pms

nòm ant ël fil

The Platystomatidae (signal flies) are a distinctive family of flies (Diptera) in the superfamily Tephritoidea.

Signal flies are worldwide in distribution, found in all the biogeographic realms, but predominate in the tropics. It is one of the larger families of acalyptrate Diptera with around 1200 species in 127 genera.

Adults are found on tree trunks and foliage and are attracted to flowers, decaying fruit, excrement, sweat, and decomposing snails.[2][3] Larvae are found on fresh and decaying vegetation, carrion, human corpses, and root nodules, particularly in the genus Rivellia, which has economic implications for legume crops.[4] Larvae from the remaining genera are either phytophagous (eating plant material) or saprophagous (eating decomposing organic matter). Some are predatory on other insects and others have been found in human lesions, while others are of minor agricultural significance.

For terms see Morphology of Diptera

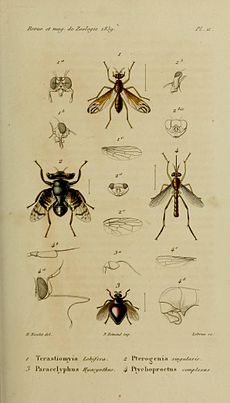

Signal flies are very variable in external appearance, ranging from small (2.5 mm), slender species to large (20 mm), robust individuals, often with body colours having a distinctive metallic lustre and with face and wings usually patterned with dark spots or bands. The head is large. Frontal bristles on head are absent. Two orbital bristles are on the head. The frontal stripe is pubescent and the arista is more or less long and pubescent. The antennal grooves are deep and divided by a median keel. Radial vein 4+5 bears bristles. The costa is without interruptions and the anal cell is elongated, bordered on outer side by an arcuate or straight vein. The abdomen of male has five visible segments and the female has six.

Many bizarre forms of morphology and behaviour occur in this family. Heads and legs (fore legs especially) may be oddly shaped, extended in various ways or with adornments, all of which serve to supplement agonistic behaviour. Such behaviour underlies social and sexual interaction between individuals of the same species of signal flies, first researched in Australian species of the genera Euprosopia (image) and Pogonortalis.[5]

In males of Pogonortalis, the length and degree of development of hairs (setae) on the lower facial area, together with widening of the head, facilitates territorial dominance[6] by head-butting and rearing-up behaviours. Head-butting is taken to the extreme in the Australasian genus Achias,[7][8] in which species have the fronto-orbital plates expanded laterally to produce eyestalks.

Development of body structures is prevalent in the Afrotropical and Oriental subfamily Plastotephritinae,[9] including 9 different types of modification in 16 genera.[10]

Some species have prominent eyestalks also found in the family Diopsidae. In the Diopsidae, eyestalks develop through lateral development of the frontal plate, with the result that the antennae are situated on the stalk near the compound eye. The process of development in signal flies is different in that the fronto-orbital plates expanded laterally to produce eyestalks and consequently the antennae remain in a central position. This is an example of convergent evolution. The development of eyestalks reaches its extreme in the platystomatid species Achias rothschildi Austen, 1910 from New Guinea, pictured here in which males have an eye-span up to 55 mm.[11]

Families of acalyptrate flies exhibiting morphological development associated with agonistic behaviour include: Clusiidae, Diopsidae, Drosophilidae, Platystomatidae, Tephritidae, and Ulidiidae.

See also [1]

The largest concentration of Platystomatidae undoubtedly occurs in the Australasian region,[12] followed closely by the Afrotropical region. The number of genera and species in the Oriental, European,[13] Nearctic and Neotropical faunas are much more restricted and are summarised in the Regional Catalogues.

Some genera are widely distributed over more than one region. For example, Plagiostenopterina Hendel, 1912,[14] is widely distributed in the Old World tropics (Australasian, Oriental and Afrotropical regions) and Rivellia Robineau-Desvoidy, 1830[15] is almost cosmopolitan,[12] although numbers of species in Europe are very restricted in number. Taxonomic revisions of such genera need to examine the wider implications of these broad distributions. Other genera are known from just a single location. Bama McAlpine, 2001, for example, is known only from New Guinea.[12]

As is the case with the taxonomy many flies, the first described species of Platystomatidae were placed in the large family Muscidae, because in the 19th century, the Muscidae formed a portmanteau group for the higher Diptera. It was only after many species were accumulated into larger collections and numerous names proposed, that taxonomists began to realise that the Diptera consisted of several distinct families.

The oldest family-group name for the Platystomatidae is in fact Achiasidae Fleming, 1821,[16] based on the genus Achias Fabricius, 1805.[17] There has, however, been an overwhelming predominance of the usage of names based on the genus Platystoma Meigen, 1803.[18] After petition by Steyskal & McAlpine (1974),[19] the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (1979) ruled under plenary power that family-group names based on Achias should be suppressed, giving those based on Platystoma precedence.[20]

Initially, subfamilies within the Muscidae were recognised; the early Platystomatidae belonging to the Ortalides, but toward the end of the 19th century, many of these subfamilies were raised to family status, at which point the Ortalides became the Ortalidae. The name Otitidae became a replacement name for Ortalides, until Hendel's significant contribution and re-organisation of the genera of the World [21] firmly placed the Platystomatidae as a subfamily of Muscaridae, divided into several tribes. Furthermore, he recognised the broad divisions Acalyptrae and Calyptrae, placing Platystomatinae correctly in the former. Enderlein, who proposed more new plastotephritine (subfamily) names than Hendel, still preferred Ortalidae to Muscaridae, but adopted the Platystomatinae subfamily status that Hendel had proposed.[22][23]

The Platystomatidae (signal flies) are a distinctive family of flies (Diptera) in the superfamily Tephritoidea.

Signal flies are worldwide in distribution, found in all the biogeographic realms, but predominate in the tropics. It is one of the larger families of acalyptrate Diptera with around 1200 species in 127 genera.

Platystomatidae es una familia de moscas (Diptera) de la superfamilia Tephritoidea. Son de distribución mundial, más predominantes en regiones tropicales. Es una de las familias más numerosas de Acalyptratae con alrededor de 1200 especies en 127 géneros

Los adultos se encuentran en el follaje o troncos de árboles, también son atraídos a las flores, excremento, sudor y material en descomposición.[1][2] Las larvas se encuentran en materia vegetal fresca o en descomposición, cadáveres y nódulos radicales, especialmente las del género Rivellia, lo cual tiene importancia para el cultivo de legumbres.[3] Las larvas de otros géneros son fitófagas o saprófitas. Algunas son depredadoras de otros insectos y algunas se las encuentra en lesiones humanas. Algunas especies son plagas importantes de la agricultura.

Son de apariencia variable, desde muy pequeñas (2,5mm) y delgadas a grandes (20mm), robustas, a menudo con cuerpos coloridos con detalles metálicos y rostros y alas con diseños de bandas y manchas oscuras. La cabeza es grande, carece de setas frontales. Hay dos setas orbitales. Las bandas frontales son vellosas y las aristtas son más o menos largas y vellosas. Los surcos antenales son profundos y divididos por una quilla media.

Las venas radiales 4 y 5 de las alas tienen setas. La costa no tiene interrupciones y la célula anal es alargada, bordeada en su lado externo por una vena recta o arqueada. El abdomen del macho tiene cinco segmentos visibles, el de la hembra tiene seis.

La mayor concenntración de Platystomatidae se encuentra en la región de Australasia,[4] seguida por la región Afrotropical. El número de géneros y especies en las regiones oriental, europea,[5] neártica y neotrópica son mucho más reducidos.

Algunos géneros son abundantes en más de una región, por ejemplo, Plagiostenopterina Hendel, 1912,[6] se encuentra en los trópicos del Viejo Mundo y Rivellia Robineau-Desvoidy, 1830[7] es casi cosmopolita,[4][4]

Platystomatidae es una familia de moscas (Diptera) de la superfamilia Tephritoidea. Son de distribución mundial, más predominantes en regiones tropicales. Es una de las familias más numerosas de Acalyptratae con alrededor de 1200 especies en 127 géneros

Les Platystomatidae sont une famille d'insectes diptères brachycères.

Selon BioLib (25 juillet 2021)[1] :

Selon Catalogue of Life (1 mars 2013)[2] :

Selon Fauna Europaea (3 juillet 2013)[4]

Les Platystomatidae sont une famille d'insectes diptères brachycères.

De Platystomatidae zijn een familie uit de orde van de tweevleugeligen (Diptera), onderorde vliegen (Brachycera). Wereldwijd omvat deze familie zo'n 128 genera en 1164 soorten.

Krusfluer (Platystomatidae) også omtalt som tiriltungefluer eller signalfluer, er en familie av små til middelsstore fluer der de fleste artene lever i varme strøk, bare to arter finnes i Norge. De har mer eller mindre fargemønstrede vinger som brukes som signalflagg under kurtisen. Noen tropiske arter har sterkt utvidet hode – «øyne på stilk».

Små til middelsstore fluer (4 - 20 mm). Brystet (thorax) er vanligvis bredt, med lange børster, men bare langs kanten. Bakkroppen er kort og tykk. Beina er korte og kraftige, uten noen slående særtrekk.

Vingene er mer eller mindre flekkete eller med fargede bånd. Fremkantåren (costa) er brutt på ett sted. Den fremste lange åren (R1) har tydelige hår på oversiden.

Hodet er stort, kortere enn bredt, ofte noe flattrykt. Hos noen tropiske arter er hodet hos hannene sterkt utvidet sidelengs slik at fasettøynene står på stilk. Fasettøynene er store, men møtes ikke i pannen, og det sitter en eller to børster ved innerkanten av hvert fasettøye nær toppen, men ingen i de nedre fire femdelene av øyet. Pannen er ganske bred uten børster, bare med ganske korte hår. De har vanligvis tre punktøyne (ocelli) i pannen, men disse kan mangle. Antennen er av vanlig fluetype, tre-leddet, det tredje leddet oftest tilspisset kjegleformet. En antennebørste (arista) sitter festet på oversiden av det tredje leddet nær roten. Munndelene er av vanlig fluetype, ofte kraftige.

Larvene er av typisk fluetype (det er bare noen få arter der larvene er beskrevet). Noen larver er i stand til å hoppe.

Man kan finne krusfluene i mange forskjellige miljøer, særlig i skog. De voksne fluene kommer sjelden til blomster, men mange arter blir tiltrukket til møkk, kadaver og gjærende fruktsaft. Noen arter kan drikke svette fra mennesker.

Hannene kjemper om hunnene, og de fargede vingene brukes til signalisering overfor individer av samme eller motsatt kjønn. Hos de artene der hodet er utvidet brukes hodebredden til å avgjøre konflikter mellom hannene – hannen med det bredeste hodet er størst og vil vanligvis vinne en konflikt uten kamp.

Larvene kan leve i mange ulike habitater, de fleste kanskje i råtnende plantemateriale. Larver av noen Rivellia-arter har blitt funnet på de nitrogenfikserende rotknollene hos erteplanter. En art har larver som spiser gresshoppe-egg.

Krusfluer (Platystomatidae) også omtalt som tiriltungefluer eller signalfluer, er en familie av små til middelsstore fluer der de fleste artene lever i varme strøk, bare to arter finnes i Norge. De har mer eller mindre fargemønstrede vinger som brukes som signalflagg under kurtisen. Noen tropiske arter har sterkt utvidet hode – «øyne på stilk».