en

names in breadcrumbs

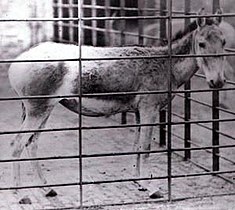

Suriya qulanı[1] (lat. Equus hemionus hemippus) — Ərəbistan yarımadasında vaxtı ilə yayılmış qulan yarımnövü. Bu canlıların hazırda nəsli nəsilmişdir. Onlara əsasən müasir Suriya, İsrail, İordaniya, Səudiyyə Ərəbistanı və İraq ərtazisində müşahidə edilirdi.

Suriya qulanı ortalam olraq cəmi 1 metr hündürlüyə malik idi[2]. Bu isə onların müasir atlar fəsiləsinə daxil olan heyvanlar arasına ən kiçiyi olmması anlamına gəlir[3]. Onun rəngi mövsümdən asılı olaraq dəyişir:yayda zeytuni rəng, qışda isə solğun sarı[2][4]. Digər kulanlar kimi, qətiyyətsiz təbiəti ilə məşhur idi üstəlik qüvvət və gözəlliklə hər tərəfli ata bənzəyirdi[3].

Suriya qulanı əsasən səhra və yarımsəhralarda, quraq dağ çöllərində yayılmışdılar. Onlara əsasən müasir Suriya, İsrail, İordaniya, Səudiyyə Ərəbistanı və İraq ərtazisində müşahidə edilirdi.

Ot yeyən bir canlı olmuşdur. Əsasən ot bitkiləri, kol və ağacların yarpaqları ilə qidalanırdılar.

Suriya qulanı Ərəbistan yarıçmadasınad yırtıcıların əsas hədəflərindən idilər. Ərəbistab yarımadasında yayılmış Asiya şiri. Ərəbistan bəbiri, zolaqlı kaftar, Ərəbistan canavarı və Turan pələngi kimi canlılar tərəfindən ovlanılırdı. Asiya hepardıda böyük ehtimalla bu canlıları dağ silsilələri ərsazisində ovlamışdır.

XV - XVI əsrlərdə Yaxın Şərqə səyahət edən avropalı səyyahlar burada sürü halında qulanlara rast gəldiyini bildirirdilər[5]. Bununla belə onların sayı XVIII və XIX əsrlər arasında kütləvi ovlanma səbəbindən azalmağa başlamışdır. Sonradan isə Birinci Dünya müharibəsi zamanı onların populyasiyası ciddi zərər görmüşdür. Sonuncu çöl qulanı 1927-ci ildə İordaniyanın Arzak vahəsində ovlanmışdır. Sonuncu papalı şərtaitdə saxlanan Suriya qulanı isə Vyananın Şyonbrun parkında ölmüşdür[6].

Quranın Muddəssir surəsinin 50-ci (Onlar sanki vəhşi eşşəklərdir) və 51-ci ayələrində (O eşşəklər ki aslandan hürküb qaçarlar!) keçərli olan vəhşi eşşəklərin Suriya qulanı olması ehtimal edilir. Bu surədə Allaha (c.a.c) inanmayanların mövcud halları təsvir edilir. Tövratın birinci kitabı olan Yaradılışda İsmayıl peyğəmbərlə əlaqəli rəvayətdə təsvir edilən vəhşi eşşək Suriya qulanıdır.

Suriya qulanının nəsli kəsildikdən sonra yaranmış boşluğu doldurmaqdan ötrü İran qulanı uyğun gələn yarımnöv hesab edilərən Yaxın Şərqdə yayılması üçün tədbirlər görülmüşdür. Onlar Səudiyyə Ərəbistanı və İordaniyanın qoruma ərazilərində yerləşdirilmişdir. Bundan əlavə İsraildə İran qulanı ilə yanaşı Türkmən qulanıda gətirilərək təbiətə buraxılmışdır.

Suriya qulanı (lat. Equus hemionus hemippus) — Ərəbistan yarımadasında vaxtı ilə yayılmış qulan yarımnövü. Bu canlıların hazırda nəsli nəsilmişdir. Onlara əsasən müasir Suriya, İsrail, İordaniya, Səudiyyə Ərəbistanı və İraq ərtazisində müşahidə edilirdi.

Der Syrische Halbesel (Equus hemionus hemippus), auch als Syrischer Onager, Syrischer Wildesel, Hemippe oder lokal als Achdari bezeichnet, ist eine ausgestorbene Unterart des Asiatischen Esels (Equus hemionus). Er gilt als kleinste Form der modernen Equidae.

Der Syrische Halbesel erreichte eine Schulterhöhe von etwa 100 cm (Angaben von nur 97 cm Schulterhöhe basieren auf einem montierten Skelett eines weiblichen Tieres, das mit Weichteilbedeckung etwas über einen Meter hoch gewesen sein dürfte).[1] Die allgemeine Fellfärbung des Männchens war hasel- oder hellgrau mit einer rosa Tönung. Im Alter färbte sich das Fell mausgrau. Am Kopf war die Färbung am hellsten und an den Hüften am dunkelsten. An der Vorderseite der Hüften war ein heller Bereich zu erkennen. Hinterteil, Bauch und Innenseite der Beine waren schmutzig grau-weiß. Die Außenseite der Beine, die Unterseite des Halses und die Oberfläche der Ohren waren stumpf violettgrau. Die Ohrenspitzen waren zunächst dunkelbraun, im Alter waren sie fast weiß. Die ziemlich lange Mähne war stumpf graubraun. Der Aalstrich, der sich von der Mähne bis zum Schwanzbüschel erstreckte, hatte dieselbe Färbung und wurde von einem helleren Bereich begrenzt. Der Bereich oberhalb der Nüstern war grauweiß. Die Nüstern waren sehr groß und der Nasalbereich geschwollen. Bei den Weibchen war die Fellfärbung haselnuss- bis rehbraun. Das Hinterteil und die Unterseite waren reinweiß.

Das Verbreitungsgebiet erstreckte sich von Palästina über Syrien bis zum Irak.

Bereits in der Antike und den Schriften des Alten Testaments wird der Syrische Halbesel erwähnt. Eine Jagddarstellung befindet sich auf einem Palast-Relief des Königs Aššur-bāni-apli von Ninive. Eine weitere Erwähnung gibt es bei Xenophon aus dem Jahr 401 v. Chr.[2] Während des 16. und 17. Jahrhunderts war der Syrische Halbesel noch häufig. Der britische Forschungsreisende John Eldred sah diese Wildesel 1584 zwischen der irakischen Stadt Hīt und Aleppo; Der englische Reisende John Cartwright erblickte 1603 nicht weit von Anah am Euphrat „jeden Tag große Scharen von wilden Tieren, die wie die Wildesel ganz weiß waren.“ 1625 beschrieb der italienische Reisende Pietro della Valle einen gefangenen Wildesel oder Onager in Basra im Südirak. Offenbar verschwand der Syrische Halbesel während des 19. Jahrhunderts aus Nord-Arabien, in der Syrischen Wüste und in Palästina wurde er ab 1850 immer seltener. Nach Angaben von Henry Baker Tristram waren die Wildesel gegen 1884 in Mesopotamien noch häufig. Er schrieb, dass man im Sommer noch große weiße Herden in den armenischen Bergen beobachten konnte.[3] Der letzte Zufluchtsort der Syrischen Halbesel war das Lavaland im Südosten von Dschebel ad-Duruz, eine erhöhte vulkanische Region im Süden Syriens, im Regierungsbezirk as-Suwaida.

Mehrere Autoren geben an, dass der letzte Syrische Halbesel in menschlicher Obhut 1927 im Tiergarten Schönbrunn starb[4]. Dagegen schrieb der Zoologe Otto Antonius, dass im selben Zoo 1928 noch ein männliches Exemplar lebte, das 1911 in der Wüste nördlich von Aleppo gefangen worden war.[5] In der Wildnis starb der Syrische Halbesel etwa zur selben Zeit aus. Das letzte Exemplar wurde 1927 in Jordanien bei der Al-Gharns-Oase unweit des el-Azraq (Azraq-See) geschossen. Während des Ersten Weltkrieges wurden die Halbesel ein leichtes Jagdopfer für die schwer bewaffneten türkischen, beduinischen und britischen Truppen. Während dieser Zeit verdrängte das Automobil Kamele und Züge, und der Zugang zur Wüste wurde stark erleichtert. Otto Antonius schrieb 1938:

„Er (der Wildesel) konnte der Kraft der modernen Schußwaffen in den Händen der Anaza- und Schammar-Nomaden nichts entgegensetzen und seine Geschwindigkeit, so groß sie auch gewesen sein mag, war nicht ausreichend gegen die der modernen Automobile, die mehr und mehr die Kamelkarawanen des Alten Testaments ersetzten.“[6]

Der Syrische Halbesel (Equus hemionus hemippus), auch als Syrischer Onager, Syrischer Wildesel, Hemippe oder lokal als Achdari bezeichnet, ist eine ausgestorbene Unterart des Asiatischen Esels (Equus hemionus). Er gilt als kleinste Form der modernen Equidae.

The Syrian wild ass (Equus hemionus hemippus), less commonly known as a hemippe,[2] an achdari,[3][4] or a Mesopotamian or Syrian onager,[5] is an extinct subspecies of onager native to the Arabian peninsula and surrounding areas. It ranged across present-day Iraq, Palestine, Israel, Iran, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Syria, and Turkey.

The Syrian wild ass, one metre high at its shoulder,[6] was the smallest equine, and it could not be domesticated.[7] Its coloring changed with the seasons — a tawny olive coat for the summer months, and pale sandy yellow for the winter.[6][8] It was known, like other onagers, to be untameable, and was compared to a thoroughbred horse for its beauty and strength.[7]

The Syrian wild ass lived in deserts, semi-deserts, arid grasslands, and mountain steppes. Native to West Asia, they were found in Israel, Palestine, Jordan, Turkey, Syria, Saudi Arabia, and Iraq.

The Syrian wild ass was a grazer and a browser. It fed on grass, herbs, leaves, shrubs, and tree branches.

Syrian wild asses were preyed upon by Asiatic lions,[9] Arabian leopards, striped hyenas, Syrian brown bears, Arabian wolves, and Caspian tigers. Asiatic cheetahs and golden jackals may have also preyed on foals.

The bones of a Syrian wild ass have been identified at an 11,000 year-old archaeological site at Göbekli Tepe, Turkey.[10] Cuneiform from the third millennium BCE report the hunting of an 'equid of the desert' (anše-edin-na), valued for its meat and hide, which may have been E.h. hemippus.[11] Although Syrian wild asses were not themselves domesticated, a significant breeding center at Tell Brak produced a hybrid of the wild ass and the donkey, called the kunga, that was a draft animal of high economic and symbolic value to the elite of Syria and Mesopotamia.[11][12][13] They appear in cuneiform inscriptions and their bones are found in burials from the third millennium BCE. The size of these hybrids, larger than modern examples of both parent species, has led to speculation that the Syrian wild asses used historically in breeding the kunga were of larger size than the individuals observed in the remant populations of the 18th and 19th centuries.[11]

Assyrian art from the 7th century BCE found at Nineveh includes a scene of hunters capturing Syrian wild asses with lassos.

Xenophon of Athens mentions Syrian wild asses in his Anabasis of ~370 BCE. He reports that they were the most common of animals encountered in Syria; in addition to ostriches, bustards, and gazelles. Xenophon states that horsemen would occasionally chase the asses, with the asses easily able to outrun the horses. He said that asses would only run a short distance ahead of the horses before stopping, waiting for the horses to get closer, and then running ahead yet again. He described the asses as impossible to catch without careful planning. Xenophon also related that the meat of the asses tasted like a more tender version of venison.

It is believed this may be the "wild ass" that Ishmael was prophesied to be in Genesis in the Old Testament. References also appear in the Old Testament books of Job, Psalms, Jeremiah, and the Deuterocanonical book of Sirach.[14] The Qur’an, the main book of Islam, in Surat al-Muddaththir, refers to a scene of humur (Arabic: حُـمـر, 'asses' or 'donkeys' in plural form, حمار singular) fleeing from a qaswarah (Arabic: قَـسـورة, 'lion'). This was to criticize people who were averse to Muhammad's teachings, such as supporting the welfare of the less wealthy.[9]

In addition to the Bronze Age kunga, a couple of modern hybrids were produced by the London Zoo in the late 19th century. In 1878, a Syrian wild ass was crossed with an Indian wild ass (a different subspecies), and in 1883 an inter-species cross between a Syrian wild ass male and an Abyssinian wild ass female produced a foal that was colored like the sire, and described as "a fine animal" but "vicious and untamed".[15]

European travelers in the Middle East during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries reported seeing large herds.[14] However, its numbers began to drop precipitously during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries due to overhunting, and its existence was further imperiled by the regional upheaval of World War I. The last known wild specimen was fatally shot in 1927 at al Ghams near the Azraq oasis in Jordan, and the last captive specimen died the same year at the Tiergarten Schönbrunn, in Vienna.[16]

After the extinction of the Syrian wild ass, the Persian onager from Iran was chosen as an appropriate subspecies to repopulate the Middle East as a replacement for the extinct E. h. hemippus onagers. The Persian onager was then introduced to the protected areas of Saudi Arabia and Jordan. It also was reintroduced, along with the Turkmenian kulan, to Israel, where they both reproduce wild ass hybrids in the Negev Mountains and the Yotvata Hai-Bar Nature Reserve.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) The Syrian wild ass (Equus hemionus hemippus), less commonly known as a hemippe, an achdari, or a Mesopotamian or Syrian onager, is an extinct subspecies of onager native to the Arabian peninsula and surrounding areas. It ranged across present-day Iraq, Palestine, Israel, Iran, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Syria, and Turkey.

El asno salvaje sirio o hemipo (Equus hemionus hemippus) es una subespecie extinta de asno salvaje asiático.[2] Parece ser que fue domesticado en la Edad Antigua en Mesopotamia por los sumerios antes de que conocieran el caballo.[3] Su distribución original comprendía desde Palestina hasta Irak.[4]

Pese a estar extinto, es conocido por descripciones de cazadores y viajeros, así como por algunas pieles y esqueletos de colecciones de museo y por el registro arqueológico.[5]

En varios relatos y tradición oral, aparece esta especie, como la que llevó a María embarazada del Niño Jesús a Belén. También y posteriormente sería uno de estos equinos el que entraría a cuestas a Jesús para su muerte. Está representado en el pesebre, frente a María. En algunas regiones de España se dice que era una borriquilla, es decir un ejemplar hembra.[cita requerida]

Era el équido de complexión más ligera y de menor tamaño,[6] alcanzando hasta un metro de altura en la cruz.[7] Como todas las subespecies de asno salvaje asiático, tenía las orejas más cortas que las de los asnos africanos (Equus asinus) y más largas que las de los caballos (Equus ferus).[3] Asimismo difiere de los caballos en que, como el asno africano, tenía la cola desnuda en la base.[3] Su coloración era rojiza oliva en verano, cambiando en invierno a un amarillo pálido.[7]

Los huesos de un asno salvaje sirio han sido identificados en un yacimiento arqueológico de 11000 años de antigüedad en Göbekli Tepe, Turquía.[8] La escritura cuneiforme del III milenio a. C. informa de la caza de un 'équido del desierto' (anše-edin-na), valorado por su carne y piel, que puede haber sido E.h. hemippus.[9] Aunque los asnos salvajes sirios no fueron domesticados, un importante centro de cría en Tell Brak produjo un híbrido de asno salvaje y burro, llamado kunga, que era un animal de tiro de alto valor económico y simbólico para la élite de Siria y Mesopotamia.[9][10][11] Aparecen en inscripciones cuneiformes y sus huesos se encuentran en enterramientos del III milenio a. C. El tamaño de estos híbridos, más grandes que los ejemplares modernos de ambas especies parentales, ha llevado a especular que los asnos salvajes sirios utilizados históricamente en la crianza de los kungas eran de mayor tamaño que los individuos observados en las poblaciones remanentes de los siglos XVIII y XIX.[9]

El arte asirio del siglo VII a. C. encontrado en Nínive incluye una escena de cazadores que capturan asnos salvajes sirios con lazos.

Estaba distribuido desde el sur de Siria hasta la península arábiga,[1] encontrándose en Irak, Jordania y Palestina.[12] Era un animal común en tiempos históricos en el desierto de Siria,[7] donde habitaba principalmente en llanuras aluviales.[5]

El asno salvaje sirio o hemipo (Equus hemionus hemippus) es una subespecie extinta de asno salvaje asiático. Parece ser que fue domesticado en la Edad Antigua en Mesopotamia por los sumerios antes de que conocieran el caballo. Su distribución original comprendía desde Palestina hasta Irak.

Jatorrizko herrialdea(k): Siria

Siriako onagroa, Equus hemonius hemippus, edo Siriako basastoa, izen arrunta hemippe egun desagertutako onagro mota bat da[1]. Bere banaketa eremua Arabiar penintsula zen. Sirian, Israel,en, Jordanian, Saudi Arabian eta Iraken. Abere hau onagroen artean kokatzen da.

Dirudienez Antzinaroan Mesopotamiako sumertarrek Siriako basastoa etxekotu zuten bertan etxeko zaldia ezagutu baino lehen. Siriako basamortuko abere arrunta omen zen. Bertan bereziki ibai alboko ordoki alubioietan larretzen zen.

Siriako onagroa, Equus hemonius hemippus, edo Siriako basastoa, izen arrunta hemippe egun desagertutako onagro mota bat da. Bere banaketa eremua Arabiar penintsula zen. Sirian, Israel,en, Jordanian, Saudi Arabian eta Iraken. Abere hau onagroen artean kokatzen da.

Sakontzeko, irakurri: «Onagro»Âne sauvage de Syrie

L’âne sauvage de Syrie, onagre de Syrie ou encore Hémippe était une sous-espèce du genre Equus et une sous-espèce d’Equus hemionus décrite par Saint-Hilaire.

L'hémippe, haut d'un mètre au garrot[1], était le plus petit équidé et il ne pouvait pas être domestiqué[2]. Sa coloration changeait avec les saisons : un pelage olive fauve pour les mois d'été et jaune sable pâle pour l'hiver[1],[3]. Il était connu, comme les autres onagres, pour être indomptable et était comparé à un cheval pur-sang pour sa beauté et sa force[2].

L'hémippe vivait en Irak, Syrie, Palestine, Jordanie et dans péninsule arabique. Son biotope était constitué de déserts, semi-déserts, prairies arides et steppes de montagne.

L'âne sauvage de Syrie était un brouteur. Il se nourrissait d'herbes, de feuilles, d'arbustes ou de branches d'arbres.

Les ânes sauvages syriens étaient la proie des lions asiatiques, des léopards d'Arabie, des hyènes rayées, des ours bruns de Syrie, des loups d'Arabie et des tigres de la Caspienne. Les guépards asiatiques et les chacals dorés ont pu également avoir chassé leurs poulains.

Les os d'un âne sauvage syrien ont été identifiés sur un site archéologique datant de 11 000 ans à Göbekli Tepe, en Turquie[4]. L'écriture cunéiforme du troisième millénaire avant notre ère rapporte la chasse d'un « équidé du désert » (anše-edin-na), apprécié pour sa viande et sa peau, qui pourrait avoir été E. h. hemippus[5]. Bien que les ânes sauvages syriens n'aient pas été eux-mêmes domestiqués, un centre d'élevage important à Tell Brak a produit un hybride de l'âne sauvage et de l'âne, appelé kunga, qui était un animal de trait d'une grande valeur économique et symbolique pour l'élite de la Syrie et de la Mésopotamie[5],[6],[7].

Le kunga, hybride d'un hémippe mâle et d'une ânesse domestique, le premier hybride d'élevage, a été utilisé comme animal de trait en Mésopotamie de 2600 avant notre ère à l'arrivée du cheval à la fin du IIIe millénaire.

Ils apparaissent dans des inscriptions cunéiformes et leurs ossements se trouvent dans des sépultures du troisième millénaire avant notre ère. La taille de ces hybrides, plus grande que les exemples modernes des deux espèces parentales, a conduit à supposer que les ânes sauvages syriens utilisés historiquement dans l'élevage du kunga étaient de plus grande taille que les individus observés dans les populations sauvages des 18e et 19e siècle[5].

L'art assyrien du 7e siècle avant notre ère trouvé à Ninive révèle une scène de chasse dans laquelle des chasseurs capturent des hémippes avec des lassos.

Xénophon d'Athènes mentionne les ânes sauvages syriens dans son Anabase datant d'environ 370 avant notre ère. Il rapporte qu'ils étaient les animaux les plus couramment rencontrés en Syrie avec les autruches, les outardes et les gazelles. Xénophon déclare que les cavaliers chassaient parfois les ânes, ces derniers pouvant facilement distancer les chevaux. Il a dit que les ânes ne courraient que sur une courte distance devant les chevaux avant de s'arrêter, d'attendre que les chevaux se rapprochent, puis de courir devant encore une fois. Il a décrit les ânes comme impossibles à attraper sans une planification minutieuse. Xénophon a également raconté que la viande des ânes avait le goût d'une version plus tendre de la venaison.

On pense que cela pourrait être « l'âne sauvage » qu'Ismaël a été prophétisé comme étant dans la Genèse de l'Ancien Testament. Des références apparaissent également dans les livres de l'Ancien Testament sur Job, les Psaumes, Jérémie et le Deutérocanonique de Siracide[8]. Le Coran, le principal livre de l'islam, dans la sourate al-Muddaththir, fait référence à une scène d'ḥumur (arabe : حُـمـر, « ânes » pluriel de حمار) fuyant une qaswara (arabe : قَـسـورة , 'Lion'), pour critiquer les personnes qui s'opposaient aux enseignements de Mahomet, comme soutenir le bien-être des moins riches.

En plus du kunga de l'âge du bronze, quelques hybrides modernes ont été produits par le zoo de Londres à la fin du 19e siècle. En 1878, un âne sauvage syrien a été croisé avec un âne sauvage indien (une sous-espèce différente), et en 1883 un croisement inter-espèces entre un mâle âne sauvage syrien et une femelle âne sauvage abyssin a produit un poulain qui était coloré comme le père, et décrit comme « un bel animal » mais « vicieux et indomptable »[9].

Les voyageurs européens au Moyen-Orient au cours des 15e et 16e siècle ont rapporté avoir vu de grands troupeaux[8]. Cependant, leur nombre a commencé à décroitre fortement au cours des 18e et 19e siècle, en raison d'une chasse excessive. Son existence a été mise en péril par les combats de la Première Guerre mondiale. Le dernier spécimen sauvage connu a été abattu en 1927 à al-Ghams près de l'oasis d'Azraq en Jordanie et le dernier spécimen captif est mort la même année au jardin zoologique de Schönbrunn, à Vienne[10].

Après l'extinction de l'âne sauvage syrien, l'onagre persan d'Iran a été choisi comme sous-espèce appropriée pour repeupler le Moyen-Orient en remplacement d'E. h. hemippus. L'onagre de Perse a ensuite été introduit dans les aires protégées d'Arabie saoudite et de Jordanie. Il a également été réintroduit, avec le kulan turkmène, en Israël, où ils produisent tous deux des hybrides d'ânes sauvages dans les montagnes du Néguev et la réserve de Hai Bar.

Âne sauvage de Syrie

L’âne sauvage de Syrie, onagre de Syrie ou encore Hémippe était une sous-espèce du genre Equus et une sous-espèce d’Equus hemionus décrite par Saint-Hilaire.

L'asino selvatico siriano (Equus hemionus hemippus (I. Geoffroy, 1855)), noto anche come emippo o localmente come achdari, è una sottospecie estinta dell'asino selvatico asiatico (Equus hemionus). Veniva generalmente considerato come la forma più piccola tra gli equidi moderni.

L'asino selvatico siriano raggiungeva un'altezza al garrese di circa 100 cm (i dati di un'altezza al garrese di soli 97 cm si basano sulla misurazione dello scheletro montato di una femmina, che ricoperto dai tessuti molli avrebbe dovuto essere alto poco più di un metro)[2]. La colorazione generale del mantello del maschio era nocciola o grigio chiaro con una sfumatura rosa. Con la vecchiaia il manto diventava color grigio topo. Il colore era più chiaro sulla testa e più scuro sui fianchi. Sulla parte anteriore dei fianchi si trovava un'area chiara. La parte posteriore, l'addome e l'interno delle zampe erano grigio-biancastro sporco. L'esterno delle zampe, la parte inferiore del collo e la superficie delle orecchie erano viola-grigiastro opaco. Le estremità delle orecchie erano inizialmente marrone scuro, ma divenivano quasi bianche con l'età. La criniera, piuttosto lunga, era grigio-brunastro opaco. La linea dorsale, che si estendeva dalla criniera al ciuffo della coda, era dello stesso colore ed era delimitata da una zona più chiara. L'area sopra le narici era grigio-biancastra. Le narici erano molto grandi e la regione nasale appariva più rigonfia rispetto al resto del muso. Nelle femmine, il mantello andava dal nocciola al marrone-fulvo. Le parti posteriori e inferiori erano di un bianco puro.

L'areale della sottospecie si estendeva dalla Palestina, attraverso la Siria, fino all'Iraq.

L'asino selvatico siriano è stato menzionato fin dall'antichità e compare già negli scritti dell'Antico Testamento. Una raffigurazione di caccia a quest'animale si trova in un bassorilievo del palazzo del re Assurbanipal a Ninive. Anche Senofonte lo citò nel 401 a.C.[3] Esso era ancora comune durante il XVI e XVII secolo. L'esploratore britannico John Eldred lo avvistò nel 1584 tra la città irachena di Hīt e Aleppo; nel 1603, non lontano da Anah sull'Eufrate, il viaggiatore inglese John Cartwright vide «ogni giorno grandi mandrie di animali selvatici simili agli asini selvatici, completamente bianchi». Nel 1625 il viaggiatore italiano Pietro Della Valle descrisse un asino selvatico od onagro in cattività a Bassora, nel sud dell'Iraq. A quanto pare l'asino selvatico scomparve dall'Arabia settentrionale durante il XIX secolo, mentre nel deserto siriano e in Palestina divenne sempre più raro dal 1850 in poi. Secondo Henry Baker Tristram, gli asini selvatici erano ancora comuni in Mesopotamia intorno al 1884 e in estate si potevano ancora vedere grandi mandrie bianche sulle montagne armene[4]. L'ultimo rifugio dell'asino selvatico siriano fu la distesa di lava nella parte sud-orientale del Gebel Druso, un'elevata regione vulcanica nel sud della Siria, nel distretto amministrativo di as-Suwayda.

Diversi autori affermano che l'ultimo asino selvatico siriano in cattività sia morto nel 1927 nello zoo di Schönbrunn[1]. Al contrario, lo zoologo Otto Antonius scrisse che nel 1928 un maschio, che era stato catturato nel deserto a nord di Aleppo nel 1911, era ancora presente nello stesso zoo[5]. In natura, l'asino selvatico siriano si estinse nello stesso periodo. L'ultimo esemplare venne ucciso in Giordania nel 1927 nell'oasi di al-Gharns non lontano da el-Azraq. Durante la prima guerra mondiale, gli asini selvatici furono una facile preda per le truppe turche, beduine e britanniche, pesantemente armate. In questo periodo l'automobile iniziò a sostituire il cammello e il treno e divenne più facile accedere al deserto. Nel 1938 Otto Antonius scrisse:

Non poteva resistere alla potenza delle armi moderne nelle mani dei nomadi Anaza e Shammar e la sua velocità, per quanto fosse grande, non era sufficiente a fuggire dai veloci mezzi a motore moderni, che andavano sostituendo le carovane di cammelli dell'Antico Testamento[6].

L'asino selvatico siriano (Equus hemionus hemippus (I. Geoffroy, 1855)), noto anche come emippo o localmente come achdari, è una sottospecie estinta dell'asino selvatico asiatico (Equus hemionus). Veniva generalmente considerato come la forma più piccola tra gli equidi moderni.

O jumento-selvagem-sírio (Equus hemionus hemippus) é uma subespécie extinta de onagro. Habitava as montanhas e desertos da Síria. O último exemplar morreu em 1928 em cativeiro.[1][2]

O jumento-selvagem-sírio (Equus hemionus hemippus) é uma subespécie extinta de onagro. Habitava as montanhas e desertos da Síria. O último exemplar morreu em 1928 em cativeiro.

시리아당나귀는 시리아 등 아라비아 반도에 서식하던 야생 당나귀이다. 남획과 서식지 파괴로 1928년에 그 모습이 사라졌다.