tr

kırıntılardaki isimler

Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus bezeichnet die bisher einzige Spezies (Art) der Untergattung Sarbecovirus der Gattung Betacoronavirus in der Familie der Coronaviridae. Geläufige Abkürzungen wie „SARSr-CoV“,[3] englisch SARS-related coronavirus(es)[3] oder dt. „SARS-assoziierte(s) Coronavirus/-viren“ sind vom Speziesnamen abgeleitete sogenannte „Sammelbezeichnungen“ (englisch collective names).[4]

Die Spezies wurde 2009 vom International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) ratifiziert und fasste die vormalige Spezies Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus und eine neue Gruppe ähnlicher Viren, genannt Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related bat coronavirus, zusammen zu der neuen Spezies.[5] Die bekanntesten Vertreter dieser Spezies sind SARS-CoV und SARS-CoV-2,[6] die die Erkrankungen SARS bzw. COVID-19 auslösen.

Bis 2009 existierte die Spezies Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus, welche Viren enthielt, die mit dem SARS-Ausbruch 2003 in Verbindung standen, und eine Reihe praktisch identischer Virus-Isolate von Tieren. Es wurde vorgeschlagen, weitere weiter entfernt verwandte, neu entdeckte Fledermausviren (29 an der Zahl) zur Spezies hinzuzunehmen, die große genetische Übereinstimmungen (bis zu 97 % in Schlüsselbereichen) mit den Viren der bisherigen Spezies hatten. Darunter befanden sich z. B. SARS-Rh-BatCoV HKU3, SARSr-Rh-BatCoV und SARSr-Rh-BatCoV 273.[5]

Daraufhin wurde die Spezies Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus mit der Gruppe von neuen, sehr ähnlichen Fledermausviren, genannt Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related bat coronavirus oder „SARS-related Rhinolophus BatCoV“, vereint und die neue Spezies Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus gebildet. Im Rahmen dessen wurde auch die neue Unterfamilie Coronavirinae in der Familie Coronaviridae gebildet, und aus der bisherigen Gattung Coronavirus die neuen Gattungen Alpha- bis Gammacoronavirus (aus den vorherigen Phylogruppen 1 bis 3 der bisherigen Gattung).[5]

Die Regeln der ICTV für Virustaxonomie geben vor, dass Spezies-Namen weder abgekürzt noch in andere Sprachen übersetzt werden sollen. Daher sind die geläufigen Abkürzungen wie „SARSr-CoV(s)“ und „SARS-related coronavirus(es)“ keine (international offiziellen) Alternativ-Bezeichnungen der Spezies, sondern zulässige, gebräuchliche Sammelbezeichnungen für einzelne oder alle Viren in dieser Spezies.[4]

Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus bezeichnet die bisher einzige Spezies (Art) der Untergattung Sarbecovirus der Gattung Betacoronavirus in der Familie der Coronaviridae. Geläufige Abkürzungen wie „SARSr-CoV“, englisch SARS-related coronavirus(es) oder dt. „SARS-assoziierte(s) Coronavirus/-viren“ sind vom Speziesnamen abgeleitete sogenannte „Sammelbezeichnungen“ (englisch collective names).

Die Spezies wurde 2009 vom International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) ratifiziert und fasste die vormalige Spezies Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus und eine neue Gruppe ähnlicher Viren, genannt Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related bat coronavirus, zusammen zu der neuen Spezies. Die bekanntesten Vertreter dieser Spezies sind SARS-CoV und SARS-CoV-2, die die Erkrankungen SARS bzw. COVID-19 auslösen.

Unterschiede von Sars-CoV-1 und 2Ang SARSr-CoV[note 1] (Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus, SARS-related coronavirus) ay isang species ng coronavirus na napag-alamang nagdudulot ng impeksiyon sa mga tao, paniki, at ilang mammal. Ang SARS-related coronavirus ay isang enveloped, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA virus na pumapasok sa ACE2 receptor ng host cell. Ito ay mas malapit na nauugnay sa group 2 coronavirus (Betacoronavirus).

Ang dalawang strain ng virus ay nagdulot ng outbreak ng malubhang sakit sa paghinga sa mga tao: SARS-CoV, na nagdulot ng outbreak ng severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) noong 2002 hanggang 2004, at SARS-CoV-2, na mula noong huling bahagi ng 2019 ay naging sanhi ng isang outbreak ng coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Ang parehong strain na nagmula sa iisang ninuno ngunit hiwalay na tumalon (cross-species jump) sa tao, at ang SARS-CoV-2 ay hindi isang tuwirang inapo ng SARS-CoV. Mayroong daan-daang ibang strain ng SARSr-CoV, ang lahat ng ito ay kilala lamang na makahawa sa mga species na di-tao: ang mga paniki ay isang pangunahing reservoir ng maraming strain ng SARS-related coronavirus, at ilang strain naman ay sa palm civet na ipapalagay naninuno ng SARS-CoV.

Ang SARS-related coronavirus ay isa sa ilang mga virus na natukoy ng WHO noong 2016 bilang maaaring magdulot ng epidemya sa hinaharap sa isang bagong plano na binuo pagkatapos ng epidemya ng Ebola para sa madaliang pananaliksik at pag-unlad bago at sa panahon ng isang epidemya patungo sa mga diagnostic test, bakuna at gamot. Ang prediksiyon ay nangyari sa ng outbreak ng coronavirus noong 2019-20.

Hoodkategorii: Wiiren

Order: Nidovirales

Famile: Coronaviridae

Onerfamile: Orthocoronavirinae

Skööl: Betacoronavirus

Slach: Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus (SARSr-CoV)

Stamer: Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus – Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-2, SARS-CoV-2) – Severe acute respiratory syndrome-like coronavirus

SARSr-CoV

Ang SARSr-CoV (Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus, SARS-related coronavirus) ay isang species ng coronavirus na napag-alamang nagdudulot ng impeksiyon sa mga tao, paniki, at ilang mammal. Ang SARS-related coronavirus ay isang enveloped, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA virus na pumapasok sa ACE2 receptor ng host cell. Ito ay mas malapit na nauugnay sa group 2 coronavirus (Betacoronavirus).

Ang dalawang strain ng virus ay nagdulot ng outbreak ng malubhang sakit sa paghinga sa mga tao: SARS-CoV, na nagdulot ng outbreak ng severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) noong 2002 hanggang 2004, at SARS-CoV-2, na mula noong huling bahagi ng 2019 ay naging sanhi ng isang outbreak ng coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Ang parehong strain na nagmula sa iisang ninuno ngunit hiwalay na tumalon (cross-species jump) sa tao, at ang SARS-CoV-2 ay hindi isang tuwirang inapo ng SARS-CoV. Mayroong daan-daang ibang strain ng SARSr-CoV, ang lahat ng ito ay kilala lamang na makahawa sa mga species na di-tao: ang mga paniki ay isang pangunahing reservoir ng maraming strain ng SARS-related coronavirus, at ilang strain naman ay sa palm civet na ipapalagay naninuno ng SARS-CoV.

Ang SARS-related coronavirus ay isa sa ilang mga virus na natukoy ng WHO noong 2016 bilang maaaring magdulot ng epidemya sa hinaharap sa isang bagong plano na binuo pagkatapos ng epidemya ng Ebola para sa madaliang pananaliksik at pag-unlad bago at sa panahon ng isang epidemya patungo sa mga diagnostic test, bakuna at gamot. Ang prediksiyon ay nangyari sa ng outbreak ng coronavirus noong 2019-20.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome-relatit coronavirus (SARSr-CoV)[note 1] is a species o coronavirus that infects humans, bats an certain ither mammals.[2][3]

Severe acute respiratory syndrome-relatit coronavirus (SARSr-CoV) is a species o coronavirus that infects humans, bats an certain ither mammals.

गंभीर तीव्र श्वसन सिंड्रोम संबंधित कोरोनाव्हायरस (SARSr-CoV) [१] ही कोरोना विषाणूची प्रजाती आहे, जी मानव, वटवाघूळ आणि काही इतर सस्तन प्राणी इत्यादीना संसर्गबाधित करते. [२] [३] हा एकएफाईड पॉझिटिव्ह-सेन्स-सिंगल-स्ट्रेंडेड आरएनए विषाणू आहे जो एसीई 2 रीसेप्टरला बांधूण त्याच्या होस्ट सेलमध्ये प्रवेश करतो. [४] हाबीटाकोरोनॅव्हायरस आणि सबजेनस सरबेकॉरोनाव्हायरस या वंशातील एक सदस्य आहे. [५] [६]

|title= (सहाय्य); |access-date= requires |url= (सहाय्य) |title= (सहाय्य) गंभीर तीव्र श्वसन सिंड्रोम संबंधित कोरोनाव्हायरस (SARSr-CoV) ही कोरोना विषाणूची प्रजाती आहे, जी मानव, वटवाघूळ आणि काही इतर सस्तन प्राणी इत्यादीना संसर्गबाधित करते. हा एकएफाईड पॉझिटिव्ह-सेन्स-सिंगल-स्ट्रेंडेड आरएनए विषाणू आहे जो एसीई 2 रीसेप्टरला बांधूण त्याच्या होस्ट सेलमध्ये प्रवेश करतो. हाबीटाकोरोनॅव्हायरस आणि सबजेनस सरबेकॉरोनाव्हायरस या वंशातील एक सदस्य आहे.

沙士病毒,官名嚴重急性呼吸道綜合征冠狀病毒,英言Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus,略云SARS-CoV,屬冠狀病毒科。初現於二〇〇三年,作瘟疫於廣東,波及中國[一][二]。染病者,炎肺起熱,四肢痛乏,頭痛咳嗽。疫初,廣東政府欲蔽百姓,噤默媒體,斷香港電視臺之聲。[三]事後,時中華人民共和國衛生部部長張文康因此免職。

沙士病毒,官名嚴重急性呼吸道綜合征冠狀病毒,英言Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus,略云SARS-CoV,屬冠狀病毒科。初現於二〇〇三年,作瘟疫於廣東,波及中國。染病者,炎肺起熱,四肢痛乏,頭痛咳嗽。疫初,廣東政府欲蔽百姓,噤默媒體,斷香港電視臺之聲。事後,時中華人民共和國衛生部部長張文康因此免職。

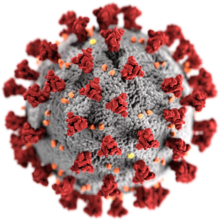

Severe acute respiratory syndrome–related coronavirus (SARSr-CoV or SARS-CoV)[note 1] is a species of virus consisting of many known strains phylogenetically related to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 1 (SARS-CoV-1) that have been shown to possess the capability to infect humans, bats, and certain other mammals.[2][3] These enveloped, positive-sense single-stranded RNA viruses enter host cells by binding to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor.[4] The SARSr-CoV species is a member of the genus Betacoronavirus and of the subgenus Sarbecovirus (SARS Betacoronavirus).[5][6]

Two strains of the virus have caused outbreaks of severe respiratory diseases in humans: severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 1 (SARS-CoV or SARS-CoV-1), which caused the 2002–2004 outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which is causing the ongoing pandemic of COVID-19.[7][8] There are hundreds of other strains of SARSr-CoV, which are only known to infect non-human species: bats are a major reservoir of many strains of SARSr-CoV; several strains have been identified in Himalayan palm civets, which were likely ancestors of SARS-CoV-1.[7][9]

The SARS-related coronavirus was one of several viruses identified by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2016 as a likely cause of a future epidemic in a new plan developed after the Ebola epidemic for urgent research and development before and during an epidemic towards diagnostic tests, vaccines and medicines. This prediction came to pass with the COVID-19 pandemic.[10][11]

SARS-related coronavirus is a member of the genus Betacoronavirus (group 2) and monotypic of the subgenus Sarbecovirus (subgroup B).[12] Sarbecoviruses, unlike embecoviruses or alphacoronaviruses, have only one papain-like proteinase (PLpro) instead of two in the open reading frame ORF1ab.[13] SARSr-CoV was determined to be an early split-off from the betacoronaviruses based on a set of conserved domains that it shares with the group.[14][15]

Bats serve as the main host reservoir species for the SARS-related coronaviruses like SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2. The virus has coevolved in the bat host reservoir over a long period of time.[16] Only recently have strains of SARS-related coronavirus been observed to have evolved into having been able to make the cross-species jump from bats to humans, as in the case of the strains SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2.[17][4] Both of these strains descended from a single ancestor but made the cross-species jump into humans separately. SARS-CoV-2 is not a direct descendant of SARS-CoV-1.[7]

The SARS-related coronavirus is an enveloped, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA virus. Its genome is about 30 kb, which is one of the largest among RNA viruses. The virus has 14 open reading frames which overlap in some cases.[18] The genome has the usual 5′ methylated cap and a 3′ polyadenylated tail.[19] There are 265 nucleotides in the 5'UTR and 342 nucleotides in the 3'UTR.[18]

The 5' methylated cap and 3' polyadenylated tail allows the positive-sense RNA genome to be directly translated by the host cell's ribosome on viral entry.[20] SARSr-CoV is similar to other coronaviruses in that its genome expression starts with translation by the host cell's ribosomes of its initial two large overlapping open reading frames (ORFs), 1a and 1b, both of which produce polyproteins.[18]

The functions of several of the viral proteins are known.[25] ORFs 1a and 1b encode the replicase/transcriptase polyprotein, and later ORFs 2, 4, 5, and 9a encode, respectively, the four major structural proteins: spike (S), envelope (E), membrane (M), and nucleocapsid (N).[26] The later ORFs also encode for eight unique proteins (orf3a to orf9b), known as the accessory proteins, many with no known homologues. The different functions of the accessory proteins are not well understood.[25]

SARS coronaviruses have been genetically engineered in several laboratories.[27]

Phylogenetic analysis showed that the evolutionary branch composed of Bat coronavirus BtKY72 and BM48-31 was the base group of SARS–related CoVs evolutionary tree, which separated from other SARS–related CoVs earlier than SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2.[28][29]

SARSr‑CoVBat CoV BtKY72

Bat CoV BM48-31

SARS-CoV-1 related coronavirus

SARS-CoV-2 related coronavirus

A phylogenetic tree based on whole-genome sequences of SARS-CoV-1 and related coronaviruses is:

SARS‑CoV‑1 related coronavirus16BO133, 86.3% to SARS-CoV-1, Rhinolophus ferrumequinum, North Jeolla, South Korea[30]

JTMC15, 86.4% to SARS-CoV-1, Rhinolophus ferrumequinum, Tonghua, Jilin[31]

Bat SARS CoV Rf1, 87.8% to SARS-CoV-1, Rhinolophus ferrumequinum, Yichang, Hubei[32]

BtCoV HKU3, 87.9% to SARS-CoV-1, Rhinolophus sinicus, Hong Kong and Guangdong[33]

LYRa11, 90.9% to SARS-CoV-1, Rhinolophus affinis, Baoshan, Yunnan[34]

Bat SARS-CoV/Rp3, 92.6% to SARS-CoV-1, Rhinolophus pearsoni, Nanning, Guangxi[32]

Bat SL-CoV YNLF_31C, 93.5% to SARS-CoV-1, Rhinolophus ferrumequinum, Lufeng, Yunnan[35]

Bat SL-CoV YNLF_34C, 93.5% to SARS-CoV-1, Rhinolophus ferrumequinum, Lufeng, Yunnan[35]

SHC014-CoV, 95.4% to SARS-CoV-1, Rhinolophus sinicus, Kunming, Yunnan[36]

WIV1, 95.6% to SARS-CoV-1, Rhinolophus sinicus, Kunming, Yunnan[36]

WIV16, 96.0% to SARS-CoV-1, Rhinolophus sinicus Kunming, Yunnan[37]

Civet SARS-CoV, 99.8% to SARS-CoV-1, Paguma larvata, market in Guangdong, China[33]

SARS-CoV-2, 79% to SARS-CoV-1[38]

A phylogenetic tree based on whole-genome sequences of SARS-CoV-2 and related coronaviruses is:[39][40]

SARS‑CoV‑2 related coronavirus(Bat) Rc-o319, 81% to SARS-CoV-2, Rhinolophus cornutus, Iwate, Japan[41]

Bat SL-ZXC21, 88% to SARS-CoV-2, Rhinolophus pusillus, Zhoushan, Zhejiang[42]

Bat SL-ZC45, 88% to SARS-CoV-2, Rhinolophus pusillus, Zhoushan, Zhejiang[42]

Pangolin SARSr-CoV-GX, 85.3% to SARS-CoV-2, Manis javanica, smuggled from Southeast Asia[43]

Pangolin SARSr-CoV-GD, 90.1% to SARS-CoV-2, Manis javanica, smuggled from Southeast Asia[44]

Bat RshSTT182, 92.6% to SARS-CoV-2, Rhinolophus shameli, Steung Treng, Cambodia[45]

Bat RshSTT200, 92.6% to SARS-CoV-2, Rhinolophus shameli, Steung Treng, Cambodia[45]

(Bat) RacCS203, 91.5% to SARS-CoV-2, Rhinolophus acuminatus, Chachoengsao, Thailand[40]

(Bat) RmYN02, 93.3% to SARS-CoV-2, Rhinolophus malayanus, Mengla, Yunnan[46]

(Bat) RpYN06, 94.4% to SARS-CoV-2, Rhinolophus pusillus, Xishuangbanna, Yunnan[39]

(Bat) RaTG13, 96.1% to SARS-CoV-2, Rhinolophus affinis, Mojiang, Yunnan[47]

(Bat) BANAL-52, 96.8% to SARS-CoV-2, Rhinolophus malayanus, Vientiane, Laos[48]

SARS-CoV-1, 79% to SARS-CoV-2

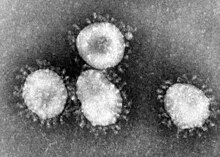

The morphology of the SARS-related coronavirus is characteristic of the coronavirus family as a whole. The viruses are large pleomorphic spherical particles with bulbous surface projections that form a corona around the particles in electron micrographs.[50] The size of the virus particles is in the 80–90 nm range. The envelope of the virus in electron micrographs appears as a distinct pair of electron dense shells.[51]

The viral envelope consists of a lipid bilayer where the membrane (M), envelope (E) and spike (S) proteins are anchored.[52] The spike proteins provide the virus with its bulbous surface projections, known as peplomers. The spike protein's interaction with its complement host cell receptor is central in determining the tissue tropism, infectivity, and species range of the virus.[53][54]

Inside the envelope, there is the nucleocapsid, which is formed from multiple copies of the nucleocapsid (N) protein, which are bound to the positive-sense single-stranded (~30 kb) RNA genome in a continuous beads-on-a-string type conformation.[55][56] The lipid bilayer envelope, membrane proteins, and nucleocapsid protect the virus when it is outside the host.[57]

SARS-related coronavirus follows the replication strategy typical of all coronaviruses.[19][58]

The attachment of the SARS-related coronavirus to the host cell is mediated by the spike protein and its receptor.[59] The spike protein receptor binding domain (RBD) recognizes and attaches to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor.[4] Following attachment, the virus can enter the host cell by two different paths. The path the virus takes depends on the host protease available to cleave and activate the receptor-attached spike protein.[60]

The attachment of sarbecoviruses to ACE2 has been shown to be an evolutionarily conserved feature, present in many species of the taxon.[61]

The first path the SARS coronavirus can take to enter the host cell is by endocytosis and uptake of the virus in an endosome. The receptor-attached spike protein is then activated by the host's pH-dependent cysteine protease cathepsin L. Activation of the receptor-attached spike protein causes a conformational change, and the subsequent fusion of the viral envelope with the endosomal wall.[60]

Alternatively, the virus can enter the host cell directly by proteolytic cleavage of the receptor-attached spike protein by the host's TMPRSS2 or TMPRSS11D serine proteases at the cell surface.[62][63] In the SARS coronavirus, the activation of the C-terminal part of the spike protein triggers the fusion of the viral envelope with the host cell membrane by inducing conformational changes which are not fully understood.[64]

After fusion the nucleocapsid passes into the cytoplasm, where the viral genome is released.[59] The genome acts as a messenger RNA, and the cell's ribosome translates two-thirds of the genome, which corresponds to the open reading frame ORF1a and ORF1b, into two large overlapping polyproteins, pp1a and pp1ab.

The larger polyprotein pp1ab is a result of a -1 ribosomal frameshift caused by a slippery sequence (UUUAAAC) and a downstream RNA pseudoknot at the end of open reading frame ORF1a.[67] The ribosomal frameshift allows for the continuous translation of ORF1a followed by ORF1b.[68]

The polyproteins contain their own proteases, PLpro and 3CLpro, which cleave the polyproteins at different specific sites. The cleavage of polyprotein pp1ab yields 16 nonstructural proteins (nsp1 to nsp16). Product proteins include various replication proteins such as RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), RNA helicase, and exoribonuclease (ExoN).[68]

The two SARS-CoV-2 proteases (PLpro and 3CLpro) also interfere with the immune system response to the viral infection by cleaving three immune system proteins. PLpro cleaves IRF3 and 3CLpro cleaves both NLRP12 and TAB1. "Direct cleavage of IRF3 by NSP3 could explain the blunted Type-I IFN response seen during SARS-CoV-2 infections while NSP5 mediated cleavage of NLRP12 and TAB1 point to a molecular mechanism for enhanced production of IL-6 and inflammatory response observed in COVID-19 patients."[69]

A number of the nonstructural replication proteins coalesce to form a multi-protein replicase-transcriptase complex (RTC).[68] The main replicase-transcriptase protein is the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp). It is directly involved in the replication and transcription of RNA from an RNA strand. The other nonstructural proteins in the complex assist in the replication and transcription process.[65]

The protein nsp14 is a 3'-5' exoribonuclease which provides extra fidelity to the replication process. The exoribonuclease provides a proofreading function to the complex which the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase lacks. Similarly, proteins nsp7 and nsp8 form a hexadecameric sliding clamp as part of the complex which greatly increases the processivity of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase.[65] The coronaviruses require the increased fidelity and processivity during RNA synthesis because of the relatively large genome size in comparison to other RNA viruses.[70]

One of the main functions of the replicase-transcriptase complex is to transcribe the viral genome. RdRp directly mediates the synthesis of negative-sense subgenomic RNA molecules from the positive-sense genomic RNA. This is followed by the transcription of these negative-sense subgenomic RNA molecules to their corresponding positive-sense mRNAs.[71]

The other important function of the replicase-transcriptase complex is to replicate the viral genome. RdRp directly mediates the synthesis of negative-sense genomic RNA from the positive-sense genomic RNA. This is followed by the replication of positive-sense genomic RNA from the negative-sense genomic RNA.[71]

The replicated positive-sense genomic RNA becomes the genome of the progeny viruses. The various smaller mRNAs are transcripts from the last third of the virus genome which follows the reading frames ORF1a and ORF1b. These mRNAs are translated into the four structural proteins (S, E, M, and N) that will become part of the progeny virus particles and also eight other accessory proteins (orf3 to orf9b) which assist the virus.[72]

When two SARS-CoV genomes are present in a host cell, they may interact with each other to form recombinant genomes that can be transmitted to progeny viruses. Recombination likely occurs during genome replication when the RNA polymerase switches from one template to another (copy choice recombination).[73] Human SARS-CoV appears to have had a complex history of recombination between ancestral coronaviruses that were hosted in several different animal groups.[73][74]

RNA translation occurs inside the endoplasmic reticulum. The viral structural proteins S, E and M move along the secretory pathway into the Golgi intermediate compartment. There, the M proteins direct most protein-protein interactions required for assembly of viruses following its binding to the nucleocapsid.[75]

Progeny viruses are released from the host cell by exocytosis through secretory vesicles.[75]

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) {{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Severe acute respiratory syndrome–related coronavirus (SARSr-CoV or SARS-CoV) is a species of virus consisting of many known strains phylogenetically related to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 1 (SARS-CoV-1) that have been shown to possess the capability to infect humans, bats, and certain other mammals. These enveloped, positive-sense single-stranded RNA viruses enter host cells by binding to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor. The SARSr-CoV species is a member of the genus Betacoronavirus and of the subgenus Sarbecovirus (SARS Betacoronavirus).

Two strains of the virus have caused outbreaks of severe respiratory diseases in humans: severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 1 (SARS-CoV or SARS-CoV-1), which caused the 2002–2004 outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which is causing the ongoing pandemic of COVID-19. There are hundreds of other strains of SARSr-CoV, which are only known to infect non-human species: bats are a major reservoir of many strains of SARSr-CoV; several strains have been identified in Himalayan palm civets, which were likely ancestors of SARS-CoV-1.

The SARS-related coronavirus was one of several viruses identified by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2016 as a likely cause of a future epidemic in a new plan developed after the Ebola epidemic for urgent research and development before and during an epidemic towards diagnostic tests, vaccines and medicines. This prediction came to pass with the COVID-19 pandemic.

SARSr-CoV

SARSr-CoV (acronyme anglais de severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus)[note 1] est le nom scientifique officiel de l'espèce[note 2] de coronavirus liés au syndrome respiratoire aigu sévère (soit également SL-CoV, pour SARS-like coronavirus). Ce sont, par exemple, le virus du SRAS de 2003 ou celui du Covid-19. Les différentes formes de ces coronavirus infectent les humains, les chauves-souris et d'autres mammifères[3]. Il s'agit d'un virus à ARN simple brin de sens positif enveloppé qui pénètre dans sa cellule hôte en se liant au récepteur ACE2[4]. Il est membre du genre Betacoronavirus et du sous-genre Sarbecovirus[5],[6], différent de celui du coronavirus causant le MERS.

Deux souches de SARSr-CoV ont provoqué des flambées de maladies respiratoires graves chez l'humain : le SARS-CoV, qui a provoqué une flambée de syndrome respiratoire aigu sévère (SRAS) entre 2002 et 2003, et le SARS-CoV-2, qui depuis fin 2019 a provoqué une pandémie de maladie à coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19)[7],[8]. Il existe des centaines d'autres souches de SARSr-CoV, qui sont connues pour n'infecter que des espèces non humaines : les chauves-souris sont un réservoir majeur de nombreuses souches de SARSr-CoV, et plusieurs souches ont été identifiées dans les civettes de palmier, qui étaient les ancêtres probables du SARS-CoV[9].

Le SARSr-CoV était l'une des nombreuses espèces virales identifiées par l'Organisation mondiale de la santé (OMS) en 2016 comme une cause probable d'une future épidémie dans un nouveau plan élaboré après l'épidémie d'Ebola pour la recherche et le développement urgents de tests de dépistage, vaccins et médicaments. La prédiction s'est réalisée avec la pandémie de Covid-19[10],[11].

L'espèce virale Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus est membre du genre Betacoronavirus et du sous-genre Sarbecovirus (sous-groupe B)[12] dans la famille Coronaviridae et la sous-famille Orthocoronavirinae. Les sarbecovirus, contrairement aux embécovirus ou aux alphacoronavirus, n'ont qu'une seule protéinase de type papaïne (PLpro) au lieu de deux dans le cadre de lecture ouvert ORF1[13]. SARSr-CoV a été déterminée comme une séparation précoce des bétacoronavirus sur la base d'un ensemble de domaines conservés qu'il partage avec le groupe[14],[15].

Les chauves-souris constituent le principal hôte réservoir du SARSr-CoV. Le virus a co-évolué dans le réservoir hôte des chauves-souris sur une longue période de temps[16]. Ce n'est que récemment que des souches de SARSr-CoV ont évolué et sont passées aux humains, comme dans le cas des souches SARS-CoV et SARS-CoV-2[17],[4]. Ces deux souches issues d'un seul ancêtre ont effectué leur passage aux humains séparément : SARS-CoV-2 n'est pas un descendant direct de SARS-CoV[7].

L'arbre phylogénétique des souches de coronavirus de l'espèce SARSr-CoV est le suivant :

Bat CoV BtKY72[18]

Bat CoV BM48-31[19]

SARSr-CoV JL2012 et Rf4092[2]

SARSr-CoV YN2013, Rp3, HKU3 etc.[2]

SARS-CoV-1 (agent infectieux du SRAS)

Rc-o319, Rhinolophus cornutus, Iwate, Japon[22]

SL-ZXC21, Rhinolophus pusillus, Zhoushan, Zhejiang[23]

SL-ZC45, Rhinolophus pusillus, Zhoushan, Zhejiang[23]

SARSr-CoV-GX, Manis javanica, Asie du Sud-Est[24]

SARSr-CoV-GD, Manis javanica, Asie du Sud-Est[25]

RshSTT182, Rhinolophus shameli, Stoeng Treng, Cambodge[26]

RshSTT200, Rhinolophus shameli, Stoeng Treng, Cambodge[26]

RacCS203, Rhinolophus acuminatus, Chachoengsao, Thaïlande[27]

RmYN02, Rhinolophus malayanus, Mengla, Yunnan[28]

RaTG13, Rhinolophus affinis, Mojiang, Yunnan[29]

SARS-CoV-2 (agent infectieux de la Covid-19)

SARSr-CoV est un virus à ARN simple brin enveloppé, de polarité positive. Son génome est d'environ 30 kb, l'un des plus grands parmi les virus à ARN. Il a 14 cadres ouverts de lecture (ORF) dont certains se chevauchent[30]. Le génome a une coiffe à son extrémité 5' et une queue polyadénylée à son extrémité 3'[31]. Il y a 265 nucléotides dans le 5'UTR et 342 nucléotides dans le 3'UTR.

La coiffe et la queue polyadénylée permettent au génome d'ARN d'être directement traduit par le ribosome de la cellule hôte[32]. SARSr-CoV est similaire à d'autres coronavirus en ce que son expression génomique commence par la traduction par les ribosomes de la cellule hôte de ses deux grands ORF, 1a et 1b, qui produisent tous deux des polyprotéines[30].

Les fonctions de plusieurs des protéines virales sont connues[36]. Les ORF 1a et 1b codent pour la réplicase/transcriptase et les ORF 2, 4, 5 et 9a codent, respectivement, pour les quatre principales protéines structurales : spike, enveloppe, membrane et nucléocapside[37]. Les derniers ORF codent également pour huit protéines uniques (orf3a à orf9b), connues sous le nom de protéines accessoires, sans homologues connus. Les différentes fonctions des protéines accessoires ne sont pas bien comprises.

La morphologie du SARSr-CoV est caractéristique des coronavirus dans son ensemble. Les virions sont de grosses particules sphériques pléomorphes avec des projections de surface bulbeuses, les péplomères, qui forment une couronne autour des particules sur des micrographies électroniques[38]. Cette apparence en couronne a donné leur nom aux coronavirus. La taille des particules virales se situe entre 80 et 90 nm.

L'enveloppe virale est constituée d'une bicouche lipidique où les protéines de la membrane (M), de l'enveloppe (E) et en pointe (S, Spike) sont ancrées[39]. La protéine S est aussi appelée péplomère ou protéine spiculaire. L'interaction de la protéine S avec le récepteur cellulaire est centrale pour déterminer le tropisme tissulaire, l'infectiosité et la gamme d'espèces du virus[40],[41] ; il constitue donc une clé importante de l'adaptation à l'espèce humaine.

À l'intérieur de l'enveloppe, il y a la nucléocapside, qui est formée de plusieurs copies de la protéine N, liées au génome ARN dans une conformation de type « billes sur une chaîne » continue[42],[43]. L'enveloppe bicouche lipidique, les protéines membranaires et la nucléocapside protègent le virus lorsqu'il est à l'extérieur de l'hôte[44]. Ces protections sont sensibles aux détergents, au savon et à l'alcool.

SARSr-CoV suit la stratégie de réplication typique de tous les coronavirus[31],[45],[46],[47],[48].

La fixation du virion de SARSr-CoV à la cellule hôte est déterminée par la protéine S et son récepteur[49]. Le domaine de liaison au récepteur de la protéine S (Receptor-Binding Domain, RBD) reconnaît et se fixe au récepteur de l'enzyme de conversion de l'angiotensine 2 (ACE2)[4]. Après l'attachement, le virus peut pénétrer dans la cellule hôte par deux chemins différents, selon la protéase hôte disponible pour cliver et activer la protéine Spike attachée au récepteur[50].

La première voie que le virus peut emprunter pour pénétrer dans la cellule hôte est l'endocytose et l'absorption dans un endosome. La protéine S attachée au récepteur est ensuite activée par la cathepsine L, protéase à cystéine dépendante du potentiel hydrogène de l'hôte. L'activation de la protéine S attachée au récepteur provoque un changement de conformation et la fusion de l'enveloppe virale avec la paroi endosomale[50].

Alternativement, le virus peut pénétrer directement dans la cellule hôte par clivage protéolytique de la protéine S attachée au récepteur par les protéases à sérine de l'hôte TMPRSS2 ou TMPRSS11D[51],[52].

Après la fusion, la nucléocapside passe dans le cytoplasme, où le génome viral est libéré[49]. Le génome agit comme un ARN messager, dont le ribosome traduit les deux tiers correspondant au cadre de lecture ouvert ORF1a/ORF1b, en deux grandes polyprotéines qui se chevauchent, pp1a et pp1ab.

La plus grande polyprotéine, pp1ab, est le résultat d'un décalage de phase de lecture de -1 provoqué par une séquence glissante (UUUAAAC) et un pseudonoeud d'ARN en aval du cadre de lecture ouvert ORF1a[53]. Le décalage de phase de lecture permet la traduction continue de ORF1a suivie par ORF1b[54].

Les polyprotéines contiennent leurs propres protéases, PLpro et 3CLpro, qui clivent les polyprotéines en différents sites spécifiques. Le clivage de la polyprotéine pp1ab donne 16 protéines non structurales (nsp1 à nsp16). Ces protéines comprennent diverses protéines de réplication telles que l'ARN polymérase ARN dépendante (RdRp), l'ARN hélicase et l'exoribonucléase (ExoN)[54],[47].

Un certain nombre de protéines de réplication non structurales fusionnent pour former un complexe multi-protéique réplicase-transcriptase (Replicase-Transcriptase Complex, RTC)[54]. La principale protéine réplicase-transcriptase est l'ARN polymérase ARN dépendante (RdRp). Il est directement impliqué dans la réplication et la transcription de l'ARN à partir d'un brin d'ARN. Les autres protéines non structurales du complexe aident au processus de réplication et de transcription[55].

La protéine nsp14 est une exoribonucléase 3'-5' qui offre une fidélité supplémentaire au processus de réplication. L'exoribonucléase fournit une fonction de relecture au complexe qui manque à la RdRp. De même, les protéines nsp7 et nsp8 forment une « pince coulissante » ARN hexadécamérique faisant partie du complexe, ce qui augmente considérablement la processivité de la RdRp[55]. Les coronavirus nécessitent une fidélité et une processivité accrues pendant la synthèse d'ARN en raison de la grande taille de leur génome par rapport aux autres virus à ARN[56].

L'une des principales fonctions du complexe RTC est de transcrire le génome viral. La RdRp intervient directement dans la synthèse des molécules d'ARN subgénomique de sens négatif à partir de l'ARN génomique de sens positif. Ceci est suivi par la transcription de ces molécules d'ARN subgénomique de sens négatif en leurs ARNm de sens positif correspondants[57].

L'autre fonction importante du complexe RTC est de répliquer le génome viral. La RdRp intervient directement dans la synthèse de l'ARN génomique de sens négatif à partir de l'ARN génomique de sens positif. Ceci est suivi par la réplication de l'ARN génomique de sens positif à partir de l'ARN génomique de sens négatif[57].

L'ARN génomique de sens positif répliqué devient le génome des virus de la descendance. Les différents petits ARNm sont des transcrits du dernier tiers du génome, qui suit les cadres de lecture ORF1a et ORF1b. Ces ARNm sont traduits dans les quatre protéines structurales (S, E, M et N) qui feront partie des virions de la descendance et également huit autres protéines accessoires (orf3 à orf9b)[58].

La traduction de l'ARN se produit à l'intérieur du réticulum endoplasmique. Les protéines structurales virales S, E et M se déplacent le long de la voie de sécrétion dans le compartiment intermédiaire de Golgi. Là, les protéines M dirigent la plupart des interactions protéine-protéine nécessaires à l'assemblage des virus après sa liaison à la nucléocapside[59].

Les virions sont libérés de la cellule hôte par exocytose à travers des vésicules sécrétoires[59].

« Most notably, horseshoe bats were found to be the reservoir of SARS-like CoVs, while palm civet cats are considered to be the intermediate host for SARS-CoVs [43,44,45]. »

« Figure 2. Phylogenetic analysis of RNA-dependent RNA polymerases (Pol) of coronaviruses with complete genome sequences available. The tree was constructed by the neighbor-joining method and rooted using Breda virus polyprotein. »

« See Figure 1. »

« See Figure 1. »

« Furthermore, subsequent phylogenetic analysis using both complete genome sequence and proteomic approaches, it was concluded that SARSr-CoV is probably an early split-off from the Betacoronavirus lineage [1]; See Figure 2. »

« Betacoronaviruses-b ancestors, meaning SARSr-CoVs ancestors, could have been historically hosted by the common ancestor of the Rhinolophidae and Hipposideridae and could have later evolved independently in the lineages leading towards Rhinolophidae and Hipposideridae betacoronaviruses. »

« The SARS-CoV genome is ∼29.7 kb long and contains 14 open reading frames (ORFs) flanked by 5′ and 3′-untranslated regions of 265 and 342 nucleotides, respectively (Figure 1). »

« See Table 1. »

« See Table 1. »

« See Figure 1. »

« Virions acquired an envelope by budding into the cisternae and formed mostly spherical, sometimes pleomorphic, particles that averaged 78 nm in diameter (Figure 1A) »

« Nevertheless, the interaction between S protein and receptor remains the principal, if not sole, determinant of coronavirus host species range and tissue tropism. »

« Different SARS-CoV strains isolated from several hosts vary in their binding affinities for human ACE2 and consequently in their infectivity of human cells76,78 (Fig. 6b) »

« See section: Virion Structure. »

« See Figure 4c. »

« See Figure 10. »

« See section: Coronavirus Life Cycle – Attachment and Entry »

« See Figure 2 »

« The SARS-CoV can hijack two cellular proteolytic systems to ensure the adequate processing of its S protein. Cleavage of SARS-S can be facilitated by cathepsin L, a pH-dependent endo-/lysosomal host cell protease, upon uptake of virions into target cell endosomes (25). Alternatively, the type II transmembrane serine proteases (TTSPs) TMPRSS2 and HAT can activate SARS-S, presumably by cleavage of SARS-S at or close to the cell surface, and activation of SARS-S by TMPRSS2 allows for cathepsin L-independent cellular entry (26,–28). »

« S is activated and cleaved into the S1 and S2 subunits by other host proteases, such as transmembrane protease serine 2 (TMPRSS2) and TMPRSS11D, which enables cell surface non-endosomal virus entry at the plasma membrane. »

« See Figure 8. »

« See section: Replicase Protein Expression »

« See Table 2. »

« Finally, these results, combined with those from previous work (33, 44), suggest that CoVs encode at least three proteins involved in fidelity (nsp12-RdRp, nsp14-ExoN, and nsp10), supporting the assembly of a multiprotein replicase-fidelity complex, as described previously (38) »

« See section: Corona Life Cycle – Replication and Transcription »

« See Figure 1. »

« See section: Coronavirus Life Cycle – Assembly and Release »

SARSr-CoV

SARSr-CoV (acronyme anglais de severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus) est le nom scientifique officiel de l'espèce de coronavirus liés au syndrome respiratoire aigu sévère (soit également SL-CoV, pour SARS-like coronavirus). Ce sont, par exemple, le virus du SRAS de 2003 ou celui du Covid-19. Les différentes formes de ces coronavirus infectent les humains, les chauves-souris et d'autres mammifères. Il s'agit d'un virus à ARN simple brin de sens positif enveloppé qui pénètre dans sa cellule hôte en se liant au récepteur ACE2. Il est membre du genre Betacoronavirus et du sous-genre Sarbecovirus,, différent de celui du coronavirus causant le MERS.

Deux souches de SARSr-CoV ont provoqué des flambées de maladies respiratoires graves chez l'humain : le SARS-CoV, qui a provoqué une flambée de syndrome respiratoire aigu sévère (SRAS) entre 2002 et 2003, et le SARS-CoV-2, qui depuis fin 2019 a provoqué une pandémie de maladie à coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19),. Il existe des centaines d'autres souches de SARSr-CoV, qui sont connues pour n'infecter que des espèces non humaines : les chauves-souris sont un réservoir majeur de nombreuses souches de SARSr-CoV, et plusieurs souches ont été identifiées dans les civettes de palmier, qui étaient les ancêtres probables du SARS-CoV.

Le SARSr-CoV était l'une des nombreuses espèces virales identifiées par l'Organisation mondiale de la santé (OMS) en 2016 comme une cause probable d'une future épidémie dans un nouveau plan élaboré après l'épidémie d'Ebola pour la recherche et le développement urgents de tests de dépistage, vaccins et médicaments. La prédiction s'est réalisée avec la pandémie de Covid-19,.

Il coronavirus correlato alla SARS, o SARSr-CoV, (dall'inglese: SARS-related coronavirus) è una specie di coronavirus che infetta l'uomo, i pipistrelli e alcuni altri mammiferi, membro del genere Betacoronavirus, sottogenere Sarbecovirus.[1][2][3] I termini SARSr-CoV e SARS-CoV sono stati talvolta usati in modo intercambiabile, soprattutto prima della scoperta di SARS-CoV-2.

È un virus a RNA a singolo filamento avvolto in senso positivo che entra nella sua cellula ospite legandosi al recettore ACE2 tramite le spinule proteiche che sporgendo dalla membrana gli conferiscono la classica forma a corona al microscopio elettronico.[4]

Due ceppi del virus hanno causato focolai di gravi malattie respiratorie nell'uomo: SARS-CoV, che ha causato un'epidemia di SARS tra il 2002 e il 2003, e SARS-CoV-2, che ha causato la pandemia di COVID-19 del 2019-2021.[5][6]

Esistono centinaia di altri ceppi di SARSr-CoV, tutti noti solo per infettare specie non umane: i pipistrelli sono un serbatoio importante di molti ceppi di coronavirus correlato alla SARS; numerosi altri ceppi, probabili antenati di SARS-CoV, sono stati identificati in alcuni esemplari del genere Paradoxurus.[5][7]

Il coronavirus correlato alla SARS era uno dei numerosi virus che furono identificati nel 2016 dall'Organizzazione mondiale della sanità come probabile causa di una futura epidemia, in un nuovo piano sviluppato, dopo l'ultima epidemia di Ebola, per la ricerca e lo sviluppo urgenti di test diagnostici, vaccini e medicinali.[8] La previsione si è avverata con la pandemia di coronavirus del 2019-2020.[9]

Il coronavirus correlato alla SARS, o SARSr-CoV, (dall'inglese: SARS-related coronavirus) è una specie di coronavirus che infetta l'uomo, i pipistrelli e alcuni altri mammiferi, membro del genere Betacoronavirus, sottogenere Sarbecovirus. I termini SARSr-CoV e SARS-CoV sono stati talvolta usati in modo intercambiabile, soprattutto prima della scoperta di SARS-CoV-2.

È un virus a RNA a singolo filamento avvolto in senso positivo che entra nella sua cellula ospite legandosi al recettore ACE2 tramite le spinule proteiche che sporgendo dalla membrana gli conferiscono la classica forma a corona al microscopio elettronico.

Due ceppi del virus hanno causato focolai di gravi malattie respiratorie nell'uomo: SARS-CoV, che ha causato un'epidemia di SARS tra il 2002 e il 2003, e SARS-CoV-2, che ha causato la pandemia di COVID-19 del 2019-2021.

Esistono centinaia di altri ceppi di SARSr-CoV, tutti noti solo per infettare specie non umane: i pipistrelli sono un serbatoio importante di molti ceppi di coronavirus correlato alla SARS; numerosi altri ceppi, probabili antenati di SARS-CoV, sono stati identificati in alcuni esemplari del genere Paradoxurus.

Il coronavirus correlato alla SARS era uno dei numerosi virus che furono identificati nel 2016 dall'Organizzazione mondiale della sanità come probabile causa di una futura epidemia, in un nuovo piano sviluppato, dopo l'ultima epidemia di Ebola, per la ricerca e lo sviluppo urgenti di test diagnostici, vaccini e medicinali. La previsione si è avverata con la pandemia di coronavirus del 2019-2020.

SARS-CoV atau SARSr-CoV (Koronavirus berkaitan sindrom pernafasan yang teruk) ialah virus yang menyebabkan sindrom pernafasan akut teruk (SARS).[2] Pada 16 April 2003, setelah SARS merebak di Asia dan kes kedua di tempat lainnya di serata dunia, Pertubuhan Kesihatan Sedunia (WHO) mengeluarkan kenyataan media yang menyatakan bahawa koronavirus yang dikenalpasti oleh beberapa makmal, ialah sebagai penyebab rasmi SARS. Sampel virus tersebut disimpan di makmal Bandar Raya New York, San Francisco, Manila, Hong Kong, dan Toronto

Pada 12 April 2003, ahli sains yang bekerja di Pusat Sains Genom Michael Smith di Vancouver selesai memetakan urutan genetik virus korona yang diyakini berkaitan dengan SARS. Pasukan ini diketuai oleh Dr. Marco Marra, berkolaborasi dengan Pusat Kawalan Penyakit dan Makmal Mikrobiologi Kebangsaan British Columbia di Winnipeg, Manitoba, menggunakan sampel dari pesakit yang dijgkiti di Toronto. Peta tersebut, dipuji oleh WHO sebagai langkah maju yang penting dalam memerangi SARS, dibahagikan kepada para ilmuwan di seluruh dunia melalui laman web GSC. Dr. Donald Low dari Hospital Mount Sinai di Toronto menggambarkan penemuan tersebut dibuat dengan "kecepatan yang belum pernah terjadi sebelumnya".[3] Sejak itu urutan koronavirus SARS telah disahkan oleh kumpulan bebas yang lain.

Koronavirus SARS ialah salah satu dari beberapa virus yang dikenalpasti oleh WHO sebagai kemungkinan penyebab wabak di masa depan setelah wabak Ebola, sehingga penyelidikan dan pembangunan diperlukan secepat mungkin, sebelum dan selepas wabak terhadap ujian diagnostik, vaksin, dan ubat-ubatan.[4][5]

SARS-CoV atau SARSr-CoV (Koronavirus berkaitan sindrom pernafasan yang teruk) ialah virus yang menyebabkan sindrom pernafasan akut teruk (SARS). Pada 16 April 2003, setelah SARS merebak di Asia dan kes kedua di tempat lainnya di serata dunia, Pertubuhan Kesihatan Sedunia (WHO) mengeluarkan kenyataan media yang menyatakan bahawa koronavirus yang dikenalpasti oleh beberapa makmal, ialah sebagai penyebab rasmi SARS. Sampel virus tersebut disimpan di makmal Bandar Raya New York, San Francisco, Manila, Hong Kong, dan Toronto

Pada 12 April 2003, ahli sains yang bekerja di Pusat Sains Genom Michael Smith di Vancouver selesai memetakan urutan genetik virus korona yang diyakini berkaitan dengan SARS. Pasukan ini diketuai oleh Dr. Marco Marra, berkolaborasi dengan Pusat Kawalan Penyakit dan Makmal Mikrobiologi Kebangsaan British Columbia di Winnipeg, Manitoba, menggunakan sampel dari pesakit yang dijgkiti di Toronto. Peta tersebut, dipuji oleh WHO sebagai langkah maju yang penting dalam memerangi SARS, dibahagikan kepada para ilmuwan di seluruh dunia melalui laman web GSC. Dr. Donald Low dari Hospital Mount Sinai di Toronto menggambarkan penemuan tersebut dibuat dengan "kecepatan yang belum pernah terjadi sebelumnya". Sejak itu urutan koronavirus SARS telah disahkan oleh kumpulan bebas yang lain.

Koronavirus SARS ialah salah satu dari beberapa virus yang dikenalpasti oleh WHO sebagai kemungkinan penyebab wabak di masa depan setelah wabak Ebola, sehingga penyelidikan dan pembangunan diperlukan secepat mungkin, sebelum dan selepas wabak terhadap ujian diagnostik, vaksin, dan ubat-ubatan.

Het SARS-virus is een coronavirus dat de ziekte SARS veroorzaakt. Het gaat om een virus dat vóór de uitbraak van SARS nog niet eerder bij mensen was aangetroffen.

De definitieve identificatie van het SARS-virus werd op 16 april 2003 bekendgemaakt door de Wereldgezondheidsorganisatie (WHO). De naam SARS-virus werd bepaald door de WHO en de laboratoria die participeerden in het onderzoek.

Op 24 september 2012 werd voor het eerst het verwante MERS-virus beschreven.

Het SARS-virus is een coronavirus dat de ziekte SARS veroorzaakt. Het gaat om een virus dat vóór de uitbraak van SARS nog niet eerder bij mensen was aangetroffen.

De definitieve identificatie van het SARS-virus werd op 16 april 2003 bekendgemaakt door de Wereldgezondheidsorganisatie (WHO). De naam SARS-virus werd bepaald door de WHO en de laboratoria die participeerden in het onderzoek.

Op 24 september 2012 werd voor het eerst het verwante MERS-virus beschreven.

Systematyka Grupa Grupa IV ((+)ssRNA) Rząd Nidowirusy Rodzina Koronawirusy Rodzaj Betakoronawirus Cechy wiralne Skrót SARS-CoV Wywoływane choroby Zespół ostrej ciężkiej niewydolności oddechowej

Systematyka Grupa Grupa IV ((+)ssRNA) Rząd Nidowirusy Rodzina Koronawirusy Rodzaj Betakoronawirus Cechy wiralne Skrót SARS-CoV Wywoływane choroby Zespół ostrej ciężkiej niewydolności oddechowej Wirus SARS – czynnik etiologiczny ciężkiego ostrego zespołu oddechowego (SARS od ang. Severe acute respiratory syndrome)[1].

Jest to RNA wirus należący do koronawirusów. Średnica cząsteczki wirusa wynosi 70-100 nm, a genom zawiera 29751 lub 29727 nukleotydów (w zależności od szczepu) i jest to największy znany RNA-wirus. Ponieważ cały genom wirusa został odczytany, wiemy, że w 50-60% jest on identyczny z innymi koronawirusami.

Pierwsze zachorowania wystąpiły w listopadzie 2002 roku w mieście Foshan w prowincji Guangdong w Chinach. Stopniowo doszło do rozprzestrzenienia choroby na inne rejony Chin, inne kraje Azji, a potem, drogą podróży lotniczych, inne kraje świata. Przypuszcza się, że do pierwotnego zachorowania doszło w wyniku kontaktu ze zwierzętami trzymanymi w klatkach na targu. Stwierdzono zakażenie cywet, fretek i kotów wirusem SARS.

Do lipca 2003 roku zanotowano na świecie 8439 zachorowań, z czego u 812 chorych zakończyły się one śmiercią. 16 kwietnia 2003 roku WHO (Światowa Organizacja Zdrowia) ogłosiła, że czynnikiem chorobotwórczym wywołującym SARS, jest wirus należący do koronawirusów – wirus SARS.

Różnice w budowie i innych cechach morfologicznych, a także klinicznym przebiegu zachorowań, pozwalają stwierdzić, że jest to nowy wirus, odmienny od dotychczas znanych koronawirusów, które u człowieka powodują łagodnie przebiegające infekcje dróg oddechowych i przewodu pokarmowego. Przypuszcza się, że do powstania nowego wirusa mogło dojść w wyniku transdukcji obcych genów lub rekombinacji z innymi koronawirusami.

Czas wylęgania: 2-10 dni, maksymalnie do 14-20 dni.

Wirusa wyhodowano z wydzielin z dróg oddechowych, w ślinie może się znajdować 100 mln cząstek wirusa w 1 ml. Niewielkie ilości wirusa można stwierdzić w moczu i surowicy.

Przeciwciała przeciwwirusowe w klasie IgG zaczynają się pojawiać w surowicy ok. 9-10 dnia od zakażenia. Do celów diagnostycznych zaleca się oznaczanie w surowicy w 21. i 28. dniu od początku choroby.

Do zakażenia dochodzi najczęściej drogą kropelkową, a także przez kontakt zakaźnego materiału z błonami śluzowymi. Udowodniona jest możliwość zakażenia przez kontakt z kałem osoby chorej. Ponieważ przy wykonywaniu procedur medycznych istnieje większa możliwość kontaktu z wydzielinami chorego, stosunkowo często dochodzi do zakażeń wśród personelu medycznego.

Wirus SARS – czynnik etiologiczny ciężkiego ostrego zespołu oddechowego (SARS od ang. Severe acute respiratory syndrome).

Jest to RNA wirus należący do koronawirusów. Średnica cząsteczki wirusa wynosi 70-100 nm, a genom zawiera 29751 lub 29727 nukleotydów (w zależności od szczepu) i jest to największy znany RNA-wirus. Ponieważ cały genom wirusa został odczytany, wiemy, że w 50-60% jest on identyczny z innymi koronawirusami.

Pierwsze zachorowania wystąpiły w listopadzie 2002 roku w mieście Foshan w prowincji Guangdong w Chinach. Stopniowo doszło do rozprzestrzenienia choroby na inne rejony Chin, inne kraje Azji, a potem, drogą podróży lotniczych, inne kraje świata. Przypuszcza się, że do pierwotnego zachorowania doszło w wyniku kontaktu ze zwierzętami trzymanymi w klatkach na targu. Stwierdzono zakażenie cywet, fretek i kotów wirusem SARS.

Do lipca 2003 roku zanotowano na świecie 8439 zachorowań, z czego u 812 chorych zakończyły się one śmiercią. 16 kwietnia 2003 roku WHO (Światowa Organizacja Zdrowia) ogłosiła, że czynnikiem chorobotwórczym wywołującym SARS, jest wirus należący do koronawirusów – wirus SARS.

Różnice w budowie i innych cechach morfologicznych, a także klinicznym przebiegu zachorowań, pozwalają stwierdzić, że jest to nowy wirus, odmienny od dotychczas znanych koronawirusów, które u człowieka powodują łagodnie przebiegające infekcje dróg oddechowych i przewodu pokarmowego. Przypuszcza się, że do powstania nowego wirusa mogło dojść w wyniku transdukcji obcych genów lub rekombinacji z innymi koronawirusami.

Czas wylęgania: 2-10 dni, maksymalnie do 14-20 dni.

Wirusa wyhodowano z wydzielin z dróg oddechowych, w ślinie może się znajdować 100 mln cząstek wirusa w 1 ml. Niewielkie ilości wirusa można stwierdzić w moczu i surowicy.

Przeciwciała przeciwwirusowe w klasie IgG zaczynają się pojawiać w surowicy ok. 9-10 dnia od zakażenia. Do celów diagnostycznych zaleca się oznaczanie w surowicy w 21. i 28. dniu od początku choroby.

Do zakażenia dochodzi najczęściej drogą kropelkową, a także przez kontakt zakaźnego materiału z błonami śluzowymi. Udowodniona jest możliwość zakażenia przez kontakt z kałem osoby chorej. Ponieważ przy wykonywaniu procedur medycznych istnieje większa możliwość kontaktu z wydzielinami chorego, stosunkowo często dochodzi do zakażeń wśród personelu medycznego.

Vi rút SARS, đôi khi được rút ngắn thành SARS-CoV, là vi rút gây ra hội chứng hô hấp cấp tính nặng (SARS).[1] Vào ngày 16 tháng 4 năm 2003, sau khi dịch SARS bùng phát ở châu Á và các trường hợp thứ phát ở nơi khác trên thế giới, Tổ chức Y tế Thế giới (WHO) đã đưa ra một thông cáo báo chí nói rằng coronavirus được xác định bởi một số phòng thí nghiệm là nguyên nhân chính thức của SARS. Các mẫu virus đang được giữ trong các phòng thí nghiệm ở thành phố New York, San Francisco, Manila, Hồng Kông và Toronto.

Vào ngày 12 tháng 4 năm 2003, các nhà khoa học làm việc tại Trung tâm Khoa học bộ gen Michael Smith ở Vancouver, British Columbia đã hoàn thành việc lập bản đồ trình tự gen của một coronavirus được cho là có liên quan đến SARS. Nhóm nghiên cứu được dẫn dắt bởi Tiến sĩ Marco Marra và hợp tác với Trung tâm Kiểm soát Bệnh tật British Columbia và Phòng thí nghiệm Vi sinh Quốc gia ở Winnipeg, Manitoba, sử dụng các mẫu từ các bệnh nhân bị nhiễm bệnh ở Toronto. Bản đồ, được WHO ca ngợi là một bước tiến quan trọng trong việc chống lại SARS, được chia sẻ với các nhà khoa học trên toàn thế giới thông qua trang web của GSC (xem bên dưới). Bác sĩ Donald Low của Bệnh viện Mount Sinai ở Toronto mô tả khám phá này được thực hiện với "tốc độ chưa từng thấy".[2] Trình tự của SARS coronavirus đã được xác nhận bởi các nhóm độc lập khác.

SARS coronavirus là một trong một số loại virus được WHO xác định là nguyên nhân có thể gây ra dịch bệnh trong tương lai trong kế hoạch mới được phát triển sau dịch Ebola để nghiên cứu và phát triển khẩn cấp trước và trong khi dịch sang các xét nghiệm chẩn đoán, vắc-xin và thuốc mới.[3][4]

Vi rút SARS, đôi khi được rút ngắn thành SARS-CoV, là vi rút gây ra hội chứng hô hấp cấp tính nặng (SARS). Vào ngày 16 tháng 4 năm 2003, sau khi dịch SARS bùng phát ở châu Á và các trường hợp thứ phát ở nơi khác trên thế giới, Tổ chức Y tế Thế giới (WHO) đã đưa ra một thông cáo báo chí nói rằng coronavirus được xác định bởi một số phòng thí nghiệm là nguyên nhân chính thức của SARS. Các mẫu virus đang được giữ trong các phòng thí nghiệm ở thành phố New York, San Francisco, Manila, Hồng Kông và Toronto.

Vào ngày 12 tháng 4 năm 2003, các nhà khoa học làm việc tại Trung tâm Khoa học bộ gen Michael Smith ở Vancouver, British Columbia đã hoàn thành việc lập bản đồ trình tự gen của một coronavirus được cho là có liên quan đến SARS. Nhóm nghiên cứu được dẫn dắt bởi Tiến sĩ Marco Marra và hợp tác với Trung tâm Kiểm soát Bệnh tật British Columbia và Phòng thí nghiệm Vi sinh Quốc gia ở Winnipeg, Manitoba, sử dụng các mẫu từ các bệnh nhân bị nhiễm bệnh ở Toronto. Bản đồ, được WHO ca ngợi là một bước tiến quan trọng trong việc chống lại SARS, được chia sẻ với các nhà khoa học trên toàn thế giới thông qua trang web của GSC (xem bên dưới). Bác sĩ Donald Low của Bệnh viện Mount Sinai ở Toronto mô tả khám phá này được thực hiện với "tốc độ chưa từng thấy". Trình tự của SARS coronavirus đã được xác nhận bởi các nhóm độc lập khác.

SARS coronavirus là một trong một số loại virus được WHO xác định là nguyên nhân có thể gây ra dịch bệnh trong tương lai trong kế hoạch mới được phát triển sau dịch Ebola để nghiên cứu và phát triển khẩn cấp trước và trong khi dịch sang các xét nghiệm chẩn đoán, vắc-xin và thuốc mới.

嚴重急性呼吸道綜合症冠狀病毒(英文簡稱:SARS-CoV)是一種可以致嚴重急性呼吸系統綜合症的冠狀病毒。冠狀病毒可分為很多種類,其中包括可能導致輕微疾病的病毒如傷風,它亦可引致嚴重的疾病,如嚴重急性呼吸系統綜合症 (沙士)。冠狀病毒有三種主要類別,包括:alpha (α), beta (β) 和gamma (γ),而此病毒屬於beta 類別。[1]是通过菊头蝠传播到人类的[2]。

嚴重急性呼吸道綜合症冠狀病毒(英文簡稱:SARS-CoV)是一種可以致嚴重急性呼吸系統綜合症的冠狀病毒。冠狀病毒可分為很多種類,其中包括可能導致輕微疾病的病毒如傷風,它亦可引致嚴重的疾病,如嚴重急性呼吸系統綜合症 (沙士)。冠狀病毒有三種主要類別,包括:alpha (α), beta (β) 和gamma (γ),而此病毒屬於beta 類別。是通过菊头蝠传播到人类的。

SARSコロナウイルス(サーズコロナウイルス)(英: SARS coronavirus,SARS-CoV)は、重症急性呼吸器症候群 (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome, SARS) の病原体として同定されたコロナウイルスである。通称SARSウイルス。飛沫感染により広がるとみられている。

SARSコロナウイルス(サーズコロナウイルス)(英: SARS coronavirus,SARS-CoV)は、重症急性呼吸器症候群 (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome, SARS) の病原体として同定されたコロナウイルスである。通称SARSウイルス。飛沫感染により広がるとみられている。

SARS 관련 코로나바이러스(영어: Severe acute respiratory syndrome–related coronavirus, SARSr-CoV, SARS-CoV)는 인간과 박쥐를 비롯한 포유류에 감염시키는 코로나바이러스의 한 종류이다.[1][2] 두 바이러스가 인간에게 질병을 일으키는 것으로 잘 알려져있다. SARS-CoV는 2002년부터 2004년에 걸쳐 중증급성호흡기증후군 (SARS)의 발발 원인이 되었으며, SARS-CoV-2는 2019년 말부터 COVID-19의 대유행을 일으켰다.

SARS 관련 코로나바이러스(영어: Severe acute respiratory syndrome–related coronavirus, SARSr-CoV, SARS-CoV)는 인간과 박쥐를 비롯한 포유류에 감염시키는 코로나바이러스의 한 종류이다. 두 바이러스가 인간에게 질병을 일으키는 것으로 잘 알려져있다. SARS-CoV는 2002년부터 2004년에 걸쳐 중증급성호흡기증후군 (SARS)의 발발 원인이 되었으며, SARS-CoV-2는 2019년 말부터 COVID-19의 대유행을 일으켰다.