mk

имиња во трошки

An Erev maskl gwenn[1] (liester: Ereved maskl gwenn) a zo un evn-mor. Cepphus columba eo e anv skiantel.

Bevañ a ra al labous e norzh ar Meurvor Habask[2].

An Erev maskl gwenn (liester: Ereved maskl gwenn) a zo un evn-mor. Cepphus columba eo e anv skiantel.

El somorgollaire columbí[1] (Cepphus columba) és un ocell marí de la família dels àlcids (Alcidae) que habita al Pacífic Nord i és molt semblant al somorgollaire alablanc de l'Atlàntic.

Pelàgic i costaner. Cria a penya-segats i roques costaneres del Pacífic Septentrional, al nord-est de Sibèria, illes Aleutianes, Alaska i illes Kurils. En hivern arriba cap al sud fins al Japó i Baixa Califòrnia.

El somorgollaire columbí (Cepphus columba) és un ocell marí de la família dels àlcids (Alcidae) que habita al Pacífic Nord i és molt semblant al somorgollaire alablanc de l'Atlàntic.

Aderyn a rhywogaeth o adar yw Gwylog adeinddu (sy'n enw benywaidd; enw lluosog: gwylogod adeinddu) a adnabyddir hefyd gyda'i enw gwyddonol Cepphus columba; yr enw Saesneg arno yw Pigeon guillemot. Mae'n perthyn i deulu'r Carfilod (Lladin: Alcidae) sydd yn urdd y Charadriiformes.[1]

Talfyrir yr enw Lladin yn aml yn C. columba, sef enw'r rhywogaeth.[2]

Fe'i ceir yn aml ar lan y môr.

Mae'r gwylog adeinddu yn perthyn i deulu'r Carfilod (Lladin: Alcidae). Dyma rai o aelodau eraill y teulu:

Rhestr Wicidata:

rhywogaeth enw tacson delwedd Carfil bach Alle alle Carfil bychan Aethia pusilla Carfil Cassin Ptychoramphus aleuticus Carfil Japan Synthliboramphus wumizusume Carfil mwstasiog Aethia pygmaea Carfil rhyncorniog Cerorhinca monocerata Gwylog Uria aalge Gwylog Brünnich Uria lomvia Gwylog ddu Cepphus grylle Gwylog sbectolog Cepphus carbo Llurs Alca torda Pâl Fratercula arctica Pâl corniog Fratercula corniculata Pâl pentusw Fratercula cirrhataAderyn a rhywogaeth o adar yw Gwylog adeinddu (sy'n enw benywaidd; enw lluosog: gwylogod adeinddu) a adnabyddir hefyd gyda'i enw gwyddonol Cepphus columba; yr enw Saesneg arno yw Pigeon guillemot. Mae'n perthyn i deulu'r Carfilod (Lladin: Alcidae) sydd yn urdd y Charadriiformes.

Talfyrir yr enw Lladin yn aml yn C. columba, sef enw'r rhywogaeth.

Fe'i ceir yn aml ar lan y môr.

Alkoun holubí (Cepphus columba) je pták z řádu dlouhokřídlých. Poprvé jej popsal Pallas ve své publikaci v roce 1811. Obecně se rozděluje na několik poddruhů:

Alkoun holubí je malý až středně velký pták s téměř celočerným tělem a nevýrazným pohlavním dimorfismem. Je o něco menší než jeho příbuzný alkoun úzkozobý.Délka jeho těla se pohybuje okolo 38 a 40 cm, rozpětí křídel je dokonce okolo 68 cm. Oproti většině ostatních alek má alkoun holubí poměrně dlouhý zobák černé barvy. Nohy jsou středně dlouhé a krvavě červené. Jarní šat je celočerný, jen na křídlech má široký bílý štít. V létě je to jediná alka s černou spodní stranou a po celý rok má v křídle nápadné, ostře ohraničené bílé pole. Zimní šat je převážně bílý s černými špičkami křídel.

Na rozdíl od ostatních křiklavých alek má alkoun holubí tichý, zpěvný hlas. Zní jako jemné vysoké "íp" a v době jarních námluv se samec ozývá ostrým "ist-ist-ist", přičemž zobáček otvírá hodně zeširoka, takže je vidět oranžově žlutá barva jícnu.

Cirkumpolární druh rozšířený v chladných a studených oblastech moří. Evropská hnízdiště zasahují od irského pobřeží na jihu až na severské ostrovy na okraji plovoucího ledu, kde teplota vody ani v létě nevystupuje nad 0 °C. Alkoun holubí není pták volného moře, dává přednost pásmům tiché vody mezi ptačími ostrovy, ve fjordech a vyhledává mělké části moře. V takových místech se zdržuje po celý rok. Na ptačích útesech se usazuje na suťových kuželech při patě skalních stěn. Někdy najdeme čisté kolonie alkounů holubích na neobydlených ostrůvcích štěrkem nebo oblázky. U nás v ČR se alkoun holubí neobjevuje ani jako zatoulanec.

Tento alkoun vytváří jen malé kolonie o tuctu párů, nebo dokonce hnízdí osaměle na úpatí ptačích hor. Na rozdíl od jiných alek klade samička dvě vejce, ale obyčejně stejně odchová jen jedno mládě. Hnědavá, tmavě skvrnitá vejce klade do štěrbin skal nebo dutin pod kameny v červnu a červenci. Hnízdící ptáci sedí tak pevně, že je možné je vzít do ruky. Mladí alkouni v šedivém prachovém šatě a zůstávají v důlku 35 až 39 dní, tedy mnohem déle než jejich příbuzní hnízdící na holých skalách. Když hnízdo opouštějí, dovedou dobře létat a jsou samostatní.

Alkouni holubí hledají potravu převážně na dně moře, jsou to totiž dobří potápěči. Svá mláďata krmí také převážně malými rybkami, dospělí však loví především různé korýše, mořské červy, měkkýše a polypy. Ryby jsou pro dospělé ptáky spíše jen zákuskem.

Alkoun holubí (Cepphus columba) je pták z řádu dlouhokřídlých. Poprvé jej popsal Pallas ve své publikaci v roce 1811. Obecně se rozděluje na několik poddruhů:

Cepphus columba columba Cepphus columba eureka Cepphus columba kaiurka Cepphus columba snowi – alkoun holubí SnowůvDie Taubenteiste (Cepphus columba) ist eine mittelgroße Art aus der Familie der Alkenvögel, deren Verbreitungsgebiet der Norden des Pazifiks ist. Sie ähnelt stark den anderen Arten der Gattung Cepphus, vor allem der atlantischen Gryllteiste, die allerdings etwas größer ist. In ihrem Verbreitungsgebiet ist die Taubenteiste auf Grund der weißen Flügelflecken und der leuchtend roten Füße einer der am einfachsten zu identifizierenden Seevögel.

Es werden insgesamt fünf Unterarten für diese Art beschrieben, die sich in Körpergröße und -gewicht zum Teil erheblich unterscheiden.

Taubenteisten weisen je nach ihrer geographischen Verbreitung erhebliche Unterschiede in Körpergröße und Gewicht auf. Das durchschnittliche Gewicht variiert zwischen 417 und 524 Gramm, wobei die Unterart C. c. snowi die leichteste und C. c. kaiurka die schwerste Unterart ist. Die Flügellänge variiert zwischen 17,9 und 19,7 Zentimeter.[1]

Erwachsene Vögel haben ein schwarzbraunes Gefieder mit einem auffälligen weißen Fleck auf den Flügeln. Der dunkle Schnabel ist dünn und die Beine sowie die Füße sind rot. Im Winter ist die Oberseite grauschwarz gefärbt und die Unterseite weiß. Taubenteisten können gut laufen und haben an Land eine aufrechte Position. Der Schnabel ist lang und schlank, Ober- und Unterschnabel sind fast symmetrisch und dolchähnlich geformt. Die Iris kontrastiert kaum gegenüber dem dunklen Gefieder, bei einigen Individuen ist jedoch ein heller Augenring erkennbar.[2]

Die Taubenteiste brütet in kleineren Kolonien auf felsigen Inseln und Klippen des nördlichen Pazifiks. Die Vorkommen erstrecken sich von Kamtschatka bis nach Nordamerika und dort entlang der Küste von Alaska bis nach Kalifornien. Im Winter ziehen die Taubenteisten von Alaska zu eisfreien Meereszonen im Süden. Kalifornische Vögel ziehen dagegen nach Norden in das Gebiet von British Columbia.

Taubenteisten suchen ihre Nahrung in der Nähe der Küsten in flachen Gewässerzonen mit einem Bewuchs von Unterwasserpflanzen. Bei ihrer Nahrungssuche halten sie sich ungefähr in einem Umkreis von zehn Kilometern von ihrer Brutkolonie auf.

Bei der Nahrungssuche starten Taubenteisten ihre Tauchgänge von der Wasseroberfläche. Sie bleiben dabei in den oberen Wasserschichten und fangen Fische, Krebstiere und andere Meerestiere. Die maximale, bisher festgestellte Tauchtiefe ist 30 Meter, sie bevorzugen jedoch Gewässer mit einer Tiefe von 10 bis 20 Metern.[3]

Wie die anderen Arten der Gattung und im Unterschied zu den meisten anderen Alkenvögeln legt die Taubenteiste zwei Eier. Dies steht vermutlich im Zusammenhang damit, dass die Nahrungssuche in der Nähe der Brutkolonie erfolgt, was ihnen aufgrund kurzer Wege ermöglicht, ausreichend Futter für zwei Nestlinge herbeizuschaffen.[4] Die Brutkolonien finden sich auf Inseln und Landzungen mit einem ausreichenden Angebot an Felsnischen und felsigem Strand sowie in der Nähe befindlichen Flachwasserzonen mit felsigem Bodengrund. Dort wo Raubsäugetiere wie Ratten, Füchse, Minks oder Waschbären vorkommen, finden sich die Brutkolonien nur an unzugänglichen Klippen. Die Taubenteiste ist ein Kolonienbrüter, allerdings sind die Kolonien grundsätzlich sehr klein und umfassen in der Regel ein Dutzend bis zu hundert Brutpaare. Größere Kolonien sind selten.[4] Die Art ist sehr brutplatztreu und nutzt ihre Bruthöhle mehrfach. Damit verbunden ist auch eine hohe Partnertreue.[5]

Als Niststandort werden Felsnischen genutzt, wobei diese in der Regel eine solche Tiefe haben, dass der brütende Vogel von außen nicht mehr sichtbar ist. Die Eier werden in eine flache, mit kleinen Kieseln ausgelegte Mulde auf den Boden gelegt. Taubenteisten graben mitunter aber auch Bruthöhlen oder nutzen Höhlen unter Baumwurzeln oder die verlassenen Baue anderer Seevögel oder Kaninchen. Zu den ungewöhnlicheren Neststandorten der Taubenteiste zählen kleine Höhlungen unter Schiffanlagestellen, Brücken und Schiffswracks. Nester wurden auch bereits in nicht mehr genutzten Gebäuden gefunden. Der Niststandort liegt in der Regel nicht mehr als 30 Meter von der Wasserlinie entfernt.

Der Beginn der Brutzeit variiert in Abhängigkeit von den jeweiligen Umweltbedingungen um bis zu einem Monat. Gewöhnlich beginnen die Brutvögel in Kalifornien, Oregon und Washington in der ersten Maihälfte mit dem Brutgeschäft. In British Columbia dagegen ist der Legebeginn in der zweiten Maihälfte bis zu Beginn des Juli. Taubenteisten halten sich bereits 40 Tage vor Legebeginn vermehrt in der Kolonie auf. Beide Elternvögel brüten und weisen einen Brutfleck auf, der groß genug ist, um beide Eier zu bedecken. Die beiden Nestlinge schlüpfen gewöhnlich in einem Abstand von einem bis zwei Tagen, ihr Schlupfgewicht beträgt durchschnittlich 43,7 Gramm. Sie werden von jeweils einem Elternvogel ununterbrochen mindestens bis zu ihrem dritten, in der Regel aber bis zu ihrem siebten Lebenstag gehudert. Die Nestlingsnahrung ist von Beginn an Fisch, der von den Nestlingen unzerteilt gefressen wird. Die adulten Vögel bringen jeweils einen einzelnen Fisch zum Nest, den sie meist quer im Schnabel tragen. Die Elternvögel tragen während des Tages pro Stunde und Nest statistisch zwischen 0,7 und 1,9 Fische heran.[6]

Die Nestlingszeit beträgt durchschnittlich 38 Tage und variiert zwischen 30 und 53 Tagen. Die Jungvögel wiegen zwischen 300 und 400 Gramm, wenn sie ihr Nest verlassen. Das Wasser erreichen sie entweder laufend oder flatternd. Es gibt bislang keine Belege, dass die Elternvögel ihren Nachwuchs nach dem Verlassen des Nests weiter betreuen. Im Durchschnitt wird ein Jungvogel pro Brutpaar und Jahr flügge.[6]

Zu den wesentlichen Fressfeinden zählen Ratten, die Eier und Nestlinge fressen. Der Nordamerikanische Fischotter (Lutra canadensis) sucht regelmäßig einzelne Brutkolonien auf. Zu den Prädatoren zählen außerdem Waschbären und der Große Schwertwal. Westmöwen, Beringmöwen, Virginia-Uhus, Weißkopfseeadler, Wanderfalken und Sundkrähen sind weitere Fressfeinde.[6]

Von 100 ausgewachsenen Taubenteisten sterben pro Jahr 20. Die mittlere erwartete Lebensspanne beträgt sechs Jahre. Der älteste, bisher gefundene Ringvogel hatte ein Alter von 14 Jahren.[5]

Der Bestand an Taubenteisten gilt als stabil, allerdings gibt es nur wenige Daten zur Bestandsentwicklung dieser Art.[7] Der Gesamtbestand brütet in hunderten kleinen Kolonien in einem sehr großen Verbreitungsgebiet, so dass Bestandsaufnahmen schwierig sind und für einige Gebiete vollständig fehlen. An der russischen Küste brüten vermutlich mehrere zehntausend von Taubenteisten. Der Bestand der in Alaska brütenden Taubenteisten wurde vom United States Fish and Wildlife Service im Jahr 1993 auf 200.000 geschätzt. British Columbia weist 10.200, Washington 6.000, Oregon 3.500 und Kalifornien 15.470 Taubenteisten auf.[7] Die größte Brutkolonie befindet sich auf einer der kalifornischen Farallon-Inseln. Zu den Gefährdungsursachen gehört unter anderem die Ölverschmutzung des Meeres, so waren die Taubenteisten beispielsweise vom Unfall des Supertankers „Exxon Valdez“ im Jahre 1989 betroffen. Da Taubenteisten jedoch auf zahlreiche kleine Kolonien verteilt sind, ist die Auswirkung solcher Katastrophen auf den Gesamtbestand nicht sehr hoch.[8] Negative Auswirkungen hat die Einführung von Raubsäugetieren. So wurde beispielsweise auf den Aleuten der Polarfuchs zu Zwecken der Pelzzucht ausgesetzt, der die bodenbrütenden Taubenteisten gefährdet. In British Columbia stellt die Arealausdehnung von Waschbären für diese Art eine Gefahr dar.[9]

Es werden folgende Unterarten der Taubenteiste unterschieden:

Die Körpergröße der Unterarten nimmt von Kalifornien bis zu den Aleuten kontinuierlich ab.

Die Taubenteiste (Cepphus columba) ist eine mittelgroße Art aus der Familie der Alkenvögel, deren Verbreitungsgebiet der Norden des Pazifiks ist. Sie ähnelt stark den anderen Arten der Gattung Cepphus, vor allem der atlantischen Gryllteiste, die allerdings etwas größer ist. In ihrem Verbreitungsgebiet ist die Taubenteiste auf Grund der weißen Flügelflecken und der leuchtend roten Füße einer der am einfachsten zu identifizierenden Seevögel.

Es werden insgesamt fünf Unterarten für diese Art beschrieben, die sich in Körpergröße und -gewicht zum Teil erheblich unterscheiden.

Tyynenmerenčiistikky (Cepphus columba) on lindu.

The pigeon guillemot (Cepphus columba) (/ˈɡɪlɪmɒt/) is a species of bird in the auk family, Alcidae. One of three species in the genus Cepphus, it is most closely related to the spectacled guillemot. There are five subspecies of the pigeon guillemot; all subspecies, when in breeding plumage, are dark brown with a black iridescent sheen and a distinctive wing patch broken by a brown-black wedge. Its non-breeding plumage has mottled grey and black upperparts and white underparts. The long bill is black, as are the claws. The legs, feet, and inside of the mouth are red. It closely resembles the black guillemot, which is slightly smaller and lacks the dark wing wedge present in the pigeon guillemot.

This seabird is found on North Pacific coastal waters, from Siberia through Alaska to California. The pigeon guillemot breeds and sometimes roosts on rocky shores, cliffs, and islands close to shallow water. In the winter, some birds move slightly south in the northernmost part of their range in response to advancing ice and migrate slightly north in the southern part of their range, generally preferring more sheltered areas.

This species feeds on small fish and marine invertebrates, mostly near the sea floor, that it catches by pursuit diving. Pigeon guillemots are monogamous breeders, nesting in small colonies close to the shore. They defend small territories around a nesting cavity, in which they lay one or two eggs. Both parents incubate the eggs and feed the chicks. After leaving the nest the young bird is completely independent of its parents. Several birds and other animals prey on the eggs and chicks.

The pigeon guillemot is considered to be a least concern species by the International Union for Conservation of Nature due to its large, stable population and wide range. Threats to this bird include climate change, introduced mammalian predators, and oil spills.

The pigeon guillemot is one of three species of auk in the genus Cepphus, the other two being the black guillemot of the Atlantic Ocean and the spectacled guillemot from the Eastern Pacific. It was described in 1811 by Peter Simon Pallas in the second volume of his Zoographia Rosso-Asiatica.[2] A 1996 study looking at the mitochondrial DNA of the auk family found that the genus Cepphus is most closely related to the murrelets from the genus Synthliboramphus.[3] An alternative arrangement, proposed in 2001 using genetic and morphological comparisons, found them as a sister clade to the murres, razorbill, little auk and great auk.[4] Within the genus, the pigeon guillemot and spectacled guillemot are sister species, and the black guillemot is basal within the genus.[3][4] The pigeon guillemot and the black guillemot form a superspecies.[a][5]

CepphusPigeon guillemot

Cladogram showing the relationship of the pigeon guillemot. Based on Friesen (1996).[3]There are five recognised subspecies of the pigeon guillemot:[6]

In the binomial name, the genus, Cepphus, is derived from the Greek kepphos, referring to an unknown pale waterbird mentioned by Aristotle among other classical writers, later variously identified as types of seabirds, including gulls, auks and gannets. The specific epithet, columba, is derived both from the Icelandic klumba, meaning "auk", and the Latin columba, meaning "pigeon". Pallas noted in his description of this species that the common name for the related black guillemot was Greenland dove. Snowi is dedicated to Captain Henry James Snow, a British seaman and hunter. The name of the subspecies kaiurka is derived from the Russian kachurka, meaning "petrel". Adiantus is derived from the Greek adiantos, "unwetted". The trinomial epithet of the subspecies C. c. eureka is from the motto of the state of California, which is derived from the Greek heurēka, meaning "I have found it".[7]

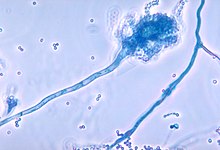

The pigeon guillemot is a medium-sized auk, 30 to 37 cm (12 to 15 in) in length and weighing 450 to 550 g (16 to 19 oz). Both sexes are alike in appearance and mass, except for Californian birds where females were found to have larger bills than males. The summer or breeding plumage of the adult is mostly dark brown with a black sheen, with a white wing patch broken by a brown-black wedge. In winter, the upperparts are iridescent black, often with black fringes giving a scalloped appearance, and the underparts and rump are white. The forehead, crown, lores, eye line and ear coverts are black with white tips, sometimes the tips are narrow and the head looks black.[8] In all plumages, the underwings are plain and dark.[9] Adults moult into their winter or non-breeding plumage between August and October, taking around a month to complete and leaving the bird unable to fly for around four weeks. Birds moult into their breeding plumage between January and March. The legs and feet are red, with black claws. The iris is brown and the eye is surrounded by a thin unbroken white eye-ring. The bill is long and black and the inside of the mouth is red.[8]

The juvenile pigeon guillemot resembles a winter adult but has underpart feathers tipped in brown, giving the appearance of barring, more brown feathers in the upperparts and its wing patch is smaller. Its legs are a grey-brown in color. It loses the brown underpart feathers after its first moult two to three months after fledging. Its moult to its first summer plumage is later than adults, happening between March and May, and first summer birds lack the glossy sheen of adults.[8]

The differences between the subspecies are based on body measurements such as the culmen and wing length. These are larger in southern subspecies and smaller further north. The amount of white on the outer primaries and underwing coverts increases in northern subspecies, except for Cepphus columba snowi, where the white is reduced or entirely absent.[6]

The pigeon guillemot walks well and habitually has an upright posture. When sitting it frequently rests on its tarsi.[8] The wings of the pigeon guillemot are shorter and rounder than other auks, reflecting greater adaptation towards diving than flying. It has difficulty taking off in calm conditions without a runway, but once in the air it is faster than the black guillemot, having been recorded at 77 km/h (48 mph), about 20 km/h (12 mph) faster than the black guillemot.[8] In the water it is a strong swimmer on the surface using its feet.[8] When diving, propulsion is provided both by the wings, which beat at a rate of 2.1/s, but unusually for auks also by the feet.[10] Pigeon guillemots have been recorded travelling 75 m (246 ft) horizontally on dives.[11]

The pigeon guillemot is similar to the related black guillemot, but can be distinguished by its larger size, and in the breeding season by its dusky-grey underwing and the dark brown wedge on the white wing patch.[8]

The pigeon guillemot ranges across the Northern Pacific, from the Kuril Islands and the Kamchatka Peninsula in Siberia to coasts in western North America from Alaska to California. This bird's wintering range is more restricted than its breeding season range, the pigeon guillemot usually wintering at sea or on the coasts, from the Pribilof and Aleutian Islands to Hokkaido and southern California. In Alaska, some migrate south because of advancing sea-ice, although others remain in ice leads or ice holes some distance from the edge of the ice sheet. Further south, birds banded in the Farallon Islands in central California have been recorded moving north, as far as Oregon and even British Columbia.[8] It generally is philopatric, meaning it returns to the colony where it hatched to breed,[12] but it sometimes moves long distances after fledging before settling, for example a chick ringed in the Farallones was recorded breeding in British Columbia.[8]

This bird's breeding habitats are rocky shores, cliffs, and islands close to shallow water less than 50 m (160 ft) deep. It is flexible about its breeding site location, the important factor being protection from predators, and it is more commonly found breeding on offshore islands than coastal sea cliffs. In the winter it forages along rocky coasts, often in sheltered coves. Sandy-bottomed water is avoided, presumably because this does not provide the right habitat to feed in. It occasionally can be found further offshore, as far as the continental shelf break.[8] In the Bering Sea and Alaska, it feeds in openings in ice sheets.[6]

Pigeon guillemots are generally diurnal, but have been recorded feeding before dawn and after sunset. They typically sleep in loose groups in sheltered waters or on shore close to water. They typically rest spaced apart, but mated pairs rest close together. Bathing and preening can also happen on shore or at sea.[8]

The pigeon guillemot usually lays its eggs in rocky cavities near water, but it often nests in any available cavity, including caves, disused burrows of other seabirds, and even old bomb casings.[13] It is noted that pigeon guillemots do not inhabit nests with gull eggs, specifically those of the western gull.[14] This guillemot usually retains its nest site, meaning that nest sites are generally used multiple times, although it does not display this behaviour if its mate does not return to breed.[12] The nests are found at a wide range of heights, from about 1 to 55 m (3.3 to 180.4 ft) above sea-level.[5] Nesting sites are defended by established pairs, as is a small territory around the nest entrance of between 1–4 m2 (11–43 sq ft). Both sexes defend the nesting site, although most defence is done by the male.[8]

Foreign eggs in this guillemot's nest are generally removed. Nest competition with Cassin's auklet is occasional, the pigeon guillemot almost always just removing the eggs, and rarely pithing before removal.[14] On the other hand, larger auk species, tufted puffins and rhinoceros auklets, have been reported evicting pigeon guillemots from their nesting crevices.[12]

This guillemot nests at a variety of densities, ranging from a single individual to dense colonies. The nesting density is generally not affected by predation, although on a very local scale, nesting closer to neighbors has a slight advantage.[15] Colonies are attended during the day and, except for birds incubating or brooding, adults do not remain in the colony at night. Birds usually arrive in the colony in the morning, with counts decreasing after early afternoon, when high tide is. Colony attendance is affected by the tide, more appearing when the tide is higher and less when the tide is lower, probably because the prey this bird feeds on is more accessible during low tide, thus more birds are away from the colony. The counts vary the most before laying, while they are relatively stable during incubation and egg laying.[16]

Pigeon guillemots form long-term pair bonds, the pairs usually reuniting each year, although occasionally pairs divorce.[8] The formation of the pair bond is poorly understood. It is thought that form of play known as "water games", which involves chasing of birds on and under the water at sea, and duet-trilling may have a function in maintaining the pair bond or act as a prelude to copulation.[8][17] The red colour of the mouth may also be a sexual signal.[8]

Usually arriving at its breeding range 40 to 50 days before laying starts,[6] the pigeon guillemot breeds from late April to September.[8] During this time, it generally lays a clutch of one or two eggs. The eggs have grey and brown blotches near the larger end of the egg and range in colour from creamy to pale blue-green.[13] They measure 61.2 mm × 41.0 mm (2.41 in × 1.61 in) on average, but become longer when laid later in the breeding season. Incubated by both sexes, the eggs usually hatch after 26 to 32 days.[13] The chick is brooded continuously by both parents for three days, and then at intervals for another two to four days, after which it is able to control its own body temperature. Both parents are responsible for feeding the chicks, and bring single fish held in the bill throughout the day, but most frequently in the morning.[8]

The chicks usually fledge 34 to 42 days after hatching,[18] although the time taken to fledge has been known to take anywhere from 29 to 54 days.[8] Chicks fledge by leaving the colony and flying to sea, after which they are independent of their parents and receive no post-fledging care.[6] After this, the adult also leaves the colony.[18] Young birds do not breed until at least three years after fledging,[12] with most first breeding at four years of age.[6] While they may not return to breed, two or three year old birds may start attending the breeding colony before they reach sexual maturity, arriving in the colony after the breeding birds. Pigeon guillemots that reach adulthood have an average life-expectancy of 4.5 years, and the oldest recorded individual lived for 14 years.[8]

The pigeon guillemot is a very vocal bird, particularly during the breeding season,[6] and makes several calls, some of which are paired with displays, to communicate with others of its kind. One such display call pairing is the conspicuous hunch-whistle, where the tail is slightly raised, the wings held slightly out and the head thrown back 45-90° while whistling, before snapping back to horizontal.[19] The function of this call is to advertise ownership of a territory. Another call, the trill, denotes ownership over larger distances. Trills can be performed singly or as duets between pairs; if performed as a duet then the call also functions to help reinforce pair bond.[17] Trills are usually given from a resting position, except for the trill-waggle, which has the bird raising its tail, opening its wings and ruffling the feathers of its neck and head, followed by a waggling of its outstretched neck and head.[19] This display is antagonistic in a context where pigeon guillemots are in a group and often is the precursor to an attack.[17] Low whistles are made by unpaired males attempting to attract a mate, and are deeper than hunch-whistles and involve less movement of the head.[19] Other calls made include seeps and cheeps made between mates and screams made in the presence of predators.[17]

The pigeon guillemot forages by itself or in small groups, diving underwater for food, usually close to shore[20] and during the breeding season within 1 km (0.6 mi) of the colony.[6] It forages at depths from 6 to 45 m (20 to 148 ft), but it prefers depths between 15 and 20 m (50 and 70 ft). The dives can range from 10 to 144 seconds,[8] and usually average 87 seconds, with an intermission between dives lasting around 98 seconds.[21] Dives of two to ten seconds are typical when feeding on shoals of sandlance at the water's surface.[8] Smaller prey are probably consumed underwater, but larger organisms are brought to the surface to eat after capture.[8]

The pigeon guillemot mostly feeds on benthic prey found at the lowest level in a body of water close to the sea floor, but it also takes some prey from higher in the water column. It mainly eats fish and other aquatic animals. Fish taken include sculpins, sandfish, cod, and capelin; invertebrates include shrimp and crabs like the pygmy rock crab, and even rarely polychaete worms, gastropods, bivalves and squid. The diet varies greatly, based on where the individual bird is, the season, and also from year to year, as ocean conditions change prey availability. For example, invertebrates are more commonly taken in winter.[8] The foraging method used by this species differs from that of auks in other genera. It hangs upside down above the seafloor, probing with its head for prey and using its feet and wings to maintain position.[10] The chick's diet varies slightly, with more fish than invertebrates, particularly rockfish (family Sebastidae).[13] Specialization in the prey taken by a pigeon guillemot when foraging for its chicks generally results in greater reproductive success, with a high-lipid diet allowing for more growth.[20]

The adult pigeon guillemot requires about 20% of its own weight, or 90 grams (3.2 oz) of food each day. It doubles its rate of fishing when feeding the nestlings. As the nestlings get older, they are fed more, until 11 days after hatching, when the food generally levels out. The food they get, although, starts to decrease about 30 days after hatching.[22]

Avian predation is the most common cause of egg loss in the pigeon guillemot. Species that prey on the nests include the northwestern crow, a common predator of both eggs and chicks, as well as glaucous-winged gulls, stoats and garter snakes.[8] Raccoons are also common predators, preying on eggs, chicks, and adults.[16] Adults are sometimes hunted by bald eagles, peregrine falcons, great horned owls[8] and northern goshawks.[23] In the water, they have been reported to be taken by orca and giant Pacific octopuses.[8]

This bird, especially its chicks, is vulnerable to Aspergillus fumigatus, a fungal disease, while in captivity.[24] It is also vulnerable to the cestode Alcataenia campylacantha.[25] Ticks (Ixodes uriae) and fleas (Ceratophyllus) have been recorded on chicks as well.[8]

The pigeon guillemot is considered to be a least concern species by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. This is due to multiple factors, including its large population, estimated at 470,000 individuals, its stable population, and its large range, as this bird is thought to occur over a range of 15,400,000 km2 (5,950,000 sq mi).[1] This bird is vulnerable to introduced mammalian predators,[6] such as raccoons.[16] The removal of introduced predators from breeding islands allows the species to recover.[26] Climate change has a negative effect on this bird, and reproductive performance decreases with increased temperatures.[27] It is also particularly vulnerable to oil,[6][28] and adults near oiled shores display symptoms of hepatocellular injury, where elevated levels of aspartate aminotransferase can be found in the liver.[29] Otherwise, the effects of oil spills on the pigeon guillemot are unclear.[6][28] Unlike some seabirds, ingestion of plastic does not seem to be a problem for this species.[30]

The pigeon guillemot (Cepphus columba) (/ˈɡɪlɪmɒt/) is a species of bird in the auk family, Alcidae. One of three species in the genus Cepphus, it is most closely related to the spectacled guillemot. There are five subspecies of the pigeon guillemot; all subspecies, when in breeding plumage, are dark brown with a black iridescent sheen and a distinctive wing patch broken by a brown-black wedge. Its non-breeding plumage has mottled grey and black upperparts and white underparts. The long bill is black, as are the claws. The legs, feet, and inside of the mouth are red. It closely resembles the black guillemot, which is slightly smaller and lacks the dark wing wedge present in the pigeon guillemot.

This seabird is found on North Pacific coastal waters, from Siberia through Alaska to California. The pigeon guillemot breeds and sometimes roosts on rocky shores, cliffs, and islands close to shallow water. In the winter, some birds move slightly south in the northernmost part of their range in response to advancing ice and migrate slightly north in the southern part of their range, generally preferring more sheltered areas.

This species feeds on small fish and marine invertebrates, mostly near the sea floor, that it catches by pursuit diving. Pigeon guillemots are monogamous breeders, nesting in small colonies close to the shore. They defend small territories around a nesting cavity, in which they lay one or two eggs. Both parents incubate the eggs and feed the chicks. After leaving the nest the young bird is completely independent of its parents. Several birds and other animals prey on the eggs and chicks.

The pigeon guillemot is considered to be a least concern species by the International Union for Conservation of Nature due to its large, stable population and wide range. Threats to this bird include climate change, introduced mammalian predators, and oil spills.

La Kolomburio (Cepphus columba) estas mezgranda birdo de la familio de la Aŭkedoj kaj Endemismo ĉe la Pacifiko. Ili similaspektas kun la aliaj membroj de la genro Cepphus, ĉefe kun la Nigra urio, kiu estas iomete pli granda.

Plenkreskuloj havas nigrajn korpojn kun blanka granda makulo en centro de supraj flugiloj rompita de flankocentra nigra strio, maldika malhela beko kaj ruĝaj bekinterno, kruroj kaj piedoj. La blanka flugila makulo montriĝas ankaŭ dumfluge sed la flugiloj estas pli nigraj ol tiuj de la Nigra urio. Vintre tiu ĉi specio multege ŝanĝiĝas ĉar la supraj partoj estas punktitaj helgrizaj (ĉefe ĉe krono, malantaŭa kolo, dorso kaj vosto) kaj la subaj partoj estas blankaj; la flugiloj restas nigraj kun la granda blanka makulo kaj la kruroj iom heliĝas. Ambaŭ seksoj estas similaj kaj junuloj aspektas kvazaŭ vintraj plenkreskuloj. Dumfluge videblas la nigra ronda vosto kaj iom elstare la fino de la ruĝaj kruroj; subflugiloj estas blankaj kun nigraj bordoj.

La teritorio de la Kolomburio estas ĉe Norda Pacifiko el duoninsulo Kamĉatko en Siberio ĝis la marbordoj de okcidenta Norda Ameriko el Alasko ĝis Kalifornio. Post la reprodukta sezono la birdoj de Alasko migras suden al malfermaj akvoj, dum kelkaj birdoj el Kalifornio moviĝas norden al la akvo antaŭ Brita Kolumbio. Birdoj kutime revenas al siaj naskiĝkolonioj por reprodukti.

Ili sufiĉe bonepiediras kaj havas rektan staran sintenon.

La reprodukta medio estas rokaj marbordoj, klifoj kaj insuloj plej ofte formante etajn izolitajn koloniojn. La ino demetas la ovojn (du, malkiel plej parto de aŭkedoj) en rokaj truojn proksime de la akvo, kaj ankaŭ en kavernetoj, senuzaj truoj aŭ nestaĵoj de aliaj marbirdoj kaj aliaj lokoj. Ankaŭ malkiel multaj aliaj membroj de la familio de aŭkedoj la Kolomburio estas tagaj bestoj kaj manĝigas la idojn dumtage konstante kaj pro tio kreskas ilin pli rapide ol aliaj samgrandaj aŭkoj, kiuj fiŝkaptas ĉefe dumnokte.

Por preni manĝaĵojn ili plonĝas el la surfaco kaj subnaĝas por kapti bentikajn predojn, kion atingas proksime de marbordo. Ili manĝas ĉefe fiŝojn kaj aliajn akvajn etajn animalojn, ĉefe kotidojn, sablofiŝojn (Trichodon), moruojn, erpelinojn kaj krabojn. La idoj manĝas same, sed pli da fiŝoj ol da aliaj senvertebruloj, ĉefe rokfiŝojn.

La Kolomburio (Cepphus columba) estas mezgranda birdo de la familio de la Aŭkedoj kaj Endemismo ĉe la Pacifiko. Ili similaspektas kun la aliaj membroj de la genro Cepphus, ĉefe kun la Nigra urio, kiu estas iomete pli granda.

El arao colombino, arao paloma o arao pichón (Cepphus columba)[2][3] es una especie de ave caradriforme de la familia de los araos (Alcidae).

Se parecen mucho a los otros miembros del géneros Cepphus, en particular al arao aliblanco (Cepphus grylle), que es ligeramente más pequeño. Las aves adultas tienen el cuerpo negro con una mancha blanca en el ala interrumpida por un trozo negro, pico oscuro y delgadas patas rojas. Son similares en apariencia al arao aliblanco, pero muestran revestimientos oscuros en las alas durante el vuelo. En invierno, las partes superiores son gris jaspeado y negro y las partes inferiores son blancas.

Su hábitat de cría son las costas rocosas, acantilados e islas en el norte a menudo formando pequeñas colonias. Por lo general, ponen sus huevos en cavidades rocosas cerca del agua, pero a menudo anidan en cualquier cavidad disponible, incluyendo cuevas, madrigueras abandonadas de otras aves marinas, incluso antiguas carcasas de bombas. A diferencia de muchos álcidos, los araos colombinos son diurnos y ponen dos huevos. Debido a que pueden alimentar a sus polluelos constantemente durante todo el día, los polluelos abandonan el nido más rápido que las alcas equivalentes en tamaño que sólo se aprovisionan en la noche.

Se distribuye en ampliamente en el Pacífico norte, de la islas Kuriles y la península de Kamchatka en Siberia a las costas del oeste de Norteamérica desde Alaska hasta California. Después de la temporada de cría en Alaska migran hacia el sur hasta las aguas abiertas, mientras que algunas aves desde las aguas de Columbia Británica y hacia norte de California. Las aves generalmente vuelven a su colonia natal para reproducirse. Se zambullen para buscar comida, nadan bajo el agua y se alimentan en la zona béntica. Comen principalmente peces y otros animales acuáticos, en especial escorpeniformes, areneros (Trichodontidae), bacalao, capelán y cangrejos . La dieta de los polluelos varía ligeramente, con más peces que invertebrados, particularmente Sebastidae.

El arao colombino, arao paloma o arao pichón (Cepphus columba) es una especie de ave caradriforme de la familia de los araos (Alcidae).

Kirdekrüüsel (Cepphus columba) on alklaste sugukonda krüüsli perekonda kuuluv lind.

Liik on levinud Vaikse ookeani põhjaosas Kuriilidest ja Kamtšatkalt üle Alaska kuni Californiani. Levila põhjaosas on nad rändlinnud ja lendavad talveks jäävabasse piirkonda. Kalifornia kirdekrüüslid rändavad seevastu põhja, Briti Columbiasse.

Välimuselt sarnaneb kirdekrüüsel väga krüüsliga, aga on veidi suurem. Neil on tume sulestik valge triibuga tiibadel, tume peenike nokk ja punased jalad, millega nad suudavad kiiresti joosta. On täheldatud sulestiku värvimuutust talvel: selg muutub halliks ja mustaks ning kõhuosa valgeks.

Kirdekrüüsel pesitseb kaljusel rannikul, rannakaljudel ja saartel, sageli väikeste kolooniatena. Täiskasvanud kirdekrüüslid pesitsevad üldjuhul seal, kus ise sündisid. Pesad asuvad harilikult väikestes koobastes, lõhedes või vähemalt süvendites. Sageli kasutatakse teiste lindude mahajäetud pesi. Kurnas on 2 muna.

Toitu ei seira nad õhust, nagu teeb enamik merelinde, vaid vees ujudes. Nad püüavad kalu, vähilaadseid ja muid mereloomi, vajadusel vee all ujudes. Tibusid söödavad vanalinnud pigem kala kui selgrootutega. Tibusid toidavad mõlemad vanalinnud erinevalt alkidest ööpäev läbi ja sellepärast kasvavad kirdekrüüslitibud kiiremini kui algitibud, keda toidetakse ainult öösiti.

Majanduslikku tähtsust neil lindudel ei ole. Nende mune ei korjata, sest neid on raske kätte saada, ja ka linde endid ei kütita.

Kirdekrüüsel kuulub soodsas seisundis liikide hulka.

Esimest korda kirjeldas kirdekrüüslit teaduslikult Peter Simon Pallas 1811.

Kirdekrüüsel (Cepphus columba) on alklaste sugukonda krüüsli perekonda kuuluv lind.

Liik on levinud Vaikse ookeani põhjaosas Kuriilidest ja Kamtšatkalt üle Alaska kuni Californiani. Levila põhjaosas on nad rändlinnud ja lendavad talveks jäävabasse piirkonda. Kalifornia kirdekrüüslid rändavad seevastu põhja, Briti Columbiasse.

Välimuselt sarnaneb kirdekrüüsel väga krüüsliga, aga on veidi suurem. Neil on tume sulestik valge triibuga tiibadel, tume peenike nokk ja punased jalad, millega nad suudavad kiiresti joosta. On täheldatud sulestiku värvimuutust talvel: selg muutub halliks ja mustaks ning kõhuosa valgeks.

Kirdekrüüsel pesitseb kaljusel rannikul, rannakaljudel ja saartel, sageli väikeste kolooniatena. Täiskasvanud kirdekrüüslid pesitsevad üldjuhul seal, kus ise sündisid. Pesad asuvad harilikult väikestes koobastes, lõhedes või vähemalt süvendites. Sageli kasutatakse teiste lindude mahajäetud pesi. Kurnas on 2 muna.

Toitu ei seira nad õhust, nagu teeb enamik merelinde, vaid vees ujudes. Nad püüavad kalu, vähilaadseid ja muid mereloomi, vajadusel vee all ujudes. Tibusid söödavad vanalinnud pigem kala kui selgrootutega. Tibusid toidavad mõlemad vanalinnud erinevalt alkidest ööpäev läbi ja sellepärast kasvavad kirdekrüüslitibud kiiremini kui algitibud, keda toidetakse ainult öösiti.

Majanduslikku tähtsust neil lindudel ei ole. Nende mune ei korjata, sest neid on raske kätte saada, ja ka linde endid ei kütita.

Kirdekrüüsel kuulub soodsas seisundis liikide hulka.

Esimest korda kirjeldas kirdekrüüslit teaduslikult Peter Simon Pallas 1811.

Cepphus columba Cepphus generoko animalia da. Hegaztien barruko Alcidae familian sailkatua dago.

Cepphus columba

Le Guillemot colombin (Cepphus columba) est une espèce d'oiseaux marins de la famille des alcidés.

D'après Alan P. Peterson, cette espèce est constituée des trois sous-espèces suivantes :

Cepphus columba

Le Guillemot colombin (Cepphus columba) est une espèce d'oiseaux marins de la famille des alcidés.

L'uria colomba (Cepphus columba, Pallas 1811) è un uccello marino della famiglia degli alcidi.

Cepphus columba ha sei sottospecie:

Questa uria vive nel Pacifico, lungo le coste del Canada, degli Stati Uniti, del Messico, della Russia e del Giappone.

De duifzeekoet (Cepphus columba) is een vogel uit de familie van alken (Alcidae).

Deze soort komt voor aan de noordelijke Pacifische kusten en telt 4 ondersoorten:

Nurnik aleucki (Cepphus columba) – gatunek ptaka z rodziny alk (Alcidae).

Długość ciała 30-35 cm. Cienka szyja, zaokrąglona głowa, długi, ostro zakończony dziób. Na skrzydłach widoczne duże, białe plamy z 1 lub 2 czarnymi klinami. Dziób ciemnoczerwony do czarnego. Wnętrze dzioba oraz nogi jaskrawo - pomarańczowo - czerwone. Upierzenie w szacie godowej czarne. W zimie szare i białe plamki z ciemnym spodem skrzydeł. Obie płci są podobne.

Gniazda zakłada w niszach skalnych od północno-wschodniej Europy i północno-zachodniej części Ameryki Północnej po środkowo-wschodnią Europę i środkowo-zachodnią Amerykę Północną. Zimuje na morzu, na południe od Arktyki.

O airo-columbino (nome científico: Cepphus columba) é um espécie de ave da família dos alcídeos encontrada na costa do Oceano Pacífico.[1][2]

O airo-columbino varia do Pacífico Norte, das Ilhas Curilas e da Península de Kamchatka, na Sibéria, às costas do oeste da América do Norte, do Alasca à Califórnia. O período de invernada deste pássaro é mais restrito do que o período de reprodução, geralmente invernando no mar ou nas costas, das ilhas Pribilof e Aleutian a Hokkaido e sul da Califórnia. No Alasca, alguns migram para o sul por causa do avanço do gelo marinho, embora outros permaneçam em pistas de gelo ou buracos de gelo a alguma distância da borda do manto de gelo. Mais ao sul, pássaros gravados nas Ilhas Farallon, no centro da Califórnia, foram registrados movendo-se para o norte, até Oregon e até a Colúmbia Britânica. Geralmente é filopátrico, o que significa que retorna à colônia onde nasceu para se reproduzir, mas às vezes se move longas distâncias após a criação antes de se estabelecer, por exemplo, um filhote rodeado nos Farallones foi registrado como reprodutor na Colúmbia Britânica.

Os habitats de criação deste pássaro são margens rochosas, falésias e ilhas próximas a águas rasas com menos de 50 m de profundidade. É flexível quanto à localização do local de reprodução, o fator importante é a proteção contra predadores, e é mais comum encontrar reproduções em ilhas offshore do que em falésias costeiras. No inverno, ela se alimenta ao longo de costas rochosas, geralmente em enseadas abrigadas. A água com fundo de areia é evitada, presumivelmente porque isso não fornece o habitat certo para se alimentar. Ocasionalmente, pode ser encontrada mais longe da costa, até a ruptura da plataforma continental. No mar de Bering e no Alasca, ele se alimenta de aberturas em camadas de gelo.

O airo-columbino (nome científico: Cepphus columba) é um espécie de ave da família dos alcídeos encontrada na costa do Oceano Pacífico.

Beringtejst[2] (Cepphus columba) är en fågel i familjen alkor inom ordningen vadarfåglar som förekommer i norra Stilla havet.[3]

Beringtejsten är en medelstor (30-37 cm), i häckningsdräkt huvudsakligen svart alka med lång och smal näbb, röda ben och vita vingtäckare. Den är mycket lik nära släktingen tobisgrisslan men är något större och har ett svart band i det vita på vingarna i häckningsdräkt. Vidare har den i alla dräkter grå istället för vita vingundersidor. Vinterdräkten är mörkare än motsvarande dräkt hos tobisgrisslan. Populationen i Kurilerna (snowi, se nedan) har endast något vitt i vingen, ibland inget alls, och har ofta en ljusare fläck kring ögat.[4][5]

På häckningsplats är beringtejsten en ljudlig fågel som yttrar olika sorters mycket ljusa, gnissliga eller pipiga visslingar kring boet.[4]

Beringtejst påträffas på både den asiatiska och amerikanska sidan av norra Stilla havet. Den delas in i fem underarter i två grupper med följande utbredning:[3]

Underarten snowi behandlas av vissa som en egen art.[5]

Beringtejsten återfinns utmed klippiga kuster runt norra Stilla havet där den sällan ses långt från land. Den lever av olika sorters bottenlevande fisk och ryggradslösa djur. Ungarna matas oftast med fisk som jagas inom en kilometer från häckningskolonin. Den häckar oftast i små kolonier med under 50 fåglar på klippor och sluttningar, ofta nära grunt vatten mindre än 50 meter djupt. Arten är monogam och platstrogen. Den stannar nära kolonin även utanför häckningstid, även om fåglar i Alaska och Kalifornien flyttar söderut respektive norrut.[6]

Arten har ett stort utbredningsområde och en stor population med stabil utveckling.[1] Utifrån dessa kriterier kategoriserar IUCN arten som livskraftig (LC).[1] Världspopulationen uppskattades 1993 till 235.000 individer.[1]

Fågeln har på svenska även kallats beringstejst.

Beringtejst (Cepphus columba) är en fågel i familjen alkor inom ordningen vadarfåglar som förekommer i norra Stilla havet.

Cepphus columba là một loài chim trong họ Alcidae.[2]

Cepphus columba (Pallas, 1811)

Охранный статусТихоокеанский чистик[1] (лат. Cepphus columba) — морская птица средней величины из семейства чистиковых (Alcidae). Она очень напоминает родственные виды из рода чистиков (Cepphus), прежде всего обыкновенного чистика (Cepphus grylle), который всего лишь несколько крупнее.

У взрослых экземпляров чёрное оперение с белым пятном на крыльях. Тёмный клюв достаточно тонок, а лапы красного цвета. Зимой верхняя часть оперения приобретает сероватый оттенок, а нижняя — белый. Голубиные чистики умеют быстро бегать, а также становиться в почти выпрямленную позицию.

Тихоокеанские чистики гнездятся в небольших колониях на скалистых островах в северной части Тихого океана. Их ареал простирается от Камчатки до Северной Америки, где её можно встретить на всём побережье от Аляски до Калифорнии. Зимой голубиные чистики перелетают из Аляски в свободные ото льда области на юге. Калифорнийские же птицы мигрируют на север в район Британской Колумбии. Как правило, взрослые особи гнездятся там же, где и родились. Свои гнёзда они обычно сооружают в маленьких пещерках или нишах. Часто голубиные чистики используют покинутые гнёзда других морских птиц. В отличие от других видов чистиковых, они откладывают каждый раз по два яйца.

При поиске пищи тихоокеанские чистики ныряют не из воздуха, а с поверхности воды. Они ныряют неглубоко и ловят рыбу, раков и других морских животных.

Тихоокеанский чистик (лат. Cepphus columba) — морская птица средней величины из семейства чистиковых (Alcidae). Она очень напоминает родственные виды из рода чистиков (Cepphus), прежде всего обыкновенного чистика (Cepphus grylle), который всего лишь несколько крупнее.

У взрослых экземпляров чёрное оперение с белым пятном на крыльях. Тёмный клюв достаточно тонок, а лапы красного цвета. Зимой верхняя часть оперения приобретает сероватый оттенок, а нижняя — белый. Голубиные чистики умеют быстро бегать, а также становиться в почти выпрямленную позицию.

Тихоокеанские чистики гнездятся в небольших колониях на скалистых островах в северной части Тихого океана. Их ареал простирается от Камчатки до Северной Америки, где её можно встретить на всём побережье от Аляски до Калифорнии. Зимой голубиные чистики перелетают из Аляски в свободные ото льда области на юге. Калифорнийские же птицы мигрируют на север в район Британской Колумбии. Как правило, взрослые особи гнездятся там же, где и родились. Свои гнёзда они обычно сооружают в маленьких пещерках или нишах. Часто голубиные чистики используют покинутые гнёзда других морских птиц. В отличие от других видов чистиковых, они откладывают каждый раз по два яйца.

При поиске пищи тихоокеанские чистики ныряют не из воздуха, а с поверхности воды. Они ныряют неглубоко и ловят рыбу, раков и других морских животных.

分類 界 : 動物界 Animalia 門 : 脊索動物門 Chordata 亜門 : 脊椎動物亜門 Vertebrata 綱 : 鳥綱 Aves 目 : チドリ目 Charadriiformes 科 : ウミスズメ科 Alcidae 属 : ウミバト属 Cepphus 種 : ウミバト C. columba 学名 Cepphus columba

分類 界 : 動物界 Animalia 門 : 脊索動物門 Chordata 亜門 : 脊椎動物亜門 Vertebrata 綱 : 鳥綱 Aves 目 : チドリ目 Charadriiformes 科 : ウミスズメ科 Alcidae 属 : ウミバト属 Cepphus 種 : ウミバト C. columba 学名 Cepphus columbaウミバト(海鳩、学名:Cepphus columba)は、チドリ目ウミスズメ科に分類される鳥類の一種である。

日本では冬鳥として、主に北日本の海上に少数が渡来する。日本では繁殖の記録はなく、この鳥の夏羽を見ることはない。

体長は35cmほどで、名前通りハトくらいの大きさである。冬羽では頭と背が灰色で、喉から腹と翼の中ほどが白い。夏羽では翼の中ほどを除く全身の羽毛が黒くなる。同じウミバト属のケイマフリと同じく足と口の中が赤く、鳴く時や飛ぶ時によく目立つ。

群れを作る習性はなく、非繁殖期は1羽か数羽で沖合いにいることが多く、姿を見ることは少ない。潜水して魚類や甲殻類などを捕食する。

繁殖期には海岸の岩かげや洞穴で産卵するが、ここでも集団繁殖地(コロニー)をあまり作らない。巣材は使わず地面に直に卵を産む。