de manter a umidade favorável em torno dos esporos em desenvolvimento.[24] Os pleurocistídios são os cistídios encontrados na face de uma lamela, medem 40 a 56 por 6,4 a 8 µm, e têm aproximadamente a forma de fuso e um ápice constrito. Os queilocistídios, localizados na borda das lamelas, são abundantes e medem 40 a 45,6 por 5,6 a 7,2 µm.[12]

A cor azul característica do corpo de frutificação e do látex faz com que esta espécie seja facilmente reconhecível. Mas outros cogumelos do gênero Lactarius também possuem, pelo menos em parte ou em algum momento do seu estágio de desenvolvimento, uma tonalidade azulada. A exemplo do L. paradoxus, um fungo encontrado no leste da América do Norte,[20] que possui um chapéu azul-acinzentado quando jovem, mas cujo látex e lamelas têm cor castanho-avermelhado ao roxo-marrom. L. chelidonium tem um chapéu amarelado a cinza-azulado e látex amarelado a marrom. A carne do píleo de L. quieticolor tem cor azul, mas no nível da base do tronco ela é laranja a vermelho-alaranjada.[9] Apesar dos especialistas acreditarem que a coloração azul de L. indigo seja extremamente rara no gênero Lactarius, em 2007, cinco novas espécies com carne ou látex azulados foram relatadas a partir de espécimes encontrados na parte peninsular da Malásia, incluindo L. cyanescens, L. lazulinus, L. mirabilis, e mais duas espécies ainda não nomeadas.[25]

Embora o Lactarius indigo seja bastante conhecido como uma espécie de cogumelo comestível, as opiniões dos especialistas variam quanto a conveniência de seu consumo. Por exemplo, o micologista norte-americano David Arora o considera de excelente comestibilidade,[9] enquanto que um guia de campo sobre fungos do Kansas classifica a espécie como de qualidade gastronômica medíocre.[26] Tem textura grosseiramente granulada,[8][26] e o seu sabor é descrito como sendo um pouco amargo ou mesmo picante,[27][28] mas às vezes é referido simplesmente como "suave".[29] A carne, de consistência firme, fica melhor preparada cortando o cogumelo em fatias finas. A cor azul desaparece com o cozimento e o fungo torna-se acinzentado. Por causa da textura granular da sua carne, o cogumelo não se presta bem à secagem. Espécimes com grandes quantidades de látex podem ser usados para dar cor a marinadas.[30]

No México, cogumelos silvestres de L. indigo são colhidos para serem vendidos em feiras de produtos agrícolas, geralmente entre os meses de junho a novembro;[12] naquele país, é considerada uma espécie de "segunda classe" para consumo,[31] embora seja um dos fungos mais tradicionais utilizados na culinária mexicana.[32] O cogumelo também é vendido em mercados da Guatemala, de maio a outubro,[33] e é uma das treze espécies de Lactarius vendidas em mercados rurais na província de Yunnan, no sudoeste da China.[34]

A análise química de espécimes coletados no México mostrou que L. indigo tem em sua composição 95,1% de água, 4,3 mg de lipídios por grama de cogumelo (mg/g) e 13,4 mg/g de proteínas. Há 18,7 mg/g de fibra dietética, quantidade muito maior em relação ao champignon, que contém 6,6 mg/g. Em comparação com outras três espécies de cogumelos comestíveis silvestres analisadas num mesmo estudo (Amanita rubescens, Boletus frostii e Ramaria flava), L. indigo apresentou o mais alto teor de ácidos graxos saturados, incluindo 32,1 mg/g de ácido esteárico; pouco mais da metade do teor total de ácidos graxos livres.[35]

A cor azul do L. indigo é dada pelo (7-isopropenil-4-metilazuleno-1-il)metil estearato, um composto orgânico conhecido como azuleno. É exclusivo desta espécie, mas semelhante a uma substância encontrada no L. deliciosus.[36]

Lactarius indigo está distribuído em todo o sul e leste da América do Norte, mas é mais comum ao longo da Costa do Golfo dos Estados Unidos, México e Guatemala. Sua frequência de aparecimento nos Apalaches é descrita como "ocasional a localmente comum".[8] O micologista David Arora ressalta que a espécie é encontrada associada ao pinheiro Pinus ponderosa no estado do Arizona, mas está ausente nas florestas desse tipo de árvore na Califórnia.[37] O cogumelo também já foi coletado na China,[34] Índia,[38][39] Guatemala e Costa Rica (em florestas dominadas por carvalhos).[40][41] Na Europa, até agora só foram encontrados no sul da França.[42] Um estudo sobre o aparecimento sazonal de corpos de frutificação na floresta subtropical de Xalapa, no México, confirmou que a produção máxima coincide com a estação chuvosa, entre os meses de junho e setembro.[43]

Ecologicamente, é um fungo micorrízico, assim como todas as espécies do gênero Lactarius. O cogumelo estabelece portanto uma associação simbiótica mutuamente benéfica com várias espécies de plantas. As hifas subterrâneas do fungo crescem com uma bainha de tecido ao redor das radículas de alguns tipos de árvores, formando as chamadas ectomicorrizas, uma associação íntima que garante ao cogumelo compostos orgânicos importantes para a sua sobrevivência oriundos da fotossíntese do vegetal. Em troca, o vegetal é beneficiado por um aumento da absorção de água e outras substâncias, pois o fungo produz enzimas que mineralizam compostos orgânicos e facilitam a transferência de nutrientes para a árvore.[44]

Como reflexo de sua estreita relação com as árvores, os corpos frutíferos do L. indigo são normalmente encontrados crescendo sobre o solo, espalhados ou em grupos, tanto em florestas de decíduas como de coníferas.[45] Eles também são comumente vistos em áreas de planícies que foram recentemente inundadas.[17] No México, constatou-se que o cogumelo se associa com árvores da família das Betuláceas tais como Alnus jorullensis, Carpinus caroliniana, Ostrya virginiana e Liquidambar macrophylla,[12] enquanto que na Guatemala está relacionado com Pinus pseudostrobus e outras espécies de pinheiros e carvalhos.[40] Na Costa Rica, a espécie se associa com vários carvalhos nativos do gênero Quercus.[46] Sob condições controladas de laboratório, L. indigo mostrou-se capaz de formar associações ectomicorrízicas com as espécies de pinheiros neotropicais Pinus ayacahuite, P. hartwegii, P. oocarpa, P. pseudostrobus,[33] e também com alguns pinheiros da Eurásia a exemplo do pinheiro-de-alepo, pinheiro-larício, pinheiro-bravo e pinheiro-da-escócia.[47]

|ano= (ajuda) |coautor= (ajuda)

Lactarius indigo é um fungo da família de cogumelos Russulaceae. Pode ser facilmente distinguido dos outros integrantes do gênero devido a sua característica cor azul. A espécie forma corpos de frutificação cujo tronco mede até 6 cm de altura. O píleo, o "chapéu" do cogumelo, é inicialmente convexo e com as margens enroladas para baixo, mas quando o fungo amadurece ele adquire um formato semelhante a um funil. Pode atingir 15 cm de diâmetro e sua superfície, pegajosa ao toque, tem faixas concêntricas com diferentes tons de azul. A face inferior do chapéu apresenta as lamelas. Inicialmente azuis, com o passar do tempo ficam mais pálidas e manchadas de verde pelo látex que escorre quando são danificadas.

A espécie foi descrita pela primeira vez em 1822 por Lewis von Schweinitz. A princípio batizada de Agaricus indigo, teve seu nome modificado para o atual em 1838 pelo sueco Elias Magnus Fries, considerado o "pai da micologia". O epíteto específico "indigo" é derivado da palavra latina que significa "azul índigo", uma referência à cor predominante do cogumelo. Vários nomes populares do fungo também remetem a esta característica, a exemplo de blue milk mushroom em inglês, e hongo azul em espanhol. A cor lhe é conferida pela presença do pigmento azuleno.

L. indigo é um cogumelo comestível, mas devido à textura granular da carne e sabor um pouco amargo e picante, sua qualidade gastronômica é considerada por alguns especialistas como "medíocre". Ainda assim, é um dos fungos mais tradicionais utilizados na culinária mexicana. Fica melhor preparado quando o cogumelo é cortado em fatias finas, e espécimes com grandes quantidades de látex podem ser usados para dar cor a marinadas. A cor azul desaparece com o cozimento e o fungo se torna acinzentado.

Na natureza, pode ser encontrado em todo o sul e leste da América do Norte, mas é mais comum ao longo da Costa do Golfo dos Estados Unidos, México e Guatemala. Também já foi coletado na China, Índia e França. Tal como um típico fungo micorrízico, forma uma relação simbiótica com várias espécies de árvores, especialmente betuláceas e pinheiros. Os cogumelos crescem sobre o solo de florestas, espalhados ou em grupos. Também são comumente vistos em áreas de planícies inundadas.

Lactarius canadensis Winder[1]

Lactifluus indigo (Schwein.) Kuntze[2]

pritrditev himenija: priraščen ali poraščajoč

bet: gol

Lactarius indigo je široko razširjena gliva iz družine golobičarke, ki raste na območju Severne[3] in Srednje Amerike[3][4][5] ter Vzhodne Azije.[6] Raste tako v listnatih kot tudi v iglastih gozdovih, kjer tvori mikorizni odnos z mnogimi vrstami dreves.[7] Meso je obarvano temno modro pri mlajših primerkih do svetlo modro-sivo pri starejših primerkih. Značilnost vseh vrst v rodu mlečnic je mleko oz. lateks, ki mezi iz tkiva glive po mehanski poškodbi (npr. pri zarezi). Pri L. indigo je mleko indigo modre barve, ki pa postane zelene barve po izpostavitvi zraku.[3][8] Je užitna goba in ena pomembnejših poljščin, ki jo prodajajo na kmečkih trgih v Mehiki,[9] Gvatemali[10] in na Kitajskem.[6]

L. indigo je ameriški mikolog de Schweinitz leta 1822 poimenoval kot Agaricus indigo,[11] nato pa jo je švedski mikolog Fries premestil v rod mlečnic.[12] Nemški botanik Kuntze je glivo poimenoval kot Lactifluus indigo leta 1891 v svoji razpravi Revisio Generum Plantarum,[2] vendar predlagano ime ni bilo splošno sprejeto. Leta 1960 sta Hesler in Smith med raziskovanjem mlečnic v Severni Ameriki uvrstila glivo kot tipsko vrsto podrazvrstitve Caerulei v rodu mlečnic, ki jo označujeta modro mleko ter lepljivi in modri klobuk.[13] Leta 1979 sta reorganizirala podrazvrstitve v rodu mlečnic ter uvrstila glivo v podrod Lactarius glede na barvo mleka in njegovo spremembo barve po izpostavitvi zraku.[14]

Specifično ime indigo izhaja iz latinske besede indicus color, kar dobesedno pomeni indijska barva, tj. modro barvilo za tekstilne izdelke, oz. poenostavljeno indigo modra barva.[3] V osrednjem delu Mehike je znana kot añil, azul, hongo azul, zuin in zuine, v Veracruzu in Puebli pa tudi kot quexque.[9]

Kot pri vse drugih glivah se tudi L. indigo razvije iz nodula, ki se razvije v podzemnem miceliju, omrežju hif, ki tvorijo podgobje glive. Pri ustreznih pogojih, tj. pri ustrezni temperaturi in vlažnosti ter zadostni količini hranilnih snovi, se razvije plodno telo podgobja, imenovanega bazidiokarp (plodišče oz. trosnjak pri prostotrosnicah). Klobuk, ki ima premer od 5–15 cm, je v začetku izbočen (konveksen), pozneje pa se na sredini vboči (tj. pojavi se depresija).[15] Robovi klobuka so pri mladih primerkih zavihani navznoter, ščasoma pa se odvihajo in obrnejo navzgor. Osrednje vbočenje postane pri starih primerkih tako globoko, da postane oblika klobuka lijakasta, potem ko se robovi odvihajo in obrnejo navzgor. Površina klobuka je v svežem stanju indigo modre barve, zatem pa zbledi do sivo- oz. srebrno-modre barve, včasih so prisotne tudi zelene pege. Pogosto so prisotne koncentrične črte, ki razdelijo površino klobuka na izmenjujoče se svetlejše in temnejše kolobarje, poleg tega pa so nemalokrat prisotne še temnejše pege proti robu. Mladi primerki so lepljivi na otip.[16]

Meso je belkaste do modrikaste barve in po izpostavitvi zraku počasi postane zelenkasto ter ima blago kisel okus. Celotno meso je trdno, vendar se ga z lahkoto pretrga, prav tako se brez težav loči klobuk od beta.[8] Mleko oz. lateks, ki se izceja iz poškodovanega tkiva, je prav tako indigo modre barve, po kratkem času pa obarva tkivo zelenkasto; tako kot meso ima tudi mleko blago kisel okus.[3] Za L. indigo je značilno, da ne proizvaja toliko mleka kot druge vrste iz rodu mlečnic,[17] poleg tega pa je pri starejših primerkih lahko mleko skorajda popolnoma odsotno.[18]

Trosovnica (himenij) je lahko bodisi neposredno priraščena na bet bodisi se prirašča na njega. Je indigo modre barve, s staranjem pa zbledi oz. se obarva zeleno pri poškodbi. Bet je visok od 2–6 cm in širok od 1-2,5 cm, pri dnišču je lahko zožen. Tudi bet je indigo modre do sivo- oz. srebrno modre barve. Notranjost beta je trdna in polna, s staranjem pa postane votla.[19] Kot klobuk je tudi bet na začetku lepljiv oz. spolzek na otip, vendar se ščasoma osuši.[20] Spoj klobuka in beta je centriran, čeprav je lahko postavljen rahlo izven središča.[21] Razmnoževalne strukture so brez vonja.[22]

Lactarius indigo var. diminutivus je manjša sorta obravnavane glive, s premerom klobuka od 3–7 cm ter z 1,5-4 dolgim in 0,3–1 cm širokim betom.[23] Pogosta je v Virginiji.[22] Prvič je sicer bila odkrita v Brazoria County, Teksas, poleg blatnih jarkov pod travo in plevelom, z borom vrste Pinus taeda v bližini.[24]

Pri gledanju s prostim očesom (npr. pri odtisku spor) so spore kremaste do rumene barve.[3][19] Pod svetlobnim mikroskopom so spore prozorne in eliptične, skorajda okrogle oblike, imajo amiloidne izrastke in so velikosti 7-9 µm x 5,5-7,5 µm.[3] Z vrstičnim elektronskim mikroskopom so vidne mrežaste (retikularne) strukture.[9]

Trosovnica je plodni del plodišča in je zgrajena iz hif, ki segajo v lističe. V njej so vidni različni tipi celic, s pomočjo katerih lahko ugotovimo oz. razlikujemo določene vrste med sabo, v primeru da so makroskopske lastnosti nejasne. Bazidiji so velikosti 37-45 µm x 8-10 µm, na vršičkih pa se nahajajo 4 spore.[25] Cistide so končne (terminalne) celice hif v trosovnici, v kateri ne nastajajo spore, pač pa služijo temu, da olajšajo raznašanje spor in da zagotavljajo primerno vlažnost okoli nastajajočih spor.[26] Plevrocistide so cistide koničaste oblike in velikosti 40-56 µm x 6,4-8 µm, ki se nahajajo na površini lističev. Heilocistide so prisotne v velikem številu na robu lističev in merijo 40-56 µm x 6,4-8 µm.[9]

Zaradi značilne modre barve plodišča in mleka lahko L. indigo zlahka ločimo od ostalih podobnih vrst iz rodu L. indigo. Srebrno-modra L. paradoxus, ki raste na vzhodnem delu Severne Amerike,[22] ima sivo-modri klobuk v zgodnjem obdobju, vendar ima rdečkasto-rjavo do vijolično-rjavo mleko in trosišče. L. chelidonium ima rumenkast oz. temno rumeno-rjavi do modro-sivi klobuk ter rumenkasto do rjavo mleko. L. quieticolor ima modro obarvano meso pri klobuku in oranžno do rdeče-oranžno meso pri dnišču beta.[19] Čeprav je izrazito modro obarvanje pri L. indigo redko v okviru rodu mlečnic, so bile v zadnjem času odkrite nove vrste na polotoški Maleziji z modrim mlekom ali mesom (npr. L. cyanescens, L. lazulinus in L. mirabilis).[27]

Življenjski prostor L. indigo se razteza po južnem in vzhodnem delu Severne Amerike, vendar je najbolj pogosta blizu Mehiškega zaliva in v Mehiki. Dokaj pogosta je tudi v Apalačih.[3] V Arizoni raste blizu borov vrste Pinus Ponderosa, medtem ko v Kaliforniji tovrsten odnos ni bil opažen.[28] Raste tudi na Kitajskem,[6] v Indiji,[29][30] Gvatemali,[4] in Kostariki, pretežno v hrastovih gozdovih.[5] Glede na sezonski pojav plodišč v subtropskih gozdovih v Mehiki je največja proizvodnja spor v deževnem obdobju med junijem in septembrom.[31]