tr

kırıntılardaki isimler

Asiya hepardı (lat. Acinonyx jubatus venaticus) və ya İran hepardı, Fars hepardı — Hepard növünə daxil olan yarımnövlərdən biri. Əvvəllər əsasən Yaxın Şərq və Hisndistanın müxtəlif ərazilərində yayılmışdır[1][2]. Onların ümumi arealı Şimalda Qafqaz, Mərkəzi Asiya, cənubda Ərəbistan yarımadası, Hind okeanı sahilləri, qərbdə Suriya, Aralıq dənizi sahillərindən tutmuş şərqdə Hindistana qədər uzanırdı. Hazırda isə onlar kiçik bir populyasiyalar şəkilində ancaq İran ərazisində qalmışdır. XX əsrdən etibarən ancaq kiçik bir ərazidə qala bilmişlər. 2011-ci ilin dekabr ayından 2013-cü ilin noyabr ayına qədər yayıldığı ərazidə onların 84 fotoşəkili çəkilmişdir[3][4]. 2017-ci ilin dekabr ayına görə İranın mərkəzi yaylasında 140 min km² ərazidə bu canlıların 50-dən çox populyasiyasına rastlanmışdır. 2014 FIFA Dünya Kubokunun İran Milli Futbol Komandası rəmzi olmuşdur.

Asiya hepardı 32 min ildən 67 min ilədək öncə Afrika hepardından ayrılmışdır.

Xarici görkəm baxımından Asiya Hepardlarını Afrika hepardlarından fərqləndirmək olduqca çətindir. Bu əsasən genetik xüsusiyyətlərinə görə müəyyən edilmişdir. Üstəlik bu canlıların xəzinin qalınlığı nisbətən azdır[5]. Bu canlılarda bir qayda olaraq dişilər erkəklərdən kiçik olur. Onların bədən uzunluğu 110—150 sm, quyruqlarının uzunluğu 60—80 sm, ayaq üstə hündürlükləri 70—85 sm, çəkiləri isə 40-60 kq arasında dəyişir.

Asiya hepardlarının yayılma ərazisi - dağlıq rayonlar, həmcinin yarımsəhra və quru çöllər. Bu canlılara nadir hallarda meşə massivlərində rastlamaq olar. Onların əsas ov abyektləri çütdırnaqlılardır (dağ qoyunu, ceyran, keçi)[6]. Hazırda isə təbiəytdə iri ot yeyən məməlilərin azalması səbəbindən kiçik çikarlarıda yeyə bilirlər. üstəlik ev heyvanlarına da hücumu qeydə alınır. Bir qayda olaraq yalquzaq həyat tərzi keçirirlər. Ancaq iri heyvanların ovlanması məqsədi ilə kiçik qruplar təşkil edəı bilirlər. Bunlar arasında sayları 4 baş belə ola bilir. Dişilərdə boğazlıq dövrü 85-95 gün davam edir. Adətən 2-6 arası bala doğur[7]. Balaların sərbəst həyata başlaması 12-20 aylarında baş verir. Asiya hepardlarının təbii şəraitdə ömür müddəti 20-25 ildir. Onlar qapalı şəraitdə hec zaman çoxalmırlar.

Əvvəllər Asiya hepardları Ərəbistan və Fələstindən Hindistanın daxili rayonlarına, şimalda isə Qazaxıstana qədər olan ərazidə yayılmışdır. Ancaq onların dərilərinə görə brakonerlər tərəfindən kütləvi ovlanması, ot yeyən heyvanların sayında olan azalma, yayılma arelınmın insanlar tərəfindən mənimsənilməsi onların sayı da azalmağa başlamışdır. Artıq 1947-ci ildə Hindistanda Asiya hepardlarının nəsli kəsilmişdir[8]. XX əsrin 60-80-ci illərdə isə İran istisna olmaqla Yaxın Şərq regionunda bu canlılar yoxa çıxmışdır. 2000-ci ildə ətraf mühitin qorunması cəmiyyələri İranla müştərək şəkildə bu canlıların qorunması məqsədi ilə ölkənin 5 rayonunda tədbirlər görməyə başlamışlar. 2000-ci illərdə aparılan araşdırmalar zamanı vəhşi təbiətdə bu canlıların sayının 50-100 arası olması qeydə alınmışdır[9][10]. Gələcəkdə bu canlıların Pakistan və Hindistan ərazilərinə köçürülərək artırılması planları vardır[11].

|deadlink= ignored (|dead-url= suggested) (kömək) Asiya hepardı (lat. Acinonyx jubatus venaticus) və ya İran hepardı, Fars hepardı — Hepard növünə daxil olan yarımnövlərdən biri. Əvvəllər əsasən Yaxın Şərq və Hisndistanın müxtəlif ərazilərində yayılmışdır. Onların ümumi arealı Şimalda Qafqaz, Mərkəzi Asiya, cənubda Ərəbistan yarımadası, Hind okeanı sahilləri, qərbdə Suriya, Aralıq dənizi sahillərindən tutmuş şərqdə Hindistana qədər uzanırdı. Hazırda isə onlar kiçik bir populyasiyalar şəkilində ancaq İran ərazisində qalmışdır. XX əsrdən etibarən ancaq kiçik bir ərazidə qala bilmişlər. 2011-ci ilin dekabr ayından 2013-cü ilin noyabr ayına qədər yayıldığı ərazidə onların 84 fotoşəkili çəkilmişdir. 2017-ci ilin dekabr ayına görə İranın mərkəzi yaylasında 140 min km² ərazidə bu canlıların 50-dən çox populyasiyasına rastlanmışdır. 2014 FIFA Dünya Kubokunun İran Milli Futbol Komandası rəmzi olmuşdur.

Asiya hepardı 32 min ildən 67 min ilədək öncə Afrika hepardından ayrılmışdır.

El Guepard asiàtic (Acinonyx jubatus venaticus), també conegut com a guepard iranià és una espècie críticament amenaçada de guepard, és concretament una subespècie, que actualment només es troba a l'Iran. Abans es trobava també a l'Índia on ja és extint.[1]

El guepard asiàtic viu principalment al desert central de l'Iran en situació de poblacions fragmentades. L'any 2013, només 20 guepards es van identificar a l'Iran.[2] La població total estimada és d'entre 40 a 70 individus, els accidents en carretera suposen els dos terços de les seves morts.

El guepard asiàtic es va separar del seu parent africà fa entre 32.000 i 67.000 anys enrere.[3] Junt amb el linx eurasiàtic i el lleopard persa, és un dels gran fèlids actuals a Iran.

El cap i el cos del guepard asiàtic adult mesuren 112 -135 cm amb una llargada de la cua entre 66 i 84 cm. Pesa de 34 a 54 kg. Els mascles són lleugerament més grossos que les femelles.

El guepard asiàtic es troba en zones desèrtiques al voltant de Dasht-e Kavir i inclou altres de Kerman, Khorasan, Semnan, Yazd, Teheran, i Markazi. La majoria viuen en cinc santuaris de la vida silvestre: Parc Nacional de Kavir , Parc Nacional de Touran , Àrea protegida de Bafq, Reserva de la vida silvestre de Daranjir i Reserva de la vida silvestre de Naybandan.[4]

Les preses del guepard asiàtic són petits antílops, a l'Iran principalment gaseles Jebeer, gaseles perses, ovella silvestre, cabra salvatge i llebre del Cap.

El Guepard asiàtic (Acinonyx jubatus venaticus), també conegut com a guepard iranià és una espècie críticament amenaçada de guepard, és concretament una subespècie, que actualment només es troba a l'Iran. Abans es trobava també a l'Índia on ja és extint.

El guepard asiàtic viu principalment al desert central de l'Iran en situació de poblacions fragmentades. L'any 2013, només 20 guepards es van identificar a l'Iran. La població total estimada és d'entre 40 a 70 individus, els accidents en carretera suposen els dos terços de les seves morts.

El guepard asiàtic es va separar del seu parent africà fa entre 32.000 i 67.000 anys enrere. Junt amb el linx eurasiàtic i el lleopard persa, és un dels gran fèlids actuals a Iran.

Gepard indický (Acinonyx jubatus venaticus) je poddruh geparda štíhlého (Acinonyx jubatus) patřící do čeledi kočkovití (Felidae) a podčeledi malé kočky (Felinae), i když byli gepardi dříve řazeni do podčeledi Acinonychinae. Druh popsal Edward Griffith.

Tato kočkovitá šelma se dříve vyskytovala v pásu suchých oblastí Asie od Arabského poloostrova až po Indii. V současnosti žije s jistotou jen v Íránu a to maximálně 100 jedinců (spíše však méně).

Gepard indický je štíhlejší, menší a o něco kratší, než jeho africký příbuzný. Na délku měří 112 - 135 cm (plus cca 65 - 85 cm měří ocas) a váží 34 - 54 kg. Samci jsou o něco větší než samice.

Živí se masem, které získávají aktivním lovem. Na kořist utočí na vzdálenost několika desítek metrů prudkým zrychlením po předchozím opatrném přiblížení. Gepardi jsou velice rychlí a dovedou vyvinout rychlost až okolo 100 km/h, nicméně nejsou schopni příliš dlouhého pronásledování (maximálně několik set metrů). Po lovu jsou obvykle velmi vyčerpaní resp. přehřátí a musejí si odpočinout, aby se ochladili, jinak mohou i uhynout. Jejich oblíbenou kořistí jsou různé menší antilopy a gazely např. činkara (gazela indická), džejran, dále pak muflon, koza bezoárová a zajíc africký (Lepus capensis). V nouzi loví i hlodavce.

V přírodě zbývá pouhých několik desítek těchto koček. Hrozí jim extrémně vysoké riziko vyhynutí a IUCN proto geparda indického zařadilo mezi kriticky ohrožené taxony.[2][3]

Společně s tímto poddruhem žil v Asii ještě gepard středoasijský, ale ten již s největší pravděpodobností vyhynul. Většina odborníků však tento poddruh nevyděluje a všechny asijské gepardy řadí do jedné subspecie.

V tomto článku byl použit překlad textu z článku Asiatic cheetah na anglické Wikipedii.

Gepard indický (Acinonyx jubatus venaticus) je poddruh geparda štíhlého (Acinonyx jubatus) patřící do čeledi kočkovití (Felidae) a podčeledi malé kočky (Felinae), i když byli gepardi dříve řazeni do podčeledi Acinonychinae. Druh popsal Edward Griffith.

Азийн үчимбэр (Acinonyx jubatus venaticus) одоо Ираны үчимбэр гэгдэх болсон, Энэтхэгт саяхан устсан боловч Энэтхэгийн үчимбэр нэрээр мөн нэрлэгдэг.

Азийн үчимбэр өдгөө зөвхөн Иранд байдаг, үчимбэрийн нэн ховор дэд зүйл юм. Пакистаны баруун өмнөд хэсгээр хаа нэг тааралдана. Өргөн уудам элсэн цөлд, энд тэнд алаг цоог нутаглана. Урьд нь Баруун Өмнөд Азид Арабаас Афганистаныг оруулаад Энэтхэг хүртэл өргөн уудам нутагт тархаж байсан олон тоо толгойтой, түгээмэл байсан амьтан сүүлийн зууны турш эрс хорогдон, ихэнх нутагт устаж үгүй болжээ. Хамгийн сүүлийн судалгаанаас үзэхэд дөнгөж 70-100 Азийн үчимбэр байгаагийн ихэнх нь Иранд байгаа ажээ. Энэ тоог сүүлийн 10 жилийн турш Ираны элсэн цөлд амьдардаг газраар нь камер урхи тавьж судалсны үр дүнд тогтоосон.[2] Өдгөө Иранд мийнхэн овгийн том амьтдаас Азийн үчимбэр, Персийн ирвэс хоёр л үлдсэн[3]. Нэгэн үе ихэд тархаж байсан Каспийн бар, Азийн арслан сүүлийн зуунд энэ нутаг устаж үгүй болсон. Азийн арслангийн хувьд Энэтхэгт л цөөн тоотой үлджээ.

Азийн үчимбэр (Acinonyx jubatus venaticus) одоо Ираны үчимбэр гэгдэх болсон, Энэтхэгт саяхан устсан боловч Энэтхэгийн үчимбэр нэрээр мөн нэрлэгдэг.

Азийн үчимбэр өдгөө зөвхөн Иранд байдаг, үчимбэрийн нэн ховор дэд зүйл юм. Пакистаны баруун өмнөд хэсгээр хаа нэг тааралдана. Өргөн уудам элсэн цөлд, энд тэнд алаг цоог нутаглана. Урьд нь Баруун Өмнөд Азид Арабаас Афганистаныг оруулаад Энэтхэг хүртэл өргөн уудам нутагт тархаж байсан олон тоо толгойтой, түгээмэл байсан амьтан сүүлийн зууны турш эрс хорогдон, ихэнх нутагт устаж үгүй болжээ. Хамгийн сүүлийн судалгаанаас үзэхэд дөнгөж 70-100 Азийн үчимбэр байгаагийн ихэнх нь Иранд байгаа ажээ. Энэ тоог сүүлийн 10 жилийн турш Ираны элсэн цөлд амьдардаг газраар нь камер урхи тавьж судалсны үр дүнд тогтоосон. Өдгөө Иранд мийнхэн овгийн том амьтдаас Азийн үчимбэр, Персийн ирвэс хоёр л үлдсэн. Нэгэн үе ихэд тархаж байсан Каспийн бар, Азийн арслан сүүлийн зуунд энэ нутаг устаж үгүй болсон. Азийн арслангийн хувьд Энэтхэгт л цөөн тоотой үлджээ.

ஆசியச் சிறுத்தை (Acinonyx jubatus)யையே தமிழகத்தில் வேங்கைப்புலி என அழைக்கின்றனர். இது பெரிய பூனை குடும்பத்தைச் சேர்ந்த பாலூட்டி ஆகும்.

இந்தியாவில் ஆங்கிலேயே ஆட்சிக் காலத்தில் சிறுத்தை வேட்டை மிகப் பெயர் பெற்று இருந்தது.[3]இவற்றின் எண்ணிக்கை 20ம் நூற்றாண்டில் பெருமளவு குறைந்துவிட்டது. 1947ல் மத்திய பிரதேச சுர்குச மன்னர் இச்சிறுத்தையை வேட்டையாடியதே இதை இந்தியாவில் கடைசியாக பார்த்த ஆதாரம். உலகில் இவற்றின் எண்ணிக்கை 70-100 தனியன்களே என மதிப்பிடப்பட்டுள்ளது. தற்போது இவை ஈரானிலும் ஆப்கானிசுத்தானிலும் மட்டுமே காணப்படுகின்ற போதிலும், இவற்றிற் பெரும்பாலானவை ஈரானிலேயே வாழ்கின்றன.

ஆசியச் சிறுத்தை (Acinonyx jubatus)யையே தமிழகத்தில் வேங்கைப்புலி என அழைக்கின்றனர். இது பெரிய பூனை குடும்பத்தைச் சேர்ந்த பாலூட்டி ஆகும்.

இந்தியாவில் ஆங்கிலேயே ஆட்சிக் காலத்தில் சிறுத்தை வேட்டை மிகப் பெயர் பெற்று இருந்தது.இவற்றின் எண்ணிக்கை 20ம் நூற்றாண்டில் பெருமளவு குறைந்துவிட்டது. 1947ல் மத்திய பிரதேச சுர்குச மன்னர் இச்சிறுத்தையை வேட்டையாடியதே இதை இந்தியாவில் கடைசியாக பார்த்த ஆதாரம். உலகில் இவற்றின் எண்ணிக்கை 70-100 தனியன்களே என மதிப்பிடப்பட்டுள்ளது. தற்போது இவை ஈரானிலும் ஆப்கானிசுத்தானிலும் மட்டுமே காணப்படுகின்ற போதிலும், இவற்றிற் பெரும்பாலானவை ஈரானிலேயே வாழ்கின்றன.

The Asiatic cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus venaticus) is a critically endangered cheetah subspecies currently only surviving in Iran.[1] It once occurred from the Arabian Peninsula and the Near East to the Caspian region, Transcaucasus, Kyzylkum Desert and northern South Asia, but was extirpated in these regions during the 20th century. The Asiatic cheetah diverged from the cheetah population in Africa between 32,000 and 67,000 years ago.[3]

The Asiatic cheetah survives in protected areas in the eastern-central arid region of Iran, where the human population density is very low.[4] Between December 2011 and November 2013, 84 individuals were sighted in 14 different protected areas, and 82 individuals were identified from camera trap photographs.[5] In December 2017, fewer than 50 individuals were thought to be remaining in three subpopulations that are scattered over 140,000 km2 (54,000 sq mi) in Iran's central plateau.[6] As of January 2022, the Iranian Department of Environment estimates that only 12 Asiatic cheetahs, 9 males, and 3 females, are left in Iran.[7] In order to raise international awareness for the conservation of the Asiatic cheetah, an illustration was used on the jerseys of the Iran national football team at the 2014 FIFA World Cup.[8]

Felis venatica was proposed by Edward Griffith in 1821 and based on a sketch of a maneless cheetah from India.[9] Griffith's description was published in Le Règne Animal with the help of Griffith's assistant Charles Hamilton Smith in 1827.[10]

Acinonyx raddei was proposed by Max Hilzheimer in 1913 for the cheetah population in Central Asia, the Trans-Caspian cheetah. Hilzheimer's type specimen originated in Merv, Turkmenistan.[11]

Results of a five-year phylogeographic study on cheetah subspecies indicate that Asiatic and African cheetah populations separated between 32,000 and 67,000 years ago and are genetically distinct. Samples of 94 cheetahs for extracting mitochondrial DNA were collected in nine countries from wild, seized and captive individuals and from museum specimen. The population in Iran is considered autochthonous monophyletic and the last remaining representative of the Asiatic subspecies.[3] Mitochondrial DNA fragments of an Indian and a Southeast African cheetah museum specimens showed that they genetically diverged about 72,000 years ago.[12]

The Asiatic cheetah has a buff-to-light fawn-coloured fur that is paler on the sides, on the front of the muzzle, below the eyes and inner legs. Small black spots are arranged in lines on the head and nape, but irregularly scattered on body, legs, paws and tail. The tail tip has black stripes. The coat and mane are shorter than of African cheetah subspecies.[13] The head and body of an adult Asiatic cheetah measure about 112–135 cm (44–53 in) with a 66–84 cm (26–33 in) long tail. It weighs about 34–54 kg (75–119 lb). They exhibit sexual dimorphism; males are slightly larger than the females.[14]

The cheetah is the fastest land animal in the world.[15] It was previously thought that the body temperature of a cheetah increases during a hunt due to high metabolic activity.[16] In a short period of time during a chase, a cheetah may produce 60 times more heat than at rest, with much of the heat, produced from glycolysis, stored to possibly raise the body temperature. The claim was supported by data from experiments in which two cheetahs ran on a treadmill for minutes on end but contradicted by studies in natural settings, which indicate that body temperature stays relatively the same during a hunt. A 2013 study suggested stress hyperthermia and a slight increase in body temperature after a hunt.[17] The cheetah's nervousness after a hunt may induce stress hyperthermia, which involves high sympathetic nervous activity and raises the body temperature. After a hunt, the risk of another predator taking its kill is great, and the cheetah is on high alert and stressed.[18] The increased sympathetic activity prepares the cheetah's body to run when another predator approaches. In the 2013 study, even the cheetah that did not chase the prey experienced an increase in body temperature once the prey was caught, showing increased sympathetic activity.[17]

The cheetah thrives in open lands, small plains, semi-desert areas, and other open habitats where prey is available. The Asiatic cheetah mainly inhabits the desert areas around Dasht-e Kavir in the eastern half of Iran, including parts of the Kerman, Khorasan, Semnan, Yazd, Tehran, and Markazi provinces. Most live in five protected areas, viz Kavir National Park, Touran National Park, Bafq Protected Area, Dar-e Anjir Wildlife Refuge, and Naybandan Wildlife Reserve.[4]

During the 1970s, the Asiatic cheetah population in Iran was estimated to number about 200 individuals in 11 protected areas. By the end of the 1990s, the population was estimated at 50 to 100 individuals.[19][20] During camera-trapping surveys conducted across 18 protected areas between 2001 and 2012, a total of 82 individuals in 15–17 families were recorded and identified. Of these, only six individuals were recorded for more than three years. In this period, 42 cheetahs died due to poaching, in road accidents and due to natural causes. Populations are fragmented and known to survive in the Semnan, North Khorasan, South Khorasan, Yazd, Esfahan, and Kerman Provinces.[5]

In summer 2018, a female cheetah and four cubs were sighted in Touran Wildlife Refuge Iran's Semnan province.[21]

The Asiatic cheetah once ranged from the Arabian Peninsula and Near East to Iran, the Caucasus, Central Asia, Afghanistan and Pakistan to India.[23] Bronze Age remains are known from Anatolia as far west as Troy,[24] and Armenia.[25] It is considered regionally extinct in all of its former range, with the only known surviving population being Iran.[26]

In Iraq, the cheetah was still recorded in the desert west of Basrah in 1926. The last record was published in 1991, and it was a cheetah that had been killed by a car. In the Sinai peninsula, a sighting of two cheetahs was reported in 1946. In the Arabian Peninsula, it used to occur in the northern and southeastern fringes and had been reported in both Saudi Arabia and Kuwait before 1974.[27] Two cheetahs were killed in the northern Saudi Ha'il Region in 1973.[28] In Yemen, the last known cheetah was sighted in Wadi Mitan in 1963, near the international border with Oman. In Oman's Dhofar Mountains, a cheetah was shot near Jibjat in 1977.[27]

In Central Asia, uncontrolled hunting of cheetahs and their prey, severe winters and conversion of grassland to areas used for agriculture contributed to the population's decline. By the early 20th century, the range in Central Asia had decreased significantly.[11] By the 1930s, cheetahs were confined to the Ustyurt plateau and Mangyshlak Peninsula in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, and to the foothills of the Kopet Dag mountains and a region in the south of Turkmenistan bordering Iran and Afghanistan. The last known sightings in the area were in 1957 between the Tejen and Murghab Rivers, in July 1983 in the Ustyurt plateau, and in November 1984 in the Kopet Dag.[29] Officers of the Badhyz State Nature Reserve did not sight a cheetah in this area until 2014; the border fence between Iran and Turkmenistan might impede dispersal.[30]

The cheetah population in Afghanistan decreased to the extent that it has been considered extinct since the 1950s.[31] Two skins were sighted in markets in the country, one in 1971, and another in 2006, the latter reportedly from Samangan Province.[32]

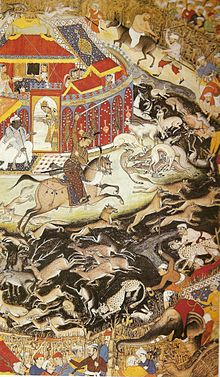

In India, the cheetah occurred in Rajputana, Punjab, Sind, and south of the Ganges from Bengal to the northern part of the Deccan Plateau. It was also present in the Kaimur District, Darrah and other desert regions of Rajasthan and parts of Gujarat and Central India.[13] Akbar the Great was introduced to cheetahs around the mid-16th century and used them for coursing blackbucks, chinkaras and antelopes. He allegedly possessed 1,000 cheetahs during his reign but this figure might be exaggerated since there is no evidence of housing facilities for so many animals, nor of facilities to provide them with sufficient meat every day.[33] Trapping of adult cheetahs, who had already learned hunting skills from wild mothers, for assisting in royal hunts is said to be another major cause of the species' rapid decline in India, as there is only one record of a litter ever born to captive animals. By the beginning of the 20th century, wild Asiatic cheetahs sightings were rare in India, so much so that between 1918 and 1945, Indian princes imported cheetahs from Africa for coursing. Three of India's last cheetahs were shot by the Maharajah of Surguja in 1948. A female was sighted in 1951 in Koriya district, northwestern Chhattisgarh.[22]

Most sightings of cheetahs in the Miandasht Wildlife Refuge between January 2003 and March 2006 occurred during the day and near watercourses. These observations suggest that they are most active when their prey is.[34]

Camera-trapping data obtained between 2009 and 2011 indicate that some cheetahs travel long distances. A female was recorded in two protected areas that are about 150 km (93 mi) apart and intersected by railway and two highways. Her three male siblings and a different adult male were recorded in three reserves, indicating that they have large home ranges.[35]

The Asiatic cheetah preys on medium-sized herbivores including chinkara, goitered gazelle, wild sheep, wild goat and cape hare.[36] In Khar Turan National Park, cheetahs use a wide range of habitats, but prefer areas close to water sources. This habitat overlaps to 61% with wild sheep, 36% with onager, and 30% with gazelle.[37]

In India, prey was formerly abundant. Before its extinction in the country, the cheetah fed on the blackbuck, the chinkara, and sometimes the chital and the nilgai.[38]

Evidence of females successfully raising cubs is very rare. A few observations in Iran indicate that they give birth throughout the year to one to four cubs. In April 2003, four cubs found in a den had still closed eyes. In November 2004, a cub was recorded by a camera-trap that was about 6–8 months old. Breeding success depends on availability of prey.[34] In October 2013, a female with four cubs were filmed in Khar Turan National Park.[39] In December 2014, four cheetahs were sighted and photographed by camera traps in the same national park.[40] In January 2015, three other adult Asiatic cheetahs and a female with her cub were sighted in Miandasht Wildlife Refuge.[41] Eleven cheetahs were also sighted at the time, and another four a month later.[42] In July 2015, five adult cheetahs and three cubs were spotted in Khar Turan National Park.[43]

The Asiatic cheetah has been listed as Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List since 1996.[1] Following the Iranian Revolution of 1979, wildlife conservation was interrupted for several years. Manoeuvres with armed vehicles were carried in steppes, and local people hunted cheetahs and prey species unchecked. The gazelle population declined in many areas, and cheetahs retreated to remote mountainous habitats.[4][34]

Reduced gazelle numbers, persecution, land-use change, habitat degradation and fragmentation, and desertification contributed to the decline of the cheetah population.[19][44] The cheetah is affected by loss of prey as a result of antelope hunting and overgrazing from introduced livestock. Its prey was pushed out as herders entered game reserves with their herds.[36] A herder pursued a female cheetah with two cubs on his motorbike, until one of the cubs was so exhausted that it collapsed. He caught and kept it chained in his home for two weeks, until it was rescued by officers of the Iranian Department of Environment.[45]

Mining development and road construction near reserves also threaten the population.[19] Coal, copper, and iron have been mined in cheetah habitat in three different regions in central and eastern Iran. It is estimated that the two regions for coal (Nayband) and iron (Bafq) have the largest cheetah population outside protected areas. Mining itself is not a direct threat to the population; road construction and the resulting traffic have made the cheetah accessible to humans, including poachers. The Iranian border regions to Afghanistan and Pakistan, viz the Baluchistan Province, are major passages for armed outlaws and opium smugglers who are active in the central and western regions of Iran, and pass through cheetah habitat. Uncontrolled hunting throughout the desert cannot be effectively controlled by the governments of the three countries.[19]

Conflict between livestock herders and cheetahs is also threatening the population outside protected areas. Several herders killed cheetahs to prevent livestock loss, or for trophies, trade and fun.[44] Some herders are accompanied by large mastiff-type dogs into protected areas. These dogs killed five cheetahs between 2013 and 2016.[46]

Between 2007 and 2011, six cheetahs, 13 predators and 12 Persian gazelles died in Yazd Province following collisions with vehicles on a transit road.[47] At least 11 Asiatic cheetahs were killed in road accidents between 2001 and 2014.[48] The road network in Iran constitutes a very high risk for the small population as it impedes connectivity between population units.[49] Efforts to stop the construction of a road through the core of the Bafq Protected Area were unsuccessful.[50] Between 1987 and 2018, 56 cheetahs died in Iran because of humans; 26 were killed by herders or their dogs.[51]

In September 2001, the project "Conservation of the Asiatic Cheetah and its Associated Biota" was launched by the Iranian Department of Environment in cooperation with the United Nations Development Programme's Global Environment Facility, the Wildlife Conservation Society, the IUCN Cat Specialist Group, the Cheetah Conservation Fund and the Iranian Cheetah Society.[4]

Personnel of Wildlife Conservation Society and the Iranian Department of Environment started radio-collaring Asiatic cheetahs in February 2007. The cats' movements are monitored using GPS collars.[52] International sanctions have made some projects, such as obtaining camera traps, difficult.[39]

A few orphaned cubs have been raised in captivity, such as Marita who died at the age of nine years in 2003. Beginning in 2006, the day of his death, 31 August, became the Cheetah Conservation Day, used to inform the public about conservation programs.[53]

In 2014, the Iranian national football team announced that their 2014 FIFA World Cup and 2015 AFC Asian Cup kits are imprinted with pictures of the Asiatic cheetah in order to bring attention to conservation efforts.[8][54] In February 2015, Iran launched a search engine, Yooz, that features a cheetah as logo.[55] In May 2015, the Iranian Department of Environment announced plans to quintuple the penalty for poaching a cheetah to 100 million tomans (around US$2800 as of February 2022).[56][57] In September 2015, Meraj Airlines introduced the new livery of Iranian Cheetah to support its conservation efforts.[58] Iranian officials have discussed constructing wildlife crossings to reduce the number of deaths in traffic accidents.[59]

In 2014, an Asiatic cheetah was cloned for the first time by scientists from the University of Buenos Aires.[60] The embryo was not born.[61]

In February 2010, photos of an Asiatic cheetah in a "Semi-Captive Breeding and Research Center of Iranian Cheetah" in Iran's Semnan province were published.[62] Another news report stated that the centre is home to about ten Asiatic cheetahs in a semi-wild environment protected by wire fencing all around.[63]

In January 2008, a male cub aged about 7–8 months was recovered from a sheep herder and brought into captivity.[45] Wildlife officials in Miandasht Wildlife Refuge and the Turan National Park have raised a few orphaned cubs.[53] In December 2015, it was reported that 18 Asiatic cheetah cubs had recently been born at Pardisan Park.[64] In May 2022, an Asiatic cheetah gave birth to three male cubs in a facility in Iran; two died shortly after with Pirouz being the lone survivor.[65] This is the first known reproduction of the subspecies in captivity.[65] On 28 February 2023, Pirouz reportedly died in the veterinary hospital in Iran due to kidney failure.[66]

The Asiatic cheetah whose long history on the Indian subcontinent gave the Sanskrit-derived vernacular name "cheetah" to the species Acinonyx jubatus, also had a gradual history of habitat loss there. In Punjab, before the thorn forests were cleared and extensively utilized for agriculture and human settlement, they were intermixed with open grasslands grazed by large herds of blackbuck; these coexisted with their main natural predator the Asiatic cheetah.[67] The blackbuck, no longer extant in Punjab, is severely endangered in India.[67] Later, more habitat loss, prey depletion, and trophy hunting were to lead to the extinction of the Asiatic cheetah in India by the early 1950s.

The debate over whether cheetah reintroduction is compatible with the stated aims of wildlife conservation, started soon after extinction was confirmed. In 1955, the former State Wildlife Board of Andhra Pradesh proposed the reintroduction of the Asiatic cheetah in two districts of the state, on an experimental basis. In 1965, the pros and cons of reintroduction were critically discussed by M. Krishnan in a newspaper article. In 1984, Divyabhanusinh was asked to write a paper on the prospect of cheetah reintroduction in India for the Ministry of Environment and Forests. This paper was subsequently sent to the Cat Specialist Group of Species Survival Commission of the IUCN, where it sparked international interest.[68]

In the 1970s, India's Department of Environment formally wrote to the Iranian government to request Asiatic cheetahs in use for reintroduction and apparently received a positive response. The talks were stalled after the Shah of Iran was deposed in the Iranian Revolution, and the negotiations never progressed.[69] In August 2009, Jairam Ramesh, the then-Minister of Environment, rekindled the talks with Iran for sharing a few of their animals. Iran had always been hesitant to commit to the idea, given the very low numbers present in the country.[70] It is said that Iran wanted an Asiatic lion in exchange for a cheetah, and that India was not willing to export any of its lions.[71] The plan to source cheetahs from Iran was eventually dropped in 2010.[68]

Proposals for the introduction of African cheetahs were made by the Indian government in 2009, but disallowed by India's supreme court. The court reversed its decision in early 2020, allowing the import of a small number on an experimental basis for testing long-term adaptation. On 17 September 2022, five female and three male Southeast African cheetahs between ages four and six, a gift of the government of Namibia, were released in a small quarantined enclosure within the Kuno National Park in the state of Madhya Pradesh.[72] The cheetahs, all fitted with radio collars, will remain in the quarantined enclosure for a month, whereupon initially the males and later the females will be released into the 748.76 km2 (289.10 sq mi) park.[73]

The scientific reaction to the translocation has been mixed. Adrian Tordiffe, a wildlife veterinary pharmacologist at the University of Pretoria who is an enthusiast considers India to provide "protected space" for the fragmented and threatened population of the world's cheetahs.[74] K. Ullas Karanth, one of India's foremost tiger experts has been critical of the effort, considering it to be a "PR exercise," which given India's realities involves "high mortalities," and requires a continual import of African cheetahs.[75]

On 11 March 2023, a breeding pair of Southeast African cheetahs from Namibia were released in Kuno National Park.[76][77]

The Asiatic cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus venaticus) is a critically endangered cheetah subspecies currently only surviving in Iran. It once occurred from the Arabian Peninsula and the Near East to the Caspian region, Transcaucasus, Kyzylkum Desert and northern South Asia, but was extirpated in these regions during the 20th century. The Asiatic cheetah diverged from the cheetah population in Africa between 32,000 and 67,000 years ago.

The Asiatic cheetah survives in protected areas in the eastern-central arid region of Iran, where the human population density is very low. Between December 2011 and November 2013, 84 individuals were sighted in 14 different protected areas, and 82 individuals were identified from camera trap photographs. In December 2017, fewer than 50 individuals were thought to be remaining in three subpopulations that are scattered over 140,000 km2 (54,000 sq mi) in Iran's central plateau. As of January 2022, the Iranian Department of Environment estimates that only 12 Asiatic cheetahs, 9 males, and 3 females, are left in Iran. In order to raise international awareness for the conservation of the Asiatic cheetah, an illustration was used on the jerseys of the Iran national football team at the 2014 FIFA World Cup.

La Azia gepardo aŭ Azia ĉitao ("ĉitah" el Hindia चीता cītā, deriva el Sanskrita vorto ĉitraka signife "makuleca") (Acinonyx jubatus venaticus) estas gepardo, nome maula specio el la familio de Felisedoj kaj subfamilio de gepardenoj aŭ Acinonikenoj nune konata ankaŭ kiel Irana gepardo, ĉar la lastaj kelkaj konataj en la mondo estis survivantaj ĉefe en Irano. Kvankam oni supozas, ke ĝi iĝis formortinta en Barato, ĝi estas konata ankaŭ kiel Barata gepardo. Dum la britkolonia epoko en Barato ĝi estis fama laŭ la nomo de ĉasleopardo, nomo deriva el tiuj kiuj estis kaptitaj en kaptiteco multnombre fare de la barata reĝaro por uszi ilin por ĉasado de naturaj antilopoj.

El guepardo asiático (Acinonyx jubatus venaticus) (चीता Cītā) es una rara subespecie de guepardo encontrado principalmente en Irán. Es un atípico miembro de la familia de los gatos (Felidae) el cual caza principalmente utilizando su velocidad en grupo o escondiéndose. Vive en un gran desierto fragmentado y, mismo así, se extinguió recientemente en la India; es también conocido como el guepardo índico. Es el más rápido de todos los animales terrestres y puede llegar hasta velocidades de 112 km/h (70 mph). El guepardo también es conocido por su impresionante capacidad de aceleración (0 - 100 km/h en 3.5 segundos (más rápido que el Mercedes-Benz SLR McLaren, el Lamborghini Murciélago y el F/A-18 Hornet).

El guepardo asiático es una especie en peligro de extinción crítico[2]. Esta subespecie de guepardo actualmente sólo se encuentra en Irán, aunque en algunas raras ocasiones se han producido avistamientos en Baluchistán. Habita principalmente en el vasto desierto del interior de Irán, es las escasas zonas de hábitat adecuado.

El peligro de extinción del guepardo asiático se ha producido en época reciente. En siglos pasados era una especie mucho más numerosa que se extendida desde Arabia a la India, incluyendo Afganistán; actualmente se estima que sobrevive una población de entre 70-100 ejemplares, la mayoría de ellos en Irán.

El guepardo asiático se extendía originalmente desde la península arábiga hasta la India, a través de Irán y Asia Central,[2] Afganistán y Pakistán. En Irán y en la India era especialmente numerosos. Los guepardos eran domesticados y entrenados para cazar gacelas. Akbar, el emperador Mogol de la India, se dice que llegó a tener hasta 1000 guepardos, que a menudo aparecen representados en muchos miniaturas y pinturas persas e indias. Las numerosas limitaciones a la conservación del guepardo, sus complejos requisitos de conservación como su baja tasa de fertilidad, la elevada mortalidad de los cachorros debido a factores genéticos y el hecho de que sean las hembras las que elijan a los machos, han dificultado su cría en cautividad para su conservación. Un problema específico de los guepardos es su limitada reserva genética. Todos los guepardos tienen una reducida diversidad genética al parecer debido a su casi extinción hace unos 12.000 años. Los guepardos son una especie delicada y susceptible a los cambios en su entorno.[3]

A principios del siglo XX, el guepardo asiático ya se había extinguido en muchos lugares de su antigua distribución. La última evidencia física de la presencia del guepardo asiático en la India fueron tres ejemplares abatidos por el majarás de Surguja en el año 1947 al este de Madhya Pradesh. En 1990 los últimos ejemplares encontrados parecían concentrarse en Irán. Durante los años setenta existían unos 200 guepardos en Irán, pero en los últimos años el biólogo iraní Hormoz Asadi estimó que el solo quedaban entre 50 y 100 guepardos asiáticos. Entre los años 2005 y 2006 se realizó una nueva estimación que arrojó un número entre 50-60 guepardos asiáticos en libertad. La mayoría de estos 60 guepardos asiáticos viven en el desierto de Kavir en Irán. Otra población habita el terreno semidesértico en la frontera entre Irán y Pakistán. En los lugares donde se han encontrado guepardos, los habitantes locales afirman que no los han visto durante más de 15 años, lo que podría indicar la presencia de algunas poblaciones supervivientes que todavía no han sido avistadas.[4]

El 1 de Mayo de 2022, se dio a conocer que por primera vez en la historia de esta especie, una hembra dio a luz a tres cachorros de la misma estando en cautiverio.

El guepardo asiático (Acinonyx jubatus venaticus) (चीता Cītā) es una rara subespecie de guepardo encontrado principalmente en Irán. Es un atípico miembro de la familia de los gatos (Felidae) el cual caza principalmente utilizando su velocidad en grupo o escondiéndose. Vive en un gran desierto fragmentado y, mismo así, se extinguió recientemente en la India; es también conocido como el guepardo índico. Es el más rápido de todos los animales terrestres y puede llegar hasta velocidades de 112 km/h (70 mph). El guepardo también es conocido por su impresionante capacidad de aceleración (0 - 100 km/h en 3.5 segundos (más rápido que el Mercedes-Benz SLR McLaren, el Lamborghini Murciélago y el F/A-18 Hornet).

El guepardo asiático es una especie en peligro de extinción crítico[2]. Esta subespecie de guepardo actualmente sólo se encuentra en Irán, aunque en algunas raras ocasiones se han producido avistamientos en Baluchistán. Habita principalmente en el vasto desierto del interior de Irán, es las escasas zonas de hábitat adecuado.

El peligro de extinción del guepardo asiático se ha producido en época reciente. En siglos pasados era una especie mucho más numerosa que se extendida desde Arabia a la India, incluyendo Afganistán; actualmente se estima que sobrevive una población de entre 70-100 ejemplares, la mayoría de ellos en Irán.

Acinonyx jubatus venaticus

Le guépard asiatique (ou guépard iranien, guépard d'Iran, n. latin: Acinonyx jubatus venaticus) est une sous-espèce de guépards en danger critique d'extinction désormais limité à la frontière Iran-Irak, bien qu'on ait signalé quelques survivants ponctuels dans les zones rurales d'Irak, d'Iran, et du Pakistan.

Le guépard asiatique est aussi appelé guépard iranien ou guépard d'Iran.

Son nom scientifique, Acinonyx jubatus venaticus, est composé du nom générique, Acinonyx, d'une épithète spécifique, jubatus, et d'une épithète terminale, venaticus.

Le guépard asiatique a une fourrure de couleur chamois à fauve clair, plus pâle sur les côtés, sur le devant du museau, sous les yeux et à l'intérieur des pattes. De petites taches noires sont disposées en lignes sur la tête et la nuque, mais elles sont irrégulièrement dispersées sur le corps, les pattes, les pieds et la queue. L'extrémité de la queue présente des rayures noires. Le pelage et la crinière sont plus courts que ceux des guépards africains[1]. La tête et le corps d'un guépard asiatique adulte mesurent environ 112-135 cm, avec une queue longue de 66-84 cm. Il pèse environ 34-54 kg. Les mâles sont légèrement plus grands que les femelles.

Le guépard est l'animal terrestre le plus rapide au monde[2]. On pensait auparavant que la température corporelle d'un guépard augmentait pendant une chasse en raison d'une forte activité métabolique[3]. En peu de temps pendant une chasse, un guépard peut produire 60 fois plus de chaleur qu'au repos, une grande partie de la chaleur, produite par la glycolyse, étant stockée pour éventuellement augmenter la température corporelle. Cette affirmation a été étayée par des données provenant d'expériences dans lesquelles deux guépards ont couru sur un tapis roulant pendant des minutes, mais contredite par des études en milieu naturel, qui indiquent que la température corporelle reste relativement la même pendant une chasse. Une étude de 2013 suggère une hyperthermie de stress et une légère augmentation de la température corporelle après une chasse[4]. La nervosité du guépard après une chasse peut induire une hyperthermie de stress, qui implique une forte activité nerveuse sympathique et augmente la température corporelle. Après une chasse, le risque qu'un autre prédateur s'empare de sa proie est grand, et le guépard est en état d'alerte élevé et stressé[5]. L'activité sympathique accrue prépare le corps du guépard à courir lorsqu'un autre prédateur s'approche. Dans l'étude de 2013, même le guépard qui n'a pas poursuivi sa proie a connu une augmentation de la température corporelle une fois la proie capturée, montrant une activité sympathique accrue[6].[pertinence contestée]

La plupart des observations de guépards dans la Réserve naturelle de Miandasht entre janvier 2003 et mars 2006 ont eu lieu pendant la journée et près des cours d'eau. Ces observations suggèrent qu'ils sont plus actifs lorsque leurs proies le sont[7].

Les données de piégeage par caméra obtenues entre 2009 et 2011 indiquent que certains guépards se déplacent sur de longues distances. Une femelle a été enregistrée dans deux zones protégées distantes d'environ 150 km et traversées par une voie ferrée et deux autoroutes. Ses trois frères et sœurs mâles et un mâle adulte différent ont été enregistrés dans trois réserves, ce qui indique qu'ils ont de grands domaines vitaux[8].

Le guépard asiatique se nourrit d'herbivores de taille moyenne, dont le chinkara, la gazelle à goitre, le mouflon, la chèvre sauvage et le lièvre du Cap[9]. Dans la réserve de biosphère de Turan, les guépards utilisent un large éventail d'habitats, mais préfèrent les zones proches des sources d'eau. Cet habitat se chevauche à 61% avec le mouton sauvage, 36% avec l'hémione, et 30% avec la gazelle[10].

En Inde, la proie était autrefois abondante. Avant son extinction dans le pays, le guépard se nourrissait du blackbuck, du chinkara, et parfois du chital et du nilgai.

Son aire de répartition est désormais limitée à la frontière Iran-Irak, bien qu'on ait signalé quelques survivants ponctuels dans les zones rurales d'Irak, d'Iran, et du Pakistan[11].

Les résultats d'une étude phylogéographique de cinq ans sur les sous-espèces de guépards indiquent que les populations de guépards asiatiques et africaines se sont séparées il y a 32 000 à 67 000 ans et sont génétiquement distinctes. Des échantillons de 94 guépards pour l'extraction de l'ADN mitochondrial ont été prélevés dans neuf pays sur des individus sauvages, saisis et captifs et sur des spécimens de musée. La population iranienne est considérée comme monophylétique et est la dernière représentante de la sous-espèce asiatique[12].

Cette sous-espèce de guépards est en danger critique d'extinction.

Entre décembre 2011 et novembre 2013, 84 individus ont été observés dans 14 zones protégées différentes, et 82 individus ont été identifiés à partir de photos prises avec des pièges photographiques[13]. En décembre 2017, on estime qu'il reste moins de 50 individus dans trois sous-populations dispersées sur 140 000 km2 sur le plateau central de l'Iran[14]. Afin de sensibiliser la communauté internationale à la conservation du guépard asiatique, une illustration a été utilisée sur les maillots de l'équipe nationale de football iranienne lors de la Coupe du Monde de la FIFA 2014[15].

Au début des années 2000, des chercheurs et généticiens indiens ont évoqué l'idée de réintroduire l'espèce dans le pays, en utilisant une méthode avancée de clonage de guépards en provenance d'Iran[16]. Un autre programme de réintroduction, cette fois-ci basé sur l'importation de guépards africains, a quant à lui été stoppé par la Cour suprême indienne en 2012[17]. Mais le 28 janvier 2020 la Cour suprême indienne a autorisé une réintroduction expérimentale de félins en provenance d'Afrique[18]. Début mai 2022, Trois bébés guépards sont nés au centre d’élevage de guépards asiatiques de la réserve de biosphère de Turan à Téhéran, selon un communiqué de presse du 1er mai du ministère iranien de l’Environnement, malheureuisement, l'un d'entre eux est décédé le 04 mai, suite à des malformations du poumon gauche et d’une adhérence pulmonaire, selon le Dr Behrang Ekrami, vétérinaire au Centre d’élevage des félins d’Asie

Acinonyx jubatus venaticus

Le guépard asiatique (ou guépard iranien, guépard d'Iran, n. latin: Acinonyx jubatus venaticus) est une sous-espèce de guépards en danger critique d'extinction désormais limité à la frontière Iran-Irak, bien qu'on ait signalé quelques survivants ponctuels dans les zones rurales d'Irak, d'Iran, et du Pakistan.

Cheetah Asia (Acinonyx jubatus venaticus) atau yang dikenal Cheetah Iran dianggap oleh Nowell dan Jackson (1996) untuk bertahan hidup hanya di Iran. saat ini Cheetah Asia diketahui di negara Asia seperti Jazirah Arab, Pakistan, India dan wilayah Kaspia. Cheetah Asia bertahan hidup dikawasan lindung wilayah Iran bagian timur tengah dimana kepadatan populasi manusia belum begitu tinggi. Pada pertemuan November 2006 Kelompok Aksi Cheetah Wilayah Utara Afrika (NARCAG), Belbachir (2007) merekomendasikan studi genetik untuk mengklarifikasi apakah Cheetah di Aljazair (yang mungkin memiliki populasi Cheetah Sahara terbesar) harus diklasifikasikan sebagai A. j. hecki atau A. j. venaticus. Saat ini A. j. venaticus dianggap terbatas di Asia[1]

Cheetah Asia (Acinonyx jubatus venaticus) atau yang dikenal Cheetah Iran dianggap oleh Nowell dan Jackson (1996) untuk bertahan hidup hanya di Iran. saat ini Cheetah Asia diketahui di negara Asia seperti Jazirah Arab, Pakistan, India dan wilayah Kaspia. Cheetah Asia bertahan hidup dikawasan lindung wilayah Iran bagian timur tengah dimana kepadatan populasi manusia belum begitu tinggi. Pada pertemuan November 2006 Kelompok Aksi Cheetah Wilayah Utara Afrika (NARCAG), Belbachir (2007) merekomendasikan studi genetik untuk mengklarifikasi apakah Cheetah di Aljazair (yang mungkin memiliki populasi Cheetah Sahara terbesar) harus diklasifikasikan sebagai A. j. hecki atau A. j. venaticus. Saat ini A. j. venaticus dianggap terbatas di Asia

Il ghepardo asiatico (Acinonyx jubatus venaticus Griffith, 1821), noto anche come ghepardo persiano, è una sottospecie di ghepardo gravemente minacciata che attualmente sopravvive solo in Iran. In passato era presente in gran numero anche in India, dove è localmente scomparso[1].

Il ghepardo asiatico vive prevalentemente nel vasto deserto centrale dell'Iran nelle aree frammentate di habitat disponibile rimasto. Nonostante un tempo fosse molto comune, il ghepardo è stato portato all'estinzione in altre parti dell'Asia sud-occidentale dall'Arabia all'India, Afghanistan compreso. Nel 2013, in Iran sono stati identificati solamente 20 ghepardi, ma alcune aree devono ancora essere pattugliate[3][4]. La popolazione totale viene stimata tra i 40 e i 70 individui, e il 40% delle morti è dovuta ad incidenti stradali[5][6]. I tentativi di fermare la costruzione di una strada nel cuore dell'area protetta di Bafq non hanno avuto successo[6]. Al fine di sensibilizzare l'opinione pubblica internazionale sulla conservazione del ghepardo asiatico, un'immagine dell'animale è stata rappresentata sulle maglie della nazionale di calcio dell'Iran durante la Coppa del Mondo FIFA del 2014[7]. Attualmente (2015), si stima che in Iran sopravvivano circa 50 ghepardi allo stato selvatico, ma il loro numero è in aumento[8].

Il ghepardo asiatico si separò dal suo parente africano tra 32.000 e 67.000 anni fa[9]. Assieme alla lince eurasiatica e al leopardo persiano, è una delle tre specie di grandi felini rimaste in Iran[10].

Durante il periodo coloniale britannico in India veniva chiamato leopardo cacciatore, poiché l'animale veniva tenuto in cattività in gran numero dai nobili indiani per essere utilizzato nella caccia alle antilopi selvatiche[11]. In olandese, il ghepardo viene ancora chiamato jachtluipaard. Il nome con cui esso è noto presso gli anglosassoni, cheetah, deriva dalla parola hindi cītā (चीता), a sua volta derivata dal sanscrito chitraka, che significa «macchiato».

Rispetto ai loro cugini africani, i ghepardi asiatici hanno una costituzione più slanciata, una colorazione più chiara e una lunghezza leggermente inferiore[12]. Gli esemplari adulti hanno una lunghezza testa-corpo di 112–135 cm e una coda lunga 66–84 cm. Il peso si aggira sui 34–54 kg. I maschi sono leggermente più grandi delle femmine.

Il ghepardo è l'animale terrestre più veloce[13]. In passato si riteneva che la temperatura corporea dell'animale aumentasse durante la caccia a causa dell'elevata attività metabolica[14]. Nel breve periodo di tempo di un inseguimento, un ghepardo può produrre 60 volte più calore che a riposo, e gli studiosi credevano che gran parte di questo calore, prodotto dalla glicolisi, una volta immagazzinato andasse ad aumentare eventualmente la temperatura corporea. Questa teoria trovava conferma nei dati ricavati da esperimenti in cui due ghepardi venivano fatti correre per alcuni minuti su un tapis roulant, ma è stata contraddetta da studi effettuati in natura che indicano che la temperatura corporea rimane relativamente la stessa durante una caccia. Secondo uno studio del 2013 l'animale, dopo una caccia, va incontro ad ipertermia da stress e a un leggero aumento della temperatura corporea[15]. Il nervosismo del ghepardo dopo una battuta di caccia può indurre ipertermia da stress, che comporta un'elevata attività del sistema nervoso simpatico e l'aumento della temperatura corporea. Dopo una caccia, il rischio che un altro predatore si impossessi della preda catturata è elevato e il ghepardo rimane vigile e agitato[16]. L'innalzamento dell'attività simpatica prepara il corpo del ghepardo a una possibile fuga nel caso si avvicini un altro predatore. Nel corso dello studio del 2013, anche il ghepardo che non era stato costretto a inseguire la preda andò incontro ad un aumento della temperatura corporea una volta che questa era stata catturata, mostrando un incremento dell'attività simpatica[15].

I ghepardi vivono in zone aperte, pianeggianti e semidesertiche, e in altri habitat aperti ove vi sia disponibilità di prede. Il ghepardo asiatico è diffuso soprattutto nelle aree desertiche attorno al Dasht-e Kavir nella metà orientale dell'Iran, comprendenti parti delle province di Kerman, Khorasan, Semnan, Yazd, Teheran e Markazi. La maggior parte di essi vive in cinque santuari: il parco nazionale di Kavir, il parco nazionale di Khar Turan, l'area protetta di Bafq, la riserva naturale di Daranjir e il parco nazionale di Nayband[17]. I ghepardi rimanenti sono suddivisi in popolazioni molto distanziate. Alcuni esemplari forse sopravvivono nelle zone aride e pianeggianti della provincia pakistana del Belucistan, ma i locali sostengono di non vederli da più di quindici anni[18].

Negli anni '70, il numero dei ghepardi presenti in Iran veniva stimato a circa 200 unità presenti in sette aree protette[19]. I dati raccolti negli anni 2005-2006 suggerivano l'esistenza in natura di 50-60 ghepardi. Per stimare l'entità della popolazione sono stati effettuati continui sopralluoghi sul campo e analizzate le immagini raccolte in 12.000 nottate dalle fototrappole. Con 80 fototrappole posizionate per tutto l'altopiano del Dasht-e Kavir, i ricercatori iraniani hanno raccolto le immagini di 76 esemplari nel corso di dieci anni a partire dal 2001[3][20]. A partire dal 2011, le fototrappole hanno identificato solamente 20 esemplari in Iran, ma alcune aree non sono state coperte[3][4]. Hooman Jowkar, direttore del Conservation of Asiatic Cheetah and Its Habitat Project, affermò che «l'obiettivo delle ricerche è stato puntato solamente su specifiche aree protette; e non possibile effettuare il fototrappolaggio in autunno e in inverno, quando il ghepardo è fisicamente più attivo»[3]. Nel novembre 2013, Morteza Eslami, a capo della Iranian Cheetah Society (ICS), affermò che rimanevano in tutto 40-70 ghepardi[5][6].

Nel dicembre 2014, quattro ghepardi furono avvistati e fotografati dalle fototrappole nel parco nazionale di Khar Turan[21]. Nello stesso periodo furono avvistati anche undici ghepardi e altri quattro un mese dopo[22]. E nel luglio 2015, otto nuovi ghepardi (cinque adulti e tre cuccioli) sono stati localizzati a Khar Turan[23].

I ghepardi asiatici un tempo erano presenti dalla penisola arabica all'India, attraverso Iran, Asia centrale, Afghanistan e Pakistan[25]. La popolazione presente in Turchia era già scomparsa nel XIX secolo[26]. In Afghanistan, i ghepardi asiatici sono considerati estinti dagli anni '50[27].

In India, i ghepardi asiatici erano presenti nel Rajputana, nel Punjab, nel Sind e, a sud del Gange, dal Bengala fino alla parte settentrionale dell'altopiano del Deccan. I ghepardi asiatici erano presenti anche in altre parti dell'India, quali il distretto di Kaimur (nell'attuale Uttar Pradesh orientale, nei pressi del Bihar), a Darrah e in altre regioni desertiche del Rajasthan e in alcune parti del Gujarat e dell'India centrale[28]. Akbar il Grande, che regnò attorno alla metà del XVI secolo, era un grande appassionato di ghepardi; li utilizzava per inseguire antilopi cervicapra, chinkara e antilopi quadricorne. Si racconta che nel corso del suo regno avesse posseduto 1000 ghepardi, ma tale numero è con tutta probabilità esagerato, dal momento che non vi è alcuna prova della presenza di strutture abitative per così tanti animali, né di servizi che li rifornissero di carne a sufficienza ogni giorno[29]. Agli inizi del XX secolo, i ghepardi asiatici selvatici erano divenuti così rari in India, che tra il 1918 e il 1945 i principi indiani furono costretti ad importare ghepardi dall'Africa per i loro passatempi venatori. Gli ultimi tre ghepardi in India vennero abbattuti dal maragià di Surguja nel 1948. Una femmina venne avvistata nel distretto di Koriya nel 1951[24].

In Asia centrale, la caccia incontrollata ai ghepardi asiatici e alle loro prede, i rigidi inverni e la conversione delle praterie in aree a utilizzo agricolo contribuirono al declino della specie. L'ultimo avvistamento registrato in Uzbekistan risale alla fine del 1983 e l'ultima uccisione registrata in Turkmenistan al novembre 1984[25].

Le femmine, diversamente dai maschi, non si insediano in un territorio ma si spostano in continuazione attraverso il loro habitat, migrando talvolta su lunghe distanze[30]. Le immagini scattate dalle fototrappole hanno mostrato una femmina che si è spostata per 130 km, un tragitto lungo il quale ha dovuto attraversare una ferrovia e due grandi strade[30].

Il ghepardo asiatico cattura prevalentemente piccole antilopi. In Iran, la sua dieta è costituita soprattutto da gazzelle jebeer (note anche come chinkara), gazzelle subgutturose, pecore selvatiche, capre selvatiche e lepri del Capo. La principale minaccia per la specie è la scomparsa delle sue prede principali dovuta al bracconaggio e alla competizione per i pascoli con il bestiame domestico. Uno studio pubblicato nel 2012 indica che lepri e roditori, nonostante facciano parte della dieta del ghepardo, non costituiscono una sua parte significativa a causa delle piccole dimensioni e della difficoltà nel catturarli[31].

In India, in passato, le prede di questo animale erano molto numerose. Prima della sua scomparsa nel Paese, il ghepardo si nutriva di antilopi cervicapre e chinkara e, talvolta, di cervi pomellati e nilgau.

«...è presente nelle basse e isolate colline rocciose, vicino alle pianure in cui vivono le antilopi, la sua principale preda. Uccide anche gazzelle, nilgau e, senza dubbio, occasionalmente cervi e altri animali. Si parla anche di esemplari che hanno portato via pecore e capre, ma raramente molesta gli animali domestici, e non si ha notizia di attacchi agli uomini. Il modo che impiega per catturare la preda consiste nell'avvicinarsi cautamente fino a una distanza di cento-duecento iarde, approfittando degli avvallamenti del terreno, dei cespugli o di altre coperture, per poi lanciarsi all'inseguimento. La sua velocità sulla breve distanza è notevolmente di gran lunga superiore a quella di qualsiasi altro animale da preda, perfino di quella dei levrieri e dei segugi da canguro, in quanto nessun cane riesce a superare un'antilope indiana o una gazzella, ciascuna delle quali viene raggiunta rapidamente da C. jubatus, se questo inizia l'inseguimento da duecento iarde di distanza o meno. Il generale McMaster vide un leopardo cacciatore molto abile catturare un'antilope cervicapra iniziando l'inseguimento da quattrocento iarde. È probabile che sulla breve distanza il leopardo cacciatore sia il più veloce tra tutti gli animali.»

(Brano di Blanford sul ghepardo asiatico dell'India citato da Lydekker[11])Le testimonianze di madri che riescono ad allevare con successo i propri cuccioli sono molto rare. Nel maggio 2013, le immagini riprese da una fototrappola mostrarono una madre con tre cuccioli dall'apparente età di un anno nella riserva naturale di Miandasht nell'Iran nord-orientale[32]. Nell'ottobre 2013, i conservazionisti della Persian Wildlife Heritage Foundation filmarono una madre con quattro cuccioli nel parco nazionale di Khar Turan[33]. Il 7 gennaio 2015, il direttore generale del Dipartimento di Protezione Ambientale del Khorasan settentrionale, Ali Asghar Motahari, ha annunciato l'avvistamento di una femmina e del suo cucciolo nella riserva naturale di Miandasht. Lo stesso Motahari ha riferito che, due giorni prima di questo avvistamento, tre altri ghepardi adulti erano stati avvistati ad alcuni chilometri di distanza dal confine orientale della riserva dai locali, che hanno immediatamente avvisato il Dipartimento dell'Ambiente di Jajrom[34].

Il ghepardo asiatico è stato considerato una sottospecie di ghepardo per molto tempo. Nel settembre 2009, Stephen J. O'Brien del Laboratory of Genomic Diversity del National Cancer Institute dichiarò che esso è geneticamente identico al ghepardo africano e che le due popolazioni si separarono circa 5000 anni fa, un lasso di tempo troppo breve per garantire una differenziazione a livello sottospecifico[35][36].

Al contrario, i risultati di una ricerca genetica durata cinque anni che ha comportato l'analisi di campioni di DNA prelevati da esemplari in natura, animali ospitati negli zoo e campioni museali provenienti da otto Paesi indicano che i ghepardi africani e asiatici sono geneticamente distinti. I confronti delle sequenze molecolari suggeriscono che essi si separarono tra 32.000 e 67.000 anni fa e che la differenziazione sottospecifica ha avuto il tempo di attuarsi. Le popolazioni presenti in Iran sono considerate gli ultimi rappresentanti rimasti del lignaggio del ghepardo asiatico[9][37].

La caccia, la riduzione del numero delle gazzelle, il cambiamento di utilizzo del terreno, il degrado e la frammentazione dell'habitat e la desertificazione hanno contribuito al declino del ghepardo[19]. Secondo il Dipartimento dell'Ambiente dell'Iran il peggioramento della situazione è avvenuto soprattutto tra il 1988 e il 1991. La riduzione del numero delle prede è una conseguenza del sovrapascolo causato dal bestiame introdotto e della caccia alle antilopi. Le prede si allontanano quando i pastori penetrano con le loro mandrie all'interno delle riserve di caccia[31].

Anche lo sfruttamento minerario e la costruzione di strade in prossimità delle riserve sono una minaccia per questi felini[19]. Carbone, rame e ferro sono stati estratti in tre diverse regioni dell'habitat del ghepardo nelle zone centrali e orientali dell'Iran. Si stima che le due regioni in cui vengono estratti carbone (Nayband) e ferro (Bafq) ospitino le popolazioni di ghepardo più numerose al di fuori delle aree protette. Lo sfruttamento minerario in sé non costituisce una minaccia diretta per i ghepardi, ma la costruzione di strade e il traffico che ne risulta hanno reso l'habitat del ghepardo accessibile agli esseri umani, bracconieri compresi. Attraverso le regioni di confine con l'Afghanistan e il Pakistan (provincia del Belucistan) passano i sentieri percorsi da fuorilegge armati e trafficanti d'oppio, attivi nelle regioni centrali e occidentali dell'Iran. Secondo quanto affermò Asadi nel 1997, la fauna di questa regione desertica ha sofferto una caccia incontrollata da parte di gruppi armati che i governi dei tre Paesi non sono riusciti a tenere sotto controllo[19]. Riguardo alla situazione attuale della specie nella regione non vi sono dati disponibili.

Attualmente in Iran vivono tra i 40 e i 70 ghepardi asiatici. Morteza Eslami, a capo della Iranian Cheetah Society (ICS), confessò a Trend News Agency nel novembre 2013 che la sopravvivenza dell'animale è tutt'altro che assicurata[6]. Nel 2012-13, due terzi delle morti dei ghepardi avvennero a causa di incidenti stradali[6][38]. I tentativi di fermare la costruzione di una strada nel cuore dell'area protetta di Bafq non hanno avuto successo[6]. Nel febbraio 2015, è stato affermato che gli incidenti stradali sono i responsabili del 40% dei decessi[5].

Occasionalmente i ghepardi, sia cuccioli che adulti, possono essere attaccati e uccisi da predatori più grandi, come leopardi, lupi e iene striate, ma questo incide marginalmente sulla sopravvivenza della specie.

Il ghepardo asiatico viene oggi considerato gravemente minacciato dalla Lista Rossa degli Animali Minacciati della IUCN. In seguito alla rivoluzione iraniana del 1979, non è stata data molta importanza alla conservazione della natura[39], ma negli ultimi anni l'Iran ha portato avanti vari programmi per cercare di preservare la popolazione rimanente. Il Dipartimento dell'Ambiente dell'Iran, il Programma delle Nazioni Unite per lo sviluppo (UNDP) e il Fondo mondiale per l'ambiente (GEF) hanno lanciato il Conservation of the Asiatic Cheetah Project (CACP), istituito per preservare e riabilitare le aree ancora popolate da questa specie in Iran[40]. Alcuni sopralluoghi effettuati da Asadi nella seconda metà del 1997 hanno indicato che per far sì che il ghepardo asiatico possa sopravvivere, è necessario riabilitare le popolazioni di altre specie, in particolare le gazzelle, e l'habitat dell'animale.

La Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) e il Dipartimento dell'Ambiente dell'Iran (DoE) intrapresero un programma di monitoraggio tramite radiocollari nell'autunno del 2006[41][42]. Questi appositi collari GPS forniscono informazioni sui movimenti del felino[43]. Le sanzioni internazionali hanno reso alcune semplici azioni, come procurarsi delle fototrappole, alquanto difficile[33].

Nel 2006, l'Iran ha dichiarato il 31 agosto Giornata della Conservazione del Ghepardo: in questa data il pubblico viene informato sui programmi di conservazione che riguardano la specie[43][44]. Nel 2013, venne rilasciata la notizia che l'immagine del ghepardo poteva comparire sulle maglie della nazionale di calcio iraniana durante i mondiali del calcio del 2014[45]. La FIFA approvò il disegno il 1º febbraio 2014[7]. Nel maggio 2015, il Dipartimento dell'Ambiente ha annunciato piani per quintuplicare la multa per chi uccide un ghepardo a 100 milioni di toman (circa 30.000 dollari)[46].

Corsi di formazione per pastori: È stato stimato che nell'area protetta di Bafq vivano dieci ghepardi. Secondo la Iranian Cheetah Society (ICS), i pastori generalmente confondono i ghepardi con altri carnivori di simili dimensioni, quali lupi, leopardi, iene striate e perfino caracal e gatti selvatici. Sulla base dei risultati delle ricerche sul conflitto con questi animali, nel 2007 venne sviluppato un apposito corso di formazione per pastori, nel quale veniva spiegato come identificare correttamente il ghepardo e altri carnivori, dal momento che sono soprattutto questi ultimi a provocare vittime tra il bestiame. Questi corsi furono il frutto della cooperazione tra l'UNDP/GEF, il Dipartimento dell'Ambiente dell'Iran, la ICS e le comunità di cinque principali villaggi di questa regione.

Gli Amici dei Ghepardi: Un altro programma di sviluppo nella regione è stata l'istituzione degli Amici dei Ghepardi, gruppi costituiti da giovani che, dopo un breve corso istruttivo, sono in grado di educare la popolazione e organizzare eventi che hanno come tema principale il ghepardo, divenendo così un esempio di informazione in materia di ghepardi per un certo numero di villaggi. I giovani hanno manifestato un crescente interesse per la questione dei ghepardi e la conservazione di altri animali.

Conservazione ex-situ: L'India, dove il ghepardo asiatico è ormai estinto, è interessata a clonare il ghepardo per poterlo così reintrodurre nel Paese[47]. In un primo momento l'Iran - il Paese donatore - sembrava ben disposto a partecipare al progetto[48], ma successivamente si è rifiutato di inviare un maschio e una femmina di ghepardo o di consentire agli esperti di raccogliere campioni di tessuto da un ghepardo ospitato in uno zoo del Paese[49]. Nel 2009, il governo indiano ha preso in esame il progetto di reintrodurre ghepardi provenienti dall'Africa fatti riprodurre in cattività[50].

Nel 2014, un ghepardo asiatico è stato clonato per la prima volta da alcuni scienziati dell'università di Buenos Aires[51]. L'embrione, tuttavia, non è nato[52].

Nel febbraio 2010, l'Agenzia di stampa Mehr e Payvand Iran News rilasciarono le foto di un ghepardo asiatico in quello che sembrava un grosso recinto di rete metallica all'interno dell'habitat naturale della specie; nell'articolo veniva indicato che le foto erano state scattate in un «Centro di Ricerca e Riproduzione in Semi-cattività» nella provincia di Semnan. L'esemplare ritratto era ricoperto dal manto invernale, costituito da peli più lunghi[53]. Un'altra notizia riportata indicava che il centro ospita circa dieci ghepardi asiatici in un ambiente semi-selvaggio protetto tutto intorno da reti metalliche[54].

I guardaparco della riserva naturale di Miandasht e del parco nazionale di Khar Turan hanno allevato alcuni cuccioli orfani[43][55]. Nel maggio 2014, i funzionari hanno affermato di voler mettere insieme una coppia di esemplari adulti nella speranza che possano dar vita a dei cuccioli, pur riconoscendo che la specie non si riproduce facilmente in cattività[55].

Nel marzo 2015, una coppia di ghepardi adulti facenti parte di un programma di riproduzione in cattività è stata trasferita nei pressi della Torre Milad a Teheran[56].

I ghepardi hanno vissuto in India per moltissimo tempo, ma la caccia e altri fattori hanno portato alla loro scomparsa nel Paese negli anni '40. Recentemente il governo indiano ha preso in esame la proposta di reintrodurre in natura questi animali. In un articolo comparso a pagina 11 su Times of India di venerdì 9 luglio 2009, si parlava del progetto di importare alcuni ghepardi in India, dove sarebbero stati fatti riprodurre in cattività. Il ministro dell'ambiente e delle foreste, Jairam Ramesh, affermò il 7 luglio 2009 alla Rajya Sabha - il consiglio degli stati del Parlamento indiano - che «il ghepardo è l'unico animale dichiarato estinto in India nel corso degli ultimi 100 anni. Dobbiamo portarne alcuni dall'estero e ripopolare la specie». Ad esso rispose Rajiv Pratap Rudy del Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP): «Il progetto di riportare il ghepardo nel Paese, vittima della caccia indiscriminata e di altre cause, quali la difficoltà di far riprodurre la specie in cattività, è piuttosto audace, visti già i problemi che affliggono la conservazione della tigre». Due naturalisti, Divya Bhanusinh e M. K. Ranjit Singh, suggerirono l'idea di importare dei ghepardi sudafricani dalla Namibia. Secondo il piano, essi sarebbero stati fatti riprodurre in cattività in India e poi rilasciati in natura.

Nel settembre 2009, ad un seminario sulla reintroduzione del ghepardo tenutosi in India, Stephen J. O'Brien affermò che i ghepardi africani e quelli asiatici sono geneticamente identici e che si sono separati solamente 5000 anni fa. Nella stessa occasione l'esperta di ghepardi Laurie Marker del Cheetah Conservation Fund (CCF) e altri studiosi consigliarono al governo indiano che era meglio far arrivare dei ghepardi dall'Africa, dove sono molto più numerosi, invece di cercare di ottenere alcuni dei rarissimi esemplari selvatici dall'Iran. Al seminario parteciparono inoltre il ministro indiano dell'ambiente e delle foreste, Jairam Ramesh, capi guardacaccia di Rajasthan, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh e Chhattisgarh, funzionari del ministero dell'ambiente, esperti di ghepardi di tutto il globo, rappresentanti del Wildlife Institute of India (WII) tra cui Yadvendradev Jhala, della IUCN e dell'organizzazione ambientalista NGO. La conferenza venne organizzata dal Wildlife Trust of India (WTI)[35][36].

Nel maggio 2012, la corte suprema indiana ha sospeso i tentativi di introdurre ghepardi africani nel Paese a seguito della pubblicazione di più recenti studi genetici, secondo i quali ghepardi asiatici e africani si separarono tra 32.000 e 67.000 anni fa. Nel 2021 è iniziato un nuovo progetto dove 8 ghepardi verranno reintrodotti in India nel loro areale originario.[57].

Nel 2014, la nazionale di calcio dell'Iran annunciò che durante la Coppa del Mondo FIFA del 2014 e la Coppa delle nazioni asiatiche del 2015 sulle maglie sarebbe stata impressa un'immagine dell'animale al fine di sensibilizzare l'opinione pubblica internazionale sulla conservazione della specie[7]. Nel febbraio 2015, l'Iran ha lanciato un motore di ricerca, Yooz, che ha come logo un ghepardo[58].

Il ghepardo asiatico (Acinonyx jubatus venaticus Griffith, 1821), noto anche come ghepardo persiano, è una sottospecie di ghepardo gravemente minacciata che attualmente sopravvive solo in Iran. In passato era presente in gran numero anche in India, dove è localmente scomparso.

Il ghepardo asiatico vive prevalentemente nel vasto deserto centrale dell'Iran nelle aree frammentate di habitat disponibile rimasto. Nonostante un tempo fosse molto comune, il ghepardo è stato portato all'estinzione in altre parti dell'Asia sud-occidentale dall'Arabia all'India, Afghanistan compreso. Nel 2013, in Iran sono stati identificati solamente 20 ghepardi, ma alcune aree devono ancora essere pattugliate. La popolazione totale viene stimata tra i 40 e i 70 individui, e il 40% delle morti è dovuta ad incidenti stradali. I tentativi di fermare la costruzione di una strada nel cuore dell'area protetta di Bafq non hanno avuto successo. Al fine di sensibilizzare l'opinione pubblica internazionale sulla conservazione del ghepardo asiatico, un'immagine dell'animale è stata rappresentata sulle maglie della nazionale di calcio dell'Iran durante la Coppa del Mondo FIFA del 2014. Attualmente (2015), si stima che in Iran sopravvivano circa 50 ghepardi allo stato selvatico, ma il loro numero è in aumento.

Il ghepardo asiatico si separò dal suo parente africano tra 32.000 e 67.000 anni fa. Assieme alla lince eurasiatica e al leopardo persiano, è una delle tre specie di grandi felini rimaste in Iran.

Durante il periodo coloniale britannico in India veniva chiamato leopardo cacciatore, poiché l'animale veniva tenuto in cattività in gran numero dai nobili indiani per essere utilizzato nella caccia alle antilopi selvatiche. In olandese, il ghepardo viene ancora chiamato jachtluipaard. Il nome con cui esso è noto presso gli anglosassoni, cheetah, deriva dalla parola hindi cītā (चीता), a sua volta derivata dal sanscrito chitraka, che significa «macchiato».

Azijinis gepardas (Acinonyx jubatus venaticus) – katinių (Felidae) šeimos, gepardų (Acinonyx jubatus) rūšies, plėšriųjų žinduolių porūšis. Šiuo metu yra grėsmingai nykstantys, gyvena tik Irane, nors ankščiau buvo aptinkami Arabijos pusiasalyje, Kaspijos regione, Kyzilkumų dykumoje, Pakistane ir Indijoje, bet ten išnyko XX a. pradžioje.

Irano vyrų futbolo rinktinė, siekdama atkreipti dėmesį į šios rūšies nykimą, 2014 m. pasaulio futbolo čempionate vilkėjo marškinėlius, kuriuose buvo matomas šių gepardų atvaizdas.

Azijinis gepardas (Acinonyx jubatus venaticus) – katinių (Felidae) šeimos, gepardų (Acinonyx jubatus) rūšies, plėšriųjų žinduolių porūšis. Šiuo metu yra grėsmingai nykstantys, gyvena tik Irane, nors ankščiau buvo aptinkami Arabijos pusiasalyje, Kaspijos regione, Kyzilkumų dykumoje, Pakistane ir Indijoje, bet ten išnyko XX a. pradžioje.

Irano vyrų futbolo rinktinė, siekdama atkreipti dėmesį į šios rūšies nykimą, 2014 m. pasaulio futbolo čempionate vilkėjo marškinėlius, kuriuose buvo matomas šių gepardų atvaizdas.

Āzijas gepards (Acinonyx jubatus venaticus) ir viena no gepardu (Acinonyx jubatus) pasugām. To sauc arī par Irānas gepardu jeb Indijas gepardu. Laikā, kad Indija bija britu kolonija, to sauca arī par medību leopardu.

Āzijas gepardu pasugas izdzīvošana ir ļoti apdraudēta. To mūsdienās var sastapt tikai Irānā un nelielā daudzumā Pakistānā Beludžistānas provincē.[1] Indijā pēdējais Āzijas gepards tika nošauts 1947. gadā, lai gan Indijas valdniekam Akbaram Lielajam 16. gadsimtā piederēja vairāk kā 9000 gepardu.

Tas dzīvo Irānas tuksnešainajos apvidos, un tā populācija ir sadrumstalota. Kādreiz šo geparda pasugu varēja sastapt, sākot ar Ziemeļāfriku, Arābiju un beidzot ar Indiju un Afganistānu. Pēdējo 10 gadu novērojumi tuksnesī liecina, ka šobrīd savvaļā varētu dzīvot 70 - 100 Āzijas gepardu. Apmēram 60 gepardu dzīvo Daštekavira tuksnesī. Āzijas gepards un Persijas leopards ir pēdējās lielo kaķu sugas, kas izdzīvojušas Irānā līdz mūsdienām. Kādreiz tik bieži sastopamais Kaspijas tīģeris un Āzijas lauva ir izmiruši pagājušā gadsimtā. Par Āzijas gepardu izmiršanas galvenajiem iemesliem uzskata: medījuma izzušana, teritoriju samazināšanās, vājš ģenētiskais materiāls, gepardu medības kažokādas ieguvei un gepardu izķeršana, lai pieradinātu un lietotu kā medību suņus.[2]

Angļu valodā gepards ir "cheetah", kas cēlies no indiešu valodas geparda apzīmējuma "chitraka" - plankumainais.[3]

Āzijas gepards tāpat kā citi gepardi ir ar slaidu ķermeni un garām kājām, un nagus spēj ievilkti tikai daļēji. Galva ir neliela, acis augstu novietotas sejā. No acu iekšējiem kaktiņiem līdz mutes kaktiņam stiepjas melna līnija, kas absorbē saules gaismu un ļauj gepardam labāk saskatīt medījumu. Kažoks ir gaiši dzeltenīgi brūns. Atšķirībā no Āfrikas gepardiem Āzijas geparda melnie pleķīši ir mazāki. Otra atšķirība ir tā, ka astes gals parasti ir nevis balts, bet melns ar dažām baltām spalvām.[4] Āzijas geparda ķermeņa garums ir 112 - 135 cm, astes garums 66 – 84 cm, augstums skaustā 81 cm, svars 39 - 65 kg.[5] Tēviņi ir nedaudz lielāki par mātītēm.

Āzijas gepards ir aktīvs dienā un galvenokārt medī Indijas gaceles (Gazella bennettii), Persijas gaceles (Gazella subgutturosa), Tibetas savvaļas aitas (Ovis aries orientalis), savvaļas kazas (Capra aegagrus) un brūnos zaķus (Lepus capensis).

Par Āzijas gepardu vairošanos nav daudz novērojumu, bet pastāv uzskats, ka visbiežāk mazuļi dzimst ziemas vidū, lai gan gepardi mēdz vairoties visu gadu. Parasti piedzimst 2 mazuļi, bet var būt arī 1 līdz 4. Dzimumbriedumu Āzijas gepards sasniedz 18 mēnešu vecumā.[3] Dzīves garums savvaļā 12 - 14 gadi.

Gepardi kopumā un īpaši Āzijas gepardi ir apdraudēti arī no ģenētikas viedokļa. To ģenētiskā variatāte ir ļoti neliela. Pamatproblēma ir tā, ka gepardu priekšteči pirms dažiem tūkstošiem gadu ir bijuši tikai daži dzīvnieki, no kuriem ir cēlusies mūsdienu populācija. Tādēļ gepardu mazuļiem ir ļoti augsta mirstība. Āzijas gepardiem šī problēma kļūst vēl nopietnāka, jo to populācija ir ļoti neliela, un tādēļ notiek tuvradniecīga vairošanās.[3]

Senos laikos austrumzemju aristoktāti gepardus lietoja antilopu medībām. To piederība liecināja par statusu sabiedrībā Senajā Ēģiptē, Indijā, Irānā un dažādās Āfrikas ciltīs. Ēģiptes faraoni gandrīz vienmēr tiek attēloti kopā ar gepardiem, kas liecina par spēku un karalisko izcelsmi. Vislielākais skaits gepardu, kas datēts vēsturiskajos avotos, ir piederējis 16. gadsimta Indijas valdniekam Akbaram Lielajam. To skaits pārsniedza 9000.[6]

Visi gepardi medību vajadzībām tika saķerti savvaļā, jo gepards netika audzināts no bērnības, jo tādam gepardam neattīstījās medību instinkts. Gepardus saķēra apmēram 1 — 2 gadus vecus, pieradināja un lietoja medībām. 1900. gados Irāna un Indija gepardus sāka importēt no Āfrikas, jo sāka pietrūkt vietējo gepardu.[6]

Pēc Irānas revolūcijas 1979. gadā gepardu dzīves apstākļi krasi pasliktinājās; Irānas ainavā izzuda gepardu galvenais medījums - gazeles. Tas noveda pie strauja gepardu populācijas samazinājuma un sadrumstalošanās. Ierobežotie zāles, ganību un ūdens resursi arvien vairāk tiek noslogoti ar mājlopiem. Gazelēm ne tikai trūkst ganību, tās tiek arī intensīvi medītas. Medīti tiek arī gepardi, lai arī tas ir aizliegts. Tos medī gan malu mednieki, gan zemnieki, sargājot mājlopus.[4] Šobrīd to izdzīvošana ir kritiska, un Āzijas gepards ir ierakstīts Sarkanajā grāmatā. Lai varētu atjaunot gepardu populāciju, pirmkārt ir jāatjauno gazeļu populācija. Irāna ir izveidojusi gepardu aizsargājamās teritorijas, bet to kontrole ir vāja.

Galvenās Irānas zemes bagātības ir ogles, varš un dzelzs, industrijas attīstība spiež gepardu atkāpties no ierastajām teritorijām. Pašas par sevi raktuves gepardus neapdraud, bet uzbūvētie ceļi ir devuši iespēju neapdzīvotos un grūti pieejamos rajonos ierasties ne tikai raktuvju strādniekiem, bet arī malu medniekiem. Gepardu apdzīvotās teritorijas ārpus rezervātiem robežojas ar Afganistānu un Pakistānas Beludžistānas provinci, līdz ar to izbūvētos ceļus ir iecienījuši arī opija kontrabandisti. Opija tranzīta ceļi ir kļuvuši valdībai par aizliegto zonu, un reģionā valdība pēc būtības nekontrolē notiekošo.[7]

Āzijas gepards (Acinonyx jubatus venaticus) ir viena no gepardu (Acinonyx jubatus) pasugām. To sauc arī par Irānas gepardu jeb Indijas gepardu. Laikā, kad Indija bija britu kolonija, to sauca arī par medību leopardu.

Āzijas gepardu pasugas izdzīvošana ir ļoti apdraudēta. To mūsdienās var sastapt tikai Irānā un nelielā daudzumā Pakistānā Beludžistānas provincē. Indijā pēdējais Āzijas gepards tika nošauts 1947. gadā, lai gan Indijas valdniekam Akbaram Lielajam 16. gadsimtā piederēja vairāk kā 9000 gepardu.

Tas dzīvo Irānas tuksnešainajos apvidos, un tā populācija ir sadrumstalota. Kādreiz šo geparda pasugu varēja sastapt, sākot ar Ziemeļāfriku, Arābiju un beidzot ar Indiju un Afganistānu. Pēdējo 10 gadu novērojumi tuksnesī liecina, ka šobrīd savvaļā varētu dzīvot 70 - 100 Āzijas gepardu. Apmēram 60 gepardu dzīvo Daštekavira tuksnesī. Āzijas gepards un Persijas leopards ir pēdējās lielo kaķu sugas, kas izdzīvojušas Irānā līdz mūsdienām. Kādreiz tik bieži sastopamais Kaspijas tīģeris un Āzijas lauva ir izmiruši pagājušā gadsimtā. Par Āzijas gepardu izmiršanas galvenajiem iemesliem uzskata: medījuma izzušana, teritoriju samazināšanās, vājš ģenētiskais materiāls, gepardu medības kažokādas ieguvei un gepardu izķeršana, lai pieradinātu un lietotu kā medību suņus.