en

names in breadcrumbs

Since being placed on the first Endangered Species List on March 11, 1967, significant steps have been taken in order to ensure their survival, including the reservation of a 139 acre Ellicott Slough National Wildlife Refuge, in San Francisco Bay, California.(U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1986, Westphal 1996) Since the loss of habitat is one major source of impending danger to these salamanders' population, the established refuge has been a large step towards saving this rare species.

US Federal List: no special status

CITES: no special status

Development - Life Cycle: metamorphosis

Much of the 139 acres set aside for the species is of high economic value, which is lost if left undeveloped.

Both aquatic larvae and terrestrial adults are carnivorous. The larvae primarily eat small aquatic insects and arthropods. The adults also prey upon tree frog tadpoles, earthworms, slugs and various terrestrial insects.(Ferguson 1961)

The Santa Cruz long-toed salamander is a relict species, previously widespread throughout California after the Pleistocene era, and is now concentrated in the area of Santa Cruz, California.(Hukill 1997) Upon time of its discovery in 1954 until the present, this species has inhabited four locations around Santa Cruz County. They include the cities of Ellicott, Valencia, Seascape, and Bennett.(U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1986)

Biogeographic Regions: nearctic (Native )

These salamanders live in ponds, streams or lagoons in the larval stage. As terrestrial adults, the salamanders live in isolated populations in upland and mixed forests and estivate in aquatic habitats. They favor living conditions that allow their skin to stay moist and cool, and residing under forest litter does just this.(Larson 1997)

Terrestrial Biomes: forest

Aquatic Biomes: lakes and ponds; rivers and streams

Ambystoma macrodactylum croceum is a small salamander, reaching a full-grown adult length of approximately 127 mm, (5 inches). The body of an adult is a glossy black-charcoal color, with brilliant yellow and orange spots covering its back, decreasing in abundance at the top of the head, and virtually disappearing at the small black eyes. Their head is broad, blunt, and torpedo-shaped.(Duellman and Trueb 1986, Westphal 1996) Two pairs of limbs of approximately equal size are set at right angles from the rib cage.(Ferguson 1961) The four toes on the front legs and five on the back are extremely long. The adult tail is laterally flattened, metamorphosed from the larval stage of a fin. True teeth form a row across the roof of the mouth. In the larval stage, salamanders resemble the adults except that they have caudal fins, four external gill slits on either side of the head, and are a mottled, greenish color.(Duellman and Trueb 1986 Westphal 1996)

Other Physical Features: ectothermic ; bilateral symmetry

The reproductive behavior of Ambystoma macrodactylum croceum is highly unique. After a period of estivation, the salamanders travel great distances to their original breeding site. The males stay for approximately one month, while the females stay for only two weeks. The males spend this time competing with each other for resources in order to increase their fitness, (strength and virility). This increases the brightness of the yellow-orange markings, ultimately augmenting mate sexual preference. In the final courtship ritual, the male nudges the female, and if she is receptive, the male then places his chin on the female's head, rubbing his chin gland in a display of preference. The male then moves away, and the female follows snout-to-tail. The male deposits a mushroom-shaped spermatophore (gelatinous blob of sperm) at the bottom of the lake (pond, or slow-moving stream) for the female. She later takes the spermatophore into her "vent" to fertilize the eggs internally. Approximately 200-400 eggs are laid on a submerged vegetative stalk, and hatch 2-3 weeks later.(Hukill 1997) These jelly-encased eggs are the largest eggs of all salamanders in the area.(Westphal 1996) Larvae live in the pond until about March, when their tails will lose their fin, toes lengthen, and the gills disappear. Sexual maturity is reached at 3-4 years.(U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1986)

Key Reproductive Features: gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate)

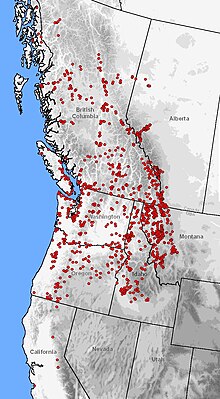

Ambystoma macrodactylum, or long-toed salamander, is a common amphibian in the family Ambystomatidae, or mole salamanders. Its native range extends from southeastern Alaska through British Columbia, Washington, and much of Oregon to northern California and from the Pacific coast eastward to northern Idaho, western Montana, and southwestern Alberta (Bull 2005).Long-toed salamanders are extremely adaptable amphibians, but they prefer to live in moist environments near ponds or lakes. They are most identifiable by a long greenish-yellow dorsal stripe, with the rest of their backs being black and their undersides dark brown with white flecks. Adults are about three to four inches long and quite slender. Their name comes from the slightly longer fourth toe on their hind feet (Rockney and Wu 2015).

Long-toed salamanders are the earliest breeding amphibians in their range. The timing differs depending on elevation, with those at lower elevations beginning in late fall and winter and those in alpine habitats waiting until summer (Pilliod and Fronzuto 2016). They are considered opportunistic breeders, meaning that they will lay eggs in all sorts of places, in the hope of at least some surviving. Once the eggs hatch, the aquatic larval stage begins, which can last from 1 to 3 years. The larvae feed on aquatic insects and crustaceans. They eventually lose their gills, produce digits, and metamorphose into terrestrial juveniles. The juvenile and adult salamanders stay within a small range of the pond or body of water where they were born, which will become their breeding grounds when they mature. Adult long-toed salamanders feed on arthropods, mollusks and annelids. They can live up to 7 years (Pilliod and Fronzuto 2016).

Ambystoma macrodactylum probably hibernate during winter, particularly at higher elevations, although adults can remain active all year long in lowland areas (Stebbins 2003). Adults hibernate underground, whereas the larvae can hide under logs and on the underside of leaves or sticks in a pond until it becomes warm enough for them to emerge. If and when they hibernate, they usually do so in groups and survive off of stored protein in their bodies, for months if needed. In general, they lead a very secretive life to avoid encountering predators (Pilliod and Fronzuto 2016). When they are threatened by predators, they coil their bodies or lash their tails, produce secretions from their skin, and can vocalize to either scare away the predator or warn other salamanders of danger. Because they absorb water and oxygen through their skin, they are very sensitive to the conditions of their habitats. This makes them good indicators of the health of the environment. They aren’t considered to be endangered, although they are threatened in certain regions.

No entry

FIRE REGIMES : Find fire regime information for the plant communities in which this species may occur by entering the species name in the FEIS home page under "Find FIRE REGIMES".

The long-toed salamander (Ambystoma macrodactylum) is a mole salamander in the family Ambystomatidae.[2] This species, typically 4.1–8.9 cm (1.6–3.5 in) long when mature, is characterized by its mottled black, brown, and yellow pigmentation, and its long outer fourth toe on the hind limbs. Analysis of fossil records, genetics, and biogeography suggest A. macrodactylum and A. laterale are descended from a common ancestor that gained access to the western Cordillera with the loss of the mid-continental seaway toward the Paleocene.

The distribution of the long-toed salamander is primarily in the Pacific Northwest, with an altitudinal range of up to 2,800 m (9,200 ft). It lives in a variety of habitats, including temperate rainforests, coniferous forests, montane riparian zones, sagebrush plains, red fir forests, semiarid sagebrush, cheatgrass plains, and alpine meadows along the rocky shores of mountain lakes. It lives in slow-moving streams, ponds, and lakes during its aquatic breeding phase. The long-toed salamander hibernates during the cold winter months, surviving on energy reserves stored in the skin and tail.

The five subspecies have different genetic and ecological histories, phenotypically expressed in a range of color and skin patterns. Although the long-toed salamander is classified as a species of Least Concern by the IUCN, many forms of land development threaten and negatively affect the salamander's habitat.

Ambystoma macrodactylum is a member of the Ambystomatidae, also known as the mole salamanders. The Ambystomatidae originated approximately 81 million years ago (late Cretaceous) from its sister taxon Dicamptodontidae.[3][4][5] The Ambystomatidae are also members of suborder Salamandroidea, which includes all the salamanders capable of internal fertilization.[6] The sister species to A. macrodactylum is A. laterale, distributed in eastern North America. However, the species-level phylogeny for Ambystomatidae is tentative and in need of further testing.[7]

The ancestral origins for this species stem from eastern North America, where species richness of ambystomatids are highest.[8][9] The following biogeographic interpretation on the origins of A. macrodactylum into western North America is based on a descriptive account of fossils, genetics, and biogeography.[10][11] The long-toed salamander's closest living sister species is A. laterale, a native to northeastern North America.[4][9] Ambystomatidae was isolated to the southeast of the mid-Continental or Western Interior Seaway during the Cretaceous (~145.5–66 Ma).[9][12] While three other species of the Ambystomatidae (A. tigrinum, A. californiense, and A. gracile) have overlapping ranges in western North America, the long-toed salamander's closest living sister species is A. laterale, a native to northeastern North America.[4][9] It has been suggested that A. macrodactylum speciated from A. laterale after the Paleocene (~66–55.8 Ma) with the loss of the Western Interior Seaway opening an access route for a common ancestor into the Western Cordillera.[11] Once situated in the montane regions of western North America, species had to contend with a dynamic spatial and compositional ecology responding to the changes in altitude, as mountains grew and the climate changed. For example, the Pacific Northwest became cooler in the Paleocene, paving the way for temperate forest to replace the warmer tropical forest of the Cretaceous.[13] A scenario for the splitting of A. macrodacylum and other western temperate species from their eastern counterparts involves Rocky Mountain uplift in the late Oligocene into the Miocene. The orogeny created a climatic barrier by removing moisture from the westerly air stream and dried the midcontinental area, from southern Alberta to the Gulf of Mexico.[10][14]

Ancestors of contemporary salamanders were likely able to disperse and migrate into habitats of the Rocky Mountains and surrounding areas by the Eocene. Mesic forests were established in western North America by the mid Eocene and attained their contemporary range distributions by the early Pliocene. The temperate forest valleys and montane environments of these time periods (Paleogene to Neogene) would have provided the physiographic and ecological features supporting analogs of contemporary Ambystoma macrodactylum habitats.[10][11][15][16] The Cascade Range rose during the mid Pliocene and created a rain shadow effect causing the xerification of the Columbia Basin and also altered ranges of temperate mesic ecosystems at higher elevations. The rise of the Cascades causing the xerification of the Columbia Basin is a major biogeographic feature of western North America that divided many species, including A. macrodactylum, into coastal and inland lineages.[11][14][16][17]

There are five subspecies of long-toed salamander.[18] The subspecies are discerned by their geographic location and patterns in their dorsal stripe;[19] Denzel Ferguson gives a biogeographic account of skin patterns, morphology; based on this analysis, he introduced two new subspecies: A. macrodactylum columbianum and A. m. sigillatum.[18] The ranges of subspecies are illustrated in Robert Stebbin's amphibian field guides.[19]

Summary of distinguishing skin patterns and morphological features for the subspecies include:[18][21]

Mitochondrial DNA analysis[11] identifies somewhat different ranges for the subspecies lineages.[11] The genetic analysis, for example, identifies an additional pattern of deep divergence in the eastern part of the range. The spatial distribution of populations and genetics of this species links spatially and historically through the interconnecting mountain and temperate valley systems of western North America.[11][22] The breeding fidelity of long-toed salamanders (philopatry) and other migratory behaviours reduce rates of dispersal among regions, such as within mountain basins. This aspect of their behavior restricts gene flow and increases the degree and rates of genetic differentiation. Genetic differentiation among regions is higher in the long-toed salamander than measured in most other vertebrate groups.[23] Natural breaks in the range of dispersal and migration occur where ecosystems grade into drier xeric low-lands (such as prairie climates) and at frozen or harsher terrain at high elevation extremes (2,200 meters (7,200 ft)).[24]

Thompson and Russell found another evolutionary lineage that originates in a glacially restricted area of the Salmon River Mountains, Idaho.[11] With the arrival of the Holocene interglacial, approximately 10,000 years ago, the Pleistocene glaciers receded and opened a migratory path linking these southern populations to northern areas where they currently overlap with A. m. krausei and co-migrated north into the Peace River (Canada) Valley.[11] Ferguson also noted an intergradation in the same geographic area, but between the morphological subspecies A. m. columbianum and A. m. krausei that run parallel to the Bitterroot and Selkirk ranges.[18] Thompson and Russell suggest that this contact zone is between two different subspecies lineages because the A. m. columbianum lineage is geographically isolated and restricted to the central Oregon Mountains.[11]

The body of the long-toed salamander is dusky black with a dorsal stripe of tan, yellow, or olive-green. This stripe can also be broken up into a series of spots. The sides of the body can have fine white or pale blue flecks. The belly is dark-brown or sooty in color with white flecks. Root tubercles are present, but they are not quite as developed as other species, such as the tiger salamander.[19]

The eggs of this species look similar to those of the related northwestern salamander (A. gracile) and tiger salamander (A. tigrinum).[26] Like many amphibians, the eggs of the long-toed salamander are surrounded by a gelatinous capsule. This capsule is transparent, making the embryo visible during development.[19] Unlike A. gracile eggs, there are no visible signs of green algae, which makes egg jellies green in color. When in its egg, the long-toed salamander embryo is darker on top and whiter below compared to a tiger salamander embryo that is light brown to grey above and cream-colored on the bottom. The eggs are about 2 mm (0.08 in) or greater in diameter with a wide outer jelly layer.[26][27] Prior to hatching—both in the egg and as newborn larvae—they have balancers, which are thin skin protrusions sticking out the sides and supporting the head. The balancers eventually fall off and their external gills grow larger.[28] Once the balancers are lost the larvae are distinguished by the sharply pointed flaring of the gills. As the larvae mature and metamorphose, their limbs with digits become visible and the gills are resorbed.[26][28]

The skin of a larva is mottled with black, brown, and yellow pigmentation. Skin color changes as the larvae develop and pigment cells migrate and concentrate in different regions of the body. The pigment cells, called chromatophores, are derived from the neural crest. The three types of pigment chromatophores in salamanders include yellow xanthophores, black melanophores, and silvery iridiophores (or guanophores).[29][30] As the larvae mature, the melanophores concentrate along the body and provide the darker background. The yellow xanthophores arrange along the spine and on top of the limbs. The rest of the body is flecked with reflective iridiophores along the sides and underneath.[29][18]

As larvae metamorphose, they develop digits from their limb bud protrusions. A fully metamorphosed long-toed salamander has four digits on the front limbs and five digits on the rear limbs.[31] Its head is longer than it is wide, and the long outer fourth toe on the hind limb of mature larvae and adults distinguishes this species from others and is also the etymological origin of its specific epithet: macrodactylum (Greek makros = long and daktylos = toe).[32] The adult skin has a dark brown, dark grey, to black background with a yellow, green, or dull red blotchy stripe with dots and spots along the sides. Underneath the limbs, head, and body the salamander is white, pinkish, to brown with larger flecks of white and smaller flecks of yellow. Adults are typically 3.8–7.6 cm (1.5–3.0 in) long.[26][20]

The long-toed salamander is an ecologically versatile species living in a variety of habitats, ranging from temperate rainforests, coniferous forests, montane riparian, sagebrush plains, red fir forest, semiarid sagebrush, cheatgrass plains, to alpine meadows along the rocky shores of mountain lakes.[19][18][25] Adults can be located in forested understory, hiding under coarse woody debris, rocks, and in small mammal burrows. During the spring breeding season, adults can be found under debris or in the shoreline shallows of rivers, streams, lakes, and ponds. Ephemeral waters are often frequented.[19]

This species is one of the most widely distributed salamanders in North America, second only to the tiger salamander. Its altitudinal range runs from sea level up to 2,800 meters (9,200 ft), spanning a wide variety of vegetational zones.[19][18][33][34][35] The range includes isolated endemic populations in Monterey Bay and Santa Cruz, California.[36] The distribution reconnects in northeastern Sierra Nevada running continuously along the Pacific Coast to Juneau, Alaska, with populations dotted along the Taku and Stikine River valleys. From the Pacific coast, the range extends longitudinally to the eastern foothills of the Rocky Mountains in Montana and Alberta.[37][21][38]

Like all amphibians, the life of a long-toed salamander begins as an egg. In the northern extent of its range, the eggs are laid in lumpy masses along grass, sticks, rocks, or the mucky substrate of a calm pond.[39] The number of eggs in a single mass ranges in size, possibly up to 110 eggs per cluster.[40] Females invest a significant amount of resources into egg production, with the ovaries accounting for over 50% of the body mass in the pre-breeding season. A maximum of 264 eggs have been found in a single female—a large number considering each egg is approximately 0.5 millimeters (0.02 in) in diameter.[41] The egg mass is held together by a gelatinous outer layer protecting the outer capsule of individual eggs.[42] The eggs are sometimes laid singly, especially in warmer climates south of the Canada and US border. The egg jellies contribute a yearly supply of biological material that supports the chemistry and nutrient dynamics of shallow-water aquatic ecosystems and adjacent forest ecosystems.[43] The eggs also provide habitat for water molds, also known as oomycetes.[44]

Larvae hatch from their egg casing in two to six weeks.[39] They are born carnivores, feeding instinctively on small invertebrates that move in their field of vision. Food items include small aquatic crustaceans (cladocerans, copepods and ostracods), aquatic dipterans and tadpoles.[45] As they develop, they naturally feed upon larger prey. To increase their chances for survival, some individuals grow bigger heads and become cannibals, and feed upon their own brood mates.[46]

After the larvae grow and mature, for at least one season (the larval period lasts about four months on the Pacific coast),[37] they absorb their gills and metamorphose into terrestrial juveniles that roam the forest undergrowth. Metamorphosis has been reported as early as July at sea level,[47] for A. m. croceum in October to November and even January.[20] At higher elevations the larvae may overwinter, develop, and grow for an extra season before metamorphosing.[48] In lakes at higher elevations, the larvae can reach sizes of 47 millimeters (1.9 in) snout to vent length (SVL) at metamorphosis, but at lower elevations they develop faster and metamorphose when they reach 35–40 millimeters (1.4–1.6 in) SVL.[23]

As adults, long-toed salamanders often go unnoticed because they live a subterranean lifestyle digging, migrating, and feeding on the invertebrates in forest soils, decaying logs, small rodent burrows or rock fissures. The adult diet consists of insects, tadpoles, worms, beetles and small fish. Salamanders are preyed upon by garter snakes, small mammals, birds, and fish.[49] An adult may live 6–10 years, with the largest individuals weighing approximately 7.5 grams (0.26 oz), snout to vent lengths reaching 8 cm (3.1 in), and total lengths reaching 14 cm (5.5 in).[50][51]

The life history of the long-toed salamander varies greatly with elevation and climate. Seasonal dates of migration to and from the breeding ponds can be correlated with bouts of sustained rainfall, ice thaw, or snow melt sufficient to replenish the (often) seasonal ponds. Eggs may be spawned at low elevations as early as mid-February in southern Oregon,[52] from early January to July in northwestern Washington,[53] from January to March in southeastern Washington,[54] and from mid-April to early May in Waterton Lakes National Park, Alberta.[55] The timing of breeding can be highly variable; of notable mention, several egg masses in early stages of development were found on July 8, 1999 along the British Columbia provincial border outside Jasper, Alberta.[10] Adults migrate seasonally to return to their natal breeding ponds, with males arriving earlier and staying longer than females, and some individuals have been seen migrating along snow banks on warm spring days.[56] Gender differences (or sexual dimorphism) in this species are only apparent during the breeding season, when mature males display an enlarged or bulbous vent area.

The time of breeding depends on the elevation and latitude of the salamander's habitat. Generally, the lower-elevation salamanders breed in the fall, winter, and early spring. Higher-elevation salamanders breed in spring and early summer. In the higher climates especially, salamanders will enter ponds and lakes that still have ice floating.[19]

Adults aggregate in large numbers (>20 individuals) under rocks and logs along the immediate edge of the breeding sites and breed explosively over a few days.[20] Suitable breeding sites include small fish-free ponds, marshes, shallow lakes and other still-water wetlands.[57] Like other ambystomatid salamanders, they have evolved a characteristic courtship dance where they rub bodies and release pheromones from their chin gland prior to assuming a copulatory mating position. Once in position, the male deposits a spermatophore, which is a gooey stalk tipped with a packet of sperm, and walks the female forward to be inseminated. Males may mate more than once and may deposit as many as 15 spermatophores over the course of a five-hour period.[20][39] The courtship dance for the long-toed salamander is similar to other species of Ambystoma and very similar to A. jeffersonianum.[58][59] In the long-toed salamander, there is no rubbing or head-butting; the males directly approach females and grab on, while the females try to rapidly swim away.[59] The males clasp the female from behind the forelimbs and shake, a behavior called amplexus. Males sometimes clasp other amphibian species during breeding and shake them as well.[53] The male only grabs with the front limbs and never uses his hind limbs during the courtship dance as he rubs his chin side to side pressing down on the female's head. The female struggles but later becomes subdued. Males increase the tempo and motions, rubbing over the female's nostrils, sides, and sometimes the vent. When the female becomes quite docile the male moves forward with his tail positioned over her head, raised, and waving at the tip. If the female accepts the males courtship, the male directs her snout toward his vent region while both move forward stiffly with pelvic undulations. As the female follows, the male stops and deposits a spermatophore, and the female will move forward with the male to raise her tail and receive the sperm packet. The full courtship dance is rarely accomplished in the first attempt.[59] Females deposit their eggs a few days after mating.[20]

In some lowland areas the adult salamanders will remain active all winter long, excluding cold spells. However, during the cold winter months in the northern parts of its range, the long-toed salamander burrows below the frost-line in a coarse substrate to hibernate in clusters of 8–14 individuals.[40][60] While hibernating, it survives on protein energy reserves that are stored in its skin and along its tail.[61] These proteins serve a secondary function as part of a mixture or concoction of skin secretions that is used for defense.[62] When threatened, the long-toed salamander will wave its tail and secrete an adhesive white milky substance that is noxious and likely poisonous.[55][63] The color of its skin can serve as a warning to predators (aposematism) that it will taste bad.[62] Its skin colors and patterns are diverse, ranging from a dark black to reddish brown background that is spotted or blotched by a pale-reddish-brown, pale-green, to a bright yellow stripe.[37][39] An adult may also drop part of its tail and slink away while the tail bit acts as a squirmy decoy; this is called autotomy.[64] The regeneration and regrowth of the tail is one example of the developmental physiology of amphibians that is of great interest to the medical profession.[65]

While the long-toed salamander is classified as least concern by the IUCN,[1] many forms of land development negatively affect the salamander's habitat and have put new perspectives and priorities into its conservation biology. Conservation priorities focus at the population level of diversity, which is declining at rates ten times that of species extinction.[66][67][68][69] Population level diversity is what provides ecosystem services,[70] such as the keystone role that salamanders play in the soil ecosystems, including the nutrient cycling that supports wetland and forested ecosystems.[71]

Two life-history features of amphibians are often cited as a reason why amphibians are good indicators of environmental health or 'canaries in the coal mine'. Like all amphibians, the long-toed salamander has both an aquatic and terrestrial life transition and semipermeable skin. Since they serve different ecological functions in the water than they do in land, the loss of one amphibian species is equivalent to the loss of two ecological species.[72] The second notion is that amphibians, such as long-toed salamanders,[73] are more susceptible to the absorption of pollutants because they naturally absorb water and oxygen through their skin. The validity of this special sensitivity to environmental pollutants, however, has been called into question.[74] The problem is more complex, because not all amphibians are equally susceptible to environmental damage because there is such a diverse array of life histories among species.[75]

Long-toed salamander populations are threatened by fragmentation, introduced species, and UV radiation. Forestry, roads, and other land developments have altered the environments that amphibians migrate to, and have increased mortality.[76] Places such as Waterton Lakes National Park have installed a road tunnel underpass to allow safe passage and to sustain the migration ecology of the species.[2] The distribution of the long-toed salamander overlaps extensively with the forestry industry, a dominant resource supporting the economy of British Columbia and the western United States. Long-toed salamanders will alter migration behaviour and are affected negatively by forestry practices not offering sizable management buffers and protections for the smaller wetlands where salamanders breed.[77][78] Populations near the Peace River Valley, Alberta, have been lost to the clearing and draining of wetlands for agriculture.[79] Trout introduced for the sport fisheries into once fishless lakes are also destroying long-toed salamander populations.[80] Introduced goldfish prey on the eggs and larvae of long-toed salamanders.[81] Increased exposure to UVB radiation is another factor being implicated in the global decline of amphibians and the long-toed salamander is also susceptible to this threat, which increases the incidence of deformities and reduces their survival and growth rates.[82][83][84]

The subspecies Ambystoma macrodactylum croceum (Santa Cruz Long-toed Salamander) is of particular concern and it was afforded protections in 1967 under the US Endangered Species Act.[85] This subspecies lives in a narrow range of habitat in Santa Cruz County and Monterey County, California. Prior to receiving protections, some few remaining populations were threatened by development. The subspecies is ecologically unique, having unique and irregular skin patterns on its back, a unique moisture tolerance, and it is also an endemic that is geographically isolated from the rest of the species range.[18][86][87][88] Other subspecies include A. m. columbianum, A. m. krausei, A. m. macrodactylum and A. m. sigillatum.[21]

The long-toed salamander (Ambystoma macrodactylum) is a mole salamander in the family Ambystomatidae. This species, typically 4.1–8.9 cm (1.6–3.5 in) long when mature, is characterized by its mottled black, brown, and yellow pigmentation, and its long outer fourth toe on the hind limbs. Analysis of fossil records, genetics, and biogeography suggest A. macrodactylum and A. laterale are descended from a common ancestor that gained access to the western Cordillera with the loss of the mid-continental seaway toward the Paleocene.

The distribution of the long-toed salamander is primarily in the Pacific Northwest, with an altitudinal range of up to 2,800 m (9,200 ft). It lives in a variety of habitats, including temperate rainforests, coniferous forests, montane riparian zones, sagebrush plains, red fir forests, semiarid sagebrush, cheatgrass plains, and alpine meadows along the rocky shores of mountain lakes. It lives in slow-moving streams, ponds, and lakes during its aquatic breeding phase. The long-toed salamander hibernates during the cold winter months, surviving on energy reserves stored in the skin and tail.

The five subspecies have different genetic and ecological histories, phenotypically expressed in a range of color and skin patterns. Although the long-toed salamander is classified as a species of Least Concern by the IUCN, many forms of land development threaten and negatively affect the salamander's habitat.

Ambystoma macrodactylum es una especie de salamandra con dedos largos de la familia Ambystomatidae.[2] Esta especie, mide entre 4 y 9 cm de largo de adulta, se caracteriza por su pigmentación moteada de color negro, marrón y amarillo, y su cuarto dedo largo y externo en las extremidades posteriores. El análisis de los registros fósiles, la genética y la biogeografía sugieren que A. macrodactylum y A. laterale descienden de un antepasado común que obtuvo acceso a la Cordillera occidental con la pérdida de la vía marítima medio continental hacia el Paleoceno.

La salamandra de dedos largos se encuentra principalmente en el noroeste del Pacífico, con un rango altitudinal de hasta 2800 m. Vive en una variedad de hábitats, incluyendo bosques templados lluviosos, bosques de coníferas, zonas ribereñas montanas, llanuras de artemisa, bosques de abetos rojos, artemisa semiárida, llanuras de hierba de pasto y prados alpinos a lo largo de las costas rocosas de los lagos de montaña. Vive en arroyos, estanques y lagos de movimiento lento durante su fase de reproducción acuática. La salamandra de dedos largos hiberna durante los fríos meses de invierno, sobreviviendo en las reservas de energía almacenadas en la piel y la cola.

Las cinco subespecies tienen historias genéticas y ecológicas diferentes, expresadas fenotípicamente en una gama de colores y patrones de piel. Aunque la salamandra de dedos largos está clasificada como una especie de preocupación menor por la UICN, muchas formas de desarrollo de la Tierra amenazan y afectan negativamente el hábitat de la salamandra.

El cuerpo de la salamandra de dedos largos es de color negro oscuro con una franja dorsal de color tostado, amarillo o verde oliva. Esta tira también se puede dividir en una serie de puntos. Los costados del cuerpo pueden tener finas manchas blancas o azul pálido. El vientre es de color marrón oscuro o hollín con manchas blancas. Los tubérculos de raíz están presentes, pero no están tan desarrollados como otras especies, como la salamandra tigre. [3]

Los huevos de esta especie se parecen a los de su parientes la salamandra del noroeste (A. gracile) y la salamandra tigre (A. tigrinum).[4] Al igual que en muchos anfibios, los huevos de la salamandra de dedos largos están rodeados por una cápsula gelatinosa. Esta cápsula es transparente, lo que hace que el embrión sea visible durante el desarrollo.[3] A diferencia de los huevos de A. gracile, no hay signos visibles de algas verdes, lo que hace que las gelatinas sean de color verde. Cuando está en su huevo, el embrión de salamandra de dedos largos es más oscuro en la parte superior y más blanco en la parte inferior en comparación con un embrión de salamandra tigre que es de color marrón claro a gris en la parte superior y de color crema en la parte inferior. Los huevos miden aproximadamente 2 mm o más de diámetro con una gruesa capa exterior de gelatina. [4][5] Antes de la eclosión, tanto en el huevo como en las larvas del recién nacido, tienen equilibradores, que son protuberancias finas de la piel que sobresalen por los lados y sostienen la cabeza. Los equilibradores eventualmente se caen y sus branquias externas se hacen más grandes.[6] Una vez que se pierden los equilibradores, las larvas se distinguen por la forma puntiaguda de las branquias. A medida que las larvas maduran y se metamorfosean, sus miembros con dígitos se vuelven visibles y las branquias se reabsorben.[4][6]

La piel de la larva está moteada con pigmentación negra, marrón y amarilla. El color de la piel cambia a medida que se desarrollan las larvas y las células pigmentarias migran y se concentran en diferentes partes del cuerpo. Las células pigmentarias, llamadas cromatóforos, se derivan de la cresta neural. Los tres tipos de cromatóforos pigmentarios en las salamandras incluyen xantóforos amarillos, melanóforos negros e iridióforos (o guanóforos) plateados.[7][8] A medida que las larvas maduran, los melanóforos se concentran a lo largo del cuerpo y proporcionan el fondo más oscuro. Los xantóforos amarillos se disponen a lo largo de la columna vertebral y en la parte superior de las extremidades. El resto del cuerpo está salpicado de iridióforos reflectantes a lo largo de los lados y debajo.[7][9]

A medida que las larvas se metamorfosean, desarrollan dígitos a partir de las protuberancias de las yemas de sus extremidades. Una salamandra de dedos largos completamente metamorfoseada tiene cuatro dígitos en las extremidades delanteras y cinco dígitos en las extremidades posteriores.[10] Su cabeza es más larga que ancha, y el cuarto dedo largo exterior de la extremidad posterior de las larvas maduras y los adultos distingue a esta especie de otras y también es el origen etimológico de su epíteto específico: macrodactylum (en griego macros = 'largos' y daktylos = 'dedo de la pata' ).[11] La piel adulta tiene un fondo marrón oscuro, gris oscuro a negro con una franja manchada amarilla, verde o roja opaca con puntos y manchas a lo largo de los lados. Debajo de las extremidades, la cabeza y el cuerpo, la salamandra es blanca, rosada a marrón con manchas más grandes de color blanco y manchas más pequeñas de color amarillo. [4][12] Los adultos miden de 4 a 8 cm de largo.

Ambystoma macrodactylum es una especie de salamandra con dedos largos de la familia Ambystomatidae. Esta especie, mide entre 4 y 9 cm de largo de adulta, se caracteriza por su pigmentación moteada de color negro, marrón y amarillo, y su cuarto dedo largo y externo en las extremidades posteriores. El análisis de los registros fósiles, la genética y la biogeografía sugieren que A. macrodactylum y A. laterale descienden de un antepasado común que obtuvo acceso a la Cordillera occidental con la pérdida de la vía marítima medio continental hacia el Paleoceno.

La salamandra de dedos largos se encuentra principalmente en el noroeste del Pacífico, con un rango altitudinal de hasta 2800 m. Vive en una variedad de hábitats, incluyendo bosques templados lluviosos, bosques de coníferas, zonas ribereñas montanas, llanuras de artemisa, bosques de abetos rojos, artemisa semiárida, llanuras de hierba de pasto y prados alpinos a lo largo de las costas rocosas de los lagos de montaña. Vive en arroyos, estanques y lagos de movimiento lento durante su fase de reproducción acuática. La salamandra de dedos largos hiberna durante los fríos meses de invierno, sobreviviendo en las reservas de energía almacenadas en la piel y la cola.

Las cinco subespecies tienen historias genéticas y ecológicas diferentes, expresadas fenotípicamente en una gama de colores y patrones de piel. Aunque la salamandra de dedos largos está clasificada como una especie de preocupación menor por la UICN, muchas formas de desarrollo de la Tierra amenazan y afectan negativamente el hábitat de la salamandra.

Ambystoma macrodactylum Ambystoma generoko animalia da. Anfibioen barruko Ambystomatidae familian sailkatuta dago, Caudata ordenan.

Ambystoma macrodactylum Ambystoma generoko animalia da. Anfibioen barruko Ambystomatidae familian sailkatuta dago, Caudata ordenan.

Pitkävarvassalamanteri (Ambystoma macrodactylum) on Ambystoma-sukuun kuuluva pyrstösammakkolaji. Alalaji santacruzinpitkävarvassalamanteri (A. m. croceum) on uhanalainen. Muita alalajeja ovat lännenpitkävarvassalamanteri (A. m. macrodactylum), idänpitkävarvassalamanteri (A. m. columbianum), pohjoinenpitkävarvassalamanteri (A. m. krausei) ja etelänpitkävarvassalamanteri (A. m. sigillatum).

Pitkävarvassalamanteri on pieni, 10–17 senttiä pitkä. Nimensä mukaisesti sillä on pitkät varpaat. Väriltään se on tummanharmaa tai musta. Sillä on selässä juova, joka on keltainen, vihreä tai ruskea. Kyljissä sillä on valkoisia laikkuja.

Pitkävarvassalamanteria tavataan Yhdysvaltain koillisosissa ja Kanadassa. Sitä esiintyy metsissä ja niityillä, erityisesti paikoissa, missä on marunakasveja.

Pitkävarvassalamanteri tulee sukukypsäksi 1–3-vuotiaana.[3] Muniminen tapahtuu keväällä kasvillisuuden sekaan. Lisääntymispaikkoja ovat järvet, lammet ja joet.[4]

Pitkävarvassalamanteri (Ambystoma macrodactylum) on Ambystoma-sukuun kuuluva pyrstösammakkolaji. Alalaji santacruzinpitkävarvassalamanteri (A. m. croceum) on uhanalainen. Muita alalajeja ovat lännenpitkävarvassalamanteri (A. m. macrodactylum), idänpitkävarvassalamanteri (A. m. columbianum), pohjoinenpitkävarvassalamanteri (A. m. krausei) ja etelänpitkävarvassalamanteri (A. m. sigillatum).

Ambystoma macrodactylum, la Salamandre à longs doigts, est une espèce d'urodèles de la famille des Ambystomatidae[1].

L'analyse des fossiles, la génétique et la biogéographie suggèrent que Ambystoma macrodactylum et Ambystoma laterale descendent d'un ancêtre commun qui se sont séparées au Paléocène. Bien que la salamandre à longs doigts est classé comme une espèce de Préoccupation mineure par l'IUCN, de nombreuses formes d'aménagement du territoire et menacent d'affecter l'habitat de la salamandre.

Cette espèce se rencontre jusqu'à 3 050 m d'altitude[1] :

La salamandre à longs doigts est une espèce écologiquement polyvalentes qui vive dans des habitats variés, allant des forêts pluviales tempérées, les forêts de conifères, les zones ripariennes de montagne, les plaines d'armoise, les forêts de sapin rouge, les zones semi-arides, des plaines de Brome des toits, aux prairies alpines le long des côtes rocheuses des lacs de montagne[2].

Les adultes peuvent être observés dans le sous-étage forestier, se cachant sous des débris grossiers, les roches et dans les terriers de petits mammifères. Durant la reproduction de printemps, Ils se trouvent sous les débris ou les eaux peu profondes du littoral des rivières, des ruisseaux, des lacs et des étangs. Les mares éphémères sont souvent fréquentées[2].

Ambystoma macrodactylum mesure de 41 à 89 mm. Le corps est noir foncé avec une rayure dorsale beige, jaune ou vert olive. Cette bande peut également être décomposé en une série de taches. Le côté du corps peut avoir de fines mouchetures blanches ou jaune pâle bleu. Le ventre est brun foncé ou noir de suie en couleur avec des taches blanches. Des tubercules racinaires sont présents, mais ils ne sont pas aussi développées que d'autres espèces telles que la salamandre tigrée[2].

Elle se distingue par la longueur de son quatrième doigt des membres postérieurs.

Les salamandres à longs doigts hibernent pendant les mois froids de l'hiver, survivant sur les réserves énergétiques de protéines stockée dans la peau et la queue.

Jusqu'à cinq sous-espèces sont définies génétiquement et écologiquement selon une gamme de couleurs et de dessin sur la peau.

Elles mangent une grande variété d'invertébrés, y compris les limaces, les vers et les insectes. Les petites larves se nourrissent de crustacés minuscules d'eau du zooplancton, mais à mesure qu'elles grandissent, elles se nourrissent d'invertébrés, de têtards de grenouilles et souvent d'autres larves de salamandre.

Le moment de la reproduction dépend de l'altitude et la latitude. Les adultes se rassemblent en masse, plus de 20 individus, sous les rochers et aux abords immédiat des sites de reproduction[3]. Les sites de reproduction appropriés sont les petits étangs sans poissons, les marais, les lacs peu profonds et d'autres eaux des zones humides[4]. Comme les autres salamandres, ils ont développé une danse de séduction caractéristique où ils se frottent et libèrent des phéromones avant de prendre une position d'accouplement.

Les œufs de cette espèce ressemblent à ceux de la salamandre foncée (Ambystoma gracile) et la salamandre tigrée (Ambystoma tigrinum)[5]. À l'instar de nombreux amphibiens, les œufs de la salamandre à longs doigts sont entourés d'une capsule gélatineuse . Cette capsule est transparente, ce qui rend visible l'embryon au cours du développement[2]. À la différence des œufs de Ambystoma gracile, il n'y a pas de signes visibles d'algues vertes, ce qui rend œufs de couleur verte. Ils mesurent environ 2 mm ou plus de diamètre avec une couche de gelée de gamme extra-atmosphérique[6]. Avant l'éclosion, ils ont des saillies cutanées minces collés sur les côtés et supportant la tête. Le équilibreurs finissent par tomber et leurs branchies externes grandir[7]. Une fois que les équilibreurs sont perdus, les larves se distinguent par le brûlage à la torche pointue des branchies. Quand les larves matures se métamorphosent, leurs membres deviennent visibles et les branchies sont absorbées.

Ambystoma macrodactylum, la Salamandre à longs doigts, est une espèce d'urodèles de la famille des Ambystomatidae.

L'analyse des fossiles, la génétique et la biogéographie suggèrent que Ambystoma macrodactylum et Ambystoma laterale descendent d'un ancêtre commun qui se sont séparées au Paléocène. Bien que la salamandre à longs doigts est classé comme une espèce de Préoccupation mineure par l'IUCN, de nombreuses formes d'aménagement du territoire et menacent d'affecter l'habitat de la salamandre.

De langteensalamander[2] (Ambystoma macrodactylum) is een salamander uit de familie molsalamanders (Ambystomatidae). De soort werd voor het eerst wetenschappelijk beschreven door Spencer Fullerton Baird in 1849. Later werd de wetenschappelijke naam Amblystoma macrodactylum gebruikt.[3]

De Nederlandstalige naam komt ook terug in de wetenschappelijke soortnaam; macro betekent groot en dactylum betekent teen.[bron?] Alle tenen zijn wat langer dan bij verwante soorten, echter vooral de vierde teen van de achterpoten is sterk verlengd. De kleur is zwart, meestal zonder flanktekening en duidelijk zichtbare gifklieren (parotoïden) en ribben (costale groeven). Kenmerkend is de heldergroene tot -gele brede rugstreep op het midden van de rug die soms bestaat uit een vlekkenrij. De lichaamslengte varieert van 10 tot 17 centimeter. Op het lichaam zijn 12 toit 13 costale groeven aanwezig.

De langteensalamander komt voor van zuidoostelijk Canada tot Californië in de Verenigde Staten.[4] De habitat bestaat uit zowel drogere graslanden als hoger gelegen bergmeertjes en de soort kan in vele biotopen leven, maar blijft bij water in de buurt. Zelfs tot 3000 meter boven zeeniveau kan de salamander worden aangetroffen, waar het voor veel andere soorten te koel en te droog is. Overdag zit het dier meestal verstopt onder stenen of bladeren en komt pas tijdens de schemering tevoorschijn om te jagen op insecten en andere kleine ongewervelden.

De paartijd begint vroeg in het jaar en er worden zelfs al eitjes afgezet als het water nog half bevroren is. De salamanders komen naar de afzetplaats toe als het regent en meestal 's nachts en het aantal eitjes varieert sterk; van 80 tot wel 400. De eitjes worden zowel aan waterplanten vastgemaakt als op de bodem afgezet, en de larven eten kleine micro-organismen, algen en ook elkaar.

De langteensalamander (Ambystoma macrodactylum) is een salamander uit de familie molsalamanders (Ambystomatidae). De soort werd voor het eerst wetenschappelijk beschreven door Spencer Fullerton Baird in 1849. Later werd de wetenschappelijke naam Amblystoma macrodactylum gebruikt.

Ambystoma długopalca (Ambystoma macrodactylum) – gatunek płaza ogoniastego z rodziny Ambystomatidae. Osobnik dorosły mierzy od 3,8 do 7,6 cm. Cechuje się cętkowaną, czarną, brązową i żółtą pigmentacją. Analizy paleontologiczne, genetyczne i biogeograficzne sugerują, że powstała około 81 milionów lat temu we wschodniej Ameryce Północnej.

Pierwotny zasięg występowania zwierzęcia obejmuje północny zachód kontynentu, nie wychodząc poza wysokość 2800 metrów nad poziomem morza. Zamieszkuje ono różnorodne środowiska, jak lasy deszczowe klimatu umiarkowanego, lasy iglaste, wybrzeża górskich zbiorników wodnych, równiny porośnięte bylicami, lasy jodłowe (z Abies magnifica), równiny porośnięte trawą Bromus tectorum oraz górskie łąki na skalistych brzegach górskich jezior. W czasie sezonu rozrodczego żyje w strumieniach o wolnym nurcie, stawach i jeziorach. Hibernuje przez zimne miesiące, które przeżywa dzięki zapasom białkowym i energetycznym zmagazynowanym w skórze i ogonie.

Wyróżnia się pięć podgatunków posiadających odrębności genetyczne i ekologiczne, a także fenotypowe (inny zakres barwy i odmienne wzory na skórze). Choć IUCN nadaje zwierzęciu status najmniejszej troski (LC), występuje wiele czynników negatywnie wpływających na środowisko jego życia.

Ambystoma macrodactylum należy do rodziny ambystomowatych, które pojawiły się około 80 milionów lat temu (kreda późna). Wymienia się je nieraz jako takson siostrzany w stosunku do rodziny Dicamptodontidae[3][4][5], zwykle nieuznawanej. Przodkowie tych grup pochodzili ze wschodniej Ameryki Północnej, gdzie występuje największe bogactwo gatunkowe ambystomowatych[6][7] Następująca interpretacja biogeograficzna traktująca o pochodzeniu ambystomy długopalcej z zachodu kontynentu północnoamerykańskiego bazuje na opisach skamieniałości, badaniach genetycznych i biogeograficznych[8].

Istniejące w kredzie Morze Środkowego Zachodu przyczyniło się do izolacji ambystomowatych na południowym wschodzie kontynentu[7][9]. O ile trzy gatunki (ambystoma tygrysia – Ambystoma tigrinum, Ambystoma californiense, Ambystoma gracile) posiadały nakładające się na siebie zasięgi na zachodzie Ameryki Północnej, najbliższy takson siostrzany opisywanego tu gatunku (Ambystoma laterale), zamieszkiwał północny wschód kontynentu[4][7]. Zasugerowano, że ambystoma długopalca wyodrębniła się z niego po paleocenie, kiedy to zaniknięcie Morza Środkowego Zachodu otworzyło drogę do północnoamerykańskiej Kordyliery Zachodniej[8]. Klimat Wybrzeża Północno-Zachodniego ochłodził się w pierwszej epoce kenozoiku, otwierając drogę lasom klimatu umiarkowanego, które wyparły ciepłolubne lasy tropikalne okresu kredowego[10]. Ogoniaste prawdopodobnie bardzo łatwo migrowały i rozprzestrzeniały się w obrębie dolin Gór Skalistych, które w eocenie osiągnęły znaczną wysokość[8][11]. Inne gatunki także przemieszczały się wtedy wzdłuż linii brzegowej. W tym czasie wypiętrzały się Góry Kaskadowe, powodując powstanie cienia opadowego, który rozdrobnił las tropikalny, zmieniając go w typowy dla klimatu umiarkowanego[12]. Porośnięte nim doliny i wyższe piętra zapewniły siedliska analogiczne do współcześnie zajmowanych przez ambystomę długopalcą[8][13].

Ciemne ciało tego płaza posiada na grzbiecie prążek barwy opalonej, żółtej lub oliwkowozielonej. Czasem może się on przerywać, tworząc serię plamek. Boki mogą zdobić białe lub bladoniebieskie plamki. Brzuch jest ciemnobrązowy lub koloru sadzy. Na stopach widnieją guzki rozwinięte znacznie słabiej niż u innych gatunków, jak ambystoma tygrysia[14].

Należące do tego gatunku jajo przypomina spotykane u bliskich krewnych: Ambystoma gracile i ambystomy tygrysiej[15]. Jednakże w przeciwieństwie do A. gracile u ambystomy długopalcej nie zauważa się oznak zielenic, co czyni jajo żelowato zielonym. W obrębie jaja wierzch zarodka jest ciemniejszy niż spód. Dla porównania embrion ambystomy tygrysiej posiada na grzbiecie zabarwienie jasnobrązowe do szarego, kremowe zaś na spodzie. Jajo osiąga średnicę 2 mm lub większą z szeroką żelowatą warstwą zewnętrzną[15][16]. Zarówno w jaju przed wykluciem, jak i nowo narodzona larwa posiadają stabilizatory będące wypustkami sterczącymi po bokach i wspierającymi głowę. W końcu odpadają, a wtedy ma miejsce wzrost skrzeli zewnętrznych[17]. Utrata stabilizatorów uwidacznia się w płomiennych ostrych spiczastych zakończeniach na skrzelach. Gdy kijanki dojrzewają i stają się zdolne do przeobrażenia, ich kończyny wraz z palcami stają się zauważalne, skrzela natomiast ulegają resorpcji. Długie palce tylnych łap dojrzałej larwy odróżniają ten gatunek od innych[15][17].

Nakrapianą skórę kijanki zdobi czarna, brązowa i żółta pigmentacja. Kolor skóry zmienia się w trakcie rozwoju larwalnego, komórki barwnikowe, zwane chromatoforami, migrują i koncentrują się w różnych rejonach ciała. Pochodzą one z grzebieni nerwowych. U ogoniastych występują trzy typy chromatoforów: żółte ksantofory, czarne melanofory i srebrzyste iridiofory (lub guanofory)[18][19]. Gdy larwa dojrzewa, melanofory zbierają się wzdłuż ciała, zapewniając ciemne tło. Ksantofory grupują się wzdłuż kręgosłupa i szczytu kończyn. Resztę ciała pokrywa cętkowanie tworzone przez refleksyjne iridiofory po bokach ciała i na spodzie ciała[18][20].

Podczas metamorfozy palce rozwijają się z pączków na kończynach. W pełni przeobrażona ambystoma długopalca posiada cztery palce na przednich łapach, a na tylnych o jeden więcej[21]. Długość głowy przekracza jej szerokość. Zwraca uwagę długi drugi palec tylnych kończyn, od którego pochodzi nazwa naukowa (gr. makros = długi; gr. daktylos = palec)[22]. Na skórze dorosłego płaza na ciemnobrązowym, ciemnoszarym do czarnego tle widnieje żółty, zielony do matowo czerwonego plamkowany pasek z kropkami lub plamkami po bokach. Poniżej kończyn i głowy ciało ambystomy jest białe, różowawe do brązowego z większymi białymi plamkami i mniejszymi żółtymi[15][23]. Dorosłe osobniki osiągają zwykle 3,8-7,6 cm długości.

Opisywany tu gatunek należy do posiadających najszerszy zasięg występowania w Ameryce Północnej, w czym ustępuje jedynie ambystomie tygrysiej. Bytuje na wysokościach od poziomu morza do 2800 metrów. Zajmuje zróżnicowane strefy roślinne[20][24][25][26][27]. Obszar ten zawiera izolowane endemiczne populacje w Monterey Bay i Santa Cruz w Kalifornii[28]. Obejmuje tereny od północno-wschodniej Sierra Nevada w Kalifornii nieprzerwanie poprzez wybrzeże pacyficzne aż do Juneau na Alasce. Rozsiane populacje zamieszkują doliny rzek Taku i Stikine. Od wybrzeża Oceanu Spokojnego zasięg występowania przebiega południkowo do wschodnich podnóży Gór Skalistych w Montanie i Albercie[29][30][31].

Ambystoma długopalca zajmuje różnorodne środowiska: wilgotne lasy strefy umiarkowanej, lasy iglaste, obrzeża górskich zbiorników wodnych, równiny porośnięte byliną, lasy jodłowe (z Abies magnifica), równiny porośnięte trawą Bromus tectorum oraz górskie łąki na brzegach jezior[20][26][32]. Osobniki dorosłe, gdy żyją na lądzie, bytują w podszycie leśnym, ukrywając się wśród zwalonych pni, kamieni i w norach.

Ambystoma długopalca, jak i inne płazy, rozpoczyna swe życie jako jajo. W północnej części zasięgu występowania jaja składane są w grudkowatych masach wśród traw, patyków, kamieni lub na błotniste podłoże spokojnych stawów[33]. Liczba pojedynczo składanych jaj zmienia się, prawdopodobnie jeden klaster zawiera ich do 110[34]. Samice zużywają na ich produkcję znaczną ilość energii, a ich jajniki przed sezonem rozrodczym osiągnąć mogą ponad połowę masy ciała zwierzęcia. W obrębie pojedynczej ambystomy znaleziono rekordowo 264 jaja, przy czym pojedyncze osiąga 0,5 mm średnicy[35]. Skrzek trzyma razem żelatynowa warstwa zewnętrzna ochraniająca zewnętrzną osłonkę każdego z jaj[36]. Zdarza się, że jaja składane są pojedynczo. Ma to miejsce zwłaszcza w cieplejszym klimacie południa Kanady i amerykańskiej granicy. Pojedyncze jajo zawiera zapas materiału energetycznego wystarczającego na jeden rok. Stanowi on źródło pożywienia w ekosystemach płytkiej wody i przyległego lasu[37]. Skrzek zapewnia też odpowiednie środowisko dla lęgniowców[38], drobnych protistów zaliczanych niegdyś do grzybów.

Larwy zwane kijankami wykluwają się z jaja po upływie od dwóch do sześciu tygodni[33]. Od początku zaliczają się do mięsożerców, polując instynktownie na niewielkie bezkręgowce, które znajdą się w ich polu widzenia. Wymienia się tutaj niewielkie wodne skorupiaki (wioślarki, widłonogi i małżoraczki), wodne muchówki, ale też kijanki[39]. W miarę rozwoju spontanicznie przerzucają się na coraz większą zdobycz. By zwiększyć swe szanse przetrwania, niektóre osobniki rozwijają większe głowy i zostają kanibalami, spożywając osobniki z tego samego lęgu[40].

Wzrost i dojrzewanie kijanek trwa co najmniej jeden sezon (na wybrzeżu pacyficznym okres larwalny zabiera około czterech miesięcy)[41]. Ma wtedy miejsce absorpcja skrzeli i przeobrażenie w lądowe osobniki młodociane, które wędrują do podszytu lasu. Na poziomie morza metamorfozę obserwowano już w lipcu[42], z kolei podgatunek A. m. croceum przechodzi ją od października do listopada, a nawet i w styczniu[23]. Na większych wysokościach larwy mogą zimować, a dojrzewać i przeobrażać się dopiero w kolejnym sezonie[43]. W wysoko położonych jeziorach mogą one osiągać 47 mm długości od pyska do odbytu (SVL), podczas gdy na niższych wysokościach 35-40 mm[44].

Osobniki dorosłe ambystomy długopalcej nie rzucają się specjalnie w oczy z powodu swego podziemnego stylu życia obejmującego kopanie, migracje i pożywianie się bezkręgowcami na dnie lasu, w gnijących kłodach, jamach niewielkich gryzoni i szczelinach skalnych. Ich dieta składa się z owadów, kijanek, pierścienic, chrząszczy i małych ryb. Same z kolei padają ofiarami węży z rodzaju Thamnophis, niewielkich ssków i ryb[45]. Dorosłe dożyć mogą 6–10 lat, największe osiągają masę ciała 7,5 g i odległość od pyska do odbytu 8 cm, całkowitą 14 cm[46][47].

Życie tego gatunku zmienia się w dużym stopniu w zależności od wysokości i klimatu. Sezonowe daty migracji z i do zbiorników rozrodczych korelują z wybuchem opadów deszczu, roztopami lodu i śniegu, wystarczającymi dla powstania sezonowych zbiorników wodnych. Jaja na niskich wysokościach mogą zostać złożone już w połowie lutego w południowym Oregonie[48], od wczesnego stycznia do lipca na północnym zachodzie Waszyngtonu[49], od stycznia do marca na południowym wschodzie tego stanu[50], od środkowego do wczesnego maja w Parku Narodowym Waterton Lake w Albercie[51]. Czas rozrodu podlega znacznym zmianom. Kilka pęków jaj we wczesnym stadium rozwoju znaleziono 8 lipca 1999 na granicy Kolumbii Brytyjskiej na zewnątrz Jasper w Albercie[8]. Osobniki dorosłe sezonowo migrują, by wrócić do zbiorników, w których przyszły na świat, niektóre przemieszczają się w otoczeniu zasp śnieżnych lub w ciepłe wiosenne dni[52]. Dymorfizm płciowy zaznacza się w tym gatunku jedynie w sezonie rozrodczym, gdy dojrzałe płciowo samce demonstrują powiększoną, opuszkowatą okolicę odbytu.

Przed rozrodem dojrzałe ambystomy gromadzą się w dużej liczbie (przekracającej 20 osobników) pod kamieniami i kłodami nieopodal granic swych zbiorników rozrodczych. Intensywny rozród trwa kilka dni[23]. Odpowiednie dlań miejsce to niewielkie niezamieszkały przez ryby stawy, bagniska, płytkie jeziora i tereny podmokłe o wodzie stojącej[53]. U ambystomowatych wykształcił się charakterystyczny taniec godowy, do którego zazwyczaj zalicza się pocieranie się, wydzielanie feromonów przez gruczoły zlokalizowane w okolicy żuchwy, a także przyjmowanie specjalnej pozycji, w której następuje kopulacja. Przyjąwszy ją, samiec składa spermatofor, lepką szypułę połączoną z pakietem zawierającym spermę, po czym kroczy przy samicy z przodu, by dokonać inseminacji. Samiec może parzyć się więcej, niż raz. W przeciągu pięciu godzin zdolny jest do pozostawienia aż 15 spermatoforów[23][33]. Taniec godowy ambystomy długopalcej przypomina ten spotykany u innych gatunków ambystom, szczególnie zaś A. jeffersonianum[54][55], jednakże tutaj nie zauważa się pocierania ani trącania. Za to samiec zmierza wprost w kierunku swej wybranki i łapie ją, kiedy ta próbuje pośpiesznie odpłynąć[55]. Samiec ściska samicę za przednimi łapami i potrząsa. Nazywa się to ampleksusem. Czasami obejmuje on i dokonuje tej czynności z osobnikami należącymi do innych gatunków[49]. Zawsze jednak do chwytania używa przednich kończyn. Nigdy zaś nie używa tylnych podczas tańca godowego, gdy pociera z boku na bok okolice podbródka nad głową samicy. Ta z kolei opiera się mu, później jednak poddaje się adoratorowi. Samiec zwiększa tempo i dynamikę, ocierając się o nozdrza, boki i czasami okolicę odbytu samicy. Gdy ta w końcu stanie się dlań łaskawa, umieszcza swój ogon nad jej głową, podniesioną i falującą na koniuszku. Jeśli wybranka zaakceptuje zaloty, samiec kieruje jej pysk w kierunku rejonu swej kloaki. Oboje poruszają się sztywno w przód, falując miednicami. Stwierdzając wtórowanie mu przez wybrankę, zalotnik zaprzestaje tego i składa swój spermatofor. Samica musi wtedy skierować się w przód razem z samcem. Po podniesieniu ogona samica otrzymuje pakiet spermy. Rzadko kiedy udaje się w pełni zrealizować taniec godowy już za pierwszym podejściem[55]. Kilka dni po parowaniu się samica składa jaja[23].

Podczas zimowych miesięcy w północnej części swego zasięgu występowania ambystoma długoplaca kryje się pod poziomem mrozu w norze wykopanej w twardym podłożu. Razem zimuje od 8 do 14 osobników[34][56]. Podczas hibernacji korzysta z rezerw białkowych i energetycznych zmagazynowanych w skórze i wzdłuż ogona[57]. Białka grają jeszcze drugą rolę: stanowią część mieszanki wydzielanej przez gruczoły skórne, używanej w celach obronnych[58]. Zaniepokojona ambystoma faluje swym ogonem i wydziela kleistą, przypominającą mleko białą substancję o działaniu szkodliwym i lekko trującym[51][59]. Kolor skóry stanowi z kolei ostrzeżenie dla drapieżników (ubarwienie ostrzegawcze), że zwierzę będzie niesmaczne[58]. Wzory i barwy jego skóry różnią się od siebie, od ciemnych, czarnych do czerwonawobrązowych w przypadku tła, na którym widnieją plamki i ciapki od bladoczerwonobrązowych przez bladozielone do jasnożółtych pasków[29][33]. Osobnik dorosły może także odrzucić cześć swego ogona i uciekać, podczas gdy porzucony fragment skręca się, odwracając uwagę drapieżnika. Zjawisko to nazywamy autotomią[60]. Regeneracja i odrośnięcie ogona stanowi przedmiot wielkiego zainteresowania profesji medycznej[61].

Populacjom ambystomy długopalcej zagrażają fragmentacja środowiska, introdukowane gatunki i promieniowanie UV. Leśnictwo, drogi i rozwój zmieniły środowiska lądowe, gdzie płazy migrowały, zwiększył także śmiertelność[62]. Siedlisko ambystomy długopalcej zazębia się z obszarami przemysłu leśnego, dominującego w gospodarce Kolumbii Brytyjskiej i zachodnich Stanów Zjednoczonych. Ambystomy będą musiały zmienić swe migracyjne zwyczaje. Działania leśników przeszkadzają im, nie oferując odpowiednich pasów ochronnych nad brzegami, brakuje też ochrony mniejszych terenów podmokłych, gdzie płazy te dokonują rozrodu[63][64]. Populacje okolicy rzeki Peace w kanadyjskiej Albercie wyginęły z powodu oczyszczenia i drenowania terenów podmokłych na potrzeby rolnictwa[65]. Introdukowanie pstrągów dla celów rybołówstwa sportowego w wielu bezrybnych wcześniej jeziorach także zniszczyło populacje ambystomy długopalcej[66]. Wprowadzone do środowiska złote rybki pożerają jaja i larwy tego gatunku[67]. Zwiększona ekspozycja na promieniowanie UVB stanowi kolejny czynnik przyczyniający się do globalnego spadku liczebności płazów. Wrażliwe nań jest także A. macrodactylum. Zwiększa się przez to liczba osobników zdeformowanych, a spada przeżywalność i tempo wzrostu[68][69][70].

Podgatunek Ambystoma macrodactylum croceum (ambystoma długopalca z Santa Cruz) znajduje się pod szczególną opieką. Objęto go ochroną w 1967 poprzez Endangered Species Act[71]. Podgatunek posiada wąski zasięg występowania w kalifornijskich hrabstwach Santa Cruz i Monterey. Przed ustanowieniem ochrony prawnej kilku utrzymującym się jeszcze populacjom zagrażał rozwój gospodarczy. Tymczasem A. m. croceum jest ekologicznie wyjątkowe. Posiada unikatowy wzór skórny na plecach, niespotykaną tolerancję na wilgoć, stanowi także endemit, którego zasięg występowania nie łączy się z obszarem zamieszkanych przez inne podgatunki[20][72][73][74], do których zaliczamy A. m. columbianum, A. m. krausei, A. m. macrodactylum oraz A. m. sigillatum[75].

W obrębie gatunku wyróżnia się pięć podgatunków[20], rozróżnianych na podstawie ich miejsca życia i wzorów na grzbiecie, szczególnie pręg[26]. Denzel Ferguson opisał biogeograficzny zsięg wzorów skórnych, morfologii, a bazując na tych analizach wprowadzono dwa nowe podgatunki: A. macrodactylum columbianumi A. m. sigillatum[20]. Zasięgi występowania poszczególnych podgatunków zilustrowano w przewodniku o płazach autortwa Roberta Stebbina[26].

Podgatunki cechują się następującymi wzorami skórnymi i innymi cechami morfologicznymi[20][30]:

Badania DNA mitochondrialnego[76] wykazały nieco odmienne zasięgi poszczególnych podgatunków[76]. Analizy genetyczne zidentyfikowały dla przykładu dodatkowy wzór o znacznej dywergencji we wschodniej części zasięgu występowania. Ambystomy powracają na czas rozrodu na miejsce swego przyjścia na świat, co ogranicza ich rozprzestrzenienie. Ogranicza to przepływ genów, a zwiększa stopień różnorodności genetycznej, która, biorąc pod uwagę różne regiony jej występowania, przewyższa poziom mierzony u większości innych grup kręgowców[44]. Naturalne bariery dzielące ten obszar i migracje powstają, gdy ekosystem osusza się, zbliżając się warunkami np. do preriowych. Podobnie rzecz ma się na wyższych wysokościach (ponad 2200 metrów nad poziomem morza), gdzie klimat jest wiele cięższy i chłodniejszy. Warunki zmienaiją się wraz z wysokością, ale powyżej wspomniane 2200 metrów stanowią barierę dla ambystom na większości zasięgu ich występowania na północ od Oregonu[77].

Ambystoma długopalca (Ambystoma macrodactylum) – gatunek płaza ogoniastego z rodziny Ambystomatidae. Osobnik dorosły mierzy od 3,8 do 7,6 cm. Cechuje się cętkowaną, czarną, brązową i żółtą pigmentacją. Analizy paleontologiczne, genetyczne i biogeograficzne sugerują, że powstała około 81 milionów lat temu we wschodniej Ameryce Północnej.

Pierwotny zasięg występowania zwierzęcia obejmuje północny zachód kontynentu, nie wychodząc poza wysokość 2800 metrów nad poziomem morza. Zamieszkuje ono różnorodne środowiska, jak lasy deszczowe klimatu umiarkowanego, lasy iglaste, wybrzeża górskich zbiorników wodnych, równiny porośnięte bylicami, lasy jodłowe (z Abies magnifica), równiny porośnięte trawą Bromus tectorum oraz górskie łąki na skalistych brzegach górskich jezior. W czasie sezonu rozrodczego żyje w strumieniach o wolnym nurcie, stawach i jeziorach. Hibernuje przez zimne miesiące, które przeżywa dzięki zapasom białkowym i energetycznym zmagazynowanym w skórze i ogonie.

Wyróżnia się pięć podgatunków posiadających odrębności genetyczne i ekologiczne, a także fenotypowe (inny zakres barwy i odmienne wzory na skórze). Choć IUCN nadaje zwierzęciu status najmniejszej troski (LC), występuje wiele czynników negatywnie wpływających na środowisko jego życia.

Ambystoma macrodactylum é uma espécie de anfíbio caudado pertencente à família Ambystomatidae. Pode ser encontrada nos Estados Unidos da América e Canadá.[3]

Ambystoma macrodactylum é uma espécie de anfíbio caudado pertencente à família Ambystomatidae. Pode ser encontrada nos Estados Unidos da América e Canadá.

Långtåad mullvadssalamander (Ambystoma macrodactylum) är ett stjärtgroddjur i familjen mullvadssalamandrar som finns i västra USA och Kanada.

Salamandern har en mörk ovansida med en längsgående strimma på ryggen och vanligtvis vitaktiga stänk på sidorna. Strimmans färg varierar hos de olika underarterna. Salamandern är slank med långa tår, och har en längd mellan 10 och 16 cm.[3]

I gränsområdena mellan två underarter kan det finnas korsningar med avvikande utseende. För närvarande känner man till 5 underarter:

Arten finns i många biotoper, som torra buskmarker, skogar, bergsängar och klippstränder vid bergssjöar, och från havsytans nivå till över 3 000 m. De lever underjordiskt utom under parningstiden.[2] födan utgörs av ett flertal ryggradslösa djur, som maskar, iglar, blötdjur, spindlar, hoppstjärtar, skalbaggar, tvåvingar, fjärilar, myror och hopprätvingar. Salamandrarna blir könsmogna vid 1 till 3 års ålder, och livslängden är omkring 10 år.[5]

Fortplantning och larvutveckling sker i grunda, lugna vatten som dammar eller åars och sjöars strandkanter.[2] Salamandern leker mycket tidigt, ofta före snösmältningen (vilken dock kan dröja länge uppe i bergen). I Oregon i den sydliga delen av utbredningsområdet kan salamandrarna vandra till lekvattnen redan i månadsskiftet oktober/november, medan de uppe i bergen inte leker förrän i juni till juli. Honan lägger från 90 till över 400 ägg som kläcks efter 5 till 35 dagar beroende på vattentemperaturen. Tiden för larvutvecklingen varierar mycket, från 50 dagar till nästan 3 år i bergssjöarna. Larven lever av bland annat kräftdjur, insekter och grodyngel. Kannibalism förekommer.[5]

Den långtåade mullvadssalamandern betraktas som livskraftig ("LC") och populationen är stabil. Utsättning av ädelfisk i lekvattnen är dock ett hot.[2]

Långtåad mullvadssalamander (Ambystoma macrodactylum) är ett stjärtgroddjur i familjen mullvadssalamandrar som finns i västra USA och Kanada.

Ambystoma macrodactylum (mô tả bởi Bairdm 1849[1], tên tiếng Anh là long-toed salamander) là một loài kỳ giông trong họ Ambystomatidae. Loài này khi trưởng thành thường đạt chiều dài 4.1–8.9 cm (1.6 tới 3.5 in), chúng có các đốm (hoặc vằn) đen, nâu, và vàng. Phân tích hóa thạch, di truyền học, và địa sinh học cho thấy A. macrodactylum và A. laterale tách ra từ một tổ tiên chung do Đường biển Western Interior vào thế Paleocen.

A. macrodactylum sống ở nơi có độ cao tới 2.800 m (9.200 ft) tại nhiều môi trường, gồm rừng mưa ôn đới, rừng quả nón, sông vùng núi, cây bụi đồng bằng, rừng lãnh sam đỏ, và đồng cỏ dọc xường đá của hồ núi.

A. macrodactylum là một thành viên của họ Ambystomatidae. Ambystomatidae tách ra từ nhóm chị em Dicamptodontidae cách nay 81 triệu năm (Creta muộn).[2][3][4] Ambystomatidae cũng là thành viên của phân bộ Salamandroidea, phân bộ này gồm tất cả lưỡng cư có đuôi thụ tinh trong.[5] Họ hàng gần nhất của A. macrodactylum là A. laterale, phân bố tại miền đông Bắc Mỹ. Tuy nhiên, phát sinh loài cấp loài của Ambystomatidae chưa hoàn toàn rõ ràng và cần nhiên cứu thêm.[6]

Ambystoma macrodactylum (mô tả bởi Bairdm 1849, tên tiếng Anh là long-toed salamander) là một loài kỳ giông trong họ Ambystomatidae. Loài này khi trưởng thành thường đạt chiều dài 4.1–8.9 cm (1.6 tới 3.5 in), chúng có các đốm (hoặc vằn) đen, nâu, và vàng. Phân tích hóa thạch, di truyền học, và địa sinh học cho thấy A. macrodactylum và A. laterale tách ra từ một tổ tiên chung do Đường biển Western Interior vào thế Paleocen.

A. macrodactylum sống ở nơi có độ cao tới 2.800 m (9.200 ft) tại nhiều môi trường, gồm rừng mưa ôn đới, rừng quả nón, sông vùng núi, cây bụi đồng bằng, rừng lãnh sam đỏ, và đồng cỏ dọc xường đá của hồ núi.

A. m. columbianum

A. m. croceum(英语:Santa Cruz Long-toed Salamander)

A. m. krausei

A. m. macrodactylum

A. m. sigillatum

长趾钝口螈(Ambystoma macrodactylum,贝尔德 1849年)[1] 是钝口螈科中的一种摩尔蝾螈。成年长趾钝口螈通常身长4.1-8.9厘米(1.6-3.5英寸),其特征为周身夹杂的黑色、棕色、和黄色色素斑点,以及位于后肢突出生长的第四根脚趾。化石记录, 遗传学和 生物地理学的研究表明:长趾钝口螈和蓝点钝口螈均起源于同一祖先。由于古新世时期北美中大陆航道的流失,它们的祖先迁移至科迪勒拉山脉西部地区。

长趾钝口螈主要分布于海拔高度范围可至2800米(9200英尺)的太平洋西北部地区。它们的栖息地种类繁多,其中包括温带雨林,针叶林,山地河岸带,山艾树灌木平原,紫果冷杉林,半干旱地区的山艾树林,绢雀麦平原,以及沿着山地湖区石岸边的高山草甸。在水中野生繁育阶段,长趾钝口螈生活于水流速度较慢的溪流、池塘、以及湖中。寒冬时节是长趾钝口螈的冬眠期,它们依靠先前储藏在皮肤以及尾部的能量储备来维持生命。

长趾钝口螈的五个亚种有着不同的遗传史和基因史,通过它们不同的颜色以及皮肤纹理进行表型区分。尽管国际自然保护联盟(IUCN)将长趾钝口螈划分为无危物种,各式的土地开发活动都对蝾螈的栖息地造成了不良影响甚至威胁到了它们的生存。

长趾钝口螈,又称摩尔蝾螈,是钝口螈科的一员。钝口螈科起源于它的近亲陆巨螈科,时间可追溯至大约8100万年前(白垩纪晚期)。[2][3][4] 此外,长趾钝口螈还属于包含所有具备体内受精能力的蝾螈亚目。[5]长趾钝口螈的姊妹种是分布在北美洲东部地区的蓝点钝口螈。然而,目前关于长趾钝口螈的物种层面的系统发生学的解说只是初步假定,仍需进一步考证。[6]

长趾钝口螈的身体呈暗黑色,背部点缀着棕褐色、黄色、或者橄榄绿的条纹。这些条纹有时会破裂形成一系列斑点。它们的身体两侧可能带有白色或者浅蓝色的细小斑点。腹部呈深棕色或炭黑色,带有白色的细小斑点。它们的身体常伴有根瘤,但这些根瘤并不会像如虎纹钝口螈那样的其他蝾螈那样生长。[7]

长趾钝口螈的卵和棕纤钝口螈 (A. gracile) 还有虎纹钝口螈(A. tigrinum)的卵十分相像。[8] 如同其他两栖动物一样,长趾钝口螈的卵被一层胶状外膜包裹着。这层透明的囊状外膜可使它们的胚胎在形成过程中透过外界看到。[7] 与棕纤钝口螈的卵不同的是,长趾钝口螈的卵没有可见的绿藻来使卵胶呈现出绿色。与虎螈上部浅棕灰色下部乳白色的胚胎相比,在长趾钝口螈的卵内,胚胎的上部呈现出暗沉的颜色且下部颜色较白。这些卵约2毫米 (0.08英寸)大小,但当外围的胶状膜较宽时,它们的半径也会随之增大。[8][9]在卵被完全孵化之前—在卵内胚胎和新生幼体体表—都长有一种平衡器,这种平衡器是细小的皮肤突起,依附在胚胎或幼体身体和头部两侧起到支撑作用。这些平衡器最终将脱落,并且它们的外腮会逐渐长大。[10] 一旦这些平衡器脱落,幼体便会因它们尖锐的喇叭状的外腮而被立即识别。随着长趾钝口螈幼体的成熟和变形,它们的四肢以及手足趾将会显现,而外腮会逐渐消失。[8][10]

长趾钝口螈幼体的表皮夹杂着黑色、棕色、或者黄色的色素。随着幼体生长 色素细胞开始游离并在身体不同部位聚集,因此造成了肤色的变化。这些色素体又被称为色素细胞,源自于生物的神经嵴。蝾螈体内的三种色素细胞包括黄色素细胞、载黑素细胞、和银色闪光细胞 (或含鸟粪素细胞)[11][12] 随着幼体逐渐成熟, 载黑素细胞沿身体不断聚集并且使得整体肤色变暗。 黄色素细胞将沿脊椎和四肢上端排列。 身体的其余部分将沿躯体两侧和下方缀满细小的闪光细胞。[11][13]

在长趾钝口螈幼体变形过程中,它们肢芽的突起物会蜕变成手指和足趾。 一只变形完毕的长趾钝口螈的两个前肢各有四根脚趾,而两个后肢各有五根脚趾。[14] 它们的头的长度大于头的宽度,头部宽大,成熟幼体以及成年长趾钝口螈后肢第四根脚趾比其他指头更长,这是它们区别于其他同源物种的一大特征,并且也顺应了描述它这一特征的种加词语源:macrodactylum (希腊语 makros = 长的, daktylos = 脚趾)。[15] 成年长趾钝口螈的皮肤从深棕色、暗灰色到黑色依次渐变,在表皮上通常会有一道黄色、绿色、或者暗红色的斑纹,斑纹两侧点缀着小斑点。 在它们的四肢、头部、以及躯干下面,覆盖着由白色和桃色渐变至棕色的皮肤,这部分皮肤通常带有大块的白色斑点和小块的黄色半点。[8][16] 成年长趾钝口螈通常身长3.8-7.6厘米 (1.5-3.0 英寸)。

长趾钝口螈的栖息地种类十分广泛,遍布温带雨林,针叶林,山地河岸带,山艾树灌木平原,紫果冷杉林,半干旱地区的山艾树林,绢雀麦平原,以及沿着山地湖区石岸边的高山草甸。[7][13][17] 成年长趾钝口螈有时栖息于草木丛生的森林次冠层叶簇,有时藏匿在粗木质残体中,或者在岩石缝隙以及小型哺乳动物洞穴中。在春季繁殖季节,成年长趾钝口螈主要活动场所在碎石残木以及河流池塘的河岸浅滩之中。季节性水域常常受到它们的造访.[7]

此种类的蝾螈是北美洲分布最广的蝾螈之一,其分布广度仅次于虎螈。它们的栖息地位于海拔在2800米(9200英尺)之上的地方,覆盖了多种植被。[7][13][18][19][20] 这些区域包括蒙特利湾以及加利福尼亚州的圣克鲁兹的地方种群[21] 这些栖息地在经由太平洋海岸绵延至阿拉斯加州首府朱诺的内华达山脉东北部地区再次连接,从而与塔库及斯蒂金河溪谷的种群融合。从太平洋海岸开始,其分布范围沿南北方向延伸至位于美国蒙大拿州和加拿大艾伯塔省交界处的落基山脉东部山麓。[22][23][24]

和所有两栖动物一样,长趾钝口螈的生命起始于一颗小小的卵。在长趾钝口螈活动区域的北端,它们将卵产在杂乱的草丛、树杈、石堆之间,或者在淤泥遍布的池塘底部。[25] 每个卵块所包含的卵的数量依大小不同而不一,通常最多可达到每个卵块110颗卵。[26] 成年雌性长趾钝口螈消耗大量体力用于产卵。临近繁殖期,它们的卵巢大小甚至会占据身体总体积的一半。人们曾在一只成年雌性长趾钝口螈的卵巢内发现共计264颗卵。据估计,每颗卵的直径约为0.5毫米(0.02英寸)。[27] 卵块由一个胶质外膜包裹着,将一个个卵聚集在一起,并且这个胶质外膜保护着每颗卵的外膜。[28] 有时,这些卵会被单独产下,这种情况通常出现在加拿大及美国南部等气候温暖的地区。长趾钝口螈的卵胶每年都会被当作生物材料供给进行利用,这些生物材料是浅水水源生态系统和与其毗邻的森林生态系统中的化学成分与营养物动态的重要组成部分。[29] 此外,长趾钝口螈的卵还为水霉菌(又称卵菌)提供了必要的生长环境。[30]

长趾钝口螈的幼体经历两到六周从卵中被孵化出来[25] 它们生来便是肉食动物,刚出生时,它们本能地依靠食用出现在视野范围内的小型无脊椎动物为生。食物种类包括小型水生甲壳动物(水蚤类动物,桡足类动物和介形亚纲动物),双翅类昆虫,和蝌蚪。[31] 随着长趾钝口螈逐渐长大,它们自然而然地开始捕获体型更大些的猎物。为了提高它们的生存几率,部分长趾钝口螈的头部越长越大,它们会同类相食,不惜残杀自己的配偶。[32]

长趾钝口螈幼体长大至成熟需经历至少一个季度的时间(在太平洋海岸地区,幼体期通常持续四个月),[22] 它们的外腮会消失,发生生物变态,从幼体逐渐变为频繁活动于森林下层灌丛中的陆生生命体。报道称这一生物变态行为早在七月便在海平面地带开始进行,[33]而圣克鲁斯长趾钝口螈的变形发生在每年十月到十一月,甚至会延续到次年一月。[16] 高海拔地区的长趾钝口螈幼体可能会在越冬之后继续保持幼体形态生长一个季度,直到最终的变形。[34] 在海拔较高的湖区,处于变形期的长趾钝口螈幼体的吻肛长(SVL)可达47毫米(1.9英寸)。但在低海拔地区的幼体们生长速度较快,并且通常在体长达到35-40毫米(1.4-1.6英寸)时进行变形。[35]

成年后的长趾钝口螈往往不易暴露在人们的视野中,因为它们过着秘密的地下生活:挖洞,迁移,以及靠吃森林土壤、腐烂的树干、啮齿动物洞穴、和岩石裂隙中的无脊椎动物为生。成年钝口螈的食物来源主要有昆虫、蝌蚪、蠕虫、甲壳虫以及小鱼。蝾螈的天敌主要有乌梢蛇、小型哺乳动物、鸟类、还有鱼类。[36] 成年长趾钝口螈的寿命通常为6-10年,体重最重可达约7.5克(0.26盎司),吻肛长最长可达8厘米(3.1英寸),总体长可至14厘米(5.5英寸)。[37][38]

长趾钝口螈的生命周期随海拔及气候改变而相应发生变化。季节性迁入或迁出繁殖池的日期会根据持续的降雨量或冰雪消融而变化,因为降雨或融化的积雪时常导致这些季节性池塘的水位再次上涨而无法进行繁殖。在俄勒冈州南部,早在二月中旬,长趾钝口螈将卵产在的低海拔地区,[39] 在华盛顿州西北部地区,它们在一月至七月期间进行产卵,[40] 而在华盛顿州东南部地区,它们选择在一月至三月之间产卵,[41] 在加拿大艾伯塔省的沃特顿湖国家公园,产卵期则发生在四月中旬至五月初。[42] 长趾钝口螈的繁殖时机极其多变;值得注意的是,在1999年7月8日,处于生长初期的一些长趾钝口螈卵块在沿加拿大艾伯塔省贾斯珀与英属哥伦比亚的交界地区被发现。[43] 成年长趾钝口螈会季节性地回到它们出生的繁殖池,通常雄性长趾钝口螈会比雌性长趾钝口螈提前到达繁殖池并且待的时间较长。据观察,个别长趾钝口螈在暖春时节沿着积雪进行迁移。[44] 性别差异(或两性异形)只有在繁殖季节才得以体现在长趾钝口螈身上,成年雄性长趾钝口螈会在繁殖季显现出增大的或者球根状的肛部。

蝾螈的繁殖期取决于它们栖息地的海拔和纬度。总体上说,生活在低海拔地区的蝾螈选择在秋季、冬季、以及早春时节进行繁殖活动。而在高纬度地区,蝾螈的繁殖期集主要为春季和初夏。尤其是气候较温暖的地区,蝾螈会选择在水面浮冰尚未完全融化的池塘与湖泊里活动。[7]

大量的成年长趾钝口螈(>20只)聚集在沿岸靠近繁殖点的岩石或原木下方等待繁殖,并且繁殖活动会在短短几日内集中爆发。[16] 适宜的繁殖点包括小型鱼塘、沼泽湿地、浅水湖泊、和其他静水湿地。[45] 和其他钝口螈科生物一样,长趾钝口螈也逐渐衍生出独有的求偶舞蹈。在进行交配前,它们用搓挠身体,通过下巴处的腺体释放信息素。一旦交配开始,雄性长趾钝口螈预先排出精囊。这种精囊是一种粘性的茎状物,顶端储存着一堆精子,缓慢进入雌性长趾钝口螈体内使其受精。雄性长趾钝口螈通常交配多次,并且会在五小时的时间内排出15个精囊。[16][25] 长趾钝口螈的求偶舞蹈和其他钝口螈属生物有很多相像之处,尤其近似于杰斐逊钝口螈。[46][47] 而在长趾钝口螈求偶时没有搓挠或者用头部撞击对方的动作,雄性长趾钝口螈趁雌性试图游走之前直接靠近并紧贴对方身体进行交配。[47] 雄性长趾钝口螈从雌性长趾钝口螈前肢的后方紧紧缠绕住雌性的身体并晃动,这种行为叫做抱合。在繁殖期,有时雄性长趾钝口螈也会对其他两栖动物发生此类行为。[40] 在求偶时,雄性长趾钝口螈只会使用前肢缠绕雌性配偶而不使用后肢,因为它们需使用后肢从两侧搓挠紧压着雌性头部的下颌。一开始,雌性长趾钝口螈试图挣扎,但慢慢会屈从。雄性趁机加快求偶动作的频率和速度,搓挠雌性配偶的鼻孔和身体两侧,有时搓挠雌性的肛部。当雌性长趾钝口螈逐渐屈从缓和,雄性长趾钝口螈则用尾部带动身体前移至雌性的头部位置,拱起身体,颤动尾部。一旦雌性长趾钝口螈接受了雄性的求偶,雄性长趾钝口螈会将雌性的口鼻部靠近自己的肛部,伴随着骨盆部位的起伏动作,双方都僵硬地向前移动身体。随着雌性长趾钝口螈渐渐配合,雄性会停止颤动骨盆并排出一个精囊。与此同时,雌性会随雄性向前移动,并拱起自己的尾部来接收精子。完整的求偶过程基本需多次尝试才可完成。[47] 雌性长趾钝口螈将在交配完成几天之后产下幼卵。[16]

此种类的蝾螈是北美洲分布最广的蝾螈之一,其分布广度仅次于虎螈。它们的栖息地位于海拔在2800米(9200英尺)之上的地方,覆盖了多种植被。[7][13][18][19][20] 这些区域包括蒙特利湾以及加利福尼亚州的圣克鲁兹的地方种群[21] 这些栖息地在经由太平洋海岸绵延至阿拉斯加州首府朱诺的内华达山脉东北部地区再次连接,从而与塔库及斯蒂金河溪谷的种群融合。从太平洋海岸开始,其分布范围沿南北方向延伸至位于美国蒙大拿州和加拿大艾伯塔省交界处的落基山脉东部山麓。[22][23][48]

除了春寒期,生活在低地的成年蝾螈在一整个漫长冬季都保持活跃。但在北部栖息地,每到寒冬时节,长趾钝口螈则成群结队地躲藏在冻结线以下粗糙的地底进行冬眠,通常每个越冬群成员数为8-14只。[26][49] 当冬眠的时候,长趾钝口螈依靠皮下以及尾部两侧所囤积的蛋白质存活。[50] 这些蛋白质还有另一功能:作为长趾钝口螈皮肤分泌物的混合成分之一,它们还起到防御作用。[51] 一旦受到威胁,长趾钝口螈会摆动尾部并同时分泌出一种乳白色的的粘性有毒物质。[42][52] 长趾钝口螈的肤色会向捕食者发出“请勿食用”警告(警戒作用)[51] 它们皮肤的颜色和图案变化多端,有时整体肤色会从暗黑色变成泛红的棕色,表面点缀着的浅棕红色或浅绿色斑点时而会变成亮黄色的条纹。[22][25] 一只成年长趾钝口螈有时会截断自己的尾部的一小截并且迅速逃走,被截掉的尾巴则会像诱饵一样蠕动;这种现象叫做自截。[53] 尾部再生现象是两栖动物发育生理学的一个范例,它对于医疗界有着重大研究意义。[54]

国际自然保护联盟将长趾钝口螈分类为无危物种后,[55] 多种形式的土地开发都对长趾钝口螈产生了负面影响,并为其保护生物学拓展了新的前景展望与优先侧重点。优先保护强调物种多样性中的种群层次,而物种多样性正以物种灭绝速率十倍的速率递减。[56][57][58][59] 种群层次多样性是生态系统服务的基石,[60] 例如,蝾螈在土壤生态系统中所扮演的基本角色中有一个就是促进养分循环,这有效保护了森林湿地的生态体统。[61]

两栖动物的双重生命周期这一特征常常被用来解释它们为何被视为优良的环境健康指示器或者“煤矿里的金丝雀”。和其他所有的两栖动物一样,长趾钝口螈拥有水陆两个阶段的转型期,并且有着半透明的皮肤。由于两栖动物在水栖和陆栖两个阶段所承担的生态功能不同,失去一个两栖物种无异于失去两个生态物种。[62] 其次,所有两栖动物如长趾钝口螈,[63] 都对接触污染物更为敏感,因为它们通过皮肤直接吸收水和氧气。但是一直以来,它们这种对污染物的敏感反应的有效性都存在质疑。[64] 由于不同两栖动物物种间的生命周期呈现差异,不是所有的两栖动物都对环境污染和破坏都表现出同等的敏感度,因此问题也变得更加复杂化。[65]

栖息地零碎化、外来物种以及紫外线辐射都对长趾钝口螈的数量构成威胁。林业和公路建设等土地开发活动都在使两栖动物的生存环境发生着巨变,并且悄然增加它们的死亡率。[66] 沃特顿湖国家公园等地区都加设了公路隧道地下通道来保证安全通行以及物种迁移。林业是英属哥伦比亚以及美国西部地区的主要经济来源,但随着林业建设的发展,长趾钝口螈的分布广泛重合。林业建设意味着大规模的缓冲区以及适宜蝾螈繁育的小型湿地的面积会急剧减少,受此恶劣影响,长趾钝口螈将在很大程度上改变它们的迁移习性。[67][68] 位于加拿大艾伯塔省皮斯河谷周边的长趾钝口螈数量几乎为零,原因就是当地的湿地被清理和改造以便农用。[69] 为加强捕鱼活动而引进的鳟鱼使原先鱼苗很少的湖泊发生转变,长趾钝口螈的数量也因此急剧减少。[70] 被引进的金鱼则是以长趾钝口螈的卵和幼体为食。[71] 暴露在不断增强的紫外线辐射下是全球范围内长趾钝口螈等两栖动物数量减少的又一因素。这些辐射致使两栖动物畸形,并且大幅降低它们的存活率和生长速度。[72][73][74]

长趾蝾螈亚种中的圣克鲁斯长趾蝾螈(Ambystoma macrodactylum croceum)曾受到特殊关注。1967年颁布的的美国濒危物种法案也给予圣克鲁斯长趾蝾螈密切保护。[75] 圣克鲁斯长趾蝾螈的栖息地范围很小,它们主要分布在位于加利福尼亚州圣塔克鲁斯县和蒙特雷县。在受到法律保护之前,一些仅存的圣克鲁斯长趾蝾螈曾一度受到人类资源开发活动的威胁。它们在生态系统中有着独一无二的地位,它们的背部皮肤有着特殊的不规则图案,具备得天独厚的耐湿性,并且它们是与其他同源物种隔离生存的特有种。[13][76][77][78] 它们的其他同源物种包括哥伦比亚长趾蝾螈、克劳斯长趾蝾螈、长趾钝口螈以及南部长趾蝾螈。[23]

长趾钝口螈的祖先来自蝾螈物种丰富度最高的北美洲东部地区。[79][80] 对于长趾钝口螈后来进入北美洲西部地区的生物地理解释皆基于化石、遗传学以及生物地理学的描述。[43][81] 与长趾钝口螈亲缘关系最近的现存姊妹物种是蓝点钝口螈,这是北美洲东北部的本土物种。[3][80] 在白垩纪时期(~145.5–66 Ma),北美中大陆航道和西部内陆海道东南方向地区还尚未出现钝口螈科生物的踪影。[80][82]然而其他三种钝口螈(虎纹钝口螈、加州虎纹钝口螈和棕纤钝口螈)都在北美洲西部地区有着共用的栖息地。相比之下。长趾钝口螈的近亲蓝点钝口螈则是地道的东北部物种。[3][80] 有研究表明,在古新世(~66–55.8 Ma)之后,北美洲西部内陆海道的消失致使蝾螈祖先通往科迪勒拉山脉西部的道路受阻,长趾钝口螈因此便由蓝点钝口螈演变而来的。[81] 到达北美洲西部的山区之后,所有物种必须尽快适应这个受海拔影响的动态空间的复合生态环境,因为山形与海拔在不断增高,并且气候也在不断变化。例如,太平洋西北地区在古新世时期气候变冷,这为之后温带雨林取代白垩纪时期的热带雨林创造了必要条件。[83]从渐新世晚期到中新世期间,落基山脉的高度抬升,从而使得长趾钝口螈以及其它西部物种与生活在东部温带气候环境中的物种隔绝开来。造山运动阻挡了西风气流中的水汽,从而形成了一道天然的屏障,并且使从加拿大艾伯塔省南部至墨西哥湾之间的整个中部大陆保持气候干燥。[43][84]

直到始新世,当时蝾螈的先辈们都倾向于分散或迁移到落基山脉及其周边地区来寻找栖身之所。在始新世中期,湿度适中的森林在北美洲西部地区拔地而起,当到了上新世早期时,它们的分布已经形成了一定的规模。在此期间(古近纪到新近纪)的温带森林溪谷和山地会对日后适宜长趾钝口螈生存的栖息地提供必要的地形地貌与生态要素。[43][81][85][86]喀斯喀特山脉形成于上新世中期并由此造成了雨影效应。雨影效应造就了哥伦比亚盆地干旱少雨的气候,同时也改变了位于高海拔地区的温带湿地生态环境状况。随着喀斯喀特山脉的形成与壮大,哥伦比亚盆地变得干旱少雨。这是北美洲西部地区的生物地理特征。得益于此,包括长趾钝口螈在内生活在这里的物种被明确划分为沿海类群与内陆类群。[81][84][86][87]

长趾钝口螈拥有五个亚种。[13] 这些亚种可以通过它们的地理分布情况以及背部图案来进行识别。[7] 丹泽尔·弗格森从生物地理学角度对它们各异的皮肤图案和形态给出了解释。基于现有的分析,弗格森还介绍了两个新的长趾钝口螈亚种:哥伦比亚长趾蝾螈和南部蝾螈。[13] 这些亚种的排布均显示在罗伯特·斯特宾的两栖动物分布地指南。[7]

长趾钝口螈亚种的皮肤和形态特征的差异总结为以下几点:[13][23]

线粒体DNA分析法[81] 识别出了这些亚种不同的族系。[81] 例如基因分析法就识别出了位于东部栖息地的长趾钝口螈另外的一种深层差异。从空间分布与历史角度来说,这种长趾钝口螈种群数量以及遗传特征的空间分布通过北美洲西部地区那交织在一起的山地与温带山谷而连接在一起。[81][88] 长趾钝口螈定期的季节性繁殖(归家冲动)以及其他迁徙性行为降低了它们在诸如山间盆地等地区的扩散率。这种行为限制了长趾钝口螈的基因流动,并且增加了基因分化的比率。这些地区的长趾钝口螈基因分化率远远大于同地区其它绝大部分脊椎动物种群。[35] 在生态系统逐渐转化为气候较为干燥的耐旱低地(如大草原气候)以及较严寒和气候严峻的高海拔地带(2,200米(7,200英尺))时,生物扩散和迁徙行为的自然间断则频频发生。[89]

汤普森和罗素发现了另一种演化系谱,此系谱源自爱达荷州被冰川隔绝的鲑鱼河山区。[81] 大约在一万年以前,随着全新世間冰期的到来,更新世的冰川逐渐消融,打开了连接南北的迁徙通,如今南部物种已与通道以北地区的克劳斯长趾蝾螈共同生活,并共同向北迁徙至皮斯河(加拿大)河谷。[81] 弗格森还在同地区注意到了一个种族混种现象,那是发生在栖息于比特鲁特岭和塞尔扣克山脉两侧的哥伦比亚长趾蝾螈和克劳斯长趾蝾螈两个形态亚种之间的现象。[13] 汤普森和罗素指出,结合区位于这两个不同的亚种之间的原因是哥伦比亚长趾蝾螈族群在地理上处于隔绝与受限的状态,它们无法进入俄勒冈山区的中部。[81]

长趾钝口螈(Ambystoma macrodactylum,贝尔德 1849年) 是钝口螈科中的一种摩尔蝾螈。成年长趾钝口螈通常身长4.1-8.9厘米(1.6-3.5英寸),其特征为周身夹杂的黑色、棕色、和黄色色素斑点,以及位于后肢突出生长的第四根脚趾。化石记录, 遗传学和 生物地理学的研究表明:长趾钝口螈和蓝点钝口螈均起源于同一祖先。由于古新世时期北美中大陆航道的流失,它们的祖先迁移至科迪勒拉山脉西部地区。