en

names in breadcrumbs

Influenzavirus A (Influenza A virus) és un dels virus que causa la grip (influenza) en els ocells i alguns mamífers i és l'única espècie del grup de virus influenzavirus A. Influenzavirus A és un gènere dins la família de virus Orthomyxoviridae. Les soques de tots els subtipus d'influenza A virus han estat aïllats d'ocells silvestres, encar que la malaltia no és comuna. Alguns aïllats (primary isolates) del virus influenza A causen malalties greus tant en l'aviram domèstic com, rarament, en humans.[1] Ocasionalment els virus es transmeten dels ocells silvestres aquàtics a l'aviram domèstic i poden causar un brot o donar lloc a pandèmies de grip humana.[2][3]

Tots els subtipus coneguts d'aquest virus són endèmics en ocells, la majoria dels subtipus no causen endèmies fora dels ocells, per la qual cosa es considera que bàsicament és una grip d'ocells.[4]

Quan es produeix un canvi antigen causa la grip episòdica en humans i això es produeix en cicles d'entre 10 i 15 anys. En els humans es desenvolupa generalment una grip més virulenta que la produïda per les variacions antigèniques menors, que també ocorren en el Influenzavirus B (de vegades ocorren de manera simultània) i condicionen les grips estacionals, que succeeixen gairebé tots els anys.

L'estructura física de tots els subtipus de virus de influenzavirus A és semblant. Els virions embolcallats poden ser de forma esfèrica o filamentosa.[5]

El genoma de l'influenzavirus A està contingut en 8 cadenes simples (no aparellades) que codifiquen 10 proteïnes: HA, NA, NP, M1, M2, NS1, PA, PB1, PB1-F2, PB2. La naturalesa segmentada del genoma permet l'intercanvi del repertori genètic sencer entre les diferents soques virals durant la cohabitació cel·lular, per això se'n diuen recombinants. Els 8 segments o cadenes d'ARN són:

En ordre de mortalitat causada:

Influenzavirus A (Influenza A virus) és un dels virus que causa la grip (influenza) en els ocells i alguns mamífers i és l'única espècie del grup de virus influenzavirus A. Influenzavirus A és un gènere dins la família de virus Orthomyxoviridae. Les soques de tots els subtipus d'influenza A virus han estat aïllats d'ocells silvestres, encar que la malaltia no és comuna. Alguns aïllats (primary isolates) del virus influenza A causen malalties greus tant en l'aviram domèstic com, rarament, en humans. Ocasionalment els virus es transmeten dels ocells silvestres aquàtics a l'aviram domèstic i poden causar un brot o donar lloc a pandèmies de grip humana.

Tots els subtipus coneguts d'aquest virus són endèmics en ocells, la majoria dels subtipus no causen endèmies fora dels ocells, per la qual cosa es considera que bàsicament és una grip d'ocells.

Quan es produeix un canvi antigen causa la grip episòdica en humans i això es produeix en cicles d'entre 10 i 15 anys. En els humans es desenvolupa generalment una grip més virulenta que la produïda per les variacions antigèniques menors, que també ocorren en el Influenzavirus B (de vegades ocorren de manera simultània) i condicionen les grips estacionals, que succeeixen gairebé tots els anys.

Viry z čeledě Orthomyxoviridae se podle vnitřního, druhově specifického nukleoproteinového antigenu rozdělují do rodů Influenza virus A, Influenza virus B a Influenza virus C.[1] Chřipkové virusy typu influenza A se vyskytují u lidí i zvířat, typy B a C pouze u lidí. Standardní nomenklatura chřipkových virů A byla navržena v roce 1971 a upravena WHO v roce 1980. Jejich označení zahrnuje typ viru, původního hostitele, geografickou oblast, číslo kmene, rok izolace a subtyp hemaglutininu (HA) a neuraminidázy (NA). Např. influenza virus typu A izolovaný u krůt v roce 1968 ve Wisconsinu, který má HA subtypu 8 a NA subtypu 4, je označován jako A/turkey/Wisconsin/1/68 (H8N4).

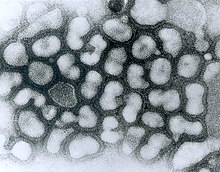

Viriony influenzových virů typu A (IVA) jsou sférické obalené částice dosahující průměrné velikosti 80-120 nm; existují i vláknité formy rozličné délky. Nukleokapsida s helikální symetrií je uzavřena ve dvouvrstevném lipidovém obalu, který obsahuje povrchové projekce délky 10-12 nm. Tyto povrchové projekce představují 2 důležité glykoproteiny kódované virem – trimer hemaglutinin (HA) a tetramer neuraminidázu (NA).

Hemaglutinin je membránový protein, obsahující hlavní povrchový antigen (H) viru. Skládá se ze dvou disulfidickou vazbou spojených řetězců (HA1 a HA2), které vznikají z prekurzoru hemaglutininu proteolytickým štěpením. Biologická aktivace HA buněčnými proteázami je nezbytným předpokladem pro infekciozitu viru, protože teprve HA2 navozuje fúzi obalu viru na plasmatickou membránu buňky. Hemaglutinin, kromě toho že odpovídá za přilnutí virionu k receptorům buněčného povrchu hostitelské buňky, vyvolává také hemaglutinaci erytrocytů a indukuje tvorbu neutralizačních a hemaglutinaci inhibujících protilátek.

Neuraminidáza obsahuje další důležitý antigen (N) viru. Je to enzym, který hydrolyticky štěpí glykosidovou vazbu mezi kyselinou sialovou (N-acetylneuraminovou) a D-galaktózou nebo D-galaktózoaminem na povrchu napadené buňky a spolupůsobí tak s HA při adsorpci a průniku viru do buňky. Uplatňuje se také při uvolňování nově vzniklých virových partikulí z buněk a při eluci viru z erytrocytů. Protilátky proti neuraminidáze pravděpodobně brání šíření infekce mezi buňkami; nemají ale neutralizační aktivitu. Na základě rozdílných antigenních vlastností HA a NA se u ptačích IVA rozlišuje 16 subtypů HA a 9 subtypů NA, které se mohou vyskytovat v různých vzájemných kombinacích.

Pod virovým obalem leží velký strukturální matrixový protein M1 obalující molekulu RNA, nukleoprotein (NP) tvořící kapsidu a 3 velké strukturální proteiny – polymerázy PB1 a PB2 a kyselý protein PA, nezbytné pro replikaci RNA a její transkripci. Virový genom představuje 8 segmentů (genů) jednovláknové RNA s negativní polaritou (-). Segmenty 1-3 a 5 kódují informace pro syntézu RNA a nukleokapsidy, segmenty 4 a 6 pro HA a NA, segment 7 pro matrixový protein M1 a segment 8 pro nestrukturální proteiny (NS1 a NS2). Segmenty RNA mohou být elektroforeticky separovány podle jejich migrační rychlosti, čehož se využívá v genetických, epizootologických i diagnostických studiích.[2]

Segment 7 od něhož se odvíjí transkript pro matrixový protein M1 je po splicingu označován jako M2. Dlouhou dobu se o jeho důležitosti vedly spory. Jelikož se jedná o hydrofobní protein, a proto k jeho sledování nebylo možné použít MRI, byla použita technika nukleárně magnetické rezonanční spektroskopie, která ukázala, že protein M2 mající tvar kanálu s póry na obou koncích musí být aktivován kyselým prostředím. Samotný proces je zahájen aminokyselinami tryptofanem a histidinem. Histidin funguje jako přenašeč protonů z buňky do nitra viru, zatímco tryptofan slouží jako vrátný, který otevírá bránu při přiblížení protonu. Jedná se o nezbytný krok k replikaci viru[3].

Přibližné složení chřipkového virionu je 0,8-1,1 % RNA, 70-75 % bílkovin, 20-24 % lipidů a 5-8 % cukrů. Lipidy jsou lokalizovány ve virové membráně většinou ve formě fosfolipidů, cukry pak ve formě glykoproteinů nebo glykolipidů.[4]

Genom je lineární, segmentovaný a enkapsidovaný nukleoproteinem NP. Jeho 8 segmentů (velikost se pohybuje od 890 do 2341 bp) kóduje 11 proteinů. Celková velikost je 13,5 kbp.

Influenzavirus A způsobuje onemocnění chřipku u savců a chřipkové infekce ptáků.

K pomnožení chřipkových virů se nejčastěji používají kuřecí embrya, vzhledem k jejich vysoké citlivosti. Virusy lze adaptovat na laboratorní zvířata. Všechny kmeny viru chřipky aglutinují ptačí a některé savčí erytrocyty; jsou však rozdíly ve schopnosti aglutinovat červené krvinky určitého zvířecího druhu. K biologickým pokusům se nejčastěji používají krůťata, kachňata a kuřata.

Důležitou biologickou vlastností chřipkových virů A je schopnost vytvářet antigenní variace – antigenní posun (drift) a antigenní zvrat (shift). Antigenní posun je způsobován bodovými mutacemi částí genomu kódujících HA a NA a projevuje se malými antigenními a strukturálními změnami obou glykoproteinů. Antigenní zvrat vzniká vzájemnou výměnou segmentů nově se tvořících genomů virů (rekombinace, angl. genetic reassortment – přeuspořádání) po předchozí infekci vnímavé buňky (embrya, hostitele) dvěma nebo i více antigenně odlišnými viry. Tak dochází v přírodě ke vzniku antigenně zcela „nových“ chřipkových virů. Na vzniku antigenních variací chřipkových virů se nejčastěji z ptáků podílejí divoké kachny.

Viry z čeledě Orthomyxoviridae se podle vnitřního, druhově specifického nukleoproteinového antigenu rozdělují do rodů Influenza virus A, Influenza virus B a Influenza virus C. Chřipkové virusy typu influenza A se vyskytují u lidí i zvířat, typy B a C pouze u lidí. Standardní nomenklatura chřipkových virů A byla navržena v roce 1971 a upravena WHO v roce 1980. Jejich označení zahrnuje typ viru, původního hostitele, geografickou oblast, číslo kmene, rok izolace a subtyp hemaglutininu (HA) a neuraminidázy (NA). Např. influenza virus typu A izolovaný u krůt v roce 1968 ve Wisconsinu, který má HA subtypu 8 a NA subtypu 4, je označován jako A/turkey/Wisconsin/1/68 (H8N4).

Influenzavirus A er en envelop negativt enkeltstrenget segmenteret RNA-virus. Influenza A tilhører Orthomyxoviridae-familien. Denne forårsager influenza blandt fugle og visse pattedyr, samt mennesker.

Stammer fra de forskellige serotyper af influenza A er alle blevet isoleret fra vilde fugle, selvom de sjældent forårsager sygdom blandt disse. Visse serotyper fører dog til alvorlig sygdom blandt husholdte fjerkræ, og i sjældne tilfælde mennesker.[1] Af og til overføres virus fra vilde havefugle til husholdte fjerkræ, som kan medføre større spredning, og give anledning til humane pandemier.[2][3]

Influenza A serotyperne navngives efter deres H-nummer (dvs. type af hæmagglutinin) og N-nummer (dvs. type af neuramidase). Der er 17 forskellige H-atnigener (H1 til H17) og 9 forskellige N-antigener (N1 til N9). Den nyeste H-antigen type (H17) blev identificeret af forskere, som isolerede denne fra storflagermus i 2012.[4][5][6]

Hver virale serotype har muteret til forskellige stammer med forskellige patogene egenskaber; nogle er patogene for en art, mens andre er patogene til flere arter.

Influenzavirus A er en envelop negativt enkeltstrenget segmenteret RNA-virus. Influenza A tilhører Orthomyxoviridae-familien. Denne forårsager influenza blandt fugle og visse pattedyr, samt mennesker.

Stammer fra de forskellige serotyper af influenza A er alle blevet isoleret fra vilde fugle, selvom de sjældent forårsager sygdom blandt disse. Visse serotyper fører dog til alvorlig sygdom blandt husholdte fjerkræ, og i sjældne tilfælde mennesker. Af og til overføres virus fra vilde havefugle til husholdte fjerkræ, som kan medføre større spredning, og give anledning til humane pandemier.

Influenza A serotyperne navngives efter deres H-nummer (dvs. type af hæmagglutinin) og N-nummer (dvs. type af neuramidase). Der er 17 forskellige H-atnigener (H1 til H17) og 9 forskellige N-antigener (N1 til N9). Den nyeste H-antigen type (H17) blev identificeret af forskere, som isolerede denne fra storflagermus i 2012.

Hver virale serotype har muteret til forskellige stammer med forskellige patogene egenskaber; nogle er patogene for en art, mens andre er patogene til flere arter.

Die Gattungen Alpha-, Beta-, Gamma- und Deltainfluenzavirus aus der Familie Orthomyxoviridae sind behüllte[3] Viren mit einer einzelsträngigen, segmentierten RNA von negativer Polarität als Genom. Unter den Gattungen finden sich auch die Erreger der Influenza oder „echten“ Grippe. Zu medizinischen Aspekten der Influenzaviren und Grippe-Erkrankung siehe Influenza. Gemäß International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV, Stand: November 2018) haben alle vier Gattungen jeweils nur eine Spezies, und zwar der Reihe nach Influenza A-Virus (FLUAV) bis Influenza D-Virus (FLUDV).[4]

Das innerhalb der Lipidhülle (genauer: Virusmembran) befindliche Ribonukleoprotein des Virusteilchens (Virions), besitzt eine ungefähr helikale Symmetrie. Das Ribonukleoprotein ist ein Komplex aus dem Genom des Virus, den strukturellen (M1 und NP) und den replikationsrelevanten Proteinen (PA, PB1, PB2).

Im Transmissionselektronenmikroskop sieht man alle Gattungen dieses Virus als kugelige oder sphärisch ellipsoide (rundliche bis eiförmige), gelegentlich auch filamentöse (fadenförmige), umhüllte Viruspartikel mit einem Durchmesser von 80 bis 120 nm,[5] in deren Lipidhülle eine variierende Anzahl der drei Membranproteine HA, NA und M2 bei Influenza-A-Viren bzw. der zwei Membranproteine HA und NA bei Influenza-B-Viren (IBV) oder der Hämagglutinin-Esterase-Faktor HEF und das Matrixprotein CM2 bei Influenza C eingelagert sind. Die Glykoproteine HA und NA ragen als 10 bis 14 nm lange Spikes oder Peplomere genannte Fortsätze über die Virusoberfläche von Influenza-A-Viren (IAV) hinaus. Dagegen ragt das M2 von Influenza A nur mit 24 Aminosäuren aus der Lipiddoppelschicht heraus und wird unter der Überdeckung des HA und NA kaum von Antikörpern im Zuge einer Immunreaktion erkannt. Bei den Influenza-A- und Influenza-B-Viren (FLUAV und FLUBV) sind daher genau zwei Typen dieser Spikes serologisch von besonderem Interesse: das Hämagglutinin (HA) und die Neuraminidase (NA), gegen die Antikörper nach einer Erkrankung und in geringerem Umfang auch nach einer Impfung mit einem Influenzaimpfstoff gegen Influenza A und B entstehen. Diese Antikörper können zur serologischen Klassifizierung der 18 HA- und 11 NA-Subtypen von Influenza-A-Viren herangezogen werden (nach aktuellem Stand 2017, siehe hierzu auch A/H18N11).

Das Genom fast aller Influenzaviren besteht aus acht RNA-Abschnitten (Segmenten) negativer Polarität, bei Influenza C sind es nur sieben. Diese acht RNA-Moleküle enthalten die genetische Information, die für die Vermehrung und den Zusammenbau der Viruspartikel benötigt wird und kommen im Virion bevorzugt einzelsträngig vor.[5] Ebenso kommt in einem Virion nur eine Kopie des Genoms vor.[6] Die Segmentierung des Genoms ist auch für die erhebliche Steigerung der genetischen Veränderlichkeit (Variabilität) der Influenzaviren über die Fähigkeit zur genetischen Reassortierung (auch Antigen-Shift) verantwortlich, da bei einer Superinfektion einer Zelle (mit einem anderen Influenzastamm) ein Austausch der Segmente erfolgen kann. Durch das RNA-basierte einzelsträngige Genom kommen häufig Punktmutationen vor (sogenannter Antigen-Drift), denn die RNA-Polymerasen von RNA-Viren besitzen keine Exonuklease-Funktion zur Korrektur von Kopierfehlern. Durch beide Mechanismen entstehen Fluchtmutationen zur Umgehung der Immunantwort, während die Funktionen des Virions erhalten bleiben sollen. Das Genom erhält die stärkste Anpassung durch den vom Immunsystem ihrer Reservoirwirte erzeugten Selektionsdruck, wobei der Erhalt der Funktionen der Proteine für eine hohe Reproduktions- und Infektionsrate notwendig ist.

Die acht verschiedenen RNA-Segmente (HA, NA, M, NP, PA, PB1, PB2 und NS) kodieren bei Influenza A üblicherweise zehn, gelegentlich elf virale Proteine:[7] das Hämagglutinin (HA), die Neuraminidase (NA), das Nukleoprotein (NP), die Matrixproteine (M1) und (M2), die RNA-Polymerase (PA), die Polymerase-bindenden Proteine (PB1, PB2 und vereinzelt auch PB1-F2) und die Nichtstrukturproteine (NS1 und NS2). Das Genom von Influenza C besitzt nur sieben Segmente, es fehlt die Neuraminidase, da deren Funktion mit der Hämagglutinin-Funktion im HEF integriert ist. Aus den RNA-Segmenten M, NS und in manchen Stämmen auch aus PB1 entstehen bei Influenza A durch alternatives Spleißen jeweils zwei Proteine, M1 und M2 bzw. NS1 und NS2 bzw. PB1 und PB1-F2. Am 5'- und am 3'-Ende jedes Segments befindet sich im Virion ein Polymerasekomplex aus PA, PB1 und PB2.[8]

Das Hämagglutinin (HA) ist ein Lektin und bewirkt die Verklumpung (Agglutination) von Erythrozyten und vermittelt bei der Infektion die Anheftung des Virusteilchens (Virions) an eine Wirtszelle. Das Ankoppeln des Hämagglutinins an eine Zelle geschieht durch eine Anlagerung eines Teils des Hämagglutininmoleküls an Sialinsäuren (SA) auf Proteinen der Wirtszellenhülle, die als Rezeptoren (SA-Rezeptoren) fungieren.[9] Diese Sialinsäuren sind bei Vögeln gehäuft α2,3-verknüpft und bei Säugern gehäuft α2,6-verknüpft.[10] Daneben unterscheiden sich die Verteilungen dieser Verknüpfungen in der Lunge in Säugern und Vögeln.[11] Jede Hämagglutininvariante passt dabei an einen bestimmten Wirtszellenrezeptor nach dem Schlüssel-Schloss-Prinzip, wobei jeder Wirt nur über einen Teil aller von Influenzaviren genutzten Rezeptoren verfügt. Diese Tatsache ist auch der Grund dafür, dass bestimmte Subtypen oder Virusvarianten mit ihrem speziellen Hämagglutinintyp bestimmte Wirte leicht infizieren und dabei eine Erkrankung auslösen können und andere prinzipiell mögliche Wirte wiederum nicht oder nur sehr eingeschränkt. Nach einer proteolytischen Aktivierung des von einer Zelle aufgenommenen Hämagglutinins durch zelluläre Serinpeptidasen und einer Ansäuerung des Endosoms bewirkt das Hämagglutinin in seiner zweiten Funktion als fusogenes Protein über seine Fusionsdomäne eine Fusion mit der endosomalen Membran zur Freisetzung des Ribonukleoproteins ins Zytosol. Das Hämagglutinin ist aus drei gleichen Proteinen aufgebaut (ein Homotrimer). Mittels Proteolyse wird jeder dieser drei Teile (Monomere) wiederum in zwei Polypeptidketten gespalten, die jedoch über eine Disulfidbrücke miteinander verbunden bleiben. Diese Spaltung ist bei der Entpackung der Viren für die Fusion der Virusmembran mit der Endosomenmembran zwingend notwendig, nicht jedoch für die Rezeptorbindung. Durch Mutationen, besonders in Hinblick auf mögliche Veränderungen des Hämagglutinins, kann sich die Infektionsgefahr für den einen oder anderen potentiellen Wirt erheblich ändern. Allerdings können die Viren die HA-Bindungsstelle nicht beliebig verändern, da bei einem Funktionsverlust der Wiedereintritt in Zellen nicht mehr erfolgen kann und somit die Infektkette unterbrochen wird.[10] Vor allem gegen das Hämagglutinin werden neutralisierende Antikörper ausgebildet, die eine erneute Infektion mit demselben Virusstamm verhindern. Daher sind neu auftretende Epidemien meistens von Änderungen im Hämagglutinin begleitet.[12]

Die Neuraminidase (NA) hat im Infektionsvorgang viele Funktionen, darunter eine enzymatische Funktion zur Abspaltung (Hydrolyse) der N-Acetylneuraminsäure (eine Sialinsäure) an zellulären Rezeptoren. Dadurch erfolgt die Freisetzung der durch die Replikation neu entstandenen Viren (Tochtervirionen aus den infizierten Zellen) und damit bei der Ausbreitung der Infektion sowohl innerhalb desselben Organismus als auch auf andere Organismen.[13] Außerdem verhindert die Neuraminidase ein Hämagglutinin-vermitteltes Anheften der Tochtervirionen an bereits infizierte Zellen, weil die infizierten Zellen durch die Neuraminidase auf ihrer Zelloberfläche kaum noch N-Acetylneuraminsäure auf ihrer Zelloberfläche tragen. Als Nebeneffekt wird der Schleim in der Lunge verflüssigt. Daneben verhindert die Neuraminidase, dass in einer infizierten Zelle während der Replikation ein Zelltodprogramm gestartet werden kann.[14][15] Oseltamivir, Zanamivir und Peramivir hemmen bei nicht-resistenten Influenza-A- und Influenza-B-Stämmen die Neuraminidase.

Das Matrixprotein 2 (M2) ist das kleinste der drei Membranproteine von Influenza-A-Viren. Bei Influenza A besteht M2 aus circa 97 Aminosäuren, wovon 24 Aminosäuren aus der Membran herausragen. Das Matrixprotein M2 ist bei Influenza-A-Viren ein Protonenkanal zur Ansäuerung des Inneren des Virions nach einer Endozytose, so dass die Fusionsdomäne des Hämagglutinins ausgelöst wird und eine Verschmelzung von Virus- und Endosomenmembran zur Freisetzung des Ribonukleoproteins ins Zytosol erfolgen kann.[6] Gleichzeitig bewirkt die Ansäuerung im Inneren des Virions eine Dissoziation des Matrixproteins 1 vom Ribonukleoprotein.[6] Bei Influenza B-Viren ist das Matrixprotein 2 (BM2) kein Hüllprotein, sondern ein lösliches Protein von circa 109 Aminosäuren.[16] Bei Influenza C ist das entsprechende Matrixprotein CM2, wie bei Influenza A, ein Ionenkanal. Amantadin und Rimantadin hemmen bei nicht-resistenten Influenza-A-Stämmen das Matrixprotein M2.

Als weitere im Virion befindliche Proteine (Strukturproteine, engl. structural proteins) existieren neben den Hüllproteinen die internen Proteine (engl. core proteins). Der Bereich zwischen Virusmembran und Ribonukleoprotein wird als Matrix oder Viruslumen (lat. lumen für ‚Licht‘) bezeichnet, da er im Transmissionselektronenmikroskop aufgrund einer niedrigeren Elektronendichte heller als das Ribonukleoprotein erscheint. An der Innenseite der Virusmembran befinden sich die zytosolischen Anteile der drei Membranproteine HA, NA und M2, sowie das Matrixprotein M1, welches die Virusmembran mit dem Ribonukleoprotein verbindet, bei Ansäuerung aber das Ribonukleoprotein freisetzt. Das Ribonukleoprotein besteht aus dem Nucleoprotein NP, den viralen RNA-Segmenten und den für die Replikation und Transkription notwendigen Proteinen des Polymerase-Komplexes (PA, PB1 und PB2, mit A für acide oder B für basisch bezeichnet, je nach ihren isoelektrischen Punkten).[17] Das Nucleoprotein NP bindet neben dem Matrixprotein M1 an die virale RNA und vermittelt über sein Kernlokalisierungssignal den Transport in den Zellkern.[18] NS2 kommt in geringen Mengen gelegentlich auch im Virion vor.[19]

Die regulatorischen Proteine NS1, NS2 und das bei manchen Stämmen auftretende PB1-F2 kommen nicht im Virion vor und werden daher als Nichtstrukturproteine bezeichnet. Das NS1 mindert durch seine Bindung an PDZ-Domänen die Interferon-Reaktion des Wirtes und somit die Immunreaktion.[20] Daneben verhindert NS1 das Ausschleusen wirtseigener mRNA aus dem Zellkern durch Bindung ihrer Cap-Struktur, wodurch die virale RNA vermehrt in Proteine translatiert werden.[21] NS2 vermittelt den Export viraler mRNA aus dem Zellkern.[22] PB1-F2 fördert die korrekte Lokalisation des PB1 im Zellkern und bindet an die Polymerase PA und fördert über den mitochondrialen Weg die Einleitung der Apoptose zur Verbesserung der Freisetzung der Tochtervirionen.[23]

Die Koevolution von Menschen und Viren (in diesem Falle von RNA-Viren) hat im Menschen antivirale Mechanismen hervorgebracht, die als Wirtsrestriktions- oder auch Resistenzfaktoren (engl. host restriction factors) bezeichnet werden. Hierzu zählen bei Influenzaviren der Myxovirus-Resistenzfaktor Mx1,[24] NOD-2,[25] die Toll-like Rezeptoren 3,[26] 7[27] und 8,[28] RIG-I,[26] der dsRNA-aktivierte Inhibitor der Translation DAI,[29] MDA5,[30] die Oligoadenylatsynthase OAS1,[31] das Nod-like Receptor Protein 3 (NLRP-3)[32] und die Proteinkinase R.[33]

Für den Replikationszyklus des Influenza-A-Virus sind mindestens 219 wirtseigene Proteine notwendig.[34]

Die Influenzaviren werden beim Menschen im Atemtrakt (Respirationstrakt) eines infizierten Individuums repliziert. Menschliche Grippeviren bevorzugen Zellen des Flimmerepithels. Im Gegensatz dazu vermehrt sich das Grippe-Virus bei Vögeln hauptsächlich in den Darmepithelzellen.[35]

Die Viren wandern bei ihrem Wirt durch das Mucin (Schleim) in die Epithelzellen, die als Wirtszellen dienen. Dafür, dass sie dabei nicht mit dem Schleim verkleben, sorgt die Neuraminidase, welche den Schleim verflüssigt.[36] Nach der Bindung des Hämagglutinins an eine N-Acetyl-Neuraminsäure auf einer Zelloberfläche erfolgt die Einstülpung des Virions durch Endozytose. Im Endosom schneiden zelluläre Serinproteasen das Hämagglutinin in seine aktivierte Form. Daneben sinkt der pH-Wert im Endosom, wodurch über das Ionenkanalprotein M2 das Innere des Virions angesäuert wird. Die Ansäuerung löst die Fusionsdomäne des Hämagglutinins aus, wodurch die Virusmembran mit der Endosomenmembran verschmilzt und das Ribonukleoprotein ins Zytosol freigesetzt wird, gleichzeitig löst sich M1 vom Ribonukleoprotein, wodurch die Kernlokalisierungssignale des NP im Ribonukleoprotein exponiert werden. Das Ribonukleoprotein wird auch durch einen zellulären Abbaumechanismus, das Aggregosom, vom Matrixprotein befreit, vermutlich unter Verwendung von zelleigenen Motorproteinen.[37] Über die Kernlokalisierungssequenz des Nukleoproteins erfolgt anschließend ein Import des Ribonukleoproteins in den Zellkern.[6]

Die Kopie der viralen RNA erfolgt bei IAV und IBV durch den viralen Polymerasekomplex – ein Heterotrimer aus den drei Proteinen PA, PB1 und PB2 – unter Verwendung der Ribonukleotide des Wirts.[38] Die Transkription zur Erzeugung der viralen mRNA erfolgt durch selten vorkommenden Mechanismus des Cap snatching.[39] Die mit 5'-methylierten Cap-Strukturen modifizierten zellulären mRNA werden von PB2 an der 7-Methylguanosingruppe gebunden und anschließend 10 bis 13 Nukleotide nach der Cap-Struktur durch PA geschnitten. Die kurzen Cap-tragenden Fragmente werden von PB1 gebunden und im RNA-Polymerase-Komplex als Primer für die Transkription viraler RNA verwendet. Der Polymerase-Komplex bindet dabei kurzfristig an die zelluläre RNA polymerase II.[39] Nebenbei wird dadurch die mRNA des Wirts zerlegt, so dass das Ribosom freier für die Synthese der viralen mRNA ist. Während die virale mRNA eine Cap-Struktur und eine Polyadenylierung trägt, hat die virale RNA der Replikation beides nicht.[40]

Durch das NS2-Protein wird die vervielfältigte virale RNA aus dem Zellkern ins Zytosol geschleust, wo nach der RNA-Vorlage am Ribosom Proteine hergestellt werden. Die strukturellen Proteine binden aneinander, der Polymerase-Komplex aus PA, PB1 und PB2 bindet an das 5'- und das 3'-Ende der viralen RNA und das NP-Protein bindet an die restliche virale RNA, wodurch sich das Ribonukleoprotein zusammenfügt.[39][41] Die viralen Hüllproteine HA und NA sammeln sich an der Zelloberfläche an den Lipid Rafts, nicht aber M2.[6] Das Ribonukleoprotein bindet an die Innenseite der Lipid Rafts. Der Mechanismus der Knospung ist noch nicht geklärt.[6] Influenzaviren sind lytische Viren. Sie induzieren einen programmierten Zelltod der Wirtszelle.[42]

In einer einzigen infizierten Wirtszelle können sich bis zu etwa 20.000 neue Influenzaviren bilden (englisch burst size ‚Berstgröße‘), bevor diese dann abstirbt und anschließend die freigesetzten Viren weitere Nachbarzellen infizieren. In infizierten Zellkulturen oder embryonierten Hühnereiern wurden virusstammabhängige Werte zwischen 1.000 und 18.755 Tochtervirionen pro Zelle ermittelt.[43][44][45] Diese produzieren dann ebenfalls jeweils viele Tausende neuer Viren. So erklärt sich auch die Schnelligkeit, mit der sich in der Regel diese virale Infektion im Körper eines Betroffenen ausbreitet.

Es gibt vier verschiedene Gattungen der Influenzaviren (Alpha bis Delta), welche mit den Gattungen Isavirus, Quaranjavirus und Thogotovirus alle zusammen zur Familie der Orthomyxoviren (Orthomyxoviridae) gehören.

In Fachkreisen wird jeder Virusstamm mit den Kennungen Typus, Ort der erstmaligen Isolierung (Virusanzucht), Nummer des Isolats, Isolierungsjahr (Beispiel: Influenza B/Shanghai/361/2002) und nur bei den A-Viren auch zusätzlich mit der Kennung des Oberflächenantigens benannt [Beispiel: Influenza A/California/7/2004 (H3N2)].[46] Ebenso werden Influenzaviren nach ihrem natürlichen Wirt benannt (Vogelgrippeviren, Schweinegrippeviren).[47] Allerdings werden die ausgelösten Grippen nur als Vogelgrippen oder Schweinegrippe bezeichnet, wenn die Infektion in dieser Wirtsspezies stattfindet, nicht aber beim Menschen.[47] Wenn der Mensch aufgrund einer Veränderung eines Influenzavirus zur häufiger infizierten Wirtsspezies wird, verwendet man die Schreibweise der Serotypen mit einem nachgestellten v (von engl. variant), z. B. H1N1v, H3N2v.[48]

Im Allgemeinen werden die Subtypen der Spezies Influenza-A-Virus (FLUA) in erster Linie serologisch eingeteilt. Dies geschieht nach dem Muster A/HxNx oder A/Isolierungsort/Isolat/Jahr (HxNx). Bisher wurden mindestens 18 H-Untertypen und 11 N-Untertypen erkannt.[52]

Die wichtigsten Oberflächenantigene beim Influenza-A-Virus für die Infektion des Menschen sind die Hämagglutinin-Serotypen H1, H2, H3, H5, seltener H7 und H9 und die Neuraminidase-Serotypen N1, N2, seltener N7, weshalb auch folgende Subtypen für den Menschen von besonderer Bedeutung sind:

Informationen zu Influenza-A-Subtypen bei Vögeln finden sich im Artikel Geflügelpest.

Die Spezies Influenza-B-Virus (FLUB) wird nach dem Ort des Auftretens in mehrere Stamm-Linien eingeteilt, z. B.:[63]

Die Unterschiede zwischen einzelnen Virusstämmen der Spezies Influenza-C-Virus (FLUC) sind gering. Eine Unterteilung in Subtypen findet sich beim NCBI.[70]

Die ersten Vertreter der Spezies Influenza-D-Virus (FLUD) wurden 2011 isoliert.[71] Diese Gattung scheint sehr nahe mit Influenza C verwandt zu sein, die Aufspaltung erfolgte offenbar erst vor einigen hundert Jahren,[72] das Genom hat daher ebenfalls sieben Segmente.[73] Es gibt gegenwärtig mindestens zwei Subtypen.[74] Hauptsächlich werden Rinder infiziert, aber auch Schweine. Eine Unterteilung in Subtypen findet sich beim NCBI.[75]

Eine Häufung von Punktmutationen in den Nukleotiden führt zu einer Veränderung der Erbinformationen (Gendrift). Die Punktmutationen entstehen bei Influenzaviren hauptsächlich durch die Ungenauigkeit des Polymerase-Komplexes. Betreffen solche Veränderungen die beiden Glykoproteine HA und NA (bzw. den sie kodierenden Bereich), bewirkt dies eine Änderung der Oberflächenantigene des Grippevirus (Antigendrift). Menschliche Antikörper und cytotoxische T-Zellen können immer nur eine solche Variante erkennen, ein nun unerkanntes Virus wird als Fluchtmutante bezeichnet. Diese eher kleinen Veränderungen sind der Grund dafür, dass ein Mensch mehrmals in seinem Leben mit einer anderen, nur geringfügig veränderten Virusvariante (Driftvariante) infiziert werden kann und dass sowohl Epidemien wie regional begrenzte Ausbrüche regelmäßig wiederkehren.

Daher ist es ein Ziel des Influenza-Impfstoffdesigns, breitneutralisierende Antikörper hervorzurufen. Nach mehreren überstandenen Infektionen mit unterschiedlichen Stämmen kommt es langfristig zu einem Anstieg der Titer von breitneutralisierenden Anti-Influenza-Antikörpern, möglicherweise aufgrund der hohen genetischen Variabilität der Influenzavirusstämme.[76] Ebenso wird versucht, die zelluläre Immunantwort auf konservierte Bereiche der viralen Proteine zu lenken, bei denen weniger Fluchtmutationen entstehen können. Die Mutationsrate des Influenzavirus A liegt bei 0,000015 Mutationen pro Nukleotid und Replikationszyklus.[77] Allerdings beeinflusst das bei einer Immunreaktion gebildete Repertoire an Antikörpern und zytotoxischen T-Zellen prägend ihre jeweilige Immundominanz, was die Anpassung der Immunreaktion bei späteren Infektionen mit veränderten Influenzaviren beeinflusst (Antigenerbsünde).

Wird ein Organismus gleichzeitig von zwei Virusvarianten infiziert (Doppelinfektion) oder es tauschen zwei Viren gleichen Ursprungs unterschiedlich mutierte Gensegmente aus (wobei im letzteren Fall die Veränderungen geringer ausfallen), so kann es zu einer Neuzusammenstellung unter den je acht Genomsegmenten der beteiligen Influenzaviren kommen, in dem einzelne oder mehrere RNA-Moleküle zwischen den Influenzaviren in einer doppelt infizierten Zelle ausgetauscht werden. Diesen Vorgang nennt man genetische Reassortierung, und sie kann im Menschen, aber auch in anderen Wirten, wie beispielsweise bei Vögeln und Schweinen erfolgen. Die so verursachten größeren, als Antigenshift bezeichnete Veränderungen in den viralen Oberflächenantigenen werden allein bei den Influenza-A-Viren beobachtet (Shiftvarianten), allerdings kommen sie nur selten vor. Derartige Veränderungen können dann der Ursprung von Pandemien sein, von denen es im 20. Jahrhundert die von 1918 bis 1919 mit dem Subtyp H1N1, 1957 mit H2N2, 1968 mit H3N2 und die von 1977 mit dem Wiederauftauchen von H1N1 gab.

Je nach Temperatur ist die Umweltstabilität (synonym Tenazität) der Influenzaviren sehr unterschiedlich. Bei einer normalen sommerlichen Tagestemperatur von etwa 20 °C können an Oberflächen angetrocknete Viren in der Regel zwei bis acht Stunden überdauern. Bei einer Temperatur von 0 °C mehr als 30 Tage und im Eis sind sie nahezu unbegrenzt überdauerungsfähig. Bei 22 °C überstehen sie sowohl in Exkrementen wie auch in Geweben verstorbener Tiere und in Wasser mindestens vier Tage. Die Lipidhülle des Influenza-Virus verändert sich bei tieferen Temperaturen, wodurch das Virus stabilisiert wird und länger pathogen bleibt.[78] Oberhalb von 22 °C verringert sich allerdings die Umweltstabilität der Influenzaviren sehr deutlich. Bei 56 °C werden sie innerhalb von 3 Stunden und bei 60 °C innerhalb von 30 Minuten inaktiviert.[79] Ab 70 °C verliert das Virus endgültig seine Infektiosität.

Als behülltes Virus ist das Influenza-A-Virus empfindlich gegenüber Detergentien[80][81] und organischen Lösemitteln wie Alkoholen (z. B. Ethanol, Isopropanol).[80][81] Die metastabile Fusionsdomäne des Hämagglutinins kann durch Säuren irreversibel ausgelöst werden.[82] Darüber hinaus kann auch eine chemische oder physikalische Denaturierung zu einem Funktionsverlust der viralen Proteine führen.[83] Durch die Vielzahl an effektiven Desinfektionsmechanismen sind Influenzaviren relativ instabil im Vergleich zu anderen Viren (z. B. dem Poliovirus oder dem Hepatitis-B-Virus).

Beim Menschen existieren die Influenzaviren und die durch sie ausgelösten Erkrankungen weltweit, allerdings kommen im Gegensatz zu den anderen Virustypen die Influenza-C-Viren nur gelegentlich vor. Während sich die Infektionen in gemäßigten Klimazonen mit zwei Hauptwellen im Oktober/November und im Februar/März manifestieren, ist die Infektionshäufigkeit in tropischen Gefilden konstant mit einem oder zwei Höhepunkten in der Regenzeit.

In Deutschland ist nur der direkte Nachweis von Influenzaviren namentlich meldepflichtig nach des Infektionsschutzgesetzes, soweit der Nachweis auf eine akute Infektion hinweist.

In der Schweiz ist ein positiver laboranalytische Befund zu Influenzaviren (saisonale, nicht-pandemische Typen und Subtypen) meldepflichtig und zwar nach dem Epidemiengesetz (EpG) in Verbindung mit der Epidemienverordnung und der Verordnung des EDI über die Meldung von Beobachtungen übertragbarer Krankheiten des Menschen. Zu einem Influenza-A-Virus des Typs HxNy (neuer Subtyp mit pandemischem Potenzial) ist sowohl ein positiver als auch ein negativer laboranalytischer Befund nach den genannten Normen meldepflichtig.

Die Gattungen Alpha-, Beta-, Gamma- und Deltainfluenzavirus aus der Familie Orthomyxoviridae sind behüllte Viren mit einer einzelsträngigen, segmentierten RNA von negativer Polarität als Genom. Unter den Gattungen finden sich auch die Erreger der Influenza oder „echten“ Grippe. Zu medizinischen Aspekten der Influenzaviren und Grippe-Erkrankung siehe Influenza. Gemäß International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV, Stand: November 2018) haben alle vier Gattungen jeweils nur eine Spezies, und zwar der Reihe nach Influenza A-Virus (FLUAV) bis Influenza D-Virus (FLUDV).

Influenza A virus යනු පක්ෂීන් සහ සමහර ක්ෂීර්පායීන් හට ඉන්ෆ්ලුවෙන්සාව ඇති කරන වෛරසයයි.[1]

Types Vaccines Treatment Pandemics Outbreaks

Types Vaccines Treatment Pandemics Outbreaks

Το ακρωνύμιο HχNψ (π.χ. H1N1, H5N1) έχει καθιερωθεί διεθνώς από τον Παγκόσμιο Οργανισμό Υγείας για το χαρακτηρισμό και διαφοροποίηση των διαφόρων στελεχών του ιού της γρίπης τύπου Α (Influenza virus type A) [1].

Τα γράμματα "H" και "N" υποδηλώνουν δύο γλυκοπρωτεΐνες που βρίσκονται στην επιφάνεια του ιού. Ειδικότερα, το "H" αντισtοιχεί στη γλυκοπρωτεΐνη αιμαγλουτινίνη (Hemagglutinin), ενώ το "N" στη γλυκοπρωτεΐνη νευραμινιδάση (Neuraminidase). Οι αριθμοί χ και ψ υποδηλώνουν τον (υπο-)τύπο αυτών των πρωτεϊνών, π.χ. H1N1 είναι το στέλεχος του ιού της γρίπης Α που έχει στην επιφάνειά του την αιμαγλουτινίνη τύπου 1 και την νευραμινιδάση τύπου 1.

Μέχρι στιγμής έχουν βρεθεί και μελετηθεί 16 διαφορετικοί τύποι αιμαγλουτινίνης (H1-H16) και 9 νευραμινιδάσης (N1-N9) [1] [2] [3], εκ των οποίων οι H1-H3 και N1-N2 συναντώνται συχνότερα στα στελέχη του ιού που προσβάλουν ανθρώπους [4].

Η αιμαγλουτινίνη και η νευραμινιδάση είναι απολύτως απαραίτητες για την μολυσματικότητα και μεταδοτικότητα του ιού. Η αιμαγλουτινίνη εξηπηρετεί δυο λειτουργίες [5].

H νευραμινιδάση είναι ένα ένζυμο που είναι απαραίτητο για την απελευθέρωση του ιού από το κύτταρο ξενιστή [6] [7].

Αυτές οι γλυκοπρωτεΐνες έχουν ισχυρές αντιγονικές ιδιότητες και προκαλούν την παραγωγή αντισωμάτων. Αντισώματα εναντίον της αιμαγλουτινίνης προσφέρουν ανοσία εξουδετερώνοντας τον ιό [8] [9], ενώ εκείνα εναντίον της νευραμινιδάσης περιορίζουν την μετάδοση του ιού από το ένα κύτταρο στο άλλο [10] [11].

Το ακρωνύμιο HχNψ (π.χ. H1N1, H5N1) έχει καθιερωθεί διεθνώς από τον Παγκόσμιο Οργανισμό Υγείας για το χαρακτηρισμό και διαφοροποίηση των διαφόρων στελεχών του ιού της γρίπης τύπου Α (Influenza virus type A) .

इन्फ्लुएन्जा ए वाइरस एक विषाणु है।

H1N1 (एच१इन१) इसी वायरस से निकलने वाली बीमारी है। इस विषाणु का नय़ुकलिक एसिड D.N.A य़ा R.N.A का बना हाेता है और बाहरी सतह पौ्टीन की बनी हाेती है

Influenza A virus (IAV) is a pathogen that causes the flu in birds and some mammals, including humans. It is an RNA virus whose subtypes have been isolated from wild birds. Occasionally, it is transmitted from wild to domestic birds, and this may cause severe disease, outbreaks, or human influenza pandemics.[1][2][3]

Each virus subtype has mutated into a variety of strains with differing pathogenic profiles; some may cause disease only in one species but others to multiple ones.

A filtered and purified influenza A vaccine for humans has been developed and many countries have stockpiled it to allow a quick administration to the population in the event of an avian influenza pandemic. In 2011, researchers reported the discovery of an antibody effective against all types of the influenza A virus.[4]

Influenza A virus is the only species of the genus Alphainfluenzavirus of the virus family Orthomyxoviridae.[5] It is an RNA virus categorized into subtypes based on the type of two proteins on the surface of the viral envelope:

The hemagglutinin is central to the virus's recognizing and binding to target cells, and also to its then infecting the cell with its RNA. The neuraminidase, on the other hand, is critical for the subsequent release of the daughter virus particles created within the infected cell so they can spread to other cells.

Different influenza viruses encode for different hemagglutinin and neuraminidase proteins. For example, the H5N1 virus designates an influenza A subtype that has a type 5 hemagglutinin (H) protein and a type 1 neuraminidase (N) protein. There are 18 known types of hemagglutinin and 11 known types of neuraminidase, so, in theory, 198 different combinations of these proteins are possible.[6][7]

Some variants are identified and named according to the isolate they resemble, thus are presumed to share lineage (example Fujian flu virus-like); according to their typical host (example human flu virus); according to their subtype (example H3N2); and according to their deadliness (example LP, low pathogenic). So a flu from a virus similar to the isolate A/Fujian/411/2002(H3N2) is called Fujian flu, human flu, and H3N2 flu.

Variants are sometimes named according to the species (host) in which the strain is endemic or to which it is adapted. The main variants named using this convention are:

Variants have also sometimes been named according to their deadliness in poultry, especially chickens:

Most known strains are extinct strains. For example, the annual flu subtype H3N2 no longer contains the strain that caused the Hong Kong flu.

The annual flu (also called "seasonal flu" or "human flu") in the US "results in approximately 36,000 deaths and more than 200,000 hospitalizations each year. In addition to this human toll, influenza is annually responsible for a total cost of over $10 billion in the U.S."[8] Globally the toll of influenza virus is estimated at 290,000–645,000 deaths annually, exceeding previous estimates.[9]

The annually updated, trivalent influenza vaccine consists of hemagglutinin (HA) surface glycoprotein components from influenza H3N2, H1N1, and B influenza viruses.[10]

Measured resistance to the standard antiviral drugs amantadine and rimantadine in H3N2 has increased from 1% in 1994 to 12% in 2003 to 91% in 2005.

"Contemporary human H3N2 influenza viruses are now endemic in pigs in southern China and can reassort with avian H5N1 viruses in this intermediate host."[11]

FI6, an antibody that targets the hemagglutinin protein, was discovered in 2011. FI6 is the only known antibody effective against all 16 subtypes of the influenza A virus.[12][13][14]

Influenza A viruses are negative-sense, single-stranded, segmented RNA virus. The several subtypes are labeled according to an H number (for the type of hemagglutinin) and an N number (for the type of neuraminidase). There are 18 different known H antigens (H1 to H18) and 11 different known N antigens (N1 to N11).[6][7] H17N10 was isolated from fruit bats in 2012.[15][16] H18N11 was discovered in a Peruvian bat in 2013.[7]

Influenza type A viruses are very similar in structure to influenza viruses types B, C, and D.[19] The virus particle (also called the virion) is 80–120 nanometers in diameter such that the smallest virions adopt an elliptical shape.[20][18] The length of each particle varies considerably, owing to the fact that influenza is pleomorphic, and can be in excess of many tens of micrometers, producing filamentous virions.[21] Confusion about the nature of influenza virus pleomorphy stems from the observation that lab adapted strains typically lose the ability to form filaments[22] and that these lab adapted strains were the first to be visualized by electron microscopy.[23] Despite these varied shapes, the virions of all influenza type A viruses are similar in composition. They are all made up of a viral envelope containing two main types of proteins, wrapped around a central core.[24]

The two large proteins found on the outside of viral particles are hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA). HA is a protein that mediates binding of the virion to target cells and entry of the viral genome into the target cell. NA is involved in release from the abundant non-productive attachment sites present in mucus[25] as well as the release of progeny virions from infected cells.[26] These proteins are usually the targets for antiviral drugs.[27] Furthermore, they are also the antigen proteins to which a host's antibodies can bind and trigger an immune response. Influenza type A viruses are categorized into subtypes based on the type of these two proteins on the surface of the viral envelope. There are 16 subtypes of HA and 9 subtypes of NA known, but only H 1, 2 and 3, and N 1 and 2 are commonly found in humans.[28]

The central core of a virion contains the viral genome and other viral proteins that package and protect the genetic material. Unlike the genomes of most organisms (including humans, animals, plants, and bacteria) which are made up of double-stranded DNA, many viral genomes are made up of a different, single-stranded nucleic acid called RNA. Unusually for a virus, though, the influenza type A virus genome is not a single piece of RNA; instead, it consists of segmented pieces of negative-sense RNA, each piece containing either one or two genes which code for a gene product (protein).[24] The term negative-sense RNA just implies that the RNA genome cannot be translated into protein directly; it must first be transcribed to positive-sense RNA before it can be translated into protein products. The segmented nature of the genome allows for the exchange of entire genes between different viral strains.[24]

The entire Influenza A virus genome is 13,588 bases long and is contained on eight RNA segments that code for at least 10 but up to 14 proteins, depending on the strain. The relevance or presence of alternate gene products can vary:[29]

The RNA segments of the viral genome have complementary base sequences at the terminal ends, allowing them to bond to each other with hydrogen bonds.[26] Transcription of the viral (-) sense genome (vRNA) can only proceed after the PB2 protein binds to host capped RNAs, allowing for the PA subunit to cleave several nucleotides after the cap. This host-derived cap and accompanied nucleotides serve as the primer for viral transcription initiation. Transcription proceeds along the vRNA until a stretch of several uracil bases is reached, initiating a 'stuttering' whereby the nascent viral mRNA is poly-adenylated, producing a mature transcript for nuclear export and translation by host machinery.[31]

The RNA synthesis takes place in the cell nucleus, while the synthesis of proteins takes place in the cytoplasm. Once the viral proteins are assembled into virions, the assembled virions leave the nucleus and migrate towards the cell membrane.[32] The host cell membrane has patches of viral transmembrane proteins (HA, NA, and M2) and an underlying layer of the M1 protein which assist the assembled virions to budding through the membrane, releasing finished enveloped viruses into the extracellular fluid.[32]

The subtypes of influenza A virus are estimated to have diverged 2,000 years ago. Influenza viruses A and B are estimated to have diverged from a single ancestor around 4,000 years ago, while the ancestor of influenza viruses A and B and the ancestor of influenza virus C are estimated to have diverged from a common ancestor around 8,000 years ago.[33]

Influenza virus is able to undergo multiplicity reactivation after inactivation by UV radiation,[34][35] or by ionizing radiation.[36] If any of the eight RNA strands that make up the genome contains damage that prevents replication or expression of an essential gene, the virus is not viable when it alone infects a cell (a single infection). However, when two or more damaged viruses infect the same cell (multiple infection), viable progeny viruses can be produced provided each of the eight genomic segments is present in at least one undamaged copy. That is, multiplicity reactivation can occur.

Upon infection, influenza virus induces a host response involving increased production of reactive oxygen species, and this can damage the virus genome.[37] If, under natural conditions, virus survival is ordinarily vulnerable to the challenge of oxidative damage, then multiplicity reactivation is likely selectively advantageous as a kind of genomic repair process. It has been suggested that multiplicity reactivation involving segmented RNA genomes may be similar to the earliest evolved form of sexual interaction in the RNA world that likely preceded the DNA world.[38]

"Human influenza virus" usually refers to those subtypes that spread widely among humans. H1N1, H1N2, and H3N2 are the only known influenza A virus subtypes currently circulating among humans.[39]

Genetic factors in distinguishing between "human flu viruses" and "avian influenza viruses" include:

Human flu symptoms usually include fever, cough, sore throat, muscle aches, conjunctivitis and, in severe cases, breathing problems and pneumonia that may be fatal. The severity of the infection will depend in large part on the state of the infected person's immune system and if the victim has been exposed to the strain before, and is therefore partially immune. Follow-up studies on the impact of statins on influenza virus replication show that pre-treatment of cells with atorvastatin suppresses virus growth in culture.[40]

Highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza in a human is far worse, killing 50% of humans who catch it. In one case, a boy with H5N1 experienced diarrhea followed rapidly by a coma without developing respiratory or flu-like symptoms.[41]

The influenza A virus subtypes that have been confirmed in humans, ordered by the number of known human pandemic deaths, are:

H10N3

In May 2021, in Zhenjiang, China H10N3 was reported for the first time in humans. One person was infected.[63]

According to Jeffery Taubenberger:

Researchers from the National Institutes of Health used data from the Influenza Genome Sequencing Project and concluded that during the ten-year period examined, most of the time the hemagglutinin gene in H3N2 showed no significant excess of mutations in the antigenic regions while an increasing variety of strains accumulated. This resulted in one of the variants eventually achieving higher fitness, becoming dominant, and in a brief interval of rapid evolution, rapidly sweeping through the population and eliminating most other variants.[65]

In the short-term evolution of influenza A virus, a 2006 study found that stochastic, or random, processes are key factors.[66] Influenza A virus HA antigenic evolution appears to be characterized more by punctuated, sporadic jumps as opposed to a constant rate of antigenic change.[67] Using phylogenetic analysis of 413 complete genomes of human influenza A viruses that were collected throughout the state of New York, the authors of Nelson et al. 2006 were able to show that genetic diversity, and not antigenic drift, shaped the short-term evolution of influenza A via random migration and reassortment. The evolution of these viruses is dominated more by the random importation of genetically different viral strains from other geographic locations and less by natural selection. Within a given season, adaptive evolution is infrequent and had an overall weak effect as evidenced from the data gathered from the 413 genomes. Phylogenetic analysis revealed the different strains were derived from newly imported genetic material as opposed to isolates that had been circulating in New York in previous seasons. Therefore, the gene flow in and out of this population, and not natural selection, was more important in the short term.

Fowl act as natural asymptomatic carriers of influenza A viruses. Prior to the current H5N1 epizootic, strains of influenza A virus had been demonstrated to be transmitted from wildfowl to only birds, pigs, horses, seals, whales and humans; and only between humans and pigs and between humans and domestic fowl; and not other pathways such as domestic fowl to horse.[68]

Wild aquatic birds are the natural hosts for a large variety of influenza A viruses. Occasionally, viruses are transmitted from these birds to other species and may then cause devastating outbreaks in domestic poultry or give rise to human influenza pandemics.[2][3]

H5N1 has been shown to be transmitted to tigers, leopards, and domestic cats that were fed uncooked domestic fowl (chickens) with the virus. H3N8 viruses from horses have crossed over and caused outbreaks in dogs. Laboratory mice have been infected successfully with a variety of avian flu genotypes.[69]

Influenza A viruses spread in the air and in manure, and survives longer in cold weather. They can also be transmitted by contaminated feed, water, equipment, and clothing; however, there is no evidence the virus can survive in well-cooked meat. Symptoms in animals vary, but virulent strains can cause death within a few days. Avian influenza viruses that the World Organisation for Animal Health and others test for to control poultry disease include H5N1, H7N2, H1N7, H7N3, H13N6, H5N9, H11N6, H3N8, H9N2, H5N2, H4N8, H10N7, H2N2, H8N4, H14N5, H6N5, and H12N5.

*Outbreaks with significant spread to numerous farms, resulting in great economic losses. Most other outbreaks involved little or no spread from the initially infected farms.

More than 400 harbor seal deaths were recorded in New England between December 1979 and October 1980, from acute pneumonia caused by the influenza virus, A/Seal/Mass/1/180 (H7N7).[71]

Influenza A virus has the following subtypes:

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Influenza A virus (IAV) is a pathogen that causes the flu in birds and some mammals, including humans. It is an RNA virus whose subtypes have been isolated from wild birds. Occasionally, it is transmitted from wild to domestic birds, and this may cause severe disease, outbreaks, or human influenza pandemics.

Each virus subtype has mutated into a variety of strains with differing pathogenic profiles; some may cause disease only in one species but others to multiple ones.

A filtered and purified influenza A vaccine for humans has been developed and many countries have stockpiled it to allow a quick administration to the population in the event of an avian influenza pandemic. In 2011, researchers reported the discovery of an antibody effective against all types of the influenza A virus.

Influenzavirus A o Alphainfluenzavirus [n. 1] es un género de virus de la familia Orthomyxoviridae.[3][1] Cuando se produce un cambio antígeno es causante de la gripe episódica en humanos y que se produce en ciclos de entre 10 y 15 años. En los humanos se desarrolla generalmente una gripe más virulenta que la producida por las variaciones antigénicas menores, que también ocurren en el Influenza B (en ocasiones ocurren simultáneamente) y condicionan las gripes estacionales, que suceden casi todos los años.

Incluye solo a una especie, el virus Influenza A, que es causante de gripe en aves así como también en mamíferos. Se supone que el hospedador natural son las aves, pero puede infectar a varias especies de mamíferos, incluyendo a los humanos y porcinos. Todos los subtipos conocidos son endémicos en pájaros, la mayoría de los subtipos no causan endemias fuera de las aves, por lo que, básicamente, se la considera una gripe de aves.[4] Sin embargo, tras los contagios que han ocurrido de aves a humanos en los últimos años, sobre todo en países asiáticos, se realiza una estrecha vigilancia sobre los brotes de cepas más virulentas en las aves, el reservorio natural típico de este virus.

La Influenza ataca preferentemente el tracto respiratorio alto, la nariz y garganta, bronquios y raramente también los pulmones. La infección usualmente dura una semana Es caracterizada por un inicio súbito de fiebre alta, dolores musculares, dolor de cabeza, malestar general fuerte, tos no productiva, dolor de garganta y secreción nasal. La mayoría de las personas se recupera en una o dos semana sin requerir tratamiento alguno. En los extremos de la vida (bebés y ancianos) así como en personas que padecen enfermedades previas como: enfermedades respiratorias crónicas, diabetes mellitus, cáncer, enfermedades renales o cardiológicas, la Influenza se constituye en un serio riesgo para la vida. En estas personas la infección puede desarrollar complicaciones graves, empeorar las enfermedades de fondo llegando inclusive a la neumonía y la muerte.

La Influenza aparece rápidamente alrededor del mundo en epidemias estacionales, generando impacto económico en las poblaciones afectadas por los gastos que origina por concepto de atenciones, medicamentos, hospitalización y manejo de las complicaciones, así como por la pérdida de la capacidad laboral de las personas afectadas.

En las epidemias anuales de Influenza 5-15 % de la población es afectada con infecciones de tracto respiratorio superior. La hospitalización y muerte podrían ocurrir en grupos de elevado riesgo (ancianos y personas que padecen enfermedades crónicas). Se calcula como resultado de las epidemias anuales entre tres y cinco millones de casos más serios de la enfermedad, así como entre 250 000 y 500 000 muertes cada año alrededor del mundo.

La estructura física de todos los subtipos de virus influenza A es similar. Los viriones envueltos pueden ser de forma esférica o filamentosa. En las muestras clínicas, las cuales han sobrellevado un limitado movimiento entre tejidos o huevos de cultivo, tienden a ser partículas más filamentosas que esféricas, mientras que las cepas pasadas por el laboratorio son viriones generalmente esféricos.[5]

El genoma del Virus influenza A está contenido en ocho cadenas simples (no apareadas) que codifican diez proteínas: HA, NA, NP, M1, M2, NS1, NS2, PA, PB1 y PB2. La naturaleza segmentada del genoma permite el intercambio del repertorio genético entero entre las diferentes cepas virales durante la cohabitación celular, por eso se las denomina recombinantes. Los ocho segmentos o cadenas de ARN son:

Existe una animación sobre la replicación del virus dentro de las células en el Observatorio para la Salud de la Universidad de Guadalajara. [2]

Las pandemias por este género de virus se han producido con una periodicidad aproximada de diez-quince años desde la que se produjo en 1918. Son más graves y extensos debido a la tendencia de los antígenos hemaglutinina y neuraminidasa a tener una variación antigénica periódica. Cuando se produce en la Influenza A una desviación antigénica menor, que también se da en los Influenza B y en mucha menor medida en los Influenza C, se producen las epidemias estacionales.[7] Estas epidemias comienzan de forma brusca, alcanzan su máximo en dos o tres semanas y ceden también en unos meses. Suelen ocurrir en los meses de invierno en ambos hemisferios, siendo muy raro encontrar un virus influenza A fuera de las epidemias. Se desconoce si estos virus en las épocas interepidémicas se mantienen en reservorios animales o si el reservorio es humano con transmisión interepidémica de bajo nivel por transmisión persona-persona. En la época contemporánea los transportes rápidos contribuyen a la expansión geográfica del virus. La tasa de personas con enfermedad son muy variables, pero de forma general oscilan entre 10 y 20 % de la población general.[8]

Las cepas H1N1 que han circulado en los últimos años se considera que han sido menos virulentas intrínsecamente, causando una enfermedad menos grave, incluso en sujetos sin inmunidad al virus, por lo que existen otros factores no precisados en la epidemiología de la gripe.[8]

Seguidamente se describen las pandemias, epidemias o brotes conocidos de gripe por virus influenza A tras un cambio antigénico con aparición de subtipos antigénicos:

Los pueblos indígenas son especialmente vulnerables a la gripe A. Si viven aislados o no contactados carecen de inmunidad contra esta enfermedad. En este caso cualquier contacto puede ser mortal para ellos.[13]

Los pueblos indígenas contactados también se ven muy afectados por la gripe A, porque muchas veces viven en situaciones de pobreza con graves problemas de salud por falta de asistencia sanitaria. Por eso una pandemia puede tener consecuencias devastadoras para ellos.

La vacunación es la medida principal para prevenir la Influenza y reducir el impacto de las epidemias. Varios tipos de vacunas de Influenza han sido utilizados durante más de 60 años. Son seguras y efectivas en la prevención de brotes de Influenza.[7]

Es recomendable que las personas mayores y aquellas a quiénes se les considere de “alto riesgo” sean vacunadas. La vacunación en el adulto mayor ha contribuido a reducir la morbilidad relacionada con Influenza en 60 % y la mortalidad en 70-80 %. Inclusive en adultos saludables la vacuna ha demostrado ser muy efectiva (70-90 %) en términos de reducción de la morbilidad, demostrando ser una estrategia coste efectiva. En este grupo etario. La efectividad de la vacuna dependerá primariamente de la edad y del estado inmunológico de la persona vacunada, así como del grado de similitud entre los virus circulantes y los de la vacuna. En consecuencia la vacunación puede reducir los gastos de salud generados por la enfermedad y la pérdida de productividad asociada a Influenza.

Los cambios genéticos continuos en los virus Influenza, determinan que la composición vírica de la vacuna deba ser ajustada anualmente, para incluir aquellos de más reciente circulación como: Influenza A(H3N2), A(H1N1) e Influenza B.

Para la mayoría de las personas la influenza es una enfermedad del tracto respiratorio superior que dura varios días y que sólo requiere tratamiento sintomático. En pocos días el virus es eliminado del cuerpo. Antibióticos, tales como penicilina están diseñados para destruir bacterias no pueden atacar a los virus. Por tanto los antibióticos no juegan un rol en el tratamiento de la Influenza, aunque ellos son usados para tratar complicaciones.

Drogas antivirales para Influenza son importantes coadyuvantes de la vacunación para el tratamiento y prevención de la Influenza. Sin embargo, no son substitutos de la vacunación. Durante muchos años, cuatro drogas antivirales que actúan previniendo la replicación del virus han sido utilizadas. Ellas difieren en términos farmacocinéticos, efectos colaterales, vías de administración, grupos de edad objetivo, dosis y costes.

Los antivirales deberían usarse en aquellos pacientes con alguna condición de inmunosupresión. Cuando son tomados antes de la infección o durante los estadios tempranos de la enfermedad (dentro de los dos primeros), los antivirales pueden ayudar a prevenirla y si la enfermedad ya se ha iniciado su administración temprana puede reducir la duración de los síntomas de uno a dos días.

Durante muchos años, la Amantadina y la Rimantadina fueron las únicas drogas antivirales. Sin embargo, pese a su relativo moderado coste, estas drogas son efectivas sólo contra la Influenza tipo A y pueden ser asociadas con efectos adversos graves (incluidos delirios y ataques que ocurren mayormente en personas ancianas o con dosis altas). Cuando son usadas para profilaxis de Pandemias de Influenza a bajas dosis, tales eventos adversos son poco probables. En consecuencia el virus tiende a desarrollar resistencia a estas drogas.

Una nueva clase de antivirales ha sido desarrollada: Inhibidores de Neuraminidasa. Drogas tales como Zanamivir, y Oseltamivir tienen pocos efectos adversos (aunque Zanamivir puede exacerbar el asma u otras enfermedades crónicas) y el virus infrecuentemente desarrolla resistencia. Sin embargo, estas drogas son caras y no disponibles para su uso en muchos países.

En casos de Influenza grave, la admisión hospitalaria a la unidad de cuidados intensivos, la antibióticoterapia para la prevención de infecciones secundarias y el soporte respiratorio pueden ser requeridos.

Influenzavirus A o Alphainfluenzavirus es un género de virus de la familia Orthomyxoviridae. Cuando se produce un cambio antígeno es causante de la gripe episódica en humanos y que se produce en ciclos de entre 10 y 15 años. En los humanos se desarrolla generalmente una gripe más virulenta que la producida por las variaciones antigénicas menores, que también ocurren en el Influenza B (en ocasiones ocurren simultáneamente) y condicionan las gripes estacionales, que suceden casi todos los años.

Incluye solo a una especie, el virus Influenza A, que es causante de gripe en aves así como también en mamíferos. Se supone que el hospedador natural son las aves, pero puede infectar a varias especies de mamíferos, incluyendo a los humanos y porcinos. Todos los subtipos conocidos son endémicos en pájaros, la mayoría de los subtipos no causan endemias fuera de las aves, por lo que, básicamente, se la considera una gripe de aves. Sin embargo, tras los contagios que han ocurrido de aves a humanos en los últimos años, sobre todo en países asiáticos, se realiza una estrecha vigilancia sobre los brotes de cepas más virulentas en las aves, el reservorio natural típico de este virus.

A-tüüpi gripiviirus ehk A-gripiviirus on viiruse liik.

Genoom koosneb 8 helikaalsest segmendist.

A-gripiviirus klassifitseeritakse alatüüpideks. Alatüüpide klassifikatsioon põhineb nii pinnaglükoproteiinide hemaglutiniini (HA) kui ka neuraminidaasi (NA) antigeensetel omadustel.[1]

A-gripiviirustel teatakse 18 erinevat hemaglutiniinil ja 11 erinevat neuraminidaasil põhinevat alatüüpi.

A-gripiviiruse alatüübid põhjustavad osadel imetajatel (sh inimestel) mitmesuguseid A-gripi vorme.

Influenssa A -virus on vaipallinen, negatiivisäikeinen RNA-virus. Taksonomisesti kyseessä on Influenzavirus A -suku. Virus on monien eläinten taudinaiheuttaja.

Influenssa A -viruksella tapahtuu jatkuvasti paljon antigeenistä muuntumista. Sen RNA-perimä koostuu kahdeksasta erillisestä segmentistä. [1]

Virus infektoi hengitysteiden soluja. Sen aiheuttamaa tautia kutsutaan influenssaksi, [1] tarkemmin A-influenssaksi. Se leviää laajoina epidemioina, jopa pandemioina. [2]

Vuonna 1918 influenssa A:n alatyyppi H1N1 aiheutti ns. Espanjantaudin, johon kuoli kymmeniä miljoonia ihmisiä.

Influenssa A -virion on yleensä muodoltaan pyöreä ja kooltaan noin 100 nanometriä. Virioniin kuuluu lipidivaippa, joka on peräisin viruksen synnyinsolun solukalvosta. Viruksella on yhdeksän rakenneproteiinia: [1]

Lisäksi sillä on NS1 eli nonstrukturaalinen (ei-rakenteellinen) proteiini, joka säätelee geeniekspressiota, sekä NS2.[1]

Viruksen hemagglutiniini (HA)- ja neuraminidaasi (NA)-proteiinien antigeeninen variaatio on pohjana alatyyppeihin jaolle. Vuonna 2010 tunnettiin 16 hemagglutiniinin alatyyppiä (H1–H16) ja yhdeksän neuraminidaasin alatyyppiä (N1–N9).[3] Uusi HA–NA-yhdistelmä eli viruksen alatyyppi voi syntyä, kun kaksi erilaista influenssa A -virusta on infektoinut saman solun, niin että osa virusten jälkeläisistä voi rakentua eri alkuperää olevista RNA-segmenteistä. [1]

HA- ja NA-geeneille voi viruksen replikoituessa tapahtua pistemutaatioita, jotka muuttavat proteiinien aminohappojärjestystä epitoopin kohdalla. Tällaiset muutokset voivat johtaa siihen, että isännän immuunijärjestelmä ei tunnista viruksen muuntunutta jälkeläistä. Yksittäiset pistemutaatiot viruksessa eivät tarkoita kokonaan uuden alatyypin syntymistä. [1]

Eristetty influenssavirus yksilöidään nimeämällä se muodossa ”tyyppi/taudinkantaja jos ei ihminen/maantieteellinen alkuperä/kannan numero/vuosi(HA- ja NA-alatyyppi jos influenssa A)”.[1] Esimerkiksi vuoden 2009 sikainfluenssapandemian aiheuttajavirus oli A/California/04/09(H1N1).

Influenssa A -virus on vaipallinen, negatiivisäikeinen RNA-virus. Taksonomisesti kyseessä on Influenzavirus A -suku. Virus on monien eläinten taudinaiheuttaja.

Influenssa A -viruksella tapahtuu jatkuvasti paljon antigeenistä muuntumista. Sen RNA-perimä koostuu kahdeksasta erillisestä segmentistä.

Virus infektoi hengitysteiden soluja. Sen aiheuttamaa tautia kutsutaan influenssaksi, tarkemmin A-influenssaksi. Se leviää laajoina epidemioina, jopa pandemioina.

Vuonna 1918 influenssa A:n alatyyppi H1N1 aiheutti ns. Espanjantaudin, johon kuoli kymmeniä miljoonia ihmisiä.

Le virus de la grippe A est un virus à ARN monocaténaire de polarité négative à génome segmenté (8 segments) qui appartient au genre Alphainfluenzavirus de la famille des Orthomyxoviridae. Il présente un grand nombre de sous-types identifiés par deux antigènes présents à sa surface, l'hémagglutinine et la neuraminidase, selon une notation indiquant les types d'antigènes du virus : par exemple, le sous-type H5N1 fait référence à la présence d'hémagglutinine de type 5 et de neuraminidase de type 1. On connaît 18 antigènes H, notés de H1 à H18, et 11 antigènes N, notés de N1 à N11[2],[3]. Le sous-type H17N10 a été observé chez des roussettes en 2012[4], tandis que le sous-type H18N11 a été observé chez une chauve-souris du Pérou en 2013[3].

Tous ces sous-types ont été isolés chez des oiseaux sauvages, chez lesquels il est susceptible de provoquer la grippe aviaire, bien que cette maladie soit en réalité assez rare. Certains de ces virus peuvent être très pathogènes et provoquer une maladie grave chez les volailles et, plus rarement, chez l'homme[5]. Il peut arriver que le virus soit transmis aux volailles par des oiseaux sauvages et, de là, contamine des humains, provoquant des épidémies, voire des pandémies[6],[7].

Comme tous les virus à ARN, les virus de la grippe A tendent à muter, de sorte que chaque sous-type s'est diversifié en souches plus ou moins pathogènes, dont la pathogénicité varie fortement d'une espèce animale à une autre.

Les virus de la grippe A sont des virus à ARN classés en sous-types en fonction du type de deux protéines de leur enveloppe virale :

L'hémagglutinine joue un rôle central dans la reconnaissance et la liaison du virus aux cellules hôtes, ainsi que dans l'infection de la cellule par son ARN. La neuraminidase, en revanche, est essentielle à la libération subséquente des particules virales produites au sein de la cellule infectée pour contaminer d'autres cellules.

Différents virus de la grippe codent différentes protéines d'hémagglutinine et de neuraminidase. Ainsi, le sous-type H5N1 désigne un sous-type de virus de la grippe A dont l'enveloppe contient de l'hémagglutinine (H) de type 5 et de la neuraminidase (N) de type 1. Il existe 18 types d'hémagglutinine et 11 types de neuraminidase, de sorte qu'il existe théoriquement 198 combinaisons différentes de ces protéines[2],[3].

Certaines variantes peuvent être nommées en fonction de l'isolat dont elles peuvent être rapprochées et dont on présume qu'elles partagent la même lignée, comme les virus de type grippe de Fujian, en fonction de leur hôte, comme le virus de la grippe humaine, en fonction de leur sous-type, comme le virus H3N2, ou en fonction de leur pathogénicité, par exemple l'indication LP signifiant low pathogenicity (« faible pathogénicité »). Ainsi, une grippe provoquée par un virus semblable à l'isolat A/Fujian/411/2002(H3N2) peut être qualifiée aussi bien de grippe Fujian, de grippe humaine et de grippe H3N2.

Des variantes du virus de la grippe peuvent également être nommées en fonction de l'hôte chez lequel la souche est endémique ou auquel elle est adaptée. Ce sont notamment :

Les grippes aviaires sont parfois distinguées en fonction de leur pathogénicité pour les volailles, notamment chez les poulets :

Compte tenu de la rapidité de mutation des virus de la grippe, la plupart des souches répertoriées sont à présent éteintes. Par exemple, le sous-type H3N2 de grippe saisonnière ne contient plus la souche à l'origine de la grippe de Hong Kong.

Les virus de la grippe A (H1N1) se réfèrent au sous-type H1N1 des virus de la grippe A. Ils sont régulièrement responsables des cas de grippe saisonnière. Certaines souches de H1N1 sont endémiques aux humains, tandis que d'autres sont endémiques chez les oiseaux (grippe aviaire) et chez les porcs (la grippe porcine).

Des virus du sous-type H1N1 sont responsables des pandémies de grippe en 1918 et en 2009. Les symptômes sont similaires à ceux de la grippe saisonnière et peuvent inclure fièvre, éternuements, mal de gorge, toux, maux de tête et douleurs musculaires et articulaires.

Les virus Influenza A sous-type H1N2 sont des virus de la grippe de type A.

Les virus de la grippe A sous-type H2N2 sont des virus de la grippe (de type A, sous-type H2N2). La souche H2N2 serait responsable de l'épidémie de grippe en 1889 en Russie.

Des virus H2N2 ont muté en différentes souches, incluant la souche de la grippe asiatique entre 1956 et 1958, les H3N2, et d'autres souches se retrouvant dans les oiseaux.

Les virus de la grippe A sous-type H3N1 sont des virus de la grippe de type A.

Les virus de la grippe A sous-type H3N2 sont des virus de la grippe de type A.

La grippe de 1968 a été causée par un virus de sous-type H2N2 réassorti en sous-type H3N2.

Les virus de la grippe A de sous-type H5N1 sont des sous-types de virus grippal de type A. Certains sont hautement pathogènes. Ils peuvent être responsables de la grippe aviaire. La première apparition connue de ce type de grippe chez les humains a eu lieu à Hong Kong en 1997. L’infection des humains a coïncidé avec une épizootie de grippe aviaire, causée par le même agent infectieux, dans les élevages de poulets à Hong Kong.

Des variantes faiblement pathogènes du H5N1 ont également été repérées.

Ce sous-type a été signalé en avril 2014 chez des volailles en Chine mais a aussi été détecté en Asie du Sud-Est (Laos et Vietnam).

La première victime humaine signalée l'a été en Chine début 2014[8]. En Septembre 2014, la FAO la considère comme une nouvelle menace pour la santé animale[9]. Son statut en termes de risques écoépidémiolgiques est en discussion. Il serait au moins pour certains variants hautement pathogène selon l’OIE (exemple : 498 faisans de Colchide morts et 60 abattus sur un total de 558 faisans en aout 2014 au Vietnam)[10].

Les virus de la grippe A sous-type H5N8 sont des virus de la grippe de type A.

Les virus de la grippe A sous-type H5N9 sont des virus de la grippe de type A. Il a été montré en 2012, qu'un variant hautement pathogène de ce virus dérive d'un virus faiblement pathogène du H5N1 détecté dans certains élevages (A/turkey/Ontario/6213/1966 ; H5N1)[11].

Les virus de la grippe A de sous-type H7 sont des sous-types de virus grippal de type A. Ils affectent principalement les oiseaux mais des cas humains ont été repérés au Canada en 2004[12].

Reconnu en Chine le 31 mars 2013, selon les autorités officielles.

Le sous-type H10N7 est signalé pour la première fois chez l'homme en 2004, en Égypte[13]. Deux enfants d'un an tombent malades. Les deux résident à Ismaïlia, en Égypte, et le père de l'un d'eux est vendeur de volailles[14].

La première épizootie aux États-Unis d'Amérique survient dans deux élevages de dindes au Minnesota, en 1979. Un troisième élevage est affecté en 1980. Le spectre des symptômes va du très grave, avec un taux de mortalité atteignant 31 %, jusqu'au subclinique. Des virus au profil antigénique indistinguable de ceux des dindes infectées ont été isolés sur des canards colverts présents dans une mare adjacente à l'élevage des dindes[15].

Le sous-type H10N8 est encore mal connu. Le 17 décembre 2013, la Chine a confirmé qu'une patiente de 75 ans (morte d'une pneumonie sévère dans la province du Jiangxi) était le 1er cas connu d'infection humaine H10N8[16] ; deux mois plus tard dans la même province du Jiangxi (le 15 février 2014) trois autres cas humains de H10N8 étaient ont été confirmés (dont deux mortels)[16].

Un article de la revue Clinical Infectious Diseases a signalé que dans la province du Guangdong (Chine) des chiens errants dans des marchés de volaille ont pour la première fois montré des signes tangibles d'infections par le sous-type viral H10N8 alors qu'au même moment une épizootie due au H5N8 s'étend en Asie, laissant penser que l'organisme du chien pourrait être un lieu de réassortiment génétique pour plusieurs souches virales en circulation[16].

Le virus de la grippe A est un virus à ARN monocaténaire de polarité négative à génome segmenté (8 segments) qui appartient au genre Alphainfluenzavirus de la famille des Orthomyxoviridae. Il présente un grand nombre de sous-types identifiés par deux antigènes présents à sa surface, l'hémagglutinine et la neuraminidase, selon une notation indiquant les types d'antigènes du virus : par exemple, le sous-type H5N1 fait référence à la présence d'hémagglutinine de type 5 et de neuraminidase de type 1. On connaît 18 antigènes H, notés de H1 à H18, et 11 antigènes N, notés de N1 à N11,. Le sous-type H17N10 a été observé chez des roussettes en 2012, tandis que le sous-type H18N11 a été observé chez une chauve-souris du Pérou en 2013.

Tous ces sous-types ont été isolés chez des oiseaux sauvages, chez lesquels il est susceptible de provoquer la grippe aviaire, bien que cette maladie soit en réalité assez rare. Certains de ces virus peuvent être très pathogènes et provoquer une maladie grave chez les volailles et, plus rarement, chez l'homme. Il peut arriver que le virus soit transmis aux volailles par des oiseaux sauvages et, de là, contamine des humains, provoquant des épidémies, voire des pandémies,.

Comme tous les virus à ARN, les virus de la grippe A tendent à muter, de sorte que chaque sous-type s'est diversifié en souches plus ou moins pathogènes, dont la pathogénicité varie fortement d'une espèce animale à une autre.

Virus influenza A adalah spesies virus yang menyebabkan influenza pada burung dan beberapa mamalia, dan merupakan satu-satunya spesies pada genus Alphainfluenzavirus dari famili Orthomyxoviridae.[1] Beberapa isolat virus influenza A dapat menyebabkan penyakit yang berat, baik pada burung domestik (unggas) dan terkadang pada manusia.[2]

Virus influenza A tergolong virus RNA untai tunggal yang dibagi menjadi beberapa subtipe berdasarkan jenis protein hemaglutinin (disingkat H) dan neuraminidase (N) yang dimilikinya. Hingga saat ini telah diidentifikasi 18 jenis antigen H (H1 sampai H18) dan 11 jenis antigen N (N1 sampai 11).[3][4]

Virus influenza A adalah spesies virus yang menyebabkan influenza pada burung dan beberapa mamalia, dan merupakan satu-satunya spesies pada genus Alphainfluenzavirus dari famili Orthomyxoviridae. Beberapa isolat virus influenza A dapat menyebabkan penyakit yang berat, baik pada burung domestik (unggas) dan terkadang pada manusia.

Virus influenza A tergolong virus RNA untai tunggal yang dibagi menjadi beberapa subtipe berdasarkan jenis protein hemaglutinin (disingkat H) dan neuraminidase (N) yang dimilikinya. Hingga saat ini telah diidentifikasi 18 jenis antigen H (H1 sampai H18) dan 11 jenis antigen N (N1 sampai 11).

L'Influenzavirus A o virus dell'influenza A è una specie di virus appartenente alla famiglia degli Orthomyxoviridae, in grado di infettare alcune specie di uccelli e mammiferi. È l'unica specie appartenente al genere Alphainfluenzavirus.[1]

I sottotipi appartenenti all'influenzavirus A sono stati identificati in molti tipi di uccelli selvatici, benché lo sviluppo dell'influenza sia molto raro in questi animali. L'influenzavirus A è in grado di sostenere gravi entità sindromiche nel pollame e, molto raramente, negli esseri umani[2] Occasionalmente, il virus può trasmettersi da uccelli d'acqua al pollame domestico, con rischio di infezione e malattia per l'essere umano. In tali condizioni, è possibile lo sviluppo di epidemie e pandemie.[3][4]

Il virus dell'influenza A è un virus a RNA segmentato, a singolo filamento e a polarità negativa (per essere tradotto in proteina è necessaria una RNA polimerasi RNA dipendente che crei il filamento a polarità positiva). Esistono diversi sottotipi, in accordo con le possibili combinazioni tra le diverse forme di emoagglutinina (H) e di neuraminidasi (N). Esistono 18 differenti tipi di emoagglutinina (da H1 a H18) e 11 differenti tipi di neuroaminidasi (da N1 a N11)[5]. Il tipo H16 è il più nuovo ed è stato isolato nel gabbiano dalla testa nera in Svezia e Paesi Bassi nel 1999 e riportato nella letteratura nel 2005.[6] I diversi sottotipi di virus hanno un diverso profilo patogenetico e clinico. Inoltre i diversi sottotipi virali possiedono capacità diverse di contagiare specie animali differenti. La struttura di tutti gli 'Influenzavirus A è simile, con caratteristica forma sferica o filamentosa.[7]