pms

nòm ant ël fil

Der Oleander (Nerium oleander), auch Rosenlorbeer genannt, ist die einzige Art der Pflanzengattung Oleander (Nerium) innerhalb der Familie der Hundsgiftgewächse (Apocynaceae). Alle Pflanzenteile sind giftig. Es gibt mehr als 200 Sorten.

Als Gelber, Tropischer oder Karibischer Oleander ist die ebenfalls giftige Thevetia peruviana, der Schellenbaum, bekannt.

Der Oleander ist eine immergrüne bis 6 Meter hohe verholzende Pflanze, meist ein Busch. Die normalerweise zu dritt, wirtelig, seltener gegenständig, am Zweig angeordneten einfachen Laubblätter sind kurz gestielt, ledrig, steiflich, oberseits dunkelgrün und bei einer Länge von 6 bis 24 Zentimeter lanzettlich bis verkehrt-eiförmig, -eilanzettlich. Die Breite der ganzrandigen, meist spitzen bis seltener abgerundeten und meist kahlen Blattspreite kann bis zu 5 Zentimeter betragen. Die Nervatur ist fein gefiedert mit vielen Seitenadern.

Die Blütezeit erstreckt sich von Mitte Juni bis in den September hinein. Mehrere duftende, kurz gestielte Blüten stehen in einem gestielten trugdoldigen und endständigen Blütenstand zusammen. Die zwittrigen Blüten sind radiärsymmetrisch und in der Normalform fünfzählig mit doppelter Blütenhülle. Der Kelch ist nur klein, mit schmal-dreieckigen Zipfeln. Die Blütenkronblätter sind trichterförmig verwachsen mit ausladenden Kronlappen, sie sind je nach Sorte, weiß, gelblich oder in verschiedenen Rosa- bis Violetttönen. Wilde Oleander blühen meist rosarot. Die Petalen besitzen innen an der Basis, am Schlund, fransige Anhängsel (eine Corona). Die Staubblätter mit relativ kurzen Staubfäden, oben in der Kronröhre, mit langen und haarigen, federigen oft ineinander verdrehten Anhängseln an den pfeilförmigen Antheren, sind dem Griffelkopf (Clavuncula) anhaftend.[1] Der zweifächerige Stempel mit behaartem Fruchtknoten ist oberständig. Ob Nektar produziert wird oder eine sekundäre Pollenpräsentation stattfindet, ist nicht ganz klar.[1]

Es werden bis 23 Zentimeter lange und trockene, geriefte, rippige sowie schmale Balgfrüchte mit beständigem Kelch gebildet und die vielen schmal-kegelförmigen Samen sind dicht behaart mit einem einseitigen Haarschopf.

Die Chromosomengrundzahl beträgt x = 11; bei der Wildform liegt Diploidie vor mit einer Chromosomenzahl von 2n = 22.[2][3]

Der Oleander hat ein großes Verbreitungsgebiet in einem Streifen von Marokko (hier bis in Höhenlagen von 2000 Meter) und Südspanien über den ganzen Mittelmeerraum, den Nahen bis Mittleren Osten, Indien bis China und Myanmar.[4] Die früher vertretene Auffassung, bei den asiatischen Wildformen handele es sich um eine eigene Art (Nerium indicum), wird wegen der zu geringen Unterschiede im Phänotyp nicht mehr bestätigt.[4] Nerium oleander ist in vielen frostfreien Gebieten der Welt ein Neophyt.[5]

Der Oleander wächst im Mittelmeerraum von Natur aus in südmediterranen Auengesellschaften (Nerio-Tamaricetea).[2]

Die Gattung Nerium wurde 1753 mit der Art Nerium oleander durch Carl von Linné in Species Plantarum, 1, Seite 209. aufgestellt.[6]

Die Gattung Nerium wird meist als monotypisch angesehen,[7][8] die einzige Art ist Nerium oleander. Seltener wird zur Gattung mehr als eine Art gerechnet.[9]

Bei der Kübelhaltung ist auf eine gute Wässerung und Düngung in der warmen Jahreszeit zu achten. Im Winter sollte der Oleander kühl (5–10 °C sind ideal) gehalten werden, eine Überwinterung im beheizten Wohnraum ist wegen der Gefahr von starkem Spinnmilbenbefall und Vergeilung zu vermeiden.

Oleander wird in Mitteleuropa meistens als Kübelpflanze gehalten; es gibt unter den insgesamt mehr als 200 Sorten auch einige, die in den meisten Gebieten Deutschlands mit Winterschutz auspflanzfähig sind.

Die folgenden Sorten überstanden in Feldversuchen −10 °C praktisch schadlos: 'Nerium villa romaine', 'Nerium atlas', 'Nerium italia', 'Nerium cavalaire'. Bei Temperaturen darunter beginnen zunächst einzelne Blätter abzusterben. Unter ca. −15 °C sterben die meisten Blätter ab, ab ca. −18 °C auch vermehrt das Stammholz. Selbst nach Temperaturen unter −20 °C und völligem oberirdischem Absterben können die Pflanzen im Frühjahr jedoch wieder neu austreiben.

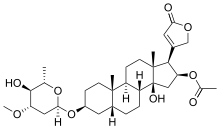

Oleander enthält verschiedene Cardenolide, darunter das giftige und pharmakologisch relevante Glykosid Oleandrin.[10] Alle Pflanzenteile sind giftig. Oleandrin ist ein giftiges Herzglykosid und wirkt erregend auf die interkardiale Muskeltätigkeit. Außerdem werden das Brechreizzentrum und der Nervus vagus aktiviert. Es verursacht Hypoxämie; dies bedeutet einen erniedrigten Sauerstoffgehalt (CaO2) im arteriellen Blut.[11] Beim Umtopfen und Beschneiden sollten Handschuhe getragen werden. Selbst der Rauch des Oleanders ist giftig. Grünschnitt sollte nicht verbrannt, sondern im Hausmüll entsorgt werden.

Lorandum, der mittellateinische Name der Pflanze, ist eine Wortbildung zu lateinisch laurus „Lorbeer“. Diese Namensgebung beruhte wahrscheinlich auf der Ähnlichkeit der Blätter. Unter dem Einfluss von lateinisch olea „Olivenbaum“ entstand aus lorandum die italienische Wortform oleandro und daraus Oleander.[12]

Der Gattungsname Nerium, eine latinisierte Form von altgriechisch νήριον nḗrion, bedeutet ebenfalls „Oleander“.[13]

Der Oleander (Nerium oleander), auch Rosenlorbeer genannt, ist die einzige Art der Pflanzengattung Oleander (Nerium) innerhalb der Familie der Hundsgiftgewächse (Apocynaceae). Alle Pflanzenteile sind giftig. Es gibt mehr als 200 Sorten.

Als Gelber, Tropischer oder Karibischer Oleander ist die ebenfalls giftige Thevetia peruviana, der Schellenbaum, bekannt.

Nerium oleander (/ˈnɪəriəm ... / NEER-ee-əm),[2] most commonly known as oleander or nerium, is a shrub or small tree cultivated worldwide in temperate and subtropical areas as an ornamental and landscaping plant. It is the only species currently classified in the genus Nerium, belonging to subfamily Apocynoideae of the dogbane family Apocynaceae. It is so widely cultivated that no precise region of origin has been identified, though it is usually associated with the Mediterranean Basin.

Nerium grows to 2–6 metres (7–20 feet) tall. It is most commonly grown in its natural shrub form, but can be trained into a small tree with a single trunk. It is tolerant to both drought and inundation, but not to prolonged frost. White, pink or red five-lobed flowers grow in clusters year-round, peaking during the summer. The fruit is a long narrow pair of follicles, which splits open at maturity to release numerous downy seeds.

Nerium contains several toxic compounds, and it has historically been considered a poisonous plant. However, its bitterness renders it unpalatable to humans and most animals, so poisoning cases are rare and the general risk for human mortality is low. Ingestion of larger amounts may cause nausea, vomiting, excess salivation, abdominal pain, bloody diarrhea and irregular heart rhythm. Prolonged contact with sap may cause skin irritation, eye inflammation and dermatitis.

Oleander grows to 2–6 metres (7–20 feet) tall, with erect stems that splay outward as they mature; first-year stems have a glaucous bloom, while mature stems have a grayish bark. The leaves are in pairs or whorls of three, thick and leathery, dark-green, narrow lanceolate, 5–21 centimetres (2–8 inches) long and 1–3.5 cm (3⁄8–1+3⁄8 in) broad, and with an entire margin filled with minute reticulate venation web typical of eudicots. The leaves are light green and very glossy when young, maturing to a dull dark green.

The flowers grow in clusters at the end of each branch; they are white, pink to red,[Note 1] 2.5–5 cm (1–2 in) diameter, with a deeply 5-lobed fringed corolla round the central corolla tube. They are often, but not always, sweet-scented.[Note 2] The fruit is a long narrow pair of follicles 5–23 cm (2–9 in) long, which splits open at maturity to release numerous downy seeds.

Nerium oleander is the only species currently classified in the genus Nerium. It belongs to (and gives its name to) the small tribe Nerieae of subfamily Apocynoideae of the dogbane family Apocynaceae. The genera most closely-related thus include the equally ornamental (and equally toxic) Adenium G.Don and Strophanthus DC. - both of which contain (like oleander) potent cardiac glycosides that have led to their use as arrow poisons in Africa.[3] The three remaining genera Alafia Thouars, Farquharia Stapf and Isonema R.Br. are less well-known in cultivation.

The plant has been described under a wide variety of names that are today considered its synonyms:[4][5]

The taxonomic name Nerium oleander was first assigned by Linnaeus in 1753.[6] The genus name Nerium is the Latinized form of the Ancient Greek name for the plant nẽrion (νήριον), which is in turn derived from the Greek for water, nẽros (νηρός), because of the natural habitat of the oleander along rivers and streams.

The origins of the species name are disputed. The word oleander appears as far back as the first century AD, when the Greek physician Pedanius Dioscorides cited it as one of the terms used by the Romans for the plant.[7] Merriam-Webster believes the word is a Medieval Latin corruption of Late Latin names for the plant: arodandrum or lorandrum, or more plausibly rhododendron (another Ancient Greek name for the plant), with the addition of olea because of the superficial resemblance to the olive tree (Olea europea)[Note 3][8][9] Another theory posited is that oleander is the Latinized form of a Greek compound noun: οllyo (ὀλλύω) 'I kill', and the Greek noun for man, aner, genitive andros (ἀνήρ, ἀνδρός).[10] ascribed to oleander's toxicity to humans.

The etymological association of oleander with the bay laurel has continued into the modern day: in France the plant is known as "laurier rose",[11] while the Spanish term, "Adelfa", is the descendant of the original Ancient Greek name for both the bay laurel and the oleander, daphne, which subsequently passed into Arabic usage and thence to Spain.[12]

The ancient city of Volubilis in Morocco may have taken its name from the Berber name alili or oualilt for the flower.[13]

Nerium oleander is either native or naturalized to a broad area spanning from Northwest Africa and Iberian and Italian Peninsula eastward through the Mediterranean region and warmer areas of the Black Sea region, Arabian Peninsula, southern Asia, and as far east as Yunnan in southern parts of China.[14][15][16][17] It typically occurs around stream beds in river valleys, where it can alternatively tolerate long seasons of drought and inundation from winter rains. N. oleander is planted in many subtropical and tropical areas of the world.

On the East Coast of the US, it grows as far north as Virginia Beach, while in California and Texas miles of oleander shrubs are planted on median strips.[18] There are estimated to be 25 million oleanders planted along highways and roadsides throughout the state of California.[19] Because of its durability, oleander was planted prolifically on Galveston Island in Texas after the disastrous Hurricane of 1900. They are so prolific that Galveston is known as the 'Oleander City'; an annual oleander festival is hosted every spring.[20] Moody Gardens in Galveston hosts the propagation program for the International Oleander Society, which promotes the cultivation of oleanders. New varieties are hybridized and grown on the Moody Gardens grounds, encompassing every named variety.[21]

Beyond the traditional Mediterranean and subtropical range of oleander, the plant can also be cultivated in mild oceanic climates with the appropriate precautions. It is grown without protection in warmer areas in Switzerland, southern and western Germany and southern England and can reach great sizes in London and to a lesser extent in Paris[22] due to the urban heat island effect.[23][24][25] This is also the case with North American cities in the Pacific Northwest like Portland,[26] Seattle, and Vancouver. Plants may suffer damage or die back in such marginal climates during severe winter cold but will rebound from the roots.

Some invertebrates are known to be unaffected by oleander toxins, and feed on the plants. Caterpillars of the polka-dot wasp moth (Syntomeida epilais) feed specifically on oleanders and survive by eating only the pulp surrounding the leaf-veins, avoiding the fibers. Larvae of the common crow butterfly (Euploea core) and oleander hawk-moth (Daphnis nerii) also feed on oleanders, and they retain or modify toxins, making them unpalatable to potential predators such as birds, but not to other invertebrates such as spiders and wasps.[27]

The flowers require insect visits to set seed, and seem to be pollinated through a deception mechanism. The showy corolla acts as a potent advertisement to attract pollinators from a distance, but the flowers are nectarless and offer no reward to their visitors. They therefore receive very few visits, as typical of many rewardless flower species.[28][29] Fears of honey contamination with toxic oleander nectar are therefore unsubstantiated.

A bacterial disease known as oleander leaf scorch (Xylella fastidiosa subspecies sandyi[30]) has become an extremely serious threat to the shrub since it was first noticed in Palm Springs, California, in 1992.[31] The disease has since devastated hundreds of thousands of shrubs mainly in Southern California, but also on a smaller scale in Arizona, Nevada and Texas.[32][33] The culprit is a bacterium which is spread via insects (the glassy-winged sharpshooter primarily) which feed on the tissue of oleanders and spread the bacteria. This inhibits the circulation of water in the tissue of the plant, causing individual branches to die until the entire plant is consumed.

Symptoms of leaf scorch infection may be slow to manifest themselves, but it becomes evident when parts of otherwise healthy oleanders begin to yellow and wither, as if scorched by heat or fire. Die-back may cease during winter dormancy, but the disease flares up in summer heat while the shrub is actively growing, which allows the bacteria to spread through the xylem of the plant. As such it can be difficult to identify at first because gardeners may mistake the symptoms for those of drought stress or nutrient deficiency.[34]

Pruning out affected parts can slow the progression of the disease but not eliminate it.[31] This malaise can continue for several years until the plant completely dies—there is no known cure.[19] The best method for preventing further spread of the disease is to prune infected oleanders to the ground immediately after the infection is noticed.

The responsible pathogen was identified as the subspecies sandyi by Purcell et al., 1999.[30]

Nerium oleander has a history of cultivation going back millennia, especially amongst the great ancient civilizations of the Mediterranean Basin. Some scholars believe it to be the rhodon (rose), also called the 'Rose of Jericho', mentioned in apocryphal writings (Ecclesiasticus XXIV, 13)[35] dating back to between 450 and 180 BC.[36][37]

The ancient Greeks had several names for the plant, including rhododaphne, nerion, rhododendron and rhodon.[36] Pliny confirmed that the Romans had no Latin word for the plant, but used the Greek terms instead.[38] Pedanius Dioscorides states in his 1st century AD pharmacopeia De Materia Medica that the Romans used the Greek rhododendron but also the Latin Oleander and Laurorosa. The Egyptians apparently called it scinphe, the North Africans rhodedaphane, and the Lucanians (a southern Italic people) icmane.[39]

Both Pliny and Dioscorides stated that oleander was an effective antidote to venomous snake bites if mixed with rue and drunk. However, both rue and oleander are poisonous themselves, and consuming them after a venomous snake bite can accelerate the rate of mortality and increase fatalities.

A 2014 article in the medical journal Perspectives in Biology and Medicine posited that oleander was the substance used to induce hallucinations in the Pythia, the female priestess of Apollo, also known as the Oracle of Delphi in Ancient Greece.[40] According to this theory, the symptoms of the Pythia's trances (enthusiasmos) correspond to either inhaling the smoke of or chewing small amounts of oleander leaves, often called by the generic term laurel in Ancient Greece, which led to confusion with the bay laurel that ancient authors cite.

In his book Enquiries into Plants of circa 300 BC, Theophrastus described (among plants that affect the mind) a shrub he called onotheras, which modern editors render oleander: "the root of onotheras [oleander] administered in wine", he alleges, "makes the temper gentler and more cheerful".

The root of onotheras [oleander] administered in wine makes the temper gentler and more cheerful. The plant has a leaf like that of the almond, but smaller, and the flower is red like a rose. The plant itself (which loves hilly country) forms a large bush; the root is red and large, and, if this is dried, it gives off a fragrance like wine.

In another mention, of "wild bay" (Daphne agria), Theophrastus appears to intend the same shrub.[41]

Oleander was a very popular ornamental shrub in Roman peristyle gardens; it is one of the flora most frequently depicted on murals in Pompeii and elsewhere in Italy. These murals include the famous garden scene from the House of Livia at Prima Porta outside Rome, and those from the House of the Wedding of Alexander and the Marine Venus in Pompeii.[42]

Carbonized fragments of oleander wood have been identified at the Villa Poppaea in Oplontis, likewise buried by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD.[10] They were found to have been planted in a decorative arrangement with citron trees (Citrus medica) alongside the villa's swimming pool.

Herbaria of oleander varieties are compiled and held at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. and at Moody Gardens in Galveston, Texas.[21]

Oleander is a vigorous grower in warm subtropical regions, where it is extensively used as an ornamental plant in parks, along roadsides and in private gardens. It is most commonly grown in its natural shrub form, but can be trained into a small tree with a single trunk.[43] Hardy versions like white, red and pink oleander will tolerate occasional light frost down to −10 °C (14 °F),[17] though the leaves may be damaged. The toxicity of oleander renders it deer-resistant and its large size makes for a good windbreak – as such it is frequently planted as a hedge along property lines and in agricultural settings.

The plant is tolerant of poor soils, intense heat, salt spray, and sustained drought – although it will flower and grow more vigorously with regular water. Although it does not require pruning to thrive and bloom, oleander can become unruly with age and older branches tend to become gangly, with new growth emerging from the base. For this reason gardeners are advised to prune mature shrubs in the autumn to shape and induce lush new growth and flowering for the following spring.[33] Unless they wish to harvest the seeds, many gardeners choose to prune away the seedpods that form on spent flower clusters, which are a drain on energy.[33] Propagation can be made from cuttings, where they can readily root after being placed in water or in rich organic potting material, like compost.

In Mediterranean climates oleanders can be expected to bloom from April through October, with the heaviest bloom usually occurring between May and June. Free-flowering varieties like 'Petite Salmon' or 'Mont Blanc' require no period of rest and can flower continuously throughout the year if the weather remains warm.

In cold winter climates, oleander is a popular summer potted plant readily available at most nurseries. They require frequent heavy watering and fertilizing as compared to being planted in the ground, but oleander is nonetheless an ideal flowering shrub for patios and other spaces with hot sunshine. During the winter they should be moved indoors, ideally into an unheated greenhouse or basement where they can be allowed to go dormant.[43] Once they are dormant they require little light and only occasional watering. Placing them in a space with central heating and poor air flow can make them susceptible to a variety of pests – aphids, mealybugs, oleander scale, whitefly and spider mites.[44]

Oleander flowers are showy, profuse, and often fragrant, which makes them very attractive in many contexts. Over 400 cultivars have been named, with several additional flower colors not found in wild plants having been selected, including yellow, peach and salmon. Many cultivars, like 'Hawaii' or 'Turner's Carnival', are multi-colored, with brilliant striped corollas.[45] The solid whites, reds and a variety of pinks are the most common. Double flowered cultivars like 'Mrs. Isadore Dyer' (deep pink), 'Mathilde Ferrier' (yellow) or 'Mont Blanc' (white) are enjoyed for their large, rose-like blooms and strong fragrance. There is also a variegated form, 'Variegata', featuring leaves striped in yellow and white.[33] Several dwarf cultivars have also been developed, offering a more compact form and size for small spaces. These include 'Little Red', 'Petite White', 'Petite Pink' and 'Petite Salmon', which grow to about 8 feet (2.4 m) at maturity.[46]

Oleander has historically been considered a poisonous plant because of toxic compounds it contains, especially when consumed in large amounts. Among these compounds are oleandrin and oleandrigenin, known as cardiac glycosides, which are known to have a narrow therapeutic index and are toxic when ingested.

Toxicity studies of animals concluded that birds and rodents were observed to be relatively insensitive to the administered oleander cardiac glycosides.[47] Other mammals, however, such as dogs and humans, are relatively sensitive to the effects of cardiac glycosides and the clinical manifestations of "glycoside intoxication".[47][48][49]

In reviewing oleander toxicity cases seen in-hospital, Lanford and Boor[50] concluded that, except for children who might be at greater risk, "the human mortality associated with oleander ingestion is generally very low, even in cases of moderate intentional consumption (suicide attempts)."[50] In 2000, a rare instance of death from oleander poisoning occurred when two toddlers adopted from an orphanage ate the leaves from a neighbor's shrub in El Segundo, California.[51] A spokesman for the Los Angeles County Coroner's office stated that it was the first instance of death connected to oleander in the county, and a toxicologist from the California Poison Control Center said it was the first instance of death he had seen recorded. Because oleander is extremely bitter, officials speculated that the toddlers had developed a condition caused by malnutrition, pica, which causes people to eat otherwise inedible material.[52]

Ingestion of this plant can affect the gastrointestinal system, the heart, and the central nervous system. The gastrointestinal effects can consist of nausea and vomiting, excess salivation, abdominal pain, diarrhea that may contain blood, and especially in horses, colic.[16] Cardiac reactions consist of irregular heart rate, sometimes characterized by a racing heart at first that then slows to below normal further along in the reaction. Extremities may become pale and cold due to poor or irregular circulation. The effect on the central nervous system may show itself in symptoms such as drowsiness, tremors or shaking of the muscles, seizures, collapse, and even coma that can lead to death.[53]

Oleander poisoning can also result in blurred vision, and vision disturbances, including halos appearing around objects.[53]

Oleander sap can cause skin irritations, severe eye inflammation and irritation, and allergic reactions characterized by dermatitis.[54]

Poisoning and reactions to oleander plants are evident quickly, requiring immediate medical care in suspected or known poisonings of both humans and animals.[54] Induced vomiting and gastric lavage are protective measures to reduce absorption of the toxic compounds. Activated carbon may also be administered to help absorb any remaining toxins.[16] Further medical attention may be required depending on the severity of the poisoning and symptoms. Temporary cardiac pacing will be required in many cases (usually for a few days) until the toxin is excreted.

Digoxin immune fab is the best way to cure an oleander poisoning if inducing vomiting has no or minimal success, although it is usually used only for life-threatening conditions due to side effects.[55]

Drying of plant materials does not eliminate the toxins. It is also hazardous for animals such as sheep, horses, cattle, and other grazing animals, with as little as 100 g being enough to kill an adult horse.[56] Plant clippings are especially dangerous to horses, as they are sweet. In July 2009, several horses were poisoned in this manner from the leaves of the plant.[57] Symptoms of a poisoned horse include severe diarrhea and abnormal heartbeat. There is a wide range of toxins and secondary compounds within oleander, and care should be taken around this plant due to its toxic nature. Different names for oleander are used around the world in different locations, so, when encountering a plant with this appearance, regardless of the name used for it, one should exercise great care and caution to avoid ingestion of any part of the plant, including its sap and dried leaves or twigs. The dried or fresh branches should not be used for spearing food, for preparing a cooking fire, or as a food skewer. Many of the oleander relatives, such as the desert rose (Adenium obesum) found in East Africa, have similar leaves and flowers and are equally toxic.

Drugs derived from N. oleander have been investigated as a treatment for cancer, but have failed to demonstrate clinical utility.[58][59] According to the American Cancer Society, the trials conducted so far have produced no evidence of benefit, while they did cause adverse side effects.[60]

In a research study done by Haralampos V. Harissis, he claims that the laurel the Pythia is commonly depicted with is actually an oleander plant, and the poisonous plant and its subsequent hallucinations are the source of the oracle's mystical power and subsequent prophecies. Many of the symptoms that primary sources such as Plutarch and Democritus report align with results of oleander poisoning. Harissis also provides evidence claiming that the word laurel may have been used to describe an oleander leaf.[61]

The toxicity of the plant makes it the center of an urban legend documented on several continents and over more than a century. Often told as a true and local event, typically an entire family, or in other tellings a group of scouts, succumbs after consuming hot dogs or other food roasted over a campfire using oleander sticks.[62] Some variants tell of this happening to Napoleon's or Alexander the Great's soldiers.[63]

There is an ancient account mentioned by Pliny the Elder in his Natural History,[38] who described a region in Pontus in Turkey where the honey was poisoned from bees having pollinated poisonous flowers, with the honey left as a poisonous trap for an invading army.[64][65][66] The flowers have sometimes been mis-translated as oleander,[10] but oleander flowers are nectarless and therefore cannot transmit any toxins via nectar.[28] The actual flower referenced by Pliny was either Azalea or Rhododendron, which is still used in Turkey to produce a hallucinogenic honey.[67]

Oleander is the official flower of the city of Hiroshima, having been the first to bloom following the atomic bombing of the city in 1945.[68]

Oleander was part of subject matter of paintings by famous artists including:

Cultivated, Galveston

First oleander planted in Galveston (1841)

Follicle spreading seeds

N. oleander in West Bengal

Nerium oleander (/ˈnɪəriəm ... / NEER-ee-əm), most commonly known as oleander or nerium, is a shrub or small tree cultivated worldwide in temperate and subtropical areas as an ornamental and landscaping plant. It is the only species currently classified in the genus Nerium, belonging to subfamily Apocynoideae of the dogbane family Apocynaceae. It is so widely cultivated that no precise region of origin has been identified, though it is usually associated with the Mediterranean Basin.

Nerium grows to 2–6 metres (7–20 feet) tall. It is most commonly grown in its natural shrub form, but can be trained into a small tree with a single trunk. It is tolerant to both drought and inundation, but not to prolonged frost. White, pink or red five-lobed flowers grow in clusters year-round, peaking during the summer. The fruit is a long narrow pair of follicles, which splits open at maturity to release numerous downy seeds.

Nerium contains several toxic compounds, and it has historically been considered a poisonous plant. However, its bitterness renders it unpalatable to humans and most animals, so poisoning cases are rare and the general risk for human mortality is low. Ingestion of larger amounts may cause nausea, vomiting, excess salivation, abdominal pain, bloody diarrhea and irregular heart rhythm. Prolonged contact with sap may cause skin irritation, eye inflammation and dermatitis.

Nerium oleander es la única especie aceptada perteneciente al género Nerium, de la familia Apocynaceae. Es también conocida (entre otros nombres) como baladre, laurel de flor, rosa laurel, adelfa, trinitaria y en algunos casos como laurel romano. Nerium oleander fue descrita por Carlos Linneo y publicado en Species Plantarum 1: 209. 1753.[1]

Nerium contiene varios compuestos tóxicos, e históricamente se ha considerado una planta venenosa. Sin embargo, su amargura lo hace desagradable para los humanos y la mayoría de los animales, por lo que los casos de intoxicación son raros y el riesgo general de mortalidad humana es bajo. La ingestión de grandes cantidades puede causar náuseas, vómitos, exceso de salivación, dolor abdominal, diarrea con sangre y ritmo cardíaco irregular. El contacto prolongado con la savia puede causar irritación de la piel, inflamación de los ojos y dermatitis.

El nombre científico deriva del griego Nerion, origen del latín Nerium asociados a Nereo, dios del Mar y padre de las Nereidas. oleander: epíteto del latín Olea, ‘olivo’, por la semejanza de sus hojas y de dendron árbol.

Baladre deriva del catalán 'baladre', y este del latín 'verātrum' (eléboro) refiriéndose a un tipo de arbusto muy venenoso.[2][3]

Etimológicamente, Adelfa deriva del griego Dafne, el Laurel, a través del árabe دفلى, diflà.[4]

Son árboles o arbustos hasta de 3-4 m de altura, perennifolios.

Las hojas son linear-lanceoladas o estrechamente elípticas, opuestas o verticiladas en número de 3-4, de 0,5-2 por 10-40 cm, con los nervios muy marcados, pecioladas, glabras.

Las inflorescencias, en cimas corimbiformes paucifloras, terminales, están compuestas por flores, bracteadas y pediceladas, tienen el cáliz más o menos rojizo, con lóbulos lanceolados, agudos, con pelos glandulares en su cara interna, ligeramente soldado en su base, y la corola rosada, rara vez blanca, con una corona multífida y del mismo color. Los estambres, con filamentos rectos, son glabros, con anteras sagitadas, densamente pubescentes en el dorso, con un dientecillo en la parte inferior de su cara ventral que se une a la base del estigma. El gineceo, con ovario pubescente y sin nectarios en la base, es cónico, pentalobulado, unido a las anteras y con el estigma recubierto de una densa masa gelatinosa.

El fruto consiste en 2 folículos de 4-16 por 0,5-1 cm, fusiformes, más o menos pelosos que permanecen unidos hasta la dehiscencia, pardos y con semillas de 4-7 por 1-2 mm, cónicas, densamente pelosas, pardas, con vilano apical de 7-20 mm del mismo color.[5]

Originariamente se encontraba como planta nativa en una amplia zona que cubría las riberas de la cuenca del mar Mediterráneo hasta China, Vietnam. También crece en el Sahara cercana a pequeñas gueltas y zonas con flujos torrenciales.

Se ha difundido ampliamente por todas las zonas con clima propicio como planta ornamental. En Estados Unidos se ha introducido como cultivo ornamental, incluso urbano y en carreteras, también en restauración, como después del huracán de 1990, cuando se plantó en grandes cantidades en Texas. Crece solo en las regiones más cálidas de Norte América, hasta Virginia. Es frecuente en Argentina, Uruguay y Chile, usadas en jardines y como valla mediana de separación en autopistas, como en California, España, Australia. Se ha introducido en países tropicales como Colombia, Venezuela, Panamá y Honduras.

Posee heterósidos cardiotónicos (0,05 a 0,01 %): oleandrina, oleandrigenina, deacetiloleandrina, etc., cuyas geninas son entre otras la digitoxigenina y la gitoxigenina, flavonoides: rutósido, nicotiflorina, ácido ursólico, heterósidos cianogenéticos. Sustancias resinosas y glucósidos cardíacos como el neriosido.

El compuesto más característico del Nerium oleander es la oleandrina, un glucósido con estructura esteroide, muy similar química y farmacológicamente a la Ouabaina y Digoxina, dos cardiotónicos ampliamente utilizados en la insuficiencia cardiaca.

La acción de oleandrina es doble: la interacción con la bomba Na + y K + de las células del músculo del corazón y la acción directa en la regulación nerviosa del tono vagal del latido del corazón.[6]

Las células cancerosas tienen una necesidad absoluta del buen funcionamiento de la bomba del sistema enzima Na+ K+ para su reproducción, este sistema es el blanco de nuevos medicamentos contra el cáncer, tal como la oleandrina del 'Nerium oleander', y se han realizando pruebas en húmanos con resultados prometedores.[7]

Es una planta muy venenosa y totalmente desaconsejada para uso particular con acciones muy fuertes sobre el corazón en dosis pequeñas, por esta razón su uso debe estar sujeto a control médico.

En España la venta de esta planta al público para usos medicinales, así como la de sus preparados, está prohibida por razón de su toxicidad y su uso y comercialización se restringe a la elaboración de especialidades farmacéuticas, cepas homeopáticas y a la investigación. Del mismo modo, la Circular 06/2004 de la Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios del Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo aclara el ámbito de aplicación de la Orden SCO/190/2004 por la que se establece la lista de plantas cuya venta al público queda prohibida o restringida por razón de su toxicidad, especificando que la comercialización como planta ornamental no tiene ninguna limitación.

Las raíces y las hojas son ricas en sustancias digitálicas de mayor actividad que en la "dedalera" (Digitalis purpurea), tal el caso de como la oleandrina (C32H48O9), un glicósido cardíaco tóxico muy activo. La concentración de oleandrina es mayor en las raíces, seguida por la concentración en las hojas y en los tallos. La concentración de oleandrina en flores es significativamente menor.[8] Las flores requieren la visita de insectos para producir semillas; la polinización se produce por medio de un mecanismo de engaño. La llamativa corola ejerce una fuerte atracción en los polinizadores desde cierta distancia, pero las flores no secretan néctar y no ofrecen recompensa a sus visitantes. Por ello, reciben muy pocas visitas, como suele suceder con las especies cuyas flores no secretan néctar.[9][10] Los miedos hacia mieles contaminadas con néctar tóxico de adelfa son por tanto infundados.[11]

La intoxicación por Nerium oleander es parecida a la intoxicación digitálica, entre 4-12 horas.

En 1808 durante la Guerra de la Independencia Española, en un campamento los soldados de Napoleón asaron carne de cordero ensartando pinchos en estacas de Nerium oleander. De los 12 soldados, 8 murieron y los otros cuatro quedaron seriamente intoxicados.[12]

En Japón, fue la primera planta en florecer después de la explosión de la 1.ª bomba atómica sobre Hiroshima el 6 de agosto de 1945.

En los países cuyo clima es propicio, hay muchas llamadas de casos de intoxicación a los centros especializados, muchas circunstancias podrían provocar intoxicaciones por hojas o por flores; consumo de carnes ensartadas en ramas, inhalación de humos de maderas y hojas quemadas, y por mera confusión, ya que aparentemente las hojas de eucalipto son similares y estas se utilizan para infusiones, los niños accidentalmente también pueden ingerir las hojas, las flores o las semillas.

La savia del 'Nerium oleander' proveniente de raíces o tallos puede causar irritación o inflamación de la piel (dermatitis), irritaciones oculares graves, y reacciones alérgicas en general,[13] razón por la cual se requiere el uso de guantes impermeables protectores al podar la planta,[14] o trozarla para su erradicación.

Los primeros signos de intoxicación son gastrointestinales; náuseas y vómitos, con deposiciones diarreicas sanguinolentas. Le siguen signos neurológicos; vértigo, ataxia, midriasis, excitación nerviosa seguida de depresión, disnea, convulsiones tetaniformes. Y en seguida aparecen signos cardíacos; arritmia en aumento, aparece taquicardia, fibrilación auricular y bloqueo con parada cardíaca.

El tratamiento seguido es, clásicamente, el de la intoxicación digitálica. Cuando aparecen trastornos cardíacos hay que evitar el lavado de estómago. Se puede utilizar carbón activo, sobre todo en los casos de intoxicación reciente. En los casos más favorables (hombres jóvenes, poca cantidad ingerida), la inyección de atropina basta para combatir la bradicardia y permite, en algunas horas, la vuelta a un ritmo miocárdico normal. En los casos más graves, se recurre a la adrenalina, y a la desfibrilación por choque eléctrico entre otros.

Las especies animales generalmente afectadas por su ingestión son los caballos, las vacas, ovejas y cabras. La sintomatología que se les produce es de debilidad, sudor, irritación bucal y estomacal, vómitos (no en caballos), diarreas, gastroenteritis con hemorragias, temblor, extremidades frías, coma y a continuación la muerte puede ser repentina.

Esfinge de la Adelfa (Daphnis nerii) L.

Nerium oleander en Francisco Manuel Blanco, Flora de Filipinas [...], Gran edición [...], Atlas I, circa 1880

En zonas rurales se preparaba una loción para uso externo como parasiticida contra la sarna utilizando las hojas frescas de 'Nerium oleander' mezcladas con miel y aplicada como ungüento.[cita requerida]

Gracias a su espectacular floración es una especie muy cultivada en jardines y medianeras de carretera. Actualmente existen numerosas variedades de jardinería, caracterizadas por tener flores con un número variable de pétalos y diferentes coloraciones que incluyen el rojo, fucsia, carmín, rosa, blanco y, más recientemente, el salmón y el amarillo pálido. También existe una forma con hojas variegadas verde-amarillas y una subespecie enana.

A lo largo de la historia los 'Nerium oleander' se han empleado en múltiples provechos. Sus tallos se han utilizado en trabajos de cestería, de modo similar al esparto en la pleita y al mimbre en las mimbreras. La ceniza obtenida de quemar su madera se empleaba en la fabricación de pólvora. Para combatir la caspa y la caída del cabello se empleaban sus hojas maceradas. Además, sus tallos se colocaban entre las siembras de garbanzos, habichuelas y otras plantas leguminosas para protegerlas de ciertas enfermedades. Se ha utilizado también el polvo de tallos y hojas para fabricar matarratas.[15]

Las flores del 'Nerium oleander' son fuente de alimentación para polillas como la esfinge de la adelfa (Daphnis nerii). Sus orugas se alimentan de sus hojas sin ser afectadas por las potentes sustancias tóxicas. También se ve atacada por el chinche Spilostethus pandurus o el pulgón Aphis nerii.

Al tratarse de una planta de origen mediterráneo, es muy resistente a la sequía. Si se cultiva al aire libre y directamente sobre el suelo, excepto si se trata de un año muy seco, tiene bastante con el agua de la lluvia. Si, por el contrario, la cultivamos en maceta, la mejor manera de regar la planta es colocándole debajo un recipiente con agua y dejar que sea ella la que absorba la cantidad necesaria. En época vegetativa, primavera-verano, no deberíamos dejar que el suelo se secara completamente. En cambio, en invierno con un riego cada 15 días es suficiente. Para macetas de interiores es conveniente regar más abundante y pulverizar con cierta frecuencia.[16]

A partir de la especie silvestre se han conseguido en los viveros mediante hibridaciones diferentes variedades de uso en jardinería.

Nerium oleander es la única especie aceptada perteneciente al género Nerium, de la familia Apocynaceae. Es también conocida (entre otros nombres) como baladre, laurel de flor, rosa laurel, adelfa, trinitaria y en algunos casos como laurel romano. Nerium oleander fue descrita por Carlos Linneo y publicado en Species Plantarum 1: 209. 1753.

Nerium contiene varios compuestos tóxicos, e históricamente se ha considerado una planta venenosa. Sin embargo, su amargura lo hace desagradable para los humanos y la mayoría de los animales, por lo que los casos de intoxicación son raros y el riesgo general de mortalidad humana es bajo. La ingestión de grandes cantidades puede causar náuseas, vómitos, exceso de salivación, dolor abdominal, diarrea con sangre y ritmo cardíaco irregular. El contacto prolongado con la savia puede causar irritación de la piel, inflamación de los ojos y dermatitis.

Nerium oleander

Le Laurier-rose (Nerium oleander) est une espèce d'arbustes ou de petits arbres de la famille des Apocynacées. Cette espèce est présente sur les deux rives de la mer Méditerranée mais de façon plus éparse sur la rive nord. Il s'agit de la seule espèce du genre Nerium. Cette plante est parfois appelée Oléandre et plus rarement Rosage, Nérion ou Lauraine[1].

Arbre ornemental très répandu dans le pourtour méditerranéen, pratique car résistant à la sécheresse et à la taille, il forme haies et taillis dans les jardins des particuliers, dans les parcs ou à proximité des édifices publics.

Toutes les parties de la plante contiennent de l'oléandrine, un hétéroside cardiotonique, dont l'ingestion est fatale à faible dose ; en effet, quelques feuilles peuvent tuer un adulte[2],[3]. L'intoxication est très résistante aux traitements[4] et est sévère : troubles cardiaques graves, vomissements, douleurs abdominales, et mort par arrêt cardio-circulatoire[5],[6],[7]. D'autres glycosides y sont également présents en petite quantité.

Théophraste, au IIIe siècle av. J.-C., parle du laurier-rose dans son ouvrage Histoire des plantes, où, au Livre IX[8], pour mettre la couleur du laurier-rose en comparaison avec celle de la rose.

Nerium oleander est la seule espèce actuellement classée dans le genre Nerium . Il appartient (et donne son nom à) la petite tribu Nerieae de la sous-famille des Apocynoideae de la famille des Apocynaceae.

Les origines du nom taxonomique Nerium oleander , attribué pour la première fois par Linnaeus en 1753, sont contestées. Le nom de genre Nerium est la forme latinisée du nom grec ancien de la plante nẽrion (νήριον), qui est à son tour dérivé du grec pour l'eau, nẽros (νηρός), en raison de l'habitat naturel du laurier-rose le long des rivières et des ruisseaux.

Le mot laurier-rose apparaît dès le premier siècle de notre ère, lorsque le médecin grec Pedanius Dioscorides l'a cité comme l'un des termes utilisés par les Romains pour désigner la plante. Merriam-Webster pense que le mot est une corruption latine médiévale des noms latins tardifs de la plante : arodandrum ou lorandrum , ou plus vraisemblablement rhododendron (un autre nom grec ancien pour la plante), avec l'ajout d' olea en raison de la ressemblance superficielle à l' olivier ( Olea europea ) Une autre théorie avancée est que le laurier rose est la forme latinisée d'un nom composé grec : οllyo (ὀλλύω) « je tue » et le nom grec pour l'homme, aner , génitif andros (ἀνήρ, ἀνδρός), attribué à la toxicité du laurier rose pour les humains.

L'association étymologique du laurier - rose avec le laurier s'est poursuivie jusqu'à nos jours : en France, la plante est connue sous le nom de « laurier rose », tandis que le terme espagnol « Adelfa » est le descendant du nom grec ancien d'origine pour à la fois le laurier et le laurier-rose, daphné , qui passèrent par la suite dans l' usage arabe et de là en Espagne.[9]

L'ancienne ville de Volubilis au Maroc peut avoir pris son nom du nom berbère alili ou oualilt pour la fleur.[10]

Le laurier-rose est un arbuste d'environ 2 m de hauteur mais il peut mesurer plus de 4 m de haut si on le forme en arbre. Les feuilles sont persistantes, plutôt coriaces, allongées et fusiformes, les feuilles du laurier-rose sont verticillées (c’est-à-dire insérées au même niveau, par groupe de 3, en cercle autour des tiges) ou opposées sur les rameaux. Longues de 5 à 20 cm, elles sont coriaces, d’un vert foncé brillant sur le dessus et de couleur vert pâle et terne sur le dessous[1].

Les fleurs sont groupées en cymes terminales sur les rameaux et en forme de trompette, les fleurs de laurier-rose se composent de 5 pétales. Elles peuvent être simples (1x5 pétales), doubles (2x5 pétales) ou triples (3x5 pétales). Suivant la variété, leur couleur varie du blanc, jaune, orange, saumon, rouge à diverses nuances de rose. Elles dégagent parfois un agréable parfum. La floraison a lieu de la fin du printemps (mai-juin) à l’automne (septembre-octobre)[1].

Selon les cultivars les fleurs peuvent comporter de une à quatre couronnes de pétales.

Les cultivars ci-dessous (classés du plus rustique au moins rustique) présentent une résistance au froid allant jusqu'en zone de rusticité 8a (-9 à -12 °C) :

Les variétés à fleurs doubles demandent plus de chaleur pour bien fleurir. Il existe plus de 160 variétés.[réf. nécessaire]

Le Sphinx du laurier-rose (Daphnis nerii), papillon de nuit (hétérocère), et le Spilostethus pandurus, une punaise, se nourrissent de Laurier-rose. Le puceron du laurier rose Aphis nerii se nourrit notamment de la sève du Laurier-rose[11].

L'origine du laurier-rose est le Bassin méditerranéen, en Asie mineure, en Inde et au Japon[12].

L'espèce est évaluée comme non préoccupante aux échelons mondial, européen et français[13]. Toutefois elle est considérée comme Vulnérable (VU) en Corse.

Au Sud de l'Europe, les lauriers-roses sont plantés en pleine terre, ou dans un grand pot, pour la décoration d'une terrasse. Dans les villes des régions bordant la Méditerranée, ils sont parfois utilisés comme arbres d'alignement dans les rues. Ils bordent les corniches et les pistes cyclables. Ils s’accommodent des sols sableux[14], et s'adaptent à des sols variés. Ils supportent la chaleur (z.9)[15].

En France, on le range souvent dans la liste des plantes dites d'orangerie (jasmin, bougainvillée, figuier, citrus...) que l'on cultive à l'abri des forts gels, en véranda sauf dans le pourtour méditerranéen.

En Suisse romande, on les cultive en pots qu'on sort au printemps après les saint-de-glace et remet à l'abri en automne pour les protéger du gel.

Les lauriers-roses sont avant tout une plante méditerranéenne et ont impérativement besoin d'une situation ensoleillée et chaude pour prospérer, dans un sol bien drainé et enrichi avec des apports d'engrais riche en potasse (type 20-20-20)[16].

Partout où il y a risque de gel, les lauriers-roses devront être plantés en bac, car il sera nécessaire de les rentrer si les températures approchent de 0 °C, car ils gèlent irrémédiablement à environ -5 °C (sauf pour les variétés rustiques indiquées ci-dessus). Il faut alors les placer au frais, entre 5 et 10 °C, dans un endroit assez lumineux, avec des arrosages réduits et pas d'engrais.

La plantation se fait d'octobre à avril. La taille doit respecter la forme de l'arbuste et consiste à rabattre de moitié les rameaux qui se développent avec trop de vigueur. En cas de gel, mais pas trop rude, il ne faut pas hésiter pour tenter de les sauver, à rabattre très fortement la touffe au ras du sol. L'arbuste repartira peut-être du pied. En été, surtout pour les lauriers en bac, il est nécessaire d'arroser copieusement et de faire des apports d'engrais régulièrement pour entretenir une floraison abondante. Le jaunissement puis la chute des feuilles du bas signale un manque d'engrais (riche en potassium), lequel devra cependant être apporté seulement en période de croissance de mars à septembre[16].

Le bouturage est facile en mettant des branches directement dans des pots avec une terre sableuse. Les professionnels ne bouturent pas en bouteille[17].

Les lauriers-roses se multiplient assez facilement en prélevant des boutures herbacées en mars-avril, à faire raciner dans l'eau avant de les planter dans une terre riche et légère. Le marcottage est aussi réalisable sur les branches retombantes, à séparer du pied à 2 ans[16].

Le laurier-rose est une plante toxique dont toutes les parties sont très toxiques (présence d'hétérosides cardiotoxiques)[18],[19].

Le composé le plus caractéristique du laurier-rose est l'oléandrine, un hétéroside à structure stéroïdique, qui ressemble beaucoup du point de vue chimique et pharmacologique à l'ouabaïne et à la digoxine, deux cardiotoniques très utilisés en cas d'insuffisance cardiaque.

L'action de l'oléandrine est double : interaction avec la pompe à Na+ et K+ des cellules du muscle cardiaque et action directe sur le tonus vagal donc la régulation nerveuse des battements cardiaques[20]. L'absorption des feuilles, fleurs ou fruits provoque d'abord des troubles digestifs, puis altère le fonctionnement cardiaque.

Les cellules cancéreuses ont absolument besoin du bon fonctionnement du système enzymatique pompe à Na+ K+ pour se reproduire, ce système est donc la cible de nouveaux médicaments anticancéreux comme l'oléandrine du laurier-rose, des essais sur l'homme ont déjà lieu avec des résultats prometteurs[21].

L'ingestion d'une simple feuille peut être mortelle pour un adulte et un enfant, en raison des troubles souvent provoqués[22],[23],[16].

D'après des textes du moyen-âge, l'utilisation de ses branches comme broche pourrait rendre la viande mortellement toxique.

Aucuns sont mauvais qui font une broche (...) de ceste herbe ou arbre de oléandre. (...) Les chairs là rousties font ceux qui en mangent mourir[24].

En 1808, durant la campagne d'Espagne, lors d'un bivouac, des soldats de Napoléon font rôtir des agneaux sur des broches de laurier-rose. Sur les 12 soldats, 8 meurent, les 4 autres sont gravement intoxiqués[25],[15],[26].

Les animaux herbivores peuvent également s'empoisonner avec les feuilles de laurier-rose. Les feuilles sèches sont généralement en cause car la feuille fraîche est plutôt repoussante, sauf si l'animal est affamé. Une quantité de 30 à 60 g de feuilles fraîches serait potentiellement mortelle pour un bovin adulte, tandis que 4 à 8 g de feuilles suffiraient à provoquer la mort d'un petit ruminant (un mouton par exemple). L'eau dans laquelle ont macéré des feuilles ou des branches de laurier-rose est également toxique pour les animaux[20]. En Afrique du Nord, il faut se méfier de l'eau des ruisseaux dans laquelle ont trempé les racines de lauriers-roses[25]. Même la fumée de la combustion de ses branches est nocive[15].

Nerium oleander

Le Laurier-rose (Nerium oleander) est une espèce d'arbustes ou de petits arbres de la famille des Apocynacées. Cette espèce est présente sur les deux rives de la mer Méditerranée mais de façon plus éparse sur la rive nord. Il s'agit de la seule espèce du genre Nerium. Cette plante est parfois appelée Oléandre et plus rarement Rosage, Nérion ou Lauraine.

Arbre ornemental très répandu dans le pourtour méditerranéen, pratique car résistant à la sécheresse et à la taille, il forme haies et taillis dans les jardins des particuliers, dans les parcs ou à proximité des édifices publics.

Toutes les parties de la plante contiennent de l'oléandrine, un hétéroside cardiotonique, dont l'ingestion est fatale à faible dose ; en effet, quelques feuilles peuvent tuer un adulte,. L'intoxication est très résistante aux traitements et est sévère : troubles cardiaques graves, vomissements, douleurs abdominales, et mort par arrêt cardio-circulatoire,,. D'autres glycosides y sont également présents en petite quantité.

L'oleandro (Nerium oleander L., 1753) è un arbusto sempreverde appartenente alla famiglia delle Apocynaceae, unica specie del genere Nerium[1]. È forse originario dell'Asia ma è naturalizzato e spontaneo nelle regioni mediterranee e diffusamente coltivato a scopo ornamentale.

L'oleandro ha un portamento arbustivo, con fusti generalmente poco ramificati che partono dalla ceppaia, dapprima eretti, poi arcuati verso l'esterno. I rami giovani sono verdi e glabri. I fusti e i rami vecchi hanno una corteccia di colore grigiastro.

Le foglie, velenose come i fusti, sono glabre e coriacee, disposte a verticilli di 2-3, brevemente picciolate, con margine intero e nervatura centrale robusta e prominente. La lamina è lanceolata, acuta all'apice, larga 1–2 cm e lunga 10–14 cm.

I fiori sono grandi e vistosi, a simmetria raggiata, disposti in cime terminali. Il calice è diviso in cinque lobi lanceolati, di colore roseo o bianco nelle forme spontanee. La corolla è tubulosa e poi suddivisa in 5 lobi, di colore variabile dal bianco al rosa e al rosso carminio. Le varietà coltivate sono a fiore doppio e sono quasi tutte profumate. L'androceo è formato da 5 stami, con filamenti saldati al tubo corollino. L'ovario è supero, formato da due carpelli pluriovulari. La fioritura è abbondante e scalare, ha inizio nei mesi di aprile o maggio e si protrae per tutta l'estate fino all'autunno.

Il frutto è un follicolo fusiforme, stretto e allungato, lungo 10–15 cm. A maturità si apre longitudinalmente lasciando fuoriuscire i semi. Il seme ha dimensione variabile dai 3 ai 5 mm di lunghezza e circa 1 mm di diametro ed è sormontato da una peluria disposta ad ombrello (impropriamente detta pappo) che permette al seme di essere trasportato dal vento anche per lunghe distanze.

L'oleandro è una specie termofila ed eliofila, abbastanza rustica. Trae vantaggio dall'umidità del terreno rispondendo con uno spiccato rigoglio vegetativo, tuttavia ha caratteri xerofitici dovuti alla modificazione degli stomi fogliari che gli permettono di resistere a lunghi periodi di siccità. Teme il freddo, pertanto in ambienti freddi fuori dalla sua zona fitoclimatica deve essere posto in luoghi riparati e soleggiati. Viene coltivato in tutta Italia a scopo ornamentale e spesso è usato lungo le strade perché non richiede particolari cure colturali[2].

Nonostante il portamento cespuglioso per natura, può essere allevato ad albero per realizzare viali alberati suggestivi per la fioritura abbondante, lunga e variegata nei colori. In questo caso richiede frequenti interventi di spollonatura per rimuovere i polloni basali emessi dalla ceppaia.

L'oleandro ha un areale piuttosto vasto che si estende nella fascia temperata calda dal Giappone al bacino del Mediterraneo. In Italia vegeta spontaneamente nella zona fitoclimatica del Lauretum presso i litorali, inoltrandosi all'interno fino ai 1000 metri d'altitudine lungo i corsi d'acqua. In effetti si tratta di un elemento comune e inconfondibile della vegetazione riparia degli ambienti mediterranei, quasi sempre associato ad altre specie riparie quali l'ontano, la tamerice, l'agnocasto. S'insedia sia sui suoli sabbiosi alla foce dei fiumi o lungo la loro riva, sia sui greti sassosi, formando spesso una fitta vegetazione.

L'associazione vegetale riparia con una marcata presenza dell'oleandro è una particolare cenosi vegetale che prende il nome di macchia ad oleandro e agnocasto, di estensione limitata. Si tratta di una naturale prosecuzione dell'oleo-ceratonion, dal momento che le due cenosi gradano l'una verso l'altra con associazioni intermedie che vedono contemporaneamente la presenza dell'oleandro e di elementi tipici della macchia termoxerofila (lentisco, carrubo, mirto, ecc.). Un caso singolare, forse unico in natura, si rinviene nella Gola di Gorropu fra il Supramonte di Orgosolo e quello di Urzulei in Sardegna: in questo caso la macchia ad oleandro e agnocasto si inoltra fino ai 1000 metri, confinando con la lecceta primaria.

Tra le avversità tipiche di questa pianta si annovera la rogna dell'oleandro, la quale viene curata attraverso la potatura della parte malata e la successiva somministrazione di fungicidi rameici.

L'oleandro è una delle piante più tossiche che si conoscano. Tutta la pianta (foglie, corteccia, semi) è tossica per qualsiasi specie animale. Se ingerita porta a:

Responsabile di questa estrema tossicità è, insieme agli alcaloidi, l'oleandrina, un glicoside cardiotossico (con struttura simile alla ouabaina) e inibitore della pompa sodio-potassio a livello di membrana cellulare.

L'oleandro contiene una serie di altri principi tossici, che si conservano anche dopo l'essiccamento.

Altre sostanze che si trovano in natura, con lo stesso meccanismo di azione, sono la digossina, la digitale purpurea ed il giglio della valle.

Le specie animali più colpite sono gli equini, i bovini e i piccoli carnivori. Nel cavallo abbiamo anche la comparsa di gravi e profonde lesioni a livello della mucosa orale. La morte sopraggiunge per collasso cardio-respiratorio solo nel caso in cui se ne ingeriscano grandi quantità.

Le sue proprietà tossiche sono state usate come "arma" per l'omicidio descritto nel film White Oleander.

Inoltre la storia ci racconta che diversi soldati delle truppe napoleoniche morirono per avvelenamento dopo aver usato rami di oleandro come spiedi nella cottura della carne alla brace, durante le campagne militari in Italia.

L'oleandro (Nerium oleander L., 1753) è un arbusto sempreverde appartenente alla famiglia delle Apocynaceae, unica specie del genere Nerium. È forse originario dell'Asia ma è naturalizzato e spontaneo nelle regioni mediterranee e diffusamente coltivato a scopo ornamentale.

O oleandro (Nerium oleander), também conhecido como loendro, loandro, aloendro, loandro-da-índia, alandro, loureiro-rosa, adelfa, espirradeira, cevadilha espirradeira ou flor-de-são-josé, é uma planta ornamental da família Apocynaceae, relativamente comum (inclusive em calçadas e vias públicas), porém extremamente tóxica.

É um arbusto grande, podendo ter por volta de 3 a 5 m de altura (embora haja uma variedade menor). Suas flores podem ser brancas, róseas ou vermelhas. As folhas são estreitas e longas, às vezes descritas como em formato de ponta de lança. É uma planta pouco exigente em no que respeita a temperatura e humidade.

Toda a planta é tóxica. Tem como princípios ativos a oleandrina e a neriantina, substâncias extraordinariamente tóxicas. Basta que seja ingerida uma folha para matar um homem de 80 kg – embora muitas vezes a ocorrência de vómitos evite o desfecho fatal. Em contato com a pele, a seiva também apresenta riscos, e é aconselhável o uso de luvas no manuseio.

Os sintomas da intoxicação, que podem não demorar ou aparecer várias horas depois da ingestão (ou contato com a seiva), incluem dores abdominais, pulsação acelerada (taquicardia), ansiedade, gastrite, diarreia, vertigem, sonolência, dispnéia, irritação da boca, náusea, vômitos, coma e morte.

Está registrado pelo menos um caso de intoxicação por ingestão de caracóis alimentados com folhas desta planta[1], devido à acumulação de toxinas ao longo da cadeia alimentar. Além disso, as propriedades tóxicas do oleando têm sido usadas como instrumento de suicídio desde a antiguidade.[2]

O oleandro é originário do norte da África, do leste do Mediterrâneo e do sul da Ásia. É muito comum em Portugal e no Brasil, quer espontâneo, quer cultivado. Pelo fato de a divisão dos seus caules ocorrer muitas vezes de forma simétrica, em formato de Y, costuma ser utilizado (o que não é recomendável) para confeccionar forquilhas de estilingues, apesar da madeira pouco resistente.

O oleandro (Nerium oleander), também conhecido como loendro, loandro, aloendro, loandro-da-índia, alandro, loureiro-rosa, adelfa, espirradeira, cevadilha espirradeira ou flor-de-são-josé, é uma planta ornamental da família Apocynaceae, relativamente comum (inclusive em calçadas e vias públicas), porém extremamente tóxica.

É um arbusto grande, podendo ter por volta de 3 a 5 m de altura (embora haja uma variedade menor). Suas flores podem ser brancas, róseas ou vermelhas. As folhas são estreitas e longas, às vezes descritas como em formato de ponta de lança. É uma planta pouco exigente em no que respeita a temperatura e humidade.

협죽도(夾竹桃, 문화어: 류선화, 학명: Nerium indicum)는 협죽도과에 속하는 넓은잎 늘푸른떨기나무이다. 인도 원산이며, 한국에서는 제주도에 자생한다.[1] 유도화(柳桃花)라고도 부른다.

1753년 린네가 《식물의 종》에서 Nerium oleander로 등재하였다.[2][3] 속명 네리움(Nerium)은 고대 그리스어 네리온(νἠριον)을 라틴어화 한 것으로 물가에서 잘 자란다는 의미를 갖고 있고, 종명 올리엔더(oleander)의 명명에는 두 가지 설이 있는데, 올리브 나무와 비슷한 모양새라서 그렇게 붙였다는 것과[4] 독성을 나타내기 위해 그리스어로 죽인다는 뜻을 지닌 올리오(ολλύω)와 사람을 뜻하는 안드로스(άνδρος)를 합쳐 만들었다는 설이 있다.[5] 필립 밀러가 1768년 Nerium Indicum으로 학명을 다시 등재하였다.[6]

높이는 2-4m 정도이며 꽃이 아름답다.[7] 전체 수형은 부채꼴 모양이다.[8] 잎은 피침형이며 두껍고 질기다.[7] 길이 7~15센티미터, 너비 8~20밀리미터쯤 되며 돌려난다.[8] 꽃은 화려하며 장미를 많이 닮았다. 여러 변종 가운데 붉은색 꽃이 피는 변종과 흰색 꽃이 피는 변종이 가장 잘 알려져 있다.[7] 지름이 4~5센티미터쯤 되며 꽃받침은 5개로 갈라진다.[8]

지중해 연안과 아프리카 북부의 모리타니, 모로코, 포르투갈 등에 자생지가 있으며 자생지역은 아라비아반도와 남아시아를 거쳐 중국 남부의 윈난성까지 분포하고 있다.[9][10][11][12]

대개 기후가 따뜻한 지역에서는 실외에 심고, 온대지역에서는 관상용으로 많이 기른다. 줄기를 잘라 물병에 꽂아두면 몇 주 안에 뿌리가 나오는데, 보통 꺾꽂이법을 이용해 재배한다.[7] 오염에 내성이 강하고 이식이 쉽다.[8]

아주 미량이라도 치사율이 높기 때문에 독화살, 사약의 용도로 사용하기도 했다.[13] 강한 독성이 있으나 껍질과 뿌리는 약용으로 사용한다.[7] 생약으로는 잎을 쓰며 협죽도엽이라고 한다. 강심제와 이뇨제로 쓴다.[1]

협죽도는 독성이 있다. 협죽도의 독성분은 스테로이드를 비당체(aglycon)로 삼는 배당체 가운데 심근에 작용하여 울혈성 심부전에 효과가 있는 강심배당체(cardiac glycosides)이며 여러 종류의 강심배당체가 함유되어 있다. 그 가운데 가장 많은 것은 올레안드린이다.[14] 올레안드린의 반수 치사량은 300 ug/kg이다.[15] 독성분은 주로 잎에 분포하며 꽃이 필 때 최고조에 이른다.[16] 소가 잎을 뜯어 먹을 경우 치사량은 마른 잎을 기준으로 50mg/kg 이라고 한다.[14]

이 외에도 협죽도에 포함된 글리코사이드 역시 민감한 사람은 중독 증세를 보일 수 있다.[17]

미디어에서는 종종 협죽도의 독성에 대한 뉴스를 보도한다. 협죽도가 가로수로 심어져 있는 것을 우려하는 보도가 있었다.[18][19][20]이러한 보도로 지방자치단체에서는 가로수나 조경수로 심어진 협죽도를 배어내는 경우도 있다.[21]

한편, 협죽도의 독성을 보도할 때 청산가리 독성의 6천배에 달한다고 보도하는 경우도 있는데[21][22], 청산가리의 반수 치사량은 설치류가 입을 통해 섭취할 때 5 - 10 mg/kg 이어서[23] 6천배라는 표현은 매우 과장된 것이다.[24]