en

names in breadcrumbs

Silvertip sharks and great hammerheads, are important predators of spotted eagle rays. Sharks have also been reported to follow spotted eagle rays during the birthing season in order to feed on newborn pups. Similar to other cartilaginous fishes, spotted eagle rays have a network of electrosensory organs on their snout that helps them detect potential predators. In addition, all fish have a lateral line system that allows them to detect changes in temperature and pressure in their immediate environment.

Known Predators:

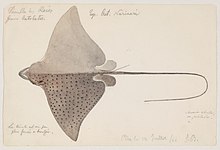

Many eagle rays (including Aetobatus narinari) have a flattened snout that protrudes from the pectoral disc. Aetobatus narinari can be distinguished by a pectoral disc that is approximately twice as wide as it is long. The posterior edge of the pectoral fins are concave and very angular tips (Bester, 2008). The ventral surface is white and the dorsal surface is either blue or black and peppered with white spots and rings. It has rounded pelvic fins and a very small dorsal fin but lacks a caudal fin all together. The pectoral fins make up a majority of the pectoral disc and are acutely angled at the lateral tips. Aetobatus narinari possesses stinging spines, which can be found behind the dorsal fin, and a slender whip-like tail that can be up to three times as long as the width of the pectoral disc (Bester, 2008). It can weigh as much as 230 kg and can reach disc widths of up to 330 cm; however, the average disc width of A. narinari is 180 cm. Sexual dimorphism has not been reported in this species.

Range mass: 230 (high) kg.

Range length: 330 (high) cm.

Average length: 180 cm.

Other Physical Features: ectothermic ; heterothermic ; bilateral symmetry ; venomous

There is no information available regarding the average life span of Aetobatus narinari.

Aetobatus narinari is a reef associated ray and is commonly found along reef edges. It prefers warm water with soft bottoms consisting usually of mud, sand and gravel. Aetobatus narinari spends most of its time around 60 m deep but may dive up 80 m deep. It is often seen in beach areas as well as estuaries and mangrove swamps throughout tropical regions of the world.

Range depth: 1 to 80 m.

Average depth: 60 m.

Habitat Regions: saltwater or marine

Aquatic Biomes: pelagic ; reef ; coastal ; brackish water

Other Habitat Features: estuarine

Aetobatus narinari (spotted eagle ray) is globally distributed throughout tropical and warm temperate waters as far north as North Carolina, U.S.A. in the summer and as far south as Brazil. This species has also been known to inhabit the red sea and oceanic waters surrounding the Hawaiian islands. Its latitudinal range spans from 43°N to 32°S.

Biogeographic Regions: indian ocean; atlantic ocean ; pacific ocean

Other Geographic Terms: cosmopolitan

Primary prey of Aetobatus narinari consists of crustaceans, molluscs, echinoderms and polychaete worms. It is also known to occasionally consume smaller fish as well. When a prey item is captured, A. narinari crushes it between the upper and lower dental plates. Prior to ingestion, it uses 6 to 7 rows of papillae located on the roof of the mouth to remove indigestible items (e.g., shell and bone).

Animal Foods: fish; mollusks; aquatic or marine worms; aquatic crustaceans; echinoderms

Primary Diet: carnivore (Eats non-insect arthropods, Molluscivore , Vermivore)

Spotted eagle rays are predators of a variety of marine invertebrates and are important prey for a number of shark species. Information regarding parasites specific to this species is limited, however, ectoparasites such as marine leeches, are thought to be common. Endoparasites such as trematodes and tapeworms, are common as well.

Commensal/Parasitic Species:

Although spotted eagle rays are sometimes targeted for their meat, detailed accounts of captures are limited.

Positive Impacts: food

Spotted eagle rays are capable of stinging humans with their venomous spine, which occasionally results in death. There are a few documented cases of spotted eagle rays jumping out of the water and onto boats.

Negative Impacts: injures humans (bites or stings, venomous )

Aetobatus narinari is ovoviviparous, as its eggs develop inside the uterus and hatch within the mother prior to emerging. Once the embryos are released from the egg, they are nourished by a yolk sac rather than through a placental connection with the mother. Little is known of the development of A. narinari. Newborn pups generally measure 17 to 35 cm in disc width.

As with all cartilaginous fishes, Aetobatus narinari has specialized electrosensory organs commonly referred to as Ampullae of Lorenzini. These sensory organs consists of jelly-filled pores that create an electrosensory network along the snout, which increases the sensitivity of A. narinari to prey movement, as muscle contractions create an electrical pulse. In general, elasmobranchs have excellent vision and olfactory perception, which help them avoid predators and detect prey. In addition, all fish have a lateral line system that allows them to sense changes in pressure and temperature in the surrounding environment. There is no information available regarding intraspecific communication in Aetobatus narinari.

Perception Channels: visual ; chemical ; electric

Aetobatus narinari is listed as near threatened on the IUCN's Red List of Theatened Species. Although detailed accounts of its capture are limited, small litter sizes, schooling tendencies and inshore habitat preferences make this species particularly vulnerable to overfishing. In addition, in shore fishing gear (beach seine, gillnet, trawl etc.) is widely available and the practice of in shore fishing is largely unregulated, resulting in the IUCN's near threatened listing. In shore fishing pressure on A. narinari is particularly intense in southeast Asia. As a result, the IUCN classifies this species as vulnerable in this part of its geographic range.

Aetobatus narinari is protected in Australia, the Maldives, and Florida. Much of its geographic range in Australia's coastal waters includes the Great Barrier Reef, a third of which is protected against fishing. In addition, the use of turtle exclusion devices is mandatory in prawn trawl fisheries of Northern Australia, which likely decreases by-catch. The export of rays and ray skins was banned in the Maldives in 1995 and 1996, respectively. In addition, elasmobranchs are protected in marine reserves surrounding the Maldives that attract ecotourists interested in marine wildlife. Finally, A. narinari cannot be harvested, possessed, landed, purchased, sold or exchanged in Florida.

US Federal List: no special status

CITES: no special status

State of Michigan List: no special status

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: near threatened

Prior to mating, multiple Aetobatus narinari males chase a single females while grasping her dorsum with their upper tooth plate. A single male then grabs one of the female's pectoral fins and roles her into a vertical position and inserts his claspers. Copulation can last from 20 to 90 seconds and females have been known to repeat this process up to 4 times over a relatively short period of time. The mating system of Aetobatus narinari has not been clearly defined; however, the competitive behavior of males prior to copulations suggests polygyny.

Breeding season in Aetobatus narinari varies by location but usually occurs during mid-summer. Typically, females give birth to 2 pups per pregnancy but can have between 1 and 4. Gestation lasts for approximately 12 months, but can be short as 8 months depending on location and mean water temperature during gestation. Evidence suggests that A. narinari becomes sexually mature when they grow to about half their maximum disc width, which typically occurs between 4 and 6 years of age.

Breeding season: Aetobatus narinari breeds during summer.

Range number of offspring: 1 to 4.

Average number of offspring: 2.

Range gestation period: 8 to 12 months.

Average gestation period: 12 months.

Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female): 4 to 6 years.

Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male): 4 to 6 years.

Key Reproductive Features: seasonal breeding ; sexual ; fertilization (Internal ); ovoviviparous

Other than the in-utero protection and yolk sac a mother provides her young prior to birth, there is no information available regarding parental care in Aetobatus narinari.

Parental Investment: female parental care ; pre-hatching/birth (Provisioning: Female, Protecting: Female)

The spotted eagle ray (Aetobatus narinari) is a cartilaginous fish of the eagle ray family, Aetobatidae. As traditionally recognized, it is found globally in tropical regions, including the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Recent authorities have restricted it to the Atlantic (including the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico) with other populations recognized as the ocellated eagle ray (A. ocellatus) and Pacific white-spotted eagle ray (A. laticeps). Spotted eagle rays are most commonly seen alone, but occasionally swim in groups. They are ovoviviparous, the female retaining the eggs then releasing the young as miniature versions of the parent.

This ray can be identified by its dark dorsal surface covered in white spots or rings. Near the base of the ray's relatively long tail, just behind the pelvic fins, are several venomous, barbed stingers. Spotted eagle rays commonly feed on small fish and crustaceans, and will sometimes dig with their snouts to look for food buried in the sand of the sea bed. These rays are commonly observed leaping out of the water, and on at least two occasions have been reported as having jumped into boats, in one incident resulting in the death of a woman in the Florida Keys. The spotted eagle ray is hunted by a wide variety of sharks. The rays are considered near threatened on the IUCN Red List. They are fished mainly in Southeast Asia and Africa, the most common market being in commercial trade and aquariums. They are protected in the Great Barrier Reef.

The spotted eagle ray was first described by Swedish botanist Bengt Anders Euphrasén as Raja narinari in 1790 from a specimen collected at an unknown location (possibly the coast of Brazil) during a trip he made to the Antilles, and was later classified as Stoasodon narinari.[1][2][3] Its current genus name is Aetobatus, derived from the Greek words aetos (eagle) and batis (ray). The spotted eagle ray belongs to the Myliobatidae, which includes the well known manta ray. Most rays in the family Myliobatidae swim in the open ocean rather than close to the sea floor.[2]

Although traditionally considered to have a circumglobal distribution in tropical oceans throughout the world, recent authorities have restricted the true Aetobatus narinari to the Atlantic Ocean based on genetic and morphologic evidence.[4][5][6][7] The Indo-Pacific population is Aetobatus ocellatus and the East Pacific is Aetobatus laticeps.[6][7]

The spotted eagle ray has many different common names, including white-spotted eagle ray, bonnet skate, bonnet ray, duckbill ray and spotted duck-billed ray.[8][9][10]

Spotted eagle rays have flat disk-shaped bodies, deep blue or black with white spots on top with a white underbelly, and distinctive flat snouts similar to a duck's bill.[11] Their tails are longer than other rays and may have 2–6 venomous spines, behind the pelvic fins. The front of the wing-like pectoral disk has five small gills in its underside.[12]

Mature spotted eagle rays can be up to 5 meters (16 ft) in length; the largest spotted eagle rays have a wingspan of up to 3 meters (10 ft) and a mass of 230 kilograms (507 lb).[13][14]

One male, or sometimes several, will pursue a female. When one of the males approaches the female, he uses his upper jaw to grab her dorsum. The male will then roll the female over by grabbing one of her pectoral fins, which are located on either side of her body. Once he is on her ventral side, the male puts a clasper into the female, connecting them venter to venter, with both undersides together. The mating process lasts for 30–90 seconds.[2]

The spotted eagle ray develops ovoviviparously; the eggs are retained in the female and hatch internally, feeding off a yolk sac until live birth.[2] After a gestation period of one year the mother ray will give birth to a maximum of four pups.[1] When the pups are first born, their discs measure from 17–35 centimeters (6.7–13.8 in) across.[2] The rays mature in 4 to 6 years.[1][15]

Spotted eagle ray preys mainly upon bivalves, crabs, whelks and other benthic infauna. They also feed on mollusks (such as the queen conch)[16] and crustaceans, particularly malacostracans,[17][18] as well as echinoderms, polychaete worms,[19] hermit crabs,[20] shrimp, octopuses, and some small fish.[21]

The spotted eagle ray's specialized chevron-shaped tooth structure helps it to crush the mollusks' hard shells.[13][14] The jaws of these rays have developed calcified struts to help them break through the shells of mollusks, by supporting the jaws and preventing dents from hard prey.[22] These rays have the unique behavior of digging with their snouts in the sand of the ocean. [23] While doing this, a cloud of sand surrounds the ray and sand spews from its gills. One study has shown that there are no differences in the feeding habits of males and females or in rays from different regions of Australia and Taiwan.[18]

Spotted eagle rays prefer to swim in waters of 24 to 27 °C (75 to 81 °F). Their daily movement is influenced by the tides; one tracking study showed that they are more active during high tides. Uniquely among rays they dig with their snouts in the sand,[23] surrounding themselves in a cloud of sand that spews from their gills. They also exhibit two motions in which the abdomen and the pectoral fins are moved rapidly up and down: the pelvic thrust and the extreme pelvic thrust. The pelvic thrust is usually performed by a solitary ray, and repeated four to five times rapidly. The extreme pelvic thrust is most commonly observed when the ray is swimming in a group, from which it will separate itself before vigorously thrusting with its pectoral fins. The rays also performs dips and jumps; in a dip the ray will dive and then come back up rapidly, perhaps as many as five times consecutively. There are two main types of jump: in one, the ray propels itself vertically out of the water, to which it returns along the same line; the other is when the ray leaps at a 45 degree angle, often repeated multiple times at high speeds. When in shallow waters or outside their normal swimming areas the rays are most commonly seen alone, but they do also congregate in schools. One form of travelling is called loose aggregation, which is when three to sixteen rays are swimming in a loose group, with occasional interactions between them. A school commonly consists of six or more rays swimming in the same direction at exactly the same speed.[24]

The dorsal spots make the spotted eagle ray an aquarium attraction, although because of its large size it is likely kept only at public aquariums.[8] There are no target fisheries for the spotted eagle ray, but it is often eaten after being caught unintentionally as bycatch.[8] There have been several reported incidents of spotted eagle rays leaping out of the water onto boats and landing on people.[25][26] Nevertheless, spotted eagle rays do not pose a significant threat to humans, as they are shy and generally avoid human contact.[2] Interactions with an individual snorkeler in the Caribbean has been reported especially in Jamaica involving one, two and even three spotted eagle rays. The rays may exhibit a behavior similar to human curiosity which allows the snorkeler to observe the eagle ray who may slow down so as to share more time with the much slower human observer if the human observer appears to be unthreatening or interesting to the spotted eagle ray.

Spotted eagle rays, in common with many other rays, often fall victim to sharks such as the tiger shark, the lemon shark, the bull shark, the silver tip shark, and the great hammerhead shark.[27][28] A great hammerhead shark has been observed attacking a spotted eagle ray in open water by taking a large bite out of one of its pectoral fins, thus incapacitating the ray. The shark then used its head to pin the ray to the bottom and pivoted to take the ray in its jaws, head first.[29] Sharks have also been observed to follow female rays during the birthing season, and feed on the newborn pups.[2]

As other rays, spotted eagle rays are host to a variety of parasites. Internal parasites include the gnathostomatid nematode Echinocephalus sinensis in the spiral intestine.[30] External parasites include the monocotylid monogeneans Decacotyle octona,[31] Decacotyle elpora[31] and Thaumatocotyle pseudodasybatis[31][32] on the gills.

As traditionally defined, spotted eagle rays are found globally in tropical regions from the Indo-Pacific region from the western Pacific Ocean, the Indian Ocean, and the western Atlantic Ocean.[33]

They are found in shallow coastal water by coral reefs and bays, in depths down to 80 meters (262 ft).[13] Spotted eagle rays are found in warm and temperate waters worldwide. In the western Atlantic Ocean it is found off the eastern coast of United States of America, the Gulf Stream, the Caribbean, and down past the southern part of Brazil. In the Indian Ocean, it is found from the Red Sea down to South Africa and eastward to the Andaman Sea. In the Western Pacific Ocean it can be found near Japan and north of Australia.[2] In the Central Pacific Ocean, it can be found throughout the Hawaiian Islands. In the Eastern-Pacific Ocean, it is found in the Gulf of California down through Puerto Pizarro, an area that includes the Galapagos Islands. Spotted eagle rays are most commonly seen in bays and reefs. They spend much of their time swimming freely in open waters, generally in schools close to the surface, and can travel long distances in a day.[2]

Within these regions, there are significant variations in genetics and morphology.[6][4][5] As a consequence, recent authorities have split it into three: This restricts the true spotted eagle ray (A. narinari) to the Atlantic, while the Indo-Pacific population is the ocellated eagle ray (A. ocellatus) and the East Pacific is the Pacific white-spotted eagle ray (A. laticeps).[6][7]

The spotted eagle ray is included in the IUCN's Red List as "near threatened". The rays are caught mainly in Southeast Asia and Africa. They are also common in commercial marine life trade and are displayed in aquariums. Among the many efforts to help protect this species, South Africa's decision to deploy fewer protective shark nets has reduced the number of deaths caused by entanglement. South Africa has also placed restrictions on the number of rays that can be bought per person per day. In the U.S. state of Florida, the fishing, landing, purchasing and trading of spotted eagle ray are outlawed. This ray is also protected in the Great Barrier Reef on the eastern coast of Australia.[1]

In Europe there is a breeding program managed by the EAZA for spotted eagle rays to reduce the amount of wild caught individuals needed by public aquaria. From the start until 2018 Burgers' Zoo in the Netherlands kept the studbook. Since 2018, Wroclaw Zoo in Poland is the new studbook keeper. Burgers' Zoo was also the first place in Europe to breed with the species and in 2018 was the most successful breeder worldwide with over 55 births.[34][35][36]

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) {{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) The spotted eagle ray (Aetobatus narinari) is a cartilaginous fish of the eagle ray family, Aetobatidae. As traditionally recognized, it is found globally in tropical regions, including the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Recent authorities have restricted it to the Atlantic (including the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico) with other populations recognized as the ocellated eagle ray (A. ocellatus) and Pacific white-spotted eagle ray (A. laticeps). Spotted eagle rays are most commonly seen alone, but occasionally swim in groups. They are ovoviviparous, the female retaining the eggs then releasing the young as miniature versions of the parent.

This ray can be identified by its dark dorsal surface covered in white spots or rings. Near the base of the ray's relatively long tail, just behind the pelvic fins, are several venomous, barbed stingers. Spotted eagle rays commonly feed on small fish and crustaceans, and will sometimes dig with their snouts to look for food buried in the sand of the sea bed. These rays are commonly observed leaping out of the water, and on at least two occasions have been reported as having jumped into boats, in one incident resulting in the death of a woman in the Florida Keys. The spotted eagle ray is hunted by a wide variety of sharks. The rays are considered near threatened on the IUCN Red List. They are fished mainly in Southeast Asia and Africa, the most common market being in commercial trade and aquariums. They are protected in the Great Barrier Reef.