en

names in breadcrumbs

As a result of high predation rates, especially of eggs and young, red-winged blackbirds have developed a number of anti-predator adaptations. Group nesting is one such trait which reduces the risk of individual predation by increasing the number of alert parents. Nesting over water reduces the likelihood of predation as do alarm calls. Nests, in particular, offer a strategic advantage over predators in that they are often well concealed in thick, waterside reeds and positioned at a height of one to two meters. Males often act as sentinels, employing a variety of calls to denote the kind and severity of danger. Mobbing, especially by males, is also used to scare off unwanted predators, although mobbing often targets large animals and man-made devices by mistake. The brownish coloration of the female may also serve as an anti-predator trait in that it may provide camouflage for her and her nest (while she is incubating).

Known predators include: racoons, American mink, black-billed magpies, marsh wrens, owls (family Strigidae) and hawks (order Falconiformes).

Known Predators:

Anti-predator Adaptations: aposematic ; cryptic

Despite their consumption of the seeds of unwanted weed pests, red-wing blackbirds have been known to cause great agricultural damage due to their colonial roosting habits and taste for agricultural products. Red-winged blackbirds often open the husks of developing corn stalks to feed on corn kernels. They are also known to feed on rice paddies and sunflower seeds. This consumption of ripening crops has lead many agriculturalists to employ extremely effective and often inhumane tactics in battling red-winged blackbird populations. These tactics include the frequent use of traps, poisons, and Avitol, a chemical agent that causes birds to behave in abnormal ways. Surfactants, or wetting agents, have also caused considerable damage to red-winged blackbirds. These detergents break down the waterproofing properties of the blackbird's feathers making them extremely vulnerable to low temperatures. Because of the long history of human-blackbird conflict and their continued threat to agricultural initiatives many of these techniques are used to this day. Less harmful methods of red-winged blackbird control include the use of noisemakers and the reduction of post-harvest crop waste, which attracts hungry red-winged blackbirds to farmland.

Negative Impacts: crop pest

Red-winged blackbirds have been known to feed on the seeds of numerous weeds that are detrimental to agricultural production. They also control insect populations, which can devastate agricultural yields.

Positive Impacts: controls pest population

As highly generalized foragers and predators, red-winged blackbirds can have a great and lasting impact on their environment. By controlling insect populations through predation and weed populations through the consumption of seeds, red-winged blackbirds allow larger plants and crops to flourish. Paradoxically, red-winged blackbirds can also devastate plant growth and crop yields by feeding on the very plants their predation protects. As one of the most numerous species of birds on the continent, red-winged blackbirds also play key roles in the dispersal of other species. Because red-winged blackbirds tend to flock and roost in such large numbers the survival of other species of birds that encroach upon their territory must surely be affected by their presence. Large roosting habitats can also greatly affect the physical terrain. In short, red-winged blackbirds are so numerous and active that their presence and natural behavior alone is enough to impact an ecosystem in a very visible way.

Ecosystem Impact: disperses seeds

Red-winged blackbirds tend to be generalized feeders, consuming a greater amount of plant tissue in the non-breeding season and a greater amount of animal material in the breeding season. Red-winged blackbirds will feed on almost any plant material they can consume, preferring seeds and agricultural products, such as corn and rice. Adult red-winged blackbirds will consume a wide variety of foods including snails, frogs, fledgling birds, eggs, carrion, worms and a wide array of arthropods. Insects, especially Odonata (dragonflies and damselflies), Lepidoptera (butterflies and moths), and Diptera (true flies) are preferred, although arachnids and other insect and non-insect arthropods are consumed. For the most part, red-winged blackbirds feed on whatever they can find, picking insects out of plants and feeding on seeds and plant material. At times, red-winged blackbirds will hunt using their beaks for gaping (opening up of crevices in plant material with the beak). Red-winged blackbirds will also catch insects in flight.

Animal Foods: birds; amphibians; reptiles; eggs; carrion ; insects; terrestrial non-insect arthropods; terrestrial worms

Plant Foods: roots and tubers; wood, bark, or stems; seeds, grains, and nuts

Primary Diet: omnivore

As one of the most common, widespread, and numerous birds in North America, little is done to protect red-winged blackbirds from the effects of habitat loss and urbanization. Because they can survive in a wide array of habitats, many populations can overcome losses of natural terrain. Nonetheless, red-winged blackbirds thrive in wetland areas and with the loss of natural wetlands it is likely that this species will suffer. This species is a migratory bird, and is protected under the U.S. Migratory Bird Treaty Act.

US Migratory Bird Act: protected

US Federal List: no special status

CITES: no special status

State of Michigan List: no special status

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: least concern

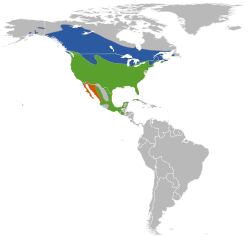

The range of red-winged blackbirds extends from southern Alaska at its northern most point, to the Yucatan peninsula in the south and covers the greater part of the continent reaching from the Pacific coast of California and Canada to the eastern seaboard. Winter ranges for red-winged blackbirds vary by geographic location. Northern populations migrate south to the southern United States and Central America beginning in September or October (or occasionally as early as August). Most western and middle American populations are non-migratory.

Biogeographic Regions: nearctic (Native ); neotropical (Native )

Red-winged blackbirds roost and breed in a variety of habitats, but tend to prefer wetlands. They have been known to live in fresh and saltwater marshes. On drier ground, red-winged blackbirds gravitate towards open fields (often in agricultural areas) and lightly wooded deciduous forests. In winter red-winged blackbirds are most often found in open fields and croplands.

Habitat Regions: temperate ; tropical ; terrestrial

Terrestrial Biomes: savanna or grassland

Aquatic Biomes: brackish water

Wetlands: marsh ; swamp

Other Habitat Features: suburban ; agricultural ; riparian ; estuarine

In the wild, red-winged blackbirds live 2.14 years, on average. The olded recorded red-winged blackbird in the wild lived 15 years and 9 months.

Range lifespan

Status: wild: 20 (high) years.

Average lifespan

Status: wild: 2.14 years.

Average lifespan

Status: wild: 189 months.

Easily distinguished by their glossy black feathers and red and yellow epaulets at the shoulder, males are the more brightly colored of the two sexes. Females tend to be dusty or brownish in color with dark stripes on their undersides. Females resemble large sparrows and are often recognized by their off-white eyebrow markings. Both males and females have dark legs and claws. The beak of male red-winged blackbirds tends to be totally black, whereas the beak of female red-winged blackbirds is dark brown on top with lighter brown on the underside. Both males and females have sharply pointed beaks.

Both male and female adult red-winged blackbirds are approximately 22 cm long, weigh 41.6 to 70.5 g and have a wingspan of 30 to 37 cm. Young males and females resemble adult females in coloration. Males undergo a transitional stage in which red epaulets appear orange in color before reaching their adult coloration. Olson (1994) showed that the average basal metabolic rate for adults in his experiments was 656 cm cubed/oxygen per minute and that the rate for three-day-old birds was 296 cm cubed/oxygen per minute.

Range mass: 41.6 to 70.5 g.

Range length: 18 to 24 cm.

Average length: 22 cm.

Range wingspan: 30 to 37 cm.

Other Physical Features: endothermic ; homoiothermic; bilateral symmetry

Sexual Dimorphism: male larger; sexes colored or patterned differently; male more colorful

Males learn songs from other males. Both males and females have a variety of calls, some of which are the same. Only the males produce flight calls, which signal their exit from the territory. Both males and females employ distress and alarm calls which differ with the nature of the threat. Specific calls seem to communicate the presence of specific predators, such as raccoons or American crows. Short contact calls are also quite common, especially between a territorial male and the females in his territory. Threat calls are used to ward off predators, other birds and other red-winged blackbirds. Courtship calls vary little between males and females and are used only in the breeding season. Male songs are used to announce territorial boundaries and to attract mates. Female songs occur in the early breeding season and are most common before the incubation period.

Male red-winged blackbirds utter their familiar territorial and mate attraction song of "oak-a-lee" or "konkeree" in the spring. The last syllable is given more emphasis as a scratchy or buzzy trill. The common call used by both males and females is a "check" call. Males may utter a whistled "cheer" or "peet" call if alarmed. Other calls made by the male include a "seet," a "chuck," or a "cut." Females may utter a short chatter or sharp scream. A pre-mating call, "ti-ti-ti," may be uttered by both sexes.

Visual displays are also a key form of communication, especial before and during mating. Males often use visual displays in order to attract females to their territories and to defend their territories and mates. An example is the "song spread" display. Males fluff their plumage, raise their shoulders, and spread their tail as they sing. As the display becomes more intense, the wings are more arched with the shoulders showing more prominently. Females will also engage in a "song spread" display directed at each other early in the breeding season. One possibility is that a female will defend a sub-territory within the male's territory. Females will engage in a "wing flip" display when a disturbance prevents them from returning to the nest.

Communication Channels: visual ; acoustic

Perception Channels: visual ; tactile ; acoustic ; chemical

Red-winged blackbirds are extremely polygynous with as many as 15 females nesting in the territory of a single male. On average, a single male has roughly 5 females. Although copulation occurs mostly between the sovereign male and those females that inhabit his territory, roaming males are known to mate with the females on other territories. These behaviors seem to increase the chances of successful reproduction within a given mating season, compensating for broods and individuals lost to nest-predation and nest parasitism.

Mating rituals begin with the song of the male. Females often do not return songs until they have established themselves in the territory of a male. Male pre-coital displays include vocalization in a crouched position with rapid and highly conspicuous fluttering of the wings. The female responds with a similar crouch and vocalization. Mating occurs in the egg-laying period or just prior and is characterized by a brief contact between the cloacal vents of the male and the female.

Mating System: polygynous ; polygynandrous (promiscuous)

Breeding begins in the early spring and continues until mid-summer. Females may raise as many as three broods in a single season, although the average is 1.7 broods per season. Females choose nesting sites most often in wetland or agricultural areas (although a wide variety of nesting habitats are know to be exploited) and males perform a nesting display, which constitutes his main involvement in the nest building process. Nest building begins between March and May. Usually, the further south you go, the earlier the nest is built. After a female accepts the male and his site, the nest is built in or near marshland or moist, grassy areas. Plant materials, such as cattail stalks, are woven together to form a basket above water level, and soft materials are used to line the nest. Three to five pale greenish-blue, black or purple streaked eggs are laid per clutch. Each egg is approximately 2.5 by 1.8 cm. Nests can be completed in as little as a single day, especially if no mud-lining is constructed.

Clutch size is from 3 to 7 eggs and the eggs are incubated for 3 to 11 days. Chicks fledge in 10 to 14 days and are independent in 2 to 3 weeks. Juveniles usually reach sexual maturity in 2 to 3 years.

Breeding interval: Females may raise as many as three broods in a single season, although the average is 1.7 broods per season.

Breeding season: Breeding begins in the early spring and continues until mid-summer.

Range eggs per season: 3 to 7.

Average eggs per season: 4.

Range time to hatching: 11 to 13 days.

Average time to hatching: 11 days.

Range fledging age: 14 to 10 days.

Average fledging age: 14 days.

Range time to independence: 2 to 3 weeks.

Average time to independence: 2 weeks.

Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female): 2 to 2 years.

Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male): 2 to 4 years.

Key Reproductive Features: iteroparous ; seasonal breeding ; gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); sexual ; fertilization ; oviparous

Average eggs per season: 4.

Incubation is the sole responsibility of females. Red-winged blackbird eggs tend to hatch at different times and the mother will continue to incubate until the last egg has hatched. Nestlings are fed almost immediately after hatching. Parents often begin with smaller portions and increase food amounts progressively. Young red-winged blackbirds are fed small arthropods, especially Odonata (dragonflies and damselflies), Lepidoptera (moths and butterflies), and Diptera (true flies). The nestlings are fed primarily by the female although the male will, at times, take part in the feeding process. In cases in which the mother is absent, males are known to take over feeding responsibilities for the brood. Fledglings leave the nest after 14 days and are fed by the female and, to a lesser degree, the male for two to three weeks before joining a flock of females. Within a year most red-winged blackbirds have joined mixed flocks.

Parental Investment: no parental involvement; altricial ; pre-fertilization (Protecting: Female); pre-hatching/birth (Protecting: Female); pre-weaning/fledging (Provisioning: Male, Female, Protecting: Male, Female); pre-independence (Provisioning: Male, Female, Protecting: Male, Female)

A small (7-9 ½ inches) blackbird, the male Red-winged Blackbird is most easily identified by its small size, black body, and red-and-yellow “shoulder” patches visible as part of the male’s display. Female Red-winged Blackbirds are streaked brown overall with faint tan eye-stripes. Males are unmistakable when their bright patches are visible, and no other female blackbird in North America is so heavily streaked. The Red-winged Blackbird breeds primarily from Alaska and northwestern Canada south to northern Central America. In winter, northerly-breeding populations migrate south to the southern U.S. Populations breeding further south are generally non-migratory. Red-winged Blackbirds breed in wetland habitats, including freshwater and saltwater marshes, damp grasslands, and flooded fields where rice is grown. Birds that migrate utilize similar habitats in the winter as in summer. Red-winged Blackbirds primarily eat insects during the summer, switching to a diet composed of seeds and grains in the winter. In appropriate habitat, Red-winged Blackbirds are most easily seen while foraging for food on the stalks and leaves of marsh grasses. During the breeding season, males may be observed displaying their “shoulder” patches from prominent perches in the grass while singing this species’ buzzing “konk-la-ree” song. Red-winged Blackbirds are primarily active during the day.

A small (7-9 ½ inches) blackbird, the male Red-winged Blackbird is most easily identified by its small size, black body, and red-and-yellow “shoulder” patches visible as part of the male’s display. Female Red-winged Blackbirds are streaked brown overall with faint tan eye-stripes. Males are unmistakable when their bright patches are visible, and no other female blackbird in North America is so heavily streaked. The Red-winged Blackbird breeds primarily from Alaska and northwestern Canada south to northern Central America. In winter, northerly-breeding populations migrate south to the southern U.S. Populations breeding further south are generally non-migratory. Red-winged Blackbirds breed in wetland habitats, including freshwater and saltwater marshes, damp grasslands, and flooded fields where rice is grown. Birds that migrate utilize similar habitats in the winter as in summer. Red-winged Blackbirds primarily eat insects during the summer, switching to a diet composed of seeds and grains in the winter. In appropriate habitat, Red-winged Blackbirds are most easily seen while foraging for food on the stalks and leaves of marsh grasses. During the breeding season, males may be observed displaying their “shoulder” patches from prominent perches in the grass while singing this species’ buzzing “konk-la-ree” song. Red-winged Blackbirds are primarily active during the day.

La merla ala-roja[1] (Agelaius phoeniceus) és un ocell de la família dels ictèrids (Icteridae) que habita zones palustres i terres de conreu d'Amèrica del Nord i Central, des de l'est d'Alaska cap al sud, a través de Canadà, Estats Units i Mèxic fins al nord de Costa Rica i les Bahames.

La merla ala-roja (Agelaius phoeniceus) és un ocell de la família dels ictèrids (Icteridae) que habita zones palustres i terres de conreu d'Amèrica del Nord i Central, des de l'est d'Alaska cap al sud, a través de Canadà, Estats Units i Mèxic fins al nord de Costa Rica i les Bahames.

Aderyn a rhywogaeth o adar yw Tresglen adeingoch (sy'n enw benywaidd; enw lluosog: tresglod adeingoch) a adnabyddir hefyd gyda'i enw gwyddonol Agelaius phoeniceus; yr enw Saesneg arno yw Red-winged blackbird. Mae'n perthyn i deulu'r Tresglod (Lladin: Icteridae) sydd yn urdd y Passeriformes.[1]

Talfyrir yr enw Lladin yn aml yn A. phoeniceus, sef enw'r rhywogaeth.[2] Mae'r rhywogaeth hon i'w chanfod yng Ngogledd America.

Mae'r tresglen adeingoch yn perthyn i deulu'r Tresglod (Lladin: Icteridae). Dyma rai o aelodau eraill y teulu:

Rhestr Wicidata:

rhywogaeth enw tacson delwedd Casig Para Psarocolius bifasciatus Gregl y Gorllewin Quiscalus nigerAderyn a rhywogaeth o adar yw Tresglen adeingoch (sy'n enw benywaidd; enw lluosog: tresglod adeingoch) a adnabyddir hefyd gyda'i enw gwyddonol Agelaius phoeniceus; yr enw Saesneg arno yw Red-winged blackbird. Mae'n perthyn i deulu'r Tresglod (Lladin: Icteridae) sydd yn urdd y Passeriformes.

Talfyrir yr enw Lladin yn aml yn A. phoeniceus, sef enw'r rhywogaeth. Mae'r rhywogaeth hon i'w chanfod yng Ngogledd America.

Vlhovec červenokřídlý (Agelaius phoeniceus) je středně velký druh pěvce z čeledi vlhovcovitých (Icteridae).

Samice dorůstají 17–18 cm a váží 36 g, samci jsou 22–24 cm dlouzí a jejich průměrná hmotnost činí 64 g.[2]

Je sexuálně dimorfní; samci jsou celí černí s velkou červenou skvrnou na křídlech, z jedné strany ohraničenou silným žlutým pruhem. Samice jsou převážně hnědé se světlou, hustě černě pruhovanou spodinou těla.

Vlhovec červenokřídlý je široce rozšířen na většině severoamerického kontinentu. Hnízdí v rozmezí od Aljašky a Newfoundlandu jižně až po Floridu, Mexiko a Guatemalu, izolované populace se vyskytují také na západě El Salvadoru, na severozápadě Hondurasu a v severozápadní Kostarice. Severní populace jsou tažné se zimovišti na jihu Spojených států a v Mexiku, zatímco ptáci ze západní části severoamerického kontinentu a ze Střední Ameriky na svých hnízdištích setrvávají po celý rok. Obývá otevřené travnaté krajiny. Preferuje přitom mokřiny, a to jak se sladkou, tak i se slanou vodou. Dále se vyskytuje také v suchých náhorních oblastech, kde obývá louky, prérie a neudržovaná pole.[3]

Vlhovec červenokřídlý bývá při obraně svého teritoria velmi agresivní. Dokáže přitom napadnout i mnohem větší ptáky, než je on sám, např. vrány, havrany, straky, dravce či volavky.[4]

Je všežravý. Živí se zejména semeny a hmyzem, ale požírá také žáby, ptačí vejce, mršiny, červy, pavouky a měkkýše.[5]

Je polygamní, jeden samec obhajuje teritorium až s 10 samicemi. Na 3-6 denní stavbě miskovitého hnízda z travin a mechu, zpevněného hlínou a připevněného nejčastěji k rákosovým stéblům, se podílí samotná samice. V jedné snůšce bývají 3-4, zřídka i 5 zeleno-modrých, tmavě skvrnitých vajec. Na jejich 11-12 denní inkubaci se opět podílí pouze samice. Mláďata se líhnou slepá a neopeřená a hnízdo opouští po 11-14 dnech.[2]

V tomto článku byl použit překlad textu z článku Red-winged Blackbird na anglické Wikipedii.

Vlhovec červenokřídlý (Agelaius phoeniceus) je středně velký druh pěvce z čeledi vlhovcovitých (Icteridae).

Der Rotflügelstärling (Agelaius phoeniceus), früher auch rotschulteriger Star oder Sumpfhordenvogel genannt[1], ist ein Vogel aus der Familie der Stärlinge (Icteridae). Er ist einer der bestuntersuchten Singvögel in Nordamerika.

Die erste Zeichnung eines Rotflügelstärlings wurde von Mark Catesby angefertigt. Anhand seiner Zeichnung beschrieb Carl von Linné 1766 den Vogel wissenschaftlich.

Das Männchen hat ein unverwechselbares schwarzes Gefieder mit roten Flügelflecken, die von kleinen gelben oder weißen Streifen eingefasst sind. Das Weibchen und die Jungvögel haben ein gestreiftes, schwarzbraunes bis braunes Gefieder. Die Körpergröße beträgt zwischen 18 und 24 Zentimeter bei einer Flügelspannweite von 30 bis 37 Zentimeter. Der Schnabel ist spitz und scharf und an den kräftigen Beinen befinden sich an den Füßen vier Zehen; eine nach hinten und drei nach vorne. Der Geruchssinn ist schwach entwickelt, jedoch sehen und hören sie gut. Durch Markierung wilder Rotflügelstärlinge mit einem Band wurde ein Höchstalter von 15 Jahren und 9 Monaten festgestellt.

Charakteristisch ist der ständige trillernde Ruf des Männchens. Beim Singen spreizt das Männchen die Flügel und stellt die roten Flügelflecken zur Schau, um seinen Territorialanspruch gegenüber anderen Männchen oder dem stilleren Weibchen geltend zu machen. Mit seinen Rufen lockt er während der Paarungszeit auch die Weibchen an.

Der Rotflügelstärling ernährt sich im Sommer von Spinnen, Samen, Körner, Käfern, Schmetterlingen und anderen Insekten. Auch von Früchten wie Blaubeeren und Brombeeren. Die Insekten werden in der Luft gefangen oder am Boden. Im Winter ernähren sie sich überwiegend von Samen und Körnern. Sehr gerne werden reife Sonnenblumenkerne gefressen.

Bei den Rotflügelstärlingen gibt es keine festen Partnerschaften. Während die Männchen normalerweise einige Jahre hintereinander dieselbe Gegend aufsuchen, wechseln die Weibchen jedes Jahr das Brutgebiet. Die Fortpflanzung findet zwischen Februar und August statt. Nachdem die Männchen in den Brutgebieten eingetroffen sind, sucht sich jedes ein eigenes Brutrevier. Nach etwa zehn Tagen treffen die Weibchen in den Brutgebieten ein.

Die tiefen Nester bestehen aus Gräsern, Sumpfgras oder Schilf und werden alleine vom Weibchen über Wasser im Sumpfgras oder in Büschen erbaut. Das Männchen beteiligt sich weder am Nestbau noch am Ausbrüten der Eier. In das beutelförmige Nest werden vier bis fünf hellblaue, braun gefleckte Eier gelegt. Nach etwa 12 Tagen schlüpfen die blinden und nackten Jungen. Beide Altvögel beteiligen sich an der Aufzucht der Jungen. Die Küken werden am Anfang mit Insekten gefüttert. Im späteren Verlauf werden von den Altvögeln Körner gereicht. Mit 14 Tagen sind die Jungen flügge.

In einer Brutperiode werden zwei- bis dreimal Junge aufgezogen. Für jedes Gelege wird ein neues Nest gebaut.

Der Rotflügelstärling wird unter anderem von Füchsen, Eulen oder Habichten gejagt. Die Jungvögel und Eier werden von Würgern und Krähen erbeutet. Im Wasser lauern Wasserschlangen, Fische und Frösche auf herabfallende Jungvögel. Im nordwestlichen Verbreitungsgebiet wird der Rotflügelstärling häufig von dem größeren Gelbkopf-Schwarzstärling (Xanthocephalus xanthocephalus) in der Brutzeit näher an das Ufer gedrängt, wo er durch räuberische Landtiere stärker gefährdet ist.

Um die Bedrohung durch Fressfeinde frühzeitig zu sichten, sitzen die männlichen Rotflügelstärlinge häufig auf der Spitze der Schilfpflanzen über den Nestern oder in der Nähe der Nester. Bei den Krähen zum Beispiel, die eine Gefahr für die Eier und Jungvögel stellen, fliegt der männliche Rotflügelstärling sofort auf, wenn er die Krähe sichtet, um sie nicht auf das Nest aufmerksam zu machen. Durch dieses Verhalten macht er auch die Altvögel in der Nachbarschaft auf die drohende Gefahr aufmerksam und schützt somit deren Brut. Eine frühzeitige Sichtung wird an Sümpfen durch fehlende Bäume ermöglicht, die nicht die Sicht versperren.

Der anpassungsfähige Rotflügelstärling ist ein häufiger Bewohner der flussnahen Sumpfgebiete, nasstrockenen Wiesen, Weiden oder Felder in Nordamerika. Als Zugvogel verbringt er den Winter in Mittel- und Südnordamerika. Von Baja California bis zu Florida. Weitere Vorkommen gibt es in Costa Rica, Kuba und den Bahamas. Im Frühjahr zieht er in großen Schwärmen in die Brutgebiete in den Norden von Nordamerika; unter anderem südöstliches Alaska und Kanada.

Der gesellige Rotflügelstärling sammelt sich außerhalb der Brutzeit, meist nachdem die letzte Brut flügge ist, in großen Gruppen. Einerseits vertilgen sie große Mengen von schädlichen Insekten, auf der anderen Seite richten sie zum Ärger vieler Landwirte beträchtliche Schäden an Obstplantagen oder Getreidefeldern an. Viele Rotflügelstärlinge werden von den Landwirten mit vergiftetem Reis getötet. Die Vögel sterben nach zwei bis drei Tagen an der Zerstörung der Nieren.

Trotz dieser Bekämpfungsmaßnahme hat sich die Anzahl der Rotflügelstärlinge ständig erhöht. Die Landwirte bauten mehr Getreide an, sodass die Vögel die rauen Winter überleben konnten. Ein weiterer Grund ist die Häufigkeit von milden Wintern. In South Dakota hat sich die Anzahl der Sumpfpflanzen vergrößert, sodass mehr Gelege ausgebrütet wurden. Eine Studie in North- und South Dakota kam zum Ergebnis, dass der Bestand sich dort zwischen 1996 und 1999 um 33 % erhöht hat.

Eine gewisse Bekanntheit erreichte die Art, weil es im Winter 2010–2011 in den USA zu einem rätselhaften Vogelsterben kam. Rund 500 Kilometer nördlich von Pointe Coupee fielen nach der Silvesternacht am 1. Januar 2011 massenhaft Vögel vom Himmel und wurden tot aufgesammelt. Experten rätselten, warum dort tausende Vögel über dem Städtchen Beebe vom Himmel stürzten. Es handelte sich zumeist um Rotflügelstärlinge. Tiermediziner der staatlichen Veterinärkommission schlossen in ihrem vorläufigen Bericht aus, dass Krankheiten oder Viren für den massenhaften Tod verantwortlich seien. Alle wichtigen Organe seien gesund gewesen. Die Vögel könnten durch Silvesterböller aufgeschreckt worden und in der Nacht umhergeflogen sein, was sie sonst nicht tun, da sie im Dunkeln schlecht sehen können. Eine Ornithologin, die für eine staatliche Behörde arbeitet, sagte, die Rotflügelstärlinge hätten Anzeichen eines physischen Traumas aufgewiesen. Möglich sei auch, dass der Schwarm von einem Blitz oder Hagel in großer Höhe getroffen worden sei.[2] Mindestens ein Teil der Vögel wurden durch vom US-Landwirtschaftsministerium ausgelegtes Gift getötet. Sie hatten durch Fraß und Kot Schäden an Futterstellen verursacht.[3]

Es sind zweiundzwanzig Unterarten bekannt:[4]

Zu dem Rotflügelstärling gibt es überwiegend nur englische Literatur:

Der Rotflügelstärling (Agelaius phoeniceus), früher auch rotschulteriger Star oder Sumpfhordenvogel genannt, ist ein Vogel aus der Familie der Stärlinge (Icteridae). Er ist einer der bestuntersuchten Singvögel in Nordamerika.

Die erste Zeichnung eines Rotflügelstärlings wurde von Mark Catesby angefertigt. Anhand seiner Zeichnung beschrieb Carl von Linné 1766 den Vogel wissenschaftlich.

Çûkreşê çengsor yan baskesor (Agelaius phoeniceus), cureyekî fîkaran e ku li pir waran li parzemîna Amerîkaya Bakur û navîn dijî ye.[2]

Çûkreşê çengsor yan baskesor (Agelaius phoeniceus), cureyekî fîkaran e ku li pir waran li parzemîna Amerîkaya Bakur û navîn dijî ye.

Bergeha paşî ya A. p. gubernator

Çûkreşê çengsor ê mê

Çûkreşa çengsor

The red-winged blackbird (Agelaius phoeniceus) is a passerine bird of the family Icteridae found in most of North America and much of Central America. It breeds from Alaska and Newfoundland south to Florida, the Gulf of Mexico, Mexico, and Guatemala, with isolated populations in western El Salvador, northwestern Honduras, and northwestern Costa Rica. It may winter as far north as Pennsylvania and British Columbia, but northern populations are generally migratory, moving south to Mexico and the Southern United States. Claims have been made that it is the most abundant living land bird in North America, as bird-counting censuses of wintering red-winged blackbirds sometimes show that loose flocks can number in excess of a million birds per flock and the full number of breeding pairs across North and Central America may exceed 250 million in peak years. It also ranks among the best-studied wild bird species in the world.[2][3][4][5][6] The red-winged blackbird is sexually dimorphic; the male is all black with a red shoulder and yellow wing bar, while the female is a nondescript dark brown. Seeds and insects make up the bulk of the red-winged blackbird's diet.

The red-winged blackbird is one of five species in the genus Agelaius and is included in the family Icteridae, which is made up of passerine birds found in North and South America.[7] The red-winged blackbird was formally described as Oriolus phoeniceus by Carl Linnaeus in 1766 in the twelfth edition of his Systema Naturae,[8] but was later moved with the other American blackbirds to the genus Agelaius by Louis Jean Pierre Vieillot in 1816.[9] Linnaeus specified the type location as "America" but this was restricted to Charleston, South Carolina in 1928.[10][11] The genus name is derived from Ancient Greek agelaios, meaning "gregarious". The specific epithet, phoeniceus, is Latin meaning "crimson" or "red".[12] The red-winged blackbird is a sister species to the red-shouldered blackbird (Agelaius assimilis) that is endemic to Cuba. These two species are together sister to the tricolored blackbird (Agelaius tricolor) that is found on the Pacific coast region of the California and upper Baja California in Mexico.[13][14]

Depending on the authority, between 20 and 24 subspecies are recognised which are mostly quite similar in appearance.[15][16] However, there are two isolated populations of bicolored blackbirds that are quite distinctive: A. p. californicus of California and A. p. gubernator of central Mexico. The taxonomy and relationships between these two populations and with red-winged blackbirds is still unclear.[17] Despite the similarities in most forms of the red-winged blackbird, in the subspecies of Mexican Plateau, A. p. gubernator, the female's veining is greatly reduced and restricted to the throat; the rest of the plumage is very dark brown,[18][19] and also in a different family from the European redwing and the Old World common blackbird, which are thrushes (Turdidae).[20] In the California subspecies, A. p. californicus and A. p. mailliardorum, the veining of the female specimens also covers a smaller surface and the plumage is dark brown, although not in the gubernator grade;[19] and also its superciliary list is absent or poorly developed.[18] The male subspecies mailliardorum, californicus, aciculatus, neutralis, and gubernator lack the yellow band on the wing that is present in most male members of the other subspecies.[18][16] The red-shouldered blackbird was formerly considered as a subspecies of red-winged blackbird. They were split by the American Ornithologists' Union in 1997.[21]

Listed below are the red-winged blackbird subspecies and groups of subspecies recognized as of January 2014 with their respective distribution areas and the location of their wintering quarters:[16]

The common name for the red-winged blackbird is taken from the mainly black adult male's distinctive red shoulder patches, or epaulets, which are visible when the bird is flying or displaying.[22] At rest, the male also shows a pale yellow wingbar. The spots of males less than one year old, generally subordinate, are smaller and more orange than those of adults.[23] The female is blackish-brown and paler below. The female is smaller than the male, at 17–18 cm (6.7–7.1 in) long and weighing 41.5 g (1.46 oz), against his length of 22–24 cm (8.7–9.4 in) and weight of 64 g (2.3 oz).[24] The smallest females may weigh as little as 29 g (1.0 oz) whereas the largest males can weigh up to 82 g (2.9 oz).[25] Each wing can range from 8.1–14.4 cm (3.2–5.7 in), the tail measures 6.1–10.9 cm (2.4–4.3 in), the culmen measures 1.3–3.2 cm (0.51–1.26 in) and the tarsus measures 2.1 cm (0.83 in).[17] The upper parts of the female are brown, while the lower parts are covered by an intense white and dark veining;[26] also presents a whitish superciliary list.[27][28] According to Crawford (1977), females exhibit a salmon-pink stain on the shoulders and a light pink color on the face and below this when they are a year old, while older females show a stain usually more crimson on the shoulders and a darker pink hue on and under the face.[29] Observations in females in captivity indicate that small amounts of yellow pigment are present on the shoulders of these after leaving the nest, that the concentration of the pigment increases with the first winter plumage after the change of the feathers and that the passage from yellow to orange generally takes place in the second summer with the acquisition of the second winter plumage, after which no further changes in feather color occur.[30] The colored area on the wing increases in surface with the age of the female,[31] and varies in intensity from brown to a bright red-orange similar to that of the males in their first year.[32]

Young birds resemble the female, but are paler below and have buff feather fringes. Both sexes have a sharply pointed bill. The tail is of medium length and is rounded. The eyes, bill, and feet are all black.[27] Unlike most North American passerines which develop their adult plumage in their first year of life so that the one-year-old and the oldest individual are indistinguishable in the breeding season, the red-winged blackbird does not. It acquires its adult plumage only after the breeding season of the year following its birth when it is between thirteen and fifteen months of age.[33] Young males go through a transition stage in which the wing spots have an orange coloration before acquiring the most intense tone typical of adults.[28]

The male measures between 22 and 24 cm (8.7 and 9.4 in) in length, while the female measures 17 or 18 cm (6.7 or 7.1 in).[18] Its wingspan is between 31 and 40 cm (12 and 16 in) approximately.[18] Both the peak male and the legs, the claws and the eyes are black;[34][28][35] in the female beak is dark brown and clear in the upper half at the bottom,[28] and the tail is medium in length and rounded.[27] As in other species polygyny exists, the red-winged blackbird exhibit considerable sexual dimorphism both in plumage and size, males weighing between 65 and 80g the females about 35g.[36] Males are 50% heavier than females, 20% larger in its linear dimensions,[37] and 20% larger compared to the length of their wings.[38] The trend towards greater dimorphism in the size of non-monogamous ichterid species indicates that the larger size of males has evolved due to sexual selection.[38]

The male is unmistakable except in the far west of the US, where the tricolored blackbird occurs. Males of that species have a darker red epaulet edged with white, not yellow. Females of tricolored, bicolored, red-shouldered and red-winged blackbirds can be difficult to identify in areas where more than one form occurs. In flight, when the field marks are not easily seen, the red-winged blackbird can be distinguished from less closely related icterids such as common grackle and brown-headed cowbird by its different silhouette and undulating flight.[17]

Two keto-carotenoids – carotenoid with a ketone group – reds synthesized by the birds themselves – namely astaxanthin and canthaxanthin – are responsible for the bright red color of the wing spots, but two yellow dietary precursor pigments – lutein and zeaxanthin – are also present in moderately high concentrations in red feathers. Astaxanthin is the carotenoid more abundant (35% of the total), followed by lutein (28%), canthaxanthin (23%) and zeaxanthin (12%). Such a balanced combination of dietary precursors and metabolic derivatives in colored feathers is quite unusual, not only within a species as a whole but also in individuals and particular feathers.[39]

After removing the carotenoids in an experiment, the red feathers acquired a deep brown coloration. This is because the feather barbles of the colored spot contain melanin pigments – mainly eumelanin, which was equivalent to 83% of all melanins, but also pheomelanin at a concentration approximately equal to that of carotenoids, which seems to be a rare trait for carotenoid-based ornamental plumage. On the other hand, the feathers of the yellow stripes of the males are devoid of carotenoids —except occasionally when they appear tinged with a pink coloration derived from small amounts of said pigments— and present high concentrations of pheomelanin —82% of all melanins. Melanin concentrations in the yellow band are even higher than in the red spot.[39]

These markings are vital in the defense of the territory.[40] Males with larger spots are more effective at chasing away their non-territorial rivals and are more successful in contests within aviaries.[41][42][43] When the red shoulder patches were dyed black as part of an experiment, 64% of males lost their territories, while only 8% of control subjects did. However, males whose wings had been dyed before they had mated could still attract females and successfully reproduce. In the red-winged blackbird, the spots on the wings are a sign of threat among males and have an unimportant role, if any, in intersex encounters. Therefore, the spots are likely to have evolved in response to pressures linked to intrasexual selection.[44] Additionally, neither the size nor the coloration of the same are linked to the reproductive success of the males with those females that are not their mates, that is, those with which they eventually mate.[40] It has been suggested that also in the case of females, the best explanation for the evolution of a variable coloration in the shoulder spots is that their intensity indicates their physical condition in aggressive encounters between them.[32]

The fact that female red-winged blackbirds do not appear to consistently use variability in the size and color of male wing spots when choosing a mate runs counter to the classic role of carotenoid pigmentation ornamental feathers, mostly used in the attraction of a couple. In turn, its use as a sign of aggressiveness and social status against rival males is not a common trait in carotenoid ornaments. On the other hand, ornaments with a preponderance of melanin do tend to have an important role as an indicator of status in avian populations, so the spots of red-winged blackbirds seem to work more as melanin ornaments than as carotenoids.[39]

The calls of the red-winged blackbird are a throaty check and a high slurred whistle, terrr-eeee. The male's song, accompanied by a display of his red shoulder patches, is a scratchy oak-a-lee,[45] except that in many western birds, including bicolored blackbirds, it is ooPREEEEEom.[46] The female also sings, typically a scolding chatter chit chit chit chit chit chit cheer teer teer teerr.[17]

The most critical period of feather molting runs from late August to early September. When viewed in flight, they have a misaligned or "moth-eaten" appearance and generally slower and more laborious travel. Their mobility is reduced due to the lack of several remiges or rectrices or these are not entirely renewed. Most of the red-winged blackbirds have moved almost entirely by October. By then, some birds have not completed the molt of the feathers of the capital region and the helmsmen of the center of the tail and the internal secondary sprouts have only partially emerged from the pod. Virtually all individuals have completed their molts by mid-October.[47]

Birds do not begin their migration to wintering quarters until the two outer primary sprouts and the two inner or central rectrices have completed at least two-thirds of their development. Therefore, there is a correlation between molting, particularly replacement of the remiges and rectrices, and fall migration in red-winged blackbirds.[47]

Despite the fact that the brown or white tips on the feathers of the males are larger just after the molt and that they wear out throughout the year, the individuals vary considerably regarding the size of these non-black tips on the feathers in spring.[49]

Complete replacement of wing feathers takes about eight weeks. However, birds in their first year frequently retain some of the under-wing coverts and juvenile tertiary remiges after post-juvenile moulting. Of seventy immature males examined during the last week of October, it retained 70% of older lower primary blankets. In most cases where partial replacement of the covert feathers occurs, it is the proximal coverts that the bird retains.[47]

Primary remiges are one of the first feathers to molt. The molt of these feathers proceeds regularly from the innermost primary—primary I—to the outermost—primary IX. By October 1, most birds have either acquired the three new external primaries—VII, VIII, and IX—or they are at some advanced stage of development. The average dates for completion of the development of the new primary springs are: August 15 for primary I; September 1, primary II-IV; September 15, primary V and VI; and October 1, primaries VII-IX.[47]

The molting of the secondary remiges begins with the most external—secondary I— and proceeds inward to secondary VI. The secondary I sheath appears around the same time that all the secondary covers have been replaced and rarely before mid-August. These feathers are not completely renewed until the beginning of October.[47]

The molt of the tertiary remiges begins more or less at the same time as that of the secondary ones. The middle tertiary falls first, followed by the internal tertiary. Both feathers are often well developed again before the outer tertiary leaves the sheath.[47]

The major primary blankets are changed along with their respective primary springs. Unlike the major primary coats, the major secondary coats molt earlier than the secondary spruces. The molting of these feathers is rapid, with several of them at the same stage of development simultaneously. The progression of the molt in these feathers is from the outside to the inside, as in the secondary remiges. Most birds has completed the change of the secondary coverts to August 15, more or less at the time is appreciable only secondary sheath remige I.[47]

The molting of the lesser coverts begins early, often being the first feathers to fall. The onset of molting in male juveniles is particularly noticeable because it involves the replacement of the minor covers and results in the appearance of the reddish or orange wing spot. The new wing spot contrasts sharply with the yellowish-brown juvenile plumage in this area of the wing. The move of the minor blankets has generally been completed by September 1.[47]

Alula feathers complete their development at about the same time as the last three primary sprouts. The marginal covers on the upper or outer surface of the forearm, located below the alula, shed at approximately the same time that the primary remix VI is being replaced.[47]

The first feathers under the wing to molt are the marginal coverts, under the forearm. The shedding of these feathers begins at about the same time that the primary remix IV falls and is followed by that of the lower middle primary and lower middle secondary coats. The progression of the molting of the lower middle secondary blankets is from the outside to the inside, while that of the lower middle primary mats seems to be irregular or almost simultaneous. The medial lower coverts molt before the primary remiges VIII and IX. The major lower primary coverts and major lower secondary coverts molt last. The progression of the molting of these last feathers is the same as in the primary and secondary sprouts, that is, from the inside out and from the outside in, respectively.[47]

The caudal feathers comprise the rudder or rectrix feathers and the upper and lower tail covers. The tail covers begin to shed before the rectrices. Generally, the upper tail covers begin to shed first. Certain birds lose some rectrices by the end of the third week of August. The helmsmen in the center of the queue are the last rectrices to be renovated.[47]

Molting in the capital region involves changing the feathers of the pileus and the sides of the head. It is one of the last parts of the body to begin feather replacement, but the renewal of most of the capital feathers is complete before that of the secondary feathers, tail feathers, and under-wing feathers. The beginning of the molt in this region coincides with the beginning of the development of the primary remige V or VI. Some individuals have already started replacing the capital feathers by mid-August. The molt begins at the pileus and the last areas of the capital region to complete it are the eye strip and the cheeks (malar region).[47]

In some birds, the first signs of molt in the ventral feathers appear during the last days of July, when the feathers of the anterior portion of the laterals begin to fall. From there, the molt progresses backward along the sides and forward toward the throat and chin. The last ventral feathers to be replaced are those towards the center of the abdomen. The molt of the dorsal feathers begins around the first week of August. It begins at the bladder, progresses to the upper back, and then to the cervical region.[47]

The earliest evidence of molting in the humeral plumes corresponds to the last days of July. The molt comes from the anterior region backwards. The change of the femoral feathers begins later than that of the humeral ones. However, the progression is similar. Replacement of feather feathers rarely begins before August 15. The progression is generally from the proximal end of the tibia to the tarsometatarsal region.[47]

The red-winged blackbird is widely spread throughout North America, except in the arid desert, high mountain ranges, and arctic or dense afforestation regions.[48] It breeds from central-eastern Alaska and Yukon in the northwest,[50] and Newfoundland in the northeast,[18] to northern Costa Rica in the south, and from the Atlantic to the Pacific.[50] Northern populations migrate to the southern United States, but those that breed there, in Mexico, and in Central America are sedentary.[16] Red-winged blackbirds in the northern reaches of the range are migratory, spending winters in the southern United States and Central America. Migration begins in September or October, but occasionally as early as August. In western and Central America, populations are generally non-migratory.[28]

The red-winged blackbird inhabits open grassy areas. It generally prefers wetlands, and inhabits both freshwater and saltwater marshes, particularly if cattail is present. It is also found in dry upland areas, where it inhabits meadows, prairies, and old fields.[28] In a large part of its distribution area, it constitutes the most abundant passerine bird in the swamps in which it nests.[50] It is also present in areas without much water, where it inhabits open fields – often agricultural areas – and sparse deciduous forests.[28]

In the winter of 1975–1976, near Milan in western Tennessee, red-winged blackbirds were observed resting in a mixed roost that came to house 11 million individuals in January and early February in a plantation of 4.5 hectares of yellow pine (Pinus taeda) with little undergrowth was seen in soybean fields during the day, being that these constituted only 21% of the habitat in the area and that the other bird species present in the roost were not commonly observed in these fields; they were also common in cornfields. the presences of the bird in feedlots has increased as winter progressed, but, accounting for less than 5% of the icterids and starlings recorded in both feedlots of cows and pigs, they were much rarer there than the brown-headed cowbird, common grackle and common starling.[51]

During the breeding season, the density of breeding adults is much higher in swamps than in highland fields.[43] Although the highest concentrations of nesting red-winged blackbird are found in swamps, most of them nest in upland habitats since they are much more abundant.[52][53][54] In a study conducted in the Wood County, Ohio between 1964 and 1968, the density of territorial males in wetland habitat was found to be 2.89 times those in upland habitat. But, because of the small amount of wetland habitat, the total estimated upland population of territorial males was 2.14 times the wetland population. Alfalfa (Medicago sativa) and other legume crops (hay) were the principal habitat for breeding redwings in the county. Despite the marked preference for wetland habitats, the greater population in uplands reflects wetlands' scarcity.[55]

In that same study, reproductive individuals in upland habitats demonstrated a slight preference for old and new grasses such as Phleum pratense, Dactylis glomerata, Poa spp., Festuca spp., and Bromus spp. In the early part of the breeding season and new non-graminoid herbaceous plants in the mid and late season. In wetlands, they consistently preferred old and new broadleaf monocotyledons, primarily Carex spp, broadleaf, and Typha spp, and consistently rejected old and new narrow-leaved monocots, primarily narrow-leaved Phalaris arundinacea and Calamagrostis canadensis, and non-graminoid herbaceous plants. Red-winged blackbirds breeding in the highlands favored older tall vegetation only in the early part of the breeding season on April to May, and higher new vegetation and dense vegetation throughout the breeding season. For their part, those who settled in wetlands seemed to have a slight predilection for taller old vegetation.[56] During the breeding season, this species is attracted to tall vegetation that restricts visibility.[56][57]

Early season preferences for old grassland in the highlands and old broadleaf monocotyledons in wetlands point to the importance of upright residual vegetation. Highland grasses and broadleaf monocots in wetlands stand partially vertically and are easily visible in early spring, unlike clovers, narrow-leaved monocotyledons in wetlands and most non-graminoid herbaceous plants. Old alfalfa plants are also partially upright in early spring, but they are not as consistently chosen a species as old grasses. The start of the territorial activity is earlier when the amount of residual vegetation is large. Vegetation structural strength also appears to be important for nesting as females tend to broadleaf monocotyledons in wetlands throughout the breeding season and new non-graminoid herbaceous plants in the mid to late season.[56]

In southwestern Michigan, the density of cattail stems in different ponds was positively related to the concentration of reproductive adults.[58] However, other studies detected a predilection for more scattered vegetation.[57][59] One found that red-winged blackbirds avoided the marsh wren (Pantaneros chivirenes), a predator common in nests of this species, reproducing among more dispersed vegetation, which was more easily defended from the chivirines; conversely, the chivirines seemed to prefer the denser vegetation, where they were more likely to avoid the aggressiveness of the red-winged blackbird; These differences in habitat selection between one species and another resulted in spatial segregation of their breeding areas.[59] On the other hand, red-winged blackbirds tend to opt for small lots of vegetation and plants with thick stems.[57]

The red-winged blackbird is territorial, polygynous, gregarious and a short-distance migratory bird. Its way of flying is characteristic, with rapid wing flaps punctuated by brief periods of gliding flight.[48] The behavior of males makes their presence easily perceived: they perch in high places[27] such as trees, bushes, fences, telephone lines, etc.[60] Females tend to stay low, prowling through the vegetation and building their nests. They can be found in home gardens, particularly during their migration, if seeds have been scattered on the ground.[27] The forest curtains serve as a resting place during the day.[61]

For several weeks after their first appearance in early spring, red-winged blackbirds are generally seen in flocks made up entirely of males. During those days, they are seldom seen at their breeding sites, except early morning and late afternoon. In most of the remaining hours of the day, they frequent open and often elevated agricultural land, where they feed mainly on grain stubble and grassy fields. When disturbed while eating, they fly to the nearest deciduous trees and immediately after landing they begin to sing.[48]

The red-winged blackbird is omnivorous. It feeds primarily on plant materials, including seeds from weeds and waste grain such as corn and rice, but about a quarter of its diet consists of insects and other small animals, and considerably more so during breeding season.[62] It prefers insects, such as dragonflies, damselflies, butterflies, moths, and flies, but also consumes snails, frogs, eggs, carrion, worms, spiders, mollusks. The red-winged blackbird forages for insects by picking them from plants, or by catching them in flight.[27] Sometimes insects are obtained by exploring the bases of aquatic plants with their small beaks, opening holes to reach the insects hidden inside.[27][28] Aquatic insects, particularly odonates emerging, are of great importance in the diet of red-winged blackbirds that breed in swamps. These birds typically capture the odonates when the larvae climb up the stem of a plant from the water, get rid of their exuviae, and cling to the vegetation while their exoskeletons harden.[58] The years of emergence of periodical cicadas, it provides an overabundant amount of food.[32] In season, they also eat blueberries, blackberries and other fruits.[18] According to Edward Howe Forbush, when they arrive north in the spring, they feed in the fields and meadows. Then, they follow the plows, collecting larvae, earthworms and caterpillars left exposed, and in case there is a plague of Paleacrita vernata caterpillars in a fruit orchard, these birds will fly a kilometer to get them for their chicks.[48]

In season, it eats blueberries, blackberries, and other fruit. These birds can be lured to backyard bird feeders by bread and seed mixtures and suet. In late summer and in autumn, the red-winged blackbird will feed in open fields, mixed with grackles, cowbirds, and starlings in flocks which can number in the thousands.[63] It feeds on corn while it is maturing; once the grain has hardened it is relatively safe from this bird, since its beak and digestive system are not adapted for the consumption of hard and whole corn grains, unlike the Common grackle, which has a longer and stronger beak.[53] Studies of the stomachs of individuals of both sexes reveal that males consume higher proportions of crop grains, while females ingest a relatively larger amount of herb seeds and animal matter.[30] In the winter of 1975–1976, near Milan, western Tennessee, corn and herb seeds were the main foods consumed by red-winged blackbird. Herbs whose seeds were commonly consumed were Sorghum halepense, Xanthium strumarium, Digitaria ischaemum, Sporobolus spp., Polygonum spp. and Amaranthus spp.[51]

The red-winged blackbird nests in loose colonies. The nest is built in cattails, rushes, grasses, sedge, or alder or willow bushes. The nest is constructed entirely by the female over the course of three to six days. It is a basket of grasses, sedge, and mosses, lined with mud, and bound to surrounding grasses or branches.[27] It is located 7.6 cm (3.0 in) to 4.3 m (14 ft) above water.[64]

A clutch consists of three or four, rarely five, eggs. Eggs are oval, smooth and slightly glossy, and measure 24.8 mm × 17.55 mm (0.976 in × 0.691 in).[64] They are pale bluish green, marked with brown, purple, and/or black, with most markings around the larger end of the egg. These are incubated by the female alone, and hatch in 11 to 12 days. Red-winged blackbirds are hatched blind and naked, but are ready to leave the nest 11 to 14 days after hatching.[24]

Red-winged blackbirds are polygynous, with territorial males defending up to 10 females. However, females frequently copulate with males other than their social mate and often lay clutches of mixed paternity. Pairs raise two or three clutches per season, in a new nest for each clutch.[24]

The reproductive season of the red-winged blackbird extends approximately from the end of April to the end of July.[65][66] On the other hand, in different states has been estimated that the period in which the active nests contained eggs lay between beginning in late April and early late August; and in northern Louisiana nests were found to harbor chicks from late April to late July. The peak of the nesting season (the time with the highest number of active nests) has been recorded between the first half of May and the beginning of June in different places.[67] A study in eastern Ontario found that although red-winged blackbirds began nesting earlier in years with warm springs, associated with low winter values in the North Atlantic Oscillation Index, egg laying dates remained unchanged.[68] Male testosterone levels peak in the early part of the breeding season, but remain high throughout the season.[49] Females reproduce for up to ten years.[69]

Many aspects of territorialism (for example, the number of male songs and displays, and the number of intrusions into foreign territories) peak before mating. After this, the frequency of many of the territorial behaviors decreases and the males are mainly concerned with defending the females, eggs, and chicks against predation. Experiments in the systematic removal of birds from their territories suggest that the extra population of males that is present in swamps before copulations disappears after copulation.[70]

Predation of eggs and nestlings is quite common. Nest predators include snakes, mink, raccoons, and other birds, even as small as marsh wrens. The red-winged blackbird is occasionally a victim of brood parasites, particularly brown-headed cowbirds.[63] Since nest predation is common, several adaptations have evolved in this species. Group nesting is one such trait which reduces the risk of individual predation by increasing the number of alert parents. Nesting over water reduces the likelihood of predation, as do alarm calls. Nests, in particular, offer a strategic advantage over predators in that they are often well concealed in thick, waterside reeds and positioned at a height of one to two meters.[71] Males often act as sentinels, employing a variety of calls to denote the kind and severity of danger. Mobbing, especially by males, is also used to scare off unwanted predators, although mobbing often targets large animals and man-made devices by mistake. The brownish coloration of the female may also serve as an anti-predator trait in that it may provide camouflage for her and her nest while she is incubating.[28]

Predators of red-winged blackbirds include such species as raccoons,[72] American mink,[73] long-tailed weasels,[74] black-billed magpies,[75] common grackles,[48] owls,[28] red-tailed hawks,[76] short-tailed hawks,[77] and snakes[78] (such as the northern water snake[48] and the plains garter snake[75]). Ravens and grazers such as marsh wrens feed on eggs (and even small chicks), if the nest is left unattended,[48] destroying the eggs, occasionally drinking from them, and pecking the nestlings to death.[79]

The relative importance of different nest predators varies by geographic region: the top predators in different regions include the marsh wren in British Columbia, the magpies in Washington, and the raccoons in Ontario.[75] The incidence of avian predation in red-winged blackbird nests is higher in western populations than in eastern populations.[80]

Due to high predation rates, especially of eggs and chicks, the red-winged blackbird has developed various adaptations to protect its nests. One of them consists of nesting in groups, which reduces the danger since there is a greater number of alert parents. Nesting over water also lowers the chances of an attack. Nests in particular offer a strategic advantage as they are often hidden among dense riparian reeds, at a height of one or two meters.[72] males often act as sentinels, using a repertoire of calls.[81] Males in particular hunt down potential predators to scare them away, even when dealing with much larger animals.[72] Aggressiveness of the red-winged blackbird towards the marsh wren, which also nests in swamps, causes a partial interspecies territorialism.[82] On the other hand, nocturnal predators such as raccoons and American mink are not attacked by adults.[75][83] Coloration of the female could serve to camouflage it, protecting it and its nest when it is incubated.[72]

The red-winged blackbird can accommodate ectoparasites such as various Phthiraptera, the Ischnocera Philopterus agelaii and Brueelia ornatissima,[84] and hematophagous mites, like Ornithonyssus sylviarum,[84] and endoparasites like Haemoproteus quiscalus, Leucocytozoon icteris, Plasmodium vaughani, nematodes,[84] flukes and tapeworms.[85]

The red-winged blackbird aggressively defends its territory from other animals, and will attack much larger birds.[63] During breeding season, males will swoop at humans who encroach upon their nesting territory.[86][87] Male red-winged blackbirds also exhibit important territorial behaviors, most of which provides them with the necessary fidelity for many years to come. A few important factors for male red-winged blackbirds’ adherence to territories include food, hiding spaces from predators, types of neighbors, and reactions towards predators. Additionally, a study was done on site fidelity and movement patterns by Les D. Beletsky and Gordon H. Orians in 1987 which explained much of the males’ territorial behaviors once migrated and settled onto a territory of their own. Sufficient evidence had shown that males are committed to staying in their territory over a long period of time and are not more likely to change territories at a younger age due to limited experience of knowledge for success. Studies also showed that most of the males that were first-time movers to a new territory were between two and three years old. The majority of males that moved were young and inexperienced. Later on they had moved towards more available territories. If males had chosen to leave their territory for reproductive success, as an example, they would do so within a short distance. Males who moved shorter distances were more successful in reproducing than those who moved longer distances. Further studies showed that when males moved further away from their territories there was a decrease in probability of successfully fledging.[88]

The maximum longevity of the red-winged blackbird in the wild is 15.8 years.[89]

Red-winged blackbirds that breed in the northern part of their range, i.e., Canada and border states in the United States, migrate south for the winter. However, populations near the Pacific and Gulf coasts of North America and those of Middle America are year-round resident.[2] Red-winged blackbirds live in both Northern U.S. and Canada, ranging from Yucatan Peninsula in the south to the southern part of Alaska.[2] These extensions account for the majority of the continent stretching from California's Pacific coast and Canada to the eastern seaboard. Much of the populations within Middle America are non-migratory.[28] During the fall, populations begin migrating towards Southern U.S. Movement of red-winged blackbirds can begin as early as August through October. Spring migration begins anywhere between mid-February to mid-May. Numerous birds from northern parts of the U.S., particularly the Great lakes, migrate nearly 1,200 km (750 mi) between their breeding season and winter[2] Winter territorial areas differ based on geographic location.[28] Other populations that migrate year-round include those located in Middle America or in the western U.S. and Gulf Coast. Females typically migrate longer distances than males. These female populations located near the Great Lakes migrate nearly 230 km (140 mi) farther. Yearly-traveled females also migrate further than adult males, while also moving roughly the same distance as other adult females. Red-winged blackbirds migrate primarily during daytime. In general, males’ migration flocks arrive prior to females in the spring and after females in the fall.[2]

According to the American ornithologist Arthur Cleveland Bent, in the northern regions of its range the eastern red-winged blackbird is almost completely beneficial from an economic perspective and there are comparatively few complaints of severe crop damage. Their diet consists almost entirely of insects, very few of which are useful species, and herb seeds. However, it causes certain damages to the grains that germinate in spring and to sweet corn in summer, while the grains are still soft, tearing the foliaceous covering of the ears and ruining them from a commercial point of view. It also attacks other grains in a limited way, but most of what it consumes is waste left in the ground. In the Midwest, where these birds are much more abundant and where cereals are grown more extensively than in the North, red-winged blackbirds and other ichterids, in late summer and fall, do great damage to grain fields, both while they are maturing as when they are harvested . However, it has been claimed that even there are beneficial because the larvae removed from corncobs and beet plants and can counteract pests of caterpillars. In the southern states, they seriously harm rice by plucking seedlings in spring and eating the still-soft grains as they mature, being in this sense almost as harmful as the Bobolink. On the other hand, they are of some use in consuming weed seeds that would otherwise devalue the product.[48]

Being one of the most numerous birds on the continent, it plays an important role in the dispersal of other species. Since red-winged blackbirds gather and rest in such large numbers, the survival of certain species that join their flocks is likely to be affected by their company.[28] They can also be an important source of food for animals such as raccoons and mink. Likewise, populations that nest and rest in swamps could cushion the effect of predation on duck species and other animals.[53] In summary, these birds are so numerous and active that their mere presence and natural behavior is enough to influence the environment in a visible way.[28]

Through the control of insect populations through predation and unwanted herbs with the consumption of their seeds, they allow the growth of larger plants and crops.[72][90] They also eat on Anthonomus grandis and Hypera postica, two species of weevils affecting cotton and alfalfa respectively, as well as harmful caterpillars of the European gypsy moth (Lymantria dispar) and of the genus Malacosoma.[48] In some areas of the southern United States, the seeds of the common plumber (Xanthium strumarium), a weed detrimental to soybeans and cotton, seems to be an important food source for the species.[53][51]

Beal (1900) stated: In summarizing the economic status of the red-winged blackbird, the main aspect to consider is the small percentage that grains represent in their annual diet, which apparently contradicts complaints about its destructive habits. Judging by stomach contents, the red-winged blackbird is decidedly a useful bird. The service it provides through the elimination of harmful insects and herb seeds far outweighs the damage caused by its consumption of grains. The havoc it sometimes causes must be entirely attributed to its excessive abundance in certain places.[48][91]

During the breeding season, the approximately 8 million red-winged blackbirds nesting in Ohio and their chicks probably consume more than 5.4 million kilograms (12,000,000 lb) of insects, an average of almost 53 kg/km2 (300 lb/sq mi). Many of these insects, such as the weevils (Hypera spp.), Come from alfalfa fields, pastures, oat fields and other crops. In cornfields, blackbirds often feed on corn worms (Helicoverpa zea) and beetles of the genus Diabrotica. In early spring, red-winged blackbirds consume corn borers (Ostrinia nubilalis) in fields with corn stubble.[53] However, Bendell et al. (1981) found that the economic benefit of pest control, such as larvae of that lepidopteran, by the red-winged blackbird only compensated for 20% of the damage to crops caused by this bird.[92][93]

The red-winged blackbirds can devastate farm fields. Despite the fact that they consume weed seeds, they are known to cause great damage to agriculture due to their habits of resting in massive groups and their taste for agricultural products.[28] may be also causes harm to plantings corn, rice, sunflower and sorghum,[28][61] particularly important near roosts.[61] Red-winged blackbird is the largest species of Icterid in North America and the most damaging to crops.[94][61][95] From 215 birds Neotropical migrants have been identified as causing, by a wide margin, the greatest economic loss.[92] In North America, the damage to corn crops by this species has increased since the late 1960s to early 1980s, perhaps because of the increase in the area for grain production,[96][97][98] and due to the reduction of small areas with stubble, hayfields and uncultivated land, which, in turn, accentuated the bird's dependence on corn to ensure its livelihood.[99]

Apparently, the male does more damage to this grain than the female. In some areas of Ohio, corn can account for up to 75% of the diet of males and only 6% of that of females in August and September. In South Dakota, in the late summer, the gizzards of the males studied contained 29% corn, while in the case of the female that number was limited to 9%.[53]

The red-winged blackbird is the dominant species in the large concentrations of blackbirds that feed on the fields of sunflower, corn and small grains maturing in late summer or early fall in the Dakotas. In the 1970s, losses to sunflower and corn crops caused by blackbirds in the Dakotas exceeded $3 million annually for each case.[100] In the northern part of the Great Plains, an area known as the Prairie Pothole Region, in red-winged blackbirds are very abundant in summer, they congregate in post-reproductive flocks that significantly harm crops, particularly sunflower plantations near their home sites. Most sunflower damage occurs between mid-August and early September, when the calorie content of immature seeds is low and birds must consume more of them to satiate themselves. During this initial stage of predation on sunflower crops in which more than 75% of the total damage is caused, the red-winged blackbird represent 80% of the blackbirds observed in the fields of this seed. This period predates the massive migration of birds and most of them are of local origin. Most remain within 200 km (120 mi) of their native sites until the molting of their feathers is complete or nearly complete in late August or early September. Damage can be quite serious in the center and southeast of North Dakota and Northeast South Dakota, areas of high concentration of sunflower production and abundant wetlands that attract red-winged blackbird during the breeding season.[101]

Investigations conducted between 1968 and 1979 revealed that blackbirds, notably the black-winged blackbird and the common grackle, annually destroyed less than 1% of corn crops in Ohio, amounting to a loss between 4 and 6 million dollars according to 1979 prices. [53]

All Ohio counties experience some degree of predation on their maize crops from blackbirds, but those most affected are a few counties where marshes that roost them still abound. The counties of Ottawa, Sandusky and Lucas, on the waters of Sandusky Bay and Lake Erie, were the hardest hit. These three counties, among the 19 studied between 1968 and 1976, contained 62% of the fields in which the losses exceeded 5% and 77% of those in which they exceeded 10%. Other counties with extensive localized damage were Erie, Ashtabula also located on the coasts of the mentioned water courses and Hamilton. Almost all the plantations with damages greater than 5% were within 8 km (5.0 mi) of some important roosting of blackbirds. In the 1968–1976 period, in northeast Sandusky County and northwest Ottawa, where large roosts of up to a million birds were discovered in late summer and fall, average losses exceeded 9% in fields 3 to 5 km (1.9 to 3.1 mi) from the roosts, but they were less than 5% at 8 km (5.0 mi) and less than 2% at 16 km (9.9 mi).[53] In southwestern Ontario, in the summer of 1964, it was found that the greatest damage to the cornfields by red-winged blackbird also occurred near roosts in swamps.[72]

The two main options that farmers can choose from to avoid the presence of birds once corn has entered the milky stage of its maturation process are the use of the chemical 4-aminopyridine and the implementation of mechanical devices to frighten birds away.[53] The time chosen to take measures to disperse the blackbirds is of great importance since once the birds have chosen a field to feed there they are likely to return for several days.[53][72] The longer be allowed to feed them unmolested, will become more difficult to scare them away.[53] Also, most of the damage is inflicted in just a few days, when the pimples are soft; consequently, control techniques will not be very useful if applied after this period.[53][102]

As early as 1667, Massachusetts Bay settlers had enacted laws to try to reduce blackbird populations and mitigate damage to corn. According to Henry David Thoreau, a law provided that each single man in a town must kill six of those birds and, as a punishment for not doing so, he could not marry until he had complied with the aforementioned design. Obviously, since blackbirds reproduce at a much higher speed than humans marry, this control strategy was a failure. Pioneers traveling west to the Great Lakes region faced similar problems. By 1749, blackbirds were so abundant around western Lake Erie that people took turns watching over the maturing grain crops.

At the beginning of the 20th century, in some places, when the reeds dried up, these circumstances were used to kill these birds in the following way. A crew approached a roost in silence, hidden in the darkness of the night, and simultaneously lit the reeds at various points, which were quickly enveloped by a single great flame. This caused a huge tumult among the red-winged blackbird, which, lit by fire, were shot down in large numbers as they hovered in midair and screamed all over the place. Sometimes straw was used for the same purpose, which was previously scattered near reeds and alder bushes (Alnus spp.) in which they gathered to rest, the burning of which caused great consternation among the birds. The gang returned the next day to collect the hunted prey.[48]

Arthur Cleveland Bent says that, before it was banned the sale of prey hunting in the market, red-winged blackbirds were massacred in large numbers in autumn and sold in markets. When they had put on weight on a diet of grains or rice, their small bodies were served as delicious snacks on the gourmet tables . Few could distinguish them from bobolinks (Dolichonyx oryzivorus).[48]

In 1926, when the US Biological Survey – predecessor of the United States Fish and Wildlife Service carried out its first compilation of roosts of undesirable ichterids, it was recorded in Ohio, with its large populations of these birds and the fifth largest area allocated to the cultivation of corn among the American states, a number of complaints higher than in any other state. During the 1950s, bird control committees were organized in some counties to deal with the damage to maize caused by blackbirds and the Ohio Agricultural Experiment Station now the Ohio Agricultural Research and Development Center and the Department of Zoology and Entomology of the state university began investigating the problem.[53]

Crop predation has led to the use of traps, poison and surfactants by farmers in an attempt to control populations of red-winged blackbirds;[28] these last properties suppress waterproof feathers, making them extremely vulnerable to the cold,[72][103] but their effectiveness depends on certain atmospheric conditions, namely low temperatures and rainfall.[103] Programs in which baits were used poisoned to reduce icteride concentrations in late summer have been unsuccessful. While thousands of birds have occasionally died, the effect on large roosting-associated flocks that sometimes contain more than a million individuals is small; In addition, specimens of other species frequently die. The use of large lure traps, which often catch hundreds of birds per day, is also ineffective against these large flocks.[53]