en

names in breadcrumbs

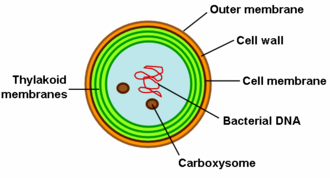

Synechocystis ist eine Gattung einzelliger Süßwasser-Cyanobakterien aus der Familie der Merismopediaceae. Sie umfasst eine (unbenannte) Spezies, Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803,[2] die ein gut untersuchter Modellorganismus ist.

Cyanobakterien sind photosynthetische Bakterien, die seit schätzungsweise 2,7 Milliarden Jahren auf der Erde existieren. Die Fähigkeit der Cyanobakterien, Sauerstoff zu produzieren, leitete den Übergang von einem Planeten mit hohem Kohlendioxidgehalt und wenig Sauerstoff zu einer Phase, die als Große Sauerstoffkatastrophe (Great Oxygenation Event) bezeichnet wird, in der große Mengen an Sauerstoff produziert wurden.[3] Cyanobakterien haben eine große Vielfalt an Lebensräumen besiedelt, darunter Süß- und Salzwasser-Ökosysteme und die meisten terrestrischen Umgebungen.[4]

Phylogenetisch gesehen verzweigt sich Synechocystis später im evolutionären Stammbaum der Cyanobakterien, weit weg von der basalen Spezies Gloeobacter violaceus (ancestral root, „Urwurzel“).[5] Synechocystis ist nicht diazotroph (Stickstoff-fixierend), aber eng mit einem anderen Modellorganismus, Cyanothece ATCC 51442, verwandt, welches diazotroph ist.[6] Daher wird vermutet, dass Synechocystis ursprünglich die Fähigkeit besaß, Stickstoffgas zu fixieren, aber später die Gene verloren hat, die erforderlich sind für ein voll funktionsfähiges Gencluster zur Stickstofffixierung (nif, nitrogen fixation).[7]

Die Spezies Synechocystis didemni Lewin 1975 wird heute in die Gattung Prochloron (ex Lewin 1977) Florenzano et al. 1986[14][15] gestellt mit gültigem Namen Prochloron didemni (ex Lewin 1977) Florenzano et al. 1986.[8]

Neben dem Referenzstamm von Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 wurden weitere Modifikationen dieses Elternstamms geschaffen, wie z. B. ein Unterstamm apcE-, dem das Photosystem I (PS1, auf dem apcE-Gen) fehlt.[16] Ein anderer weit verbreiteter Unterstamm von S. sp. PCC 6803 ist ein glukosetoleranter Stamm mit Bezeichnung ATCC 27184 – der Elternstamm PCC 6803 kann keine externe Glukose verwerten.[11]

Eine ganze Reihe von Cyanobakterien sind Modellmikroorganismen für die Untersuchung der Photosynthese, der Kohlenstoff- und Stickstoffassimilation, der Evolution von Plastiden (Chloroplasten etc.) und der Anpassungsfähigkeit an Umweltstress. Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 ist eine Linie einzelliger Süßwasser-Cyanobakterien der Gattung Synechocystis und wird vom NCBI als Spezies gelistet.[2] S. sp. PCC 6803 ist eine der am besten untersuchten Arten von Cyanobakterien, denn diese Cyanobakterien sind sowohl zu autotrophem (phototrophem Wachstum durch Photosynthese während der Lichtperioden) als auch zu heterotrophem Wachstum durch Glykolyse und oxidative Phosphorylierung während der Dunkelperioden fähig (Mixotrophie).[17] Der Photosyntheseapparat selbst ist dem von Landpflanzen sehr ähnlich. Der Organismus zeigt auch eine phototaktische Bewegung. Die Genexpression wird durch eine zirkadiane Uhr (circadian clock) reguliert, und der Organismus kann sich Übergänge zwischen den Licht- und Dunkelphasen effektiv einstellen.[18] S. sp. PCC 6803 kann leicht exogene DNA aufnehmen, zusätzlich zur Aufnahme von DNA durch Elektroporation, Ultraschalltransformation und Konjugation.[19]

Die Linie wurde 1968 aus einem Süßwassersee isoliert und wächst am besten zwischen 32 und 38 °C.[20]

Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 kann entweder auf Agarplatten oder in Flüssigkultur kultiviert werden. Das am weitesten verbreitete Kulturmedium ist eine BG-11-Salzlösung,[21] wie es auch für Synechococcus elongatus[22] und Gloeomargarita lithophora[23] Verwendung findet. Der ideale pH-Wert liegt zwischen 7 und 8,5; eine Lichtintensität von 50 μmol Photonen m−2 s−1 (pro Quadratmeter und Sekunde) führt zu bestem Wachstum. Das Sprudeln mit kohlendioxidangereicherter Luft (1-2 % CO2) kann die Wachstumsrate erhöhen, erfordert aber möglicherweise zusätzliche Puffer zur Aufrechterhaltung des pH-Werts.[17]

Die Selektion erfolgt typischerweise über Antibiotikaresistenzgene. Heidorn et al. 2011 ermittelten in S. sp. PCC 6803 experimentell die idealen Konzentrationen von Kanamycin, Spectinomycin, Streptomycin, Chloramphenicol, Erythromycin und Gentamicin.[17] Die Kulturen können für ca. 2 Wochen auf Agarplatten aufbewahrt und unbegrenzt nachgestreut werden.[21] Für die Langzeitlagerung sollten flüssige Zellkulturen in einer 15%igen Glycerinlösung bei −80 °C gelagert werden.[21]

Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 ist ein Modellorganismus, dennoch gibt es nur wenige synthetische Teile, die für die Gentechnik verwendet werden können. Da Cyanobakterien im Allgemeinen im Vergleich zu vielen pathogenen Bakterien langsame Verdopplungszeiten haben (4,5 bis 5 h bei S. sp. PCC 6301[10]), ist es effizienter, stattdessen möglichst viel DNA-Klonierung in einem schnell wachsenden Wirt wie Escherichia coli durchzuführen. Um Plasmide (stabile, sich replizierende zirkuläre DNA-Fragmente) – zu erzeugen, die erfolgreich in mehreren Spezies funktionieren, wird ein Shuttle-Plasmid (shuttle vector) mit einem breiten Wirtsspektrum benötigt.[17][24][25][26][27]

Cyanobakterien wurden auf verschiedene Weise zur Herstellung von erneuerbarem Biokraftstoff verwendet. Die ursprüngliche Methode bestand darin, Cyanobakterien für die Biomasse zu züchten um diese durch Verflüssigung in Flüssigkraftstoff umzuwandeln. Schätzungen legen nahe, dass die Biokraftstoffproduktion aus (unveränderten) Cyanobakterien nicht realisierbar ist, da der Erntefaktor EROEI (Energy Return on Energy Invested) ungünstig ist. Dies liegt daran, dass zahlreiche große, in sich geschlossene Bioreaktoren mit idealen Wachstumsbedingungen (Sonnenlicht, Düngemittel, konzentriertes Kohlendioxid, Sauerstoff) gebaut und betrieben werden müssen, was fossile Brennstoffe verbraucht. Außerdem ist eine weitere Nachbearbeitung der Cyanobakterienprodukte notwendig, was zusätzliche fossile Brennstoffe erfordert.[28]

Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 wurde aber als Modell verwendet, um die Energieausbeute von Cyanobakterien durch gentechnische Eingriffe zu erhöhen:

Es ist allerdings noch nicht klar, ob cyanobakterielle Biokraftstoffe in Zukunft eine brauchbare Alternative zu nicht-erneuerbaren fossilen Kraftstoffen sein werden.

Das Genom von Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 befindet sich in etwa 12 Kopien eines einzelnen DNA-Moleküls (Chromosoms) mit 3,57 Mbp (Megabasenpaare) Länge; drei kleinen Plasmiden: pCC5.2 mit 5,2 kbp (Kilobasenpaare), pCA2.4 mit 2,4 kbp und pCB2.4 mit 2,4 kbp; und vier großen Plasmiden: pSYSM mit 120 kbp, pSYSX mit 106 kbp, pSYSA mit 103 kbp und pSYSG mit 44 kbp.[34][35]

Der Glukose-tolerante Unterstamm ATCC 27184 von S. sp. PCC 6803 kann heterotroph im Dunkeln auf der Kohlenstoffquelle Glukose leben, benötigt aber aus noch unbekannten Gründen ein Minimum von 5 bis 15 Minuten (blaues) Licht pro Tag. Diese regulatorische Rolle des Lichts ist sowohl bei PS1- als auch bei PS2-defizienten Stämmen intakt.[36]

Einige glykolytische Gene werden durch das Gen sll1330 unter Licht- und Glukose-supplementierten Bedingungen reguliert. Eines der wichtigsten glykolytischen Gene ist das für Fructose-1,6-Bisphosphat-Aldolase (fbaA). Der mRNA-Spiegel von fbaA ist unter Licht- und Glukose-supplementierten Bedingungen erhöht.[37]

Das CRISPR-Cas-System (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindrome Repeats / CRISPR-associated proteins) sorgt für adaptive Immunität in Archaeen und Bakterien. Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 enthält drei verschiedene CRISPR-Cas-Systeme: Typ I-D und zwei Versionen von Typ III. Alle drei CRISPR-Cas-Systeme sind auf dem pSYSA-Plasmid lokalisiert. Das Typ-II-System, das bei vielen Spezies für gentechnische Zwecke adaptiert wurde, fehlt generell bei Cyanobakterien.[38]

Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 ist zu einer natürlichen Genetischen Transformation fähig.[39] Damit eine Transformation stattfinden kann, müssen sich die Empfängerbakterien in einem kompetenten Zustand befinden. Es konnte gezeigt werden, dass das Gen comF an der Kompetenzentwicklung in S. sp. PCC 6803 beteiligt ist.[40]

Synechocystis ist eine Gattung einzelliger Süßwasser-Cyanobakterien aus der Familie der Merismopediaceae. Sie umfasst eine (unbenannte) Spezies, Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803, die ein gut untersuchter Modellorganismus ist.

Synechocystis is a genus of unicellular, freshwater cyanobacteria in the family Merismopediaceae. It includes a strain, Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803, which is a well studied model organism.

Like all cyanobacteria, Synechocystis branches on the evolutionary tree from its ancestral root, Gloeobacter violaceus.[2] Synechocystis is not diazotrophic, and is closely related to another model organism, Cyanothece ATCC 51442.[3] It has been suggested that originally Synechocystis possessed the ability to fix atmospheric nitrogen, but lost the genes required for the process.[4]

Synechocystis is a genus of unicellular, freshwater cyanobacteria in the family Merismopediaceae. It includes a strain, Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803, which is a well studied model organism.

Synechocystis

Synechocystis Like all cyanobacteria, Synechocystis branches on the evolutionary tree from its ancestral root, Gloeobacter violaceus. Synechocystis is not diazotrophic, and is closely related to another model organism, Cyanothece ATCC 51442. It has been suggested that originally Synechocystis possessed the ability to fix atmospheric nitrogen, but lost the genes required for the process.

Synechocystis es un género de cianobacterias de agua dulce, representado principalmente por la cepa Synechocystis sp. PCC6803. Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 es capaz de crecer tanto en condiciones de luminosidad, realizando la fotosíntesis oxigénica (fototrofia), como en oscuridad, mediante glucólisis y fosforilación oxidativa (heterotrofia).[1] La expresión genética está regulada por un reloj circadiano, por lo que el organismo puede anticipar eficazmente las transiciones entre las fases de luz y oscuridad.[2]

Las cianobacterias son unos procariontes fotosintéticos que han existido en la tierra desde hace 2700 millones de años aproximadamente. La capacidad de las cianobacterias para producir oxígeno fue la causa de la Gran Oxidación.[3] Las cianobacterias han colonizado una amplia diversidad de hábitats, incluyendo ecosistemas de agua dulce y salada, y la mayoría de los ambientes terrestres.[4] Filogenéticamente, Synechocystis se ramifica del árbol evolutivo de las cianobacterias a partir de la raíz ancestral (Gloeobacter violaceus).[5] Synechocystis, que no es diazótrofo, está íntimamente relacionado con otro organismo modelo, Cyanothece ATCC 51442, que sí lo es.[6] Por tanto, se ha propuesto que originalmente Synechocystis poseía la habilidad de fijar nitrógeno atmosférico, pero perdió los genes requeridos para el proceso.[7]

Las cianobacterias son organismos modelo utilizados en el estudio de la fotosíntesis, de la asimilación de carbono y nitrógeno, de la evolución de los plastos vegetales y de la adaptabilidad al estrés del entorno. Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 es uno de los tipos de cianobacterias más estudiados pues puede crecer tanto autotrófica como heterotróficamente, si no se dan condiciones de luminosidad. Fue aislada del agua dulce de un lago en 1968 y su temperatura óptima de crecimiento se sitúa entre los 32 y los 38 °C.[8]

Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 puede tomar fácilmente ADN exógeno, via electroporación, transformación ultrasónica y conjugación.[9] El sistema fotosintético es muy similar al encontrado en las plantas terrestres. Los organismos de este género, además, exhiben movimiento fototáctico.

Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 puede crecer tanto en placas de agar como en cultivo líquido. El medio de cultivo más ampliamente utilizado es una solución salina BG-11.[10] ElpH ideal se sitúa entre 7 y 8.5.[1] Una intensidad luminosa de 50 μmol photons m−2 s−1 resulta en un mejor crecimiento.[1] El burbujeo del medio con aire enriquecido con dióxido de carbono (1–2% CO2) puede aumentar la tasa de crecimiento, pero requiere tamponamiento adicional a fin de mantener el pH.[1]

Normalmente la selección de las especies de Synechocystis se efectúa empleando la resistencia a antibióticos como factor diferencial. Heidorn et al. determinaron experimentalmente en 2011 las concentraciones ideales de kanamicina, espectinomicina, estreptomicina, cloranfenicol, eritromicina, ygentamicina para la cepaSynechocystis sp. PCC6803.[1] Los cultivos pueden ser mantenidos en placas de agar durante dos semanas aproximadamente, y siendo resembrados, ser mantenidos indefinidamente.[10] Para el almacenaje a largo plazo, el cultivo líquido de células debe mantenerse en una solución de glicerol al 15% a -80 °C.[10]

El genoma de Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 está contenido en 12 copias de un solo cromosoma (3.57 megabases); tres plásmidos pequeños: pCC5.2 (5.2 kb) pCA2.4 (2.4 kb), y pCB2.4 (2.4 kb); y cuatro plásmidos grandes: pSYSM (120 kb), pSYSX (106 kb), pSYSA (103kb), y pSYSG (44 kb).[11][12]

La cepa principal de Synechocystis sp. es PCC6803. Se han creado modificaciones de la cepa PCC6803 original, como una subcepa carente del fotosistema 1 (PSI).[13] Otra sub-cepa ampliamente utilizada de Synechocystis sp. es ATCC 27184, tolerante a la glucosa, puesto que PCC6803 no puede utilizar la glucosa del medio.[14]

La subcepa ATCC 27184 de Synechocystis sp. PCC6803, puede vivir heterotróficamente en condiciones de oscuridad utilizando la glucosa como fuente de carbono, pero por razones aún desconocidas requiere un mínimo de 5-15 minutos de luz azul al día. Este mecanismo regulador de la luz se mantiene inalterado en los mutantes sin PSI y PSII.[15]

Algunos genes glucolíticos están regulados por el gen sll1330 en medios luminosos y con glucosa. Uno de los genes más importantes de la glucólisis es el de la fructosa-1,6-bifosfato aldolasa (fbaA). Los niveles de ARNm de fbaA se incrementan en condiciones de luminosidad y suplementación de glucosa.[16]

El sistema CRISPR-Cas provee de inmunidad adaptativa a bacterias y arqueas. Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 contiene tres sistemas CRISPR-Cas diferentes: el tipo I-D, y dos versiones del tipo III. Todos estos sistemas se encuentran en el plásmido pSYSA. Las cianobacterias en su totalidad, carecen del sistema de tipo II (el cual ha sido recientemente adaptado como herramienta de ingeniería genética.[17]

Synechocystis es un género de cianobacterias de agua dulce, representado principalmente por la cepa Synechocystis sp. PCC6803. Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 es capaz de crecer tanto en condiciones de luminosidad, realizando la fotosíntesis oxigénica (fototrofia), como en oscuridad, mediante glucólisis y fosforilación oxidativa (heterotrofia). La expresión genética está regulada por un reloj circadiano, por lo que el organismo puede anticipar eficazmente las transiciones entre las fases de luz y oscuridad.

Synechocystis est un genre de cyanobactéries (autrefois appelées algues bleues) représentées en premier lieu par la souche Synechocystis sp. PCC6803. Cette dernière vit dans l'eau douce et est capable de se développer à la fois de façon phototrophe par photosynthèse oxygénique et de façon hétérotrophe par glycolyse et phosphorylation oxydative. Elle est capable d'anticiper les transitions jour-nuit à l'aide d'une horloge circadienne.

Les cyanobactéries sont des microorganismes très étudiés du point de vue de la photosynthèse, de la fixation du carbone, de la fixation de l'azote, de l'évolution des plastes des plantes et de l'adaptation au stress environnemental. Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 est l'une des espèces de cyanobactéries les plus étudiées, car elle peut pousser à la fois de façon autotrophe et hétérotrophe en l'absence de lumière. Elle a été isolée d'un lac d'eau douce en 1968 et est aisément modifiable par l'ADN exogène. Son génome est réparti sur un chromosome de 3,57 Mb, quatre grands plasmides de 120 106 103 et 44 kbp et trois petits plasmides de 5.2.2.4 et 2,3 kbp[3].

L'appareil photosynthétique de Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 est très semblable à celui des plantes. Cet organisme est également capable de mouvements phototactiques. Il peut vivre dans l'obscurité de façon entièrement hétérotrophe mais, pour une raison encore inconnue, il nécessite d'être exposé à un minimum de 5 à 15 minutes de lumière bleue par jour. Ce rôle régulateur de la lumière demeure inchangé chez les souches dépourvues de photosystème I et de photosystème II[4].

Selon ITIS (29 mars 2018)[1] :

Selon NCBI (29 mars 2018)[2] :

Selon World Register of Marine Species (29 mars 2018)[5] :

Synechocystis est un genre de cyanobactéries (autrefois appelées algues bleues) représentées en premier lieu par la souche Synechocystis sp. PCC6803. Cette dernière vit dans l'eau douce et est capable de se développer à la fois de façon phototrophe par photosynthèse oxygénique et de façon hétérotrophe par glycolyse et phosphorylation oxydative. Elle est capable d'anticiper les transitions jour-nuit à l'aide d'une horloge circadienne.

Les cyanobactéries sont des microorganismes très étudiés du point de vue de la photosynthèse, de la fixation du carbone, de la fixation de l'azote, de l'évolution des plastes des plantes et de l'adaptation au stress environnemental. Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 est l'une des espèces de cyanobactéries les plus étudiées, car elle peut pousser à la fois de façon autotrophe et hétérotrophe en l'absence de lumière. Elle a été isolée d'un lac d'eau douce en 1968 et est aisément modifiable par l'ADN exogène. Son génome est réparti sur un chromosome de 3,57 Mb, quatre grands plasmides de 120 106 103 et 44 kbp et trois petits plasmides de 5.2.2.4 et 2,3 kbp.

L'appareil photosynthétique de Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 est très semblable à celui des plantes. Cet organisme est également capable de mouvements phototactiques. Il peut vivre dans l'obscurité de façon entièrement hétérotrophe mais, pour une raison encore inconnue, il nécessite d'être exposé à un minimum de 5 à 15 minutes de lumière bleue par jour. Ce rôle régulateur de la lumière demeure inchangé chez les souches dépourvues de photosystème I et de photosystème II.

Synechocystis è un genere di cianobatterio di acqua dolce, rappresentato principalmente dal ceppo "Synechocystis" sp. PCC6803, in grado di crescere sia in condizioni luminose, eseguendo la fotosintesi ossigenata (fototrofia), sia nell'oscurità, mediante glicolisi e fosforilazione ossidativa (eterotrofia).[1] L'espressione genetica è regolata da un orologio circadiano, quindi l'organismo può effettivamente anticipare le transizioni tra le fasi della luce e dell'oscurità.[2]

I cianobatteri sono procarioti fotosintetici che esistono sulla terra da circa 2700 milioni di anni. La capacità dei cianobatteri di produrre ossigeno è stata la causa della Catastrofe dell'ossigeno.[3] I cianobatteri hanno colonizzato un'ampia varietà di habitat, compresi gli ecosistemi di acqua dolce e salata e la maggior parte degli ambienti terrestri.[4] Filogeneticamente, il Synechocystis si ramifica dall'albero evolutivo dei cianobatteri a partire dalla radice ancestrale (Gloeobacter violaceus).[5] Il Synechocystis, che non è un diazotrofo, è strettamente correlato a un altro organismo modello, il Cyanothece ATCC 51442, che invece lo è.[6] Pertanto, è stato proposto che il Synechocystis originariamente possedesse la capacità di fissare l'azoto atmosferico, ma abbia perso i geni necessari per il processo.[7]

I cianobatteri sono degli organismi modello utilizzati nello studio della fotosintesi, dell'assimilazione di carbonio e azoto, dell'evoluzione dei plastidi vegetali e dell'adattabilità allo stress ambientale. Il Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 è uno dei tipi più studiati di cianobatteri perché può crescere sia autotroficamente che eterotroficamente, se non si verificano condizioni di luce. È stato isolato dall'acqua dolce di un lago nel 1968 e la sua temperatura di crescita ottimale è compresa tra 32 e 38 °C.[8]

Il Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 puoi facilmente assumere DNA esogeno, tramite elettroporazione, trasformazione ultrasonica e coniugazione.[9] Il sistema fotosintetico è molto simile a quello presente nelle piante terrestri. Organismi di questo genere esibiscono anche movimento fototattico.

Il Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 può crescere sia in piastre di agar che in coltura liquida. Il mezzo di coltura più utilizzato è una soluzione salina BG-11.[10] L'ideale pH è compreso tra 7 e 8,5.[1] Una intensità luminosa die 50 µmol fotoni m−2 s−1 risulta la migliore per la crescita.[1] Il gorgogliamento del mezzo con aria arricchita con anidride carbonica (1-2% di CO2) può aumentare il tasso di crescita, ma richiede un buffering aggiuntivo per mantenere il pH.[1]

Normalmente la selezione delle specie "Synechocystis" viene effettuata utilizzando la resistenza agli antibiotici come fattore differenziale. Heidorn et al. nel 2011 determinarono sperimentalmente le concentrazioni ideali di kanamicina, spectinomicina, streptomicina, cloramfenicolo, eritromicina e gentamicina per il ceppo Synechocystis sp. PCC6803.[1] Le colture possono essere mantenute su piastre di agar per circa due settimane e possono essere ridimensionate o mantenute a tempo indeterminato.[10] Per la conservazione a lungo termine, la coltura cellulare liquida deve essere mantenuta in una soluzione di glicerolo al 15% a -80 °C.[10]

Il genoma del Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 è contenuto in 12 copie di un solo cromosoma (3.57 megabasi); tre plasmidi piccoli: pCC5.2 (5.2 kb) pCA2.4 (2.4 kb), y pCB2.4 (2.4 kb); e quattro plasmidi grandi: pSYSM (120 kb), pSYSX (106 kb), pSYSA (103kb), y pSYSG (44 kb).[11][12]

Il ceppo principale di "Synechocystis" sp. è PCC6803. Sono state create modifiche al ceppo PCC6803 originale, in quanto carente di un sub-ceppo fotosistema 1 (PSI).[13] Altro sub-ceppo ampiamente utilizzato del Synechocystis sp. è ATCC 27184, tollerante al glucosio, poiché il PCC6803 non può usare il glucosio.[14]

Il sub-ceppo ATCC 27184 di "Synechocystis" sp. PCC6803, può vivere eterotroficamente in condizioni di oscurità utilizzando il glucosio come fonte di carbonio, ma per ragioni ancora sconosciute richiede un minimo di 5-15 minuti di luce blu al giorno. Questo meccanismo di regolazione della luce rimane invariato nei mutanti senza PSI e PSII.[15]

Alcuni geni glicolitici sono regolati dal gene sll1330 nei mezzi luminosi e con glucosio. Uno dei più importanti geni della glicolisi è quello del fruttosio-bifosfato aldolasi (fbaA). I livelli di MRNA di "fbaA" si incrementano in condizioni di luminosità e integrazione di glucosio.[16]

Il sistema CRISPR-Cas fornisce immunità adattativa a batteri e archaea. Lo Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 contiene tre diversi sistemi CRISPR-Cas: tipo I-D e due versioni di tipo III. Tutti questi sistemi si trovano nel plasmide pSYSA. I cianobatteri nel loro insieme mancano del sistema di tipo II (che è stato recentemente adattato come strumento di ingegneria genetica.[17]

Synechocystis è un genere di cianobatterio di acqua dolce, rappresentato principalmente dal ceppo "Synechocystis" sp. PCC6803, in grado di crescere sia in condizioni luminose, eseguendo la fotosintesi ossigenata (fototrofia), sia nell'oscurità, mediante glicolisi e fosforilazione ossidativa (eterotrofia). L'espressione genetica è regolata da un orologio circadiano, quindi l'organismo può effettivamente anticipare le transizioni tra le fasi della luce e dell'oscurità.