en

names in breadcrumbs

Conservation of the European bison, especially in Poland, has a long history. From the 15th to the 18th centuries, Bialowieza was a royal hunting forest and its game were fed in winter and protected. In the 19th century, under Russian control, the animals of the forest were exploited and their numbers were reduced (a few species even went extinct). World War I was extremely unkind to the bison, with many killed by troops and poachers. Early in this century, the last European bison in the wild was killed by a poacher. Almost immediately, a captive breeding program was instituted with zoo animals. These animals surprisingly survived World War II virtually unharmed, and the 1950's the first animals were released. The herd began to grow, and soon individuals were transported to other areas in order to keep any infectious disease from wiping out the entire population. Because natural mortality of these animals is so low, culling has become necessary. Pucek (1984) has pointed out that herd management is now more important than further increasing bison numbers. The most recent estimate available for the world population of B. bonasus was 3200 individuals (as of 1994). All of these animals are descended from 12 individuals. As might be expected, European bison are quite inbred. It has been shown that increasing the amount of inbreeding in these animals decreases their lifespan, increases juvenile mortality, and increases intercalf intervals. However, it does not seem to significantly affect age at first calving or the number of calves a cow is expected to give birth to during her lifetime. Related to the issue of inbreeding is the issue of genetic variability. An earlier study (Gebczynski and Tomaszewska-Guszkiewicz, 1987) demonstrated that variability in Bison bonasus was approximately the same as that in B. bison, even though the latter has not experienced a bottleneck of nearly the severity of that experienced by the former. A more recent study (Hartl and Pucek, 1994), utilizing a larger sample size and somewhat different methods, has concluded that genetic variability in B. bonasus was reduced by the bottleneck and that the "average heterozygosity" measure used by Gebczynski and Tomaszewska-Guszkiewicz (1987) is not sufficient to document genetic variability in populations that have experienced such a severe bottleneck.

European bison populations now exist on the British Isles as well as in North America and Asia. There are currently 200 European bison breeding centers found in 27 countries worldwide. However, as mentioned above, B. bonasus is only found in its native habitat in a few places. Poland in particular has four reserves containing bison, the largest of which is the Bialowieza Forest on the border with Russia. Virtually all of the work on the behavior and ecology of B. bonasus summarized in this species account was done in Bialowieza.

((Anonymous, 1981; Gebczynski and Tomaszewska-Guszkiewicz, 1987; Hartl and Pucek, 1994; Jedrzejewski et al., 1992; Krasinska et al., 1987; Okarma et al., 1995; Olech, 1987; Pucek, 1984; Sokolowski, 1983)

US Federal List: no special status

CITES: no special status

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: vulnerable

European bison are smaller than their American counterparts, with adult females ranging from 300-540 kg and adult males from 400-920 kg. They have shorter hair in the neck region as well, which further contributes towards a smaller appearance. However, their pelage appears nearly the same color as their American relatives, and their horns are well-developed. Males and females are dimorphic not only in body size but in skull growth and allometry, as well as in some physiological parameters. Pictures of European bison are available in Sokolowski (1983). (Gill, 1990; Jedrzejewski et al., 1992; Kobrynczuk and Roskosz, 1980; Sokolowski, 1983)

Range mass: 300 to 920 kg.

Other Physical Features: endothermic ; homoiothermic; bilateral symmetry

Average lifespan

Status: wild: 27.0 years.

The natural habitat of European bison is temperate coniferous forest like Bialowieza. For feeding, they prefer areas of vegetation at least 20 years old. (Jedrzejewski et al., 1992; Krasinska et al., 1987; Okarma et al., 1995)

Terrestrial Biomes: forest

Bison bonasus, the European bison or wisent, has been restricted to mainland Europe throughout its history. (Anonymous, 1981; Sokolowski, 1983)

Biogeographic Regions: palearctic (Native )

The diet of B. bonasus varies seasonally. As discussed in sections below, bison aggregate into large groups during the winter, normally around areas where humans regularly place hay for them. Supplementing the diet of the bison this way may not be necessary for their survival, but has been done since the days when Bialowieza and its animals were protected by Polish or Lithuanian royalty, and continues as tradition. During the rest of the year, the bison are primarily grazers (accounting for 95% of feeding time), though they occasionally browse (3%) or eat bark (2%). The latter activity occurs mainly in early spring, when neither graze nor browse is available in large quantities. During the summer, when food is most plentiful, adult males may consume 32 kg of food per day, and adult females 23 kg per day. Borowski et al. (1967) present a list of specific food items utilized by B. bonasus in Bialowieza. Gebczynska et al. (1991) provide both an updated estimate of the number of plant species used by bison (110-140 species) and an analysis of seasonal variation in bison diets, based on rumen contents of culled animals. Their data are as follows: in spring (April-May), bison diet consists of: 8.8% trees; 0.1% bushes; 65.5% grasses and sedges; 1.5% herbaceous plants; and 24.1% mosses, pteridophytes, fungi, and unidentifiable food items. In summer (June-August), bison diet consists of: 9.8% trees; 1.4% bushes; 68.6% grasses and sedges; 1.7% herbaceous plants; and 18.5% mosses, pteridophytes, fungi, and unidentifiable food items. In autumn (September-October), bison diet consists of: 4.3% trees; 0.6% bushes; 69.9% grasses and sedges; 6.7% herbaceous plants; and 18.1% mosses, pteridophytes, fungi, and unidentifiable food items. In winter (November-March), bison diet consists of: 7.4% trees; 0.2% bushes; 72.4% grasses and sedges; 0.9% herbaceous plants; and 19.1% mosses, pteridophytes, fungi, and unidentifiable food items. Unlike certain other large ungulates, bison feeding tends not to greatly alter the habitat, except during winter aggregations of large groups and near popular watering places. (Borowski et al., 1967; Cabon-Raczynska et al., 1983; 1987; Gebczynska et al., 1991; Krasinska et al., 1987; Pucek, 1984)

European bison may provide an economic benefit in that a portion of Bialowieza Forest is set aside for tourists. In addition, European bison may mate with domestic cows. Male hybrids are sterile, but backcrossing may be used to produce fertile males. These animals may be raised for meat. (Korwin-Kossakowski and Saminski, 1984; Sokolowski, 1983)

Positive Impacts: food

Because this species is so restricted in habitat, it does not seem to have any negative economic effects on humans. In addition, European bison are usually not aggressive. They ordinarily flee from humans, and in the winter (perhaps because they associate humans with their food source) they permit observation. However, cows with calves and bulls during the rutting season may be dangerous, and attacks have occurred. (Cabon-Raczynska et al., 1983; 1987)

Perception Channels: tactile ; chemical

Bison share Bialowieza Forest with other herbivores like deer, omnivores like wild boar, and carnivores like wolves and lynx. Some reports from the last century document attacks on bison by wolves or by brown bear (now extinct in the forest), but currently (and unlike their American counterparts) wolves do not prey upon bison in Bialowieza. Unlike American bison, European bison form only a small part of the ungulate community in their habitat. Since most other ungulates are less formidable than the bison, wolves and other predators prefer to attack these others. Most non-culling mortality of bison in Bialowieza is the result of disease (79%) or poaching (14%). Natural mortality is only 3%, and this is attributed to both the lack of natural predators and to the abundant food supply in winter provided by humans. Much more literature than has been surveyed here is available on certain topics, especially hybridization of bison with domestic cows, care and behavior of captive animals, and physiology. The journal "Acta Theriologica" has a very large number of papers on all aspects of European bison, and papers by J. Gill in the journal "Comparative Physiology and Biochemistry Part A: Physiology" provide more information on physiology.

Rutting season for free European bison is from August to October. Seasonal variation in herd structure is closely tied to the reproductive cycle (see "Behavior" section below). Bulls move between female groups, looking for cows in estrous. When they find a cow, they will often "attend" her for at least a day before mating. Bulls stay near the cow, prevent her from rejoining her herd, and prevent other males from approaching her. Fights between bulls occur at this and occasionally serious injury results. After the bull mates with the cow, he shows no more interest in her. Both bulls and cows spend less time resting and feeding during the rutting season than during the rest of the year. Pregnancy lasts about nine months. Most calving occurs in May-July. Cows leave the herd to give birth. Calves are able to run only a few hours after being born. Lactation occurs for approximately one year, but may go into the second year if the cow does not have new young. Both males and females reach sexual maturity at 3-4 years of age. Cows usually calve for the first time at about this age; bulls may have to wait until they are somewhat older to mate successfully. Cows give birth every year or at most every other. They remain fertile into their early 20's. Bulls tend to remain fertile for the rest of their lives. Lifespan seems to be around 25 years.

(Cabon-Raczynska et al., 1987; Krasinska et al, 1987; Krasinski and Raczynski, 1967; Pucek, 1984)

Range number of offspring: 1 to 2.

Average number of offspring: 1.

Range gestation period: 8.53 to 9.43 months.

Average gestation period: 8.83 months.

Range weaning age: 7 to 12 months.

Key Reproductive Features: gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); sexual

Average birth mass: 23375 g.

Average number of offspring: 1.

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male)

Sex: male: 730 days.

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female)

Sex: female: 730 days.

Parental Investment: altricial

The European bison (PL: bison) (Bison bonasus) or the European wood bison, also known as the wisent[a] (/ˈviːzənt/ or /ˈwiːzənt/), the zubr[b] (/zuːbər/), or sometimes colloquially as the European buffalo,[c] is a European species of bison. It is one of two extant species of bison, alongside the American bison. The European bison is the heaviest wild land animal in Europe, and individuals in the past may have been even larger than their modern-day descendants. During late antiquity and the Middle Ages, bison became extinct in much of Europe and Asia, surviving into the 20th century only in northern-central Europe and the northern Caucasus Mountains. During the early years of the 20th century, bison were hunted to extinction in the wild.

The species — now numbering several thousand and returned to the wild by captive breeding programmes — is no longer in immediate danger of extinction, but remains absent from most of its historical range. It is not to be confused with the aurochs (Bos primigenius), the extinct ancestor of domestic cattle, with which it once co-existed.

Besides humans, bison have few predators. In the 19th century, there were scattered reports of wolves, lions, tigers, and bears hunting bison. In the past, especially during the Middle Ages, humans commonly killed bison for their hide and meat. They used their horns to make drinking horns.

European bison were hunted to extinction in the wild in the early 20th century, with the last wild animals of the B. b. bonasus subspecies being shot in the Białowieża Forest (on today's Belarus–Poland border) in 1921. The last of the Caucasian wisent subspecies (B. b. caucasicus) was shot in the northwestern Caucasus in 1927.[4] The Carpathian wisent (B. b. hungarorum) had been hunted to extinction by 1852.

The Białowieża or lowland European bison was kept alive in captivity, and has since been reintroduced into several countries in Europe. In 1996, the International Union for Conservation of Nature classified the European bison as an endangered species, no longer extinct in the wild. Its status has improved since then, changing to vulnerable and later to near-threatened.

European bison were first scientifically described by Carl Linnaeus in 1758. Some later descriptions treat the European bison as conspecific with the American bison. Three subspecies of the European bison existed in the recent past, but only one, the nominate subspecies (B. b. bonasus), survives today. The ancestry and relationships of the wisent to fossil bison species remain controversial and disputed.

The European bison is one of the national animals of Poland and Belarus.[5][6]

The ancient Greeks and ancient Romans were the first to name bison as such; the 2nd-century AD authors Pausanias and Oppian referred to them as Hellenistic Greek: βίσων, romanized: bisōn.[7] Earlier, in the 4th century BC, during the Hellenistic period, Aristotle referred to bison as βόνασος, bónasos.[7] He also noted that the Paeonians called it μόναπος (monapos).[8] Claudius Aelianus, writing in the late 2nd or early 3rd centuries AD, also referred to the species as βόνασος, and both Pliny the Elder's Natural History and Gaius Julius Solinus used Latin: bĭson and bonāsus.[7] Both Martial and Seneca the Younger mention bison (pl. bisontes).[7] Later Latin spellings of the term included visontes, vesontes, and bissontes.[7]

John Trevisa is the earliest author cited by the Oxford English Dictionary as using, in his 1398 translation of Bartholomeus Anglicus's De proprietatibus rerum, the Latin plural bisontes in English, as "bysontes" (Middle English: byſontes and bysountes).[7] Philemon Holland's 1601 translation of Pliny's Natural History, referred to "bisontes". The marginalia of the King James Version gives "bison" as a gloss for the Biblical animal called the "pygarg" mentioned in the Book of Deuteronomy.[7] Randle Cotgrave's 1611 French–English dictionary notes that French: bison was already in use, and it may have influenced the adoption of the word into English, or alternatively it may have been borrowed direct from Latin.[7] John Minsheu's 1617 lexicon, Ductor in linguas, gives a definition for Bíson (Early Modern English: "a wilde oxe, great eied, broad-faced, that will neuer be tamed").[7]

In the 18th century the name of the European animal was applied to the closely related American bison (initially in Latin in 1693, by John Ray) and the Indian bison (the gaur, Bos gaurus).[7] Historically the word was also applied to Indian domestic cattle, the zebu (B. indicus or B. primigenius indicus).[7] Because of the scarcity of the European bison the word 'bison' was most familiar in relation to the American species.[7]

By the time of the adoption of 'bison' into Early Modern English, the early medieval English name for the species had long been obsolete: the Old English: wesend had descended from Proto-Germanic: *wisand, *wisund and was related to Old Norse: vísundr.[7] The word 'wisent' was then borrowed in the 19th century from modern German: Wisent [ˈviːzɛnt], itself related to Old High German: wisunt, wisent, wisint, and to Middle High German: wisant, wisent, wisen, and ultimately, like the Old English name, from Proto-Germanic.[9] The Proto-Germanic root: *wis-, also found in weasel, originally referred to the animal's musk.

The word 'zubr' in English is a borrowing from Polish: żubr [ʐubr], previously also used to denote one race of the European bison.[10][11] The Polish żubr is similar to the word for the European bison in other modern Slavic languages, such as Upper Sorbian: žubr and Russian: зубр. The noun for the European bison in all living Slavonic tongues is thought to be derived from Proto-Slavic: *zǫbrъ ~ *izǫbrъ, which itself possibly comes from Proto-Indo-European: *ǵómbʰ- for tooth, horn or peg.[12]

The European bison is the heaviest surviving wild land animal in Europe. Similar to their American cousins, European bison were potentially larger historically than remnant descendants;[13] modern animals are about 2.8 to 3.3 m (9.2 to 10.8 ft) in length, not counting a tail of 30 to 92 cm (12 to 36 in), 1.8 to 2.1 m (5.9 to 6.9 ft) in height, and 615 to 920 kg (1,356 to 2,028 lb) in weight for males, and about 2.4 to 2.9 m (7.9 to 9.5 ft) in body length without tails, 1.69 to 1.97 m (5.5 to 6.5 ft) in height, and 424 to 633 kg (935 to 1,396 lb) in weight for females.[13] At birth, calves are quite small, weighing between 15 and 35 kg (33 and 77 lb). In the free-ranging population of the Białowieża Forest of Belarus and Poland, body masses among adults (aged 6 and over) are 634 kg (1,398 lb) on average in the cases of males, and 424 kg (935 lb) among females.[14][15] An occasional big bull European bison can weigh up to 1,000 kg (2,200 lb) or more[16][17][18] with old bull records of 1,900 kg (4,200 lb) for lowland wisent and 1,000 kg (2,200 lb) for Caucasian wisent.[13]

On average, it is lighter in body mass, and yet slightly taller at the shoulder, than its American relatives, the wood bison (Bison bison athabascae) and the plains bison (Bison bison bison).[19] Compared to the American species, the wisent has shorter hair on the neck, head, and forequarters, but longer tail and horns. See differences from American bison.

The European bison makes a variety of vocalisations depending on its mood and behaviour, but when anxious, it emits a growl-like sound, known in Polish as chruczenie ([xrutʂɛɲɛ]). This sound can also be heard from wisent males during the mating season.[20]

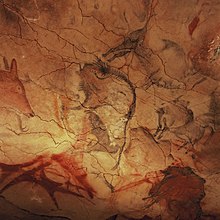

Historically, the lowland European bison's range encompassed most of the lowlands of northern Europe, extending from the Massif Central to the Volga River and the Caucasus. It may have once lived in the Asiatic part of what is now the Russian Federation, reaching to Lake Baikal and Altai Mountains in east.[22] The European bison is known in southern Sweden only between 9500 and 8700 BP, and in Denmark similarly is documented only from the Pre-Boreal.[23] It is not recorded from the British Isles, nor from Italy or the Iberian Peninsula,[24] although prehistorical absence of the species among British Isles is debatable; bison fossils of unclarified species have been found on Doggerland or Brown Bank, and Isle of Wight and Oxfordshire, followed by fossil records of Pleistocene woodland bison and Steppe bison from the isles.[25][26][27][28][29] The extinct Steppe bison (B. priscus) is known from across Eurasia and North America, last occurring 7,000 BC[30] to 5,400 BC,[31] and is depicted in the Cave of Altamira and Lascaux. The Pleistocene woodland bison (B. schoetensacki), has been proposed to have last existed around 36,000 BC.[29] But other authors restrict B. schoetensacki to remains that are hundreds of thousands of years older.[32] Cave paintings appear to distinguish between B. bonasus and B. priscus.[33]

Within mainland Europe, its range decreased as human populations expanded and cut down forests. They seemed to be common in Aristotle's period on Mount Mesapion (possibly the modern Ograzhden).[8] In the same wider area Pausanias calling them Paeonian bulls and bisons, gives details on how they were captured alive; adding also the fact that a golden Paeonian bull head was offered to Delphi by the Paeonian king Dropion (3rd century BC) who lived in what is today Tikveš.[34] The last references (Oppian, Claudius Aelianus) to the animal in the transitional Mediterranean/Continental biogeographical region in the Balkans in the area of modern borderline between Greece, North Macedonia and Bulgaria date to the 3rd century AD.[35][36] In northern Bulgaria, the wisent survived until the 9th or 10th century AD.[37] There is a possibility that the species' range extended to East Thrace during the 7th – 8th century AD.[38] Its population in Gaul was extinct in the 8th century AD. The species survived in the Ardennes and the Vosges Mountains until the 15th century.[39] In the Early Middle Ages, the wisent apparently still occurred in the forest steppes east of the Urals, in the Altai Mountains, and seems to have reached Lake Baikal in the east. The northern boundary in the Holocene was probably around 60°N in Finland.[40] European bison survived in a few natural forests in Europe, but their numbers dwindled.

In 1513 the Białowieża Forest, at this point one of the last areas on Earth where the European bison still roamed free, was transferred from the Troki Voivodeship of Lithuania to the Podlaskie Voivodeship, which after the Union of Lublin became part of the Polish Crown. In the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, at first European bison in the Białowieża Forest were legally the property of the Grand Dukes of Lithuania and later belonged to the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland. Polish-Lithuanian rulers took measures to protect the European bison, such as King Sigismund II Augustus who instituted the death penalty for poaching bison in Białowieża in the mid-16th century. Wild European bison herds existed in the forest until the mid-17th century. In 1701, King Augustus II the Strong greatly increased protection over the forest; the first written sources mentioning the use of some forest meadows for the production of winter fodder for the bison come from this period.[41] In the early 19th century, after the partitions of the Polish Commonwealth, the Russian tsars retained old Polish-Lithuanian laws protecting the European bison herd in Białowieża but also turned all the people inhabiting the area into serfs. Despite these measures and others, the European bison population continued to decline over the following century, with only Białowieża and Northern Caucasus populations surviving into the 20th century.[42][43] The last European bison in Transylvania died in 1790.[44]

During World War I, occupying German troops killed 600 of the European bison in the Białowieża Forest for sport, meat, hides and horns.[42] A German scientist informed army officers that the European bison were facing imminent extinction, but at the very end of the war, retreating German soldiers shot all but nine animals.[42][43] The last wild European bison in Poland was killed in 1921. The last wild European bison in the world was killed by poachers in 1927 in the western Caucasus. By that year, 48[45] remained, all held by zoos. The International Society for the Preservation of the Wisent was founded on 25 and 26 August 1923 in Berlin, following the example of the American Bison Society. The first chairman was Kurt Priemel, director of the Frankfurt Zoo, and among the members were experts like Hermann Pohle, Max Hilzheimer and Julius Riemer. The first goal of the society was to take stock of all living bison, in preparation for a breeding programme. Important members were the Polish Hunting Association and the Poznań zoological gardens, as well as a number of Polish private individuals, who provided funds to acquire the first bison cows and bulls. The breeding book was published in the company's annual report from 1932. While Priemel aimed to grow the population slowly with pure conservation of the breeding line, Lutz Heck planned to grow the population faster by cross-breeding with American bison in a separate breeding project in Munich, in 1934.

Heck gained the support of then Reichsjägermeister Hermann Göring, who hoped for huntable big game.[46] Heck promised his powerful supporter in writing: "Since surplus bulls will soon be set, the hunting of the Wisent will be possible again in the foreseeable future". Göring himself took over the patronage of the German Professional Association of Wisent Breeders and Hegers, founded at Heck's suggestion. Kurt Priemel, who had since resigned as president of the International Society for the Preservation of the Wisent, warned in vain against "manification". Heck answered by announcing that Göring would take action against Priemel if he continued to oppose his crossing plans. Priemel was then banned from publishing in relation to bison breeding, and the regular bookkeeper of the International Society, Erna Mohr, was forced to hand over the official register in 1937. Thus, the older society was effectively incorporated into the newly created Professional Association. After the Second World War, therefore, only the pure-blooded bison in the game park Springe near Hanover were recognised as part of the international herd book.[47][48]

The first two bison were released into the wild in the Białowieża Forest in 1929.[49] By 1964 more than 100 existed.[50] Over the following decades, thanks to Polish and international efforts, the Białowieża Forest regained its position as the location with the world's largest population of European bison, including those in the wild.[20] In 2005-2007, a wild bison nicknamed Pubal became renowned in southeast Poland due to his friendly interactions with humans and unwillingness to reintegrate into the wild.[51] As of 2014 there were 1,434 wisents in Poland, out of which 1,212 were in free-range herds and 522 belonged to the wild population in the Białowieża Forest. Compared to 2013, the total population in 2014 increased by 4.1%, while the free-ranging population increased by 6.5%.[52] Bison from Poland have also been transported beyond the country's borders to boost the local populations of other countries, among them Bulgaria, Spain, Romania, Czechia and others.[53] Poland has been described as the world's breeding centre of the European bison,[20] where the bison population doubled between 1995 and 2017, reaching 2,269 by the end of 2019[54] – the total population has been increasing by around 15% to 18% yearly.[6] In July 2022 a small population was released into woodland by Canterbury in Kent to trial their reintroduction into the UK.[55]

A 2003 study of mitochondrial DNA indicated four distinct maternal lineages in the tribe Bovini:

Y chromosome analysis associated wisent and American bison.[56] An earlier study, using amplified fragment-length polymorphism fingerprinting, showed a close association of wisent and American bison and probably with yak. It noted the interbreeding of Bovini species made determining relationships problematic.[57]

European bison can crossbreed with American bison. This hybrid is known in Poland as a żubrobizon. The products of a German interbreeding programme were destroyed after the Second World War. This programme was related to the impulse which created the Heck cattle. The cross-bred individuals created at other zoos were eliminated from breed books by the 1950s. A Russian back-breeding programme resulted in a wild herd of hybrid animals, which presently lives in the Caucasian Biosphere Reserve (550 animals in 1999).

Wisent-cattle hybrids also occur, similar to the North American beefalo. Cattle and European bison hybridise fairly readily. First-generation males are infertile. In 1847, a herd of wisent-cattle hybrids named żubroń (/ˈʒuːbrɒnj/) was created by Leopold Walicki. The animals were intended to become durable and cheap alternatives to cattle. The experiment was continued by researchers from the Polish Academy of Sciences until the late 1980s. Although the program resulted in a quite successful animal that was both hardy and could be bred in marginal grazing lands, it was eventually discontinued. Currently, the only surviving żubroń herd consists of just a few animals in Białowieża Forest, Poland and Belarus.

In 2016, the first whole genome sequencing data from two European bison bulls from the Białowieża Forest revealed that the bison and bovine species diverged from about 1.7 to 0.85 Mya, through a speciation process involving limited gene flow.[58] These data further support the occurrence of more recent secondary contacts, posterior to the divergence between Bos primigenius primigenius and B. p. namadicus (ca. 150,000 years ago), between the wisent and (European) taurine cattle lineages. An independent study of mitochondrial DNA and autosomal markers confirmed these secondary contacts (with an estimate of up to 10% of bovine ancestry in the modern wisent genome) leading the authors to go further in their conclusions by proposing the wisent to be a hybrid between steppe bison and aurochs with a hybridisation event originating before 120,000 years ago.[21] However, other studies considered the 10% estimate for aurochs gene flow a gross overstimate and based on flawed data, and not supported by the data from the full nuclear genome of the wisent.[32]

Some of the authors however support the hypothesis that similarity of wisent and cattle (Bos) mitochondrial genomes is result of incomplete lineage sorting during divergence of Bos and Bison from their common ancestors rather than further post-speciation gene flow (ancient hybridisation between Bos and Bison). But they agree that limited gene flow from Bos primigenius taurus could account for the affiliation between wisent and cattle nuclear genomes (in contrast to mitochondrial ones).[59]

Alternatively, genome sequencing completed on remains attributed to the Pleistocene woodland bison (B. schoetensacki), and published in 2017, posited that genetic similarities between the Pleistocene woodland bison and the wisent suggest that B. schoetensaki was the ancestor of the European wisent.[29][60] However, other studies have disputed the attribution of the remains to this species, otherwise known from remains hundreds of thousands of years older, instead referring them to an unnamed lineage of bison closely related to B. bonasius.[32] A 2018 study proposed that the lineage leading to the wisent and to the lineage ancestral to both the American bison and Bison priscus had split over 1 million years ago, with the mitochondrial DNA discrepancy being the result of incomplete lineage sorting. The authors also proposed that during the late Middle Pleistocene there had been interbreeding between the ancestor of the wisent and the common ancestor of Bison priscus and the American bison.[32]

The European bison is a herd animal, which lives in both mixed and solely male groups. Mixed groups consist of adult females, calves, young aged 2–3 years, and young adult bulls. The average herd size is dependent on environmental factors, though on average, they number eight to 13 animals per herd. Herds consisting solely of bulls are smaller than mixed ones, containing two individuals on average. European bison herds are not family units. Different herds frequently interact, combine, and quickly split after exchanging individuals.[39]

Bison social structure has been described by specialists as a matriarchy, as it is the cows of the herd that lead it, and decide where the entire group moves to graze.[61] Although larger and heavier than the females, the oldest and most powerful male bulls are usually satellites that hang around the edges of the herd to protect the group.[62] Bulls begin to serve a more active role in the herd when a danger to the group's safety appears, as well as during the mating season – when they compete with each other.[63]

Territory held by bulls is correlated by age, with young bulls aged between five and six tending to form larger home ranges than older males. The European bison does not defend territory, and herd ranges tend to greatly overlap. Core areas of territory are usually sited near meadows and water sources.[39]

The rutting season occurs from August through to October. Bulls aged 4–6 years, though sexually mature, are prevented from mating by older bulls. Cows usually have a gestation period of 264 days, and typically give birth to one calf at a time.[39]

On average, male calves weigh 27.6 kg (60.8 lb) at birth, and females 24.4 kg (53.8 lb). Body size in males increases proportionately to the age of 6 years. While females have a higher increase in body mass in their first year, their growth rate is comparatively slower than that of males by the age of 3–5. Bulls reach sexual maturity at the age of two, while cows do so in their third year.[39]

European bison have lived as long as 30 years in captivity,[64] but in the wild their lifespans are shorter. The lifespan of a bison in the wild is usually between 18 and 24 years, though females live longer than males.[65] Productive breeding years are between four and 20 years of age in females, and only between six and 12 years of age in males.

European bison feed predominantly on grasses, although they also browse on shoots and leaves; in summer, an adult male can consume 32 kg of food in a day.[66] European bison in the Białowieża Forest in Poland have traditionally been fed hay in the winter for centuries, and large herds may gather around this diet supplement.[66] European bison need to drink every day, and in winter can be seen breaking ice with their heavy hooves.[67]

Although superficially similar, a number of physical and behavioural differences are seen between the European bison and the American bison. The bison has 14 pairs of ribs, while the American bison has 15.[68]

Adult European bison are (on average) taller than American bison, and have longer legs.[69] European bison tend to browse more, and graze less than their American relatives, due to their necks being set differently. Compared to the American bison, the nose of the European bison is set further forward than the forehead when the neck is in a neutral position.

The body of the wisent is less hairy, though its tail is hairier than that of the American species. The horns of the European bison point forward through the plane of their faces, making them more adept at fighting through the interlocking of horns in the same manner as domestic cattle, unlike the American bison, which favours charging.[70] European bison are less tameable than the American ones, and breed with domestic cattle less readily.[71]

The European bison is less shaggy, with a more lanky body shape.[72]

In terms of behavioural capability, European bison runs slower and with less stamina yet jumps higher and longer than American bisons, showing signs of more developed adaptations into mountainous habitats.[13]

The protection of the European bison has a long history; between the 15th and 18th centuries, those in the forest of Białowieża were protected and their diet supplemented.[73] Efforts to restore this species to the wild began in 1929, with the establishment of the Bison Restitution Centre at Białowieża, Poland.[74][75] Subsequently, in 1948, the Bison Breeding Centre was established within the Prioksko-Terrasny Biosphere Reserve.

The modern herds are managed as two separate lines – one consisting of only Bison bonasus bonasus (all descended from only seven animals) and one consisting of all 12 ancestors, including the one B. b. caucasicus bull.[76] The latter is generally not considered a separate subspecies because they contain DNA from both B. b. bonasus and B. b. caucasicius, although some scientists classify them as a new subspecies, B. b. montanus.[77] Only a limited amount of inbreeding depression from the population bottleneck has been found, having a small effect on skeletal growth in cows and a small rise in calf mortality. Genetic variability continues to shrink. From five initial bulls, all current European bison bulls have one of only two remaining Y chromosomes.

Beginning in 1951, European bison have been reintroduced into the wild, including some areas where they were never found wild.[78][79] Free-ranging herds are currently found in Poland, Lithuania, Belarus, Ukraine, Bulgaria, Romania, Russia, Slovakia,[80] Latvia, Switzerland, Kyrgyzstan, Germany,[81][82] and in forest preserves in the Western Caucasus. The Białowieża Primeval Forest, an ancient woodland that straddles the border between Poland and Belarus, continues to have the largest free-living European bison population in the world with around 1000 wild bison counted in 2014.[83] Herds have also been introduced in Moldova (2005),[84] Spain (2010),[85] Denmark (2012),[86] and the Czech Republic (2014).[87]

The Wilder Blean project, headed up by the Wildwood Trust and Kent Wildlife Trust, introduced European bison to the UK for the first time in 6000 years (although there was an unsuccessful attempt in Scotland in 2011,[88] and the European bison is not confirmed to be native to England while the British Isles once used to be inhabited by now-extinct Steppe bison and Pleistocene woodland bison).[29][78][89] The herd of 3 females, with plans to also release a male in the following months, was set free in July 2022 within a 2,500-acre conservation area in West Blean and Thornden Woods, near Canterbury.[90][91][92] Unknown to the rangers, one of the females was pregnant and gave birth to a calf in October 2022, marking the first wild bison born in the UK for the first time in millennia. [93]

As below-mentioned, there are established herds in Spain and Italy, however European bison has not been recorded naturally from the Iberian and Italian Peninsulas,[24] while these regions were once inhabited by Pleistocene woodland bison and Steppe bison.[29][94][95][96]

The total worldwide population recorded in 2019 was around 7,500 – about half of this number being in Poland and Belarus, with over 25% of the global population located in Poland alone.[6] For 2016, the number was 6,573 (including 4,472 free-ranging) and has been increasing.[52] Some local populations are estimated as:

The largest European bison herds — of both captive and wild populations — are still located in Poland and Belarus,[6] the majority of which can be found in the Białowieża Forest including the most numerous population of free-living European bison in the world with most of the animals living on the Polish side of the border.[83] Poland remains the world's breeding centre for the wisent.[20] In the years 1945 to 2014, from the Białowieża National Park alone, 553 specimens were sent to most captive populations of the bison in Europe as well as all breeding sanctuaries for the species in Poland.[83]

Since 1983, a small reintroduced population lives in the Altai Mountains. This population suffers from inbreeding depression and needs the introduction of unrelated animals for "blood refreshment". In the long term, authorities hope to establish a population of about 1,000 animals in the area. One of the northernmost current populations of the European bison lives in Vologodskaya Oblast in the Northern Dvina valley at about 60°N. It survives without supplementary winter feeding. Another Russian population lives in the forests around the Desna River on the border between Russia and Ukraine.[40] The north-easternmost population lives in Pleistocene Park south of Chersky in Siberia, a project to recreate the steppe ecosystem which began to be altered 10,000 years ago. Five wisents were introduced on 24 April 2011. The wisents were brought to the park from the Prioksko-Terrasny Nature Reserve near Moscow. Winter temperatures often drop below −50 °C. Four of the five bison have subsequently died due to problems acclimatizing to the low winter temperature.

Plans are being made to reintroduce two herds in Germany[134] and in the Netherlands in Oostvaardersplassen Nature Reserve[135] in Flevoland as well as the Veluwe. In 2007, a bison pilot project in a fenced area was begun in Zuid-Kennemerland National Park in the Netherlands.[136] Because of their limited genetic pool, they are considered highly vulnerable to illnesses such as foot-and-mouth disease. In March 2016, a herd was released in the Maashorst Nature Reserve in North Brabant. Zoos in 30 countries also have quite a few bison involved in captive-breeding programs.

Representations of the European bison from different ages, across millennia of human society's existence, can be found throughout Eurasia in the form of drawings and rock carvings; one of the oldest and most famous instances of the latter can be found in the Cave of Altamira, present-day Spain, where cave art featuring the wisent from the Upper Paleolithic was discovered.[137] The bison has also been represented in a wide range of art in human history, such as sculptures, paintings, photographs, glass art, and more.[138] Sculptures of the wisent constructed in the 19th and 20th centuries continue to stand in a number of European cities; arguably the most notable of these are the zubr statue in Spała from 1862 designed by Mihály Zichy and the two bison sculptures in Kiel sculpted by August Gaul in 1910–1913. However, a number of other monuments to the animal also exist, such as those in Hajnówka and Pszczyna or at the Kyiv Zoo entrance.[138][137] Mikołaj Hussowczyk, a poet writing in Latin about the Grand Duchy of Lithuania during the early 16th century, described the bison in a historically significant fictional work from 1523.[139]

The European bison is considered one of the national animals of Poland and Belarus.[5] Due to this and the fact that half of the worldwide European bison population can be found spread across these two countries,[6] the wisent is still featured prominently in the heraldry of these neighbouring states (especially in the overlapping region of Eastern Poland and Western Belarus).[138] Examples in Poland include the coats of arms of: the counties of Hajnówka and Zambrów, the towns Sokółka and Żywiec, the villages Białowieża and Narewka, as well as the coats of arms of the Pomian and Wieniawa families. Examples in Belarus include the Grodno and Brest voblasts, the town of Svislach, and others. The European bison can also be found on the coats of arms of places in neighbouring countries: Perloja in southern Lithuania, Lypovets in west-central Ukraine, and Zubří in east Czechia – as well as further outside the region, such as Kortezubi in the Basque Country, and Jabel in Germany.

A flavoured vodka called Żubrówka ([ʐuˈbrufka]), originating as a recipe of the szlachta of the Kingdom of Poland in the 14th century, has since 1928 been industrially produced as a brand in Poland.[140] In the decades that followed, it became known as the "world's best known Polish vodka"[141] and sparked the creation of a number of copy brands inspired by the original in Belarus, Russia, Germany, as well as other brands in Poland.[142] The original Polish brand is known for placing a decorative blade of bison grass from the Białowieża Forest in each bottle of their product; both the plant's name in Polish and the vodka are named after żubr, the Polish name for the European bison.[140] The bison also appears commercially as a symbol of a number of other Polish brands, such as the popular beer brand Żubr and on the logo of Poland's second largest bank, Bank Pekao S.A.[138]

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires |journal= (help) {{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) {{cite news}}: |first1= has generic name (help) {{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) This article incorporates text from the ARKive fact-file "European bison" under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License and the GFDL.

The European bison (PL: bison) (Bison bonasus) or the European wood bison, also known as the wisent (/ˈviːzənt/ or /ˈwiːzənt/), the zubr (/zuːbər/), or sometimes colloquially as the European buffalo, is a European species of bison. It is one of two extant species of bison, alongside the American bison. The European bison is the heaviest wild land animal in Europe, and individuals in the past may have been even larger than their modern-day descendants. During late antiquity and the Middle Ages, bison became extinct in much of Europe and Asia, surviving into the 20th century only in northern-central Europe and the northern Caucasus Mountains. During the early years of the 20th century, bison were hunted to extinction in the wild.

The species — now numbering several thousand and returned to the wild by captive breeding programmes — is no longer in immediate danger of extinction, but remains absent from most of its historical range. It is not to be confused with the aurochs (Bos primigenius), the extinct ancestor of domestic cattle, with which it once co-existed.

Besides humans, bison have few predators. In the 19th century, there were scattered reports of wolves, lions, tigers, and bears hunting bison. In the past, especially during the Middle Ages, humans commonly killed bison for their hide and meat. They used their horns to make drinking horns.

European bison were hunted to extinction in the wild in the early 20th century, with the last wild animals of the B. b. bonasus subspecies being shot in the Białowieża Forest (on today's Belarus–Poland border) in 1921. The last of the Caucasian wisent subspecies (B. b. caucasicus) was shot in the northwestern Caucasus in 1927. The Carpathian wisent (B. b. hungarorum) had been hunted to extinction by 1852.

The Białowieża or lowland European bison was kept alive in captivity, and has since been reintroduced into several countries in Europe. In 1996, the International Union for Conservation of Nature classified the European bison as an endangered species, no longer extinct in the wild. Its status has improved since then, changing to vulnerable and later to near-threatened.

European bison were first scientifically described by Carl Linnaeus in 1758. Some later descriptions treat the European bison as conspecific with the American bison. Three subspecies of the European bison existed in the recent past, but only one, the nominate subspecies (B. b. bonasus), survives today. The ancestry and relationships of the wisent to fossil bison species remain controversial and disputed.

The European bison is one of the national animals of Poland and Belarus.