en

names in breadcrumbs

Pumpkin toadlets are one of the smallest extant anuran species known. Body length ranges from 12.5 to 19.7 mm, with an average of 18 mm. Skin coloration of pumpkin toadlets is typically bright yellow to orange, with tiny wart-like bumps along the dorsum. Their eyes are rounded and completely black. Pumpkin toadlets have four digits on their front appendages, but only three are functional. Similarly, they have five digits on their hind limbs, but only four are functional. Reduced functional digits is specific to brachycephalids. In addition, these species have very short appendages, making them very low to the ground. In addition, like other true toads, pumpkin toadlets lack teeth, instead using dermal bones and strong jaw muscles to eat small insects. Little to no sexual dimorphism is evident. Juvenile pumpkin toadlets have a small vestigial tail that adult toadlets lack. Pumpkin toadlets show direct development, skipping the tadpole stage.

Brachycephalus ephippium have been found to produce traces of tetrodotoxin, a potent neurotoxin, which presumably evolved as a predator defense mechanism. The skin has the highest levels of this tetrodotoxin, followed by the liver and ovaries.

Range length: 12.5 to 19.7 mm.

Average length: 18 mm.

Other Physical Features: ectothermic ; heterothermic ; bilateral symmetry ; poisonous

Sexual Dimorphism: sexes alike

Pumpkin toadlets deter potential predators with their bright orange aposematic coloration, which serves as a warning that they are toxic. Considerably high concentrations of tetrodotoxin, a neurotoxin with no antidote, can be found in the skin and liver. Hiding in and under leaf litter and logs also reduces predation. Major predators include ground foraging birds, such as rusty-margined guans or solitary tinamous. When approached by a potential predator, pumpkin toadlets emit a high pitched call to warn conspecifics and to scare off the intruder. If calls do not deter a potential predator, males may move their forearms up and down over one of their eyes as additional warning sign. Males use these techniques only if a potential predator approaches their territory or if they feel threatened. Females have the same bright skin tone and tetrodotoxin, and use calls as warning signals.

Known Predators:

Anti-predator Adaptations: aposematic

Brachycephalus ephippium communicates in a number of different ways, both with con- and heterospecifics. Their vivid yellow-orange coloration warning serves as a warning sign to potential predators that they are toxic. The bright color, easily spotted along the rainforest floor, is also used as a means of visual communication for other pumpkin toadlets to conveniently locate one another. Male pumpkin toadlets use visual and vocal signals more frequently than females. Males produce an “advertisement call”, alerting conspecifics of their presence. This loud buzzing call lasts from two to six minutes. When approached by a potential rival, male pumpkin toadlets produce high-pitched vocalizations, along with repeated movements of its forelimbs up-and-down over its eyes. Males also whip their head with their limbs as a means of welcoming another pumpkin toadlet into their territory. Finally, males always travel directly behind females in an effort to offer protection and to convey dominance to rival males.

Communication Channels: visual ; tactile ; acoustic

Perception Channels: visual ; acoustic

There is no information available regarding the lifespan of pumpkin toadlets. However, frogs in the suborder Neobatrachia have a lifespan ranging from 4 to 6 years in the wild. In captivity, they can survive 10 to 12 years.

Brachycephalus ephippium is found in both primary and secondary montane forests that tend to be warm and humid. It is most often found between 700 and 1200 m in elevation and tends to avoid open areas, remaining on the leaf-covered forest floor. During the dry season, B. ephippium finds shelter under logs and branches. During the rainy season, which occurs from mid-October through March, males become highly aggressive. Individuals can be seen above the litter, during the wet season, searching for mates.

Range elevation: 700 to 1200 m.

Habitat Regions: tropical ; terrestrial

Terrestrial Biomes: forest ; mountains

Aquatic Biomes: coastal

Brachycephalus ephippium, the pumpkin toadlet, has a highly restricted distribution in South America. Pumpkin toadlets are native to neotropical rainforests along the Atlantic coast of southeastern Brazil. Their range extends from northern areas of Bahia, in eastern Brazil, south to São Paulo.

Biogeographic Regions: neotropical (Native )

Pumpkin toadlets are carnivorous and forage under leaf litter for potential prey. Their diet consists mostly of small arthropods, especially springtails. They also feed on insect larvae and mites found on the rainforest floor. Juveniles feed on the same insects and small arthropods as adults.

Animal Foods: insects; terrestrial non-insect arthropods

Primary Diet: carnivore (Insectivore , Eats non-insect arthropods)

Pumpkin toadlets are insectivorous, feeding primarily on springtails and small insects, such as mites. As a result, they may help control certain insect pest species throughout their geographic range. Due to the presence of tetrodotoxin throughout their bodies, pumpkin toadlets have relatively few predators. There is no information available regarding parasites of this species.

Pumpkin toadlets are sometimes sold as pets. In addition, the tetrodotoxin they produce as an antipredator defense is currently being researched for potential medicinal use. As an amphibian, pumpkin toadlets are likely good indicators of habitat quality throughout their geographic range.

Positive Impacts: pet trade ; research and education

Tetrodotoxin, which is found throughout the body of pumpkin toadlets, is a neurotoxin with no antidote that can be harmful to animals, including humans. This neurotoxin is a known hallucinogenic and can cause great damage to the lungs, muscles, and nervous system, if ingested. Tetrodotoxin decreases blood pressure, which can lead to cardiac arrest. This same toxin can also be found in longspined porcupinefish and in numerous other marine species.

Negative Impacts: injures humans (poisonous )

Pumpkin toadlets have a unique development pattern in that they bypass the tadpole stage. Embryos have a yolk sac, from which development begins. Around the 25th day of development, pumpkin toadlets begin to show evidence of a small mouth and large tail. On the 41st day, the embryo develops phalanges, along with two egg teeth near the end of the rostrum. By the 54th day, young pumpkin toadlets have light skin pigment, a noticeably shorter tail, and only one egg tooth remaining for use during hatching. Eggs hatch in a 64-day cycle in the rainforest leaf litter. Typically, only 5 pumpkin toadlets hatch together. After hatching, they no longer possess an egg tooth and have acquired a dark-brownish color. Young pumpkin toadlets become independent directly after hatching. For a short period after hatching, toadlets retain a short vestigial tail. Newly hatched toadlets average 5.25 mm to 5.45 mm long. As they mature, coloration changes to orange-yellow and functional digits are reduced from 3 to 2 working fingers and from 4 to 3 functional toes. Age of sexual maturity is not known for pumpkin toadlets.

Development - Life Cycle: metamorphosis

Pumpkin toadlets are classified as a species of least concern on the IUCN's Red List of Threatened Species and is abundant throughout its limited geographic range. Major threats include extensive habitat loss due to agricultural expansion, deforestation, human settlement and tourism.

US Federal List: no special status

CITES: no special status

State of Michigan List: no special status

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: least concern

Breeding in pumpkin toadlets is polygynandrous and occurs throughout the rainy seasons. Males attract mates using a combination of vocal and visual displays. Males take on a larger and more upright posture, due to their enlarged vocal sack. They release a long buzzing call, which lasts from 2 to 6 minutes and ranges in frequency from 3.4 to 5.3 kHz. The first notes in the call consist of 5 to 6 pulses and increase to as many as 15 pulses. Forests where pumpkin toadlets live are generally quiet, and the pitch of the male call is lower than rustling leaves. When approached by a female, males often move their arm up and down over their eye. Visual displays for attracting mates are more common when other males are present and in loud environments. When a female approaches, she chooses the site of oviposition, typically in the leaf litter or under a log, while the male follows close behind. The male then shifts from an inguinal to auxiliary position to maximize fertilization. After about 30 minutes, five yellow-white eggs are deposited, which range in size from 5.1 to 5.4 mm in diameter. The male then leaves the site while the female presses and rolls the eggs in soil using her hind legs, camouflaging the eggs. After the eggs are camouflaged, they are left unattended to develop and hatch on their own.

Mating System: polygynandrous (promiscuous)

Pumpkin toadlets breed during the rainy season in southeast Brazil, which usually occurs between mid-October and March. During this time, males are highly aggressive. Reproduction is oviparous, and eggs take about 64 days to hatch. During this time, eggs are kept hidden from predators and sunlight under logs or leaf litter. Brachycephalids, also known as saddleback toads, exhibit a number of unique breeding characteristics. For example, they undergo direct fertilization, in which eggs hatch as miniature toadlets, and the tadpole stage is completely bypassed. Another difference is their method of amplexus. When a male first mounts a female, it is in an inguinal position, where the male holds the female around her waist. He later moves to an axillary position, where he grabs the female above her arms. This most likely is to increase fertilization. This use of more than one mating position is uncommon among anurans.

Breeding interval: Pumpkin toadlets breed once yearly during the rainy season.

Breeding season: Pumpkin toadlets breed during the rainy seasons, which occurs from mid-October through March.

Average number of offspring: 5.

Average time to hatching: 64 days.

Average time to independence: 0 minutes.

Key Reproductive Features: iteroparous ; seasonal breeding ; gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); sexual ; oviparous

After fertilization, the male pumpkin toadlets leave the breeding site. Typical clutch size is five eggs. Once eggs are laid, the female diligently works with her hind legs, kicking and rolling the eggs in the soil to cover them. This not only helps to camouflage the eggs from potential predators, but protects them from sunlight as well; however, decause reproduction occurs during the rainy season, sunlight is not a major problem. Females also ensure that eggs are laid under a log or in leaf litter, for further protection. Toadlets are independent upon hatching and usually remain in the area in which they are born.

Parental Investment: no parental involvement; pre-fertilization (Provisioning, Protecting: Female); pre-hatching/birth (Provisioning: Female, Protecting: Female); inherits maternal/paternal territory

The pumpkin toadlet (Brachycephalus ephippium), or Spix's saddleback toad, is a small and brightly coloured species of frog in the family Brachycephalidae. This diurnal species is endemic to southeastern Brazil where it is found among leaf litter on the floor of Atlantic rainforests at an altitude of 200–1,250 m (660–4,100 ft).[2] It is found in Espírito Santo, Rio de Janeiro, southeastern São Paulo and southeastern Minas Gerais. Although its type specimen supposedly was collected in Bahia about 200 years ago, there are no confirmed localities in this state and recent reviews consider it more likely that it was from Rio de Janeiro.[2][3] B. ephippium is locally common,[3] quite widespread compared to most other species of Brachycephalus and it is not considered threatened.[1][2]

B. ephippium feeds on tiny invertebrates and breeding is by direct development, with the female laying a few eggs on land that hatch into young toadlets (no tadpole stage).[4]

B. ephippium is a very small frog with a snout–to–vent length of 12.5–19.7 mm (0.49–0.78 in) in adults,[5] but it is among the largest in its genus together with species like B. darkside, B. garbeanus and B. margaritatus.[6][7] Females tend to be larger than males.[3] When newly hatched B. ephippium typically measure just 5.25–5.45 mm (0.207–0.215 in).[4]

B. ephippium is overall bright yellow-orange and this is considered aposematic (warning colours) since its skin and organs contain tetrodotoxin and similar toxins.[8] Newly hatched B. ephippium are well-camouflaged and brown overall.[4] 11-oxoTTX (11-oxotetrodotoxin), an isolated analogue is extremely rare to be found in other animals, even marine animals, this analogue is considered four to five times more potent than the tetrodotoxin itself.[9] Other analogues isolated of this toad include the tetrodonic acid, 4-epipetrodotoxin, 4.9 anhydrotetrodotoxin and 11-nortetrodotoxin.[10] The toxins can be found in their skin and ovaries, but mostly concentrated in the liver.

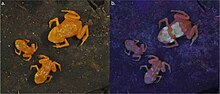

In 2019, scientists discovered that the head and back of this toadlet and the closely related red pumpkin toadlet (B. pitanga) glowed under ultraviolet light, due to their fluorescent skeletons.[11][12] Young that have gained the bright yellow-orange adult colours still lack their fluorescence. It was initially speculated that the fluorescent colour also is aposematic or that it is related to mate choice (species recognition or determining fitness of a potential partner),[12] but later studies indicate that the former explanation is unlikely, as predation attempts on the toadlets appear to be unaffected by the presence/absence of fluorescence.[13]

Peculiarly, this species and the closely related red pumpkin toadlet are unable to hear the frequency of their own advertising calls, as their ears are underdeveloped. Instead their communication appears to rely on certain movements like the vocal sac that inflates when calling, mouth gaping and waving of their arms.[14][15] It is speculated that their calling is a vestigiality from the ancestral form of the genus, whereas their reduced hearing ability (they do have some hearing ability in frequencies outside their call) is a novel change in these species. Sounds make them more vulnerable to predators, but there has likely been little direct evolutionary pressure to lose it because of their toxicity.[14][15]

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) {{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) The pumpkin toadlet (Brachycephalus ephippium), or Spix's saddleback toad, is a small and brightly coloured species of frog in the family Brachycephalidae. This diurnal species is endemic to southeastern Brazil where it is found among leaf litter on the floor of Atlantic rainforests at an altitude of 200–1,250 m (660–4,100 ft). It is found in Espírito Santo, Rio de Janeiro, southeastern São Paulo and southeastern Minas Gerais. Although its type specimen supposedly was collected in Bahia about 200 years ago, there are no confirmed localities in this state and recent reviews consider it more likely that it was from Rio de Janeiro. B. ephippium is locally common, quite widespread compared to most other species of Brachycephalus and it is not considered threatened.

B. ephippium feeds on tiny invertebrates and breeding is by direct development, with the female laying a few eggs on land that hatch into young toadlets (no tadpole stage).