fi

nimet breadcrumb-navigoinnissa

Diatome of kieselwiere (klas Bacillariophyceae) is eensellige wiere wat gewoonlik 'n geelbruin tot groengeel kleur het. Die wier se kieselagtige selwand bestaan uit twee helftes wat op mekaar pas soos 'n deksel op 'n pildosie. As die selinhoud van die diatoom doodgaan, sink die diatoomskelet na die meer- of seebodem. Deur die eeue heen het daar op hierdie manier 'n baie dik laag diatoomgrond op die seebodem gevorm. Tans word meer as 10 000 soorte diatome onderskei, wat nie net in die see en in varswater voorkom nie, maar ook in vogtige plekke op land.

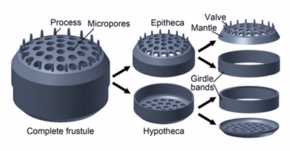

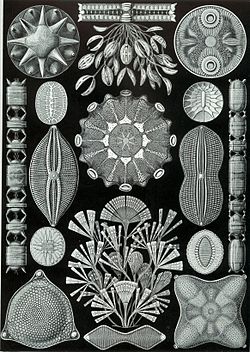

Die sowat 10 000 diatome kan van alle ander eensellige wiere onderskei word op grond van hul tweedelige selwand. Die boonste doppie van die selwand pas soos 'n deksel op die ietwat kleiner onderste doppie. Die twee helftes van die selwand word deur 'n bandvormige ring, die gordel, bymekaar gehou. Die harde, kieselagtige wand van die diatoom bevat geen kalkbestanddele soos dikwels met die harde dele van ander organismes die geval is nie, maar wel silikonverbindings, soos kieselsure en silikaat.

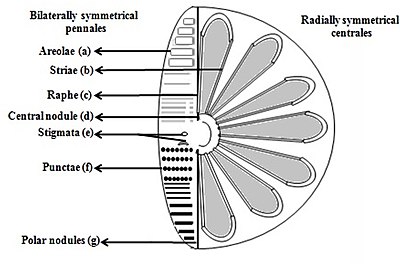

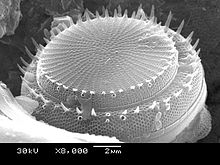

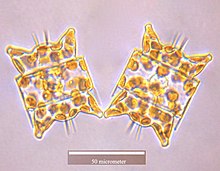

Daar word twee ordes diatome onderskei, naamlik die ronde Centrales en die ellips- of bootvormige Pennales. Die Centrales het dikwels 'n growwe oppervlak met fyn groefies. Daarbenewens het die meeste soorte Centrales lang hare of stekelhare, wat die dryfvermoë van die sel verbeter. Die Pennales het 'n gladde selwand met 'n veervormige patroon van porieë. In die sitoplasma van die sel is korrel- of plaatvormige kleurstofdraers (chromatofore) waarin daar chlorofiel en ook geel en bruin pigmente (karoteen, karotenoïed en xantofil) voorkom. Die chromatofore gee aan die diatoom 'n kenmerkende bruingeel tot groengeel kleur.

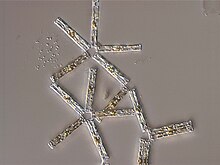

Diatome word oral op aarde aangetref. Die meeste soorte lewe in die see of in varswater, maar ook in 'n verskeidenheid van vogtige woonplekke op land, soos byvoorbeeld in boomstamme of onder klippe. Die meeste Centrales lewe in die see, waar hulle 'n belangrike bestanddeel van die plantaardige plankton vorm en 'n groot rol in suurstofproduksie speel. Daarenteen is die Pennales hoofsaaklik varswaterbewoners. Hulle kom gewoonlik voor in kettingvormige of vertakte kolonies wat aan die een of ander bodem vasgeheg is. Die selle word aan mekaar vasgeheg met behulp van 'n klewerige stof wat deur die sitoplasma afgeskei word.

Die diatome plant gewoonlik voort deur middel van seldeling. Met die seldeling erf albei dogterselle een van die doppies van die moedersel se tweedelige wand en bou dan self die ander helfte om daarby aan te pas. Die doppies wat van die moedersel verkry word, vorm altyd die deksel van die nuwe dogtersel. Die onderste deel word altyd self deur die dogtersel gevorm. Dit lei daartoe dat die dogtersel wat die grootste doppie (die moederseldeksel) erf, altyd so groot soos die moedersel word, terwyl die ander dogtersel baie kleiner is. Hierdie proses van seldeling duur 'n paar generasies voort, en met elke seldeling ontstaan 'n klein en 'n groot nakomeling. Later is die kleinste selle só klein dat hulle nie meer lewensvatbaar is nie. In sulke gevalle vorm die diatoom spore (ouksospore).

By die Centrales deel die selkern 'n paar keer; die protoplasma wring hom uit die sel na buite en neem normale afmetinge aan. Hierná word twee volledige nuwe doppies gevorm.

In die geval van die Pennales word geslagselle gevorm. Hierdie geslagselle verlaat die oorspronklike doppies en versmelt met mekaar. Die sigote hou aan met hulle groei totdat hulle volwassenheid bereik het en kort daarna deel hulle en vorm nuwe doppies. In ongunstige omstandighede vorm die selle russpore, wat weer sal ontwikkel as die sel se lewensomstandighede verbeter.

Die diatome speel nie net 'n belangrike rol in suurstofvoorsiening nie, maar ook in voedselverskaffing vir planktondiertjies, soos vislarwes en mikroklein krefies.

Wanneer die selinhoud van 'n diatoom doodgaan, of die ou doppies verlaat, sink die diatoomskelet na die bodem van die see of die meer. As gevolg hiervan het daar deur die eeue heen 'n dik laag diatoomgrond op die seebodem gevorm. Hierdie diatoomgrond, wat dikwels kieselguhr genoem word, is van groot belang vir die nywerheid. Nadat Alfred Nobel dinamiet uitgevind het, het hy diatoomgrond gebruik om die gevaarlike nitrogliserien te absorbeer. Dit het die waarskynlikheid van onbeheerde ontploffings baie verminder. Diatoomgrond is vroeër baie gebruik as 'n poleermiddel in tandepasta.

Diatome of kieselwiere (klas Bacillariophyceae) is eensellige wiere wat gewoonlik 'n geelbruin tot groengeel kleur het. Die wier se kieselagtige selwand bestaan uit twee helftes wat op mekaar pas soos 'n deksel op 'n pildosie. As die selinhoud van die diatoom doodgaan, sink die diatoomskelet na die meer- of seebodem. Deur die eeue heen het daar op hierdie manier 'n baie dik laag diatoomgrond op die seebodem gevorm. Tans word meer as 10 000 soorte diatome onderskei, wat nie net in die see en in varswater voorkom nie, maar ook in vogtige plekke op land.

Les diatomees (taxón Diatomea, Diatomeae o Bacillariophyceae sensu llato), ye un grupu d'algues unicelulares que constitúi un de los tipos más comunes de fitoplancton. Contién anguaño unes 20.000 especies vives que son importantes productores dientro de la cadena alimenticia.[3] Munches diatomees son unicelulares, anque dalgunes d'elles pueden esistir como colonies en forma de filamentos o cintes (y.g. Fragillaria), abanicos (y.g. Meridion), zigzags (y.g. Tabellaria) o colonies estrellaes (y.g. Asterionella). Una carauterística especial d'esti tipu d'algues ye que se topen arrodiaes por una paré celular única fecha de xil opalino (dióxidu de siliciu hidratao) llamada frústula. Estes frústules amuesen una amplia variedá na so forma, pero xeneralmente consisten en dos partes asimétriques con una división ente elles, carauterística que-y da nome al grupu. La evidencia fósil suxer que les diatomees aniciáronse mientres o dempués del periodu Xurásicu inferior, anque los primeros restos corpóreos son del Paleógeno. Les comunidaes de diatomees son una ferramienta usada recurrentemente pa la vixilancia de les condiciones medioambientales, de la calidá de l'agua y nel estudiu de los cambeos climáticos.

Les diatomees son organismos fotosintetizadores que formen parte del plancton (fitoplancton). Anguaño conócense más de 200 xéneros de diatomees, 20.000 especies vives y envalórase qu'hai alrodíu de 100.000 especies extintes.[4][5] Como colonizadores, les diatomees destremanse por atopase en cualesquier tipu d'ambiente yá seya marín, dulceacuícola, terrestre o tamién sobre superficies húmedes. Otres atópense n'ambientes onde esisten condiciones estremes de temperatura o salín y d'igual forma atopamosles interautuando con otros organismos como ye'l casu coles cianofícees filamentoses onde esiste un epifitismo per parte de les diatomees. La mayoría son peláxiques (viven n'agües llibres), dalgunes son bentóniques (sobre'l fondu marín), ya inclusive otres viven so condiciones de mugor atmosférico. Son especialmente importantes nos océanos, onde se calcula qu'apurren hasta un 45 % del total de la producción primaria oceánica.[6] La distribución espacial del fitoplancton marín ye acutada tantu horizontal como verticalmente. Les diatomees viven en tolos océanos dende los polos hasta los trópicos; les rexones polar y subpolar contienen relativamente poques especies en contraste cola biota templada.[7] Anque les rexones tropicales esiben la mayor cantidá d'especies, les mayores poblaciones de diatomees alcuentrense ente les rexones polar y templao.

Les diatomees pertenecen a un gran grupu llamáu Heterokontophyta, que inclúi especies tantu autótrofes (y.g algues pardes) como heterótrofes (y.g. oomicetos). Los cloroplastos mariellu-marrones de les diatomees son típicos de los heteroncontos, con cuatro membranes, clorofiles a, c1 y c2 y pigmentos tales como β-caroteno, fucoxantina, diatoxantina y diadinoxantina. Les reserves d'alimentu almacénense como carbohidratos o aceites, qu'amás de sirvir de reserva, contribúin a la so flotabilidá.

Los sos individuos usualmente escarecen de flaxelu, pero tán presentes en gametos y usualmente presenten una estructura heteroconta, sacante en qu'escarecen de vellosidaes (mastigonemas) carauterísticos d'otros grupos. Munches diatomees nun tienen movimientu, anque delles otres tienen movimientu flaxeláu. Por cuenta de la so relativamente pesada paré celular afondien con facilidá, les formes planctónices n'agües abiertes polo xeneral dependen de la turbulencia oceánica producida pol vientu nes capes cimeres pa caltenese suspendíes nes agües superficiales allumaes pol Sol. Delles especies regulen viviegamente la so flotabilidá colos lípidos intracelulares pa faer frente al fundimientu.

A pesar de ser xeneralmente microscópiques, delles especies de diatomees pueden algamar los 2 milímetros de llargor. Les diatomees tán conteníes dientro d'una única paré celular de silicatu (frústula) compuesta de dos valves separaes. El xil biogénica de la que la paré celular componse ye sintetizada intracelularmente por polimerización de monómeros d'ácidu silícico. Esti material ye depués secretado escontra l'esterior de la célula onde participa na conformanza de la paré celular. Les cáscares de les diatomees se superponen una a otra como los dos metaes d'una placa de Petri (esto ye, como una caxa y la so tapadoria). El frústulo apaez delicadamente afatáu con relieves que formen dibuxos variaos y perfeutamente simétricos. Dando llugar a dos tipos de diatomees, les que tienen simetría radial y les de simetría llateral. Los frústulos de les diatomees posense por gravedá cuando ye dixerida o muerre la célula, dando orixe a roques sedimentaries como les diatomites y moronites.

Les diatomees alternen ente la reproducción asexual por división celular, que ye la más frecuente, y la reproducción sexual.[8] Na reproducción por división celular, cada célula fía recibe una de les frústules de la célula padre y utilizala como frústula mayor (o epiteca), reconstruyendo una frústula menor (o hipoteca). De resultes d'esti procesu, la célula que recibió la frústula menor resulta nuna diatomea de menor tamañu que la orixinal. Per otra parte, la frústula nun pudi crecer. D'esta forma, na primer xeneración el 50% de les diatomees son de menor tamañu que la orixinal y vanse faciendo cada vez más pequeñes en cada xeneración. Reparóse sicasí, que delles especies pueden estremase ensin causar un amenorgamientu nel tamañu de célula.[9] El procesu sigue hasta que les célules algamen una tercer parte del so tamañu máximu.[10] Dempués d'un determináu númberu de xeneraciones, les diatomees reproducir de forma sexual, produciendo gametos ensin frústules que se funden formando una auxospora. Esti mecanismu ayuda a restablecer el tamañu orixinal de les diatomees porque'l cigotu crez muncho primero de producir una nueva frústula.

Les célules vexetatives de les diatomees son diploides (2N) y la meiosis xenera gametos machos y fema qu'entós se funden pa formar el cigotu. El cigotu lliberase de la so cubierta y crez na forma d'una célula esférica cubierta por una membrana orgánica (auxospora). Cuando la auxospora algama la so midida máxima (la de diatomea inicial), forma nel so interior a una diatomea que da empiezu a una nueva xeneración. Tamién pueden formase espores como respuesta a condiciones medioambientales desfavorables, produciéndose la guañada cuándo les condiciones ameyoren.[11]

Les diatomees son mayoritariamente non móviles, anque la espelma de delles especies puede ser flaxeláu, con movimientu de normal llindáu al deslizamiento.[12] Nes diatomees céntriques, los gametos machos son pequeños y tienen un flaxelu, ente que los gametos fema son grandes ya inmóviles (oogamia). Otra manera, nes diatomees pennades dambos gametos escarecen de flaxelos (isogamia).[10] Haise documentáu qu'una especie del grupu de les diatomees pennades ensin rafe ye anisógama y, por tanto, considerase una etapa transicional ente les diatomees céntriques y les diatomees pennades con rafe.[13]

Les diatomees, Diatomeae (Dumortier, 1821) o Bacillariophyceae (Haeckel, 1878), son clasificaes según la distribución de los sos poros y ornamentación. Si les frústules tienen una simetría radial o trímera nomense diatomees centraes, ente que si tienen una simetría billateral y forma allargada nomenanse pennadas. El primer tipu ye parafiléticu con respectu al segundu. Delles diatomees pennades tamién presenten una fisura a lo llargo de la exa llonxitudinal, denominada rafe, que ta implicada nos movimientos realizaos pola diatomea. Al grupu Bolidophyceae, apocayá descubiertu, considérase-y una clase estreme. La clasificación más recién considera cuatro grupos de diatomees:[14]

Diatomea

Coscinodiscophyceae (P): Centrales radiales.

Mediophyceae (P) : Centrales polares.

Fragilariophyceae (P): Pennales sin rafe.

Bacillariophyceae: Pennales con rafe.

La tierra diatomea ye un material constituyíu poles frústules de diatomees fosilizaes, aplicáu como fertilizante ya inseuticida en tierres pa cultivu, al ser un productu natural, ye inocuo y nun presenta riesgos pa la salú o contaminación. La tierra diatomea aprove micronutrientes al suelu que son de gran importancia pa la crecedera de les plantes, pudiendo amontar la fertilidá del suelu, actuando sinérgicamente con calciu y magnesiu, amás amenorga la lixiviación de fósforu, nitróxenu y potasiu y favorez la so absorción nes plantes. La tierra diatomea tamién actúa como reconstituyente en tierres contaminaes por metales pesaos o hidrocarburos, amás neutraliza la tosicidá del aluminiu en suelos acedos y amenorga l'absorción de fierro y manganesu.[15]

Les propiedaes d'esos materiales, formaos por partícules microscópiques, entrevesgaes y bien regulares en tamañu, facenlos curiosos pa diversos usos, como la fabricación de la dinamita, onde la nitroglicerina ye enfiñida, amenorgando la probabilidá d'una esplosión accidental.

El polvu de diatomees emplégase como inseuticida n'animales y plantes. Actúa deshidratando a inseutos hasta matalos, amás curtia y fura el exoesqueleto, mancándolos y esaniciándolos de forma progresiva y efeutiva. Les frústules de les diatomees son d'orixe natural, polo cual son inocues p'animales y plantes. A diferencia d'inseuticides tóxicos, el polvu de diatomees nun puede ingresar nos texíos animales por cuenta del so tamañu.[16]

Les diatomees pertenecen a les microalges oleaxinoses por cuenta de que presenten fracciones lipídices del 25 % (condiciones normales) al 45 % (condiciones de estrés), cultivables en fotobioreautores (FBR). La producción de biodiésel a partir de diatomees dase por mediu de transesterificación del aceite preveniente de les microalgas. La producción de biodiésel basase na producción y captación de biomasa de diatomees, que ye deshidratada y sometida a ultrasoníos por que llibere los sos componentes, darréu los lípidos son dixebraos de carbohidratos y proteínes. L'aceite llográu ye sometíu a transesterificación alcalina, aceda o enzimática pa producir glicerol y biodiésel.

Los aceites provenientes de diatomees son principalmente triglicéridos, que xeneren amiestos de ésteres d'arriendo al convertise en biocombustible. El cracking térmicu o pirólisis, ye un procesu alternu a la transesterificación que tresforma triglicéridos n'otros compuestos orgánicos simples.[17]

Determinóse que les diatomees tienen la capacidá de producir ácidos grasos poliinsaturados (AGPI) n'altes concentraciones, como por casu la producción de diatomees del xéneru Nitzschia d'ácidu eicosapentanoico (GUO). Nitzschia tien ventayes como la resistencia a temperatures d'hasta -6 °C y ambientes altamente salobres, amás el so aceite algama'l 50 % del pesu secu de la biomasa.[18]

Les comunidaes de diatomees pueden utilizase pa la determinación de les condiciones ambientales tantu de presente como del pasáu y del cambéu climáticu. Tamién pueden utilizase pa determinar la calidá de l'agua.

La demostración de la presencia de Diatomees dientro de los cuévanos cardiacos o nel migollu óseu de cadabres ye utilizada en melicina forense como fuerte niciu de muerte por sumersión (afogamientu).[19]

Les diatomees (taxón Diatomea, Diatomeae o Bacillariophyceae sensu llato), ye un grupu d'algues unicelulares que constitúi un de los tipos más comunes de fitoplancton. Contién anguaño unes 20.000 especies vives que son importantes productores dientro de la cadena alimenticia. Munches diatomees son unicelulares, anque dalgunes d'elles pueden esistir como colonies en forma de filamentos o cintes (y.g. Fragillaria), abanicos (y.g. Meridion), zigzags (y.g. Tabellaria) o colonies estrellaes (y.g. Asterionella). Una carauterística especial d'esti tipu d'algues ye que se topen arrodiaes por una paré celular única fecha de xil opalino (dióxidu de siliciu hidratao) llamada frústula. Estes frústules amuesen una amplia variedá na so forma, pero xeneralmente consisten en dos partes asimétriques con una división ente elles, carauterística que-y da nome al grupu. La evidencia fósil suxer que les diatomees aniciáronse mientres o dempués del periodu Xurásicu inferior, anque los primeros restos corpóreos son del Paleógeno. Les comunidaes de diatomees son una ferramienta usada recurrentemente pa la vixilancia de les condiciones medioambientales, de la calidá de l'agua y nel estudiu de los cambeos climáticos.

Diatom yosunlar (lat. Bacillariophyta). Bu tipə tək, nadir hallarda qonur rəngli (piqmenti - fukoksantin) mikroskopik (0,75 mkm – 2 mm) kolonial orqanizmlər daxildir. Diatom yosunlar planktonda geniş, daha az miqdarda dəniz və şorsu hövzələrinin bentosunda, bəziləri torpaqda məskunlaşırlar; müasir diatom yosunlar qütb dairəsinə yaxın və əsasən arktik hövzələrdə yayılmışdır. Hüceyrə ikitaylı silisium qabıq içərisində yerləşir, qabıq iki elementdən ibarətdir; bunlardan kiçiyi qapaq kimi həmişə digər tayı örtür. Sonuncunun içərisində dairəvi lövhə (tayın özülü) və kəmərcik (yan tərəflər) ayrılır.

Lövhənin formasına görə diatom yosunlar tipi iki sinifə ayrılır: pennatlar və sentriklər. Pennat diatom yosunlar ikitərəfli simmetriyalı olub, formaları uzunsov oval (yumurtavari), iynəşəkilli olur, adətən, qabığın ortasında yarıqşəkilli dəlik (tikiş xətti) yerləşir. Sentrik diatom yosunlar radial simmetriya ilə səciyyələnir, formaca dairəvi, üçbucaq, ulduz şəkillidir. Bütün diatomeaların kəmərcik tərəfdən görünüşü çubuqşəkillidir (uzunsov-düzbucaqlı) ki, bu da tipin ikinci adını – Bacillariophyta (lat. bacillus - çubuq) təyin etmişdir. Qabığın taylarında çoxsaylı hamar və ya qabarıq nazik haşiyəli iri və xırda dəliklər vardır.

Diatom yosunlar 300-ə qədər cinsi və 1200-dən çox müasir və fossil növləri məlumdur. Cinsi və qeyri-cinsi yolla artırlar. Süxur əmələgətirən orqanizmlərdir; bitkilər məhv olduqdan sonra dibə çökərək (çox vaxt bir-birindən ayrılmış tayalar şəklində) silisium lillərini, qazıntı halında isə silisium süxurlarını (diatomitlər, trepellər, opokalar və b.) əmələ gətirirlər. Diatom yosunlar - sentriklər təbaşirdə (yura tapıntıları haqqında məlumatlar mübahisəlidir), pennatlar isə paleogendə meydana gəlmişdir; orta paleogenin şirinsu hövzələrində yaşamağa uyğunlaşmışdır, buna qədər isə təmamilə dənizlərdə məskunlaşmışlar. Cavan çöküntülərin (neogendən başlayaraq) zonal bölgülərinin əsaslandırılmasında diatom yosunlar böyük əhəmiyyəti vardır. Fatsiya göstəricisi (göl, çay və b.) kimi diatom yosunlar olduqca əhəmiyyətlidir. Təbaşir - müasir.

Xəzərdə 292 növü qeyd edilmişdir, onlardan planktonda 165 növ, bentosda isə 129 növü yaşayır. Chaetoceros, Thalassiosira,Coscinodiscus və Rhizosolenia cinsləri Xəzərin planktonunda və fitoplanktonunda mühüm rol oynayır.

Geologiya terminlərinin izahlı lüğəti. — Bakı: Nafta-Press, 2006. — Səhifələrin sayı: 679.

Diatom yosunlar (lat. Bacillariophyta). Bu tipə tək, nadir hallarda qonur rəngli (piqmenti - fukoksantin) mikroskopik (0,75 mkm – 2 mm) kolonial orqanizmlər daxildir. Diatom yosunlar planktonda geniş, daha az miqdarda dəniz və şorsu hövzələrinin bentosunda, bəziləri torpaqda məskunlaşırlar; müasir diatom yosunlar qütb dairəsinə yaxın və əsasən arktik hövzələrdə yayılmışdır. Hüceyrə ikitaylı silisium qabıq içərisində yerləşir, qabıq iki elementdən ibarətdir; bunlardan kiçiyi qapaq kimi həmişə digər tayı örtür. Sonuncunun içərisində dairəvi lövhə (tayın özülü) və kəmərcik (yan tərəflər) ayrılır.

Lövhənin formasına görə diatom yosunlar tipi iki sinifə ayrılır: pennatlar və sentriklər. Pennat diatom yosunlar ikitərəfli simmetriyalı olub, formaları uzunsov oval (yumurtavari), iynəşəkilli olur, adətən, qabığın ortasında yarıqşəkilli dəlik (tikiş xətti) yerləşir. Sentrik diatom yosunlar radial simmetriya ilə səciyyələnir, formaca dairəvi, üçbucaq, ulduz şəkillidir. Bütün diatomeaların kəmərcik tərəfdən görünüşü çubuqşəkillidir (uzunsov-düzbucaqlı) ki, bu da tipin ikinci adını – Bacillariophyta (lat. bacillus - çubuq) təyin etmişdir. Qabığın taylarında çoxsaylı hamar və ya qabarıq nazik haşiyəli iri və xırda dəliklər vardır.

Diatom yosunlar 300-ə qədər cinsi və 1200-dən çox müasir və fossil növləri məlumdur. Cinsi və qeyri-cinsi yolla artırlar. Süxur əmələgətirən orqanizmlərdir; bitkilər məhv olduqdan sonra dibə çökərək (çox vaxt bir-birindən ayrılmış tayalar şəklində) silisium lillərini, qazıntı halında isə silisium süxurlarını (diatomitlər, trepellər, opokalar və b.) əmələ gətirirlər. Diatom yosunlar - sentriklər təbaşirdə (yura tapıntıları haqqında məlumatlar mübahisəlidir), pennatlar isə paleogendə meydana gəlmişdir; orta paleogenin şirinsu hövzələrində yaşamağa uyğunlaşmışdır, buna qədər isə təmamilə dənizlərdə məskunlaşmışlar. Cavan çöküntülərin (neogendən başlayaraq) zonal bölgülərinin əsaslandırılmasında diatom yosunlar böyük əhəmiyyəti vardır. Fatsiya göstəricisi (göl, çay və b.) kimi diatom yosunlar olduqca əhəmiyyətlidir. Təbaşir - müasir.

Xəzərdə 292 növü qeyd edilmişdir, onlardan planktonda 165 növ, bentosda isə 129 növü yaşayır. Chaetoceros, Thalassiosira,Coscinodiscus və Rhizosolenia cinsləri Xəzərin planktonunda və fitoplanktonunda mühüm rol oynayır.

Les diatomees (Bacillariophyceae) són una classe d'algues unicel·lulars microscòpiques (encara que n'existeixen algunes que formen colònies), que s'enquadra dintre del fílum Heterokontophyta, superfílum Chromista, regne protoctist, domini Eukarya. El nom científic de la classe és Bacillariophyceae (o Diatomeae) i es relaciona filogenèticament amb la classe Chrysophyceae i d'altres del grup Chromista.

Les diatomees són organismes fotosintetitzadors que viuen en aigua dolça o marina i constitueixen una part molt important del fitoplàncton.

Un dels trets característics de les cèl·lules de diatomees és la presència d'una coberta de sílice (diòxid de silici hidratat), anomenat frústul. Els frústuls mostren una gran diversitat de formes, algunes de molt belles i ornamentades, i generalment consten de dues parts asimètriques o valves amb una divisió entre si, d'aquí el nom del grup. Moltes espècies apareixen formant encadenaments o altres agregats ordenats. L'evidència fòssil suggereix que es van originar durant o abans del període Juràssic primerenc.

Actualment, es coneixen més de 200 gèneres vivents de diatomees i s'estima que hi ha al voltant de 100.000 espècies extintes (%[1] %[2]). Com a colonitzadores, les diatomees es distingeixen per trobar-se en qualsevol tipus d'ambient, ja sigui marí o d'aigua dolça. També es troben en ambients on existeixen condicions extremes de temperatura o salinitat i, de la mateixa forma, les trobem interaccionant amb altres organismes com és el cas de cianofícies filamentoses, en què existeix un epifitisme per part de les diatomees.

La majoria són pelàgiques (viuen en aigües lliures), encara que algunes són bentòniques (sobre el fons marí), o fins i tot poden viure sobre superfícies humides. Són especialment importants en els oceans, on es calcula que proporcionen fins a un 45% del total de la producció primària oceànica (%[3]). Encara que són generalment microscòpiques, algunes espècies de diatomees poden arribar fins a 2 mil·límetres de longitud. Els frústuls de les diatomees se sedimenten per gravetat quan és digerida o mor la cèl·lula, i donen origen a roques sedimentàries, com les diatomites i moronites.

Les propietats d'aquests materials, formats per partícules microscòpiques, intricades i molt regulars en grandària, els han fets atractius per a diversos usos, com la fabricació de la dinamita, en què la nitroglicerina és embeguda, reduint la probabilitat d'una explosió accidental.

Els tàxons més rics en lípids es fan servir per desenvolupar el biocombustible d'alga.

Diatomees. Microscopi òptic. 300X. Mètode de la gota penjant

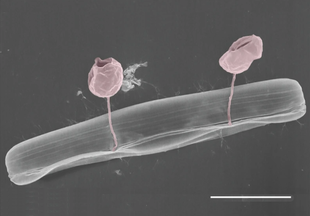

Phaeodactylum tricornutum és una alga diatomea i és l'única espècie del gènere Phaeodactylum. Aquesta alga adopta diferents tipus morfològics, fet que la fa útil per a estudiar alteracions en la forma cel·lular, que poden ser estimulats per canvis en les condicions ambientals. A més a més, pot créixer en absència de silicona, fet que proporciona noves eines en el camp de la fabricació de nanoinstruments de silicona.

Les diatomees (Bacillariophyceae) són una classe d'algues unicel·lulars microscòpiques (encara que n'existeixen algunes que formen colònies), que s'enquadra dintre del fílum Heterokontophyta, superfílum Chromista, regne protoctist, domini Eukarya. El nom científic de la classe és Bacillariophyceae (o Diatomeae) i es relaciona filogenèticament amb la classe Chrysophyceae i d'altres del grup Chromista.

Les diatomees són organismes fotosintetitzadors que viuen en aigua dolça o marina i constitueixen una part molt important del fitoplàncton.

Un dels trets característics de les cèl·lules de diatomees és la presència d'una coberta de sílice (diòxid de silici hidratat), anomenat frústul. Els frústuls mostren una gran diversitat de formes, algunes de molt belles i ornamentades, i generalment consten de dues parts asimètriques o valves amb una divisió entre si, d'aquí el nom del grup. Moltes espècies apareixen formant encadenaments o altres agregats ordenats. L'evidència fòssil suggereix que es van originar durant o abans del període Juràssic primerenc.

Rozsivky (Diatomeae, syn Bacillariophyceae) jsou velkou skupinou jednobuněčných fotosyntetizujících organismů s dvojdílnou křemičitou schránkou, tradičně řazenou mezi hnědé řasy.

Rozsivky jsou jednobuněčné řasy s dvojdílnou křemitou schránkou. Skupinu tvoří 285 rodů obsahujících 10 až 12 tisíc druhů (Round et al. 1990). Jejich fotosyntetickými barvivy jsou chlorofyly a a c, fukoxanthin. Chloroplasty mají čtyři obalné membrány a tylakoidy jsou uspořádány v trojicích. Zásobními látkami jsou chrysolaminaran, olej a volutin.

Schránka rozsivek se nazývá frustula. Je tvořena polymerizovaným oxidem křemičitým, který je proti korozi chráněn vrstvou kyselého polysacharidu diatotepinu. Schránku si buňka vytváří aktivním vychytáváním kyseliny křemičité z prostředí rychlostí až 18 molekul za sekundu. Frustula se skládá ze dvou částí (jako krabice s víkem či Petriho miska) – epithéky a hypothéky, z nichž každá má svou plochu (valvu) a boční stěnu (pleuru či cingulum; viz obrázek). Během nepohlavního rozmnožování získá každá z dceřiných buněk jednu část mateřské frustuly a druhou, vždy tu menší, si dotvoří. V případě nedostatku křemíku v prostředí se nepohlavní rozmnožování zastavuje. Podle tvaru frustuly se rozsivky dělí na dvě hlavní skupiny: centrické, radiálně souměrné a penátní, dvoustranně souměrné.

Při nepohlavním rozmnožování probíhá rovina dělení rovnoběžně s rovinou valv. Dělení frustuly viz výše. Při zmenšení frustuly pod určitou mez dochází ke smrti buňky či k pohlavnímu rozmnožení.

Centrické rozsivky se pohlavně rozmnožují oogamicky. Z jedné buňky vznikne oogonium s oosférou z další pak antheridium, v němž vzniknou čtyři spermatozoidy s jedním bičíkem. Po splynutí spermatozoidu s oosférou vzniká auxospora, velká buňka s polysacharidickou stěnou, na které se časem začne usazovat stěna křemičitá.

Penátní rozsivky se pohlavně rozmnožují izogamicky nebo anizogamicky. Dvě rozsivky se k sobě přiblíží a vytvoří společný slizový obal. Následně v každé z buněk proběhne meióza a jedna ze vzniklých gamet améboidním pohybem pronikne do druhé frustuly, splyne s jednou z gamet v ní za vzniku auxospory (viz výše).

Rozsivky jsou velmi významnými primárními producenty. Podle některých pramenů připadá na mořské rozsivky 20–25 % roční celkové primární produkce Země. Podle některých pramenů se výrazně, spolu se sinicemi, podílely na vzniku kyslíkaté atmosféry na Zemi. Jsou dominantní skupinou mořského planktonu, zvláště v temperátních a chladných mořích. Významně jsou zastoupeny také ve sladkovodním planktonu a bentosu. Mohou žít také přisedle na pevných podkladech ve vodě, jako jsou kameny, dřevo, rostliny či živočichové. Některé rozsivky žijí i v půdě.

Nejstarší rozsivky pocházejí z období spodní křídy. Evolučně starší jsou rozsivky centrické. Záznamy o nejmladších penátních jsou z období před 70 mil. let. V rámci hnědých řas jsou monofyletickou skupinou.

Schránky odumřelých rozsivek tvoří horninu diatomit (křemelinu), který se těží (v ČR například u Borovan u Českých Budějovic) a využívá se jako filtrační či sorpční materiál. V některých oblastech se rozsivky podílely na vzniku ložisek ropy. Vzhledem ke specifickým nárokům některých rozsivek se tyto využívají jako indikační organismy pro určení kvality vody, a to i zpětně v archeologických vykopávkách.

Moderní taxonomové rozsivky oddělují zcela od rostlin a řadí je do samostatné, páté říše živých organismů, Chromista. Zdůvodňuje se to tím, že svými vlastnostmi leží na rozhraní mezi rostlinami a živočichy. V této říši tvoří část jedné ze dvou podříší (Chromobiota), do níž jsou zařazeny jako samostatná třída kmene (oddělení) Ochrophyta.

Třetí možné dělení je řadí do oddělení Heterokontophyta a spolu s ním do čtvrté říše, Protista.

Třída Bacillariophyceae se v současných systémech dělí obvykle na dvě velké podtřídy, a to Eunotiophycidae a Bacillariophycidae.

Rozsivky (Diatomeae, syn Bacillariophyceae) jsou velkou skupinou jednobuněčných fotosyntetizujících organismů s dvojdílnou křemičitou schránkou, tradičně řazenou mezi hnědé řasy.

Underrækken Diatomeae kiselalger – tidligere rækken Bacillariophyta – også kaldet diatoméer, hører til planteplanktonet og er levende organismer. De indeholder klorofyl, et grønt stof, der bruges i omdannelsen af solens lys til energi. Algerne har to skaller dannet af kisel, der sidder sammen som låget sidder på en madkasse. Skallerne har små huller, som algen optager næring og udskiller affaldsstoffer igennem. Nogle af disse organismer har små børster og pigge som de bruger til at holde sig svævende i vandet med.

Disse alger blev før i tiden kun inddelt i to grupper: de centriske, der hovedsagelig lever i de frie vandmasser, og de pennate, som især er bundlevende. Algerne er brune eller brungule, de pennate alger kan af og til farve havbunden helt gulbrun, hvis de forekommer i store mængder, f.eks. på de vanddækkede lavvandede, områder i Vadehavet.

Die Kieselalgen oder Diatomeen (Bacillariophyta) bilden ein Taxon von Photosynthese betreibenden Protisten (Protista) und werden in die Gruppe der Stramenopilen (Stramenopiles) eingeordnet.

Oft wird die Gruppe mit dem synonymen Namen Diatomea Dumortier bezeichnet, alternativ sind auch die synonymen Namen Fragilariophyceae, Diatomophyceae in Verwendung. Einige Autoren nennen die Kieselalgen Bacillariophyceae, sie ordnen sie also als Klasse in die, dann als Phylum aufgefassten photosynthetischen Vertreter der Stramenopiles (Ochrophyta) ein, diese Auffassung wird etwa in den Datenbanken DiatomBase[1] und WoRMS vertreten. Diese Verwendung ist allerdings missverständlich, da andere Taxonomen eine enger abgegrenzte Klasse Bacillariophyceae, als eine von drei Klassen innerhalb der Diatomeen aufführen. Bei Verwendung dieses Namens ist also die jeweilige Auffassung zu kontrollieren, da es sonst zu Missverständnissen kommt.

Man unterscheidet heute rund 6000 Arten. Es wird jedoch angenommen, dass insgesamt bis zu 100.000 Arten existieren.[2] Eine Arbeitsstelle für Diatomeen-Forschung (mit umfangreicher Sammlung und Online-Katalog), begründet von Friedrich Hustedt, befindet sich im Alfred-Wegener-Institut.[3]

Ihren deutschen Trivialnamen verdanken die Kieselalgen der Zellenhülle (Frustel), die überwiegend aus Siliziumdioxid (Summenformel: SiO2) besteht, dem Anhydrid der Kieselsäure (vereinfachte Summenformel: SiO2 · n H2O). Die Kieselsäure wird jedoch im deutschen Sprachraum oft fälschlich mit ihrem Anhydrid gleichgesetzt. Das Siliziumdioxid gewinnt der Organismus aus der Monokieselsäure Si(OH)4.

Die Frustel ist schachtelförmig und besteht aus zwei schalenförmigen Teilen unterschiedlicher Größe, von denen die eine („Epitheka“) mit ihrer Öffnung über die Öffnung der anderen („Hypotheka“) greift. Die Schalen sind in charakteristischen Mustern strukturiert. Aufgrund der Schalengeometrie werden zwei Typen von Kieselalgen unterschieden: Zentrische Kieselalgen (Centrales) haben zumeist runde, bisweilen auch dreieckige Schalen, während pennate Kieselalgen (Pennales) stab- oder schiffchenförmige, mitunter auch bogen- oder S-förmig gekrümmte Gehäuse ausbilden. Die Schalen werden mittels spezieller Peptide angelegt, die als Silaffine bezeichnet werden. Die Silaffine ermöglichen die Ausfällung des Siliziumdioxids in kleine globuläre Siliziumdioxidaggregate, den sogenannten „Nanospheren“. Diese haben einen Durchmesser von 30 bis 50 nm und bilden in ihrer Gesamtheit die eigentlichen Schalen aus.[4][5] Viele pennate Kieselalgen können auf einer festen Unterlage mit Hilfe einer Raphe kriechen. Die Geschwindigkeit beträgt bis zu 20 μm/s.

Kieselalgen sind einzellig und fast stets unbegeißelt. Nur bei einigen Arten besitzen die männlichen Gameten eine Geißel, eine nach vorn gerichtete Flimmergeißel. Die durch sekundäre Endosymbiose mit einer Rotalge entstandenen Plastiden[6] sind braun gefärbt, da das Xanthophyll Fucoxanthin die Farbe der Chlorophylle (Chlorophyll a und c) überdeckt. Als Reservestoff dient Chrysolaminarin.

In der Regel sind Kieselalgen mikroskopisch klein. Zum Beispiel erreicht die Achnanthes eine Länge von 40 Mikrometer. Einige Arten können jedoch bis zu 2 Millimeter lang werden.

Die Diatomeen sind diploid und vermehren sich hauptsächlich ungeschlechtlich durch Zellteilung. Die Tochterzellen erhalten jeweils einen Schalenteil und bilden den anderen Teil neu; hiervon leitet sich auch die Bezeichnung „Diatomee“ (altgriechisch διατέμνειν (diatemnein) = spalten) ab. Der neue Schalenteil ist stets die kleinere Hypotheka, so dass im Generationenverlauf die Zellgröße fast aller Nachkommen fortlaufend schwindet, nur die Tochterzelllinie der Ausgangs-Epitheka behält die ursprüngliche maximale Größe bei. Wird eine Minimalgröße unterschritten, stirbt das Individuum. Bevor eine Minimalgröße erreicht wird, können jedoch Sexualvorgänge stattfinden. Aus den Zellen bilden sich durch Meiose haploide Gameten. Bei zentrischen Kieselalgen wurde Oogamie nachgewiesen: Die Gameten werden frei, nach Verschmelzen eines weiblichen mit einem männlichen Gameten bildet sich aus der Zygote unter Größenwachstum eine Dauerform, eine sogenannte Auxospore. Bei pennaten Kieselalgen wurde Konjugation beobachtet: Zwei Partner legen sich aneinander und bilden eine gemeinsame Cytoplasmabrücke („Konjugationskanal“), in die jeweils ein haploider Kern und ein Chloroplast der beiden Partner einwandern. Aus der so gebildeten Zygote bildet sich eine Auxospore, in der die Kernverschmelzung (Karyogamie) stattfindet. Aus den Auxosporen der zentrischen und pennaten Kieselalgen wird jeweils eine größere neue Kieselalge mit einer neuen zweiteiligen Schale gebildet.

Kieselalgen kommen hauptsächlich im Meer und in Süßgewässern planktisch oder benthisch vor, oder sie sind auf Steinen oder Wasserpflanzen (Epiphyten) angesiedelt. Manche Arten brauchen reines und kaum verschmutztes Wasser und sind aus diesem Grunde auch Zeigerorganismen für unbelastete Gewässer. Andere Arten wiederum, die im engl. auch als agricultural guild bezeichnet werden, sind typisch für Gewässer, die durch landwirtschaftliche Einträge, bspw. durch Überdüngung, besonders belastet sind. Zu diesen werden u. a. Navicula radiosa, Melosira varians, Nitzschia palea, Diatoma vulgare oder Amphora perpusilla gezählt.[7] Auch terrestrische Arten finden sich unter den Diatomeen; diese besiedeln Böden, in tropischen Gebieten auch Blätter von Bäumen.

Die Kieselalgen wurden traditionell in die radiärsymmetrischen Centrales und die bilateralsymmetrischen Pennales gegliedert. Die Centrales sind jedoch paraphyletisch, eine stabile Systematik auf molekulargenetischer Grundlage hat sich noch nicht etabliert. Nach der taxonomischen Datenbank Diatombase[1] existiert derzeit keine allgemein akzeptierte Gliederung der Kieselalgen in Subtaxa.

Eine weit verbreitete, aber nicht von allen Taxonomen anerkannte Gliederung könnte so aussehen[8], die höhere Gliederung wurde in vergleichbarer Form in die weithin verwendete Klassifikation der Eukaryoten durch Sina Adl und Kollegen übernommen.[9]

Die Kieselalgen sind Hauptbestandteil des Meeresphytoplanktons und sind die Haupt-Primärproduzenten organischer Stoffe, bilden also einen wesentlichen Teil der Basis der Nahrungspyramide. Als Sauerstoff produzierende (oxygene) Phototrophe erzeugen sie auch einen großen Teil des Sauerstoffs in der Erdatmosphäre.

Aus der relativen Arten-Zusammensetzung der Kieselalgenpopulation eines Gewässers kann recht exakt dessen Trophiegrad abgeleitet werden (Diatomeenindex), sowie weitere Gewässerparameter wie pH-Wert, Salinität, Saprobie etc. Diese Verfahren können auch auf Sedimente oder auf Öllagerstätten angewandt werden und geben dann Aufschluss über die ehemals herrschenden Lebensbedingungen.

Zur Identifizierung der Arten wird eine Aufwuchsprobe mit Kieselalgen mit Schwefelsäure, Wasserstoffperoxid, Kaliumdichromat oder einem anderen Oxidationsmittel behandelt und so werden alle organischen Bestandteile der Probe aufgelöst. Es bleiben nur noch die reinen Siliziumdioxid-Schalen übrig. Diese werden in einem Einschlussmedium mit hohem optischem Brechungsindex (z. B. Naphrax™) eingebettet und lichtmikroskopisch mit dem Phasenkontrast-Verfahren bei ca. 1000-facher Vergrößerung identifiziert.

Sterben die Zellen, sinken sie auf den Grund des Gewässers ab, die organischen Bestandteile werden abgebaut und die Siliziumdioxid-Schalen bilden eine Ablagerung, die sogenannte Kieselgur (Diatomeenerde). Dieser Prozess ist, insbesondere im Marinen, erst unterhalb der CCD (Calcit-Kompensationstiefe) effizient genug, um große Vorkommen zu bilden. Die entstehende Kieselgur wird in Technik und Medizin angewendet. Diatomeenschalen finden unter anderem Verwendung als Filter, zur Herstellung von Dynamit, in Zahnpasta als Putzkörper, als giftfreies Insektenbekämpfungsmittel in Form von Ungezieferpuder, sowie als reflektierendes Material in der Farbe, die für Fahrbahnmarkierungen im Straßenbau verwendet wird. Außerdem finden Kieselalgen in der forensischen Medizin Verwendung (Diatomeennachweis). Ihre Aussagekraft für den Nachweis eines Ertrinkungstodes wird jedoch kontrovers diskutiert.[10][11]

Insbesondere im 19. Jahrhundert dienten Diatomeen zur Anfertigung ästhetischer mikroskopischer Präparate, deren gemeinsame Betrachtung in Salons ein beliebter Zeitvertreib in höheren gesellschaftlichen Kreisen war. Zur höchsten Perfektion in der handwerklich extrem schwierigen Anfertigung solcher Präparate hat es Johann Diedrich Möller aus Wedel bei Hamburg gebracht.

Marine Diatomeen können zu Vergiftungen bei Mensch und Tier führen, da einige Arten, insbesondere Pseudo-nitzschia, Nitzschia oder Amphora Domoinsäure produzieren.[12] In filtirierende Meerwasser-Organismen, wie z. B. Muscheln, oder in sich von diesen Tieren ernährende Arten, wie z. B. Fischen, können sich diese Diatomeen akkumulieren. Kommt es zum Verzehr solcher mit Domoinsäure angereicherten Organismen durch den Menschen, treten Vergiftungserscheinungen auf, die als Amnesic Shellfish Poisoning (ASP) bezeichnet werden. Als Symptome treten insbesondere Gedächtnisverlust, Übelkeit, Krämpfe, Durchfall, Kopfschmerz und Atembeschwerden auf.[13]

Die Kieselalgen oder Diatomeen (Bacillariophyta) bilden ein Taxon von Photosynthese betreibenden Protisten (Protista) und werden in die Gruppe der Stramenopilen (Stramenopiles) eingeordnet.

Oft wird die Gruppe mit dem synonymen Namen Diatomea Dumortier bezeichnet, alternativ sind auch die synonymen Namen Fragilariophyceae, Diatomophyceae in Verwendung. Einige Autoren nennen die Kieselalgen Bacillariophyceae, sie ordnen sie also als Klasse in die, dann als Phylum aufgefassten photosynthetischen Vertreter der Stramenopiles (Ochrophyta) ein, diese Auffassung wird etwa in den Datenbanken DiatomBase und WoRMS vertreten. Diese Verwendung ist allerdings missverständlich, da andere Taxonomen eine enger abgegrenzte Klasse Bacillariophyceae, als eine von drei Klassen innerhalb der Diatomeen aufführen. Bei Verwendung dieses Namens ist also die jeweilige Auffassung zu kontrollieren, da es sonst zu Missverständnissen kommt.

Man unterscheidet heute rund 6000 Arten. Es wird jedoch angenommen, dass insgesamt bis zu 100.000 Arten existieren. Eine Arbeitsstelle für Diatomeen-Forschung (mit umfangreicher Sammlung und Online-Katalog), begründet von Friedrich Hustedt, befindet sich im Alfred-Wegener-Institut.

Ang mga diatomea (di-tom-os 'gupitin sa kalahati', mula sa diá, 'sa pamamagitan ng' o 'hiwalay' at ang ugat ng tém-n-ō, 'Pinutol ko') ay isang pangunahing pangkat ng algae, partikular na microalgae, na matatagpuan sa mga karagatan, mga daluyan ng tubig at mga soils ng mundo. Ang mga numero ng buhay na diatoms sa trillions: bumubuo sila ng halos 20 porsiyento ng oksiheno na ginawa sa planeta bawat taon, tumagal ng higit sa 6.7 bilyon metrikong toneladang silikon bawat taon mula sa tubig kung saan sila nakatira, at nag-ambag ng halos kalahati ng organiko na materyal na natagpuan sa mga karagatan.

![]() Ang lathalaing ito ay isang usbong. Makatutulong ka sa Wikipedia sa nito.

Ang lathalaing ito ay isang usbong. Makatutulong ka sa Wikipedia sa nito.

Diatoms (diá-tom-os 'cut in hauf', frae diá, 'throu' or 'apairt'; an the ruit o tém-n-ō, 'A cut'.) [10] are a major group o algae,[11] specifically microalgae, foond in the oceans, watterweys an siles o the warld.

Diatom suvoʻtlar (yun. diatomos -teng ikkiga boʻlingan) — kremniyli suvoʻtlar (Bacillariophyta); suv-oʻtlar boʻlimiga mansub. 20 mingga yaqin turi bor. D. s.ning mikroskopik (0,75— 1500 mkm), bir hujayrali, yakka yoki kolonial formalari mavjud. D. s. hujayralari kremniyli ikki pallali qattiq qobiq bilan oʻralgan. Qobiq devorida tashqi muhit bilan moddalar almashinuvi sodir boʻladigan tirqishlar bor. D. s.ning hujayralarida bir yoki bir nechta yadrochali yadro ustida va bir yoki bir nechta sariq-qoʻngʻir xromatoforalar va b. qismlar boʻladi. D. s. boʻlinib koʻpayadi: har bir qiz hujayra ona qobigʻining bir pallasini oladi, boshqasi esa qaytadan oʻsadi, bunda eski yarim palla oʻz chekkasi bilan yangi yarim pallani tutib turadi. D. s koʻpayish meʼyoriga qarab sekin-asta maydalashadi. Maydalashgan hujayralardan ikkitasi bir-biriga yaqinlashib, pallalari ochiladi va ular oʻrtasida konʼyugatsiyaga oʻxshash jarayon sodir boʻladi yoki anizogamiya (baʼzan ooga-miya) orqali jinsiy koʻpayish sodir boʻladi. Zigotasi autosporaga aylanib oʻsadi. Bunday zigota oʻsib, dastlabki hujayralarga nisbatan bir necha marta yirik hujayrani hosil qiladi. Baʼzi turlari tinim davrida spora hosil qiladi. D. s. diploidli, ularning gametalari esa gaploidli. D. s. suv-oʻtlarning tabiatda keng tarqalgan guruhi boʻlib, chuchuk suv va dengizlarda, ayniqsa dengiz tubidagi loyqada, suv oʻsimliklari va toshlar, nam va b. joylarda oʻsadi. Hayvonlarga oziq boʻladi.

Diatom suvoʻtlar (yun. diatomos -teng ikkiga boʻlingan) — kremniyli suvoʻtlar (Bacillariophyta); suv-oʻtlar boʻlimiga mansub. 20 mingga yaqin turi bor. D. s.ning mikroskopik (0,75— 1500 mkm), bir hujayrali, yakka yoki kolonial formalari mavjud. D. s. hujayralari kremniyli ikki pallali qattiq qobiq bilan oʻralgan. Qobiq devorida tashqi muhit bilan moddalar almashinuvi sodir boʻladigan tirqishlar bor. D. s.ning hujayralarida bir yoki bir nechta yadrochali yadro ustida va bir yoki bir nechta sariq-qoʻngʻir xromatoforalar va b. qismlar boʻladi. D. s. boʻlinib koʻpayadi: har bir qiz hujayra ona qobigʻining bir pallasini oladi, boshqasi esa qaytadan oʻsadi, bunda eski yarim palla oʻz chekkasi bilan yangi yarim pallani tutib turadi. D. s koʻpayish meʼyoriga qarab sekin-asta maydalashadi. Maydalashgan hujayralardan ikkitasi bir-biriga yaqinlashib, pallalari ochiladi va ular oʻrtasida konʼyugatsiyaga oʻxshash jarayon sodir boʻladi yoki anizogamiya (baʼzan ooga-miya) orqali jinsiy koʻpayish sodir boʻladi. Zigotasi autosporaga aylanib oʻsadi. Bunday zigota oʻsib, dastlabki hujayralarga nisbatan bir necha marta yirik hujayrani hosil qiladi. Baʼzi turlari tinim davrida spora hosil qiladi. D. s. diploidli, ularning gametalari esa gaploidli. D. s. suv-oʻtlarning tabiatda keng tarqalgan guruhi boʻlib, chuchuk suv va dengizlarda, ayniqsa dengiz tubidagi loyqada, suv oʻsimliklari va toshlar, nam va b. joylarda oʻsadi. Hayvonlarga oziq boʻladi.

Diatoms (diá-tom-os 'cut in hauf', frae diá, 'throu' or 'apairt'; an the ruit o tém-n-ō, 'A cut'.) are a major group o algae, specifically microalgae, foond in the oceans, watterweys an siles o the warld.

Diatomeen (Bacillariophyceae of Bacillariophyta) san algen faan di stam Ochrophyta. Daalang san amanbi 6.000 slacher bekäänd, man diar san wel son 100.000 slacher noch goorei fünjen wurden.

Diatomeen (Bacillariophyceae of Bacillariophyta) san algen faan di stam Ochrophyta. Daalang san amanbi 6.000 slacher bekäänd, man diar san wel son 100.000 slacher noch goorei fünjen wurden.

Dijatomeje (lat. Diatomeae, Bacillariophyceae) su alge kremenjašice iz carstva Protisti. Ćelijska membrana im je inkrustrirana (prožeta) kremenom ili silicij dioksidom , a označava se kao frustulum. Ovi jednoćelijski organizmi sastavljeni su od dvije valve (poklopca): gornje (veće) i donje, koje su međusobno bočno vezane pleurom.[5]

Kremene alge se razmnožavaju vegetativno i spolno. Vegetativnog se odvija tako da se valve razmaknu, protoplazma se podijeli, a zatim i jedro, u procesu mitoze. Obje novonatale ćelije dobiju po jednu roditeljsku valvu, koja postaje gornja ili veća valva, dok manju valvu same obnove. Ovim putem postepeno dolazi do smanjivanja veličine ćelije. Kada to dode do veličine kod koje se ne može dalje dijeliti, nastupa posebni način dijeljenja tzv. auksosporulacija i spolni proces. Auksosporulacija rezultira stvaranjem zigot u vidu velike auksospore koja zatim luči veći oklop. Zapaženo je i spolno razmnožavanje muškim spolnim ćelijama koje imaju po jedan bič. U nepovoljnim uvjetima, stvaraju trajne spore sa tvrdom silificiranom ljušturicom koja kod raznih vrsta ima karakterističe nastavke. Trajne spore padnu na morsko dno gdje mogu preživjeti nepovoljnnu sezonu i uvjete i aktivirati se kada nastupe povoljne okolnosti.

Diatomeje se hrane autotrofno. Sadrže pigmente hlorofil a i c, karotenoidi i ksantofil (fukoksantin). Proizvod fotosinteze je hrizolaminarin, polimer glukoze.

Procjenjuje se da danas na Zemlji ima oko 100 miliona vrsta algi kremenjašica, koje se razvrstavaju u 250 rodova.

Staništa su im razna: na kopnu, u stajaćim i tekućim vodama, u slobodnoj vodi (plankton) ili na dnu (bentos). Mogu i obrastati potopljene predmete različitog porijekla. Općenito naseljavaju hladnija mora, a u toplijim su ćešće zastupljene u hladnijem dijelu godine.

Prema strukturi ljušturice dijele se na

Uginuli organizmi, sa ljušturama padaju na dno, gdje se tokom miliona godina na stvara dijatomejska zemlja. Alge kremenjašice upotrebljavaju se za proizvodnju izolacijskih materijala, izradu paste za zube i brušenje metala.

Dijatomeje (lat. Diatomeae, Bacillariophyceae) su alge kremenjašice iz carstva Protisti. Ćelijska membrana im je inkrustrirana (prožeta) kremenom ili silicij dioksidom , a označava se kao frustulum. Ovi jednoćelijski organizmi sastavljeni su od dvije valve (poklopca): gornje (veće) i donje, koje su međusobno bočno vezane pleurom.

Diatomeo esas familio de algi feofices, od algi bruna.

Τα διάτομα (ομοταξία: Βακιλλαριοφύκη (Bacillariophyceae)) αποτελούν μια πολύ σημαντική ομάδα φυτοπλαγκτικών οργανισμών και είναι άφθονα τόσο στα θαλάσσια οικοσυστήματα όσο και στα εσωτερικά νερά. Πρόκειται για μονοκύτταρα φύκη με κυτταρικό τοίχωμα που εμφανίστηκαν την Ιουρασική περίοδο, πριν από περίπου 185 εκατομμύρια χρόνια. Ο αριθμός των ειδών που ανήκουν στα διάτομα δεν είναι απόλυτα γνωστός, αλλά πιστεύεται ότι σήμερα υπάρχουν περίπου 100.000 είδη, τα μισά από τα οποία είναι θαλάσσια. Είναι μονοκύτταροι ευκαρυωτικοί οργανισμοί, αν και πολλά από αυτά σχηματίζουν αποικίες σε μορφή αλυσίδας ή σε αστερόμορφους και άλλους σχηματισμούς. Ιδιαίτερο χαρακτηριστικό της ομάδας είναι το κυτταρικό τοίχωμα, με βασικό του συστατικό το διοξείδιο του πυριτίου. Οι κοινωνίες των διατόμων συχνά χρησιμοποιούνται ως βιολογικοί δείκτες σε προγράμματα παρακολούθησης της οικολογικής κατάστασης των υδάτων.

Το μέγεθος των οργανισμών κυμαίνεται από 2 έως 200 μm. Τα είδη της ομοταξίας έχουν χρώμα από κίτρινο έως καφέ και οφείλεται στην ύπαρξη των κίτρινων – φαιών καροτινοειδών χρωστικών τους. Οι φωτοσυνθετικές χρωστικές των διατόμων γενικά είναι οι χλωροφύλλες a, c1 και c2, οι β- και ε-καροτίνες και από τις ξανθοφύλλες η φουκοξανθίνη (που δίνει στα διάτομα το χαρακτηριστικό τους χρώμα), η διατοξανθίνη και η διαδινοξανθίνη.

Το χαρακτηριστικό της ομοταξίας είναι το ανάγλυφο κυτταρικό τους τοίχωμα ή θήκη, όπως συχνά ονομάζεται, με κύριο συστατικό του το διοξείδιο του πυριτίου (SiO2). Αποτελείται από μια εσωτερική συνεχή μεμβράνη από πηκτινικές ουσίες και εξωτερικά από δύο κελυφοειδείς θυρίδες οι οποίες εφαρμόζουν μεταξύ τους και η μία είναι ελαφρώς μεγαλύτερη από την άλλη. Η θήκη δεν είναι απλή στη μορφή αλλά διάτρητη και μπορεί να φέρει περίπλοκες δομές όπως ραβδώσεις, αγκάθια, πόρους και προεξοχές. Η θήκη των διατόμων είναι διαφανής και διαπερατή από το φως, ώστε οι οργανισμοί να μπορούν να δεσμεύουν την ηλιακή ενέργεια απαραίτητη για τη φωτοσύνθεση, ενώ οι πόροι επιτρέπουν τη διέλευση των διαλυμένων στο νερό αερίων και των θρεπτικών συστατικών μέσα και έξω από τα κύτταρα. Η περίπλοκη δομή του τοιχώματος των διατόμων αποτελεί σημαντικό διαγνωστικό χαρακτηριστικό για την ταξινόμησή τους σε γένη και είδη.

Τα διάτομα είναι άφθονα στις εύκρατες και πολικές περιοχές, τόσο στα παράκτια όσο και στα ωκεάνια νερά. Γενικά είναι κοινά σε νερά πλούσια σε θρεπτικά συστατικά. Η ομάδα των διατόμων περιλαμβάνει είδη της θάλασσας και των εσωτερικών υδάτων (λίμνες και ποτάμια). Τα περισσότερα διάτομα είναι πλαγκτικά, δηλαδή προσαρμοσμένα να ζουν σε αιώρηση μέσα στο νερό, αλλά πολλά είδη διαθέτουν προσαρμογές και εξαρτήματα που τους επιτρέπουν να προσκολλώνται σε σκληρές επιφάνειες όπως βράχους και σημαδούρες.

Τα διάτομα είναι σημαντικοί πρωτογενείς παραγωγοί στα υδάτινα οικοσυστήματα. Συγκεκριμένα υπολογίζεται ότι το 20 – 25% της συνολικής δέσμευσης του διοξειδίου του άνθρακα πραγματοποιείται από αυτά, ενώ θεωρούνται οι σημαντικότεροι μη προσκολλημένοι πρωτογενείς παραγωγοί της ανοικτής θάλασσας στις εύκρατες και πολικές περιοχές. Λίγα μόνο είδη είναι άχρωμα και ζουν προσκολλημένα πάνω στις επιφάνειες των φυκών ως ετερότροφοι οργανισμοί.

Διάτομα όπως το Biddulphia tridens αποτελούν βασικό παράγοντα που οξυγονώνει την γήινη ατμόσφαιρα ενώ παράλληλα αποτελούν τροφή για πολλά θαλάσσια πλάσματα. Οι βιολόγοι χρησιμοποιούν τα διάτομα όπως το Triceratium castelliferum ως βιοδείκτες για την ποιότητα του νερού μια και είναι ιδιαίτερα ευαίσθητα στις αλλαγές του περιβάλλοντος.

Τα διάτομα συμμετέχουν συχνά σε φαινόμενα «άνθισης του νερού» (ή φυτοπλαγκτικής «άνθισης») - ο αντίστοιχος αγγλικός όρος είναι «water bloom», δηλαδή φαινόμενα κατά τα οποία ορισμένοι φυτοπλαγκτικοί οργανισμοί αυξάνονται ανά περιόδους σε αφθονία και βιομάζα, εξ’ αιτίας της επικράτησης ευνοϊκών συνθηκών στο νερό (διαθεσιμότητα θρεπτικών συστατικών και άλλοι παράγοντες) και το νερό χρωματίζεται ανάλογα με τις φωτοσυνθετικές χρωστικές των οργανισμών που επικρατούν. Τα διάτομα εμφανίζουν φαινόμενα άνθισης τόσο σε λίμνες όσο και σε παράκτιες αλλά και ωκεάνιες περιοχές (για παράδειγμα στον Ατλαντικό ωκεανό) κατά την άνοιξη.

Κάτω από δυσμενείς συνθήκες τα διάτομα έχουν την ικανότητα να σχηματίζουν ανθεκτικές δομές γνωστές ως έμμονα σπόρια, τα οποία διατηρούνται αδρανή όσο οι συνθήκες είναι δυσμενείς, ενώ όταν αυτές γίνουν ξανά ευνοϊκές προκύπτουν πάλι διάτομα από τα σπόρια.

Στο βυθό των θαλασσών σε διάφορες ωκεάνιες περιοχές οι θήκες των νεκρών διατόμων καθιζάνουν, συσσωρεύονται και σχηματίζουν μεγάλες αποθέσεις, γνωστές ως γη των διατόμων. Τα ιζήματα αυτά έχουν πολλές εμπορικές εφαρμογές, όπως κατασκευή φίλτρων, ηχομονωτικών και θερμομονωτικών υλικών, καθαριστικών, αποσμητικών, λειαντικών και πολλών άλλων υλικών.

Η ομοταξία των διατόμων χωρίζεται σε δύο τάξεις:

Μια ακόμη διαφορά ανάμεσα στις δύο κλάσεις αφορά στην εγγενή αναπαραγωγή των οργανισμών: τα κεντρικά διάτομα παράγουν αρσενικούς γαμέτες που φέρουν μαστίγιο και κινούνται, ενώ ο θηλυκός γαμέτης δε φέρει μαστίγιο. Αντίθετα τα πτεροειδή διάτομα παράγουν γαμέτες που δε φέρουν μαστίγια.

Ο πιο κοινός τρόπος αναπαραγωγής για τα διάτομα είναι η αγενής αναπαραγωγή με κυτταρική διαίρεση. Κατά τη διαδικασία αυτή το κάθε νέο κύτταρο φέρει μία θυρίδα από το αρχικό κύτταρο και εκκρίνει μια δεύτερη, μικρότερη θυρίδα. Επαναλαμβανόμενες κυτταρικές διαιρέσεις κατά τις περιόδους ταχείας αναπαραγωγής (γνωστή ως φάση ακμής) με ευνοϊκές συνθήκες στο περιβάλλον (θερμοκρασία, διαθεσιμότητα θρεπτικών κ.α.) οδηγούν σε σταδιακά μικρότερο μέγεθος των διατόμων, κυρίως επειδή το διαλυμένο στο νερό πυρίτιο εξαντλείται κατά την κατασκευή των νέων κυτταρικών τοιχωμάτων, αλλά και επειδή τα κελύφη τους δεν έχουν τη δυνατότητα να μαγαλώσουν. Όταν τα κύτταρα φτάσουν σε ένα ελάχιστο κρίσιμο μέγεθος σχηματίζονται τα αυξοσπόρια (στάδια ήπιας ανακαμπτικής ανάπτυξης), τα οποία σταδιακά αυξάνουν το μέγεθός τους και ανακτάται το κανονικό μέγεθος, ή λαμβάνει χώρα εγγενής αναπαραγωγή, σε συνδυασμό με την επικράτηση ορισμένων απαραίτητων ευνοϊκών συνθηκών στο περιβάλλον, όσον αφορά τη θερμοκρασία, τα θρεπτικά, τα ιχνοστοιχεία και άλλους παράγοντες. Με τη συγχώνευση των δύο γαμετών αναπτύσσεται ένα αυξοσπόριο και το μέγεθος αποκαθίσταται όπως περιγράφηκε προηγουμένως.

Η σημαντικότερη και πιο ισχυρή τοξίνη που παράγουν πολλά διάτομα είναι το Δομοϊκό Οξύ (Domoic Acid, DA). Το δομοϊκό οξύ είναι μια ισχυρή νευροτοξίνη φυκών που παράγεται με φυσικό τρόπο από αρκετά Διάτομα. Συγκεκριμένα, παράγεται από 12 είδη του γένους Pseudo-nitzschia καθώς επίσης και από τα είδη: Amphora coffeaeformis και Nitzschia navis-varingica. Το DA είναι ένα υδατοδιαλυτό, πολικό αμινοξύ που συνδέεται δομικά με το καϊνικό οξύ. Δρα αγωνιστικά με το γλουταμινικό οξύ και έχει εξωτοξική δράση στο Κεντρικό Νευρικό Σύστημα αλλά και στα όργανα που είναι πλούσια σε υποδοχείς του γλουταμινικού στα σπονδυλωτά. Η τοξίνη αυτή είναι υπεύθυνη για μια ασθένεια που προκαλεί στους ανθρώπους, γνωστή ως αμνησιακή δηλητηρίαση οστρακοειδών (Amnesic Shellfish Poisoning, ASP). Αυτή η ασθένεια ταυτοποιήθηκε για πρώτη φορά το 1987, όταν 143 άνθρωποι αρρώστησαν και τέσσερις πέθαναν έπειτα από την κατανάλωση μολυσμένων με δομοϊκό οξύ μυδιών, τα οποία είχαν συλλεχθεί από ειδικές εγκαταστάσεις καλλιέργειάς τους στην ανατολική ακτή του Prince Edward Island στον Καναδά. Αν και έχουν αναγνωριστεί πολλές πηγές του DA και σε Μακροφύκη, τη σημαντικότερη απειλή στην ανθρώπινη υγεία προβάλλουν τα τοξικά είδη των διατόμων εξαιτίας της συσσώρευσης του DA στο σύστημα φιλτραρίσματος της τροφής που διαθέτουν κάποιοι θαλάσσιοι οργανισμοί. Τα κλινικά συμπτώματα της ASP στους ανθρώπους περιλαμβάνουν γαστρεντερική διαταραχή, σύγχυση, αποπροσανατολισμό, επιληπτικές κρίσεις, μόνιμη απώλεια της βραχύχρονης μνήμης και σε πιο ακραίες περιπτώσεις θάνατο.

Οι πληθυσμιακές εκρήξεις των τοξικών διατόμων είναι ένα παγκόσμιο πρόβλημα και φαίνεται να παρουσιάζουν αύξηση τόσο στην συχνότητα όσο και στην τοξικότητα απειλώντας την ανθρώπινη υγεία και την ασφάλεια των θαλασσινών τροφίμων. Εξαιτίας αυτού, έχουν εγκαθιδρυθεί πολλά προγράμματα έρευνας και ελέγχου στην δυτική ακτή των Η.Π.Α. με σκοπό τον εντοπισμό του DA σε οστρακοειδή και παράκτια νερά. Στην Ελλάδα γίνονται κάποια παρόμοια προγράμματα, μικρότερης όμως κλίμακας, κυρίως για ακαδημαϊκούς σκοπούς. Την περίοδο Αυγούστου-Οκτωβρίου 2008, έξι στελέχη του είδους Pseudo-nitzschia pseudodelicatissima απομονώθηκαν από τον Θερμαϊκό κόλπο. Τα στελέχη καλλιεργήθηκαν και υποβλήθηκαν σε ελέγχους για να διαπιστωθεί εάν παρήγαγαν DA. Τελικά εντοπίστηκε η παραγωγή του και στα έξι στελέχη και η μελέτη αυτή επιβεβαίωσε την παραγωγή του δομοϊκού οξέος από το P. pseudodelicatissima. Στη λήψη μέτρων για τον έλεγχο της ανθρώπινης έκθεσης στο DA, ηγετικό ρόλο παίζει ο Καναδάς και ακολουθούν οι: Νορβηγία, Σκωτία, Γαλλία, Ιρλανδία, Πορτογαλία, Ισπανία, Ιαπωνία, Αυστραλία και Νέα Ζηλανδία.

Σε πολλές περιοχές έχουν εδραιωθεί προγράμματα ελέγχου της τοξίνης και η λήψη μέτρων και εκτέλεσή τους, έχει συνδράμει στην αποφυγή νέου –καταγεγραμμένου- περιστατικού από αυτό του 1987. Αν και τα προγράμματα αυτά δείχνουν να είναι αποτελεσματικά στο να αποτρέπουν δηλητηριάσεις, είναι πιθανό να υπάρχουν επιπτώσεις από την επαναλαμβανόμενη μακρόχρονη έκθεση σε μικρή ποσότητα DA που δεν έχουν ακόμα διερευνηθεί. Έχει π.χ. διαπιστωθεί ένα σύνδρομο χρόνιας τοξικότητας του DA σε θαλάσσιους λέοντες οι οποίοι χρησιμοποιούνται ως πειραματικό είδος για την ανίχνευση των πιθανών κινδύνων σε ανθρώπους από την τοξίνη. Επιπλέον, βρίσκεται σε εξέλιξη η δημιουργία ενός σπονδυλωτού μοντέλου που θα επιτρέπει την αξιολόγηση των επιπτώσεων από την επαναλαμβανόμενη μακρόχρονη έκθεση σε χαμηλά επίπεδα DA.

Όπως αναφέρθηκε, ο μεγαλύτερος κίνδυνος έκθεσης σε DA για τους ανθρώπους και τη θαλάσσια πανίδα είναι η διατροφική κατανάλωση από μολυσμένα με τοξίνη θαλασσινά, όπως οστρακοειδή και κάποια είδη ψαριών. Επιπλέον, έχει διαπιστωθεί ότι και οι βενθικοί οργανισμοί στους οποίους συσσωρεύεται το δομοϊκό οξύ μπορούν να δράσουν σημαντικά ως τοξικοί φορείς στην πελαγική τροφική αλυσίδα. Με σκοπό την ενημέρωση των καταναλωτών έχουν διαμορφωθεί πίνακες που αναφέρουν τα είδη των σπονδυλωτών ζώων που μπορεί να είναι φορείς DA εξαιτίας της διατροφής τους. Κάποια ενδεικτικά παραδείγματα τέτοιων οργανισμών είναι: Balaenoptera musculus (μπλε φάλαινα), γένος Delphinus (κοινό δελφίνι), Engraulis mordax (γαύρος), Sardinops sagax (σαρδέλα), Psettichthys melanostictus (γλώσσα) κ.ά.

Μετά το επεισόδιο του 1987 πολυάριθμες έρευνες τοξικότητας διενεργήθηκαν με σκοπό να προσδιοριστεί η δραστικότητα του DA σε διάφορα σπονδυλωτά είδη. Τα μέχρι τώρα δεδομένα δείχνουν ότι οι άνθρωποι είναι πιο ευαίσθητοι στο DA και εμφανίζουν δυσμενή συμπτώματα σε αρκετά χαμηλότερα επίπεδα της τοξίνης έναντι των τρωκτικών και των ψαριών.

Προκειμένου να προστατευτούν οι καταναλωτές των θαλασσινών, έπειτα από το περιστατικό του ASP στον Καναδά το 1987, οι αρχές θέσπισαν ένα όριο για το επίπεδο του DA που ανέρχεται στα 20 μg DA/g ιστού οστρακοειδών. Αν τα επίπεδα του DA υπερβαίνουν αυτό το όριο, τότε είναι δυνατόν αυτό να προκαλέσει την απομόνωση της μολυσμένης παραλίας ή περιοχή καλλιέργειας οστρακοειδών. Το παραπάνω όριο έχει υιοθετηθεί πλέον και από άλλες χώρες και εφαρμόζεται υποχρεωτικά στις Η.Π.Α., Ε.Ε., Νέα Ζηλανδία και Αυστραλία για μια ποικιλία οστρακοειδών όπως τα μύδια, χτένια και στρείδια.

Η μεγάλη αύξηση του ανθρώπινου πληθυσμού και η ανάπτυξη των πόλεων συμβάλλουν στην εξάντληση των φυσικών πόρων, στην αύξηση του κόστους παραγωγής τους και συντελούν στο φαινόμενο της κλιματικής αλλαγής. Για να ξεπεραστούν οι δυσκολίες στον εφοδιασμό του πληθυσμού και να μειωθεί το κόστος των πόρων η επιστημονική κοινότητα στράφηκε σε εναλλακτικές πηγές, όπως τα μικροφύκη (που συμπεριλαμβάνουν και τα διάτομα) χρησιμοποιούν διοξείδιο του άνθρακα (CO2) για να παράγουν βιομάζα ή πολύτιμες ενώσεις.

Τα διάτομα έχουν διαδραματίσει καθοριστικό ρόλο στο οικοσύστημα για εκατομμύρια χρόνια ως μία σημαντική ομάδα παραγωγής οξυγόνου στη γη και ως μία από τις σημαντικότερες πηγές βιομάζας στους ωκεανούς. Τα φύκη καλλιεργούνται εδώ και πολλά χρόνια, αλλά μόλις πρόσφατα συνειδητοποιήθηκε ότι ο ωκεανός είναι μία σχετικά αναξιοποίητη και ανεξερεύνητη πηγή βιομάζας. Χάρη στην αποτελεσματική τους ικανότητα για φωτοσύνθεση, μετατρέπουν την φωτεινή ενέργεια σε χημική ενέργεια και σε οργανικά μόρια όπως οι υδατάνθρακες και τα λιπίδια. Μέχρι πριν από κάποια χρόνια τα διάτομα είχαν περιοριστεί σχεδόν αποκλειστικά στην βασική έρευνα με ελάχιστη εκτίμηση των πρακτικών τους χρήσεων πέρα από τις πιο υποτυπώδεις εφαρμογές. Έχουν καταβληθεί προσπάθειες για την καθιέρωσή τους ως αποφασιστικά χρήσιμες εμπορικές και βιομηχανικές εφαρμογές, αλλά και νανοτεχνολογίας.

Οι βιοτεχνολογικές εφαρμογές είναι πολλές και ιδιαίτερα προσοδοφόρες, κάποιες από αυτές είναι:

Βιομηχανική χρήση: λιπάσματα, υδατάνθρακες για παραγωγή αιθανόλης μέσω ζύμωσης, πρωτεΐνες για παραγωγή μεθανίου μέσω αναερόβιας αεριοποίησης και φυσικά έλαια για παραγωγή βιοντίζελ. Το μεγάλο πλεονέκτημα που διαθέτουν τα διάτομα είναι οι διατροφικές τους συνήθειες, απαιτούν διοξείδιο του άνθρακα, νερό, ανόργανα άλατα και φως για να αναπτυχθούν. Επιπλέον, οι χώροι παραγωγής τους μπορούν να βρίσκονται οπουδήποτε, με αποτέλεσμα να μη στερούν καλλιεργήσιμη γη.

Νανοτεχνολογία: σήμερα τα διάτομα χρησιμοποιούνται ως συστατικά φίλτρων σε διαδικασίες καθαρισμού DNA και απορρόφησης βαρέων μετάλλων. Λόγω του ιδιαίτερου κυτταρικού τοιχώματος θα μπορούσαν μελλοντικά να χρησιμοποιηθούν και σε τσιπ υπολογιστών.

Φαρμακευτική και ιατρική χρήση: εμβόλια αντισώματα, ορμόνες, ένζυμα σκόνη ψύλλων, καλλυντικά και συστατικά οδοντόπαστας.

Διατροφική χρήση: βιταμίνες υψηλής ποιότητας, καθώς είναι πλούσια σε ακόρεστα λιπαρά οξέα και αμινοξέα, επίσης λόγω των υδατανθράκων και των λιπιδίων που παράγουν, μπορούν να αξιοποιηθούν ως τρόφιμα αλλά και ως ζωοτροφές.

Με τα τεχνολογικά άλματα των τελευταίων ετών αλλά και με την μεγάλη ανεκτικότητα σε ποικίλα περιβάλλοντα σε συνδυασμό με την οικονομική αποδοτικότητα, τα διάτομα προσφέρουν ευκαιρίες επαγγελματικές τόσο σε επιστημονικό όσο και σε επιχειρηματικό επίπεδο.

Τα διάτομα (ομοταξία: Βακιλλαριοφύκη (Bacillariophyceae)) αποτελούν μια πολύ σημαντική ομάδα φυτοπλαγκτικών οργανισμών και είναι άφθονα τόσο στα θαλάσσια οικοσυστήματα όσο και στα εσωτερικά νερά. Πρόκειται για μονοκύτταρα φύκη με κυτταρικό τοίχωμα που εμφανίστηκαν την Ιουρασική περίοδο, πριν από περίπου 185 εκατομμύρια χρόνια. Ο αριθμός των ειδών που ανήκουν στα διάτομα δεν είναι απόλυτα γνωστός, αλλά πιστεύεται ότι σήμερα υπάρχουν περίπου 100.000 είδη, τα μισά από τα οποία είναι θαλάσσια. Είναι μονοκύτταροι ευκαρυωτικοί οργανισμοί, αν και πολλά από αυτά σχηματίζουν αποικίες σε μορφή αλυσίδας ή σε αστερόμορφους και άλλους σχηματισμούς. Ιδιαίτερο χαρακτηριστικό της ομάδας είναι το κυτταρικό τοίχωμα, με βασικό του συστατικό το διοξείδιο του πυριτίου. Οι κοινωνίες των διατόμων συχνά χρησιμοποιούνται ως βιολογικοί δείκτες σε προγράμματα παρακολούθησης της οικολογικής κατάστασης των υδάτων.

Дијатомеите[1] или силикатните алги (латински: Bacillariophyceae) се голема група на еукариотски алги со космоплитско распространување. Најголем дел од дијатомеите се едноклеточни, но има и такви кои формираат различни типови на колонии. Имињата на групата доаѓаат од морфологијата и градбата на нивните клеточни ѕидови кои се силикатни и се организирани во форма на кутија и поклопец. При микроскопските анализи вообичаено овие два дела се одвојуваат еден од друг па оттука и нивното име: грчки: διά = "низ" + τέμνειν = "да исечеш", односно "исечи на половина".

Дијатомеите претставуваат многу разнообразна група на организми. Се смета дека постојат над 200 дијатомејски родови и над 100000 рецентни видови.[2][3][4][5] Распространети се вo сите типови на слатководни и морски екосистеми како и на влажни почви. Вообичаено го населуваат пелагијалот на стагнантните води како дел од планктонската заедница (биоценоза) или литоралната зона каде формираат биофилмови на површината на седиментот, таканаречени бентосни заедници. Нивното големо значење особено се изразува во океаните каде се смета дека се одговорни за 45% од примарната продукција.

Дијатомеите се вклучени во групата на хетероконтните алги. Оваа голема подгрупа од протистите (Protista) е дефинирана со присуството на два нееднакви по градба флагелуми, поставени на предната и задната страна на клетката. Иако во адултна форма дијатомеите не поседуваат флагелуми овие структури се вообичаено застапени кај машките гамети кај оние дијатомеи кои се размножуваат со оогамен полов процес. Клетите содржат еден или поголем број жолто-кафеави хлоропласти обвиткани со четири мембрани кои се продукт на секундарна ендосимбиоза на хлоропластот (види Ендосимбиотска теорија). Основните хлорофилни пигменти се a и c, додека најзначаен додатен пигмент е фукоксантинот кој е кафеаво обоен. Резервните хранливи материи се депонираат во форма на хризоламинарин, покрај кој можат да се сретнат и масни капки или волутински гранули.

Клетките ги содржат вообичаените органели типични за останатите еукариотски организми. За нив специфична е везикулата за депозиција на силикат во која се врши синтеза на компонентите на силикатниот клеточен ѕид. Оваа органела е типична и за некои од другите хетероконтни алги кои имаат способност за синтеза на силикатни клеточни ѕидови (на пример, некои групи од златните алги Chysophyceae).

Клеточниот ѕид уште наречен и фрустула е типично граден и по својата комплексност и организација единствен во живиот свет. Составен е од два дела наречени теки кои се однесуваат како кутија и поклопец (хипо- и епитека). Секоја од теките е понатаму поделена на лицев дел или валва и страничен дел или плеура. Самата фрустула со сите компоненти е нераздвојливо споена и клетката е заробена во неа, единствениот момент во кој теките се раздвојуваат е при клеточна делба.

Дијатомеите се неподвижни во адултна форма. Способноста за движење е овозможена со специфичната структура наречена рафа присутна кај одредени групи на пенатни дијатомеи (редот Pennales). Движењето со помош на оваа структура (пукнатина на клеточниот ѕид) е лизгачко по површината на супстратот. Планктонските дијатомеи кои живеат слободно во водениот столб во основа се неподвижни и зависат од водените струи, миксијата и ветровите на површината за нивно придвижување. Покрај рафата на површината на клеточниот ѕид се забележуваат и безброј комплексни перфорации (пори, ареоли, ...) кои овозможуваат прекрасен орнаметиран изглед на клеточниот ѕид и енормна морфолошка варијабилност.

Дијатомеите се диплонтски организми. Во целиот тек на нивниот живот поседуваат два комплети на хромозоми кој број се редуцира само при продукција на гамети.

Имајќи в предвид дека теките се нераздвојливи, клетката во својата стаклена (силикат) кутија има ограничен раст. Со акумулација на резервни материи и самиот раст во фрустулата доаѓа зголемување на тургорниот притисок (тургор) со што се врши силен внатрешен притисок кој условува отварање на теките. Митотската делба се одвива докрај по што двете новодобиени клетки заджуваат една од теките на мајката. Онаа ќерка клетка која ја задржала мајкината епитеката (поголемата тека) формира хипотека, додека пак онаа ќерка клетка која ја задржала мајкината хипотека формира сопствена хипотека (мајкината хипотека во случајот претставува епитека). На ваков начин доаѓа до прогресивно намалување на димензиите на клетките во популацијата, односно како како популацијата расте (старее) така популацијата ја намалува својата големина. Овој процес е познат како правилото на MacDonald и Pfitzer. По поголем број на делби најголемиот дел од клетките во популацијата значајно ги намалуваат своите димензии до состојба кога во рамките клетoчниот ѕид нема повеќе простор за нормална функција. Овој момент во животниот циклус, односно оваа големина на клетките се нарекува долен праг на делба по чиешто достигнување клетката мора да премина на процес на полово размножување. Долниот праг на делба е видово специфичен и различен кај различни видови од истиот род.

Половиот процес настапува кога клетката е на ниво на долниот праг. Вегетативна делба и намалување на димензиите под овој праг вообичаено предизвикуваат губење на способноста за полово размножување. Клетките кои се наоѓаат на овој праг на големина можат да преминат во гаметангиуми односно клетки кои ќе продуцираат гамети. Кај дијатомеите се застапени трите основни типови на полово размножување и тоа оогамија, анизогамија и изогамија при што се продуцираат изогамети, хетерогамети (различни по големина) како и јајце клетка и сперматозоиди кај оогамниот процес. Бројот на гаметите исто така може да варира и тоа од 1 до 8. По завршениот полов процес се добива зигот кој кај дијатомеите има типична градба и функција. Зиготот се нарекува ауксоспора и негова најзначајна функција е враќање на првобитната големина на популацијата од конкретниот вид. Ауксоспората е обвиткана со перизониум, еластична, силикатна обвивка составена од повеќе напречни ленти во форма на прстени и овозможува раст на зиготот во должина. Максималната должина која ја достигнува ауксоспората претставува горниот праг на големина и таа е исто така видово специфична. Зиготот е повторно доплоиден со што самиот вид се враќа кон двојниот број на хромозоми по клетка. По завршувањето на зиготната експанзија се формираат првите, ригидни валви под перизониумот. На ваков начин се добиваат првите адултни единки во популацијата кои се наречени иницијални клетки кои вообичаено имаат чуден, некарактеристичен изглед.

Постојат повеќе различни системи за класификацијата на дијатомеите. Нивниот статус како група (Тип, Класа) се менува често во последно време како ресултат на новите сознанија од молекуларната биологија. Историски, најчесто беа класифицирани како Тип Bacillariophyta, но денес претставуваат класа Bacillariohyceae од Типот хетероконтни алги (Heterokontophyta) во кој се вклучени и на пример Кафеавите алги (Phaeophyceae) и Златните алги (Chrysophyceae).

Без разлика на повисоката класификација, дијатомеите секогаш се поделени врз база на симетријата на нивниот клеточен ѕид. Оттука ќе имаме дијатомеи со радијална симетрија, симетрија во однос на точка, кои се наречени центрични дијатомеи (Centrophyceae или Centrales) и дијатомеи со билатерална симетрија, во однос на права, наречени пенатни дијатомеи (Pennatophyceae или Pennales). Дали центричните или пенатните дијатомеи ќе имаат статус на Класа (ceae) или Ред (ales) зависи од повисоките систематски категории (погл. погоре).

Дијатомеите или силикатните алги (латински: Bacillariophyceae) се голема група на еукариотски алги со космоплитско распространување. Најголем дел од дијатомеите се едноклеточни, но има и такви кои формираат различни типови на колонии. Имињата на групата доаѓаат од морфологијата и градбата на нивните клеточни ѕидови кои се силикатни и се организирани во форма на кутија и поклопец. При микроскопските анализи вообичаено овие два дела се одвојуваат еден од друг па оттука и нивното име: грчки: διά = "низ" + τέμνειν = "да исечеш", односно "исечи на половина".

डायटम (Diatoms)[6] सूक्ष्मशैवालों (microalgae) का प्रमुख समूह है जो सबसे आम पादपप्लवक (phytoplankton) भी हैं।

डायटम (Diatoms) सूक्ष्मशैवालों (microalgae) का प्रमुख समूह है जो सबसे आम पादपप्लवक (phytoplankton) भी हैं।

இருகலப்பாசிகள் (இலங்கை வழக்கு: தயற்றம், ஆங்கிலம்: Diatoms) என்னும் சொல் இரண்டு எனப்பொருள் தரும் கிரேக்க மொழிச்சொற்களில் இருந்து உருவானது:: διά (dia, ட'யா) = "through" ("ஊடே")+ τέμνειν (temnein, டெம்னைன்) = "to cut" ("வெட்டு"), அதாவது "பாதியாய் பகுப்பது" ("cut in half" ) பாசிகளிலேயே மிகவும் தனித்தன்மை கொண்டவை. இவற்றின் அமைப்பு சலவைக் கட்டிகளை இட்டுவைக்கும் டப்பிக்களைப் போல, மேலே ஒரு கலமும் கீழே ஒரு கலமுமாக இருக்கும். இதன் கலங்கள் சிலிக்கா செல்களால் அமைந்தவை. ஒவ்வொறு சிற்றினமும் தங்களுக்கே உரிய பல்வேறு வேலைப்பாடுகள் மிகுந்த கல மேற்கூரையைக் கொண்டிருக்கும். இந்த வேலைப்பாடுகளே ஒரு சிற்றினத்திலிருந்து மற்றொன்றைக் கண்டுபிடிக்க வகைப்பாட்டியலில் உதவுகிறது.இருகலப் பாசிகளில் மட்டும் ஒரு லட்சத்துக்கும் மேற்பட்ட சிற்றினங்கள் உள்ளன.

இருகலப்பாசிகளின் இருப்பு அதனை சுற்றியுள்ள சுற்றுப்புறச்சூழலை பொருத்ததாகும். ஒவ்வொரு சிற்றினமும் தங்களுக்குரிய சூழ்நிலைக்கூறுகளுக்குள் (Ecological Niche) மட்டும் வாழும். இருகலப்பாசிகளின் இத்தகைய பண்புகள் இவற்றை மிகவும் சிறந்த உயிர் சுட்டிக்காட்டியாக (Bioindicator) உபயோகிக்க உதவுகின்றது. இருகல பாசிகளின் கல அமைப்பு சிலிகாவாலனது, அவை நைட்ரிக் அமிலத்தையும் எதிர்த்து நிற்க கூடியது. ஒவ்வொரு நீர் நிலையில் உள்ள இருகல பாசியின் வடிவமும் தனி தன்மை உடையது. அது மட்டுமின்றி ஒரே நீர் நிலையில் வெவ்வேறு கால நிலைகளில் வெவ்வேறு வடிவ இருகலப்பாசிகள் காணப்படும்.

இந்தியாவில் பாசிகளை பற்றிய ஆராய்ச்சியை தொடங்கியவர் சென்னையை சேர்ந்த எம்.ஓ.பி. ஐயங்கார். இவர் இந்திய பாசியியல் துறையின் தந்தை எனப் போற்றப்படுபவர். இவர் அனைத்து வகையான பாசிகளைப் பற்றிய ஆராய்ச்சியை தொடங்கினாலும். "இருகலப் பாசிகள்" பற்றிய ஆராய்ச்சியை இவரது மாணவர்கள் தொடங்கி வைத்தனர். இவரை தொடர்ந்து டி.வி. தேசிகாச்சாரி, குசராத்தை சேர்ந்த எச்.பி. காந்தி, மகாராட்டிராவை சேர்ந்த பி.டி. சரோட் மற்றும் என். டி. காமத் என்பவர்கள் இந்தியாவில் காணப்படும் இருகலப் பாசிகளை பற்றிய ஆராய்ச்சியை தொடர்ந்தார்கள்.

ஒருவர் நீரில் மூழ்கி இறக்கும் போது இருகலப் பாசிகள் நுரையீரலில் உள்ள காற்றுப் பைகள் வெடிப்பதன் மூலம் குருதி ஓட்டத்திற் கலந்து உடலின் பல்வேறு திசுக்களை அடைகின்றன. குறிப்பாக, என்பு மச்சையில் இவற்றின் இருப்பை தடயவியல் வல்லுநர்கள் பரிசோதிப்பர். ஒருவரை வேறு ஏதேனும் வழியிற் கொன்று விட்டு நீரிற் தூக்கிப் போட்டிருப்பின், அவரது எலும்பு மச்சையில் இருகலப்பாசி இருக்காது. ஏனென்றால் இருகலப்பாசி என்பு மச்சையை அடைய உயிருள்ள குருதி ஓட்டம் தேவை.

இருகலப்பாசிகள் (இலங்கை வழக்கு: தயற்றம், ஆங்கிலம்: Diatoms) என்னும் சொல் இரண்டு எனப்பொருள் தரும் கிரேக்க மொழிச்சொற்களில் இருந்து உருவானது:: διά (dia, ட'யா) = "through" ("ஊடே")+ τέμνειν (temnein, டெம்னைன்) = "to cut" ("வெட்டு"), அதாவது "பாதியாய் பகுப்பது" ("cut in half" ) பாசிகளிலேயே மிகவும் தனித்தன்மை கொண்டவை. இவற்றின் அமைப்பு சலவைக் கட்டிகளை இட்டுவைக்கும் டப்பிக்களைப் போல, மேலே ஒரு கலமும் கீழே ஒரு கலமுமாக இருக்கும். இதன் கலங்கள் சிலிக்கா செல்களால் அமைந்தவை. ஒவ்வொறு சிற்றினமும் தங்களுக்கே உரிய பல்வேறு வேலைப்பாடுகள் மிகுந்த கல மேற்கூரையைக் கொண்டிருக்கும். இந்த வேலைப்பாடுகளே ஒரு சிற்றினத்திலிருந்து மற்றொன்றைக் கண்டுபிடிக்க வகைப்பாட்டியலில் உதவுகிறது.இருகலப் பாசிகளில் மட்டும் ஒரு லட்சத்துக்கும் மேற்பட்ட சிற்றினங்கள் உள்ளன.

இருகலப்பாசிகளின் இருப்பு அதனை சுற்றியுள்ள சுற்றுப்புறச்சூழலை பொருத்ததாகும். ஒவ்வொரு சிற்றினமும் தங்களுக்குரிய சூழ்நிலைக்கூறுகளுக்குள் (Ecological Niche) மட்டும் வாழும். இருகலப்பாசிகளின் இத்தகைய பண்புகள் இவற்றை மிகவும் சிறந்த உயிர் சுட்டிக்காட்டியாக (Bioindicator) உபயோகிக்க உதவுகின்றது. இருகல பாசிகளின் கல அமைப்பு சிலிகாவாலனது, அவை நைட்ரிக் அமிலத்தையும் எதிர்த்து நிற்க கூடியது. ஒவ்வொரு நீர் நிலையில் உள்ள இருகல பாசியின் வடிவமும் தனி தன்மை உடையது. அது மட்டுமின்றி ஒரே நீர் நிலையில் வெவ்வேறு கால நிலைகளில் வெவ்வேறு வடிவ இருகலப்பாசிகள் காணப்படும்.

ಡಯಾಟಮ್ ಒಂದು ಪ್ರಮುಖ ಯುಕಾರ್ಯೊಟ (ಕೋಶಬೀಜ ಇರುವ ಜೀವ) ಶೈವಲ ಹಾಗೂ ಸಾಮಾನ್ಯ ಸಸ್ಯ ಪ್ಲವಕ ದಲ್ಲಿ ಒಂದು ವಿಧ. ಪ್ರಮುಖವಾಗಿ ಎಲ್ಲಾ ಡಯಾಟಮ್ಗಳು ಏಕಕೋಶ ಜೀವಿಗಳಾಗಿದ್ದರೂ, ತಾಮ್ಡೆಯಲಲ್ಲಿ ಕಂಡುಬರುತ್ತವೆ. ತಾಮ್ಡಯ ಆಕಾರವು ಎಳೆ ಅಥವಾ ಪಟ್ಟಿ (ಉ.ಹ. Fragillaria), ಬೀಸಣಿಗೆ (Meridion), ವಕ್ರವಾದ (Tabellaria), ಅಥವಾ ನಕ್ಷತ್ರಾಕಾರದಲ್ಲಿ (Asterionella) ಕಂಡುಬರುತ್ತದೆ. ಈ ಸಸ್ಯಗಳು ದ್ಯುತಿ ಸಂಶ್ಲೇಷಣೆಯಿಂದ ಆಹಾರವನ್ನು ತಯಾರಿಸುತ್ತವೆ. ಡಯಾಟಮ್ ಕೋಶಬಿತ್ತಿಯು ಎರಡು ಕವಾಟಗಳಿಂದ ಮಾಡಲ್ಪಟ್ಟಿದೆ. ಕವಾಟಗಳು ಸಿಲಿಕಾದಿಂದ ಕೂಡಿದ್ದು, ಒಂದು ಇನ್ನೊಂದನ್ನು ಮುಚ್ಚಿರುತ್ತದೆ. ಇವು ಡಬ್ಬಿಯಂತೆ ಕಾಣುತ್ತವೆ.ಈ ಕವಾಟಗಳಿಗೆ ಪ್ರೊಸ್ಥುಲ್ ಗಳೆಂದು ಕರೆಯುತ್ತಾರೆ. ಡಯಾಟಮ್ ಗಳು ಪ್ರಪಂಚದ ಎಲ್ಲಾ ಭಾಗಗಳಲ್ಲಿಯೂ ಕಂಡುಬರುತ್ತವೆ. ಸಿಹಿನೀರು ಮತ್ತು ಸಾಗರ ವ್ಯೆವಸ್ಥೆಗಳೆರಡರಲ್ಲೂ ಜೀವಿಸುತ್ತವೆ. ಡಯಾಟಮ್ ಗಳು ಜಲ ಆಹಾರ ಸರಪಣಿಯ ಅತಿ ಮುಖ್ಯ ಕೊಂಡಿಗಳು.

ඩයටම් බැසිලාරියෝෆීටා වංශයට අයත් වේ. කරදිය ප්රාථමික නිපැයුම් ප්රජාවේ ප්රධාන ස්ථානයක් ගනී. 7/10ක් කරදිය වේ. මිරිදිය, කරදිය මතුපිට ස්ථරවල ඒක සෛලීය ප්රභා ස්වයංපෝෂී වේ. සෛල බිත්තිය සෙලියුලෝස්, පෙක්ටීන් හා ප්රධාන වශයෙන් සිලිකන් ඇත. දර්ශීය ජීවියා පිනියුලේරියා වේ.

මොවුන්ගේ විශේෂිත ම ලක්ෂණය සෛල වටා ඇති අලංකාර පාරදෘෂ්ය සිලිකන් කවචය යි. එක මත එක පිහිටි දෙපියනකින් යුතු ය. කවචයේ ඇති තන්තු ආධාරයෙන් චලනය විය හැක. ක්ලෝරොෆීල් A, B, හා කැරොටිනොයිඩ ඇත. ප්රභාසංස්ලේෂක වර්ණය ෆියුකොසැන්තීන් වේ. සංචිත ආකාරය ක්රිසොලැමිනරීන් වේ.

අලිංගිකව ද්විඛණ්ඩනයෙන් ප්රජනනය කරන අතර ලිංගිකව ඌනන විභාජනයෙන් කශිකා සහිත සචල පුංජන්මාණුවක් හා අචල ඩිම්බ සාදයි. පුං ජන්මාණුවට තනි කශිකාවක් ඇත.

ඩයටම් බැසිලාරියෝෆීටා වංශයට අයත් වේ. කරදිය ප්රාථමික නිපැයුම් ප්රජාවේ ප්රධාන ස්ථානයක් ගනී. 7/10ක් කරදිය වේ. මිරිදිය, කරදිය මතුපිට ස්ථරවල ඒක සෛලීය ප්රභා ස්වයංපෝෂී වේ. සෛල බිත්තිය සෙලියුලෝස්, පෙක්ටීන් හා ප්රධාන වශයෙන් සිලිකන් ඇත. දර්ශීය ජීවියා පිනියුලේරියා වේ.

A diatom (Neo-Latin diatoma)[a] is any member of a large group comprising several genera of algae, specifically microalgae, found in the oceans, waterways and soils of the world. Living diatoms make up a significant portion of the Earth's biomass: they generate about 20 to 50 percent of the oxygen produced on the planet each year,[10][11] take in over 6.7 billion tonnes of silicon each year from the waters in which they live,[12] and constitute nearly half of the organic material found in the oceans. The shells of dead diatoms can reach as much as a half-mile (800 m) deep on the ocean floor, and the entire Amazon basin is fertilized annually by 27 million tons of diatom shell dust transported by transatlantic winds from the African Sahara, much of it from the Bodélé Depression, which was once made up of a system of fresh-water lakes.[13][14]

Diatoms are unicellular organisms: they occur either as solitary cells or in colonies, which can take the shape of ribbons, fans, zigzags, or stars. Individual cells range in size from 2 to 200 micrometers.[15] In the presence of adequate nutrients and sunlight, an assemblage of living diatoms doubles approximately every 24 hours by asexual multiple fission; the maximum life span of individual cells is about six days.[16] Diatoms have two distinct shapes: a few (centric diatoms) are radially symmetric, while most (pennate diatoms) are broadly bilaterally symmetric. A unique feature of diatom anatomy is that they are surrounded by a cell wall made of silica (hydrated silicon dioxide), called a frustule.[17] These frustules have structural coloration due to their photonic nanostructure, prompting them to be described as "jewels of the sea" and "living opals". Movement in diatoms primarily occurs passively as a result of both ocean currents and wind-induced water turbulence; however, male gametes of centric diatoms have flagella, permitting active movement to seek female gametes. Similar to plants, diatoms convert light energy to chemical energy by photosynthesis, but their chloroplasts were acquired in different ways.[18]