en

names in breadcrumbs

In the past the Mediterranean monk seal was killed for its skin and body parts, which were said to provide protection against a variety of medical problems. The seal has also been killed for food.

This seal is one of the world's rarest mammals, and it is on the list of the 20 most endangered species.

Another issue with the seal is that it is very sensitive to disturbances. Pregnant females are especially sensitive and will often abort when disturbed.

When communicating with each other they make very high pitched sounds. This is done mainly while in the water to let each other know if something is wrong or if danger is approaching.

Communication Channels: acoustic

Perception Channels: visual ; tactile ; acoustic ; chemical

Fewer than 500 individuals of Mediterranean monk seals remain in the world today. They have been killed by fisherman who see them as competition, and many have been lost due to being caught in fishermans' nets. Pollution and boat traffic are also a problem for this species. Pollution comes mainly from human waste. This waste gets into the water in which the seals live and into the food that they eat. The problem with boat traffic is from a lot of boats being in the same area that the seals occupy, resulting at worst in collisions between seals and boats

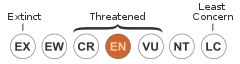

US Federal List: endangered

CITES: appendix i

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: critically endangered

The only way that Mediterranean monk seals affect humans negatively is that compete with fishermen. These seals are mainly harmless otherwise.

Mediterranean monk seals are diurnal. They feed in shallow coastal waters on a large variety of fish. This includes eels, sardines, tuna, lobsters, flatfish, and mullets. They also feed on cephalopods such as octopuses.

Animal Foods: fish; mollusks

Primary Diet: carnivore (Piscivore )

Monachus monachus, also known as the Mediterranean Monk Seal, is found around the Mediterranean Sea region and the Northwest African Coast. There are populations that are located in Mauritania/Western Sahara, Greece, and Turkey. Small numbers have also been seen in Morocco, Algeria, Libya, the Portuguese Desertas Islands, Croatia, and Cyprus.

Biogeographic Regions: palearctic (Native ); ethiopian (Native ); atlantic ocean (Native )

Mediterranean monk seals are usually found along coastal waters, especially on the coastlines of islands. They are sometimes found in caves with submarine entrances when the female is giving birth and just to get away from other disturbances, such as boats.

Habitat Regions: temperate ; saltwater or marine

Aquatic Biomes: coastal

These seals live up to 30 years of age.

Typical lifespan

Status: wild: 30 (high) years.

Average lifespan

Status: captivity: 23.7 years.

Adult Mediterranean monk seals can be any color from dark brown or black to light grey. They are usually light gray along the belly. Pups have a black woolly coat and a white or yellow patch on the belly. They molt at about 4-6 weeks and their black woolly coat is replaced by a silvery gray coat that can darken over time.

Adult males are on average about 2.4m in length and females are slightly shorter. Males weigh about 315 kg and females weigh about 300 kg.

Average mass: 300-315 kg.

Average length: 2.4 m.

Other Physical Features: endothermic ; homoiothermic; bilateral symmetry

Sexual Dimorphism: male larger

Average mass: 275000 g.

Mediterranean monk seals mate during the months of September-November. Mating usually takes place in the water. They reproduce very slowly starting at the age of 4. The time between births is 13 months, and the gestation period is 11 months. Pups are born about 80-100 cm long and weigh 17-24 kg.

Sexual maturity is reached at about 4-6 years of age.

When females give birth, they go on the beach or in caves. A female will usually remain on the beach or in the cave nursing and protecting the pup for up to six weeks. During this time, the female must live off of stored fat because she never leaves the pup, not even to feed herself. The pup may remain with its mother for as long as 3 years even after weaning.

Breeding season: Mediterranean monk seals mate during the months of September-November.

Average number of offspring: 1.

Average gestation period: 11 months.

Range weaning age: 6 (high) weeks.

Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female): 4 to 6 years.

Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male): 4 to 6 years.

Key Reproductive Features: iteroparous ; seasonal breeding ; gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); sexual ; viviparous

Average birth mass: 19000 g.

Average gestation period: 289 days.

Average number of offspring: 1.

Parental Investment: precocial ; pre-fertilization (Provisioning, Protecting: Female); pre-hatching/birth (Provisioning: Female, Protecting: Female); pre-weaning/fledging (Provisioning: Female, Protecting: Female); post-independence association with parents

Ağqarın Aralıq dənizi suitisi (lat. Monachus monachus), Yırtıcılar dəstəsindən heyvan.Yayılması Türkiyə(Foça),Yunanıstan,Tunis,Mərakeş,İspaniya

Ar reunig manac'h (Monachus monachus) a zo ur bronneg mor hag a vev er mor Kreizdouarel hag evit un darn war aodoù Afrika ar C'hornaoueg (Maouritania) ha Madeira. En arvar bras emañ, ne vanfe ken nemet ur 600 bennak anezho.

La foca monjo del Mediterrani o vell marí[1] (Monachus monachus) és una espècie de foca caputxina (gènere Monachus). Es tracta d'una espècie amenaçada en perill d'extinció, de la qual se suposa que, segons les darreres estimacions del 2013, queden uns 600 individus.

L'àrea de difusió comprenia antigament tot el Mediterrani, el mar Negre i les costes atlàntiques d'Espanya, Portugal, el Marroc, Mauritània, Madeira i les Canàries. Durant el segle XX, el seu hàbitat s'ha reduït considerablement i actualment només sobreviuen algunes colònies a Grècia, a les illes de la costa de Croàcia, a Turquia, a les illes Chafarinas, a Madeira, al Marroc i a Mauritània. L'any 1992, fou abatuda una femella a les illes Chafarines i durant uns anys es va creure que, d'aquesta espècie, a tot l'espanyol només en quedava un exemplar, un mascle anomenat Peluso, a qui posteriorment també es va perdre la pista.

El vell marí és una espècie costanera que pot allunyar-se bastants quilòmetres a la recerca d'aliment. Actualment, ocupen costes rocalloses poc alterades i amb nombroses coves que utilitzen per a descansar i donar a llum les seves cries. Antigament, les colònies també se situaven en platges sorrenques. D'adults, assoleixen des de 80 cm a uns 2,4 m de longitud i arriben als 320 kg de pes, amb les femelles lleugerament més petites que els mascles. El seu pelatge és marró o gris fosc, amb el ventre una mica més pàl·lid. Les cries acostumen a néixer cap a la tardor i entren a l'aigua unes dues setmanes després.

Considerant que a l'antiga àrea de distribució del vell marí existeixen nombroses zones protegides en bon estat de conservació, la Direcció General de Conservació de la Natura del Ministeri de Medi Ambient i la Viceconselleria de Medi Ambient de Canàries han engegat, amb fons comunitaris LIFE, el Projecte per a la Recuperació del Vell marí a Espanya, que encara es troba en la fase d'estudis de viabilitat i que recentment ha rebut el vistiplau de la Unió Mundial per a la Natura (UICN). La Universitat de Barcelona i la Universitat de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria són les institucions científiques que duen a terme aquest estudi.

L'objectiu final d'aquest projecte és recuperar l'espècie per a la fauna espanyola mitjançant la seva reintroducció a les illes Canàries orientals. Aquestes illes han estat seleccionades per trobar-se situades a mig camí geogràficament entre la colònia de Madeira i la de Cap Blanc, amb la qual cosa es restabliria el corredor natural genètic entre els dos nuclis, que ara estan aïllats; de fet, cada any apareix algun jove en dispersió.

A més, aquestes illes tenen un adequat nombre d'espais naturals protegits, amb un bon nivell de conservació i reuneixen prou capacitat biològica per a mantenir una població de foques, donada la seva riquesa en espècies presa potencials i la seva baixa contaminació marina.

Un altre projecte similar és el Pla d'Acció Internacional per a la Recuperació del Vell marí a l'Atlàntic Oriental, dins del conveni Espècies Migratòries o conveni de Bonn, al qual a més d'Espanya, participen Portugal, Marroc i Mauritània, així com diverses entitats, com la Fundació CBD-Hàbitat o l'ONG Annajah. Així mateix, el Fons per al Vell Marí (FFM) realitza un seguiment de l'espècie i campanyes de sensibilització al Marroc, Algèria i Tunísia. Per la seva banda, un projecte de la Fundació Territori i Paisatge, creada per Caixa Catalunya, va fer un pla perquè en 8 anys aquesta espècie habités de nou la costa catalana.[2][3] La situació actual de Caixa Catalunya fa que el projecte estigui aparcat sine die.[4]

La foca monjo del Mediterrani o vell marí (Monachus monachus) és una espècie de foca caputxina (gènere Monachus). Es tracta d'una espècie amenaçada en perill d'extinció, de la qual se suposa que, segons les darreres estimacions del 2013, queden uns 600 individus.

L'àrea de difusió comprenia antigament tot el Mediterrani, el mar Negre i les costes atlàntiques d'Espanya, Portugal, el Marroc, Mauritània, Madeira i les Canàries. Durant el segle XX, el seu hàbitat s'ha reduït considerablement i actualment només sobreviuen algunes colònies a Grècia, a les illes de la costa de Croàcia, a Turquia, a les illes Chafarinas, a Madeira, al Marroc i a Mauritània. L'any 1992, fou abatuda una femella a les illes Chafarines i durant uns anys es va creure que, d'aquesta espècie, a tot l'espanyol només en quedava un exemplar, un mascle anomenat Peluso, a qui posteriorment també es va perdre la pista.

El vell marí és una espècie costanera que pot allunyar-se bastants quilòmetres a la recerca d'aliment. Actualment, ocupen costes rocalloses poc alterades i amb nombroses coves que utilitzen per a descansar i donar a llum les seves cries. Antigament, les colònies també se situaven en platges sorrenques. D'adults, assoleixen des de 80 cm a uns 2,4 m de longitud i arriben als 320 kg de pes, amb les femelles lleugerament més petites que els mascles. El seu pelatge és marró o gris fosc, amb el ventre una mica més pàl·lid. Les cries acostumen a néixer cap a la tardor i entren a l'aigua unes dues setmanes després.

Tuleň středomořský (Monachus monachus) patří do nevelké skupiny mořských vodních savců – ploutvonožců. Jeho domovem bylo kdysi celé Středozemní moře a přilehlé oblasti. Rybáři však v tuleních viděli konkurenci, která jim snižuje úlovky a tak je začali hubit, často velmi nevybíravými metodami. To vedlo k vymizení tuleně středomořského z velké části jeho původního areálu. Dnes je tuleň středomořský na pokraji vyhynutí. Poslední žijící tuleni jsou roztroušeni po celé oblasti Středozemního moře.

Tuleň středomořský se řadí mezi ploutvonožce. Ploutvonožci se vyvinuli uprostřed třetihor ze suchozemských šelem. Je jich asi 30 druhů a jednotlivé druhy se od sebe moc neliší. Jsou přizpůsobeni životu ve vodě, končetiny mají proměněné v ploutve. Jsou to velmi dobří plavci, rychlost plavání dosahuje až 30 km/h. Potravou ploutvonožců je plankton, měkkýši a ryby. Všichni ploutvonožci mají silnou vrstvu tuku, která je chrání před chladem, a mají srst s velice hustou podsadou. Tuleň středomořský patří do řádu tuleňovitých, pro který je charakteristická chůze po předních končetinách. Tuleni se zdržují spíše u břehu, kde hloubka moře nedosahuje více než 70 m. Neumí se potápět do velkých hloubek a musí často odpočívat na souši. Jsou to plaší tvorové. Mláďata kojí mateřským mlékem a krev mají stejně teplou jako ostatní savci. Délka tuleně středomořského dosahuje u samice 230 cm a u samce až 320 cm. Váží až 320 kg. Zvíře je černohnědě zbarvené a na břiše má velkou světlou skvrnu. Někteří tuleni jsou jednotně hnědí. Ve stáří dochází k prošedivění srsti, která má pak stříbrný nádech. Jejich latinský název Monachus je odvozen od ruského slova mnich, což souvisí s jejich jednoduchým tmavým zbarvením.

Původně žil tuleň středomořský na ohromném území, od pobřeží Černého moře přes celé Středozemní moře až k pobřeží Madeiry a Kanárských ostrovů. Příbuzný poddruh žil v karibské oblasti, avšak tam je dnes vyhuben. Třetí příbuzný podruh v počtu několik set jedinců stále žije v okolí Havajských ostrovů. Tento druh tuleně je výborně přizpůsoben subtropickým podmínkám. Středomořští tuleni se v tomto století stali velmi vzácní díky nekontrolovatelnému odstřelu, kdy jejich stav klesl z několika desítek tisíc na pouhých několik set kusů, které žijí ve východním Středozemním moři, u západního pobřeží Afriky a na pobřeží Jadranu. Malé skupinky tuleňů se občas vyskytují i v západním středomoří např. v oblasti Sardinie, právě tady byl však tuleň středomořský přívalem turistů kriticky ohrožen. Od roku 2010 se několik jedinců usadilo v oblasti severního Jadranu u Puly, kde se s nimi potkávají i potápěči pod vodou.

Tuleň středomořský se potápí především na skalnatých pobřežích v okolí jeskyní, kam se často ukrývá. Žije převážně na starých známých březích, kde odpočívá a rodí mláďata. Z místa na místo se přesouvá velmi vzácně. A proč vlastně dochází k takovému úbytku tuleně středomořského? Vědci si tento fakt vysvětlují takto: Mále kolonie žijící u pobřeží jsou dnes velmi vyrušovány čluny a loděmi s turisty. Lodě pronikají čím dál hlouběji do nejodlehlejších zákoutí pobřeží a tak se zvířatům nedostává patřičného odpočinku a nemají ve svých útočištích prostor ani k potřebnému rozmnožování. Právě proto, že nemají klid na souši, ukrývají se do jeskyní.

Tuleň středomořský je výjimkou mezi tuleni, neboť se velmi dobře pohybuje po souši, na rozdíl od jiných tuleňů, kteří se po souši pohybují spíše nemotorně. Za to, že se po souši takto obratně pohybuje, vděčí širokým a mohutným drápům na předních končetinách, které normálně využívá k plavání. Po vylezení z vody se mohutnými drápy uchycuje na skalách. Drápy mu umožňují, na rozdíl od tuleně obecného, opustit moře i na skalnatém pobřeží. Hlavním nepřítelem tuleně středomořského je žralok, kterému však dokáže svým obratným pohybem ve vodě uniknout.

Tuleň středomořský má chrup jako šelma a je schopen kořist nejen uchopit ale i rozkousat. Potravu si rozporcuje na kusy určité velikosti, které pak v celku polyká, aniž by je dále rozkousal.

Důležité je, aby měl tuleň klid, především v letních měsících, protože se musí chladit a chránit před slunečním zářením a následným přehřátím. K tomuto cíli vyhledává stinná místa v skalních rozsedlinách nebo podmořských jeskyních a pohybuje se v tomto období jen velmi málo.

Tuleni se dožívají dvaceti let, někdy i více. Dorozumívají se rozličným chrochtáním a ostrým štěkáním.

Živí se rybami a dalšími mořskými tvory, které často skupinově loví.

Tuleni přivádí svá mláďata na svět na souši, kde se jich během rozmnožování shromažďují stovky. Každý samec se snaží zabrat si pro sebe co největší skupinu samic a ostatní samce zahání neohrabanými poskoky. Ve vodě se postupně páří se všemi svými samicemi. Tuleni středomořští dávají přednost nepřístupným a nerušeným místům, která slouží pouze k odpočinku a vrhu mláďat. Mláďata se rodí v září a v říjnu a matka o ně pečuje tři roky. Když dospějí do věku 4 let, jsou již pohlavně zralí. Tulení mláďata jsou roztomilá, avšak i tito skoro bezbranní tvorové jsou zabíjeni lidmi pro jejich kožešinu.

Tuleň středomořský (Monachus monachus) patří do nevelké skupiny mořských vodních savců – ploutvonožců. Jeho domovem bylo kdysi celé Středozemní moře a přilehlé oblasti. Rybáři však v tuleních viděli konkurenci, která jim snižuje úlovky a tak je začali hubit, často velmi nevybíravými metodami. To vedlo k vymizení tuleně středomořského z velké části jeho původního areálu. Dnes je tuleň středomořský na pokraji vyhynutí. Poslední žijící tuleni jsou roztroušeni po celé oblasti Středozemního moře.

Middelhavsmunkesæl (Monachus Monachus) er den næstmest sjældne sælart med under 600 nulevende individer. Som navnet antyder hører den til i Middelhavet. Det antages, at sælen kan leve i op til 45 år. Når hunsælen føder, gør hun det i huler, som kun kan nås ved at svømme under vand.

StubDie Mittelmeer-Mönchsrobbe (Monachus monachus) ist eine vom Aussterben bedrohte Robbenart aus der Familie der Hundsrobben. Mit geschätzten 350 bis 450 geschlechtsreifen Individuen[1] ist sie eines der seltensten Säugetiere Europas.

Hauptcharakteristikum ist die doppelte Schwanzflosse. In der Farbe sind diese Robben sehr variabel; sie liegt zwischen hellgrau und schwarzbraun. Mit einer Länge von 240 cm und einem Gewicht von 280 kg (Weibchen) ist die Mittelmeer-Mönchsrobbe deutlich größer als ein Seehund. Weibchen sind etwas kleiner als Männchen. Jungtiere werden mit etwa 80 cm und einem schwarzen Geburtsfell, welches oftmals einen weißen Fleck aufweist, zur Welt gebracht.[2]

Die einzige Robbenart des Mittelmeers ist durch Verfolgung extrem selten geworden. Die größten Populationen befinden sich an den griechischen und türkischen Küsten (Foça, Anamur und Alonnisos). Allein im griechischen Alonnisos Marine Park sollen zwei Drittel des Bestandes beheimatet sein.[3] Kleinere Restpopulationen leben an der afrikanischen Küste zwischen Marokko und der Westsahara (dort an der Südspitze der Halbinsel Ras Nouadhibou) und bei den Ilhas Desertas im Madeira-Archipel im Atlantik, aber auch in der Straße von Sizilien bei La Galite (Tunesien). Die Kolonie bei Madeira umfasst ca. 30 Tiere und der Bestand ist in den letzten Jahren im Anstieg begriffen.[4] Weiterhin finden sich kleine Populationen an der Küste Istriens, etwa in der Nähe der Stadt Pula.[5]

Die Mittelmeer-Mönchsrobbe ist ein tagaktiver Fischfresser, der in kleinen Kolonien von maximal zwanzig Tieren anzutreffen ist. Zum Gebären sucht sie typischerweise Höhlen auf, die nur unter Wasser erreichbar sind, wobei historische Beschreibungen zeigen, dass bis zum 18. Jahrhundert auch offene Strände genutzt wurden.[2]

Über das Fortpflanzungsverhalten der Mittelmeer-Mönchsrobbe ist nur sehr wenig bekannt. Wissenschaftler vermuten, dass die Art polygyn lebt. Obwohl Geburten über das ganze Jahr verteilt vorkommen, erreichen sie im Oktober und November einen Höhepunkt. Auch weil in dieser Zeit viele Höhlen durch Hochwasser oder Sturmfluten überschwemmt werden, ist die Sterblichkeit unter Jungtieren sehr hoch: so geht die IUCN davon aus, dass von den zwischen September und Januar geborenen Tieren lediglich 29 % überleben. Die Laktationszeit beträgt durchschnittlich 134 Tage.

Schon Aristoteles lieferte eine Beschreibung der Mönchsrobbe, die somit die erste beschriebene Robbe überhaupt ist. Seit Jahrhunderten sahen viele Fischer in dieser Robbe eine Konkurrenz. Dadurch und durch die starke Umweltverschmutzung der Lebensgebiete ist dieses Säugetier heute sehr stark vom Aussterben bedroht.

Funde von Knochen mit Schnittspuren in der Gorham-Höhle, Gibraltar belegen, dass bereits der Neandertaler zumindest gelegentlich Mönchrobben nutzte. Eine aktive Jagd mit Waffen auf erwachsene Robben ist bislang nicht nachweisbar. Dies belegt jedoch eine frühere Verbreitung der Mönchsrobbe auch entlang der iberischen Südküste.

Zum Schutz der Art wurden 1992 die Nationalparks um die Ilhas Desertas bei Madeira und die Nördlichen Sporaden in der Ägäis eingerichtet. Des Weiteren ist diese Art im CITES-Anhang I (totales Handelsverbot) gelistet.[6]

Eine Studie des italienischen Umweltministeriums von 2013 bestätigt das Vorhandensein von Mönchsrobben im Meeresschutzgebiet der Ägadischen Inseln.[7][8]

Die Mittelmeer-Mönchsrobbe (Monachus monachus) ist eine vom Aussterben bedrohte Robbenart aus der Familie der Hundsrobben. Mit geschätzten 350 bis 450 geschlechtsreifen Individuen ist sie eines der seltensten Säugetiere Europas.

Foka e Mesdheut (lat. Monachus monachus) është një lloj foke që i takon familjes Phocidae. Në vitin 2016, është llogaritur të ketë më pak se 700 individë të gjallë të këtij lloji, të vendosur në tre apo katër nënpopullata të zolura në Detin Mesdhe (posaçërisht në Detin Egje), arkipelagun e Maderias dhe në arkipelagun Ras Nouadhibou në verilindje të Oqeanit Atlantik.[1] Besohet të jetë lloji më i rallë i fokave në botë.

Foka e Mesdheut (lat. Monachus monachus) është një lloj foke që i takon familjes Phocidae. Në vitin 2016, është llogaritur të ketë më pak se 700 individë të gjallë të këtij lloji, të vendosur në tre apo katër nënpopullata të zolura në Detin Mesdhe (posaçërisht në Detin Egje), arkipelagun e Maderias dhe në arkipelagun Ras Nouadhibou në verilindje të Oqeanit Atlantik. Besohet të jetë lloji më i rallë i fokave në botë.

Monachus monachus ye a sola especie d'a familia Phocidae present en a Mar Mediterrania, y tamién se distribuye u distribuiba por a costa atlantica nordafricana dica Mauritania, Cabo Verde, as Islas Canarias y Madeira. Ha desapareixiu d'a mayor part d'as costas mediterranias y d'as Islas Canarias.

Se conoix fósil dende o Pleistoceno meyo de Vallonnet, y tamién se troba fósil en o Pleistoceno meyo d'as esplugas de Grimaldi y d'Altamira. Tamién s'ha trobau como fósil en as minas de Can Tintoré (Gavà, Barcelona) con edat neolitica inferior-meya (5070 u 4880 anyos BP).

En catalán se li diz metaforicament vell marí ("viello marín"), que curiosament recuerda a l'asociación d'un dios marín griego sustituito por Poseidón con esta especie de focido, tarcual veyemos en "A Odisea". En occitán existe a denominación de buòu marin[1] (buei marín). Dende las formas catalanas y occitanas tenemos adaptacions escritas como veyl marin en o peache de Uesca y como bitill marino en o peache de L'Ainsa en o sieglo XV.

Monachus monachus ye a sola especie d'a familia Phocidae present en a Mar Mediterrania, y tamién se distribuye u distribuiba por a costa atlantica nordafricana dica Mauritania, Cabo Verde, as Islas Canarias y Madeira. Ha desapareixiu d'a mayor part d'as costas mediterranias y d'as Islas Canarias.

Se conoix fósil dende o Pleistoceno meyo de Vallonnet, y tamién se troba fósil en o Pleistoceno meyo d'as esplugas de Grimaldi y d'Altamira. Tamién s'ha trobau como fósil en as minas de Can Tintoré (Gavà, Barcelona) con edat neolitica inferior-meya (5070 u 4880 anyos BP).

U vechju marinu (Monachus monachus) hè un mammiferu marinu di a famiglia di i Phocidae. Hè una spezia minacciata d'estinzione. À i ghjorni d'oghje, ùn esiste più cà circa 500 esemplari di vechju marinu in u mondu.

U vechju marinu fundieghja pocu, insin'à vinti metri solamente, chì ùn pò stà in apnea ch'è 5 o 6 minute à 10 metri, è 3 minute à circa 30 metri.

'Ss'ultimi anni, u vechju marinu hà cambiatu è adattatu e so abitudine, appostu chì stà piuttostu avà in e sapare è e grotte marine, per pruteghje si di a l'attività umane. Difatti, e nascite occorrenu in e grotte marine ma i ghjovani sò più esposti à u periculu di e cavallate di u mare.

E caratteristiche fisiche di u vechju marinu sò analoghe à quelle di l'altre Phocidae: u corpu hè allungatu, irregularmente cilindricu.

U vechju marinu hà una lunghezza da 80 à 280 cm è pò ancu ghjunghje sin'à 400 kilò di pesu; e femine sò appena più chjughe di i masci. Anu una piccula testa. U pilame di u vechju marinu hè brunu, essendu più chjaru annantu à u ventre. U vechju marinu campa sin'à 30 o 40 anni. U pelu hè cortu cortu, circa un mezu centimetru, ma hè adattatu à l'acqua di u mare Terraniu, più calda ch'è quella di l'oceanu. U pilame di i chjuchi hè più bianchicciu è ci hè in generale una tacca bianca versu u billicu.

L'areale di u vechju marinu comprendia in i tempi u Mare Terraniu sanu, u Mare Neru, e coste atlantiche di Spagna è di u Portugallu, u Maroccu, a Mauritania, Madera è e Canarie. Ma à i ghjorni d'oghje, hè guasi sparitu da e coste di u Mare Terraniu, per via di a crescenza di l'attività umane annantu à u litturale (pesca, turisimu, custruzzione) ma dinù di a destruzzione di fucile. U vechju marinu hè in periculu d'estinzione, chì ùn ni ferma più ch'è circa 500 individui, in parechji gruppi isulati in Grecia è in Turchia, è dinò in u nordu-punente di l'Africa (Maroccu, Mauritania è Madera).

U vechju marinu hè prutettu da:

U vechju marinu hè ancu chjamatu in Corsica: l'omu marinu, u boiu marinu o ancu u vitellu marinu. U vechju marinu era cumunu in Corsica mentre a prima mità di u seculu XX. Era arrighjunatu in u Capicorsu, annantu à a costa uccidentale, ma dinù in l'areale chì si stende in a parte a più suttana di a Corsica: da Prubià à Bonifaziu, sin'à Portuvechju. I vechji marini eranu prisenti in parechje sapare di l'attuale Riserva di Scandula. Friquentavanu e spiaghje di i circondi, è in particulare e spiaghje di Galeria. U vechju marinu era prisente in l'isulottu di Gargalu, ma dinù in in una sapara maiore di a Punta Palazzu. Hè in 'ssa sapara chì fù tombu un vechju marinu femina, da u principe Rainier III di Monacu, u 27 sittembre di u 1946 (Franceschi 1987). 'Ssu vechju marinu hè espostu avà in u Museu oceanograficu di Monacu. Bon'parechji vechji marini di Corsica sò stati tombi prima di piola, ma dopu funi tombi di fucile. À spessu, i vechji marini erani tombi da i pescadori, chì u cunsideravanu cum'è un cuncurrente per a pesca. È quessa, assuciata à una friquentazione più impurtante di e spiaghje è di l'isulotti da i turisti, incausò à pocu à pocu a sparizione di u vechju marinu di l'isula. Qualchì vechju marinu fù usservatu in u settanta o un pocu più dopu, ma l'usservzione sò schersi è cuncernanu individui isulati. Si pò mintuvà dinù parechje usservazione più ricente (U Scoddu, ferraghju 2010), in particulare vicinu à l'isula di U Cavallu. Si spera chì u vechju marinu puderà esse riintroduttu in Corsica, in i so lochi, in particulare in a Riserva di Scandula. Cù u tempu, e cunniscenze scentifiche anu dimustratu ch'ellu un animale ch'ùn fundieghja tantu - sin'à vinti metri - chì e so capacità per l'apnea sò debule.

U vechju marinu (Monachus monachus) hè un mammiferu marinu di a famiglia di i Phocidae. Hè una spezia minacciata d'estinzione. À i ghjorni d'oghje, ùn esiste più cà circa 500 esemplari di vechju marinu in u mondu.

Η μεσογειακή φώκια μοναχός (Monachus monachus), είναι το ένα από τα δύο εναπομείναντα είδη φώκιας μοναχού της οικογένειας των φωκιδών. Κάποτε ήταν εξαπλωμένη σε όλες τις ακτές της Μεσογείου, της Μαύρης Θάλασσας και του ανατολικού Ατλαντικού. Σήμερα, με αριθμό μικρότερο από 600 ζώα, συγκαταλέγεται στα σπανιότερα και πλέον απειλούμενα ζωικά είδη του πλανήτη και χαρακτηρίζεται ως κρισίμως κινδυνεύον με αφανισμό από την Διεθνή Ένωση Προστασίας της Φύσης. Ο μισός περίπου πληθυσμός, γύρω στα 250-300 άτομα, ζει στην Ελλάδα.

Στις ραψωδίες Δ' και Ο' της Οδύσσειας γίνεται αναφορά σε αυτήν στον πληθυντικό ως φῶκαι. Αργότερα ο Αριστοτέλης μελέτησε και περιέγραψε διεξοδικά την φώκη στο έργο του Τῶν περὶ τὰ ζῷα ἱστοριῶν.

Ο Γάλλος ζωολόγος Ζαν Ερμάν περιέγραψε πρώτος, στην σύγχρονη εποχή, την μεσογειακή φώκια από τον ολότυπο της συλλογής του. Ονόμασε το είδος Phoca monachus (φώκια μοναχός), πιθανόν λόγω κάποιας ομοιότητας που διέκρινε με τους καλόγερους και όχι σύμφωνα με παλαιότερες αντιλήψεις λόγω του μοναχικού χαρακτήρα του είδους: οι δίπλες που σχηματίζει στο δέρμα της στην περιοχή του λαιμού, ίσως θυμίζουν τις πτυχές από την κουκούλα και το ράσο των μοναχών. Ο Τζον Φλέμινγκ κράτησε το όνομα monachus αλλά το αναβάθμισε σε γένος με ομώνυμο ειδικό Monachus monachus.[1]

Το μήκος των ενήλικων ζώων κυμαίνεται μεταξύ 2-3 μέτρων, ενώ το βάρος τους φθάνει έως και τα 350 κιλά, με τα θηλυκά να είναι λίγο μικρότερα από τα αρσενικά. Το σώμα τους καλύπτεται από στιλπνό τρίχωμα, μήκους περίπου μισού εκατοστού. Το χρώμα τους ποικίλλει από ανοιχτό γκρί και μπεζ στα θηλυκά μέχρι σκούρο καφέ και μαύρο στα αρσενικά, πολλές φορές διάστικτο και με ανοιχτόχρωμα σημεία στον αυχένα, τον λαιμό και την κοιλιά. Στα αρσενικά είναι ιδιαίτερα εμφανής και ευδιάκριτη η λευκή κηλίδα στην κοιλιά.[2][3]

Οι μεσογειακές φώκιες ζουν μέχρι και 45 χρόνια,[4] αν και ο μέσος όρος είναι γύρω στα 20, ενώ η σεξουαλική ωριμότητα ξεκινά στον 5ο. Ζευγαρώνουν στο νερό και γεννούν κάθε 2 χρόνια -μετά από κύηση 10 μηνών και πάντα στην στεριά- συνήθως ένα μικρό, σπανιότερα δύο. Το νεογέννητο έχει μήκος περίπου 1 μέτρο, ζυγίζει γύρω στα 15 κιλά και είναι ήδη ικανό να κολυμπήσει. Το δέρμα του καλύπτεται από μακρύ σκούρο τρίχωμα μήκους έως και 1,5 εκατοστά. Το τρίχωμα αυτό αντικαθίσταται μέσα σε δύο μήνες από το κοντό τρίχωμα των ενήλικων ζώων. Στην κοιλιά υπάρχει μία μεγάλη λευκή κηλίδα σαν μπάλωμα, της οποίας το σχήμα διαφέρει χαρακτηριστικά σε κάθε φώκια αλλά και μεταξύ των δύο φύλων.[4] Η γαλουχία διαρκεί περίπου τρεις με τέσσερις μήνες και μετά αρχίζει σιγά-σιγά να κυνηγά και να βρίσκει την τροφή του. Την περίοδο αυτήν και σε αντίθεση με άλλα είδη φώκιας, η μητέρα αφήνει το μικρό της μόνο του για κάποιες ώρες προς αναζήτηση τροφής.

Έχει παρατηρηθεί πως είναι πολυγυνικές, δηλαδή ένα ενήλικο αρσενικό διατηρεί ένα χαρέμι και ζευγαρώνει με περισσότερα από ένα θηλυκά. Η γέννα λαμβάνει χώρα σε απομονωμένη σπηλιά με έξοδο προς την παραλία, αν και από παλιές περιγραφές έως και τον 18ο αιώνα φαίνεται πως γεννούσαν στις ανοιχτές αμμουδιές.[5]

Στην Ελλάδα η αναπαραγωγική περίοδος ξεκινάει από τον Αύγουστο και ολοκληρώνεται τον Δεκέμβριο, με πολύ σπάνιες πρώιμες και όψιμες γεννήσεις[6]. Η κορύφωση της αναπαραγωγικής περιόδου καταγράφεται μεταξύ Σεπτεμβρίου και Οκτωβρίου. Την ίδια περίοδο και λόγω της επιδείνωσης του καιρού (φθινοπωρινές καιρικές συνθήκες και θαλασσοταραχές) υπάρχει κίνδυνος για τα νεογνά να παρασυρθούν από τη θάλασσα, να χάσουν τη μητέρα τους και να πνιγούν, καθώς μέχρι και τον τέταρτο μήνα της ζωής τους θηλάζουν αποκλειστικά και δεν μπορούν να τραφούν μόνα τους, ούτε είναι τόσο ικανά στη θάλασσα.

Το σώμα της έχει σχήμα ατρακτοειδές που διευκολύνει την κίνησή της μέσα στο νερό, ενώ τα άκρα της έχουν σχήμα πτερυγίων. Στο κεφάλι της έχει μικρές ακουστικές οπές αντί για εξωτερικά αυτιά και μακριά μουστάκια που χρησιμεύουν ως αισθητήρια όργανα.

Το θαλάσσιο περιβάλλον της Μεσογείου, όπου ζει μεγάλη ποικιλία ειδών αλλά σε μικρούς σχετικά αριθμούς, φαίνεται να ευνοεί την διατροφική προσαρμογή της φώκιας, η οποία δε δείχνει κάποια προτίμηση σε συγκεκριμένα είδη. Αντιθέτως τρέφεται με μια ποικιλία από οστεϊχθύς, όπως σαργούς, συναγρίδες, γόπες, μπαρμπούνια και κεφαλόποδων όπως χταπόδια, σουπιές και καλαμάρια, αλλά και καρκινοειδή όπως καβούρια.[1][2] Το κυριότερο θήραμα των μεσογειακών φωκών αποτελούν τα χταπόδια και συγκεριμένα το Octopus vulgaris[7]

Σε σχέση με άλλα είδη φωκών, η μεσογειακή φώκια μπορεί να θεωρηθεί «παράκτιο είδος», καθώς φαίνεται ότι κινείται και κυνηγά την τροφή της κοντά στις ακτές και κυρίως ριχότερα από την ισοβαθή των 200 μέτρων. Μέγιστος χρόνος κατάδυσης είναι 15-20 λεπτά. Οι περισσότερες καταδύσεις όμως γίνονται σε βάθος 30-40 μέτρα και διαρκούν γύρω στα 5-10 λεπτά. Έχουν πάντως την ικανότητα να καλύψουν σημαντικές αποστάσεις μέσα σε λίγες εβδομάδες ή λίγους μήνες.

Η κατανομή της στον ελλαδικό χώρο είναι πολύ μεγάλη, αν και περιορισμένη αριθμητικά. Δείχνει σαφή προτίμηση σε απομονωμένες, βραχώδεις και δυσπρόσιτες νησίδες ή παράκτιες περιοχές.

Ιστορικές πηγές αναφέρουν ότι οι Μεσογειακές φώκιες συνήθιζαν να χρησιμοποιούν ανοιχτές παραλίες για να ξεκουράζονται και να γεννάνε. Σήμερα όμως, λόγω τις ανθρώπινης όχλησης και τις καταστροφής του φυσικού της χώρου έχει αποτραβηχτεί κυρίως σε απρόσιτες παράκτιες θαλασσινές σπηλιές. Οι σπηλιές αυτές, που μπορεί να έχουν μία ή και περισσότερες εισόδους πάνω ή και κάτω από την επιφάνεια του νερού έχουν ως κοινό χαρακτηριστικό ότι καταλήγουν σε παραλία (χερσαίο, σχετικά επίπεδο χώρο με άμμο, βότσαλα, κροκάλες είτε επίπεδο βράχο).

Κάποτε η μεσογειακή φώκια ήταν εξαπλωμένη από τις ακτές της Μεσογείου και της Μαύρης Θάλασσας έως την βορειοδυτική ακτή της Αφρικής στον Ατλαντικό, μέχρι και τις Αζόρες.[8]

Η δραματική μείωση του πληθυσμού οφείλεται κυρίως στον ανθρώπινο παράγοντα, από όλες του τις πλευρές. Από την αρχαιότητα κυνηγούνταν για εμπορικούς σκοπούς λόγω του δέρματος και του λίπους της. Οι Ρωμαίοι τις χρησιμοποιούσαν και για ψυχαγωγικούς λόγους στις ρωμαϊκές αρένες.[9] Στο Αιγαίο παλιότερα έφτιαχναν από το δέρμα τους σανδάλια και ζώνες και το λίπος το χρησιμοποιούσαν στην παρασκευή κάποιου ματζουνιού.[2] Επίσης καταδιώκεται ως βλαβερό ζώο από τους ψαράδες λόγω της ζημιάς που μπορεί να προκαλέσει στα δίχτυα τους όταν μπλεχτεί σ' αυτά. Η ηθελημένη θανάτωσή τους από τον άνθρωπο στις ελληνικές θάλασσες, παραμένει η πρωταρχική αιτία θανάτου για τα ενήλικα άτομα του είδους.

Ο θάνατος φωκών από την παγίδευση τους σε αλιευτικά εργαλεία είναι πολύ συχνό φαινόμενο στις περισσότερες περιοχές εξάπλωσης του είδους. Τα ζώα παγιδεύονται και πνίγονται κυρίως σε στατικά δίχτυα που χρησιμοποιούνται ευρέως από την παράκτια αλιεία. Στοιχεία έρευνας στην Ελλάδα αποδεικνύουν ότι το πρόβλημα είναι ιδιαίτερα έντονο στα ανήλικα και άρα περισσότερο άπειρα άτομα. Υπεραλίευση και παράνομη αλιεία έχουν οδηγήσει σε σημαντική μείωση τα ιχθυαποθέματα ώστε οι φώκιες να δυσκολεύονται να εξασφαλίσουν αρκετή τροφή από το φυσικό τους στοιχείο.[10] Παράλληλα ραγδαία αύξηση του ανθρώπινου πληθυσμού και η αστικοποίηση μαζί με την άνοδο του παραθαλάσσιου και θαλάσσιου τουρισμού υποβάθμισαν τον βιότοπο της μεσογειακής φώκιας και την εκδίωξαν από τις ανοιχτές παραλίες.

Σήμερα έχει κηρυχθεί είδος κρισίμως κινδυνεύον με αφανισμό. Ο συνολικός πληθυσμός υπολογίζεται σε λιγότερα από 600 ζώα διεσπαρμένα σε τέσσερις απομονωμένους θύλακες στα νησιά Μαδέρα (25-35 άτομα), στο Λευκό Ακρωτήριο της Μαυριτανίας (130 άτομα) στον Ατλαντικό, στις Μεσογειακές ακτές Μαρόκου και Αλγερίας και στην Ανατολική Μεσόγειο (Αιγαίο και Ιόνιο Πέλαγος). Μόνο δύο από τους θύλακες μπορούν να θεωρηθούν βιώσιμοι: ο ένας στο Αιγαίο Πέλαγος που αριθμεί περίπου 300 φώκιες στην Ελλάδα (στις Β. Σποράδες, την Κίμωλο και την Κάρπαθο)και 100 στην Τουρκία. Ο άλλος στο Λευκό Ακρωτήριο, στην Μαυριτανία με 130 φώκιες. Οι δύο αυτές θέσεις βρίσκονται στα δύο ακραία σημεία της περιοχής εξάπλωσης της φώκιας και είναι αδύνατη η όποια επικοινωνία και ανταλλαγή των πληθυσμών μεταξύ τους και ο εμπλουτισμός του γενετικού τους υλικού. Όλοι οι υπόλοιποι πληθυσμοί αριθμούν λιγότερα από 50 άτομα. Στις περισσότερες περιπτώσεις πρόκειται για σκόρπιες ομάδες μέχρι 5 ατόμων.[8]

Τέτοιοι μικροί πληθυσμοί υπάρχουν στην Μαδέρα (περίπου 30 άτομα)[4] και στα νησιά Ντεζέρτας στον Ατλαντικό, στην Κιλικία, στο Ιόνιο Πέλαγος. Στη δυτική Μεσόγειο υπάρχουν μόνο μικρές ομάδες στις αφρικανικές ακτές (Μαρόκο και Αλγερία) και πολύ σπάνιες θεάσεις στις Βαλεαρίδες Νήσους[11], στη Σαρδηνία[12] και στο Γιβραλτάρ.

Στο Λευκό Ακρωτήριο (Ρας Νουαντίμπου) ζει η μεγαλύτερη ομάδα μεσογειακής φώκιας, και η μοναδική που έχει ακόμη μορφή αποικίας. Το καλοκαίρι του 1997 τα δύο τρίτα του πληθυσμού εξολοθρεύτηκαν μέσα σε δύο μήνες θέτοντας σε κίνδυνο τη δυνατότητα επιβίωσης του είδους. Η αιτία που προκάλεσε τον μαζικό θάνατο των ζώων και μείωσε τον πληθυσμό της αποικίας από 317 σε 130 άτομα φαίνεται είναι το φαινόμενο της άνθισης φυτοπλαγκτού και συγκεκριμένα η έκθεση των ζώων σε κάποια φυτοπλαγκτονική τοξίνη.[8] Η αποικία υπολογίζεται πως αριθμεί σήμερα περί τα 150 άτομα και παραμένει η μεγαλύτερη ομάδα μεσογειακής φώκιας, όμως να τέτοιο φαινόμενο θα μπορούσε να αφανίσει όλον τον εναπομείναντα πληθυσμό.

Σημαντικό βήμα για την προστασία της μεσογειακής φώκιας και των βιοτόπων της αποτέλεσε η ανακήρυξη της περιοχής των Βορείων Σποράδων σε προστατευόμενη και η ίδρυση του Εθνικού Θαλάσσιου Πάρκου Αλοννήσου Βορείων Σποράδων (ΕΘΠΑΒΣ)[13]. Καθοριστική υπήρξε η συμβολή της μη κερδοσκοπικής, μη κυβερνητικής οργάνωσης ΜOm /Εταιρία για τη Μελέτη και Προστασία της Μεσογειακής Φώκιας στην οργάνωση και λειτουργία δραστηριοτήτων όπως η ενημέρωση του κοινού και η παρακολούθηση της κατάστασης του πληθυσμού της Μεσογειακής φώκιας, σε συνεργασία με τις αρμόδιες αρχές. Σύμφωνα με τα στοιχεία του οργανισμού, τουλάχιστον 55 διαφορετικά ενήλικα ζώα έχουν αναγνωριστεί να συχνάζουν στην περιοχή του θαλάσσιου πάρκου, ενώ υπολογίζεται γεννιούνται άλλα οχτώ τον χρόνο.[14]

Μέρος της δράσης της MOm είναι η ευαισθητοποίηση και ενημέρωση των ντόπιων κατοίκων και ψαράδων όπως και η διάσωση και περίθαλψη άρρωστων, τραυματισμένων και ορφανών ζώων. Γι αυτόν τον λόγο δημιούργησε το Κέντρο Περίθαλψης Μεσογειακής Φώκιας στην Αλόννησο, το οποίο είναι το μοναδικό στη Μεσόγειο και λειτουργεί σε συνδυασμό με το δίκτυο διάσωσης και συλλογής πληροφοριών της MOm[15]. Εκεί φιλοξενούνται μόνο τα νεογέννητα, κατά κύριο λόγο, ορφανά φωκάκια που χωρίστηκαν από τη μητέρα τους, συνήθως λόγω καιρικών συνθηκών. Η περίθαλψη των μεγαλύτερων ζώων γίνεται επί τόπου. Το δε Δίκτυο Διάσωσης και Συλλογής Πληροφοριών (RINT) βασίζεται σε μέλη από όλη την Ελλάδα, κατά πλειοψηφία μη ειδικούς, που αποστέλλουν τακτικά πληροφορίες και ενημέρωση από τις παράκτιες και νησιωτικές περιοχές[16].

Η Ελλάδα ετοιμάζεται να κηρύξει μια δεύτερη περιοχή στο Αιγαίο ως προστατευόμενο θαλάσσιο πάρκο με έναν από τους κύριους στόχους της πράξης αυτής την «προστασία και διατήρηση του σημαντικού πληθυσμού της απειλούμενης με εξαφάνιση Μεσογειακής φώκιας Monachus monachus»[17]. Θα ονομάζεται Περιφερειακό Θαλάσσιο Πάρκο Βόρειας Καρπάθου, νήσου Σαρίας και των Αστακιδονησίων (Π.Θ.Π.Β.Κ.Σ.Α) και θα περιλαμβάνει τις ήδη υπάρχουσες Ειδικές Ζώνες Διατήρησης (ΕΖΔ) Καρπάθου-Σαρίας και Αστακιδονησίων του Δικτύου Natura 2000 [18][19].

Το άλλο θαλάσσιο πάρκο της χώρας είναι το Εθνικό Θαλάσσιο Πάρκο Ζακύνθου στο Ιόνιο Πέλαγος. Με βάση τα στοιχεία του WWF που πραγματοποίησε συστηματική καταγραφή πληθυσμού της φώκιας το 1991, βρίσκουνε καταφύγιο στην περιοχή 14-18 άτομα. Πρόκειται για το μεγαλύτερο γνωστό πληθυσμό στο Ιόνιο[20].

Μαζί με τις δύο περιοχές στην Τουρκία, στη Φώκαια της Σμύρνης και στην Επαρχία της Μερσίνης, είναι τα μοναδικά προστατευόμενα καταφύγια της φώκιας στη μεσόγειο. Η ΜΚΟ SAD-DAFAG που δραστηριοποιείται στην περιοχή υπολογίζει τον αριθμό των ζώων σε περίπου 100[21].

Στον Ατλαντικό υπάρχει η προστατευόμενη περιοχή στα νησιά Ντεζέρτας της Μαδέρας, όπου φαίνονται ενθαρρυντικά σημάδια ανάκαμψης μετά από έντονες προσπάθειες προστασίας εκ μέρους της πορτογαλικής διαχειριστικής αρχής, και ο αριθμός έχει ανέβει στις 25-35 φώκιες. Νοτιότερα, στο Λευκό Ακρωτήρι το Μαροκινό Ναυτικό περιπολεί τη ζώνη όπου απαγορεύεται η αλιεία με σκοπό να μειωθεί η βασική αιτία θανάτου της φώκιας, τα δίχτυα των ψαράδων, και να διασωθεί η μεγαλύτερη ομάδα μεσογειακής φώκιας που αριθμεί 130 άτομα[22].

Αναφορές στη φώκια γίνονται στην «Οδύσσεια», στις Ραψωδίες Δ' και Ο' όπως αναφέρθηκε παραπάνω, αλλά και σε έργα του Αριστοφάνη. Σύγχρονα κείμενα όπου γίνονται αναφορές στη μεσογειακή φώκια είναι το Μοιρολόγι της Φώκιας του Αλέξανδρου Παπαδιαμάντη, το Άξιον Εστί του Οδυσσέα Ελύτη και το Το Μόνον της Ζωής του Ταξείδιον του Γεωργίου Βιζυηνού.

Η μεσογειακή φώκια μοναχός (Monachus monachus), είναι το ένα από τα δύο εναπομείναντα είδη φώκιας μοναχού της οικογένειας των φωκιδών. Κάποτε ήταν εξαπλωμένη σε όλες τις ακτές της Μεσογείου, της Μαύρης Θάλασσας και του ανατολικού Ατλαντικού. Σήμερα, με αριθμό μικρότερο από 600 ζώα, συγκαταλέγεται στα σπανιότερα και πλέον απειλούμενα ζωικά είδη του πλανήτη και χαρακτηρίζεται ως κρισίμως κινδυνεύον με αφανισμό από την Διεθνή Ένωση Προστασίας της Φύσης. Ο μισός περίπου πληθυσμός, γύρω στα 250-300 άτομα, ζει στην Ελλάδα.

Средоземна фока-мечка (Monachus monachus)

Двата вида Monachus monachus се загрозени. Покрупниот вид, средоземната фока-мечка, се наоѓа на списокот на најзагрозени видови. Крзното може да има од темнокафеава до бледокафеава боја. Женките се покрупни од мажјаците, а младенчињата се раѓаат со црно крзно, што е голема реткост меѓу фоките. Овој вид фоки порано биле доста распространети, но, поради повеќевековното претерано ловење, нивниот вкупен број се намалил на само неколку стотици. Тие главно живеат во Средоземјето, но најголема е колонијата на атлантскиот брег на Мароко. Најблиска роднина на оваа фока е ретката хавајска фока-мечка.

Средоземна фока-мечка (Monachus monachus)

Двата вида Monachus monachus се загрозени. Покрупниот вид, средоземната фока-мечка, се наоѓа на списокот на најзагрозени видови. Крзното може да има од темнокафеава до бледокафеава боја. Женките се покрупни од мажјаците, а младенчињата се раѓаат со црно крзно, што е голема реткост меѓу фоките. Овој вид фоки порано биле доста распространети, но, поради повеќевековното претерано ловење, нивниот вкупен број се намалил на само неколку стотици. Тие главно живеат во Средоземјето, но најголема е колонијата на атлантскиот брег на Мароко. Најблиска роднина на оваа фока е ретката хавајска фока-мечка.

Su bòe marìnu (monachus monachus) est unu mammìferu de sa famìlia Phocidae. Est un'ispètzie in perìculu de si estìnghere, tantu chi oje in dìe non bi nd'at chi unos 500 in tottu su mundu.

S'areale de su bòe marinu cumprendìat tottu su Mare de Mesu, su Mare Nigheddu, sas costèras atlanticas de Ispagna e Portogallu, Maroccu, Mauritania, Madera e Canarias. Oje chi est oje, peròe, sich'est belle ispàrtu dae su Mare de Mesu, pro more de s'attividade umana in costa (pìsca e càtza, turismu, palattos e gòi sichinde). Non bi nd'abbarrat chi 500 esemplares in grùstios ispèrdios in Grèghia e Turchia, e fintzas in su nord-ovest de s'Africa (Maroccu, Mauritania e Madera). In Sardinna fortzis bi nd'at galu calicunu, in su trettu tzentru-orientale de s'Ozzastra.

The Mediterranean monk seal (Monachus monachus) is a monk seal belonging to the family Phocidae. As of 2015, it is estimated that fewer than 700 individuals survive in three or four isolated subpopulations in the Mediterranean, (especially) in the Aegean Sea, the archipelago of Madeira and the Cabo Blanco area in the northeastern Atlantic Ocean.[3] It is believed to be the world's rarest pinniped species.[1] This is the only species in the genus Monachus.

This species of seal grows from approximately 80 centimetres (2.6 ft) long at birth up to an average of 2.4 metres (7.9 ft) as adults, females slightly shorter than males.[4] Males weigh an average of 320 kilograms (710 lb) and females weigh 300 kilograms (660 lb), with overall weight ranging from 240–400 kilograms (530–880 lb).[1][5][6][7] They are thought to live up to 45 years old;[5] the average life span is thought to be 20 to 25 years old and reproductive maturity is reached at around age four.

The monk seals' pups are about 1 metre (3.3 ft) long and weigh around 15–18 kilograms (33–40 lb), their skin being covered by 1–1.5 centimeter-long, dark brown to black hair. On their bellies, there is a white stripe, which differs in color and shape between the two sexes. In females the stripe is usually rectangular in shape whereas in males it is usually butterfly shaped.[8] This hair is replaced after six to eight weeks by the usual short hair adults carry.[5] Adults will continue to molt annually, causing their color vibrancy to change throughout the year.[9]

Pregnant Mediterranean monk seals typically use inaccessible undersea caves while giving birth, though historical descriptions show they used open beaches until the 18th century. There are eight pairs of teeth in both jaws.

Believed to have the shortest hair of any pinniped, the Mediterranean monk seal fur is black (males) or brown to dark grey (females), with a paler belly, which is close to white in males. The snout is short broad and flat, with very pronounced, long nostrils that face upward, unlike their Hawaiian relative, which tend to have more forward nostrils. The flippers are relatively short, with small slender claws. Monk seals have two pairs of retractable abdominal teats, unlike most other pinnipeds.

Very little is known of this seal's reproduction. As of 2020, it is thought that there are roughly 500 pairs of monk seals remaining in the world.[10] Scientists have suggested that they are polygynous, with males being very territorial where they mate with females. Although there is no breeding season since births take place year-round, there is a peak in September, October, and November. Although mating will take place in the water, females will give birth and care for the pups on beaches or underwater caves. The use of underwater caves may have begun in order to make predatory actions almost impossible as these caves are difficult to access. Because they will stay with the pups to nurse and protect, they use their stored fat reserves to nurse.[4] Data analysis indicates that only 29% of pups born between September and January survive. One cause of this low survival rate is the timing of high surf around the areas of breeding, creating a threat to young pups. As well, if a female determines that her environment is not a safe one, she can initiate an abortion, indirectly lowering the population.[10] Because of smaller populations there is an increase in genetic events such as inbreeding and lack of genetic variation. During other months of the year, pups have an estimated survival rate of 71%.[11]

In 2008, lactation was reported in an open beach, the first such record since 1945, which could suggest the seal could begin feeling increasingly safe to return to open beaches for breeding purposes in Cabo Blanco.[12]

Pups make first contact with the water two weeks after their birth and are weaned at around 18 weeks of age; females caring for pups will go off to feed for an average of nine hours.[1] Most female individuals are believed to reach maturity at four years of age unto which they will begin to breed.[4] Males begin to breed at age six.[9] The gestation period lasts close to a year. However, it is believed to be common among monk seals of the Cabo Blanco colony to have a gestation period lasting slightly longer than a year.

Mediterranean monk seals are diurnal and feed on a variety of fish and mollusks, primarily octopus, squid, and eels, up to 3 kg per day. Although they commonly feed in shallow coastal waters, they are also known to forage at depths up to 250 meters, with an average depth varying between specimens.[1] Monk seals prefer hunting in wide-open spaces, enabling them to use their speed more effectively. They are successful bottom-feeding hunters; some have even been observed lifting slabs of rock in search of prey.

The habitat of this pinniped has changed over the years. In ancient times, and up until the 20th century, Mediterranean monk seals had been known to congregate, give birth, and seek refuge on open beaches. In more recent times, they have left their former habitat and now only use sea caves for these activities. Often these caves are inaccessible to humans. Frequently their caves have underwater entries and many caves are positioned along remote or rugged coastlines.

Scientists have confirmed this is a recent adaptation, most likely due to the rapid increase in human population, tourism, and industry, which have caused increased disturbance by humans and the destruction of the species' natural habitat. Because of these seals' shy nature and sensitivity to human disturbance, they have slowly adapted to try to avoid contact with humans completely within the last century, and, perhaps, even earlier. The coastal caves are, however, dangerous for newborns, and are causes of major mortality among pups when sea storms hit the caves.

The mediterranean monk seal can be found in Western Sahara, Mauritania, Cyprus, Turkey, Greece, and Croatia.[1] It may be extinct in Tunisia, Libya, Italy, Spain and Albania.[1] Its status in Algeria and Morocco is unknown.[1]

This earless seal's former range extended throughout the Northwest Atlantic Africa, Mediterranean and Black Sea coastlines, including all offshore islands of the Mediterranean, and into the Atlantic and its islands: Canary, Madeira, Desertas, Porto Santo, as far west as the Azores. Vagrants could be found as far south as Gambia and the Cape Verde islands, and as far north as Atlantic France.[1]

Several causes provoked a dramatic population decrease over time: on one hand, commercial hunting (especially during the Roman Empire and Middle Ages) and, during the 20th century, eradication by fishermen, who used to consider it a pest due to the damage the seal causes to fishing nets when it preys on fish caught in them; and, on the other hand, coastal urbanization and pollution.[1]

Some seals have survived in the Sea of Marmara,[13] but the last report of a seal in the Black Sea dates to 1997.[1] Monk seals were present at Snake Island until the 1950s, and several locations such as the Danube Plavni Nature Reserve and Doğankent were the last known hauling-out sites post-1990.[14]

Nowadays, its entire population is estimated to be less than 700 individuals widely scattered, which qualifies this species as endangered. Its current very sparse population is one more serious threat to the species, as it only has two key sites that can be deemed viable. One is the Aegean Sea (250–300 animals in Greece, with the largest concentration of animals in Gyaros island,[3] and some 100 in Turkey); the other important subpopulation is in the Atlantic Ocean, in the Western Saharan portion of Cabo Blanco (around 270 individuals which may support the small, but growing, nucleus in the Desertas Islands – approximately 30-40 individuals[15]). There may be some individuals using coastal areas among other parts of Western Sahara, such as in Cintra Bay.[16]

These two key sites are virtually in the extreme opposites of the species' distribution range, which makes natural population interchange between them impossible. All the other remaining subpopulations are composed of less than 50 mature individuals, many of them being only loose groups of extremely reduced size – often less than five individuals.[1]

Other remaining populations are in southwestern Turkey and the Ionian Sea (both in the eastern Mediterranean). The species status is virtually moribund in the western Mediterranean, which still holds tiny Moroccan and Algerian populations, associated with rare sightings of vagrants in the Balearic Islands,[17] Sardinia, and other western Mediterranean locations, including Gibraltar.

In Sardinia the Mediterranean monk seal was last sighted in May 2007 and April 2010. The increase of sightings in Sardinia suggests that the seal occasionally inhabits the Central Eastern Sardinian coasts, preserved since 1998 by the National Park of Golfo of Orosei.[18][19][20]

Colonies on the Pelagie Islands (Linosa and Lampedusa) were destroyed by fishermen, which likely resulted in local extinction.[21]

Cabo Blanco, in the Atlantic Ocean, is the largest surviving single population of the species, and the only remaining site that still seems to preserve a colony structure.[1] In the summer of 1997, more than 200 animals[1] or two-thirds of its seal population were wiped out within two months, extremely compromising the species' viable population. While opinions on the precise causes of this epidemic remain divided between a morbillivirus or, more likely, a toxic algae bloom,[1] the mass die-off emphasized the precarious status of a species already regarded as critically endangered throughout its range.

Numbers in this all-important location started a slow-paced recovery ever since. A small but incipient (up to 20 animals by 2009) sub-population in the area had started using open beaches. In 2009, for the first time in centuries, a female delivered her pup on the beach (open beaches is the optimal habitat for the survival of pups, but had been abandoned due to human disturbance and persecution in past centuries).[22]

Only by 2016 the colony had recovered to its previous population (about 300 animals). This was made possible by a recovery plan financed by Spain.[15] Also in 2016, a new record of births was set for the colony (83 pups).[15]

However, the threat of a similar incident, which could severely reduce or wipe out the entire population, remains.[23]

In June 2009, there was a report of a sighting off the island of Giglio, in Italy.[24] On 7 January 2010, fishermen spotted an injured Mediterranean monk seal off the coasts of Tel Aviv, Israel. When zoo veterinarians arrived to help the seal, it had slipped back into the waters. Members of the Israel Marine Mammal Research and Assistance Center arrived at the scene and tried to locate the injured mammal, but with no success. This was the first sighting of the species in the region since Lebanese authorities claimed to have found a population of 10–20 other seals on their coasts 70 years earlier.[25] In addition, the seal was also sighted a couple of weeks later in the northern kibbutz of Rosh Hanikra.[26]

In April 2010, there was a report of a sighting off the island of Marettimo, in the Egadi Islands off the coast of Italy, in Trapani Province.[27] In November 2010, a Mediterranean monk seal, supposedly aged between 10 and 20, had been spotted in Bodrum, Turkey.[28] On 31 December 2010, the BBC Earth news[29] reported that the MOM Hellenic Society[30] had located a new colony of seals on a remote beach in the Aegean Sea. The exact location was not communicated so as to keep the site protected. The society was appealing to the Greek government to integrate the part of the island on which the seals live into a marine protected area.

On 8 March 2011, the BBC Earth news[31] reported that a pup seal had been spotted on 7 February while monitoring a seal colony on an island in the southwestern Aegean Sea. Soon after, it showed signs of weakness and it was taken to a rehabilitation centre to try to save it. The aim is to release it back into the wild as soon as it is strong enough. In April 2011, a monk seal was spotted near the Egyptian coast after long absence of the species from the nation.[32]

On 24 June 2011, the Blue World Institute of Croatia[33] filmed an adult female underwater in the northern Adriatic, off the island of Cres and a specimen of unverified sex on 29 June 2012.[34] On 2 May 2013 a specimen was seen on the southernmost point of Istrian peninsula near the town of Pula.[35] On 9 September 2013, in Pula a male specimen swam to a busy beach and entertained numerous tourists for five minutes before swimming back to the open sea.[36] In summer 2014 sightings in Pula have occurred almost daily and monk seal stayed multiple times on crowded city beaches, sleeping calm for hours just few meters away from humans.[37][38] To prevent accidents and preserve monk seal, local city council acquired special educational boards and installed on city beaches.[39] Despite clear instructions, an incident occurred with a tourist harassing a seal. The whole event was filmed.[40] Less than a month later on 25 August 2014 this female monk seal was found dead in the Mrtvi Puć bay near Šišan, Croatia. Experts said it was natural death caused by her old age.[41]

In 2012, a Mediterranean monk seal, was spotted in Gibraltar on the jetty of the private boat owners club at Coaling Island.[42]

In the week of 22–28 April 2013, what is believed to have been a monk seal was viewed in Tyre, southern Lebanon; photographs have been reported among many local media.[43] A study by the Italian Ministry of the Environment in 2013 confirmed the presence of monk seals in marine protected area in the Egadi Islands.[44] In September and October 2013, there were a number of sightings of an adult pair in waters around RAF Akrotiri in British Sovereign Base waters in Cyprus.

In November 2014, an adult monk seal was reportedly seen inside the port of Limassol, Cyprus. A female monk seal, called Argyro by the locals, was repeatedly seen on beaches of Samos island in 2014 and 2015,[45] and two were reported in April 2016.[46] On 2017 Argyro Shot and Killed.[47]

On 7 April 2015, a large floating "fish" was reported near Raouche, Beirut in Lebanon, and collected by a local fisherman. This turned out to be the body of a female monk seal known to have been resident there for some time. Further investigations revealed that she was pregnant with a pup.[48]

On 13 August 2015, ten monk seals were spotted in Governor's Beach, Limassol, Cyprus.[49]

On 6 January 2016, a monk seal climbed aboard a parked boat in Kuşadası.[50]

On 10 April 2016, a monk seal was spotted and photographed by a group of foreign exchange students and local bio-engineers in a creek in Manavgat District in Turkey's southern Antalya Province. According to the scientists involved in local projects to protect the animals, this was the first ever documented sighting of a monk seal swimming in a river. Possible reasons for the animal's appearance included better opportunities for hunting, as well as higher salinity levels due to lower water levels.[51]

On 26 April 2016, two monk seals were spotted at the municipal baths area of Paphos, Cyprus.[46]

On 18 October 2016, a monk seal was captured on video around Gulf of Kuşadası.[52]

On 3 November 2016, a monk seal was spotted at the coast of Gialousa in Cyprus.[53]

On 13 June 2017, a specimen was spotted and photographed by a group of fishermen off the coasts of Tricase in the south of Italy.[54]

In early 2018 a mother and her pup were spotted around Paphos Harbour in Cyprus.[55]

In November 2018, a young monk seal was spotted at the coast of Karavostasi in Cyprus, only to be found dead at the same area a few days later.[56]

On 15 March 2019, a monk seal was spotted and photographed by a group of citizens at a marina in Kuşadası.[57]

On 20 July 2019, a monk seal was spotted in Protaras bay area in Cyprus.[58]

On 27 January 2020, a young monk seal was recovered dead from Torre San Gennaro in Apulia.[59]

On 15 December 2020, a monk seal was spotted and videotaped while seated on a sunlounger in Samos Island, Greece.[60]

On 24 July 2021, a previously rescued and rehabilitated monk seal nicknamed "Kostis" was found dead in the waters of the Cycladic islands. MOm, the Hellenic Society for the Study and Protection of the Monk Seal reported that the seal had been executed at close range with a spear gun. Additionally, MOm pledged a €18,000 bounty for any evidence that “will lead to the arrest of the person(s) responsible for the killing of the seal, known as Kostis.”[61]

On 24 April 2023, a large monk seal was spotted at Korakonisi, Zakynthos in Greece. It stayed on the surface for around a minute observing onlookers and then dived and was not seen again on that day. [62]

On 12 May 2023, a healthy adult female monk seal was observed and photographed resting for at least a few hours on the beach in Jaffa near Tel Aviv, Israel.[63] Israel’s Nature and Park Authority has been monitoring since then this seal dubbed "Yulia", estimated at twenty years of age, spotted by eastern Mediterranean researchers in recent years in Turkey and Lebanon, where she is known as "Tugra". International consultation assessed that she is in normal molt to shed her winter coat, mostly relaxing on the section of beach that has been fenced off for her, and occasionally going into the water.[64][65][66]

Damage inflicted on fishermen's nets and rare attacks on off-shore fish farms in Turkey and Greece are known to have pushed local people towards hunting the Mediterranean monk seal, but mostly out of revenge, rather than population control. Preservation efforts have been put forth by civil organizations, foundations, and universities in both countries since as early as the 1970s. For the past 10 years, many groups have carried out missions to educate locals on damage control and species preservation. Reports of positive results of such efforts exist throughout the area.[67]

In the Aegean Sea, Greece has allocated a large area for the preservation of the Mediterranean monk seal and its habitat. The Greek Alonissos Marine Park, that extends around the Northern Sporades islands, is the main action ground of the Greek MOm organisation.[68] MOm is greatly involved in raising awareness in the general public, fundraising for the helping of the monk seal preservation cause, in Greece and wherever needed. Greece is currently investigating the possibility of declaring another monk seal breeding site as a national park, and also has integrated some sites in the NATURA 2000 protection scheme. The legislation in Greece is very strict towards seal hunting, and in general, the public is very much aware and supportive of the effort for the preservation of the Mediterranean monk seal.

The complex politics concerning the covert opposition of the Greek government towards the protection to the monk seals in the eastern Aegean in the late 1970s is described in a book by William Johnson.[69] Oil companies apparently may have been using the monk seal sanctuary project as a stalking horse to encourage greater cooperation between the Greek and Turkish governments as a preliminary to pushing for oil extraction rights in a geopolitically unstable area. According to Johnson, the Greek secret service, the YPEA, were against such moves and sabotaged the project to the detriment of both the seals and conservationists, who, unaware of such covert motivations, sought only to protect the species and its habitat.

One of the largest groups among the foundations concentrating their efforts towards the preservation of the Mediterranean monk seal is the Mediterranean Seal Research Group (Turkish: Akdeniz Foklarını Araştırma Grubu) operating under the Underwater Research Foundation (Turkish: Sualtı Araştırmaları Derneği) in Turkey (also known as SAD-AFAG). The group has taken initiative in joint preservation efforts together with the Foça municipal officials, as well as phone, fax, and email hotlines for sightings.[70]

Preservation of the species requires both the preservation of land and sea, due to the need for terrestrial haul-out sites and caves or caverns for the animal to rest and reproduce. Even though responsible scuba diving instructors hesitate to make trips to known seal caves, the rumor of a seal sighting quickly becomes a tourist attraction for many. Irresponsible scuba diving trips scare the seals away from caves which could become habitation for the species.

The Environment and Urbanization Minister of Turkey announced on 18 November 2019 that a plan was proposed to further preserve the species to allow the sub species of Foça, Gökova, Datça and Bozburun to increase in numbers.[71]

Under the auspices of the Convention on Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS), also known as the Bonn Convention, the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) concerning Conservation Measures for the Eastern Atlantic Populations of the Mediterranean Monk Seal was concluded and came into effect on 18 October 2007. The MoU covers four range States (Mauritania, Morocco, Portugal and Spain), all of which have signed, and aims at providing a legal and institutional framework for the implementation of the Action Plan for the Recovery of the Mediterranean Monk Seal in the Eastern Atlantic.

As there are indications of small population increases in the subpopulations, as of 2015, the Mediterranean monk seal's IUCN conservation status has been updated from critically endangered to endangered in keeping with the IUCN's speed-of-decline criteria.[1]

The Mediterranean monk seal occasionally appears in Classical mythology. In Homer's The Odyssey, the sea god Proteus is shown herding monk seals for Poseidon. The mythical hero Phocus of Aegina (with phokos literally translating to seal in Greek) was the son of the nereid Psamathe, and was conceived while she was transformed into a seal. The ancient city of Phocis (and possibly Phocaea) was named after Phocus, and the city of Phocaea took on the monk seal as an emblem. This has been thought to either be due to the myth of Phocus' birth, or monk seals formerly inhabiting the area where Phocaea was established. There is only a single known surviving depiction of the monk seal from antiquity, this being on a Caeretan hydria likely created by Phocaean refugees in Etruria.[72]

Despite its mythological connections and association with certain peoples, the monk seal still seems to have been generally been reviled and feared by the ancient Greeks and Romans due to its form and smell, as well as its association with the unknown nature of the ocean. Many Greek and Roman metaphors and idioms portrayed the seal in a negative light. This antipathy may have contributed to its long-term decline in numbers by spurring persecution of the species.[72]

In the 11th century BC, the Assyrian king Tiglath-Pileser I was gifted several animals by the Egyptian pharaoh Ramesses XI, including a crocodile and an unknown creature known as the "river-man". These animals were displayed in the menagerie of his son Ashur-bel-kala, and are portrayed on several of Ashur's obelisk fragments. A pair of hind flippers on one partial fragment has been identified with the "river-man", and if so indicate that the "river man" was almost certainly a monk seal.[73]

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) The Mediterranean monk seal (Monachus monachus) is a monk seal belonging to the family Phocidae. As of 2015, it is estimated that fewer than 700 individuals survive in three or four isolated subpopulations in the Mediterranean, (especially) in the Aegean Sea, the archipelago of Madeira and the Cabo Blanco area in the northeastern Atlantic Ocean. It is believed to be the world's rarest pinniped species. This is the only species in the genus Monachus.

La Mediteranea monaĥfoko (Monachus monachus) aŭ pli simple la Mediteranea foko estas fokulo apartenanta al la familio de Fokedoj. Kun nur ĉirkaŭ 450–510 (ĉiukaze mal pli ol 600[1]) restantaj individuoj, oni supozas, ke ĝi estas la plej rara fokospecio en la mondo, kaj unu el plej endanĝeritaj mamuloj en la mondo.

Ĝi loĝas nune en partoj de la Mediteranea Maro same kiel en areoj de la Atlantika Oceano ĉe la Tropiko de Kankro.

La Mediteranea monaĥfoko estas unu el du restantaj monaĥfokaj specioj; dum la alia estas la Havaja monaĥfoko. Tria specio, nome la Kariba monaĥfoko, iĝis formortinta.

La Mediteranea monaĥfoko (Monachus monachus) aŭ pli simple la Mediteranea foko estas fokulo apartenanta al la familio de Fokedoj. Kun nur ĉirkaŭ 450–510 (ĉiukaze mal pli ol 600) restantaj individuoj, oni supozas, ke ĝi estas la plej rara fokospecio en la mondo, kaj unu el plej endanĝeritaj mamuloj en la mondo.

Ĝi loĝas nune en partoj de la Mediteranea Maro same kiel en areoj de la Atlantika Oceano ĉe la Tropiko de Kankro.

La Mediteranea monaĥfoko estas unu el du restantaj monaĥfokaj specioj; dum la alia estas la Havaja monaĥfoko. Tria specio, nome la Kariba monaĥfoko, iĝis formortinta.

La foca monje del Mediterráneo o foca fraile mediterránea (Monachus monachus) es una especie de mamífero pinnípedo de la familia de los fócidos, una de las más raras que existen. Se encuentra en grave peligro de extinción; antiguamente poblaba las aguas de todo el Mediterráneo y del Atlántico norteafricano, llegando a las islas de Cabo Verde, Madeira y las Canarias (donde dio nombre al islote de Lobos) así como a toda la costa norteafricana.

Citada por primera vez en la Odisea de Homero, se han encontrado restos óseos de estas focas en cuevas de Málaga pertenecientes a los periodos Magdaleniense y Epipaleolítico hace entre 14 000 y 12 000 años. Las marcas, fracturas y quemaduras detectadas en estos huesos indican que la gente de esos periodos utilizaba a las focas no solo por la carne sino también por la piel y la grasa.

Existen aún por todo el litoral muchos topónimos que hacen referencia a la especie, «Cueva de la Vaca», «Punta del Lobo», «Cueva del Lobo Marino», «Isla de Lobos», «Arrecife de las Sirenas», etc. sitios donde las focas monje (también conocidas como lobos o vacas marinas) comían o salían a descansar.

A comienzos del siglo XX la foca monje fue expulsada del litoral más llano, gran parte de Cataluña, Levante y la Costa del Sol; relegándolas a las partes más escarpadas de la Costa Brava y en la franja de litoral que va desde el cabo San de Antonio en Alicante al cabo de Gata en Almería, y las Baleares. Pero en los años 50 comienza el boom de la Costa Brava y también desaparecen de allí, mientras que en Mallorca (1951) se produce la última reproducción confirmada en España y, poco a poco, van desapareciendo de la clandestinidad que le proporcionaban las cuevas al borde de los acantilados marinos.

Los dos últimos ejemplares de foca monje en las Baleares (conocida popularmente como «vell marí»), fueron exterminados en Mallorca en 1958, uno de ellos sacrificado entre las redes de los pescadores de Cala Mondragó, en Santañí, y el otro fue abatido a tiros por un Guardia Civil en la Cala Tuent, Escorca, en abril de 1958.[2] Tras ser abatida, Lluís Gasull de la Societat D'Historia Natural, pudo medir su cadáver, por lo que hoy sabemos lo que midió la última foca de las islas Baleares; 2,52 metros.

En las islas Canarias, la extinción fue anterior y por otros motivos. Aquí las colonias de focas eran muy numerosas -con varios millares de ejemplares-, pero durante la conquista de Canarias fueron cazadas por los normandos y castellanos para la obtención de cuero, grasa y carne, provocando su desaparición.

En 1951 moría en Alicante la última cría peninsular conocida, víctima de un hachazo. Hasta mediados de los años 60 un pequeño grupo de focas sobrevivió en el cabo de Gata y en 1979 se avistó por última vez en la Isla del Fraile de Águilas Murcia. La persecución fue tal que en los años 70 solo se conocían cinco ejemplares en las costas españolas; a comienzos de los 80 solo quedaba uno.

Actualmente, las islas Chafarinas, a 27 millas náuticas al este de Melilla, son el único lugar de la costa española donde existe la especie, representada por uno o dos ejemplares. Hasta principios de los noventa vivía en estas islas el célebre «Peluso», un macho de avanzada edad que se haría popular tras una aparatosa operación de captura para liberarle de un aro de una red de pesca que le aprisionaba el cuerpo, y que murió posteriormente por causas desconocidas.[3]

Los ejemplares que se avistan esporádicamente en la actualidad en las Chafarinas pertenecen a la exigua población argelino-marroquí que vive desde Orán hasta Alhucemas. Según recientes datos la población se habría extinguido al menos en las costas argelinas[4] aunque no se descarta la presencia de algún ejemplar aislado en las costas marroquíes.

Sin embargo, el 17 de junio de 2008 apareció la noticia[5] de que un ejemplar de la especie había sido fotografiado por un submarinista en la reserva marina de Isla del Toro (Calviá, Mallorca). La Consejería de Medio Ambiente certificó el avistamiento y constató que se habían dado otros cuatro en la misma zona. Por lo que se intentaría conocer el sexo de la foca para así poder traerle una pareja.

Hoy subsisten diversos ejemplares en Turquía, Grecia, Madeira, Mauritania; los animales no forman colonias estables debido a la gran dispersión de estos, y la investigación que se lleva a cabo se basa solo en los esporádicos avistamientos de algún ejemplar. En la península del Cabo Blanco (Sáhara Occidental - Mauritania) subsiste la última gran colonia de focas monje, descubierta en 1945 por el naturalista español Eugenio Morales Agacino.[6] La colonia está cifrada en unos 200 ejemplares, de un total mundial estimado en unos 500 individuos (estimación del año 2006). Esta situación es muy peligrosa para la supervivencia de la especie, como se demostró en mayo de 1997, año en que se dio una mortandad masiva de focas en la colonia, debida seguramente a una toxina paralizante segregada por una alga dinoflagelada. Esta epizootia acabó con dos tercios de la población existente, y además el 95% de los individuos muertos pertenecían al segmento adulto de la población.

En España es muy difícil avistar algún ejemplar tras la desaparición del último macho, «Peluso», de las islas Chafarinas situadas en la costa norte de África cercanas a Marruecos, por lo que se le considera una de las especies más raras de la fauna ibérica.

Un estudio realizado por el Ministerio de Medio Ambiente de Italia en 2013 confirma la presencia de la foca monje en el área marina protegida en las islas Egadas[7]

En el año 2014 el censo total era de unos 630 ejemplares repartidos por la zona atlántica y mediterránea:

Costa atlántica:

Costa mediterránea:

Se desconoce el censo en el litoral de Túnez, sin embargo ha habido avistamientos esporádicos en el canal de Sicilia, tanto en las islas Egadas, dentro del Área Marina Protetta Isole Egadi como en la Lampedusa en el Área Marina Protetta Isole Pelagie. Al norte, en la isla de Cerdeña también ha habido avistamientos esporádicos, en concreto en Castelsardo.

Considerando que en la antigua área de distribución de la foca monje existen numerosas zonas protegidas en buen estado de conservación se han creado distintos proyectos de recuperación como el de la Dirección General de Conservación de la Naturaleza del Ministerio de Medio Ambiente y la Viceconsejería de Medio Ambiente de Canarias.[8]

El objetivo es recuperar la especie para la fauna española mediante su reintroducción en las islas Canarias orientales, ya que las mismas se encuentran a medio camino geográficamente entre la colonia de Madeira y la de cabo Blanco. De esta forma se podría restablecer el corredor natural genético entre ambos núcleos, que ahora están aislados.

Además, estas islas poseen un adecuado número de espacios naturales protegidos y con un buen nivel de conservación, y reúnen suficiente capacidad biológica para albergar una población de focas, dada su riqueza en especies —presa potenciales— y su baja contaminación marina.

Otros proyectos similares son el Plan de Acción Internacional para la Recuperación de la Foca Monje en el Atlántico Oriental, dentro del Convenio Especies Migratorias o Convenio de Bonn, en el que participan varios países y entidades, así como el Fondo para la foca monje (FFM) y el proyecto de la Fundación Territorio y Paisaje, creada por Caixa Catalunya.[9]

La foca monje del Mediterráneo o foca fraile mediterránea (Monachus monachus) es una especie de mamífero pinnípedo de la familia de los fócidos, una de las más raras que existen. Se encuentra en grave peligro de extinción; antiguamente poblaba las aguas de todo el Mediterráneo y del Atlántico norteafricano, llegando a las islas de Cabo Verde, Madeira y las Canarias (donde dio nombre al islote de Lobos) así como a toda la costa norteafricana.

Citada por primera vez en la Odisea de Homero, se han encontrado restos óseos de estas focas en cuevas de Málaga pertenecientes a los periodos Magdaleniense y Epipaleolítico hace entre 14 000 y 12 000 años. Las marcas, fracturas y quemaduras detectadas en estos huesos indican que la gente de esos periodos utilizaba a las focas no solo por la carne sino también por la piel y la grasa.

Itsas txakur fraide (Monachus monachus) Monachus generoko animalia da. Artiodaktiloen barruko Phocidae familian sailkatuta dago. ugaztun pinnipedoa da, Phocidae familiakoa. Garai batean Mediterraneo, Afrikako mendebaldeko itsas ertzetan, Kanariar, Madeira eta Cabo Verden ohikoa zen espezia hau, gau egun oso arraroa da eta desagertzeko egoera larrian dago. 2006an 500 animalia gelditzen omen ziren; kolonia nagusia Mendebaldeko Sahara eta Mauritania artean, Ras Nouadhiboun dago, 200 inguruko animaliekin.[3]

Espezie honen lurralde historikoetan ongi kontserbatuta zonaldeak aurki daitezke. Horretan baliatuta espeziea berreskuratzeko proiektu desberdinak daude martxan. Garrantzitsuenetariko bat Kanariar uhartetan berriro sartzeko proposamena dago. Lortuko balitz Ras Nouadhibou Madeiraraino korridore bat eskuratuko litzateke gaur egun isolaturik dauden animaliak elkartzeko.[4]

Itsas txakur fraide (Monachus monachus) Monachus generoko animalia da. Artiodaktiloen barruko Phocidae familian sailkatuta dago. ugaztun pinnipedoa da, Phocidae familiakoa. Garai batean Mediterraneo, Afrikako mendebaldeko itsas ertzetan, Kanariar, Madeira eta Cabo Verden ohikoa zen espezia hau, gau egun oso arraroa da eta desagertzeko egoera larrian dago. 2006an 500 animalia gelditzen omen ziren; kolonia nagusia Mendebaldeko Sahara eta Mauritania artean, Ras Nouadhiboun dago, 200 inguruko animaliekin.

Munkkihylje (Monachus monachus) on Välimerellä ja sen ympäristössä elävä uhanalainen hyljelaji. Se on yksi alkeellisista munkkihylkeistä.

Munkkihylje on 2,5–3-metrinen ja jopa 300 kilon painoinen. Naaraat ovat koiraita suurempia. Väri vaihtelee alueittain hieman. Selkä on yleensä tummanharmaa tai ruskehtava. Toisinaan rinnasta alavatsalle ulottuu suuri valkeankellertävä alue. Poikanen on musta. Aikuisen karva on korkeintaan 5 senttiä pitkä. Takaevät ovat myös karvaiset.

Munkkihylje elää vain laikuttaisesti Välimerellä, Mustallamerellä ja Afrikan luoteisrannikolla. Sitä tavataan myös Kap Verdessä, Madeiralla, Kanariansaarilla ja Azorereilla. Munkkihylje on hävinnyt Israelin, Ranskan, Egyptin,Libanonin, Italian, Espanjan, Portugalin ja Sardinian rannikoilta. Laji suosii rauhallisia rannikkovesiä.

Munkkihylje liikkuu vaihtelevan kokoisissa ryhmissä. Se oleskelee mieluiten alueilla, joissa on kallioluolia. Se myös viihtyy rauhallisilla rannoilla. Munkkihylje saalistaa yleensä pimeällä, jolloin se etsii nukkuvia eläimiä. Ruokalistalle kuuluu pääjalkaisia ja kaloja. Munkkihylje lisääntyy kesällä. Ne parittelevat vedessä, mutta poikasen ne synnyttävät johonkin suojaisaan paikkaan kuten kallioluolaan. Poikanen pystyy uimaan parin viikon ikäisenä ja emo vieroittaa poikasen 6–8-viikkoisena. Tämän jälkeen poikanen pysyy emon seurassa pari vuotta, mikä on hylkeelle paljon. Sukukypsyyden poikanen saavuttaa 3–4-vuotiaana. Hylje voi elää 30-vuotiaaksi.

Munkkihylje on erittäin uhanalainen ja sen kanta on enää 400–500 yksilöä. Suurin syy vähenemiseen on liiallinen häirintä rakentamisen ja muun ihmistoiminnan takia. Kalastajat pitävät hyljettä uhkana elinkeinolleen, koska se repii verkkoja ja syö niistä kaloja. Usein munkkihylkeet myös hukkuvat verkkoihin. Hylkeen tilannetta ovat pahentaneet turismi, saastuminen ja kalakantojen heikentyminen. Turismin lisääntyminen estää usein naaraiden lekottelun rannalla, eikä niiden elimistössä siksi muodostu riittävästi sikiölle välttämätöntä D-vitamiiniaLähteet Viitteet

Aiheesta muualla

Munkkihylje (Monachus monachus) on Välimerellä ja sen ympäristössä elävä uhanalainen hyljelaji. Se on yksi alkeellisista munkkihylkeistä.

Monachus monachus

Le phoque moine de Méditerranée (Monachus monachus) est une espèce de pinnipèdes rencontrée en Méditerranée, mais aussi sur les côtes de Madère, du Sahara occidental et de Mauritanie. Il est en danger, c'est la plus menacée des espèces de pinnipèdes.

Le mâle mesure en moyenne 2,4 m de long, la femelle est légèrement plus petite. Le mâle pèse environ 315 kg et la femelle 300 kg[1].