en

names in breadcrumbs

Les balenes franques (Eubalaena) són un gènere de balenes que comprèn tres espècies: la balena franca comuna (E. glacialis), E. japonica i E. australis. Juntament amb la balena de Groenlàndia (Balaena mysticetus) són les úniques espècies vivents de la família dels balènids. Al llarg dels últims dos segles la taxonomia d'aquestes espècies ha estat en flux constant i les balenes franques sovint han estat considerades com pertanyents al gènere Balaena, motiu pel qual la balena de Groenlàndia també rep el nom de balena franca àrtica. La balena franca pigmea (Capera marginata), una balena molt més petita de l'hemisferi sud, també estava inclosa a la família dels balènids, però recentment s'ha descobert que és prou diferent com per justificar una família pròpia, la dels neobalènids.

Les tres espècies són migratòries i es desplacen estacionalment per alimentar-se o donar a llum. Les aigües càlides de l'equador formen una barrera que isola les espècies d'un i altre hemisferi. Al nord, les balenes franques tendeixen a evitar les aigües obertes i a mantenir-se properes a les penínsules i badies i a les plataformes continentals, ja que aquestes zones encobreixen millor i hi ha menjar abundant. Al sud, les balenes franques s'alimenten lluny de la costa a l'estiu, però una gran majoria d'elles també opta per arrecerar-se en aigües costaneres a l'hivern. Les balenes franques s'alimenten sobretot de copèpodes, però la seva dieta també inclou krill i pteròpodes. Cerquen el menjar a la superfície, sota l'aigua o fins i tot al fons del mar. Durant el festeig, es reuneixen grans grups de mascles per competir per una sola femella, la qual cosa suggereix que les competicions d'esperma són un factor important per l'aparellament. Encara que el rorqual blau sigui l'animal més gran del planeta, els testicles d'una balena franca són deu vegades més grans que els d'un rorqual blau;[1] cada un pesa fins a 525 kg, amb diferència els més grans de qualsevol animal.[2] La gestació tendeix a durar un any i les cries neixen amb quasi una tona de pes i entre 4 i 6 metres de llarg. El deslletament ocorre al cap de vuit mesos.

Les balenes franques eren una presa preferida pels baleners per mor de la seva naturalesa dòcil, els seus comportaments de filtratge a la superfície per obtenir menjar, la seva tendència per mantenir-se a prop de la costa i el seu alt contingut de ¿blubber?, que les fa flotar quan moren i produeix molta quantitat d'oli de balena. Avui dia, la balena franca comuna i E. japonica es troben entre les espècies més amenaçades del món[3] i ambdues estan protegides per l'Endangered Species Act als Estats Units. Les poblacions occidentals d'ambdues espècies estan en perill d'extinció, comptant-se per uns quants centenars de balenes franques. Les orientals, amb menys de 50 exemplars, estan en perill greu; de fet, la població oriental de balenes franques comunes suma una quinzena d'exemplars com a màxim i podria estar extinta per complet.[3] Tot i que la caça de balenes ja no és una amenaça, l'home segueix sent el principal enemic de les balenes franques: moltes moren colpejades per vaixells o atrapades per xarxes de pesca. Aquests dos factors combinats sumen el 48% de les defuncions de balenes franques comunes d'ençà del 1970.[4]

El 2018 les balenes pareixien no haver procreat.[5]

Les balenes franques (Eubalaena) són un gènere de balenes que comprèn tres espècies: la balena franca comuna (E. glacialis), E. japonica i E. australis. Juntament amb la balena de Groenlàndia (Balaena mysticetus) són les úniques espècies vivents de la família dels balènids. Al llarg dels últims dos segles la taxonomia d'aquestes espècies ha estat en flux constant i les balenes franques sovint han estat considerades com pertanyents al gènere Balaena, motiu pel qual la balena de Groenlàndia també rep el nom de balena franca àrtica. La balena franca pigmea (Capera marginata), una balena molt més petita de l'hemisferi sud, també estava inclosa a la família dels balènids, però recentment s'ha descobert que és prou diferent com per justificar una família pròpia, la dels neobalènids.

Les tres espècies són migratòries i es desplacen estacionalment per alimentar-se o donar a llum. Les aigües càlides de l'equador formen una barrera que isola les espècies d'un i altre hemisferi. Al nord, les balenes franques tendeixen a evitar les aigües obertes i a mantenir-se properes a les penínsules i badies i a les plataformes continentals, ja que aquestes zones encobreixen millor i hi ha menjar abundant. Al sud, les balenes franques s'alimenten lluny de la costa a l'estiu, però una gran majoria d'elles també opta per arrecerar-se en aigües costaneres a l'hivern. Les balenes franques s'alimenten sobretot de copèpodes, però la seva dieta també inclou krill i pteròpodes. Cerquen el menjar a la superfície, sota l'aigua o fins i tot al fons del mar. Durant el festeig, es reuneixen grans grups de mascles per competir per una sola femella, la qual cosa suggereix que les competicions d'esperma són un factor important per l'aparellament. Encara que el rorqual blau sigui l'animal més gran del planeta, els testicles d'una balena franca són deu vegades més grans que els d'un rorqual blau; cada un pesa fins a 525 kg, amb diferència els més grans de qualsevol animal. La gestació tendeix a durar un any i les cries neixen amb quasi una tona de pes i entre 4 i 6 metres de llarg. El deslletament ocorre al cap de vuit mesos.

Les balenes franques eren una presa preferida pels baleners per mor de la seva naturalesa dòcil, els seus comportaments de filtratge a la superfície per obtenir menjar, la seva tendència per mantenir-se a prop de la costa i el seu alt contingut de ¿blubber?, que les fa flotar quan moren i produeix molta quantitat d'oli de balena. Avui dia, la balena franca comuna i E. japonica es troben entre les espècies més amenaçades del món i ambdues estan protegides per l'Endangered Species Act als Estats Units. Les poblacions occidentals d'ambdues espècies estan en perill d'extinció, comptant-se per uns quants centenars de balenes franques. Les orientals, amb menys de 50 exemplars, estan en perill greu; de fet, la població oriental de balenes franques comunes suma una quinzena d'exemplars com a màxim i podria estar extinta per complet. Tot i que la caça de balenes ja no és una amenaça, l'home segueix sent el principal enemic de les balenes franques: moltes moren colpejades per vaixells o atrapades per xarxes de pesca. Aquests dos factors combinats sumen el 48% de les defuncions de balenes franques comunes d'ençà del 1970.

El 2018 les balenes pareixien no haver procreat.

Eubalaena ist eine Gattung der Glattwale, die mit dem Atlantischen Nordkaper (Eubalaena glacialis), dem Pazifischen Nordkaper (Eubalaena japonica) und dem Südkaper (Eubalaena australis) drei Walarten beinhaltet.

Die Glattwale der Gattung Eubalaena gehören als Bartenwale zu den größten Arten der Wale und damit zu den größten Tierarten überhaupt. Die beiden Nordkaper und der Südkaper sind etwa gleich groß und gleich schwer; sie werden meist etwa 15 Meter lang, maximal kann die Körperlänge 18 Meter erreichen. Ihr Gewicht liegt zwischen 50 und 56 Tonnen. Kennzeichnend sind die langen, dünnen, schwarzen Barten, die bei allen drei Arten etwa 2,5 Meter lang sind.

Als Glattwale besitzen sie keine Furchen an der Kehle, die für die Furchenwale typisch sind. Ihnen fehlt zudem eine Rückenfinne und die Flipper sind recht kurz, jedoch kräftig ausgebildet. Als Bewohner meist sehr kalter Meere bis hin zum Südpolarmeer besitzen sie einen extrem dicken Blubber. Diese Speckschicht, welche in ihrer Dicke die anderer Wale deutlich übertrifft, bietet Isolation gegen das kalte Wasser.

Die Nordkaper und der Südkaper unterscheiden sich von anderen Walarten und auch vom verwandtschaftlich nahestehenden Grönlandwal durch ihre auffälligen Hautwucherungen im Kopfbereich; vor allem der Ober- und Unterkiefer sowie der Augenbereich sind davon betroffen. Diese Hautwucherungen werden von Seepocken und Walläusen (Cyamus) besiedelt. Auffällig ist, dass diese sogenannten „Mützen“ bei Bullen ausgeprägter sind als bei Weibchen.

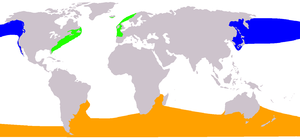

Die Arten leben bevorzugt in kalten Meeren, auf ihren Wanderungen erreichen sie jedoch auch warme Meeresteile in den Subtropen. Fast alle Gewässer um die Arktis werden von Glattwalen bewohnt, ebenso wie Großteile des Nordatlantiks und des Nordpazifiks. Hier leben der Atlantische Nordkaper und der Pazifische Nordkaper.[1][2]

Die südliche Hemisphäre wird vom Südkaper bewohnt, der alle südlichen Meere bis auf die Küsten der Antarktis bewohnt. Die Südküste Australiens, Teile der Küste Südamerikas und die Südküste Afrikas gehören zum von ihm bewohnten Areal.[3]

Verbreitung des Atlantischen Nordkapers

Verbreitung des Pazifischen Nordkapers

Verbreitung des Südkapers

Eubalaena-Arten sind langsam schwimmende Wale, die wie alle Bartenwale ihre Nahrung mit ihren Barten aus dem Wasser sieben; hauptsächlich bleiben Ruderfußkrebse darin hängen, aber auch kleine Fische.

Die Gattung Eubalaena beinhaltet mit dem Atlantischen Nordkaper (Eubalaena glacialis), dem Pazifischen Nordkaper (Eubalaena japonica) und dem Südkaper (Eubalaena australis) drei Arten. Diese bilden gemeinsam mit dem Grönlandwal (Balaena mysticetus) die Familie der Glattwale.[4]

Die Arten Eubalaena glacialis und Eubalaena japonica wurden bis zum Jahr 2000 als Unterarten der Art Eubalaena glacialis geführt. Jüngere DNA-Untersuchungen untermauerten die These, dass die beiden Unterarten zwei getrennte Arten sind.[5]

Eubalaena ist eine Gattung der Glattwale, die mit dem Atlantischen Nordkaper (Eubalaena glacialis), dem Pazifischen Nordkaper (Eubalaena japonica) und dem Südkaper (Eubalaena australis) drei Walarten beinhaltet.

Chiàⁿ hái-ang, sio̍k-tī Balaenidae kho ê ū keng-chhiu ê hái-ang, pun 2 ê sio̍k, 4 ê chéng: Eubalaena (Chiàⁿ Hái-ang, 3 ê chéng) kap Balaena (1 ê chéng, Chheⁿ-tē Hái-ang).

கருந்திமிங்கலங்கள் அல்லது கருப்பு திமிங்கலங்கள் (Right whales or Black whales) என்பது யூபலேனா(Eubalaena) இனத்தை சார்ந்தவை ஆகும். இதில் மூன்று வகை, பெரிய பலீன் திமிங்கலங்கள் உள்ளன.

அவைகள் பாலேனிடே(Balaenidae) குடும்பத்தில் இருக்கின்றன. வில் தலை (bowhead whale)திமிங்கலத்துடன் வகைப்படுத்தப்பட்டுள்ளன. கருந்திமிங்கலங்கள் ரோட்டண்ட் உடல்களைக் கொண்டுள்ளன. அவை ரோஸ்ட்ரம்ஸ், வி-வடிவ ப்ளோஹோல்ஸ் மற்றும் அடர் சாம்பல் அல்லது கருப்பு தோலினைப் பெற்றிருக்கின்றன. கருந்திமிங்கலங்கள் 18 மீ (59அடி) வரை நீளமாக வளரக்கூடியன. அதிகபட்சமாக 19.8 மீ (65 அடி) நீளம் வளரும். கருந்திமிங்கலங்கள் மிகவும் வலுவான திமிங்கலங்கள் ஆகும். 100 குறுகிய டன் (91 டி; 89 நீண்ட டன்) அல்லது அதற்கு மேற்பட்ட எடையுள்ளவை. மிகப்பெரிய கருந்திமிங்கலங்கள் 20.7 மீ (68 அடி) நீளத்தை அடையலாம் சில திமிங்கலம் 135,000 கிலோ எடையும், 21.3 மீ (70 அடி) வரை வளரும் தன்மையைக் கொண்டிருக்கின்றன.

இனச்சேர்க்கை பருவத்தில், வடக்கு அட்லாண்டிக் கருந் திமிங்கலங்களில் முந்தைய கணக்கெடுப்பின் படி, சராசரி வயது 7.5 முதல் 9 ஆண்டுகள் வரை மதிப்பிடப்பட்டுள்ளது. பெண் திமிங்கலங்கள், ஒவ்வொரு 3-5 வருடங்களுக்கும் இடையில் இனப்பெருக்கம் செய்கின்றன. பொதுவாகக் காணப்படும் கன்று ஈன்ற இடைவெளிகள் 3 ஆண்டுகளுக்கு ஒருமுறையும், பிற காரணிகளால் 2 முதல் 21 ஆண்டுகள் வரை கருத்தரிப்பு வேறுபடலாம்.

திமிங்கலங்களின் ஆயுட்காலம் பற்றிய புள்ளிவிவரங்கள், மிகக் குறைவாகவே அறியப்படுகிறது. நன்கு ஆவணப்படுத்தப்பட்ட சில நிகழ்வுகளில் ஒன்று, ஒரு பெண் வட அட்லாண்டிக் கருந் திமிங்கிலம் 1935 இல் ஒரு கன்றுடன் புகைப்படம் எடுக்கப்பட்டது. பின்னர் 1959, 1980, 1985 மற்றும் 1992 இல் மீண்டும் புகைப்படம் எடுக்கப்பட்டது. நிலையான கால்சோசிட்டி (callosity) முறைகள், அதே விலங்கு என்பதை உறுதிப்படுத்தின. அவை கடைசியாக, 1995 இல் தலையில் படுகாயத்துடன் புகைப்படம் எடுக்கப்பட்டாது. மறைமுகமாக ஒரு கப்பல் தாக்குதலில் இருந்திருக்கலாம். இவை கிட்டத்தட்ட 70 முதல் 100 வயதுக்கு வாழ்கின்றன. 210 ஆண்டுகள் நெருங்கிய தொடர்புடைய வில்ஹெட் திமிங்கலத்தைப் பற்றிய ஆராய்ச்சி முடிவுகள், இந்த வகைத் திமிங்கலங்களின் ஆயுட்காலம் அதிகமாக இருக்கலாம் என்று கூறுகிறது.

திமிங்கலங்களின் உணவுகள் ஜூப்ளாங்க்டன் (zooplankton), கோபேபாட்கள் (copepods) என அழைக்கப்படும் சிறிய ஓட்டுமீன்கள், அதே போல் கிரில் (krill) மற்றும் ஸ்டெரோபோட்கள் (pteropods) ஆகும். இவைகள் திறந்த வாயால் நீந்துகின்ற போது, அதனுள் தண்ணீர் இரையுடன் உள் வாங்க்கிக் கொண்டு நிரப்புகின்றன. பின்னர் திமிங்கலம் தண்ணீரை வெளியேற்றுகிறது. அதன் பலீன் தட்டுகளைப் பயன்படுத்தி இரையைத் தக்க வைத்துக் கொள்ளும் திறனைப் பெற்றுள்ளன. இதனை வேட்டையாடும் உயிரினங்கள் இரண்டாகும். கடல்வாழ் உயிரினமான ஓர்காக்களும், மனிதனும் இதனை வேட்டையாடுபவர்கள் என அறியப்பட்டுள்ளது.

மூன்று யூபலேனா இனங்கள் உலகின் மூன்று பகுதிகளில் வாழ்கின்றன. அவை மேற்கு அட்லாண்டிக் பெருங்கடல், வடக்கு அட்லாண்டிக், வட பசிபிக் என்பனவாகும். சப்பானில் இருந்து அலாஸ்கா மற்றும் தெற்கு பெருங்கடலின் அனைத்து பகுதிகளிலும் வாழ்கின்றன. அட்சரேகையில் 20 முதல் 60 டிகிரி வரை காணப்படும் மிதமான வெப்பநிலையை மட்டுமே திமிங்கலங்கள் வாழும் இயல்புடையவை. பெருங்கடல்கள் மிகப் பெரியவை என்பதால், திமிங்கலங்களின் எண்ணிக்கையில் துல்லியமாக அளவிடுவது மிகவும் கடினமாக உள்ளது. தோராயமான புள்ளிவிவரங்களின் படி, வடக்கு அட்லாண்டிக்கில், 400 கருந் திமிங்கலங்கள் (யூபலேனா பனிப்பாறை) வாழ்கின்றன. வடக்கு பசிபிக், 23 கருந் திமிங்கலங்கள் வாழ்கின்றன. கிழக்கு வடக்கு பசிபிக் (யூபலேனா ஜபோனிகா) மற்றும் தெற்கு அரைக்கோளத்தின் பகுதி முழுவதும், அதிகமாக ஏறத்தாழ 15,000 கருந் திமிங்கலங்கள் வாழ்கின்றன.

கருந்திமிங்கலங்கள் அல்லது கருப்பு திமிங்கலங்கள் (Right whales or Black whales) என்பது யூபலேனா(Eubalaena) இனத்தை சார்ந்தவை ஆகும். இதில் மூன்று வகை, பெரிய பலீன் திமிங்கலங்கள் உள்ளன.

வடக்கு அட்லாண்டிக் கருந் திமிங்கலம் (E. glacialis) வடக்கு பசிபிக் கருந் திமிங்கலம் (E. japonica) தெற்கு கருந் திமிங்கலம் (E. australis)அவைகள் பாலேனிடே(Balaenidae) குடும்பத்தில் இருக்கின்றன. வில் தலை (bowhead whale)திமிங்கலத்துடன் வகைப்படுத்தப்பட்டுள்ளன. கருந்திமிங்கலங்கள் ரோட்டண்ட் உடல்களைக் கொண்டுள்ளன. அவை ரோஸ்ட்ரம்ஸ், வி-வடிவ ப்ளோஹோல்ஸ் மற்றும் அடர் சாம்பல் அல்லது கருப்பு தோலினைப் பெற்றிருக்கின்றன. கருந்திமிங்கலங்கள் 18 மீ (59அடி) வரை நீளமாக வளரக்கூடியன. அதிகபட்சமாக 19.8 மீ (65 அடி) நீளம் வளரும். கருந்திமிங்கலங்கள் மிகவும் வலுவான திமிங்கலங்கள் ஆகும். 100 குறுகிய டன் (91 டி; 89 நீண்ட டன்) அல்லது அதற்கு மேற்பட்ட எடையுள்ளவை. மிகப்பெரிய கருந்திமிங்கலங்கள் 20.7 மீ (68 அடி) நீளத்தை அடையலாம் சில திமிங்கலம் 135,000 கிலோ எடையும், 21.3 மீ (70 அடி) வரை வளரும் தன்மையைக் கொண்டிருக்கின்றன.

Right whales are three species of large baleen whales of the genus Eubalaena: the North Atlantic right whale (E. glacialis), the North Pacific right whale (E. japonica) and the Southern right whale (E. australis). They are classified in the family Balaenidae with the bowhead whale. Right whales have rotund bodies with arching rostrums, V-shaped blowholes and dark gray or black skin. The most distinguishing feature of a right whale is the rough patches of skin on its head, which appear white due to parasitism by whale lice. Right whales are typically 13–17 m (43–56 ft) long and weigh up to 100 short tons (91 t; 89 long tons) or more.

All three species are migratory, moving seasonally to feed or give birth. The warm equatorial waters form a barrier that isolates the northern and southern species from one another although the southern species, at least, has been known to cross the equator. In the Northern Hemisphere, right whales tend to avoid open waters and stay close to peninsulas and bays and on continental shelves, as these areas offer greater shelter and an abundance of their preferred foods. In the Southern Hemisphere, right whales feed far offshore in summer, but a large portion of the population occur in near-shore waters in winter. Right whales feed mainly on copepods but also consume krill and pteropods. They may forage the surface, underwater or even the ocean bottom. During courtship, males gather into large groups to compete for a single female, suggesting that sperm competition is an important factor in mating behavior. Gestation tends to last a year, and calves are weaned at eight months old.

Right whales were a preferred target for whalers because of their docile nature, their slow surface-skimming feeding behaviors, their tendency to stay close to the coast, and their high blubber content (which makes them float when they are killed, and which produced high yields of whale oil). Although the whales no longer face pressure from commercial whaling, humans remains by far the greatest threat to these species: the two leading causes of death are being struck by ships and entanglement in fishing gear. Today, the North Atlantic and North Pacific right whales are among the most endangered whales in the world.

A common explanation for the name right whales is that they were regarded as the right ones to hunt,[9] as they float when killed and often swim within sight of shore. They are quite docile and do not tend to shy away from approaching boats. As a result, they were hunted nearly to extinction during the active years of the whaling industry. However, this origin is questionable: in his history of American whaling, Eric Jay Dolin writes:

Despite this highly plausible rationale, nobody actually knows how the right whale got its name. The earliest references to the right whale offer no indication why it was called that, and some who have studied the issue point out that the word "right" in this context might just as likely be intended "to connote 'true' or 'proper,' meaning typical of the group."

— E.J. Dolin, Leviathan: The History of Whaling in America, quoting a 1766 Connecticut Courant newspaper article.[10]

For the scientific names, the generic name Eubalaena means "good or true whales", and specific names include glacialis ("ice") for North Atlantic species, australis ("southern") for Southern Hemisphere species, and japonica ("Japanese") for North Pacific species. [11]

The right whales were first classified in the genus Balaena in 1758 by Carl Linnaeus, who at the time considered all of the right whales (including the bowhead) as a single species. Through the 1800s and 1900s, in fact, the family Balaenidae has been the subject of great taxonometric debate. Authorities have repeatedly recategorized the three populations of right whale plus the bowhead whale, as one, two, three or four species, either in a single genus or in two separate genera. In the early whaling days, they were all thought to be a single species, Balaena mysticetus. Eventually, it was recognized that bowheads and right whales were in fact different, and John Edward Gray proposed the genus Eubalaena for the right whale in 1864. Later, morphological factors such as differences in the skull shape of northern and southern right whales indicated at least two species of right whale – one in the Northern Hemisphere, the other in the Southern Ocean.[12] As recently as 1998, Rice, in his comprehensive and otherwise authoritative classification listed just two species: Balaena glacialis (the right whales) and Balaena mysticetus (the bowheads).[13]

In 2000, two studies of DNA samples from each of the whale populations concluded the northern and southern populations of right whale should be considered separate species. What some scientists found more surprising was the discovery that the North Pacific and North Atlantic populations are also distinct, and that the North Pacific species is more closely related to the southern right whale than to the North Atlantic right whale.[14][15] The authors of one of these studies concluded that these species have not interbred for between 3 million and 12 million years.[15]

In 2001, Brownell et al. reevaluated the conservation status of the North Pacific right whale as a distinct species,[16] and in 2002, the Scientific Committee of the International Whaling Commission (IWC) accepted Rosenbaum's findings, and recommended that the Eubalaena nomenclature be retained for this genus.[17]

A 2007 study by Churchill provided further evidence to conclude that the three different living right whale species constitute a distinct phylogenetic lineage from the bowhead, and properly belong to a separate genus.[18]

The following cladogram of the family Balaenidae serves to illustrate the current scientific consensus as to the relationships between the three right whales and the bowhead whale.

Family Balaenidae BalaenidaeE. glacialis (North Atlantic right whale)

E. japonica (North Pacific right whale)

E. australis (Southern right whale)

B. mysticetus bowhead whale

(bowhead whales) The right whales, genus Eubalaena, in the family Balaenidae[14]A cladogram is a tool for visualizing and comparing the evolutionary relationships between taxa; the point where each node branches is analogous to an evolutionary branching – the diagram can be read left-to-right, much like a timeline.

Whale lice, parasitic cyamid crustaceans that live off skin debris, offer further information through their own genetics. Because these lice reproduce much more quickly than whales, their genetic diversity is greater. Marine biologists at the University of Utah examined these louse genes and determined their hosts split into three species 5–6 million years ago, and these species were all equally abundant before whaling began in the 11th century.[19] The communities first split because of the joining of North and South America. The rising temperatures of the equator then created a second split, into northern and southern groups, preventing them from interbreeding.[20] "This puts an end to the long debate about whether there are three Eubalaena species of right whale. They really are separate beyond a doubt", Jon Seger, the project's leader, told BBC News.[21]

The pygmy right whale (Caperea marginata), a much smaller whale of the Southern Hemisphere, was until recently considered a member of the Family Balaenidae. However, they are not right whales at all, and their taxonomy is presently in doubt. Most recent authors place this species into the monotypic Family Neobalaenidae,[22] but a 2012 study suggests that it is instead the last living member of the Family Cetotheriidae, a family previously considered extinct.[23]

Yet another species of right whale was proposed by Emanuel Swedenborg in the 18th century—the so-called Swedenborg whale. The description of this species was based on a collection of fossil bones unearthed at Norra Vånga, Sweden, in 1705 and believed to be those of giants. The bones were examined by Swedenborg, who realized they belong to a species of whale. The existence of this species has been debated, and further evidence for this species was discovered during the construction of a motorway in Strömstad, Sweden in 2009.[24] To date, however, scientific consensus still considers Hunterius swedenborgii to be a North Atlantic right whale.[25] According to a DNA analysis conducted, it was later confirmed that the fossil bones are actually from a bowhead whale.[26]

Adult right whales are typically 13–16 m (43–52 ft) long. They have extremely thick bodies with a girth as much as 60% of total body length in some cases. They have large, broad and blunt pectoral flippers and the deeply notched, smoothly tipped tail flukes make up to 40% of their body length. The North Pacific species is on average the largest of the three species. weigh 100 short tons (91 t; 89 long tons). The upper jaw of a right whale is a bit arched, and the lower lip is strongly curved. On each side of the upper jaw are 200–270 baleen plates. These are narrow and approximately 2–2.8 m (6.6–9.2 ft) long, and are covered in very thin hairs.[27] Right whales have a distinctive wide V-shaped blow, caused by the widely spaced blowholes on the top of the head. The blow rises 5 m (16 ft) above the surface.[28]

The skin is generally black with occasional white blotches on the body, while some individuals have mottled patterns.[27] Unlike other whales, a right whale has distinctive callosities (roughened patches of skin) on its head. The callosities appear white due to large colonies of cyamids (whale lice).[12][29] Each individual has a unique callosities pattern. In 2016, a competitive effort resulted in the use of facial recognition software to derive a process to uniquely identify right whales with about 87% accuracy based on their callosities.[30] The primary role of callosities has been considered to be protection against predators. Right whale declines might have also reduced barnacles.[31]

An unusually large 40% of their body weight is blubber, which is of relatively low density. Consequently, unlike many other species of whale, dead right whales tend to float.[32][33] Many southern right whales are seen with rolls of fats behind blowholes that northern species often lack, and these are regarded as a sign of better health condition due to sufficient nutrition supply, and could have contributed in vast differences in recovery status between right whales in the southern and northern hemisphere, other than direct impacts by humankind.[34]

The penis on a right whale can be up to 2.7 m (8.9 ft) – the testes, at up to 2 m (6.6 ft) in length, 78 cm (2.56 ft) in diameter, and weighing up to 525 kg (1157 lbs), are also by far the largest of any animal on Earth.[35] The blue whale may be the largest animal on the planet, yet the testicles of the right whale are ten times the size of those of the blue whale. They also exceed predictions in terms of relative size, being six times larger than would be expected on the basis of body mass. Together, the testicles make up nearly 1% of the right whale's total body weight. This strongly suggests sperm competition is important in mating, which correlates to the fact that right whales are highly promiscuous.[28][36]

The three Eubalaena species inhabit three distinct areas of the globe: the North Atlantic in the western Atlantic Ocean, the North Pacific in a band from Japan to Alaska and all areas of the Southern Ocean. The whales can only cope with the moderate temperatures found between 20 and 60 degrees in latitude. The warm equatorial waters form a barrier that prevents mixing between the northern and southern groups with minor exclusions.[37] Although the southern species in particular must travel across open ocean to reach its feeding grounds, the species is not considered to be pelagic. In general, they prefer to stay close to peninsulas and bays and on continental shelves, as these areas offer greater shelter and an abundance of their preferred foods.[20]

Because the oceans are so large, it is very difficult to accurately gauge whale population sizes. Approximate figures:[18]

Almost all of the 400 North Atlantic right whales live in the western North Atlantic Ocean. In northern spring, summer and autumn, they feed in areas off the Canadian and northeast U.S. coasts in a range stretching from New York to Newfoundland. Particularly popular feeding areas are the Bay of Fundy and Cape Cod Bay. In winter, they head south towards Georgia and Florida to give birth.[38] There have been a smattering of sightings further east over the past few decades; several sightings were made close to Iceland in 2003. These are possibly the remains of a virtually extinct eastern Atlantic stock, but examination of old whalers' records suggests they are more likely to be strays.[18] However, a few sightings have happened between Norway, Ireland, Spain, Portugal, the Canary Islands and Italy;[39][40] at least the Norway individuals come from the Western stock.[41]

The North Pacific right whale appears to occur in two populations. The population in the eastern North Pacific/Bering Sea is extremely low, numbering about 30 individuals.[42] A larger western population of 100–200 appears to be surviving in the Sea of Okhotsk, but very little is known about this population. Thus, the two northern right whale species are the most endangered of all large whales and two of the most endangered animal species in the world. Based on current population density trends, both species are predicted to become extinct within 200 years.[43] The Pacific species was historically found in summer from the Sea of Okhotsk in the west to the Gulf of Alaska in the east, generally north of 50°N. Today, sightings are very rare and generally occur in the mouth of the Sea of Okhotsk and in the eastern Bering Sea. Although this species is very likely to be migratory like the other two species, its movement patterns are not known.[44]

The last major population review of southern right whales by the International Whaling Commission was in 1998. Researchers used data about adult female populations from three surveys (one in each of Argentina, South Africa and Australia) and extrapolated to include unsurveyed areas and estimated counts of males and calves (using available male:female and adult:calf ratios), giving an estimated 1997 population of 7,500 animals. More recent data from 2007 indicate those survey areas have shown evidence of strong recovery, with a population approaching twice that of a decade earlier. However, other breeding populations are still very small, and data are insufficient to determine whether they, too, are recovering.[3]

The southern right whale spends the summer months in the far Southern Ocean feeding, probably close to Antarctica. It migrates north in winter for breeding, and can be seen around the coasts of Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Chile, Mozambique, New Zealand, South Africa and Uruguay.[45] The South American, South African and Australasian groups apparently intermix very little, if at all, because of the strong fidelity of mothers to their feeding and calving grounds. The mother passes these instincts to her calves.[18]

Right whales swim slowly, reaching only 5 kn (9.3 km/h) at top speed. However, they are highly acrobatic and frequently breach (jump clear of the sea surface), tail-slap and lobtail.[27]

The right whales' diets consist primarily of zooplankton, primarily the tiny crustaceans called copepods, as well as krill, and pteropods, although they are occasionally opportunistic feeders. As with other baleens, they feed by filtering prey from the water. They swim with an open mouth, filling it with water and prey. The whale then expels the water, using its baleen plates to retain the prey. Prey must occur in sufficient numbers to trigger the whale's interest, be large enough that the baleen plates can filter it, and be slow enough that it cannot escape. The "skimming" may take place on the surface, underwater, or even at the seabed, indicated by mud occasionally observed on right whales' bodies.[18]

The right whales' two known predators are humans and orcas. When danger lurks, a group of right whales may cluster into a circle, and thrash their outwards-pointing tails. They may also head for shallow water, which sometimes proves to be an ineffective defense. Aside from the strong tails and massive heads equipped with callosities,[31] the sheer size of this animal is its best defense, making young calves the most vulnerable to orca and shark attacks.[28]

Vocalizations made by right whales are not elaborate compared to those made by other whale species. The whales make groans, pops and belches typically at frequencies around 500 Hz. The purpose of the sounds is not known but may be a form of communication between whales within the same group. Northern right whales responded to sounds similar to police sirens—sounds of much higher frequency than their own. On hearing the sounds, they moved rapidly to the surface. The research was of particular interest because northern rights ignore most sounds, including those of approaching boats. Researchers speculate this information may be useful in attempts to reduce the number of ship-whale collisions or to encourage the whales to surface for ease of harvesting.[43][46]

During the mating season, which can occur at any time in the North Atlantic, right whales gather into "surface-active groups" made up of as many as 20 males consorting a single female. The female has her belly to the surface while the males stroke her with their flippers or keep her underwater. The males do not compete as aggressively against each other as male humpbacks. The female may not become pregnant but she is still able to assess the condition of potential mates.[18] The mean age of first parturition in North Atlantic right whales is estimated at between 7.5[47] and 9[48] years. Females breed every 3–5 years;[47][49] the most commonly seen calving intervals are 3 years and may vary from 2 up to 21 years due to multiple factors.[50][51]

Both reproduction and calving take place during the winter months.[52] Calves are approximately 1 short ton (0.91 t; 0.89 long tons) in weight and 4–6 m (13–20 ft) in length at birth following a gestation period of 1 year. The right whale grows rapidly in its first year, typically doubling in length. Weaning occurs after eight months to one year and the growth rate in later years is not well understood—it may be highly dependent on whether a calf stays with its mother for a second year.[18]

Respective congregation areas in the same region may function as for different objectives for whales.[53]

Very little is known about the life span of right whales. One of the few well-documented cases is of a female North Atlantic right whale that was photographed with a baby in 1935, then photographed again in 1959, 1980, 1985, and 1992. Consistent callosity patterns ensured it was the same animal. She was last photographed in 1995 with a seemingly fatal head wound, presumably from a ship strike. By conservative estimates (e.g. she was a new mother who had just reached sexual maturity in 1935), she was nearly 70 years to more than 100 years of age, if not older.[54] Research on the closely related bowhead whale exceeding 210 years suggests this lifespan is not uncommon and may even be exceeded.[18][55]

In the early centuries of shore-based whaling before 1712, right whales were virtually the only catchable large whales, for three reasons:

Basque people were the first to hunt right whales commercially, beginning as early as the 11th century in the Bay of Biscay. They initially sought oil, but as meat preservation technology improved, the animal was also used for food. Basque whalers reached eastern Canada by 1530[18] and the shores of Todos os Santos Bay (in Bahia, Brazil) by 1602. The last Basque voyages were made before the Seven Years' War (1756–1763). All attempts to revive the trade after the war failed. Basque shore whaling continued sporadically into the 19th century.

"Yankee whalers" from the new American colonies replaced the Basques. Setting out from Nantucket, Massachusetts, and Long Island, New York, they took up to a hundred animals in good years. By 1750, the commercial hunt of the North Atlantic right whale was essentially over. The Yankee whalers moved into the South Atlantic before the end of the 18th century. The southernmost Brazilian whaling station was established in 1796, in Imbituba. Over the next hundred years, Yankee whaling spread into the Southern and Pacific Oceans, where the Americans were joined by fleets from several European nations. The beginning of the 20th century saw much greater industrialization of whaling, and the harvest grew rapidly. According to whalers' records, by 1937 there had been 38,000 takes in the South Atlantic, 39,000 in the South Pacific, 1,300 in the Indian Ocean, and 15,000 in the North Pacific. The incompleteness of these records means the actual take was somewhat higher.[57]

As it became clear the stocks were nearly depleted, the world banned right whaling in 1937. The ban was largely successful, although violations continued for several decades. Madeira took its last two right whales in 1968. Japan took twenty-three Pacific right whales in the 1940s and more under scientific permit in the 1960s. Illegal whaling continued off the coast of Brazil for many years, and the Imbituba land station processed right whales until 1973. The Soviet Union illegally took at least 3,212 southern right whales during the 1950s and '60s, although it reported taking only four.[58]

The southern right whale has made Hermanus, South Africa, one of the world centers for whale watching. During the winter months (July–October), southern right whales come so close to the shoreline, visitors can watch whales from strategically placed hotels.[59] The town employs a "whale crier" (cf. town crier) to walk through the town announcing where whales have been seen.[60] In Brazil, Imbituba in Santa Catarina has been recognized as the National Right Whale Capital and holds annual Right Whale Week celebrations in September[61] when mothers and calves are more often seen. The old whaling station there has been converted to a museum dedicated to the whales.[62] In winter in Argentina, Península Valdés in Patagonia hosts the largest breeding population of the species, with more than 2,000 animals catalogued by the Whale Conservation Institute and Ocean Alliance.[63]

Both the North Atlantic and North Pacific species are listed as a "species threatened with extinction which [is] or may be affected by trade" (Appendix I) by CITES, and as "endangered" by the IUCN Red List. In the United States, the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), a subagency of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has classified all three species as "endangered" under the Endangered Species Act. Under the Marine Mammal Protection Act, they are listed as "depleted".[64][65][66]

The southern right whale is listed as "endangered" under the Australian Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act, as "nationally endangered" under the New Zealand Threat Classification System, as a "natural monument" by the Argentine National Congress, and as a "State Natural Monument" under the Brazilian National Endangered Species List.[66]

The US and Brazil added new protections for right whales in the 2000s to address the two primary hazards. While environmental campaigners were, as reported in 2001, pleased about the plan's positive effects, they attempted to force the US government to do more.[67] In particular, they advocated 12 knots (22 km/h) speed limits for ships within 40 km (25 mi) of US ports in times of high right whale presence. Citing concerns about excessive trade disruption, it did not institute greater protections. The Defenders of Wildlife, the Humane Society of the United States and the Ocean Conservancy sued the NMFS in September 2005 for "failing to protect the critically endangered North Atlantic Right Whale, which the agency acknowledges is 'the rarest of all large whale species' and which federal agencies are required to protect by both the Marine Mammal Protection Act and the Endangered Species Act", demanding emergency protection measures.[68]

The southern right whale, listed as "endangered" by CITES and "lower risk - conservation dependent" by the IUCN, is protected in the jurisdictional waters of all countries with known breeding populations (Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Chile, New Zealand, South Africa and Uruguay). In Brazil, a federal Environmental Protection Area encompassing some 1,560 km2 (600 sq mi) and 130 km (81 mi) of coastline in Santa Catarina State was established in 2000 to protect the species' main breeding grounds in Brazil and promote whale watching.[69]

On February 6, 2006, NOAA proposed its Strategy to Reduce Ship Strikes to North Atlantic Right Whales.[70] The proposal, opposed by some shipping interests, limited ship speeds during calving season. The proposal was made official when on December 8, 2008, NOAA issued a press release that included the following:[71]

In 2020, NOAA published its assessment and found that since the speed rule was adopted, the total number of documented deaths from vessel strike decreased but serious and non-serious injuries have increased.[72] A report by the organization Oceana found that between 2017 and 2020, disobedience of the rule reached close to 90% in mandatory speed zones while in voluntary areas, disobedience neared 85%.[73]

The leading cause of death among the North Atlantic right whale, which migrates through some of the world's busiest shipping lanes while journeying off the east coast of the United States and Canada, is being struck by ships.[note 1][74] At least sixteen ship-strike deaths were reported between 1970 and 1999, and probably more remain unreported.[18] According to NOAA, twenty-five of the seventy-one right whale deaths reported since 1970 resulted from ship strikes.[71]

A second major cause of morbidity and mortality in the North Atlantic right whale is entanglement in plastic fishing gear. Right whales ingest plankton with wide-open mouths, risking entanglement in any rope or net fixed in the water column. Rope wraps around their upper jaws, flippers and tails. Some are able to escape, but others remain tangled.[75] Whales can be successfully disentangled, if observed and aided. In July 1997, the U.S. NOAA introduced the Atlantic Large Whale Take Reduction Plan, which seeks to minimize whale entanglement in fishing gear and record large whale sightings in an attempt to estimate numbers and distribution.[76]

In 2012, the U.S. Navy proposed to create a new undersea naval training range immediately adjacent to northern right whale calving grounds in shallow waters off the Florida/Georgia border. Legal challenges by leading environmental groups including the Natural Resources Defense Council were denied in federal court, allowing the Navy to proceed.[77][78] These rulings were made despite the extremely low numbers (as low as 313 by some estimates) of right whales in existence at this time, and a very poor calving season.[79]

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) {{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Right whales are three species of large baleen whales of the genus Eubalaena: the North Atlantic right whale (E. glacialis), the North Pacific right whale (E. japonica) and the Southern right whale (E. australis). They are classified in the family Balaenidae with the bowhead whale. Right whales have rotund bodies with arching rostrums, V-shaped blowholes and dark gray or black skin. The most distinguishing feature of a right whale is the rough patches of skin on its head, which appear white due to parasitism by whale lice. Right whales are typically 13–17 m (43–56 ft) long and weigh up to 100 short tons (91 t; 89 long tons) or more.

All three species are migratory, moving seasonally to feed or give birth. The warm equatorial waters form a barrier that isolates the northern and southern species from one another although the southern species, at least, has been known to cross the equator. In the Northern Hemisphere, right whales tend to avoid open waters and stay close to peninsulas and bays and on continental shelves, as these areas offer greater shelter and an abundance of their preferred foods. In the Southern Hemisphere, right whales feed far offshore in summer, but a large portion of the population occur in near-shore waters in winter. Right whales feed mainly on copepods but also consume krill and pteropods. They may forage the surface, underwater or even the ocean bottom. During courtship, males gather into large groups to compete for a single female, suggesting that sperm competition is an important factor in mating behavior. Gestation tends to last a year, and calves are weaned at eight months old.

Right whales were a preferred target for whalers because of their docile nature, their slow surface-skimming feeding behaviors, their tendency to stay close to the coast, and their high blubber content (which makes them float when they are killed, and which produced high yields of whale oil). Although the whales no longer face pressure from commercial whaling, humans remains by far the greatest threat to these species: the two leading causes of death are being struck by ships and entanglement in fishing gear. Today, the North Atlantic and North Pacific right whales are among the most endangered whales in the world.

Taŭgaj balenoj, eŭbalenoj laŭ la latina scienca nomo Eŭbalaena aŭ pli konataj kiel veraj balenoj estas tri specioj de grandaj balenoj en la familio de Balenedoj (Balaenidae) kaj de la ordo de Cetacoj (Cetacea).

Ili estas nomataj "taŭgaj balenoj" ĉar balenĉasistoj pensis ke ili estas bone taŭgaj por ĉasado, ĉar ili ne estas tre rapidaj, flosas post kiam ili estas mortigitaj kaj ofte naĝas ene de la vido el ŝipobordo. Ili estas ankaŭ amikemaj. Pro tio, ili ĉasis ilin ĝis preskaŭ ties malapero. Hodiaŭ, anstataŭ ĉasi ilin, oni rigardas ilin por plezuro.

Taŭgaj balenoj, eŭbalenoj laŭ la latina scienca nomo Eŭbalaena aŭ pli konataj kiel veraj balenoj estas tri specioj de grandaj balenoj en la familio de Balenedoj (Balaenidae) kaj de la ordo de Cetacoj (Cetacea).

Ili estas nomataj "taŭgaj balenoj" ĉar balenĉasistoj pensis ke ili estas bone taŭgaj por ĉasado, ĉar ili ne estas tre rapidaj, flosas post kiam ili estas mortigitaj kaj ofte naĝas ene de la vido el ŝipobordo. Ili estas ankaŭ amikemaj. Pro tio, ili ĉasis ilin ĝis preskaŭ ties malapero. Hodiaŭ, anstataŭ ĉasi ilin, oni rigardas ilin por plezuro.

Eubalaena es un género de cetáceos misticetos de la familia Balaenidae,[1] conocidos comúnmente como ballenas francas debido a que nadan lentamente y flotan después de muertas; es por esto que los balleneros las consideraban las más fáciles o "francas" de cazar.[cita requerida]

Presentan una cabeza roma con enormes hileras de barbas, cuerpo grueso, azul oscuro, con manchas blancas en la parte ventral, y carecen de aleta dorsal. Se alimentan de plancton y tienen una cría cada tres o cuatro años.

Familia Balaenidae

Desde 2016 es la imagen del billete de 200 pesos de la República Argentina.

Eubalaena es un género de cetáceos misticetos de la familia Balaenidae, conocidos comúnmente como ballenas francas debido a que nadan lentamente y flotan después de muertas; es por esto que los balleneros las consideraban las más fáciles o "francas" de cazar.[cita requerida]

Eubalaena generoko Balaenidae familiako animalia da. Artiodaktiloen barruko sailkatuta dago.

Eubalaena generoko Balaenidae familiako animalia da. Artiodaktiloen barruko sailkatuta dago.

Eubalaena est un genre qui regroupe trois espèces de cétacé de la famille des Balaenidae.

Une explication populaire de l'origine du nom d’Eubalaena (la « bonne baleine », en anglais right whale) est qu'il s'agit d'une baleine facile à chasser car elle se déplace lentement, est peu farouche (ne fuit pas en présence d'un plongeur ou d'un navire) et flotte une fois morte[1].

Contrairement aux autres baleines, Eubalaena a des callosités (excroissances calleuses causées par la prolifération de colonies de poux des baleines, de couleur jaune clair, orange ou rose[3]) sur la tête qui sont caractéristiques de chaque individu, un large dos sans nageoire dorsale, parfois des taches blanches sur le ventre, un long rostre arqué (museau qui commence au-dessus de l'œil). Les baleines franches peuvent atteindre jusqu'à 18 mètres de long et peser jusqu'à 100 tonnes, soit nettement plus que les baleines grises ou à bosses, mais moins que les baleines bleues. Chiffre anormalement élevé, 40 % de leur poids corporel est constitué par de la graisse sous-cutanée de faible densité. Aussi, contrairement à beaucoup d'autres espèces de baleines, les Eubalaena mortes ont tendance à flotter. Les baleines franches nagent lentement, atteignant une vitesse maximum de 5 nœuds (9,3 km/h). Cependant, elles sont très acrobatiques et ont de fréquents sauts caractéristiques (le « breaching »), donnant des coups de queue et de nageoire à la surface de l'eau[4].

En moyenne, les adultes ont une longueur comprise entre 11 et 18 m et pèsent 54 à 73 tonnes. Le corps est très massif avec un tour de taille qui peut atteindre 60 % de la longueur totale du corps dans certains cas. La nageoire est large, jusqu'à 40 % de la longueur du corps. Eubalaena japonica est la plus grande des trois espèces. Les baleines franches ont un souffle issu des évents en forme de V distinctif, pouvant atteindre 5 mètres au-dessus de la surface de l'eau. Les baleines franches ont entre 200 et 300 fanons de chaque côté de la bouche. Ceux-ci, couverts de poils très fins, sont étroits et font environ 2 mètres de longueur[5].

Eubalaena est un genre qui regroupe trois espèces de cétacé de la famille des Balaenidae.

Eubalaena é un xénero de cetáceos misticetos da familia dos balénidos que comprende tres especies que son coñecidas comunmente como baleas francas debido a que nadan lentamente e flotan despois de mortas, polo que os baleeiros as consideraban as máis fáciles ou "francas" de cazar e de transportar ás factorías onde se despezaban.

As baleas francas teñen unha cabeza roma con enormes fileiras de barbas moi longas, que forman como unha especie de láminas; cando a boca está pechada, as barbas permanecen cubertas por uns labios inferiores de gran tamaño. O corpo é groso, ancho e repoludo, de cor azul escuro, con manchas brancas na parte ventral. Carecen de aleta dorsal, a caudal é ancha, cunha fendedura clara no medio, e as pectorais algo máis longas e largas que as da outra especie da familia, a balea de Groenlandia (Balaena mysticetus). Presentan unhas calosidades por riba dos ollos, ao redor dos espiráculos, no mento, os labios inferiores e na mandíbula superior. Aliméntanse de plancto (krill e outros pequenos invertebrados). Teñen unha cría cada tres ou catro anos. Os adultos alcanzan lonxitudes de entre os 11 e os 18 m, e os baleatos, ao naceren, miden de 4,5 a 6 m.[2]

Eubalaena glacialis habita no Atlántico norte, onde existen dúas subpoboacións, a máis numerosa nas costas do oeste, con ao redor de 400 exemplares, que se estenden desde a illa de Terra Nova e as costas da península do Labrador (Canadá), até as de Xeorxia e a Florida (Estados Unidos; as súas zonas de alimentación está no norte desta área, na parte baixa da baía de Fundy, preto da illa Grand Manan, Nova Escocia (Canadá) e a baía de cabo Cod (Massachusetts), mentres que as zonas de reprodución están máis ao sur, observándose recentemente grupos de cría na Florida.[2]

A subpoboación do Atlántico oriental é moito menor. Antano estendíase desde as costas de Islandia e Noruega até as do mar Cantábrico (incluídas as galegas), pasando polas de Irlanda, as occidentais da Gran Bretaña, as francesas desde a Bretaña até o golfo de Biscaia,[2] chegando nas súas migracións até os arquipélagos das Azores, Madeira e as Canarias.[3]

Os escasos individuos de Eubalaena japonica habitan no Pacífico norte, reproducíndose durante o verán no mar de Okhotsk, ao sueste do mar de Bering, as illas Aleutianas e no norte do golfo de Alasca. Durante o inverno migran cara o sur (ou, polo menos, migraban antano), até o mar do Xapón, o estreito de Taiwán e as illas Bonin (Xapón), no oeste, e até a Baixa California Sur (México), no leste.[4] Observáronse individuos divagantes nas illas Hawai.[5][6]

A baleas francas austrais (Eubalaena australis) son circumpolares, rexistrándose a súa presenza polo menos entre os 20º S e os 55º S. Reprodúcense en inverno nas costas do subcontinente suramericano, principalmente nas da Arxentina e do Brasil, aínda que tamén algúns individuos o fan nas de Chile o Perú, e nas da illa de Tristán da Cunha, sur de África, principalmente nas da República Surafricana, chegando até Mozambique e as costas occidentais de Madagascar, e o sur de Australia, Tasmania e Nova Zelandia, migrando en verán cara ás augas frías da Antártida,[2][7] No verán migran cara ás augas frías da Antártida, onde se encontran principalmente entre as latitudes 40º S e 50º S.[7], aínda que tamén se puideron ver, especialmente nos últimos anos, na Antártida, tan ao sur como nos 65° S,[8] e nos arredores de Xeorxia do Sur.[9]

As baleas francas nadan lentamente, pero son capaces de facer sorprendentes acrobacias. Poden observarse ondulando as aletas pectorais sobre a superficie, saltando, golpeando a agua coas aletas pectorais e movendo a caudal. Nadan cerca das costas coa boca aberta, mostrando as barbas. Son curiosas e ás veces xogan con obxectos flotantes. Os membros de grupos pequenos poden saír á superficie por quendas, só un cada vez. Adoitan facer vocalizacións nas zona de cría, sobre todo de noite.[2]

Cladograma da familia dos balénidos:

Balaenidae Eubalaena BalaenaEubalaena é un xénero de cetáceos misticetos da familia dos balénidos que comprende tres especies que son coñecidas comunmente como baleas francas debido a que nadan lentamente e flotan despois de mortas, polo que os baleeiros as consideraban as máis fáciles ou "francas" de cazar e de transportar ás factorías onde se despezaban.

Paus sikat adalah paus balin yang masuk kedalam genus Eubalaena. Tiga spesies paus sikat diakui dalam genus ini. Terkadang famili Balaenidae dianggap sebagai famili paus sikat. Paus sikat dapat tumbuh sampai 18 meter, dengan massa 100 ton.

Paus sikat adalah paus balin yang masuk kedalam genus Eubalaena. Tiga spesies paus sikat diakui dalam genus ini. Terkadang famili Balaenidae dianggap sebagai famili paus sikat. Paus sikat dapat tumbuh sampai 18 meter, dengan massa 100 ton.

Eubalaena è un genere di cetacei misticeti cui appartengono tre specie, note comunemente come balene franche.

Talvolta l'intera famiglia dei Balenidi viene indicata come la famiglia delle balene franche. Anche la balena della Groenlandia, unica specie del genere Balaena, appartiene a questa famiglia, e viene pertanto considerata anch'essa una balena franca. Comunque, in quest'articolo parleremo solo delle specie di Eubalaena.

Le balene franche possono raggiungere una lunghezza di 18 m e pesare fino a 70 tonnellate.[1] Il loro corpo rotondeggiante è quasi completamente nero e sulla testa presenta caratteristiche callosità (zone di pelle ruvida). Vengono chiamate «balene franche» poiché i balenieri le ritenevano le balene «giuste» da cacciare, dal momento che galleggiano una volta uccise e spesso nuotano nei pressi della costa, rendendole individuabili perfino da riva. Il loro numero è stato enormemente ridotto a causa dei grandi massacri perpetrati durante i floridi anni dell'industria baleniera. Oggi, invece di cacciarle, le persone spesso osservano questi animali acrobatici per puro piacere.

Le tre specie di Eubalaena vivono in località distinte. Tra queste:

Su come classificare le tre popolazioni di balene franche Eubalaena le autorità si sono da sempre trovate in disaccordo: infatti, a seconda degli autori, sono state riconosciute una, due o tre specie. Ai tempi della baleneria si riteneva che appartenessero tutte ad una sola specie diffusa in tutto il mondo. In seguito, alcuni fattori morfologici, come piccole differenze nella forma del cranio tra gli animali boreali e australi, indicarono la presenza di almeno due specie - una diffusa esclusivamente nell'emisfero boreale e l'altra diffusa nell'Oceano Meridionale[2]. Tuttavia, non è mai stato osservato nessun gruppo di balene franche nuotare nelle calde acque equatoriali per prendere contatti con le altre (sotto)specie e (in)incrociarsi: il loro spesso strato di grasso isolante rende loro impossibile dissipare il calore corporeo interno in acque tropicali.

In anni recenti, grazie ad alcuni studi genetici, si è scoperto che le popolazioni settentrionali e meridionali non si sono incrociate nel corso di un periodo che va dai 3 ai 12 milioni di anni, fatto che conferma la balena franca australe come una specie separata. Più sorprendente, poi, è stato scoprire che sono distinte tra loro anche le popolazioni pacifiche ed atlantiche dell'emisfero boreale e che la specie del Pacifico (nota ora come balena franca nordpacifica) è inoltre più strettamente imparentata con la balena franca australe che con la balena franca nordatlantica. Tuttavia Rice, nella sua classificazione del 1998, continuò a considerare solo due specie[3]; nel 2000, però, questa classificazione venne messa in discussione da Rosenbaum ed altri[4] e da Brownell ed altri (2001)[5]. Nel 2005, Mammal Species of the World riconobbe tre specie, indicando apparentemente una preferenza per quest'ultima suddivisione[6].

I pidocchi delle balene, crostacei ciamidi parassiti che vivono sulla pelle di questi animali, offrono ulteriori informazioni sulle popolazioni di balene franche Eubalaena tramite l'analisi del loro pattern genetico. Poiché i pidocchi si riproducono molto più velocemente delle balene, la loro diversità genetica è maggiore. I biologi marini dell'Università dello Utah hanno esaminato i geni di questi pidocchi ed hanno determinato che i loro padroni di casa si sono suddivisi in tre specie 5-6 milioni di anni fa e che queste specie erano tutte ugualmente abbondanti prima degli inizi della baleneria nell'XI secolo[7]. Queste comunità si suddivisero per la prima volta dopo la congiunzione del Nordamerica con il Sudamerica. In seguito il calore delle zone equatoriali le suddivise ulteriormente in gruppi settentrionali e meridionali. Jon Seger, il direttore di questi studi, su BBC News disse «Ciò pone fine al lungo dibattito su quante specie di balena franca [Eubalaena] esistano. Sono veramente separate tra loro oltre ogni dubbio»[1].

In seguito alla loro familiarità con i balenieri per un certo numero di secoli, alle balene franche sono stati dati molti nomi. Questi nomi vennero applicati alle balene franche di tutto il mondo, riflettendo il fatto che a quei tempi veniva riconosciuta solamente una sola specie. Nel romanzo Moby-Dick, Herman Melville scrisse: «Tra i pescatori, la balena regolarmente cacciata per l'olio viene indiscriminatamente chiamata con tutti i nomi seguenti: balena, balena della Groenlandia, balena nera, balena grande, balena vera, balena franca».

Halibalaena (Gray, 1873) ed Hunterius (Gray, 1866) sono sinonimi minori per indicare il genere Eubalaena. La specie tipo è E. australis.

I sinonimi, in ordine di tempo, per le varie specie sono:[6]

Le balene franche sono facilmente distinguibili dalle altre balene per le callosità presenti sulla testa, l'ampio dorso privo di pinna dorsale e la lunga bocca arcuata che inizia al di sopra dell'occhio. Il corpo è di color grigio molto scuro o nero, con alcune macchie bianche sul ventre presenti occasionalmente. Le callosità appaiono bianche, ma non a causa della pigmentazione della pelle, bensì per le grandi colonie di ciamidi o pidocchi delle balene.

Gli adulti misurano 11-18 m di lunghezza e pesano generalmente 60-80 tonnellate. La maggior parte degli esemplari, comunque, è lunga tra i 13 e i 16 m. Il corpo è estremamente robusto e in alcuni casi presenta una circonferenza pari al 60% della lunghezza totale. Anche la pinna caudale è molto larga (fino al 40% della lunghezza del corpo). Generalmente la specie nordpacifica è quella più grande tra le tre balene franche Eubalaena. Gli esemplari più grossi di questa specie raggiungono infatti le 100 tonnellate.

Su ogni lato della bocca le balene franche hanno tra i 200 e i 300 fanoni. Questi, lunghi circa 2 m, sono stretti e ricoperti da peli molto sottili. I fanoni permettono alla balena di nutrirsi (vedi oltre il capitolo Dieta). I testicoli della balena franca sono probabilmente quelli più grandi del regno animale, pesando ognuno circa 500 kg. Il loro peso, l'1% della massa corporea, è grande perfino tenendo conto delle dimensioni dell'animale. Ciò suggerisce che la competizione spermatica giochi un ruolo importante nei processi riproduttivi[8]. Le balene franche emettono un caratteristico soffio a forma di V, dovuto al notevole spazio situato tra i due sfiatatoi, posti sulla sommità del capo. Il soffio raggiunge un'altezza di 5 m sulla superficie dell'oceano[8].

Le femmine raggiungono la maturità sessuale tra i 6 e i 12 anni e si riproducono ogni 3-5 anni. Sia la riproduzione che il parto avvengono nei mesi invernali. Dopo un periodo di gestazione di 1 anno, nasce un solo piccolo del peso di circa 1,1 tonnellate di peso e di 4–6 m di lunghezza. Nel primo anno di vita i piccoli crescono molto rapidamente, raddoppiando in genere di lunghezza. Lo svezzamento avviene tra gli otto mesi e l'anno di età, ma quale sia il tasso di crescita negli anni successivi non è stato ancora ben compreso - forse è strettamente dipendente dal fatto che il piccolo rimanga o no in compagnia della madre per un secondo anno[9].

Sappiamo molto poco sulla speranza di vita delle balene franche, soprattutto a causa della scarsità degli scienziati che si sono interessati a questo argomento. Tra le poche prove a noi disponibili ricordiamo il caso di una madre di balena franca nordatlantica fotografata con il piccolo nel 1935 e poi ancora fotografata nel 1959, 1980, 1985 e 1992; per giudicare che si trattasse dello stesso animale veniva utilizzata la forma delle callosità. L'ultima volta che è stata fotografata, morta, nel 1995, presentava una ferita sulla testa apparentemente mortale, quasi sicuramente provocata dalla collisione con una nave. È stato stimato che avesse circa 70 anni. Ricerche effettuate sulle balene della Groenlandia suggeriscono che il raggiungere questa età sia piuttosto comune per le balene, che spesso la superano notevolmente[9][10].

Le balene franche sono nuotatrici lente, dal momento che raggiungono al massimo solamente una velocità di 5 nodi (9 km/h), ma sono molto acrobatiche e compiono con frequenza il breaching (effettuano, cioè, salti sulla superficie del mare), tail-slapping e lobtailing. Come altri misticeti, questa specie non è gregaria e un gruppo tipico è composto generalmente da solo due esemplari. Sono stati registrati anche gruppi di dodici individui, ma i vari membri non erano molto uniti tra di loro e la loro unione potrebbe essere anche stata solamente transitoria.

Gli unici predatori della balena franca sono le orche e gli esseri umani. Quando avverte un pericolo, un gruppo di questi animali si raggruppa in circolo, con le code rivolte all'esterno, per scoraggiare il possibile predatore. Questa strategia non ha però sempre successo e i piccoli vengono occasionalmente separati dalle madri e uccisi.

La dieta delle balene franche comprende principalmente zooplancton e minuscoli crostacei, come copepodi, krill e pteropodi, sebbene possano nutrirsi anche di altro. Si nutrono «mietendo» in lungo e in largo con la bocca spalancata. Dentro di essa entrano sia l'acqua che le prede, ma solo la prima riesce a fuoriuscire attraverso i fanoni per ritornare all'aperto. Stando così le cose, per permettere ad una balena di nutrirsi, le prede devono essere tanto numerose da suscitare il suo interesse; essere abbastanza grandi da poter permettere ai fanoni di filtrarle; ma anche abbastanza piccole da non avere la velocità per fuggire[9]. La «mietitura» può avvenire in superficie, sott'acqua, o perfino nei pressi del fondale dell'oceano, come indica il fango trovato occasionalmente sul corpo di alcune balene[9].

Rispetto a quelle di altre specie di balene le vocalizzazioni emesse dalle balene franche non sono molto elaborate. Emettono lamenti, schioppi e altri suoni, tutti con una frequenza intorno ai 500 Hz. Lo scopo di questi suoni non è noto, ma è probabile che costituiscano una forma di comunicazione tra i membri di uno stesso gruppo.

Da uno studio pubblicato sui Proceedings of the Royal Society B nel dicembre 2003 apprendiamo che le balene franche boreali rispondano rapidamente a suoni simili a quelli delle sirene della polizia - suoni dalla frequenza molto più alta di quelli emessi da questi animali. Non appena udivano questi suoni si spostavano rapidamente verso la superficie. Questa ricerca fu di particolare interesse, poiché è noto che le balene franche boreali ignorano la maggior parte dei suoni, compresi quelli delle imbarcazioni in avvicinamento. I ricercatori ipotizzano che le informazioni raccolte si rivelino utili nel tentativo di ridurre il numero di collisioni navi-balene, ma anche, purtroppo, che servano ad incoraggiare le balene a risalire in superficie per poterle uccidere[11].

Le balene franche vennero chiamate così poiché i balenieri le ritenevano le balene "giuste" da cacciare. Il 40% del peso di una balena franca è costituito da grasso, che ha una densità relativamente bassa. Di conseguenza, diversamente da molte altre specie di balene, gli esemplari morti galleggiano. Questa caratteristica, combinata alla loro lentezza, le rendeva facili da catturare perfino da balenieri equipaggiati solamente con imbarcazioni di legno e arpioni a mano.

I Baschi furono i primi a cacciare balene franche a scopo commerciale. Ciò avvenne nell'XI secolo nella Baia di Biscaglia. Le balene vennero cacciate inizialmente per il loro olio ma, in seguito ai miglioramenti tecnologici nella conservazione della carne, questi animali vennero utilizzati anche come fonte di cibo. I balenieri baschi si spinsero fino al Canada orientale a partire dal 1530[9] e alle coste della baia di Todos os Santos (stato di Bahia, in Brasile) dal 1602. Le ultime spedizioni basche a caccia di balene vennero effettuate prima dell'inizio della Guerra dei Sette Anni (1756-1763). In seguito vennero effettuati alcuni tentativi per riportare in voga questa caccia, tutti falliti. La baleneria sulle coste basche continuò sporadicamente nel corso del XIX secolo.

I Baschi vennero rimpiazzati dai balenieri delle nuove colonie americane: i «balenieri yankee». Partendo da Nantucket, nel Massachusetts, e da Long Island, nello stato di New York, gli americani furono in grado di catturare in annate favorevoli fino a 100 balene franche. A partire dal 1750 la balena franca nordatlantica si estinse da un punto di vista commerciale ed i balenieri yankee si spostarono nell'Atlantico meridionale prima della fine del XVIII secolo. La stazione baleniera brasiliana più meridionale venne fondata nel 1796, a Imbituba. Nel corso dei cento anni successivi, i balenieri yankee si spinsero nell'Oceano Meridionale e nel Pacifico, dove gli americani furono ben presto raggiunti dalle flotte provenienti da alcune nazioni europee. Gli inizi del XX secolo portarono grandi miglioramenti nell'industrializzazione della baleneria, che crebbe rapidamente. Dal 1937 in poi vi furono, secondo i dati raccolti dai balenieri, 38.000 catture nell'Atlantico meridionale, 39.000 nel Pacifico meridionale, 1300 nell'Oceano Indiano e 15.000 nel Pacifico settentrionale. Data l'incompletezza di questi dati, si ritiene che questi numeri siano perfino più alti[12].

Quando divenne chiaro che i branchi erano stati quasi distrutti, nel 1937 venne emesso un bando globale alla caccia alle balene franche. Il bando venne per la maggior parte rispettato, sebbene alcuni balenieri continuarono a violarlo per alcuni decenni. Le ultime due catture a Madera avvennero nel 1968. Tra gli anni '40 e quelli '60 i giapponesi, a scopo scientifico, catturarono 23 balene franche nordpacifiche. Al largo delle coste del Brasile la caccia illegale continuò per molti anni e i balenieri di Imbituba smisero di cacciare balene franche solo nel 1973. Da poco è stato scoperto che durante gli anni '50 e '60 l'Unione Sovietica abbia catturato illegalmente almeno 3212 balene franche australi, nonostante avesse sostenuto per anni di averne uccise solo 4[13].

I ricercatori hanno utilizzato i dati riguardanti le femmine adulte ottenuti in seguito a tre censimenti (in Argentina, Sudafrica e Australia, svoltisi tutti nel corso degli anni '90) e li hanno estrapolati per farvi includere anche le balene delle aree non comprese, oltre ai maschi e ai piccoli, contati sulla base del rapporto maschio:femmina e adulti:piccoli. Dopo questo lavoro, nel 1999, è stato finalmente espresso che vi siano 7000 animali. Ulteriori informazioni possono essere trovate sull'edizione del maggio 1998 di «Right Whale News» disponibile online (archiviato dall'url originale il 12 marzo 2007)..

Attualmente, le tre specie di Eubalaena vivono in tre distinte aree del globo: quella nordatlantica nell'Oceano Atlantico occidentale, quella nordpacifica in una fascia di mare che va dal Giappone all'Alaska e quella australe in ogni zona dell'Oceano Meridionale. Queste balene tollerano solamente le temperature moderate delle acque comprese tra i 20 e i 60 gradi di latitudine. Le acque calde della regione equatoriale costituiscono quindi per loro una barriera, e impediscono che i gruppi boreali e australi si incrocino tra loro. Nonostante la specie australe in particolare debba viaggiare molto in oceano aperto per raggiungere le sue zone di riproduzione, non è considerata una specie pelagica. In generale, preferisce rimanere nei pressi delle penisole e delle baie e sulla piattaforma continentale, dal momento che queste aree le offrono una maggior protezione e abbondanza delle sue fonti di cibo preferite.

Vi sono circa 400 balene franche nordatlantiche, delle quali quasi tutte vivono nell'Oceano Atlantico nord-occidentale. In primavera, estate e autunno, si nutrono nelle aree al largo delle coste canadesi e di quelle nord-orientali degli USA, in un areale che va da New York alla Nuova Scozia. Aree di foraggiamento particolarmente popolari sono la Baia di Fundy e quella di Cape Cod. In inverno, si dirigono a sud, verso la Georgia e la Florida, per partorire.

In questi ultimi decenni vi sono stati anche avvistamenti in zone situate più a est - l'ultimo, nel 2003, è avvenuto nei pressi dell'Islanda. È possibile che gli esemplari avvistati siano gli ultimi resti dei virtualmente estinti branchi dell'Atlantico orientale, ma l'analisi dei vecchi resoconti dei balenieri fa pensare soprattutto ad una provenienza occidentale[9]. Comunque, alcuni avvistamenti avvengono piuttosto regolarmente in Norvegia, Irlanda, Spagna, Portogallo, Isole Canarie e perfino in Sicilia[14], e sappiamo con certezza che almeno gli individui avvistati in Norvegia provengono dalla popolazione occidentale[15].

Sopravvivono solamente circa 200 balene franche nordpacifiche[1]. Le due specie boreali di balena franca sono perciò le specie più minacciate tra tutte le grandi balene e due tra gli animali più minacciati del mondo. Sulla base dell'attuale andamento della densità di popolazione, si ritiene che entrambe le specie si estingueranno entro 200 anni[11]. In tempi storici la specie pacifica era diffusa dall'estremità meridionale del Giappone alla California, attraverso lo Stretto di Bering e le coste del Nordamerica. Oggi, i suoi avvistamenti sono molto rari e avvengono generalmente all'ingresso del Mare di Okhotsk e nelle zone orientali del Mare di Bering. Sebbene si ritenga che questa specie, come le altre due, sia migratrice, i suoi movimenti annuali non sono conosciuti.

Le balene franche australi trascorrono i mesi estivi nutrendosi nelle regioni più meridionali dell'Oceano Meridionale, probabilmente nei pressi dell'Antartide. In inverno migrano a nord per riprodursi e possono essere avvistate lungo le coste di Argentina, Australia, Brasile, Cile, Mozambico, Nuova Zelanda e Sudafrica. La sua popolazione totale è stimata tra i sette e gli ottomila esemplari. Da quando la caccia a questa specie è cessata, si stima che ogni anno i branchi si siano accresciuti del 7%. Sembra che i gruppi sudamericani, sudafricani e australasiani si incrocino molto poco tra loro, se non per niente, poiché l'attaccamento delle madri alle loro zone di foraggiamento e riproduzione è molto stretto. Inoltre, le madri trasmettono questo istinto ai piccoli[9].

In Brasile, tramite identificazione fotografica (utilizzando le caratteristiche callosità sulla testa), gli uomini del Brazilian Right Whale Project, sostenuti dalla Petrobras (la compagnia petrolifera statale brasiliana) e dall'International Wildlife Coalition, hanno catalogato più di 300 individui. Al largo dello Stato di Santa Catarina vi sono zone di foraggiamento utilizzate da molte balene franche tra giugno e novembre; è noto che le femmine di questa popolazione partoriscono al largo della Patagonia argentina.

La principale causa di morte tra le balene franche nordatlantiche, le quali, migrando al largo della costa orientale degli Stati Uniti e del Canada, attraversano una tra le zone più trafficate dell'oceano, sono le ferite provocate dalle collisioni con le navi[16]. Tra il 1970 e il 1999 sono morte in questo modo almeno 16 balene; inoltre, dato che non tutte le collisioni vengono registrate, è probabile che questo numero sia ancora più elevato[9]. Riconoscendo che questo prezzo da pagare sia troppo elevato per una specie già avviata verso l'estinzione, il governo degli Stati Uniti ha introdotto alcune misure per ostacolarne il declino. Nel 1997 la National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration ha introdotto l'Atlantic Large Whale Take Reduction Plan[17]. Secondo questo progetto, l'equipaggio di ogni nave che si serve dei porti statunitensi è obbligato a dichiarare ogni avvistamento di queste balene. Questo requisito è stato reso obbligatorio nel luglio 1999.

Sebbene nel 2001 gli ambientalisti abbiano dichiarato con gioia le conseguenze positive di questo piano, essi speravano che il governo facesse di più[18]. In particolare chiedevano che le navi che si trovano entro una distanza di 40 km dai porti USA, nelle zone transitate dalle balene, fossero obbligate a mantenere una velocità di non più di 12 nodi (22 km/h). Il governo degli Stati Uniti, temendo danni eccessivi per il commercio, non ha fatto applicare queste misure. Di conseguenza, nel settembre 2005, i gruppi conservativi Defenders of Wildlife, Humane Society of the United States e Ocean Conservancy hanno chiesto al National Marine Fisheries Service (una sotto-agenzia della NOAA) di «interessarsi alla protezione della criticamente minacciata balena franca nordatlantica, che l'agenzia stessa considera "la più rara tra tutte le specie di grandi balene" e che le agenzie federali sono obbligate a proteggere secondo il Marine Mammal Protection Act e l'Endangered Species Act», e di mettere in pratica misure d'emergenza per proteggere questi animali[19]. Sia la specie nordatlantica che quella nordpacifica sono classificate come «specie in estinzione minacciate dal commercio» (Appendice I) dalla CITES, mentre secondo la Lista Rossa della IUCN sono «dipendenti dalla conservazioni» e per l'Endangered Species Act degli USA sono minacciate.

Il secondo fattore di morbilità e mortalità per le balene franche nordatlantiche è l'intrappolamento nelle reti da pesca. Le balene franche filtrano il plancton tenendo la bocca aperta, fatto che le espone al rischio di rimanere impigliate in ogni fune o rete che si trovano davanti. Generalmente le funi si attorcigliano attorno alla mascella superiore, alle natatoie e alla coda. La maggior parte di loro riesce a fuggire senza gravi danni, ma alcune rimangono gravemente e persistentemente impigliate. Se vengono avvistate, talvolta si riesce a liberarle con successo, ma se ciò non accade, muoiono in modo orrendo dopo qualche mese. Essendo una specie minacciata, lo stato di conservazione delle balene franche suscita particolare attenzione. Tuttavia, altrettanto significativa è l'estrema preoccupazione che suscitano le condizioni degli animali rimasti intrappolati in questo modo.

La balena franca australe, classificata come «minacciata» dalla CITES e a «rischio minimo - dipendente dalla conservazione» dalla IUCN, è protetta nelle acque territoriali di tutti i Paesi in cui sono presenti popolazioni riproduttive note (Argentina, Australia, Brasile, Cile, Nuova Zelanda, Sudafrica e Uruguay). In Brasile, allo scopo di proteggere la specie e di promuovere il whale watching, nel 2000 è stata istituita un'Area per la Protezione Ambientale che comprende 1560 km² e 130 km di costa dello Stato di Santa Catarina[20].

Il 26 giugno 2006, la NOAA ha proposto la Strategia per Ridurre gli Scontri delle Balene Franche Nordatlantiche con le Navi[21]. Questa proposta, ostacolata dall'industria navale, prevede di imporre una velocità di 10 nodi (18,5 km all'ora) alle navi più lunghe di 20 m che attraversano le rotte seguite dalle balene durante la stagione delle nascite. Comunque, questa proposta non è stata ancora accolta. Secondo la NOAA, 25 delle 71 balene franche morte a partire dal 1970 sono state uccise da scontri con le navi.

Nell'area del Banco di Stellwagen è stato impiantato un sistema autogalleggiante (AB) per scoraggiare acusticamente le balene che si avvicinano a Boston; questo sistema, inoltre, è in grado di avvisare i marinai della direzione presa da questi animali tramite il sito Right Whale Listening Network (archiviato dall'url originale il 1º giugno 2008)..

Le balene franche australi hanno fatto di Hermanus, in Sudafrica, uno dei più importanti centri mondiali di whale watching. Durante i mesi invernali (giugno-ottobre), queste balene si avvicinano così tanto alla costa che i visitatori le possono osservare da alberghi situati in luoghi strategici. In questa città è presente uno strillone che percorre le strade annunciando quando poter vedere i Cetacei. Comunque, le balene franche australi si possono vedere anche in altre zone dei territori invernali.

In Brasile, Imbituba, nel Santa Catarina, è stata designata come la Capitale Nazionale della Balena Franca e ogni settembre, quando le madri con i piccoli sono più facilmente avvistabili, vi si festeggia la Settimana delle Balene Franche. La vecchia stazione baleniera è stata riconvertita in un museo che documenta la storia delle balene franche in Brasile. In Argentina, la Penisola di Valdés, in Patagonia, ospita (d'inverno) la più numerosa popolazione riproduttrice di tutta la specie, con oltre 2000 animali catalogati dalla Whale Conservation Institute e dalla Ocean Alliance[22].

Eubalaena è un genere di cetacei misticeti cui appartengono tre specie, note comunemente come balene franche.

Talvolta l'intera famiglia dei Balenidi viene indicata come la famiglia delle balene franche. Anche la balena della Groenlandia, unica specie del genere Balaena, appartiene a questa famiglia, e viene pertanto considerata anch'essa una balena franca. Comunque, in quest'articolo parleremo solo delle specie di Eubalaena.

Le balene franche possono raggiungere una lunghezza di 18 m e pesare fino a 70 tonnellate. Il loro corpo rotondeggiante è quasi completamente nero e sulla testa presenta caratteristiche callosità (zone di pelle ruvida). Vengono chiamate «balene franche» poiché i balenieri le ritenevano le balene «giuste» da cacciare, dal momento che galleggiano una volta uccise e spesso nuotano nei pressi della costa, rendendole individuabili perfino da riva. Il loro numero è stato enormemente ridotto a causa dei grandi massacri perpetrati durante i floridi anni dell'industria baleniera. Oggi, invece di cacciarle, le persone spesso osservano questi animali acrobatici per puro piacere.

Le tre specie di Eubalaena vivono in località distinte. Tra queste: