pms

nòm ant ël fil

Die Familie Polyomaviridae umfasst unbehüllte DNA-Viren, die bei verschiedenen Wirbeltieren (Säugetiere, Nagetiere und Vögel) und beim Menschen zu persistierenden Infektionen führen. Diese und die nahestehende Familie Papillomaviridae entstanden durch Aufspaltung der ehemaligen Familie Papovaviridae wurden vom International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) im März 2020 als Papovaviricetes in den Rang einer Klasse erhoben, um die beiden Familien der Papovaviren zusammenzufassen.[1] Die ursprünglich einzige Gattung Polyomavirus wurde schon vorher ebenso aufgeteilt in vier Gattungen Alphapolyomavirus bis Deltapolyomavirus (s. u.). Der Name der Familie setzt sich aus dem griechischen πολύς (poly: viel, mehrere) und dem Suffix -oma aus der Benennung für Tumoren ab, da das erste identifizierte Virus der Familie, das Murine Polyomavirus, bei neugeborenen Mäusen zu verschiedenen Tumoren führt.

2013 wurden Hybride beschrieben zwischen Papillomaviren und Polyomaviren.[2]

Die Virionen (Viruspartikel) der Polyomaviren bestehen aus einem nackten, etwa 40 bis 45 nm im Durchmesser großen Kapsid, das aus 72 Kapsomeren zusammengesetzt ist. Die Kapsomere sind in einer ikosaedrischen Symmetrie angeordnet (T=7). Die einzelnen Kapsomere werden an der Basis aus fünf Molekülen des Kapsidproteins VP1 gebildet (Pentamer), die jedoch zueinander nicht gleichförmig, sondern verdreht (windschief) angeordnet sind. Man spricht daher auch von einer verdrehten, ikosaedrischen Symmetrie (T=7d). An der Innenseite des Kapsids stabilisieren die Kapsidproteine VP2 und VP3 das VP1-Gerüst; sie interagieren auch mit der dsDNA im Inneren des Kapsids. Häufig werden abweichende Viruspartikel beobachtet, darunter leere normal strukturierte Kapside, sehr kleine, leere Kapside (Mikrokapside) und unregelmäßige röhrenförmige Strukturen, die aus den Kapsidproteinen in unterschiedlicher Zusammensetzung gebildet werden. Das VP1 Kapsidprotein kann sich ohne weitere Virusproteine spontan zu Virus-ähnlichen Partikeln zusammenlagern, die jedoch keine Nukleinsäure verpacken können. Im echten Virion macht das VP1 rund 70 % des gesamten Proteingehaltes aus.

Im Inneren der Kapside befindet sich der kovalent geschlossene DNA-Ring des Virusgenoms. Dieser ist wie bei den Papillomaviridae mehrfach verdrillt („supercoiled“) und bildet zusammen mit zellulären Histonen einen Nukleoproteinkomplex, der den eukaryotischen Nukleosomen strukturell sehr ähnelt. Von den fünf bekannten Histonen findet man die Histone H2a, H2b, H3 und H4.

Die Kapside sind sehr umweltstabil und können mit Diethylether, 2-Propanol oder Detergenzien (Seife) nicht inaktiviert werden. Sie sind hitzestabil bis 50 °C für 1 Stunde; bei gleichzeitiger Gegenwart von Magnesiumchlorid in 1 M Konzentration, sind die Kapside instabil, was ähnlich wie bei den Papillomviren auf die Abhängigkeit der Kapsidstruktur von zweiwertigen Kationen hindeutet.

Das Genom der Polyomaviren besteht aus einem einzelnen Molekül eines doppelsträngigen, kovalent geschlossenen DNA-Rings. Von einer nichtcodierenden, regulatorischen Region ausgehend sind die Offenen Leserahmen (ORFs) für die 5 bis 9 verschiedenen Virusproteine so angeordnet, dass die ORFs für die frühen Transkripte in einer Leserichtung laufen, die der späten Transkripte in die entgegengesetzte Richtung. Zu den frühen Transkripten gehören das große und eventuell auch kleine T-Antigen sowie andere regulatorische Proteine; die späten Transkripte codieren für die drei Strukturproteine VP1-3. Die Leserahmen überlappen sich mit teilweise verschiedenen Leserastern, so dass die Polyomaviren mit einer Genomgröße von etwa 4,7 bis 5,5 kBp für eine relativ hohe Zahl an Proteinen codieren. Wie die Papillomviren besitzen die Polyomaviren keine eigene DNA-Polymerase zur Vermehrung der viralen DNA, sie sind ebenfalls auf zelleigene Polymerasen angewiesen. Die frühen Virusproteine binden an die Enhancer und Promotoren für ihre eigenen Leserahmen in der regulatorischen Region. Dadurch wird im Laufe der Virusvermehrung die Produktion dieser Proteine zugunsten der späten Proteine unterdrückt. Die Untersuchung dieses Mechanismus beim SV-40 führte zur Entdeckung dieser regulatorischen Sequenzen bei Eukaryoten und zur Entwicklung des Enhancer-Konzeptes in der Molekularbiologie.

Aviäre Polyomaviren lösen beispielsweise die Französische Mauser aus. Das BK-Virus (BKV, BK-Polyomavirus oder BKPyV) kann beim Menschen bei immunsuppressiver Behandlung nach Nierentransplantation zum Verlust des Transplantates führen. Das BK-Virus kann außerdem zur Infektion der Atemwege oder Zystitis bei Kindern führen, es kann eine hämorrhagische Zystitis bei Knochenmarkstransplantierten, eine Ureterstenose bei Nierentransplantierten und eine Meningoencephalitis bei AIDS-Patienten hervorrufen.

Die zu dieser Gattung gehörenden BK- und JC-Viren, die auch als Humanes Polyomavirus 1 und 2 (früher Polyomavirus hominis Typ 1 und 2) bezeichnet werden, persistieren im Nierengewebe; in der Normalbevölkerung können Antikörper gegen BK-Virus (BKV) zu 100 % und gegen JC-Virus (JCV) zu etwa 80 % nachgewiesen werden.

Die Tatsache, dass bei nicht erheblich vorgeschädigten Menschen und bei nicht erfolgter Doppelinfektion oder Sekundärinfektion eine Infektion mit diesen Viren nur extrem selten einen tödlichen Verlauf nimmt, zeigt zum Einen, dass diese krankheitsauslösenden Viren sehr stark an den Menschen als ihren Reservoirwirt angepasst sind. Die Schädigung seines Reservoirwirts ist für ein Virus kein vorteilhafter Effekt, da er zur eigenen Vermehrung auf diesen angewiesen ist. Die dennoch von diesem Virus beim Reservoirwirt ausgelösten Erkrankungen sind letztlich nur Nebeneffekte der Infektion. Zum Zweiten wird dadurch auch deutlich, dass sich der Mensch ebenfalls im Verlaufe vieler Generationen an dieses Virus anpassen konnte. Es besteht im Moment eine BK-Virus Durchseuchung der Bevölkerung von 80-90 %. Das JC-Virus führt bei zellulär Immunsupprimierten (AIDS St. C3) zur progressiv multifokalen Leukoenzephalopathie (PML). Die PML verläuft fast immer tödlich.

Das Simiane Virus 40 oder SV40 ist potenzieller Auslöser verschiedener Tumorerkrankungen. Teile der SV40-DNA finden in der Molekularbiologie Anwendung als besonders starker Promotor beziehungsweise Enhancer.

Die frühere Gattung Polyomavirus wurde in vier Teile aufgespaltet, denen die Namen der griechischen Buchstaben Alpha bis Delta vorangestellt werden (ICTV Stand November 2018):[3][4][5]

Die Familie Polyomaviridae umfasst unbehüllte DNA-Viren, die bei verschiedenen Wirbeltieren (Säugetiere, Nagetiere und Vögel) und beim Menschen zu persistierenden Infektionen führen. Diese und die nahestehende Familie Papillomaviridae entstanden durch Aufspaltung der ehemaligen Familie Papovaviridae wurden vom International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) im März 2020 als Papovaviricetes in den Rang einer Klasse erhoben, um die beiden Familien der Papovaviren zusammenzufassen. Die ursprünglich einzige Gattung Polyomavirus wurde schon vorher ebenso aufgeteilt in vier Gattungen Alphapolyomavirus bis Deltapolyomavirus (). Der Name der Familie setzt sich aus dem griechischen πολύς (poly: viel, mehrere) und dem Suffix -oma aus der Benennung für Tumoren ab, da das erste identifizierte Virus der Familie, das Murine Polyomavirus, bei neugeborenen Mäusen zu verschiedenen Tumoren führt.

2013 wurden Hybride beschrieben zwischen Papillomaviren und Polyomaviren.

Polyomaviridae is a family of viruses whose natural hosts are primarily mammals and birds.[1][2] As of 2020, there are six recognized genera and 117 species, five of which are unassigned to a genus.[3] 14 species are known to infect humans, while others, such as Simian Virus 40, have been identified in humans to a lesser extent.[4][5] Most of these viruses are very common and typically asymptomatic in most human populations studied.[6][7] BK virus is associated with nephropathy in renal transplant and non-renal solid organ transplant patients,[8][9] JC virus with progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy,[10] and Merkel cell virus with Merkel cell cancer.[11]

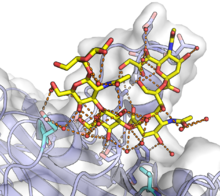

Polyomaviruses are non-enveloped double-stranded DNA viruses with circular genomes of around 5000 base pairs. The genome is packaged in a viral capsid of about 40-50 nanometers in diameter, which is icosahedral in shape (T=7 symmetry).[2][12] The capsid is composed of 72 pentameric capsomeres of a protein called VP1, which is capable of self-assembly into a closed icosahedron;[13] each pentamer of VP1 is associated with one molecule of one of the other two capsid proteins, VP2 or VP3.[5]

The genome of a typical polyomavirus codes for between 5 and 9 proteins, divided into two transcriptional regions called the early and late regions due to the time during infection in which they are transcribed. Each region is transcribed by the host cell's RNA polymerase II as a single pre-messenger RNA containing multiple genes. The early region usually codes for two proteins, the small and large tumor antigens, produced by alternative splicing. The late region contains the three capsid structural proteins VP1, VP2, and VP3, produced by alternative translational start sites. Additional genes and other variations on this theme are present in some viruses: for example, rodent polyomaviruses have a third protein called middle tumor antigen in the early region, which is extremely efficient at inducing cellular transformation; SV40 has an additional capsid protein VP4; some examples have an additional regulatory protein called agnoprotein expressed from the late region. The genome also contains a non-coding control or regulatory region containing the early and late regions' promoters, transcriptional start sites, and the origin of replication.[2][12][5][15]

The polyomavirus life cycle begins with entry into a host cell. Cellular receptors for polyomaviruses are sialic acid residues of glycans, commonly gangliosides. The attachment of polyomaviruses to host cells is mediated by the binding of VP1 to sialylated glycans on the cell surface.[2][12][15][16] In some particular viruses, additional cell-surface interactions occur; for example, the JC virus is believed to require interaction with the 5HT2A receptor and the Merkel cell virus with heparan sulfate.[15][17] However, in general virus-cell interactions are mediated by commonly occurring molecules on the cell surface, and therefore are likely not a major contributor to individual viruses' observed cell-type tropism.[15] After binding to molecules on the cell surface, the virion is endocytosed and enters the endoplasmic reticulum - a behavior unique among known non-enveloped viruses[18] - where the viral capsid structure is likely to be disrupted by action of host cell disulfide isomerase enzymes.[2][12][19]

The details of transit to the nucleus are not clear and may vary among individual polyomaviruses. It has been frequently reported that an intact, albeit distorted, virion particle is released from the endoplasmic reticulum into the cell cytoplasm, where the genome is released from the capsid, possibly due to the low calcium concentration in the cytoplasm.[18] Both expression of viral genes and replication of the viral genome occur in the nucleus using host cell machinery. The early genes - comprising at minimum the small tumor antigen (ST) and large tumor antigen (LT) - are expressed first, from a single alternatively spliced messenger RNA strand. These proteins serve to manipulate the host's cell cycle - dysregulating the transition from G1 phase to S phase, when the host cell's genome is replicated - because host cell DNA replication machinery is needed for viral genome replication.[2][12][15] The precise mechanism of this dysregulation depends on the virus; for example, SV40 LT can directly bind host cell p53, but murine polyomavirus LT does not.[20] LT induces DNA replication from the viral genome's non-coding control region (NCCR), after which expression of the early mRNA is reduced and expression of the late mRNA, which encodes the viral capsid proteins, begins.[19] As these interactions begin, the LTs belonging to several polyomaviruses, including Merkel cell polyomavirus, present oncogenic potential.[21] Several mechanisms have been described for regulating the transition from early to late gene expression, including the involvement of the LT protein in repressing the early promoter,[19] the expression of un-terminated late mRNAs with extensions complementary to early mRNA,[15] and the expression of regulatory microRNA.[15] Expression of the late genes results in accumulation of the viral capsid proteins in the host cell cytoplasm. Capsid components enter the nucleus in order to encapsidate new viral genomic DNA. New virions may be assembled in viral factories.[2][12] The mechanism of viral release from the host cell varies among polyomaviruses; some express proteins that facilitate cell exit, such as the agnoprotein or VP4.[19] In some cases high levels of encapsidated virus result in cell lysis, releasing the virions.[15]

The large tumor antigen plays a key role in regulating the viral life cycle by binding to the viral origin of DNA replication where it promotes DNA synthesis. Also as the polyomavirus relies on the host cell machinery to replicate the host cell needs to be in s-phase for this to begin. Due to this, large T-antigen also modulates cellular signaling pathways to stimulate progression of the cell cycle by binding to a number of cellular control proteins.[22] This is achieved by a two prong attack of inhibiting tumor suppressing genes p53 and members of the retinoblastoma (pRB) family,[23] and stimulating cell growth pathways by binding cellular DNA, ATPase-helicase, DNA polymerase α association, and binding of transcription preinitiation complex factors.[24] This abnormal stimulation of the cell cycle is a powerful force for oncogenic transformation.

The small tumor antigen protein is also able to activate several cellular pathways that stimulate cell proliferation. Polyomavirus small T antigens commonly target protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A),[25] a key multisubunit regulator of multiple pathways including Akt, the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway, and the stress-activated protein kinase (SAPK) pathway.[26][27] Merkel cell polyomavirus small T antigen encodes a unique domain, called the LT-stabilization domain (LSD), that binds to and inhibits the FBXW7 E3 ligase regulating both cellular and viral oncoproteins.[28] Unlike for SV40, the MCV small T antigen directly transforms rodent cells in vitro.[29]

The middle tumor antigen is used in model organisms developed to study cancer, such as the MMTV-PyMT system where middle T is coupled to the MMTV promoter. There it functions as an oncogene, while the tissue where the tumor develops is determined by the MMTV promoter.

The polyomavirus capsid consists of one major component, major capsid protein VP1, and one or two minor components, minor capsid proteins VP2 and VP3. VP1 pentamers form the closed icosahedral viral capsid, and in the interior of the capsid each pentamer is associated with one molecule of either VP2 or VP3.[5][30] Some polyomaviruses, such as Merkel cell polyomavirus, do not encode or express VP3.[31] The capsid proteins are expressed from the late region of the genome.[5]

The agnoprotein is a small multifunctional phospho-protein found in the late coding part of the genome of some polyomaviruses, most notably BK virus, JC virus, and SV40. It is essential for proliferation in the viruses that express it and is thought to be involved in regulating the viral life cycle, particularly replication and viral exit from the host cell, but the exact mechanisms are unclear.[32][33]

The polyomaviruses are members of group I (dsDNA viruses). The classification of polyomaviruses has been the subject of several proposed revisions as new members of the group are discovered. Formerly, polyomaviruses and papillomaviruses, which share many structural features but have very different genomic organizations, were classified together in the now-obsolete family Papovaviridae.[34] (The name Papovaviridae derived from three abbreviations: Pa for Papillomavirus, Po for Polyomavirus, and Va for "vacuolating.")[35] The polyomaviruses were divided into three major clades (that is, genetically-related groups): the SV40 clade, the avian clade, and the murine polyomavirus clade.[36] A subsequent proposed reclassification by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) recommended dividing the family of Polyomaviridae into three genera:[37]

The current ICTV classification system recognises six genera and 117 species, of which five could not be assigned a genus. This system retains the distinction between avian and mammalian viruses, grouping the avian subset into the genus Gammapolyomavirus. The six genera are:[3]

The following species are unassigned to a genus:[3]

Description of additional viruses is ongoing. These include the sea otter polyomavirus 1[38] and Alpaca polyomavirus[39] Another virus is the giant panda polyomavirus 1.[40] Another virus has been described from sigmodontine rodents.[41] Another - tree shrew polyomavirus 1 - has been described in the tree shrew.[42]

Most polyomaviruses do not infect humans. Of the polyomaviruses cataloged as of 2017, a total of 14 were known with human hosts.[4] However, some polyomaviruses are associated with human disease, particularly in immunocompromised individuals. MCV is highly divergent from the other human polyomaviruses and is most closely related to murine polyomavirus. Trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus (TSV) is distantly related to MCV. Two viruses—HPyV6 and HPyV7—are most closely related to KI and WU viruses, while HPyV9 is most closely related to the African green monkey-derived lymphotropic polyomavirus (LPV).

A fourteenth virus has been described.[43] Lyon IARC polyomavirus is related to raccoon polyomavirus.

The following 14 polyomaviruses with human hosts had been identified and had their genomes sequenced as of 2017:[4]

Deltapolyomavirus contains only the four human viruses shown in the above table. The Alpha and Beta groups contain viruses that infect a variety of mammals. The Gamma group contains the avian viruses.[4] Clinically significant disease associations are shown only where causality is expected.[5][63]

Antibodies to the monkey lymphotropic polyomavirus have been detected in humans suggesting that this virus - or a closely related virus - can infect humans.[64]

All the polyomaviruses are highly common childhood and young adult infections.[65] Most of these infections appear to cause little or no symptoms. These viruses are probably lifelong persistent among almost all adults. Diseases caused by human polyomavirus infections are most common among immunocompromised people; disease associations include BK virus with nephropathy in renal transplant and non-renal solid organ transplant patients,[8][9] JC virus with progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy,[10] and Merkel cell virus (MCV) with Merkel cell cancer.[11]

SV40 replicates in the kidneys of monkeys without causing disease, but can cause cancer in rodents under laboratory conditions. In the 1950s and early 1960s, well over 100 million people may have been exposed to SV40 due to previously undetected SV40 contamination of polio vaccine, prompting concern about the possibility that the virus might cause disease in humans.[66][67] Although it has been reported as present in some human cancers, including brain tumors, bone tumors, mesotheliomas, and non-Hodgkin's lymphomas,[68] accurate detection is often confounded by high levels of cross-reactivity for SV40 with widespread human polyomaviruses.[67] Most virologists dismiss SV40 as a cause for human cancers.[66][69][70]

The diagnosis of polyomavirus almost always occurs after the primary infection as it is either asymptomatic or sub-clinical. Antibody assays are commonly used to detect presence of antibodies against individual viruses.[71] Competition assays are frequently needed to distinguish among highly similar polyomaviruses.[72]

In cases of progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy (PML), a cross-reactive antibody to SV40 T antigen (commonly Pab419) is used to stain tissues directly for the presence of JC virus T antigen. PCR can be used on a biopsy of the tissue or cerebrospinal fluid to amplify the polyomavirus DNA. This allows not only the detection of polyomavirus but also which sub type it is.[73]

There are three main diagnostic techniques used for the diagnosis of the reactivation of polyomavirus in polyomavirus nephropathy (PVN): urine cytology, quantification of the viral load in both urine and blood, and a renal biopsy.[71] The reactivation of polyomavirus in the kidneys and urinary tract causes the shedding of infected cells, virions, and/or viral proteins in the urine. This allows urine cytology to examine these cells, which if there is polyomavirus inclusion of the nucleus, is diagnostic of infection.[74] Also as the urine of an infected individual will contain virions and/or viral DNA, quantitation of the viral load can be done through PCR.[75] This is also true for the blood.

Renal biopsy can also be used if the two methods just described are inconclusive or if the specific viral load for the renal tissue is desired. Similarly to the urine cytology, the renal cells are examined under light microscopy for polyomavirus inclusion of the nucleus, as well as cell lysis and viral partials in the extra cellular fluid. The viral load as before is also measure by PCR.

Tissue staining using a monoclonal antibody against MCV T antigen shows utility in differentiating Merkel cell carcinoma from other small, round cell tumors.[76] Blood tests to detect MCV antibodies have been developed and show that infection with the virus is widespread although Merkel cell carcinoma patients have exceptionally higher antibody responses than asymptomatically infected persons.[7][77][78][79]

The JC virus offers a promising genetic marker for human evolution and migration.[80] It is carried by 70–90 percent of humans and is usually transmitted from parents to offspring. This method does not appear to be reliable for tracing the recent African origin of modern humans.

Murine polyomavirus was the first polyomavirus discovered, having been reported by Ludwik Gross in 1953 as an extract of mouse leukemias capable of inducing parotid gland tumors.[81] The causative agent was identified as a virus by Sarah Stewart and Bernice Eddy, after whom it was once called "SE polyoma".[82][83][84] The term "polyoma" refers to the viruses' ability to produce multiple (poly-) tumors (-oma) under certain conditions. The name has been criticized as a "meatless linguistic sandwich" ("meatless" because both morphemes in "polyoma" are affixes) giving little insight into the viruses' biology; in fact, subsequent research has found that most polyomaviruses rarely cause clinically significant disease in their host organisms under natural conditions.[85]

Dozens of polyomaviruses have been identified and sequenced as of 2017, infecting mainly birds and mammals. Two polyomaviruses are known to infect fish, the black sea bass[86] and gilthead seabream.[87] A total of fourteen polyomaviruses are known to infect humans.[4]

Polyomaviridae is a family of viruses whose natural hosts are primarily mammals and birds. As of 2020, there are six recognized genera and 117 species, five of which are unassigned to a genus. 14 species are known to infect humans, while others, such as Simian Virus 40, have been identified in humans to a lesser extent. Most of these viruses are very common and typically asymptomatic in most human populations studied. BK virus is associated with nephropathy in renal transplant and non-renal solid organ transplant patients, JC virus with progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, and Merkel cell virus with Merkel cell cancer.

Polyomaviridae es una familia de virus que tiene como huésped natural a las aves y los mamíferos. De acuerdo a la revisión de 2018 hecho por la ICTV, la familia Polyomaviridae contiene 4 géneros, y 9 especies sin género. Hay catorce especies conocidos a infectar a los humanos. Muchos de estos virus afectan a mucho de la población humana sin causar mucho daño.[1]

Los poliomavirus tienen un genoma ADN de cadena doble y por lo tanto se incluyen en el Grupo I de la Clasificación de Baltimore. El genoma es circular, de 5000 pares de bases. Los virus tienen un tamaño pequeño, 40-50 nm de diámetro, forma icosaédrica y carecen de envoltura de lipoproteína.[2] Son potencialmente oncogénicos (causantes de tumores); frecuentemente persisten como infecciones latentes en un hospedante sin causar enfermedad, pero pueden producir tumores en un huésped de especie diferente, o en un huésped con un ineficiente sistema inmunitario. El nombre polioma refiere a la habilidad del virus de producir múltiples (poli) tumores (oma).

El género Poliomavirus solía ser uno de los dos géneros dentro de la familia ahora obsoleta Papovaviridae (el otro género, el virus del papiloma, ahora se clasifica en su propia familia, Papillomaviridae).

La mayoría de los poliomavirus no afectan a los seres humanos. Se conocen 14 especies de poliomavirus que infectan humanos.

Los géneros Alpha, Beta, Delta y Gamma se formaron en parte por los huéspedes de los virus.[3] El género Delta típicamente se detecta en la piel. El género Gamma refiere a los poliomavirus que afectan a las aves. [4]

El Virus vacuolante del simio 40 se replica en los riñones de monos sin causar enfermedad, pero causa sarcomas en hámsters. Se desconoce si puede causar enfermedades en los seres humanos, lo que ha causado preocupaciones, ya que el virus puede haber sido introducido en la población general en la década de 1950 a través de una vacuna contra la polio contaminada. Una hipótesis similar postula que esta vacuna pudo haber sido la causa de la transmisión del virus del sida de los chimpancés a los humanos. El Virus de la enfermedad del polluelo del periquito es una causa frecuente de muerte entre las aves enjauladas.

Antes de la replicación del genoma tienen lugar los procesos de fijación, entrada y liberación de la cubierta. Actualmente se desconocen los receptores celulares para los poliomavirus, sin embargo, la fijación del poliomavirus a la célula huésped es mediada por la proteína viral 1 (VP1). Esto se ha demostrado al comprobarse que los anticuerpos anti-VP1 previenen la unión del poliomavirus a la célula huésped.[14]

A continuación los viriones son endocitados y posteriormente transportados directamente al núcleo en vacuolas endocíticas en donde se produce la liberación de la cubierta del virus.

Los poliomavirus se replican en el núcleo de la célula huésped. Son capaces de utilizar la maquinaria genómica del huésped puesto que su estructura genómica es homóloga a la del huésped mamífero. La replicación viral se produce en dos fases distintas: expresión de genes inicial y final, separadas por la replicación del genoma.

La expresión de genes inicial es la responsable de la síntesis de proteínas no estructurales. Puesto que los poliomavirus confían en el huésped para el control de la expresión génica, la función de las proteínas no estructurales es la de regular los mecanismos celulares. Cerca del terminal N del genoma del poliomavirus hay elementos potenciadores que inducen la activación y transcripción de una molécula conocida como el antígeno T. El ARNm inicial codifica antígenos T que son producidos por la ARN polimerasa II del huésped. El antígeno T autorregula el ARNm inicial, que posteriormente conduce a niveles elevados del antígeno T. A altas concentraciones del antígeno T, la expresión génica inicial es reprimida, dando lugar al comienzo de la fase final de la infección viral.

La replicación genómica separa las fases inicial y final de la expresión génica. El genoma viral duplicado es sintetizado y procesado como si se tratara de ADN celular, explotando la maquinaria del huésped. Puesto que el ADN viral sintetizado se asocia con nucleosomas celulares para formar estructuras, a menudo son denominados "minicromosomas". De esta forma, el ADN es empaquetado de la manera más eficiente.

La expresión de genes final sintetiza las proteínas estructurales, responsables de la composición de las partículas virales. Esto ocurre durante y después de la replicación del genoma. Al igual que con los primeros productos de la expresión génica, la expresión génica final genera una serie de proteínas como resultado de una organización alternativa.

Dentro de cada proteína viral hay "señales de localización nuclear", que causa que las proteínas se acumulen en el núcleo. El ensamblado de las nuevas partículas virales, en consecuencia, produce en el núcleo de la célula huésped.

La liberación de las partículas de poliomavirus nuevamente sintetizadas de la célula infectada se realiza por uno de dos mecanismos. La primera y la menos frecuente es el transporte en vacuolas citoplasmáticas a la membrana plasmática, donde se produce la gemación. Con más frecuencia se liberan cuando la célula se lisa debido a la citotoxicidad de las partículas de virus presentes en la célula infectada.

El primer poliomavirus descrito fue el poliomavirus murino. En 1951, Ludwig Gross describió que era posible transmitir la leucemia entre ratones recién nacidos usando extractos libres de células. Fueron las virólogas Sarah Stewart y Bernice Eddy quienes identificaron y estudiaron extensivamente el agente infeccioso, al que le dieron el nombre de poliomavirus SE (Stewart-Eddy). «Polioma» significa «muchos tumores» etimológicamente.[15]

|número-autores= (ayuda) |url= incorrecta con autorreferencia (ayuda). Wikipedia, la enciclopedia libre. 22 de octubre de 2019. Consultado el 24 de marzo de 2020. Polyomaviridae es una familia de virus que tiene como huésped natural a las aves y los mamíferos. De acuerdo a la revisión de 2018 hecho por la ICTV, la familia Polyomaviridae contiene 4 géneros, y 9 especies sin género. Hay catorce especies conocidos a infectar a los humanos. Muchos de estos virus afectan a mucho de la población humana sin causar mucho daño.

Poliomawirusy (Polyomaviridae, z gr. poli-oma – liczne guzy) – rodzina wirusów, zaliczanych do grupy papowawirusów, charakteryzująca się następującymi cechami:

Wśród poliomawirusów wyróżnia się tylko jeden rodzaj Polyomavirus. Z medycznego lub naukowego punktu widzenia najistotniejsze są trzy gatunki:

Wirus BK – wyizolowany został od pacjenta o takich inicjałach w roku 1971[1]. Jest on bardzo powszechnym wirusem, którym większość z nas zakaża się już we wczesnym dzieciństwie. Około 70-90% dorosłych wykazuje obecność przeciwciał zarówno dla wirusa BK, jak i wirusa JC. W zasadzie nie daje żadnych objawów – pojawiają się one tylko u nielicznej grupy pacjentów, mających problemy z układem moczowym, np. przewężenie cewki moczowej. Zdrowi osobnicy nie wydalają wirusa, taka sytuacja zachodzi jedynie w okresie ciąży oraz u osób poddanych immunosupresji.

Wirus JC – podobnie do wirusa BK, jego nazwa pochodzi od inicjałów pacjenta, z którego go wyizolowano (1971)[2]. Jest on czynnikiem etiologicznym, wywołującym postępującą wieloogniskową leukoencefalopatię. Do niedawna nie miało to większego znaczenia, gdyż wirus uaktywnia się tylko u osób poddanych immunosupresji – głównie ludzi starszych lub w przypadku niektórych chorób. Jednak od czasu pojawienia się i rozprzestrzenienia się HIV, wirus JC stanowi dosyć poważny problem.

2 nowe ludzkie poliomawirusy zostały odkryte w 2007 roku w instytutach Karolinska Institutet w Sztokholmie i Washington University w St. Louis, Missouri, stąd też pochodzą ich nazwy: KI[3] i WU[4]. W 2008 roku zidentyfikowano wirusa, który może powodować raka neuroendokrynnego skóry[5]. Dokładna rola trzech nowo odkrytych poliomawirusów jak dotąd nie jest jednak znana.

Wirusy polioma, wcześniej kojarzone z nowotworami, obecnie nie są uważane za istotne czynniki etiologiczne tych chorób. Wydaje się, że mogą one mieć wpływ na nowotworzenie, ich DNA występuje często w komórkach pewnych nowotworów, jednak obecnie wykazano, że większość dotychczas obserwowanych efektów tego typu związana była z innymi wirusami, współwystępującymi jedynie z BK lub JC.

Poliomawirusy (Polyomaviridae, z gr. poli-oma – liczne guzy) – rodzina wirusów, zaliczanych do grupy papowawirusów, charakteryzująca się następującymi cechami:

Symetria: ikosaedralna Otoczka lipidowa: brak Kwas nukleinowy: kolisty dsDNA Replikacja: zachodzi w jądrze zakażonej komórki Wielkość: ok. 45 nm Gospodarz: kręgowce Cechy dodatkowe: w odróżnieniu od podobnych do nich papillomawirusów, są łatwe w hodowli na standardowych liniach komórkowych i wywołują efekty cytopatycznePolyomaviridae

Роды Группа по БалтиморуI: дцДНК-вирусы

Полиомавирусы[2] (лат. Polyomaviridae) — семейство безоболочечных вирусов. Относится к I группе классификации вирусов по Балтимору. В соответствии с ревизией, утверждённой Международным комитетом по таксономии вирусов (ICTV) в 2016 году, включает 4 рода[3].

В 1953 году Людвиком Гроссом был описан полиомавирус мыши[4]. Позже были описаны многие полиомавирусы, инфицирующие птиц и млекопитающих. Род Polyomavirus, их объединяющей, относили сначала к семейству Papovaviridae, а с 1999 года, после разделения последнего, — к семейству Polyomaviridae[5].

Полиомавирусы широко изучают как опухолеродные вирусы для человека и животных. Белок p53, супрессор опухолей, например, был выделен как клеточный белок, связанный с большим Т-антигеном вируса SV40.

Полиомавирусы являются ДНК-содержащими вирусами (геном представлен кольцевой двуцепочечной ДНК длиной порядка 5000 пар оснований), вирионы небольшие, диаметр порядка 40—50 нм, икосаэдрической формы, не покрыты липидной оболочкой. Вирусы обычно онкогенные, часто находятся в организме хозяина в латентном состоянии и не вызывают болезнь, но образуют опухоли в организмах других видов, либо в случае иммунного дефицита хозяина. Корень «полиома» в названии вируса говорит о том, что вирусы способны вызывать множественные опухоли.

Большой Т-антиген играет важную роль в регуляции жизненного цикла вируса, связываясь с вирусной ДНК, и усиливая её репликацию. Для репликации полиомавирусам требуются ферменты метаболизма нуклеиновых кислот клетки, поэтому репликация геномной вирусной ДНК возможна только в S-фазу клеточного цикла. Большой Т-антиген связывается с белками контроля клеточного цикла и стимулирует начало репликации ДНК[6]. Это достигается за счет ингибирования гена супрессора опухоли p53 и генов семейства ретинобластомы. При этом клеточные деления стимулируются за счет связывания с клеточной ДНК, геликазой, ДНК-полимеразой α и факторов преинициации транскрипции[7]. Такие изменения клеточного цикла приводят к онкогенной трансформации.

Малый Т-антиген также активирует некоторые клеточные пути, стимулирующие пролиферацию клеток, например, путь митоген-активируемой протеинкиназы (англ. MAPK), и стресс-активируемой протеинкиназы (англ. SAPK)[8][9].

В 2015 году род Polyomavirus, единственный на тот момент в семействе полиомавирусов, включал 13 видов[10]. В результате ревизии 2016 года в семействе образовали 4 новых рода и включили 68 новых видов[11], удалили род Polyomavirus и 5 старых видов (African green monkey polyomavirus, Baboon polyomavirus 2, Human polyomavirus, Rabbit kidney vacuolating virus, Simian virus 12)[12], а остальные виды распределили по новым родам и сменили им названия[13]. По данным ICTV, на март 2017 года в классификация семейства следующая[14]:

С 2016 года регистрированы 13 видов полиомавирусов, поражающих людей:

Вид Род Название вида до 2016 г.[15] Код Human polyomavirus 1 Betapolyomavirus BK polyomavirus BKPyV Human polyomavirus 2 Betapolyomavirus JC polyomavirus JCPyV Human polyomavirus 3 Betapolyomavirus KI polyomavirus KIPyV[16] Human polyomavirus 4 Betapolyomavirus WU polyomavirus WUPyV[16] Human polyomavirus 5 Alphapolyomavirus Merkel cell polyomavirus MCPyV[17] Human polyomavirus 6 Deltapolyomavirus — — Human polyomavirus 7 Deltapolyomavirus — — Human polyomavirus 8 Alphapolyomavirus Trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus TSPyV[17] Human polyomavirus 9 Alphapolyomavirus — — Human polyomavirus 10 Deltapolyomavirus MW polyomavirus MWPyV[18] Human polyomavirus 11 Deltapolyomavirus STL polyomavirus StLPyV[18] Human polyomavirus 12 Alphapolyomavirus — — Human polyomavirus 13 Alphapolyomavirus New Jersey polyomavirus NJPyV[17]Инфекцию, вызываемую Human polyomavirus 1—4, сложно отличить от инфекции, вызываемой Macaca mulatta polyomavirus 1[19][20].

Human polyomavirus 1 приводит к мягким респираторным инфекциям, и поражает почки у пациентов со сниженной иммунной системой, например, после трансплантации органов. Human polyomavirus 2 поражает клетки дыхательной системы, почек или мозга. Оба эти вируса широко распространены в популяции, порядка 80 % взрослых жителей США имеют антитела к этим вирусам.

Human polyomavirus 5 описан в 2008 году, вызывает рак кожи Меркеля[21][22][23].

Human polyomavirus 8 описан в 2010 году, вызывает триходисплазию.

|month= (справка) |month= (справка) |month= (справка) |month= (справка) |month= (справка) |month= (справка) |month= (справка) |month= (справка) |month= (справка) Полиомавирусы (лат. Polyomaviridae) — семейство безоболочечных вирусов. Относится к I группе классификации вирусов по Балтимору. В соответствии с ревизией, утверждённой Международным комитетом по таксономии вирусов (ICTV) в 2016 году, включает 4 рода.

多瘤病毒科(Polyomaviridae)是一種雙鏈DNA病毒,這類的病毒會造成腫瘤,其中有些種類會感染人的呼吸系統、腎臟或腦部。

下有一屬: