mk

имиња во трошки

Telmatobius culeus és una espècie de granota que viu al llac Titicaca (Perú i Bolívia).

Telmatobius culeus és una espècie de granota que viu al llac Titicaca (Perú i Bolívia).

Vodnice posvátná (Telmatobius culeus) je sladkovodní druh žáby, endemit žijící ve vysokohorském jezeře Titicaca nacházející se v centrálních Andách na rozhraní mezi státy Peru a Bolívie. Její hlavní populace žije v rozlehlejší, severní části jezera nazývané Lake Chucuito a jen sporadický počet se nachází v menší, jižní části s názvem Lake Wiñaymarka. Ojediněle se vyskytuje i v říčních přítocích jezera.[2]

Jezero s maximální hloubkou 280 m je teplotně stabilní, u dna je teplota vody celoročně 10 °C, u hladiny kolísá od 6 do 14 °C. Voda v jezeře má v důsledku vysoké nadmořské výšky (3800 m n. m.) snížený obsah rozpuštěných plynů (kyslíku), průměrný parciální tlak kyslíku je 100 mm Hg (u mořské hladiny je přibližně 130 mm Hg).[2][3]

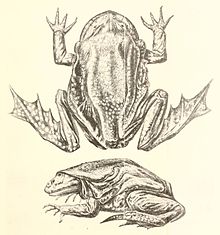

Je žábou žijící trvale ve sladké vodě, na souš nevylézá. Je snadno rozpoznatelná podle "pytlovitého" vzhledu, který má v důsledku velkých, volných záhybů kůže. Má je po stranách, na hřbetě i zadních končetinách. Samci se od samic viditelně neodlišují.

Zbarvení těla je variabilní, ale vždy určitá část obsahuje barvu olivově zelenou nebo tmavě zelenou až černou, na zádech bývá skoro černá a na břichu světlá, někdy až špinavě bílá. Je velká až 14 cm a může vážit i 250 g, tělo má ploché a nebývá vyšší než 5 cm. Hlava je velká a plochá s kruhovitou tlamou, oči mají duhovky světle hnědé. Na předních končetinách má prsty volné, na silných zadních částečně spojené plovací blánou.[2][3][4]

Velké záhyby zvětšují plochu kůže přes kterou dýchá, tenká mokrá kůže funguje jako žábry a zajišťuje dostatek kyslíku k pokrytí metabolických nároků organizmu. Primárně dýchá kůži a za normálních podmínek se nepotřebuje vynořit nad hladinu pro vzduch.

Má v krvi vysoký počet červených krvinek a síť kožních žil je mnohem hustější než u jiných rodů, stejně tak dokáže přežít při mnohem nižším obsahu kyslíku v krvi. V porovnání s jinými, obdobně velkými žabami má však jen třetinové plíce, které ji na suchu udrží při životě jen několik málo hodin. V případě snížení obsahu kyslíku ve vodě, který občas klesá na 35 až 90 mm Hg,[zdroj?] vystrkuje nad hladinu čenich a jímá do plic vzduch, dokud se krev dostatečně neokysličí.[2][3][4][5]

Z vody na souš nevystupuje, dospělci žijí osaměle při jezerním dnu, mladší jedinci se zdržují zase výhradně u břehů v mělčích oblastech jezera. Jsou důkazy, že tyto žáby rostou po celou dobu života, do doby dospělosti rychle a pak se jejich růst zpomaluje. V přírodě se dožívají 5 až 15 let. V případě stresu se brání vylučováním mléčně zbarveného, lepkavého a hořkého slizu z celé pokožky.[2][3][4][5]

Živí se živočišnou potravou, hlavně vodními různonožci, měkkýši, hmyzem, drobnými rybymi a pulci žab. Svým krátkým jazykem není schopna uchopit suchozemskou kořist. Lapenou potravu polyká vcelku, případně za pomoci předních nohou. Má ze všech obojživelníků, vyjma mloků, nejpomalejší metabolismus.[2][3][4][5]

K páření dochází v létě (na jižní polokouli) v mělkých vodách v blízkosti břehů. Začátkem sezony se snaží samci nočním hlasitým voláním přilákat samici. Pářící se samec samici shora objímá v pase před zadními nohama. Samice vypouští vajíčka a samec je následně oplozuje. Z vajíček se líhnou nejdříve larvy, pulci, kteří se metamorfózou proměňují v žáby. Odhaduje se nakladení jednou samicí 500 vajíček ročně, první snůška proběhne asi v pátém roce života. Nebyla pozorována žádná péče o potomstvo.[2][3][4][5]

Početní stavy vodnice posvátné za posledních 15 let poklesly o více než 80 % a je proto IUCN prohlášena za kriticky ohrožený druh. Její lov i obchod je sice zakázán, ale stěží lze jeho dodržování kontrolovat a vymáhat. Tyto žáby jsou tradičně chytány a v širokém okolí jezera používány pro domnělé léčebné i afrodiziakální vlastnosti. Navíc byli do jezera vysazeni nepůvodní pstruzi, kteří se živí vajíčky a pulci žab. Soudí se, že velký splach pesticidů, hnojiv a dalších znečišťujících látek z okolí do jezera snižuje plodnost samic a zapříčiňuje špatný vývoj vajíček i pulců.

Chování v zajetí bývá obvykle úspěšné jen výjimečně a krátkodobě, stejně jako dosavadní záchranné programy na jezeře. To je také důvodem, že o životě vodnice posvátné není dostatek podrobných znalostí.[2][3][6]

Tento druh patří mezi velmi vzácně chované. Na počátku roku 2019 byl v celé Evropě jen v britské Chester Zoo, kam bylo v roce 2018 dovezeno 150 jedinců z americké Denver Zoo[7], které se podařilo vodnici jako první mimo oblast výskytu rozmnožit.[8] Jednalo se o historicky první příslušníky tohoto druhu v evropských zoo.[7] Dovezená zvířata byla na počátku roku 2019 dále šířena do evropských zoo Evropské asociace zoologických zahrad a akvárií tak, aby byla vytvořena chovatelská síť, která se pokusí zachránit tento ohrožený druh. Mezi chovatele vodnice posvátné se také zařadila Zoo Praha v Česku. 1. března 2019 do ní dorazilo 70 jedinců, z nichž si zoo ponechá 20; zbylá zvířata poputují do Zoo Wroclaw v Polsku a vídeňských zoo Tiergarten Schönbrunn a Haus des Meeres.[8] Mezi další evropské zoo s tímto druhem patří např. zoo v Rotterdamu či Amersfoortu (obě Nizozemsko) či německá zoo ve městě Münster.[7]

Vodnice posvátná (Telmatobius culeus) je sladkovodní druh žáby, endemit žijící ve vysokohorském jezeře Titicaca nacházející se v centrálních Andách na rozhraní mezi státy Peru a Bolívie. Její hlavní populace žije v rozlehlejší, severní části jezera nazývané Lake Chucuito a jen sporadický počet se nachází v menší, jižní části s názvem Lake Wiñaymarka. Ojediněle se vyskytuje i v říčních přítocích jezera.

Der Titicaca-Riesenfrosch (Telmatobius culeus), auch als Titicacafrosch oder Titicacaseefrosch bezeichnet, gehört zur Gattung der Anden-Pfeiffrösche (Telmatobius). Er lebt endemisch nur im Titicacasee auf dem Hochplateau der Anden in Peru und Bolivien und ist vom Aussterben bedroht. Diese Art nutzt hauptsächlich ihre Haut zum Gasaustausch. Die stark gefaltete Haut erhöht die respiratorische Oberfläche.

Nachdem Jacques-Yves Cousteau 1973 den Titicacasee mit Tauchern und Tauchbooten erforscht hatte, berichtete er von Exemplaren dieses aquatil lebenden Frosches, die bis zu 50 cm lang und 1 kg schwer gewesen sein sollen. Offenbar basiert diese biometrische Angabe allerdings auf der Summe der Kopf-Rumpf-Länge und der ausgestreckten Hinterbeine – eine in der Zoologie nicht übliche Messweise. Die maximale Kopf-Rumpf-Länge selbst dürfte, abgeleitet aus diesen Angaben, bei immerhin mehr als 20 cm liegen. Andere Autoren sprechen sogar von ungefähr 12 inches oder knapp einem Fuß[1], was etwa 30 Zentimetern entspräche. Der Titicaca-Riesenfrosch gehört damit zu den größten Arten unter den Froschlurchen, auch wenn er nicht die Ausmaße des westafrikanischen Goliathfrosches erreicht.

Charakteristisch für die Art ist ihre stark aufgefaltete Haut. Sie sieht aus, als sei sie für den Froschkörper viel zu groß geraten. Auf Rücken und Bauch, aber auch an den Beinen sind diese sackartigen Falten sehr auffällig. Die Falten über dem Nacken geben dem Frosch ein Aussehen, als hätte er eine Mönchskutte um. Die Färbung der Haut ist variabel und reicht von Olivgrün mit pfirsichfarbenem Bauch über Grau mit schwarzen Sprenkeln auf dem Rücken bis Schwarz mit weißer Marmorierung. Einige Exemplare sind ganz schwarz gefärbt.

Der Titicaca-Riesenfrosch hat wie alle Anden-Pfeiffrösche kräftige Hinterbeine und Füße mit besonders großen Schwimmhäuten, die ihm eine schnelle Fortbewegung unter Wasser ermöglichen.

Der Titicacasee liegt in einer Höhe von 3810 m auf dem Altiplano, einer Hochebene der Anden. Er umfasst eine Fläche von 8288 Quadratkilometern und hat eine maximale Tiefe von 280 m. In dieser Höhe kann es in der Nacht zu Temperaturen unterhalb des Gefrierpunktes kommen, während tagsüber eine intensive Sonneneinstrahlung mit hohem Ultraviolettanteil vorherrscht. Diese ökologischen Bedingungen haben zur Evolution nur hier vorkommender Lebewesen geführt. Umgekehrt sind diese Organismen durch eine Änderung der Umweltfaktoren eher vom Aussterben bedroht als weniger spezialisierte Tiere.

Für die Titicaca-Riesenfrösche war vor allem der niedrige Luftdruck in dieser Höhe ein Anpassungsfaktor, da sie mit einer geringeren Sauerstoffkonzentration im Wasser und an Land zurechtkommen müssen. Um sich außerdem nicht den extremen Temperaturschwankungen an Land und der hohen UV-Lichtintensität auszusetzen, sind die Tiere zu einer voll aquatilen Lebensweise übergegangen. Die dunkle bis schwarze Färbung auf dem Rücken der Frösche, die durch Melanophoren in der Haut verursacht wird, verhindert – ebenso wie die schwarze Haut bei den Eisbären – das Durchdringen von UV-Strahlung.

Sauerstoff nimmt der Titicaca-Riesenfrosch aus dem Wasser fast ausschließlich durch die Haut auf, man spricht dabei von Hautatmung. Die Lunge ist im Lauf der Entwicklungsgeschichte stark reduziert worden. Dafür wird eine stark vergrößerte Hautoberfläche durch eine große Anzahl von Falten und Taschen gebildet, die dem Frosch ein sehr schwabbeliges und faltiges Aussehen geben. Das Verhältnis der respiratorischen Oberfläche zum Volumen des Tieres wird dadurch verbessert. Eine Bewegung, die dem Liegestütz beim Sport ähnelt, führt dazu, dass das Wasser an den Faltenbildungen vorbeibewegt wird und der Gasaustausch besser funktioniert. Dazu kommen spezielle Anpassungen im Blut dieser Frösche: ihr Blut besitzt die kleinsten roten Blutkörperchen (Erythrozyten) aller Amphibien und gleichzeitig den höchsten Anteil an Hämoglobin. An dieses Hämoglobin wird der Sauerstoff zum Weitertransport durch die Blutbahnen gekoppelt.

Bei der Nahrungsaufnahme ist die Art nicht wählerisch und ernährt sich von Würmern, Flohkrebsen der Gattung Hyalella, Wasserschnecken, Kaulquappen und kleinen Fischen, beispielsweise dem Ispi-Andenkärpfling Orestias ispi. Die Beute wird in einem Stück verschluckt, bei Bedarf unter Zuhilfenahme der Vorderbeine.[2]

Jacques-Yves Cousteau sah bei seinen Tauchgängen in den frühen 1970er-Jahren den Boden noch dicht bedeckt mit den Titicaca-Riesenfröschen. Er sprach von Millionen Individuen, die hier leben müssten. Heute ist der Frosch aus vielen Teilen des Sees fast völlig verschwunden. Es gibt keine endgültige Erklärung für diesen Rückgang der Populationen. Manche Forscher vermuten, der Titicaca-Riesenfrosch habe sich in andere Teile des Sees zurückgezogen, wo es mehr Nahrung für ihn gäbe. Die verminderten Froschpopulationen gehen offenbar mit dem Rückgang einer kleinen Fischart aus der Gattung der Andenkärpflinge einher, die in der Ketschua-Sprache Ispi genannt wird. Dieser gut 7 cm lang werdende Fisch bildet die Hauptnahrungsquelle des Titicaca-Riesenfrosches. Er könnte den Wanderungen der Fischschwärme in andere Gebiete des Sees gefolgt sein.

Andererseits werden dem See auch große Mengen der kleineren Fische entnommen, um sie als Futter für die Zucht größerer Fische zu verarbeiten. Der Titicaca-Riesenfrosch befindet sich als Beifang ebenfalls oft in den Netzen der Fischer. Er wird von der indigenen Bevölkerung, die an den Ufern des Sees lebt, gegessen und traditionell als Heilmittel verwendet, die Froschschenkel sind aber auch in Restaurants in Peru und Bolivien erhältlich.[3] Ein Extrakt aus den Fröschen wird unter dem Namen „Viagra peruano“ als Aphrodisiakum verkauft.[1] Dies und die Verschmutzung des Sees haben zu einer hohen Gefährdung des Titicacafrosches geführt. Die IUCN stuft die Art inzwischen als „critically endangered“ (vom Aussterben bedroht) ein.[4]

Die sehr artenreiche Familie der Südfrösche (Leptodactylidae i. w. S.) wird inzwischen als paraphyletisch aufgefasst und wurde deshalb in mehrere monophyletische Gruppen aufgespalten. Arten der Gattung Telmatobius wurden beispielsweise bis 2011 zusammen mit den Hornfröschen (Ceratophrys) und noch fünf anderen Gattungen in eine Familie Ceratophryidae gestellt.[5][6]

Ehemalige Arten der Gattung Telmatobius werden nun in verschiedene Taxa aufgeteilt, die sich in ihrer Verbreitung, ihrer Lebensweise und im Körperbau unterscheiden. Eine im südlichen Südamerika, besonders in Patagonien verbreitete Gruppe, die inzwischen zur Gattung Atelognathus zusammengestellt wird, umfasst eher kleinere Arten von 25 bis 50 mm Größe, die teilweise auch terrestrisch leben. Eine nördliche Verbreitungsgruppe, zu der auch der Titicacafrosch gehört, besteht aus wesentlich größeren Spezies, die aquatil in hochgelegenen Seen und Flüssen der Anden leben. Darüber hinaus werden andere frühere Telmatobius-Arten in zahlreiche weitere Gattungen und andere Froschlurchfamilien gestellt.

Die sehr unterschiedlichen Farbvarianten des Titicaca-Riesenfrosches haben zu der Vermutung von Biologen geführt, dass bis zu sieben Unterarten in dem See vorkommen. Nach Untersuchungen des bolivianischen Forschers Edgar Benavides, der 1997 erstmals die DNA der verschiedenen Exemplare untersuchte, gehören aber alle zur selben Art und es handelt sich nur um ein großes Spektrum von verschiedenen Färbungen (Polymorphismus).[2][7] Telmatobius albiventris mit vier Unterarten und Telmatobius crawfordi werden von manchen Autoren wieder in die Art Telmatobius culeus eingegliedert.[8] Es hat sich gezeigt, dass Unterschiede in der Körpergröße und Anpassungen an das spezielle ökologische Mikrohabitat vorhanden sind, diese wirken jedoch nicht als Kreuzungsbarrieren, sondern führen zu graduell unterschiedlichen Formen und Verhaltensmustern.

Der Titicaca-Riesenfrosch (Telmatobius culeus), auch als Titicacafrosch oder Titicacaseefrosch bezeichnet, gehört zur Gattung der Anden-Pfeiffrösche (Telmatobius). Er lebt endemisch nur im Titicacasee auf dem Hochplateau der Anden in Peru und Bolivien und ist vom Aussterben bedroht. Diese Art nutzt hauptsächlich ihre Haut zum Gasaustausch. Die stark gefaltete Haut erhöht die respiratorische Oberfläche.

Ο Τελματόβιος ο σάκος[2][3][4] (λατ.) Telmatobius culeus (ασκός) κοινώς γνωστός ως βάτραχος στα νερά της Τιτικάκα είναι ένα πολύ μεγάλο και άκρως απειλούμενο είδος βατράχου στη λίμνη Τιτικάκα και τα ποτάμια που εκβάλλουν σε αυτή. Το μήκος του μπορεί να φθάσει το μισό μέτρο και το βάρος του το ένα κιλό· διαθέτει τεράστια πίσω πόδια.

Το περίεργο είναι ότι, αν και θεωρητικά είναι αμφίβια ζώα και έχουν πνεύμονες, δεν χρειάζεται να ανέβουν στον αέρα για να αναπνεύσουν, επειδή έχουν συνηθίσει να προσλαμβάνουν το οξυγόνο που χρειάζονται μέσα από το νερό με το δέρμα τους. Κατά τον Κουστώ,[5] η προσμαργογή αυτή οφείλεται στο ότι έτσι κι αλλιώς η ατμόσφαιρα είναι πολύ αραιή σε τέτοιο υψόμετρο (3.854μ.) και η χρήση των πνευμόνων θα ήταν δύσκολη, αν δεν αυξανόταν υπερβολικά το μέγεθός τους, ενώ η απευθείας παραλαβή του οξυγόνου είναι απλούστερη.

Ο Τελματόβιος ο σάκος (λατ.) Telmatobius culeus (ασκός) κοινώς γνωστός ως βάτραχος στα νερά της Τιτικάκα είναι ένα πολύ μεγάλο και άκρως απειλούμενο είδος βατράχου στη λίμνη Τιτικάκα και τα ποτάμια που εκβάλλουν σε αυτή. Το μήκος του μπορεί να φθάσει το μισό μέτρο και το βάρος του το ένα κιλό· διαθέτει τεράστια πίσω πόδια.

Το περίεργο είναι ότι, αν και θεωρητικά είναι αμφίβια ζώα και έχουν πνεύμονες, δεν χρειάζεται να ανέβουν στον αέρα για να αναπνεύσουν, επειδή έχουν συνηθίσει να προσλαμβάνουν το οξυγόνο που χρειάζονται μέσα από το νερό με το δέρμα τους. Κατά τον Κουστώ, η προσμαργογή αυτή οφείλεται στο ότι έτσι κι αλλιώς η ατμόσφαιρα είναι πολύ αραιή σε τέτοιο υψόμετρο (3.854μ.) και η χρήση των πνευμόνων θα ήταν δύσκολη, αν δεν αυξανόταν υπερβολικά το μέγεθός τους, ενώ η απευθείας παραλαβή του οξυγόνου είναι απλούστερη.

Telmatobius culeus, commonly known as the Titicaca water frog, is a medium-large to very large and endangered species of frog in the family Telmatobiidae.[3] It is entirely aquatic and only found in the Lake Titicaca basin, including rivers that flow into it and smaller connected lakes like Arapa, Lagunillas and Saracocha, in the Andean highlands of Bolivia and Peru.[4][5][6] In reference to its excessive amounts of skin, it has jokingly been referred to as the Titicaca scrotum (water) frog.[7]

It is closely related to the more widespread and semiaquatic marbled water frog (T. marmoratus),[8][9] which also occurs in shallow, coastal parts of Lake Titicaca,[10] but lacks the excessive skin and it is generally smaller (although overlapping in size with some forms of the Titicaca water frog).[5]

In the late 1960s, an expedition led by Jacques Cousteau reported Titicaca water frogs up to 60 cm (2 ft) in outstretched length and 1 kg (2.2 lb) in weight,[11][12][13] making these some of the largest exclusively aquatic frogs in the world (the exclusively aquatic Lake Junin frog can grow larger, as can the helmeted water toad and African goliath frog that sometimes can be seen on land).[14] The snout–to–vent length of the Titicaca water frog is up to 20 cm (8 in),[15][16] and the hindlegs about twice as long.[13]

Most individuals do not reach such sizes, but are still big frogs. Titicaca water frogs of the largest and typical form, upon which the species was first described, usually have a snout–to–vent length of 7.5 to 17 cm (3.0–6.7 in) and weigh less than 0.4 kg (0.9 lb).[5][14][16] This typical form tends to inhabit relatively deep water in eastern Lake Titicaca, but a minority of the individuals in the Coata River (which flows into far western Lake Titicaca) are similar.[5][6] Several other forms are found at shallower depths in Lake Titicaca, in smaller lakes that are part of the same basin, and in rivers and streams that flow into Titicaca. These tend to be smaller in size with a snout–to–vent length of 4 to 8.9 cm (1.6–3.5 in) and historically they were recognized as separate species (T. albiventris and T. crawfordi), but there are extensive individual variations (sometimes even at a single location), no clear limits between the forms (they intergrade) and taxonomic reviews have found that all are variants of the Titicaca water frog.[5][6] Females generally reach maturity at a slightly larger size than males, they average larger and they also have a larger maximum size than males.[16][17][18]

In addition to total size, the various forms of the Titicaca water frog differ in the relative size of the dorsal shield (a hard structure on the back), relative width of the head and other morphological features, with most bays in Lake Titicaca having their own type.[5][6]

Compared to similar-sized frogs, the lungs of the Titicaca water frog only are about one-third the size. Instead it has excessive amounts of skin to help the frog respire in the cold water in which it lives.[4][19][20] The baggy skin is particularly distinct in large individuals.[21] In living individuals the skin folds are swollen with fluids, but if deflated the frog is actually relatively thin.[6]

The color is highly variable, but generally gray, brown or greenish above, and paler below. There are often some spots, which can form a marbled pattern.[18][21] Animals in coastal southernmost Lake Titicaca typically have striped thighs and relatively bright orange underparts.[6] If teased, Titicaca water frogs can secrete a sticky whitish fluid from their skin in defense.[22]

Titicaca water frogs live exclusively in lakes and rivers in the Lake Titicaca basin.[6][21] Adults of the typical form generally live deeper than 10 m (33 ft) in Lake Titicaca itself,[5] but the maximum limit is unknown.[23] While exploring this lake in a mini submarine, Jacques Cousteau filmed individuals and their prints in the bottom silt at 120 m (400 ft), which is the record depth for any species of frog.[13][21] The other forms of the Titicaca water frog are found at no more than 10 m (33 ft).[5] A study that surveyed depths from the shore to 7 m (23 ft) near Isla del Sol found that adults were most common at 1.5–3 m (5–10 ft).[17] In general, Titicaca water frogs prefer a mixed bottom; either a muddy or sandy bottom with some rocks, or with plenty of aquatic plants and some rocks.[17][21]

The Titicaca water frog spends its entire life in water that typically is 8–17.5 °C (46.5–63.5 °F), with the average annual temperature being near the middle and the minor seasonal variations being matched or even exceeded by the daily variations.[16][17] The frogs can regulate their own temperature by moving between different microhabitats with slightly different water temperatures and adults will sometimes position themselves on top of underwater rocks to bask in the sun that penetrate the lake's clear water.[17]

The water in which it lives generally is very rich in oxygen, but limited by the low atmospheric pressure at the high altitude,[4][19][20] from about 3,800 m (12,500 ft) at Lake Titicaca to at least 4,250 m (14,000 ft) in associated river and smaller lakes.[6] It respires by its skin, which absorbs oxygen, functioning in a manner that is comparable to gills.[19][20][23] It sometimes performs "push-ups" or "bobs" up–and–down to allow more water to pass by its large skin folds. The skin is very rich in blood vessels that extend to its outermost layer. Of all frogs, it has the lowest relative red blood cell volume, but the highest count (i.e., many but small red blood cells) and with a high oxygen capacity. The frog mainly stays near the bottom and it has never been observed to surface in the wild, but captive studies indicate that it may surface to breathe using its diminutive lungs if the water is poorly oxygenated.[4][19][20]

Although a good swimmer, several individuals can often be seen laying inactively next to each other on the bottom.[6] Titicaca water frogs tend to be most active during the night.[24]

The Titicaca water frog breeds year-round in shallow coastal water where the female lays about 80 to 500 eggs.[4][21] Amplexus lasts one to three days.[16] The "nest" site is typically guarded by the male until the eggs hatch into tadpoles,[21] which happens after about one to two weeks.[16][25] The tadpole stage lasts for a couple of months to a year.[21] The tadpoles and young froglets stay in shallows, only moving to deeper water when reaching adulthood.[17] Maturity is typically reached when about three years old.[16]

The Titicaca water frog mostly feeds on amphipods (especially Hyalella) and snails (especially Heleobia and Biomphalaria),[17] but other food items are insects and tadpoles.[4] Adults also regularly eat fish (primarily Orestias, up to at least 10 cm [4 in] long) and cannibalism where large frogs eat small individuals has been recorded.[21][22][26] It has an extremely low metabolic rate; below that of all other frogs and among amphibians it is only higher than that of a few salamanders.[4][21][19]

In captivity, the tadpoles will feed on a range of tiny animals such as copepods, water fleas, small worms and aquatic insect larvae.[16]

Similar to at least some other Telmatobius species, male Titicaca water frogs will call underwater when near the shore. The simple and repeated call can only be detected with a submerged microphone from a relatively short distance. The function is not clear, but calling primarily occurs during the night and it is likely related to attracting females, courtship or aggression.[27]

The ears are greatly reduced and several of the structures, including the tympanic membrane and the Eustachian tubes, are absent. How the Titicaca water frog hears is unconfirmed, but it probably involves the lungs (as known from some other frogs).[27]

The Titicaca water frog has declined drastically, leading the IUCN to rank it as endangered.[1]

It was once common, with a survey in the late 1960s by Jacques Cousteau and colleagues counting 200 individuals in an only 1 acre (0.4 ha) plot of the huge lake.[13] Although not directly comparable, a survey in 2017 of three 100 m × 2 m (328 ft × 7 ft) transects at 38 locations only detected a total of 45 Titicaca water frogs at 6 of the locations (none at the remaining).[28] It is estimated that it declined by more than 80% in just 15 years, from 1990 to 2004, equalling three Titicaca water frog generations.[1][4][29] Several other species in the genus Telmatobius are facing similar risks.[3]

The causes of the precarious status of the Titicaca water frog are over-collecting for human consumption, pollution and introduced trout, and it may also be threatened by disease.[1][3]

The species is consumed as a traditional food or blended drink, and as traditional medicine that is claimed to be an aphrodisiac, and treat infertility, tuberculosis, anemia, asthma, osteoporosis and fever, but this is entirely unsupported by evidence.[30][31] Dishes with Titicaca water frogs are also sold by some local restaurants as a novelty to tourists.[29]

On a month-long expedition to Lake Titicaca 100 years ago, this frog was not seen in any of the markets in the region, no locals were seen hunting for it and when asked locals said they considered it inedible.[22] Whether this reporting was incomplete or there has been a significant change is unclear, but by the 2000s tens of thousands were caught for food and traditional medicine each year,[32] and even though now illegal the trade has to some extent continued.[31][33] Smaller numbers have been exported to other countries as food, for frog leather (skin) and the pet trade.[32]

Pollution from mining, agriculture and human waste has become a serious problem in the range of the Titicaca water frog.[1][3] Breathing through their skin, Titicaca water frogs easily absorb chemicals from the water. Additionally, nutrient-rich pollution from agriculture can cause algae blooms where oxygen levels plummet, asphyxiating the fully aquatic frog.[29]

Historically, smaller mass deaths occasionally occurred in this species, but they are now fairly common and since 2015 there have also been large mass deaths.[31][34] In April 2015, thousands of dead Titicaca water frogs were found in Bolivia on the shore of Lake Titicaca,[35] and in October 2016 an estimated 10,000 were found dead in the Coata River (a Lake Titicaca tributary). At least in the latter case, scientists believe pollution killed the frogs.[36][37] This is also supported by the timing of the mass deaths, which mostly occur in the rainy season where pollution likely is washed into the lake from the surroundings.[31]

Die-offs possibly are reversible. It has been observed that small Titicaca water frogs may appear in the vicinity of an affected area later, possibly recolonizing it.[29]

The introduced, non-native rainbow trout likely feed on tadpoles of the Titicaca water frog, the frogs are caught as bycatch in fishing nets set for trout, and coastal pens for farming trout overlap with the frog's breeding habitat and may impact it.[1][29] Lake Saracocha was home to Titicaca water frogs of the "albiventris" form, but they have not been found in later surveys and it is suspected that introduced trout were implicated in their apparent disappearance from this location.[6]

Rainbow trout was introduced on a US initiative from their original North American range to Lake Titicaca in 1941–42 to aid the local fisheries that had relied on the smaller native fish.[38][39] The fast-growing and relatively large non-native fish (trout and Argentinian silverside) are now the most important species in local fisheries, far exceeding the fisheries for the smaller natives (Orestias and Trichomycterus).[38][39] Because of the economic importance, these fisheries, along with trout farming, are supported by the local governments, making it unlikely that they would support any initiatives to reduce or even remove the trout from the region.[29]

Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, a fungus that causes the disease chytridiomycosis in frogs, has been present in the Andes for a long time. Although first definitely confirmed in Lake Titicaca in a study in 2012–2016,[40] a later study of museum specimens found it in several old Titicaca water frogs, one of them collected in 1863, which is the oldest known case of the fungus in the world.[41] However, this appears to involve a much less virulent form and widespread deaths of frogs in the highlands of Bolivia and Peru only began much later, in the 1990s, likely coinciding with the spread of a far more lethal form of the fungus.[41] The rapid declines, often closely linked to chytridiomycosis, have affected several of its relatives (some of them likely now extinct),[3][42] but the disease does not appear to have seriously affected the Titicaca water frog.[17][40] This may change with global warming if the water it lives in surpasses 17 °C (63 °F) for longer periods, which is the optimum temperature for the disease (it is lethal to many frog species at 17–25 °C [63–77 °F]),[17][40] or with increasing pollution, making the Titicaca water frogs more vulnerable to infection.[23] Another factor that may afford some protection to this frog is the slightly basic water (generally pH ≥7.5) of Lake Titicaca, as the fungus has the best growth rates in neutral or slightly acidic conditions (pH 6–7).[17][40]

The Titicaca water frog is regarded as one of the flagship species of Lake Titicaca,[33] and in 2019 Peru issued a 1 sol coin with an illustration of this frog as part of an endangered wildlife series.[43]

In 2013, it was one of the contenders for "ugliest animal", a humorous public vote arranged by the Ugly Animal Preservation Society, an organisation that attempts to draw attention to threatened species that lack the cuteness factor.[7]

In Peru, trade outside its native range at Lake Titicaca has been illegal in decades,[30] and in 2014 it was afforded full protection in the country, making it illegal to catch the species.[33] The Peruvian authorities have seized thousands of Titicaca water frogs that were illegally traded within the country.[30][31] In 2016–2017, it was legally protected from hunting in Bolivia.[33] Since 2016, commercial international trade has been prohibited because it is included on CITES Appendix I.[33][44]

Reserves where the frog occurs have been established,[33] and Lake Titicaca is recognized as a Ramsar site, but the protection provided by reserves in this region is often very limited.[29]

Bolivia and Peru have agreed to work together to resolve the environmental problems of Lake Titicaca, but corruption and the risk of local civil unrest might cause problems for the implementation of this.[38] In 2016, the two countries pledged to use 500 million US dollars on it, including new water treatment facilities; otherwise waste water has been led directly into the lake.[4][31]

Conservation projects specifically aimed at the Titicaca water frog have been initiated, some of them in cooperation between Bolivia and Peru, including population monitoring, studies to find the reason for the mass deaths and efforts to reduce the demand for the species as a food/traditional medicine.[33][34][35][45] Education projects have resulted in some former frog poachers instead becoming part of a handicraft collective that provides a small alternative income.[31] The possibility of offering ecotours where tourists can snorkel in a wetsuit and see the frogs is being considered at Isla de la Luna (where the species is still quite common), and a pilot project related to this was completed in 2017.[29]

In 2020, scientists from Bolivia's Science Museum and Natural History Museum, Peru's Cayetano Heredia University, Pontifical Catholic University in Ecuador, Denver Zoo in the US and the NGO NaturalWay teamed up for further conservation efforts.[46]

Following its rapid decline in the wild, it was decided in the early 2000s that a secure captive population should be established, which may form the basis for future reintroductions into places where it has disappeared.[34][35][45] Early captive breeding attempts were unsuccessful;[4] the only partial success was a few tadpoles hatched at the Bronx Zoo in the United States in the 1970s, but they did not metamorphose into frogs.[47]

The first fully successful captive breeding was relatively recent: In 2010 it was first bred at Huachipa Zoo in Lima, Peru, and in 2012 it was first bred at Museo de Historia Natural Alcide d'Orbigny in Cochabamba, Bolivia.[23][48][49] The breeding center in Bolivia is supported by Berlin Zoo, Germany,[15] and also involves several other threatened Bolivian frogs.[50] As a result of disagreement between the museum that provided space for it and the local biologists running it, it was briefly put on pause in 2018,[29] but has since been continued.[50]

In 2015, the breeding project initiated in Peru was expanded when a group of Titicaca water frogs bred at Huachipa Zoo was sent to Denver Zoo, United States,[23][47] which already supported the effort at Huachipa Zoo and was involved in the establishment of a laboratory and program working with the frogs at the Cayetano Heredia University in Lima, Peru.[49] The first successful captive breeding outside its native South America happened at the Denver Zoo in 2017–2018 (first tadpoles in 2017, first metamorphosis into young frogs in 2018).[51][52] In 2019, some offspring from Denver were transferred to other US zoos and some to Chester Zoo in the United Kingdom, which redistributed them among several European zoos in an attempt of establishing another safe population. Among the European institutions, Diergaarde Blijdorp, Münster Zoo, Prague Zoo, Wrocław Zoo and WWT Slimbridge already managed to breed it in the first year.[53]

In early 2019 (prior to the breeding at several European institutions and not counting those at the breeding center in Bolivia), there were about 3,000 Titicaca water frogs at the breeding center in Peru, and 250 in zoos in North America and Europe.[54] Captives have lived for up to 20 years.[23]

Telmatobius culeus, commonly known as the Titicaca water frog, is a medium-large to very large and endangered species of frog in the family Telmatobiidae. It is entirely aquatic and only found in the Lake Titicaca basin, including rivers that flow into it and smaller connected lakes like Arapa, Lagunillas and Saracocha, in the Andean highlands of Bolivia and Peru. In reference to its excessive amounts of skin, it has jokingly been referred to as the Titicaca scrotum (water) frog.

It is closely related to the more widespread and semiaquatic marbled water frog (T. marmoratus), which also occurs in shallow, coastal parts of Lake Titicaca, but lacks the excessive skin and it is generally smaller (although overlapping in size with some forms of the Titicaca water frog).

Telmatobius culeus, ofte konata kiel Titikaka rano aŭ Titikaka akvorano, estas tre granda draste endanĝerita specio de rano en la familio de Telmatobiedoj.[1] Ĝi estas tute akvoloĝantaj kaj troviĝas nur en la Lago Titikaka kaj riveroj kiuj fluas en tiun lagon en Sudameriko. Kvankam la pulmoj estas tre malpliigitaj, tiu rano havas grandajn kvantojn de haŭto, uzata por helpi la spiron de tiu rano en la alta altitudo en kiu ĝi loĝas.[2]

Kelkaj specioj de ranoj havas adaptaĵojn kiuj permesas ilin survivi en oksigenmanka akvo. La rano de la Lago Titikaka (Telmatobius culeus) estas unu tia specio kaj havas faldecan haŭton kiu pliigas sian surfacan areon por faciligi la gasan interŝanĝon. Ĝi normale ne faras uzadon de siaj rudimentaj pulmoj sed ĝi foje plialtigas kaj malaltigas sian korporitmon en la lagofundo por pliigi la fluadon de akvo ĉirkaŭ ĝi.[3]

Telmatobius culeus, ofte konata kiel Titikaka rano aŭ Titikaka akvorano, estas tre granda draste endanĝerita specio de rano en la familio de Telmatobiedoj. Ĝi estas tute akvoloĝantaj kaj troviĝas nur en la Lago Titikaka kaj riveroj kiuj fluas en tiun lagon en Sudameriko. Kvankam la pulmoj estas tre malpliigitaj, tiu rano havas grandajn kvantojn de haŭto, uzata por helpi la spiron de tiu rano en la alta altitudo en kiu ĝi loĝas.

Kelkaj specioj de ranoj havas adaptaĵojn kiuj permesas ilin survivi en oksigenmanka akvo. La rano de la Lago Titikaka (Telmatobius culeus) estas unu tia specio kaj havas faldecan haŭton kiu pliigas sian surfacan areon por faciligi la gasan interŝanĝon. Ĝi normale ne faras uzadon de siaj rudimentaj pulmoj sed ĝi foje plialtigas kaj malaltigas sian korporitmon en la lagofundo por pliigi la fluadon de akvo ĉirkaŭ ĝi.

La rana gigante del lago Titicaca (Telmatobius culeus) es una especie de anfibio anuro gigante de la familia Telmatobiidae.[2] Es endémica del lago Titicaca.

Especie de cuerpo grande, cabeza redondeada frontalmente, ancha y aplanada, tímpano oculto. Su principal característica es la piel, que es suave muy holgada en forma de un saco que cuelga en pliegues desprendidos. Su dorso es muy glandular provocando, cuando la especie es cogida con la mano, la secreción de una mucosa muy pegajosa no irritante. La piel puede ser verrugosa sobre los costados. La coloración del dorso es variable, desde olivo claro uniforme a oscuro con diferentes diseños que pueden variar desde motas blancas o puntos hasta parecer grises, ventralmente el color es más claro y uniforme pudiendo ser blanco, gris claro hasta anaranjado como generalmente se observa en el lago Menor. Los dedos anteriores son libres, los posteriores semiunidos. Largo del cuerpo mayor a 140 mm, pesan alrededor de 150g. Dependiendo del lugar de captura el tamaño es variable habiéndose encontrado los especímenes más grandes en los alrededores de la isla del Sol con más de 380 g (modificado de Garman 1875).

Debido al bajo contenido de oxígeno del Titicaca, Telmatobius culeus respira principalmente por medio de la piel. Es una especie exclusivamente acuática, y posee grandes pliegues de piel en todo el cuerpo. Los pliegues permiten aumentar absorción de oxígeno por la piel, una característica que se observa también en otros anfibios estrictamente acuáticos.[3]

A principios de la década de 1970, una expedición dirigida por Jacques Yves Cousteau informó de ejemplares de esta especie de ranas de hasta 50 cm de largo, con un peso de un kilogramo, es por ello la mayor rana acuática en el mundo.[cita requerida]

Es una especie endémica del lago Titicaca, Departamento de La Paz en Bolivia y Puno en Perú (Vellard, 1951, 1991), encontrándose en la ecorregión de la Puna Norteña (Ibisch et al., 2003).

Aunque la especie tiene aparentemente una amplia distribución en el lago Titicaca, se encuentra gravemente amenazada de extinción. En Bolivia está considerada como una especie amenazada desde 1996 (Ergueta & Harvey, 1996) y actualmente se encuentra categorizada como en peligro crítico de extinción por la UICN.(Aguayo & Harvey 2009).

La mayor amenaza reportada es la caza de adultos. Sus extremidades están siendo comercializadas desde hace varias décadas atrás. En el 2006 se reportaron más de 15000 individuos/año empleados en la elaboración de "ancas de rana". Se tienen denuncias en el sector boliviano del tráfico ranas en cantidades elevadas para ser comercializadas en forma de jugo de rana en la ciudad de Lima.[cita requerida] También existen reportes de un uso incipiente en forma de jugo en la ciudad de El Alto.[cita requerida] Por otro lado la gente local la utiliza como medicina tradicional, las ranas son raramente consumidas en sopas. No sólo la extracción para su venta la afecta directamente también, se ha observado gran mortalidad en época lluviosa (Pérez, 2002, 2005). Sólo se cuentan con observaciones del estado de sus poblaciones en el lago Menor, en el que se estima que en los últimos 10 años se produjo una disminución del 39% de la población (Aguayo & Harvey 2009).

Otra importante amenaza es la contaminación de las aguas del lago Titicaca. Si bien no se ha confirmado la contaminación por metales pesados en el lago Menor, la utilización de compuestos organoclorados y organofosforados afectan indirectamente a los animales, principalmente en la reproducción y pueden ocasionar mutaciones en los cromosomas. El uso de plaguicidas agrícolas es elevado en la zona circundante al lago Titicaca. Se han observado mutaciones aunque en muy bajo porcentaje y también amputaciones, posiblemente causadas por aves o las redes de pesca (Pérez, 2002). Otra amenaza aún no comprobada es la expansión de quitridiomicosis (se han observado varios individuos con daños en la piel sin conocer su causa).

Además de sus depredadores naturales como la gaviota (Larus serranus), todavía no se está confirmado la depredación de larvas y adultos por especies introducidas de peces (trucha arcoíris y pejerrey) (Pérez, 1998). En los estómagos se encuentran gran cantidad de parásitos nemátodos y helmintos.

En Bolivia la especie está amparada en el D.S. 25458 de Veda general indefinida, y la Ley del Medio ambiente 1333 (1992) en sus artículos 52 al 57. En 2020 se anunció la implementación de un programa binacional para su conservación amparado por un acuerdo realizado en 2018.[4]

La rana gigante del lago Titicaca (Telmatobius culeus) es una especie de anfibio anuro gigante de la familia Telmatobiidae. Es endémica del lago Titicaca.

Telmatobius culeus Telmatobius generoko animalia da. Anfibioen barruko Telmatobiidae familian sailkatuta dago, Anura ordenan.

Telmatobius culeus Telmatobius generoko animalia da. Anfibioen barruko Telmatobiidae familian sailkatuta dago, Anura ordenan.

La grenouille du lac Titicaca (Telmatobius culeus) est une espèce d'amphibiens de la famille des Telmatobiidae[1] endémique du lac Titicaca, en Amérique du Sud.

Elle est parfois dite « grenouille géante du lac Titicaca » car si la plupart des exemplaires ont 20 cm de long[2], les plus âgés peuvent atteindre 60 cm[3] pour un poids d'un kilo[4],[5].

Comme certains tritons, cette grenouille a une respiration cutanée, c'est-à-dire principalement par la peau. En effet, l'augmentation de la surface cutanée créée par les nombreux replis de peau est suffisante pour que cette grenouille n'ait pas besoin de ses poumons pour respirer.

Cette espèce ne vit que dans le lac Titicaca, situé à 3 810 m d'altitude entre la région de Puno au Pérou et le département de La Paz en Bolivie[6].

Telmatobius culeus est aujourd'hui en danger critique d'extinction[7] en raison de la pollution du lac due à l'agriculture et aux activités domestiques, ainsi que de l'extraction d'eau qui absorbe des individus[6].

La grenouille du lac Titicaca (Telmatobius culeus) est une espèce d'amphibiens de la famille des Telmatobiidae endémique du lac Titicaca, en Amérique du Sud.

La Rana del Titicaca (Telmatobius culeus, Garman, 1876), nota anche come "rana scroto"[1], è un anfibio appartenente alla famiglia dei Telmatobiidae.

La rana del Titicaca è un grande anfibio completamente acquatico. Ha una grande testa piatta con il muso rotondo; il disco dorsale è spesso e presenta una cavità buccale molto vascolarizzata.

Ha prominenti pieghe cutanee sul dorso, sulle parti laterali del corpo e sulle zampe posteriori; grazie ad esse è in grado di respirare attraverso la pelle senza la necessità di emergere.

Adattamenti per la vita acquatica ad alta quota sono:

Il Telmatobius culeus è la più grande rana acquatica del mondo. Alcuni esemplari raggiungono la lunghezza di 50 centimetri: da qui il nome di "rana gigante".[3]

Le dimensioni possono variare in base al sito:

Arturo Muñoz ipotizza che le dimensioni minori nelle aree più scarsamente popolate siano dovute alla presenza di esemplari più giovani che stanno ricolonizzando l'habitat.[1]

La rana del Titicaca respira principalmente attraverso le pieghe della pelle, ampiamente vascolarizzate, che servono essenzialmente da branchie; se l'acqua è ben ossigenata, questa specie non necessita di emergere.

In condizioni ipossiche, il Telmatobius culeus appare disteso sul fondale con gli arti stesi per rendere massima la sua esposizione all'acqua, facendo movimenti ascendenti e discendenti ogni circa 6 secondi per spostare le pieghe cutanee e assorbire la massima quantità di ossigeno.

I polmoni sono notevolmente ridotti e scarsamente vascolarizzati.[2]

L'habitat del Telmatobius culeus è distribuito in una regione tra Bolivia e Perù, all'interno del lago Titicaca, nei fiumi che vi sfociano e in stagni a circa 70 km di distanza nei pressi del lago Saracocha. Un singolo esemplare è stato segnalato nelle sorgenti calde vicino al Rio Yura, 200 km a est del lago Titicaca.

Il Titicaca è il lago più grande del Sud America; è situato a 3.812 metri di altezza e profondo 281 metri. La temperatura media è di 10 °C e l'acqua è satura di ossigeno a causa dei forti venti.[2]

La rana del Titicaca ha la capacità di eliminare alcuni parassiti sottomarini che possono insidiarsi nel suo habitat.[3]

La rana del Titicaca è completamente acquatica. Predilige il fondo del lago ma si può trovare anche su sporgenze rocciose sommerse vicine alla superficie e in tutta la colonna d'acqua.

Sotto stress secerne una secrezione bianca, appiccicosa e lattiginosa di cui le pieghe della pelle si riempiono. Sul lato peruviano del lago questa sostanza è consumata come afrodisiaco.[2]

La rana del Titicaca ha un tasso metabolico tra i più bassi riportati tra gli anfibi in condizioni non ipossiche (circa 14 microliti/grammo/ora). La sua dieta comprende:

La deposizione delle uova e l'allevamento si svolgono in acque poco profonde vicino al litorale; depone circa 500 uova.[2]

A seguito di un calo di esemplari dell'80% rispetto al 1990, nel 2004 la rana del Titicaca è stata aggiunta alla Lista Rossa IUCN che la classifica come "in pericolo di estinzione"; in seguito è stata inclusa anche nell'Appendice I della CITES in modo da limitarne la raccolta e il commercio illegali.[4]

Molti decessi possono essere attribuiti a sostanze inquinanti. La contaminazione delle acque deriva dall'eutrofizzazione delle alghe, prodotta con il rilascio artificiale di sostanze nutritive come azoto e fosforo nelle acque degli affluenti del lago. Ciò costringe la rana del Titicaca a sopravvivere in un habitat in cui la contaminazione ambientale produce concentrazioni di ammonio, nitrati, fosfati, nitriti e residui solidi sospesi che possono impedirne la riproduzione.[3]

Nel 2004 Perù e Bolivia hanno impegnato 500 milioni di dollari per ripulire il lago Titicaca, ma anche negli anni successivi si sono verificate serie di morti di massa. Le due più gravi si sono prodotte:

Episodi simili, anche se più ridotti, si erano verificati anche nel 2009, 2011 e 2013.[1]

La morte di massa in Bolivia del 2015 è stata prodotta da un deflusso carico di nutrienti, che ha causato la proliferazione di alghe che sottraggono ossigeno, idrogeno e zolfo e producono un gas neurotossico che ha ucciso parte della fauna lacustre.

Alcune popolazioni boliviane e peruviane attribuiscono proprietà curative alla rana del Titicaca e per questo, benché non sia commestibile, la consumano.[3]

Alcuni ristoranti turistici sulla costa boliviana offrono piatti a base di cosce di rana.[1]

La pesca consiste in un altro pericolo per questa specie poiché può essere catturata per errore. Inoltre, la volontà di incrementare la pesca ha prodotto il rilascio di specie non native nell'habitat. Negli anni quaranta del Novecento un milione e mezzo di uova di trota iridea del Michigan furono gettate dagli aerei nel lago Titicaca e ora le trote vi sono allevate intensivamente. Poco più tardi è stato introdotto dall'Argentina lo sgombro macchiato. Queste specie non native oggi costituiscono la base dell'economia regionale, ma sono dannose in quanto si nutrono di girini e piccoli pesci creando competizione nell'habitat.[1]

La chitidiomicosi, trasmessa dal Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, diffusosi grazie all'attività umana, è una malattia che causa l'inspessimento, l'irrigidimento e il rilassamento nella pelle degli anfibi infetti, lasciandoli incapaci di respirare e di assorbire acqua ed elettroliti attraverso la pelle. Il Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis è stato trovato nel lago nel 2011[4] e per il momento la sua proliferazione è controllata grazie alle basse temperature e all'alto pH del lago; ciò ha prodotto un limitato numero di casi di chitidiomicosi tra la popolazione di rane del Titicaca, che però è particolarmente esposta alla malattia.[1]

Il Telmatobius culeus è stato scoperto da Garman nel 1876. Poiché la specie presenta diversi colori secondo gradiente di profondità, era stata inizialmente ipotizzata una distinzione tra due specie: T. culeus e T. marmoratus. Tutte le sottospecie presunte sono però poi state assimilate a Telmatobius culeus.[2]

La rana del Titicaca fu resa famosa nel 1968 da Jacques Cousteau durante una spedizione subacquea sul fondo del lago. Egli stimò che il lago ne contenesse più di un miliardo.[1]

A causa dei suoi adattamenti alla vita ad alta quota, il Telmatobius culeus è una specie iconica.

Nel 2008 uno studio pilota di BirdLife International ha cercato le cause del declino della specie valutando inizialmente il numero di rane uccise e catturate. Ha poi rintracciato i principali terreni di riproduzione per sviluppare azioni mirate per la conservazione.[4] A seguito dello studio, è stato introdotto un programma di sensibilizzazione della popolazione locale, di monitoraggio e di allevamento delle rane del Titicaca.

Nel gennaio 2017 Pedro Pablo Kuczynski, presidente peruviano, ha annunciato la costruzione, da parte del governo, di dieci impianti per il trattamento delle acque intorno al lago Titicaca per ovviare al problema delle contaminazioni dovute ad attività minerarie, deflusso agricolo e acque reflue.

Nel 2017 è stato promosso un progetto pilota di ecoturismo su Isla de la Luna con lo scopo di attirare snorkelisti appassionati di rane, portando profitti alla popolazione locale che può offrire alloggio, cibo e trasporti. Questa iniziativa sta lavorando anche con la comunità di Isla de la Luna per stabilire un santuario delle rane intorno all'isola.[1]

L'erpetologo boliviano Arturo Muñoz, a capo di un team internazionale di biologi, ha prelevato esemplari di rana del Titicaca dal lago allo scopo allevarli e riprodurli in cattività e, in futuro, rilasciarli nelle aree dove saranno scomparsi. Il team ha realizzato due spedizioni:

Gli esemplari prelevati devono attraversare un periodo di purificazione e pulizia dai microorganismi nocivi per essere poi collocati in un contenitore appositamente progettato per la riproduzione in cattività nella città di Cochabamba.[3]

(EN) McKittrick, E., Saving the Scrotum Frog, su Earth Island Journal, 22 January 2020.

(EN) Lee, D.; A.T. Chang; M.S. Koo; K. Whittaker (eds.), Telmatobius culeus, su AmphibiaWeb, University of California, Berkeley, 23 January 2020.

(EN) Titicaca water frogs, su Berlin zoo, 4 January 2020.

(ES) Titicaca: Equipo internacional rescata a la rana gigante, su Erbol Digital, 2 March 2016 (archiviato dall'url originale il 16 settembre 2017).

La Rana del Titicaca (Telmatobius culeus, Garman, 1876), nota anche come "rana scroto", è un anfibio appartenente alla famiglia dei Telmatobiidae.

De Titicacakikker (Telmatobius culeus) is een kikker uit de familie Telmatobiidae. De kikker werd lange tijd tot de familie Ceratophryidae gerekend. De soort werd voor het eerst wetenschappelijk beschreven door Samuel Garman in 1875. Oorspronkelijk werd de wetenschappelijke naam Cyclorhamphus culeus gebruikt.[2]

Telmatobius culeus heeft een kop-romplengte van ongeveer 150 mm. De snuit is rondvormig. De ogen zijn relatief klein en een trommelvlies is niet aanwezig in het oor. De huid is nagenoeg glad en lijkt los te zitten van het lichaam. Hij komt veel voor in water met heel weinig zuurstof, en die loshangende flappen huid helpen hem extra zuurstof uit het water te halen. Het lichaam heeft een olijfgroene tot donker bruine kleur, maar de buik is crèmekleurig.[3]

Deze volledig aquatische soort kan goed zwemmen en duiken dankzij de zwemvliezen aan de achterpoten. De gaswisseling vindt plaats door de huid, die in oppervlak vergroot is door middel van huidplooien. De huid bevat veel bloedvaten en het bloed is rijk aan rode bloedcellen.

De soort komt voor in Zuid-Amerika, en is alleen bekend uit enkele hooggelegen meren in Peru en Bolivia, zoals het koude, zuurstofarme Titicacameer op de grens van Peru en Bolivia.[4]

In de tweede helft van 2016 werden zo'n 10.000 kikkerlijken aangetroffen in de Coatarivier, die uitmondt in het Titicacameer. De kikkers zouden het slachtoffer zijn van het vervuilde water.[5] De bevolking rond het meer nam de voorbije twintig jaar sterk toe en daarmee ook de vervuiling. Bovendien worden de kikkers plaatselijk beschouwd als een lekkernij, waardoor er erg op gejaagd wordt.

De reproductie wordt door Telmatobius culeus uitgevoerd in de ondiepe wateren vlak langs de oever van het meer.[6]

De Titicacakikker (Telmatobius culeus) is een kikker uit de familie Telmatobiidae. De kikker werd lange tijd tot de familie Ceratophryidae gerekend. De soort werd voor het eerst wetenschappelijk beschreven door Samuel Garman in 1875. Oorspronkelijk werd de wetenschappelijke naam Cyclorhamphus culeus gebruikt.

Telmatobius culeus é uma espécie de rã da família Leptodactylidae, popularmente conhecida como rã-do-titicaca, e é encontrada somente no lago Titicaca.[1] É conhecida pelo hábito aquático e por suas quantidades excessivas de pele. Este excesso de pele é usado para ajudar a rã a respirar na alta altitude de que reside.[2]

No princípio dos anos 70, uma expedição conduzida por Jacques-Yves Cousteau, reportou rãs com até 50 cm de comprimento, com indivíduos pesando um quilograma, fazendo destas rãs as maiores no mundo.[3]

Telmatobius culeus é uma espécie de rã da família Leptodactylidae, popularmente conhecida como rã-do-titicaca, e é encontrada somente no lago Titicaca. É conhecida pelo hábito aquático e por suas quantidades excessivas de pele. Este excesso de pele é usado para ajudar a rã a respirar na alta altitude de que reside.

No princípio dos anos 70, uma expedição conduzida por Jacques-Yves Cousteau, reportou rãs com até 50 cm de comprimento, com indivíduos pesando um quilograma, fazendo destas rãs as maiores no mundo.

Titicacapadda (Telmatobius culeus), även kallad Titicacagroda, är ett groddjur som är endemiskt för Titicacasjön, en sjö i Anderna på gränsen mellan Peru och Bolivia. Den är av IUCN rödlistad som akut hotad.[1]

Titicacapaddan har ett helt akvatiskt levnadssätt och är på flera sätt speciellt anpassad till att leva i Titicacasjöns syrefattiga, kalla vatten. För att underlätta dykning är lungorna små och det mesta syre den behöver tar den upp genom sin påfallande veckade och rikt blodkärlsförsedda hud. Den veckade huden är ett av artens främsta yttre kännetecken och hudveckens funktion är att öka kroppsytan och därmed förmåga att ta upp syre. En annan anpassning till ett liv i syrefattigt vatten är att dess blod är mycket rikt på syreupptagande blodceller.[2]

Titicacapaddan har gått från att tidigare ha varit vanlig i Titicacasjön till att numera vara sällsynt eller helt försvunnen från många områden. Populationens minskning beräknades i rödlistningen vara över 80 procent över tre generationer. Orsakerna till tillbakagången är främst överexploatering genom allt för omfattande fångst av de fullvuxna djuren, habitatförstörelse och hot från introducerade arter, som inplanterade fiskar vilka äter upp Titicacapaddans yngel. Försök att få infångade individer att fortplanta sig i fångenskap omkring Titicacasjön har generellt sett ännu inte varit framgångsrika.[1]

Titicacapadda (Telmatobius culeus), även kallad Titicacagroda, är ett groddjur som är endemiskt för Titicacasjön, en sjö i Anderna på gränsen mellan Peru och Bolivia. Den är av IUCN rödlistad som akut hotad.

Ếch Titicaca (Danh pháp khoa học: Telmatobius culeus) là một loài ếch nước ngọt cỡ lớn trong họ Telmatobiidae, chúng được xếp loại là loài cực kỳ nguy cấp[1][5][6][7], là loài ếch lớn chỉ có duy nhất ở hồ Titicaca. Ngày nay ếch Titicaca đã giảm mạnh và hiện đang phải đối mặt với nguy cơ tuyệt chủng do con người, sự ô nhiễm, và sự ăn thịt con nòng nọc của cá hồi du nhập xâm chiếm lãnh thổ.

Chúng sống hoàn toàn dưới nước và chỉ được tìm thấy ở hồ Titicaca và con sông chảy vào hồ này ở Nam Mỹ. Trong khi phổi được giảm đi rất nhiều, ếch này có quá nhiều da, được sử dụng để giúp thở ếch ở độ cao rất cao. Khi hình dung về lớp da bầy nhầy của nó, nó cũng được gọi đùa là ếch bìu Titicaca. Chúng có những lớp da xếp nếp khổng lồ có khả năng giúp tăng rộng bề mặt cơ thể và giúp cho chúng hấp thụ được nhiều ô-xi hơn[8].

Trong những năm 1970, một đoàn thám hiểm dẫn đầu bởi Jacques Cousteau báo cáo rằng ếch này có chiều dài lên đến 50 cm (20 in) chiều dài duỗi thẳng, với các cá thể thường có trọng lượng 1 kg (2.2 lb), làm cho các một số các loài ếch nước ngọt lớn nhất thế giới (trừ loài Batrachophagous macrostomus là có kích thước lớn hơn, như là ếch Goliath châu Phi, mà đôi khi có thể được nhìn thấy trên đất).

Ếch Titicaca (Danh pháp khoa học: Telmatobius culeus) là một loài ếch nước ngọt cỡ lớn trong họ Telmatobiidae, chúng được xếp loại là loài cực kỳ nguy cấp, là loài ếch lớn chỉ có duy nhất ở hồ Titicaca. Ngày nay ếch Titicaca đã giảm mạnh và hiện đang phải đối mặt với nguy cơ tuyệt chủng do con người, sự ô nhiễm, và sự ăn thịt con nòng nọc của cá hồi du nhập xâm chiếm lãnh thổ.

Telmatobius culeus (Garman, 1876)

СинонимыТитикакский свистун[1] (лат. Telmatobius culeus) — вид бесхвостых земноводных из семейства Ceratophryidae. Эндемик озера Титикака. Для дыхания в основном использует свою кожу, складки которой увеличивают дыхательную поверхность.

Длина тела титикакского свистуна составляет около 15 см. Нос островато-закруглённый, глаза относительно маленькие и поднимаются над спинной стороной тела, барабанная перепонка незаметна. Кожа гладкая, складчатая. Пальцы длинные, с узкими закруглёнными концами, на передних конечностях прямые, на задних изогнутые. Окраска спинной стороны тела тёмно-оливковая или тёмно-коричневая, иногда со светлыми пятнами. Брюхо кремово-серого цвета.

Титикакский свистун обитает в озере Титикака и нескольких ближайших озёр на плато Альтиплано, на высоте около 3810 м над уровнем моря. Населяет тёплые прибрежные районы озёр, где температура превышает +10° C.

Живёт в относительно холодной воде с большим количеством кислорода, в результате имеет низкий уровень метаболизма, а небольшие лёгкие указывают на то, что большая часть дыхания происходит через кожу. Как правило, эта лягушка не использует свои рудиментарные лёгкие. Наблюдения показали, что представители этого вида, находясь на дне озера, время от времени совершают ритмичные движения вверх-вниз, что увеличивает течение воды вокруг них[2].

Титикакский свистун (лат. Telmatobius culeus) — вид бесхвостых земноводных из семейства Ceratophryidae. Эндемик озера Титикака. Для дыхания в основном использует свою кожу, складки которой увеличивают дыхательную поверхность.

的的喀喀湖蛙,又名的的喀喀青蛙[2]。是世界上极危物种,属于珍稀保护生物。2004年被列入了“世界自然保护联盟濒危物种红色名录”。生活在南美洲淡水湖的的喀喀湖。[3]它是完全水生生物,只发现在南美洲的的喀喀湖与流入这个湖的河流。它们的肺已经退化,主要通过皮肤来呼吸。尤其是在高海拔地区,大面积的皮肤使得它们可以更加有效地吸收氧气。[4],參考華盛頓公約(CITES)第17次會員大會最新物種附錄修正,將的的喀喀湖蛙調整為保育類。

由於其皮肤鬆弛,它们也被开玩笑地称为的的喀喀阴囊水蛙(Titicaca scrotum water frog)。[5] 在20世纪70年代初,由雅克·库斯托领导的探险队报告的的喀喀湖蛙长约50厘米(20英寸),体重1公斤(2.2磅)左右。其頭尾長为7.5-13.8厘米(3.0-5.4英寸)。有时可以在陆地上看到。[4]

的的喀喀湖蛙数量已经急剧下降,现在面临灭绝,主要由于人类过度收集和消耗,以及污染加上引进其天敌鳟鱼捕食。[2]它也可能受到食管菌病的威胁。[2]属于的的喀喀湖蛙的几个其他种类,都面临类似的风险。[2]

在2016年10月,在的的喀喀湖的10000只湖蛙死亡,大大减少了它们的数量。 科学家认为是污染杀死了湖蛙。[6][7]

的的喀喀湖蛙是最大水生蛙种。它极其鬆弛的皮肤會呈褶皱狀從从其身体的多个部分垂悬下來。

的的喀喀湖蛙主要是食用小型动物、昆虫、蜗牛和鱼等。

的的喀喀湖蛙,又名的的喀喀青蛙。是世界上极危物种,属于珍稀保护生物。2004年被列入了“世界自然保护联盟濒危物种红色名录”。生活在南美洲淡水湖的的喀喀湖。它是完全水生生物,只发现在南美洲的的喀喀湖与流入这个湖的河流。它们的肺已经退化,主要通过皮肤来呼吸。尤其是在高海拔地区,大面积的皮肤使得它们可以更加有效地吸收氧气。,參考華盛頓公約(CITES)第17次會員大會最新物種附錄修正,將的的喀喀湖蛙調整為保育類。

由於其皮肤鬆弛,它们也被开玩笑地称为的的喀喀阴囊水蛙(Titicaca scrotum water frog)。 在20世纪70年代初,由雅克·库斯托领导的探险队报告的的喀喀湖蛙长约50厘米(20英寸),体重1公斤(2.2磅)左右。其頭尾長为7.5-13.8厘米(3.0-5.4英寸)。有时可以在陆地上看到。