fi

nimet breadcrumb-navigoinnissa

Penicillium digitatum (/ˌpɛnɪˈsɪliəm ˌdɪdʒɪˈteɪtəm/) is a mesophilic fungus found in the soil of citrus-producing areas.[1][2][3] It is a major source of post-harvest decay in fruits and is responsible for the widespread post-harvest disease in Citrus fruit known as green rot or green mould.[1][4][5] In nature, this necrotrophic wound pathogen grows in filaments and reproduces asexually through the production of conidiophores and conidia.[1][6][7] However, P. digitatum can also be cultivated in the laboratory setting.[1] Alongside its pathogenic life cycle, P. digitatum is also involved in other human, animal and plant interactions and is currently being used in the production of immunologically based mycological detection assays for the food industry.[1][8][9]

Penicillium digitatum is a species within the Ascomycota division of Fungi. The genus name Penicillium comes from the word "penicillus" which means brush, referring to the branching appearance of the asexual reproductive structures found within this genus.[10] As a species, P. digitatum was first noted as Aspergillus digitatus by Christiaan Hendrik Persoon in 1794 who later adopted the name Monilia digitata in Synopsis methodica fungorum (1801).[11] The synonym M. digitata can also be found in the writings of Elias Magnus Fries in Systema Mycologicum.[12] However, the current binomial name comes from the writings of Pier Andrea Saccardo, particularly Fungi italici autographie delineati et colorati (1881).[12]

In nature, P. digitatum adopts a filamentous vegetative growth form, producing narrow, septate hyphae.[13] The hyphal cells are haploid, although individual hyphal compartments may contain many genetically identical nuclei.[14] During the reproductive stages of its life cycle, P. digitatum reproduces asexually via the production of asexual spores or conidia.[13] Conidia are borne on a stalk called a conidiophore that can emerge either from a piece of aerial hyphae or from a soil-embedded network of hyphae.[1][13] The conidiophore is usually an asymmetrical, delicate structure with smooth, thin walls.[1][2] Sizes can range from 70–150 μm in length.[1] During development, the conidiophore can branch into three rami to produce a terverticillate structure although biverticillate and other irregular structures are often observed.[1] At the end of each rami, another set of branches called metulae are found. The number of metulae varies with their sizes ranging from 15–30 × 4–6 μm.[2] At the distal end of each metula, conidium-bearing structures called phialides form. Phialides can range in shape from flask-shaped to cylindrical and can be 10–20 μm long.[1] The conidia produced, in turn, are smooth with a shape that can range from spherical to cylindrical although an oval shape is frequently seen.[1][2] They are 6–15 μm long and are produced in chains, with the youngest at the base of each chain.[1][13] Each conidium is haploid and bears only one nucleus.[14] Sexual reproduction in P. digitatum has not been observed.[14]

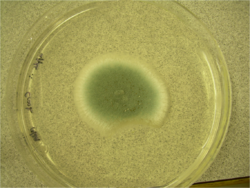

Penicillium digitatum can also grow on a variety of laboratory media. On Czapek Yeast Extract Agar medium at 25 °C, white colonies grow in a plane, attaining a velvety to deeply floccose texture with colony sizes that are 33–35 mm in diameter.[1] On this medium, olive conidia are produced.[1] The reverse of the plate can be pale or slightly tinted brown.[1] On Malt Extract Agar medium at 25 °C, growth is rapid yet rare, forming a velvety surface.[1][2] At first, colonies are yellow-green but ultimately turn olive due to conidial production.[2] Colony diameter can range in size from 35 mm to 70 mm.[1] The reverse of the plate is similar to that observed for Czapek Yeast Extract Agar medium.[1] On 25% Glycerol Nitrate Agar at 25 °C, colony growth is planar yet develops into a think gel with colony size diameter ranging from 6–12 mm.[1] The back of the plate is described as pale or olive.[1] At 5 °C, 25% Glycerol Nitrate Agar supports germination and a colonial growth of up to 3 mm in diameter.[1] This species fails to grow at 37 °C.[1] On Creatine Sucrose Agar at 25 °C, colony size diameter ranges from 4 to 10 mm.[1] Growth is restricted and medium pH remains around 7.[1] No change on the back of the plate is noted.[1] Growth on media containing orange fruit pieces for seven days at room temperature results in fruit decay accompanied by a characteristic odour.[1] After 14 days at room temperature, the reverse is colourless to light brown.[1]

Penicillium digitatum is found in the soil of areas cultivating citrus fruit, predominating in high temperature regions.[1][2] In nature, it is often found alongside the fruits it infects, making species within the genus Citrus its main ecosystem.[1][2] It is only within these species that P. digitatum can complete its life cycle as a necrotroph.[6][14] However, P. digitatum has also been isolated from other food sources.[1] These include hazelnuts, pistachio nuts, kola nuts, black olives, rice, maize and meats.[1] Low levels have also been noted in Southeast Asian peanuts, soybeans and sorghum.[1]

Penicillium digitatum is a mesophilic fungus, growing from 6–7 °C (43–45 °F) to a maximum of 37 °C (99 °F), with an optimal growth temperature at 24 °C (75 °F).[1][3] With respect to water activity, P. digitatum has a relatively low tolerance for osmotic stress. The minimum water activity required for growth at 25 °C (77 °F) is 0.90, at 37 °C (99 °F) is 0.95 and at 5 °C (41 °F) is 0.99.[1] Germination does not occur at a water activity of 0.87.[1] In terms of chemicals that influence fungal growth, the minimum growth inhibitory concentration of sorbic acid is 0.02–0.025% at a pH of 4.7 and 0.06–0.08% at a pH of 5.5.[1] Thiamine, on the other hand, has been observed to accelerate fungal growth with the effect being co-metabolically enhanced in the presence of tyrosine, casein or zinc metal.[8] In terms of carbon nutrition, maltose, acetic acid, oxalic acid and tartaric acid support little, if any, growth.[8] However, glucose, fructose, sucrose, galactose, citric acid and malic acid all maintain fungal growth.[8]

Production of ethylene via the citric acid cycle has been observed in static cultures and is suggested to be connected to mycelial development.[15] Addition of methionine inhibits such cultures but can be utilized for the production of ethylene following a lag phase in shake cultures.[15] The production observed in shake cultures can be inhibited by actinomycin D and cycloheximide and modulated by inorganic phosphate.[15] In addition, aminoethoxyvinyl glycine and methoxyvinyl glycine have been shown to inhibit both shake and static cultures.[15] Production of mycotoxins or secondary metabolites by P. digitatum has not been observed although this species has been shown to be toxic to both shrimp and chicken embryos.[1]

With respect to fungicidal tolerance, there are known strains of P. digitatum resistant to various commonly used fungicides.[1] Reports have been made concerning fungicides thiabendazole, benomyl, imazalil, sodium-o-phenylphenate as well as fungistatic agent, biphenyl, with no prior treatment required in the case of biphenyl.[1][2] The mechanism of P. digitatum resistance to imazalil is suggested to lie in the over-expression of the sterol 14α-demethylase (CYP51) protein caused by a 199 base-pair insertion into the promoter region of the CYP51 gene and/or by duplications of the CYP51 gene.[16]

Species within the genus Penicillium do not generally cause disease in humans.[17] However, being one of the most common producers of indoor moulds, certain species can become pathogenic upon long-term exposure as well as for individuals who are immunocompromised or hyper-sensitized to certain parts of the fungus.[17][18] Spores, proteolytic enzymes and glycoproteins are amongst the components commonly reported as allergens in humans and animal models.[18] Within this context, members of Penicillium have been associated with a variety of immunological manifestations such as Type 1 allergic responses, hypersensitivity pneumonitis (Type 3 responses), and immediate and delayed asthma.[18]

With respect to P. digitatum, this species is known to cause generalized mycosis in humans, although the incidence of such events are very low.[17] Various studies have also noted a presence of circulating antibodies to the extracellular polysaccharide of P. digitatum in both human and rabbit sera.[19] This presence is suggested to be due to the intake of contaminated fruits and/or breathing air contaminated with extracellular polysaccharide.[19] In terms of allergy testing, P. digitatum is present in various clinical allergy test formulations, testing for allergy to moulds.[20] There has been one case report identifying P. digitatum as the cause of a fatal case of pneumonia through molecular methods.[17]

Post-harvest decays are a main source of fruit loss following harvesting, with the most common source of Citrus fruit decay being infections caused by P. digitatum and P. italicum.[1][4] [5] Penicillium digitatum is responsible for 90% of citrus fruits lost to infection after harvesting and considered the largest cause of post-harvest diseases occurring in Californian citrus fruits.[21] Its widespread impact relates to the post-harvest disease it causes in citrus fruits known as green rot or mould.[7] As a wound pathogen, the disease cycle begins when P. digitatum conidia germinate with release of water and nutrients from the site of injury on the fruit surface.[7][22] After infection at 24 °C, rapid growth ensues with active infection taking place within 48 hours and initial symptom onset occurring within 3 days.[3][7] As temperature at time of infection decreases, the delay of initial symptom onset increases.[3] Initial symptoms include a moist depression on the surface which expands as white mycelium colonizes much of its surface.[3] The centre of the mycelial mass eventually turns olive as conidial production begins.[2][3] Near the end of the disease cycle, the fruit eventually decreases in size and develops into an empty, dry shell.[2] This end result is commonly used to distinguish P. digitatum infections from those of P. italicum which produce a blue-green mould and ultimately render the fruit slimy.[2]

Infection with green mould at 25 °C (77 °F) can last 3 to 5 days with the rate of conidial production per infected fruit being as high as 1–2 billion conidia.[22] Annual infections can occur anywhere from December to June and can take place throughout any point during and following harvesting.[7] Transmission can occur mechanically or via conidial dispersal in water or air to fruit surfaces.[3][7] Conidia often reside within soil but can also be found in the air of contaminated storage spaces.[3] Being a wound pathogen, fruit injuries are required for successful fruit infections, with much of these injuries occurring due to improper handling throughout the harvesting process.[3] Injuries can also be caused by other events such as frost and insect bites, and can be as minor as damage to fruit skin oil glands.[3][7] Fallen fruit can also be susceptible to P. digitatum infections as has been noted in Israel, where P. digitatum infects fallen fruit more than P. italicum.[2]

Pathogenicity of P. digitatum is suggested to rely on the acidification of the infected fruit.[1][23] During fruit decay, this species has been observed to make citric acid and gluconic acid and sequester ammonium ions into its cytoplasm.[23] The low pH may aid in the regulation of various gene-encoded pathogenic factors such as polygalactouronases.[1][23] In addition, P. digitatum has also been observed to modify plant defense mechanisms, such as phenylalanine ammonia lyase activity, in the citrus fruits it infects.[23]

Modifications to the disease cycle of P. digitatum have been induced experimentally. For example, P. digitatum has been observed to cause infection in unwounded fruits through mechanical transmission although a higher infection dose was required in such instances.[13] Apples have also been infected to a limited extent.[9] Besides its pathogenic interactions, P. digitatum has also been implicated in naturally accelerating the ripening of green fruits and causing epinastic responses in various plants such as potato, tomato and sunflowers.[8]

Control of green mould initially relies on the proper handling of fruit before, during and after harvesting.[2][7] Spores can be reduced by removing fallen fruit.[1][7] Risk of injury can be decreased in a variety of ways including, storing fruit in high humidity and low temperature conditions, and harvesting before irrigation or rainfall in order to minimize fruit susceptibility to peel damage.[7] Degreening practices can also be conducted at humidities above 92% in order to heal injuries.[7]

Chemical control in the form of fungicides is also commonly used.[1] Examples include imazalil, thiabendazole and biphenyl, all of which suppress the reproductive cycle of P. digitatum.[3] Post-harvest chemical treatment usually consists of washes conducted at 40–50 °C (104–122 °F), containing detergents, weak alkalines and fungicides.[1] Californian packinghouses typically use a fungicide cocktail containing sodium o-phenylphenate, imazalil and thiabendazole.[22] In Australia, guazatine is commonly used although this treatment is restricted to the domestic market.[1] In terms of the export market, Generally recognized as safe (GRAS) substances are currently being explored as alternatives.[1] GRAS substances such as sodium bicarbonate, sodium carbonate and ethanol, have displayed an ability to control P. digitatum by decreasing germination rate.[24]

Resistance to common fungicides is currently combated through the use of other chemicals. For example, sodium o-phenylphenate-resistant strains are dealt with via formaldehyde fumigation while imazalil-resistant strains are controlled through the use of pyrimethanil, a fungicide also approved for fighting strains resistant to other fungicides.[1] As fungicide resistance increases globally, other measures of control are being considered including that of biocontrol. Effective biocontrol agents include bacteria such as Bacillus subtilis, Pseudomonas cepacia and Pseudomonas syringae as well as fungi such as Debaryomyces hansenii and Candida guilliermondii.[1] In Clementines and Valencia oranges, Candida oleophila, Pichia anomala and Candida famata have been shown to reduce disease.[1][24] Despite the ability of various biocontrol agents to exhibit antagonistic activity, biocontrol has not been shown to provide complete control over P.digitatum and is therefore commonly used in conjunction with another measure of control.[24] Alternative measures of control include essential oils such as Syzygium aromaticum and Lippia javanica, ultraviolet light, gamma-irradiation,[5] X-rays curing, vapour heat, and cell-penetrating anti-fungal peptides.[1][25][26]

Penicillium digitatum can be identified in the laboratory using a variety of methods. Typically, strains are grown for one week on three chemically defined media under varying temperature conditions.[1] The media used are Czapek Yeast Extract Agar (at 5, 25 and 37 °C), Malt Extract Agar (at 25 °C) and 25% Glycerol Nitrate Agar (at 25 °C).[1] The resulting colonial morphology on these media (described in Growth and Morphology above) allows for identification of P. digitatum. Closely related species in the genus Pencillium can be resolved through this approach by using Creatine Sucrose Neutral Agar.[1] Molecular methods can also aid with identification.[1] The genomes of many species belonging to the genus Penicillium remain to be sequenced however, limiting the applicability of such methods.[1] Lastly, P. digitatum can also be distinguished macroscopically by the production of yellow-green to olive conidia and microscopically, by the presence of large philades and conidia.[1]

Penicillium digitatum is used as a biological tool during the commercial production of latex agglutination kits.[1] Latex agglutination detects Aspergillus and Penicillium species in foods by attaching antibodies specific for the extracellular polysaccharide of P. digitatum to 0.8 μm latex beads.[1] This method has been successful in detecting contamination of grains and processed foods at a limit of detection of 5–10 ng/mL of antigen.[1] In comparison to other detection assays, the latex agglutination assay exceeds the detection limit of the Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and is as effective in detecting Aspergillus and Pencillium species as the ergosterol production assay.[1] However, the latter displays an increased ability to detect Fusarium species when compared to the latex agglutination assay.[1]

Penicillium digitatum (/ˌpɛnɪˈsɪliəm ˌdɪdʒɪˈteɪtəm/) is a mesophilic fungus found in the soil of citrus-producing areas. It is a major source of post-harvest decay in fruits and is responsible for the widespread post-harvest disease in Citrus fruit known as green rot or green mould. In nature, this necrotrophic wound pathogen grows in filaments and reproduces asexually through the production of conidiophores and conidia. However, P. digitatum can also be cultivated in the laboratory setting. Alongside its pathogenic life cycle, P. digitatum is also involved in other human, animal and plant interactions and is currently being used in the production of immunologically based mycological detection assays for the food industry.

Penicillium digitatum es un hongo mesófilo del género Penicillium encontrado en el suelo de las zonas productoras de los cítricos.[1][2][3] Es la mayor fuente de decaimiento de las frutas en épocas de post-cosecha y es el responsable de las enfermedades de los cítricos conocida como putrefacción verde.[1][4] En la naturaleza, este hongo necrotrófico patógeno hiere a la superficie de los cítricos creciendo en forma de filamentos y se reproduce asexualmente a través de la producción de conidias.[1][5][6] Sin embargo, P. digitatum también se puede cultivar en condiciones ambientales en el laboratorio.[1] Junto a su ciclo de vida patógeno, P. digitatum también participa en otras interacciones humanas, animales y vegetales y se está utilizando actualmente en la producción de afecciones micológicas basados en ensayos inmunológicos de detección para la industria alimentaria.[1][7][8]

El hongo Penicillium digitatum se encuentra en el suelo de áreas donde se cultivan frutos cítricos, que predominan en regiones de altas temperaturas.[1][2] En la naturaleza, frecuentemente se encuentran en las diferentes especies de frutos cítricos infectados por la parte interna donde está su ecosistema principal.[1][2]

Penicillium digitatum es un hongo mesófilo del género Penicillium encontrado en el suelo de las zonas productoras de los cítricos. Es la mayor fuente de decaimiento de las frutas en épocas de post-cosecha y es el responsable de las enfermedades de los cítricos conocida como putrefacción verde. En la naturaleza, este hongo necrotrófico patógeno hiere a la superficie de los cítricos creciendo en forma de filamentos y se reproduce asexualmente a través de la producción de conidias. Sin embargo, P. digitatum también se puede cultivar en condiciones ambientales en el laboratorio. Junto a su ciclo de vida patógeno, P. digitatum también participa en otras interacciones humanas, animales y vegetales y se está utilizando actualmente en la producción de afecciones micológicas basados en ensayos inmunológicos de detección para la industria alimentaria.

Penicillium digitatum est une espèce de champignons microscopiques du genre Penicillium.

C'est un agent de pourriture des fruits, surtout les agrumes. Il est connu comme étant la pourriture verte des oranges et citrons et est très fréquent.

Penicillium digitatum (Pers.) Sacc., 1881 è un fungo, appartenente alla famiglia delle Trichocomaceae, noto per essere un patogeno degli agrumi causandone l'imputridimento con formazione di muffa verde.[1] Infetta le ferite della buccia dei frutti agendo da parassita necrotrofo, cresce con ife filamentose e si riproduce asessualmente tramite la produzione di conidiofori.[2] L'odore caratteristico che si genera durante la marcescenza è dovuto alla formazione di metaboliti quali il limonene, valencene, etilene, etanolo, acetato di etile e di metile.[1]

In natura, P. digitatum adotta una forma di crescita vegetativa filamentosa, producendo ife strette e settate. Durante gli stadi riproduttivi del suo ciclo vitale, P. digitatum si riproduce asessualmente attraverso la produzione di spore asessuali o conidi. I conidi si trovano su conidiofori che possiedono solitamente una delicata struttura asimmetrica, con pareti sottili e lunghezza compresa tra i 70-150 µm.[3] Durante lo sviluppo, il conidioforo si ramifica in tre parti formando una struttura terverticillata, sebbene si osservino pure strutture biverticellate e altre strutture irregolari. All'estremità di ciascuna ramificazione, è presente un altro insieme di rami chiamati metule. Le fialidi sono poste sull'estremità distale di ciascuna metula e possiedono forma variabile da quella classica "a fiala" fino a forme cilindriche, con lunghezza compresa tra i 10-20 µm.[3] I conidi, di forma sferica, ovale, o cilindrica, sono lunghi 6-15 µm; ciascun conidio è aploide e contiene un solo nucleo.

Penicillium digitatum è una specie ubiquitaria che preferisce i climi più caldi. In natura è spesso associata ai frutti che infetta, rendendo il genere Citrus il suo principale ecosistema.[3] È solamente all'interno di questo genere che P. digitatum può completare il proprio ciclo vitale agendo da necrotrofico.[2] Tuttavia, P. digitatum è stato isolato anche da altre fonti alimentari, incluse nocciole, pistacchi, noci di cola, olive nere, riso, mais e carni. Bassi livelli sono stati riscontrati anche nelle arachidi, soia e sorgo provenienti dal sudest asiatico.[3]

Penicillium digitatum è un fungo mesofilo che cresce a una temperatura compresa tra i 6–7 °C e i 37 °C, con una temperatura ottimale di 24 °C.[3][4] Possiede una tolleranza osmotica relativamente bassa, richiedendo a 25 °C un'attività dell'acqua minima pari 0,90 per la crescita.[3] Tra i composti chimici in grado di influenzarne la crescita, l'acido sorbico esercita un'azione inibitoria a concentrazioni dello 0,02-0,025% a pH 4,7 e dello 0,06-0,08% a pH 5,5.[3] D'altra parte la tiamina accelera la crescita del fungo, e la sua concentrazione viene aumentata metabolicamente in presenza di tirosina, caseina o zinco metallico.[5] In termini di substrati nutritivi, maltosio, acido acetico, acido ossalico e acido tartarico ne supportano scarsamente la crescita.[5] Invece, glucosio, fruttosio, saccarosio, galattosio, acido citrico e acido malico sostengono tutti la crescita del fungo.[5]

La produzione di etilene attraverso il ciclo di Krebs è stata osservata in colture statiche e si pensa che sia collegata allo sviluppo del micelio.[6] L'aggiunta di metionina inibisce tali colture, ma può essere utilizzata per la produzione di etilene dopo la fase di latenza della crescita in colture dinamiche.[6] La produzione osservata in quest'ultimo genere di colture può essere inibita dall'actinomicina D e dalla cicloesimide, e modulata da fosfato inorganico.[6] Inoltre, l'amminoetossivinil glicina e la metossivinil glicina si sono mostrate in grado di inibire sia le colture dinamiche sia quelle statiche.[6] Non è stata osservata alcuna produzione di micotossine o metaboliti secondari da parte di P. digitatum, sebbene questa specie si è dimostrata essere tossica per i gamberi e gli embrioni di pollo.[3]

P. digitatum, insieme a P. italicum, è una delle principali cause del deterioramento degli agrumi che dopo l'infezione diventano marci con la formazione di una tipica muffa verde. Si ritiene che sia responsabile del 90% del deterioramento delle arance durante il periodo di immagazzinamento, causando serie perdite economiche.[7] Il suo ciclo patogeno comincia con la germinazione dei conidi all'interno di una ferita, con il rilascio di acqua e nutrienti sulla superficie del frutto.[8] Dopo l'infezione, a 24 °C ne consegue la rapida crescita del fungo e i sintomi iniziali cominciano ad apparire entro tre giorni.[4] Se la temperatura diminuisce durante l'infezione in atto, si osserva un ritardo dell'insorgenza dei sintomi iniziali.[4] I sintomi iniziali includono una depressione umida sulla superficie che si espande quando il micelio bianco colonizza la maggior parte della superficie del frutto; il centro della massa del micelio diventa infine color verde oliva quando inizia la produzione dei conidi. In prossimità della fine del ciclo della malattia, il frutto diminuisce di dimensione e diventa un guscio secco e vuoto. Questo risultato finale costituisce un tratto distintivo nei confronti delle infezioni causate da P. italicum che produce una muffa blu-verde e fa diventare il frutto viscido.[9]

L'infezione con muffa verde a 25 °C può durare da tre a cinque giorni con livelli di produzione di conidi nei frutti infetti che possono raggiungere 1-2 miliardi di unità.[8] Le infezioni annuali possono verificarsi ovunque dal mese di dicembre a quello di giugno e possono avvenire in qualsiasi momento nel corso della raccolta o durante le fasi successive. La trasmissione può verificarsi meccanicamente o attraverso la dispersione dei conidi che raggiungono così la superficie dei frutti.[4] I conidi spesso risiedono all'interno del suolo ma possono essere presenti anche nell'aria dei luoghi di immagazzinamento contaminati.[4] Essendo un patogeno che agisce penetrando nelle ferite, è necessario che si verifichino delle lesioni all'epidermide di un frutto affinché avvenga l'infezione, e la maggior parte di tali lesioni sono dovute all'impropria manipolazione durante il processo di raccolta.[4] Le lesioni possono essere causate anche da altri eventi come il gelo e i morsi di insetti, e possono essere di entità minore come i danni provocati alle ghiandole oleifere della buccia dei frutti.[4] Anche i frutti caduti al suolo sono suscettibili all'infezione da parte di P. digitatum come è stato notato in Israele, dove P. digitatum infetta i frutti caduti più di P. italicum.[9]

Si ritiene che la patogenicità di P. digitatum sia basata sull'acidificazione del frutto infettato.[10] Durante la marcescenza del frutto, il fungo produce acido citrico e acido gluconico e sequestra gli ioni ammonio all'interno del suo citoplasma.[10] Il basso pH può supportare la regolazione di vari fattori patogeni codificati geneticamente come le poligalattouronasi.[10] Inoltre, P. digitatum è in grado di modificare i meccanismi di difesa delle piante, come l'attività della fenilalanina ammoniaca-liasi, negli agrumi che infetta.[10]

Sperimentalmente P. digitatum si è dimostrato essere in grado di infettare frutti non lesionati attraverso la trasmissione meccanica, sebbene in questo caso sia richiesta una dose infettiva maggiore. Anche le mele sono state infettate in modo limitato. Oltre alle sue interazioni patogene, P. digitatum è stato implicato anche nel naturale acceleramento della maturazione dei frutti verdi e come causa della risposta epinastica in varie piante come la patata, il pomodoro e il girasole.[5]

Il controllo della muffa verde si basa inizialmente sul corretto maneggio dei frutti prima, durante e dopo la raccolta.[9] Le spore possono essere ridotte rimuovendo i frutti marci.[3][11] Il rischio di provocare lesioni all'epidermide può essere ridotto in diversi modi, inclusa la conservazione in condizioni di elevata umidità e bassa temperatura, e la raccolta prima dell'irrigazione o della pioggia per minimizzare la possibilità di danni alla buccia.[11] Possono essere condotte anche pratiche di sverdimento a livelli di umidità superiori al 92% per guarire eventuali ferite.[11]

I fungicidi sono comunemente utilizzati per attuare il controllo chimico.[3] Esempi includono l'imazalil, il tiabendazolo, il benomil e il bifenile, i quali sopprimono tutti il ciclo riproduttivo di P. digitatum.[4] Il trattamento chimico dopo la raccolta consiste solitamente nel lavaggio, condotto a una temperatura compresa tra i 40–50 °C, con detergenti, basi deboli e fungicidi.[12] Sostanze ritenute generalmente sicure come il bicarbonato di sodio, il carbonato di sodio e l'etanolo hanno mostrato di essere in grado di controllare la crescita di P. digitatum diminuendone la velocità di germinazione.[13]

Ceppi resistenti ai comuni fungicidi richiedono l'utilizzo di prodotti alternativi come la formaldeide e il pirimetanil. In alternativa al trattamento chimico è possibile ricorrere ad altre misure che includono il biocontrollo con batteri come Bacillus subtilis, Pseudomonas cepacia e Pseudomonas syringae, così come con lieviti quali Debaryomyces hansenii e Candida guilliermondii.[12] Candida oleophila, Pichia anomala e Candida famata sono in grado di ridurre la malattia nelle clementine e nelle arance Valencia.[12][13] Nonostante l'abilità di vari agenti di biocontrollo di mostrare attività antagonistica, il biocontrollo non fornisce un controllo completo su P. digitatum ed è perciò usato comunemente insieme a un'altra misura di prevenzione.[13] Misure alternative di controllo includono l'uso di oli essenziali come quelli ricavati da Syzygium aromaticum e Lippia javanica, l'irradiazione con luce ultravioletta, raggi gamma,[14] raggi X, la somministrazione di calore tramite vapore, e peptidi antifungini che penetrano all'interno della cellula.[3][15][16]

P. digitatum causa molto raramente micosi sistemiche negli esseri umani.[17] Vari studi hanno dimostrato la presenza di anticorpi circolanti verso il polisaccaride extracellulare di P. digitatum nel siero umano e di coniglio.[18] Questa presenza si ritiene sia dovuta al consumo di frutti contaminati e/o alla respirazione di aria contaminata con il polisaccaride extracellulare.[18] P. digitatum è potenzialmente in grado di generare una reazione allergica ed esiste in commercio un suo estratto utilizzato nella diagnosi clinica.[19] È stato riportato un caso di polmonite fatale dovuta a P. digitatum, resistente ad antimicotici, in un paziente anziano già affetto da enfisema polmonare, denutrito e probabilmente immunocompromesso.[17]

Penicillium digitatum (Pers.) Sacc., 1881 è un fungo, appartenente alla famiglia delle Trichocomaceae, noto per essere un patogeno degli agrumi causandone l'imputridimento con formazione di muffa verde. Infetta le ferite della buccia dei frutti agendo da parassita necrotrofo, cresce con ife filamentose e si riproduce asessualmente tramite la produzione di conidiofori. L'odore caratteristico che si genera durante la marcescenza è dovuto alla formazione di metaboliti quali il limonene, valencene, etilene, etanolo, acetato di etile e di metile.

Penicillium digitatum (synoniemen: Monilia digitata Pers. en Oidium fasciculatum) staat bekend, naast Penicillium italicum en Penicillium ulaiense, als een bederf veroorzakende schimmel in citrusvruchten (bijvoorbeeld sinaasappels en mandarijnen). Deze plekken zijn vaak zichtbaar als olijfgroene plekken op de citrusvrucht. De schimmel komt vaak samen voor met Penicillium italicum. Penicillium italicum vormt een blauwgroene schimmellaag en de vrucht wordt uiteindelijk slijmerig, terwijl bij een aantasting van Penicillium digitatum er een olijfgroene schimmellaag gevormd wordt en alleen een droog omhulsel overblijft.[1] Penicillium digitatum komt vaker voor dan Penicillium italicum.

De groenwitte tot lichtgroene, gladde, dunwandige, ellipsvormige tot cilindrische conidia zijn 4,0 - 10,3 × 3,2 - 7,1 μm groot.[2]

Penicillium digitatum (synoniemen: Monilia digitata Pers. en Oidium fasciculatum) staat bekend, naast Penicillium italicum en Penicillium ulaiense, als een bederf veroorzakende schimmel in citrusvruchten (bijvoorbeeld sinaasappels en mandarijnen). Deze plekken zijn vaak zichtbaar als olijfgroene plekken op de citrusvrucht. De schimmel komt vaak samen voor met Penicillium italicum. Penicillium italicum vormt een blauwgroene schimmellaag en de vrucht wordt uiteindelijk slijmerig, terwijl bij een aantasting van Penicillium digitatum er een olijfgroene schimmellaag gevormd wordt en alleen een droog omhulsel overblijft. Penicillium digitatum komt vaker voor dan Penicillium italicum.

De groenwitte tot lichtgroene, gladde, dunwandige, ellipsvormige tot cilindrische conidia zijn 4,0 - 10,3 × 3,2 - 7,1 μm groot.

Penicillium digitatum je grzib[3], co go nojprzōd ôpisoł Christiaan Hendrik Persoon, a terŏźnõ nazwã doł mu Pier Andrea Saccardo 1881. Penicillium digitatum nŏleży do zorty Penicillium i familije Trichocomaceae.[4][5] Żŏdne podgatōnki niy sōm wymianowane we Catalogue of Life.[4]

Penicillium digitatum je grzib, co go nojprzōd ôpisoł Christiaan Hendrik Persoon, a terŏźnõ nazwã doł mu Pier Andrea Saccardo 1881. Penicillium digitatum nŏleży do zorty Penicillium i familije Trichocomaceae. Żŏdne podgatōnki niy sōm wymianowane we Catalogue of Life.

Penicillium digitatum là một loài nấm hoạt sinh trong chi Penicillium, họ Trichocomaceae. Loài này hiện diện ở khu vực đất trồng cây chi Cam quýt.[1]

[2] [3] Đây là một nguồn chính của sụ thối quả sau thu hoạch và chịu trách nhiệm cho bệnh sau thu hoạch lan rộng ở trái cây có múi được gọi là thối xanh hoặc mốc xanh. Trong tự nhiên, mầm bệnh vết thương hoại tử này phát triển thành sợi và sinh sản vô tính thông qua việc sản xuất các conidiophores. Tuy nhiên, P. Digitatum cũng có thể được nuôi cấy trong môi trường phòng thí nghiệm. Bên cạnh vòng đời gây bệnh, P. Digitatum cũng tham gia vào các tương tác giữa người, động vật và thực vật khác và hiện đang được sử dụng trong sản xuất các xét nghiệm phát hiện nấm dựa trên miễn dịch cho ngành công nghiệp thực phẩm.

Penicillium digitatum là một loài nấm hoạt sinh trong chi Penicillium, họ Trichocomaceae. Loài này hiện diện ở khu vực đất trồng cây chi Cam quýt.

Đây là một nguồn chính của sụ thối quả sau thu hoạch và chịu trách nhiệm cho bệnh sau thu hoạch lan rộng ở trái cây có múi được gọi là thối xanh hoặc mốc xanh. Trong tự nhiên, mầm bệnh vết thương hoại tử này phát triển thành sợi và sinh sản vô tính thông qua việc sản xuất các conidiophores. Tuy nhiên, P. Digitatum cũng có thể được nuôi cấy trong môi trường phòng thí nghiệm. Bên cạnh vòng đời gây bệnh, P. Digitatum cũng tham gia vào các tương tác giữa người, động vật và thực vật khác và hiện đang được sử dụng trong sản xuất các xét nghiệm phát hiện nấm dựa trên miễn dịch cho ngành công nghiệp thực phẩm.

Penicillium digitatum (Pers.) Sacc., 1881

Пеници́лл (пеници́ллий) па́льчатый (лат. Penicíllium digitátum) — вид несовершенных грибов (телеоморфная стадия неизвестна), относящийся к роду Пеницилл (Penicillium).

Часто поражает плоды апельсина, реже — других цитрусовых культур.

Колонии на агаре Чапека (англ.)русск. плохо растущие и слабо спороносящие, за 14 дней едва достигают диаметра в 1 см. Колонии на агаре с солодовым экстрактом быстрорастущие, плоские, бархатистые, жёлто-зеленовато-коричневые, спороношение среднеобильное. Реверс неокрашенный или светло-грязно-коричневый. Запах сильный, напоминают гниющие плоды цитрусовых. При 37 °C рост отсутствует.

Конидиеносцы двухъярусные, трёхъярусные или неправильные, гладкостенные. Фиалиды в пучках на концах метул по 3—6, нередко также одиночные, цилиндрические или широкофляговидные, с крупной цилиндрической шейкой на верхушке, 10—30 × 3,5—5 мкм. Конидии цилиндрические, затем эллиптические, гладкостенные, 3,5—14 × 2,8—8 мкм, в неправильных цепочках.

Легко определяемый вид, отличающийся от других пенициллов крупными цилиндрическими конидиями и оливково-коричневой окраской колоний. Специфичный слабый патоген цитрусовых.

Слабый довольно специфичный фитопатоген. Обыкновенно встречается на плодах цитрусовых, наиболее часто — апельсина; редко выделяется с иных растительных субстратов. Борьба с пенициллом осложняется существованием широко распространённых рас, устойчивых к тиабендазолу, беномилу и энилконазолу.

Penicillium digitatum (Pers.) Sacc., Fung. Ital. tab. 894 (1881). — Aspergillus digitatus Pers., Disp. Meth. Fung. 41 (1794). — Monilia digitata (Pers.) Pers., Syn. Meth. Fung. 693 (1801), Fr., Syst. Mycol. 3: 411 (1832).

Пеници́лл (пеници́ллий) па́льчатый (лат. Penicíllium digitátum) — вид несовершенных грибов (телеоморфная стадия неизвестна), относящийся к роду Пеницилл (Penicillium).

Часто поражает плоды апельсина, реже — других цитрусовых культур.

分類 界 : 菌界 Fungi 門 : 子嚢菌門 Ascomycota 綱 : ユーロチウム菌綱 Eurotiomycetes 目 : ユーロチウム目 Eurotiales 科 : マユハキタケ科 Trichocomaceae 属 : アオカビ属 Penicillium 和名 ミドリカビ病菌

分類 界 : 菌界 Fungi 門 : 子嚢菌門 Ascomycota 綱 : ユーロチウム菌綱 Eurotiomycetes 目 : ユーロチウム目 Eurotiales 科 : マユハキタケ科 Trichocomaceae 属 : アオカビ属 Penicillium 和名 ミドリカビ病菌 ミドリカビ病菌は、緑かび病と名付けられた病害を起こす病原菌の総称。緑かび病という名のつけられた病害はすべて、Penicillium属菌によるものである。

日本植物病名目録[1]によると、緑かび病という病害には以下のものがある。

通常は収穫後のミカンに発生するが、樹上の傷果でも見られる。菌の発育温度は6-33°Cであり、最適温度は25°C前後である[2]。

ミドリカビ病菌は、緑かび病と名付けられた病害を起こす病原菌の総称。緑かび病という名のつけられた病害はすべて、Penicillium属菌によるものである。

日本植物病名目録によると、緑かび病という病害には以下のものがある。