fr

noms dans le fil d’Ariane

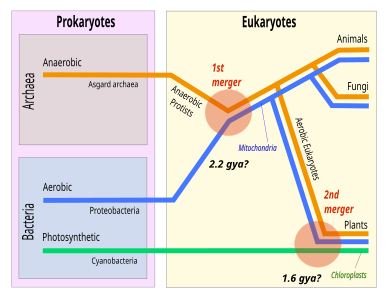

Die Asgard-Supergruppe, vorschlagsgemäß auch als auch Asgardarchaeota bezeichnet,[1] ist eine Klade von Archaeen[2] im vorgeschlagenes Rang eines Superphylums, zu der (u. a.) die vorgeschlagenen Phyla „Lokiarchaeota“, „Thorarchaeota“, „Odinarchaeota“ und „Heimdallarchaeota“ gehören.[3] Während die frühen Hinweise nur aus Metagenom-Daten stammten, wurde inzwischen der erste Vertreter der Gruppe kultiviert.[4] Das Asgard-Superphylum stellt die nächsten prokaryotischen Verwandten der Eukaryoten dar,[5] die möglicherweise aus einer Vorfahrenlinie der Asgardarchaeota hervorgegangen sind, nachdem sie Bakterien durch den Prozess der Symbiogenese zu Mitochondrien oder mitochondrien-ähnliche Organellen (mitochondria-like organelles, MROs) assimiliert haben.[5][6]

Im Sommer 2010 wurden Sedimente aus einem Bohrkern analysiert, der im Rifttal auf dem Knipowitsch-Rücken[Anm. 1] zwischen Grönland und Spitzbergen im Arktischen Ozean entnommen wurde. Der Entnahmeort war in der Nähe des Hydrothermalschlots namens Lokis Schloss[7] (Loki's Castle 73,55° N, 8,15° O73.558.15), einem sog. „Schwarzen Raucher“. Weil vorherige Untersuchungen auf neuartige Archaeen-Linien hingedeutet hatten, wurden die Proben einer Metagenomanalyse unterzogen, die diese Vermutung bestätigten.[8][9]

Nach dem positiven Ergebnis der ersten Analysen wurden die Proben von einem Team unter Führung der Universität Uppsala einer phylogenetischen Analyse unterzogen, die eine Anzahl von hochkonservierter Protein-kodierender Gene zum Gegenstand hatte. Als Ergebnis schlug das Team im Jahr 2015 das neue Archaeenphylum „Lokiarchaeota“ für die aus der Metagenomik identifizierten Gensequenzen (Contigs) vor.[10]

Der Name ist ein Verweis auf den Schwarzen Raucher, von dem die erste Metagenomprobe stammte, und bezieht sich der Name auf Loki, einer der vielschichtigsten und wandlungsfähigsten Gestalten des nordischen Pantheons.[11] Der mythologische Loki wurde beschrieben als „eine atemberaubend komplexe, verwirrende und ambivalente Figur, die Ursache unzähliger ungelöster wissenschaftlicher Kontroversen war“,[12] ganz analog zur Rolle der Lokiarchaeota in den Debatten über den Ursprung der Eukaryoten.[10][13]

Im Jahr 2016 entdeckte ein anderes Team unter Leitung der University of Texas in Proben aus Sedimenten im Mündungsgebiet (Ästuarsedimenten) des White Oak River (34,8835° N, 77,2216° W34.883466-77.221597) in North Carolina eine weitere, verwandte Gruppe von Archaeen, die Thorarchaeota benannt wurde nach Thor, einem weiteren nordischen Gott.[14]

Weitere Proben von Lokis Schloss, dem Yellowstone-Nationalpark, der Aarhus-Bucht, einem Grundwasserleiter (Aquifer) in der Nähe des Colorado River, dem Radiata Pool in Neuseeland (Ngatamariki, bei der Stadt Taupo und dem gleichnamigen Supervulkan, Nordinsel),[15][16] Hydrothermalquellen in der Nähe der Taketomi-Insel, Japan, und der Mündung des White Oak River in den Vereinigten Staaten führten dazu, dass weitere verwandte Gruppen entdeckt wurden, Odinarchaeota und Heimdallarchaeota,[3] und entsprechend der Namenskonvention nach Odin bzw. Heimdall benannt wurden. Das Superphylum, das diese Mikroben enthält, bekam dann konsequenterweise den Namen „Asgard“, nach dem Wohnort der Götter in der nordischen Mythologie.[3]

Im Jahr 2021 erweiterte die vergleichende Analyse von 162 Asgard-Genomen die phylogenetische Vielfalt dieser Supergruppe erheblich und führte zum Vorschlag von sechs zusätzlichen Phyla, einschließlich einer basalen Klade, die vorläufig Wukongarchaeota genannt wird. In mehreren dieser Phyla wurden weitere Homologe von Proteinen entdeckt, die für Eukaryoten charakteristisch sind. Die deutet auf eine dynamische Evolution durch horizontalen Gentransfer, Genverlust und -verdopplung und sogar Cross-Domain-Shuffling hin. Die Studie erlaubt jedoch noch nicht, zwischen den beiden möglichen Positionen des letzten gemeinsamen Vorfahren der Eukaryoten (LECA) zu entscheiden: entweder einer Schwesterklade der Heimdallarchaeota-Wukongarchaeota-Klade innerhalb von Asgard (wie im Kladogramm unten) oder einer Schwesterklade von Asgard selbst (innerhalb der Archaea).[17]

Die Asgard-Mitglieder kodieren eine Vielzahl eukaryotischer Signaturproteine (ESPs),[18] darunter neuartige GTPasen, membranumbauende Proteine (en. membrane-remodelling proteins, wie ESCRT und SNF7), ein Ubiquitin-Modifizierungssystem und N-Glykosylierungspfad-Homologe.[3]

Asgard-Archaeen haben ein reguliertes Aktin-Zytoskelett, und die von ihnen verwendeten Profiline und Gelsoline können mit eukaryotischen Aktinen interagieren.[19][20][21] Sie scheinen auch Vesikel zu bilden, wie unter dem Kryoelektronenmikroskopie (Kryo-EM) zu erkennen ist. Einige scheinen S-Layer-Proteine mit einer PKD-Domäne (en. polycystic kidney disease domain) zu haben.[4] Außerdem haben sie wie Eukaryoten in der größten Untereinheit der ribosomalen RNA, der LSU-rRNA (large subunit of ribosomal RNA) eine dreifache Erweiterung ES39 (expansion segment 39)[22][23]

Die Vielfalt an CRISPR-Cas-verwandten Systemen ist ein spezielles Merkmal der Asgard-Archaeen, das bei Eukaryoten nicht vorkommt.[24]

Stoffwechselwege der Asgard-Archaeen für einige der Phyla.[25]

Stoffwechselwege von Asgard-Archaeen, je nach Umgebung.[25]

Asgard-Archaeen sind obligate Anaerobier. Sie haben einen Wood-Ljungdahl-Weg und führen Glykolyse durch. Die Mitglieder dieser Gruppe können autotroph, heterotroph oder phototroph mit Heliorhodopsin sein.[25] Ein Mitglied, Candidatus Prometheoarchaeum syntrophicum, führt Syntrophie mit einem schwefelreduzierenden Proteobakterium und einem methanogenen Archaeon durch.[4]

Ihre RuBisCO-Versionen sind nicht kohlenstofffixierend, sondern werden wahrscheinlich für das Nukleosid-Salvage (en. nucleoside salvaging) verwendet.[25]

Im Jahr 2017 wurde entdeckt, dass die Vertreter des vorgeschlagenen Phylums Heimdallarchaeota N-terminale Core-Histon-Arme (corehistone tails) haben, ein Merkmal, von dem man zuvor annahm, dass es ausschließlich bei Eukaryoten vorkommt. Bei zwei weiteren Archaeen-Phyla, die nicht Asgard angehören, wurde 2018 ebenfalls dieses Merkmal gefunden, und zwar in „Huberarchaeota“ (DPANN) und „Bathyarchaeota“ (TACK).[26]

Im Januar 2020 fanden Wissenschaftler Candidatus Prometheoarchaeum syntrophicum, ein Mitglied der Lokiarchaeota, der eine Syntrophie mit zwei Bakterienarten eingeht. Dieser Befund zeigt, dass Asgard-Archaeen zu komplexen Syntrophien in der Lage sind, eine Voraussetzung für die von der Eozyten-Hypothese behauptete Entwicklung von den Archaeen hin zu komplexen eukaryotischen Mikroorganismen, wie sie vor etwa zwei Milliarden Jahren durch Symbiogenese entstanden sind.[27][4][Anm. 2]

Die phylogenetischen Beziehungen innerhalb der Asgard-Supergruppe sind noch in der Diskussion.

Die „Heimdallarchaeota“ (und ggf. ihnen nahestehende Gruppen) gelten als die am tiefsten verzweigten Asgard-Archaea.[4] Die Eukaryoten können Schwesterklade Asgard-Archae als ganzes oder der Heimdallarchaeota bzw. der nahe verwandten Idunnarchaeota sein.[28][29] Ein bevorzugtes Szenario ist die Syntrophie, bei der ein Organismus auf die Ernährung des anderen angewiesen ist. In diesem Fall könnte die Syntrophie darauf zurückzuführen sein, dass die Asgard-Archaea in eine unbekannte Bakterienart inkorporiert wurden und sich zum Zellkern entwickelten. Ein α-Proteobakterium wurde inkorporiert, und entwickelte sich so zum Mitochondrium zu werden.[28]

Die verwandtschaftlichen Verhältnisse der Mitglieder sind ungefähr wie folgt:[5][6][17][29]

Die Asgard-Archaeen zerfallen danach in zwei Kladen (um die „Lokiarchaeota“ und um die „Heimdallarchaeota“). Nach Caceres (2019) sollten sich noch die Idunnarchaeota zur Klade aus Heimdall- und Kariarchaeota hinzugesellen. Dieser phylogenetische Baum spiegelt die Erkenntnis wider, dass die DNA rezenter (heutiger) Asgard-Archaeen enger mit der DNA in den eukaryotischen Zellkernen verwandt ist, als mit der DNA anderen Archaeen.[30]

Namensherkunft:

Weitere vorgeschlagene Mitgiedsphyla:

Nach Farag et al. (2021) scheinen die „Sifarchaeota“ am nächsten mit den „Thorarchaeota“ verwandt zu sein. Die „Thorarchaeota“ sind bei diesen Autoren (mit den „Sifarchaeota“) aber im Asgard-Zweig der „Heimdallarchaeota“ angesiedelt, und nicht bei den Lokiarchaeota.[51]

In beiden Fällen lässt sich die Asgard-Supergruppe (so wie im Kladogramm) im engeren Sinn auffassen, dann ist diese möglicherweise paraphyletisch, da die Eukaryoten von ihrem letzten gemeinsamen Vorfahren (last common ancestor, LCA) (und den α─Proteobacteria) abstammen. Alternativ Fasst man diese Gruppen im weiteren Sinn auf, dann sind die Eukaryoten ebenfalls (sehr weit entwickelte) Asgard-Mitglieder.

Diese Bezeichnung umfasst explizit alle Asgard-Archaeen zusammen mit den Eukaryoten.

Die Problematik setzt sich unter dieser Annahme in den höheren taxonomischen Rängen fort, bis hin zur Domäne. Man kann die Bezeichnung Archaea (Archaeen) im weiten Sinn verstehen (inklusive Eukaryoten), dann wären diese monophyletisch. Es gäbe nur zwei Domänen: Neben den so erweiterten Archaeen nur noch die Bacteria (Bakterien). Oder man versteht den Begriff Archaeen im engen Sinn und behält den bisherigen Sprachgebrauch bei, dann ist diese Gruppe paraphyletisch. Als taxonomischer Oberbegriff, der Archaeen und Eukaryoten umfasst, wurde 2020 von Cavalier-Smith und Chao die Bezeichnung „Neomura“ vorgeschlagen, dies wäre dann eine Schwestergruppe der Bacteria.[60][Anm. 3]

Der taxonomische Rang der Asgard-Klade und ihrer Teilgruppen ist derzeit (2019/2021) noch in Diskussion.[29] Je nach Rang tragen die bezeichneten Taxa dann Namen mit je nach Autor unterschiedlichen Endungen. Ein Beispiel die Synonyme:

Sun et al. (2021) sehen die oben bezeichneten Phyla eher als Klassen, was sich in der Endung „-archaia“ statt „-archaeota“ niederschlägt. So sind zum Beispiel Synonyme:

In dieser Notation würde der Stammbaum der Eukaryomorpha etwa so aussehen:[61]

Dieser Baum führt eine weitere von diesen Autoren vorgeschlagene Asgard-Subklade als Klasse auf:

Die Asgard-Supergruppe, vorschlagsgemäß auch als auch Asgardarchaeota bezeichnet, ist eine Klade von Archaeen im vorgeschlagenes Rang eines Superphylums, zu der (u. a.) die vorgeschlagenen Phyla „Lokiarchaeota“, „Thorarchaeota“, „Odinarchaeota“ und „Heimdallarchaeota“ gehören. Während die frühen Hinweise nur aus Metagenom-Daten stammten, wurde inzwischen der erste Vertreter der Gruppe kultiviert. Das Asgard-Superphylum stellt die nächsten prokaryotischen Verwandten der Eukaryoten dar, die möglicherweise aus einer Vorfahrenlinie der Asgardarchaeota hervorgegangen sind, nachdem sie Bakterien durch den Prozess der Symbiogenese zu Mitochondrien oder mitochondrien-ähnliche Organellen (mitochondria-like organelles, MROs) assimiliert haben.

Asgard or Asgardarchaeota[2] is a proposed superphylum consisting of a group of archaea that contain eukaryotic signature proteins.[3] It appears that the eukaryotes, the domain that contains the animals, plants, and fungi, emerged within the Asgard,[4] in a branch containing the Heimdallarchaeota.[5] This supports the two-domain system of classification over the three-domain system.[6][7]

In the summer of 2010, sediments were analysed from a gravity core taken in the rift valley on the Knipovich ridge in the Arctic Ocean, near the Loki's Castle hydrothermal vent site. Specific sediment horizons previously shown to contain high abundances of novel archaeal lineages were subjected to metagenomic analysis.[8][9] In 2015, an Uppsala University-led team proposed the Lokiarchaeota phylum based on phylogenetic analyses using a set of highly conserved protein-coding genes.[10] The group was named for the shape-shifting Norse god Loki, in an allusion to the hydrothermal vent complex from which the first genome sample originated.[11] The Loki of mythology has been described as "a staggeringly complex, confusing, and ambivalent figure who has been the catalyst of countless unresolved scholarly controversies",[12] analogous to the role of Lokiarchaeota in the debates about the origin of eukaryotes.[10][13]

In 2016, a University of Texas-led team discovered Thorarchaeota from samples taken from the White Oak River in North Carolina, named in reference to Thor, another Norse god.[14] Samples from Loki's Castle, Yellowstone National Park, Aarhus Bay, an aquifer near the Colorado River, New Zealand's Radiata Pool, hydrothermal vents near Taketomi Island, Japan, and the White Oak River estuary in the United States contained Odinarchaeota and Heimdallarchaeota;[3] following the Norse deity naming convention, these groups were named for Odin and Heimdallr respectively. Researchers therefore named the superphylum containing these microbes "Asgard", after the home of the gods in Norse mythology.[3] Two Lokiarchaeota specimens have been cultured, enabling a detailed insight into their morphology.[15]

Asgard members encode many eukaryotic signature proteins, including novel GTPases, membrane-remodelling proteins like ESCRT and SNF7, a ubiquitin modifier system, and N-glycosylation pathway homologs.[3]

Asgard archaeons have a regulated actin cytoskeleton, and the profilins and gelsolins they use can interact with eukaryotic actins.[16][17] In addition, Asgard archaea tubulin from hydrothermal-living Odinarchaeota (OdinTubulin) was identified as a genuine tubulin. OdinTubulin forms protomers and protofilaments most similar to eukaryotic microtubules, yet assembles into ring systems more similar to FtsZ, indicating that OdinTubulin may represent an evolution intermediate between FtsZ and microtubule-forming tubulins.[18] They also seem to form vesicles under cryogenic electron microscopy. Some may have a PKD domain S-layer.[19] They also share the three-way ES39 expansion in LSU rRNA with eukaryotes.[20]

Metabolic pathways of Asgard archaea, varying by phyla[21]

Metabolic pathways of Asgard archaea, varying by environment[21]

Asgard archaea are generally obligate anaerobes, though Kariarchaeota, Gerdarchaeota and Hodarchaeota may be facultative aerobes.[22] They have a Wood–Ljungdahl pathway and perform glycolysis. Members can be autotrophs, heterotrophs, or phototrophs using heliorhodopsin.[21] One member, Candidatus Prometheoarchaeum syntrophicum, is syntrophic with a sulfur-reducing proteobacteria and a methanogenic archaea.[19]

The RuBisCO they have is not carbon-fixing, but likely used for nucleoside salvaging.[21]

Asgard are widely distributed around the world, both geographically and by habitat. Many of the known clades are restricted to sediments, whereas Lokiarchaeota, Thorarchaeota and another clade occupy many different habitats. Salinity and depth are important ecological drivers for most Asgard archaea. Other habitats include the bodies of animals, the rhizosphere of plants, non-saline sediments and soils, the sea surface, and freshwater. In addition, Asgard are associated with several other microorganisms.[23]

The phylum Heimdallarchaeota was found in 2017 to have N-terminal core histone tails, a feature previously thought to be exclusively eukaryotic. Two other archaeal phyla, both outside of Asgard, were found to also have tails in 2018.[24]

In January 2020, scientists found Candidatus Prometheoarchaeum syntrophicum, a member of the Lokiarcheota, engaging in cross-feeding with two bacterial species. Drawing an analogy to symbiogenesis, they consider this relationship a possible link between the simple prokaryotic microorganisms and the complex eukaryotic microorganisms occurring approximately two billion years ago.[25][19]

The phylogenetic relationships of the Asgard archaea are still under discussion.

In 2023, Eme, Tamarit and colleagues reported that the Eukaryota are deep within Asgard, as sister of Hodarcheales within the Heimdallarchaeia.[30]

Asgard Heimdallarchaeia

In the depicted scenario, the Eukaryota are deep in the tree of Asgard. A favored scenario is syntrophy, where one organism depends on the feeding of the other. An α-proteobacterium was incorporated to become the mitochondrion.[32] In culture, extant Asgard archaea form various syntrophic dependencies.[33] Gregory Fournier and Anthony Poole have proposed that Asgard is part of "the Eukaryote tree", forming a superphylum they call "Eukaryomorpha" defined by "shared derived characters" (eukaryote signature proteins).[34]

The taxonomy is uncertain and the phylum names are therefore somewhat speculative. The list of phyla is based on the List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature (LPSN)[35] and National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI).[36]

Several family-level groups of viruses associated with Asgard archaea have been discovered using metagenomics.[37][38][39] The viruses were assigned to Lokiarchaeia, Thorarchaeia, Odinarchaeia and Helarchaeia hosts using CRISPR spacer matching to the corresponding protospacers within the viral genomes. Two groups of viruses (called 'verdandiviruses') are related to archaeal and bacterial viruses of the class Caudoviricetes, i.e., viruses with icosahedral capsids and helical tails;[37][39] two other distinct groups (called 'skuldviruses') are distantly related to tailless archaeal and bacterial viruses with icosahedral capsids of the realm Varidnaviria;[37][38] and the third group of viruses (called wyrdviruses) is related to archaea-specific viruses with lemon-shaped virus particles (family Halspiviridae).[37][38] The viruses have been identified in deep-sea sediments[37][39] and a terrestrial hot spring of the Yellowstone National Park.[38] All these viruses display very low sequence similarity to other known viruses but are generally related to the previously described prokaryotic viruses,[40] with no meaningful affinity to viruses of eukaryotes.[41][37]

In addition to viruses, several groups of cryptic mobile genetic elements have been discovered through CRISPR spacer matching to be associated with Asgard archaea of the Lokiarchaeia, Thorarchaeia and Heimdallarchaeia lineages.[37][42] These mobile elements do not encode recognizable viral hallmark proteins and could represent either novel types of viruses or plasmids.

Asgard or Asgardarchaeota is a proposed superphylum consisting of a group of archaea that contain eukaryotic signature proteins. It appears that the eukaryotes, the domain that contains the animals, plants, and fungi, emerged within the Asgard, in a branch containing the Heimdallarchaeota. This supports the two-domain system of classification over the three-domain system.

Asgardarchaeota, Asgard o Asgardia es un filo o supergrupo de arqueas recientemente definido.[2][3] Se identificó inicialmente mediante análisis genético y posteriormente pudo ser cultivado.[4] Este grupo ha despertado gran interés debido a que el análisis filogenético ha revelado que está íntimamente relacionado con el origen de los seres eucariotas, es decir, un arquea del grupo Asgard sería el ancestro procariota directo de la primera célula eucariota.[5] Inicialmente el grupo se denominó Lokiarchaeota,[6] el cual se ha redefinido en varias clases.

Metabolismo: De acuerdo a los estudios metagenómicos, puede haber autotrofía anaerobia, dependencia del hidrógeno, organotrofía dependiente de hidrocarburos de cadena corta, fototrofía a base de rodopsina[7] y sintrofía.

El análisis genómico ha revelado que hay varios componentes homólogos con los eucariontes relacionados con la maquinaria de transporte celular, encontrando genomas enriquecidos con proteínas que anteriormente estaban consideradas específicas para eucariotas; lo que abre una ventana en la búsqueda del origen de la complejidad celular eucariota.

Los genomas de las arqueas Asgard codifican un repertorio de proteínas que son características de los eucariontes, incluidas las involucradas en el tráfico membranal, la formación y/o transporte de vesículas, la ubiquitina y la formación del citoesqueleto.[5]

El nombre "Asgard", alude al recinto de los dioses de acuerdo con la mitología nórdica, debido a que el primer género identificado fue Lokiarchaeum, tras realizar un análisis metagenómico (destructivo) de una muestra de sedimentos centro-oceánicos que se obtuvo a 15 km de una fuente hidrotermal conocida como el Castillo de Loki, sobre la Dorsal de Gakkel en el océano Ártico (mar de Groenlandia), en el sedimento del fondo marino a 2.352 metros de profundidad, 0,3°C y sin señales de vida eucariota.[8]

La primera especie cultivada, Candidatus Prometheoarchaeum syntrophicum MK-D1 es una pequeña célula en forma de coco de alrededor de 550 nm de diámetro con largos tentáculos a menudo ramificados. Es un organismo anaeróbico de crecimiento extremadamente lento, sin orgánulos visibles que degrada los aminoácidos mediante sintrofía. Se extrajo del sedimento marino en la fosa de Nankai (Japón) a 2500 metros de profundidad y a una temperatura dos grados.[4]

Se ha propuesto que el clado que agrupa a las arqueas Asgard con los eucariontes puede denominarse "Eukaryomorpha".[9] Asgard o Asgardarchaeota es un taxón que puede considerarse parafilético debido a que está relacionado con el origen de los eucariontes del siguiente modo:[1][10]

Eukaryomorpha + α─proteobacteriaAsgardarchaeota, Asgard o Asgardia es un filo o supergrupo de arqueas recientemente definido. Se identificó inicialmente mediante análisis genético y posteriormente pudo ser cultivado. Este grupo ha despertado gran interés debido a que el análisis filogenético ha revelado que está íntimamente relacionado con el origen de los seres eucariotas, es decir, un arquea del grupo Asgard sería el ancestro procariota directo de la primera célula eucariota. Inicialmente el grupo se denominó Lokiarchaeota, el cual se ha redefinido en varias clases.

Les archées d'Asgård (Asgardarchaeota), ou simplement Asgards, forment un super-embranchement d'archées découvert en 2015 dans des sédiments profonds à proximité du château de Loki, une source hydrothermale au large de la Norvège. Ils ont été nommés d'après le domaine des dieux dans la mythologie nordique[a].

Les Asgards partagent des traits que l'on croyait réservés aux eucaryotes. De ce fait, on considère généralement que le clade qui les inclut inclut aussi les Eukaryota, à ceci près que ces derniers sont issus de l'endosymbiose d'au moins une α-protéobactérie (devenue leur mitochondrie) et ne sont plus des « procaryotes » et donc plus des archées. Ce clade élargi est dénommé Eukaryomorpha. Cette approche signe la fin du modèle à trois domaines, les Archées devenant un groupe paraphylétique à la base des Eukaryota.

Les archées d'Asgård sont généralement thermophiles avec les variations suivantes[1] :

Les Asgards codent certaines protéines semblables à celles des eucaryotes[2], les profilines[3] qui régulent la polymérisation de l'actine, un constituant du cytosquelette des cellules. Elle intervient aussi dans les déplacements de vésicules ou d'organites et dans l'endocytose ou la phagocytose. Ainsi l'ancêtre commun à la bifurcation archées - eucaryotes était dotée de mécanismes qui ont permis l'endocytose fondatrice des eucaryotes[4].

Une étude[5] montre que ces archées sont hétérotrophes : ils se nourriraient de matière organique et rejetteraient à des degrés divers de l'hydrogène ou autres produits de réduction. De leur côté, certaines α-protéobactérie produisent des enzymes spécialisées dans le métabolisme de l'hydrogène. L'étude suggère donc que ces archées et l’ancêtre des mitochondries vivaient en symbiose avant qu'une endosymbiose intervienne et soit pérennisée chez les eucaryotes[6].

Les Asgards n'étaient connus que par des fragments de génomes récoltés dans des sédiments. En 2019, au bout de douze ans d'efforts, une équipe japonaise parvient à en cultiver une espèce, Prometheoarchaeum synthrophicum, accompagnée d'une archée méthanogène du genre Methanogenium (abritée dans ses longs tentacules) et d'une bactérie du genre Halodesulfovibrio (puis les deux espèces d'archées sans la bactérie). De croissance extrêmement lente, Prometheoarchaeum syntrophicum (souche MK-D1) est un organisme de petite taille (∼550 nm), anaérobie, qui dégrade des acides aminés et des peptides par syntrophie avec l'archée Methanogenium et/ou avec la bactérie Halodesulfovibrio[7],[8],[9].

Les Asgards pourraient constituer un sous-règne d'archées formé de cinq embranchements : les Lokiarchaeota, Odinarchaeota, Thorarchaeota, Heimdallarchaeota et Helarchaeota[10], plus (via l'endosymbiose d'une α─protéobactérie) les Eukaryota.

En 2021, l'analyse comparative de 162 génomes d'Asgards élargit considérablement la diversité phylogénétique de ce super-embranchement et conduit à proposer six embranchements supplémentaires dont un clade ancestral provisoirement dénommé Wukongarchaeota. De nouvelles protéines proches de protéines considérées comme caractéristiques des eucaryotes sont aussi découvertes dans plusieurs embranchements, suggérant une évolution dynamique par transfert horizontal, perte et duplication de gènes, voire brassages entre domaines. En revanche cette étude ne permet pas de trancher entre les deux positionnements possibles du dernier ancêtre commun des eucaryotes, un clade frère du clade Heimdallarchaeota–Wukongarchaeota au sein des Asgards, ou bien un clade frère des Asgards au sein des archées[11].

Une thèse identifie de nouveaux embranchements : Idunnarchaeota[12], Freyarchaeota[13], Baldrarchaeota[14], Friggarchaeota et Gefionarchaeota, à partir de 69 génomes issus d'assemblages métagénomiques[1],. Selon les résultats — encore préliminaires — de cette étude, les Idunnarchaeota seraient les archées les plus proches des Eucaryotes. Le dernier ancêtre archéal commun des Eucaryotes (DAACE) trouverait son origine dans ou à la base du clade Idunnarchaeota + Heimdallarchaeota qui serait, dans cette deuxième hypothèse, le groupe frère des Eukaryota. L'étude suggère que ce DAACE ne possédait pas de voie de Wood-Ljungdahl et codait des protéines d'origine bactérienne ce qui témoignerait de transferts horizontaux de gènes entre Bactéries et Archées.

Proteoarchaeota TACKLes archées d'Asgård (Asgardarchaeota), ou simplement Asgards, forment un super-embranchement d'archées découvert en 2015 dans des sédiments profonds à proximité du château de Loki, une source hydrothermale au large de la Norvège. Ils ont été nommés d'après le domaine des dieux dans la mythologie nordique.

Les Asgards partagent des traits que l'on croyait réservés aux eucaryotes. De ce fait, on considère généralement que le clade qui les inclut inclut aussi les Eukaryota, à ceci près que ces derniers sont issus de l'endosymbiose d'au moins une α-protéobactérie (devenue leur mitochondrie) et ne sont plus des « procaryotes » et donc plus des archées. Ce clade élargi est dénommé Eukaryomorpha. Cette approche signe la fin du modèle à trois domaines, les Archées devenant un groupe paraphylétique à la base des Eukaryota.

Asgard ou Asgardarchaeota[1] é um superfilo proposto que consiste em um grupo de arquéias não cultivadas que inclui Lokiarchaeota, Thorarchaeota, Odinarchaeota, Heimdallarchaeota.[2] O superfilo de Asgard representa os parentes procarióticos mais próximos dos eucariotos.[3][4][5]

Os Asgards eram conhecidos apenas a partir de fragmentos de DNA isolados de sedimentos do fundo do mar e outros ambientes extremos.[6]

No verão de 2010, foram analisados sedimentos de uma amostra de solo gravitacional capturado no vale do rift, na cordilheira Knipovich, no Oceano Ártico, perto do chamado local de ventilação hidrotermal do castelo de Loki. Horizontes específicos de sedimentos previamente mostrados para conter grandes abundâncias de novas linhagens archaeais foram submetidos a análise metagenômica.[7][8]

Em 2019, uma equipe no Japão conseguiu cultivar um micróbio a partir de sedimentos do fundo do mar e sequenciou o genoma da cepa MK-D1 de Prometheoarchaeum syntrophicum, é membro deste superfilo.[9][10]

Vias metabólicas de Asgard archaea, variação por filo.[11]

Vias metabólicas de Asgard archaea, variação por ambiente.[11]

A relação filogenética desse grupo ainda está em discussão. O relacionamento dos membros é aproximadamente o seguinte:[12][13]

Moldura verde: Asgard

Asgard ou Asgardarchaeota é um superfilo proposto que consiste em um grupo de arquéias não cultivadas que inclui Lokiarchaeota, Thorarchaeota, Odinarchaeota, Heimdallarchaeota. O superfilo de Asgard representa os parentes procarióticos mais próximos dos eucariotos.

아스가르드(Asgard) 또는 아스가르드고균(라틴어: Asgardarchaeota)는 진핵생물과 가장 가까운 원핵생물을 대표하는 상문으로, 로키고균문, 토르고균문, 오딘고균문, 헤임달고균문을 포함한다. 진핵생물형류(Eukaryomorpha)라고도 불린다. 2017년에 제안되었다.

다음은 프로테오고균의 계통 분류이다.[1][2][3][4]

프로테오고균 TACK군아이가르고균

게오아르고균

바티아르고균

아스가르드고균로키고균

오딘고균

토르고균

헤임달고균

(+알파프로테오박테리아)