zh-TW

在導航的名稱

Perception Channels: tactile ; chemical

Sei whales are listed as CITES appendix 1 from the equator to Antarctica. All other populations are listed as CITES appendix 2. The global population of these whales is estimated at only 57,000. Hunting of these whales by humans has been high since the 1950s. The take of these animals peaked in the 1964-65 season, when 25,454 of these whales were taken. The reported global catch of Sei whales in the 1978-79 season was only 150, showing the dramatic drop in whale populations. Some researchers have concluded that Sei whale populations are rising as a result of decreases in Blue and Fin whale poulations. However, this conclusion must be taken with caution, as actual data are scarce, and the dietary overlap between Sei whales and these other species is not complete.

CITES: appendix i

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: endangered

The current economic importance of this whale is questionable. However, in the past, these large whales provided a great deal of income to the whaling industry. It cannot be stressed enough, however, that the positive economic effects of hunting this animal have been acheived only by large scale decimation of Sei whale populations. By overharvesting the whales, the whaling industry experienced a short term economic gain at a long term cost-- the reduction in the number of whales available for harvest.

The Sei whale obtains food by skimming through the water and catching prey in its baleen plates. These whales feed near the surface of the ocean, swimming on their sides through swarms of prey. An average Sei whale eats about 900 kilograms of copepods, amphipods, euphausiids and small fish every day.

Animal Foods: fish; zooplankton

Primary Diet: planktivore

These whales are found in all oceans and adjoining seas, except polar and tropical regions. These animals occupy temperate and subpolar regions in the summer, but migrate to sub-tropical waters during the winter.

Biogeographic Regions: indian ocean (Native ); atlantic ocean (Native ); pacific ocean (Native )

These pelagic whales are found far from shore.

Aquatic Biomes: coastal

Average lifespan

Status: wild: 70.0 years.

Average lifespan

Status: wild: 74.0 years.

The largest known Sei whale measured 20 meters in length, although most whales are between 12.2 and 15.2 meters long. Of this length, the head and body make up about 13 meters. Males are slightly smaller than females. Sei whales have a relatively slender body with a compressed tail stock that abruptly joins the flukes. The snout is pointed, and the pectoral fins are short. The dorsal fin is sickle shaped and ranges in height from 25 to 61 centimeters.

The body is typically a dark steel gray with irregular white markings ventrally. The ventrum has 38-56 deeps grooves, which may have some feeding function. Each side of the upper part of the mouth contains 300 - 380 ashy-black baleen plates. The fine inner bristles of these plates are whitish.

Other Physical Features: endothermic ; bilateral symmetry

Average mass: 2e+07 g.

During mating season, males and females may form a social unit, but strong data on this issue are lacking.

Mating occurs during the winter months. Sei whales in the Northern Hemishpere mate between November and February, whereas mating in the southern hemisphere occurs between May and July. Gestation lasts from 10 1/2 to 12 months. Females typically give birth to a single calf measuring 450 cm in length. There are reports of rare multiple fetuses. The calf nurses for six or seven months. Young reach sexual maturity at 10 years of age, but do not reach full adult size until they are about 25 years old. Sei whales may live as long as 74 years.

Females typically give birth every other year, but a recent increase in pregnancies has been noted. Researchers think this may be a response to the predation rate. Humans kill a great many whales each year, and this might have effects on their reproductive activity.

Breeding interval: Females typically give birth every other year

Breeding season: Mating occurs during the winter months

Average number of offspring: 1.

Range gestation period: 10.5 to 12 months.

Range weaning age: 6 to 7 months.

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female): 10 years.

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male): 10 years.

Key Reproductive Features: iteroparous ; seasonal breeding ; gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); sexual ; viviparous

Average birth mass: 680000 g.

Average number of offspring: 1.

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male)

Sex: male: 3652 days.

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female)

Sex: female: 3652 days.

Red Sea.

Accidental?

Sei whales (Balaenoptera borealis)are long, slender whales that are more streamlined than the other large whales belonging to the Balaenopteridae family.They are usually between 12 – 16 meters long and weigh in between the ranges of20000 – 25000 kgs.

Little is known about social dynamics and communication structure of sei whales but groups of 2 – 5 animals are usually seen.Groups of thousands can occur when food is abundant and during times of migration. Sei whales typically live in sub-polar and temperate regions in the summer then migrate to sub- tropical waters in winter to breed(May – July).

Sei whales are among the fastest cetaceans, swimming up to 50 km/hr.However, they are not good divers – they rarely dive deeper than300 m.Sei whales also tend to be surface feeders.Like other baleen whales, they skim the water for surfaceplankton, copepods and krill.They also ingest small schooling fish and squid.

TheIUCNlists sei whales as an endangered species.The global population has been reduced by 80% due to commercial whaling in the past. Sei whales are now internationally protected although hunting occurs under a controversial research program conducted byJapan.

For more information on MammalMAP, visit the MammalMAPvirtual museumorblog.

Die seiwalvis (Balaenoptera borealis) is 'n baardwalvis; die derde grootste vinwalvis na die blouwalvis en die rorkwal.[2] Seiwalvisse word in al die wêreld se oseane aangetref en verkies diep waters wat nie te ver van die kus is nie..[3] Hulle is geneigd om poolstreke, tropiese streke en gebiede wat semi-afgeslote is. Seiwalvisse migreer jaarliks van koel en subpoolstreke in die somer na matige en subtropiese waters in die winter. In meeste areas is die presiese migrasieroetes nie baie bekend nie.[4]

Die walvisse bereik 'n lengte van tot 20 m en kan tot 45 ton weeg.[4] Een seiwalvis vreet 'n gemiddelde 900 kg kos per dag, hoofsaaklik eenoogkrefies, planktonkrefies en ander soöplankton. [5] Seiwalvisse word onder die vinnigste van al die walvisagtiges gereken en kan 'n spoed van tot 50 km/h oor kort afstande bereik.[5] Die naam "seiwalvis" is van die Noorse woord vir pollak, 'n soort vis wat om en by dieselfde tyd as die seiwalvis langs die kus van Noorweë verskyn.[6]

As gevolg van grootskaalse kommersiële walvisvangs tussen die laat-negentiende en laat-twintigste eeue, waartydens meer as 238 000 individue gevang is,[7] is die seiwalvis tans 'n internasionaal beskermde spesie,[1] alhoewel beperkte walvisvangs steeds onder omstrede programme deur Ysland en Japan plaasvind.[8] Met die ingang van 2006 was die wêreldwye bevolking van die seiwalvis omtrent 54 000: ongeveer 'n vyfde van wat dit voor die aanvang van walvisvangs was.

|month= geïgnoreer (help) Die seiwalvis (Balaenoptera borealis) is 'n baardwalvis; die derde grootste vinwalvis na die blouwalvis en die rorkwal. Seiwalvisse word in al die wêreld se oseane aangetref en verkies diep waters wat nie te ver van die kus is nie.. Hulle is geneigd om poolstreke, tropiese streke en gebiede wat semi-afgeslote is. Seiwalvisse migreer jaarliks van koel en subpoolstreke in die somer na matige en subtropiese waters in die winter. In meeste areas is die presiese migrasieroetes nie baie bekend nie.

Die walvisse bereik 'n lengte van tot 20 m en kan tot 45 ton weeg. Een seiwalvis vreet 'n gemiddelde 900 kg kos per dag, hoofsaaklik eenoogkrefies, planktonkrefies en ander soöplankton. Seiwalvisse word onder die vinnigste van al die walvisagtiges gereken en kan 'n spoed van tot 50 km/h oor kort afstande bereik. Die naam "seiwalvis" is van die Noorse woord vir pollak, 'n soort vis wat om en by dieselfde tyd as die seiwalvis langs die kus van Noorweë verskyn.

As gevolg van grootskaalse kommersiële walvisvangs tussen die laat-negentiende en laat-twintigste eeue, waartydens meer as 238 000 individue gevang is, is die seiwalvis tans 'n internasionaal beskermde spesie, alhoewel beperkte walvisvangs steeds onder omstrede programme deur Ysland en Japan plaasvind. Met die ingang van 2006 was die wêreldwye bevolking van die seiwalvis omtrent 54 000: ongeveer 'n vyfde van wat dit voor die aanvang van walvisvangs was.

Seyval (lat. Balaenoptera borealis) — Zolaqlı balinalar fəsiləsinə, Bığlı balinalar dəstəsinə aid balina növü. Uzunluğu 20 (erkək) və 17 metr (dişi) arasında dəyişir. Çəkisi 30 tondur.

Bel nahiyyəsi tünd, yan nahiyyələri boz parlaq ləkəli, qarın hissəsi isə bozdan ağ rəngə qədər olur. Bel nahiyyəsindəki üzgəc iridir.

Qidasının əsasını Xərçəngkimilər, balıq sürüləri və Başıayaqlılar təşkil edir.

Yetkinliyə 5—7 yaşlarında çatırlar. Orta ömür müddəti 60 ildir.

Boğazlıq dövrü 10,5 - 12 aydır.

Cütləşmə dövrü aprel-avqust aylarına təsadüf edir. Seyvallar 300 metr fərinliyə üzə bilirlər və su altında 20 dəqiqə qala bilirlər. Onların sürəti 25 km/s təşkil edir. Dünyanın bütün okeanlarında yaşayırlar. Əsasən suyun temperaturu 8-25° S olan ərazilərdə üzürlər. Sahildən bir qədər aralıda, açıq dənizdə yaşayırlar.

Göy balina və Finval ovunun kəskin azalmasından sonra əsas təsərrüfatına çevrilmişdir. 1986-ci ildən ovuna qadağa qoyulmuşdur.

Seyval (lat. Balaenoptera borealis) — Zolaqlı balinalar fəsiləsinə, Bığlı balinalar dəstəsinə aid balina növü. Uzunluğu 20 (erkək) və 17 metr (dişi) arasında dəyişir. Çəkisi 30 tondur.

Balum an hanternoz (Balaenoptera borealis) a zo ur morvil fanoliek.

Tiriad ar balum boutin

Tiriad ar balum boutin El rorqual boreal, rorqual del nord, balena del nord, rorqual de Rudolphi o rorqual de Rudolf[1] (Balaenoptera borealis) és un rorqual de silueta estilizada i grandària mitjana.

A l'hemisferi nord, els mascles fan fins a 16,5 m i les femelles fins a 17,2 m. El pes dels adults oscil·la entre 18 i 25 tones.

El rorqual boreal està amplament distribuït per tots els oceans, encara que no s'endinsa tant en les regions polars com ho fan les altres espècies de rorqual. A l'Atlàntic Nord, l'espècie ocupa les aigües del nord de les Illes Britàniques, Noruega i Islàndia a l'estiu, i a l'hivern es dispersa per una ampla franja que s'estén des de les costes d'Anglaterra fins a Mauritània. Les factories baleneres de la costa atlàntica ibèrica i l'estret de Gibraltar cada any capturaven alguns exemplars d'aquesta espècie.[2]

A la Mediterrània, la presència del rorqual boreal és excepcional i l'única cita fiable d'aquesta espècie fou feta l'any 1973, quan una femella jove (7,3 m de llargada) va aparèixer avarada a la Punta del Fangar, al delta de l'Ebre.[3]

El rorqual boreal realitza moviments estacionals nord-sud semblants als descrits per la balena d'aleta. La seva dieta es fonamenta en petits crustacis copèpodes (Calanus spp.), eufausiacis i amfípodes, tot i que sovint pot alimentar-se també de petits peixos de banc, com anxoves o sorells (Trachurus trachurus).

La reproducció té lloc a l'hivern. La gestació dura uns 10 mesos i mig, al cap dels quals neix un cadell d'uns 4,5 m de llargada corporal. El període de lactància s'estén al llarg de 6 mesos i els cadells són deslletats quan fan uns 9 m.

A l'hemisferi nord, la talla de maduresa sexual és d'uns 13 m.

Els rorquals boreals s'acostumen a trobar formant petits grups de fins a uns 5-7 individus, encara que en les àrees d'alimentació poden veure's agrupacions transitòries molt més grans si l'aliment està concentrat.[4]

El rorqual boreal està protegit pel conveni de Berna (annex III) i es troba catalogat dintre de l'apèndix I del CITES. A la llista vermella de la UICN 2008, aquesta espècie està catalogada com en perill.

La seva excepcionalitat a la Mediterrània l'exclou de patir problemes d'interacció amb les activitats pesqueres o amb els desenvolupaments del litoral.

El rorqual boreal, rorqual del nord, balena del nord, rorqual de Rudolphi o rorqual de Rudolf (Balaenoptera borealis) és un rorqual de silueta estilizada i grandària mitjana.

A l'hemisferi nord, els mascles fan fins a 16,5 m i les femelles fins a 17,2 m. El pes dels adults oscil·la entre 18 i 25 tones.

Mamal sy'n byw yn y môr ac sy'n perthyn i deulu'r Balaenopteridae ydy'r Morfil Asgellog Sei sy'n enw gwrywaidd; lluosog: morfilod asgellog sei (Lladin: Balaenoptera borealis; Saesneg: Sei whale).

Mae ei diriogaeth yn cynnwys Asia, Awstralia, Cefnfor yr Iwerydd, y Cefnfor Tawel, Ewrop a Chefnfor India ac ar adegau mae i'w ganfod ger arfordir Cymru.

Ar restr yr Undeb Rhyngwladol dros Gadwraeth Natur (UICN), caiff y rhywogaeth hon ei rhoi yn y dosbarth 'Mewn Perygl' o ran niferoedd, bygythiad a chadwraeth.[1]

Mamal sy'n byw yn y môr ac sy'n perthyn i deulu'r Balaenopteridae ydy'r Morfil Asgellog Sei sy'n enw gwrywaidd; lluosog: morfilod asgellog sei (Lladin: Balaenoptera borealis; Saesneg: Sei whale).

Mae ei diriogaeth yn cynnwys Asia, Awstralia, Cefnfor yr Iwerydd, y Cefnfor Tawel, Ewrop a Chefnfor India ac ar adegau mae i'w ganfod ger arfordir Cymru.

Ar restr yr Undeb Rhyngwladol dros Gadwraeth Natur (UICN), caiff y rhywogaeth hon ei rhoi yn y dosbarth 'Mewn Perygl' o ran niferoedd, bygythiad a chadwraeth.

Plejtvák sejval (Balaenoptera borealis) je kytovec z podřádu kosticovci. Je to třetí největší plejtvák, hned po plejtváku obrovském a plejtváku myšoku.[zdroj?]

Název „sejval“ pochází z norského slova "seihval" (hval je velryba, sei je treska) podle tresky, která se u norského pobřeží vyskytuje ve stejnou roční dobu jako sejval.[zdroj?]

Plejtvák sejval dorůstá až 20 metrů délky a 45 tun váhy. Denně sní v průměru 900 kilogramů potravy, kterou tvoří klanonožci, korýši a ostatní složky zooplanktonu (viz též kril). Patří mezi nejrychlejší kosticovce, na krátké vzdálenosti je schopen vyvinout rychlost až 50 kilometrů za hodinu.

Žije v mořích a oceánech téměř celého světa. Nejraději se zdržuje při hlubokých pobřežích, zároveň se vyhýbá ohraničeným prostorům jako jsou zátoky. Nepluje do vod arktických či naopak tropických. Plejtvák sejval migruje každý rok na zimu z chladných vod do vod mírného až subtropického pásu. Jejich přesné trasy však povětšinou nejsou dosud známy.

Kvůli rozsáhlému lovu, který probíhal přibližně od konce devatenáctého do konce dvacátého století, kdy bylo uloveno přes 238 000 kusů, je dnes plejtvák sejval mezinárodně chráněn. Přesto však je stále v omezené míře loven v rámci kontroverzního programu vedeného Islandem a Japonskem. K roku 2006 činila populace plejtváka sejvala okolo 54 000, z čehož pětina je určena k lovu.

V tomto článku byl použit překlad textu z článku Sei Whale na anglické Wikipedii.

Plejtvák sejval (Balaenoptera borealis) je kytovec z podřádu kosticovci. Je to třetí největší plejtvák, hned po plejtváku obrovském a plejtváku myšoku.[zdroj?]

Sejhvalen (Balaenoptera borealis) er en bardehval af finhval-familien. Den voksne sejhval bliver 12-16 m lang og vejer 20-30 t, og den er dermed den fjerdestørste af finhvalerne (efter blåhval, finhval og pukkelhval). Sejhvalen findes i alle verdenshave og foretrækker dybt vand langt fra kysterne.[2] Sejhvalen vandrer i lighed med de øvrige bardehvaler mellem polare områder om sommeren til tempererede og subtropiske farvande om vinteren.

Sejhvalen har fået sit navn efter torskefisken sej, der forekommer i store mængder langs Norges kyst på samme tid som sejhvalerne ses. Sejhvalen spiser dog ikke sej, men lever af vandlopper (copepoder), lyskrebs og andet dyreplankton som den filtrerer ud af vandet med sine barder.

Den samlede bestand af sejhval blev i 2008 skønnet til ca. 80.000 dyr, omkring en tredjedel af bestandstørrelsen før den kommercielle fangst på sejhval begyndte.[3][4] Fangst af sejhval er især foregået i første halvdel af 1900-tallet, med en skønnet samlet fangst på over 250.000 sejhvaler.[5][6] Sejhvaler er i dag beskyttet mod jagt gennem hvalfangstkommissionens moratorium på hvalfangst, men en begrænset fangst forgår stadig i Island og Japan.

Sejhvalen (Balaenoptera borealis) er en bardehval af finhval-familien. Den voksne sejhval bliver 12-16 m lang og vejer 20-30 t, og den er dermed den fjerdestørste af finhvalerne (efter blåhval, finhval og pukkelhval). Sejhvalen findes i alle verdenshave og foretrækker dybt vand langt fra kysterne. Sejhvalen vandrer i lighed med de øvrige bardehvaler mellem polare områder om sommeren til tempererede og subtropiske farvande om vinteren.

Sejhvalen har fået sit navn efter torskefisken sej, der forekommer i store mængder langs Norges kyst på samme tid som sejhvalerne ses. Sejhvalen spiser dog ikke sej, men lever af vandlopper (copepoder), lyskrebs og andet dyreplankton som den filtrerer ud af vandet med sine barder.

Den samlede bestand af sejhval blev i 2008 skønnet til ca. 80.000 dyr, omkring en tredjedel af bestandstørrelsen før den kommercielle fangst på sejhval begyndte. Fangst af sejhval er især foregået i første halvdel af 1900-tallet, med en skønnet samlet fangst på over 250.000 sejhvaler. Sejhvaler er i dag beskyttet mod jagt gennem hvalfangstkommissionens moratorium på hvalfangst, men en begrænset fangst forgår stadig i Island og Japan.

Der Seiwal (Balaenoptera borealis) ist eine Walart aus der Familie der Furchenwale (Balaenopteridae). Die Bezeichnung „Sei“ kommt vom norwegischen Wort für Seelachs und stammt daher, dass sich die Tiere zum Teil von diesen Fischen ernähren und in der Nähe von Schwärmen anzutreffen sind.

Seiwale kommen in allen Ozeanen weltweit zwischen 60° nördlicher und 60° südlicher Breite vor. Im Sommer halten sie sich in gemäßigten oder subpolaren Regionen auf, um im Winter in subtropische Meere zu wandern. Nach dem Verbreitungsgebiet werden zwei Unterarten unterschieden, der Nördliche Seiwal (B. b. borealis) und der Südliche Seiwal (B. b. schleglii).

Seiwale gehören zu den Bartenwalen (Mysticeti), die durch 600 bis 680 Barten statt der Zähne im Maul gekennzeichnet sind. Sie erreichen eine Durchschnittslänge von 12 bis 16 Metern und ein Gewicht von rund 20 bis 30 Tonnen, die größten Tiere werden bis zu 20 Meter lang und 45 Tonnen schwer. Sie sind durch einen schlanken, langgezogen wirkenden Körper gekennzeichnet, der an der Oberseite dunkelgrau und an der Unterseite weißlich gefärbt ist. Sie haben eine spitze Schnauze, eine sichelförmige Finne und eine im Vergleich zum übrigen Körper kleine Fluke. Ein Skelett mit Organen ist im Stuttgarter Naturkundemuseum ausgestellt.

Seiwale leben im offenen Meer meist in Paaren oder kleinen Gruppen, größere Schulen finden sich in reichen Nahrungsgründen. Sie sind die schnellsten Schwimmer unter den Furchenwalen und können bis zu 25 Knoten (rund 45 km/h) erreichen. Ihre Tauchgänge sind kurz (fünf bis zehn Minuten) und nicht sehr tief.

Die Nahrung der Seiwale besteht aus Krill und bis zu 30 Zentimeter großen Schwarmfischen, darunter der namensgebende Seelachs. Während der Nahrungsaufnahme schwimmen sie häufig in Seitenlage.

Die Paarung erfolgt in den Wintermonaten (auf der Nordhalbkugel von November bis Februar, auf der Sübhalbkugel von Mai bis Juli), und die Tragzeit beträgt rund 10,5 bis 12 Monate. Seiwalkälber sind bei der Geburt rund vier bis fünf Meter lang und 600 bis 750 Kilogramm schwer. Nach sechs bis sieben Monaten werden die Jungtiere entwöhnt. Obwohl sie die Geschlechtsreife mit rund zehn Jahren erreichen, dauert es bis zu 25 Jahre, bis sie ausgewachsen sind. Ihre Lebenserwartung wird auf bis zu 75 Jahre geschätzt.

Obwohl Seiwale dieselben Gebiete wie Blau-, Finn- und Buckelwale bewohnen, waren sie kein traditionelles Beutetier der Walfänger. Erst als die Bestände der anderen Arten zurückgingen, geriet der Seiwal in das Visier der Walfänger. Im 20. Jahrhundert wurden insbesondere auf der Südhalbkugel mehr als 200.000 Tiere dieser Art erlegt. Seit 1976 ist die Art geschützt, allerdings jagten seither Isländer, Japaner und Norweger eine kleine Anzahl zu Forschungszwecken. Heute geht man von rund 50.000 bis 60.000 lebenden Exemplaren des Seiwals aus, die IUCN listet ihn als stark gefährdet (endangered).

Seit April 2015 wurden vor Patagonien in Chile mehr als 300 tote Seiwale angespült, wobei die tatsächliche Zahl aufgrund der Unzugänglichkeit des Gebietes höher liegen dürfte.[1] Laut einer wissenschaftlichen Untersuchung führte eine giftige Algenblüte, ausgelöst durch das Klimaphänomen El-Niño, zum Tod der Tiere. Die Wissenschaftler sehen in der steigenden Anzahl von Massensterben durch giftige Algenblüten eine Gefahr für die Erhaltung bedrohter Walarten.[2]

Der Seiwal (Balaenoptera borealis) ist eine Walart aus der Familie der Furchenwale (Balaenopteridae). Die Bezeichnung „Sei“ kommt vom norwegischen Wort für Seelachs und stammt daher, dass sich die Tiere zum Teil von diesen Fischen ernähren und in der Nähe von Schwärmen anzutreffen sind.

Sei Hái-ang sī 1 chióng toā-hêng ê chhiu-keng. Sin-khu it-poaⁿ tn̂g 12-16 kong-chhioh (siōng tn̂g kiông beh 20 kong-chhioh), tāng 20-30 kong-tùn (45 kong-tùn--ê oân-ná ū). Goā-hêng chhin-chhiūⁿ Bryde ê Hái-ang. Chhàng-chúi ê pō͘-sò͘ sī siōng khó-khò ê khu-pia̍t pān-hoat.

Sei Hái-ang tī 20 sè-kí tiong-kî bat siū lâng thó-lia̍h, tī Lâm-ke̍k-iûⁿ hit-tah-á sí 20 bān chiah. Bo̍k-chêng sī siū kok-chè pó-hō͘ ê chéng.

Sei sī Norge-gí, chí Pollachius-sio̍k ê hî-á (Eng-gí pollock, coalfish).

Seyval (Balaenoptera borealis) — yoʻl-yoʻl kitlar oilasiga mansub sut emizuvchi. Urgʻochisining uz. 18,8 m gacha. Erkagi kichikroq. Usti toʻq, biqin qismi och kulrang , qorni kulrangdan oqqacha. Qishda urchiydi. Boʻgʻozlik davri bir yilcha. Ikki yilda bir marta bitta, baʼzan ikkita bola tugʻadi. 5—7 yilda jinsiy yetiladi. Arktikadan Antarktikagacha boʻlgan dengizlarda, jumladan, Uzoq Sharq va baʼzan Boltiq dengizlarida uchraydi. Qisqichbaqasimonlar, boshoyoqli mollyuskalar va baliqlar bilan oziqlanadi. Soni kamaymoqda. Ovlash man etilgan.[1]

Seyval (Balaenoptera borealis) — yoʻl-yoʻl kitlar oilasiga mansub sut emizuvchi. Urgʻochisining uz. 18,8 m gacha. Erkagi kichikroq. Usti toʻq, biqin qismi och kulrang , qorni kulrangdan oqqacha. Qishda urchiydi. Boʻgʻozlik davri bir yilcha. Ikki yilda bir marta bitta, baʼzan ikkita bola tugʻadi. 5—7 yilda jinsiy yetiladi. Arktikadan Antarktikagacha boʻlgan dengizlarda, jumladan, Uzoq Sharq va baʼzan Boltiq dengizlarida uchraydi. Qisqichbaqasimonlar, boshoyoqli mollyuskalar va baliqlar bilan oziqlanadi. Soni kamaymoqda. Ovlash man etilgan.

Сэйвал, сайдавы кіт (Balaenoptera borealis) — сысун сямейства паласацікавых падатрада бяззубых кітоў.

Пашыраны ў морах ад Арктыкі да Антарктыкі.

Даўжыня цела дарослых самцоў да 18,8 м, самак да 21 м, маса да 16 т, даўж. нованароджанага 4-5 м. Афарбоўка сьпіны ад сінявата-чорнай да чорна-шараватай, бруха — ад шэрай да белай. Паднябеньне вузкае, белае ці ружовае; па яго баках 300-400 чорных пласьцінаў кітовага вуса вышынёю да 80 см.

Корміцца ракападобнымі, галаваногімі малюскамі, чароднымі рыбамі, напр. сайдай (адсюль другая назва).

Нараджае 1 дзіцяня раз у 2 гады.

Промысел цалкам забаронены з 1986.

The sei whale (/seɪ/ SAY,[4] Norwegian: [sæɪ]; Balaenoptera borealis) is a baleen whale, the third-largest rorqual after the blue whale and the fin whale.[5] It inhabits most oceans and adjoining seas, and prefers deep offshore waters.[6] It avoids polar and tropical waters and semi-enclosed bodies of water. The sei whale migrates annually from cool, subpolar waters in summer to temperate, subtropical waters in winter with a lifespan of 70 years.[7]

Reaching 19.5 m (64 ft) in length and weighing as much as 28 t (28 long tons; 31 short tons),[7] the sei whale consumes an average of 900 kg (2,000 lb) of food every day; its diet consists primarily of copepods, krill, and other zooplankton.[8] It is among the fastest of all cetaceans, and can reach speeds of up to 50 km/h (31 mph) (27 knots) over short distances.[8] The whale's name comes from the Norwegian word for pollock, a fish that appears off the coast of Norway at the same time of the year as the sei whale.[9]

Following large-scale commercial whaling during the late 19th and 20th centuries, when over 255,000 whales were killed,[10][11] the sei whale is now internationally protected.[2] As of 2008, its worldwide population was about 80,000, less than a third of its prewhaling population.[12][13]

Sei is the Norwegian word for pollock, also referred to as coalfish, a close relative of codfish. Sei whales appeared off the coast of Norway at the same time as the pollock, both coming to feed on the abundant plankton.[9] The specific name is the Latin word borealis, meaning northern. In the Pacific, the whale has been called the Japan finner; "finner" was a common term used to refer to rorquals. In Japanese, the whale was called iwashi kujira, or sardine whale, a name originally applied to Bryde's whales by early Japanese whalers. Later, as modern whaling shifted to Sanriku—where both species occur—it was confused for the sei whale. Now the term only applies to the latter species.[14][15] It has also been referred to as the lesser fin whale because it somewhat resembles the fin whale.[16] The American naturalist Roy Chapman Andrews compared the sei whale to the cheetah, because it can swim at great speeds "for a few hundred yards", but it "soon tires if the chase is long" and "does not have the strength and staying power of its larger relatives".[17]

On 21 February 1819, a 32-ft whale stranded near Grömitz, in Schleswig-Holstein. The Swedish-born German naturalist Karl Rudolphi initially identified it as Balaena rostrata (=Balaenoptera acutorostrata). In 1823, the French naturalist Georges Cuvier described and figured Rudolphi's specimen under the name "rorqual du Nord". In 1828, Rene Lesson translated this term into Balaenoptera borealis, basing his designation partly on Cuvier's description of Rudolphi's specimen and partly on a 54-ft female that had stranded on the coast of France the previous year (this was later identified as a juvenile fin whale, Balaenoptera physalus). In 1846, the English zoologist John Edward Gray, ignoring Lesson's designation, named Rudolphi's specimen Balaenoptera laticeps, which others followed.[18] In 1865, the British zoologist William Henry Flower named a 45-ft specimen that had been obtained from Pekalongan, on the north coast of Java, Sibbaldius (Balaenoptera) schlegelii—in 1946 the Russian scientist A.G. Tomilin synonymized S. schlegelii and B. borealis, creating the subspecies B. b. schlegelii and B. b. borealis.[19][20] In 1884–85, the Norwegian scientist G. A. Guldberg first identified the "sejhval" of Finnmark with B. borealis.[21]

Sei whales are rorquals (family Balaenopteridae), baleen whales that include the humpback whale, the blue whale, Bryde's whale, the fin whale, and the minke whale. Rorquals take their name from the Norwegian word røyrkval, meaning "furrow whale",[22] because family members have a series of longitudinal pleats or grooves on the anterior half of their ventral surface. Balaenopterids diverged from the other families of suborder Mysticeti, also called the whalebone whales, as long ago as the middle Miocene.[23] Little is known about when members of the various families in the Mysticeti, including the Balaenopteridae, diverged from each other.

Two subspecies have been identified—the northern sei whale (B. b. borealis) and southern sei whale (B. b. schlegelii).[24]

The sei whale is the third-largest balaenopterid, after the blue whale (up to 180 tonnes, 200 tons) and the fin whale (up to 70 tonnes, 77 tons) but close to the humpback whale.[5] In the North Pacific, adult males average 13.7 m (45 ft) and adult females average 15 m (49 ft), weighing 15 and 18.5 tonnes (16.5 and 20.5 tons),[25] while in the North Atlantic adult males average 14 m (46 ft) and adult females 14.5 m (48 ft), weighing 15.5 and 17 tonnes (17 and 18.5 tons)[25] In the Southern Hemisphere, they average 14.5 (47.5 ft) and 15 m (49 ft), respectively, weighing 17 and 18.5 tonnes (18.5 and 20.5 tons).[25] ([26] In the Northern Hemisphere, males reach up to 17.1 m (56 ft) and females up to 18.6 m (61 ft),[27] while in the Southern Hemisphere males reach 18.6 m (61 ft) and females 19.5 m (64 ft)—the authenticity of an alleged 22 m (72 ft) female caught 50 miles northwest of St. Kilda in July 1911 is doubted.[28][29][30] The largest specimens taken off Iceland were a 16.15 m (53.0 ft) female and a 14.6 m (48 ft) male, while the longest off Nova Scotia were two 15.8 m (52 ft) females and a 15.2 m (50 ft) male.[30][31] The longest measured during JARPN II cruises in the North Pacific were a 16.32 m (53.5 ft) female and a 15 m (49 ft) male.[32][33] The longest measured by Discovery Committee staff were an adult male of 16.15 m (53.0 ft) and an adult female of 17.1 m (56 ft), both caught off South Georgia.[34] Adults usually weigh between 15 and 20 metric tons—a 16.4 m (54 ft) pregnant female caught off Natal in 1966 weighed 37.75 tonnes (41.6 tons), not including 6% for loss of fluids during flensing.[25] Females are considerably larger than males.[7] At birth, a calf typically measures 4.4–4.5 m (14–15 ft) in length.

The whale's body is typically a dark steel grey with irregular light grey to white markings on the ventral surface, or towards the front of the lower body. The whale has a relatively short series of 32–60 pleats or grooves along its ventral surface that extend halfway between the pectoral fins and umbilicus (in other species it usually extends to or past the umbilicus), restricting the expansion of the buccal cavity during feeding compared to other species.[35] The rostrum is pointed and the pectoral fins are relatively short, only 9%–10% of body length, and pointed at the tips.[9] It has a single ridge extending from the tip of the rostrum to the paired blowholes that are a distinctive characteristic of baleen whales.

The whale's skin is often marked by pits or wounds, which after healing become white scars. These are now known to be caused by "cookie-cutter" sharks (Isistius brasiliensis).[36] It has a tall, sickle-shaped dorsal fin that ranges in height from 38–90 cm (15–35 in) and averages 53–56 cm (21–22 in), about two-thirds of the way back from the tip of the rostrum.[37] Dorsal fin shape, pigmentation pattern, and scarring have been used to a limited extent in photo-identification studies.[38] The tail is thick and the fluke, or lobe, is relatively small in relation to the size of the whale's body.[9]

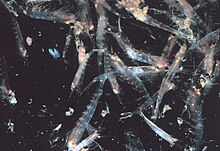

Adults have 300–380 ashy-black baleen plates on each side of the mouth, up to 80 cm (31 in) long. Each plate is made of fingernail-like keratin, which is bordered by a fringe of very fine, short, curly, wool-like white bristles.[8] The sei's very fine baleen bristles, about 0.1 mm (0.004 in) are the most reliable characteristic that distinguishes it from other rorquals.[39]

The sei whale looks very similar to other large rorquals, especially its smaller relative the Bryde's whale. The best way to distinguish between it and Bryde's whale, apart from differences in baleen plates, is by the presence of lateral ridges on the dorsal surface of the Bryde's whale's rostrum. Large individuals can be confused with fin whales, unless the fin whale's asymmetrical head coloration is clearly seen. The fin whale's lower jaw's right side is white, and the left side is grey. When viewed from the side, the rostrum appears slightly arched (accentuated at the tip), while fin and Bryde's whales have relatively flat rostrums.[7]

Sei whales usually travel alone[40] or in pods of up to six individuals.[38] Larger groups may assemble at particularly abundant feeding grounds. Very little is known about their social structure. During the southern Gulf of Maine influx in mid-1986, groups of at least three sei whales were observed "milling" on four occasions – i.e. moving in random directions, rolling, and remaining at the surface for over 10 minutes. One whale would always leave the group during or immediately after such socializing bouts.[38] The sei whale is among the fastest cetaceans. It can reach speeds of up to 50 km/h (27 kn) over short distances.[8] However, it is not a remarkable diver, reaching relatively shallow depths for 5 to 15 minutes. Between dives, the whale surfaces for a few minutes, remaining visible in clear, calm waters, with blows occurring at intervals of about 60 seconds (range: 45–90 sec.). Unlike the fin whale, the sei whale tends not to rise high out of the water as it dives, usually just sinking below the surface. The blowholes and dorsal fin are often exposed above the water surface almost simultaneously. The whale almost never lifts its flukes above the surface, and are generally less active on water surfaces than closely related Bryde's whales; it rarely breaches.[7]

This rorqual is a filter feeder, using its baleen plates to obtain its food by opening its mouth, engulfing or skimming large amounts of the water containing the food, then straining the water out through the baleen, trapping any food items inside its mouth.

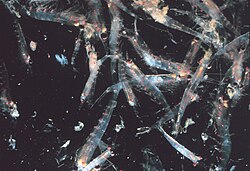

The sei whale feeds near the surface of the ocean, swimming on its side through swarms of prey to obtain its average of about 900 kg (2,000 lb) of food each day.[8] For an animal of its size, for the most part, its preferred foods lie unusually relatively low in the food chain, including zooplankton and small fish. The whale's diet preferences has been determined from stomach analyses, direct observation of feeding behavior,[41][42] and analyzing fecal matter collected near them, which appears as a dilute brown cloud. The feces are collected in nets and DNA is separated, individually identified, and matched with known species.[43] The whale competes for food against clupeid fish (herring and its relatives), basking sharks, and right whales.

In the North Atlantic, it feeds primarily on calanoid copepods, specifically Calanus finmarchicus, with a secondary preference for euphausiids, in particular Meganyctiphanes norvegica and Thysanoessa inermis.[44][45] In the North Pacific, it feeds on similar zooplankton, including the copepod species Neocalanus cristatus, N. plumchrus, and Calanus pacificus, and euphausiid species Euphausia pacifica, E. similis, Thysanoessa inermis, T. longipes, T. gregaria and T. spinifera. In addition, it eats larger organisms, such as the Japanese flying squid, Todarodes pacificus pacificus,[46] and small fish, including anchovies (Engraulis japonicus and E. mordax), sardines (Sardinops sagax), Pacific saury (Cololabis saira), mackerel (Scomber japonicus and S. australasicus), jack mackerel (Trachurus symmetricus) and juvenile rockfish (Sebastes jordani).[44][47] Some of these fish are commercially important. Off central California, they mainly feed on anchovies between June and August, and on krill (Euphausia pacifica) during September and October.[48] In the Southern Hemisphere, prey species include the copepods Neocalanus tonsus, Calanus simillimus, and Drepanopus pectinatus, as well as the euphausiids Euphausia superba and Euphausia vallentini[44] and the pelagic amphipod Themisto gaudichaudii.

Ectoparasites and epibiotics are rare on sei whales. Species of the parasitic copepod Pennella were only found on 8% of sei whales caught off California and 4% of those taken off South Georgia and South Africa. The pseudo-stalked barnacle Xenobalanus globicipitis was found on 9% of individuals caught off California; it was also found on a sei whale taken off South Africa. The acorn barnacle Coronula reginae and the stalked barnacle Conchoderma virgatum were each only found on 0.4% of whales caught off California. Remora australis were rarely found on sei whales off California (only 0.8%). They often bear scars from the bites of cookiecutter sharks, with 100% of individuals sampled off California, South Africa, and South Georgia having them; these scars have also been found on sei whales captured off Finnmark. Diatom (Cocconeis ceticola) films on sei whales are rare, having been found on sei whales taken off California and South Georgia.[37][48][49]

Due to their diverse diet, endoparasites are frequent and abundant in sei whales. The harpacticoid copepod Balaenophilus unisetus infests the baleen of sei whales caught off California, South Georgia, South Africa, and Finnmark. The ciliate protozoan Haematophagus was commonly found in the baleen of sei whales taken off South Georgia (nearly 85%). They often carry heavy infestations of acanthocephalans (e.g. Bolbosoma turbinella, which was found in 40% of sei whales sampled off California; it was also found in individuals off South Georgia and Finnmark) and cestodes (e.g. Tetrabothrius affinis, found in sei whales off California and South Georgia) in the intestine, nematodes in the kidneys (Crassicauda sp., California) and stomach (Anisakis simplex, nearly 60% of whales taken off California), and flukes (Lecithodesmus spinosus, found in 38% of individuals caught off California) in the liver.[37][48][49]

Mating occurs in temperate, subtropical seas during the winter. Gestation is estimated to vary around 103⁄4 months,[50] 111⁄4 months,[51] or one year,[52] depending which model of foetal growth is used. The different estimates result from scientists' inability to observe an entire pregnancy; most reproductive data for baleen whales were obtained from animals caught by commercial whalers, which offer only single snapshots of fetal growth. Researchers attempt to extrapolate conception dates by comparing fetus size and characteristics with newborns.

A newborn is weaned from its mother at 6–9 months of age, when it is 8–9 m (26–30 ft) long,[27] so weaning takes place at the summer or autumn feeding grounds. Females reproduce every 2–3 years,[50] usually to a single calf.[8] In the Northern Hemisphere, males are usually 12.8–12.9 m (42–42 ft) and females 13.3–13.5 m (44–44 ft) at sexual maturity, while in the Southern Hemisphere, males average 13.6 m (45 ft) and females 14 m (46 ft).[26] The average age of sexual maturity of both sexes is 8–10 years.[50] The whales can reach ages up to 65 years.[53]

The sei whale makes long, loud, low-frequency sounds. Relatively little is known about specific calls, but in 2003, observers noted sei whale calls in addition to sounds that could be described as "growls" or "whooshes" off the coast of the Antarctic Peninsula.[54] Many calls consisted of multiple parts at different frequencies. This combination distinguishes their calls from those of other whales. Most calls lasted about a half second, and occurred in the 240–625 hertz range, well within the range of human hearing. The maximum volume of the vocal sequences is reported as 156 decibels relative to 1 micropascal (μPa) at a reference distance of one metre.[54] An observer situated one metre from a vocalizing whale would perceive a volume roughly equivalent to the volume of a jackhammer operating two metres away.[55]

In November 2002, scientists recorded calls in the presence of sei whales off Maui. All the calls were downswept tonal calls, all but two ranging from a mean high frequency of 39.1 Hz down to 21 Hz of 1.3 second duration – the two higher frequency downswept calls ranged from an average of 100.3 Hz to 44.6 Hz over 1 second of duration. These calls closely resembled and coincided with a peak in "20- to 35-Hz irregular repetition interval" downswept pulses described from seafloor recordings off Oahu, which had previously been attributed to fin whales.[56] Between 2005 and 2007, low frequency downswept vocalizations were recorded in the Great South Channel, east of Cape Cod, Massachusetts, which were only significantly associated with the presence of sei whales. These calls averaged 82.3 Hz down to 34 Hz over about 1.4 seconds in duration. This call has also been reported from recordings in the Gulf of Maine, New England shelf waters, the mid-Atlantic Bight, and in Davis Strait. It likely functions as a contact call.[57]

BBC News quoted Roddy Morrison, a former whaler active in South Georgia, as saying, "When we killed the sei whales, they used to make a noise, like a crying noise. They seemed so friendly, and they'd come round and they'd make a noise, and when you hit them, they cried really. I didn't think it was really nice to do that. Everybody talked about it at the time I suppose, but it was money. At the end of the day that's what counted at the time. That's what we were there for."[58]

Sei whales live in all oceans, although rarely in polar or tropical waters.[7] The difficulty of distinguishing them at sea from their close relatives, Bryde's whales and in some cases from fin whales, creates confusion about their range and population, especially in warmer waters where Bryde's whales are most common.

In the North Atlantic, its range extends from southern Europe or northwestern Africa to Norway, and from the southern United States to Greenland.[6] The southernmost confirmed records are strandings along the northern Gulf of Mexico and in the Greater Antilles.[39] Throughout its range, the whale tends not to frequent semienclosed bodies of water, such as the Gulf of Mexico, the Gulf of Saint Lawrence, Hudson Bay, the North Sea, and the Mediterranean Sea.[7] It occurs predominantly in deep water, occurring most commonly over the continental slope,[59] in basins situated between banks,[60] or submarine canyon areas.[61]

In the North Pacific, it ranges from 20°N to 23°N latitude in the winter, and from 35°N to 50°N latitude in the summer.[62] Approximately 75% of the North Pacific population lives east of the International Date Line,[10] but there is little information regarding the North Pacific distribution. As of February 2017, the U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service estimated that the eastern North Pacific population stood at 374 whales.[63] Two whales tagged in deep waters off California were later recaptured off Washington and British Columbia, revealing a possible link between these areas,[64] but the lack of other tag recovery data makes these two cases inconclusive. Occurrences within the Gulf of California have been fewer.[65] In Sea of Japan and Sea of Okhotsk, whales are not common, although whales were more commonly seen than today in southern part of Sea of Japan from Korean Peninsula to the southern Primorsky Krai in the past, and there had been a sighting in Golden Horn Bay,[66] and whales were much more abundant in the triangle area around Kunashir Island in whaling days, making the area well known as sei – ground,[67] and there had been a sighting of a cow calf pair off the Sea of Japan coast of mid-Honshu during cetacean survey.

Sei whales have been recorded from northern Indian Ocean as well such as around Sri Lanka and Indian coasts.[68]

In the Southern Hemisphere, summer distribution based upon historic catch data is between 40°S and 50°S latitude in the South Atlantic and southern Indian Oceans and 45°S and 60°S in the South Pacific, while winter distribution is poorly known, with former winter whaling grounds being located off northeastern Brazil (7°S) and Peru (6°S).[2] The majority of the "sei" whales caught off Angola and Congo, as well as other nearby areas in equatorial West Africa, are thought to have been predominantly misidentified Bryde's whales. For example, Ruud (1952) found that 42 of the "sei whale" catch off Gabon in 1952 were actually Bryde's whales, based on examination of their baleen plates. The only confirmed historical record is the capture of a 14 m (46 ft) female, which was brought to the Cap Lopez whaling station in Gabon in September 1950. During cetacean sighting surveys off Angola between 2003 and 2006, only a single confirmed sighting of two individuals was made in August 2004, compared to 19 sightings of Bryde's whales.[69] Sei whales are commonly distributed along west to southern Latin America including along entire Chilean coasts, within Beagle Channel[70] and possibly feed in the Aysen region.[71] The Falkland Islands appears to be a regionally important area for the Sei Whale, as a small population exists in coastal waters off the eastern Falkland archipelago. For reasons unknown, the whales prefer to stay inland here, even venturing into large bays. This provides scientists with a rare opportunity to study this normally pelagic species without having to travel far out into the ocean.

In general, the sei whale migrates annually from cool and subpolar waters in summer to temperate and subtropical waters for winter, where food is more abundant.[7] In the northwest Atlantic, sightings and catch records suggest the whales move north along the shelf edge to arrive in the areas of Georges Bank, Northeast Channel, and Browns Bank by mid- to late June. They are present off the south coast of Newfoundland in August and September, and a southbound migration begins moving west and south along the Nova Scotian shelf from mid-September to mid-November. Whales in the Labrador Sea as early as the first week of June may move farther northward to waters southwest of Greenland later in the summer.[72] In the northeast Atlantic, the sei whale winters as far south as West Africa such as off Bay of Arguin, off coastal Western Sahara and follows the continental slope northward in spring. Large females lead the northward migration and reach the Denmark Strait earlier and more reliably than other sexes and classes, arriving in mid-July and remaining through mid-September. In some years, males and younger females remain at lower latitudes during the summer.[30]

Despite knowing some general migration patterns, exact routes are incompletely known[30] and scientists cannot readily predict exactly where groups will appear from one year to the next.[73] F.O. Kapel noted a correlation between appearances west of Greenland and the incursion of relatively warm waters from the Irminger Current into that area.[74] Some evidence from tagging data indicates individuals return off the coast of Iceland on an annual basis.[75] An individual satellite-tagged off Faial, in the Azores, traveled more than 4,000 km (2,500 mi) to the Labrador Sea via the Charlie-Gibbs Fracture Zone (CGFZ) between April and June 2005. It appeared to "hitch a ride" on prevailing currents, with erratic movements indicative of feeding behavior in five areas, in particular the CGFZ, an area of known high sei whale abundance as well as high copepod concentrations.[76] Seven whales tagged off Faial and Pico from May to June in 2008 and 2009 made their way to the Labrador Sea, while an eighth individual tagged in September 2009 headed southeast – its signal was lost between Madeira and the Canary Islands.[77]

The development of explosive harpoons and steam-powered whaling ships in the late nineteenth century brought previously unobtainable large whales within reach of commercial whalers. Initially their speed and elusiveness,[78] and later the comparatively small yield of oil and meat partially protected them. Once stocks of more profitable right whales, blue whales, fin whales, and humpback whales became depleted, sei whales were hunted in earnest, particularly from 1950 to 1980.[5]

In the North Atlantic between 1885 and 1984, 14,295 sei whales were taken.[10] They were hunted in large numbers off the coasts of Norway and Scotland beginning in the late 19th and early 20th centuries,[73] and in 1885 alone, more than 700 were caught off Finnmark.[79] Their meat was a popular Norwegian food. The meat's value made the hunting of this difficult-to-catch species profitable in the early twentieth century.[80]

In Iceland, a total of 2,574 whales were taken from the Hvalfjörður whaling station between 1948 and 1985. Since the late 1960s to early 1970s, the sei whale has been second only to the fin whale as the preferred target of Icelandic whalers, with meat in greater demand than whale oil, the prior target.[78]

Small numbers were taken off the Iberian Peninsula, beginning in the 1920s by Spanish whalers,[81] off the Nova Scotian shelf in the late 1960s and early 1970s by Canadian whalers,[72] and off the coast of West Greenland from the 1920s to the 1950s by Norwegian and Danish whalers.[74]

In the North Pacific, the total reported catch by commercial whalers was 72,215 between 1910 and 1975;[10] the majority were taken after 1947.[82] Shore stations in Japan and Korea processed 300–600 each year between 1911 and 1955. In 1959, the Japanese catch peaked at 1,340. Heavy exploitation in the North Pacific began in the early 1960s, with catches averaging 3,643 per year from 1963 to 1974 (total 43,719; annual range 1,280–6,053).[83] In 1971, after a decade of high catches, it became scarce in Japanese waters, ending commercial whaling in 1975.[44][84]

Off the coast of North America, sei whales were hunted off British Columbia from the late 1950s to the mid-1960s, when the number of whales captured dropped to around 14 per year.[5] More than 2,000 were caught in British Columbian waters between 1962 and 1967.[85] Between 1957 and 1971, California shore stations processed 386 whales.[48] Commercial Sei whaling ended in the eastern North Pacific in 1971.

A total of 152,233 were taken in the Southern Hemisphere between 1910 and 1979.[10] Whaling in southern oceans originally targeted humpback whales. By 1913, this species became rare, and the catch of fin and blue whales began to increase. As these species likewise became scarce, sei whale catches increased rapidly in the late 1950s and early 1960s.[44] The catch peaked in 1964–65 at over 20,000 sei whales, but by 1976, this number had dropped to below 2,000 and commercial whaling for the species ended in 1977.[5]

Since the moratorium on commercial whaling, some sei whales have been taken by Icelandic and Japanese whalers under the IWC's scientific research programme. Iceland carried out four years of scientific whaling between 1986 and 1989, killing up to 40 sei whales a year.[86][87] The research is conducted by the Institute of Cetacean Research (ICR) in Tokyo, a privately funded, nonprofit institution. The main focus of the research is to examine what they eat and to assess the competition between whales and fisheries. Dr. Seiji Ohsumi, Director General of the ICR, said,

He later added,

Conservation groups, such as the World Wildlife Fund, dispute the value of this research, claiming that sei whales feed primarily on squid and plankton which are not hunted by humans, and only rarely on fish. They say that the program is

At the 2001 meeting of the IWC Scientific Committee, 32 scientists submitted a document expressing their belief that the Japanese program lacked scientific rigor and would not meet minimum standards of academic review.[91]

In 2010, a Los Angeles exclusive Sushi restaurant confirmed to be serving sei whale meat was closed by its owners after a covert investigation and protests lead to prosecution by authorities for handling an endangered/protected species. [92]

The sei whale did not have meaningful international protection until 1970, when the International Whaling Commission first set catch quotas for the North Pacific for individual species. Before quotas, there were no legal limits.[93] Complete protection from commercial whaling in the North Pacific came in 1976.

Quotas on sei whales in the North Atlantic began in 1977. Southern Hemisphere stocks were protected in 1979. Facing mounting evidence that several whale species were threatened with extinction, the IWC established a complete moratorium on commercial whaling beginning in 1986.[7]

In the late 1970s, some "pirate" whaling took place in the eastern North Atlantic.[94] There is no direct evidence of illegal whaling in the North Pacific, although the acknowledged misreporting of whaling data by the Soviet Union[95] means that catch data are not entirely reliable.

The species remained listed on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species in 2000, categorized as "endangered".[2] Northern Hemisphere populations are listed as CITES Appendix II, indicating they are not immediately threatened with extinction, but may become so if they are not listed. Populations in the Southern Hemisphere are listed as CITES Appendix I, indicating they are threatened with extinction if trade is not halted.[8]

The sei whale is listed on both Appendix I[96] and Appendix II[96] of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS). It is listed on Appendix I[96] as this species has been categorized as being in danger of extinction throughout all or a significant proportion of their range and CMS parties strive towards strictly protecting these animals, conserving or restoring the places where they live, mitigating obstacles to migration and controlling other factors that might endanger them and also on Appendix II[96] as it has an unfavourable conservation status or would benefit significantly from international co-operation organised by tailored agreements.

Sei whale is covered by the Memorandum of Understanding for the Conservation of Cetaceans and Their Habitats in the Pacific Islands Region (Pacific Cetaceans MOU) and the Agreement on the Conservation of Small Cetaceans of the Baltic, North East Atlantic, Irish and North Seas (ASCOBAMS).[97]

The species is listed as endangered by the U.S. government National Marine Fisheries Service under the U.S. Endangered Species Act.[5]

The current population is estimated at 80,000, nearly a third of the prewhaling population.[9][12] A 1991 study in the North Atlantic estimated only 4,000.[98][99] Sei whales were said to have been scarce in the 1960s and early 1970s off northern Norway.[100] One possible explanation for this disappearance is that the whales were overexploited.[100] The drastic reduction in northeastern Atlantic copepod stocks during the late 1960s may be another culprit.[101] Surveys in the Denmark Strait found 1,290 whales in 1987, and 1,590 whales in 1989.[101] Nova Scotia's population estimates are between 1,393 and 2,248, with a minimum of 870.[72]

A 1977 study estimated Pacific Ocean totals of 9,110, based upon catch and CPUE data.[83] Japanese interests claim this figure is outdated, and in 2002 claimed the western North Pacific population was over 28,000,[89] a figure not accepted by the scientific community.[90] In western Canadian waters, researchers with Fisheries and Oceans Canada observed five Seis together in the summer of 2017, the first such sighting in over 50 years.[102] In California waters, there was only one confirmed and five possible sightings by 1991 to 1993 aerial and ship surveys,[103][104][105] and there were no confirmed sightings off Oregon coasts such as Maumee Bay and Washington. Prior to commercial whaling, the North Pacific hosted an estimated 42,000.[83] By the end of whaling, the population was down to between 7,260 and 12,620.[83]

In the Southern Hemisphere, population estimates range between 9,800 and 12,000, based upon catch history and CPUE.[98] The IWC estimated 9,718 whales based upon survey data between 1978 and 1988.[106] Prior to commercial whaling, there were an estimated 65,000.[98]

Mass death events for sei whales have been recorded for many years and evidence suggests endemic poisoning (red tide) causes may have caused mass deaths in prehistoric times. In June 2015, scientists flying over southern Chile counted 337 dead sei whales, in what is regarded as the largest mass beaching ever documented.[107] The cause is not yet known; however, toxic algae blooms caused by unprecedented warming in the Pacific Ocean, known as the Blob, may be implicated.[108]

The sei whale (/seɪ/ SAY, Norwegian: [sæɪ]; Balaenoptera borealis) is a baleen whale, the third-largest rorqual after the blue whale and the fin whale. It inhabits most oceans and adjoining seas, and prefers deep offshore waters. It avoids polar and tropical waters and semi-enclosed bodies of water. The sei whale migrates annually from cool, subpolar waters in summer to temperate, subtropical waters in winter with a lifespan of 70 years.

Reaching 19.5 m (64 ft) in length and weighing as much as 28 t (28 long tons; 31 short tons), the sei whale consumes an average of 900 kg (2,000 lb) of food every day; its diet consists primarily of copepods, krill, and other zooplankton. It is among the fastest of all cetaceans, and can reach speeds of up to 50 km/h (31 mph) (27 knots) over short distances. The whale's name comes from the Norwegian word for pollock, a fish that appears off the coast of Norway at the same time of the year as the sei whale.

Following large-scale commercial whaling during the late 19th and 20th centuries, when over 255,000 whales were killed, the sei whale is now internationally protected. As of 2008, its worldwide population was about 80,000, less than a third of its prewhaling population.

El rorcual norteño (Balaenoptera borealis), también conocido como rorcual boreal, rorcual de Rudolphi, rorcual sei y ballena boba, es una especie de cetáceo misticeto de la familia Balaenopteridae. Luego de ser cazado a gran escala en los mares del sur durante la mitad del siglo XX, época en que se mataron cerca de 200 000 ejemplares, el rorcual sei es ahora una especie protegida internacionalmente.

La palabra sei (del nombre en inglés sei whale) proviene del noruego y significa «abadejo» (Pollachius pollachius), similar al bacalao. Los rorcuales boreales se alimentan de bacalao (Gadus morhua), entre otros peces y calamares en las aguas de Noruega, por lo que peces y ballenas eran vistos juntos frecuentemente, dando al rorcual ese nombre.

Este rorcual, junto con las demás especies del suborden Mysticeti, posee barbas en lugar de dientes, y fue descrito por primera vez por Lesson en 1828, aunque una descripción posterior la realizó Karl Asmund Rudolphi, por lo que en fuentes antiguas también se lo denomina rorcual de Rudolphi.

Se han identificado dos subespecies:

Los análisis genéticos pueden todavía causar que ambas subespecies sean reclasificadas como especies diferentes.

Existen individuos de hasta 20 m de longitud y pesos de hasta 45 toneladas. Las crías al nacer miden 4 a 5 metros. El rorcual norteño se asemeja al rorcual de Bryde. En el mar, la distinción más fiable es la secuencia de zambullida. Tiene un cuerpo relativamente delgado, de color gris oscuro en el dorso y gris claro a blanco en el vientre. El dorso presenta habitualmente cicatrices blancas, que se cree son causadas por tiburones. La aleta dorsal está un poco más adelante que en la mayoría de los rorcuales, pero igualmente en la mitad posterior del dorso.

Carwardine (1995) describe la aleta como erecta, pero contradictoriamente Reeves (2002) la mencionan como "muy curvada". La cola es gruesa y la aleta caudal pequeña en relación al cuerpo.

Los rorcuales norteños se mueven solos o en grupos pequeños. Los grupos grandes han sido avistados muy ocasionalmente en bancos de alimentación abundante. La secuencia de zambullida es más regular que otros rorcuales. El soplido dura 40 a 60 segundos, seguido por una profunda zambullida de cinco a quince minutos. Entre zambullidas permanecen cerca de la superficie y es visible en aguas claras y calmas. Es uno de los nadadores más rápidos de todos los cetáceos, ya que puede alcanzar velocidades de hasta 25 nudos (aprox. 47 km./h) en distancias cortas.

El rorcual sei habita en todo el mundo en una banda entre los 60º S y los 60º N. Prefieren las aguas profundas. Difieren de otros rorcuales en la imposibilidad de prever sus movimientos migratorios, ya que no frecuentan los mismos sitios año a año. Migran anualmente desde las aguas frías subpolares en verano a aguas tropicales en invierno.

La población total se cree que no es mayor a 50.000 o 60.000 ejemplares, de los cuales cerca de 10 000 habitan los alrededores de Islandia.

Con el advenimiento de grandes y rápidos barcos balleneros, estos rorcuales fueron cazadas en abundancia, especialmente en la Antártida. Alrededor de 200.000 ejemplares (la WWF reporta exactamente 203.588) fueron capturados en el siglo XX, lo que representó el 80% de la población de la especie. En 1976 se la declaró especie protegida por la Comisión ballenera internacional. Desde esa fecha, han venido siendo capturadas únicamente por balleneros de Islandia y Japón aduciendo fines científicos. En la actualidad, los japoneses capturan aproximadamente 50 ejemplares anuales, analizando la alimentación del animal y cómo esta influye en los bancos de pesca. Las organizaciones ambientales se oponen a la necesidad de esta investigación, teniendo en cuenta que se conoce que el rorcual sei se alimenta de pequeños peces, calamares y plancton que no constituyen directamente alimento humano.

El rorcual norteño (Balaenoptera borealis), también conocido como rorcual boreal, rorcual de Rudolphi, rorcual sei y ballena boba, es una especie de cetáceo misticeto de la familia Balaenopteridae. Luego de ser cazado a gran escala en los mares del sur durante la mitad del siglo XX, época en que se mataron cerca de 200 000 ejemplares, el rorcual sei es ahora una especie protegida internacionalmente.

Ipar-zere (Balaenoptera borealis) Balaenoptera generoko animalia da. Artiodaktiloen barruko Balaenopteridae familian sailkatuta dago.

Ipar-zerek bi azpiespezie ditu:

Ipar-zere (Balaenoptera borealis) Balaenoptera generoko animalia da. Artiodaktiloen barruko Balaenopteridae familian sailkatuta dago.

Ipar-zerek bi azpiespezie ditu:

Balaenoptera borealis borealis Balaenoptera borealis schlegliiSeitivalas eli uurteisvalas[2] (Balaenoptera borealis) on uurteisvalaiden heimoon kuuluva laji, jota tavataan kaikilla merialueilla. Toisin kuin sukulaisensa sillivalas, se välttelee lahtia ja pysyttelee avoimemmilla merialueilla. Seitivalas vaeltaa kesäksi viileille merialueille ja talveksi subtrooppisille merille.[3]

Laji on saanut nimensä seitin mukaan, sillä sitä tavataan Norjan edustalla samaan aikaan kuin suuria seitiparviakin.[4]

Lajin hetulat ovat mustat.[2]

Seitivalaiden määrä on pienentynyt valaanpyynnin takia viidennekseen määrästä, mitä niitä oli ennen pyynnin aloittamista. Niitä on nykyisin jäljellä noin 54 000 yksilöä.[4]

Seitivalas eli uurteisvalas (Balaenoptera borealis) on uurteisvalaiden heimoon kuuluva laji, jota tavataan kaikilla merialueilla. Toisin kuin sukulaisensa sillivalas, se välttelee lahtia ja pysyttelee avoimemmilla merialueilla. Seitivalas vaeltaa kesäksi viileille merialueille ja talveksi subtrooppisille merille.

Laji on saanut nimensä seitin mukaan, sillä sitä tavataan Norjan edustalla samaan aikaan kuin suuria seitiparviakin.

Lajin hetulat ovat mustat.

Balaenoptera borealis

Le Baleinoptère de Rudolphi, Rorqual boréal, Rorqual de Rudolphi ou Rorqual sei (Balaenoptera borealis) est une espèce de baleines à fanons présente dans tous les océans du monde et dans toutes les mers attenantes, avec une prédilection pour la haute mer et les océans profonds[1]. Il évite les eaux glaciales et tropicales ainsi que les mers semi-fermées. Le rorqual boréal effectue une migration annuelle des mers subpolaires froides en été, vers les mers subtropicales tempérées l'hiver, sans qu'on connaisse précisément ses routes de migration dans la plupart des régions du globe[2].

C'est, derrière la baleine bleue et le rorqual commun, le troisième plus grand rorqual au monde[3]. Ces baleines atteignent une longueur de vingt mètres et un poids de quarante-cinq tonnes[2]. Elles ingèrent quotidiennement en moyenne 900 kg de nourriture, se composant essentiellement de copépodes, de krill, et d'autres formes de zooplancton[4]. Elles comptent parmi les cétacés les plus véloces, avec une vitesse pouvant dépasser 50 km/h sur de courtes distances[4]. Dans de nombreuses langues, son nom est associé au lieu noir (sei dans les langues scandinaves), car ce poisson migre périodiquement vers les côtes de Norvège à la même saison que le Rorqual boréal[5].

À la suite de la pêche industrielle qui, entre la fin du XIXe et le début du XXe siècle, décima cette espèce avec plus de 238 000 individus capturés[6], le rorqual boréal est aujourd'hui reconnu comme une espèce protégée par les accords internationaux[7], bien qu'une chasse confidentielle demeure autorisée dans le cadre de « programmes de recherche » controversés, menés par l'Islande et le Japon[8]. Pour l'année 2006, la population mondiale de rorquals boréaux était estimée à 54 000 individus, soit environ un cinquième de l'effectif d'avant la pêche à la baleine[5].

Le rorqual boréal est, par sa taille et son poids, le troisième représentant de la famille des Balaenopteridae, derrière la baleine bleue, qui peut atteindre 200 tonnes, et le rorqual commun, qui pèse jusqu'à 77 tonnes[3]. Les adultes matures atteignent typiquement 12–15 mètres[4] pour un poids de 20 à 30 tonnes. Le rorqual boréal de Schlegel, sous-espèce vivant dans l'hémisphère Sud, est plus grand que son homologue de l'hémisphère nord. Il peut dépasser les 17 mètres et les 28 tonnes, tandis que les plus grands spécimens capturés au large de l'Islande ne font guère plus de 16 mètres[9],[2]. Les femelles sont bien plus grandes que les mâles[2]. Le plus grand rorqual boréal connu mesurait 20 mètres[4], et pesait entre 40 et 45 tonnes. À la naissance, un baleineau mesure en général 4 à 5 mètres[4].

Le corps de ce cétacé est gris acier avec des marques irrégulières gris clair à blanchâtres sur la face ventrale, ou vers l'avant de cette dernière. Ce rorqual possède le long de sa face ventrale 32 à 60 sillons ou replis, qui permettent une dilatation considérable de sa gorge pendant l'ingestion du plancton. Le museau est pointu et les nageoires pectorales, à l'extrémité pointue, sont relativement plus courtes que celles des autres cétacés, puisqu'elles ne font que 9 à 10 % de la longueur totale de l'animal[5]. Le rorqual boréal possède une crête unique, qui prend naissance au-dessus du museau et s'étend jusqu'à la paire d'évents, le double évent étant une caractéristique morphologique de la famille des rorquals.

Sa peau présente fréquemment des crevasses ou des coupures, qui, après cicatrisation, prennent une couleur blanche. On attribue ceci à l'action d'ectoparasites, des copépodes (Penella spp.)[10], ou des lamproies (famille des Petromyzontidae[11]), voire au squalelet féroce (Isistius brasiliensis)[12].

La nageoire dorsale est haute (de 25 à 61 cm), falciforme ; elle se dresse au 2/3 du corps en partant du museau. La forme de cette nageoire, la pigmentation cutanée et les cicatrices servent jusqu'à un certain point à identifier ces rorquals sur les photos[13]. La queue est épaisse et les nageoires caudales ou « lobes » sont relativement petites comparées à la taille de l'animal.

Le rorqual boréal est un animal filtreur ; il utilise ses fanons pour séparer sa nourriture de l'eau de mer : il ouvre la bouche, engouffre de grandes quantités d'eau contenant de la nourriture, puis il force l'eau à sortir à travers les fanons, piégeant ainsi le plancton qui vient se plaquer sur la face interne. Un adulte possède de 300 à 380 fanons de couleur cendrée de chaque côté de la gueule, chacun mesurant près de 50 cm de longueur. Chaque fanon, fait de kératine cornée, se termine vers l'intérieur de la gueule près de la langue par des filaments blanchâtres[4]. Ces très fines soies de 0,1 mm d'épaisseur environ, constituent le signe distinctif le plus sûr de cette espèce au sein du groupe des baleines à fanons[14].

Le rorqual boréal étant très semblable aux autres rorquals, le meilleur moyen de le distinguer du rorqual de Bryde, si l'on fait exception des différences mentionnées précédemment, est la présence chez le rorqual de Bryde de rainures latérales sur la face dorsale de la tête. On pourrait encore confondre un grand rorqual boréal avec le rorqual commun, si ce n'est que, chez ce dernier, une asymétrie de la couleur de peau de part et d'autre de la tête est bien repérable : tandis que le bas de la joue droite est blanc, le bas de la joue gauche est gris. Vue de côté, la face supérieure de la tête du rorqual boréal est légèrement convexe entre la pointe du museau et l'œil, alors que le profil du rorqual commun est plutôt plat[2].

Le rorqual boréal se déplace généralement seul[15] ou en petit groupe jusqu'à six individus[13]. On ne voit de plus grands regroupements que dans des zones d'alimentation exceptionnellement riches. On ne sait pratiquement rien de leur comportement social. Il se pourrait que mâle et femelle restent en couple, mais la recherche actuelle ne permet pas de l'affirmer[3],[16].

Comme les autres cétacés, le rorqual boréal émet des sifflements longs et graves (sons de basse fréquence). On sait relativement peu de choses des appels spécifiques à ce rorqual, mais en 2003, des observateurs ont enregistré, mêlé au chant des rorquals, des sons à large bande spectrale qu'ils ont décrits comme des « grognements » ou des « grincements » au large de la Péninsule Antarctique[17]. Ces chants, pour l'essentiel, sont constitués d'une série de sifflements avec un changement de note à chaque sifflement. Ces changements sont caractéristiques de l'espèce : ils permettent de distinguer le rorqual boréal des autres baleines. La plupart des sifflements durent moins d'une demi-seconde et correspondent à une fréquence comprise entre 240 et 625 hertz, ce qui correspond parfaitement aux fréquences audibles par l'oreille humaine. Les vocalisations sont fortes, d'une puissance acoustique pouvant atteindre 152–160 décibels pour 1 μPa de pression sonore, à une distance de référence d'un mètre[17]. Pour comparaison, un homme qui se trouverait à un mètre de l'animal lorsqu'il émet ce sifflement percevrait un volume sonore équivalent environ à celui produit par un marteau-piqueur se trouvant à deux mètres de lui[18].

L’accouplement a lieu l'hiver dans les eaux subtropicales tempérées ; la période de gestation a une durée estimée, selon le modèle de croissance du fœtus utilisé, à dix mois et trois semaines[19], onze mois et une semaine[20], voire un an[21]. Ces différences d'estimation proviennent du fait qu'il n'a pas été possible, jusqu'ici, d'observer la totalité de la période de gestation de cet animal ; la plupart des informations disponibles sur la reproduction des rorquals sont tirées d'observations faites sur des animaux tués par des chasseurs de cétacés, ce qui n'offre qu'un point de vue très partiel sur la croissance fœtale. C'est pourquoi les chercheurs tentent de déterminer par extrapolation la date de conception, par comparaison des mesures et des caractéristiques physiques des fœtus avec celles des baleineaux nouveau-nés. Le petit, à la naissance, pèse déjà près de 700 kg[22].

Le nouveau-né est sevré vers l'âge de 6–9 mois, en été ou à l'automne, et il se trouve alors dans les bancs de krill ; sa taille est déjà de 11–12 mètres[19]. Les femelles mettent bas tous les 2–3 ans[19] et, bien que l'on rapporte le cas d'un rorqual boréal portant 6 fœtus, les naissances uniques sont de loin les plus fréquentes[4]. L'âge moyen de maturité sexuelle chez les deux sexes est de 8–10 ans[19], les mâles ayant alors une taille de 12 mètres et les femelles de 13 mètres[5]. Les baleines peuvent vivre jusqu'à l'âge de 65 ans[23], mais le record actuel de longévité serait de 74 ans[24].

Le rorqual boréal se nourrit dans les eaux de surface des océans par « écrémage » (skimming) : il nage de côté à faible profondeur, la gueule ouverte, à travers les bancs de plancton. On pense que cette manière de chasser lui permet de s'alimenter correctement dans des zones à faible concentration de nourriture, qui ne conviendraient pas aux autres espèces de rorquals[25]. Engloutissant en moyenne chaque jour 900 kilogrammes de nourriture[4], composée principalement de zooplancton, mais aussi d'un peu de céphalopodes et de petits poissons de tailles inférieures à 30 cm[26], il se trouve assez bas dans la chaîne alimentaire. Il est ainsi moins susceptible d'être considéré par les pêcheurs comme un concurrent, mais ce régime très sélectif le rend plus sensible aux variations de sa ressource alimentaire[2].

La préférence des baleines pour le zooplancton a été établie par analyse de leur contenu stomacal et par observation directe de leur comportement alimentaire[27],[28]. Elle a également été déterminée par analyse du contenu des fèces prélevées à proximité du rorqual boréal, fèces qui apparaissent comme un fin brouillard marron dans l'eau. Ces dernières sont collectées dans des filets, et le matériel génétique présent dans les déchets est isolé, identifié individuellement et comparé avec l'ADN de spécimens d'autres espèces génétiquement connues[29]. Le rorqual est en compétition alimentaire avec d'autres prédateurs, notamment les clupéidés (c'est-à-dire les poissons apparentés au hareng), les requins pèlerins, et les baleines à fanons.

Dans l'Atlantique Nord, le rorqual boréal se nourrit principalement de copépodes calanoïdes, plus précisément de Calanus finmarchicus, puis (et par ordre de préférence) d'euphausiidés (krill), en particulier Meganyctiphanes norvegica et Thysanoessa inermis[30],[31].

Dans le Pacifique Nord, le rorqual boréal se nourrit à un niveau trophique plus élevé que dans l'Océan Austral[2]. Il consomme non seulement des espèces analogues de zooplancton, à savoir les copépodes Calanus cristatus, Neocalanus plumchrus, et Calanus pacificus, ainsi que d'euphausiidés : Euphausia pacifica, Thysanoessa inermis, Thysanoessa longipes, et Thysanoessa spinifera. Mais on sait qu'il consomme également des animaux de plus grande taille, notamment des céphalopodes comme le Toutenon japonais (et plus spécifiquement le Todarodes pacificus pacificus)[32], ainsi que de petits poissons du genre Engraulis (anchois), Cololabis (sauries), Sardinops, et le Trachurus (chinchard)[30],[33] de la taille d'un maquereau adulte. Selon Nemoto et Kawamura[2], il s'attaquerait à quasiment tous les organismes grégaires s'assemblant en masse. Certaines de ses proies ont un intérêt commercial. Au large de la Californie, on a observé que le rorqual se nourrissait d'anchois de juin à août, et de krill (Euphausia pacifica) en septembre et octobre[11].

Dans l'hémisphère Sud, les proies sont constituées des copépodes Calanus finmarchicus, Calanus simillimus, et Drepanopus pectinatus, ainsi que des euphausiidés Euphausia superba et Euphausia vallentini[30]. En dessous de la convergence antarctique, les rorquals boréaux se nourrissent exclusivement de krill antarctique (Euphausia superba)[25].

Le rorqual boréal compte parmi les cétacés les plus rapides : sa vitesse sur de courtes distances peut atteindre 50 km/h[4] ; en revanche, c'est un plongeur médiocre, qui ne plonge qu'à de faibles profondeurs, estimées à moins de 300 m[26], refaisant surface toutes les 5 à 15 minutes. Il nage près de la surface plusieurs minutes avant de replonger, ce qui le rend visible dans les eaux calmes et par temps clair, son souffle s'exprimant par les évents toutes les 40 à 60 secondes. Le rorqual boréal ne plonge pas véritablement, comme le fait le Rorqual commun, qui disparaît verticalement, la queue la dernière, et reparaît toujours verticalement le museau d'abord. Le rorqual boréal s'enfonce presqu'horizontalement dans l'eau, et lorsqu'il réapparaît, ses évents et sa nageoire dorsale émergent en même temps[25]. À la différence des autres espèces, ce cétacé bondit rarement hors de l'eau.

On trouve les rorquals boréaux dans tous les océans du globe, bien qu'ils s'abstiennent de fréquenter les eaux polaires et tropicales[2]. La difficulté à les distinguer de leurs proches cousins, le rorqual de Bryde et parfois aussi le rorqual commun, a suscité des confusions quant à leur répartition géographique et à leur effectif, particulièrement dans les mers chaudes où le rorqual de Bryde est très répandu.

Dans l'océan Atlantique Nord, le rorqual boréal est présent de Gibraltar et des côtes de Mauritanie jusqu'au large de la Norvège pour la moitié est, et des côtes de Floride au Groenland pour la moitié ouest[1]. Les localisations les plus méridionales sont des zones situées au large du golfe du Mexique et autour des Grandes Antilles[14]. Dans toutes ces régions, cette baleine paraît éviter toutes les mers semi-fermées comme le golfe du Mexique, l'embouchure du fleuve Saint-Laurent, la baie d'Hudson, la mer du Nord, et la mer Méditerranée[2]. On la trouve le plus souvent nageant dans les mers profondes, préférentiellement au large du plateau continental[34], dans les fosses circonscrites par des plateaux sous-marins[35], ou au-dessus des gorges tracées dans les canyon sous-marins[36].

En ce qui concerne le Pacifique Nord, on trouve le rorqual boréal sous les latitudes de 20°N–23°N l'hiver, et entre 35°N–50°N de latitude l'été[37]. Près de 75 % de la population totale des rorquals du Pacifique Nord vit à l'est de la ligne de changement de date[6], mais la répartition des cétacés dans cette partie du globe est encore très mal connue. Deux baleines marquées dans les eaux profondes au large des côtes de Californie ont été recapturées plus tard au large de l'État de Washington et de la Colombie-Britannique, laissant entrevoir un lien possible entre ces deux zones[38], mais le nombre insuffisant de marquages fait de ces deux individus des cas isolés à partir desquels il est difficile de tirer des conclusions. Dans l'hémisphère austral, la répartition en été, estimée d'après les données tirées de l'historique des captures, est concentrée entre 40° et 50° de latitude sud, la répartition hivernale étant encore inconnue[30].

D'une manière générale, le rorqual boréal migre chaque année entre les eaux subpolaires froides, qu'il fréquente en été, et les eaux subtropicales tempérées, où il hiverne[2]. Les captures ont révélé une séparation marquée des sexes pendant ces déplacements, les femelles gravides arrivant et repartant les premières des lieux de nourrissage[25]. Il semble qu'il y a également une séparation par tranches d'âge.