fi

nimet breadcrumb-navigoinnissa

El ratpenat de bigotis petits (Myotis alcathoe) és un petit ratpenat de la família dels vespertiliònids descrita l'any 2001 per Otto von Helversen i Klaus-Gerhard Heller i que encara és força desconeguda, en part a causa de la seva raresa. Habita Europa, en petites valls amb cursos d'aigua i arbres caducifolis. Es tem que pugui estar en perill d'extinció.

Inicialment es creia que Myotis alcathoe habitava el sud-est d'Europa, però darrerament s'han trobat exemplars a Suècia, Anglaterra o França, entre altres països. També ha estat identificat a punts d'Espanya com la Rioja, Navarra i el sistema ibèric septentrional, però no fou fins al 2007 que fou trobat a Catalunya, al Parc Natural del Montseny per Carles Flaquer i Antoni Arrizabalaga, dos investigadors del Museu de Granollers.[1]

Aquest ratpenat és el més petit dins les espècies del gènere Myotis que habiten Europa, però tot i aquest fet, la seva idenficació és dificultosa. El seu cos fa uns 4 cm, (assolint uns 20 cm d'envergadura amb les ales desplegades) i pesa entre 3,5 i 5,5 grams. El color del pèl és marró vermellós en les parts superiors i marró a sota, mentre les ales són marrons.[2] Té la ecolocació de freqüència més alta de les espècies europees del gènere Myotis.

El ratpenat de bigotis petits (Myotis alcathoe) és un petit ratpenat de la família dels vespertiliònids descrita l'any 2001 per Otto von Helversen i Klaus-Gerhard Heller i que encara és força desconeguda, en part a causa de la seva raresa. Habita Europa, en petites valls amb cursos d'aigua i arbres caducifolis. Es tem que pugui estar en perill d'extinció.

Netopýr alkathoe (Myotis alcathoe) je druh netopýra z čeledi netopýrovití. Podobá se netopýru vousatému (Myotis mystacinus) a netopýru Brandtovu (Myotis brandtii). Tento netopýr byl popsán v roce 2001. V ČR se pro něj nejdříve používal název netopýr menší, ale později bylo přijato označení netopýr alkathoe.[2]

Netopýr alkathoe je jedním z nejmenších netopýrů. Jeho předloktí je dlouhé nejvýše 32,5 mm, délka tlapky dosahuje maximálně 6 mm a hmotnost těla se pohybuje od 4 do 5 g. Oproti všem druhům, kterým se podobá, je menší. Srst je hnědá až rezavá. Má světlé okolí očí a ušní boltce, které jsou uvnitř bledé. [3]

První typoví netopýři alkathoe pocházejí z Řecka. Ale jeho výskyt byl již potvrzen v mnoha evropských zemích. V ČR byl poprvé odchycen v roce 2005 v Lánské oboře.

Pro své úkryty využívá pukliny ve vysokých listnatých stromech. Obývá převážné dlouhověké lesy. V létě v lesích i loví, ale v ostatních obdobích loví i na březích vodních toků a v zahradách. [3][4]

Netopýr alkathoe (Myotis alcathoe) je druh netopýra z čeledi netopýrovití. Podobá se netopýru vousatému (Myotis mystacinus) a netopýru Brandtovu (Myotis brandtii). Tento netopýr byl popsán v roce 2001. V ČR se pro něj nejdříve používal název netopýr menší, ale později bylo přijato označení netopýr alkathoe.

Die Nymphenfledermaus (Myotis alcathoe) ist eine Fledermausart aus der Gattung der Mausohren. Sie wurde erst 2001 auf Basis genetischer Analysen und morphologischer Merkmale als eigene Art beschrieben. Die Nymphenfledermaus wurde erstmals in Griechenland und Ungarn von einer Forschergruppe um Professor Otto von Helversen nachgewiesen. Sowohl ihr wissenschaftlicher als auch ihr deutscher Name geht auf die griechische Mythologie zurück. Die Nymphe Alcathoe, Tochter des Minyas, wurde von Dionysos zusammen mit ihren Schwestern in Fledermäuse verwandelt als Strafe für ihren Boykott eines zu Ehren von Dionysos veranstalteten Festes. Professor Helversen wählte diesen Namen, da die Art in einem Gebiet gefunden wurde, das durch abgelegene Schluchten und Ufergehölz dem ähnelt, in welchem sich die Tragödie zugetragen haben soll.

Der erste Nachweis dieser Art in der Schweiz gelang 2002 durch Fänge vor einer Höhle im Waadtländer Jura in einer Höhe von 1500 m ü. M. Auch in Frankreich und Deutschland wurde diese Art nachgewiesen.

Die Nymphenfledermaus ist der Großen Bartfledermaus (Myotis brandtii) und der Kleinen Bartfledermaus (Myotis mystacinus) sehr ähnlich. Jedoch ist sie etwas kleiner als die beiden Bartfledermausarten und unterscheidet sich etwas im Gebiss von ihnen. Des Weiteren ist die Frequenz ihrer Ultraschallortungsrufe höher als bei allen anderen Arten ihrer Gattung.

Die Nymphenfledermaus bevorzugt naturbelassene, von Wasser durchströmte Gebiete mit altem Mischwaldbestand,[1] wie man sie in Tälern oder Alluvialwäldern (Sumpfwälder mit hochstämmigen Bäumen) finden kann.

Die Art wurde bisher in Europa in Albanien, Bulgarien, Deutschland[2], Schweden[3], Frankreich, Griechenland, Polen, Schweiz, Slowakei, Spanien, Ungarn, Großbritannien und in der Türkei nachgewiesen. Der nördlichste deutsche Fund wurde im Kyffhäusergebirge gemacht.[1]

Da es sich bei der Nymphenfledermaus um eine relativ neu nachgewiesene Art handelt und über ihre Verbreitung erst sehr wenig bekannt ist, wurde in der Schweiz noch keine Einstufung in eine Gefährdungskategorie festgelegt. Man kann jedoch davon ausgehen, dass die Nymphenfledermaus bisher mit den Bartfledermäusen verwechselt wurde und da diese als gefährdet eingestuft sind, gilt dies mindestens auch für die Nymphenfledermaus. Vor allem die Abhängigkeit von altem Baumbestand stellt ein Problem dar.

Die Nymphenfledermaus (Myotis alcathoe) ist eine Fledermausart aus der Gattung der Mausohren. Sie wurde erst 2001 auf Basis genetischer Analysen und morphologischer Merkmale als eigene Art beschrieben. Die Nymphenfledermaus wurde erstmals in Griechenland und Ungarn von einer Forschergruppe um Professor Otto von Helversen nachgewiesen. Sowohl ihr wissenschaftlicher als auch ihr deutscher Name geht auf die griechische Mythologie zurück. Die Nymphe Alcathoe, Tochter des Minyas, wurde von Dionysos zusammen mit ihren Schwestern in Fledermäuse verwandelt als Strafe für ihren Boykott eines zu Ehren von Dionysos veranstalteten Festes. Professor Helversen wählte diesen Namen, da die Art in einem Gebiet gefunden wurde, das durch abgelegene Schluchten und Ufergehölz dem ähnelt, in welchem sich die Tragödie zugetragen haben soll.

Der erste Nachweis dieser Art in der Schweiz gelang 2002 durch Fänge vor einer Höhle im Waadtländer Jura in einer Höhe von 1500 m ü. M. Auch in Frankreich und Deutschland wurde diese Art nachgewiesen.

The Alcathoe bat (Myotis alcathoe) is a European bat in the genus Myotis. Known only from Greece and Hungary when it was first described in 2001, its known distribution has since expanded as far as Portugal, England, Sweden, and Russia. It is similar to the whiskered bat (Myotis mystacinus) and other species and is difficult to distinguish from them. However, its brown fur is distinctive and it is clearly different in characters of its karyotype and DNA sequences. It is most closely related to Myotis hyrcanicus from Iran, but otherwise has no close relatives.

With a forearm length of 30.8 to 34.6 mm (1.21 to 1.36 in) and body mass of 3.5 to 5.5 g (0.12 to 0.19 oz), Myotis alcathoe is a small bat. The fur is usually reddish-brown on the upperparts and brown below, but more grayish in juveniles. The tragus (a projection on the inner side of the ear) is short, as is the ear itself, and the inner side of the ear is pale at the base. The wings are brown and the baculum (penis bone) is short and broad. M. alcathoe has a very high-pitched echolocation call, with a frequency that falls from 120 kHz at the beginning of the call to about 43 kHz at the end.

Usually found in old-growth deciduous forest near water, Myotis alcathoe forages high in the canopy and above water and mostly eats flies. The animal roosts in cavities high in trees. Although there are some winter records from caves, it may also spend the winter in tree cavities. Several parasites have been recorded on M. alcathoe. The IUCN Red List assesses Myotis alcathoe as "data deficient", but it is considered threatened in several areas because of its rarity and vulnerability to habitat loss.

The whiskered bat (Myotis mystacinus) and similar species in Eurasia (collectively known as "whiskered bats") are difficult to distinguish from each other; for example, the distantly related Brandt's bat (Myotis brandtii) was not recognized as distinct from M. mystacinus until the 1970s.[2] Small, unusual M. mystacinus-like bats were first recorded in Greece in the 1970s, but it was not until the advent of genetic studies that these bats could be confirmed as representing a distinct species, named Myotis alcathoe.[3] In 2001, the species was described by German zoologists Otto von Helversen and Klaus-Gerhard Heller on the basis of specimens from Greece and Hungary.[4] Although it also differs from other whiskered bats by morphological characters, Myotis alcathoe is most clearly distinct in its genetics, including DNA sequences and the location of the nucleolus organizer regions.[5] Two studies used microsatellite markers on European whiskered bats: the first one used western European samples and recovered three well-defined species clusters for M. alcathoe, M. brandtii and M. mystacinus;[6] the other one, conducted in Poland, suggesting a high level of hybridization with other whiskered bats that would further complicate attempts to identify M. alcathoe morphologically.[7]

Von Helversen and Heller argued that none of the old names now considered synonyms of M. mystacinus could apply to M. alcathoe, because these names all have their type localities in western or central Europe.[5] However, the more recent discovery of M. alcathoe further to the west renders it possible that an older name may be discovered.[8] In addition, Russian researcher Suren Gazaryan has suggested that the name caucasicus Tsytsulina, 2000 (originally proposed for a subspecies of M. mystacinus from the Caucasus) may prove to be applicable to M. alcathoe; in that case, the species would be renamed Myotis caucasicus.[9] However, a later analysis instead attributed the name caucasicus to the eastern species Myotis davidii.[10] M. alcathoe may have remained undetected in Germany for so long because bat researchers did not sample its preferred habitats and would dismiss unusual-looking whiskered bats as being abnormal M. mystacinus or M. brandtii.[11]

On the basis of mitochondrial DNA sequence analysis, Myotis alcathoe first appeared close to Geoffroy's bat (Myotis emarginatus) of southern Europe, North Africa, and southwestern Asia.[12] However, a study of the mitochondrial cytochrome b gene incorporating many Myotis species did not support this relationship, and could not place M. alcathoe securely at a specific position among Eurasian Myotis.[13] In 2012, a closely related species, Myotis hyrcanicus, was named from Iran. It is morphologically difficult to distinguish from M. alcathoe, but sufficiently distinct genetically to be considered a separate species.[14]

The population of Myotis alcathoe in Krasnodar Krai on the Russian Black Sea coast is genetically distinct from populations in the rest of Europe and is accordingly recognized as a subspecies, Myotis alcathoe circassicus, first named in 2016.[15] Within the remaining populations (subspecies Myotis alcathoe alcathoe), two groups with slightly divergent mitochondrial DNA sequences (separated by 1.3 to 1.4% sequence divergence) are distinguishable within the species, which probably correspond to different glacial refugia where M. alcathoe populations survived the last glacial period. One, known as the "Hungarian" group, has been recorded from Spain, France, Austria, Hungary, and Slovakia, and probably corresponds to a refugium in Iberia; the other, the "Greek" group, is known only from Greece and Slovakia.[16]

The specific name, alcathoe, refers to Alcathoe, a figure from Greek mythology who was turned into a bat when she refused the advances of the god Dionysus. She was associated with gorges and small streams, the preferred habitat of Myotis alcathoe in Greece.[17] In their original description, von Helversen and colleagues described her as a nymph,[17] and the common name "nymph bat" has therefore been used for this species.[18] However, none of the classical sources speak of Alcathoe as a nymph; instead, she was a princess, the daughter of King Minyas of Orchomenos. Therefore, Petr Benda recommended in 2008 that the common name "Alcathoe bat" or "Alcathoe myotis" be used instead.[19] Other common names include "Alcathoe's bat"[20] and "Alcathoe whiskered bat".[1] The name of the subspecies M. a. circassicus refers to Circassia, a historical region of the northwestern Caucasus.[21]

Myotis alcathoe is the smallest European Myotis species. The fur is brownish on the upperparts, with a reddish tone in old specimens, and a slightly paler gray-brown below.[3] Younger animals may be completely gray-brown.[22] The brown fur distinguishes adult M. alcathoe from other whiskered bats, but juveniles cannot be unambiguously identified on the basis of morphology.[23] M. alcathoe is similar to Daubenton's bat (Myotis daubentonii) and M. emarginatus in color.[24] On the upper side of the body, the hairs are 6 to 8 mm long and have dark bases and brown tips. The hairs on the lower side of the body are only slightly paler at the tip than at the base.[5]

The face and the upper lips are reddish to pink,[25] not dark brown to black as in M. mystacinus.[26] Although most of the face is hairy, the area around the eyes is bare.[27] The nostrils are heart-shaped,[25] and their back end is broad, as in M. brandtii, not narrow as in M. mystacinus.[28] Several glands are present on the muzzle, most prominently in reproductively active males. The ears are brown and are lighter on the inside than the outside. There is a notch at the edge of the ear, and the pointed tragus (a projection inside the ear that is present in some bats) extends up to this notch;[5] the tragus is longer, extending beyond the notch, in both M. brandtii and M. mystacinus.[29] The base of the inner side of the ear is white; it is much darker in M. mystacinus.[30] The feet and the thumbs are very small. The small size of the ear, tragus, feet, and thumb distinguishes M. alcathoe from the slightly larger M. mystacinus and M. brandtii,[5] but the feet are relatively larger than in M. mystacinus.[27]

The wings are brown, but lighter than those of M. mystacinus.[31] The plagiopatagium (the portion of the wing between the last digit and the hindlegs) is attached to the fifth toe. The tail extends only about 1 mm beyond the back margin of the uropatagium (the portion of the wing membrane between the hindlegs). The calcar, a cartilaginous spur supporting the uropatagium, is slender. With a width around 1.3 mm, the penis is narrow,[5] and it lacks a broadened tip (except in one Croatian specimen).[32] The baculum (penis bone) is about 0.5 mm long.[5] The short and broad shape of this bone distinguishes M. alcathoe from M. brandtii as well as M. ikonnikovi.[33]

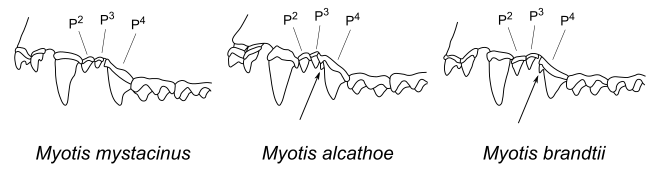

The skull is similar in shape to that of M. mystacinus and M. brandtii, but the front part of the braincase is higher. The second and third upper premolars (P2 and P3) are tiny and pressed against the upper canine (C1) and fourth premolar (P4).[5] The canine is less well-developed than in M. mystacinus.[23] There is a clear cusp present on the side of the P4. The accessory cusp known as the protoconule is present on each of the upper molars when they are unworn. M. mystacinus lacks the P4 cusp and the protoconules on the molars,[5] but M. brandtii has an even larger cusp on P4.[29] The Caucasus subspecies, M. alcathoe circassicus, has a relatively narrower skull and longer upper molars.[15]

As usual in Myotis species, M. alcathoe has a karyotype consisting of 44 chromosomes, with the fundamental number of chromosomal arms equal to 52. However, a 1987 study already found that M. alcathoe (then called "Myotis sp. B") differs from both M. mystacinus and M. brandtii in the pattern of active nucleolus organizer regions on the chromosomes.[5] M. alcathoe also differs from other Myotis species in the sequences of the mitochondrial genes 12S rRNA and NADH dehydrogenase subunit 1 by at least 5% and 13%, respectively.[34]

M. alcathoe has the highest-frequency echolocation call of any European Myotis. In open terrain, the call has an average duration of 2.5 ms, but it may be up to 4 ms long. At the beginning, its frequency is around 120 kHz, but it then falls fast, subsequently falls slightly slower, and at the end falls faster again. The call reaches its highest amplitude at around 53 kHz.[35] It terminates at around 43 to 46 kHz; this characteristic is especially distinctive.[36] In different experiments, the time between calls was found to be around 85 and 66 ms, respectively.[37] The high-pitched call may be an adaptation to the animal's occurrence in dense vegetation.[38]

Head and body length is about 4 cm (1.6 in) and wingspan is around 20 cm (7.9 in).[39] Forearm length is 30.8 to 34.6 mm (1.21 to 1.36 in), tibia length is 13.5 to 15.9 mm (0.53 to 0.63 in), hindfoot length is 5.1 to 5.8 mm (0.20 to 0.23 in), and body mass is 3.5 to 5.5 g (0.12 to 0.19 oz).[3] In the subspecies circassicus, forearm length is 30.1 to 34.2 millimetres (1.19 to 1.35 in) and ear length is 13.0 to 14.6 millimetres (0.51 to 0.57 in).[15]

Although Myotis alcathoe was initially known only from Greece and Hungary and was thought to be restricted to southeast Europe, records since then have greatly expanded its range, and it is now known from Portugal, Spain and England to Sweden and European Turkey.[40] In several European countries, focused searches were conducted to detect its occurrence.[41] Its habitat generally consists of moist, deciduous, mature forest near streams, for example in ravines or in alluvial forest (forest near a river),[42] where there are many decaying trees that the bat can use as roosting sites.[43] In Germany, its preferred habitat consists of mixed deciduous forest.[44] In the south of the continent, it usually occurs in mountain ranges, but the factors affecting its distribution in the north are less well known. Its range appears to be similar in shape to those of the greater and lesser horseshoe bats (Rhinolophus ferrumequinum and R. hipposideros) and Geoffroy's bat (Myotis emarginatus).[42] It may yet be found in other European countries, such as Ireland and Moldova.[45] Although there are abundant records from some areas, such as France and Hungary, the species appears to be rare in most of its range.[46]

Known records are as follows:

Early records of Myotis ikonnikovi—now known to be an eastern Asian species—from Ukraine, Bulgaria, and Romania may also pertain to this species.[68] Because whiskered bats in many cases cannot easily be distinguished from each other without the use of genetic methods, some listings do not differentiate between them; records of M. alcathoe and/or M. mystacinus and/or (in some cases) M. brandtii have been reported from Bulgaria,[103] Belgium,[104] and Montenegro.[105]

Myotis alcathoe is a rare species with narrow ecological requirements.[106] According to a study in the Czech Republic, the diet of Myotis alcathoe mostly consists of nematoceran flies, but caddisflies, spiders, small lepidopterans, and neuropterans are also taken.[107] However, in eastern Slovakia moths were most common, though ants and nematocerans were also common prey items.[86] The presence of spiders in the diet suggests that the species gleans prey from foliage. It forages mainly high in the canopy and over water,[61] and is often found in dense vegetation.[108] When caught, individuals of M. alcathoe are much calmer than M. mystacinus or M. brandtii.[109]

M. alcathoe lives in small groups.[110] In Greece, a maternity colony, containing three females and two juveniles, has been found in a plane tree.[68] Additional roosts were found high in oak trees in Baden-Württemberg[110] and Saxony-Anhalt.[44] Twenty-seven roosting sites have been found in the Czech Republic, all but one in trees (the last was in a concrete pole). Most of the tree roosts were in oaks (Quercus robur); others were in limes (Tilia cordata), birches (Betula pendula), and various other species.[111] Its strong preference for roosting sites in trees is unusual among European bats.[112] Roosts tend to be located high in the canopy,[113] and are often in old trees.[114] In summer, roosts may contain large groups of up to 80 individuals, but autumn roosts in the Czech Republic are occupied by smaller groups.[113] M. alcathoe swarms from late July to mid-September in southern Poland.[7]

In Saxony-Anhalt, the species forages deep in valleys when temperatures are above 10 °C (50 °F), but on warmer slopes or rocky areas when it is colder.[115] There, M. alcathoe is relatively easy to capture in August, because M. brandtii and M. mystacinus already start swarming in late July.[116] Although there are some records of M. alcathoe in caves during the winter, it is also possible that animals spend the winter in tree cavities, and whether swarming behavior occurs in M. alcathoe is unclear.[117] An animal found in a cave in Saxony-Anhalt in January was not sleeping deeply.[115] Reproduction may also take place in caves, but pregnant females have been found as late as June.[118] Relatively many juveniles are caught between July and September.[11] In England, one individual of M. alcathoe was captured in 2003 (and identified at the time as M. brandtii) and again in 2009.[119] Three individuals that were telemetrically tracked (in eastern France, Thuringia, and Baden-Württemberg, respectively) moved only 800 m (2,600 ft), 935 m (3,068 ft), and 1,440 m (4,720 ft) from their night quarters; M. brandtii and M. mystacinus tend to move over longer distances.[120] A study in Poland suggested frequent hybridization among M. alcathoe, M. brandtii, and M. mystacinus sharing the same swarming sites, probably attributable to male-biased sex ratios (1.7:1 in M. alcathoe), a polygynous mating system, and the high number of bats at swarming sites.[121] M. alcathoe showed a particularly high proportion of hybrids, perhaps because it occurs at lower densities than the other two species.[7]

The following parasites have been recorded from Myotis alcathoe:

Because Myotis alcathoe remains poorly known, it is assessed as "Data Deficient" on the IUCN Red List.[1] However, it may be endangered because of its narrow ecological preferences.[118] Reservoir construction may threaten the species' habitat in some places; two Greek sites where it has been recorded have already been destroyed.[68] Forest loss is another possible threat,[1] and the species may be restricted to undisturbed habitats.[132] Because of its patchy distribution and likely small population, it probably does not easily colonize new habitats.[118] The species is protected by national and international measures, but the IUCN Red List recommends further research on various aspects of the species as well as efforts to increase public awareness of the animal.[1] In addition, old forests need to be conserved and the species' cave roosts need to be protected.[133]

In Catalonia, the species is listed as "Endangered" in view of its apparent rarity there.[134] The Red List of Germany's Endangered Vertebrates lists M. alcathoe as "Critically Endangered" as of 2009.[135] In the Genevan region, the species is also listed as "Critically Endangered" as of 2015.[96] In Hungary, where the species is probably not uncommon in suitable habitat,[136] it has been protected since 2005.[137] However, the species is declining there and is threatened by habitat loss and disturbance of caves.[138]

The Alcathoe bat (Myotis alcathoe) is a European bat in the genus Myotis. Known only from Greece and Hungary when it was first described in 2001, its known distribution has since expanded as far as Portugal, England, Sweden, and Russia. It is similar to the whiskered bat (Myotis mystacinus) and other species and is difficult to distinguish from them. However, its brown fur is distinctive and it is clearly different in characters of its karyotype and DNA sequences. It is most closely related to Myotis hyrcanicus from Iran, but otherwise has no close relatives.

With a forearm length of 30.8 to 34.6 mm (1.21 to 1.36 in) and body mass of 3.5 to 5.5 g (0.12 to 0.19 oz), Myotis alcathoe is a small bat. The fur is usually reddish-brown on the upperparts and brown below, but more grayish in juveniles. The tragus (a projection on the inner side of the ear) is short, as is the ear itself, and the inner side of the ear is pale at the base. The wings are brown and the baculum (penis bone) is short and broad. M. alcathoe has a very high-pitched echolocation call, with a frequency that falls from 120 kHz at the beginning of the call to about 43 kHz at the end.

Usually found in old-growth deciduous forest near water, Myotis alcathoe forages high in the canopy and above water and mostly eats flies. The animal roosts in cavities high in trees. Although there are some winter records from caves, it may also spend the winter in tree cavities. Several parasites have been recorded on M. alcathoe. The IUCN Red List assesses Myotis alcathoe as "data deficient", but it is considered threatened in several areas because of its rarity and vulnerability to habitat loss.

El murciélago ratonero bigotudo pequeño (Myotis alcathoe) es una especie de quiróptero de la familia Vespertilionidae. Esta especie ha sido descrita recientemente y es poco conocida.[1] La fórmula dentaria de M. alcathoe es 2.1.3.3 3.1.3.3 {displaystyle {frac {2.1.3.3}{3.1.3.3}}}

M. alcathoe es el más pequeño entre los murciélagos bigotudos de Europa y utiliza las frecuencias en sus llamadas de ecolocalización más altas de todas las especies europeas pertenecientes a su género. Prefiere cazar en valles pequeños con árboles de hoja caduca cercanos a cursos de agua. Los antiguos registros de Grecia y Hungría indican una distribución importante en el sudeste de Europa.[2] Las frecuencias utilizadas por el M. alcathoe para la ecolocalización varían entre 34-102 kHz, llegando al pico de energía en 53 kHz y con una duración promedio de 3.0 ms.[3][4]

El murciélago ratonero bigotudo pequeño (Myotis alcathoe) es una especie de quiróptero de la familia Vespertilionidae. Esta especie ha sido descrita recientemente y es poco conocida. La fórmula dentaria de M. alcathoe es 2.1.3.3 3.1.3.3 {displaystyle {frac {2.1.3.3}{3.1.3.3}}}

Myotis alcathoe Myotis generoko animalia da. Chiropteraren barruko Myotinae azpifamilia eta Vespertilionidae familian sailkatuta dago

Myotis alcathoe Myotis generoko animalia da. Chiropteraren barruko Myotinae azpifamilia eta Vespertilionidae familian sailkatuta dago

Murin d'Alcathoé, Murin d'Alcathoe

Myotis alcathoe, communément appelé le Murin d'Alcathoé ou le Murin d'Alcathoe, est une espèce de chauves-souris de la famille des Vespertilionidae. Appartenant au genre Myotis, il n'est distingué du Murin à moustaches (M. mystacinus) qu'en 2001. Lors de sa description scientifique, ce murin n'est connu que de Grèce et de Hongrie, mais ensuite rapidement identifié dans de nombreux autres pays d'Europe, jusqu'en Espagne à l'Ouest, au Royaume-Uni et en Suède au Nord, et signalé en Azerbaïdjan à l'Est. Avec le Murin à moustaches et le Murin de Brandt (M. brandtii), il constitue le groupe dit des « murins à museau sombre » dont la morphologie cryptique rend l'identification des espèces difficile. L'analyse des séquences ADN a permis de révéler l'existence du Murin d'Alcathoé comme espèce nouvelle et ce murin dispose d'un caryotype distinct des espèces phénotypiquement proches, mais des caractères morphologiques et acoustiques ont également été trouvés pour permettre l'identification de cette chauve-souris. Bien que le Murin d'Alcathoé fût d'abord rapproché du Murin à oreilles échancrées (M. emarginatus), une étude utilisant un plus grand nombre de marqueurs et de taxons montre que ces deux espèces ne sont pas apparentées, sans pouvoir cependant résoudre le placement exact de M. alcathoe au sein des murins d'Eurasie.

Le Murin d'Alcathoé est une petite chauve-souris, avec un avant-bras de 29,7 à 34,6 mm et un poids de 3,5 à 6 grammes. Son pelage est brun, avec des reflets roussâtres au-dessus, mais plus grisâtre chez les jeunes. Le museau est rosâtre, la base de l'oreille et du tragus, qui est court, est claire. Les ailes sont brun sombre et le baculum est court et large. Le Murin d'Alcathoé a un cri d'écholocation très aigu, avec une fréquence montant à 120 kHz en début d'émission et finissant à 43 kHz.

L'espèce vit généralement dans les vieilles forêts à feuilles caduques et à proximité de l'eau, prospectant dans la canopée et au-dessus de l'eau et se nourrissant principalement d'insectes volants. Les gîtes sont situés dans les hautes cavités d'arbres. Bien que l'espèce fréquente les grottes en automne et parfois en hiver, le Murin d'Alcathoé hiberne généralement dans des cavités arboricoles. Plusieurs parasites ont été rapportés chez M. alcathoe. L'Union internationale pour la conservation de la nature ne statue pas sur le niveau de menace de l'espèce, la classant dans la catégorie « données insuffisantes », mais ce murin est considéré comme menacé dans plusieurs régions en raison de sa rareté et de sa vulnérabilité face à la perte de son habitat.

Le Murin d'Alcathoé est la plus petite espèce du genre Myotis en Europe, avec une longueur tête-corps comprise entre 39 et 44 mm[2] et une envergure de près de 20 cm[2],[3]. L'oreille mesure 13 à 14 mm, l'avant-bras 29,7 à 34,6 mm[2], le tibia 13,2 à 15,9 mm, le pied 5,1 à 5,8 mm[4]. La masse corporelle est de 3,5 à 6 grammes[2]. Le pelage dorsal est brunâtre, avec une teinte roussâtre chez les vieux individus, et d'un brun-gris plus pâle sur la face ventrale[4]. Les jeunes individus peuvent être entièrement gris-brun[5],[6],[7]. La fourrure brune et laineuse est un bon critère pour distinguer les Murins d'Alcathoé adultes des autres murins apparentés, mais les jeunes ne peuvent pas être identifiés à coup sûr sur la seule base de leur morphologie[8]. M. alcathoe est similaire en couleur au Murin de Daubenton (Myotis daubentonii) et au Murin à oreilles échancrées (M. emarginatus)[9]. Les poils du dos sont longs de 6 à 8 mm, avec la base sombre et le bout brun, alors que les poils ventraux ne sont qu'à peine plus clairs au bout qu'à la base[5].

La face et la lèvre supérieure sont roussâtres à rosâtres[6] et non brun foncé comme c'est le cas chez le Murin à moustaches (M. mystacinus)[10],[11]. Bien que la face soit en grande partie poilue, le tour des yeux est nu[12]. Les narines sont en forme de cœur et leur partie latérale est bien développée, comme chez le Murin de Brandt (M. brandtii) et non étroite comme chez le Murin à moustaches[13],[6]. Il y a quelques glandes sur le museau, plus évidentes chez les mâles reproducteurs. Les oreilles sont brunes et plus claires à l'intérieur qu'à l'extérieur. Sur le bord externe de l'oreille se trouve une échancrure que la pointe du tragus ne dépasse pas[5] ; chez le Murin à moustaches et le Murin de Brandt, le tragus est plus long et dépasse cette échancrure[11]. L'oreille est blanchâtre à sa base, alors qu'elle est bien plus sombre chez le Murin à moustaches[14],[7],[12]. Les pieds et les pouces sont courts. La petite taille des oreilles, tragus, pieds et pouces distingue le Murin d'Alcathoé du Murin à moustaches et du Murin de Brandt, légèrement plus grands[5], mais ramenés à la taille de l'animal, les pieds sont plus grands que chez le Murin à moustaches[12].

Les ailes sont brunes, mais plus claires que chez le Murin à moustaches[15]. Le plagiopatagium — membrane entre le cinquième doigt de la main et le membre postérieur — est attaché jusqu'au cinquième orteil. La queue ne dépasse que d'un millimètre environ de l'uropatagium — membrane entre les pattes arrière. Le calcar, un éperon cartilagineux soutenant l'uropatagium, est effilé. Avec une épaisseur de 1,3 mm, le pénis est fin[5] et n'a pas l'extrémité renflée (sauf chez un spécimen croate)[10]. Le baculum mesure environ 0,5 mm de long[5], et son aspect court et large le distingue de celui de M. brandtii ainsi que de M. ikonnikovi[15],[5].

Le crâne ressemble à celui du Murin à moustaches et du Murin de Brandt, mais la partie antérieure de la boîte crânienne est plus élevée. La deuxième et troisième prémolaires (la P2 et P3) sont petites et accolées à la canine (C1) à l'avant et contre la quatrième prémolaire (P4) à l'arrière[5]. La canine est moins développée que chez le Murin à moustaches[8]. La quatrième prémolaire a une nette cuspide cingulaire et toutes les molaires supérieures ont un protoconule, quand elles ne sont pas usées. Le Murin à moustaches n'a ni cuspide cingulaire sur la P4 ni protoconule sur les molaires[5], et le Murin de Brandt a une cuspide cingulaire encore mieux développée que chez M. alcathoe, dépassant la P3[11].

Le Murin d'Alcathoé utilise la fréquence d'écholocalisation la plus haute de tous les murins européens. En terrain ouvert, un cri dure en moyenne 2,5 ms, mais il peut s'étaler sur 4 ms. Le cri commence à une fréquence de 120 kHz, qui chute rapidement, puis chute moins vite, puis de nouveau plus rapidement. Le maximum d'amplitude est observé autour de 53 kHz[17]. Le cri se termine à une fréquence de 43-46 kHz, qui est caractéristique de l'espèce[4]. Ce cri aigu pourrait être le résultat d'une adaptation aux milieux denses où chasse le Murin d'Alcathoé[18]. Dans différents contextes, le temps séparant deux cris était de 85 à 66 ms[15].

Comme c'est courant pour les espèces du genre Myotis, le caryotype du Murin d'Alcathoé compte 44 chromosomes, avec un nombre fondamental (nombre de grands bras visibles) de 52. Cependant, une étude de 1987 faisait état que M. alcathoe (alors nommé « Myotis sp. B ») diffère de M. mystacinus et M. brandtii par l'emplacement de l'organisateur nucléolaire[19].

Attrapés, les Murins d'Alcathoé se montrent en main beaucoup plus calmes que leur proches cousins M. mystacinus et M. brandtii[18].

Le Murin d'Alcathoé est une espèce rare avec des exigences écologiques assez élevées[20]. Selon une étude tchèque, son régime alimentaire serait principalement constitué de nématocères, mais aussi de trichoptères, d'araignées, de petits lépidoptères et de névroptères. Ces proies sont pour l'essentiel capturées en vol, mais la présence de proies non volantes suggère que l'espèce peut aussi glaner ses proies sur la végétation[21]. Le Murin d'Alcathoé chasse depuis le bas de la strate forestière jusqu'à la canopée des grands arbres, parfois au-dessus de l'eau[21],[22], et souvent dans la végétation dense[15]. En Saxe-Anhalt, l'espèce chasse au fond des vallées quand les températures dépassent les 10 °C, et recherche de préférence les pentes plus chaudes ou les zones rocailleuses quand il fait plus froid[23]. L'espèce est d'ailleurs facilement capturée dans ces endroits en août, alors que le Murin à moustaches et le Murin de Brandt ont déjà commencé à rejoindre les sites de regroupements automnaux (aussi connus sous le nom d'essaimage ou « swarming ») à la fin du mois de juillet[24],[23].

Trois individus suivis par télémétrie en France, Thuringe et Bade-Wurtemberg se sont, respectivement, déplacés de 800 m, 935 m et 1 440 m autour de leur gîte nocturne, alors que le Murin à moustaches et le Murin de Brandt ont tendance à parcourir de plus longues distances[25]. Un autre suivi télémétrique de plusieurs individus gîtant aux abords de l'Allondon et de la Roulave sur les communes genevoises de Satigny et Dardagny a également établi un rayon de prospection de moins d'un kilomètre et montré que les individus en chasse sont grandement dépendants des corridors végétalisés et des cours d'eau. Les ripisylves de ces rivières comptent une métapopulation d'une soixantaine d'individus au moins, se répartissant en deux colonies changeant quasi quotidiennement de site et exploitant notamment les écorces de chêne décollées[22].

Le Murin d'Alcathoé vit en petits groupes[26] et semble être une espèce typiquement forestière, moins ubiquiste que le Murin à moustaches[22] et la quasi-totalité de ses colonies connues ont été localisées dans des gîtes arboricoles[27]. En Grèce, l'espèce est d'abord connue d'une colonie de mise-bas, comptant trois femelles et deux juvéniles, trouvée dans un platane[28]. D'autres gîtes sont trouvés dans des chênes en Bade-Wurtemberg[26] et en Saxe-Anhalt[18]. Vingt-sept gîtes sont trouvés en République tchèque, tous étant dans des arbres à l'exception d'un situé dans un pilier en béton. Diverses essences sont susceptibles d'accueillir des colonies, notamment le Chêne pédonculé (Quercus robur), mais aussi le Tilleul à petites feuilles (Tilia cordata), le Bouleau verruqueux (Betula pendula) et d'autres espèces[21]. Cette préférence pour les cavités arboricoles n'est pas la plus courante chez les espèces européennes qui exploitent souvent aussi le bâti pour établir leurs colonies[29]. Les gîtes sont souvent haut placés et souvent dans de vieux arbres[21],[20]. En été, les colonies grossissent jusqu'à compter 80 individus, mais en automne les colonies suivies en République tchèque affichent des effectifs moindres[21].

La phénologie de l'espèce reste peu étudiée et mal connue[22]. Le comportement de swarming a d'abord été jugé incertain chez le Murin d'Alcathoé[23],[4], mais est désormais confirmé par des données suisses, slovaques, bulgares et bretonnes et ces rassemblements sont probablement l'occasion de nombreux accouplements[30],[22]. Ils s'étalent de mi-août au début de l'automne[30], ou de fin juillet jusqu'à mi-septembre dans le Sud de la Pologne[11]. Une étude polonaise a suggéré que le Murin d'Alcathoé s'hybride fréquemment avec le Murin à moustaches et le Murin de Brandt, et si ce phénomène était confirmé il pourrait être expliqué par les fortes concentrations de chauves-souris sur les sites d'essaimages et l'abondance relative faible du Murin d'Alcathoé par rapport aux deux autres espèces[11]. Bien que le Murin d'Alcathoé puisse être présent dans les gouffres et grottes durant l'hiver et les visiter régulièrement en période d'essaimage, le milieu hypogée semble rarement exploité pour l'hibernation et ce murin hibernerait essentiellement dans des cavités arboricoles[31],[22]. Un individu observé dans une grotte de Saxe-Anhalt en janvier ne semblait pas en hibernation[23]. Les dates de mise-bas sont mal connues et semblent montrer une certaine hétérogénéité, avec les jeunes déjà nés dès la mi-juin en Grèce, mais les femelles toujours gestantes à cette époque en Allemagne, allaitantes jusqu'au début août et les jeunes volants apparaissant de manière régulière dans la saison[30],[18]. La longévité de l'espèce n'est pas documentée, mais un individu bagué en Angleterre en 2003 (et alors identifié comme Murin à moustaches) a été recapturé en 2009[32].

Plusieurs parasites ont été identifiés chez le Murin d'Alcathoé, comme l'acarien Spinturnix mystacina[34],[35], dont les représentants trouvés chez le Murin d'Alcathoé sont génétiquement très proches de ceux parasitant le Murin à moustaches ou le Murin de Brandt[34]. On recense également la mouche piqueuse Basilia nudior en Thuringe[36], Basilia italica en Slovaquie[35], la tique Ixodes vespertilionis en Roumanie[37] et en Slovaquie[35] et Ixodes ariadnae en Hongrie[33].

Le Murin d'Alcathoé est endémique du Paléarctique occidental[39]. Bien qu'il fût d'abord décrit de Grèce et de Hongrie et supposé être restreint au Sud-Est de l'Europe, il est ensuite rapidement retrouvé très loin de cette zone, en France[12], puis ailleurs en Europe depuis l'Espagne et le Royaume-Uni, jusqu'en Suède et dans la partie européenne de la Turquie[40],[32],[41]. Dans plusieurs pays européens, des recherches ciblées pour permettre sa détection ont été mises en place[24],[21]. Son habitat typique est les forêts matures, décidues et humides, par exemple les forêts alluviales ou dans les ravins boisés[40]. Ces habitats offrent de nombreux arbres sénescents offrant des possibilités de gîtes[29]. En Allemagne, l'espèce vit dans les forêts mixtes décidues[24]. Dans le Sud du continent, l'espèce vit généralement dans les massifs montagneux, mais les facteurs affectant sa répartition sont mal connus. Son aire de répartition semble être proche de celles du Grand Rhinolophe (Rhinolophus ferrumequinum), du Petit Rhinolophe (R. hipposideros) et du Murin à oreilles échancrées (Myotis emarginatus)[40]. Le Murin d'Alcathoé pourrait peut-être encore être découvert dans d'autres pays européens, comme aux Pays-Bas, en Irlande ou en Moldavie[40],[4],[32]. Bien que les signalements soient abondants dans certaines régions, comme en France ou en Hongrie, l'espèce semble rare dans la plus grande partie de son aire de répartition[8].

L'Union internationale pour la conservation de la nature donne également cette espèce présente au Monténégro et possiblement en Bosnie-Herzégovine[77]. Des signalements plus anciens du Murin d'Ikonnikov (M. ikonnikovi) — que l'on sait aujourd'hui être une espèce de l'Est de l'Asie — en Ukraine, Bulgarie et Roumanie pourraient également concerner le Murin d'Alcathoé[28]. En raison de la difficulté d'identification, les murins à museau sombre (M. mystacinus, M. alcathoe et M. brandtii) continuent à être parfois recensés sous ce nom générique qui peut concerner une ou plusieurs de ces espèces ; de tels signalements ont par exemple été faits en Bulgarie[78] et en Belgique[79].

Le Murin à moustaches (Myotis mystacinus) et les espèces proches d'Eurasie, les « murins à museau sombre », sont difficiles à distinguer les uns des autres. Par exemple, le Murin de Brandt (M. brandtii) n'a été reconnu comme distinct de M. mystacinus que dans les années 1970[80]. Des « murins à moustaches » petits et atypiques, sont identifiés en Grèce dès les années 1970 et la biologiste Marianne Volleth identifie la structure chromosomique de ces spécimens comme clairement distincte des autres murins, les traitant sous le nom de « Myotis sp. B » dès 1987[81]. Il faut attendre les avancées des analyses génétiques et l'utilisation du séquençage pour que soit confirmé que ces chauves-souris constituent une espèce distincte, nommée Myotis alcathoe[4]. Il est possible que l'espèce soit passée inaperçue en Allemagne par sous-échantillonnage de son habitat préférentiel et plus généralement parce que les spécimens atypiques de murins à museau sombre ont pu être identifiés comme des M. mystacinus ou M. brandtii anormaux[18]. La description scientifique de l'espèce est publiée en 2001 par les zoologistes allemands Otto von Helversen et Klaus-Gerhard Heller, sur la base de spécimens de Grèce et de Hongrie[82],[83]. Bien que ce murin diffère des espèces proches par la morphologie, c'est l'outil génétique qui autorise l'identification la plus évidente, par les séquences ADN ou par l'analyse caryotypique, l'emplacement de l'organisateur nucléolaire étant distinct des autres espèces apparentées[19]. Pour permettre une identification moléculaire par simple PCR sans besoin de séquençage, plusieurs amorces ont été mises au point pour amplifier des fragments de tailles différentes et diagnostiques de M. mystacinus, M. brandtii ou M. alcathoe [84].

À la description de l'espèce, von Helversen et Heller font le choix de créer un nouveau nom, arguant que l'ensemble des synonymes de Myotis mystacinus alors existants ne peuvent pas concerner le Murin d'Alcathoé, puisque leurs localités types sont toutes situées en Europe de l'Ouest ou centrale, où l'espèce n'est alors pas suspectée[5]. Cependant, les découvertes postérieures de l'espèce jusqu'en Espagne soulèvent la possibilité qu'un ancien nom, ayant priorité, resurgisse pour désigner l'espèce[12],[9]. En outre, le chercheur russe Suren V. Gazaryan a suggéré que le nom Myotis caucasicus Tsytsulina, 2000, originellement proposé pour une sous-espèce de M. mystacinus, puisse s'appliquer à M. alcathoe[53]. Après ré-examination du matériel type, Benda et al. concluent que celui-ci concerne Myotis davidii, une espèce chinoise, à l'exception d'un paratype qui est un Murin à moustaches[54]. Sur la base de nouvelles captures effectuées dans le Grand Caucase russe, ils décrivent en outre la sous-espèce Myotis alcathoe circassicus, génétiquement distincte selon par l'ADN mitochondrial et dont le nom scientifique est une version latinisée de la Tcherkessie où vit ce taxon[54].

Le nom générique Myotis vient du grec qui signifie « oreilles de souris », allusion à la similitude de leurs oreilles avec celles des souris. Le nom vernaculaire murin est un calque du latin murinus se traduisant par « qui se rapporte à la souris »[85].

L'épithète spécifique choisie pour la nouvelle espèce, alcathoe, se réfère à Alcathoé, l'une des trois Minyades. Cette figure de la mythologie grecque est transformée en chauve-souris après avoir refusé les avances du dieu Dionysos dans les gorges d'un cours d'eau, l'habitat du murin en Grèce[82]. Dans la description originale, von Helversen et al. décrivent le personnage comme une nymphe[82], et le nom anglais de « nymph bat » a été par la suite utilisé pour désigner ce murin[6],[86]. Cependant, aucune des sources classiques ne font d'Alcathoé une nymphe, et en parlent au contraire comme d'une princesse, la fille du roi Minyas d'Orchomène. Ainsi, le chiroptérologue tchèque Petr Benda recommande en 2008 de plutôt nommer l'espèce « Alcathoe bat » ou « Alcathoe myotis »[86]. En français, deux orthographes coexistent pour le nommer : Murin d'Alcathoé[22],[87] et Murin d'Alcathoe[88]. L'espèce porte également parfois le nom de « Vespertilion d'Alcathoe »[49], et, avant sa description en 2001, était connue sous le nom de « Murin cantalou » par les chiroptérologues français pour désigner informellement des petits murins à moustaches[12],[59].

Les premières études de l'ADN mitochondrial rapprochent le Murin d'Alcathoé du Murin à oreilles échancrées (M. emarginatus)[13],[89], une espèce du sud de l'Europe, d'Afrique du Nord et sud-ouest de l'Asie. Cette relation est cependant peu soutenue, et d'ailleurs invalidée par une étude ultérieure utilisant un plus grand nombre de marqueurs et de taxons, qui ne parvient cependant pas à déterminer le placement exact de M. alcathoe au sein des murins d'Eurasie[74]. Selon le découpage en sous-genres classiques du genre Myotis, le Murin d'Alcathoé est dans un premier temps rapproché du sous-genre Myotis (Selysius), formant un groupe aux caractères « primitifs » avec les autres « murins dits à moustaches ». Ce découpage est cependant abandonné au fur et à mesure des études génétiques, qui montrent qu'il ne reflète pas les relations de parenté entre les espèces, mais regroupe simplement des écomorphes ayant connu des convergences évolutives[74],[90],[91].

L'analyse des séquences mitochondriales montre que le Murin d'Alcathoé diffère des autres Myotis d'au moins environ 5 % pour l'ARN 12S et 13 % pour ND1[92]. Une étude de 2013 portant sur la phylogénie et la biogéographie des Myotis du monde, incluant près de 90 espèces et combinant marqueurs mitochondriaux et nucléaires, peine également à placer le Murin d'Alcathoé dans la radiation des espèces de ce genre. Il est, comme le Murin des marais (M. dasycneme) et le Murin de Capaccini (M. capaccinii), placé vers la base de la radiation des espèces eurasiatiques sans soutien statistique suffisant, et sa position est donc incertaine[39]. En dépit de leur placement en commun dans le groupe des « murins à museau sombre », le Murin à moustaches (M. mystacinus) et le Murin de Brandt (M. brandtii) sont relativement éloignés du Murin d'Alcathoé : le premier est à rapprocher d'abord du Murin doré (M. aurascens), puis d'un clade asiatique regroupant le Murin d'Ikonnikov (M. ikonnikovi) et M. altarium, et le second appartient à une lignée du Nouveau Monde indépendante de la radiation d'Eurasie. La date de divergence entre clade du Nouveau et de l'Ancien Mondes est estimée aux environs de 18.7 millions d'années, soit le Miocène inférieur[39].

Deux lignées mitochondriales très légèrement divergentes (distance génétique de 1,3-1,4 % sur des marqueurs mitochondriaux classiques) ont été identifiées, qui correspondent probablement à des divergences de populations isolées dans des refuges glaciaires différents de la dernière période glaciaire. La première lignée, appelée groupe « hongrois », a été retrouvée depuis l'Espagne, en France, en Autriche, jusqu'en Hongrie et en Slovaquie et s'est probablement répartie à partir d'un refuge ibérique ; la seconde lignée, appelée groupe « grec », n'est connue que de Grèce et de Slovaquie[8].

Deux études ont utilisé des marqueurs microsatellites sur les trois « murins à museau sombre » européens : la première utilise un échantillonnage de l'Ouest de l'Europe et retrouve trois groupes bien définis, populations pures correspondant aux trois espèces M. alcathoe, M. brandtii et M. mystacinus[32], quand la seconde étude, réalisée en Pologne, suggère une hybridation massive, en particulier pour M. alcathoe, et qui pourrait encore plus compliquer l'identification morphologique chez ces espèces[11].

Le Murin d'Alcathoé reste peu connu, et catégorisé en « données insuffisantes » (DD) sur la liste rouge de l'Union internationale pour la conservation de la nature (UICN)[77]. Il pourrait cependant être menacé en raison de ses préférences écologiques particulièrement restreintes, ayant pour habitat principal les massifs forestiers peu touchés par la sylviculture et associés aux zones humides, et étant peu présent dans les milieux modifiés ou anthropisés[4]. Le Murin d'Alcathoé est notamment susceptible d'être très sensible au recul de son habitat en raison de ses déplacements limités et de sa dépendance à la connectivité des boisements où il chasse[22]. Les arbres sénéscents sont notamment souvent éliminés des ripisylves par les gestionnaires pour éviter qu'ils ne causent des dommages aux ouvrages d'art en cas de crue, alors qu'ils offrent précisément des possibilités de gîtes dans un habitat de choix au Murin d'Alcathoé[87]. L'espèce est également défavorisée par l'enrésinement des boisements, puisqu'elle préfère pour chasser les forêts feuillues ou mixtes, et par les plantations ou modes de gestion n'incluant pas de sous-étage dense[87]. Sa répartition morcelée et ses populations probablement modestes font qu'il est peu à même de coloniser de nouveaux habitats[4]. En plus des menaces liées à la sylviculture (abattage, élagage, gestion forestière des ripisylves), s'ajoutent la mortalité due au trafic routier, enregistrée en plusieurs pays d'Europe[30]. Enfin, en Grèce, deux sites où cette chauve-souris était recensée ont été détruits pour la mise en place de retenues d'eau[28].

L'espèce est protégée par plusieurs mesures nationales et internationales, et notamment listée dans les accords EUROBATS qui protègent tous les chiroptères dans une grande partie des pays d'Europe, mais pour assurer une meilleure protection de l'espèce l'UICN recommande des études plus détaillées de plusieurs aspects de sa biologie, et conseille de mieux faire connaître le Murin d'Alcathoé du public[77]. Le Murin d'Alcathoé est inscrit sur l'annexe II de la convention de Berne (« espèces de faune strictement protégées »), l'annexe II de la convention de Bonn (« espèces migratrices se trouvant dans un état de conservation défavorable et nécessitant l'adoption de mesures de gestion et de conservation appropriées ») et en annexe I de la directive habitats (« espèces animales et végétales d'intérêt communautaire qui nécessitent une protection stricte »)[93]. En Catalogne, l'espèce est listée comme « en danger » en raison de son apparente rareté[57]. Le Murin d'Alcathoé figure sur la liste rouge des vertébrés d'Allemagne comme « en danger critique d'extinction » depuis 2009[94] et l'espèce est listée sous le même statut pour le bassin genevois en 2015[22]. En Hongrie, où l'espèce n'est pas rare dans les habitats adaptés, elle est protégée depuis 2005, mais est menacée par la perte de son habitat et le dérangement dans les grottes[95].

Murin d'Alcathoé, Murin d'Alcathoe

Myotis alcathoe, communément appelé le Murin d'Alcathoé ou le Murin d'Alcathoe, est une espèce de chauves-souris de la famille des Vespertilionidae. Appartenant au genre Myotis, il n'est distingué du Murin à moustaches (M. mystacinus) qu'en 2001. Lors de sa description scientifique, ce murin n'est connu que de Grèce et de Hongrie, mais ensuite rapidement identifié dans de nombreux autres pays d'Europe, jusqu'en Espagne à l'Ouest, au Royaume-Uni et en Suède au Nord, et signalé en Azerbaïdjan à l'Est. Avec le Murin à moustaches et le Murin de Brandt (M. brandtii), il constitue le groupe dit des « murins à museau sombre » dont la morphologie cryptique rend l'identification des espèces difficile. L'analyse des séquences ADN a permis de révéler l'existence du Murin d'Alcathoé comme espèce nouvelle et ce murin dispose d'un caryotype distinct des espèces phénotypiquement proches, mais des caractères morphologiques et acoustiques ont également été trouvés pour permettre l'identification de cette chauve-souris. Bien que le Murin d'Alcathoé fût d'abord rapproché du Murin à oreilles échancrées (M. emarginatus), une étude utilisant un plus grand nombre de marqueurs et de taxons montre que ces deux espèces ne sont pas apparentées, sans pouvoir cependant résoudre le placement exact de M. alcathoe au sein des murins d'Eurasie.

Le Murin d'Alcathoé est une petite chauve-souris, avec un avant-bras de 29,7 à 34,6 mm et un poids de 3,5 à 6 grammes. Son pelage est brun, avec des reflets roussâtres au-dessus, mais plus grisâtre chez les jeunes. Le museau est rosâtre, la base de l'oreille et du tragus, qui est court, est claire. Les ailes sont brun sombre et le baculum est court et large. Le Murin d'Alcathoé a un cri d'écholocation très aigu, avec une fréquence montant à 120 kHz en début d'émission et finissant à 43 kHz.

L'espèce vit généralement dans les vieilles forêts à feuilles caduques et à proximité de l'eau, prospectant dans la canopée et au-dessus de l'eau et se nourrissant principalement d'insectes volants. Les gîtes sont situés dans les hautes cavités d'arbres. Bien que l'espèce fréquente les grottes en automne et parfois en hiver, le Murin d'Alcathoé hiberne généralement dans des cavités arboricoles. Plusieurs parasites ont été rapportés chez M. alcathoe. L'Union internationale pour la conservation de la nature ne statue pas sur le niveau de menace de l'espèce, la classant dans la catégorie « données insuffisantes », mais ce murin est considéré comme menacé dans plusieurs régions en raison de sa rareté et de sa vulnérabilité face à la perte de son habitat.

Il vespertilio di Alcatoe (Myotis alcathoe von Helversen & Heller, 2001) è un pipistrello della famiglia dei Vespertilionidi diffuso in Europa.[1][2]

Il termine specifico fa riferimento alla figura mitologica di Alcatoe, figlia di Minia, che avendo rifiutato le attenzioni di Dioniso fu da questi trasformata in pipistrello.

Pipistrello di piccole dimensioni, con la lunghezza della testa e del corpo tra 39 e 44 mm, la lunghezza dell'avambraccio tra 31 e 33 mm, la lunghezza della coda tra 36 e 37 mm, la lunghezza delle orecchie tra 13 e 14 mm e un peso fino a 6 g.[3]

Le parti dorsali sono bruno-rossastre, mentre le parti ventrali sono brunastre. Il muso è corto, bruno o rosa sporco e ricoperto densamente di peli. Una zona glabra è presente intorno agli occhi. Le orecchie sono corte, strette, con la metà superiore del margine esterno diritta, un incavo all'incirca a metà della sua lunghezza e di color brunastro, più chiare alla base della superficie interna. Il trago è lungo meno della metà del padiglione auricolare. Le membrane alari sono brunastre e attaccate posteriormente alla base dell'alluce. La coda è lunga ed inclusa completamente nell'ampio uropatagio. I piedi sono piccoli, il calcar è sottile e privo di lobi di rinforzo. Il pene è stretto e senza rigonfiamenti in punta. Il cariotipo è 2n=44 Fna=52.

Emette ultrasuoni ad alto ciclo di lavoro con impulsi di breve durata a frequenza modulata iniziale di 130 kHz e finale di 45 kHz.

In estate si rifugia all'interno di alberi cavi e in grotte in gruppi numerosi, mentre in inverno entra in ibernazione probabilmente in ambienti sotterranei.

Si nutre di insetti catturati in prossimità di corsi d'acqua all'interno di piccole vallate.

Femmine che allattavano sono state catturate in Germania durante il mese di giugno.

Questa specie è diffusa in Spagna settentrionale, Francia, Inghilterra settentrionale e meridionale, Svizzera occidentale, Austria sud-orientale, Germania sud-occidentale e centrale, Svezia meridionale, Polonia meridionale, Ucraina occidentale, Repubblica Ceca, Slovacchia, Ungheria settentrionale, Albania meridionale, Montenegro, Romania, Bulgaria, Grecia e Turchia europea. Recentemente in Italia è stato segnalato all'interno del Parco nazionale della Majella, del Parco nazionale d'Abruzzo, Lazio e Molise, nel Parco nazionale del Cilento, Vallo di Diano e Alburni[4] e nel Parco Nazionale dell'Appennino Lucano[5]. Probabilmente è presente anche in Serbia, Belgio e Paesi Bassi.

Vive nelle foreste umide decidue e miste, nelle foreste di palude e ripariali ma anche in zone rurali e ambienti urbani fino a 2.000 metri di altitudine.

La IUCN Red List, considerato che questa specie è stata scoperta recentemente ed è difficile da distinguere dalle altre forme di Myotis, classifica M.alcathoe come specie con dati insufficienti (DD).[1]

Il vespertilio di Alcatoe (Myotis alcathoe von Helversen & Heller, 2001) è un pipistrello della famiglia dei Vespertilionidi diffuso in Europa.

De nimfvleermuis (Myotis alcathoe) is een vleermuis uit het geslacht Myotis die voorkomt in Europa. Deze soort lijkt sterk op de baardvleermuis (M. mystacinus) en Brandts vleermuis (M. brandtii) en is pas in 2001 als een aparte soort herkend. De soort werd oorspronkelijk ontdekt in Griekenland en Hongarije, maar is later ook gevonden in Frankrijk, Spanje, Zwitserland, Slowakije, Bulgarije, het Verenigd Koninkrijk[2] en België[3]. Het is echter nog volledig onduidelijk waar de grenzen van de verspreiding van M. alcathoe liggen.

Ondanks dat de baardvleermuis en Brandts vleermuis bijna niet van M. alcathoe te onderscheiden zijn, zijn ze niet nauw verwant. Op basis van genetische gegevens werd eerst een verwantschap met de ingekorven vleermuis (M. emarginatus) voorgesteld, maar later onderzoek sprak die conclusie tegen; het is nu niet duidelijk aan welke soorten binnen Myotis M. alcathoe verwant is. M. alcathoe komt voornamelijk voor in smalle, beboste valleien, een bedreigde habitat. De soort is genoemd naar Alcathoe, een Griekse nimf die de avances van Dionysus afwees en voor straf in een vleermuis veranderd werd.

Myotis alcathoe verschilt slechts in details van de baardvleermuis en Brandts vleermuis. Beide soorten zijn gemiddeld iets groter; vooral de duimen, voeten en oren van M. alcathoe zijn kleiner. M. alcathoe verschilt ook van de baardvleermuis door de aanwezigheid van enkele kleine knobbels op de kiezen. Brandts vleermuis en Myotis ikonnikovi (een andere sterk gelijkende soort) verschillen van M. alcathoe in de vorm van het penisbot (baculum). Net als de meeste Myotis-soorten bedraagt het karyotype 2n=44, FN=52, maar het verschilt in details van de karyotypes van andere soorten. Voor de echolocatie gebruikt deze soort een frequentie rond de 50 kHz.

Nocek Alkatoe[2] (Myotis alcathoe) – gatunek ssaka z rzędu nietoperzy.

Długość przedramienia 30,5–32,0 mm, masa ciała 3,6–5,0 g. Ciało pokryte krótkim, jedwabistym futrem. Grzbiet ciała brązowy, brzuch jaśniejszy, niemal biały. Krótkie uszy z nożowatymi koziołkami. Pyszczek jasnobrązowy lub wręcz cielisty, znacznie jaśniejszy niż u blisko spokrewnionego nocka wąsatka. Najmniejszy przedstawiciel rodzaju Myotis w Europie.

Występuje na obszarze południowej, zachodniej i środkowej Europy. Opisano go jako nowy dla nauki gatunek z północnej Grecji, następnie stwierdzono go na terenie Węgier, Francji, Szwajcarii, Hiszpanii (Pireneje), Słowacji, Albanii, Bułgarii i Niemiec. W Polsce odnaleziono go dotąd jedynie w Beskidach, Sudetach, Tatrach i na Roztoczu. Stan wiedzy o rozmieszczeniu nocka Alkatoe jest jak dotąd niewystarczający, ponieważ do niedawna nie odróżniano go od, bardzo podobnego morfologicznie, nocka wąsatka, a postęp w tej dziedzinie był możliwy dopiero dzięki badaniom genetycznym, głównie sekwencjonowaniu DNA mitochondrialnego.

Na Półwyspie Bałkańskim związany głównie z wilgotnymi lasami platanowymi w dolinach rzek i wąwozach z niewielkimi potokami, latem wykorzystuje tam kryjówki w dziuplach drzew. W Niemczech występuje w lasach dębowych. W Polsce i na Słowacji odławiano go w sieci przy wejściach do jaskiń.

Na temat ekologii i zachowania tego gatunku dotychczas niewiele wiadomo. Nocek Alkatoe poluje na niewielkie owady, chwytane w locie nad wodą i wśród koron nadrzecznych drzew. Może tworzyć w kryjówkach letnich niewielkie kolonie rozrodcze – w Grecji trzy dorosłe samice i dwoje młodych znaleziono w jednej dziupli platanu, na wysokości 8 m nad ziemią. Emituje krótkie (5 ms) sygnały echolokacyjne, rozpoczynające się na około 120 kHz i kończące na 43-46 kHz.

W Polsce jest objęty ścisłą ochroną gatunkową oraz wymagający ochrony czynnej, dodatkowo obowiązuje zakaz fotografowania, filmowania lub obserwacji, mogących powodować płoszenie lub niepokojenie[3][4].

Nazwa gatunkowa wywodzi się z mitologii greckiej. Alkatoe, córka Minyasa, była nimfą, która odmówiła oddania czci bogu Dionizosowi, za co została przezeń zmieniona w nietoperza.

Netopier alkatoe[2] alebo netopier nymfin[3] (Myotis alcathoe) je druh netopiera z čeľade netopierovité.

Netopier alkatoe bol len nedávno objavený (2001) preto nie je jeho rozšírenie dostatočne známe. Bol zistený len v Európe.[2]

Rozšírenie netopiera alkatoe na Slovensku v letnom období je známe z južnej časti stredného a východného Slovenska.[2]

Zo 429 mapovacích kvadrátov DFS sa celkovo vyskytol v 19 (4,4 % rozlohy Slovenska):[2]

Netopier alkatoe alebo netopier nymfin (Myotis alcathoe) je druh netopiera z čeľade netopierovité.

Nymffladdermus (Myotis alcathoe) är en nyupptäckt fladdermusart i familjen läderlappar (Vespertilionidae).

Alchathoe är hämtat från den grekiska gudasagan, som täljer så här:

Till 2001 uppfattad som mustaschfladdermus, Myotis mystacinus Kuhl 1817. Mycket svår att skilja från denna utom på lätets frekvens samt genetiska data.[1] Några av de få, observerbara skillnaderna är att M. acathoe har kortare ben, fötter och tumme än M. mystacinus. Vidare är de ljusa struphåren mörkare än bukhåren, men om detta är en generell egenskap är för tidigt att säga med tanke på det låga antalet undersökta individer.[3]

Nymffladdermusen är Europas minsta fladdermus:

Medellivslängden för en generation har uppskattats till 5,8 år.

Praktiskt går inspelningar av fladdermössens ljudsignaler till på så sätt att små lådor med automatisk inspelningsanordning för ultraljud sätts upp på några ställen i ett habitat, som bedömts som kvällens troliga jaktplats. Sedan är det bara att vänta, och hoppas att något intressant blir registrerat.

Metoden används inte enbart för nynffladdermus, utan kan användas för spaning efter vilken art som helst.

Fladdermusens läte avges i form av pulssverp med början vid 120 kHz. Amplituden ökar tills svepet nått ca 53 kHz, och avtar sedan mot svepets slutfrekvens 40 kHz. Pulslängden är ca 40 ms. Inga ljud med dessa frekvenser är hörbara för människor.

I vissa inspelningar tycks pulserna komma parvis, d.v.s. två pulser efterföljs av ett lite längre uppehåll, sen följer ytterligare två med kort uppehåll emellan, o.s.v.. Det verkar som om dubbelpulsandet, – "två-takten" – kommer, när djuret närmar sig ett hinder. Räckvidden för signaleringen synes vara omkring 30 m.

De tidsintervall, som anges ovan är medianvärden, som ska förstås med viss variation uppåt och nedåt. Givetvis spelar dopplereffekten roll för det som registrerats vid inspelningarna. Variationerna Individspecifik "röst"?

En del inspelningar är svårbedömda p.g.a. hög brusnivå orsakad av refexioner (ekon) från träd och annat intill flygvägen.

Nymffladdermus lever i fuktig, ej alltför ung, tät lövskog, där den framför allt jagar i bäckraviner och dalgångar.[4] Det förefaller som den även kan uppehålla sig i människopåverkade områden, som trädgårdar och samhällen. Vinterdvalan tros tillbringad i underjordiska utrymmen.[1]

Nymffladdermus hittades första gången i Grekland, och beskrevs 2001. På grund av att arten upptäckts så nyligen är utbredningen dåligt känd, men hittills (2010) har den utöver i Grekland hittats i Spanien, Frankrike, Schweiz, Tyskland, Tjeckien, Slovakien, Ungern, Montenegro, Rumänien, Bulgarien, Polen,[1] Albanien, Belgien, Lettland, Polen, Serbien, Storbritannien, Österrike och den europeiska delen av Turkiet.

Data tyder på att utbredningen kan vara vidare än så, men att den inte är särskilt vanlig någonstans.[4]

Artens läte registrerades Sverige 2010.[5][6]

På grund av svagt forskningsläge är fladdermusen av IUCN globalt klassad som "DD" (Data Deficient, kunskapsbrist). Den miljö som arten tros leva i är emellertid hotad.[1]

Nymffladdermus (Myotis alcathoe) är en nyupptäckt fladdermusart i familjen läderlappar (Vespertilionidae).

Країни проживання: Болгарія, Чеська Республіка, Франція, Німеччина, Греція, Угорщина, Чорногорія, Сербія, Словаччина, Іспанія, Швейцарія.

На Балканському півострові в основному пов'язаний з вологими платановими лісами в долинах річок та ярів з невеликими потоками, ховаючись там влітку в дуплах дерев. У Німеччині мешкає в дубових лісах.

Про екологію і поведінку цього виду поки мало відомо. Myotis alcathoe полює на дрібних комах, що трапляються йому в польоті над водою і кронами дерев.

Найменший з європейських видів цього роду. Довжина передпліччя 30,5-32,0 мм, вага тіла 3,6-5,0 гр; тіло покрите коротким, шовковистим хутром. Задня частина тіла коричнева, черевце світле, майже біле, вуха короткі. Писочок світло-коричневого або навіть тілесного кольору, набагато яскравіше, ніж в тісно пов'язаного виду Myotis mystacinus.

Myotis alcathoe là một loài động vật có vú trong họ Dơi muỗi, bộ Dơi. Loài này được von Helversen & Heller mô tả năm 2001.[3] Chỉ được biết đến từ Hy Lạp và Hungary khi loài này được mô tả lần đầu tiên vào năm 2001, phạm vi phân bố của loài dơi này đã mở rộng sang Tây Ban Nha, Anh, Thụy Điển, và Azerbaijan, trong số các nước khác. Loài này tương tự như loài dơi râu (Myotis mystacinus) và các loài khác và rất khó để phân biệt chúng. Tuy nhiên, lông màu nâu cũng rất đặc biệt và nó rõ ràng là khác nhau trong các nhân vật của các chuỗi nhiễm sắc thể và DNA của nó. Mặc dù một số dữ liệu di truyền cho thấy rằng nó có liên quan tới loài dơi Geoffroy (Myotis emarginatus), phân tích khác không hỗ trợ một mối quan hệ chặt chẽ giữa M. alcathoe và bất kỳ loài khác.

Phương tiện liên quan tới Myotis alcathoe tại Wikimedia Commons

Myotis alcathoe là một loài động vật có vú trong họ Dơi muỗi, bộ Dơi. Loài này được von Helversen & Heller mô tả năm 2001. Chỉ được biết đến từ Hy Lạp và Hungary khi loài này được mô tả lần đầu tiên vào năm 2001, phạm vi phân bố của loài dơi này đã mở rộng sang Tây Ban Nha, Anh, Thụy Điển, và Azerbaijan, trong số các nước khác. Loài này tương tự như loài dơi râu (Myotis mystacinus) và các loài khác và rất khó để phân biệt chúng. Tuy nhiên, lông màu nâu cũng rất đặc biệt và nó rõ ràng là khác nhau trong các nhân vật của các chuỗi nhiễm sắc thể và DNA của nó. Mặc dù một số dữ liệu di truyền cho thấy rằng nó có liên quan tới loài dơi Geoffroy (Myotis emarginatus), phân tích khác không hỗ trợ một mối quan hệ chặt chẽ giữa M. alcathoe và bất kỳ loài khác.

알카토에윗수염박쥐(Myotis alcathoe)는 애기박쥐과 윗수염박쥐속에 속하는 유럽 박쥐이다.[2] 2001년 처음 기재되었을 때는 그리스와 헝가리에서만 알려졌지만, 이후 스페인과 영국, 스웨덴, 아제르바이잔 등 여러 나라에서 확인되었다.

다음은 윗수염박쥐속의 계통 분류이다.[3]

윗수염박쥐속 구대륙 분류군 clade III clade II술라웨시윗수염박쥐 (M. m. browni)

clade IV 에티오피아신대륙 분류군