Associations

provided by BioImages, the virtual fieldguide, UK

Foodplant / sap sucker

Stephanitis takeyai sucks sap of Sassafras albidum

Comments

provided by eFloras

Infraspecific taxa have been based on amount of pubescence of leaves and color of young twigs; these taxa are not recognized here.

Traditionally, "sassafras tea" was prepared by steeping the bark of the roots (D. S. Correll and M. C. Johnston 1970). It was once considered a relatively pleasant drink. Several indigenous populations used sassafras twigs as chewing sticks, and sassafras root is used occasionally in commercial dental poultices. Sassafras root was one of the ingredients of root beer; this use has now been banned.

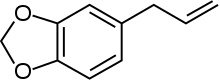

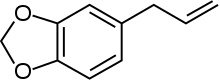

Safrole ( p -allylyn ethylenediozybenzene) is found as a minor component in many Lauraceae and as the principal component (80%) of sassafras oil. It is suspected of causing contact dermatitis and of being hallucinogenic, especially in large doses; it is also considered to be both carcinogenic and hepatotoxic (W. H. Lewis and M. P. F. Elvin-Lewis 1977).

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- Missouri Botanical Garden, 4344 Shaw Boulevard, St. Louis, MO, 63110 USA

Description

provided by eFloras

Trees , to 35 m. Twigs pale green with darker olive mottling, terete. Leaf blade ovate to elliptic, unlobed or 2-3-lobed (rarely more), 10-16 × 5-10 cm, apex obtuse to acute. Inflorescences to 5 cm, silky-pubescent; floral bract to 1 cm. Flowers: fragrant (sweet, lemony), glabrous; tepals greenish yellow. Staminate flowers: inner 3 stamens with 2 conspicuously stalked glands near base of filament, filament slender; pistillodes usually absent (sometimes present in terminal flower of inflorescence). Pistillate flowers: staminodes 6; style slender, 2-3 mm; stigma capitate. Drupe ca. 1 cm; pedicel reddish, club-shaped, ± fleshy. 2 n = 48.

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- Missouri Botanical Garden, 4344 Shaw Boulevard, St. Louis, MO, 63110 USA

Distribution

provided by eFloras

Ont.; Ala., Ark., Conn., Del., D.C., Fla., Ga., Ill., Ind., Iowa, Kans., Ky., La., Maine, Md., Mass., Mich., Miss., Mo., N.H., N.J., N.Y., N.C., Ohio, Okla., Pa., R.I., S.C., Tenn., Tex., Vt., Va., W.Va.

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- Missouri Botanical Garden, 4344 Shaw Boulevard, St. Louis, MO, 63110 USA

Flowering/Fruiting

provided by eFloras

Flowering spring (Apr-May).

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- Missouri Botanical Garden, 4344 Shaw Boulevard, St. Louis, MO, 63110 USA

Habitat

provided by eFloras

Habitat varied, forests, woodlands, fencerows, old fields (sometimes aggressively colonial), and disturbed areas; 0-1500m.

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- Missouri Botanical Garden, 4344 Shaw Boulevard, St. Louis, MO, 63110 USA

Synonym

provided by eFloras

Laurus albida Nuttall, Gen. N. Amer. Pl. 1: 259. 1818; L. sassafras Linnaeus; Sassafras albidum var. molle (Rafinesque) Fernald; S. officinalis T. Nees ex C. H. Ebermaier; S. sassafras (Linnaeus) H. Karsten; S. variifolium (Salisbury) Kuntze

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- Missouri Botanical Garden, 4344 Shaw Boulevard, St. Louis, MO, 63110 USA

Broad-scale Impacts of Plant Response to Fire

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

More info for the terms:

fire use,

prescribed fireThe following Research Project Summaries

provide information on prescribed

fire use and postfire response of plant

community species, including sassafras,

that was not available when this

species review was originally

written:

- bibliographic citation

- Sullivan, Janet. 1993. Sassafras albidum. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Common Names

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

More info for the term:

treesassafras

white sassafras

common sassafras

ague tree

cinnamon wood

smelling stick

saloop

gumbo file

mitten tree

- bibliographic citation

- Sullivan, Janet. 1993. Sassafras albidum. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Conservation Status

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

Sassafras is listed under "Special Concern-Possibly Extirpated" in Maine [

22].

- bibliographic citation

- Sullivan, Janet. 1993. Sassafras albidum. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Description

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

More info for the terms:

drupe,

fruit,

shrub,

treeSassafras is a native, deciduous, aromatic tree or large shrub, with a

flattened, oblong crown [

41,

83]. On the best sites, height ranges up to

98 feet (30 m) [

41]. In the northern parts of its range, sassafras

tends to be shrubby, especially on dry, sandy sites, and reaches a

maximum of 40 feet (12 m) [

49]. The bark of older stems is deeply

furrowed, or irregularly broken into broad, flat ridges [

38,

83]. The

variety of leaf shapes to be found on one individual is a distinctive

trait of the species. Leaves can be entire, one-lobed, or two-lobed.

The fruit is a drupe [

41]. The root system is shallow, with prominent

lateral roots. Root depth ranges from 6 to 20 inches (15-50 cm).

- bibliographic citation

- Sullivan, Janet. 1993. Sassafras albidum. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Distribution

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

Sassafras occurs from southwestern Maine west to extreme southern

Ontario and central Michigan; southwest to Illinois, Missouri, eastern

Oklahoma, and eastern Texas; and east to central Florida. It is extinct

in southeastern Wisconsin, but its range is extending into northern

Illinois [

41].

- bibliographic citation

- Sullivan, Janet. 1993. Sassafras albidum. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Fire Ecology

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

More info for the terms:

fire frequency,

fire interval,

fire regime,

frequency,

mean fire interval,

severity,

top-killSassafras is moderately resistant to fire damage to aboveground growth.

It is also highly resilient to such damage; sassafras sprouts vigorously

following top-kill, even after repeated fires [

54]. In Indiana,

sassafras occurs in black oak (Quercus velutina) stands with a mean fire

interval of 11.1 years [

47]. Sassafras establishment on these sites

appears to be related to the frequency and severity of fire. Sassafras

did not occur on sites which had burned more often (mean fire interval

of 5.2 years). The stands with longer fire-free intervals burned more

severely than those with shorter intervals. The more severe disturbance

probably created more favorable conditions for sassafras seedling

establishment [

48].

An increase in the frequency of sassafras in New Jersey forests since

European settlement has been attributed, at least in part, to an

increase in fire frequency [

73].

The bear oak type, in which sassafras frequently occurs, is a product of

periodic fire and droughty soils [

44]. Sassafras also occurs in the

Table Mountain pine-pitch pine (Pinus rigida) type, another fire-adapted

community [

42].

Sassafras bark is less resistant to heat than chestnut oak (Quercus

prinus), white oak (Q. alba), and northern red oak (Q. rubra); equally

as resistant as hickory and red maple (Acer rubrum); and more resistant

than witchhazel (Hamamelis virginiana), fire cherry (Prunus

pensylvanica), serviceberry (Amelanchier spp.), and bear oak [

20].

FIRE REGIMES : Find fire regime information for the plant communities in which this

species may occur by entering the species name in the

FEIS home page under

"Find FIRE REGIMES".

- bibliographic citation

- Sullivan, Janet. 1993. Sassafras albidum. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Fire Management Considerations

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

More info for the terms:

fruit,

fuel,

hardwood,

prescribed firePrescribed fire for hardwood control in southern pine stands results in

the predominance of American beautyberry (Callicarpa americana) and

sassafras. This predominance is a useful indicator of temporary control

over other hardwoods that usually occupy later seres and are more

serious competitors of pine. Prescribed fire at 8- to 12-year intervals

can control sprout growth or new plant invasion [

74].

In South Carolina, a prescribed January fire in loblolly pine increased

sassafras browse quality and availability. Prior to the fire, sassafras

stems were out of reach of white-tailed deer [

21]. The protein content

of sassafras leaves and twigs was highest in June following prescribed

fire. By September, the protein content of all browse plants was

similar on burned and unburned sites [

23]. After logging and

prescribed burning in an oak-pine stand in South Carolina, white-tailed

deer browsed sassafras heavily [

27].

Frequent prescribed fire can improve spring and summer forage quality in

the southern pine forests, where sassafras often occurs.

Prescribed fire on utility rights-of-way does not control sassafras [

5].

Vigorous root sprouting maintains sassafras even after repeated fires.

Annual prescribed fire, however, may have a detrimental effect on

sassafras fruit production [

50]. On some sites, repeated annual fires

may eventually eliminate sassafras [

19,

26,

40].

A regression equation to calculate the relationship of sassafras bark

thickness to stem diameter has been reported [

46]. An equation for

predicting standing sassafras dry weight (and therefore fuel loading)

from sassafras basal diameter has also been reported [

70].

- bibliographic citation

- Sullivan, Janet. 1993. Sassafras albidum. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Growth Form (according to Raunkiær Life-form classification)

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

More info on this topic. More info for the term:

phanerophyte Phanerophyte

- bibliographic citation

- Sullivan, Janet. 1993. Sassafras albidum. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Habitat characteristics

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

Sassafras occurs on nearly all soil types within its range, but is best

developed on moist, well-drained sandy loams in open woodlands [

41].

Optimum soil pH ranges from 6.0 to 7.0, but sassafras also occurs on

acid sands in eastern Texas [

41,

75]. It is intolerant of poorly drained

soils [

32]. Sassafras occurs along fence rows and on dry ridges and

upper slopes, particularly following fire [

41]. Sassafras occurs at

elevations ranging from Mississippi River bottomlands up to 4,000 feet

(1,220 m) in the southern Appalachian Mountains, occasionally up to

4,900 feet (1,500 m) [

24,

41].

- bibliographic citation

- Sullivan, Janet. 1993. Sassafras albidum. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Habitat: Cover Types

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

More info on this topic. This species is known to occur in association with the following cover types (as classified by the Society of American Foresters):

More info for the term:

hardwood 14 Northern pin oak

15 Red pine

16 Aspen

20 White pine - northern red oak - red maple

21 Eastern white pine

40 Post oak - blackjack oak

43 Bear oak

44 Chestnut oak

45 Pitch pine

46 Eastern redcedar

50 Black locust

52 White oak - black oak - northern red oak

53 White oak

55 Northern red oak

57 Yellow-poplar

60 Beech - sugar maple

61 River birch - sycamore

64 Sassafras - persimmon

70 Longleaf pine

71 Longleaf pine - scrub oak

75 Shortleaf pine

76 Shortleaf pine - oak

78 Virginia pine - oak

79 Virginia pine

80 Loblolly pine - shortleaf pine

81 Loblolly pine

83 Longleaf pine - slash pine

84 Slash pine

85 Slash pine - hardwood

88 Willow oak - water oak - diamondleaf oak

108 Red maple

110 Black oak

- bibliographic citation

- Sullivan, Janet. 1993. Sassafras albidum. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Habitat: Ecosystem

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

More info on this topic. This species is known to occur in the following ecosystem types (as named by the U.S. Forest Service in their Forest and Range Ecosystem [FRES] Type classification):

FRES10 White - red - jack pine

FRES12 Longleaf - slash pine

FRES13 Loblolly - shortleaf pine

FRES14 Oak - pine

FRES15 Oak - hickory

FRES16 Oak - gum - cypress

FRES17 Elm - ash - cottonwood

FRES18 Maple - beech - birch

FRES19 Aspen - birch

- bibliographic citation

- Sullivan, Janet. 1993. Sassafras albidum. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Habitat: Plant Associations

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

More info on this topic. This species is known to occur in association with the following plant community types (as classified by Küchler 1964):

More info for the term:

forest K083 Cedar glades

K089 Black Belt

K100 Oak - hickory forest

K101 Elm - ash forest

K104 Appalachian oak forest

K106 Northern hardwoods

K110 Northeastern oak - pine forest

K111 Oak - hickory - pine forest

K112 Southern mixed forest

- bibliographic citation

- Sullivan, Janet. 1993. Sassafras albidum. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Immediate Effect of Fire

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

More info for the terms:

low-severity fire,

prescribed fireLow-severity fires kill seedlings and small saplings. Moderate- and

high-severity fires injure mature trees, providing entry for pathogens

[

41,

75]. In oak savanna in Indiana, sassafras showed significantly less

susceptibility to low-severity fire than other species [

4]. Sassafras

exhibited 21 percent mortality of stems after prescribed fire in western

Tennessee. This was the lowest mortality of all hardwoods present.

Season of burning did not affect susceptibility [

17].

- bibliographic citation

- Sullivan, Janet. 1993. Sassafras albidum. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Importance to Livestock and Wildlife

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

More info for the term:

marshSassafras leaves and twigs are consumed by white-tailed deer in both

summer and winter. In some areas it is an important deer food [

41].

Sassafras leaf browsers include woodchucks, marsh rabbits, and black

bears [

83]. Rabbits eat sassafras bark in winter [

8]. Beavers will cut

sassafras stems [

15]. Sassafras fruits are eaten by many species of

birds including northern bobwhites [

58], eastern kingbirds, great

crested flycatchers, phoebes, wild turkeys, catbirds, flickers, pileated

woodpeckers, downy woodpeckers, thrushes, vireos, and mockingbirds.

Some small mammals also consume sassafras fruits [

16,

65,

75,

83].

For most of the above mentioned animals, sassafras is not consumed in

large enough quantities to be important. Carey and Gill [

9] rate its

value to wildlife as fair, their lowest rating.

- bibliographic citation

- Sullivan, Janet. 1993. Sassafras albidum. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Key Plant Community Associations

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

More info for the terms:

cover,

cover type,

treeThe sassafras-persimmon (Diospyros virginiana) cover type is a

successional type common on abandoned farmlands throughout its range.

Sassafras is a common component of the bear oak (Quercus ilicifolia)

type, which is a scrub type on dry sites along the Coastal Plain [

41].

In dry pine-oak forests, sassafras sprouts prolifically and is a

shrub-layer dominant [

72]. It achieves short-term dominance by producing

extensive thickets where few other woody plants can establish [

32].

In the northern parts of its range, sassafras occurs in the understory

of open stands of aspen (Populus spp.) and in northern pin oak (Q.

ellipsoidalis) stands [

41].

Common tree associates of sassafras not previously mentioned include

sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua), flowering dogwood (Cornus florida),

elms (Ulmus spp.), hickories (Carya spp.), and American beech (Fagus

grandifolia). Minor associates include American hornbeam (Carpinus

caroliniana), eastern hophornbeam (Ostrya virginiana), and pawpaw

(Asimina triloba). On poor sites, particularly in the Appalachian

Mountains, sassafras is frequently associated with black locust (Robinia

pseudoacacia), and sourwood (Oxydendron arboreum). In old fields with

deep soils, sassafras commonly grows with elms, ashes (Fraxinus spp.),

sugar maple (Acer saccharum), yellow-poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera), and

oaks [

41].

Sassafras is listed as a subdominant on subxeric and submesic sites in

the following classification: Landscape ecosystem classification for

South Carolina [

51].

- bibliographic citation

- Sullivan, Janet. 1993. Sassafras albidum. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Life Form

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

More info for the terms:

shrub,

treeTree, Shrub

- bibliographic citation

- Sullivan, Janet. 1993. Sassafras albidum. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Management considerations

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

More info for the term:

top-killOverstory removal often results in an increase in sassafras stems,

particularly by sprouting [

81]. Sassafras thickets may displace more

desirable species for a short time, but few sassafras stems will occupy

space in the overstory [

62]. Some herbicides control sassafras [

5].

Complete top-kill was achieved with injection of 2,4-D, picloram, and

glyphosate, with no apparent sprouting 2 years after treatment [

66].

Arsenal (an imidazolinone-based herbicide) also controls sassafras [

57].

Other herbicides do not control root sprouting [

33,

62].

Dense stands of sassafras are difficult to convert to pine or more

desirable hardwoods [

41]. Mowing is not effective in controlling

sassafras; root sprouts quickly replace or increase aboveground stems

[

5].

Sassafras is difficult to transplant because of the sparse, far-ranging

root system [

75].

In North Carolina, mechanical removal of all nondesirable stems

(intensive silvicultural cleaning) increased the amount of sassafras

browse available to white-tailed deer. . Prior to the cleaning,

sassafras was out of reach of the deer; sprouts arising after the

cleaning were within reach [

18].

Major diseases of sassafras include leaf blight, leaf spot, Nectria

canker and American mistletoe (Phoradendron flavescens) [

41].

Insect pests of sassafras are mostly minor; the most damaging insects

are the larvae of wood-boring weevils, gypsy moths, loopers, and

Japanese beetles [

41].

Sassafras is extremely sensitive to ozone [

43].

- bibliographic citation

- Sullivan, Janet. 1993. Sassafras albidum. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Nutritional Value

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

The nutritional value of sassafras winter twigs is fair [

67]. Seasonal

changes in nutrient composition of sassafras leaves and twigs has been

reported. Crude protein ranged from a high of 21.0 percent in April

leaves to a low of 6.1 in January twigs [

7].

Sassafras fruits are high in lipids and energy value [

85].

- bibliographic citation

- Sullivan, Janet. 1993. Sassafras albidum. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Occurrence in North America

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

AL AR CT DE FL GA IL IN IA KS

KY LA ME MD MA MI MS MO NH NJ

NY NC OH OK PA RI SC TN TX VT

VA WV

- bibliographic citation

- Sullivan, Janet. 1993. Sassafras albidum. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Other uses and values

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

Sassafras oil is extracted from the root bark for use by the perfume

industry, primarily for scenting soaps. It is also used as a flavoring

agent and an antiseptic [

41,

83]. Large doses of the oil may be narcotic

[

83]. Root bark is also used to make tea, which in weak infusions is a

pleasant beverage, but induces sweating in strong infusions. The leaves

can be used to flavor and thicken soups [

41,

83]. The mucilaginous pith

of the root is used in preparations to soothe eye irritations [

83].

Because of its durability, sassafras was used for dugout canoes by

Native Americans [

49].

- bibliographic citation

- Sullivan, Janet. 1993. Sassafras albidum. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Palatability

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

Palatability of sassafras to white-tailed deer is rated as good

throughout its range [

41].

- bibliographic citation

- Sullivan, Janet. 1993. Sassafras albidum. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Phenology

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

More info on this topic. Depending upon latitude, sassafras flowers from March to May [

24], and

fruits ripen from June to September [

68,

76,

77].

- bibliographic citation

- Sullivan, Janet. 1993. Sassafras albidum. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Plant Response to Fire

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

More info for the terms:

cover,

density,

frequency,

low-severity fire,

prescribed fire,

shrub,

wildfireSassafras occurs on charcoal hearths, which are patches of ground that

were used for charcoal making. These areas are characterized by very

poor soil structure. Sassafras on these sites shows poor growth [

10].

The effects of annual and 5-year interval prescribed burning over a

27-year period in Tennessee has been reported. After 6 years, sassafras

density was higher on annually burned plots than on unburned plots. The

highest sassafras density occurred on the 5-year interval plots [

80].

Sassafras gradually decreased with increasing canopy closure on the

5-year interval plots. By year 27, however, sassafras was eliminated

from the annually burned plots. Sassafras was also eliminated from

unburned plots; these plots developed closed canopies which are

unfavorable to sassafras [

19].

A large number of root sprouts occurred after sapling and small diameter

sassafras trees were top-killed by fire in an Illinois post oak (Quercus

stellata) stand [

12]. Sprout production by top-killed sassafras was

stimulated by prescribed fire, and greatly increased its cover in the

shrub layer [

13].

In Illinois, the number of small sassafras stems increased after a

single winter prescribed fire from 9 percent frequency to 36 percent

frequency. This increase was largely due to root sprouting by

top-killed plants. The number of sassafras seedlings also increased

after the same fire [

3]. In Virginia, in Table Mountain pine stands

that experienced a high-severity wildfire (98 percent top-kill),

sassafras increased from 0 to 12.1 in relative importance in 1 year.

Sassafras also increased on plots experiencing low-severity fire, but the

difference in importance value was not as great [

42].

In the absence of fire or other disturbances, sassafras frequency

decreases with increasing canopy closure; the number of new sassafras

seedlings also decreases with canopy closure [

2,

3].

Fire does not always lead to increased sassafras. Grelen [

40] reported

sassafras occurrence on unburned, young slash pine (Pinus elliottii)

plots but not on plots burned annually, biennially, or triennially in

March or May over the course of 12 years. In Florida, sassafras was

found on unburned, 15-year-old old fields, but not on oldfield plots

that were burned annually in February or March for 15 years [

26].

- bibliographic citation

- Sullivan, Janet. 1993. Sassafras albidum. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Post-fire Regeneration

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

More info for the terms:

crown residual colonizer,

ground residual colonizer,

root sucker,

tree Tree with adventitious-bud root crown/soboliferous species root sucker

Ground residual colonizer (on-site, initial community)

Initial-offsite colonizer (off-site, initial community)

Crown residual colonizer (on-site, initial community)

- bibliographic citation

- Sullivan, Janet. 1993. Sassafras albidum. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Regeneration Processes

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

More info for the terms:

cover,

hardwood,

litter,

natural,

seed,

stratificationSexual reproduction: Sassafras is sexually mature by 10 years of age,

and best seed production occurs between 25 and 50 years of age. Good

seed crops are produced every 1 to 2 years. Seeds are dispersed by

birds, water, and small mammals. Sassafras seeds are usually dormant

until spring, but some germination occurs in the fall immediately

following dispersal [

41]. Stratification in sand for 30 days at 41

degrees Fahrenheit (5 deg C) breaks the natural dormancy. Average

germination rate is around 85 percent [

83]. Since sassafras seeds are

relatively large, initial establishment is not highly dependent on

available soil nutrients. Other factors appear to play a greater role.

Seedling establishment occurred at higher than randomly expected

frequencies on microsites with greater ground cover, less light, or

deeper litter than other microsites [

14]. Sassafras seeds were found in

seed banks under red pine (Pinus resinosa), eastern white pine (P.

strobus), and Virginia pine (P. virginiana) stands [

6]. Sassafras

seedling reproduction is usually sparse and erratic in wooded areas. In

these areas, reproduction is usually vegetative [

32,

41].

Asexual reproduction: Sassafras forms dense thickets of root sprouts,

and young trees sprout from the stump [

41]. After clearcutting in

upland hardwood stands (Indiana), 86.5 percent of sassafras regeneration

was of seedling or seedling sprout origin; the remainder was of stump

sprout origin [

36].

- bibliographic citation

- Sullivan, Janet. 1993. Sassafras albidum. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Successional Status

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

More info on this topic. More info for the terms:

climax,

density,

forest,

frequency,

fresh,

fruit,

presence,

relative density,

shrub,

successionFacultative Seral Species

Sassafras is a frequent pioneer in old fields, and is a member of seral

stands in the Southeast [

41]. In old-field succession in Tennessee,

sassafras was a dominant member of a 15-year-old stand, and was not

present in a 48-year-old stand [

11]. In Virginia, sassafras persists to

mid-successional stages with black locust, Virginia pine, pitch pine,

eastern white pine, scarlet oak, blackjack oak, and post oak [

86]. It

also occurs in the canopy of old-growth forests in Illinois and Michigan

[

45,

71]. In the Michigan stands sassafras decreased in relative density

during a 20-year study [

45]. The persistence of sassafras into later

seres and climax stands may be a result of gap capture; in an old-growth

forest in Massachusetts, older sassafras trees appear to be associated

with hurricane and/or windthrow gaps. There was no evidence of fire

disturbance in this forest [

25]. Human activities and disturbance can

foster sassafras establishment in old-growth stands. The relatively

high abundance of sassafras under Virginia pine stands is associated

with a greater frequency of tree-fall gaps under Virginia pine than

under red pine or eastern white pine [

6]. Sassafras seedlings in Table

Mountain pine (Pinus pungens) stands are able to exploit canopy gaps at

the expense of Table Mountain pine [

87].

A detailed study of age structure in mixed forests in Virginia reveals

another role for sassafras. In 45- to 80-year-old mixed hardwoods and

mixed pine stands, sassafras seedlings and saplings occur in large

numbers. They rarely survive more than 30 years except on moist sites.

On relatively dry sites, sassafras does not survive long enough to

occupy upper canopy positions. But since sassafras sprouts

prolifically, there is a constant turnover of sassafras stems; older

stems die back and are replaced by new ramets. Sassafras in the

understory produces fruit under these conditions. In these stands,

sassafras is apparently functioning as a dominant shrub [

72].

In New Jersey, fragmented mixed oak forests were compared with forests

that were continuous. Sassafras was present in 63 percent of the

fragments, compared to 25 percent of the continuous stands [

37].

Sassafras exhibits a positive response to overstory removal; overstory

defoliation by gypsy moths results in an increase in the number of

sassafras stems [

1].

An unusual pure stand of sassafras was reported by Lamb [

59] in 1923.

This stand appeared to have remained essentially pure and intact for

over 100 years. The trees were described as fully mature, slow growing,

and the soil was very fertile. It is possible that the persistence of

this stand, and the competitive success of sassafras in pioneer

communities are related to the presence of terpenoid allelopathic

substances in sassafras leaves . These substances affect, among other

species, American elm (Ulmus americana) and box elder (Acer negundo).

The susceptibility of these species appears to be related to their habit

of germination immediately following dispersal. The toxic terpenes are

washed off of summer leaves and are less concentrated in winter and

spring when no fresh leaves are present [

31,

34].

- bibliographic citation

- Sullivan, Janet. 1993. Sassafras albidum. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Synonyms

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

S.variifolium (Salisb.) K. & Ze.

S. sassafras (L.) Karsten

S. officinale (Nees. & Eberm.)

S. triloba Raf.

S. triloba var. mollis Raf.

- bibliographic citation

- Sullivan, Janet. 1993. Sassafras albidum. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Taxonomy

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

More info for the term:

fernThe currently accepted scientific name of sassafras is Sassafras

albidum (Nutt.) Nees. [

41,

61].

Some authorities consider red sassafras [S. a. var. molle (Raf.) Fern.]

a distinct variety [

8,

30,

82]; other authors consider it synonymous with

the type variety [

53,

61,

68].

- bibliographic citation

- Sullivan, Janet. 1993. Sassafras albidum. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Value for rehabilitation of disturbed sites

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

Sassafras is used for restoring depleted soils in old fields [

41].

Sassafras occurs on sites that have been largely denuded of other

vegetation by the combination of frequent fire and toxic emissions from

zinc smelters. Sassafras persistence on these sites is attributed to

root sprouting; seedling reproduction is severely curtailed by the high

level of toxins in the soil [

52].

- bibliographic citation

- Sullivan, Janet. 1993. Sassafras albidum. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Wood Products Value

provided by Fire Effects Information System Plants

Sassafras wood is soft, brittle, light, and has limited commercial value

[

41]. It is durable, however, and is used for cooperage, buckets,

fenceposts, rails, cabinets, interior finish, and furniture [

24,

41,

83].

Carey and Gill [

9] rate its value for firewood as good, their middle

rating.

- bibliographic citation

- Sullivan, Janet. 1993. Sassafras albidum. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Associated Forest Cover

provided by Silvics of North America

Sassafras is included in only two forest cover types; however,

scattered trees of the species are found in many eastern forest

types (13). Sassafras-Persimmon (Society of American Foresters

Type 64) is a temporary type common on abandoned farmlands

throughout the range of sassafras, especially in the lower

Midwest and, to a limited extent, the mid-Atlantic States. It is

also present as successional stands on old fields in the

Southeastern States where pine usually predominates. Sassafras is

a minor component in Bear Oak (Type 43), a scrub type appearing

on dry sites along the Coastal Plain from New England southward

to New Jersey, and from northwestern New Jersey southward to

scattered localities in western Virginia and eastern West

Virginia. It is also prevalent in eastern and central

Pennsylvania.

Additional common associated tree species are sweetgum (Liquidambar

styraciflua), flowering dogwood (Cornus florida), elms

(Ulmus spp.), eastern redcedar (Juniperus

virginiana), hickories (Carya spp.), and American

beech (Fagus grandifolia). In fields with deeper soils it

grows with elms, ashes (Fraxinus spp.), sugar maple (Acer

saccharum), yellow-poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera), and

oaks (Quercus spp.).

Noteworthy minor tree associates are American hornbeam (Carpinus

caroliniana), eastern hophornbeam (Ostrya uirginiana),

and pawpaw (Asimina triloba). On poorer sites,

particularly in the Appalachian Mountains, it is frequently

associated with black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia), red

maple (Acer rubrum), sourwood (Oxydendrum arboreum),

and several oaks. At the northern edge of its range,

sassafras is found in the understory of aspen (Populus spp.) and

northern pin oak Quercus ellipsoidalis) stands (8).

- license

- cc-by-nc

- copyright

- USDA, Forest Service

Climate

provided by Silvics of North America

Average annual rainfall varies from 760 to 1400 mm (30 to 55 in)

within the humid range of sassafras. Of this, 640 to 760 mm (25

to 30 in) occur from April to August, the effective growing

season. At the northern limits of the range, the average annual

snowfall is between 76 to 102 cm (30 to 40 in), while in the

southern limits there may be only 2.5 cm (1 in) or less. The

average frost-free period is from 160 to 300 days. In January

average temperatures are -7° C (20° F) in the north and

13° C (55° F) in the south; the average July

temperatures vary from 21° to 27° C (70° to 80°

F).

- license

- cc-by-nc

- copyright

- USDA, Forest Service

Damaging Agents

provided by Silvics of North America

Sassafras is highly susceptible to fire

damage at any age. Light fires kill reproduction and small

saplings, and heavier burns injure large trees and provide entry

for pathogens. Sassafras may die if not well protected from

extremes of winter weather.

Foliage diseases are primarily the main damaging agents to

sassafras. Actinopelte dryina is largely a southern

fungus severely blighting the leaves. Mycosphaerella

sassafras is one of the most widely occurring leaf spots of

sassafras. A Nectria canker on trunks is fairly common in

the southern Appalachian region. Remarkably, few reports of

wood-rot fungi on sassafras have appeared in the literature (6).

Mistletoe (Phoradendron flavescens) has been reported

(8).

At least 15 species of insects attack sassafras, including root

borers, leaf feeders, and sucking insects. Except for small local

outbreaks, damage is relatively unimportant. From New York to

Florida, the larvae of a wood-boring weevil (Apteromechus

ferratus) kills trees up to 25 cm (10 in) in diameter. Two

leaf feeders, the gypsy moth (Lymantria dispar) and

looper (Epimecis hortaria), are found on sassafras in the

Northeastern United States and in the Atlantic States,

respectively. Sassafras is probably one of the favorite forest

tree foods of the Japanese beetle (Popillia japonica) (8).

- license

- cc-by-nc

- copyright

- USDA, Forest Service

Flowering and Fruiting

provided by Silvics of North America

Sassafras is dioecious.

Greenish-yellow flowers appear in March and April as the leaves

unfold. They develop in loose, drooping few-flowered axillary

racemes.

The fruit, 8 to 13 mm (0.3 to 0.5 in) long, is a single-seeded

dark-blue drupe. It matures in August and September of the first

year. The fruit is borne on a thickened red pedicel, and the

pulpy flesh covers the seed.

- license

- cc-by-nc

- copyright

- USDA, Forest Service

Genetics

provided by Silvics of North America

No genetic variation has been reported for sassafras.

- license

- cc-by-nc

- copyright

- USDA, Forest Service

Growth and Yield

provided by Silvics of North America

Sassafras varies in size from shrubs to

large trees with straight, clear trunks. The short, stout

branches spread at right angles to form a narrow flat-topped

crown. It may attain heights of 30 in (98 ft) on the best sites.

On poor sites, especially in the northern part of its range and

in Florida, sassafras is short and shrubby (12). Mature trees may

average only 15 to 20 cm (6 to 8 in) in d.b.h., with a maximum of

about 38 cm (15 in). Natural pruning is good in well-stocked

stands.

- license

- cc-by-nc

- copyright

- USDA, Forest Service

Reaction to Competition

provided by Silvics of North America

Sassafras is classed as

intolerant of shade at all ages. In forest stands, it usually

appears as individual trees or in small groups and is usually in

the dominant overstory. In the understory along the edges of

heavy stands it may live, but generally does not reach

merchantable size. If it becomes overtopped in mixed stands, it

is one of the first species to die. Allelopathy seems to be the

mechanism that allows sassafras, when it has invaded abandoned

fields, to maintain itself aggressively in a relatively pure and

mature forest (4). Field studies revealed that 10 species

consistently appear exclusively outside of clump canopies of

sassafras, and 7 other species predominated beneath the sassafras

canopy. Annual herbs were effectively excluded from the

understory flora. The allelopaths produced by sassafras are

believed to be 2-pinene, 3-phellandrene, eugenol, safrole,

citrol, and s-camphor (4).

- license

- cc-by-nc

- copyright

- USDA, Forest Service

Rooting Habit

provided by Silvics of North America

Sassafras roots are shallow and of the

prominent lateral type. The long laterals extend for a distance

with little change in diameter, branch occasionally, and form an

increasingly complex system (3). The laterals are practically all

from 15 to 50 cm (6 to 20 in) deep, rising and falling at various

intervals. Lateral spread is at the rate of 74 cm (29 in) per

year. The forming of a sucker results in the development of

feeding roots that otherwise would not be present on the lateral.

These roots arise near the sucker and on the larger part of the

lateral. They branch to very fine rootlets that are quite

important in the species adaptability to vigorous growth on

various types of soil.

- license

- cc-by-nc

- copyright

- USDA, Forest Service

Seed Production and Dissemination

provided by Silvics of North America

Seed production begins

when trees approach 10 years of age and is greatest when trees

are 25 to 50 years old.Good seed crops are produced every 1 or 2

years (2). There are 8,800 to 13,200 seeds/kg (4,000 to 6,000/lb)

and soundness is 35 percent. Birds are principal agents of seed

dissemination, with water a secondary agent. Some seeds probably

are distributed by small mammals.

- license

- cc-by-nc

- copyright

- USDA, Forest Service

Seedling Development

provided by Silvics of North America

Sassafras seed usually remains

dormant until spring, although some early maturing seed may

germinate in fall. The limit for storage of sassafras in the

forest floor is about 6 years (15). Stratification for 120 days

in moist sand at 5° C (41° F) breaks natural dormancy

(2). The best seedbed is a moist, rich, loamy soil with a

protective cover of leaves and litter. Germination is hypogeal.

Sassafras is intolerant of shade and reproduction is sparse and

erratic in wooded areas. Subsequent reproduction is usually

vegetative. The dense thickets often found in woods openings or

in old fields develop from root sprouts rather than seed. On good

sites where competition is not heavy, the sprouts may grow 3.7 in

(12 ft) in 3 years and sometimes are abundant (3). Elsewhere

growth is slow. Because sassafras grows in dense stands and

sprouts prolifically, it is a difficult cover type to convert to

pine or more desirable hardwoods.

- license

- cc-by-nc

- copyright

- USDA, Forest Service

Soils and Topography

provided by Silvics of North America

Sassafras can be found on virtually all soil types within

its range. It grows best in open woods on moist, well-drained,

sandy loam soils, but is a pioneer species on abandoned fields,

along fence rows, and on dry ridges and upper slopes, especially

following fire. In the South Atlantic and Gulf Coast States where

sites are predominately sandy soils, mature sassafras seldom

exceeds sapling size. On the Lake Michigan dunes of Indiana, it

grows on pure, shifting sand (5). It is also found on poor

gravelly soils and clay loams. Sassafras is most commonly found

growing on soils of the orders Entisols, Alfisols, and Ultisols.

Optimum soil pH is 6.0 to 7.0 (14). The species is found at

elevations varying from welldrained Mississippi River bottom

lands and loessial bluffs to 1220 m (4,000 ft) in the southern

Appalachian Mountains (10,11).

- license

- cc-by-nc

- copyright

- USDA, Forest Service

Special Uses

provided by Silvics of North America

The bark, twigs, and leaves of sassafras are important foods for

wildlife in some areas. Deer browse the twigs in the winter and

the leaves and succulent growth during spring and summer.

Palatability, although quite variable, is considered good

throughout the range. In addition to its value to wildlife,

sassafras provides wood and bark for a variety of commercial and

domestic uses. Tea is brewed from the bark of roots. The leaves

are used in thickening soups. The orange wood has been used for

cooperage, buckets, posts, and furniture (7). The oil is used to

perfume some soaps. Finally, sassafras is considered a good

choice for restoring depleted soils in old fields. It was

superior to black locust or pines for this purpose in Indiana and

Illinois (1).

- license

- cc-by-nc

- copyright

- USDA, Forest Service

Vegetative Reproduction

provided by Silvics of North America

Sassafras reproduces easily by

root sprouts. In parts of its ranges, sprouts rapidly restock

abandoned farmlands (3). Sprouting is prolific from the stumps of

young trees. Sassafras can be propagated fairly well from root

cuttings, but not from stem cuttings. Two cutting types-roots

with a stem sprout planted vertically and large roots planted

horizontally-were found to be superior (9).

- license

- cc-by-nc

- copyright

- USDA, Forest Service

Distribution

provided by Silvics of North America

Sassafras is native from southwestern Maine west to New York,

extreme southern Ontario, and central Michigan; southwest in

Illinois, extreme southeastern Iowa, Missouri, southeastern

Kansas, eastern Oklahoma, and eastern Texas; and east to central

Florida (8). It is now extinct in southeastern Wisconsin but is

extending its range into northern Illinois (5).

-The native range of sassafras

- license

- cc-by-nc

- copyright

- USDA, Forest Service

Brief Summary

provided by Silvics of North America

Lauraceae -- Laurel family

Margene M. Griggs

Sassafras (Sassafras albidum), sometimes called white

sassafras, is a medium-sized, moderately fast growing, aromatic

tree with three distinctive leaf shapes: entire, mittenshaped,

and threelobed. Little more than a shrub in the north, sassafras

grows largest in the Great Smoky Mountains on moist welldrained

sandy loams in open woodlands. It frequently pioneers old fields

where it is important to wildlife as a browse plant, often in

thickets formed by underground runners from parent trees. The

soft, brittle, lightweight wood is of limited commercial value,

but oil of sassafras is extracted from root bark for the perfume

industry.

- license

- cc-by-nc

- copyright

- USDA, Forest Service

Sassafras albidum

provided by wikipedia EN

Sassafras albidum (sassafras, white sassafras, red sassafras, or silky sassafras) is a species of Sassafras native to eastern North America, from southern Maine and southern Ontario west to Iowa, and south to central Florida and eastern Texas. It occurs throughout the eastern deciduous forest habitat type, at altitudes of up to 1,500 m (4,900 ft) above sea level.[3][4][5] It formerly also occurred in southern Wisconsin, but is extirpated there as a native tree.[6]

Description

Sassafras albidum is a medium-sized deciduous tree growing to 15–20 m (49–66 ft) tall, with a canopy up to 12 m (39 ft) wide,[7] with a trunk up to 60 cm (24 in) in diameter, and a crown with many slender sympodial branches.[8][9][10] The bark on trunk of mature trees is thick, dark red-brown, and deeply furrowed. The shoots are bright yellow green at first with mucilaginous bark, turning reddish brown, and in two or three years begin to show shallow fissures. The leaves are alternate, green to yellow-green, ovate or obovate, 10–15 cm (4–6 in) long and 5–10 cm (2–4 in) broad[11] with a short, slender, slightly grooved petiole. They come in three different shapes, all of which can be on the same branch; three-lobed leaves, unlobed elliptical leaves, and two-lobed leaves; rarely, there can be more than three lobes. In fall, they turn to shades of yellow, tinged with red. The flowers are produced in loose, drooping, few-flowered racemes up to 5 cm (2 in) long in early spring shortly before the leaves appear; they are yellow to greenish-yellow, with five or six tepals. It is usually dioecious, with male and female flowers on separate trees; male flowers have nine stamens, female flowers with six staminodes (aborted stamens) and a 2–3 mm style on a superior ovary. Pollination is by insects. The fruit is a dark blue-black drupe 1 cm (0.39 in) long containing a single seed, borne on a red fleshy club-shaped pedicel 2 cm (0.79 in) long; it is ripe in late summer, with the seeds dispersed by birds. The cotyledons are thick and fleshy. All parts of the plant are aromatic and spicy. The roots are thick and fleshy, and frequently produce root sprouts which can develop into new trees.[4][5][12]

Ecology

It prefers rich, well-drained sandy loam with a pH of 6–7, but will grow in any loose, moist soil. Seedlings will tolerate shade, but saplings and older trees demand full sunlight for good growth; in forests it typically regenerates in gaps created by windblow. Growth is rapid, particularly with root sprouts, which can reach 1.2 m (3.9 ft) in the first year and 4.5 m (15 ft) in 4 years. Root sprouts often result in dense thickets, and a single tree, if allowed to spread unrestrained, will soon be surrounded by a sizable clonal colony, as its roots extend in every direction and send up multitudes of shoots.[4][5][13]

S. albidum is a host plant for the caterpillar of the promethea silkmoth, Callosamia promethea.[14]

Laurel wilt

Laurel wilt is a highly destructive disease initiated when the invasive flying redbay ambrosia beetle (Xyleborus glabratus) introduces its highly virulent fungal symbiont (Raffaelea lauricola) into the sapwood of Lauraceae host shrubs or trees. Sassafras's volatile terpenoids may attract X. glabratus.[15] Sassafras is susceptible to laurel wilt and capable of supporting broods of X. glabratus. Underground transmission of the pathogen through roots and stolons of Sassafras without evidence of X. glabratus attack is suggested. Studies examining the insect's cold tolerance showed that X. glabratus may be able to move to colder northern areas where sassafras would be the main host. The exotic Asian insect is spreading the epidemic from the Everglades through the Carolinas in perhaps less than 15 years by the end of 2014.[16]

Uses

All parts of the Sassafras albidum plant have been used for human purposes, including stems, leaves, bark, wood, roots, fruit, and flowers. Sassafras albidum, while native to North America, is significant to the economic, medical, and cultural history of both Europe and North America. In North America, it has particular culinary significance, being featured in distinct national foods such as traditional root beer, filé powder, and Louisiana Creole cuisine. Sassafras albidum was an important plant to many Native Americans of the southeastern United States and was used for many purposes, including culinary and medicinal purposes, before the European colonization of North America. Its significance for Native Americans is also magnified, as the European quest for sassafras as a commodity for export brought Europeans into closer contact with Native Americans during the early years of European settlement in the 16th and 17th centuries, in Florida, Virginia, and parts of the Northeast.

Use by Native Americans

Sassafras with all 3 lobe variations seen.

Sassafras albidum was a well-used plant by Native Americans in what is now the Southeastern United States prior to the European colonization. The Choctaw word for sassafras is "Kvfi," and it was by them principally as a soup thickener.[17] It was known as "Winauk" in Delaware and Virginia and is called "Pauame" by the Timuca.

Some Native American tribes used the leaves of sassafras to treat wounds by rubbing the leaves directly into a wound, and used different parts of the plant for many medicinal purposes such as treating acne, urinary disorders, and sicknesses that increased body temperature, such as high fevers. They also used the bark as a dye, and as a flavoring.[18]

Sassafras wood was also used by Native Americans in the Southeastern United States as a fire-starter because of the flammability of its natural oils.[19]

In cooking, sassafras was used by some Native Americans to flavor bear fat, and to cure meats.[20] Sassafras is still used today to cure meats.[21] Use of filé powder by the Choctaw in the Southern United States in cooking is linked to the development of gumbo, a signature dish of Louisiana Creole cuisine.[22]

Modern culinary use and legislation

Sassafras twig and terminal bud

Sassafras albidum is used primarily in the United States as the key ingredient in home brewed root beer and as a thickener and flavouring in traditional Louisiana Creole gumbo.[23]

Filé powder, also called gumbo filé, for its use in making gumbo, is a spicy herb made from the dried and ground leaves of the sassafras tree. It was traditionally used by Native Americans in the Southern United States, and was adopted into Louisiana Creole cuisine. Use of filé powder by the Choctaw in the Southern United States in cooking is linked to the development of gumbo, the signature dish of Louisiana Creole cuisine that features ground sassafras leaves.[22] The leaves and root bark can be pulverized to flavor soup and gravy, and meat, respectively.[11]

Sassafras roots are used to make traditional root beer, although they were banned for commercially mass-produced foods and drugs by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 1960.[24] Laboratory animals that were given oral doses of sassafras tea or sassafras oil that contained large doses of safrole developed permanent liver damage or various types of cancer.[24] In humans, liver damage can take years to develop and it may not have obvious signs. Along with commercially available sarsaparilla, sassafras remains an ingredient in use among hobby or microbrew enthusiasts. While sassafras is no longer used in commercially produced root beer and is sometimes substituted with artificial flavors, natural extracts with the safrole distilled and removed are available.[25][26] Most commercial root beers have replaced the sassafras extract with methyl salicylate, the ester found in wintergreen and black birch (Betula lenta) bark.

Sassafras tea was also banned in the U.S. in 1977, but the ban was lifted with the passage of the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act in 1994.[24][27][28]

Safrole oil, aromatic uses, MDA

Safrole can be obtained fairly easily from the root bark of Sassafras albidum via steam distillation. It has been used as a natural insect or pest deterrent.[21] Godfrey's Cordial, as well as other tonics given to children that consisted of opiates, used sassafras to disguise other strong smells and odours associated with the tonics. It was also used as an additional flavouring to mask the strong odours of homemade liquor in the United States.[29]

Chemical structure of

safrole, a constituent of sassafras essential oil

Commercial "sassafras oil," which contains safrole, is generally a byproduct of camphor production in Asia or comes from related trees in Brazil. Safrole is a precursor for the manufacture of the drug MDMA, as well as the drug MDA (3-4 methylenedioxyamphetamine) and as such, its transport is monitored internationally. Safrole is a List I precursor chemical according to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration.

The wood is dull orange brown, hard, and durable in contact with the soil; it was used in the past for posts and rails, small boats and ox-yokes, though scarcity and small size limits current use. Some is still used for making furniture.[30]

History of commercial use

Europeans were first introduced to sassafras, along with other plants such as cranberries, tobacco, and American ginseng, when they arrived in North America.[20][31]

The aromatic smell of sassafras was described by early European settlers arriving in North America. According to one legend, Christopher Columbus found North America because he could smell the scent of sassafras.[29] As early as the 1560s, French visitors to North America discovered the medicinal qualities of sassafras, which was also exploited by the Spanish who arrived in Florida.[32] English settlers at Roanoke reported surviving on boiled sassafras leaves and dog meat during times of starvation.[33]

Upon the arrival of the English on the Eastern coast of North America, sassafras trees were reported as plentiful. Sassafras was sold in England and in continental Europe, where it was sold as a dark beverage called "saloop" that had medicinal qualities and used as a medicinal cure for a variety of ailments. The discovery of sassafras occurred at the same time as a severe syphilis outbreak in Europe, when little about this terrible disease was understood, and sassafras was touted as a cure. Sir Francis Drake was one of the earliest to bring sassafras to England in 1586, and Sir Walter Raleigh was the first to export sassafras as a commodity in 1602. Sassafras became a major export commodity to England and other areas of Europe, as a medicinal root used to treat ague (fevers) and sexually transmitted diseases such as syphilis and gonorrhea, and as wood prized for its beauty and durability.[34][35] Exploration for sassafras was the catalyst for the 1603 commercial expedition from Bristol of Captain Martin Pring to the coasts of present-day Maine, New Hampshire, and Massachusetts. During a brief period in the early 17th century, sassafras was the second-largest export from the British colonies in North America behind tobacco.[36]

Since the bark was the most commercially valued part of the sassafras plant due to large concentrations of the aromatic safrole oil, commercially valuable sassafras could only be gathered from each tree once. This meant that as significant amounts of sassafras bark were gathered, supplies quickly diminished and sassafras become more difficult to find. For example, while one of the earliest shipments of sassafras in 1602 weighed as much as a ton, by 1626, English colonists failed to meet their 30-pound quota. The gathering of sassafras bark brought European settlers and Native Americans into contact sometimes dangerous to both groups.[37] Sassafras was such a desired commodity in England, that its importation was included in the Charter of the Colony of Virginia in 1610.[38]

Through modern times the sassafras plant, both wild and cultivated, has been harvested for the extraction of safrole, which is used in a variety of commercial products as well as in the manufacture of illegal drugs like MDMA; yet, sassafras plants in China and Brazil are more commonly used for these purposes than North American Sassafras albidum.[39]

Gallery

See also

References

-

^ Stritch, L. (2018). "Sassafras albidum". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T62020487A62020489. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-1.RLTS.T62020487A62020489.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

-

^ The Plant List, Sassafras albidum

-

^ Flora of North America: Sassafras albidum

-

^ a b c U.S. Forest Service: Sassafras albidum (pdf file)

-

^ a b c Hope College, Michigan: Sassafras albidum

-

^ Griggs, Margene M. (1990). "Sassafras albidum". In Burns, Russell M.; Honkala, Barbara H. (eds.). Hardwoods. Silvics of North America. Washington, D.C.: United States Forest Service (USFS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Vol. 2 – via Southern Research Station.

-

^ "Sassafras albidum " (PDF). University of Florida Horticulture. US Forest Service - Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 18 November 2016.

-

^ Although some sources give 30 or 35 meters as the maximum height, as of 1982 the US champion is only 76 feet (23 meters) tall

-

^ "Sassafras albidum " (PDF). Kentucky Cooperative Extension Service.

-

^ Whit Bronaugh (May–June 1994). "The biggest sassafras". American Forests.

-

^ a b Elias, Thomas S.; Dykeman, Peter A. (2009) [1982]. Edible Wild Plants: A North American Field Guide to Over 200 Natural Foods. New York: Sterling. p. 125. ISBN 978-1-4027-6715-9. OCLC 244766414.

-

^ Flora of North America: Sassafras

-

^ Keeler, H. L. (1900). Our Native Trees and How to Identify Them. Charles Scribner's Sons, New York.

-

^ "Promethea silkmoth Callosamia promethea (Drury, 1773) | Butterflies and Moths of North America". www.butterfliesandmoths.org. Retrieved 2017-11-14.

-

^ Kendra, PE; Montgomery, WS; Niogret, J; Pruett, GE; Mayfield, AE; MacKenzie, M; Deyrup, MA; Bauchan, GR; Ploetz, RC; Epsky, ND (2014). "North American Lauraceae: terpenoid emissions, relative attraction and boring preferences of redbay ambrosia beetle, Xyleborus glabratus (coleoptera: curculionidae: scolytinae)". PLOS ONE. 9 (7): e102086. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9j2086K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0102086. PMC 4090202. PMID 25007073.

-

^ <http://www.ars.usda.gov/SP2UserFiles/Place/00000000/opmp/Redbay%20Laurel%20Wilt%20Recovery%20Plan%20January%202015.pdf> (search--resistan)

-

^ Freedman, Robert Louis (1976). "Native North American Food Preparation Techniques". Boletín Bibliográfico de Antropología Americana (1973-1979). Pan American Institute of Geography and History. 38 (47): 143. JSTOR 43996285., s.v. Soup Thickener (kombo ashish) Choctaw

-

^ Duke, James (December 15, 2000). The Green Pharmacy Herbal Handbook: Your Comprehensive Reference to the Best Herbs for Healing. Rodale Books. p. 195. ISBN 978-1579541842.

-

^ Bartram, William (December 1, 2002). William Bartram on the Southeastern Indians (Indians of the Southeast). University of Nebraska Press. p. 270. ISBN 978-0803262058.

-

^ a b Weatherford, Jack (September 15, 1992). Native Roots: How the Indians Enriched America. Ballantine Books. p. 52. ISBN 978-0449907139.

-

^ a b Duke, James (September 27, 2002). CRC Handbook of Medicinal Spices. CRC Press. p. 274. ISBN 978-0849312793.

-

^ a b Nobles, Cynthia Lejeune (2009), "Gumbo", in Tucker, Susan; Starr, S. Frederick (eds.), New Orleans Cuisine: Fourteen Signature Dishes and Their Histories, University Press of Mississippi, p. 110, ISBN 978-1-60473-127-9

-

^ "The Pot Thickens".

-

^ a b c Dietz, B; Bolton, Jl (Apr 2007). "Botanical Dietary Supplements Gone Bad". Chemical Research in Toxicology. 20 (4): 586–90. doi:10.1021/tx7000527. ISSN 0893-228X. PMC 2504026. PMID 17362034.

-

^ "CFR - Code of Federal Regulations Title 21".

-

^ Higgins, Nadia (August 1, 2013). Fun Food Inventions (Awesome Inventions You Use Every Day). 21st Century. p. 30. ISBN 978-1467710916.

-

^ Kwan, D; Hirschkorn, K; Boon, H (Sep 2006). "U.S. and Canadian pharmacists' attitudes, knowledge, and professional practice behaviors toward dietary supplements: a systematic review" (Free full text). BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 6: 31. doi:10.1186/1472-6882-6-31. PMC 1586212. PMID 16984649.

-

^ Barceloux, Donald (March 7, 2012). Medical Toxicology of Natural Substances: Foods, Fungi, Medicinal Herbs, Plants, and Venomous Animals. Wiley. ASIN B007KGA15Q.

-

^ a b Small, Ernest (September 23, 2013). North American Cornucopia: Top 100 Indigenous Food Plants. CRC Press. p. 606. ISBN 978-1466585928.

-

^ Missouriplants: Sassafras albidum

-

^ Sauer, Jonathan (1976). "Changing Perception and Exploitation of New World Plants in Europe, 1492-1800". In Fredi, Chiapelli (ed.). First Images of America: the Impact of the New World on the Old. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520030107.

-

^ Quinn, David (January 1, 1985). Set Fair for Roanoke: Voyages and Colonies, 1584-1606. The University of North Carolina Press. p. 175. ISBN 978-0807841235.

-

^ Stick, David (November 1, 1983). Roanoke Island: The Beginnings of English America. The University of North Carolina Press. p. 127. ISBN 978-0807841105.

-

^ Horwitz, Tony (2008). A Voyage Long and Strange: Rediscovering the New World. Henry Holt and Co. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-8050-7603-5.

-

^ Tiffany Leptuck, "Medical Attributes of 'Sassafras albidum' - Sassafras"], Kenneth M. Klemow, Ph.D., Wilkes-Barre University, 2003

-

^ Martin Pring, "The Voyage of Martin Pring, 1603", Summary of his life and expeditions at American Journeys website, 2012, Wisconsin Historical Society

-

^ Dugan, Holly (September 14, 2011). The Ephemeral History of Perfume: Scent and Sense in Early Modern England. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 83–95. ISBN 978-1421402345.

-

^ Bruce, Phillip. Economic History of Virginia in the Seventeenth Century. Vol. 2. Nabu Press. p. 613. ISBN 978-1271504855.

-

^ Blickman, Tom (February 3, 2009). "Harvesting Trees". Transational Institute. Transnational Institute. Retrieved April 4, 2015.

- license

- cc-by-sa-3.0

- copyright

- Wikipedia authors and editors

Sassafras albidum: Brief Summary

provided by wikipedia EN

Sassafras albidum (sassafras, white sassafras, red sassafras, or silky sassafras) is a species of Sassafras native to eastern North America, from southern Maine and southern Ontario west to Iowa, and south to central Florida and eastern Texas. It occurs throughout the eastern deciduous forest habitat type, at altitudes of up to 1,500 m (4,900 ft) above sea level. It formerly also occurred in southern Wisconsin, but is extirpated there as a native tree.

- license

- cc-by-sa-3.0

- copyright

- Wikipedia authors and editors