mk

имиња во трошки

Los gimnofiones (Gymnophiona, qu'en griegu significa "culiebra desnuda") o ápodos (Moteya), conocíos vulgarmente como cecilias o cecílidos, son un clado d'anfibios caracterizaos principalmente por presentar un aspeutu vermiforme, tentáculos olfativos y una ausencia d'estremidáes, cintura coxal y cintura escapular.[1] Habiten namái nes rexones tropicales húmedes, esibiendo un estilu de vida fosorial al vivir sol suelu, ente que delles especies son secundariamente acuátiques. Atópase n'América, África, la India, Indochina y dalgunes otres rexones que formaron parte de Gondwana mientres el Mesozoicu.[2] Los rexistros más antiguos de gimnofiones correspuenden al holotipo de Eocaecilia micropodia del Xurásicu Inferior[3] y a Rubricacaecilia del Cretácicu Inferior[4] Anguaño conócense 204 especies vives de cecilias.[5]

Les cecilias presenten tamaños que van dende los 98-104 mm nos adultos de la especie Idiocranium russeli, hasta 1,5 m en Caecilia thompsoni.[6]

Tienen un cuerpu elongado compuestu por unes 200 vértebres y una cola bien corta nel casu de les especies del grupu Rhinatrematidae, nes cualos, de la mesma, la boca ta alcontrada na rexón anterior del craniu, carauterística ausente nel restu de les families. Nun presenten cintura coxal, cintura escapular nin estremidáes, tando'l cuerpu entamáu n'aniellos denominaos annuli (dándo-yos un aspeutu similar a los viermes), que pueden tar estremaos n'aniellos secundarios o terciarios, considerándose felicidá carauterística como plesiomórfica (primitiva).[1]

Les cecilias comparten una cabeza esplanada, altamente osificada y con pequeños güeyos rudimentarios, en dellos casos atrofiaos o cubiertos de piel. Esto paecería indicar que la so función ye solo la de percibir la lluz. La piel, pela so parte, ye llisa y con riegos tresversales, siendo la de la de la rexón cefálica llisa y bien dura, esto por cuenta de qu'en les capes más internes atópase fundida col craniu. Esta carauterística déxa-yos buscar y apalpar cola cabeza na so redolada, amás de cavar con ella ensin que la piel esprender. Tienen tamién dos estructures protráctiles asitiaes a los llaos de la cabeza, ente la ñariz y el güeyu. Estos apéndices, denominaos tentáculos, déxen-yos detectar golores, siendo únicos ente los vertebraos. El quexal asítiase na parte inferior de la so cabeza, lo cual evita l'ingresu de tierra mientres caven. Tienen amás pequeños dientes proxectaos escontra tras, lo cual facilita la captura de les preses.

Al igual que nes culiebras, les anfisbenes y les sacaveres, los órganos internos de les cecilias son elongados, tando unu o los dos pulmones amenorgaos y xeneralmente l'esquierdu ausente, anque la especie Atretochoana eiselti escarez de dambos.[7][8]

La cecilias presenten una fertilización interna (con un periodu llarval que suel durar ente 10 y 12 meses[6]), siendo amás ovovivípares (anque la mayoría tien cucharapes nadadores[2]) y dándose casos en que les bárabos siguen desenvolviéndose nel oviducto o canal sexual, alimentándose de secreciones del cuerpu maternu funcionalmente equivalentes a la lleche. Tamién esisten cecilias totalmente ovípares, y nesi casu les femes enrósquense alredor de los güevos pa protexelos. Na especie Boulengerula taitanus, que ye reinal de Kenia, haise documentáu una forma de cuidáu parental na cual la fema alimenta a la prole cola so piel, que ye rica en nutrientes.[9][10]

En comparanza con otros anfibios, poco se sabe de les cecilias, yá que la so vida soterraña caltener escondíes. La mayoría viven nos llechos de fueyes y nel suelu blandu de les selves tropicales, anque delles especies lleven una vida acuática, buscando comida mientres apalpen el llechu d'estanques y ríos cola so cabeza. Como tolos anfibios, les cecilias adultes son carnívores, anque la so dieta depende del so tamañu: les más pequeñes comen inseutos, arañes, ciempiés, merucos y viermes, pero les especies más grandes alimentar de xaronques, royedores, llagartos y culiebras.

Al ser tan escasu'l rexistru fósil de les cecilias, poco se sabe sobre'l so historia evolutiva. Mientres enforma tiempu una vértebra afayada en Brasil, que data del Paleocenu, yera l'únicu rexistru col que se cuntaba. Nun foi hasta 1972 qu'esti rexistru estendióse dramáticamente al afayase en Arizona (Estaos Xuníos) un espécime del Xurásicu Inferior, que foi nomáu más tarde como Eocaecilia micropodia.[11][3] Eocaecilia tenía carauterístiques de les cecilias modernes (Moteya) nel craniu y nel cuerpu elongado, pero a diferencia d'estes presentaba estremidaes y güeyos bien desenvueltos.[12]

Los primeros estudios moleculares de les rellaciones filoxenétiques de les cecilias con al respective de les xaronca y les sacaveres, sofitaben una rellación cercana ente estes postreres y les cecilias (grupu denomináu Procera).[13][14][15] Esta hipótesis ayudaba a esplicar el patrones de distribución y el rexistru fósil de los anfibios modernos, dáu'l fechu de que les xaronques tán distribuyíes en casi tolos continentes ente que les sacaveres y les cecilias presenten una bien marcada distribución en rexones que dalguna vegada formaron parte de Laurasia y Gondwana respeutivamente. Los rexistros fósiles más antiguos de xaronques (y de lisanfibios) daten del Triásicu Inferior (~250 Ma) de Madagascar (correspondiendo al xéneru Triadobatrachus[16]), ente que los de les sacaveres y les cecilias correspuenden al periodu Xurásicu (~190 Ma). Sicasí, los analises posterior y recién nos que s'ocuparon grandes bases de datos tantu de xenes nucleares como mitocondriales, o una combinación de dambos, establecen a les xaronques y les sacaveres como grupos hermanos, que'l so clado ye denomináu Batrachia.[17][18] Esti grupu ye reafitáu por estudios de datos morfolóxicos (incluyendo'l de especímenes fósiles).[19][20][21]

Per otra parte, los primeros analises filoxenéticos de les rellaciones ente les cecilias, adoptaron datos morfolóxicos y sobre la bioloxía d'estes, que fueron, na so mayoría, acotaos polos estudios moleculares posteriores.[22][23][24][25][26][27] Anguaño reconócense 10 families de cecilias modernes, que les sos rellaciones filoxenétiques descríbense de siguío:

Cladograma basáu na filoxenia molecular más recién per San Mauro et al. (2014).[27]

=== Families reconocen les siguientes families y númberu d'especies:[5]

Amás, reconozse la familia estinguida Eocaeciliidae Jenkins & Walsh, 1993.

Los gimnofiones (Gymnophiona, qu'en griegu significa "culiebra desnuda") o ápodos (Moteya), conocíos vulgarmente como cecilias o cecílidos, son un clado d'anfibios caracterizaos principalmente por presentar un aspeutu vermiforme, tentáculos olfativos y una ausencia d'estremidáes, cintura coxal y cintura escapular. Habiten namái nes rexones tropicales húmedes, esibiendo un estilu de vida fosorial al vivir sol suelu, ente que delles especies son secundariamente acuátiques. Atópase n'América, África, la India, Indochina y dalgunes otres rexones que formaron parte de Gondwana mientres el Mesozoicu. Los rexistros más antiguos de gimnofiones correspuenden al holotipo de Eocaecilia micropodia del Xurásicu Inferior y a Rubricacaecilia del Cretácicu Inferior Anguaño conócense 204 especies vives de cecilias.

Suda-quruda yaşayan ayaqsızlar (lat. Gymnophiona, Apoda) — onurğalı heyvanların Suda-quruda yaşayan sinfinə daxil olan dəstə. Ayaqsızlar suda-quruda yaşayanların cəmi 170 növünü özündə birləşdirən ən kiçik dəstəsidir.

Suda-quruda yaşayan ayaqsızlar (lat. Gymnophiona, Apoda) — onurğalı heyvanların Suda-quruda yaşayan sinfinə daxil olan dəstə. Ayaqsızlar suda-quruda yaşayanların cəmi 170 növünü özündə birləşdirən ən kiçik dəstəsidir.

Les cecílies, gimnofions o àpodes (Gymnophiona o Apoda) són un ordre de lissamfibis. L'altre ordre de lissamfibis existents són els amfibis. Les cecílies es caracteritzen per haver sofert una pèrdua secundària de les seves potes, cosa que els dóna una aparença de serp, però no són ni serps ni amfibis. En la classificació clàssica s'incloïa a les cecílies en els amfibis. En la classificació filogenètica moderna les cecílies i els amfibis són els dos clades germans que, tot dos junts, constitueixen els lissamfibis. Actualment existeixen 205 espécies.[1]

Segons el Sistema Integrat d'Informació Taxonòmica:

Segons Animal Diversity Web:

Les cecílies, gimnofions o àpodes (Gymnophiona o Apoda) són un ordre de lissamfibis. L'altre ordre de lissamfibis existents són els amfibis. Les cecílies es caracteritzen per haver sofert una pèrdua secundària de les seves potes, cosa que els dóna una aparença de serp, però no són ni serps ni amfibis. En la classificació clàssica s'incloïa a les cecílies en els amfibis. En la classificació filogenètica moderna les cecílies i els amfibis són els dos clades germans que, tot dos junts, constitueixen els lissamfibis. Actualment existeixen 205 espécies.

Červoři (Gymnophiona) čili beznozí (Apoda) jsou jeden z řádů obojživelníků, s protáhlým červovitým tělem s redukovanými končetinami. Žijí většinou skrytě v chladném a vlhkém prostředí v půdě.

Řád červorů (recentních) se dělí na deset čeledí:[1][2]

Červoři zcela postrádají končetiny, čímž mohou připomínat červy nebo žížaly, případně hady. Mohou dosahovat délky až 1,5 metru. Ocasní část je krátká, kloaka je umístěna u konce těla. Kůže červorů je hladká, většinou tmavá, ale některé druhy jsou i barevné. Po celém těle mívají páskovitý vzor. Mají i šupiny z uhličitanu vápenatého.

Jsou téměř slepí, protože žijí pod povrchem půdy ve tmě. Vnímají jen světlo a tmu. Na hlavě mají dvě drobná tykadla, která pravděpodobně slouží jako druhý orgán čichu, společně s nosem. Pro život pod zemí jsou opatřeni tvrdou špičkou čenichu [zdroj?], která funguje jako rýč.

Mimo jednu výjimku (Atretochoana eiselti) mají všichni červoři plíce, ale k dýchání používají rovněž kůži (kožní dýchání). Levá plíce bývá menší než pravá, čímž se přizpůsobují červoři svému úzkému tvaru těla (podobně je tomu např. u hadů)

Červoři jsou jedinou skupinů obojživelníků s výhradně vnitřním oplozením. Samci mají penisovitý orgán (phallodeum, vychlípitelný konec střeva), který při oplození vkládají do samičí kloaky na 2–3 hodiny.

Červoři mohou být vejcorodí (25 % druhů) i živorodí (75 %). Samice vejcorodých červorů kladou vejce do vlhkého prostředí a samice je hlídají (péče o potomstvo). Živorodé druhy se vyvíjí v těle samice a živí se speciálními buňkami samice. Líhnou se larvy, které většinou žijí u vody či ve vlhku, někdy ale rovnou metamorfovaní dospělci.

V tomto článku byl použit překlad textu z článku Caecilian na anglické Wikipedii.

Červoři (Gymnophiona) čili beznozí (Apoda) jsou jeden z řádů obojživelníků, s protáhlým červovitým tělem s redukovanými končetinami. Žijí většinou skrytě v chladném a vlhkém prostředí v půdě.

Ormepadderne (Gymnophiona) er den dårligst udforskede orden indenfor padderne. Det skyldes bl.a. at de lever deres liv under jorden eller i vand.

Ormepadder har ingen ben.

De findes i Afrika, det sydøstlige Asien og Amerika.

Orden: Gymnophiona

Ormepadderne (Gymnophiona) er den dårligst udforskede orden indenfor padderne. Det skyldes bl.a. at de lever deres liv under jorden eller i vand.

Ormepadder har ingen ben.

Die Schleichenlurche (Gymnophiona, Apoda) oder Blindwühlen bilden mit etwa 200 Arten[1] die kleinste Ordnung in der Klasse der Lurche (Amphibia). Sie sind trotz der Bezeichnung Blindwühlen weder vollkommen blind noch wühlen alle Arten im Boden.

Schleichenlurche besitzen keine Gliedmaßen, auch der Schwanz ist stark reduziert. Die Kloake befindet sich am hinteren Ende des Körpers, welches dem Vorderende oft ähnelt. Kleine Schleichenlurche (um 10 Zentimeter Länge) können leicht mit Regenwürmern verwechselt werden, große Arten (etwa 1 bis 1,6 Meter Länge) erscheinen schlangenartig.

Die Haut der Schleichenlurche ist glatt und oft mattdunkel gefärbt. Manche Arten haben farbige Streifen oder Flecken an den Seiten. Früher wurden sie aufgrund in der Haut eingelagerter Kalkschuppen und wegen der zusammengewachsenen Schädelknochen als mit den ausgestorbenen Panzerlurchen verwandt angesehen; heute werden diese Eigenschaften aber als sekundäre Anpassungen interpretiert. Kiefer und Gaumen tragen Zähne.

Der alternative Name, Blindwühlen, ist von den oft zurückgebildeten und von Haut abgedeckten Augen abgeleitet, die daher nur einfache Hell-Dunkel-Kontraste sehen können. Die Wahrnehmung geschieht hauptsächlich durch Riechen und mit zwei zwischen Nase und Augen liegenden Fühlern. Auch Bodenvibrationen spielen eine Rolle bei der Orientierung. Die Atmung findet durch den rechten Lungenflügel statt, während der linke in der Regel zurückgebildet ist. Auch über die Haut und die Mundschleimhaut findet der Gasaustausch statt, insbesondere auch bei den lungenlosen Blindwühlen. Von Letzteren sind jedoch keine Beobachtungen am lebenden Tier bekannt, auch wenn 2010 zu der nur in zwei konservierten Exemplaren bekannten Atretochoana eiselti[2] noch eine weitere Art aus Venezuela bekannt wurde.[3]

Schleichenlurche kommen in den Tropen und Subtropen Südostasiens, Afrikas sowie Mittel- und Südamerikas vor. Sie halten sich in der Regel in den oberen Boden- und Streuschichten von Wäldern auf und leben von Kleintieren, insbesondere Regenwürmern. Sie ziehen feuchte Gebiete, oft in der Nähe von Gewässern, vor. Schwimmwühlen, die sich ganz an das Leben im Wasser angepasst haben, kommen in langsam fließenden Flüssen wie dem Amazonas, Orinoko und in den kolumbianischen Flusssystemen vor.

Aufgrund ihrer verborgenen Lebensweise sind die Schleichenlurche eine wenig bekannte Amphibiengruppe. Zoologen gehen davon aus, dass noch nicht alle Arten beschrieben sind.

Die Besamung findet im Körperinneren des Weibchens statt. Das Männchen besitzt ein aus der Kloake ausfahrbares Begattungsorgan zur Spermienübertragung, das so genannte Phallodeum.

Es gibt eierlegende Arten, aber etwa 75 % der Arten sind lebendgebärend. Die Jungtiere schlüpfen im Mutterleib und werden im Eileiter ernährt, bevor sie geboren werden. Die Tragzeit der Weibchen kann bis zu 10 Monate betragen. Die eierlegenden Arten legen die Eier in Erdhöhlen an Land ab. Die Eiablagestellen benötigen eine ganz bestimmte Feuchtigkeit und Substrat, die Muttertiere müssen oft lange Strecken bis zu den geeigneten Plätzen wandern. Auch während der Paarungszeit bewegen sich Blindwühlen mehr über Land, meist nachts und bei Regen. Bei einigen Arten ist Brutpflege bekannt; in den ersten zwei Monaten dient dabei die Haut der Mutter als Nahrung.[4] Die Jungtiere leben amphibisch – zur nächtlichen Jagd sind sie im Wasser, am Tage halten sie sich vergraben im Uferbereich auf.

Blindwühlen sind in der Mehrzahl spezialisierte Regenwurm-Jäger. Erdwühlende Blindwühlen finden sich nur dort, wo auch Regenwürmer im Boden vorkommen. Dazu muss eine konstante Feuchtigkeit im Boden vorhanden sein, an Stellen mit größerer Trockenheit findet man sie nicht. Allerdings können sie sich zusammen mit den Regenwürmern in der Trockenzeit tief in den Boden zurückziehen. Die Mägen der Spezies Afrocaecilia taitana enthielten Kopfkapseln von Termiten, jedoch war der größte Teil des Mageninhalts nicht näher bestimmbares organisches Material. Manche Arten fressen auch Insektenlarven, Puppen der Termiten und Ameisen – adulte Termiten und Ameisen sind jedoch als Beute zu schnell. Die wasserlebenden Schwimmwühlen (Typhlonectes) sind auch Aasfresser und helfen bei der Beseitigung verstorbener Fische und Mollusken, lebende Fische können sie jedoch nicht erbeuten. Ihre Hauptbeute im Wasser sind jedoch Würmer und andere Weichtiere. Sie lassen sich im Biotop leicht mit toten Fischen anlocken. Die brasilianisch-argentinischen Sumpfwühlen (Chthonerpeton) sind ein Mittelding zwischen wasserlebenden Schwimmwühlen und den erdwühlenden Arten.

Wie Studien von Thomas Kleinteich von der Universität Jena belegen, erreichen Blindwühlen ein erstaunliches Alter. Bereits die lange Tragzeit von bis zu 10 Monaten und das späte Erreichen der Fortpflanzungsfähigkeit mit 10–12 Jahren deuten darauf hin, dass das Adultstadium lange dauern kann – man schätzt, dass die größeren Arten an die 80 Jahre alt werden können – falls sie nicht vorher einem Feind zum Opfer fallen. Blindwühlen haben wenig Feinde, viele Arten schützen sich zudem mit giftigen Hautsekreten. Wie Daniel Hofer nachweisen konnte, besitzt etwa die Westafrikanische Buntwühle (Schistometopum) ein wirksames Hautgift, das andere Wirbeltiere im selben Behälter innerhalb von 2 Tagen versterben lässt. Als spezialisierte Blindwühlenjäger sind einige erdwühlende Schlangen bekannt, etwa die ostasiatische Walzenschlange (Cylindrophis).

Während der bis zu 10-jährigen Jugendphase finden nach und nach erhebliche körperliche Veränderungen statt. Dies mag dazu geführt haben, dass verschiedene Jugendphasen in der Vergangenheit als eigene Arten beschrieben wurden. Speziell bei Arten, von denen heute nur ein bis zwei Exemplare bekannt sind, müssen genetische Abklärungen noch nachprüfen, ob es sich um eigene Arten oder lediglich um Jugendphasen einer bekannten Art handelt.

Die Rhinatrematidae stehen als ursprünglichste Familie allen anderen Familien als Schwestergruppe gegenüber. Die wahrscheinliche Verwandtschaft der Familien zueinander, ermittelt mit Hilfe von DNA-Sequenzierung, zeigt folgendes Kladogramm:[5]

Die Schleichenlurche werden in zehn Familien eingeteilt und manchmal nach ihrem Entwicklungsstand gruppiert.

Die genaue Anzahl der Gattungen und Arten innerhalb der einzelnen Familien schwankt je nach Autorität, insbesondere, weil viele Arten nur durch ein einziges Belegexemplar beschrieben sind.

Fossil waren Schleichenlurche bis 1993 nur durch zwei fossile Wirbel aus der Oberkreide von Bolivien und dem Paläozän von Brasilien bekannt. 1993 wurde schließlich Eocaecilia beschrieben, ein Schleichenlurch aus dem Unterjura, der noch vier kurze Extremitäten mit jeweils drei Zehen hatte.[6] Noch älter ist Chinlestegophis. Die Gattung gehört zur Stammgruppe, die zu den Schleichenlurchen führt und lebte im heutigen Nordamerika im Trias. Die Fossilien wurden in der Chinle-Formation gefunden. Der Schädel von Chinlestegophis zeigt einen Merkmalsmix zwischen den heutigen Schleichenlurchen und den Stereospondyli, einer Gruppe der Temnospondyli und gilt damit als Hinweis darauf, dass die heutigen Amphibien aus den Temnospondyli hervorgegangen sind.[7]

Die Schleichenlurche (Gymnophiona, Apoda) oder Blindwühlen bilden mit etwa 200 Arten die kleinste Ordnung in der Klasse der Lurche (Amphibia). Sie sind trotz der Bezeichnung Blindwühlen weder vollkommen blind noch wühlen alle Arten im Boden.

The caecilians are an order (Gymnophiona) o amphibians that superficially resemble yirdworms or snakes. Thay maistly live hidden in the grund, makin them the least familiar order o amphibians. Aw extant caecilians an thair closest fossil relatives are grooped as the clade Apoda. Thay are maistly distributit in the tropics o Sooth an Central Americae, Africae, an Sooth Asie. The diets o caecilians are nae well kent.

Gymnophiona es un ordine de Lissamphibia, Amphibia.

L'òrdre dels gimnofiones foguèt creat per Johannes Peter Müller (1801-1858) en 1832. Son tanben apelats Apòdes.

Los gimnofiònes son de lissanfibians escavaires qu'an perdut segondàriament lors membres. Segon las espècias, la talha varia entre 6 cm e 1,40 m. Vivon dins l'umús o la fanga dels paluns dins los bòsques entre los tropics mas son absents d'Austràlia, de Madagascar e de las Antilhas. Son generalament carnivòrs. La fecondacion es intèrna. Segon los genres, son ovipars (Ichthyopsis) o vivipars (Typhlonectes).

Lor pèl es viscosa, amb de secrecions toxicas e empudesinadas.

Caeciliidae | Ichthyophiidae | Rhinatrematidae | Scolecomorphidae | Typhlonectidae | Uraeotyphlidae

L'òrdre dels gimnofiones foguèt creat per Johannes Peter Müller (1801-1858) en 1832. Son tanben apelats Apòdes.

Los gimnofiònes son de lissanfibians escavaires qu'an perdut segondàriament lors membres. Segon las espècias, la talha varia entre 6 cm e 1,40 m. Vivon dins l'umús o la fanga dels paluns dins los bòsques entre los tropics mas son absents d'Austràlia, de Madagascar e de las Antilhas. Son generalament carnivòrs. La fecondacion es intèrna. Segon los genres, son ovipars (Ichthyopsis) o vivipars (Typhlonectes).

Lor pèl es viscosa, amb de secrecions toxicas e empudesinadas.

Nyoka wanafiki ni wanyama wa oda Gymnophiona katika ngeli Amfibia wafananao na nyoka au nyungunyungu wakubwa. Wanyama hawa si nyoka au nyungunyungu kwa ukweli na hata si Reptilia au Annelida. Wana mnasaba na salamanda na vyura lakini hawana miguu. Mkia wao ni mfupi sana au umetoweka, kwa hivyo kloaka iko karibu na mwisho wa mwili. Hupitisha maisha yao yote wakichimba ardhini lakini spishi za familia Typhlonectidae huishi majini na zina aina ya pezi juu ya sehemu ya nyuma ya mwili ambayo inazisaidia kwenda mbele majini. Macho ya nyoka wanafiki ni wadogo na yamefunika kwa ngozi. Kwa hivyo hawawezi kuona vizuri lakini wanaweza kutambua baina ya nuru na giza. Wanyama hawa wanatokea katika mahali pa majimaji pa tropiki kama Afrika, Asia ya Kusini-Mashariki na Amerika ya Kati na ya Kusini.

Nyoka wanafiki hawana ndubwi kama salamanda au vyura. Spishi chache tu (±25%) hutaga mayai, nyingine huzaa wana wanaofanana na wazazi wao. Hata watagamayai takriban wote hutoka mayai kama nyoka wadogo. Spishi chache tu zina wana wanaofanana na ndubwi wenye matamvua na hata hawa hawaishi majini lakini katika udongo chepechepe karibu na maji, isipokuwa wale wa Typhlonectidae.

Nyoka wanafiki ni wanyama wa oda Gymnophiona katika ngeli Amfibia wafananao na nyoka au nyungunyungu wakubwa. Wanyama hawa si nyoka au nyungunyungu kwa ukweli na hata si Reptilia au Annelida. Wana mnasaba na salamanda na vyura lakini hawana miguu. Mkia wao ni mfupi sana au umetoweka, kwa hivyo kloaka iko karibu na mwisho wa mwili. Hupitisha maisha yao yote wakichimba ardhini lakini spishi za familia Typhlonectidae huishi majini na zina aina ya pezi juu ya sehemu ya nyuma ya mwili ambayo inazisaidia kwenda mbele majini. Macho ya nyoka wanafiki ni wadogo na yamefunika kwa ngozi. Kwa hivyo hawawezi kuona vizuri lakini wanaweza kutambua baina ya nuru na giza. Wanyama hawa wanatokea katika mahali pa majimaji pa tropiki kama Afrika, Asia ya Kusini-Mashariki na Amerika ya Kati na ya Kusini.

Sésilia, Gymnophiona, utawa Apoda ya iku ordho amfibia kang awaké kaya cacing gedhé utawa ula. Kéwan iki kalebu kéwan kang langka banget. kajaba amarga mung tinemu ing tlatah alas-alas kang isih apik, sesilia urip ing njero lemah kang mawur, ing sacedhaké kali utawa rawa, saéngga isih jarang banget tinemu déning manungsa. Ing basa Jawa, sesilia diarani ulo duwél.[2]

Sesilia ora duwé sikil babar blas, saéngga jinis kang cilik mèmper kaya caccing lan kang gedhé kang dawané 1,5 m kaya ula. Buntuté cendhak utawa malah ora ana lan kloakané cedhak ing pucuking awak.

Kulité lus awerna peteng ora mengkilap, nanging sawatara jinis ana kang warna-warni. Ing jero kulit ana sisik saka kalsit. Amarga sisik iki, sesilia tau dianggep sakaluwarga karo fosil Stegocephalia. Nanging saiki babgan iku dipracaya amarga ana perkembangan sekunder lan golongan loro iku ora mungkin sakulawarga.

Kulité uga nduwé akèh lapisan bantuké ali-ali, kang sapérangan nutupi awaké. Saéngga sesilia katon nduwé ros-ros. Kayata amfibia liyané, ing kulité ana klanjer kang nyekresi racun kanggo nundhung pemangsa.[1] Sekresi kulit Siphonops paulensis wis dituduhaké duwé sipat hemolisis.[3]

Anatomi sesilia bisa adhaptasi ing panguripan ing lemah. Tengkoraké kuwat kanthi moncong kang lancip kanggo ngesuk dalan lumantar lemah utawa lendhut. Ing akèh spésies, gunggungé balung ing cumplung kereduksi lan nyawiji bareng, lambéné ana ing pérangan ngisor sirah. Ototé keadaptasi kanggo ngesuk dalan lumantar lemah, kanthi rangksa lan otot kang minangka piston ing jero kulit lan otot njaba. Babagan bisa waé ndadèkaké kwéan iki nambataké pucuk mburiné ing panggonan, lan ngesuk sirah tumuju ngarep, banjur narik pérangan awak liyané kanggo tekan ing gelombang. Ing banyu utawa lendhut kang cuwèr banget, sesilia nglangi kaya welut.[1] Sesilia famili Typhlonectidae hidup di air dan juga sesili terbesar. Wakil famili ini punya sirip berdaging di sepanjang pérangan belakang tubuhnya, yang menambah kemampuan mendorong di air.[4]

Kabèh sesilia, kajaba kang paling primitif, nduwé perangkat otot loro kanggo nutup rahang kang ana ing vertebrata liya ana sepasang. babagan iki luwih ngrembaka manèh ing sesilia kang manggon ing lemah efisien lan manawa mbantu cumplung lan rahangé tetep kaku.[1]

Amarga urip ing ngisor lemah, mripat sesilia ukurané cilik lan ditutupi kulit kang ngayomi ing endi babagan iki nggawé salah pangertèn bilih sesilia iku wuta. prekara iki ora mesthi bener, sandyan pandelengé kebates mung ing antarané mripat lan bolongan irung. Tentakel iki bisa minangka kemampuan ngambu kang kapindho, kajaba indera normal ing irungé.[1]

Kajaba spesie kang ora nduwé paru-paru Atretochoana eiselti kang mung dimangertèni saka spésimèn loro kang diklumpukaké ing Amérika Kidul, kabèh sesilia nduwé paru-paru nanging uga nggunakaké kulit lan lambéné kanggo nyerep oksigèn. Paru-paru kiwa luwih cilik tinimbang paru-paru sisih tengen, babagan iki amarga salah sawijining adhaptasi wujud awak kang uga tinemu ing ula.

Sesilia tinemu ing akh wewengkon tropis ing Asia Tenggara, Afrika, lan Kepuloan Seychelles, lan Amérika Kidul kajaba ing tlatah garing lan pagunungan dhuwur. Ing Amérika Kidul panyebaran sesilia uga tambah amba ing tlatah sejuk ing sisih lor Argentina. Sesilia bisa tinemu menyang kidul ngantu tekan Buenos Aires, saiki sesilia kagawa banjir Kali Parana adoh ing sisih lor. Ora ana studi babagan sesilia ing Afrika Tengah, nangiing sesilia manawa bisa ana ing las tropis ing kana. Sebaran paling lor ya iku spésies Ichthyophis sikkimensis ing India Lor. Ing Afrika, sesilia tinemu saka Guinea Bissau (Geotrypetes) nganti Zambia lor (Scolecomorphus). Ing Asia Tenggara, panyebaran sesilia ora nyebrangi garis Wallace, sesilia uga ora tinemu ing Australis utawa pulo-pulo ing tlatah mau. Ichthyophis uga tinemu ing Cina Kidul lan Vietnam lor. Sesilia uga tinemu ing Selandia Baru. [5].

Miturut Djoko T. Iskandar ing bukuné Amfibi Jawa dan Bali (1998), sesilia tinemu ing Indonesia kagolong kalebu ing rong génus, ya iku génus Caudacaecilia kang nyebar ing kalimantan lan Sumatera, lan génus Ichthyophis kang tinemu ing Kalimantan, Sumatera, lan jawa.[6]

Sesilia ya iku siji-sijiné ordho amfibi kang pembuahané internal. Sesilia lanang duwé organ kaya penis, diarani phallodeum kang dilebokaké ing kolaka wadon suwéné 2 nganti 3 jam. Watara 25% spésies sesilia ovipar (ngnedhog), endhogé iku dijaga déning kang wadon. Ing sawatara spésies, sesilia wis ngalami metamorfosis nalika netes, kang liyané netes dadi larva. Larvané ora kabèh bisa urip ung banyu, nanging ngentèkaké wektuné ing lemah cedhak banyu.[1]

75% spésies vivipar, kang tegesé nglairaké anak kang wis tumuwuh. Janin diwènèhi panganan ing jero awak wadon saka sèl-sèl oviduk, kang dipangan nganggo untu kang mligi kanggo nyepeng.

Spesies Boulengerula taitanus kang ngedhog mènèhi panganan anaké kanthi ngembangaké lapisan njaba kulit kang kaya lemak lan nutrisi kang dikuliti anaké nganggo untu kang padha. Babagan iki bisa waé ndadèkaké sesilia tuwuh tikel sepuluh boboté ing wektu seminggu. Kulit iku dipangan saben telung dina, wektu kang diprelokaké lapisan anyar kanggo thukul, lan anak iku dimati namung mangan ing wayah bengi. Biyèn anak enom iku dianggep urip saka cuwèran sekresi saka ibuné.[7]

Sawetara larva kaya larva Typhlonectes, lair kanthi angsang njaba kang gedhé kang amèh coplok. Ichthyophis ngendhog lan dimangertèni nuduhaké sipat ngrumati anak kanthi ibuné kang njaga endhog-endhogé nganti netes.

Sesilia seneng panggonan-panggonan kang teles lan anyep. Pinggir-pinggir kali utawa peceren, ing ngisoré tumpukan watu, kayu, utwa serasah kang katumpuk-tumpuk, ing cedhak kolam utawa rawa. Panganan sesilia ora patia dimangertèni, sanadyan katon kawangun saka gegremet lan invertebrata kang tinemu ing saben habitat. isi weteng 14 spesium Afrocaecilia taitana kawangun saka bahan organik lan tetuwuhan kang ora bisa ditemtokaké, Ing endi-endi sisa-sisa kang bisa dikenali paling akèh kang paling akèh tinemu ya iku sirah rayap.[8] Sanadyan diprakirakaké bilih bahan organik ora mesthi iku nuduhaké bilih sesilia mangan detritus, ya iku sisa-sisané cacing lemah.

Panganané wujud gegremet, cacing lan ula kawat (Typhlops). Ing jero tangkaran, sesilia gelem mangan laler kang dipatèni utawa dilumpuhaké lan dikepyuraké ing jero kandhangé.

Jeneng sesilia asalé saka basa Latin caecus = buta, ngrujuk ing mripaté kang cilik utawa ora ana. Jeneng iku asalé saka jeneng taksonomis saka spésies sepisanan kang didhèskripsikaké Carolus Linnaeus kang banjur dijenengi Caecilia tentaculata. Jeneng taksonomis ordho iki asalé saka basa Yunani γυμνος (gymnos, telanjang) lan οφις (ophis, ula), amarga wiwitané sesilia dianggep sakulawarga karo ula.

Miturut taksonomis sesilia dipérang dadi 6 familia. cacah spésies rata-rata siji spésimèn. Mahè mesthi bilih ora kabèh spésies wis bisa didhèskripsikaké lan bilih sawatara spésies kang didhèskripsiké ing ngisor iki minangka spésies kang béda nalika dipadhakaké dadi siji spésies pengklasifikasian ulang mengko.

Saka telung jinis kang wis tau dilapuraké saka jawa, ya iku Ichthyophis hypocyaneus Boie (1827), I. javanicus Taylor (1960) dan I. bernisi Salvador (1975), Iskandar (1998) nyebutaké bilih mung I. hypocyaneus kang ngyakinaké, lan dianggep siji-sijiné jinis sesilia ing Jawa.

Sithik kang dimangertèni babagan sujarah evolusi sesilia, kang amèh ora ninggal cathetan fosil. kang diprakirakaké saka sithik fosil iku ya iku bilih fosil-fosil iku mung sithik kang malih yutanan taun suwéné. Fosil kang paling dhisik dimangertèni asalé saka periode Jurasik. Genus primitif iki, Eocaecilia, duwé sikil cilik lan mripat kang tumuwuh apik.

Sésilia, Gymnophiona, utawa Apoda ya iku ordho amfibia kang awaké kaya cacing gedhé utawa ula. Kéwan iki kalebu kéwan kang langka banget. kajaba amarga mung tinemu ing tlatah alas-alas kang isih apik, sesilia urip ing njero lemah kang mawur, ing sacedhaké kali utawa rawa, saéngga isih jarang banget tinemu déning manungsa. Ing basa Jawa, sesilia diarani ulo duwél.

Tapyamach'aqway, kichwapi Tapyamachakuy[1] (ordo Gymnophiona) nisqakunaqa kuruman rikch'akuq allpa yaku kawsaq uywakunam. Kurukunatam mikhunku.

Tapyamach'aqway, kichwapi Tapyamachakuy (ordo Gymnophiona) nisqakunaqa kuruman rikch'akuq allpa yaku kawsaq uywakunam. Kurukunatam mikhunku.

Бутсуздар (Apoda) - Жерде сууда жашоочулардын ичинен бутсуздар өзгөчө айырмаланып турат. Денеси узун, сөөлжан сымал денеси жыйрылып кыймылга келет, буттары жок. Бул түркүмгө кирүүчүлөрдүн өкүлдөрүнүн денелери жумшак, жылаңач, тулку бою былжырак илээшкен тунук былжыр зат менен капталган. Бул түркүмдүн өкүлдөрү бир урууга киришет, 60 ашыгыраак түрү бар. Көбүнчө Түштүк Америкада, тропика же Африкада жана Түштүк Азияда таралган. Көрүнүктүү өкүлү шакек сымал червиянын дене уз. 50 смге жетет. Көбөйүү учурунда эркектери ургаачыларын уруктандырат. Жумурткасын сууга жакын жердеги ийинине тууйт. Жумурткасы 20-30га чейин болот. Ургаачысы жумурткасын басып чыгаруу учурунда кургатпас үчүн сыртынан оролуп курчап алып, денеси былжыр бездерди бөлүп чыгарып турат. Чегилип чыккан личинкалары сууга кирип, сууда өөрчүүсүн аяктайт. Б-дын өкүлдөрү кумурскалар жана алардын личинкалары менен азыктанат.

Бутсуздар (Apoda) - Жерде сууда жашоочулардын ичинен бутсуздар өзгөчө айырмаланып турат. Денеси узун, сөөлжан сымал денеси жыйрылып кыймылга келет, буттары жок. Бул түркүмгө кирүүчүлөрдүн өкүлдөрүнүн денелери жумшак, жылаңач, тулку бою былжырак илээшкен тунук былжыр зат менен капталган. Бул түркүмдүн өкүлдөрү бир урууга киришет, 60 ашыгыраак түрү бар. Көбүнчө Түштүк Америкада, тропика же Африкада жана Түштүк Азияда таралган. Көрүнүктүү өкүлү шакек сымал червиянын дене уз. 50 смге жетет. Көбөйүү учурунда эркектери ургаачыларын уруктандырат. Жумурткасын сууга жакын жердеги ийинине тууйт. Жумурткасы 20-30га чейин болот. Ургаачысы жумурткасын басып чыгаруу учурунда кургатпас үчүн сыртынан оролуп курчап алып, денеси былжыр бездерди бөлүп чыгарып турат. Чегилип чыккан личинкалары сууга кирип, сууда өөрчүүсүн аяктайт. Б-дын өкүлдөрү кумурскалар жана алардын личинкалары менен азыктанат.

சிறுகண் காலிலி (Caecilian) காலிலி குடும்பத்தை சேர்ந்த ஒரு நிலநீர் வாழ்வன ஆகும். இது மூன்று நீலநீர் வாழ் குடும்பங்களில் ஒன்றாகும், மற்ற இரண்டு குடும்பங்கள் தவளை, / தேரை குடும்பம் மற்றும் நிலநீர் வாலுயிரி குடும்பமாகும். இவை மண் புழு அல்லது பாம்புகளின் உருவத்தை ஒத்திருக்கும். இவை மண்ணுக்கடியில் வாழ்வதால் இவ்வுயிரினங்களைப் பற்றிய தகவல்கள் மிகவும் குறைவாகும்.

சிறுகண் காலிலி (Caecilian) காலிலி குடும்பத்தை சேர்ந்த ஒரு நிலநீர் வாழ்வன ஆகும். இது மூன்று நீலநீர் வாழ் குடும்பங்களில் ஒன்றாகும், மற்ற இரண்டு குடும்பங்கள் தவளை, / தேரை குடும்பம் மற்றும் நிலநீர் வாலுயிரி குடும்பமாகும். இவை மண் புழு அல்லது பாம்புகளின் உருவத்தை ஒத்திருக்கும். இவை மண்ணுக்கடியில் வாழ்வதால் இவ்வுயிரினங்களைப் பற்றிய தகவல்கள் மிகவும் குறைவாகும்.

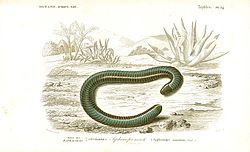

Caecilians (New Latin for 'blind ones') (/sɪˈsɪliən/) are a group of limbless, vermiform (worm-shaped) or serpentine (snake-shaped) amphibians. They mostly live hidden in soil or in streambeds, and this cryptic lifestyle renders caecilians among the least familiar amphibians. Modern caecilians live in the tropics of South and Central America, Africa, and southern Asia. Caecilians feed on small subterranean creatures such as earthworms. The body is cylindrical and often darkly coloured, and the skull is bullet-shaped and strongly built. Caecilian heads have several unique adaptations, including fused cranial and jaw bones, a two-part system of jaw muscles, and a chemosensory tentacle in front of the eye. The skin is slimy and bears ringlike markings or grooves, which may contain tiny scales.

Modern caecilians are grouped as a clade, Apoda /ˈæpədə/, one of three living amphibian groups alongside Anura (frogs) and Urodela (salamanders). Apoda is a crown group, encompassing modern, entirely limbless caecilians. There are more than 200 living species of caecilian distributed across 10 families. The caecilian total group is an order known as Gymnophiona /dʒɪmnəˈfaɪənə/, which includes Apoda as well as a few extinct stem-group caecilians (amphibians related to modern caecilians but evolving prior to the crown group).[2] Gymnophiona as a name derives from the Greek words γυμνος / gymnos (Ancient Greek for 'naked') and οφις / ophis (Ancient Greek for 'snake'), as the caecilians were originally thought to be related to snakes.

The study of caecilian evolution is complicated by their poor fossil record and specialized anatomy. Genetic evidence and some anatomical details (such as pedicellate teeth) support the idea that frogs, salamanders, and caecilians (collectively known as lissamphibians) are each others' closest relatives. Frogs and salamanders show many similarities to dissorophoids, a group of extinct amphibians in the order Temnospondyli. Caecilians are more controversial; many studies extend dissorophoid ancestry to caecilians. Some studies have instead argued that caecilians descend from extinct lepospondyl or stereospondyl amphibians, contradicting evidence for lissamphibian monophyly (common ancestry). Rare fossils of early gymnophionans such as Eocaecilia and Funcusvermis have helped to test the various conflicting hypotheses for the relationships between caecilians and other living and extinct amphibians.

Caecilians anatomy is highly adapted for a burrowing lifestyle. They completely lack limbs, making the smaller species resemble worms, while the larger species like Caecilia thompsoni, with lengths up to 1.5 m (5 ft), resemble snakes. Their tails are short or absent, and their cloacae are near the ends of their bodies.[3][4][5]

Except for one lungless species, Atretochoana eiselti,[6] all caecilians have lungs, but also use their skin or mouths for oxygen absorption. Often, the left lung is much smaller than the right one, an adaptation to body shape that is also found in snakes.[7]

Their muscles are adapted to pushing their way through the ground, with the skeleton and deep muscles acting as a piston inside the skin and outer muscles. This allows the animal to anchor its hind end in position, and force the head forwards, and then pull the rest of the body up to reach it in waves. In water or very loose mud, caecilians instead swim in an eel-like fashion.[8] Caecilians in the family Typhlonectidae are aquatic, and the largest of their kind. The representatives of this family have a fleshy fin running along the rear section of their bodies, which enhances propulsion in water.[9]

Caecilians have small or absent eyes, with only a single known class of photoreceptors, and their vision is limited to dark-light perception.[10][11] Unlike other modern amphibians (frogs and salamanders) the skull is compact and solid, with few large openings between plate-like cranial bones. The snout is pointed and bullet-shaped, used to force their way through soil or mud. In most species the mouth is recessed under the head, so that the snout overhangs the mouth.[5]

The bones in the skull are reduced in number compared to prehistoric amphibian species. Many bones of the skull are fused together: the maxilla and palatine bones have fused into a maxillopalatine in all living caecilians, and the nasal and premaxilla bones fuse into a nasopremaxilla in some families. Some families can be differentiated by the presence of absence of certain skull bones, such as the septomaxillae, prefrontals, an/or a postfrontal-like bone surrounding the orbit (eye socket). The braincase is encased in a fully integrated compound bone called the os basale, which takes up most of the rear and lower parts of the skull. In skulls viewed from above, a mesethmoid bone may be visible in some species, wedging into the midline of the skull roof.[12][13][14]

All caecilians have a pair of unique sensory structures, known as tentacles, located on either side of the head between the eyes and nostrils. These are probably used for a second olfactory capability, in addition to the normal sense of smell based in the nose.[8]

The ringed caecilian (Siphonops annulatus) has dental glands that may be homologous to the venom glands of some snakes and lizards. The function of these glands is unknown.[15]

The middle ear consists of only the stapes bone and the oval window, which transfer vibrations into the inner ear through a reentrant fluid circuit as seen in some reptiles. Species within the family Scolecomorphidae lack both a stapes and an oval window, making them the only known amphibians missing all the components of a middle ear apparatus.[16]

The lower jaw is specialized in caecilians. Gymnophionans, including extinct species, have only two components of the jaw: the pseudodentary (at the front, bearing teeth) and pseudoangular (at the back, bearing the jaw joint and muscle attachments). These two components are what remains following fusion between a larger set of bones. An additional inset tooth row with up to 20 teeth lies parallel to the main marginal tooth row of the jaw.[13]

All but the most primitive caecilians have two sets of muscles for closing the jaw, compared with the single pair found in other amphibians. One set of muscles, the adductors, insert into the upper edge of the pseudoangular in front of the jaw joint. Adductor muscles are commonplace in vertebrates, and close the jaw by pulling upwards and forwards. A more unique set of muscles, the abductors, insert into the rear edge of the pseudoangular below and behind the jaw joint. They close the jaw by pulling backwards and downwards. Jaw muscles are more highly developed in the most efficient burrowers among the caecilians, and appear to help keep the skull and jaw rigid.[8][17]

Their skin is smooth and usually dark, but some species have colourful skins. Inside the skin are calcite scales. Because of these scales, the caecilians were once thought to be related to the fossil Stegocephalia, but they are now believed to be a secondary development, and the two groups are most likely unrelated.[5] Scales are absent in the families Scolecomorphidae and Typhlonectidae, except the species Typhlonectes compressicauda where minute scales have been found in the hinder region of the body.[18] The skin also has numerous ring-shaped folds, or annuli, that partially encircle the body, giving them a segmented appearance. Like some other living amphibians, the skin contains glands that secrete a toxin to deter predators.[8] The skin secretions of Siphonops paulensis have been shown to have hemolytic properties.[19]

Caecilians are native to wet, tropical regions of Southeast Asia, India, Bangladesh, Nepal[20] and Sri Lanka, parts of East and West Africa, the Seychelles Islands in the Indian Ocean, Central America, and in northern and eastern South America. In Africa, caecilians are found from Guinea-Bissau (Geotrypetes) to southern Malawi (Scolecomorphus), with an unconfirmed record from eastern Zimbabwe. They have not been recorded from the extensive areas of tropical forest in central Africa. In South America, they extend through subtropical eastern Brazil well into temperate northern Argentina. They can be seen as far south as Buenos Aires, when they are carried by the flood waters of the Paraná River coming from farther north. Their American range extends north to southern Mexico. The northernmost distribution is of the species Ichthyophis sikkimensis of northern India. Ichthyophis is also found in South China and Northern Vietnam. In Southeast Asia, they are found as far east as Java, Borneo, and the southern Philippines, but they have not crossed Wallace's line and are not present in Australia or nearby islands. There are no known caecilians in Madagascar, but their presence in the Seychelles and India has led to speculation on the presence of undiscovered extinct or extant caecilians there.[21]

In 2021, a live specimen of Typhlonectes natans, a caecilian native to Colombia and Venezuela, was collected from a drainage canal in South Florida. It was the only caecilian ever reported in the wild in the United States, and is considered to be an introduction, perhaps from the wildlife trade. Whether a breeding population has been established in the area is unknown.[22][23]

The name caecilian derives from the Latin word caecus, meaning "blind", referring to the small or sometimes nonexistent eyes. The name dates back to the taxonomic name of the first species described by Carl Linnaeus, which he named Caecilia tentaculata.[5]

There has historically been disagreement over the use of the two primary scientific names for caecilians, Apoda and Gymnophiona. Some specialists prefer to use the name Gymnophiona to refer to the "crown group", that is, the group containing all modern caecilians and extinct members of these modern lineages. They sometimes use the name Apoda to refer to the total group, that is, all caecilians and caecilian-like amphibians that are more closely related to modern groups than to frogs or salamanders. However, many scientists have advocated for the reverse arrangement, where Apoda is used as the name for modern caecilian groups. Some have argued that this use makes more sense, because the name "Apoda" means "without feet", and this is a feature associated mainly with modern species (some stem-group caecilian-like amphibians, such as Eocaecilia, had legs).[24]

A classification of caecilians by Wilkinson et al. (2011) divided the caecilians into 9 families containing nearly 200 species.[13] In 2012, a tenth caecilian family was newly described, Chikilidae.[25][26] This classification is based on a thorough definition of monophyly based on morphological and molecular evidence,[27][28][29][30] and it solves the longstanding problems of paraphyly of the Caeciliidae in previous classifications without an exclusive reliance upon synonymy.[13][31] There are 219 species of caecilian in 33 genera and 10 families.

The most recent phylogeny of caecilians is based on molecular mitogenomic evidence examined by San Mauro et al. (2014), and modified to include some more recently described genera such as Amazops.[32][33][34]

Gymnophiona Eocaeciliidae Apoda Rhinatrematidae Stegokrotaphia Ichthyophiidae Teresomata Scolecomorphidae Chikilidae Herpelidae Caeciliidae Grandisoniidae Dermophiidae Siphonopidae

Little is known of the evolutionary history of the caecilians, which have left a very sparse fossil record. The first fossil, a vertebra dated to the Paleocene, was not discovered until 1972.[35] Other vertebrae, which have characteristic features unique to modern species, were later found in Paleocene and Late Cretaceous (Cenomanian) sediments.[2]

Phylogenetic evidence suggests that the ancestors of caecilians and batrachians (including frogs and salamanders) diverged from one another during the Carboniferous. This leaves a gap of more than 70 million years between the presumed origins of caecilians and the earliest definitive fossils of stem-caecilians.[36][37]

Prior to 2023, the earliest fossil attributed to a stem-caecilian (an amphibian closer to caecilians than to frogs or salamanders but not a member of the extant caecilian lineage) comes from the Jurassic period. This primitive genus, Eocaecilia, had small limbs and well-developed eyes.[38] In their 2008 description of the Early Permian amphibian Gerobatrachus,[39] Anderson and co-authors suggested that caecilians arose from the Lepospondyl group of ancestral tetrapods, and may be more closely related to amniotes than to frogs and salamanders, which arose from Temnospondyl ancestors. Numerous groups of lepospondyls evolved reduced limbs, elongated bodies, and burrowing behaviors, and morphological studies on Permian and Carboniferous lepospondyls have placed the early caecilian (Eocaecilia) among these groups.[40] Divergent origins of caecilians and other extant amphibians may help explain the slight discrepancy between fossil dates for the origins of modern Amphibia, which suggest Permian origins, and the earlier dates, in the Carboniferous, predicted by some molecular clock studies of DNA sequences. Most morphological and molecular studies of extant amphibians, however, support monophyly for caecilians, frogs, and salamanders, and the most recent molecular study based on multi-locus data suggest a Late Carboniferous–Early Permian origin of extant amphibians.[41]

Chinlestegophis, a stereospondyl temnospondyl from the Late Triassic Chinle Formation of Colorado, was proposed to be a stem-caecilian in a 2017 paper by Pardo and co-authors. If confirmed, this would bolster the proposed pre-Triassic origin of Lissamphibia suggested by molecular clocks. It would fill a gap in the fossil record of early caecilians and suggest that stereospondyls as a whole qualify as stem-group caecilians.[36] However, affinities between Chinlestegophis and gymnophionans have been disputed along several lines of evidence. A 2020 study questioned the choice of characters supporting the relationship,[42] and a 2019 reanalysis of the original data matrix found that other equally parsimonious positions were supported for the placement of Chinlestegophis and gymnophionans among tetrapods.[43]

A 2023 paper by Kligman and co-authors described Funcusvermis, another amphibian from the Chinle Formation of Arizona. Funcusvermis was strongly supported as a stem group caecilian based on traits of its numerous skull and jaw fragments, the largest sample of caecilian fossils known. The paper discussed the various hypotheses for caecilian origins: the polyphyly hypothesis (caecilians as lepospondyls, and other lissamphibians as temnospondyls), the lepospondyl hypothesis (lissamphibians as lepospondyls), and the newer hypothesis supported by Chinlestegophis, where caecilians and other lissamphibians had separate origins within temnospondyls. Nevertheless, all of these ideas were refuted, and the most strongly supported hypothesis combined lissamphibians into a monophyletic group of dissorophoid temnospondyls closely related to Gerobatrachus.[37]

Caecilians are the only order of amphibians to use internal insemination exclusively (although most salamanders have internal fertilization and the tailed frog in the US uses a tail-like appendage for internal insemination in its fast-flowing water environment).[8] The male caecilians have a long tube-like intromittent organ, the phallodeum,[44] which is inserted into the cloaca of the female for two to three hours. About 25% of the species are oviparous (egg-laying); the eggs are laid in terrestrial nests rather than in water and are guarded by the female. For some species, the young caecilians are already metamorphosed when they hatch; others hatch as larvae. The larvae are not fully aquatic, but spend the daytime in the soil near the water.[8][45]

About 75% of caecilians are viviparous, meaning they give birth to already-developed offspring. The foetus is fed inside the female with cells lining the oviduct, which they eat with special scraping teeth. Some larvae, such as those of Typhlonectes, are born with enormous external gills which are shed almost immediately.

The egg-laying herpelid species Boulengerula taitana feeds its young by developing an outer layer of skin, high in fat and other nutrients, which the young peel off with modified teeth. This allows them to grow by up to 10 times their own weight in a week. The skin is consumed every three days, the time it takes for a new layer to grow, and the young have only been observed to eat it at night. It was formerly thought that the juveniles subsisted only on a liquid secretion from their mothers.[46][47][48] This form of parental care, known as maternal dermatophagy, has also been reported in two species in the family Siphonopidae: Siphonops annulatus and Microcaecilia dermatophaga. Siphonopids and herpelids are not closely related to each other, having diverged in the Cretaceous Period. The presence of maternal dermatophagy in both families suggest that it may be more widespread among caecilians than previously considered.[49][50]

The diets of caecilians are not well known. Mature caecilians seem to feed mostly on insects and other invertebrates found in the habitat of the respective species. The stomach contents of 14 specimens of Boulengerula taitana consisted of mostly unidentifiable organic material and plant remains. Where identifiable remains were most abundant, they were found to be termite heads.[51] While the undefinable organic material may show the caecilians eat detritus, the remains may be from earthworms. Caecilians in captivity can be easily fed with earthworms, and worms are also common in the habitat of many caecilian species.

As caecilians are a reclusive group, they are only featured in a few human myths, and are generally considered repulsive in traditional customs.

In the folklore of certain regions of India, caecilians are feared and reviled, based on the belief that they are fatally venomous. Caecilians in the Eastern Himalayas are colloquially known as "back ache snakes",[52] while in the Western Ghats, Ichthyophis tricolor is considered to be more toxic than a king cobra.[53][54] Despite deep cultural respect for the cobra and other dangerous animals, the caecilian is killed on sight by salt and kerosene.[53] These myths have complicated conservation initiatives for Indian caecilians.[53][52][54]

Crotaphatrema lamottei, a rare species native to Mount Oku in Cameroon, is classified as a Kefa-ntie (burrowing creature) by the Oku. Kefa-ntie, a term also encompassing native moles and blind snakes, are considered poisonous, causing painful sores if encountered, contacted, or killed. According to Oku tradition, the ceremony to cleanse the affliction involves a potion composed of ground herbs, palm oil, snail shells, and chicken blood applied to and licked off of the left thumb.[55]

South American caecilians have a variable relationship to local cultures.[54] The minhocão, a legendary worm-like beast in Brazilian folklore, may be inspired by caecilians. Colombian folklore states that the aquatic caecilian, Typhlonectes natans, can be manifested from a lock of hair sealed in a sunken bottle. In southern Mexico and Central America, Dermophis mexicanus is colloquially known as the "tapalcua", a name referencing the belief that it emerges to embed itself in the rear end of any unsuspecting person who chooses to relieve themself over its home. This may be inspired by their tendency to nest in refuse heaps.[54]

Caecilians (New Latin for 'blind ones') (/sɪˈsɪliən/) are a group of limbless, vermiform (worm-shaped) or serpentine (snake-shaped) amphibians. They mostly live hidden in soil or in streambeds, and this cryptic lifestyle renders caecilians among the least familiar amphibians. Modern caecilians live in the tropics of South and Central America, Africa, and southern Asia. Caecilians feed on small subterranean creatures such as earthworms. The body is cylindrical and often darkly coloured, and the skull is bullet-shaped and strongly built. Caecilian heads have several unique adaptations, including fused cranial and jaw bones, a two-part system of jaw muscles, and a chemosensory tentacle in front of the eye. The skin is slimy and bears ringlike markings or grooves, which may contain tiny scales.

Modern caecilians are grouped as a clade, Apoda /ˈæpədə/, one of three living amphibian groups alongside Anura (frogs) and Urodela (salamanders). Apoda is a crown group, encompassing modern, entirely limbless caecilians. There are more than 200 living species of caecilian distributed across 10 families. The caecilian total group is an order known as Gymnophiona /dʒɪmnəˈfaɪənə/, which includes Apoda as well as a few extinct stem-group caecilians (amphibians related to modern caecilians but evolving prior to the crown group). Gymnophiona as a name derives from the Greek words γυμνος / gymnos (Ancient Greek for 'naked') and οφις / ophis (Ancient Greek for 'snake'), as the caecilians were originally thought to be related to snakes.

The study of caecilian evolution is complicated by their poor fossil record and specialized anatomy. Genetic evidence and some anatomical details (such as pedicellate teeth) support the idea that frogs, salamanders, and caecilians (collectively known as lissamphibians) are each others' closest relatives. Frogs and salamanders show many similarities to dissorophoids, a group of extinct amphibians in the order Temnospondyli. Caecilians are more controversial; many studies extend dissorophoid ancestry to caecilians. Some studies have instead argued that caecilians descend from extinct lepospondyl or stereospondyl amphibians, contradicting evidence for lissamphibian monophyly (common ancestry). Rare fossils of early gymnophionans such as Eocaecilia and Funcusvermis have helped to test the various conflicting hypotheses for the relationships between caecilians and other living and extinct amphibians.

La senkruraj amfibioj (Gymnophiona) estas ordo en la klaso amfibioj (Amphibia).

Ili haŭto estas kava, malofte skvama. Iliaj membroj tute mankas, la nombro de la vertebroj povas esti eĉ 200. Ili vivas en la subtropikaj kaj tropikaj areoj en Sud-Ameriko kaj Sud-Azio.

Tiuj estas longaj, cilindraj, senkruraj animaloj kun serpenta aŭ verma formo. La plenkreskuloj varias laŭ longo el 8 al 75 centimetroj kun la escepto de la Tomsona cecilio (Caecilia thompsoni), kiu povas atingi 150 cm. La haŭto de cecilio havas grandan nombron de transversaj faldoj kaj en kelkaj specioj ĝi enhavas fajnajn enmetitajn haŭtajn skvamojn. Ili havas povrajn okulojn kovritaj per haŭto, kiuj estas probable limigitaj al konstati diferencojn en lumintenseco. Ili havas ankaŭ paron de mallongaj tentaklojn ĉe la okulo kiuj povas esti etenditaj kaj kiuj havas funkciojn tuŝajn kaj flarajn.

La ordo havas 9 familiojn kaj ĉ. 200 speciojn:

Los gimnofiones o Gymnophiona o cecilias son anfibios grandes sin patas, con forma de lombriz, principalmente de regiones tropicales húmedas, exhibiendo un estilo de vida fosorial al vivir bajo el suelo. Se encuentran en América, África, la India, Indochina y algunas otras regiones que formaron parte de Gondwana durante el Mesozoico.[1] Los registros más antiguos de gimnofiones corresponden al holotipo de Eocaecilia micropodia del Jurásico Inferior[2] y a Rubricacaecilia del Cretácico Inferior[3] Hoy en día se conocen 204 especies vivas de cecilias.[4]

Las cecilias presentan tamaños que van desde los 98-104 mm en los adultos de la especie Idiocranium russeli, hasta 1,5 m en Caecilia thompsoni.[5]

Poseen un cuerpo alargado compuesto por unas 200 vértebras y una cola muy corta en el caso de las especies del grupo Rhinatrematidae, en las cuales, a su vez, la boca está localizada en la región anterior del cráneo, característica ausente en el resto de las familias. No presentan cintura pélvica, cintura escapular ni extremidades, estando el cuerpo organizado en anillos (dándoles un aspecto similar a los gusanos), los cuales pueden estar divididos en anillos secundarios o terciarios, considerándose dicha característica como plesiomórfica (primitiva).[6]

Las cecilias comparten una cabeza aplanada, altamente osificada y con pequeños ojos rudimentarios, en algunos casos atrofiados o cubiertos de piel. Esto parecería indicar que su función es solo la de percibir la luz. La piel, por su parte, es lisa y con surcos transversales, siendo la de la de la región cefálica lisa y muy dura, esto debido a que en las capas más internas se encuentra fusionada con el cráneo. Esta característica les permite buscar y palpar con la cabeza en su entorno, además de cavar con ella sin que la piel se desprenda. Poseen también dos estructuras protráctiles situadas a los lados de la cabeza, entre la nariz y el ojo. Estos apéndices, denominados tentáculos, les permiten detectar olores, siendo únicos entre los vertebrados. La mandíbula se sitúa en la parte inferior de su cabeza, lo cual evita el ingreso de tierra mientras cavan. Poseen además pequeños dientes proyectados hacia atrás, lo cual facilita la captura de las presas.

Al igual que en las serpientes, las anfisbenas y las salamandras, los órganos internos de las cecilias son alargados, estando uno o los dos pulmones reducidos y generalmente el izquierdo ausente, aunque la especie Atretochoana eiselti carece de ambos.[7][8]

La cecilias presentan una fecundación interna (con un período larval que suele durar entre 10 y 12 meses[5]), siendo además ovovivíparas (aunque la mayoría tiene renacuajos nadadores[1]) y dándose casos en que las larvas continúan desarrollándose en el oviducto o canal sexual, alimentándose de secreciones del cuerpo materno funcionalmente equivalentes a la leche. También existen cecilias totalmente ovíparas, en cuyo caso las hembras se enroscan alrededor de los huevos para protegerlos. En la especie Boulengerula taitanus, la cual es endémica de Kenia, se ha documentado una forma de cuidado parental en la cual la hembra alimenta a la prole con su piel, la cual es rica en nutrientes.[9][10]

En comparación con otros anfibios, poco se sabe de las cecilias, ya que su vida subterránea las mantiene escondidas. La mayoría viven en los lechos de hojas y en el suelo blando de las selvas tropicales, aunque algunas especies llevan una vida acuática, buscando comida mientras palpan el lecho de estanques y ríos con su cabeza. Como todos los anfibios, las cecilias adultas son predadores oportunistas, la captura de su alimento depende del tamaño del mismo: lombrices, insectos, arácnidos, otros anfibios y hasta pequeñas lagartijas y roedores.

Al ser tan escaso el registro fósil de las cecilias, poco se sabe sobre su historia evolutiva. Durante mucho tiempo una vértebra descubierta en Brasil, la cual data del Paleoceno, era el único registro con el que se contaba. No fue hasta 1972 que este registro se extendió dramáticamente al descubrirse en Arizona (Estados Unidos) un espécimen del Jurásico Inferior, el cual fue nombrado más tarde como Eocaecilia micropodia.[11][2] Eocaecilia poseía características de las cecilias modernas (Apoda) en el cráneo y en el cuerpo elongado, pero a diferencia de estas presentaba extremidades y ojos bien desarrollados.[12]

Los primeros estudios moleculares de las relaciones filogenéticas de las cecilias con respecto a las ranas y las salamandras, sustentaban una relación cercana entre estas últimas y las cecilias (grupo denominado Procera).[13][14][15] Esta hipótesis ayudaba a explicar los patrones de distribución y el registro fósil de los anfibios modernos, dado el hecho de que las ranas están distribuidas en casi todos los continentes mientras que las salamandras y las cecilias presentan una muy marcada distribución en regiones que alguna vez formaron parte de Laurasia y Gondwana respectivamente. Los registros fósiles más antiguos de ranas (y de lisanfibios) datan del Triásico Inferior (~250 Ma) de Madagascar (correspondiendo al género Triadobatrachus[16]), mientras que los de las salamandras y las cecilias corresponden al período Jurásico (~190 Ma). Sin embargo, los análisis posteriores y recientes en los que se han ocupado grandes bases de datos tanto de genes nucleares como mitocondriales, o una combinación de ambos, establecen a las ranas y las salamandras como grupos hermanos, cuyo clado es denominado Batrachia.[17][18] Este grupo es reafirmado por estudios de datos morfológicos (incluyendo el de especímenes fósiles).[19][20][21]

Por otra parte, los primeros análisis filogenéticos de las relaciones entre las cecilias, adoptaron datos morfológicos y sobre la biología de estas, los cuales fueron, en su mayoría, corroborados por los estudios moleculares posteriores.[22][23][24][25][26][27] Actualmente se reconocen 10 familias de cecilias modernas, cuyas relaciones filogenéticas se describen a continuación:

Stegokrotaphia TeresomataCladograma basado en la filogenia molecular más reciente por San Mauro et al. (2014).[27]

Se reconocen las siguientes familias y número de especies:[4]

Además, se reconoce la familia extinta Eocaeciliidae Jenkins & Walsh, 1993.

duellman

Los gimnofiones o Gymnophiona o cecilias son anfibios grandes sin patas, con forma de lombriz, principalmente de regiones tropicales húmedas, exhibiendo un estilo de vida fosorial al vivir bajo el suelo. Se encuentran en América, África, la India, Indochina y algunas otras regiones que formaron parte de Gondwana durante el Mesozoico. Los registros más antiguos de gimnofiones corresponden al holotipo de Eocaecilia micropodia del Jurásico Inferior y a Rubricacaecilia del Cretácico Inferior Hoy en día se conocen 204 especies vivas de cecilias.

Siugkonnalised (Apoda ehk Gymnophiona) on kahepaiksete klassi kuuluv selts.

Ehkki "Loomade elu" järgi kuulub sellesse seltsi 56 liiki,[1] on pärast raamatu ilmumist veel hulgaliselt siugkonnaliseliike avastatud ja tänapäeval läheneb nende arv 200-le.

Siugkonnalised on levinud Aafrika, Aasia ning Kesk- ja Lõuna-Ameerika troopilistes piirkondades. Madagaskaril ja Austraalias nad puuduvad. [1]

Siugkonnalised on halvasti tuntud, sest nad on kaevuva eluviisiga või elavad vees. Vees elavad üksnes perekonnad Typhlonectes ja Dermophis, ülejäänud elavad niiskes troopikapinnases.[1] Maapinnale tulevad nad peamiselt suurte vihmade järel, kui pinnas on veest küllastunud. Enamik liike ei oskagi ujuda ja kui nad vette kukuvad, siis nad upuvad ära.[1]

Erinevalt päris- ja sabakonnalistest puuduvad siugkonnalistel kõikidel arengustaadiumitel jäsemed ja saba on kas lühike või puudub üldse.[1] Siugkonnalised meenutavad välimuselt suuri limaseid vihmausse.[2] Siugkonnaliste eestikeelne nimetus on tuletatud pealiskaudsel vaatlusel roomajat meenutavast välimusest.

Siugkonnalised on pimedad, sest nende silmad on kaetud luu või nahaga.[1] Peamiseks meeleelundiks on silmade ja sõõrmete vahel asuvad paarilised kombitsad, mille abil leitakse usse, putukaid, tõuke ja muid mullas elavaid saakloomi. Kumbagi kombitsasse avaneb silmanäärme juha. Varem peeti neid ekslikult mürginäärmeteks. Pimeliklased pistavad need kombitsad tihti lohukestest välja nagu sisalikud keele. Kombitsad on ka haistmiselundid ja haistminegi on siugkonnalistel hästi arenenud. [1]

Nahk moodustab rõngasjaid kurde, mis hõlbustavad roomamist. Kurdude arv võib ulatuda 400-ni. Üldiselt tuleb iga selgroolüli kohta üks nahakurd, aga mõnel liigil tekivad arengu käigus veel poolkurrud. Nahk on paljas ja näärmerikas. Näärmed niisutavad nahka ohtra sööbiva limaga. [1]

Ühise roomava eluviisi tõttu on siugkonnalistel ja madudel palju ühiseid tunnuseid. Mõlemal on vasak kops välja veninud pikaks kotiks, aga parem lühenenud. Ka neerud on veninud pikkadeks lintideks. [1]

Siugkonnaliste otsaju on arenenud ja massiivsem kui teistel nüüdisaja kahepaiksetel. Pimeliklastele on iseloomulik näokolju ja ajukolju kokkukasvamine. Hambaid on palju, nad on väikesed, tahapoole kõverdunud ja paiknevad ülalõualuul kahes reas, alalõualuul ühes või kahes reas. [1]

Ühest küljest on siugkonnalistel selgeid spetsialiseerumise tunnuseid, teisalt leidub neil primitiivseid jooni, mis lähendavad neid ürgsetele katispeastele. Sellised tunnused on naha alla peitunud luusoomused (ürgkahepaiksed olid kaetud soomustega), väga tugevalt arenenud katteluud koljus, kuulmeluukese liigestumine ruutluuga, südame kodade vaheline ebatäielik vahesein, keeritsklapita arteriooskuhik, selgroolülid, mis näivad olevat kaksiklohksed, aga on tegelikult pseudotsentraalsed, arenenud seljakeelik, lühikesed alumised roided ja primitiivne keelealune aparaat. [1]

Siugkonnaliste sigimise kohta on vähe teada. Nendel liikidel, kelle kohta andmeid on, toimub viljastumine kehasiseselt. Kolmveerandil liikidest toimub viljastatud munarakkude areng ema sees ning moonde läbinud sündivad noorloomad, kuigi tillukesed, sarnanevad täiskasvanuiga. Veerandil liikidest elavad noorloomad pärast kehasisest viljastumist vastsetena vees.[2]

Mune ei ole väga palju, kuni mõnikümmend. Munad on reburikkad ja suhteliselt suured. Sageli kaitseb emane oma mune, põimudes nende ümber. Ema nahanäärmete eritised kaitsevad mune ärakuivamise eest. Mõne liigi emasloomad kaitsevad sel moel ka oma vastseid. [1]

Siugkonnalised on arenenud kivisöeajastu ahaslülistest kahepaiksetest.[1] Nende evolutsioonist on vähe teada. Esimene fossiilne siugkonnaline avastati alles 1972 paleotseeni ladestust. Varaseim teadaolev siugkonnaline on juuraajastust pärit primitiivne perekond Eocaecilia, kellel olid väikesed jäsemed ja hästiarenenud silmad.

Siugkonnalised (Apoda ehk Gymnophiona) on kahepaiksete klassi kuuluv selts.

Ehkki "Loomade elu" järgi kuulub sellesse seltsi 56 liiki, on pärast raamatu ilmumist veel hulgaliselt siugkonnaliseliike avastatud ja tänapäeval läheneb nende arv 200-le.

Siugkonnalised on levinud Aafrika, Aasia ning Kesk- ja Lõuna-Ameerika troopilistes piirkondades. Madagaskaril ja Austraalias nad puuduvad.

Siugkonnalised on halvasti tuntud, sest nad on kaevuva eluviisiga või elavad vees. Vees elavad üksnes perekonnad Typhlonectes ja Dermophis, ülejäänud elavad niiskes troopikapinnases. Maapinnale tulevad nad peamiselt suurte vihmade järel, kui pinnas on veest küllastunud. Enamik liike ei oskagi ujuda ja kui nad vette kukuvad, siis nad upuvad ära.

Erinevalt päris- ja sabakonnalistest puuduvad siugkonnalistel kõikidel arengustaadiumitel jäsemed ja saba on kas lühike või puudub üldse. Siugkonnalised meenutavad välimuselt suuri limaseid vihmausse. Siugkonnaliste eestikeelne nimetus on tuletatud pealiskaudsel vaatlusel roomajat meenutavast välimusest.

Siugkonnalised on pimedad, sest nende silmad on kaetud luu või nahaga. Peamiseks meeleelundiks on silmade ja sõõrmete vahel asuvad paarilised kombitsad, mille abil leitakse usse, putukaid, tõuke ja muid mullas elavaid saakloomi. Kumbagi kombitsasse avaneb silmanäärme juha. Varem peeti neid ekslikult mürginäärmeteks. Pimeliklased pistavad need kombitsad tihti lohukestest välja nagu sisalikud keele. Kombitsad on ka haistmiselundid ja haistminegi on siugkonnalistel hästi arenenud.

Nahk moodustab rõngasjaid kurde, mis hõlbustavad roomamist. Kurdude arv võib ulatuda 400-ni. Üldiselt tuleb iga selgroolüli kohta üks nahakurd, aga mõnel liigil tekivad arengu käigus veel poolkurrud. Nahk on paljas ja näärmerikas. Näärmed niisutavad nahka ohtra sööbiva limaga.

Ühise roomava eluviisi tõttu on siugkonnalistel ja madudel palju ühiseid tunnuseid. Mõlemal on vasak kops välja veninud pikaks kotiks, aga parem lühenenud. Ka neerud on veninud pikkadeks lintideks.

Siugkonnaliste otsaju on arenenud ja massiivsem kui teistel nüüdisaja kahepaiksetel. Pimeliklastele on iseloomulik näokolju ja ajukolju kokkukasvamine. Hambaid on palju, nad on väikesed, tahapoole kõverdunud ja paiknevad ülalõualuul kahes reas, alalõualuul ühes või kahes reas.

Ühest küljest on siugkonnalistel selgeid spetsialiseerumise tunnuseid, teisalt leidub neil primitiivseid jooni, mis lähendavad neid ürgsetele katispeastele. Sellised tunnused on naha alla peitunud luusoomused (ürgkahepaiksed olid kaetud soomustega), väga tugevalt arenenud katteluud koljus, kuulmeluukese liigestumine ruutluuga, südame kodade vaheline ebatäielik vahesein, keeritsklapita arteriooskuhik, selgroolülid, mis näivad olevat kaksiklohksed, aga on tegelikult pseudotsentraalsed, arenenud seljakeelik, lühikesed alumised roided ja primitiivne keelealune aparaat.

Siugkonnaliste sigimise kohta on vähe teada. Nendel liikidel, kelle kohta andmeid on, toimub viljastumine kehasiseselt. Kolmveerandil liikidest toimub viljastatud munarakkude areng ema sees ning moonde läbinud sündivad noorloomad, kuigi tillukesed, sarnanevad täiskasvanuiga. Veerandil liikidest elavad noorloomad pärast kehasisest viljastumist vastsetena vees.

Mune ei ole väga palju, kuni mõnikümmend. Munad on reburikkad ja suhteliselt suured. Sageli kaitseb emane oma mune, põimudes nende ümber. Ema nahanäärmete eritised kaitsevad mune ärakuivamise eest. Mõne liigi emasloomad kaitsevad sel moel ka oma vastseid.

Siugkonnalised on arenenud kivisöeajastu ahaslülistest kahepaiksetest. Nende evolutsioonist on vähe teada. Esimene fossiilne siugkonnaline avastati alles 1972 paleotseeni ladestust. Varaseim teadaolev siugkonnaline on juuraajastust pärit primitiivne perekond Eocaecilia, kellel olid väikesed jäsemed ja hästiarenenud silmad.

Gymnophiona anfibioen ordena bat da, zizare edo sugeen antza duten espezieez osatuta. Tropikoetan , Hego eta Ertamerikan, Afrikan eta hegoaldeko Asian, bizi da.

Hona hemen ordenaren familiak:[1]

Hona hemen egungo filogenia:[2]

Gymnophiona anfibioen ordena bat da, zizare edo sugeen antza duten espezieez osatuta. Tropikoetan , Hego eta Ertamerikan, Afrikan eta hegoaldeko Asian, bizi da.

Matosammakot (Gymnophiona tai Apoda) on yksi sammakkoeläinten lahkoista. Lahkoon kuuluu kymmenen heimoa ja 208 lajia.[1] Lahkon lajeilta puuttuvat raajat, minkä vuoksi niitä pidettiin aluksi käärmeinä. Matosammakkojen etu- ja takaruumiit ovat yleensä suunnilleen samannäköiset ja niiden ruumis on tasapaksu. Iho on paljas tai siinä on pyöreitä sarveissuomuja.

Matosammakot elävät Keski- ja Etelä-Amerikassa, Afrikassa ja osassa Aasiaa.[2]

Eräät lajit elävät vedessä, mutta suurin osa tropiikin seutujen kuohkeassa mullassa. Naaras munii yleensä kuoppaan, josta se myös kaivaa käytävän lähimpään lammikkoon. Joidenkin lajien naaraat myös vartioivat pesäänsä, mutta läheskään kaikki eivät tee niin. Toukkien kuoriutuessa ne siirtyvät käytävää pitkin lammikkoon.

Matosammakot jaetaan kymmeneen heimoon:[1]

Yksittäisten matosammakkolajien lukumäärä on epävarma, sillä monet lajit on kuvattu yhden ainoan yksilön perusteella. Tiedon karttuessa nyt erillisinä pidettyjä lajeja jouduttaneen yhdistämään. Koska matosammakot elävät piilottelevaa elämää, kokonaan uusia lajeja kuitenkin löytynee vielä.

Matosammakot (Gymnophiona tai Apoda) on yksi sammakkoeläinten lahkoista. Lahkoon kuuluu kymmenen heimoa ja 208 lajia. Lahkon lajeilta puuttuvat raajat, minkä vuoksi niitä pidettiin aluksi käärmeinä. Matosammakkojen etu- ja takaruumiit ovat yleensä suunnilleen samannäköiset ja niiden ruumis on tasapaksu. Iho on paljas tai siinä on pyöreitä sarveissuomuja.

Matosammakot elävät Keski- ja Etelä-Amerikassa, Afrikassa ja osassa Aasiaa.

Eräät lajit elävät vedessä, mutta suurin osa tropiikin seutujen kuohkeassa mullassa. Naaras munii yleensä kuoppaan, josta se myös kaivaa käytävän lähimpään lammikkoon. Joidenkin lajien naaraat myös vartioivat pesäänsä, mutta läheskään kaikki eivät tee niin. Toukkien kuoriutuessa ne siirtyvät käytävää pitkin lammikkoon.

Les Gymnophiona sont un ordre d'amphibiens vermiformes. Ils sont appelés en français apodes, cécilies ou gymnophiones. Le taxon Apoda est également utilisé pour désigner le groupe-couronne des espèces actuelles[1]. Il ne doit pas être confondu avec le genre Apoda qui désigne des lépidoptères nocturnes de la famille des Limacodidae.

Les gymnophiones ont été décrits par Johannes Peter Müller en 1832 et regroupent des amphibiens terrestres et aquatiques, auxquels des pattes atrophiées donnent l'aspect de vers de terre.

Les gymnophiones sont des lissamphibiens fouisseurs, dépourvus de membres et de ceinture. Suivant les espèces, leur taille varie entre 7 cm et 1,4 m[2]. En général, leur taille varie entre 20 cm et 50 cm (Taylor, 1968). Ils sont généralement carnivores.

Leur corps est cylindrique et allongé. Il est marqué sur toute son étendue d’une succession d’anneaux et sillons transversaux. Le tronc est terminé par une courte queue de même diamètre que le reste du corps. Chaque anneau correspond à une vertèbre, dont le nombre peut atteindre 300.

Chez plusieurs genres tels que Typhlonectes il n’y a pas d’anneaux mais des plis. Plusieurs familles possèdent une véritable queue correspondant à plusieurs vertèbres situées en arrière de l’orifice cloacal. Chez d'autres, il n’y a pas de queue car pas de vertèbres postérieures au cloaque. Chez d’autres enfin, un petit appendice, l'écu (shield de Taylor, 1968) est postérieur au cloaque. L’ouverture cloacale peut avoir une forme différente selon le sexe mais il est souvent difficile de déterminer extérieurement le sexe.

La peau est épaisse généralement grisâtre et peut être recouverte d’écailles chez les espèces appartenant aux familles considérées comme les moins évoluées (Rhinatrematidae, Ichthyophiidae). Ces écailles ressemblent à celles des poissons ostéichthyens et recouvrent tout le corps. Chez d’autres espèces, les écailles couvrent seulement la partie postérieure du corps. Dans ce cas les écailles les plus antérieures sont plus petites que les autres et dispersées dans la peau. C’est le cas de Geotrypetes seraphini, par exemple. Aucune écaille n’a été observée dans la peau des formes considérées comme les plus évoluées (Typhlonectidae) même si quelques écailles dégénérées ont été décrites (Wake et Nygren, 1987). Leur peau est visqueuse, aux sécrétions toxiques.

Le crâne est composé de plus d’os que chez les autres Lissamphibiens. La mâchoire inférieure est constituée de deux moitiés réunies par du tissu conjonctif. Une structure rétro-articulaire est observée en arrière de chaque mâchoire inférieure. Sur cette structure anatomique s’insère une puissante musculature impliquée dans la mastication et la fermeture de la bouche après la capture des proies.

Les vertèbres sont de type primitif et permettent seulement un déplacement horizontal (Lawson 1963, 1966a, Taylor 1977, Renous et Gasc 1986a, b). Ce sont des vertèbres dites amphicèles, rappelant celles des poissons osseux. Le centre de la vertèbre comporte un centrum, cicatrice du passage de la chorde dorsale embryonnaire. Les trois premières vertèbres sont plus grandes que les autres et elles sont très mobiles. Elles constituent le collier que l’on peut comparer au cou des vertébrés amniotes (Lescure and Renous 1992).

Les Gymnophiones ne possèdent ni membres ni ceintures. Mais chez le primitif Ichthyophis glutinosus, des traces de ceintures régressées ont été observées, et pendant le développement embryonnaire, des blastèmes de membres se développent mais dégénèrent à la métamorphose (Renous et al., 1997). La perte des membres est donc secondaire.

Le cerveau des Gymnophiones adultes ressemble à celui des autres amphibiens mais présente à la fois des caractéristiques trouvées chez les vertébrés amniotes et des caractéristiques propres, telles que l’allongement et une flexion entre le diencéphale et le mésencéphale. Les nerfs olfactifs sont particulièrement développés et deux bulbes olfactifs accessoires associés aux organes voméronasaux sont observés en position antérieure.

Les yeux sont de petite taille, recouverts par la peau qui peut être plus ou moins épaisse et transparente à ce niveau. Chez Scolecomorphus, ils sont recouverts par les os crâniens. Le cristallin n’est pas totalement lamellaire car il comporte des cellules nucléées, la rétine comporte seulement des cônes. Les nerfs optiques sont réduits, la musculature oculomotrice est combinée aux tentacules. L’aire céphalique qui correspond aux muscles oculomoteurs est également réduite (Wake 1985, Himstedt et Manteuffel 1985, Brun et Exbrayat 2007). Chez les Gymnophiones, un pigment vert caractéristique des autres Amphibiens actuels n’est pas retrouvé (Rage 1985). Cette régression des yeux représente incontestablement une adaptation à la vie fouisseuse.

Une paire de tentacules a été décrite chez tous les Gymnophiones. Chacun d’entre eux est contenu dans un sac qui enveloppe également l’œil correspondant. Chaque tentacule est extrudé à l’extrémité du museau, entre la narine et l’œil à l’aide d’une musculature (Billo and Wake 1987), lubrifié par les glandes de Harder (glandes lacrymales). Chaque tentacule est relié à un organe voméronasal. Les tentacules sont en permanence animés d’un mouvement de va-et-vient par lequel ils captent les molécules qui sont analysées par les organes voméronasaux. Il s’agit d’une adaptation à la vie fouisseuse qui permet à l'animal de s’orienter dans le tunnel qu’il est en train de creuser alors que les narines et la bouche sont hermétiquement fermées.

Des organes de la ligne latérale, caractéristiques des vertébrés aquatiques, sont observés chez les larves aquatiques des Gymnophiones mais pas chez les larves intra-utérines. On en trouve également chez les adultes de certaines espèces aquatiques. Ces organes sont répartis de part et d’autre du corps (neuromastes) et sur le museau (organes ampoulaires).