en

names in breadcrumbs

Dinosourusse Kladistiese klassifikasie Koninkryk: Animalia

Dinosourusse was langer as 160 miljoen jaar die oorheersende landdiere, van laat in die Trias-periode (ongeveer 230 miljoen jaar gelede) tot aan die einde van die Kryt-periode (ongeveer 65 miljoen jaar gelede), toe die meeste uitgesterf het tydens die Kryt-Paleogeen-uitwissing. Fossielrekords dui daarop dat voëls tydens die Jura-periode uit Theropoda-dinosourusse ontwikkel het en die meeste paleontoloë beskou hulle as die enigste dinosourus-klade wat tot vandag nog lewe.[1]

Dinosourusse is ’n groep diere wat baie van mekaar verskil. Paleontoloë het met behulp van fossiele wêreldwyd reeds meer as 500 afsonderlike genera geïdentifiseer[2] wat saam meer as 1 000 spesies bevat.[3] Sommige dinosourusse was herbivore, terwyl ander karnivore was. Sommige was tweevoetig, ander viervoetig en nog ander kon tussen hierdie twee posture wissel. Baie spesies het uitvoerige skeletveranderings ondergaan, soos benerige pantsers, horings of kruine. Alhoewel hulle oor die algemeen as groot diere bekend is, was baie dinosourusse so groot soos mense of selfs kleiner. Die meeste het neste gebou en eiers gelê.

Die naam "dinosourus" is vir die eerste keer in 1842 deur sir Richard Owen gebruik en is afgelei van die Griekse deinos en sauros, letterlik "vreeslike" of "wonderlike akkedis". Vir die eerste helfte van die 20ste eeu het wetenskaplikes geglo dinosourusse was stadige, dom, koudbloedige diere. Navorsing en ontdekkings sedert die 1970's dui egter op aktiewe diere met ’n verhoogde metabolisme en verskeie aanpassings vir sosiale interaksie.

Sedert die eerste dinosourusfossiel vroeg in die 19de eeu gevind is, is saamgestelde dinosourusskelette ’n gewilde trekpleister in museums dwarsoor die wêreld. Hulle het ook ’n plek in die wêreldkultuur en bly steeds gewild: as onderwerp vir gewilde boeke en rolprente soos Jurassic Park of nuusitems wat dikwels in die media gedek word.

Die takson Dinosauria is in 1842 amptelik so genoem deur die paleontoloog sir Richard Owen, wat dit gebruik het om te verwys na die "kenmerkende stam of suborde van souriese reptiele" wat in Engeland en dwarsoor die wêreld erken is.[4] Die term is afgelei van die Antieke Griekse woorde δεινός (deinos, "vreeslike of "verskriklik groot") en σαῦρος (sauros, "akkedis" of "reptiel").[4][5] Owen het dit bloot gebruik om te verwys na die grootte van die diere[6] en nie na hul voorkoms nie.

Volgens filogenetiese taksonomie word dinosourusse gewoonlik gedefinieer as ’n groep "bestaande uit Triceratops, Neornithes (moderne voëls), hul laaste gemeenskaplike voorsaat en alle afstammelinge".[7] Daar is ook al voorgestel dat Dinosauria gedefinieer word na aanleiding van die laaste gemeenskaplike voorsaat van Megalosaurus en Iguanodon, aangesien dit twee van die drie genera is wat Owen genoem het toe hy die Dinosauria erken het.[8] Albei definisies lei tot dieselfde groepe diere wat as dinosourusse beskou word.

Voëls word nou erken as die enigste oorlewende linie van teropode-dinosourusse. In tradisionele taksonomie is voëls beskou as ’n aparte klas wat ontwikkel het uit dinosourusse, ’n uitgestorwe superorde. Die meeste moderne paleontoloë staan egter die idee voor dat vir ’n groep om natuurlik te wees, alle afstammelinge van lede van die groep ook in die groep ingesluit moet wees. Voëls word dus beskou as dinosourusse, en dinosourusse is dus nie uitgesterf nie. Voëls word geklassifiseer as behorende tot die subgroep Maniraptora, wat Coelurosauria is, wat Theropoda is, wat Saurischia is, wat dinosourusse is.[10]

Dinosourusse kan in die algemeen beskryf word as argosourusse met ledemate wat reguit onder die lyf gehou word.[11] Baie prehistoriese diere word dikwels as dinosourusse beskou maar word nie wetenskaplik as dinosourusse geklassifiseer nie, soos ichtiosourusse, mosasourusse, plesiosourusse, pterosourusse en Dimetrodon; nie een van hulle het die reguit ledemate onder die lyf wat kenmerkend van ware dinosourusse is nie.[12] Dinosourusse was die oorheersende landgewerweldes van die Mesosoïkum, veral die Jura- en Kryt-periode. Ander groepe diere het beperkte grootte en nisse gehad; soogdiere was byvoorbeeld selde groter as katte en was dikwels knaagdiergrootte-vreters van klein prooi.[13]

Dinosourusse was ’n groot groep uiteenlopende diere; volgens ’n 2006-studie is meer as 500 nie-vlieënde genera al tot dusver geïdentifiseer, en die totale getal genera in die fossielrekord word geraam op sowat 1 850, waarvan byna 75% nog ontdek moet word.[14] Volgens ’n vroeëre studie het daar sowat 3 400 dinosourus-genera bestaan, insluitende talle wat nie in die fossielrekord behoue sou gebly het nie.[15] Teen 17 September 2008 het altesaam 1 047 verskillende spesies dinosourusse al name gehad.[16] Van hulle was plantvreters, ander vleisvreters, insluitende saad-, vis-, insek- en allesvreters. Terwyl die vroeë dinosourusse tweevoetig was (soos moderne voëls), was sommige prehistoriese spesies viervoetig en ander, soos Ammosaurus en Iguanodon, kon ewe maklik op twee of vier voete loop. Skedelaanpassings soos horings en plate was algemeen, terwyl sommige spesies pantsers gehad het. Hoewel hulle bekend is as groot diere, was die meeste dinosourusse in die Mesosoïkum so groot soos mense of kleiner. Dinosourusse was minstens teen die Vroeë Jura oor die wêreld versprei.[17] Moderne voëls bewoon feitlik alle habitats, van die land tot die see.

Dinosourusse het tydens die Middel- tot Laat Trias uit hul argosourus-voorsate ontwikkel, rofweg 20 miljoen jaar gelede nadat ’n geskatte 95% van alle lewe op aarde in die Perm-Trias-uitwissing uitgesterf het.[18][19] Radiometriese datering van die rotsformasie wat fossiele bevat van die vroeë dinosourus-genus Eoraptor van sowat 231,4 miljoen jaar gelede, wys dat hulle in dié tyd in die fossielrekord aanwesig was.[20] Paleontoloë dink Eoraptor verteenwoordig die gemeenskaplike voorsaat van alle dinosourusse;[21] as dit waar is, beteken dit die eerste dinosourusse was klein, tweevoetige roofdiere.[22] Die ontdekking van primitiewe, dinosourusagtige Ornithodira soos Marasuchus en Lagerpeton in Argentiniese Middel-Trias-strata ondersteun dié teorie; ontleding van fossiele dui daarop dat hierdie diere wel klein, tweevoetige roofdiere was. Dinosourusse kon al 243 miljoen jaar gelede hul verskyning gemaak het, soos gesien kan word uit oorblyfsels van die genus Nyasasaurus uit daardie periode, hoewel bekende fossiele te verbrokkel is om te bepaal of hulle dinosourusse was of net naby-verwante.[23]

Toe dinosourusse op die toneel verskyn, was die land bewoon deur verskeie soorte argosourusse en terapsides soos etosourusse, sinodonte, disinodonte en ornitosoegides. Die meeste van hierdie ander diere het uitgesterf in die Trias in een van twee uitwissingsvoorvalle. Die eerste was tussen die tydsnedes Karnium en Norium sowat 215 miljoen jaar gelede, toe disinodonte en ’n verskeidenheid argosouromorfe uitgesterf het. Dit is gevolg deur die Trias-Jura-uitwissing sowat 200 miljoen jaar gelede, wat die einde ingelui het vir die meeste van die ander groepe vroeë argosourusse soos die etosourusse, ornitosoegides en fitosourusse. Dié verliese het daartoe gelei dat die land oorheers is deur krokodilagtiges, dinosourusse, soogdiere, pterosourusse en skilpaaie.[7] Die eerste paar linies van die vroeë dinosourusse het gediversifiseer in die Karnium- en die Norium-tydsnede van die Trias, moontlik deur die nisse te vul wat deur uitgestorwe spesies leeg gelaat is.[9]

Die evolusie van dinosourusse ná die Trias het gevolg op veranderings in plantegroei en die ligging van die kontinente. In die Laat Trias en Vroeë Jura was die landmassas verbind in een superkontinent, Pangea, en die wêreldwye dinosourusbevolkings het meestal bestaan uit selofisoïed-karnivore (vleisvreters) en vroeë souropodomorf-herbivore (plantvreters).[24] Naaksadiges (veral konifers), ’n moontlike voedselbron, het in die Laat Trias begin gedy. Vroeë souropodomorfe het nie gesofistikeerde meganismes gehad om kos in die mond te verwerk nie, en moes ander metodes verder af in die verteringskanaal gebruik om die kos op te breek.[25] Die algemene gelyksoortigheid van dinosourusse het tot in die Middel- en Laat Jura voortgeduur, met die meeste bevolkings wat bestaan het uit roofdiere soos seratosouriërs, spinosouroïede en karnosouriërs, en plantvreters soos stegosouriese ornitiskiums en groter souropodes. Ankilosouriërs en ornitopodes het ook al hoe algemener geraak, maar prosouropodes het uitgesterf. Konifers en pteridofiete was die mees algemene plante. Souropodes, soos die vroeëre prosouropodes, het ook nie kos in die mond verwerk nie, maar ornitiskiums het verskeie maniere ontwikkel om kos in die mond te hanteer, insluitende moontlike wang-agtige organe om die kos in die mond te hou, en kaakbewegings om dit fyn te maal.[25] Nog ’n noemenswaardige gebeurtenis in die Jura was die verskyning van ware voëls, wat afgestam het van selurosouriërs.[26]

Teen die Vroeë Kryt en die voortdurende verbrokkeling van Pangea, het dinosourusse op die onderskeie landmassas begin verskil. Vroeg in dié tydperk het ankilosouriërs, iguanodonte en brachiosourides deur Europa, Noord-Amerika en Noord-Afrika begin versprei. Hulle is later in Afrika aangevul of vervang deur groot spinosouride- en karcharodontosouride-teropodes, en rebbachisouride- en titanosouride-souropodes, wat ook in Suid-Amerika voorgekom het. In Asië het selurosouriërs soos dromeosourides, troödontides en oviraptorosouriërs algemene teropodes geword, en ankilosourides en vroeë seratopsiërs soos Psittacosaurus het belangrike plantvreters geword. Intussen het Australië die tuiste geword van primitiewe ankilosouriërs, hipsilofodonte en iguanodonte.[24] Dit lyk of die stegosouriërs in die een of ander stadium van die Vroeë Kryt en vroeë Laat Kryt uitgesterf het. ’n Groot verandering in die Vroeë Kryt, wat in die Laat Kryt in ’n groter mate voortgesit is, is die evolusie van blomplante. Terselfdertyd het verskeie groepe plantvreters meer gesofistikeerde maniere ontwikkel om kos in die mond met tande fyn te maal.

Daar was in die Laat Kryt drie groot bevolkings dinosourusse. Op die noordelike kontinente Noord-Amerika en Asië was die meeste teropodes tirannosourides en verskeie soorte kleiner teropodes, terwyl die plantvreters veral bestaan het uit hadrosourides, seratopsiërs, ankilosourides en pachisefalosouriërs. Op die suidelike kontinente, wat die nou verbrokkelende Gondwana uitgemaak het, was abelisourides die algemene teropodes, en titanosouriër-souropodes die algemene plantvreters. In Europa was dromeosourides, rabdodontide-iguanodonte, nodosouride-ankilosouriërs en titanosouriër-souropodes volop.[24] Blomplante het toegeneem[25] en die eerste grassoorte het aan die einde van die Kryt verskyn.[27] Hadrosourides, wat kos gemaal het, en seratopsiërs, wat kos stukkend geskeur het, het wydverspreid in Noord-Amerika en Asië geword. Teropodes het ook versprei as plant- en allesvreters, en terisinosouriërs en ornitomimosouriërs het algemeen geraak.[25]

In die Kryt-Paleogeen-uitwissing van sowat 66 miljoen jaar gelede, aan die einde van die Kryt-periode, het alle dinosourusgroepe uitgesterf, behalwe Neornithes-voëls. Sommige ander diapsidegroepe soos krokodilagtiges, sebesosoegiërs, skilpaaie, akkedisse, slange, sfenodontes en choristoderas het ook oorleef.[28]

Die oorlewende linies Neornithes-voëls, insluitende die voorsate van moderne loopvoëls (eende en hoenders) en watervoëls, het aan die begin van die Paleogeen-periode vinning gediversifiseer en nisse gevul wat leeg gelaat is deur dinosourusgroepe. Soogdiere het egter ook vinnig gediversifiseer en het die nisse op land uiteindelik oorheers.[29]

Dinosourusse is argosourusse, nes moderne krokodilagtiges. Binne die argosourusgroep word dinosourusse veral deur hul loop onderskei. Dinosourusse se bene strek van die lyf af ondertoe, terwyl die bene van akkedisse en krokodille na die kant toe uitstrek.[30]

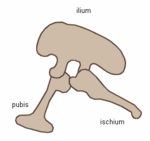

Dinosourusse as ’n klade word verdeel in twee hoofgroepe: souriskiums (Saurischia) en ornitiskiums (Ornithischia). Souriskiums sluit in dié taksa wat ’n meer onlangse gemeenskaplike voorsaat met voëls deel as met ornitiskiums, terwyl ornitiskiums dié taksa insluit wat ’n meer onlangse gemeenskaplike voorsaat met Triceratops deel as met souriskiums. Anatomies kan die twee groepe veral uitmekaar geken word deur die struktuur van hul pelvis. Vroeë souriskiums ("akkedisheupe", van die Griekse σαῦρος sauros, "akkedis", en ἰσχίον ischion, heupgewrig) het die heupstruktuur van hul voorsate behou. Ornitiskiums ("voëlheupe", van die Griekse ορνιθειος ornitheos, "voël", en ισχιον ischion, "heupgewrig") het ’n aangepaste pelvisstruktuur.

Saurischia-pelvisstruktuur (linkerkant).

Ornithischia-pelvisstruktuur (linkerkant).

Die volgende lys is ’n vereenvoudigde klassifikasie van groepe gebaseer op hul evolusionêre verwantskappe. Dit is georganiseer volgens ’n lys Mesosoïese dinosourusspesies deur Holtz (2008).[31]

Die dolk (†) toon groepe aan met geen oorlewende lede nie.

Kennis oor dinosourusse kom van ’n verskeidenheid fossiele en niefossiele rekords, insluitende gefossileerde bene, uitwerpsels, vere, velafdrukke, interne organe, gastroliete, voetspore en sagte weefsel.[32][33] Baie studieterreine dra by tot die mens se begrip van dinosourusse, insluitende fisika, chemie, biologie en paleontologie. Twee onderwerpe wat veral deeglik bestudeer word, is grootte en gedrag.[34]

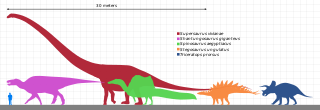

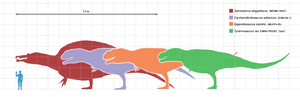

Bewyse dui daarop dat die grootte van dinosourusse gewissel het tydens die geologiese periodes Trias, Vroeë Jura, Laat Jura en Kryt.[21] Teropode-roofdiere in die Mesosoïkum-era het gewoonlik tussen 100 en 1 000 kg geweeg, terwyl huidige soogroofdiere hoogstens 10 tot 100 kg weeg.[35]

Die souropodes was die grootste en swaarste dinosourusse. Vir ’n groot deel van die dinosourus-tydperk was die kleinste souropodes groter as enigiets anders in hul habitat, en die grootste een was ’n grootteorde groter as enigiets anders wat sedertdien die aarde bewandel het. Reusagtige prehistoriese soogdiere soos die Paraceratherium (die grootste landsoogdier nog) is verdwerg deur die groot souropodes, en net moderne walvisse is byna so groot of groter.[36]

Wetenskaplikes sal waarskynlik nooit seker wees watter dinosourusse die grootste of die kleinste was wat ooit bestaan het nie. Dit is omdat net ’n baie klein persentasie diere gefossileer word, en die meeste daarvan is onder die grond begrawe. Min van die fossiele wat ontdek word, is volledige skelette, en afdrukke van velle en ander sagte weefsel is skaars. Die rekonstruksie van volledige skelette deur ’n vergelyking met die grootte en morfologie van soortgelyke, beter bekende spesies is ’n onnoukeurige kuns, en die rekonstruksie van spiere en ander organe is hoogstens ingeligte raaiskote.[37]

Die langste en swaarste dinosourus volgens goeie fossiele is Giraffatitan brancai (voorheen geklassifiseer as ’n spesie van Brachiosaurus). Die oorblyfsels is tussen 1907 en 1912 in Tanzanië ontdek. Die bene van verskeie individue van dieselfde grootte is in die skelet geïnkorporeer;[38] dit is 12 m hoog en 22,5 m lank, en sou behoort het aan ’n dier wat tussen 30 000 en 60 000 kg geweeg het. Die langste volledige dinosourus is die 27 m lange Diplodocus, wat in 1907 in Wyoming, VSA, ontdek is.[39]

Daar was groter dinosourusse, maar kennis oor hulle is gebaseer op ’n paar stukke fossiele. Die meeste van die grootste plantvretende voorbeelde is almal in die 1970's of later ontdek, en sluit in die massiewe Argentinosaurus, wat tussen 80 000 en 100 000 kg kon geweeg het; van die langstes was die 33,5 m lange Diplodocus hallorum[40] en die 33 m lange Supersaurus.[41] Die hoogste een was die 18 m hoë Sauroposeidon, so hoog soos ’n gebou van ses verdiepings. Die swaarste en langste van hulle almal was dalk Amphicoelias fragillimus, wat net bekend is van een, nou verlore, gedeeltelike werwelboog wat in 1878 beskryf is. Die dier kon 58 m lank gewees en meer as 120 000 kg geweeg het.[40] Die grootste bekende karnivoor was Spinosaurus, wat 16 tot 18 m lank was en 8 150 kg kon geweeg het.[42]

As ’n mens nie voëls insluit nie, was die kleinste bekende dinosourus omtrent so groot soos ’n duif.[43] Die kleinste nie-vlieënde dinosourusse was die naaste aan voëls verwant. Die algehele lengte van Anchiornis huxleyi se skelet was byvoorbeeld minder as 35 cm.[43][44] A. huxleyi is tans die kleinste nie-vlieënde dinosourus wat van ’n volwasse fossiel beskryf is, met ’n geskatte gewig van 110 g.[44] Die kleinste plantvretende, nie-vlieënde dinosourus sluit in Microceratus en Wannanosaurus (elk sowat 60 cm lank).[31][45]

Baie moderne voëls is baie sosiaal en kom dikwels in swerms voor. Daar is algemene konsensus dat ’n deel van die gedrag van voëls, sowel as krokodille (voëls se naaste lewende verwante), ook algemeen in uitgestorwe dinosourusse was. Vertolkings van die gedag van fossiele spesies word gewoonlik gebaseer op die posisie van skelette en hul habitat, rekenaarsimulasies van hul biomeganika en vergelykings met moderne diere in soortgelyke ekologiese nisse.

Die eerste moontlike bewyse van groepvorming as ’n algemene gedrag onder dinosourusse buiten voëls was die ontdekking in 1878 van 31 Iguanodon bernissartensis in België. Daar is destyds geglo die ornitiskiums het omgekom nadat hulle saam in ’n diep sinkgat geval en verdrink het.[46] Ander voorbeelde van groepe diere wat saam gesterf het, is sedertdien ontdek. Dit, tesame met die spore van groepe diere, dui daarop dat groepvorming algemeen was onder baie vroeë dinosourusspesies. Voetspore van honderde of selfs duisende herbivore dui daarop dat hulle in groot troppe beweeg het, soos bisons of springbokke. Souropode-spore bewys dié diere het beweeg in groepe wat uit meer as een spesie bestaan het, of minstens in Oxfordshire, Engeland,[47] hoewel daar geen ander bewyse is van troppe nie.[48]

Om saam in groepe te beweeg, was dalk ’n metode van verdediging, vir migrasiedoeleindes of om beskerming aan die jong diere te bied. Daar is bewyse dat baie soorte stadig groeiende dinosourusse, insluitende verskeie teropodes, souropodes, ankilosouriërs, ornitopodes en seratopsiërs, groepe van onvolwasse individue gevorm het. Daar word ook geglo dinosourusse het troppe gevorm om saam groot prooi te jag.[49] Dié gedrag is egter ongewoon onder voëls, krokodille en ander reptiele.

Uit ’n gedragsoogpunt is een van die waardevolste fossiele in 1971 in die Gobiwoestyn ontdek. Dit het ’n velosiraptor ingesluit wat ’n protoseratops aanval;[50] dit het ’n bewys verskaf dat dinosourusse mekaar wel aangeval het.[51] Nog ’n bewys is die fossiel van ’n gedeeltelik herstelde stert van ’n edmontosourus; die stert is op so ’n manier beskadig dat dit wys die dier is gebyt deur ’n tirannosourus, maar dat dit die aanval oorleef het.[51]

Vergelykings tussen die buiteoogvliesringe van dinosourusse en moderne voëls is al gebruik om die aktiwiteitspatrone van dinosourusse vas te stel. Hoewel sommige wetenskaplikes meen dinosourusse was bedags aktief, wys hierdie vergelykings klein roofdiere soos die dromeosourides, juravenators en megapnosourusse was waarskynlik snags aktief. Groot en middelslag-dinosourusse kon bedags en snags ewe aktief gewees het, hoewel die klein ornitiskium agilisourus bedags aktief was.[52]

Dit is bekend dat moderne voëls kommunikeer deur middel van visuele en klankseine, en die verskeidenheid van visuele vertoonstrukture onder fossiele dinosourusgroepe toon aan visuele kommunikasie was belangrik onder hulle. Oor die gebruik van klank is egter minder bekend. In 2008 het die paleontoloog Phil Senter bevind die meeste Mesosoïese dinosourusse het nie geluide gemaak nie, ondanks die uitbeelding van brullende dinosourusse in rolprente.[53][54] Hy het bevind die stembande in die larinks het waarskynlik verskeie kere ontwikkel in reptiele, insluitende krokodille, wat gromgeluide in die keel kan maak. Voëls het egter nie ’n larinks nie en gebruik ’n sirinks, ’n stemorgaan wat uniek is aan voëls.[55]

Die ontdekking dat voëls ’n soort dinosourus is, wys die dinosourusbevolking as ’n geheel het nie uitgesterf soos meestal gemeen word nie.[56] Alle nie-vlieënde dinosourusse en baie groepe voëls het egter wel sowat 66 miljoen jaar gelede uitgesterf tydens die Kryt-Paleogeen-uitwissing. Baie ander groepe diere het ook in dié tyd uitgesterf, onder meer ammoniete, plesiosourusse, pterosourusse en baie groepe soogdiere.[17] Daar was nie groot verliese onder insekte nie en hulle was dus waarskynlik kos vir van die oorlewende dierspesies.

Die aard van die massauitwissing word sedert die 1970's baie goed nagevors. Daar is tans verskeie teorieë daaroor en die een wat deur die meeste wetenskaplikes ondersteun word, is dat dit veroorsaak is deur ’n groot komeet of asteroïde wat die aarde getref het en ’n katastrofale uitwerking op die omgewing gehad het.

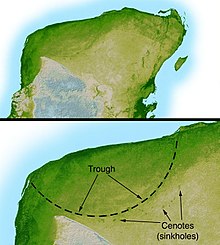

Die impakteorie is ondersteun deur die ontdekking van die 18 km wye Chicxulub-krater in die laat 1970's in die Golf van Meksiko,[57] wat beskou word as bewys van ’n groot, katastrofale impak.[58] As en stof het daarna onder meer die son se strale afgekeer en dus fotosintese onmoontlik gemaak.[59] Brande het ook waarskynlik wêreldwyd voorgekom weens die hitte en brandende brokstukke wat deur die impak veroorsaak is. Onlangse navorsing het getoon die wêreldwye puinlaag wat deur die impak gevorm is, bevat genoeg roet om te kan aflei die hele biosfeer het gebrand.[60]

Die asteroïde (of komeet) het in die see geland en sou enorme tsoenami's veroorsaak het, waarvoor bewyse gevind is op verskeie plekke in die Oos-VSA en om die Karibiese See – seesand op plekke wat toe in die binneland geleë was, en plantoorblyfsels en aardrotse in see-sedimente wat dateer uit die tyd van die impak.

In Maart 2010 het ’n internasionale paneel wetenskaplikes die asteroïde-teorie, spesifiek die Chicxulub-impak, onderskryf as die oorsaak van die uitwissing. ’n Span van 41 wetenskaplikes het 20 jaar se wetenskaplike geskrifte nagevors en enige teorieë oor enorme vulkaniese uitbarstings verwerp. Hulle het vasgestel die uitwissing is veroorsaak deur die Chicxulub-impak, wat soveel energie opgewek het as 100 teraton TNT – meer as ’n miljard keer die energie van die bomme op Nagasaki en Hirosjima.[58]

Daar is egter wetenskaplikes wat glo die uitwissing is veroorsaak of vererger deur ander faktore soos vulkaniese uitbarstings,[61] klimaatsveranderings en/of ’n verandering in seevlakke.

Voor 2000 is argumente dat basaltlawa van die Dekan-trappe in Indië die uitwissing veroorsaak het, gewoonlik verbind met die opinie dat die uitwissing geleidelik plaasgevind het. Basaltlawa-voorvalle het omstreeks 68 miljoen jaar gelede begin en langer as 2 miljoen jaar geduur. Die mees onlangse getuienis dui daarop dat die trappe oor ’n tydperk van 800 000 jaar plaasgevind het, oor die tyd van die Kryt-Paleogeen-grens (K-Pg-grens), en dit kon verantwoordelik gewees het vir die uitwissing en die stadige herstel van die biotika daarna.[62]

Daar is duidelike bewyse dat seevlakke in die Maastricht, die laaste etage van die Kryt-periode, meer gedaal het as op enige ander tyd in die Mesosoïese Era. Dit is moontlik veroorsaak deurdat oseaanriwwe minder aktief geraak en toe onder hul eie gewig gesink het.[17][63]

’n Groot regressie sou die gebied van die kontinentale plat aansienlik verklein het – en dit is waar die meeste seespesies aangetref is. Die regressie sou ook klimaatsveranderings teweeggebring het, deels deur winde en seestrome te ontwrig en deels deur die Aarde se albedo te verminder en temperature wêreldwyd te laat toeneem.[64]

Regressie het ook die verlies aan binneseë tot gevolg gehad. Dit het habitats in ’n groot mate verander en kusvlaktes vernietig.

Die fossiele van nie-vlieënde dinosourusse word soms bo die K-Pg-grens ontdek. In 2001 het die paleontoloë Zielinski en Budahn na bewering ’n enkele Hadrosauridae-beenfossiel in die San Juan-vallei in Nieu-Mexiko ontdek en dit beskryf as ’n bewys dat dinosourusse in die Paleoseen-epog voorgekom het. Die formasie waarin dit ontdek is, is gedateer as komende uit die Paleoseen, sowat 64,5 miljoen jaar gelede. As die been nie vanweë weerstoestande na ’n jonger stratum verplaas is nie, sou dit wel ’n bewys wees dat sommige dinosourus-bevolkings vir minstens ’n halfmiljoen jaar in die Kainosoïese Era oorleef het.[65]

Nog bewyse sluit in dinosourus-oorblyfsels in die Hell Creek-formasie in Amerika wat 40 000 jaar jonger as die K-Pg-grens is. Ook in Sjina en ander dele van die wêreld was daar berigte oor sulke vondste.[66] Baie wetenskaplikes glo die bene het uitgespoel en is toe in veel jonger afsettings herbegrawe.[67][68] Direkte datering van die bene self steun egter die jonger datum, en ander daterings dui op ’n ouderdom van 64,8 miljoen jaar.[69]

Al is dit korrek, weerspreek die vonds van ’n paar dinosourusse wat tot in die vroeë Paleoseen oorleef het, nie die feite van die massauitwissing nie.[67]

|format= requires |url= (help). Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University. ISBN 0-912532-57-2. Besoek op 2009-09-22. Dinosourusse was langer as 160 miljoen jaar die oorheersende landdiere, van laat in die Trias-periode (ongeveer 230 miljoen jaar gelede) tot aan die einde van die Kryt-periode (ongeveer 65 miljoen jaar gelede), toe die meeste uitgesterf het tydens die Kryt-Paleogeen-uitwissing. Fossielrekords dui daarop dat voëls tydens die Jura-periode uit Theropoda-dinosourusse ontwikkel het en die meeste paleontoloë beskou hulle as die enigste dinosourus-klade wat tot vandag nog lewe.

Dinosourusse is ’n groep diere wat baie van mekaar verskil. Paleontoloë het met behulp van fossiele wêreldwyd reeds meer as 500 afsonderlike genera geïdentifiseer wat saam meer as 1 000 spesies bevat. Sommige dinosourusse was herbivore, terwyl ander karnivore was. Sommige was tweevoetig, ander viervoetig en nog ander kon tussen hierdie twee posture wissel. Baie spesies het uitvoerige skeletveranderings ondergaan, soos benerige pantsers, horings of kruine. Alhoewel hulle oor die algemeen as groot diere bekend is, was baie dinosourusse so groot soos mense of selfs kleiner. Die meeste het neste gebou en eiers gelê.

Die naam "dinosourus" is vir die eerste keer in 1842 deur sir Richard Owen gebruik en is afgelei van die Griekse deinos en sauros, letterlik "vreeslike" of "wonderlike akkedis". Vir die eerste helfte van die 20ste eeu het wetenskaplikes geglo dinosourusse was stadige, dom, koudbloedige diere. Navorsing en ontdekkings sedert die 1970's dui egter op aktiewe diere met ’n verhoogde metabolisme en verskeie aanpassings vir sosiale interaksie.

Sedert die eerste dinosourusfossiel vroeg in die 19de eeu gevind is, is saamgestelde dinosourusskelette ’n gewilde trekpleister in museums dwarsoor die wêreld. Hulle het ook ’n plek in die wêreldkultuur en bly steeds gewild: as onderwerp vir gewilde boeke en rolprente soos Jurassic Park of nuusitems wat dikwels in die media gedek word.

Dinosauriu ye'l nome de cualesquier miembru d'un grupu d'arcosaurios surdíu nel caberu periodu del Triásicu (hai cerca de 230 millones d'años). Foi la especie dominante de la fauna terrestre pente'l mayor tiempu de la era mesozoica, dende l'aniciu del Xurásicu hasta l'acabu del periodu Cretácicu (hai cuasi 65 millones d'años).

El registru fósil indica que les aves evolucionaron a partir de dinosaurios teropodos pequeños del Xurásicu, hai 150-200 millones d'años, y son, los únicos dinosaurios que sobrevivieron a la estinción masiva producida a la fin del Mesozoicu. La so evolución dio llugar, tres una fuerte radiación, a les más de 18 000 especies actuales.

'Orde Saurischia'

Dinosauriu ye'l nome de cualesquier miembru d'un grupu d'arcosaurios surdíu nel caberu periodu del Triásicu (hai cerca de 230 millones d'años). Foi la especie dominante de la fauna terrestre pente'l mayor tiempu de la era mesozoica, dende l'aniciu del Xurásicu hasta l'acabu del periodu Cretácicu (hai cuasi 65 millones d'años).

El registru fósil indica que les aves evolucionaron a partir de dinosaurios teropodos pequeños del Xurásicu, hai 150-200 millones d'años, y son, los únicos dinosaurios que sobrevivieron a la estinción masiva producida a la fin del Mesozoicu. La so evolución dio llugar, tres una fuerte radiación, a les más de 18 000 especies actuales.

Dinozavrlar (lat. Dinosauria, qəd. yunan dilindəki δεινός - "dəhşətli" və σαῦρος - "kələz") — Mezozoy erasında Yer kürəsində hakim olan və Trias dövrünün sonlarından başlayaraq (təxminən 230 mln. il əvvəl) Təbaşir dövrünün sonunadək (təxminən 66 min. il əvvəl) 160 milyon il mövcud olmuş quruda yaşayan onurğalı heyvanların üstdəstəsidir.

Təbaşir və Paleogen dövrlərinin sərhədində geoloji baxımdan qısa zaman kəsiyində heyvanların və bitkilərin genişmiqyaslı və kütləvi yox olması zamanı dinozavrların böyük əksəriyyəti məhv olmuşdur.

Daşlaşmış dinozavr qalıqları bütün qitələrdə aşkar olunmuşdur. Hazırda paleontoloqlara 2 şərti qrupa — ətyeyənlər və otyeyənlər — bölünən 500-dən artıq cins və 1000-dən artıq müxtəlif növ kələz məlumdur.

"Dinozavr" termini ingilis paleontoloqu Riçard Oven tərəfindən 1842-ci ildə təklif edilmişdir. Dinozavrlar 160 milyon il ərzində bizim planetimizdə ən üstün canlılar idi. İndi bu nəhəng məxluqların bütün qalıqları sümüklərdir. Daşlaşmış qalıqlar göstərir ki, 65 milyon il əvvəl nəsə Yerin bütün ekosistemini məhv etdi və dinozavrlar bütün başqa növlərin təxminən 50%i ilə birlikdə qəfildən qırıldı. Bəs onların nəslinin kəsilməsinə nə səbəb oldu? Çox illər, bu sual fərziyyələrdə itib -batan sirr olmuşdur.

Müasir dövrdə dinozavrlar uşaqların sevimli film qəhrəmanlarından biridir. Balacaların nəvazişlə “Dino” adlandırdığı bu heyvanlar cizgi filmlərində, adətən, xeyirxah qəhrəman kimi təsvir olunur. Lakin milyon illər əvvələ qayıtsaq, yəqin ki, heç kim bu qorxunc canlı ilə üz-üzə gəlmək istəməzdi. Təxminən 225 milyon il əvvəl Yer kürəsində yaranmış və 160 milyon il ərzində yaşamış dinozavrlar planetimizdə mövcud olmuş ən böyük canlılar idi. Həmin dövrdə insanlar hələ mövcud deyildilər. O zamanlar planetimizdəki heyvanlar və bitkilər də indikilərdən çox fərqlənirdi. Yer kürəsində sürünənlər “ağalıq” edirdi. Onların böyük hissəsini dinozavrlar təşkil edirdi. Bu nəhəng sürünənlərin bəziləri bitkilərlə qidalanan təhlükəsiz dinozavrlar, digərləri isə qorxunc yırtıcılar idi. Dinozavrlar dövrümüzə gəlib çatmayıblar. Alimlər onların zahiri görünüşünü və ölçülərini planetin müxtəlif yerlərində tapılmış sümüklərə əsasən təyin etmişlər. Dinozavrların qalıqları ilk dəfə İngiltərə ərazisində 1815-ci ildə tapılmışdır. Alimlər bu qalıqların nəhəng bir heyvana aid olduğunu heyrət içində müəyyən etmişdilər. O dövrdə insanlar Yer kürəsində nə vaxtsa bu nəhənglikdə heyvanların mövcud olduğundan xəbərsiz idilər. Daha sonra 1826-cı ildə başqa bir ingilis alimi naməlum nəhəng heyvana məxsus olan sümüklər tapdı. Nəhayət, 1842-ci ildə daha bir dinozavr qalıqları tapan ingilis bioloqu Riçard Ouen hər üç tapıntı arasında oxşarlığı müəyyən edərək onların eyni canlı növünə aid olduğunu sübut etdi. O, naməlum heyvanın skeletini qismən bərpa etdi və ona “dinozavr” adı verdi. “Dino” yunanca “qorxunc”, “zavr” isə “kərtənkələ” deməkdir. Bu ad elmdə qəbul olundu. Sonradan bu fəsilədən olan bir çox heyvanların da qalıqları tapıldı: anxizavr, izizavr, karnotavr, anteozavr və başqaları. Bununla belə, “dinozavr” adı həmin heyvan fəsiləsinin ümumi adı kimi qəbul olundu. Dinozavrların sümükləri milyon illərlə üst-üstə qalaqlanmış torpaq laylarının altından, qayaların arasından tapılır. Heyvan və bitki qalıqlarının axtarışı və bərpası ilə məşğul olan alimlər paleontoloq adlanırlar.

Dinozavrların daşlaşmış qalığı: dinozavrlar niyə qırıldı? Yox olma hadisəsi :1970-ci illərdə bu fərziyyələr Kaliforniya Universitetinin Berkley komandanın sayəsində real elmi tədqiqata çevrildi. Geoloq Volter Alvarez İtaliyadaki Guppio dağlarındakı qaya laylarını araşdırırdı. Bu vaxt O Təbaşir və üçüncü dövr laylarının arasında ( bu qatların sərhəddi kt sərhəddi kimi də tanınır) bir qata çatdı. Təbaşir qayası daşlaşmış qalıqlarla dolu, amma üçüncü dövr qayasında heç nə yox idi. Bu qara-qəhvəyi K-T qatı dinozavrların məhv olduğu dövrdə formalaşmışdır.

Alvarez bu laydan atası fizik Luis Alvarezin analiz etməsi üçün bir sıxma götürdü. Onlar nüvə kimyaçısı Elen Michels və Frank Asaronun köməkliyiylə kəşf etdilər ki, o element iridiumun yüksək miqdarını özündə saxlayır. Bu element yer qabığının çox nadir elementidir, amma K-T sərhəddində iridiumun səviyyəsi əvvəlki tapıntılarından 200 dəfə daha çox idi. Bu qədər iridium haradan gəlmişdi? Başqa planetdən gələn komet və asteroidlər kimi o ərazilər iridiumla zəngin idi. Bu qat Alvarezin komandasına asteroidin fərqli əlamətlərini göstərirdi. 1980-ci ildə Luis Alvarez və onun oğlu asteroidlərin dinozavrların məhvinə səbəb olması fikrini irəli sürdülər.

O vaxtdan bəri geokimyaçılar iridium anomaliyalarını K-T sərhəddində dünyanın yüzlərlə ərazisində kəşf etdilər. Bu ərazilərdəki sərhəd qayaları meteorit əlamətlərini heç bir dəyişikliyə uğramadan özündə saxlayır .Bu aşınmış qayalar yüksək hərarət və partlayışın gücündən ərimiş, sınmış və deformasiyaya uğramış fiziki dəyişikliklərin başlama əlamətlərini göstərir. Məsələn kvars kimi dəyişikliyə uğramış minerallar ümumilikdə K-T sərhəd qayasındadır. Bunlar gözlənilməz təzyiq altında formalaşır. İndiki dünya səthində itmiş asteroid izləri vaxtilə nəhəng olub. Asteroidlərin qoyduğu izlər tədqiq edilən ərazilər idi. Asteroidlər hansı ərazilərə düşmüşdü? 1990-cı ildə Arizona Universitetinin mütəxəssisi Alan Hildebrand Meksika Neft Şirkətinin prezidenti işləmiş geofizik Glen Penfieldlə əlaqə qurdu. Penfield onun potensial krater sahəsini kəşf etməsinə inandı. Meksika Neft Şirkətinin Yukatan yarmadasındakı qədim tədqiqat tarixinə baxarkən Penfield qayanın nəhəng batmış bir qövsünü gördü. Sonra o 1960-cı illərin region qravitasiya xəritəsində başqa bir qövs aşkar etdi. Bu qövs böyük dayirəylə formalaşmada ilk uyğun gələni idi. Dərin dairə Yukatan yarmadasının ucunda Puerto Chixulub kəndindin ətrafındaydı. Penfieldin tapdığı krater 100 mil enliyində idi. Penfield bilirdi ki, Meksika Neft Şirkəti 50 il əvvəl Yukatan yarımadasının həmin ərazilərində neft axtarışları aparıb. Tədqiqat quyusu qazılarkən işçilər andezit adlanan qeyri-adi bir vulkanik qayaya çatdılar. Hildebrand və Penfield andezit nümunələrini yenidən tədqiq etdilər. Analizlər zamanı müəyyən olundu ki, qaya özündə çoxlu metamorfik minerallar saxlayır. Daha sonra dəlillər sübut etdi ki, Chixulub krateri K-T təsirli ərazidə idi. Elmi komitə belə qərara gəldi ki, burda nə vaxtsa yer üzərində mövcud olmuş təsirlərdən məhv olmuş solğun çapıqlar var.

Belə ki, 65 milyon il əvvəl Everest dağı boyda 2.6 milyard tonluq asteroid səmadan saatda 40000 mil sürətlə yerə çırpıldı. Asteroid 100 milyon meqaton dinamit enerji ilə Meksika ərazisinə düşdü. Böyük təsirli dalğalar bir saniyəyə yayılırdı. Yaranmış toqquşma nəticəsində Meksika körfəzi ətrafında böyük sunamilər yarandı. Yer titrədi , vulkanlar püskürdü , böyük küləkli qasırğalar yarandı. Atmosferdə ümumilikdə trilyon tonlarla çəkidə kütlə yığıldı. Ətrafı böyük ildırımlar bürüdü. Hər şey 300 mil ərazidə toqquşmanın təsirindən dərhal dağıldı. Toqquşma nəticəsində yaranan toz kütləsi atmosferə yayıldı. Asteroid çirkləndirən ərazilərə günəş işığı düşmürdü. Beləliklə yerdə aylarla qaranlıq hökm sürdü. Qida zənciri dağıldı və dinozavrların 165 milyon illik yerdəki həyatı sona çatdı. Yer kütləsi canlılarının 85% -i məhv oldu. Yalnız 15 % sağ qaldı. İridiumla zəngin lay dinozavrlarla məməlilərin yaşını müəyyən etməyə imkan verdi. Dinozavrların yox olması məməlilərin inkişafına səbəb oldu.

Anchisaurus Plateosaurus Massospondylus Sauropoda Bazal Sauropodalar

Anchisaurus Plateosaurus Massospondylus Sauropoda Bazal Sauropodalar  Brachiosaurus Camarasaurus Ampelosaurus Quş ombalı dinozavrlar (Ornithischia) Heterodontosauridae

Brachiosaurus Camarasaurus Ampelosaurus Quş ombalı dinozavrlar (Ornithischia) Heterodontosauridae  Stegosaurus Kentrosaurus Huayangosaurus Ankylosauria

Stegosaurus Kentrosaurus Huayangosaurus Ankylosauria  Triceratops Protoceratops Torosaurus Ornithopoda Bazal Ornithopodlar

Triceratops Protoceratops Torosaurus Ornithopoda Bazal Ornithopodlar Vikianbarda Dinozavrlar ilə əlaqəli mediafayllar var.

Dinozavrlar (lat. Dinosauria, qəd. yunan dilindəki δεινός - "dəhşətli" və σαῦρος - "kələz") — Mezozoy erasında Yer kürəsində hakim olan və Trias dövrünün sonlarından başlayaraq (təxminən 230 mln. il əvvəl) Təbaşir dövrünün sonunadək (təxminən 66 min. il əvvəl) 160 milyon il mövcud olmuş quruda yaşayan onurğalı heyvanların üstdəstəsidir.

Təbaşir və Paleogen dövrlərinin sərhədində geoloji baxımdan qısa zaman kəsiyində heyvanların və bitkilərin genişmiqyaslı və kütləvi yox olması zamanı dinozavrların böyük əksəriyyəti məhv olmuşdur.

Daşlaşmış dinozavr qalıqları bütün qitələrdə aşkar olunmuşdur. Hazırda paleontoloqlara 2 şərti qrupa — ətyeyənlər və otyeyənlər — bölünən 500-dən artıq cins və 1000-dən artıq müxtəlif növ kələz məlumdur.

An dinosaored (Dinosauria o anv skiantel) zo loened eus klad ar Sauropsida, a vod an holl stlejviled a-vremañ (ar gevrennad Reptilia), an holl evned a-vremañ (ar gevrennad Aves) hag ul lodenn hepken eus an henstlejviled, an holl anezho o tiskenn eus un hendad hepken. Kalz spesadoù dinosaored a oa, liesseurt ha disheñvel-kenañ an eil re diouzh ar re all. Ar re vrudetañ a vevas adalek diwezh an Triaseg (-251 milion a vloavezhioù/Mav) betek fin ar C'hretase (-65,5 Mav), e-pad an oadvezh Mezozoeg pe Eil hoalad (-251 Mav – -65,5 Mav).

Kavadennoù graet nevez zo a laka da soñjal ez eus bet dinosaored abaoe an Triaseg Izel (deroù : -251 Mav) pe an Triaseg Kreiz (diwezh : -228 Mav), pe zoken adalek ar Permian (-299 Mav – -248 Mav). Trevadennet eo bet an holl gevandiroù gant an dinosaored abalamour ma ne oa ket dispartiet c'hoazh ar c'hevandir nemetañ, Pangea e anv, da vare an Triaseg, ha ma'z int en em strewet dre-holl d'ar mare-se hep kaout ezhomm da dreuziñ mor ebet.

Abred pe abretoc'h eo aet an holl zinosaored da get – war-bouez an evned – e-kerzh ar Mezozoeg ; e-pad enkadenn ar C'hretase hag an Trede hoalad (anvet ivez « enkadenn K-T ») ez eo steuziet an dinosaored a veve da vare ar C'hretase uhel (-99,6 Mav – -65,5 Mav).[1]Patrom:'[2]

E miz Ebrel 1842 e voe kinniget an anv dinosaor gant ar paleontologour saoz Richard Owen (1804-1892), diwar an henc'hresianeg saura "glazard, stlejvil" ha deinos "spontus, braouac'hus" abalamour ma oa bras-kenañ (en tu all da 15 m) ar pep brasañ eus an dinosaored a oa bet dizoloet gantañ. Daoust d'an dra-se e c'halle an dinosaored bezañ bihan-kenañ o ment, betek un nebeud kantimetroù.

Kerkent ha kreiz an XIXvet kantved ha betek ar bloavezhioù 1970, an dinosaored a veze gwelet gant ar skiantourien evel loened yen o gwad, dizampart ha goustad, aet da get abalamour d'o sotoni. E 1969, ar paleontologour stadunanat John Ostrom (1928-2005) a roas lañs da « azginivelezh an dinosaored », a sachas evezh ur bern tud war studi an dinosaored, a voe gwelet adalek neuze evel loened oberiant, emwrezek gant emzalc'hioù kevredigezhel kemplezh.

Abaoe ma voe anavezet ar c'hentañ dinosaor, en XIXvet kantved, al loened-se o deus desachet ur bern tud er mirdioù e pep lec'h war an Douar, da welet ar relegoù adsavet eno. Plijout a reont kenañ d'ar vugale koulz ha d'an oadourien. Deuet int da vezañ ul lodenn eus sevenadur pobl an XXvet hag an XXIvet kantved, hag o c'havout a reer taolennet e levrioù hag e filmoù stank-kenañ. Danvez pennañ levrioù ha filmoù brudet ez int, evel Jurassic Park pe Ice Age 3, ha kaoz a vez ingal eus ar c'havadennoù nevez diwar o fenn er media.

Alies e vez implijet ar ger "dinosaor" war ar pemdez evit komz eus stlejviled all eus ar ragistor, evel ar genadoù Dimetrodon, Ichthyosaurus, Mosasaurus, Plesiosaurus ha Pterosaurus, petra bennak ma ne oa ket dinosaored anezho tamm ebet.

Hervez ar renkadur filogenetek e vez termenet an dinosaored evel strollad diskennidi an hendad nevesañ boutin da Driceratops ha d'an evned a-vremañ [3]. Lavaret eo bet ivez e c'hallfe strollad an dinosaored bezañ termenet evel diskennidi hendad nevesañ Megalosaurus hag Iguanodon, abalamour ma'z int daou eus an tri spesad a zo bet meneget gant Richard Owen p'en doa goveliet ar ger dinosaurus [4]. Gant an daou dermenadur avat en em gaver gant ar memes strollad loened anvet "dinosaored". Savet eo bet an termenadurioù-se a-benn klotañ gant meizadoù ar skiantourien kent implij ar filogenetik a-vremañ, kuit da zroukveskañ talvoudegezh ar ger "dinosaor".

Rummatadur an dinosaored a laka kemm etre daou glad bras hervez neuziadurezh lestr o c'horf : Ornithischia ("listri evned") ha Saurischia ("listri stlejviled") eo ar c'hladoù-se.

Emglev zo etre hogos an holl baleontologourien da lâret e tiskenn an evned diouzh an dinosaored Theropoda. Hervez termenadur rik ar c'hladoù e ranker lakaat holl ziskennidi ur memes hendad boutin er memes strollad evit ma vefe savet ar strollad e-giz ma tere : dinosaored eo an evned ha n'eo ket aet an dinosaored da get eta. Renket e vez an evned gant ar pep brasañ eus ar baleontologourien er c'hlad Maniraptora, anezho Coelurosauria, da lâret eo Theropoda, a zo ivez Saurischia, dinosaored anezho. [5]

Dinosaored eo al laboused eta, hervez termenadur ar c'hladoù ; er yezh pemdez avat ne vez ket anv eus al laboused pa gomzer eus "dinosaored". A-benn bezañ sklaeroc'h e vo implijet ar ger « dinosaor » er pennad-mañ evel heñvelster « dinosaor n'eo ket un evn ». Implijet e vo « dinosaor n'eo ket un evn » pa vo ezhomm pouezañ war ar fed-mañ.

Reizh eo en un doare teknikel evel-just lakaat an dinosaored da strollad disheñvel pa implijer renkadur Carl von Linné, ar reizhiad koshañ evit renkadur skiantel ar spesadoù, a zegemer taksonoù parafiletek na endalc'hont ket holl ziskennidi ur memes hendad.

Gaou eo lavaret ez eo an dinosaored loened ragistorel. Ar ger "ragistor" a dalvez da envel ar prantad a ya eus anadur Mab-Den d'ar c'hentañ skridoù. Hervez an termenadurioù resis a vez implijet e krog ar ragistor 5 milion a vloavezhioù zo. An dinosaored ha n'int ket laboused avat zo aet da get 65 milion a vloavezhioù zo. N'o deus ket bevet eta e-pad ar ragistor ha Hominideg ebet ne'n em gavas gant unan anezhe. Loened eus er Mezozoeg int, ha loened ragistorel n'int ket.

Diouzh ar c'harrekaennoù a zo bet kavet e c'haller lavaret e oa ur strollad loened bras eus an dinosaored daoust ma kemmas o ment keitat e-pad an Triaseg, ar Juraseg hag ar C'hretase [6]. Hervez ar paleontologour Bill Erickson (1928-1987) emañ keidenn o fouez etre 9 kg ha 5 tonenn. Ur studiadenn nevez diwar-benn 63 genad dinosaored he deus roet ur geidenn a 850 kg (ur pouez a c'haller keñveriañ ouzh hini un arzh louet) hag ur pouez etre eus tost div donenn, da lâret eo kement hag ur jirafenn. Da 863 g e sav pouez keitat ar bronneged, da lâret eo hini ur c'hrigner bras. Brasoc'h evit an div drederenn eus ar bronneged a-vremañ e oa an dinosaored bihanañ. Brasoc'h e oa ivez ar pep muiañ eus an dinosaored evit 98% eus ar bronneged a-vremañ. [7]

N'eus nemet ul lodenn vihan eus al loened marv a ya da garrekaennoù, hag ul lodenn vihan hepken eus ar re a vez dizoloet zo klok. Eskern hepken a gaver peurliesañ. Ral-kenañ eo roudoù ar c'hroc'henoù pe ar gwiadennoù. Un arz diresis eo adsevel relegenn ur spesad dre geñveriañ ment ha morfologiezh an eskern gant re ur spesad all, ha gwall ziaes eo klask adsevel organoù ha kigennoù. Biken eta ne ouiimp en un doare asur petra e oa ment an dinosaored brasañ ha bihanañ.

E-touez an dinosaored, ar Sauropoda a oa loened bras-meurbet, ar re vrasañ a oa brasoc'h evit an holl loened o deus bevet war an Douar abaoe. Korred en o c'hichen e oa bronneged ragistorel evel Indricotherium pe ar mammout kolombian. N'eus ken un dornadig loened-mor hiziv zo dezhe tost ar memes ment pe unan vrasoc'h, evel ar balum glas a zo 180 tonenn a bouez ennañ hag a dizh 31 metr hirder d'ar muiañ.

Ar brasañ hag ar pounnerañ dinosaor anavet diwar relegoù klok pe dost eo Brachiosaurus brancai (anvet ivez Giraffatitan)[8]. Daouzek metr e oa e uhelder, 22,5 metr e hirder, ha pouezet en dije etre 30 ha 60 tonenn – un olifant afrikan, al loen brasañ a vev war an Douar hiziv, a bouez 7,7 tonenn well-wazh. An dinosaor hirañ en deus lezet ur garrekaenn glok eo Diplodocus a oa 27 metr e hirder ; emañ e Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania abaoe 1907.

Dinosaored brasoc'h a oa, met ne chom anezhe ken un nebeud karrekaennoù diglok peurliesañ. An darn vrasañ anezhe a oa geotdebrerien a zo bet kavet er bloavezhioù 1970 pe diwezhatoc'h, Argentinosaurus en o zouez, en dije tizhet etre 80 ha 100 tonenn. An hini uhelañ, Sauroposeidon, a oa 18 metr, en dije gallet tizhout ur prenestr er 6vet solier.

Un dinosaor brasoc'h c'hoazh, Amphicoelias fragillimus, anavet hepken dre un nebeud karrekaennoù melloù-kein dizoloet e 1878, a c'hallje bezañ tizhet 58 metr hirder ha 120 tonenn a bouez[9]. An hini pounnerañ a c'hallje bezañ bet Bruhathkayosaurus, anavezet fall ha danvez breutadennoù etre an arbennigourien anezhañ c'hoazh, a vije bet dezhañ etre 175 ha 220 tonenn. Peurliesañ e lavarer hiziv ne oa ket en tu all da 139 zonenn, evit 34 metr hirder da Vruhathkayosaurus matleyi.

Ar c'higdebrer brasañ e oa Spinosaurus, dezhañ etre 16 ha 18 metr ha 9 zonenn[10]. Kigdebrerien bras all e oa Giganotosaurus, Mapusaurus, Tyrannosaurus rex ha Carcharodontosaurus.

Pa ne gemerer ket e kont an evned a-vremañ evel an evned-kelien, an dinosaored bihanañ e oa dezhe ment ur vran pe ur penn-yar. An Theropoda Microraptor ha Parvicursor a oa nebeutoc'h evit 60 cm hirder dezhe.

Diazezet e vez ar preder war emzalc'h an dinosaored war ar c'harrekaennoù kavet, metoù al loened, adsavadennoù dre urzhiataer eus o bevmekanikerezh, ha keñveriadennoù gant al loened a-vremañ a vev er memes log ekologel. Diwar kalz martezeadennoù ez eo diazezet ar pezh a soñjomp diwar-benn emzalc'h an dinosaored eta, ha breud a vo diwar-benn lod anezhe e-pad pell c'hoazh moarvat. Emglev zo etre ar skiantourien avat da soñjal e kaver emzalc'hioù boas e-touez ar c'hrokodiled hag al laboused a c'haller adkavout ivez e-touesk an dinosaored.

E 1878 e voe kavet e Bernissart, Belgia, ar c'hentañ prouenn eus bagadoù dinosaored. Eno e voe kavet 31 Iguanodon a oa ar stumm warne da vezañ marvet goude bezañ kouezhet en un toull don hag int beuzet en dour [11]. Petra bennak ma voe dizoloet da c'houde e teue an dilerc'hioù-se diwar tri darvoud disheñvel[12], e voe kavet lec'hioù all ma oa marvet dinosaored a-vagadoù.

Ar roudoù karrekaet niverus a laka da soñjal e oa paot-kenañ ar bagadoù hag ar strolladoù e kalz spesadoù. Roudoù kantadoù pe miliadoù a c'heotdebrerien a ziskouez e c'halle an Hadrosauridae bale a-vagadoù bras, evel ar bizoned pe ar springboked hiziv. Roudoù Sauropoda o deus diskouezet e veaje al loened a-vagadoù a vode meur a spesad a-wezhioù[13], ha re all a zalc'he o re vihan e kreiz ar bagad d'o gwareziñ, diouzh ar roudoù dizoloet e Davenport Ranch, Texas.

Pa voe dizolet e 1978 un neizh Maiasaura ("dinosaor mamm vat") gant ar paleontologour Jack Horner (*1946) e Montana e voe diskouezet e talc'he loened an isurzhiad Ornithopoda d'ober war-dro o re vihan goude ma oa digloret ar vioù[14]. Prouennoù zo ivez en em zalc'he heñvel dinosaored all eus ar C'hretase, evel Saltasaurus, bet dizoloet e 1997 e Patagonia, hag en em vode al loened-se a-viliadoù er memes lec'h da neizhañ, evel ar Manked impalaerel.

Oviraptor Mongolia a voe dizoloet e 1993 gant ur relegenn o tozviñ evel ur yar, ar pezh a dalvez e oa warnañ ur gwiskad pluñv a domme ar vioù[15]. Roudoù karrekaet o deus kadarnaet an emzalc'h a vamm e-touez ar Sauropoda hag an Ornithopoda eus Enez Sgitheanach[16]. Kavet ez eus bet vioù ha neizhioù eus ar pep brasañ eus ar strolladoù dinaosored, gwirheñvel eo e kehente an dinosaored gant o re vihan en un doare heñvel ouzh hini an evned hag ar c'hrokodiled a-vremañ.

Lod eus an dinosaored a save o neizhioù e-kichen mammennoù havel, ar pezh a roe an tu da gaout ur wrez azas hag ingal evit ar vioù. [17]

Re vresk evit an emgannoù e oa krib lod eus an dinosaored, evel re ar c'hlad Marginocephalia, re isurzhiad Theropoda ar c'hlad Eusaurischia, ha re ar genad Hadrosaurus ; moarvat e talveze o c'hrib da sachañ ar parezed pe da spontañ an enebourien, daoust m'hon eus nebeut a elfennoù diwar-benn emzalc'h tachennoù ha paradur an dinosaored.

N'ouzer ket kennebeut penaos e kehente an dinosaored etrezo, met kavadennoù nevez a laka da soñjal e laboure marteze krib kleuz ar spesadoù Lambeosaurinae evel ur c'hef-dasson implijet evit leuskel kriadennoù a bep seurt.

Unan eus ar c'harrekaennoù pouezusañ a voe kavet e gouelec'h Gobi e 1971. Bez' e oa ur Velociraptor hag a dage ur Protoceratops. Dizoloadenn an daou loen krog-ha-krog a brou kalz martezeadennoù.[18] Diskouez a ra e tage hag e tebre an dinosaored an eil re ar re all, petra bennak ma ne oa ket ur souezhadenn evit ar pezh a sell ouzh an Theropoda[19]. Kadarnaet eo bet gant roudoù dent war ur garrekaenn Majungatholus e Madagaskar e 2003[20].

Hervez an dizoladennoù graet hiziv an deiz ne vije bet spesad dinosaor turier ebet, ha nebeut a zinosaored kraper. Evel ma'z eus bet kavet ur bern roudoù spesadoù bronneged a durie hag a grape er C'henozoeg, an diouer a brouennoù diwar-benn spesadoù dinosaored heñvel zo un tamm souezhus.

Un doare mat da gompren emzalc'h ar spesadoù dinosaored eo deskiñ penaos e tilec'hient. Ar bevmekanikerezh peurgetket en deus pourchaset kalz elfennoù evel, da skouer, gouzout pegen buan e rede an dinosaored diwar studi labour ar c'higennoù ha levezon ar c'herc'hellder war framm o relegoù[21], [22], gouzout hag eñ e ranke an Theropoda ramz mont goustatoc'h pa vezent o redek war-lerc'h o freizh kuit da vezañ gloazet[23], ha gouzout hag-eñ e oa gouest ar sauropoda da chom war-neuñv[24].

Betek-henn e lavare ar skiantourien e oa an dinosaored loened a veve diouzh an deiz, e-skoaz ar bronneged kentañ a oa loened bihan a rene o buhez er beuznoz pe diouzh an noz kuit da vezañ taget[25].

E 2011 e voe renet ur studiadenn baleontologek diwar-benn framm lagad an dinosaored : muzuliet e voe hirder poulloù-lagad ha treuzkiz lagadenn sklera 33 spesad Archosauria, keñveriet gant re 164 spesad a hiziv, en o zouez stlejviled, evned ha bronneged. Diskouezet e voe e veve an dinosaored kigdebrer hanter diouzh an noz, an dinosaored a nije ha Pterosauria diouzh an deiz dreist-holl, hag e veve an dinosaored geotdebrer koulz an noz hag an deiz.<0ref>(en) Lars Schmitz & Ryosuke Motani, Nocturnality in Dinosaurs Inferred from Scleral Ring and Orbit Morphology, Science, 14 EBR 2011

A-zivout kennevid an dinosaored, ur studiadenn c'hall diwar-benn aozadur izotopek an oksigen e dent hag eskern 80 dinosaor eus ar C'hretase (Theropoda, Sauropoda, Ornithopoda ha Ceratopsia[26]) hag a zeue eus Norzhamerika, Afrika, Europa hag Azia he deus diskouezet e rankent kaout korfoù emwrezat. Feur an 18O e-keñver hini an 16O — a zo diouzh gwrezverk diabarzh al loened bev — a oa heñvel ouzh hini ar bronneged hag an evned, a zo emwrezat, ha disheñvel a-grenn diouzh hini ar stlejviled a-vremañ, loened gwreztaolus anezhe, diouzh hini Chelonii ha hini Crocodilia karrekaet eus ar C'hretase.

Bezañs frammoù Havers, anezho mikrokanolioù gronnet gant ur gwiskad eskern kengreiz e-barzh ar relegoù, en eskern karrekaet a vefe un elfenn ouzhpenn a lakafe da soñjal o doa korfoù emwrezat.[27]

Ur skipailh eus Florida en deus jedet e oa kenfeur ar gwrezverk ouzh an tolzennad hag ouzh ar feur kreskiñ, eus 25°C evit an dinosaored bihan betek 41°C evit ar re vrasañ[28]. Implijet o deus ur patrom niverel da jediñ gwrezverk ar c'horf diouzh ar ment hag ar feur kreskiñ, evit 8 spesad, eus Psittacosaurus mongoliensis, 12 kg ennañ, betek Apatosaurus excelsus, 2 6000 kg ennañ. Hervez ar skipailh e tizhe gwrezverk diabarzh Sauroposeidon proteles, ar pounnerañ eus an dinosaored anavet (60 tonenn), betek 48°C moarvat. Prouiñ a rafe ar patrom-se e vefe tommaet an dinosaored bras dre « emwrezadezh anniñvel ».

N'eus ket keit-se e renked Ichthyosauria, Pliosaurus, Plesiosauria (3 strollad stlejviled dour) ha Pterosauraia (stleviled-nij) e strollad an dinosaored ; hiziv e vez sellet oute evel lignezioù disheñvel diouzh an dinosaored.

Ur strollad loened liesseurt e oa an dinosaored. Hervez ur studiadenn eus 2006 e oa bet deskrivet 527 genad asur disheñvel, hag ouzhpenn 1 844 genad a chom c'hoazh da renkañ.[29], [30]

Hervez ar Kod Etrebroadel Rummatadur al Loened[31]Patrom:' [32] e c'haller anavout etre 630 ha 650 genad dinosaored, gant meur a viliadoù spesadoù ; deskrivet e vez war-dro tregont spesad nevez bep bloaz. Un tamm muioc'h evit an hanter eus ar spesadoù n'int anavezet ken gant ur standilhon, diglok peurliesañ, ha nebeutoc'h evit 20% eus ar spesadoù zo anavezet gant muioc'h evit 5 standilhon.

An daolenn hollek da-heul a ro liammoù etre ar strolladoù dinosaored pennañ. Kavout a reor un nebeud genadoù da reiñ un alberz eus an urzhiadoù hag eus ar c'herentiadoù meneget.

Anchisaurus Plateosaurus Massospondylus Sauropoda Sauropoda diazez

Anchisaurus Plateosaurus Massospondylus Sauropoda Sauropoda diazez  Brachiosaurus Camarasaurus Ampelosaurus Ornithischia Heterodontosauridae

Brachiosaurus Camarasaurus Ampelosaurus Ornithischia Heterodontosauridae  Stegosaurus Kentrosaurus Huayangosaurus Ankylosauria

Stegosaurus Kentrosaurus Huayangosaurus Ankylosauria  Trikeratops Protoceratops Torosaurus Ornithopoda Ornithopoda diazez

Trikeratops Protoceratops Torosaurus Ornithopoda Ornithopoda diazez Diwanet eo an dinosaored e-barzh usurzhad ar stlejviled Archosauria, ur strollad stlejviled bihan diapsidek a veve e diwezh ar Permian ha dreist-holl e deroù an Triaseg.

E diwezh ar Permian, war-dro -250 milion a vloavezhioù zo, e voe un enkadenn drumm hag a gasas war-dro 90% eus spesadoù ar mare da get, ar pezh a roas o zu d'ar spesadoù loened ha plant a chome da vleuniañ ha da emdreiñ da c'hounit tachennoù nevez, an amnioted peurgetket. E-touez ar re-se edo hendadoù an dinosaored, ar stlejviled hag ar bronneged a wezhall hag a vremañ.

Ar stlejviled bihan diapsidek, da lâret eo dezho daou goublad prenestradenn en o c'hlopenn, a-drek poulloù o daoulagad, o deus eskern rakdentel e lodenn a-raok o c'harvanoù hag, evel holl stlejviled ar mare-se, izili a-dreuzkiz pe hanter-savet. Anvet int Thecodontia abalamour d'ar c'hentañ perzh-se. Aloubiñ a rejont an holl veteier, ha rannet e vezont e tri c'herentiad bras :

Kigdebrerien eo an dinosaored koshañ a anavezer, etre 225 ha 230 milion a vloavezhioù dezho : Eoraptor ha Herrerasaurus. Arbennikaet eo an daou dija, rak Saurischia int, ur strollad a zo diwanet goude ma savas kemm etre an dinosaored Ornithischia ha Saurischia. Homodontek evel ar stlejviled all eo an holl zinosaored.

Herrerasaurus zo ezel eus an urzhiad Saurischiea, met ivez eus an isurzhiad Theropoda[35].

Anavout a reer roudoù pavioù karrekaet koshoc'h, ha lezet gant dinosaored moarvat. Lezet e oa bet ar re goshañ war-dro 248 milion a vloazioù zo gant « stlejviled bihan pevarzroadek, a vent gant ur c'hazh, a lezas o louc'hoù er pri e-tro 250 milion vloaz zo [...]. Dizoloet e oa ar pazioù-se e mervent Polonia, er menezioù Kroaz-santel. [...] Lezet e oa bet al louc'hoù [...] gant stlejviled eus ar genad Prorotodactylus, loened pevarzroadek dezho pemp biz, ha sanket donoc'h eo louc'h an tri biz kreiz el leur. Tost an eil re diouzh ar re all, ar roudoù-se zo disheñvel diouzh re stlejviled all eus strollad ar c'hrokodiled hag ar stlejviled ». [36]Patrom:'[37]

« 246 milion a vloavezhioù eo oad roudoù all bet kavet gant [...] skipailh Grzegorz Niedzwiedzki eus Skol-Veur Warszawa. Brasoc'h int, war-dro 15 kantimetr, ha lezet e vijent bet gant dinosaored eus ar genad Sphingopus daoudroadek[36] ». Ar roudoù-se a laka moarvat ar c'hentañ spesad dinosaored hep kemm etre Ornithischia ha Saurischiea da vevañ un nebeud milionoù a vloavezhioù abretoc'h, da lâret eo adalek diwezh ar Permian.

Steuzidigezh an Triaseg-Juraseg en deus roet an tu d'ar spesadoù nevez-se da baotañ ha da gemer al logoù ekologel dieub.

Steuzidigezh an dinosaored, war-dro 65 milion a vloavezhioù zo, he deus lakaet an dud da sevel meur a vartezeadenn d'he displegañ abaoe ar bloavezhioù 1970, lod anezhe droch-pitilh evel distruj an dinosaored gant arallvediz, lod gwirheñveloc'h hag a c'haller gwiriañ en un doare skiantel. Ret eo derc'hel soñj avat ez eo « steuzidigezh an dinosaored » un doare da gaozeal ha netra ken : n'eo ket aet an dinosaored da get penn-da-benn peogwir e chom evned c'hoazh hiziv an deiz.

Daoust da se ez eus bet un enkadenn veur e diwezh ar C'hretase, 65 milion a vloavezhioù zo. Honnezh avat he deus bet un efed bihanoc'h war ar vevliesseurted dre vras evit enkadenn veur ar Permian-ha-Triaseg pe zoken hini an Ordovisian) ; diouennet he deus loened ha plant mor dreist-holl, evel ar skourrad Foraminifera, pe an isurzhiad Ammonoidea, ha pas kement a organegoù hag a veve war an douar. Kalz izeloc'h eo feur ar spesadoù douar-se a ya da get evit hini ar spesadoù-mor. Abalamour da donkad an dinosaored avat ez eo deuet an enkadenn-se da vezañ brudet.

Setu amañ abegoù gwirheñvelañ an enkadenn K-T.

E miz Gwengolo 2007, ur skipailh klaskerien amerikan renet gant William Bottke eus ar Southwest Research Institute e Boulder, Colorado, ha skiantourien dchek a implijas drevezadennoù dre urzhiataer da c'houzout eus pelec'h e teue an asteroidenn he doa krouet krater Chicxulub. Jedet o deus gant 90% gwirheñvelder e oa bet darc'haouet war-dro 160 milion a vloavezhioù zo un asteroidenn ramzel anvet (298) Baptistina, dezhi tro 170 km treuzkiz, e kelc'htro e gourizad asteroidennoù a zo etre Meurzh ha Yaou, gant un asteroidenn vihanoc'h ha dizanv dezhi 55 km treuzkiz. Drailhet e voe (298) Baptistina gant ar stokadenn, ha krouet e voe ur strollad asteroidennoù anvet « tiegezh Baptistina ». Hervez ar jedadennoù, lod eus an drailhennoù a oa kaset e kelc'htroioù a dreuze hent an Douar. Unan anezhe e oa ar maen-kurun 10 km led a skoas ledenez Yucatán 66 milion a vloavezhioù zo[41]

Diazezet eo an teir damkaniezh-se war fedoù solut hag enkadenn veur ar C'hretase a c'hallfe bezañ c'hoarvezet goude degouezh an tri darvoud-se d'ar memes mare.

E 1861 e voe kavet e Bavaria ar garrekaenn evn gentañ, Archaeopteryx, ur spesad eus ar Juraseg uhelañ. Dre ma oa heñvel-kenañ ouzh an dinosaored bihan daoudroadek, evel Compsognathus, ec'h anadas diouzhtu an damkaniezh e tiskenne al laboused eus ur strollad dinosaored e-touez ar c'hlad Cœlurosauria.

E-pad ur c'hantved e voe ur rendael diwar-benn an damkaniezh-se, a voe distaolet gant lod klaskerien. Ibilioù-skoaz zo d'an evned, emezo, padal n'eus ket da Cœlurosauria. Re a bouez a voe roet da ezvezañs an ibiloù-skoaz, koulskoude, pa n'eus reoù ebet d'ar bronneged kigdebrerien, n'int stlejviled evit kement-se.

Abaoe ar bloavezhioù 1970 ez eus bet kavet Cœlurosauria gant ibiloù-skoaz, ha zoken e strolladoù na oant ket emdroet ken : trec'h war ar re all e voe damkaniezh an dinosaored hendadoù d'an evned.

Er bloavezhioù 1990 e voe kavet kalz karrekaennoù dinosaored pluñvek e Sina, e bro Liaoning ; kreñvaet o deus an damkaniezh-se. A-wezhioù ez int evned kentidik, hag a-wezhioù dinosaored pluñvek pe kentpluñvek ha na oant ket evned.

Abalamour d'an dizoloadennoù-se e soñjer e tiorroas perzh nevez ar pluñv en unan pe e meur a spesad Cœlurosauria, en hendad ar C'hœlurosauria e-unan zoken, hep implijout anezhañ da nijal war a seblant, hag engehentet en deus spesadoù niverus a-walc'h a zinosaored pluñvek. Diwar unan eus ar spesadoù dinosaored pluñvek-se e vije diwanet hendad an holl laboused, meur a vilion a vloavezhioù diwezhatoc'h.

Petra bennak ma'z eo degemeret an damkaniezh-se gant ar pep brasañ eus ar skiantourien ez eus un nebeud klaskerien a sav a-enep c'hoazh.

Kalz stlejviled a veve d'ar memes mare hag an dinosaored, ha kemmesket int bet gante er sinema hag el lennegezh, daoust ma n'int renket evel-se gant ar skiantourien : Pterosauria ("stlejviled-nij", en o zouez Pteranodon ha Pterodactylus), Plesiosauria, Pliosauridae, Mosasauridae hag Ichthyosauria (stlejviled mor) eo ar re vrudetañ.

An dinosaored (Dinosauria o anv skiantel) zo loened eus klad ar Sauropsida, a vod an holl stlejviled a-vremañ (ar gevrennad Reptilia), an holl evned a-vremañ (ar gevrennad Aves) hag ul lodenn hepken eus an henstlejviled, an holl anezho o tiskenn eus un hendad hepken. Kalz spesadoù dinosaored a oa, liesseurt ha disheñvel-kenañ an eil re diouzh ar re all. Ar re vrudetañ a vevas adalek diwezh an Triaseg (-251 milion a vloavezhioù/Mav) betek fin ar C'hretase (-65,5 Mav), e-pad an oadvezh Mezozoeg pe Eil hoalad (-251 Mav – -65,5 Mav).

Kavadennoù graet nevez zo a laka da soñjal ez eus bet dinosaored abaoe an Triaseg Izel (deroù : -251 Mav) pe an Triaseg Kreiz (diwezh : -228 Mav), pe zoken adalek ar Permian (-299 Mav – -248 Mav). Trevadennet eo bet an holl gevandiroù gant an dinosaored abalamour ma ne oa ket dispartiet c'hoazh ar c'hevandir nemetañ, Pangea e anv, da vare an Triaseg, ha ma'z int en em strewet dre-holl d'ar mare-se hep kaout ezhomm da dreuziñ mor ebet.

Abred pe abretoc'h eo aet an holl zinosaored da get – war-bouez an evned – e-kerzh ar Mezozoeg ; e-pad enkadenn ar C'hretase hag an Trede hoalad (anvet ivez « enkadenn K-T ») ez eo steuziet an dinosaored a veve da vare ar C'hretase uhel (-99,6 Mav – -65,5 Mav).Patrom:'

E miz Ebrel 1842 e voe kinniget an anv dinosaor gant ar paleontologour saoz Richard Owen (1804-1892), diwar an henc'hresianeg saura "glazard, stlejvil" ha deinos "spontus, braouac'hus" abalamour ma oa bras-kenañ (en tu all da 15 m) ar pep brasañ eus an dinosaored a oa bet dizoloet gantañ. Daoust d'an dra-se e c'halle an dinosaored bezañ bihan-kenañ o ment, betek un nebeud kantimetroù.

Kerkent ha kreiz an XIXvet kantved ha betek ar bloavezhioù 1970, an dinosaored a veze gwelet gant ar skiantourien evel loened yen o gwad, dizampart ha goustad, aet da get abalamour d'o sotoni. E 1969, ar paleontologour stadunanat John Ostrom (1928-2005) a roas lañs da « azginivelezh an dinosaored », a sachas evezh ur bern tud war studi an dinosaored, a voe gwelet adalek neuze evel loened oberiant, emwrezek gant emzalc'hioù kevredigezhel kemplezh.

Abaoe ma voe anavezet ar c'hentañ dinosaor, en XIXvet kantved, al loened-se o deus desachet ur bern tud er mirdioù e pep lec'h war an Douar, da welet ar relegoù adsavet eno. Plijout a reont kenañ d'ar vugale koulz ha d'an oadourien. Deuet int da vezañ ul lodenn eus sevenadur pobl an XXvet hag an XXIvet kantved, hag o c'havout a reer taolennet e levrioù hag e filmoù stank-kenañ. Danvez pennañ levrioù ha filmoù brudet ez int, evel Jurassic Park pe Ice Age 3, ha kaoz a vez ingal eus ar c'havadennoù nevez diwar o fenn er media.

Alies e vez implijet ar ger "dinosaor" war ar pemdez evit komz eus stlejviled all eus ar ragistor, evel ar genadoù Dimetrodon, Ichthyosaurus, Mosasaurus, Plesiosaurus ha Pterosaurus, petra bennak ma ne oa ket dinosaored anezho tamm ebet.

Ymlusgiaid sydd wedi darfod o'r tir, rhai ohonynt yn meddianu corff enfawr, yw deinosoriaid. Roedd y deinosoriaid cyntaf yn byw tua 210 miliwn o flynyddoedd yn ôl, ond amryfalasant yn gyflym ar ôl y cyfnod Triasig. Roeddent yn fwyaf niferus yn ystod y cyfnodau Jwrasig (ee Stegosaurus) a Chretasaidd, ond wedi'r cyfnod Cretasaidd diflanodd pob rywogaeth ohonynt, heblaw am y rheini a ddatblygodd i fod yn adar, yn ystod y Difodiant Cretasaidd-Paleogen tua 65 miliwn o flynyddoedd yn ôl.

Defnyddiodd Richard Owen, gwyddonydd a hanai o Gymru, y gair Dinosauria yn gyntaf ym mlwyddyn 1842. Mae'r gair hwn yn gyfuniad o'r geiriau Groegaidd deinos ("ofnadwy" neu "arswydus") a sauros ("genau-goeg" neu "ymlusgiad"). Enwyd un rhywogaeth ar ôl Richard Owen, tad y deinosoriaid, sef yr Owenodon.

Ar wahân i Richard Owen, ceir llawer o baleontolegwyr eraill yng Nghymru a ystyrir o bwys mawr, gan gynnwys Dorothea Bate a aned yn Sir Gaerfyrddin, y ferch gyntaf i weithio yn Natural History Museum, Llundain.

Dim ond mewn creigiau a gafwyd eu ffurfio yn y cyfnodau Triasig a'r Jurasig y ceir olion deinororiaid, ac mae'r rhan fwyaf o greigiau drwy Gymru yn llawer hŷn na hynnny ac felly wedi eu ffurfio cyn oes y Deinosoriaid. Ond fe'i ceir mewn un rhan yn y de - rhwng Porthcawl a Phenarth, ond prin iawn ydy'r olion:

Mae'r darganfyddiadau hyn o bwysigrwydd bydeang, nid oherwydd y nifer, ond gan fod y darganfyddiadau'n eitha cyflawn, ymlusgiaid wedi'u cadw a'u prisyrfio yn dda. Anifeiliaid bychan ydyn nhw i gyd, a gellir eu dychmygu'n ceisio dianc oddi wrth rai mwy.[1]

Ymlusgiaid sydd wedi darfod o'r tir, rhai ohonynt yn meddianu corff enfawr, yw deinosoriaid. Roedd y deinosoriaid cyntaf yn byw tua 210 miliwn o flynyddoedd yn ôl, ond amryfalasant yn gyflym ar ôl y cyfnod Triasig. Roeddent yn fwyaf niferus yn ystod y cyfnodau Jwrasig (ee Stegosaurus) a Chretasaidd, ond wedi'r cyfnod Cretasaidd diflanodd pob rywogaeth ohonynt, heblaw am y rheini a ddatblygodd i fod yn adar, yn ystod y Difodiant Cretasaidd-Paleogen tua 65 miliwn o flynyddoedd yn ôl.

Defnyddiodd Richard Owen, gwyddonydd a hanai o Gymru, y gair Dinosauria yn gyntaf ym mlwyddyn 1842. Mae'r gair hwn yn gyfuniad o'r geiriau Groegaidd deinos ("ofnadwy" neu "arswydus") a sauros ("genau-goeg" neu "ymlusgiad"). Enwyd un rhywogaeth ar ôl Richard Owen, tad y deinosoriaid, sef yr Owenodon.

Dinosauři (z řec. δεινός - deinos + σαῦρος- sauros = „strašný ještěr“, někdy překládáno „hrozný plaz“) jsou skupina živočichů tradičně řazená mezi plazy, která dominovala živočišné říši na suché zemi přes 134 milionů[1] let v období druhohor (zejména v jurské a křídové periodě, asi před 201 až 66 miliony let). Nicméně dinosauři jsou mnohem podobnější a příbuznější ptákům, a proto není zařazování mezi plazy správné a odborníci je mezi plazy neřadí. Ptáci jsou dle současné systematiky jednou z mnoha dinosauřích skupin.[2] Dinosauři se objevili ve středním nebo na počátku svrchního triasu (po permském vymírání) asi před 250-235 miliony let[3][4] a vyhynuli (kromě jedné větve – ptáků) před 66,0 miliony let v rámci vymírání na konci křídy. Jejich evoluční radiace byla velmi rychlá.[5][6] Vyvinuli se pravděpodobně na pevninách jižního superkontinentu Gondwany[7] (téměř s jistotou to bylo na jihu dnešní Jižní Ameriky)[8] a k jejich evolučnímu rozkvětu došlo poprvé v době před asi 234 až 232 miliony let.[9][10][11] Veškeré informace o dinosaurech dnes máme k dispozici pouze ze zachovaných fosílií. Ptáci jsou ve skutečnosti pokračovatelé evoluční linie plazopánvých dinosaurů (theropodů, což byli masožraví dinosauři, kteří chodili po dvou a měli ptačí znaky. Jako například duté kosti, plicní vaky, esovité krky a často i peří jako tělesný pokryv, jak v posledních dvaceti letech dokázaly intenzivní výzkumy. Podle některých paleontologů (Robert T. Bakker, John Ostrom, Jacques Gauthier atd.) jsou pak ptáci přímo malí, agilní dinosauři (důkazem pro tuto teorii je třeba objev opeřených dinosaurů v oblasti Liao-ning i jinde). Proto navrhli vyčlenit dinosaury úplně ze třídy Reptilia (plazi) a zahrnout je společně s ptáky do nové třídy Dinosauria. Každopádně jde však o monofyletickou skupinu se společným předkem. Dinosauři jsou každopádně přirozenou skupinou vývojově velmi úspěšných obratlovců.[12]

Dnes již je však důležitější kladistika nežli přesné určování vnějších taxonových kategorií, proto se touto problematikou zabývá jen málokdo. Za dinosaura je podle definice považován jakýkoliv živočich, který je přímým potomkem posledního společného předka iguanodona a megalosaura (někdy se také pro tento účel „využívá“ známějších rodů Tyrannosaurus a Triceratops).

Dinosauři patří mezi nejúspěšnější skupiny suchozemských obratlovců v dějinách života na Zemi. Zcela dominovali suchozemským ekosystémům v období jury a křídy, tedy celkem asi 134 milionů let. V době jejich existence nedosáhl žádný jiný suchozemský živočich (s výjimkou sladkovodních krokodýlů a ptakoještěrů) rozměrů přesahujících velikost jezevce.[13] Je pravděpodobné, že pokud by dinosauři nevyhynuli, savci by se evolučně rozvíjeli pomaleji a člověk by se možná objevil až mnohem později (pokud vůbec). Přesto jsou dosud dinosauři v mnoha ohledech vnímáni jako symbol čehosi zpátečnického a neschopného změny (například pojem "politický dinosaurus"). Takový pohled je však absurdní.[14]

Dinosauři patří mezi diapsidní živočichy – mají dva spánkové otvory na upevnění žvýkacích svalů. Dalším typickým znakem, který odlišuje dinosaury od většiny ostatních plazů, je postavení končetin. Specialitou je tzv. čtvrtý trochanter, sloužící k upnutí mohutných kaudofemorálních svalů. Ty pomáhaly při pohybu zadních končetin, které stahovaly dozadu.[15] U současných plazů jsou končetiny postaveny směrem do stran (např. krokodýli), zatímco dinosauří končetiny směřují přímo pod tělo (jako u savců). Přední končetiny byly obvykle kratší než zadní. Další významný znak je zvláštní stavba zadních končetin. Stehenní kost byla opatřena kulovitou hlavicí, která zapadala do pánevní jamky a umožňovala svislé umístění končetiny. Lýtková kost (fibula) byla na vnější straně mnohem tenčí než holenní kost (tibia) na straně vnitřní. Kyčelní jamka (acetabulum) byla charakteristicky perforovaná.[16] Dinosauři měli zuby zasazeny v jamkách, podobně jako krokodýli, u plazů vyrůstají zuby přímo z čelistní kosti. Dinosauří páteř byla tvořena různým počtem obratlů, které byly mnohdy duté a vyplněné vzdušnými vaky (plazopánví). Žebra byla připojena dvěma kloubními hlavicemi.

Stejně jako ostatní plazi byli dinosauři vejcorodí (přestože se již objevily teorie o živorodosti některých druhů). Jejich vejce však nebyla kožovitá, ale měla pevnou skořápku inkrustovanou minerálními látkami, podobně jako vejce dnešních ptáků.

Výzkum L. Witmera z roku 2008 prokázal, že většina dinosaurů měla zřejmě odlehčené lebky a ty byly do značné míry vyplněné vzdušnými dutinami.[17] Výzkum z roku 2018 dokládá, že výrazné změny na pánevních kostech některých skupin dinosaurů (například maniraptorů a ptakopánvých) souvisejí zejména s dýchacím systémem a nikoliv s přechodem k herbivorii, jak se mnozí paleontologové domnívali dříve.[18]

Kůže byla často pokrytá peřím nebo proto-peřím a ti dinosauři, kteří v evoluci o peří přišli, měli tlustou kůži podobně jako dnešní sloni. U některých druhů, zejména velkých býložravců, se vyvinuly mohutné kostěné pláty. Existovali také četní opeření dinosauři, ze kterých se později, někdy během jurského období, vyvinuli praví ptáci. V současnosti známe kolem dvaceti druhů malých dravých teropodů s pernatým integumentem (pokryvem těla), téměř všechny pocházejí z provincie Liao-ning v Číně. Nicméně se nedokonalé proto-peří objevilo i u některých býložravých dinosaurů. Peří známe jak u plazopánvých, ale protopeří i u ptakopánvých. Jelikož nejmladší spoječný předchůdce plazopánvých a ptakopánvých žil ve stejné době jako první dinosauři, je velmi pravděpodobné, že první dinosauři byli opeření, co znamená, že peří je pravděpodobně znakem dinosaurů, podobně jako srst je znakem savců a podobně jako někteří savci ztratili srst, tak někteří dinosauři ztratili peří. Možná se tedy u předka všech dinosaurů objevilo ještě v triasu nebo se u dinosarů peří objevilo několikrát nezávisle na sobě, první verze je však mnohem pravděpodobnější.

Ačkoliv současní ptáci jsou přímými potomky teropodních dinosaurů (resp. jsou sami přežívajícími teropodními dinosaury), ani v případě druhotně nelétavých druhů jejich mozky nejsou neurofyziologickým ekvivalentem mozků druhohorních dinosaurů.[19] V současnosti se již paleontologové shodují na závěru, že ptáci vznikli v průběhu jurské periody z opeřených teropodních dinosaurů.[20]

Dinosauři ze skupiny Sauropoda představovali největší suchozemské živočichy všech dob. Někteří snad mohli dosáhnout délky až kolem 40 metrů (avšak jedná se o nejisté fosilní objevy), tedy zhruba o 10 metrů více, než dosahují největší velryby!) a hmotnosti až přes 100 tun. Výrazně těžší je pouze jediný žijící druh kytovce – plejtvák obrovský.[21] Zatím největším relativně dobře známým dinosaurem je rod Argentinosaurus, u něhož se předpokládá hmotnost zhruba 70–90 tun. Vážil tedy asi tolik, jako 15 dospělých slonů. Podobně velký byl i Puertasaurus. Některé izolované obrovské kosti naznačují existenci ještě větších dinosaurů (viz např. Amphicoelias – pravost Copeova nálezu je sporná, neboť jediný nalezený obratel byl ztracen). V současnosti je známo asi osm sauropodů, jejichž hmotnost podle odhadů přesahovala 60 metrických tun.[22] Na druhou stranu však existovali i velmi drobní dinosauři (např. dromeosauridi Microraptor nebo Epidendrosaurus, který je však často řazen k Avialae, tedy již k „ptačím dinosaurům“ do čeledi Scansoriopterygidae, jejíž validita je diskutabilní), kteří dosahovali velikostí jen v řádu desítek centimetrů a stovek gramů. Nejmenším známým druhem teropodního dinosaura je podle moderní systematiky kolibřík kalypta nejmenší (Mellisuga helenae) s průměrnou délkou těla kolem 6 centimetrů a hmotností kolem 2 gramů.[23]

Z důvodu nekompletnosti fosilního materiálu a skutečnosti, že nikdy nenalezneme skutečného rekordmana, nelze brát tabulky rekordů zcela vážně. Jsou zde nicméně indicie (znalost blízkých příbuzných, biomechanické studie), které nám dovolují byť přibližně určit délku, výšku či hmotnost zvířete. Dle těchto indicií by pak k nejdelším dinosaurům mohl patřit severoamerický rod Maarapunisaurus fragillimus s délkou kolem 32 metrů. K dalším obrům patřily rody Bruhathkayosaurus s odhadovanou délkou až kolem 44 metrů (u tohoto rodu je však možné, že se jedná o zkamenělý kmen stromu)[24], Puertasaurus s 35–40 m, Argentinosaurus s 30–37 m, Turiasaurus 30–39 m (dosud největší suchozemský živočich, jaký kdy byl na evropském kontinentu nalezen), Supersaurus s 35 m–?40 m, Sauroposeidon s 29–34 m (s výškou snad 18 metrů nejvyšší dosud známý dinosaurus), „Seismosaurus“ s 33–35 m, Paralititan s 26–35 m, Antarctosaurus s až 40 m nebo Argyrosaurus s 18–30 m.[25]

Největší draví dinosauři (teropodi) představují společně s některými zástupci krokodýlů zároveň největší suchozemské dravce všech dob. Dlouhou dobu držel primát rekordního predátora známý severoamerický Tyrannosaurus, v 90. letech minulého století ho však překonal argentinský obr Giganotosaurus, který měřil na délku kolem 13 metrů a vážil snad až kolem 8 tun. Ani tento teropod však zřejmě nebyl největší, jak potvrzují nedávné nálezy. Dnes je držitelem velikostního primátu mezi teropody Spinosaurus, vědecky popsaný již roku 1915.

K nejdelším teropodům patřil severoafrický rod Spinosaurus, jež se svými 16–18 metry neměl v dospělosti žádného přirozeného nepřítele (nepočítáme-li příslušníky stejného druhu).[26] Šlo však o velmi specializovanou formu dravého dinosaura, uzpůsobenou na lov ryb ve vodním prostředí. V závěsu za ním je pak rod Giganotosaurus s 13,5–13,7 m, Tyrannotitan s 13,4 m, Deltadromeus s 13,3 m, Mapusaurus s 12,8 m, Tyrannosaurus s 12,5 m nebo Carcharodontosaurus s 11,1–13,5 m. Tyto údaje jsou však pouze přibližné a v budoucnu nejspíš dojde k jejich revizi.

Za nejinteligentnější se obecně považuje menší teropod druhu Troodon formosus ze svrchní křídy USA a Kanady, jehož encefalizační kvocient (EQ – vyjadřující poměrnou velikost mozku k tělu oproti stejně těžkému krokodýlovi) činil až 6,5. Troodon byl tak zřejmě stejně inteligentní jako dnešní šelmy a někteří ptáci (a mnohem inteligentnější než dnešní plazi). Nedávno byl však změřen objem mozkovny jiného malého svrchnokřídového teropoda druhu Bambiraptor feinbergi (objeven v roce 1995 v Montaně, USA). Výsledek odpovídá téměř dvojnásobku hodnoty u troodonta (EQ 12,5–13,8). Navíc bylo zjištěno, že tento dinosaurus používal „vratiprst“ a mohl tedy možná manipulovat s předměty (na druhou stranu však šlo ještě o mládě, u kterého je mozkovna relativně větší v poměru k tělu). Porovnáváme-li EQ neptačích dinosaurů s ptáky, vyjde nám většinou hodnota 0,05 až 1,4. Vůbec nejinteligentnějšími dinosaury jsou zřejmě dnešní vrány (konkrétně vrána novokaledonská, která se pozná v zrcadle a používá jednoduché nástroje). Většina dinosaurů (především býložravých) však zřejmě příliš vysoké inteligence nedosahovala.[27]

Celkový vzhled hraje v životě zvířete velkou roli. Je nejen důležitou součástí sexuálního výběru, ale často slouží i jako ochrana proti predátorům, po případě jako maskovací úbor lovců. Dinosauři byli zpočátku představováni jako šedí tvorové bez jakýchkoli výrazných barevných znaků. Nicméně není důvod tento názor považovat za prokazatelný fakt. Stejně jako i dnešní fauna, byli zcela jistě i dinosauři barevnými živočichy. Vzhledem ke skutečnosti, že se nikdy nedozvíme, jakými barvami tito diapsidní plazi oplývali, lze na toto téma pouze spekulovat. Různorodost zbarvení záležela na způsobu života daného druhu. Zvíře žijící v lesích se z důvodu maskování jistě lišilo od tvorů obývajících volná prostranství. Pestrost byla určitě výhodou i během námluv, kdy si samice vybraly jedince, kteří jim nejvíce imponovali. Vzhledem k přítomnosti peří u mnoha druhů dinosaurů je předpoklad zbarvení velmi pravděpodobný. Počátkem roku 2010 bylo vědci oznámeno, že byly objeveny molekuly pigmentů (původních barviv) v primitivním peří neptačích teropodních dinosaurů rodu Sinosauropteryx, Anchiornis, Caudipteryx a snad i některých dalších. Jedná se o historicky vůbec první příležitost, kdy byla identifikována barva neptačího dinosaura. Dnes již známe barvu u šesti druhů druhohorních teropodů – Sinosauropteryx, Anchiornis, Microraptor, Sinornithosaurus, Archaeopteryx a Confuciusornis[28].