mk

имиња во трошки

The genus Grus is comprised of ten crane species which is divided into four subgroups. Whooping cranes belong to the subgroup "the Group of Five" which also includes Eurasian cranes (Grus grus), hooded cranes (G. monacha), black-necked cranes (G. nigricollis) and red-crowned cranes (G. japonensis).

The key form of communication for whooping cranes is vocal communication. Many calls have been identified for this species including: contact calls, stress calls, distress calls, food-begging calls, flight-intention calls, alarm calls, hissing, flight calls, guard calls, location calls, precopulation calls, unison calls, and nesting calls. Territory defense is linked with the unison and guard calls. Unison calls are also important in pair formation. The calls of whooping cranes are important as they serve in deterring predators, warnings of attack, protecting and caring for the young, and locating other individuals within the species. Like all birds, whooping cranes perceive their environment through visual, auditory, tactile, and chemical stimuli.

Communication Channels: visual ; acoustic

Other Communication Modes: duets

Perception Channels: visual ; tactile ; acoustic ; chemical

Whooping cranes have been the center of many conservation projects. Even though they are still endangered, they have recovered from levels of near extinction in the 1940's to 1950's. Whooping cranes had a total population of 21 in the winter of 1954 and had approximately 260 individuals in 2009. There are a number of ways in which recovery of whooping cranes has been promoted. This includes protection through laws such as, the United States Migratory Bird Act. There are also intense captive breeding and re-introduction efforts. In some cases eggs produced by captive pairs are cared for by human caretakers dressed as whooping cranes, also known as costume-rearing. These re-introduced birds have experienced problems with migration, and it is presumed that juvenile birds learn migration routes from their parents. To help these birds, small, white planes are used as "parent" birds that guide the juveniles on their first journey to their wintering grounds. These methods have had mixed success, but the population is increasing overall.

US Migratory Bird Act: protected

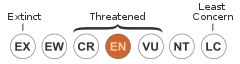

US Federal List: endangered

CITES: appendix i

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: endangered

There are no adverse effects of whooping cranes on humans.

Whooping cranes serve as an important model for the positive effects of wildlife conservation and management. It is a valuable symbol of conservation and international co-operation between governments for many people. Thousands of people visit the wintering site, Aransas National Wildlife Refuge, each year in order to see whooping cranes.

Positive Impacts: ecotourism

Whooping cranes are both predators and prey to a number of species. Because there are so few of them, they probably can't serve as the main prey to another species. Whooping cranes do play host to some parasites, and Coccidia parasites in particular. These have been found in both captive and wild whooping cranes and are transmitted through feces. These parasites include Eimeria gruis and E. reichenowi. Coccidiosis is less likely to occur in wild populations due to the large territory and small brood size of whooping cranes.

Commensal/Parasitic Species:

Whooping cranes are omnivorous and eat a variety of plant and animal material both on the ground and in water. The primary wintering foods are blue crabs (Callinectes sapidus) and wolfberry fruits (Lycium carolinianum). Other wintering foods include: clams, acorns, snails, grasshoppers, mice, voles and, snakes. Among foods they eat in winter, blue crabs provide the highest crude protein value and wolfberries have the highest metabolic energy and lipid content. On migratory stopovers through the central United States and Saskatchewan, whooping cranes feed on plant tubers and waste grains in agricultural fields. While on breeding grounds their diet consists of minnows, insects, frogs, snakes, mice, berries, crayfish, clams and snails.

Animal Foods: mammals; amphibians; reptiles; fish; insects; mollusks; terrestrial worms; aquatic crustaceans

Plant Foods: roots and tubers; seeds, grains, and nuts; fruit

Primary Diet: omnivore

Grus americana is a native migratory bird species within the Nearctic region. The historical breeding range extends throughout the central United States and Canada and also used to include parts of north central Mexico. Few wild populations occur today. One population breeds within the Wood Buffalo National Park in the Northwest Territories of Canada and overwinters along the Gulf Coast in the Aransas National Wildlife Refuge of Texas. A second, minute population spends the summer in Idaho, Wyoming and Montana, and migrates to their wintering grounds in the Rio Grande Valley of New Mexico. A third introduced, non-migratory population resides in the Kissimmee Prairie, Florida. When the Wood Buffalo and Rocky Mountain populations migrate, they stop over in the United States and Canada, in North Dakota, South Dakota, Kansas, Nebraska, Oklahoma, Montana, and Saskatchewan.

Biogeographic Regions: nearctic (Native )

Whooping crane habitat, especially for nesting, consists of open areas close to large amounts of water and vegetation. The open area is especially important to visually detect possible predators. Whooping cranes nest in wetland and marsh areas or close to shallow ponds or lakes. Bulrush (Scirpus validus) marshes and diatom ponds are common and bogs are avoided. The habitats chosen typically include willow, sedge meadows, mudflats, and bulrush and cattail (Typha latifolia) marshes. These habitat types not only provide protection for predators but also provide a variety of food opportunities. During migration, whooping cranes seek similar habitats in wetlands, submerged sandbars and agricultural fields. In the winter, wet habitats are also sought out in the form of brackish bays and coastal marshes. Grus americana prefers marshes with a typical pH range of 7.6 to 8.3.

The elevation varies considerably due to the wintering and breeding ranges for whooping cranes. The Aransas National Wildlife Refuge on the Gulf Coast of Mexico is at low elevations between 0 to 10 m. The northern breeding grounds in the Wood Buffalo National Park can reach elevations of up to 945 m.

Range elevation: 0 to 945 m.

Habitat Regions: temperate ; terrestrial

Terrestrial Biomes: savanna or grassland

Aquatic Biomes: lakes and ponds; coastal ; brackish water

Wetlands: marsh ; swamp

Other Habitat Features: agricultural

The estimated longevity of wild whooping cranes is 22 to over 30 years. In captivity, the birds are expected to live up to 35 to 40 years old. The mortality of whooping cranes in their first year is approximately 27%. The survival rate of females for their first year is 55% the survival rate of males. Diseases, such as avian tuberculosis and avian cholera, are possible mortality causes for whooping cranes. A cause of mortality of some captive chicks has been intestinal coccidia parasites. Drought during the breeding season results in greater mortality of the young, since they have to travel farther for food resources and are at risk of attack by terrestrial predators.

Typical lifespan

Status: wild: 22 to 30 years.

Typical lifespan

Status: captivity: 35 to 40 years.

Adult whooping cranes are large, long-legged birds with long necks that measure 130 to 160 cm in length, and feature a wingspan of 200 to 230 cm. They are primarily white in color. Their primary wing feathers and long legs are black, while their toes are grayish-rose in color. The crown, lores, and malar areas are bare skin that varies in color from bright red to black. The bare skin is covered in short, black bristles that are the most dense around the edges of bare skin. They feature yellow eyes and a bill that is pinkish at the base, but mostly gray or olive in color. Both sexes resemble each other, however, the male whooping crane weighs more. Adult males and adult females weigh an average of 7.3 kg and 6.4 kg respectively. Young whooping crane chicks are cinnamon or brown in color along the back and a dull gray or brown on the underbelly. Juvenile whooping cranes have feather-covered heads and white plumage which is blotched cinnamon or brown. The area of the crown which becomes bare skin has short feathers.

Closely related sandhill cranes are gray and smaller than whooping cranes but they may appear white, especially in the sun. In flight, wood storks resemble whooping cranes, but they feature black secondary as well as primary feathers, yellow feet, and a short neck that is bare, dark skin.

Range mass: 4.5 to 8.5 kg.

Range length: 130 to 160 cm.

Average length: 150 cm.

Range wingspan: 200 to 230 cm.

Other Physical Features: endothermic ; homoiothermic; bilateral symmetry

Sexual Dimorphism: sexes alike; male larger

Whooping cranes are subject to predation from both terrestrial and aerial predators Some common terrestrial predators include black bear, wolverines, gray wolves, red foxes, lynx, bobcats, coyotes, and raccoons. Bald eagles, northern ravens, and golden eagles are all aerial predators of cranes. Golden eagles have been reported to attack whooping cranes in the air and are a significant threat during migration. Whooping cranes fly at very high altitudes during migration, which may be a strategy to avoid these fatal aerial attacks.

Whooping cranes are the most vulnerable in the first year and especially up until fledging. Dry years make the young particularly vulnerable as the nests are easily accessible to terrestrial predators. They have a number of strategies for preventing attacks such as alarm calls or a distraction display for large predators. The most common display is a slow walk strut, with the body turned sideways to the predator and the feet lifted high. This emphasizes the crane's large size and may deter an attack. If the predator persists, a whooping crane lowers its bill to the ground and releases a low growl. As a final warning before a physical attack, a crane will face the predator, and spread and droop its wings while extending its neck. When a large predator nears the nest, the incubating parent may leave the nest to lure the predator away by dragging its wing in a distraction display.

Known Predators:

Whooping cranes are monogamous and form pairs around two or three years old. A pair bond develops through a variety of courtship behaviors including unison walks, unison calls, and courtship dances. Courtship usually begins with dancing, which starts with bowing, hopping, and wing flapping by one, and then both individuals. Each crane repeatedly leaps into the air on stiff legs, which continues until both individuals leap a few times in sync with each other. During the courtship dance the male may also jump over the female as she bows her head toward her body. Calling in unison is also important in pair maintenance and involves a duet between the female and male. The male has a lower call and positions the head straight up and behind vertical while the female is completely vertical or forward of vertical. Once one of the individuals begins the call the other joins in.

Once paired, whooping cranes breed seasonally and start nesting at approximately four years of age. Prior to copulation either individual begins walking slowly, with their bill pointed up, and neck forward and fully extended. This individual releases a low growl and the other individual walks with the same style behind the first and calling with its bill up toward the sky. Copulation commonly occurs at daybreak, however it can occur during any time in the day. Nesting pairs generally mate for life, but one will find a new mate following the death of the other.

Mating System: monogamous

Whooping cranes reproduce once a year from late April to May. Males and females participate in building a flat, ground nest usually on a mound of vegetation surrounded by water. In periods of drought, nesting sites can become no longer suitable for use. Typically two eggs are laid and the incubation period is 30 to 35 days. The sex ratio is nearly equal between the number of males and females hatched. The abandonment or loss of a nest is rare but breeding pairs can re-nest if either occurs within the first fifteen days of incubation. Fledging occurs between 80 to 100 days but the young remain with their parents until they reach independence at 9 months of age. Parents continue to feed and care for the fledgelings. Sexual maturity is reached between 4 and 5 years old.

Breeding interval: Whooping cranes breed once a year.

Breeding season: Whooping cranes breed from late April to May.

Range eggs per season: 1 to 3.

Range time to hatching: 30 to 35 days.

Average time to hatching: 30 days.

Range fledging age: 80 to 100 days.

Average time to independence: 9 months.

Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female): 4 to 5 years.

Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male): 4 to 5 years.

Key Reproductive Features: iteroparous ; seasonal breeding ; gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); sexual ; oviparous

Average birth mass: 212 g.

Average eggs per season: 2.

Both the male and female share equally in incubation responsibilities. The individual not incubating guards the nest from predators. Once hatched, young chicks are brooded by their parents at night or during bad weather. When a chick displays hunger, referred to as food begging, the parents provide them with food. The female provides the food more often than the male. The adult grasps the food in its bill and the chicks peck at the food. Food choices are initially worms and insects and grow is size as the chick develops. The young gradually start to feed independently. Food begging can be seen in young birds six to nine months old. The majority of juvenile birds completely leave their parents at the end of spring migration the following year.

Parental Investment: precocial ; male parental care ; female parental care ; pre-fertilization (Provisioning, Protecting: Female); pre-hatching/birth (Protecting: Male, Female); pre-weaning/fledging (Provisioning: Female, Protecting: Male); pre-independence (Provisioning: Male, Female, Protecting: Male, Female); post-independence association with parents; extended period of juvenile learning

Garan Amerika (Grus americana) a zo un evn hirc'harek.

La grua cridanera[1] (Grus americana) és un ocell de la família dels grúids (Gruidae) que habita pantans i praderies humides. Extint de la major part de la seva antiga àrea de distribució, actualment cria al nord d'Alberta, i passa l'hivern a Texas i Florida.

La grua cridanera (Grus americana) és un ocell de la família dels grúids (Gruidae) que habita pantans i praderies humides. Extint de la major part de la seva antiga àrea de distribució, actualment cria al nord d'Alberta, i passa l'hivern a Texas i Florida.

Aderyn a rhywogaeth o adar yw Garan ubanol (sy'n enw gwrywaidd; enw lluosog: garanod ubanol) a adnabyddir hefyd gyda'i enw gwyddonol Grus americana; yr enw Saesneg arno yw Whooping crane. Mae'n perthyn i deulu'r garanod (Lladin: Gruidae) sydd yn urdd y Gruiformes.[1]

Talfyrir yr enw Lladin yn aml yn G. americana, sef enw'r rhywogaeth.[2] Mae'r rhywogaeth hon i'w chanfod yng Ngogledd America.

Mae'r garan ubanol yn perthyn i deulu'r garanod (Lladin: Gruidae). Dyma rai o aelodau eraill y teulu:

Rhestr Wicidata:

rhywogaeth enw tacson delwedd Brolga Grus rubicunda Bugeranus carunculatus Bugeranus carunculatus Garan coronog Balearica pavonina Garan coronog y De Balearica regulorum Garan cycyllog Grus monacha Garan glas Anthropoides paradiseus Garan gyddfddu Grus nigricollis Garan Manshwria Grus japonensis Garan mursenaidd Anthropoides virgo Garan saras Grus antigone Garan twyni Grus canadensis Garan ubanol Grus americana Grus grus Grus grusAderyn a rhywogaeth o adar yw Garan ubanol (sy'n enw gwrywaidd; enw lluosog: garanod ubanol) a adnabyddir hefyd gyda'i enw gwyddonol Grus americana; yr enw Saesneg arno yw Whooping crane. Mae'n perthyn i deulu'r garanod (Lladin: Gruidae) sydd yn urdd y Gruiformes.

Talfyrir yr enw Lladin yn aml yn G. americana, sef enw'r rhywogaeth. Mae'r rhywogaeth hon i'w chanfod yng Ngogledd America.

Jeřáb americký (Grus americana) nebo také jeřáb bělohřbetý je ohrožený druh jeřábovitého ptáka žijícho v Severní Americe.

Dosahuje výšky 150 cm a rozpětí křídel 230 cm, váží okolo 7 kg. Mladí jedinci mají hnědé peří, dospělci jsou bílí s rudohnědou hlavou a černýma nohama a konci letek. Pohlavní dospělosti dosahuje pták ve čtyřech letech, dožívá se 22 až 24 let. Živí se korýši, měkkýši, obojživelníky, rybami i rostlinnou stravou. Ozývá se charakteristickým daleko slyšitelným troubením, v období tokání předvádějí samci efektní tanec.

Jeřáb americký žil do začátku 20. století jako tažný druh v oblasti středozápadních prérií. Intenzivní lov i ztráta původních stanovišť vedly k prudkému poklesu stavů, posledním hnízdištěm zůstal Národní park Wood Buffalo v severní Kanadě. V roce 1941 zbylo pouhých patnáct kusů, poté Národní Audubonova společnost zahájila program na záchranu tohoto druhu, který zahrnoval umělou inkubaci vajec i navádění ptáků na zimoviště pomocí ultralehkých letadel. Záchrana druhu se zdařila a počátku 21. století bylo napočítáno 400 jeřábů amerických, z toho dvě třetiny ve volné přírodě.[2] Zimuje v Aransas County na pobřeží Mexického zálivu, na ostrově San José Island a u Kissimmee na Floridě, vedle národního parku Wood Buffalo začal hnízdit také nedaleko vesnice Necedah ve Wisconsinu.

Jeřáb americký (Grus americana) nebo také jeřáb bělohřbetý je ohrožený druh jeřábovitého ptáka žijícho v Severní Americe.

Trompetértrane (Grus americana) er en traneart, der lever i Canada.

Der Schreikranich (Grus americana) ist ein Vogel aus der Familie der Kraniche (Gruidae). Seine Brutgebiete liegen in den Feuchtgebieten der Prärien im mittleren Kanada. Die noch wildlebenden Populationen überwintern in Texas.

Der Schreikranich, der zu den weltweit seltensten Vögeln zählt, war ursprünglich in den Feuchtgebieten in der Langgrasprärie im Mittleren Westen Nordamerikas beheimatet. Vermutlich war er niemals sehr zahlreich und die Population überstieg niemals die Zahl von 10.000 Individuen.[1] Als die Prärie und Feuchtgebiete in den letzten Jahrhunderten in Agrarland umgewandelt wurden, gingen die Bestände rasch zurück, da der verfügbare Lebensraum schnell abnahm und Schreikraniche empfindlich auf Störungen am Brutplatz reagieren. Sie wurden außerdem bejagt, so dass 1937 vermutlich nur noch vierzig Individuen lebten und 1941 nur mehr 15 oder 16 Vögel vorhanden waren, die in einem entlegeneren Teil der borealen Nadelwälder in Kanada brüteten.[2] Seitdem sind sehr große Anstrengungen unternommen worden, den Schreikranich vor dem Aussterben zu bewahren.

Die ausgewachsenen Vögel haben ein weißes Gefieder mit einer roten Fläche auf der Kopfoberfläche und einem langen dunklen Schnabel. Sie fliegen wie alle Kraniche mit ausgestrecktem Hals; dabei kontrastieren die schwarzen Handschwingen deutlich zum sonst rein weißen Gefieder. Noch nicht ausgewachsene Vögel haben ein blassbraunes Gefieder.

Schreikraniche suchen in flachem Wasser und Feldern nach Nahrung. Zu ihrer Nahrung zählen Insekten, Wasserpflanzen und aquatische Wirbellose sowie Beeren.

Momentan gibt es drei getrennte Populationen.

Die ursprüngliche Gruppe besteht aus Tieren, die nie in Gefangenschaft gelebt haben. Sie verbringt den Sommer im Wood-Buffalo-Nationalpark in Kanada, wo die Kraniche nisten und ihre Jungen aufziehen. Im Herbst ziehen sie in das etwa 4000 Kilometer entfernte Aransas National Wildlife Refuge in Texas. Dort überwintern sie, bis sie im Frühjahr wieder nach Kanada ziehen. Gegenwärtig besteht diese Gruppe aus 216 Individuen.

Schreikraniche nisten auf dem Boden, und zwar meist auf kleinen Bodenerhebungen in Sumpfgebieten. Das Weibchen legt ein bis drei Eier. Die Jungvögel werden von beiden Elternvögeln gefüttert. Normalerweise überlebt nur ein Jungvogel pro Saison.

Der erste Schritt zum Erhalt des Schreikranichs war der strenge Schutz des einzig verbliebenen Brutgebietes im Wood-Buffalo-Nationalpark, während gleichzeitig das Überwinterungsgebiet in Aransas, Texas geschützt wurde. Des Weiteren versuchte man, einen weiteren Abschuss der Kraniche durch Jäger zu unterbinden. Damit konnte zunächst der Populationsrückgang aufgehalten werden. Allmählich nahm die Zahl der Schreikraniche wieder zu.

Sehr früh war jedoch klar, dass eine Katastrophe wie der Ausbruch einer Epidemie oder ein Schlechtwetterereignis dazu führen könnte, dass die einzige noch verbliebene Population so geschwächt würde, dass ein Überleben der Art nicht weiter gewährleistet wäre. Bereits 1967 beschloss man daher, Schreikraniche in menschlicher Obhut nachzuzüchten.[3] Im Wood-Buffalo-Nationalpark wurden deshalb aus Gelegen mit mindestens zwei Eiern jeweils ein Ei entfernt, ins Patuxent Wildlife Research Center im US-amerikanischen Bundesstaat Maryland gebracht und dort künstlich ausgebrütet.[4] Mit dieser Maßnahme sollte sichergestellt werden, dass es ein Reservoir an Schreikranichen geben würde, sollte die einzig freilebende Population durch ein Extremereignis vernichtet werden.

Artenschutzexperten kamen gleichzeitig jedoch zu dem Schluss, dass es für das langfristige Überleben des Schreikranichs am sinnvollsten wäre, wenn eine zweite Population an einem anderen Ort etabliert würde. Dies schien möglich, weil Schreikraniche zu den verhältnismäßig wenigen Zugvögeln gehören, die ihre Wanderroute erlernen. 2001 wurde diese Population begründet. Bei diesen Vögeln handelt es sich wie bei der ursprünglichen Gruppe um Zugvögel. Allerdings sind diese Vögel in Gefangenschaft geschlüpft und aufgezogen worden. Sie wurden mit Hilfe eines Ultraleichtflugzeuges trainiert, in ihr Sommerrevier im Necedah National Wildlife Refuge in Wisconsin zu ziehen und im Herbst zu ihrem Winterquartier im Chassahowitzka National Wildlife Refuge in West-Florida zurückzukehren. Im Jahre 2009 zählte dieser neu begründete Kranichtrupp achtzig Vögel. Der erste wild in Wisconsin aufgewachsene Jungkranich folgte 2006 seinen Elternvögeln auf dem Zug nach Süden bis Florida.[5]

Zusätzlich hat man eine Population geschaffen, die nicht zieht. 1993 wurde eine zweite Population Schreikraniche in Zentral-Florida angesiedelt. Jedes Jahr werden dort etwa 20 in Gefangenschaft geschlüpfte und aufgezogene Jungvögel in die Freiheit entlassen. So versucht man in Florida eine stabile Population von Schreikranichen aufzubauen, die allerdings keine Zugvögel sind. Einige dieser Vögel haben bereits das Erwachsenenalter erreicht und mit dem Nisten begonnen. 2002 wurde hier der erste Jungvogel flügge. Diese Gruppe besteht zurzeit aus 74 Individuen.

Heute leben 382 ausgewachsene Kraniche in der Wildnis, von denen aber nur 250 adult und fortpflanzungsfähig sind. In Gefangenschaft leben weitere 151 Individuen (Stand: 2009).

Der Schreikranich (Grus americana) ist ein Vogel aus der Familie der Kraniche (Gruidae). Seine Brutgebiete liegen in den Feuchtgebieten der Prärien im mittleren Kanada. Die noch wildlebenden Populationen überwintern in Texas.

Der Schreikranich, der zu den weltweit seltensten Vögeln zählt, war ursprünglich in den Feuchtgebieten in der Langgrasprärie im Mittleren Westen Nordamerikas beheimatet. Vermutlich war er niemals sehr zahlreich und die Population überstieg niemals die Zahl von 10.000 Individuen. Als die Prärie und Feuchtgebiete in den letzten Jahrhunderten in Agrarland umgewandelt wurden, gingen die Bestände rasch zurück, da der verfügbare Lebensraum schnell abnahm und Schreikraniche empfindlich auf Störungen am Brutplatz reagieren. Sie wurden außerdem bejagt, so dass 1937 vermutlich nur noch vierzig Individuen lebten und 1941 nur mehr 15 oder 16 Vögel vorhanden waren, die in einem entlegeneren Teil der borealen Nadelwälder in Kanada brüteten. Seitdem sind sehr große Anstrengungen unternommen worden, den Schreikranich vor dem Aussterben zu bewahren.

De Trompetkraan (Grus americana) is in soarte út fan de famylje fan de Kraanfûgels yn Noard-Amearika.

De Trompetkraan is in 150 sm grutte fûgel dy't in 6 kg waget. De folwoeksen fûgels hawwe wite fearren mei in read plak boppe op de kop en in lange donkere snaffel. Lykas alle kraanfûgels fleane se mei de nekke útstrekt werby de swarte úteinen fan de wjukken opfalle neist de foar de rest wite fearren.

De Trompetkraan komt foar yn Noard-Amearika. Syn briedgebiet leit yn sompen yn de prêrje yn it midden fan Kanada yn en rûnom it Wood Buffalo National Park. De fûgels oerwinterje yn Texas yn Aransas National Wildlife Refuge, dat fanwege de trompetkranen in nasjonaal park wurden is.

De Trompetfûgels sykje harren iten yn ûndjip wetter en yn it fjild. Se ite ynsekten, wetterplanten en dieren dy't yn it wetter foarkomme sa as krabben.

De Trompetkranen meitsje harren nêst op de grûn yn de sompen, meast op in lytse ferheging. It wyfke leit ien oant trije aaien dy't in sa'n 30 dagen útbredt wurde. De jongen wurde troch beide âlden fuorre en kinne nei sa'n 80-90 dagen fleane.

De Trompetkraan is ien fan de selsumste fûgelsoarten fan de wrâld. De weromgong fan dizze kraanfûgelsoarte dy't eartiids yn it hiele middenwesten fan Noard-Amearika foarkaam is meast ta te skriuwen oan it ferliezen fan harren libbensgebiet. Yn 1941 bestie de populaasje yn it wyld noch mar út 21 fûgels. Sûnt dy tiid is it tal fûgels troch beskermjende maatregels wer wat grutter wurden. Hjoed-de-dei binne der sa'n 330 Trompetkranen wêrfân in 200 yn it wyld libje.

De Trompetkraan (Grus americana) is in soarte út fan de famylje fan de Kraanfûgels yn Noard-Amearika.

Америк тогоруу (Grus americana) нь Хойд Америкийн хамгийн өндөр шувуу юм. Тогорууны төрлийнхнөөс Хойд Америкт түүнээс гадна Канад тогоруу л байдаг. Байгаль дээр зэрлэгээрээ 22 - 24 насалдаг гэж үздэг тус шувуу ердөө 400 гаруй л үлдсэн бололтой[2].

Америк тогоруу (Grus americana) нь Хойд Америкийн хамгийн өндөр шувуу юм. Тогорууны төрлийнхнөөс Хойд Америкт түүнээс гадна Канад тогоруу л байдаг. Байгаль дээр зэрлэгээрээ 22 - 24 насалдаг гэж үздэг тус шувуу ердөө 400 гаруй л үлдсэн бололтой.

The whooping crane (Grus americana) is the tallest North American bird, named for its whooping sound. It is an endangered crane species. Along with the sandhill crane (Antigone canadensis), it is one of only two crane species native to North America. The whooping crane's lifespan is estimated to be 22 to 24 years in the wild. After being pushed to the brink of extinction by unregulated hunting and loss of habitat to just 21 wild and two captive whooping cranes by 1941, conservation efforts have led to a partial recovery.[3] The total number of cranes in the surviving migratory population, plus three reintroduced flocks and in captivity, exceeds 800 birds as of 2020.

An adult whooping crane is white with a red crown and a long, dark, pointed bill. However, immature whooping cranes are cinnamon brown. While in flight, their long necks are kept straight and their long dark legs trail behind. Adult whooping cranes' black wing tips are visible during flight.

On average, the whooping crane is the fifth largest extant species of crane in the world.[4] Whooping cranes are the tallest bird native to North America and are anywhere from the third to the fifth heaviest species on the continent, depending on which figures are used. The species can reportedly stand anywhere from 1.24 to 1.6 m (4 ft 1 in to 5 ft 3 in) in height.[5][6] Wingspan, at least typically, is from 2 to 2.3 m (6 ft 7 in to 7 ft 7 in).[5] Widely reported averages put males at a mean mass of 7.3 kg (16 lb), while females weigh 6.2 kg (14 lb) on average (Erickson, 1976).[7] However, one small sample of unsexed whooping cranes weighed 5.82 kg (12.8 lb) on average.[8] Typical weights of adults seem to be between 4.5 and 8.5 kg (9.9 and 18.7 lb).[4][5] The body length, from the tip of the bill to the end of the tail, averages about 132 cm (4 ft 4 in).[9] The standard linear measurements of the whooping cranes are a wing chord length of 53–63 cm (21–25 in), an exposed culmen length of 11.7–16 cm (4.6–6.3 in) and a tarsus of 26–31 cm (10–12 in).[4][10] The only other very large, long-legged white birds in North America are: the great egret, which is over a foot (30 cm) shorter and one-seventh the weight of this crane; the great white heron, which is a morph of the great blue heron in Florida; and the wood stork. All three other birds are at least 30% smaller than the whooping crane. Herons and storks are also quite different in structure from the crane. Larger individuals (especially males of the larger races) of sandhill crane can overlap in size with adult whooping cranes but are obviously distinct at once for their gray rather than white color.[11][12]

Their calls are loud and can carry several kilometers. They express "guard calls", apparently to warn their partner about any potential danger. A crane pair jointly calls rhythmically ("unison call") after waking in the early morning, after courtship, and when defending their territory. The first unison call ever recorded in the wild was taken in the whooping cranes' wintering area of the Aransas National Wildlife Refuge during December 1999.[13]

At one time, the range for the whooping crane extended throughout midwestern North America as well as southward to Mexico.[14][1] By the mid-20th century, the muskeg of the taiga in Wood Buffalo National Park, Alberta and Northwest Territories, Canada, and the surrounding area had become the last remnant of the former nesting habitat of the Whooping Crane Summer Range. However, with the recent Whooping Crane Eastern Partnership Reintroduction Project, whooping cranes nested naturally for the first time in 100 years in the Necedah National Wildlife Refuge in central Wisconsin, United States, and these have subsequently expanded their summer range in Wisconsin and surrounding states, while reintroduced experimental non-migratory populations have nested in Florida and Louisiana.

Whooping cranes nest on the ground, usually on a raised area in a marsh. The female lays 1 or 2 eggs, usually in late-April to mid-May. The blotchy, olive-coloured eggs average 2½ inches in breadth and 4 inches in length (60 by 100 mm), and weigh about 6.7 ounces (190 g). The incubation period is 29–31 days. Both parents brood the young, although the female is more likely to directly tend to the young. Usually no more than one young bird survives in a season. The parents often feed the young for 6–8 months after birth and the terminus of the offspring-parent relationship occurs after about 1 year.[15]

Breeding populations winter along the Gulf coast of Texas, United States, near Rockport on the Aransas National Wildlife Refuge and along Sunset Lake in Portland, Matagorda Island, Isla San Jose, and portions of the Lamar Peninsula and Welder Point, which is on the east side of San Antonio Bay.[16]

The Salt Plains National Wildlife Refuge in Oklahoma is a major migratory stopover for the crane population, hosting over 75% of the species annually.[17][18]

As many as nine whooping cranes were observed at various times on Granger Lake in Central Texas in the 2011/2012 winter season. Drought conditions in 2011 exposed much of the lake bed, creating ample feeding grounds for these cranes just as they were taking their autumn migration through Texas.[19]

Their many potential nest and brood predators include American black bear, wolverine, gray wolf, cougar, red fox, Canada lynx, bald eagle, and common raven. Golden eagles have killed some young whooping cranes and fledglings.[20] Due to their large size, adult birds in the wild have few predators.[4][21] However, American alligators have taken a few whooping cranes in Florida, and the bobcat has killed many captive-raised whooping cranes in Florida and Texas.[11][22] In Florida, bobcats have caused the great majority of natural mortalities among whooping cranes, including several ambushed adults and the first chick documented to be born in the wild in 60 years.[22][23][24][25][26] Adult cranes can usually deter or avoid attacks by medium-sized predators such as coyotes when aware of a predator's presence, but the captive-raised cranes haven't learned to roost in deep water, which makes them vulnerable to ambush.[27][28] As they are less experienced, juvenile cranes may be notably more vulnerable to ambushes by bobcats.[29] Patuxent Wildlife Research Center scientists believe that this is due to an overpopulation of bobcats caused by the absence or decrease in larger predators (the endangered Florida panther and the extirpated red wolf) that formerly preyed on bobcats.[22] At least 12 bobcats have been trapped and relocated in an attempt to save the cranes.[28]

These birds forage while walking in shallow water or in fields, sometimes probing with their bills. They are omnivorous but tend to be more inclined to animal material than most other cranes. Only the red-crowned crane may have a more carnivorous diet among living cranes.[30] In their Texas wintering grounds, this species feeds on various crustaceans, mollusks, fish (such as eel), small reptiles and aquatic plants. Potential foods of breeding birds in summer include frogs, small rodents, small birds, fish, aquatic insects, crayfish, clams, snails, aquatic tubers, and berries. Six studies from 1946 to 2005 have reported that blue crabs are a significant food source[31] for whooping cranes wintering at Aransas National Wildlife Refuge, constituting up to 90 percent of their energy intake in two winters; 1992–93 and 1993–94.

Waste grain, including wheat, barley, and corn, is an important food for migrating whooping cranes,[11] but whooping cranes don't swallow gizzard stones and digest grains less efficiently than sandhill cranes.

In earlier years, whooping crane chicks had been caught and banded (in the breeding areas of Wood Buffalo National Park), which has delivered valuable insight into individual life history and behaviour of the cranes. This technique, however, has been abandoned due to imminent danger for the cranes and the people performing the catching and banding activities.

By recording guard and unison calls followed by frequency analysis of the recording, a "voiceprint" of the individual crane (and of pairs) can be generated and compared over time. This technique was developed by B. Wessling and applied in the wintering refuge in Aransas and also partially in the breeding grounds in Canada over 5 years.[32] It delivered interesting results, i.e. that besides a certain fraction of stable pairs with strong affinity to their territories, there is a big fraction of cranes who change partners and territories.[33] Only one of the exciting results was to identify the "Lobstick" male when he still had his band; he later lost his band and was recognized by frequency analysis of his voice and then was confirmed to be over 26 years old and still productive.

Whooping cranes are believed to have been naturally rare, and major population declines caused by habitat destruction and overhunting led them to them become critically endangered. Even with hunting bans, illegal hunting has continued in spite of potential substantial financial penalties and possible prison time.[34][35][36] The population went from an estimated 10,000+ birds before the settling of Europeans on the continent to 1,300-1,400 birds by 1870. By 1938 there were just 15 adults in a single migratory flock, plus about thirteen additional birds living in a non-migratory population in Louisiana, but the latter were scattered by a 1940 hurricane that killed half of them, while the survivors never again reproduced in the wild.[37][38]

In the early 1960s, Robert Porter Allen, an ornithologist with the National Audubon Society, appeared as a guest challenger on the network television show To Tell The Truth, which gave the Conservation movement some opportunity to update the public on their efforts to save the whooping crane from extinction. His initial efforts focused on public education, particularly among farmers and hunters. Beginning in 1961, the Whooping Crane Conservation Association (WCCA), was established to improve the status of the whooping cranes. This non-profit organization functioned largely by influencing federal, state and provincial political decisions and educating the general public about the critical status of the bird. The whooping crane was declared endangered in 1967.

Allen had begun an effort at captive breeding with a female crane named 'Josephine', the sole survivor of the Louisiana population, injured and taken into captivity in 1940, and two successive injured birds from the migratory population, 'Pete' and 'Crip', at the Audubon Zoo and the Aransas refuge. Josephine and Crip produced the first whooping crane born in captivity in 1950, but this chick only lived four days, and though decades of further efforts produced more than 50 eggs before Josephine's death in 1965, only four chicks survived to adulthood and none of them bred.[37][39] At the same time, the wild population was not thriving. In spite of the efforts of conservationists, hunting bans and educational programs, the aging wild population would gain only 10 birds in the first 25 years of monitoring, with entire years passing without a single new juvenile joining those that returned to the Texas wintering grounds. This led to a renewed tension between those who favored efforts to preserve the wild population and others seeing a captive breeding program as the only hope for whooping crane survival, even though it must depend on individuals withdrawn from the extremely-vulnerable wild population.[37]

Identification of the location of the summer breeding grounds of the whooping cranes at Wood Buffalo National Park in 1954 allowed more detailed study of their reproductive habits in the wild, and led to the observation that while many breeding pairs laid two eggs, rearing efforts seemed to favor a single chick, and both chicks would almost never survive to fledge. It was concluded that the removal of a single egg from a two-egg clutch should still leave a single hatchling most likely to survive, while providing an individual for captive breeding. Such removals in alternating years showed no decline in the reproductive success of the wild cranes. The withdrawn eggs were transferred to the Patuxent Wildlife Research Center in Maryland, where approaches for hatching and rearing crane chicks in captivity had already been optimized using the more-numerous sandhill cranes.[37] Initial challenges getting the resultant birds to reproduce, even using artificial insemination approaches, would give impetus to the first, unsuccessful attempt at reintroduction, by swapping whooping crane eggs into the nests of the more numerous sandhill cranes as a way to establish a backup population.[37]

In 1976, with the wild population numbering only 60 birds and having increased at an average of only one bird per year over the past decades,[37] ornithologist George W. Archibald, co-founder of the International Crane Foundation in Baraboo, Wisconsin, began working with 'Tex', a female whooping crane hatched at the San Antonio Zoo in 1967 to Crip and his new mate, the wild-captured 'Rosie', to get her to lay a fertile egg through artificial insemination.[39][40] Archibald pioneered several techniques to rear cranes in captivity, including the use of crane costumes by human handlers. Archibald spent three years with Tex, acting as a male crane – walking, calling, dancing – to shift her into reproductive condition. As Archibald recounted the tale on The Tonight Show in 1982, he stunned the audience and host Johnny Carson with the sad end of the story – the death of Tex shortly after the hatching of her one and only chick, named 'Gee Whiz'.[41][42] Gee Whiz was successfully raised and mated with female whooping cranes. The techniques pioneered at Patuxent, the International Crane Foundation and a program at the Calgary Zoo would give rise to a robust multi-institutional captive breeding program that would supply the cranes used in several additional captive breeding and reintroduction programs. A single male crane, 'Canus', rescued in 1964 as an injured wild chick and taken to Patuxent in 1966, would by the time of his 2003 death be the sire, grandsire or great-grandsire of 186 captive-bred whooping cranes.[43] In 2017, the decision was made for the Patuxent Wildlife Research Center to end its 51-year effort to breed and train whooping cranes for release, due to changing priorities and in the face of budget cuts by the Trump administration. Their flock of 75 birds was moved in 2018 to join captive breeding programs at zoos or private foundations, including the Calgary Zoo, the International Crane Foundation, the Audubon Species Survival Center in Louisiana, and other sites in Florida, Nebraska, Oklahoma and Texas. This relocation is expected to negatively impact the reproductive success of the captive cranes, at least in the short term, and concerns were raised over its impact on the reintroduction efforts for which the Patuxent program had been providing birds.[44][45]

Meanwhile, the wild crane population began a steady increase, such that in 2007 the Canadian Wildlife Service counted 266 birds at Wood Buffalo National Park, with 73 mating pairs that produced 80 chicks, 39 of which completed the fall migration,[46] while a United States Fish and Wildlife Service count in early 2017 estimated that 505 whooping cranes, including 49 juveniles, had arrived at Aransas National Wildlife Refuge that season.[47] As of 2020, there were an estimated 677 birds living in the wild, in the remnant original migratory population as well as three reintroduced populations, while 177 birds were at the time held in captivity at 17 institutions in Canada and the United States,[48] putting the total population at over 800.

The wild cranes winter in marshy areas along the Gulf Coast in and surrounding the Aransas National Wildlife Refuge. An environmental group, The Aransas Project, has sued the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ), maintaining that the agency violated the Endangered Species Act by failing to ensure adequate water supplies for the birds' range. The group attributes the deaths of nearly two dozen whooping cranes in the winter of 2008 and 2009 to inadequate flows from the San Antonio and Guadalupe rivers.[49] In March 2013 during continuing drought conditions, a federal court ordered TCEQ to develop a habitat protection plan for the crane and to cease issuing permits for waters from the San Antonio and Guadalupe rivers. A judge amended the ruling to allow TCEQ to continue issuing permits necessary to protect the public's health and safety. An appeals court eventually granted a stay in the order during the appeals process.[49][50] The Guadalupe-Blanco and San Antonio river authorities joined TCEQ in the lawsuit, warning that restricting the use of their waters would have serious effects on the cities of New Braunfels and San Marcos as well as major industrial users along the coast.[49] To address the potential of future crowding that may result from the increasing migratory population, in 2012 and following years, purchases of small plots of land and acquisition of conservation easements covering larger areas has led to the protection of tens of thousands of additional acres of potential coastal habitat near the Aransas reserve.[51][52][53][54] A large purchase of over 17,000 acres in 2014 was paid for with $35 million made available from the settlement over the Deepwater Horizon oil spill and an additional $15 million raised by a Texas parks non-profit.[55]

Concerns have been raised over the effects of climate change on the migratory cycle of the surviving wild population. The cranes arrive on their nesting grounds in April and May to breed and begin their nesting. When young whooping cranes are ready to leave the nest, they depart in September and follow the migratory trail through Texas.[56]

Several attempts have been made to establish other breeding populations outside of captivity.

A major hurdle with some of these reintroduced populations has been deaths to illegal hunting.[88] Over a period of two years, five of the approximately 100 whooping cranes in the Eastern Migratory Population were illegally shot and killed. One of the dead cranes was the female known as "First Mom". In 2006, she and her mate were the first eastern captive raised and released pair to successfully raise a chick to adulthood in the wild. This was a particular blow to that population because whooping cranes do not yet have an established successful breeding situation in the East. On March 30, 2011, Wade Bennett, 18, of Cayuga, Indiana and an unnamed juvenile pleaded guilty to killing First Mom. After killing the crane, the juvenile had posed holding up her body. Bennett and the juvenile were sentenced to a $1 fine, probation, and court fees of about $500, a penalty which was denounced by various conservation organizations as being too light. The prosecuting attorney has estimated that the cost of raising and introducing to the wild one whooping crane could be as much as $100,000.[89][90][91][92] Overall, the International Crane Foundation estimates that the nearly 20% of deaths among the reintroduced cranes in the Eastern Migratory Population are due to shootings.[88]

Illegal shootings have accounted for an even larger proportion of mortality among the birds introduced into the Louisiana population,[93] with about 10% of the first 147 released cranes being shot and killed. Two juveniles were apprehended for a 2011 incident,[94] a Louisiana man was sentenced to 45 days imprisonment and a $2500 fine after pleading guilty to a killing in November 2014,[95] and a Texas man was fined $25,000 for a January 2016 shooting and barred from possessing firearms during a 5-year probation period, on subsequent violation of which he was given an 11-month custodial sentence.[96][97] On the other hand, a Louisiana man cited for a July 2018 shooting received probation, community service and hunting and fishing restrictions but no fine or firearms restriction.[87] Two Louisiana juveniles were cited in 2018 for a May 2016 incident.[98]

In the season one King of the Hill episode Straight as an Arrow, Bobby Hill incapacitates an endangered Whooping Crane, one of five left in the world. They mistake it for being dead, and spend the episode trying to get it out of the nature preserve to bury it.

The whooping crane (Grus americana) is the tallest North American bird, named for its whooping sound. It is an endangered crane species. Along with the sandhill crane (Antigone canadensis), it is one of only two crane species native to North America. The whooping crane's lifespan is estimated to be 22 to 24 years in the wild. After being pushed to the brink of extinction by unregulated hunting and loss of habitat to just 21 wild and two captive whooping cranes by 1941, conservation efforts have led to a partial recovery. The total number of cranes in the surviving migratory population, plus three reintroduced flocks and in captivity, exceeds 800 birds as of 2020.

La Amerika gruo, Grus americana, estas granda birdo de familio Gruedoj, tre minacata de malapero.

Ili bredas en nordorienta Kanado (Wood Buffalo Nacia Parko) somere kaj migras vintre al sudmarborda Teksaso (Aransas Nacia Rifuĝejo) ekde oktobro ĝis marto, same ol Griza gruo en Eŭropo. En la 19a jarcento 1500 birdoj faris tiun migron. Poste la loĝantaro malpliiĝis ĝis nur 18 dum la 30aj jaroj kaj 16! en 1941. Poste malrapide pliiĝis ĝis sufiĉe pli ol cento fine de la 20a jarcento kaj preskaŭ ducento komence de la 21a kaj lastatempe ĉirkaŭ tricento. Tamen danĝero malaperi por tiu specio daŭre ekzistas. Nuntempe estas ankaŭ etaj loĝantaroj en ŝtatoj Nov-Meksiko, Florido kaj Viskonsino (mezbredado). Ties medio estas marĉecaj ebenaĵoj.

Ili estas grandaj birdoj 1,5 m longaj kun enverguro de 2,3 m; la plej altaj birdoj en Nordameriko. Maskloj estas iom pli grandaj ol inoj.

Temas pri gruo tute blanka, escepte pro la antaŭa parto de la kapo ĝis okulo kaj iom malantaŭe supre kaj sube, kio estas senpluma kaj nigra kun ruĝaj briloj ĉefronte kaj rozkolora ĉe bekobazo kaj nigraj unuaj plumoj en flugiloj (flugilpintoj) kiuj estas videblaj nur dumfluge. Beko estas grizo kaj okuloj flavaj. Kruroj estas longaj kaj nigraj.

Junuloj havas kanelflavajn kapon, supran kolon kaj makulojn dorse kaj flugile. Nur post kvar monatoj tiuj kanelflavaj partoj komencas blankiĝi, kio jam estas farita post unu jaro sed nur post du jaroj finas entute.

Tiuj nearktisaj gruoj pariĝas porĉiame, sed ili akceptas novan partneron se la eksa mortiĝas. Ili konstruas surplankan neston el junkoj, kie la ino demetas 1 ĝis 3 ovojn. Ambaŭ gepatroj laŭvice deĵoras ĉeneste kaj zorgas. Kovado daŭras unu monaton. Kutime du idoj eloviĝas kaj unu ido transvivas. La ido vintras la unuan jaron kun la gepatroj kaj separiĝas antaŭ la printempa migrado ĉar junuloj migras grupe. La 4an jaron ili jam estas sekse maturuloj.

Tiuj birdoj vivas ĝis 22 aŭ 24 jarojn. Ili estas ĉiomanĝantaj: insektoj, ranoj, ronĝuloj, birdetoj, fisextoj kaj beroj somere. Vintre ili manĝas bluajn krabojn kaj tapiŝkonkojn. Ili manĝas en ebenaĵoj ankaŭ glanojn, helikojn, insektojn kaj kankrojn.

Tiuj gruoj migras sole, pare, familie aŭ laŭ etaj birdaroj, foje kun aro da Kanada gruo. Ili migras tage kaj haltas por ripozi kaj manĝi ĉe tradciaj ripozejoj. Ili vintras ĉe la samaj lokoj kie vintris unuajare kun siaj gepatroj.

Kialoj por jarcenta malpliiĝo estis ĉasado, kolektado ĉu de ovoj ĉu de ekzempleroj, homa ĝenado kaj malaperigo de ties medio por terkulturado. Lastatempe danĝeroj estas poluado, kolizioj kontraŭ elektraj kabloj aŭ drataj bariloj, uraganoj, ktp. En kaptiveco danĝeroj estas malsanoj kaj parazitoj. Por la eksperimenta loĝantaro de Florido predado de linkoj endanĝerigis la eksperimenton.

La Amerika gruo, Grus americana, estas granda birdo de familio Gruedoj, tre minacata de malapero.

La grulla trompetera (Grus americana) es una especie de ave gruiforme de la familia de las grullas (Gruidae), denominada trompetera por el sonido de su llamado. Es el ave más alta de América del Norte, y se encuentra en peligro de extinción.[1] Junto con la grulla canadiense, son las únicas dos especies de grullas que se encuentran en América del Norte. La expectativa de vida de una grulla trompetera se estima puede llegar a 22-24 años en la naturaleza.[2]

Las Grullas Trompeteras adultas son blancas con la coronilla roja y el pico largo, puntiagudo y oscuro. Las inmaduras son de color castaño claro. Mientras vuelan, sus largos cuellos se mantienen estirados y sus largas patas oscuras se destacan atrás. Las puntas negras de las alas de las grullas trompeteras adultas son visibles durante el vuelo.

La altura de la especie es de unos 150 cm y la envergadura de alas de unos 230 cm. Los machos pesan en promedio 7,5 kg, y las hembras unos 6,5 kg.[3] Las únicas otras aves muy grandes, de largas patas y blancas en América del Norte son la Garceta Grande, que tiene más de 30 cm menos en altura y una séptima parte del peso de esta grulla; el morfo blanco de la Garza Azulada de la Florida y el Tántalo Americano. Estas últimas son un 30 % menores que la grulla trompetera. Las garzas y las cigüeñas son también de estructura bastante diferente de las grullas.

EL hábitat reproductivo de las Grullas Trompeteras es el de las turberas de musgo sphagnum de la taiga; actualmente, su único lugar de anidación conocido es el Whooping Crane Summer Range en el parque nacional Wood Buffalo en Alberta, Canadá y las áreas circundantes. Con el reciente Proyecto de Reintroducción de la Asociación Grulla Trompetera del Este, las grullas trompeteras anidaron naturalmente por primera vez en 100 años en el Refugio Nacional de Vida Silvestre de Necedah en el centro de Wisconsin, Estados Unidos. Ellas anidan en el suelo, usualmente en un área elevada dentro de una ciénaga. La hembra pone 1 a 3 huevos, usualmente de finales de abril a mediados de mayo. Los huevos oliváceos manchados promedian 60 mm de ancho y 100 mm de alto y pesan unos 190 g. El periodo de incubación es de 29-35 días. Ambos padres cuidan al polluelo, aunque la hembra es más probable que atienda al polluelo. usualmente no sobrevive más que un polluelo por cada estación. Los progenitores a menudo alimentan al joven por 6-8 meses después del nacimiento y el final de la relación parental con la cría ocurre aproximadamente después de un año.

Las poblaciones actualmente en reproducción invernan en Texas a lo largo de la costa del golfo de México en Estados Unidos, cerca de Corpus Christi en el Refugio Nacional de Vida Silvestre de Aransas, en la isla Matagorda, la isla San José, y en porciones de la península Lamar y punta Welder, el que está en el lado este de la bahía de San Antonio.

Hasta un 75 % de la población de Estados Unidos pasa anualmente por el Refugio Nacional de Vida Silvestre Salt Plains en Oklahoma.[4]

La grulla trompetera está amenazada principalmente como resultado de la pérdida de hábitat. En otros tiempos, el área de distribución de estas aves se extendía por todo el medio oeste de América del Norte. En 1941, la población silvestre consistía de 21 aves. desde entonces, la población ha aumentado algo, mayormente debido a esfuerzos de conservación. En abril de 2007 había unas 340 grullas trompeteras viviendo naturalmente, y otras 145 en cautiverio. La grulla trompetera es aún una de las aves más raras de América del Norte. El Servicio de Pesca y Vida Silvestre de Estados Unidos confirmó que 266 grullas trompeteras hicieron la migración al Refugio Nacional de Vida Silvestre de Aransas en 2007.[5]

Entre los muchos predadores potenciales del nido y la cría se incluyen el oso negro americano (Ursus americanus), el glotón carcayú (Gulo luscus), el lobo gris (Canis lupus), el zorro rojo (Vulpes fulva), el lince (Lynx canadensis), el pigargo americano o águila calva (Haliaeetus leucocephalus), y el cuervo común (Corvus corax). Los adultos tienen muy pocos predadores, dado que incluso las águilas es improbable que puedan derribarlos. El lince es el único predador natural que se conoce que pueda ser a un tiempo suficientemente fuerte y cauteloso como para poder atrapar una grulla adulta fuera de sus territorios de anidación.

Estas aves se alimentan mientras caminan dentro de las aguas someras o en el suelo, algunas veces sondeando con sus picos. Son omnívoras y ligeramente más inclinadas a comer materiales animales que la mayoría de las otras grullas. En los territorios de invernada en Texas, esta especie se alimenta de variados crustáceos, moluscos, peces (como la anguila), bayas, serpientes y plantas acuáticas. El alimento potencial de las aves en reproducción incluye a ranas, ratones, campañoles, aves pequeñas, peces, reptiles, libélulas, otros insectos acuáticos, langostinos, almejas, caracoles, tubérculos acuáticos, bayas, saltamontes y grillos. Los granos desperdiciados como el trigo y la cebada son importantes alimentos de las aves migratorias como la grulla trompetera.

La grulla trompetera fue declarada en peligro de extinción en 1967. Se han hecho intentos para establecer otras poblaciones reproductoras naturales.

Las grullas de la Operación Migración son criadas desde la eclosión con disfraces, enseñadas a seguir su ultraligero, volanteadas sobre su futuro territorio de cría en Wisconsin, y guiadas mediante el ultraligero en su primera migración desde Wisconsin hasta la Florida; las aves aprenden la ruta migratoria y luego vuelven por sí solas, en la primavera siguiente. La reintroducción comenzó en el otoño de 2001 y ha añadido aves a la población en cada año desde entonces (exceptuando que en el comienzo de 2007, una tormenta desastrosa mató todos los jóvenes del año de 2006 luego que llegaran a la Florida).

En septiembre de 2007, existían 52 grullas trompeteras en la Población Migrante del Este (PME), incluyendo a dos de cuatro jóvenes de un año liberados en Wisconsin, que se les permitió migrar solos (Liberación Otoñal Directa o LOD). Catorce de estas aves habían formado siete parejas; dos de estas parejas anidaron y produjeron huevos en la primavera de 2005. Los huevos se perdieron por la inexperiencia de los padres. En la primavera de 2006 algunas de las mismas parejas habían anidado nuevamente e incubaban. Dos polluelos fueron logrados en un nido, el 22 de junio de 2006. Sus dos padres fueron incubados y guiados por ultraligeros en su primera migración en 2002. Justo a 4 años de nacidos son ya jóvenes padres. Sus polluelos son los primeros polluelos nacidos silvestres, hijos de padres migrantes por el este del Misisipí en más de 100 años. Uno de estos polluelos desafortunadamente fue predado en el Refugio Nacional de Vida Silvestre de Necedah. El otro joven pollo, una hembra, ha migrado exitosamente con sus padres a Florida. Como se señaló arriba, en febrero de 2007, 17 jóvenes de un año de un grupo de 18 fueron muertos por la tormenta de tornados del centro de Florida de ese año. Todas las aves agrupadas en esa bandada parecían haber muerto en esas tormentas, pero luego una señal de un transmisor, el "Número 615", indicaba que había un sobreviviente. El ave fue luego reubicada en compañía de algunas Grus canadensis. Murió luego a finales de abril por causas desconocidas, posiblemente por el trauma de la tormenta. Las dos de las cuatro grullas trompeteras jóvenes LOD de 2006 que quedaban también murieron debido a predación.[12][13]

En el parque nacional Wood Buffalo, El Servicio Canadiense de Vida Silvestre contó 73 parejas reproductoras en 2007. Produjeron éstas 80 polluelos, de los cuales 40 sobrevivieron hasta la migración de otoño, y 39 completaron la migración al Refugio Nacional de Vida Silvestre de Aransas.[5]

La grulla trompetera (Grus americana) es una especie de ave gruiforme de la familia de las grullas (Gruidae), denominada trompetera por el sonido de su llamado. Es el ave más alta de América del Norte, y se encuentra en peligro de extinción. Junto con la grulla canadiense, son las únicas dos especies de grullas que se encuentran en América del Norte. La expectativa de vida de una grulla trompetera se estima puede llegar a 22-24 años en la naturaleza.

Amerikar kurrilo (Grus americana) Grus generoko animalia da. Hegaztien barruko Gruidae familian sailkatua dago. Ipar Amerikako hegaztirik altuena da.

Amerikar kurrilo (Grus americana) Grus generoko animalia da. Hegaztien barruko Gruidae familian sailkatua dago. Ipar Amerikako hegaztirik altuena da.

Trumpettikurki (Grus americana) on Kanadan kotoperäinen kurkilaji. Se elää nykyisin vain maan keskiosissa Luoteisterritorioiden ja Albertan rajoilla sijaitsevassa Wood Buffalon kansallispuistossa. Vastikään laji on onnistunut pesimään myös Wisconsinissa.muuttolintu, ja talvehtii pääasiassa Texasissa Meksikonlahden rannalla. Carl von Linné kuvaili lajin holotyypin Hudsoninlahdeltan Kanadasta vuonna 1758.[2]

Aikuisen trumpettikurjen ruumis on valkoinen, ja sen päässä on punainen laikku. Nokka on pitkä ja tumma. Nuoret trumpettikurjet ovat väriltään kanelinruskeita. Lentäessään trumpettikurki pitää pitkän kaulansa suorassa, ja jalat seuraavat niin ikään suorina perässä. Aikuisen trumpettikurjen mustat siivenkärjet näkyvät lentäessä.

Trumpettikurki on tyypillisesti 1,26–1,6 metriä pitkä[3] ja siipienväliltään noin 2 metriä.[3] Aikuisen yksilön paino on noin 4,5–8,5 kiloa. Koiraat ovat naaraita kookkaampia.[3][4]

Trumpettikurki (Grus americana) on Kanadan kotoperäinen kurkilaji. Se elää nykyisin vain maan keskiosissa Luoteisterritorioiden ja Albertan rajoilla sijaitsevassa Wood Buffalon kansallispuistossa. Vastikään laji on onnistunut pesimään myös Wisconsinissa.lähde? Populaation koko on 382 yksilöä. Se on muuttolintu, ja talvehtii pääasiassa Texasissa Meksikonlahden rannalla. Carl von Linné kuvaili lajin holotyypin Hudsoninlahdeltan Kanadasta vuonna 1758.

Grus americana

La Grue blanche (Grus americana) est un échassier et le plus grand oiseau d'Amérique du Nord, appartenant à la famille des Gruidae. Cette espèce est en voie de disparition (leur nombre a décru de manière dramatique à partir du milieu du XIXe siècle : les pionniers asséchaient les zones humides pour les cultiver et chassaient les grues pour leur viande), mais fait l'objet de plusieurs programmes de protection et de conservation des gouvernements du Canada et des États-Unis : 200 individus survivants en octobre 2005, 340 en liberté au printemps 2007. Le recensement annuel de février 2010 fait état de 263 grues en liberté. On la trouve notamment dans les marais de l'Aransas National Wildlife Refuge et du parc national de Wood Buffalo.

L’ensemble du plumage de l’adulte est blanc immaculé sauf les primaires qui sont noires, le dessus de la tête qui est rouge et la face qui comporte du rouge et du noir. Les primaires noires ne sont visibles que lorsque les ailes sont déployées. Les pattes sont gris foncé presque noir et le bec est vert foncé. Le mâle et la femelle sont identiques[1],[2].

La Grue blanche est le plus grand des oiseaux nord-américains, mesurant presque 1,5 m de haut posé au sol. L’envergure est de 2 à 2,3 m et la longueur de 1,12 à 1,40 m. Le mâle est un peu plus grand et plus lourd que la femelle, pesant environ 7,3 kg alors que la femelle fait environ 6,4 kg.

La Grue blanche est omnivore. Elle trouve sa nourriture autant sur et dans le sol, dans l’eau que dans la végétation. Sur les aires de nidification, elle se nourrit de mollusques, de crustacés, d’insectes aquatiques, de petits poissons, de grenouilles et de couleuvres[3], [4], mais aussi de petits oiseaux, de rongeurs et de baies.

Pendant la migration, elle se nourrit de grenouilles, de poissons, de tubercules de plantes, d’écrevisses, d’insectes et de grains dans les champs cultivés. Pendant l’hiver, dans les marais et le long des côtes, l’oiseau capture surtout des crabes (en particulier le Crabe bleu) et des palourdes. À l’intérieur des terres et dans les champs, il ne dédaigne pas les glands, les escargots, les souris, les campagnols, les écrevisses, les sauterelles et les couleuvres[5],[6].

Construit avec des plantes aquatiques, le nid mesure entre 0,6 et 1,5 m de diamètre et émerge jusqu'à 0,45 m au-dessus de l'eau. La femelle pond généralement 2 œufs entre fin avril et mi-mai. L'incubation dure 28 à 31 jours, mais en général un seul petit survit. Les poussins sont couverts d'un duvet brun cannelle dessus et gris pâle ou blanc brunâtre dessous. Ils s'envolent 80 à 90 jours après leur naissance.

La plus vieille grue blanche connue, une espèce protégée car menacée de disparition, est morte à l’âge de 28 ans. La grue, une femelle, avait été baguée peu après sa naissance dans le parc national de Wood Buffalo (Canada). Sa carcasse a été retrouvée le mercredi 2 novembre 2005 au bord du lac Muskki en Saskatchewan (Canada).

Les oiseaux captifs peuvent atteindre 40 ans.

L’aire de nidification dans le parc national de Wood Buffalo se compose d’une mosaïque d’étangs de faible profondeur et d’étendue variable (1-25 ha) sur des sols mal drainés. Ces étangs ont pour la plupart un fond meuble de marne. Les étangs sont séparés par d’étroites bandes de terre ferme ou croissent les épinettes blanche, les épinettes noire, les mélèzes laricin et les saules. À ces essences de plus grandes tailles se mêlent le Bouleau glanduleux, le Thé du Labrador et le Raisin d'ours. Dans l’eau, le Scirpe est la plante la plus commune, quoique le Typha, Carex aquatilis et les algues du genre Chara peuvent être également présents[1].

Dans le Refuge National de la Faune d’Aransas, où hivernent les oiseaux nicheurs du Parc National de Wood Buffalo, les habitats fréquentés par la Grue sont surtout les marais côtiers, les baies peu profondes et les estrans. Ces milieux sont dominés par Distichlis spicata, Batis maritima, Spartina alterniflora, la Salicorne et Borrichia frutescens[1].

Lors de la parade nuptiale, la grue blanche danse et sautille en battant puissamment des ailes et pointe son bec vers le ciel avec des cris rappelant le son du clairon.

La Grue blanche est monotypique. Des analyses de l’ADN démontrent qu’elle est génétiquement associée à la Grue cendrée, la Grue moine, la Grue à cou noir et la Grue du Japon[7],[8].

La grue blanche n'a jamais été très répandue et le nombre d'individus n'a probablement jamais dépassé 1500, mais il n'en restait que 21 en 1941. En avril 2007, il y avait 340 grues blanches à l'état sauvage et 145 individus en captivité.

Un petit groupe expérimental a été introduit dans les Montagnes Rocheuses à l'ouest des États-Unis et un autre groupe de même nature mais sédentaire est établi dans le sud-est en Floride[9].

La reproduction en captivité, l'aide à la migration et la loi sur les espèces en danger ont sauvé la grue blanche. Mais le développement humain le long de ses routes migratoires et la réduction de la diversité génétique depuis la précédente chute de population restent problématiques.

Le bai he quan ou « boxe de la grue blanche » est un art martial chinois traditionnel. Les techniques de cet art martial sont inspirés des mouvements de la grue ; des attaques en pique des doigts imitant les coups de bec, des postures sur une seule jambe, des techniques des bras rappelant les battements d'aile[10].

La grue blanche symbolise le calme (yin), la pureté et la loyauté.

Grus americana

La Grue blanche (Grus americana) est un échassier et le plus grand oiseau d'Amérique du Nord, appartenant à la famille des Gruidae. Cette espèce est en voie de disparition (leur nombre a décru de manière dramatique à partir du milieu du XIXe siècle : les pionniers asséchaient les zones humides pour les cultiver et chassaient les grues pour leur viande), mais fait l'objet de plusieurs programmes de protection et de conservation des gouvernements du Canada et des États-Unis : 200 individus survivants en octobre 2005, 340 en liberté au printemps 2007. Le recensement annuel de février 2010 fait état de 263 grues en liberté. On la trouve notamment dans les marais de l'Aransas National Wildlife Refuge et du parc national de Wood Buffalo.

La gru americana (Grus americana (Linnaeus, 1758)) è un uccello della famiglia dei Gruidi, originaria del Nordamerica; per il grido sonoro che emette viene chiamata anche gru urlatrice.[2] In natura può vivere fino a 22 - 24 anni. Si stima che in libertà ne esistano meno di 400 esemplari[1][3].

Gli adulti di gru americana sono completamente bianchi, con la sommità del capo rossa e il lungo becco appuntito di colore scuro. Gli esemplari immaturi sono marrone chiaro. Quando è in volo, il lungo collo viene tenuto disteso in avanti, mentre le lunghe zampe scure sono tenute stese all'indietro; quello del volo è anche l'unico momento in cui sono visibili le estremità nere delle ali.

La specie misura quasi 1,5 m d'altezza e 2,3 m di apertura alare. I maschi pesano in media 7 kg, mentre le femmine, più piccole, non superano i 6[4]. Gli unici altri uccelli di grandi dimensioni bianchi e dalle zampe lunghe del Nordamerica sono: l'airone bianco maggiore, più basso di 30 centimetri e pesante un settimo della gru americana; l'airone bianco, una forma particolare dell'airone azzurro maggiore endemica della Florida; e la cicogna americana. Tutti e tre questi uccelli, però, sono più piccoli della gru americana del 30%[5].

Le aree utilizzate dalla gru americana per riprodursi sono le torbiere della taiga; l'unica località di nidificazione conosciuta è il cosiddetto «Territorio Estivo della Gru Americana», un'apposita zona situata nel Parco Nazionale di Wood Buffalo dell'Alberta (Canada), e le zone circostanti. Grazie al recente progetto di reintroduzione condotto dalla Whooping Crane Eastern Partnership questo uccello è tornato a nidificare per la prima volta dopo 100 anni nel Rifugio Naturale Nazionale di Necedah, nel Wisconsin centrale (USA). La gru americana nidifica al suolo, solitamente in aree sopraelevate della palude. La femmina depone una o due uova tra la fine d'aprile e metà maggio. Queste, chiazzate e di color verde oliva, misurano 60 x 100 mm e pesano 190 g. Il periodo di incubazione dura 29–35 giorni. Della cova si occupano entrambi i genitori, anche se è la femmina a trascorrere più tempo nelle vicinanze del nido. Quasi sempre, però, ogni stagione sopravvive un unico pulcino. Dopo la nascita i genitori nutrono il piccolo per 6-8 mesi, ma quest'ultimo rimarrà con loro fino a quando non avrà circa un anno di età.

Le gru americane svernano lungo la costa texana del Golfo del Messico (USA), in un'area nei pressi di Corpus Christi, il Rifugio Naturale Nazionale di Aransas, lungo il Lago Sunset a Portland, sulle isole di Matagorda e San José, in alcune zone della Penisola di Lamar e a Welder Point, situato sul lato orientale della Baia di San Antonio[6].

Il Rifugio Naturale Nazionale di Salt Plains, in Oklahoma, costituisce un'importante area di sosta per le gru durante la migrazione e ogni anno vi fa visita il 75% di questi volatili[7][8].

L'attuale rarità della gru americana è una conseguenza della distruzione del suo habitat. Un tempo l'areale di questa specie si estendeva su tutto il Nordamerica centro-occidentale. Nel 1941 ne rimanevano solamente 21. Da allora la popolazione è aumentata, grazie soprattutto agli interventi di conservazione. Nell'aprile del 2007 ve ne erano 340 in natura ed altre 145 in cattività. Ciononostante continua ad essere ancora uno degli uccelli più rari del Nordamerica. Il Servizio della pesca e della fauna selvatica degli Stati Uniti confermò che nel 2007 presso il Rifugio Naturale Nazionale di Aransas vi erano 266 esemplari[9].

La gru americana si nutre camminando in acque basse o nei campi e tastando il suolo con il becco. È onnivora e più leggermente incline a nutrirsi di animali rispetto alle altre gru. Nel suo territorio di svernamento in Texas mangia varie specie di crostacei, molluschi, pesci (come le anguille), bacche, piccoli rettili e piante acquatiche. Tra i potenziali cibi di cui si nutre d'estate vi sono rane, piccoli roditori, piccoli uccelli, pesci, insetti acquatici, gamberi di fiume, bivalvi, chiocciole, tuberi acquatici e bacche. Un'altra fonte di cibo per gli uccelli in migrazione è fornita dai cereali, come frumento e orzo[5].

Tra gli animali che più minacciano le uova e i pulcini ricordiamo l'orso nero americano (Ursus americanus), il ghiottone (Gulo gulo luscus), il lupo grigio (Canis lupus), la volpe rossa (Vulpes vulpes), la lince (Lynx canadensis), l'aquila calva (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) e il corvo imperiale comune (Corvus corax). Gli adulti invece hanno pochi predatori e perfino le aquile non sono in grado di abbatterli. L'unico predatore naturale abbastanza potente e rapido che può uccidere un adulto mentre nidifica è la lince rossa[5].

La gru americana è un relitto del Pleistocene: in quest'epoca geologica infatti aveva un'ampia distribuzione in tutta l'America Settentrionale (eccetto Canada orientale e Nuova Inghilterra). Resti fossili antecedenti all'ultima glaciazione sono stati trovati in California, Idaho e Florida. In tempi preistorici probabilmente l'areale della specie si ridusse notevolmente, ma un vero e proprio collasso si è avuto in tempi storici, soprattutto negli ultimi 100 anni. Questo maestoso uccello viveva in tutta la parte centrale del Nordamerica, da Cape May nel New Jersey al Gran Lago Salato nello Utah, e nidificava in Canada fino al Grande Lago degli Schiavi e alla Baia di Hudson, e negli stati americani di Illinois, Minnesota, Iowa, Nord e Sud Dakota, e probabilmente Nebraska e Montana. Migrava d'inverno principalmente verso la costa del golfo del Messico (Louisiana, Texas e Messico). Lo scienziato Robert Porter Allen stimava che già fra 1860 e 1870 la popolazione di gru americane doveva essere di non più di 1300 - 1400 individui[10]. Ma la diminuzione più drammatica si ebbe fra il 1890 e il 1910, e anche dopo il 1910 il declino continuò, a causa della caccia e soprattutto della crescente difficoltà per le gru di trovare spazi aperti e solitari. Nel 1933 l'intera popolazione di gru americane era ridotta a 30 esemplari, che nel 1937 erano scesi a un drammatico minimo di 14. Risalite a 29 nel 1938, 35 nel 1939, le gru diminuirono nuovamente; nel 1940 erano 31, e nel 1941 solo 23. Fu allora che il Servizio della pesca e della fauna selvatica degli Stati Uniti, il Servizio della natura selvatica del Canada e la National Audubon Society finalmente si misero d'accordo per un ultimo drammatico tentativo di salvare la specie. Circa 20.000 ettari di terreno lungo la costa del Texas, dove le gru americane superstiti svernavano, furono acquistati e protetti. Era nato il Rifugio Naturale Nazionale di Aransas. La protezione della zona di nidificazione non era possibile perché allora la sua dislocazione non era nota. Fu iniziata inoltre una campagna pubblicitaria (che continua tuttora), a seguito della quale la gru americana divenne il simbolo nazionale della conservazione. Già nel 1942 il numero delle gru americane era risalito a 28, e da quell'anno praticamente tutte hanno sempre svernato nel Rifugio di Aransas. Da allora la consistenza della popolazione ha continuato a salire, anche se irregolarmente, e con preoccupanti fluttuazioni: intorno a 30 dal 1943 al 1951, poco più di 20 dal 1952 al 1957, e di nuovo sulla trentina dal 1958 al 1963. Però, malgrado gli intensi studi sulla biologia della gru americana, non si riusciva a scoprire dove andava a nidificare. Fu soltanto nel 1964 che il terreno di nidificazione fu scoperto nell'inaccessibile angolo nord-occidentale del Parco Nazionale di Wood Buffalo nei Territori del Nord-Ovest in Canada. Un'altra piccola popolazione, stanziale, era stata scoperta in Louisiana negli anni trenta, e probabilmente nidificava anche nel Texas orientale. Le nidificazioni in Louisiana continuarono fino al 1939, ma dal 1940 questa popolazione è scomparsa. Una femmina di questo gruppo fu accoppiata con un maschio nello zoo di New Orleans, e nel 1957 covò e allevò i primi due piccoli in cattività, e un altro nel 1958. Per tornare al nucleo principale, nel 1964, finalmente per la prima volta, tutte le gru, che avevano lasciato Aransas in primavera, ritornarono in autunno. Nel 1971 le gru erano aumentate 59 e, dopo una diminuzione a 49 nel 1974, risalivano a 70 nel 1977. Nel 2007, il censimento dello stormo tradizionale che nidifica a Wood Buffalo e sverna ad Aransas ha contato 73 coppie riproduttive[9].

Nel 1967 furono compiuti i primi sforzi per creare uno stormo di gru americane in cattività, nell'eventualità che la specie venisse estirpata in natura. L'obiettivo del piano di recupero della gru americana era quello di creare due popolazioni libere di almeno venticinque coppie riproduttive in aggiunta alla popolazione esistente, così che la specie potesse essere trasferita dall'elenco a rischio di estinzione a quello delle specie semplicemente minacciate. Oggi ci sono due popolazioni riproduttive in cattività: una al Patuxent Wildlife Research Centre nel Maryland e una all'International Crane Foundation (ICF) a Baraboo, Wisconsin.

Dal 1992 a oggi diciotto gru americane sono state trasferite in una struttura a Calgary, in Canada, per crearvi un terzo gruppo di gru in cattività. Attualmente i biologi stanno valutando siti in Canada per reintrodurvi uno stormo migratorio di gru americane verso la fine del primo decennio del Duemila. Grazie a questi sforzi, la popolazione delle gru americane è sopravvissuta e continua a crescere. Il programma di recupero di questa specie di gru a opera del Servizio della Pesca e della Fauna Selvatica degli Stati Uniti ha avuto un successo tale che altri Paesi hanno adottato metodi simili per proteggere altre specie di gru anch'esse minacciate.

La gru americana (Grus americana (Linnaeus, 1758)) è un uccello della famiglia dei Gruidi, originaria del Nordamerica; per il grido sonoro che emette viene chiamata anche gru urlatrice. In natura può vivere fino a 22 - 24 anni. Si stima che in libertà ne esistano meno di 400 esemplari.

Amerikinė gervė (lot. Grus americana, angl. Whooping Crane, vok. Schreikranich) – gervinių (Gruidae) šeimos stambus nykstantis paukštis. Kūnas iki 1,5 m aukščio, išskėsti sparnai iki 2,3 m pločio. Patinų svoris – 7,5, patelių – 6,5 kg. Tai aukščiausias Šiaurės Amerikos paukštis ir vienintelė čia paplitusi rūšis.

Suaugę paukščiai balti. Jie turi raudoną viršugalvį, ilgą kaklą ir ilgą tamsų nusmailėjusį snapą.

Kanadoje išlikusi vienintelė natūrali veisimosi vieta. Lizdą suka ant žemės, ant aukštesnio kauburėlio. Deda 2-3 kiaušinius.

Amerikinė gervė (lot. Grus americana, angl. Whooping Crane, vok. Schreikranich) – gervinių (Gruidae) šeimos stambus nykstantis paukštis. Kūnas iki 1,5 m aukščio, išskėsti sparnai iki 2,3 m pločio. Patinų svoris – 7,5, patelių – 6,5 kg. Tai aukščiausias Šiaurės Amerikos paukštis ir vienintelė čia paplitusi rūšis.

Suaugę paukščiai balti. Jie turi raudoną viršugalvį, ilgą kaklą ir ilgą tamsų nusmailėjusį snapą.

Kanadoje išlikusi vienintelė natūrali veisimosi vieta. Lizdą suka ant žemės, ant aukštesnio kauburėlio. Deda 2-3 kiaušinius.

De trompetkraanvogel (Grus americana) is een zeer zeldzame, met uitsterven bedreigde kraanvogelsoort. Het is de grootste vogelsoort van Noord-Amerika en de enige kraanvogel die alleen in Noord-Amerika voorkomt.

Trompetkraanvogels zijn vernoemd naar het trompetachtige geluid dat ze produceren. Volwassen vogels zijn wit, met een rood voorhoofd en een lange, donkere, puntige snavel. De zwarte vleugelpunten zijn alleen tijdens de vlucht zichtbaar. Juvenielen zijn lichtbruin gekleurd. Het zijn grote vogels, tot 1,5 meter hoog, met een spanwijdte van 2,3 meter. Mannetjes wegen gemiddeld 7,5 kg, vrouwtjes 6,5 kg. Tijdens het vliegen hangen de lange poten achter het lichaam en wordt de nek recht gehouden.

Ze broeden in de moerasachtige draslandgebieden op de prairie en overwinteren in Texas, langs de kust van de Golf van Mexico. Ze bouwen hun nest op de grond en leggen 1 tot 3 eieren, meestal in de periode van midden april tot midden mei. De eieren komen uit na 29 tot 35 dagen. De ouders blijven hun jongen 6 tot 8 maanden voeden, en verbreken de relatie met hun jongen na ongeveer 1 jaar.

Trompetkraanvogels zijn omnivoor en voeden zich met onder meer schelpdieren, weekdieren, vis, bessen, slangen en waterplanten.