en

names in breadcrumbs

The Spanish imperial eagle (Aquila adalberti), also known as the Iberian imperial eagle, the Spanish eagle or Adalbert's eagle, is a species of eagle native to the Iberian Peninsula. The binomial commemorates Prince Adalbert of Bavaria. Due to its distinct "epaulettes", old literature often referred to this species as the white-shouldered eagle.[3]

Formerly,[4] the Iberian imperial eagle was considered to be a subspecies of the eastern imperial eagle, but is now widely recognised as a separate species due to differences in morphology,[5] ecology,[6] and molecular characteristics.[7][8]

This is a large raptor and quite large eagle, broadly similar in size to its cousin, the eastern imperial eagle, which is found in a considerably different distributional range. Compared to sympatric largish booted eagles, it is somewhat smaller than the golden eagle and somewhat larger than the Bonelli's eagle. Spanish imperial eagle can weigh from 2.5 to 4.8 kg (5.5 to 10.6 lb). The average weight of males in a sample of 10 was 3.19 kg (7.0 lb) while that of 17 females was found to be 3.43 kg (7.6 lb). Meanwhile, another sample of 10 unsexed adults weighed an average of 3.93 kg (8.7 lb). Thus, the Spanish imperial eagle weighs about 10% more on average than the eastern imperial eagle and rivals the considerably longer-winged and longer-tailed wedge-tailed eagle as the third heaviest member of the Aquila genus behind the golden and Verreaux's eagles. This species has a total length of 72 to 85 cm (28 to 33 in) and a wingspan of 177 to 220 cm (5 ft 10 in to 7 ft 3 in).[9][10][11][12][13] A typical wingspan for a male is reportedly about 190 cm (6 ft 3 in) while for a female may be about 210 cm (6 ft 11 in).[14]

The adult resembles the eastern imperial eagle and can superficially suggest the golden eagle (especially when distantly seen), but is overall a darker color than either, a rich blackish-brown which extends all the way from the throat down to the belly. Like the eastern imperial, the adult has a broad distinctive white band on the shoulder and leading edge of the wing, which is even more pronounced in the Spanish than in the eastern species, and a much paler tawny color on the nape and crown, unlike the golden-yellow color on a similar area in the golden eagle. The juvenile Spanish imperial eagle is very different from adults and other large raptors in this range, being overall a uniform pale straw-sandy colour, contrasting with broad black bands on both the upper and lower sides of the wings. It has a relatively longer neck, and generally much flatter wing profile in flight than the upturned dihedral typical of a golden eagle.[15]

The species occurs in central and south-west Spain and adjacent areas of Portugal, in the Iberian peninsula. Its stronghold is in the dehesa woodlands of central and south-west Spain, such as in Extremadura, Ciudad Real and areas in the north of Huelva and Seville's Sierra Norte. The Spanish imperial eagle is a resident species, unlike the partially migratory eastern imperial eagle.[15] Stable occurrence in Morocco is disputed[16] but immature birds during the dispersion period regularly visit Morocco.[17]

Rising numbers of vagrant birds born in Spain and then electrocuted in Morocco have been noted;[18] some areas used by the species in Morocco could be becoming sort of a "drain" in terms of the species recovery and this is due to the fact that the country stands in a similar situation as Spain was in the early 1980s when it comes to insulation of transmission towers.[19] Vagrant birds have even reached Mauritania and Senegal.[20] North of its natural range, vagrants have reached as far as the Netherlands in one rare occasion.[21]

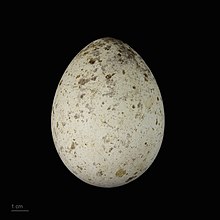

Nesting habitat is usually dry, mature woodlands, which they utilize for nesting and seclusion, but nests are most often fairly close to shrubby openings and wetland areas where prey is more likely to be concentrated. A shy species toward man, they normally nest only where human disturbance is quite low.[22] Like most raptors, they are highly territorial and tend to maintain a stable home range. Spanish imperial eagles nest from February to April. The nesting pair will construct a nest of as much as 1.5 m (4.9 ft) across at first build, which will increase in time, especially in mature Quercus suber or pine trees. Clutch size is usually two to three eggs, with an incubation period of about 43 days, but on average about 1.23-1.4 fledglings are produced per nest. Nestling mortality is usually due to human disturbance and destruction and nest collapses, secondarily due to predation and siblicide. Fledging is reached at 63–77 days of age but juveniles can linger for an extremely long period, to at least 160 days after fledging.[15][23][24]

It feeds mainly on European rabbits, which comprised about 58% of this species' diet before myxomatosis and rabbit haemorrhagic disease greatly reduced the rabbit's native Iberian population. As rabbit population crashed they've been recorded feeding on a wide range of vertebrates with varied success depending upon prey populations and may become semi-specialized hunters of water birds especially Eurasian coots, ducks and geese, also taking some numbers of partridges, pigeons and crows and any other bird they happen to encounter that is vulnerable to ambush. More than 60 bird species are known in be included in their prey spectrum. Several mammals may too be taken occasionally including various rodents, hares, mustelids, hedgehogs and even other large predators such as red foxes or—rarely, since they are not typically present in the eagle's habitat—domestic cats and small dogs. Rarely, reptiles or even fish may also be preyed upon. The largest prey taken by this species may easily exceed 3.3 kg (7.3 lb), such as foxes, greylag geese or white storks, but mean prey mass is relatively low, especially in areas with fewer rabbits. One study reported mean prey mass as 450 g (0.99 lb) locally, though average prey size has also been reported more highly.[11][25]

The Spanish imperial eagle is one of several rabbit-favoring birds of prey in Spain along with the similarly specialized Iberian lynx. This species is largely segregated by habitat from other eagles that specialize on rabbits here to lessen direct competition, as the imperial eagle favors woods, whereas the golden and Bonelli's eagles tend to dwell in much rockier areas. However, Spanish imperial eagles frequently quarrel over food with various raptors, even much larger vultures, and the raptors may at times try to kill the young of one another. In one case, in protection their own nest, an adult Spanish imperial eagle even killed a cinereous vulture, the largest accipitrid in the world. Healthy, free-flying Spanish imperial eagles are apex predators, being mostly free of natural predators themselves but they do sometimes kill each other in conflicts and rarely interspecies conflicts may too be fatal. When protected from human persecution and far from threats such as powerlines, adult mortality can be as low as 3–5.4% annually.[11][26][27][28]

The species is classified as Vulnerable by IUCN.[1] Threats include loss of habitat, human encroachment, collisions with pylons (at some point in the early 1980s, powerlines were responsible for 80% of deaths among birds in their first year of life)[29] and illegal poisoning. There has also been a decline in the species' main prey: rabbits have been kept at bay or even declined in some of the areas where the eagle is or could be present as a result of myxomatosis and, most recently, rabbit haemorrhagic disease.[19]

By the 1960s it had become a critically endangered species, with only 30 pairs remaining, all located in Spain. Following conservation efforts, recovery began in the 1980s at a rate of five new breeding pairs per year up to 1994. Imperial eagles were nearly wiped out.[1][30] In 2011, the species's global population had increased to 324 pairs, with 318 pairs in Spain. The species recolonised Portugal in 2003, after an absence of breeding activity for over 20 years, and has been slowly increasing since, with six breeding pairs located in 2011 and nine located in 2012. The population in Spain showed an average annual increase of c. 7% between 1990 and 2011. These positive trends are largely attributed to mitigation measures to reduce mortality associated with powerlines, supplementary feeding, reparation of nests, reintroductions and decreases in the disturbance of breeding birds, although some of the observed increases may be due to more thorough searches within its range.[1][31]

The Spanish imperial eagle (Aquila adalberti), also known as the Iberian imperial eagle, the Spanish eagle or Adalbert's eagle, is a species of eagle native to the Iberian Peninsula. The binomial commemorates Prince Adalbert of Bavaria. Due to its distinct "epaulettes", old literature often referred to this species as the white-shouldered eagle.

Formerly, the Iberian imperial eagle was considered to be a subspecies of the eastern imperial eagle, but is now widely recognised as a separate species due to differences in morphology, ecology, and molecular characteristics.