fr

noms dans le fil d’Ariane

There have been some difficulties in finding information on S. oerstedii due to its rarity. In general, it is believed to be very similar to its sister species, S. sciureus (Moynihan, 1976). Also, the taxonomy of the genus is not completely resolved. Some authors divide Saimiri into two species, S. sciureus and S. oerstedii (Parker, 1990) while others see between five species (Nowak, 1999) and only one species which can be divided into two subspecies (Moynihan 1976).

Perception Channels: tactile ; chemical

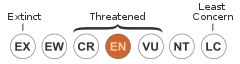

Although its sister species, S. sciureus, is quite abundant the IUCN places S. oerstedii on the endangered list (Nowak, 1999). The population has declined drastically with the destruction of forest habitats (Nowak, 1999). While abundant in the regions it inhabits, S. oerstedii is restricted to a very small area ( Smuts et al., 1987).

CITES: appendix i

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: vulnerable

Squirrel monkeys in general (not specifically S. oerstedii) do benefit humans in that they are very widely used in biomedical research (Strier, 2000). Half of all squirrel monkeys imported to the United States in 1968 were used in labs while the other half were used in zoos and the pet trade (Nowak, 1999). They are often used for aerospace research as well (Rosenblum and Cooper, 1968). In the past, they have also been kept as pets for the European and American aristocracy (Hearn, 1983).

Positive Impacts: pet trade ; research and education

The diet of S. oerstedii consists mostly of invertebrates, small vertebrates, fruit, and flower nectar (Reid 1997). They also recognize the leaf-tents made by some fruit-eating bats and attack these tents to extract the bats (Reid 1997).

In general, members of the genus Saimiri feed primarily on fruit, berries, seeds, gums, leaves, buds, insects, arachnids and small vertebrates (Nowak, 1999). Nearly half of their diet is made up of fruit (Smuts et al., 1987). Most of their prey are immobile invertebrates (Smuts et al., 1987). When the animals find food in a tree, they often do not completely use up the resources available and may return to it in the future (Parker, 1990).

Animal Foods: insects; terrestrial non-insect arthropods

Plant Foods: leaves; seeds, grains, and nuts; fruit; nectar; sap or other plant fluids

Primary Diet: omnivore

Saimiri oerstedii inhabits parts of the Pacific coast of Panama and Costa Rica (Nowak, 1999).

Biogeographic Regions: neotropical (Native )

Little information is available about the habitat of S. oerstedii. In general, squirrel monkeys are arboreal and can be found in primary and secondary forests (Nowak, 1999), thickets, and mangrove swamps (Macdonald, 1984). They are also found in cultivated areas, usually around streams (Nowak, 1999). Saimiri oerstedii is known to inhabit humid Pacific slope forests (Reid, 1997).

Habitat Regions: tropical ; terrestrial

Terrestrial Biomes: forest ; rainforest

Saimiri oerstedii is a small, slender monkey with a long tail (Reid, 1997). Much of their body fur is yellow brown in color with a pale yellow belly (Reid, 1997). Saimiri oerstedii can be distinguished from its sister species Saimiri sciureus because the crown of S. oerstedii is covered with black fur while that of S. sciureus is not (Chiarelli, 1972). Also, S. oerstedii has golden-red colored fur on its back (Rosenblum and Coe, 1985). Saimiri oerstedii weighs between 500 and 1100 g (Reid, 1997). Squirrel monkeys are typically 225 to 295 mm long with tails adding between 370 and 465 mm (Chiarelli, 1972).

Range mass: 500 to 1100 g.

Range length: 225 to 295 mm.

Other Physical Features: endothermic ; homoiothermic; bilateral symmetry

Sexual Dimorphism: sexes alike

The birth rate in the genus Saimiri is about one birth per year (no information specifically for S. oerstedii). Females do not resume cycling until their infant either dies or is weaned (Smuts et al., 1987). The infants are usually born at night (Parker, 1990). Females of S. oerstedii give birth to one young after a gestation period of 7 months (Reid, 1997). The births usually occur during the wet season (Reid, 1997). Although no data were available S. oerstedii, females of its sister species Saimiri sciureus are in a period of estrous around 12 to 36 hours (Hayssen et al., 1993)

Females are sexually mature at about 1 year old, males reach sexual maturity between 4 and 6 years old.

Breeding interval: The birth rate in the genus Saimiri is about one birth per year

Average number of offspring: 1.

Average gestation period: 7 months.

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female): 1 years.

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male): 4-6 years.

Key Reproductive Features: iteroparous ; seasonal breeding ; gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); sexual ; fertilization ; viviparous

Average number of offspring: 1.

In general, a Saimiri mother takes care of the young although sometimes other females help (Parker, 1990). These females are sometimes referred to as "aunts" (Parker, 1990).

For the first few weeks of its life, an infant of genus Saimiri, probably including S. oerstedii, rides along on its mother's back and nurses, with little attention paid to it by the group members (Parker, 1990). During its third and fourth weeks of life, the young monkey begins to move around more and between weeks five and ten, it occasionally disembarks from its mother's back, explores the nearby area, and starts to eat solid foods (Parker, 1990). Over the next couple of months, contacts with the mother become less frequent (Parker, 1990).

In other Saimiri (S. oerstedii is poorly studied), social play first occurs around two months (Parker, 1990). Social play serves to help separate the infant from its mother (Macdonald, 1984). In the first year of life, the young monkeys engage in social play with each other, usually in the form of fighting games (Parker, 1990). Females become adult around month twelve to thirteen while males achieve maturation around their fourth or sixth year (Parker, 1990).

Parental Investment: altricial ; pre-fertilization (Provisioning, Protecting: Female); pre-hatching/birth (Provisioning: Female, Protecting: Female); pre-weaning/fledging (Provisioning: Female, Protecting: Female); pre-independence (Protecting: Female); extended period of juvenile learning

Webpage from Primate Info Net on this genus. Includes info on taxonomy, morphology, ecology, behavior, and conservation.

En el Parque Nacional Corcovado, algunos individuos parece ser que reconocen los refugios hechos en hojas por el "murciélago" (Artibeus watsoni), entonces los revisan desde abajo para asegurarse que haya ocupantes y brincan sobre ellos, la mayoría de los murciélagos huyen, sin embargo, algunos pueden caer, y ahí son capturados y comidos.

En el Parque Manuel Antonio se encontró que S.o. citrinellus se alimenta de 33 especies de plantas (28 especies: frutos y 5 especies: néctar), entre ellas, "cerillo" (Symphonia globulifera), "quieura" (Pseudolmedia spuria), "jobo" (Spondias mombin), "yayo" (Xylopia sericophylla), "espavel" (Anacardium excelsum), "roble de sabana" (Tabebuia rosea), "garrocho" (Quararibea asterolepis), "canfín" (Trichilia propincua), "guayabón" (Eugenia sp.), "guayaba" (Psidium guajaba), "mamón de montaña" (Talisia nervosa), "naranjilla" (Swartzia simplex), "guajiniquil" (Inga multijuga), "guabo grande" (Inga spectabilis), "guayabo de mono" (Posoqueria latisphata), "lengua de vaca" (Miconia argentea), "Santa María" (Miconia schlimii), "guarumo" (Cecropia insignis), "higuerón" (Ficus insípida, F. retusa), "nance" (Byrsonima crassifolia), "mamón" (Meliccoca bijuga), "cafecillo" (Faramea occidentalis), "bejuco" (Clitoria javitensis), "bejuco" (Mendoncia retusa), "capulín" (Muntigia calabura), "platanilla" (Heliconia spp.), "bejuco" (Magfadyena uncata), Guettarda sp., "balsa" (Ochroma lagopus), "banano" (Musa acuminata), "manzana rosa" (Eugenia jambos).

La mona esquirol de dors vermell (Saimiri oerstedii) és una espècie de mico de la família dels cèbids que viu a la costa pacífica de Costa Rica i Panamà.

La mona esquirol de dors vermell (Saimiri oerstedii) és una espècie de mico de la família dels cèbids que viu a la costa pacífica de Costa Rica i Panamà.

Der Mittelamerikanische Totenkopfaffe oder Rotrücken-Totenkopfaffe (Saimiri oerstedii) ist eine Primatenart aus der Gruppe der Neuweltaffen.

Mittelamerikanische Totenkopfaffen sind wie alle Totenkopfaffen relativ kleine, schlanke Primaten. Sie erreichen eine Kopfrumpflänge von 28 bis 33 Zentimetern, der Schwanz wird 33 bis 43 Zentimeter lang. Ihr Gewicht beträgt etwa 0,6 bis 0,9 Kilogramm, wobei die Männchen etwas schwerer werden als die Weibchen. Der Rücken und die Gliedmaßen sind orangerot gefärbt, die Unterseite ist gelblich-weiß. Das Gesicht, die Kehle und die Ohrbüschel sind weiß, der Bereich um den Mund ist dunkel. Die Farbe der Kappe ist variabel: Bei der Unterart Saimiri oerstedii oerstedii ist sie schwarzbraun bei Männchen und schwarz bei Weibchen, bei der Unterart S. o. citrinellus ist sie graugrün bei Männchen und schwarzgrau bei Weibchen.

Mittelamerikanische Totenkopfaffen sind in Mittelamerika beheimatet, ihr Verbreitungsgebiet umfasst die Pazifikküste Costa Ricas und des westlichen Panamas. Ihr Lebensraum sind Wälder, wobei sie in verschiedenen Waldtypen, etwa Regen-, Galerie- und Mangrovenwäldern zu finden sein können.

Diese Primaten sind tagaktiv und halten sich zumeist in den Bäumen, insbesondere in den unteren Regionen, auf. Sie sind schnelle und geschickte Kletterer, die sich meist auf allen vieren fortbewegen.

Sie leben in großen Gruppen aus etwa 40 bis 60 Tieren. Die Gruppen setzen sich aus vielen Männchen und Weibchen und dem gemeinsamen Nachwuchs zusammen. Innerhalb der Gruppe gibt es relativ wenig Aggressionen. Die Weibchen haben relativ wenig Bindung zueinander und etablieren auch keine Rangordnung. Die Rangordnung der Männchen ist nur schwach ausgeprägt, schwächer als bei anderen Totenkopfaffen.

Mittelamerikanische Totenkopfaffen ernähren sich vorwiegend von Insekten und Früchten, deren Anteil je nach Jahreszeit variieren kann. Die Jagd auf Insekten nimmt den größten Teil des Tages in Anspruch.

Die Paarungszeit liegt in den Monaten August bis Oktober, die Männchen nehmen in dieser Zeit bis zu 20 % an Gewicht zu und können so offensichtlich ihren Paarungserfolg steigern. Nach einer rund 150-tägigen Tragzeit bringt das Weibchen zwischen Februar und April meist ein einzelnes Jungtier zur Welt. Die Geburten innerhalb einer Gruppe sind synchronisiert und erfolgen innerhalb zweier Wochen. Nach rund vier Monaten sind die Jungen selbstständig, Weibchen werden mit 2,5 und Männchen mit 3,5 Jahren geschlechtsreif. Während die Männchen in ihrer Geburtsgruppe verbleiben, müssen die Weibchen diese verlassen – eine unter Primaten seltene Anordnung, weitaus häufiger ist es umgekehrt.

Hauptbedrohungen für die Mittelamerikanischen Totenkopfaffen stellt die Zerstörung ihres Lebensraums durch Waldrodungen dar. Dadurch ist ihr Verbreitungsgebiet stark verkleinert und zerstückelt worden. Die IUCN listet die Art als „gefährdet“ (vulnerable). Kritisch ist die Situation der Unterart S. o. citrinellus, deren Verbreitungsgebiet in Costa Rica stark fragmentiert ist, und deren Gesamtpopulation auf höchstens 1300 bis 1800 Tiere geschätzt wird.

Der Mittelamerikanische Totenkopfaffe oder Rotrücken-Totenkopfaffe (Saimiri oerstedii) ist eine Primatenart aus der Gruppe der Neuweltaffen.

The Central American squirrel monkey (Saimiri oerstedii), also known as the red-backed squirrel monkey, is a squirrel monkey species from the Pacific coast of Costa Rica and Panama. It is restricted to the northwestern tip of Panama near the border with Costa Rica, and the central and southern Pacific coast of Costa Rica, primarily in Manuel Antonio and Corcovado National Parks.

It is a small monkey with an orange back and a distinctive white and black facial mask. It has an omnivorous diet, eating fruits, other plant materials, invertebrates and some small vertebrates. In turn, it has a number of predators, including raptors, cats and snakes. It lives in large groups that typically contain between 20 and 75 monkeys. It has one of the most egalitarian social structures of all monkeys. Females do not form dominance hierarchies, and males do so only at breeding season. Females become sexually mature at 2+1⁄2 years, and males at 4 to 5 years. Sexually mature females leave the natal group, but males can remain with their natal group their entire life. The Central American squirrel monkey can live for more than 15 years.

The Central American squirrel monkey population declined precipitously after the 1970s. This decline is believed to be caused by deforestation, hunting, and capture to be kept as pets. Efforts are underway to preserve the species.

The Central American squirrel monkey is a member of the family Cebidae, the family of New World monkeys containing squirrel monkeys, capuchin monkeys, tamarins and marmosets. Within the family Cebidae, it is a member of the subfamily Saimiriinae, the subfamily containing squirrel monkeys.[5] It is one of five recognized species of squirrel monkey, and the only species occurring outside South America.[6] The Central American Squirrel Monkey is placed in genus Saimiri (Voigt, 1831) along with all the other squirrel monkey species. Among the squirrel monkeys, the Central American squirrel monkey is most closely related to the Guianan squirrel monkey (Saimiri sciureus) and the bare-eared squirrel monkey (Saimiri ustus) and these three species form the S. sciureus species group.[7][8] The binomial name Saimiri oerstedii was given by Johannes Theodor Reinhardt in honor of his fellow Danish biologist Anders Sandøe Ørsted.

There are two subspecies of the Central American squirrel monkey:[1]

S. o. oerstedii lives in the western Pacific portion of Panama and the Osa Peninsula area of Costa Rica (including Corcovado National Park), while S. o. citrinellus lives in the Central Pacific portion of Costa Rica. The largest estimate (most recently in 2003) is that the remaining wild population of S. o. citrinellus is only 1,300 to 1,800 individuals.[2]

The Central American squirrel monkey differs in coloration from South American squirrel monkeys. While South American squirrel monkeys tend to be primarily greenish in color, the Central American species has an orange back with olive shoulders, hips and tail, and white undersides. The hands and feet are also orange. There is a black cap at the top of the head, and a black tip at the end of the tail. Males generally have lighter caps than females. The face is white with black rims around the eyes and black around the nose and mouth.[9][10]

The two subspecies are similar in coloration, but differ in the shade of the cap. The northern subspecies, living in Central Pacific Costa Rica, has a lighter cap than the southern subspecies, which lives in Panama and in parts of Costa Rica near Panama.[10] The southern subspecies also has more yellowish limbs and underparts.[4]

Adults reach a length of between 266 and 291 millimetres (10+1⁄2 and 11+1⁄2 inches), excluding tail, and a weight between 600 and 950 grams (21 and 34 ounces).[6][10] The tail is longer than the body, and between 362 and 389 mm (14+1⁄4 and 15+3⁄8 in) in length.[10] As with other squirrel monkeys, there is considerable sexual dimorphism. On average, males weigh 16% more than females.[6] Males have an average body weight of 829 g (29+1⁄4 oz) and females average 695 g (24+1⁄2 oz).[6] Squirrel monkeys have the largest brains of all primates relative to their body size; the Central American squirrel monkey's brain weighs about 25.7 g (29⁄32 oz), or about 4% of its body weight.[9][11] Unlike larger relatives, such as the capuchin, spider and howler monkeys, Central American squirrel monkeys do not have a fully prehensile tail, except as newborn infants, and the tail is primarily used to help with balance.[12][13]

The Central American squirrel monkey is arboreal and diurnal, and most often moves through the trees on four legs (quadrupedal locomotion).[9] It lives in groups containing several adult males, adult females, and juveniles. The group size tends to be smaller than that of South American squirrel monkeys, but is still larger than for many other New World monkey species. The group generally numbers between 20 and 75 monkeys, with a mean of 41 monkeys.[6][14] Groups in excess of 100 sometimes occur, but these are believed to be temporary mergers of two groups.[2] On average, groups contain about 60% more females than males.[6]

The squirrel monkey groups have a home range of between 35 and 63 hectares (86 and 156 acres).[14] Group ranges can overlap, especially in large, protected areas such as Manuel Antonio National Park. Less overlap occurs in more fragmented areas.[14] Groups can travel between 2,500 and 4,200 m (8,200 and 13,800 ft) per day.[15] Unlike some other monkey species, the group does not split into separate foraging groups during the day. Individual monkeys may separate for the main group to engage in different activities for periods of time, and thus the group may be dispersed over an area of up to 1.2 hectares (3 acres) at any given time.[16] The group tends to sleep in the same trees every night for months at a time, unlike other squirrel monkeys.[16]

There are no dominance hierarchies among the females, and the females do not form coalitions.[2][6] Males in the group are generally related to each other and thus tend to form strong affiliations, and only form dominance hierarchies during the breeding season.[6] This is especially the case among males of the same age.[14] Neither males nor females are dominant over each other, an egalitarian social system that is unique to Central American squirrel monkeys. In South American species, either the females (S. boliviensis) or males (S. sciureus) are dominant over the other sex, and both sexes form stable dominance hierarchies.[6] Groups of Central American squirrel monkeys generally do not compete or fight with each other.[2] Male Costa Rican squirrel monkeys are known to have very close bonds with each other.[17]

Although South American species of squirrel monkeys often travel with and feed together with capuchin monkeys, the Central American squirrel monkey only rarely associates with the white-headed capuchin. This appears to be related to the fact that the food the Central American squirrel monkey eats is distributed in smaller, more dispersed patches than that of South American squirrel monkeys. As a result of the different food distribution, associating with capuchin monkeys would impose higher foraging costs for the Central American squirrel monkey than for their South American counterparts. In addition, while male white-headed capuchins are alert to predators, they devote more attention to detecting rival males than to detecting predators, and relatively less time to detecting predators than their South American counterparts. Therefore, associating with capuchins would provide less predator detection benefits and impose higher foraging costs on the Central American squirrel monkey than on South American squirrel monkeys.[6][13][18][19] An alternative explanation is that capuchin groups are larger than squirrel monkey groups in Central America, but in South America the squirrel monkey groups are larger.[20]

In one study a slight tendency was observed in which Central American squirrel monkeys were more likely to travel near mantled howler monkeys if the howlers were vocalizing loudly within their home range, but no physical contact or obvious social interaction was observed.[20] Variegated and red-tailed squirrels may join Central American monkey groups without eliciting a reaction from the monkeys.[20]

Certain bird species associate with the Central American squirrel monkey. The birds follow the monkeys in an attempt to prey on insects and small vertebrates that the monkeys flush out. At Corcovado National Park, bird species known to regularly follow squirrel monkeys include the double-toothed kite, the grey-headed tanager and the tawny-winged woodcreeper, but other woodcreepers and such species as motmots and trogons do so as well. This activity increases during the wet season, when arthropods are harder to find.[14]

The Central American squirrel monkey is omnivorous. Its diet includes insects and insect larvae (especially grasshoppers and caterpillars), spiders, fruit, leaves, bark, flowers, and nectar. It also eats small vertebrates, including bats, birds, lizards, and tree frogs. It finds its food foraging through the lower and middle levels of the forest, typically between 4.5 and 9 metres (15 and 30 feet) high.[14][16] Two-thirds to three-quarters of each day is spent foraging for food. It has difficulty finding its desired food late in the wet season, when fewer arthropods are available.[10]

It has a unique method of capturing tent-making bats. It looks for roosting bats by looking for their tents (which are made of a folded leaf). When it finds a bat it climbs to a higher level and jumps onto the tent from above, attempting to dislodge the bat. If the fallen bat does not fly away in time, the monkey pounces on it on the ground and eats it.[14]

The Central American squirrel monkey is an important seed disperser and a pollinator of certain flowers, including the passion flower.[14] While it is not a significant agricultural pest, it does sometimes eat corn, coffee, bananas and mangos.[14] Other fruits eaten include cecropias, legumes, figs, palms, cerillo, quiubra, yayo flaco and wild cashew fruits.[14][16]

The Central American squirrel monkey is noisy. It makes many squeals, whistles and chirps.[10] It also travels through the forest noisily, disturbing vegetation as it moves through.[10] It has four main calls, which have been described as a "smooth chuck", a "bent mask chuck", a "peep" and a "twitter".[9]

Predators of the Central American squirrel monkey include birds of prey, cats and snakes. Constricting and venomous snakes both prey on squirrel monkeys. Raptors are particularly effective predators of Central American squirrel monkeys.[6] The oldest males bear most of the responsibility for detecting predators.[2][14] When a Central American squirrel monkey detects a raptor, it gives a high-pitched alarm peep and dives for cover. All other squirrel monkeys that hear the alarm call also dive for cover. The monkeys are particularly cautious about raptors, and give alarms when they detect any raptor-like object, including small airplanes and even falling branches and large leaves.[16]

Predator detection by males becomes particularly important during the period when the infants are born. Raptors spend significantly more time near the squirrel monkey troops during this period, and prey on a significant number of newborn infants. Other animals that prey on Central American squirrel monkey infants include toucans, tayras, opossums, coatis, snakes, and even spider monkeys.[16]

The breeding season for the Central American squirrel monkey is in September.[14] All females come into estrus at virtually the same time. A month or two before the breeding season begins, males become larger. This is not due to extra muscle, but to altered water balance within the male's body. This is caused by the conversion of the male hormone testosterone into estrogen; thus the more testosterone a male produces, the more he grows in advance of the breeding season. Since males within a group have not been observed fighting over access to females during the breeding season, nor attempting to force females to copulate with them, it is believed that female choice determines which males get to breed with females. Females tend to prefer the males that expand the most in advance of breeding season. This may be because the most enlarged males are generally the oldest and the most effective at detecting predators, or it may be a case of runaway intersexual selection.[16]

Males sometimes leave their group for short periods of time during the breeding season in order to try to mate with females from neighboring groups. Females are receptive to males from other groups, although resident males attempt to repel the intruders. The gestation period is six months, and the infants are born within a single week during February and March. Typically, a single infant is born.[6][14][16]

Only 50% of infants survive more than six months, largely due to predation by birds.[6] The infant remains dependent on its mother for about one year.[14] Females give birth every 12 months, so the prior infant becomes independent at about the same time the new infant is born. Females become sexually mature at 2+1⁄2 years old, while males become sexually mature at between 4 and 5 years old.[6] The females leave their natal group upon reaching sexual maturity, while males usually remain with their group for their entire lives. This is different from South American squirrel monkey species, where either males disperse from their natal group or both sexes disperse.[6] Males of the same age tend to associate with each other in age cohorts. Upon reaching sexual maturity, an age cohort may choose to leave the group and attempt to oust the males from another group in order to attain increased reproductive opportunities.[6]

The lifespan of the Central American squirrel monkey in the wild is unknown, but captive specimens have been known to live more than 15 years.[14] Other squirrel monkey species are known to be able to live more than 20 years.[6]

The Central American squirrel monkey has a restricted distribution in Costa Rica and Panama. It lives only near the Pacific coast. Its range covers Central Pacific Costa Rica in the north through western Panama.[10] It lives in two of Costa Rica's national parks—Manuel Antonio National Park and Corcovado National Park—where it can be seen by visitors, but it is not as commonly seen in these parks as the white-headed capuchin or the mantled howler monkeys.[21] It lives in lowland forests and is restricted to secondary forests and primary forests which have been partially logged.[14] It requires forests with abundant low and mid-level vegetation and has difficulty surviving in tall, mature, undisturbed forests that lack such vegetation.[10][14] Its specialization for coastal lowland forest may explain its restricted distribution.[8]

It was once believed that the Central American squirrel monkey was just a population of a South American species of squirrel monkey brought to Central America by humans. Evidence for this theory included the very small range of the Central American squirrel monkey and the large gap from the range of any other squirrel monkey species. A study of nuclear and mitochondrial DNA demonstrated that the Central American squirrel monkey is indeed a separate species that apparently diverged from the South American species long ago – at least 260,000 years ago and possibly more than 4 million years ago.[4] A genetic study by Lynch Alfaro, et al. in 2015 estimated that the Central American squirrel monkey diverged from S. scuireus a little less than 1 million years ago.[8]

One popular theory is that squirrel monkeys did live in Colombia during the late Miocene or Pliocene and these squirrel monkeys migrated to Central America, becoming the ancestors of the current Central American species. According to this theory, the Guatemalan black howler migrated to Central America around the same time. Passage through the isthmus of Panama later closed due to rising oceans, and eventually opened up to another wave of migration about 2 million years ago. These later migrants, ancestors to modern populations of white-headed capuchins, mantled howlers and Geoffroy's spider monkeys, out-competed the earlier migrants, leading to the small range of the Central American squirrel monkey and Guatemalan black howler.[22] Ford suggested that high water levels during the Pleistocene not only cut off the Central American squirrel monkey from other squirrel monkeys, but was also responsible for the formation of two subspecies.[8][22] Lynch Alfaro, et al. suggested that the separation of the Central American squirrel monkey from other squirrel monkeys may have resulted from a period of high aridity in northern South America.[8]

The population density has been estimated at 36 monkeys per square kilometer (93 per square mile) in Costa Rica and 130 monkeys per square kilometer (337 per square mile) in Panama.[15] It has been estimated that the population of the Central American squirrel monkey has been reduced from about 200,000 in the 1970s to less than 5,000.[21] This is believed to be largely due to deforestation, hunting, and capture for the pet trade.[21] There are significant efforts within Costa Rica to try to preserve this monkey from extinction.[23] A reforestation project within Panama tries to preserve the vanishing population of the Chiriqui Province.[24]

As of 2021, the Central American squirrel monkey is listed as endangered from a conservation standpoint by the IUCN.[2] This is due mainly to deforestation ongoing habitat loss, but other sources such as capture for the pet trade also contribute.[2]

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ignored ISBN errors (link) The Central American squirrel monkey (Saimiri oerstedii), also known as the red-backed squirrel monkey, is a squirrel monkey species from the Pacific coast of Costa Rica and Panama. It is restricted to the northwestern tip of Panama near the border with Costa Rica, and the central and southern Pacific coast of Costa Rica, primarily in Manuel Antonio and Corcovado National Parks.

It is a small monkey with an orange back and a distinctive white and black facial mask. It has an omnivorous diet, eating fruits, other plant materials, invertebrates and some small vertebrates. In turn, it has a number of predators, including raptors, cats and snakes. It lives in large groups that typically contain between 20 and 75 monkeys. It has one of the most egalitarian social structures of all monkeys. Females do not form dominance hierarchies, and males do so only at breeding season. Females become sexually mature at 2+1⁄2 years, and males at 4 to 5 years. Sexually mature females leave the natal group, but males can remain with their natal group their entire life. The Central American squirrel monkey can live for more than 15 years.

The Central American squirrel monkey population declined precipitously after the 1970s. This decline is believed to be caused by deforestation, hunting, and capture to be kept as pets. Efforts are underway to preserve the species.

El mono ardilla de América Central (Saimiri oerstedii) es un primate de la familia Cebidae. También se llama el mono de espalda roja por su cabello rojo dorado en la espalda. Son los miembros en mayor peligro de extinción de las otras familias de monos ardillas

Con dos subespecies llamadas Saimiri oerstedii oersted y Saimiri oerstedii citrinellus que viven en dos poblaciones geográficamente separadas en las costas del Pacífico de Colombia,Costa Rica y Panamá,[1] por debajo de los 500 msnm. Prefiere el bosque secundario.[2]

La longitud del cuerpo con la cabeza alcanza entre 26 y 33 cm, la cola entre 36 y 39 cm. Pesa entre 0,5 y 1,1 kg. La hembra es más pequeña que el macho. La cara tiene una máscara blanca, las orejas y el pecho son blancuzcos, en contrastante con el hocico, ojos y la corona, que son de color negro; los hombros son de color pardo a gris amarillento, la espalda es de color castaño rojizo a anaranjado y las patas de color gris, con las manos y patas anaranjadas; el vientre es blanquecino a color crema; mientras los flancos y la cola son de color amarillento; los muslos y la base de la cola son de color marrón amarillento a pardo olváceo y la punta de la cola es negruzca.[2]

Se trata de animales diurnos y arbóreos viven en grupos de 12 a 66 individuos,[2] que se desplazan en una zona de 0,2 km cuadrados en 5 km en un día. Por esta razón son diferentes que los otros monos ardillas porque viven en grupos más pequeños. Usualmente las otras familias de monos ardillas viven en grupos de casi 300 miembros en comparación. En las familias de monos ardillas de América Central, las madres cuidan a sus niños y a veces ayudan con los niños de otras madres del grupo.

A causa del hábitat de otras especies y la constante distancia entre otras especies de monos ardilla han sido dos teorías, según la primera, los hombres los introdujeron en tiempos prehistóricos y posteriormente evolucionaron por su cuenta.[2] Un estudio genético de 2000 rechazó esta hipótesis.[3]

La más acreditada teoría es que los antepasados de estos animales vivían en la actual Colombia entre el Mioceno y el Plioceno y desde allí se trasladaron a Centroamérica por el istmo de Panamá junto con otras especies. La dispersión pudo haber sido promivida por fluctuaciones climáticas.[2]

La dieta es basada en insectos, arañas y pequeños vertebrados, pero también consume frutos, flores y néctar.[2]

Debido a la extrema rareza de este animal no se sabe mucho de su reproducción; se cree que nace de una sola cría y su gestación de 7 meses. Los apareamientos ocurren en enero y los nacimientos en agosto; la crianza se extiende hasta octubre.[2]

El mono ardilla de América Central (Saimiri oerstedii) es un primate de la familia Cebidae. También se llama el mono de espalda roja por su cabello rojo dorado en la espalda. Son los miembros en mayor peligro de extinción de las otras familias de monos ardillas

Saimiri oerstedii Saimiri generoko animalia da. Primateen barruko Saimiriinae azpifamilia eta Cebidae familian sailkatuta dago

Saimiri oerstedii Saimiri generoko animalia da. Primateen barruko Saimiriinae azpifamilia eta Cebidae familian sailkatuta dago

Panamansaimiri (Saimiri oerstedii) on vaarantunut apinalaji. Sitä esiintyy Costa Ricassa ja Panamassa. 1970-luvulla panamansaimireita oli 200 000, mutta nykyään niitä elää vain 5 000 yksilöä. Kanta on harventunut hakkuiden, metsästyksen ja lemmikkikaupan myötä.

Panamansaimiri on noin 30 cm pitkä ja painaa kilon tai vähän alle.

Panamansaimiria tavataan Costa Ricassa ja Panamassa. Panamassa sitä tavataan Tyynenmeren puoleisella rannikolla pohjoisessa kärjessä lähellä Costa Rican rajaa. Costa Ricassa sitä tavataan Tyynenmeren puoleisella rannikolla Costa Rican etelä- ja keskiosassa.

Panamansaimirit ovat aktiivisia päiväsaikaan. Ne kiipeilevät puissa, mutta toisin kuin muut pienet apinat, ne eivät käytä häntäänsä kiipeilyn apuvälineenä. Ne elävät suurissa, jopa satojen yksilöiden laumoissa joissa on molemia sukupuolia.

Panamansaimirit ovat kaikkiruokaisia. Ne syövät pääasiassa hedelmiä ja hyönteisiä, lisäravintona myös pähkinöitä, versoja, munia ja pieniä selkärankaisia.

Panamansaimiri (Saimiri oerstedii) on vaarantunut apinalaji. Sitä esiintyy Costa Ricassa ja Panamassa. 1970-luvulla panamansaimireita oli 200 000, mutta nykyään niitä elää vain 5 000 yksilöä. Kanta on harventunut hakkuiden, metsästyksen ja lemmikkikaupan myötä.

Sapajou à dos rouge, Saïmiri à dos roux, Saïmiri d'Amérique centrale

Saimiri oerstedii est une espèce de primates de la famille des Cebidae, appelé Sapajou à dos rouge[1], Singe-écureuil à dos rouge[1], Saïmiri à dos roux[2] ou encore Saïmiri d'Amérique centrale[3].

le Saïmiri d'Amérique centrale est présent sur la côte pacifique du Costa Rica et du Panamá, dans une aire géographique historique extrêmement restreinte (8 000 km2). Le delta des Ríos Sierpe-Terraba constitue la limite entre les deux sous-espèces. Certains pensent que cette espèce a été introduite par l’homme dans cette région du monde car elle est séparée par plus de 600 km de la plus proche espèce de saïmiri sud-américain. Cette introduction récente, antérieure à la colonisation hispanique, serait le fait d’Amérindien du Pérou ou de l’Équateur ayant amené avec eux des saïmiris de l'Équateur (S. sciureus macrodon). D’autres scientifiques, sur la base de travaux génétiques et morphologiques, pensent, au contraire, que cette dispersion a eu lieu de façon naturelle au gré des fluctuations climatiques du pléistocène, il y a au moins 500 000 ans.

Deux sous-espèces sont reconnues :

Saïmiri à dos roux (S. o. oerstedii), Saïmiri du Costa Rica (S. o. citrinellus). Central american squirrel monkey. Red-backed american squirrel monkey (S. o. oerstedii), black-crowned american squirrel monkey (S. o. citrinellus). Mono ardilla, tití, barizo dorsirojo (Costa Rica). S’écrirait oerstedti d’après Groves.

Forêt secondaire intermédiaire et mature. Plus rarement forêt primaire et mangrove. Zones cultivées, comme les plantations de goyaviers.

Souvent en compagnie du Capucin à face blanche (Cebus (Cebus) capucinus). Il est suivi par de nombreuses espèces d’oiseaux qui profitent des proies dérangées par ce singe, notamment le Tangara à tête grise (Eucometis penicillata), le Grimpar à ailes rousses (Dendrocincla anabatina), le Milan bidenté (Harpagus bidentatus) mais aussi le Grimpar barré (Dendrocolaptes certhia), le Motmot houtouc (Momotus momota), le Tamatia de Lafresnaye (Malacoptila panamensis), le Trogon aurore (Trogon rufus), la Buse blanche (Leucopternis albicollis), la Buse semiplombée (Leucopternis semiplumbea), la Buse à gros bec (Buteo magnirostris) et le Faucon des chauves-souris (Falco rufigularis).

Dos doré orangé. Dessous orange pâle. Membres orangés chez S. o. oerstedii, bras orangés et jambes chamois ou gris agouti chez S. o. citrinellus. Pieds et mains doré orangé. Queue olivacée puis noire. Gorge, côté du cou et menton blancs. Oreilles touffues. Tache préauriculaire noirâtre chez S. o. oerstedii, chamois ou gris agouti chez S. o. citrinellus. Couronne et joues noirâtres chez les deux sexes pour S. o. oerstedii, noirâtres chez la femelle et gris agouti chez le mâle pour S. o. citrinellus. L’arche au-dessus des yeux est de type Gothique (en pointe) comme chez le Saïmiri commun.

Mâle : Corps 31 cm. Queue de 36 à 40 cm. Poids de 0,55 à 1,135 kg. Femelle : Corps 28,5 cm. Queue 36 à 40 cm. Poids de 0,365 à 0,75 kg. Cerveau : 25,7 g. Les canines sont plus longues chez le mâle (3,9 mm) que chez la femelle (2,7 mm). Caryotype : 2n = 44.

Vit aujourd’hui sur des domaines peu étendus. Un groupe de 23 membres étudié au Panamá occupait un domaine alimentaire de 17 ha, avec une aire exclusive de 1,8 ha. Un autre groupe de 27 individus évoluait dans les marais côtiers sur un domaine de 20 à 40 ha. Dans le PN de Manuel Antonio et alentour, le domaine s’étend sur 35 à 63 ha (voire seulement 27 ha) avec un chevauchement nul ou parfois de 25 à 50 %. Plus souvent, on ne rencontre plus que de petits groupes non viables d’une dizaine d’éléments survivant dans des bois isolés de 1 à 2 ha. Dans les zones non dégradées, le territoire annuel de l’espèce pourrait dépasser 2 km2.

Au maximum 130/km². 86/km² (péninsule d’Osa). 31/km² ou 66/km² (PN de Manuel Antonio).

Quadrupède. Sauteur. Ses bonds horizontaux dépassent rarement les 2 m de long.

Diurne. Arboricole.

Se montre le plus actif le matin et en fin d’après-midi, se déplaçant tantôt avec bruit tantôt dans le plus grand silence, seule la chute des feuilles témoignant alors de son passage. Il voyage et se nourrit exclusivement sur les petites branches de 1 à 2 cm de diamètre, dans la strate moyenne essentiellement. Il doit se déplacer plus vite et se reposer moins longtemps lorsque la nourriture se fait rare. Les femelles adultes influencent largement le choix des trajets empruntés. Il parcourt chaque jour 2,6 à 3,3 km. À la tombée du jour, tous les membres grimpent à la cime d’un émergeant pour s’y endormir pelotonnés, cet arbre géant servant plusieurs nuits de suite.

Frugivore-insectivore. Consomme des végétaux (baies, noix, fleurs, bourgeons, feuilles, graines, gomme, nectar - des héliconias, notamment), des invertébrés (insectes tels que mouches, chenilles et papillons, araignées, escargots, limaces, crabes terrestres) à hauteur de 20 % de son régime, des petits vertébrés (lézards, rainettes, chiroptères) et visite parfois les plantations (bananes, fruits des palmiers à huile, jamboses, fruits de la passion, fruits des ingás). Les grosses chenilles sont débarrassées de leurs poils urticants, de la tête et des organes internes avant d’être consommées. Les membres entrent en compétition pour les insectes mais pas pour les fruits. S’attaque aux chauves-souris à tente communes (Uroderma bilobatum) et aux artibées glauques (Artibeus glaucus watsoni) : les premières se cachent sous de larges feuilles de bananiers qu’elles ont mordues pour les faire plier et former abri, les secondes sous les feuilles non moins larges de l’anthurium Anthurium ravenii. Celles qui ne réussissent pas à s’extirper de leur torpeur assez rapidement ou qui tombent au sol finissent sous les crocs des singes.

Dans le PN de Manuel Antonio, le Saïmiri d’Amérique centrale à couronne grise (S. o. citrinellus) consomme 33 espèces de plantes dont 28 pour leurs fruits et 5 pour leur nectar. Ces plantes sont : l’omniprésent manglier blanc cerillo (Symphonia globulifera), le mombin jaune (Spondias mombin), le cajou (Anacardium excelsum), le bananier (Musa acuminata), le goyavier (Psidium guajaba), le « chêne » de la savane (Tabebuia rosea) aux belles fleurs roses, le sapotier garrocho (Quararibea asterolepis), le balsa (Ochroma lagopus), le « ramboutan » de montagne (Talisia nervosa), le jambosier (Eugenia jambos), les eugénias guayabón (Eugenia sp.), les heliconias (Heliconia spp.), les ingás (Inga multijuga et Inga spectabilis), le « goyavier du singe » (Posoqueria latifolia), la « langue de vache » (Miconia argentea), la Santa María (Miconia schlimii), le bois-trompette (Cecropia insignis), les figuiers (Ficus insipida et Ficus retusa), le quieura (Pseudolmedia spuria) dont les fruits rouges à maturité sont extrêmement convoités par les singes et les oiseaux, le canfín (Trichilia propincua), le naranjillo (Swartzia simplex), le nance (Byrsonima crassifolia), le mamoncillo (Meliccoca bijuga), le cafecillo (Faramea occidentalis), le bejuco (Magfadyena unguis-cati, Clitoria javitensis et Mendoncia retusa), le capulín (Muntigia calabura), le yayo (Xylopia sericophylla) et Guettarda sp.

Important pollinisateur de la grenadille Passiflora adenopoda appelée localement comida de culebra.

De 40 à 70 (10 à 35 le plus souvent). 32 (de 15 à 80), moyenne sur 45 fragments forestiers. Jamais aussi nombreux que les rassemblements amazoniens.

Groupe multimâle-multifemelle. Polygamie. Sex-ratio : 3. Dans les groupes de citrinellus, on a compté en moyenne 35 % de femelles adultes, 12 % de mâles adultes, 25 % de jeunes et 27 % d’enfants.

Évolue dans un contexte non agressif et égalitaire.

La femelle émigre vers 2 ans. Les mâles restent le plus souvent dans leur clan natal (philopatrie), formant ainsi des patrilignées dont le but est de régner sur un bon territoire accueillant et protégeant de nombreuses femelles évoluant de façon autonomes (elles ne coopèrent pas les unes avec les autres).

Les mâles examinent ensemble les femelles lorsqu’elles sont en chaleur, sans exclusive. Le mâle ayant le plus grossi avant la période des amours monopolise une grande partie des accouplements. Mais comme tous les mâles sont apparentés, le grand succès reproductif du mâle alpha contribue à la perpétuation des gènes des subordonnés. Ce système patrilinéaire atténue les pressions de la sélection sexuelle qui conduisent au dimorphisme sexuel chez d’autres espèces, si bien que les mâles sont à peine plus grands que les femelles. Les singes diminuent leurs trajets quotidiens dès que les femelles ont mis bas. Diverses stratégies sont mises au point pour répondre à un taux élevé de prédation. D’une part, le synchronisme des naissances, étalées sur seulement une semaine (!). D’autre part, la femelle met bas chaque année (contre une fois tous les deux ans chez le Saïmiri commun). Enfin, le jeune est sevré vers l’âge de 6 mois, bien plus tôt que le jeune Saïmiri commun. Gestation de 152 à 172 jours. Un seul petit naît, entre février et avril, à la saison d’abondance.

Indépendance à 1 an. Maturité sexuelle : 3 ans (F) et 5 ans (M).

Quatre types principaux de vocalisation. Un appel court et doux (smooth chuck des Anglo-Saxons), une variante du précédent émise tête penchée (bent mask chuck), un piaulement et un gazouillis d’oiseau. 60 % des vocalisations produites sont l’un des quatre sous-types de smooth chuck.

Jaguar, eyra, coati, Sarigue à oreilles noires (Didelphis marsupialis), Capucin à face blanche (Cebus capucinus). Rapaces, tels le Carnifex à collier (Micrastur semitorquatus) et la Harpie huppée (Morphnus guianensis). Serpents, tels le Boa constricteur (Boa constrictor emperator) et le fer-de-lance (Bothrops asper).

Parmi les primates néotropicaux les plus menacés. Déforestation : débitage du bois, agriculture, pollution (pesticides), destruction des mangroves pour le tourisme. Les biologistes s’inquiètent du stress provoqué par les touristes indisciplinés qui jettent des pierres et des branches pour forcer ce singe timide à se montrer. Les électrocutions sur les lignes électriques ne sont pas rares. Diverses épidémies et la fièvre jaune ont aussi contribué à la diminution du stock. Enfin, les conditions climatiques jouent leur rôle. Ainsi, en août 1993, l’ouragan Gert a dévasté le quart de la forêt du PN de Manuel Antonio. L’ouragan Caesar en juillet 1996 a également causé beaucoup de dégâts. Toutefois, ces catastrophes naturelles n’ont pas que des inconvénients : en détruisant la forêt mature, elles permettent la repousse d’une végétation favorable à ces petits singes. En effet, les habitats dégradés en régénérescence profitent bien à l’espèce dans la mesure où les insectes (notamment les sauterelles), sa nourriture préférée, y abondent. A contrario, la déforestation implique une fragmentation (routes, etc.) hautement préjudiciable à cette espèce arboricole qui a besoin d’un couvert végétal continu.

~ 2000 (S. o. citrinellus). ~ 4000 (S. o. oerstedii).

Saïmiri d’Amérique centrale à couronne noire (S. o. oerstedii) : PN de Corcovado et PN de Golfito (Costa Rica). PN du Golfe de Chiriquí (Panamá).

Saïmiri d’Amérique centrale à couronne grise (S. o. citrinellus) : PN de Manuel Antonio (Costa Rica).

Le Saïmiri d’Amérique centrale à couronne noire (S. o. oerstedii) ne survit que sur une minuscule partie de son aire originelle qui s’étendait naguère depuis les forêts humides de plaine de la côte pacifique dans la province de Puntarenas (incluant la péninsule d’Osa) jusqu’au Panamá dans les provinces de Chiriquí et Veraguas. Un ou deux groupes survivraient sur le versant panaméen de la péninsule de Burica (forêt d’El Chorogo dans le PN du Golfe de Chiriquí). Côté costaricien, on compte 2000 à 3000 individus dont environ 500 pour le seul PN de Corcovado (418 km2) avec une quinzaine de troupes dispersées dans et aux alentours du parc. Le récent PN de Golfito (28 km2), également à l’extrême sud du pays, pourrait constituer un nouveau refuge (~60 individus).

Le Saïmiri d’Amérique centrale à couronne grise (S. o. citrinellus) est essentiellement restreint aux alentours du PN de Manuel Antonio, un sanctuaire végétal côtier situé à Quepos (120 km au sud de San José). On y recense quelque 580 saïmiris placés sous constante surveillance et jusqu’à 1200 en comptant les spécimens vivant aux alentours. Ailleurs, cette sous-espèce est dispersée sur une cinquantaine de sites dans des fragments de forêt. 500 à 1000 individus survivraient dans les collines basses entre le Cerro Dota (haut Río Parrita) et le Cerro Herradura (juste au nord de San Isidro), ainsi que plus au sud dans les mangroves du delta formé par les fleuves Terraba et Sierpe. Ce sont souvent des micropopulations de moins de 50 individus, non viables à long terme, hormis celle qui vit dans l’interfluve Río Naranjo au nord et Río Savegre-División au sud (ce secteur se trouve juste au sud du parc Manuel Antonio).

À Manuel Antonio, le Jardín Gaia, aujourd’hui restreint à une activité botanique par le gouvernement, fut pendant près d’une décennie un précieux refuge pour les primates abandonnés ou blessés qui recueillait les saïmiris d’Amérique centrale, les capucins à face blanche (Cebus capucinus) et les pinchés à crête blanche (Saguinus oedipus).

En danger.

Saïmiri d’Amérique centrale à couronne grise (S. o. citrinellus) : en danger critique d’extinction.

Saïmiri d’Amérique centrale à couronne noire (S. o. oerstedii) : en danger.

Sapajou à dos rouge, Saïmiri à dos roux, Saïmiri d'Amérique centrale

Saimiri oerstedii est une espèce de primates de la famille des Cebidae, appelé Sapajou à dos rouge, Singe-écureuil à dos rouge, Saïmiri à dos roux ou encore Saïmiri d'Amérique centrale.

Il saimiri del Centro America (Saimiri oerstedii Reinhardt, 1872) è un primate platirrino della famiglia dei Cebidi.

Con due sottospecie (Saimiri oerstedii citrinellus e Saimiri oerstedii oerstedii) vive in due popolazioni geograficamente separate sulla costa pacifica di Costa Rica e Panama.

Misura circa 60 cm di lunghezza, di cui più della metà spettano alla coda, per un peso medio di 800 g.

Mentre le scimmie scoiattolo dell'America Meridionale tendono ad avere come colore primario il verde oliva, questi animali hanno il dorso bruno-rossiccio con le zampe grigie ed il ventre biancastro, anche se i fianchi e la coda sono giallastri. La testa è nera, ma la faccia presenta una mascherina bianca che circonda il muso, anch'esso nero, e si estende anche sulle tempie. La punta della coda è nera.

Si tratta di animali diurni e sociali: vivono in gruppi che, a causa dell'esiguo numero di esemplari rimasti, contano poche unità. I gruppi si muovono all'interno di un territorio che misura circa 0,2 km², percorrendo fino a 5 km al giorno.

A causa dell'habitat piuttosto esiguo della specie e della grande distanza che separa gli areali di questi animali da quelli delle altre specie di scimmie scoiattolo, è stata a lungo caldeggiata l'ipotesi che questi animali siano in realtà discendenti di scimmie scoiattolo importate dall'uomo nella zona in tempi preistorici, ed evolutisi successivamente per conto proprio. Tale ipotesi è stata infine scartata dopo gli esami del DNA mitocondriale delle varie specie di saimiri, dai quali è emerso che questa specie ha intrapreso un proprio cammino evolutivo, separandosi dalle altre quattro, in un periodo compreso fra i 260.000 anni fa ed i sei milioni di anni fa.[1].

La teoria più accreditata è che questi animali vivessero in Columbia fra Miocene e Pliocene, e da qui si spostarono in America Centrale attraverso l'istmo di Panama, assieme ad altre specie come gli antenati della scimmia urlatrice guatemalteca (Alouatta pigra): quando l'istmo venne sommerso dagli oceani in crescita, circa due milioni di anni fa, queste popolazioni rimasero isolate, per poi venire investite da una nuova ondata migratoria quando l'istmo si ricompose, con specie come il cappuccino tasta bianca (Cebus capucinus), la scimmia urlatrice dal mantello (Alouatta palliata) e l'atele di Geoffroy (Ateles geoffroyi), i quali ebbero la meglio nella competizione per il cibo lasciando gli animali evolutisi a partire dalla precedente ondata migratoria confinati in spazi ristretti[2].

Si stima che la popolazione totale di questi animali sia calata negli ultimi trent'anni dalle 200.000 alle meno di 5000 unità.[3], a causa della deforestazione, della caccia per il bushmeat e della cattura per fare di questi animali degli animali domestici[4][5].

La dieta di questi animali è sostanzialmente insettivora: si nutrono di insetti, piccoli invertebrati, ma anche di frutta, fiori e nettare. Sono state osservate alcune popolazioni controllare periodicamente le costruzioni di foglie fatte dai pipistrelli delle foglie per verificare la presenza dei legittimi abitatori ed eventualmente mangiarli. Essendo animali molto intelligenti, tendono a non esaurire del tutto le risorse dell'ambiente in cui vivono, in modo tale da dar loro il tempo di rigenerarsi.

A causa dell'estrema rarità della specie, poco o nulla si conosce sui suoi comportamenti riproduttivi: si pensa che in genere la riproduzione del saimiri centro-americano differisca molto poco da quella delle altre specie congeneri, che partoriscono un unico cucciolo dopo una gravidanza di sette mesi.

Il saimiri del Centro America (Saimiri oerstedii Reinhardt, 1872) è un primate platirrino della famiglia dei Cebidi.

Het geel doodshoofdaapje (Saimiri oerstedii) is een kleine soort aap, die leeft in Centraal-Amerika in de landen Costa Rica en Panama.

Het geel doodshoofdaapje behoort tot de familie Cebidae, die naast de doodshoofdaapjes ook de kapucijnapen en de klauwaapjes omvat. Binnen de familie Cebidae behoort het tot de geslacht van doodshoofdaapjes, bestaande uit vijf soorten. Het geel doodshoofdaapje de enige soort die buiten Zuid-Amerika in het wild leeft. De wetenschappelijke benaming Saimiri oerstedii is toegekend door Johannes Theodor Reinhardt. Hij gaf de benaming ter ere van collega bioloog en botanicus Anders Sandøe Ørsted.

Van het gele doodshoofdaapje bestaan twee ondersoorten:

Deze kleine aap bereikt maximaal een lichaamslengte van 26 tot 30 cm en weegt tussen de 600 en 950 gram. De kleur van deze in Centraal-Amerika voorkomende ondersoort van de doodshoofdaapjes verschilt redelijk van de groenige ondersoort welke voorkomt in zuidelijk Amerika. De vacht op de rug, handen en onderarmen is oranjebruin gekleurd. Op de schouders, relatief lange bovenarmen, en de basis van de staart is de vacht vlekkerig grijs. De borst en hals is lichtgrijs. Het kleine, ongeveer 6 cm grote hoofdje heeft een zwart-witte masker wat iets weg heeft van een doodshoofd. Hieraan heeft het aapje de Nederlandse benaming doodshoofdaapje te danken. De vacht boven op de kop is wat donkerder van kleur. De oren en de huid rondom de ogen zijn naakt en roze. De grijze staart is met een lengte van 36 tot 39 cm iets langer dan de lichaamslengte en eindigt in een zwarte punt. Deze aap heeft in tegenstelling tot veel andere primaten uit het Neotropisch gebied geen grijpstaart. De staart kan dus niet fungeren als een extra 'arm' maar wordt door het dier gebruikt voor balans tijdens het verplaatsen in de bomen.

Het zwartkap-doodshoofdaapje (Saimiri oerstedii oerstedii) is te herkennen aan de wat donkerdere vacht bovenop de kop. De andere ondersoort, het roodrug-doodshoofdaapje (Saimiri oerstedii citrinellus) heeft deze donkere kap niet.

In de afmeting is er seksueel dimorfisme, verschil tussen de mannetjes en de vrouwtjes: mannetjes zijn 15% zwaarder en iets groter dan de vrouwtjes. Ondanks de kleine afmeting heeft het doodshoofdaapje in verhouding tot het lichaam de grootste hersenen.

Het verspreidingsgebied van deze soort is beperkt. S. o. oerstedii is te vinden in Costa Rica vanaf Río Grande de Térraba en het Osa-schiereiland met het daarop gevestigde Nationaal park Corcovado, verder langs de kust tot de eilandengroep van de Golfo de Chiriquí in Panama. Het verspreidingsgebied van de S. o. citrinellus loopt vanaf Río Grande de Térraba naar het noorden tot aan het Herradura- en Dota-gebergte. Deze ondersoort is eenvoudig te zien in het Nationaal park Manuel Antonio. Hier houdt hij zich niet aan de parkgrenzen en komt hij regelmatig in de tuinen van de hotels rondom Quepos. Het dier leeft in de primaire en secondaire laaglandwouden tot een hoogte van 500 meter boven zeeniveau.

Het geel doodshoofdaapje is overdag actief. Hij leeft voornamelijk in de bomen en komt zelden op de grond. Het dier leeft in groepen welke meestal tussen de 20 tot 75 exemplaren bedraagt. Groepen van meer dan 100 exemplaren worden soms ook waargenomen. Ongeveer een derde deel van de groep bestaat uit mannetjes. Het overige deel zijn vrouwtjes en hun jongen. Het territorium bedraagt een oppervlakte van tussen de 35 tot 63 hectare. Territoria kunnen overlappen, met name in gebieden met beperkte leefruimte en voldoende voedsel. Overdag trekken de groepen door hun territoria op zoek naar voedsel. Hierbij leggen de dieren een afstand af welke ligt tussen de 2500 tot 4200 meter per dag. Over het algemeen blijft de groep overdag bij elkaar hoewel het voorkomt dat kleine groepjes zich overdag soms tijdelijk toch afsplitsen. In tegenstelling tot andere doodshoofdaapjes maakt het geel doodshoofdaapje elke nacht gebruik van dezelfde bomen als slaapplaats.

Gedurende de paartijd bestaat er een dominante hiërarchie binnen de groep. Deze dominantie is voornamelijk aanwezig tussen mannetjes die ongeveer even oud zijn. Buiten de paartijd heerst er geen sterke dominantie en is er geen uitgesproken hiërarchie. Er is geen dominantie van mannetjes over vrouwtjes of vice versa. Iets wat uniek is voor deze doodshoofdapensoort. In tegenstelling tot de andere soorten vecht deze soort onderling nauwelijks.

Diverse diersoorten maken gebruik van de activiteiten van de doodshoofdaap. Ettelijke soorten vogels volgen de apen om op deze manier insecten en kleine zoogdieren te pakken die worden opgeschrikt door de apen. Enkele vogelsoorten welke gebruikmaken van deze situatie zijn de bruinvleugel-muisspecht, Amazone-tangare en de tandwouw. Andere vogels zoals diverse soorten motmot en trogons maken hier in mindere mate gebruik van. Ook zoogdieren zoals de witsnuitneusbeer en pekari volgen de apen soms om het gevallen fruit te eten.

Het broedseizoen begint in de maand september. Alle vrouwtjes zijn in dezelfde periode ontvankelijk. Twee maanden voor aanvang van het broedseizoen worden de mannetjes groter. Reden hiervoor is een toename van water in het lichaam van het mannetje. Oorzaak hiervan is de omzetting van het mannelijke testosteron hormoon naar oestrogenen. Des te meer testosteron het mannetje produceert, des te groter hij groeit en des te meer voordeel hij hiervan heeft tijdens het broedseizoen. Vrouwtjes kiezen de grootste mannetjes uit om mee te paren. Over het algemeen zijn de grootste mannetjes ook de oudste mannetjes.

Soms verlaten mannetjes tijdelijk hun groep om zich aan te sluiten bij een nabije groep en te paren met vrouwtjes van deze groep. Vrouwtjes van deze groep zijn ontvankelijk voor de vreemde mannetjes. Hoewel mannetjes van de nieuwe groep indringers niet altijd dulden.

De draagtijd is zes maanden waarna er 1 jong wordt geboren. Alle jongen in de groep worden in dezelfde week geboren. Dit is in februari of maart. Slechts de helft overleeft de eerste zes maanden. De meeste jongen vallen ten prooi aan roofdieren. Jongen blijven ongeveer een jaar lang afhankelijk van hun moeder. Interval tussen de worpen is 12 maanden. Het jong wordt dus onafhankelijk van zijn moeder zodra zijn moeder een nieuw jong heeft geworpen. Vrouwtjes zijn na 2½ jaar geslachtsrijp. Bij mannetjes duurt dit langer, deze worden tussen hun vierde en vijfde levensjaar geslachtsrijp. Zodra de vrouwtjes volwassen zijn verlaten ze hun groep en sluiten ze zich aan bij andere groepen. Mannetjes blijven over het algemeen hun hele leven bij dezelfde groep.

De levensverwachting van deze aap in het wild is niet bekend. In gevangenschap zijn er exemplaren meer dan 15 jaar oud geworden.

Deze doodshoofdaap is een omnivoor. Maaltijden bestaan uit een variatie aan insecten en larven. Met name sprinkhanen en rupsen worden gegeten. Verder eet het dier spinnen, fruit, bladeren, boomschors, bloemen en nectar. Qua fruit eet het dier o.a. cecropia, vijgen, vruchten van diverse soorten palmen en cashew. Ook staan kleine gewervelden zoals vleermuizen, vogels, hagedissen en boomkikkers op het menu.

Het merendeel van het voedsel vindt het dier op hoogte van 5 tot 10 meter in de bomen. De bomen worden intensief doorzocht op mogelijke maaltijden. Ongeveer twee derde tot drie kwart van de dag wordt besteed aan het foerageren. De doodshoofdaap is een belangrijk dier voor zijn omgeving. Vanwege de strooptocht door de bomen is het dier een goede bestuiver voor bloemen. Stuifmeel blijft hangen aan de vacht van het dier waardoor het later bij andere bloemen in andere bomen terecht kan komen. Onder andere de passiebloem wordt op deze manier bestoven. Daarnaast zorgt het dier ook verspreiding van diverse soorten zaden. Zaden welke door de maag van het dier zijn gegaan komen later sneller uit.

Soms zorgt het dier rondom boerderijen voor overlast. Het dier lust namelijk ook graag mais, bananen, mango en koffiebonen. Bij de diverse hotels rondom Quepos worden diverse buffetten regelmatig geplunderd door de apen.

Het geluid wat de dieren produceren is niet een geluid welke men zou verwachten van een aap. De dieren maken een grote variatie van hoge, vogelachtig tjsilpende geluiden. Door deze vogel achtige geluiden worden de dieren niet altijd direct opgemerkt. De dieren bewegen zich echter ook vrij luidruchtig door de bomen voort waardoor ze hun aanwezigheid toch verraden.

Met name door de kleine afmeting valt het geel doodshoofdaapje regelmatig ten prooi aan diverse roofdieren. Zo valt hij ten prooi aan roofvogels, zowel wilde katachtigen als huiskatten, slangen, tayra, opossums, witsnuitneusberen en soms zelfs een toekan. De oudere mannetjes speuren de omgeving af voor roofdieren. Zodra er een potentieel gevaar wordt gespot slaat het mannetje alarm. De alarmkreet is een harde hoge piep waarna het dier wegduikt. De overige leden van de groep reageren hierop door direct beschutting te zoeken.

Voorheen nam men aan dat het geel doodshoofdaapje een subpopulatie was van een Zuid-Amerikaanse soort meegenomen naar Costa Rica door mensen. Als bewijs werd het zeer kleine leefgebied van het geel doodshoofdaapje aangedragen en de enorme afstand tussen deze soort en andere soorten in Zuid-Amerika. Uiteindelijke studie heeft als bewijs aangedragen dat deze soort inderdaad ontstaan is uit een soort in Zuid-Amerika, echter minimaal al meer dan 260.000 jaar geleden en mogelijk zelfs meer dan 4 miljoen jaar geleden.

Een populaire theorie is dat deze dieren leefden in Colombia gedurende het late mioceen of plioceen tijdperk en migreerden naar Centraal-Amerika. Deze soort was de voorouder van het huidige geel doodshoofdaapje. Rondom dezelfde periode migreerde ook de Zwarte brulaap richting Guatemala. De dieren passeerden door de istmus van Panama. Deze istmus, of landengte, sloot later weer vanwege het stijgen van het water in de oceanen om zich vervolgens 2 miljoen jaar geleden weer opnieuw te openen. Met de nieuwe opening van de istmus kwam er een nieuwe stroom van migranten waaronder de witschouderkapucijnaap en de zwarthandslingeraap. De nieuwe migranten verdrongen de oude migranten zoals het geel doodshoofdaapje en beperkten hiermee hun leefgebied.

De populatie van deze soort is drastisch afgenomen. Rondom 1970 telde men nog ongeveer 200.000 exemplaren. De huidige populatie bedraagt naar schatting rondom de 5.000 exemplaren. De grootste oorzaak van de sterke afname is ontbossing, jacht en illegale dierhandel. Een grote populatie leeft rondom Quepos een sterk ontwikkeld gebied ten aanzien van het toerisme. Veel dieren worden hier slachtoffer van de toegenomen verkeersdrukte ondanks het aanbrengen van grote aantallen gespannen apenbruggen over de wegen. Ook worden de dieren regelmatig slachtoffer van elektrocutie door de gespannen stroomkabels langs de weg. Costa Rica heeft diverse programma's voor het behoud van deze dieren. In Panama is een groot herbebossingsproject van start gegaan in de provincie Chiriqui, dat moet bijdragen aan het behoud van deze dieren.

In 2010 had deze aap nog steeds bij het IUCN, de status kwetsbaar. Met name omdat er nog steeds leefgebied verdwijnt, onder meer door de oprukkende palmplantages voor palmolie. In 2003 stond het dier echter nog genoteerd als bedreigd.

Het geel doodshoofdaapje (Saimiri oerstedii) is een kleine soort aap, die leeft in Centraal-Amerika in de landen Costa Rica en Panama.

Saimiri oerstedii é uma espécie do gênero Saimiri (macacos-de-cheiro) da costa do Oceano Pacífico da Costa Rica e Panamá. É restrito ao noroeste do Panamá na fronteira com a Costa Rica, e na parte central e sul da costa do Pacífico na Costa Rica, principalmente no Parque Nacional Manuel Antonio e no Parque Nacional Corcovado.

É um pequeno macaco com as costas laranja e uma distinta máscara facial preta e branca. Possui uma dieta onívora, comendo frutos, e outros materiais vegetais, invertebrados e pequenos vertebrados. Possui muitos predadores, como rapinantes, felinos e cobras. Vive em grandes grupos que contem entre 20 e 75 indivíduos. S. oerstedii possui uma das organizações sociais mais igualitárias entre os primatas. Fêmeas não formam hierarquia de dominância, e machos só a formam durante o período de acasalamento. Elas ficam sexualmente maduras com 2,5 anos de idade, e machos entre 4 e 5 anos. As fêmeas deixam o grupo quando adultas, mas os machos podem permanecer no grupo pela vida inteira. Samiri oerstedii pode viver até 15 anos de idade.

A população da espécie vem declinando, principalmente depois da década de 1970. Este declínio é causado pelo desmatamento, caça, e captura para o comércio de animais de estimação. Existem esforços para preservar a espécie, principalmente na Costa Rica. Apesar das ameaças às populações, em 2008 a IUCN atualizou seu estado de conservação de "em perigo" para "vulnerável".

Saimiri oerstedii é um membro da família Cebidae, uma família de macacos do Novo Mundo que reúne os macacos-de-cheiro, caiararas e saguis. Dentro desta família, é membro da subfamília Saimiriinae, na qual estão classificados os macacos-de-cheiro.[2] É uma das cinco espécies reconhecidas deste tipo de macaco, e a única delas que ocorre fora da América do Sul.[3] Faz parte do gênero Saimiri (Voigt, 1831), assim como todos os outros macacos-de-cheiro. Dentro desse gênero, S. oerstedii tem um parentesco mais próximo com S. sciureus e S. ustus, e essas três espécies formam o complexo de espécie S. sciureus.[4] O binomial Saimiri oerstedii foi dado por Johannes Theodor Reinhardt em homenagem a seu colega, o biólogo dinamarquês Anders Sandoe Oersted.

Há duas subespécies de S. oerstedii:[5]

Acreditava-se que essa espécie era derivada de indivíduos sul-americanos trazidos à América Central por humanos. Evidências para essa teoria incluem a pequena distribuição geográfica de S. oerstedii e um grande espaço "vazio" entre sua área de ocorrência e as de outras espécies de macacos-de-cheiro. Mas um estudo publicado em 2006, no qual foram analisados DNA nuclear e mitocondrial de primatas, demonstrou que S. oerstedii é, de fato, uma espécie distinta das demais, e que aparentemente divergiu dos macacos-de-cheiro sul-americanos entre 260 mil e 4 milhões de anos atrás.[6]

Uma hipótese popular é de que os macacos-de-cheiro da Colômbia do fim do Mioceno e início do Plioceno migraram para a América Central, tornando-se os ancestrais dos atuais macacos-de-cheiro centro-americanos.[7] De acordo com essa hipótese, Alouatta pigra também migrou para América Central nesta época. Passaram pelo istmo do Panamá, e eventualmente abriram caminho para outra onda de migração há cerca de 2 milhões de anos.[7] Esses últimos migrantes, ancestrais dos modernos macacos centro-americanos, competiram com os mais antigos migrantes, S. oerstedii e Alouatta pigra, restringindo a distribuição geográfica dessas espécies.[7]

A espécie é restrita à Costa Rica e Panamá e somente na costa do Oceano Pacífico.[8] Vai desde a parte central do litoral da Costa Rica até o oeste do Panamá.[8] Ocorre em dois parques nacionais da Costa Rica: Parque Nacional Manuel Antonio e Parque Nacional Corcovado, onde podem ser avistados por turistas, mas são menos comuns que Alouatta palliata e o Cebus capucinus.[9] Vive em florestas de terras baixas, e habitat a floresta secundária e a primária, mesmo que parcialmente derrubada.[10] S. oerstedii requer florestas com abundante vegetação em estratos baixos da floresta e parece ter dificuldades para sobreviver em florestas maduras e não perturbadas em que essa vegetação carece.[8][10]

Saimiri oerstedii difere em coloração dos macacos-de-cheiro sul-americanos.[11] Enquanto esses últimos tendem a ser esverdeados, S. oerstedii possui o dorso laranja, com ombros, quadris e cauda oliváceos, e a parte interior dos membros de cor branca. As mãos e pés são laranja.[11] Há um capuz preto na cabeça, e a ponta da cauda é preta.[11] Machos geralmente possuem esse capuz de cor mais clara que as fêmeas. A face é branca com um arco ao redor dos olhos, nariz e boca de cor preta.[11][8]

As duas subespécies são similares em coloração, mas diferem na tonalidade do capuz. A subespécie mais ao norte, que vive na costa do Pacífico na Costa Rica, possui esse capuz de cor mais clara quando comparado com a subespécie que ocorre mais ao sul, que vive no Panamá e em partes da Costa Rica próximas ao Panamá.[8] Essa última subespécie também possui membros e partes inferiores de cor amarelada.[6]

Adultos atingem um comprimento entre 26,6 cm e 29,1 cm, sem a cauda, e podem pesar entre 600 g e 950 g.[3][8] A cauda é mais longa que o corpo, tendo entre 36,2 e 38,9 cm de comprimento.[8] Como os outros macacos-de-cheiro, há considerável dimorfismo sexual. Em média, machos são 16% maiores do que as fêmeas.[3] Machos pesam cerca de 829 g, e fêmeas, cerca de 695 g.[3] Macacos-de-cheiro possuem grandes cérebros em relação ao corpo, pesando cerca de 25,7 g, o que corresponde a 4% da massa corporal.[11][12] Ao contrário de seus parentes próximos, como os macacos-pregos, macacos-aranhas e bugios, a sua cauda não é completamente preênsil, exceto em recém-nascidos, e ela é utilizada primariamente para manutenção de equilíbrio.[13][14]

Os macacos-de-cheiro são arborícolas e diurnos, e frequentemente se locomovem pelas árvores com os quatro membros (quadrupedalismo).[11] Vivem em grupos contendo vários machos e fêmeas adultos e juvenis.[3][10] O tamanho do grupo tende a ser menor do que as espécies sul-americanas, mas ainda é maior que muitos outros macacos do Novo Mundo.[3][10] O grupo geralmente tem entre 20 e 75 indivíduos, com uma média de 41 macacos por grupo.[3][10] Grupos com mais de 100 indivíduos podem ocorrer, mas acredita-se que são fusões temporárias de dois grupos.[1] Em média, grupos contém 60% a mais de fêmeas.[3]

S. oerstedii possui territórios entre 35 e 63 hectares.[10] Territórios podem se sobrepor, especialmente em grandes áreas protegidas, como o Parque Nacional Manuel Antonio. Menos sobreposição ocorre em áreas mais fragmentadas.[10] O deslocamento diário está entre 2500 e 4200 m.[15] Ao contrpario de outras espécies de macacos, os grupos não se separam em grupos de forrageio durante o dia. Indivíduos podem se isolar do grupo para engajar em diferentes atividades várias vezes ao dia, o que acaba dispersando o grupo em 1,2 hectares em um dado momento. O grupo tende a dormir na mesma árvore toda noite por meses, ao contrário das outras espécies do mesmo gênero.[16]

Não há hierarquia de dominância entre as fêmeas, e elas não formam coalizões.[1][3] Machos do grupo são geralmente parentes e podem formar coalizões muito estáveis e duradouras, e somente formam hierarquia de dominância durante o período de estro das fêmeas.[3] Isto é especialmente o caso entre machos de mesma idade.[10] Machos e fêmeas não estabelecem dominância entre si, e é um sistema social único aos primatas centro-americanos. Em espécies da América do Sul, as fêmeas (S. boliviensis) ou os machos (S. sciureus) são dominantes em relação ao outro sexo, e ambas as espécies formam hierarquias bem estabelecidas[1] Machos dos macacos-de-cheiro costarriquenhos são conhecidos por formarem relações muito fortes entre si.[17]

Embora as espécies sul-americanas frequentemente se deslocam e comem junto com os caiararas e macacos-pregos, S. oerstedii raramente forma associações com Cebus capucinus. Isto parece se relacionar ao fato de que os alimentos consumidos por S. oerstedii estão distribuídos em trechos menores e mais dispersos em comparação aos macacos-de-cheiro sul-americanos.[3] Como resultado da diferença na distribuição de alimento, associações com os macacos-pregos resultam em altos custos de forrageamento aos macacos-de-cheiro centro-americanos.[3] Ademais, enquanto os machos de C. capucinus estão alertas aos predadores, eles devotam mais atenção a potenciais machos rivais, e passam menos tempo se defendendo de predadores do que seus parentes sul-americanos.[3] Portanto, associações com caiararas providenciam menos benefícios da proteção contra predadores e impõem maiores custos de forrageio para os macacos-de-cheiro centro-americanos.[3][14][18][19]

Certas espécies de aves se associam com S. oerstedii. Aves seguem os macacos numa tentativa de predar insetos e pequenos vertebrados que esses macacos espantam. No Parque Nacional Corcovado, espécies de aves regularmente seguem macacos-de-cheiro, como Harpagus bidentatus, Eucometis penicillata e Dendrocincla anabatina, mas outras espécies de arapaçus e espécies de juruvas e Trogoniformes também fazem isso. Esta atividade aumenta durante a estação chuvosa, quando artrópodes são mais difíceis de serem encontrados.[10]

Saimiri oerstedii é onívoro. Sua dieta inclui insetos e larvas, (especialmente gafanhotos e lagartas), aranhas, frutos, casca de árvores, folhas, flores e néctar.[10][16] Também se alimentam de pequenos vertebrados, incluindo morcegos, insetos, lagartos e pererecas. Forrageam nos estratos médio e baixos da floresta, tipicamente entre 4,5 m e 9,1 m de altura.[10][16] Gastam até 75% do dia forrageando. É difícil encontrar seus alimentos preferidos no fim da estação chuvosa, quando poucos artrópodes estão disponíveis.[8]

Possuem um método único de capturar morcegos da espécie Uroderma bilobatum.[10] Olham para os morcegos pousados, procurando pelas tendas desses animais que são formadas por folhas dobradas.[10] Quando encontrado um morcego, o macaco-de-cheiro escala até estratos altos das árvores e pulam das tendas, tentando desalojar o morcego. Se o morcego caído não voa para longe, o macaco o agarra no chão e o come.[10]

S. oerstedii é um importante dispersor de sementes e polinizador de certas flores, incluindo Passiflora.[10] Enquanto não sendo uma praga na agricultura, eles podem comer milho, café, bananas e mangas.[10] Outros frutos ingeridos incluem os da embaúba, legumes, figos, de palmeiras, de Symphonia globulifera, de Pseudolmedia, de Xylopia e cajueiros selvagens.[10][16]

Saimiri oerstedii é um macaco barulhento. Produz muitos assovios, guinchos e gorjeios.[8] O deslocamento através da floresta é feito acompanhado desses sons, além de movimentação da vegetação feita pelo deslocamento.[8] Tem quatro vocalizações principais, que são descritas como "cacarejos", "cacarejos distorcidos", "piados" e "chilros".[11]

Predadores da espécie incluem rapinantes, felinos e cobras. Serpentes peçonhentas e constritoras se alimentam de macacos-de-cheiro. Aves de rapina são predadores particularmente efetivos de S. oerstedii.[3] Os machos mais velhos se responsabilizam na detecção de predadores.[1][10] Quando um predador é detectado os animais emitem um piado de alarme muito agudo e corre em busca de abrigo. Todos os outros indivíduos que ouvem o alarme correm também. Esses macacos são particularmente cuidadosos com aves de rapina, e dão alarmes com qualquer objeto que lembre esses predadores, incluindo pequenos aviões, indo para lugares mais seguros.[16]

A detecção de predadores pelos machos é particularmente importante durante o período que os filhotes nascem. Aves de rapina passam significativamente mais tempo perseguindo macacos-de-cheiro neste período, e atacam um número significativo de recém-nascidos. Outros animais que predam recém-nascidos da espécie são tucanos, a irara, gambás, quatis, cobras e até mesmo macacos-aranhas.[16]

Existe estação de acasalamento sendo em setembro.[10] Todas as fêmeas entram no estro praticamente ao mesmo tempo. Um mês ou dois antes dessa estação começar, os machos se tornam maiores.[16] Não é necessariamente por conta de massa muscular extra, mas por alterações na quantidade de água no corpo dos machos. Isto é causado pela conversão da testosterona em estrógeno: portanto, quanto mais testosterona eles produzem, maiores ficam.[16] Já que machos dentro de um grupo não são observados brigando pelo acesso à fêmeas no estro, e nem tentativas de forcá-las a copular, acredita-se que a escolha da fêmea é que determina qual macho irá copular. Fêmeas tendem a escolher machos que crescem mais durante a estação de acasalamento.[16] Isto deve estar relacionado ao fato de que machos maiores são geralmente os mais velhos e mais eficientes em detectar predadores, ou isso pode ser um caso de seleção sexual.[16]

Machos às vezes deixam o grupo por curtos períodos durante a estação de acasalamento para tentar acasalar com fêmeas de outros grupos. Fêmeas são receptivas aos machos de outros grupos, embora os machos residentes tentem repelir esses intrusos.[16] A gestação dura seis meses, e os juvenis nascem todos em uma semana entre fevereiro e março. Geralmente, dão à luz a um filhote por vez.[3][10][16]

Apenas 50% dos filhotes sobrevivem por mais de seis meses, principalmente devido à predação por aves de rapina.[3] Os juvenis permanecem dependentes da mãe por cerca de um ano.[10] Fêmeas dão à luz a cada 12 meses, portanto, o primeiro filhote se torna independente logo que nasce o mais novo. Elas se tornam sexualmente maduras com dois anos e meio de idade, enquanto os machos atingem a maturidade sexual bem mais tarde, entre os 4 e 5 anos. As fêmeas deixam o grupo natal logo após serem capazes de se reproduzir, enquanto que os machos geralmente permanecem nele por toda a vida. Este comportamento é diferente dos macacos-de-cheiro sul-americanos, cujos machos se dispersam para outros grupos, ou ambos os sexos fazem isso. Os machos da mesma idade tendem a associar-se uns aos outros em subgrupos etários. Quando atingem a maturidade sexual, um subgrupo pode escolher deixar o grupo e tentar conquistar outro bando a fim de aumentar as oportunidades reprodutivas.[3]

A expectativa de vida de S. oerstedii em liberdade é desconhecida, mas indivíduos em cativeiro podem viver até mais de 15 anos.[10] Outras espécies de macacos-de-cheiro são conhecidas por viverem mais de 20 anos.[3]

A densidade populacional tem sido estimada em 36 macacos por km² na Costa Rica e 130 no Panamá.[15] Estima-se que a população da espécie diminuiu de 200 mil indivíduos na década de 1970, para menos de 5 mil.[9] Isto se deve à desflorestação, caça e captura para o comércio de animais de estimação.[9] Há significantes esforços na Costa Rica para preservar este macaco da extinção.[20] Um projeto de reflorestamento no Panamá tenta preservar populações da província de Chiriquí.[21]