pt-BR

nomes no trilho de navegação

Los tuátaras o esfenodontes (xéneru Sphenodon) son reptiles endémicas de les islles aledañas a Nueva Zelanda, pertenecientes a la familia Sphenodontidae. El significáu del so nome común provien del maorín y quier dicir "llombu espinosu". A la primer vista (por converxencia evolutiva) son paecíes a les iguanes, coles que, sicasí, nun tán cercanamente emparentaes. Miden unos 70 cm de llargor y son insectívoros y carnívoros.

Los dos especies actuales de tuátaras y la estinguida conocida tienen parientes bien cercanos qu'esistieron fai yá 200 millones d'años, al par de los dinosaurios. Neses dómines habitaben el supercontinente de Gondwana distribuyéndose, según paez, dende la área que güei correspuende a América del Sur pasando pola Antártida hasta Australia. Al dixebrase d'Australia por deriva continental, Nueva Zelanda convertir nel únicu apartaz actual de Sphenodontidae, motivu pol cual califíccase a estos animales como fósiles vivientes.

Los tuátaras son los reptiles diápsidos más antiguos que sobreviven. Esisten dalgunos fósiles mesozoicos bien similares, como Homoeosaurus del Xurásicu, lo qu'amuesa la gran antigüedá del grupu.

Ente los numberosos calteres que se caltuvieron ensin modificar mientres 200 millones d'años topen dos fueses envernaes completes, un güeyu pineal bien desenvueltu (el furu pineal yera bien patente nos primeres diápsidos) y les vértebres de tipu anficelo con intercentros. Ye l'únicu reptil actual que los sos machos escarecen de hemipenes (órganu copulador), sinón que copulan al traviés de los sos cloaques.

Unu de les poques traces especializaes son los dientes anteriores, grandes y bien agudos.[1]

Son carnívoros: la so dieta consiste en inseutos, cascoxues, llagartos, güevos y críes d'aves. Tienen vezos nocherniegos; de día fuelguen sobre les roques pa tomar el sol, y de nueche cacen el so alimentu. A los tuátaras, a diferencia d'otros reptiles, présta-yos el fríu. Les temperatures cimeres a los 25 °C son letales pa los tuátaras, pero pueden sobrevivir a temperatures de 5 °C envernando. El güeyu pineal o "tercer güeyu" (un allongamientu de la glándula pineal o epífisis), reparar como un llixeru bárabu fronteru cubierta d'escames y sirve pa detectar la radiación infrarroxo, colo que regulen el metabolismu en función del sol y quiciabes tamién los sirva pa detectar y prindar les preses na escuridá. Son animales solitarios.

Son animales bien llonxevos, y dellos individuos viven más d'un sieglu: en xineru del 2009 verificóse'l casu d'un machu en cautiverio de 111 años que pudo fecundar femes y tener descendencia con elles. Reprodúcense tardíamente: lleguen al maduror sexual aprosimao a los 10 años. La fema entra en celu una vegada cada 4 años. El machu vuélvese más escuru mientres el cortexu, y los escayos del so llombu llevántense. Da vueltes alredor de la fema, y si ella ta llista va mover la so cabeza y va empezar la cópula. La fema efectúa una puesta de 19 güevos aprosimao y guarar por un periodu de 15 meses. Los güevos de los tuátaras son de pulgu nidiu. El sexu de les críes depende de la temperatura. A 21 °C hai 50% de probabilidá de que sían machu o fema. A 22 °C hai 80% de que sían machos y a 20 °C hai 80% de que sían femes.

Como otres especies de Nueva Zelanda, los tuátaras fueron llevaos casi a la estinción cola llegada del home, por cuenta de la perda del so hábitat y a la introducción de nueves especies, en concretu d'aguarones y de mustélidos. Fueron totalmente esterminaos de les islles más grandes de Nueva Zelanda. Anguaño son especies protexíes, y fueron reintroducíes, amás d'en castros, en parques nacionales de les islles grandes.

El calentamientu global supón una grave amenaza pa la supervivencia de la mayoría de reptiles y anfíbios, yá que al aumentar les temperatures de les zones de cría esiste un altu riesgu de que nun futuru cercanu solo nazan animales d'un solu sexu, condergándose a la especie a la estinción nun curtiu periodu. Nel casu de los tuátaras esto podría asoceder si les temperatures en dómina de cría entepasaren los 22 graos dientro d'unes décades.

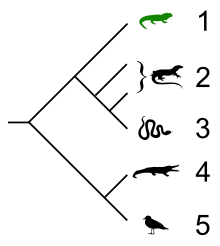

Cladograma simplificáu d'un analís de Rauhut y collaboradores de 2012:[2]

Sphenodontinae

Sphenodon

Los tuátaras o esfenodontes (xéneru Sphenodon) son reptiles endémicas de les islles aledañas a Nueva Zelanda, pertenecientes a la familia Sphenodontidae. El significáu del so nome común provien del maorín y quier dicir "llombu espinosu". A la primer vista (por converxencia evolutiva) son paecíes a les iguanes, coles que, sicasí, nun tán cercanamente emparentaes. Miden unos 70 cm de llargor y son insectívoros y carnívoros.

Los dos especies actuales de tuátaras y la estinguida conocida tienen parientes bien cercanos qu'esistieron fai yá 200 millones d'años, al par de los dinosaurios. Neses dómines habitaben el supercontinente de Gondwana distribuyéndose, según paez, dende la área que güei correspuende a América del Sur pasando pola Antártida hasta Australia. Al dixebrase d'Australia por deriva continental, Nueva Zelanda convertir nel únicu apartaz actual de Sphenodontidae, motivu pol cual califíccase a estos animales como fósiles vivientes.

Tuatara — Yeni Zelandiyada yaşayan heyvandır. Alimlər düşünürlər ki, bu heyvan qədim dinozavrların əcdadlarıdır.

Tuatara — Yeni Zelandiyada yaşayan heyvandır. Alimlər düşünürlər ki, bu heyvan qədim dinozavrların əcdadlarıdır.

An tuataraed a zo stlejviled hag a denn d'ar glazarded hag a zo brosezat e Zeland Nevez. Ne chom nemet daou spesad bev hiziv an deiz en urzhiad-mañ (Sphenodontia) pa oa bras an niver anezho 200 milion a vloavezhioù 'zo. Dont a ra o anv eus ar maorieg ha talvezout a ra kement ha pikoù war e gein. Gwarezet int gant ul lezenn embannet e 1895 dre m'emaint en arvar da vont da get diwar daou abeg pennañ: o zachenn-vevañ a ya war vihanaat ha preizherien nevez zo bet degaset gant mab-den (razh Polinezia (Rattus exulans) en o zouez).

An tuataraed zo glas-gell, betek 80 cm a hirder hag 1,3 kg a bouez enno. Ur gribenn dreinek a red a-hed o c'hein, heverk gant ar pared dreist-holl. Un trede lagad zo war o fenn hag a c'heller gwelet war ar re yaouank betek an oad a 4-6 miz. Goude-se e vez goloet gant skant ha pigmantoù.

2 spesad tuataraed a zo:

a vo kavet e Wikimedia Commons.

An tuataraed a zo stlejviled hag a denn d'ar glazarded hag a zo brosezat e Zeland Nevez. Ne chom nemet daou spesad bev hiziv an deiz en urzhiad-mañ (Sphenodontia) pa oa bras an niver anezho 200 milion a vloavezhioù 'zo. Dont a ra o anv eus ar maorieg ha talvezout a ra kement ha pikoù war e gein. Gwarezet int gant ul lezenn embannet e 1895 dre m'emaint en arvar da vont da get diwar daou abeg pennañ: o zachenn-vevañ a ya war vihanaat ha preizherien nevez zo bet degaset gant mab-den (razh Polinezia (Rattus exulans) en o zouez).

An tuataraed zo glas-gell, betek 80 cm a hirder hag 1,3 kg a bouez enno. Ur gribenn dreinek a red a-hed o c'hein, heverk gant ar pared dreist-holl. Un trede lagad zo war o fenn hag a c'heller gwelet war ar re yaouank betek an oad a 4-6 miz. Goude-se e vez goloet gant skant ha pigmantoù.

La tuatara és un rèptil lepidosaure del grup dels rincocèfals (Sphenodon punctatus). És originari i endèmic de Nova Zelanda. Pertany a l'ordre Sphenodontia.[1][2] És una espècie molt primitiva, que va tenir el seu zenit fa 200 milions d'anys (en l'època dels dinosaures i abans) que encara sobreviu, amb aspecte de llangardaix i que viu en galeries excavades. Mesura uns 70 cm de llargada i és insectívor i carnívor. Té les dents anteriors molt grans i esmolades, el seu tipus de dentició és únic entre totes les espècies vives. És l'únic dels rèptils actuals que no té un òrgan copulador. Encara que es pugui considerar un fòssil vivent, en realitat ha experimentat molts canvis evolutius respecte als seus antecedents del Mesozoic.

El nom de tuatara deriva de l'idioma maorí i significa puntes a l'esquena.[3]

La tuatara és de gran interès per a l'estudi de l'evolució de llangardaixos i serps, i per la reconstrucció de l'aspecte i hàbits dels primers diàpsids (el grup que inclou aus i cocodrils).

La tuatara és un rèptil lepidosaure del grup dels rincocèfals (Sphenodon punctatus). És originari i endèmic de Nova Zelanda. Pertany a l'ordre Sphenodontia. És una espècie molt primitiva, que va tenir el seu zenit fa 200 milions d'anys (en l'època dels dinosaures i abans) que encara sobreviu, amb aspecte de llangardaix i que viu en galeries excavades. Mesura uns 70 cm de llargada i és insectívor i carnívor. Té les dents anteriors molt grans i esmolades, el seu tipus de dentició és únic entre totes les espècies vives. És l'únic dels rèptils actuals que no té un òrgan copulador. Encara que es pugui considerar un fòssil vivent, en realitat ha experimentat molts canvis evolutius respecte als seus antecedents del Mesozoic.

El nom de tuatara deriva de l'idioma maorí i significa puntes a l'esquena.

La tuatara és de gran interès per a l'estudi de l'evolució de llangardaixos i serps, i per la reconstrucció de l'aspecte i hàbits dels primers diàpsids (el grup que inclou aus i cocodrils).

Hatérie novozélandská (tuatara, Sphenodon punctatus) je jeden ze dvou posledních přežívajících druhů řádu hatérií, prastarého řádu plazů, který byl nejvíce rozšířen ve druhohorách. Náleží tedy mezi živoucí zkameněliny. Její domorodé jméno (pochází ze staré maorštiny), tuatara, znamená nesoucí šípy, a značí řadu špičatých šupin, které má hatérie na hřbetě.

Žije pouze na několika ostrovech okolo Nového Zélandu, kde je přísně chráněna. Počet žijících jedinců se odhaduje na asi padesát tisíc.

Dosahuje délky 50 až 80 cm. Samečci mohou vážit až do 1 kg, samičky o 0,5 kg méně.

Vzhled hatérií se od druhohor nezměnil. Mají stále zachovanou strunu hřbetní.

Hatérie novozélandská se živí především hmyzem, případně také malými ještěrkami.

Hatérie novozélandská je noční živočich, i když se občas potřebuje ohřát na slunci. Má velice nízkou obvyklou teplotu těla (12 °C), pohybuje se proto velmi pomalu. Pro svůj život tedy potřebuje chlad. Při pohybu se nadechuje každých sedm sekund, v klidu jen jednou za hodinu. Dospělé velikosti dosáhne až za 20 let. Jsou dlouhověké – nejstaršímu známému jedinci tohoto druhu bylo v roce 2009 111 let (když se poprvé v životě pářil s 80letou samicí).[1]

Páření může začít v období pohlavní dospělosti (asi ve 20 letech). Obě pohlaví se na sebe musí přitisknout kloakami, neboť samec nemá kopulační orgán. Zárodek se utváří 1 rok. Samice klade až 15 vajíček s bílou skořápkou. Po nakladení vajec se již o ně nikdo nestará. Mláďata se líhnou za 13–15 měsíců.

Hatérie novozélandská (tuatara, Sphenodon punctatus) je jeden ze dvou posledních přežívajících druhů řádu hatérií, prastarého řádu plazů, který byl nejvíce rozšířen ve druhohorách. Náleží tedy mezi živoucí zkameněliny. Její domorodé jméno (pochází ze staré maorštiny), tuatara, znamená nesoucí šípy, a značí řadu špičatých šupin, které má hatérie na hřbetě.

Tuataraer eller broøgler omfatter to arter af krybdyr, Sphenodon punctatus og S. guentheri. De er de eneste nulevende repræsentanter for ordenen Rhynchocephalia. Tuataraerne overlever i dag kun på nogle små øer ud for New Zealands kyst.

Tuataraer har en overfladisk lighed med øgler, men adskiller sig fra disse ved hverken at have trommehinder, mellemøre eller egentlige tænder (men i stedet savtakkede kæber). Tuataraer har tre øjne. Ligesom andre krybdyr er de ektoterme, dvs. deres kropstemperatur følger omgivelsernes temperatur tæt. Til trods for dette er tuataraer usædvanligt kuldetolerante og kan være aktive ved temperaturer helt ned til 10 oC. De har et meget lavt stofskifte og kan i hvile nøjes med én vejrtrækning i timen. Hunnerne bliver ikke kønsmodne, før de er mindst 20 år gamle, men en tuataras levetid kan til gengæld overstige 100 år.

Tuataraer lever enten i huler, de selv har gravet eller i redehuller, de har overtaget fra ynglende havfugle. De er nataktive og søger føde tæt på hulens indgang. Føden består hovedsageligt af insekter, men også af og til af mindre hvirveldyr og fugleæg.

Hunnen er drægtig i et år, før hun lægger sine æg, som klækker efter endnu et år.[1]

Tuataraer eller broøgler omfatter to arter af krybdyr, Sphenodon punctatus og S. guentheri. De er de eneste nulevende repræsentanter for ordenen Rhynchocephalia. Tuataraerne overlever i dag kun på nogle små øer ud for New Zealands kyst.

Tuataraer har en overfladisk lighed med øgler, men adskiller sig fra disse ved hverken at have trommehinder, mellemøre eller egentlige tænder (men i stedet savtakkede kæber). Tuataraer har tre øjne. Ligesom andre krybdyr er de ektoterme, dvs. deres kropstemperatur følger omgivelsernes temperatur tæt. Til trods for dette er tuataraer usædvanligt kuldetolerante og kan være aktive ved temperaturer helt ned til 10 oC. De har et meget lavt stofskifte og kan i hvile nøjes med én vejrtrækning i timen. Hunnerne bliver ikke kønsmodne, før de er mindst 20 år gamle, men en tuataras levetid kan til gengæld overstige 100 år.

Tuataraer lever enten i huler, de selv har gravet eller i redehuller, de har overtaget fra ynglende havfugle. De er nataktive og søger føde tæt på hulens indgang. Føden består hovedsageligt af insekter, men også af og til af mindre hvirveldyr og fugleæg.

Hunnen er drægtig i et år, før hun lægger sine æg, som klækker efter endnu et år.

Die Brückenechse oder Tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus) ist die einzige rezente Art der Familie Sphenodontidae. Diese nur auf neuseeländischen Inseln verbreiteten Tiere gelten als lebende Fossilien, weil sie Überlebende einer relativ diversen Gruppe sind, der Sphenodontia, deren Blütezeit mehr als 150 Millionen Jahre zurückliegt. Die Tiere leben heute nur noch auf einigen kleineren Inseln von Neuseeland.[1]

Grundlegende morphologische Eigenheiten gegenüber anderen rezenten Vertretern der Reptilien, speziell das Vorhandensein eines unteren Schläfenbogens, welcher als „Brücke“ eine namensgebende Bedeutung hat und sie von den im Habitus recht ähnlichen Schuppenkriechtieren (Squamata) unterscheidet, rechtfertigen nach derzeitiger Ansicht die Einordnung in eine eigene Ordnung (ebenjene Sphenodontia, auch als Rhynchocephalia bezeichnet). Im Unterschied zu vielen anderen wechselwarmen Reptilien sind sie selbst bei niedrigen Temperaturen aktiv und trotz der deutlich geringeren Körperwärme in der Lage, aktiv nach Beutetieren wie Gliederfüßern oder auch Vogeleiern zu suchen. Über die Lebensweise der bedrohten Brückenechsen ist im Gegensatz zu ihrer Morphologie relativ wenig bekannt.

Der Gattungsname Sphenodon ist zusammengesetzt aus den altgriechischen Wörtern σφήν sphén, deutsch ‚Keil‘ und ὀδούς odous, deutsch ‚Zahn‘. Das Spezies-Epitheton punctatus ist lateinisch und heißt ‚gepunktet‘. Die Trivialbezeichnung „Tuatara“ kommt aus der Sprache der Maori, bedeutet ‚stacheliger Rücken‘[2] und bezieht sich auf den stacheligen Rückenkamm der Tiere. Der deutsche Trivialname „Brückenechse“ wurde 1868 von Eduard von Martens eingeführt. Er weist auf die beiden vollständigen „Knochenbrücken“ (Schläfenbögen) im gefensterten hinteren Teil des Schädels dieser Tiere hin[3] (siehe → Skelett).

Brückenechsen werden durchschnittlich 50 bis 75 Zentimeter lang und wiegen etwa ein Kilogramm, Männchen sind dabei etwas größer. Sie sind kräftig gebaute, plumpe Echsen mit einem Dorsalkamm aus verlängerten Hornplättchen. Der Vorderschädel ist leicht schnabelartig verlängert. Sie haben eine gräuliche Grundfarbe.

Die Haut der Brückenechsen ist der der Schuppenkriechtiere ähnlich. Die Unterhaut besitzt meist horizontal verlaufende Bindegewebsfasern und liegt locker der unter ihr liegenden Muskulatur auf. Die Lederhaut ist sehr dick und besitzt größere Bindegewebsfaserbündel. Unter der Lederhaut liegt der Großteil der großen, verzweigten Chromatophoren. Ihr körniger, schwarzer bis brauner Pigmentinhalt kann durch Kontraktion und Ausdehnung einen physischen Farbwechsel herbeiführen. Wenn dort auch kleiner, lassen sich die Chromatophoren bis in das Stratum corneum verfolgen. Dorsal bildet die Epidermis etliche Granularschuppen, welche an den Zehen ihre maximale Größe erreichen. Den Körperseiten entlang angeordnete Hautfalten tragen zugespitzte Tuberkelschuppen. Die Beschuppung der Bauchseite besteht aus annähernd quadratischen Schildchen. Vom Hinterhaupt verläuft über die Rückenseite des Körpers ein Kamm, der aus Stachelschuppen besteht und bei Männchen höher ist. Brückenechsen häuten sich nur ein- oder zweimal im Jahr.

Der diapside Schädel von Brückenechsen unterscheidet sich durch das Vorhandensein zweier voll ausgebildeter Schläfenbögen grundlegend von dem Schädel der übrigen Schuppenechsen. Er verfügt somit auch nicht über das „Schubstangensystem“, das den relativ stark in sich beweglichen (kinetischen) Schädel der übrigen Schuppenechsen auszeichnet. Unter anderem deshalb werden die Brückenechsen in der Systematik auch in eine eigene Untergruppe der Schuppenechsen gestellt, die Sphenodontia. Tatsächlich ist der Schädel der Brückenechsen akinetisch, das heißt, dass Oberkiefer und Gaumendach nicht gegen den Hirnschädel beweglich sind. Allerdings finden sich bei Embryos noch Gelenkungen zwischen den Schädelkomponenten, daher wird der starre Schädel adulter Brückenechsen oft als Anpassung an die grabende Lebensweise und Ernährung gedeutet. Im Zusammenhang mit der Lebensweise stehen auch zwei knöcherne, abwärts gerichtete Fortsätze am vorderen Ende des Prämaxillare (Teil des Oberkiefers), an denen funktionelle „Schneidezähne“ sitzen, was der Schnauzenpartie des Schädels in der Seitenansicht das typische hakenschnabelartige Aussehen verleiht. Die Bezahnung ist akrodont, das heißt, dass die Zähne mit dem oberen Kieferrand verschmolzen sind. Brückenechsen fehlt also jeglicher Zahnwechsel, wodurch aus dem Zustand der Zähne Rückschlüsse auf das Alter gezogen werden können. Bei alten Brückenechsen ist nur noch eine Kauleiste vorhanden. An den äußeren Rändern der Gaumenbeine befindet sich eine Zahnreihe mit elf oder zwölf Zähnen parallel zu den hinteren Zähnen der Maxillaria. Ältere Männchen können zusätzlich ein bis zwei Zähne am Pflugscharbein aufweisen. Am Vorderende des Dentale (zahntragender Teil des Unterkiefers) existiert eine Art Eckzahn, welcher sich stark von der dort vorhandenen spitz-sägeförmigen Zahnreihe unterscheidet. Die Zahnreihe des Unterkiefers greift beim Zubeißen genau in die Lücke zwischen Maxillar- und Gaumenzahnreihe.[3] Da Brückenechsen ihren Unterkiefer nach vorne und zurück schieben können und somit die Beute zerschneiden („zersägen“), statt sie zu zerreißen, ist es ihnen möglich, harte Chitinpanzer großer Insekten zu knacken und kleine Echsen zu zertrennen.[4]

Anders als bei den Schuppenkriechtieren fehlt bei Brückenechsen mit dem Spleniale das siebte Element des Unterkiefers. Besonders auffällig am Schädel von Brückenechsen ist ein großes Scheitelloch (Foramen parietale) für das Scheitelauge. Das dreieckige, als dünne Knochenplatte ausgebildete Quadratum steht senkrecht zur Schädelmedianebene und wird dorsal durch Flügelbein und Squamosum verstärkt. Ventral bildet das Quadratum zusammen mit dem Quadratojugale eine Gelenkfläche für das gelenkende Element (Articulare) des Unterkiefers.

Das postcraniale Skelett (Skelett ohne Schädel) der Brückenechsen ist durch eine Wirbelsäule mit 27 präcaudalen (vor dem Schwanz liegenden) Wirbeln aus 8 Hals-, 17 Rumpf- und zwei Kreuzwirbeln charakterisiert. Kennzeichnend für den ersten Halswirbel (Atlas) ist ein Rudiment des Proatlas. Wie bei einigen anderen Schuppenkriechtieren kann der Schwanz zum Selbstschutz abgeworfen werden (Autotomie), wobei das Regenerat von einem transparent erscheinenden Knorpelstab gestützt wird. Ab dem vierten Halswirbel haben Brückenechsen kurze Halsrippen. Die Rippen des Rumpfes weisen bei Brückenechsen knorpelartige, flügelähnliche Verbreiterungen auf. Diese überlappen sich und bilden somit eine Art Panzerung für die Leibeshöhle. Die neunte bis zwölfte Rumpfrippe ist unten am Brustbein befestigt.

Das Gehirn der Brückenechsen ist wesentlich kleiner als das es umgebende Hirnschädelvolumen und deutlich primitiver als das Gehirn anderer Schuppenkriechtiere. Das Endhirn setzt sich in sehr lange Riechbahnen fort, die in dicken Riechkolben enden. Das Mittelhirndach (Tectum mesencephali) liegt sehr viel niedriger als bei Schuppenkriechtieren. Fünfter, siebter, achter, neunter und zehnter Hirnnerv ähneln in ihrer Lage stark denen von Amphibien und Fischen.

Ein besonderes Sinnesorgan, das Scheitelauge, teilen sie nur mit wenigen anderen Reptilien sowie Neunaugen. Es besitzt eine linsenähnliche Epithelschicht, welcher sich ein basaler, netzhautartiger Teil anschließt. Ein dünner Nervus parietalis leitet die Sinnesreize zum Zwischenhirn. Mit diesem Sinnesorgan können sie nur Helligkeit wahrnehmen, das aber wahrscheinlich feiner als „normale“ Augen. Außerdem könnte das Scheitelauge zur Regelung des Wärmehaushaltes dienen.

Die großen Augen von Brückenechsen sitzen in einer dementsprechenden Augenhöhle. Anders als bei Schuppenkriechtieren hat der Musculus retractor bulbi zwei Ansätze am Augapfel. Es fehlt eine Tränendrüse zur Befeuchtung der äußeren Augen, allerdings haben Brückenechsen hinter dem Augapfel eine funktionale Harder-Drüse, welche ein öliges Sekret produziert und so die Nickhaut gleitfähig hält. Überschüssige Feuchtigkeit wird mittels Tränenkanälchen und Tränen-Nasen-Gang abgeleitet, die in die Nasenhöhle führen. Es sind beide Augenlider vorhanden, aber das untere ist deutlich größer und stärker entwickelt. Die transparente Nickhaut ist mit einer Nickhautsehne mit dem sogenannten Musculus bursalis verbunden, welcher die Nickhaut bewegt. Die meist wegen Lichteinfalls schlitzförmige Pupille ist kein Indiz für reine Nachtaktivität, sondern für die hauptsächlich nächtliche Jagdaktivität. Die Netzhaut enthält nicht Stäbchen und Zapfen, sondern zwei verschiedene Zapfentypen, wodurch die Tiere zwar tags und nachts sehr gut sehen können, aber das Farbsehen nicht oder nur rudimentär vorhanden ist. Hinter der Netzhaut findet sich eine Tapetum lucidum genannte Zellschicht, welche durch die Reflexion des durch die Retina dringenden Lichtes als Restlichtverstärker funktioniert.

Die Nase von Brückenechsen weist hinter dem Nasenvorhof (Vestibulum nasi) noch eine zweite größere Erweiterung auf.

Die Geschmacksknospen der Brückenechsen liegen vor allem auf der Gaumenschleimhaut. Die nicht gespaltene Zunge wird, anders als bei etlichen anderen Reptilien, nicht zum Züngeln und somit zur chemosensorischen Orientierung benutzt (siehe auch Jacobson-Organ).

Obwohl Brückenechsen keine äußere Ohröffnung und kein oberflächliches Trommelfell haben, hören sie gut. Das geräumige Mittelohr steht über die Eustachi-Röhre mit der Rachenhöhle in Verbindung. Der restliche Aufbau ist im Wesentlichen mit dem der Schuppenkriechtiere identisch.

Das aus Sinus venosus, einer Herzkammer (Ventriculus cordis) und zwei Herzvorhöfen (Atria) bestehende Herz von Brückenechsen ist durch seine weit vorgeschobene Lage auf Höhe des Schultergürtels charakterisiert. In den Sinus venosus münden drei Hohlvenen ein. Die Vorhöfe wirken von oben gesehen als einheitlicher Sack, sie sind aber innen durch ein gut ausgebildetes Vorhofseptum vollständig getrennt. Die von den Vorhöfen durch eine deutliche Herzkranzfurche (Sulcus coronarius) abgesetzte Herzkammer ist dickwandig und muskulös; im Inneren weist sie kaum Septen auf, eine Plesiomorphie. Weitere Besonderheiten sind ein gut entwickelter Ductus caroticus und Ductus arteriosus auf jeder Seite sowie der Ursprung der rechten und linken Halsschlagader aus einem rechten Aortenbogen. Auch der Ursprung der Arteria laryngea aus dem Pulmonarbogen ist wie die vorher genannten besonderen Gefäßsysteme eine Plesiomorphie.

Der Atmungsapparat der Brückenechsen ist ursprünglich. Der Kehlkopf wird von einem unpaaren Ringknorpel und einem paarigen Stellknorpel gebildet, die Luftröhre wird von knorpeligen Spangen gestützt. Die Luftröhre führt über einen kurzen Bronchus beiderseits in die beiden Lungen, die lediglich dünnwandige Säcke darstellen. Die innere Oberfläche der beiden Lungen ist von einem Netz bienenwabenartiger Räume bedeckt, welche nach hinten größer werden. Mit Hilfe der Kehlkopfknorpel können die sonst stummen Tiere beim Ausatmen zur Verteidigung gegen Feinde und zur Verständigung mit Artgenossen Laute erzeugen.

Der einfach gebaute Verdauungsapparat der Brückenechsen besteht unter anderem aus einer weit dehnbaren Speiseröhre, welche in den langen, spindelförmigen Magen führt. Der Dünndarm liegt in zwei bis drei Schlingen im rechten Teil der Bauchhöhle. Der Dickdarm mündet in den Kotraum (Coprodaeum) der Kloake.

Die linke Niere ist bei Brückenechsen fast doppelt so groß wie die rechte. Je ein kurzer Harnleiter mündet in den Harnraum (Urodaeum) der Kloake. Diese Mündungen sind bei Männchen gemeinsam mit den Samenleitern, aber bei Weibchen getrennt vom Eileiter.

Speziell die inneren Geschlechtsorgane weisen keine besondere Spezialisierung auf. Zwar ist bei Weibchen die Fähigkeit zur Spermaspeicherung vorhanden, aber kein spezielles Organ hierfür zu finden. Den Männchen fehlt ein Kopulationsapparat, ein unpaarer Penis ist sekundär verloren gegangen, paarige Hemipenes wie bei Schuppenkriechtieren sind auch nicht in Embryonalstadien vorhanden. Bei beiden Geschlechtern befinden sich manchmal als Hemipenis-Homologa gedeutete Analdrüsen, welche wahrscheinlich Talg produzieren.

Brückenechsen sind hauptsächlich dämmerungs- oder nachtaktiv, worauf nicht zuletzt ihre großen Augen mit schlitzartigen Pupillen schließen lassen. Sie graben sich oft eigene Wohnhöhlen in humusartigen Boden, wo sie den Großteil des Tages verbringen. Im Gegensatz zu einer verbreiteten Ansicht leben sie nur selten in Wohnhöhlen von Seevögeln, mehr dazu siehe unten.

Tuataras bewegen sich recht langsam fort. Sie laufen mit abstehenden Beinen und lateralen Wellenbewegungen von Schwanz und Rumpf, welche am Boden schleifen. Kurzfristig können sie mit erhobenen Rumpf spurten, halten diesen Laufstil aber meist nur wenige Meter durch.

Im Unterschied zu fast allen anderen Reptilien, die Körpertemperaturen zwischen 25 und 40 °C bevorzugen, leben Brückenechsen unter wesentlich kühleren Verhältnissen. Die Angaben der Vorzugskörpertemperatur weichen in der Literatur deutlich voneinander ab: Robert Mertens konkretisierte die Vorzugstemperatur auf 10,6 °C[5], in „Grzimeks Tierleben“ wird von 12 °C gesprochen[6], andere Quellen sprechen von 17 bis 20 °C.[7] Offenbar werden sie erst bei 7 °C lethargisch.[8] Der niederen Temperatur entspricht ein langsamer Stoffwechsel: Brückenechsen wachsen sehr langsam, sie können ein hohes Alter erreichen (siehe unten).

Brückenechsen ernähren sich primär von Wirbellosen, meist Insekten (hier besonders Käfern und Heuschreckenartigen), Spinnen und Schnecken sowie Regenwürmern. Nach Aussagen von Einheimischen ist die Weta-Art Deinacrida rugosa die bevorzugte Beute der Brückenechsen.[9] Diese verfolgen sie nicht aktiv, sondern warten oft am Eingang zu ihrer Wohnhöhle, bis eine Weta vorbeikommt. Eine seltene Nahrung von Brückenechsen sind Seevögel – mehr dazu siehe unten.

Die Paarung erfolgt während des südlichen Sommers von Januar bis März, wobei Männchen anders als Weibchen jedes Jahr paarungsbereit sind. Die 25 Quadratmeter großen Territorien der Männchen mit einer Wohnhöhle im Zentrum werden nur zur Paarungszeit verteidigt. Dringt ein Männchen in das Revier eines anderen ein, wird es angegriffen. Dabei kann es durchaus zu Verletzungen kommen, wie zahlreiche Narben an älteren Männchen belegen.

Die eigentliche Umwerbung des Weibchens beginnt, wenn eines in das Territorium des Männchens eindringt. Dabei wird das Weibchen vom Männchen steifbeinig umzirkelt. Da männliche Brückenechsen kein verlängertes Genitalorgan haben, pressen sie ihre Kloake an die des Weibchens. Die Kopulation dauert etwa eine Stunde. Nach ungefähr neun Monaten legen die Brückenechsen-Weibchen in eine selbstgegrabene Erdhöhle ein Gelege von bis zu 15 an den Enden stumpfen, pergamentschaligen, drei Zentimeter langen und vier bis sechs Gramm schweren Eiern. Die Bruthöhle befindet sich oft hunderte Meter weit von der Wohnhöhle des Weibchens entfernt; bei der Bruthöhle verbringen sie anschließend Tage oder auch Wochen. Nach dem Auspolstern des Nestes mit Gras und Erde und dem Schließen der Höhle mit Erde zeigen die Weibchen, anders als die vieler anderer Reptilien, eine Art Brutpflege: Sie halten regelmäßig, manchmal jede Nacht, Wache an ihrem Nest, um zu verhindern, dass andere Weibchen ihre Eier in das Nest legen. In Neuseeland schlüpfen die circa zehn Zentimeter langen und fünf Gramm schweren Jungtiere 13 bis 15 Monate nach der Eiablage; diese längste von Kriechtieren bekannte Brutperiode zeigt, dass die Keimlinge im kälteren neuseeländischen Klima eine Winterruheperiode durchmachen. Die Jungtiere sind anders als die Adulti tagaktiv, um nicht von großen Artgenossen gefressen zu werden. Nach einem Jahr bewohnen sie die Wohnkolonien der Adulti und gleichen ihnen in der Lebensweise. Weibchen legen nicht jedes Jahr Eier ab; nicht zuletzt deswegen ist zum Erhalt der Art ein hohes Individualalter nötig. Nach stark umstrittenen Angaben erreichen Brückenechsen ein Alter von bis zu 150 Jahren. Im Jahre 2009 war das älteste in Gefangenschaft gehaltene Exemplar 111 Jahre alt.[10]

Über die Entwicklung der Eier unter menschlicher Aufsicht ist man durch die Schutzaktion der Viktoria-Universität in Wellington gut unterrichtet. Im November gesammelte Eier von der Insel „The Brothers“ werden bei Temperaturen von 18 bis 23 Grad künstlich bebrütet, wodurch die Schlupfrate wesentlich erhöht wird. Da die Jungtiere dort nach nur sechs Monaten im Mai schlüpfen, lässt sich schließen, dass die Nester in freier Natur niedrigeren Temperaturen und größeren Schwankungen ausgesetzt sind.[11]

Offenbar wird die Verteilung der Geschlechter bei Brückenechsen direkt durch die Bruttemperatur beeinflusst. Bei Sphenodon punctatus schlüpften bei konstant 18 °C Bruttemperatur ausschließlich Weibchen, bei 20 °C 91 % Weibchen, bei 22 °C allerdings nur 23 %.[12]

Ein bemerkenswerter Aspekt der Biologie und Ökologie der Brückenechsen ist ihr Zusammenleben mit Seevögeln. Eine Annahme besagt, dass sie dort in einer fast symbiotischen Beziehung friedlich und höhlenteilend miteinander lebten. Allerdings überwiegt offenbar der Nutzen für das Reptil: Der Kot der Vögel und der Boden bilden die Nahrungsgrundlage für diverse Wirbellose, welche der Brückenechse als Nahrung dienen. Diese These ist in letzter Zeit verstärkt in Zweifel gezogen worden, da viele Indizien auf eine ausschließlich für die Brückenechse nützliche und für den Seevogel schädliche Beziehung hindeuten. In Erdhöhlen, in denen Brückenechsen lebten, wurden wiederholt angegriffene Küken ohne Kopf gefunden. Da in der Region dieser Funde keine Ratten oder ähnliche Tiere leben, ist die Brückenechse das einzige Tier, welches zur Tötung der Küken imstande ist. Brückenechsen dürften auch Gelege zertrampeln. Bei Beobachtungen flohen die kleineren Pinguin-Sturmtaucher (Pelecanoides urinatrix) immer aus ihren Höhlen, wenn Brückenechsen versuchten, in diese einzudringen. Sturmvögel von beträchtlicher Größe wie Puffinus griseus vertreiben Brückenechsen aus der Nähe ihrer Höhlen und sind dabei meist erfolgreich. Wenn Brückenechsen in den Höhlen von Seevögeln lebten, dann war die Höhle fast immer schon vom Vogel verlassen worden.

Die Lebensräume der Brückenechsen sind durch ein eher raues Klima, starken Grasbewuchs und geringen Baumwuchs charakterisiert.

Derzeit leben Brückenechsen nur noch auf etwa 30 kleinen neuseeländischen Inseln, die in der Cookstraße sowie zwischen der Bay of Plenty und der Bay of Islands entlang der Nordwestküste der nördlichen Hauptinsel liegen.

Durch den Menschen eingeschleppte Nagetiere sind der Grund für das Verschwinden der Art von den Hauptinseln Neuseelands.[1] Früher lebten die Reptilien auch auf der nördlichen Hauptinsel, ein ehemaliges Vorkommen auf der Südinsel ist umstritten.[3]

Die Brückenechsen wurden durch den Menschen stark dezimiert, vor allem durch von ihm eingeführte Ziegen, Katzen, Hunde, Schweine, Ratten und Mäuse sowie durch die Umwandlung ihres natürlichen Lebensraumes in Acker- und Weideland. Die Gattung Sphenodon bewohnt mittlerweile nur noch 0,1 % des ursprünglich von ihr bewohnten Areals. Die Art Sphenodon diversum ist nur aus Knochenfunden bekannt, von der Unterart S. punctatus reischeki wurde seit 1978 kein Exemplar mehr gesehen. Eine weitere Bedrohung für die Art ist Wilderei, da die Brückenechsen aufgrund ihrer Seltenheit und Exotik gefragte Terrarientiere sind.

Seit den neunziger Jahren des 20. Jahrhunderts wurden die Ratten, welche die Hauptbedrohung für die Brückenechse darstellten, auf nahezu sämtlichen von der Art bewohnten Inseln ausgerottet. Ebenso bemüht man sich um Wiederaufforstung und Renaturierung des Lebensraumes sowie um die Wiederansiedlung von Brückenechsen auf einst von ihnen bewohnten Inseln. Auch auf der Nordinsel Neuseelands gibt es mittlerweile wieder Bestände in größeren, umzäunten Gebieten. Diese Maßnahmen haben dazu geführt, dass sich der Bestand auf mittlerweile 55.000 erwachsene Exemplare erholt hat. Obwohl der Lebensraum der Brückenechsen stark fragmentiert ist und die Art auf kontinuierliche Schutzmaßnahmen angewiesen ist, wird sie von der IUCN derzeit als nicht gefährdet (least concern) eingestuft.[13]

Eine Zeit lang wurde eine Population auf einigen kleinen Inseln in der Cookstraße in die eigene Art Sphenodon guentheri gestellt[14]. Inzwischen ergaben molekularbiologische Untersuchungen, dass die, obschon vorhandenen, genetischen Unterschiede nicht groß genug sind, um die Trennung in zwei Arten zu rechtfertigen; daher wurde Sphenodon guentheri mit Sphenodon punctatus synonymisiert.[15]

Sphenodon diversum wurde 1885 anhand eines einzelnen, unvollständigen und nicht fossilierten Skeletts, das aus einem Steinbruch geborgen worden war, von William Colenso beschrieben.[16] Lebende Exemplare wurden seitdem nicht gefunden.

Brückenechsen werden oft als lebende Fossilien bezeichnet, da Vertreter aus der näheren Verwandtschaft der Brückenechsen (Sphenodontia), bereits aus dem Ladinium (obere Mitteltrias) vor circa 240 Millionen Jahren nachgewiesen.[17]

Die Brückenechse Sphenodon, die heute auf einigen neuseeländischen Inseln lebt, unterscheidet sich durch den noch vorhandenen Jochbogen des Schädels, der allen Eidechsen und Schlangen fehlt, von sämtlichen Kleinreptilien. Diese Nachweis ermöglicht die Zuordnung zu einer altertümlichen Gruppe, die in Trias und Jura weltweit anzutreffen war. Ab dem Zeitalter der Oberkreide sind keine Fossilien mehr bekannt.[1]

Sphenodontier waren somit in der Obertrias und im Jura weltweit verbreitet, wurden jedoch ab der frühen Kreide zunehmend von „modernen“ Reptilien, speziell den Schuppenkriechtieren (Squamata), zurückgedrängt und konnten sich nur auf den isolierten neuseeländischen Inseln bis heute halten. Der Grund für die anfängliche Dominanz der Sphenodontier und den plötzlichen Aufschwung der Squamaten ist unklar, weil beide Entwicklungslinien Schwestergruppen und damit gleich alt sind.

Die Sphenodontia lassen sich in zwei Familien unterteilen: Sphenodontidae und Pleurosauridae. Die Sphenodontiden sind terrestrische Formen. Die rezenten Brückenechsen gehören dieser Familie an und der älteste bekannte Sphenodontier in der späten Mitteltrias dürfte ebenfalls dieser Familie angehört haben. Einer der jüngsten Vertreter der Blütezeit der Sphenodontier ist die relativ gut bekannte Gattung Homoeosaurus („Scheinbrückenechsen“) aus dem Oberjura, eine Gruppe, die sich kaum von den heutigen Brückenechsen unterschied. Die Sphenodontiden sind somit seit mindestens 150 Millionen Jahren morphologisch ausgesprochen konservativ. 2020 wurde das Genom erstmals sequenziert, wobei Anzeichen stetiger molekularer Evolution sowie leichter morphologischer Evolution nachgewiesen wurden. Das Genom der Spezies enthält Sequenzen, die bisher nur jeweils in Reptilien oder Säugetieren gefunden wurden, wodurch die phylogenetische Verwandtschaft der Säugetiere und Reptilien bestätigt wurde.[18]

Die Vertreter der Pleurosauriden gingen hingegen zur aquatischen Lebensweise über. Eine dieser Formen ist Pleurosaurus goldfussi. Fossilien dieses bis zu 1,5 Meter langen Reptils, dessen Schwanzwirbelsäule doppelt so lang ist wie der übrige Körper, wurden, wie auch Überreste des Sphenodontiden Homoeosaurus maximiliani, in den oberjurassischen Plattenkalken von Solnhofen (Fränkische Alb)[19] und den Plattenkalken von Canjuers (Département Var, Frankreich)[20] gefunden. Der Fossilbericht der Pleurosauriden ist jedoch im Gegensatz zu dem der Sphenodontiden auf den Jura beschränkt.

Da die Tiere strengsten Schutz durch die neuseeländische Regierung genießen, werden derzeit (Stand März 2011) nur etwa 140 Brückenechsen in zehn Institutionen gehalten, davon 43 außerhalb Neuseelands. In Deutschland werden sie nur im Aquarium des Berliner Zoos gezeigt. Dort leben (Stand Mai 2021) sieben Exemplare in einem großen, gekühlten Terrarium.

In Unkenntnis der speziellen Temperaturbedürfnisse von Brückenechsen wurde der Großteil der Tiere früher zu warm gehalten. Eine der ersten in Europa oder auch weltweit gehaltenen Brückenechsen war im zoologischen Institut der Universität Uppsala präsent, wo sie im Herbst 1908 ankam. Sie lebte dort bis Sommer 1931 in einer 75 × 40 × 40 cm großen Holzkiste unter einem Schreibtisch, die gesamte Kiste war nur mit Holzwolle ausgekleidet und enthielt ein Wassergefäß. Die Temperaturen schwankten zwischen 16 und 20 °C. 1931 kam sie in eine 190 × 75 × 30 cm große Holzkiste, welche strukturiert eingerichtet war. Dort zeigte sie größere Aktivitäten. Sie wurde wöchentlich mit ein paar Fleischstreifen oder 15 bis 20 Regenwürmern gefüttert.[21]

In John Greens Roman Schlaft gut, ihr fiesen Gedanken vermacht ein Mann in seinem Testament sein ganzes Vermögen seiner Tuatara.

Die Brückenechse oder Tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus) ist die einzige rezente Art der Familie Sphenodontidae. Diese nur auf neuseeländischen Inseln verbreiteten Tiere gelten als lebende Fossilien, weil sie Überlebende einer relativ diversen Gruppe sind, der Sphenodontia, deren Blütezeit mehr als 150 Millionen Jahre zurückliegt. Die Tiere leben heute nur noch auf einigen kleineren Inseln von Neuseeland.

Grundlegende morphologische Eigenheiten gegenüber anderen rezenten Vertretern der Reptilien, speziell das Vorhandensein eines unteren Schläfenbogens, welcher als „Brücke“ eine namensgebende Bedeutung hat und sie von den im Habitus recht ähnlichen Schuppenkriechtieren (Squamata) unterscheidet, rechtfertigen nach derzeitiger Ansicht die Einordnung in eine eigene Ordnung (ebenjene Sphenodontia, auch als Rhynchocephalia bezeichnet). Im Unterschied zu vielen anderen wechselwarmen Reptilien sind sie selbst bei niedrigen Temperaturen aktiv und trotz der deutlich geringeren Körperwärme in der Lage, aktiv nach Beutetieren wie Gliederfüßern oder auch Vogeleiern zu suchen. Über die Lebensweise der bedrohten Brückenechsen ist im Gegensatz zu ihrer Morphologie relativ wenig bekannt.

At Braghaagedisje of Tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus) as di iansagst slach uun det famile Sphenodontidae an uun det order Sphenodontia. Ööder slacher faan detdiar order san uun a leetst 150 miljuun juaren ütjstürwen. Hat as sodenang en "laben fosiil".

Hat liket ööder skolepkrepdiarten (Squamata), as oober uk noch bi liach tempratuuren uun a gang.

Ferlicht as diar uk noch en slach S. guentheri, diar as a wedenskap ei ians auer.

At Braghaagedisje of Tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus) as di iansagst slach uun det famile Sphenodontidae an uun det order Sphenodontia. Ööder slacher faan detdiar order san uun a leetst 150 miljuun juaren ütjstürwen. Hat as sodenang en "laben fosiil".

Hat liket ööder skolepkrepdiarten (Squamata), as oober uk noch bi liach tempratuuren uun a gang.

Ferlicht as diar uk noch en slach S. guentheri, diar as a wedenskap ei ians auer.

De Brögkherdisse of Tuatara's zien reptiele vaan de orde Sphenodontia, de familie Sphenodontidae en 't geslach Sphenodon, allewijl mèt mer twie soorte vertegenwoordeg: de Gewoene brögkherdis (Sphenodon punctuatus) en de Brothers Island-brögkherdis (Sphenodon guntheri). Ze liekene oeterlek op echte herdisse mer höbbe e väöl ander skelèt. Vreuger waore mèt väöl mie soorte euver e groet deil vaan de wereld verspreid.

De brögkherdisse zien beperk tot Nui Zieland, en sinds de massaol inveuring van zoegdiere door minse (zeker sinds de immigratie vaan de Europeane) zien ze trökgebrach tot e paar klein eilendsjes. De Brother Island-brögkherdis leef allein op Brother Island, de gewoene brögkherdis kump op väöl mier plaotse veur meh ummer op eilen. In 2005 woorte e paar brögkherdisse oetgezat in 't Karori Natuurrizzervaot, wat op 't "vasteland" ligk.

De Brögkherdisse hure same mèt hun zöstergroop de Squamata (herdisse, wörmherdisse en slange) bij de Lepidosauriërs, en de allerajdste fossiele vaan de brögkherdisse weure geach hendeg kort nao de spielting tösse Lepidosauriërs en de Archosauriërs te stoon. Wijer is de bouw vaan de brögkherdisse sinds 200 miljoen jaor aamper nog veranderd, zoetot me ze mèt rech de primitiefste levende reptiele kin neume (zuug ouch oonder).

In 't Mesozoïcum, dèks tied vaan de reptiele geneump, floreerde dees groop, die in 't Trias vörm en umvaank kraog en in 't Jura ummer mie soorte en specialisaties kroag. Zoe waore dao de Pleurosauridae, die 'nen aquatische leefstiel hadde. Aon 't ind vaan 't Jura en in 't Kriet storve de meiste femilies oet, mesjiens door de opkoms vaan echte herdisse. Oetindelek euverleefde de brögkherdisse op 't aofgelege Nui-Zieland, woe gein hoeger reptiele en gein zoegdiere veurkaome.

De brögkherdis weurt dèks es levend fossiel beneump, umtot 'r zoe awwerwets vaan karakter is. In de èngste zin vaan 't woord is ze dat evels neet: recint oonderzeuk heet opgeleverd tot de noe bestaonde twie soorte neet perceis dezelfde zien es die in 't mesozoïcum höbbe roondgeloupe, en dös welzeker in 't Kenozoïcum evolutie höbbe gekind.

't Veurnaomste versjèl is 't behaajd vaan 'n brögk in de sjedel tösse de bei slaope; dao is de soort nao verneump. Bij de Squamata is die eweggeëvolueerd. Ander teikene vaan lieg oontwikkeling zien de klein heersene en 't primitief hart, die mier aon amfibieë doen dinke. Ouch höbbe ze gein geslachsorgaone: 't menneke bevröch 't vruiwke door 't sperma laanks de cloaca oet te sjeie. Op hunne kop höbbe ze e merkwierdeg daarde oug.

't Metabolisme vaan de bieste in lankzaam, wat veur- en naodeile heet: 't veurdeil is tot ze bij lieger temperature actief kinne zien es herdisse en slange (zelfs al bij 7°C), 't groet naodeil is tot hun levesritme lankzaamer geit en ze neet zoe hel kinne loupe; dit heet waorsjijnlik deveur gezörg tot ze 't móste aoflègke tege ander reptiele.

't Menneke weurt op ze bes 60 cm laank, 't vruiwke haolt gemeinlik minstes 50 cm. Evels zien de bei geslachte meujlik vaanein te oondersjeie (ouch al door 't oontbreke vaan ńe penis, wie bove gezag) en zien de lengdeversjèlle neet zoe groet. 't Gewiech bedräög tösse de 500 en 1000 gram.

De kleur varieert vaan gries tot greun of broen. De Maorinaom tuatara beteikent "stekeldraoger", wat verwijs nao de hel punte op hunne rögk.

De Brögkherdisse of Tuatara's zien reptiele vaan de orde Sphenodontia, de familie Sphenodontidae en 't geslach Sphenodon, allewijl mèt mer twie soorte vertegenwoordeg: de Gewoene brögkherdis (Sphenodon punctuatus) en de Brothers Island-brögkherdis (Sphenodon guntheri). Ze liekene oeterlek op echte herdisse mer höbbe e väöl ander skelèt. Vreuger waore mèt väöl mie soorte euver e groet deil vaan de wereld verspreid.

La tuataras es retiles endemica a Zeland Nova. An si los sembla la plu de lezardos, los es un parte de un linia distinguida, la ordina rincosefalia. Sua nom deriva de la lingua maori e sinifia "culminas sur la dorso". La spesies singular de tuatara es la sola membro survivente de sua ordina, cual ia flori sirca 240 milion anios a ante. Sua asendente comun la plu resente con cualce otra grupo es con la scuamatos (lezardos e serpentes). Per esta razona, tuatara es interesante en la studia de evolui de lezardos e serpentes, e per la reconstrui de la apare e abituas de la diapsidos la plu temprana, un grupo de tetrapodos amnial cual inclui ance dinosauros, avias, e crocodilios.

Tuataras es brun verdin e gris, e mesura 80 cm de testa a fini de coda, e pesa asta 1.3 kg. Los ave un cresta spinosa, spesial protendente en la mases. Los ave du linias de dentes en la mandibula alta cual suprapone un linia en la mandibula basa, un ordina unica en spesies vivente. Los es ance strana per sua oio protendente fotosensante, la oio tre, cual es posible envolveda en la coordina de siclos dial e saisonal. Los pote oia, an si no orea esterna esiste, e ave cualias unica en sua sceleto, algas de cual posible retenida de sua evolui de pexes. Tuatara es a veses nomida "fosiles vivente", cual ia jeneral debate siensal. Cuando mapante sua jenom, rexercores ia descovre ce la spesies ave entre 5 e 6 bilion bases duple de la segues de ADN, cuasi du veses lo de umanas.

La tuatara (sfenodon punctato) ia es protejeda par lege de 1895. Un spesies du, la tuatara de la Isola Brothers (sfenodon gunteri) ia es reconoseda en 1989, ma de 2009, lo ia es clasida como un suspesie (sfenodon punctato gunteri). Tuataras, como multe de la animales nativa de Zeland Nova, es menasada par la perde de abitada e la introdui de xasores como la rata polinesian (rato exulans). Tuatara ia es estinguida a la tera xef, con poplas restante restrinjeda a 32 isolas de costa, asta la relasa prima a la Isola Norde de Zeland Nova en la Refujeria Karori forte sercida en 2005.

En labora costumal de manteni a la refujeria en 2008 tarda, un nido de tuatara ia es descovreda, con un enfante nova trovada la autono seguente. Esta es posible la caso prima de tuataras reproduinte en la tera savaje a la Isola Norde en plu ca 200 anios.

Tuatara are reptiles endemic tae New Zealand. Aetho resemblin maist lizards, thay are pairt o a distinct lineage, the order Rhynchocephalia.[6]

|dead-url= (help) |deadurl= (help)

Ang tuatara ay isang reptilya na endemiko sa New Zealand na bagaman kamukha ng karamihan ng mga butiki ay aktuwal na bahagi ng isang natatanging lipi na order na Rhynchocephalia.[1] Ang dalawang espesye ng mga tuatara ang tanging mga nagpapatuloy na kasapi ng order na ito na yumabong mga 200 milyong taon ang nakalilipas.[2] Ang pinaka-kamakailang karaniwang ninuno ng mga ito sa ibang mga nabubuhay na pangkat ay sa mga squamata(mga butiki at ahas). Dahil dito, ang mga tuatara ay ng malaking interes sa pag-aaral ng ebolusyon ng mga butiki at mga ahas at sa rekonstruksiyon ng hitsura at mga kagawian ng mga pinakaunang diapsida(ang pangkat na kinabibilangan rin ng mga ibon, dinosauro at mga buwaya).

Tuatara utawa sok diarani bajul iku reptil saka New Zealand sing awak'e gedhé sing urip ing kéwan. Sacara ilmiah, baya nyakup kabèh spésies kulawarga suku Rhynchocephalia kalebu uga baya iwak.

Los tuataras (genre Sphenodon) son reptils endemicos de las islas aledanhas en Nòva Zelanda, pertenecientes a la familha Sphenodontidae. Lo significat de lo sieu nom comun proven del maòri e vòl dire "esquina espinosa". A primièra vista (per convergéncia evolutiva) son sembladas a las iguanas, que, malgrat aiçò, son amb el pas emparentadas. Mesuran unes 70 cm de longitud e son insectivòrs e carnivòrs.

Las doas d'espècias actualas de tuataras e l'extinta coneguda an de parents fòrça prèps qu'existiguèron fa ja 200 milions d'ans, al parelh dels dinosaures. En aquestas epòcas abitavan lo supercontinente de Gondwana en s'avent distribuit, segontes sembla, dempuèi l'airal que correspond uèi en America del Sud en passant per l'Antartida fins a Austràlia. Al se separar d'Austràlia per deriva continental, Nòva Zelanda se convertiriá en l'unic reducte actual, motiu que se qualifica per el a aquestes animals coma de fossils viuentes.

Ang tuatara ay isang reptilya na endemiko sa New Zealand na bagaman kamukha ng karamihan ng mga butiki ay aktuwal na bahagi ng isang natatanging lipi na order na Rhynchocephalia. Ang dalawang espesye ng mga tuatara ang tanging mga nagpapatuloy na kasapi ng order na ito na yumabong mga 200 milyong taon ang nakalilipas. Ang pinaka-kamakailang karaniwang ninuno ng mga ito sa ibang mga nabubuhay na pangkat ay sa mga squamata(mga butiki at ahas). Dahil dito, ang mga tuatara ay ng malaking interes sa pag-aaral ng ebolusyon ng mga butiki at mga ahas at sa rekonstruksiyon ng hitsura at mga kagawian ng mga pinakaunang diapsida(ang pangkat na kinabibilangan rin ng mga ibon, dinosauro at mga buwaya).

Tuatara are reptiles endemic tae New Zealand. Aetho resemblin maist lizards, thay are pairt o a distinct lineage, the order Rhynchocephalia.

টুৱাটেৰা (মাওৰি, ইংৰাজী: tuatara) নিউজিলেণ্ডৰ এবিধ নিজা-থলুৱা সৰীসৃপ। জেঠীজাত জীৱৰ দৰে দেখিলেও ইহঁত বেলেগ এটা গুৰি-গোষ্ঠীৰ, যিটো হ’ল ৰাইংক’চেফালিয়া বৰ্গ।[2] ইহঁতৰ নামটো মাওৰি ভাষাৰ পৰা আহিছে যাৰ অৰ্থ "পিঠিত শৃংগ"।[3] ২০ কোটি বছৰমান আগতে উন্নতি লাভ কৰা বৰ্গটোৰ এটাই টুৱাটেৰাৰ প্ৰজাতি বাচি আছে।[4] জীৱৰ গোটেইবিলাক গোটৰ ভিতৰত ইহঁতৰ আৰু ইস্কুৱামেটৰ (সাপ আৰু জেঠীজাত জীৱৰ) একেবাৰে শেহতীয়া পূৰ্বপুৰুষ একেই।[5] এই কাৰণে জেঠীজাত জীৱৰ আৰু সাপৰ অধ্যয়নত আৰু প্ৰথম ডায়েপ্সিড (ডাইনাচৰ, য’ত চৰাইও পৰে আৰু ঘৰীয়ালজাত জীৱক সাঙুৰি লোৱা এটা এম্নিয়ট চাৰিঠেঙীয়া জীৱৰ গোট) বিলাকৰ চেহেৰা আৰু অভ্যাসৰ পুনৰনিৰ্মানৰ বাবে টুৱাটেৰাক গুৰুত্ব দিয়া হয়।

টুৱাটেৰাৰ বৰণ সেউজীয়াৰ দৰে মটীয়া আৰু ধোঁৱাবুলীয়া, ইয়াৰ দীঘ মূৰৰ পৰা নেজলৈকে ৮০ ছে.মি. (৩১ ইঞ্চি) আৰু ওজন ১.৩ কেজি।[6] ইহঁতৰ কাঁইটীয়া জঁ থাকে, বিশেষকৈ মতাবিলাকত বেছিকৈ দেখি। ইহঁতৰ ওপৰৰ পাৰিটোত দুশাৰীকৈ দাঁত থাকে আৰু তলৰ পাৰিটোত ওপৰৰ পাৰিৰ মাজেৰে এশাৰী দাঁত থাকে, এনেকুৱা আন কোনো জীয়াই থকা জীৱত নেদেখি। আচহুৱাকৈ ইহঁতৰ দেখা যোৱা ফটোৰিচেপ্টিভ তৃতীয় চকুও থাকে যিটোৱে চিৰ্কাডিয়ান আৰু ঋতুগত চক্ৰবোৰ কৰায় বোলে ভবা গৈছে। বাহিৰা কান নাই যদিও ইহঁতে শুনিব পাৰে আৰু ইহঁতৰ লাওখোলাত কিছুমান ইউনিক ঠাচ থাকে যাৰ কিছুমান বিৱৰ্তনগতভাবে মাছ অৱস্থাৰ পৰা বজাই ৰাখিছে যেন দেখা গৈছে। যদিও টুৱাটেৰাক কেতিয়াবা "জীৱন্ত জীৱাশ্ম" বুলি কোৱা হয়, শেহতীয়া দেহতাত্ত্বিক অধ্যয়নে ইহঁত মেছ’জৈক যুগৰ পৰা বহুত সলনি হোৱা বুলি দেখুৱাইছে।[7][8][9] ইয়াৰ জননকোষ মেপ কৰি থাকোতে গৱেষকসকলে এই প্ৰজাতিটোৰ খাৰযোৰৰ সংখ্যা ৫ৰ পৰা ৬শ কোটিটা আছে মানুহটোক দুগুণ।[10]

The tuatara Sphenodon punctatus has been protected by law since 1895.[11][12] A second species, S. guntheri, was recognised in 1989,[6] but since 2009 it has been reclassified as a subspecies.[13][14] Tuatara, like many of New Zealand's native animals, are threatened by habitat loss and introduced predators, such as the Polynesian rat (Rattus exulans). Tuatara were extinct on the mainland, with the remaining populations confined to 32 offshore islands[4] until the first mainland release into the heavily fenced and monitored Karori Sanctuary in 2005.[15]

During routine maintenance work at Karori Sanctuary in late 2008, a tuatara nest was uncovered,[16] with a hatchling found the following autumn.[17] This is thought to be the first case of tuatara successfully breeding in the wild on the New Zealand mainland in over 200 years.

টুৱাটেৰা (মাওৰি, ইংৰাজী: tuatara) নিউজিলেণ্ডৰ এবিধ নিজা-থলুৱা সৰীসৃপ। জেঠীজাত জীৱৰ দৰে দেখিলেও ইহঁত বেলেগ এটা গুৰি-গোষ্ঠীৰ, যিটো হ’ল ৰাইংক’চেফালিয়া বৰ্গ। ইহঁতৰ নামটো মাওৰি ভাষাৰ পৰা আহিছে যাৰ অৰ্থ "পিঠিত শৃংগ"। ২০ কোটি বছৰমান আগতে উন্নতি লাভ কৰা বৰ্গটোৰ এটাই টুৱাটেৰাৰ প্ৰজাতি বাচি আছে। জীৱৰ গোটেইবিলাক গোটৰ ভিতৰত ইহঁতৰ আৰু ইস্কুৱামেটৰ (সাপ আৰু জেঠীজাত জীৱৰ) একেবাৰে শেহতীয়া পূৰ্বপুৰুষ একেই। এই কাৰণে জেঠীজাত জীৱৰ আৰু সাপৰ অধ্যয়নত আৰু প্ৰথম ডায়েপ্সিড (ডাইনাচৰ, য’ত চৰাইও পৰে আৰু ঘৰীয়ালজাত জীৱক সাঙুৰি লোৱা এটা এম্নিয়ট চাৰিঠেঙীয়া জীৱৰ গোট) বিলাকৰ চেহেৰা আৰু অভ্যাসৰ পুনৰনিৰ্মানৰ বাবে টুৱাটেৰাক গুৰুত্ব দিয়া হয়।

টুৱাটেৰাৰ বৰণ সেউজীয়াৰ দৰে মটীয়া আৰু ধোঁৱাবুলীয়া, ইয়াৰ দীঘ মূৰৰ পৰা নেজলৈকে ৮০ ছে.মি. (৩১ ইঞ্চি) আৰু ওজন ১.৩ কেজি। ইহঁতৰ কাঁইটীয়া জঁ থাকে, বিশেষকৈ মতাবিলাকত বেছিকৈ দেখি। ইহঁতৰ ওপৰৰ পাৰিটোত দুশাৰীকৈ দাঁত থাকে আৰু তলৰ পাৰিটোত ওপৰৰ পাৰিৰ মাজেৰে এশাৰী দাঁত থাকে, এনেকুৱা আন কোনো জীয়াই থকা জীৱত নেদেখি। আচহুৱাকৈ ইহঁতৰ দেখা যোৱা ফটোৰিচেপ্টিভ তৃতীয় চকুও থাকে যিটোৱে চিৰ্কাডিয়ান আৰু ঋতুগত চক্ৰবোৰ কৰায় বোলে ভবা গৈছে। বাহিৰা কান নাই যদিও ইহঁতে শুনিব পাৰে আৰু ইহঁতৰ লাওখোলাত কিছুমান ইউনিক ঠাচ থাকে যাৰ কিছুমান বিৱৰ্তনগতভাবে মাছ অৱস্থাৰ পৰা বজাই ৰাখিছে যেন দেখা গৈছে। যদিও টুৱাটেৰাক কেতিয়াবা "জীৱন্ত জীৱাশ্ম" বুলি কোৱা হয়, শেহতীয়া দেহতাত্ত্বিক অধ্যয়নে ইহঁত মেছ’জৈক যুগৰ পৰা বহুত সলনি হোৱা বুলি দেখুৱাইছে। ইয়াৰ জননকোষ মেপ কৰি থাকোতে গৱেষকসকলে এই প্ৰজাতিটোৰ খাৰযোৰৰ সংখ্যা ৫ৰ পৰা ৬শ কোটিটা আছে মানুহটোক দুগুণ।

The tuatara Sphenodon punctatus has been protected by law since 1895. A second species, S. guntheri, was recognised in 1989, but since 2009 it has been reclassified as a subspecies. Tuatara, like many of New Zealand's native animals, are threatened by habitat loss and introduced predators, such as the Polynesian rat (Rattus exulans). Tuatara were extinct on the mainland, with the remaining populations confined to 32 offshore islands until the first mainland release into the heavily fenced and monitored Karori Sanctuary in 2005.

During routine maintenance work at Karori Sanctuary in late 2008, a tuatara nest was uncovered, with a hatchling found the following autumn. This is thought to be the first case of tuatara successfully breeding in the wild on the New Zealand mainland in over 200 years.

பிடரிக்கோடன் (Tuatara) என்பது நியூசிலாந்து நாட்டில் மட்டுமே வாழும் ஊர்வன வகுப்பைச் சேர்ந்த விலங்கு ஆகும். இது பார்ப்பதற்கு ஓணான், ஓந்தி முதலிய பல்லிகளைப் போலவே தோன்றினாலும், அவ்வினங்களில் இருந்து வேறுபடும் நீள்மூக்குத்தலையி எனும் வரிசையில் வரும் விலங்கு ஆகும்.[1][2] 200 மில்லியன் ஆண்டுகளுக்கு முன்னர் பல்கிச் செழித்திருந்த நீள்மூக்குத்தலையி வரிசையில் இரு பிடரிக்கோடன் இனங்கள் மட்டுமே இன்றும் வாழ்ந்து கொண்டிருப்பவை.[2] இன்று வாழும் உயிர்களில் இவற்றின் அண்மிய மரபுவழி உறவு கொண்டவை பாம்புகளையும் பல்லியோந்திகளையும் உள்ளடக்கிய செதிலுடைய ஊர்வன (Squamata) மட்டுமே. இதனால் பல்லி பாம்பு இனங்களின் மரபுவழித் தோன்றலையும் படிவளர்ச்சியையும் ஆய்வதற்கும், அவற்றின் மூதாதைய இனங்களின் புறத்தோற்றம், வாழியல் முறைகள் போன்றவற்றை அறிந்து கொள்வதற்கும் பிடரிக்கோடன்களை ஆராய்ச்சியாளர்கள் ஆர்வத்துடன் நோக்குகின்றனர். பறவைகள், தொன்மாக்கள், முதலைகள் போன்ற மிகப்பழைய மரபில் வந்த உயிரினங்களின் மூதாதையரைப் பற்றி அறிந்து கொள்ளவும் இவை உதவுகின்றன. இவ்விலங்கின் மண்டையோட்டை மட்டும் வைத்து வைத்து முதலில் பிடரிக்கோடன்களையும் பல்லிகளுடன் வகைப்படுத்தியிருந்தனர்.[3] பின்னர் ஆய்வின்போது இவற்றின் பல உடற்கூறுகள் ஊர்வனவற்றின் பொது மூதாதையருடையவை என்றும் வேறு ஊர்வனவற்றில் இல்லாதவை என்றும் அறிந்து தனியாக வகைப்படுத்தியுள்ளனர்.

பிடரிக்கோடன்கள் மரப்பழுப்பு நிறத்தோற்றம் கொண்டவை. தலை முதல் வாலின் நுனி மட்டிலும் 80 செ.மீ. நீளம் வரை இருக்கின்றன. இவற்றின் உயர்ந்த அளவு எடை 1.3 கிலோ ஆகும்.[5] இவ்விலங்குகளின் புறமுதுகுப் பகுதியில் மலைகளில் உள்ள கொடுமுடிகளைப் (கோடு) போன்ற உச்சி இருக்கும். குறிப்பாக ஆண் விலங்குகளில் இது மிகுந்து இருக்கும். இதன் காரணமாகவே இவற்றை நியூசிலாந்துப் பழங்குடியினரின் மொழியான மௌரியில் "முதுகில் கொடுமுடிகள்" எனும் பொருளில் 'டுவாட்டரா' என்று அழைக்கின்றனர்.[6] இவ்விலங்குகளுக்கான ஆங்கிலப் பெயராகவும் 'டுவாட்டரா' என்பது நிலைபெற்றுள்ளது. இவற்றின் மேல்தாடையில் உள்ள இருவரிசைப்பற்கள் கீழ்த்தாடையில் உள்ள ஒருவரிசைப்பற்களின் மீது அண்டி இருக்கும் பல் அமைப்பு வேறு எந்த விலங்கிலும் காணப்படாத ஒன்று. மேலும் இவற்றின் நெற்றிப்பகுதியில் இருக்கும் "மூன்றாவது கண்" என்று கருதப்படும் உறுப்பும் மிகவும் விந்தையானதாகும். இதன் பயன் என்னவென்று அறிவதற்கு இன்னும் ஆய்வுகள் நடந்து வருகின்றன. பகல் இரவு மாற்றத்திற்கேற்ப உடல் இயக்கங்களை அமைத்துக் கொள்ளும் நாடொறு இசைவுக்கும் (circadian rhythm), வெப்பநிலைச் சுழற்சிக்கேற்ப நடத்தையை அமைத்துக் கொள்ளவும் உதவும் உறுப்பாக இருக்கலாம் எனக் கருதப்படுகிறது. இவ்விலங்குகளுக்குப் புறக்காதுகள் இல்லாவிட்டாலும் இவற்றின் எலும்புக்கூட்டில் உள்ள விந்தையான அமைப்பினால் இவற்றுக்குக் கேட்கும் திறன் உண்டு. படிவளர்ச்சியில் மீன்களின் வரிசையில் இருக்கும் சில பண்புகள் இவை என்பது குறிப்பிடத்தக்கது. இவற்றை வாழும் படிவங்கள் எனச் சிலர் அழைத்த போதிலும், உண்மையில் இடையூழிக் காலத்தில் இருந்து இவற்றின் மரபணுக்கள் மாறி வந்திருப்பதை ஆய்வுகள் காட்டுகின்றன.

இவை அழியும் தருவாயில் உள்ள விலங்குகள்.[7][8] 1989-ம் ஆண்டு வரை இவற்றின் இரண்டாவது சிற்றினம் கண்டுபிடிக்கப்படவில்லை.[5] வாழிட மாற்றம், நியூசிலாந்துத்தீவுகளுக்கு வெளியிலிருந்து மனிதர்கள் மூலமாக உள்நுழைந்த பாலினீசிய எலி போன்ற கோண்மாக்கள், போட்டி உயிரினங்கள் ஆகியவற்றின் விளைவாக, நியூசிலாந்தின் பிற அகணிய உயிரினங்களைப் போலவே பிடரிக்கோடன் இனங்களும் அழிவாய்ப்பைக் கொண்டுள்ளன. ஒரு கட்டத்தில், நியூசிலாந்தின் முதன்மைத் தீவில் இவை முழுவதுமாக அற்றுப்போய், துணைத்தீவுகளில் மட்டுமே எஞ்சியிருந்தன.[2] வேலியிட்டுக் கண்காணிக்கப்படும் கரோரி கானுயிர் காப்பகத்தில் 2005-ஆம் ஆண்டு இவற்றை அறிமுகப்படுத்தியதில் இருந்து நியூசிலாந்தின் முதன்மைத் தீவிலும் இவை வாழ்ந்து வருகின்றன.[9] 2008-ல் இக்காப்பகத்தில் சில பேணுகைப் பணிகளை மேற்கொள்ளும்போது ஒரு பிடரிக்கோடன் முட்டைக்கூட்டைக் கண்டனர்.[10] சில நாட்களுக்குப்பின் பார்ப்பு[11] (ஊர்வனக்குஞ்சு) ஒன்றையும் கண்டனர்.[12] கடந்த 200 ஆண்டுகளில் நியூசிலாந்து முதன்மைத்தீவில் பிடரிக்கோடன் இயல்பில் வெற்றியுடன் முட்டையிட்டுக் குஞ்சுபொரித்தது இதுவே முதல் முறையாகும்.

பிடரிக்கோடன் (Tuatara) என்பது நியூசிலாந்து நாட்டில் மட்டுமே வாழும் ஊர்வன வகுப்பைச் சேர்ந்த விலங்கு ஆகும். இது பார்ப்பதற்கு ஓணான், ஓந்தி முதலிய பல்லிகளைப் போலவே தோன்றினாலும், அவ்வினங்களில் இருந்து வேறுபடும் நீள்மூக்குத்தலையி எனும் வரிசையில் வரும் விலங்கு ஆகும். 200 மில்லியன் ஆண்டுகளுக்கு முன்னர் பல்கிச் செழித்திருந்த நீள்மூக்குத்தலையி வரிசையில் இரு பிடரிக்கோடன் இனங்கள் மட்டுமே இன்றும் வாழ்ந்து கொண்டிருப்பவை. இன்று வாழும் உயிர்களில் இவற்றின் அண்மிய மரபுவழி உறவு கொண்டவை பாம்புகளையும் பல்லியோந்திகளையும் உள்ளடக்கிய செதிலுடைய ஊர்வன (Squamata) மட்டுமே. இதனால் பல்லி பாம்பு இனங்களின் மரபுவழித் தோன்றலையும் படிவளர்ச்சியையும் ஆய்வதற்கும், அவற்றின் மூதாதைய இனங்களின் புறத்தோற்றம், வாழியல் முறைகள் போன்றவற்றை அறிந்து கொள்வதற்கும் பிடரிக்கோடன்களை ஆராய்ச்சியாளர்கள் ஆர்வத்துடன் நோக்குகின்றனர். பறவைகள், தொன்மாக்கள், முதலைகள் போன்ற மிகப்பழைய மரபில் வந்த உயிரினங்களின் மூதாதையரைப் பற்றி அறிந்து கொள்ளவும் இவை உதவுகின்றன. இவ்விலங்கின் மண்டையோட்டை மட்டும் வைத்து வைத்து முதலில் பிடரிக்கோடன்களையும் பல்லிகளுடன் வகைப்படுத்தியிருந்தனர். பின்னர் ஆய்வின்போது இவற்றின் பல உடற்கூறுகள் ஊர்வனவற்றின் பொது மூதாதையருடையவை என்றும் வேறு ஊர்வனவற்றில் இல்லாதவை என்றும் அறிந்து தனியாக வகைப்படுத்தியுள்ளனர்.

Sēo brycgāðexe (on Nīwum Englisce hāteþ "tuatara"; his Englisca nama cymþ fram Þēodsce and Niðerlendisce) is slincend þe wunaþ synderlīce on þǣre Norþīege Nīwes Sǣlandes. Þēah hēo hæfþ andsīne gelīc āðexan, nis is hēo āðexe wesan gesmēad.

Hēo is grēnbrūn and 80 hundtēontigoðena metera lang. Hēo wegeþ swā micel swā 1.3 þūsenda cornwihta.[2] Brycgāðexan habbaþ tindihtne camb on bæce, þe is ānlīce beorht on werum.

Sēo brycgāðexe (on Nīwum Englisce hāteþ "tuatara"; his Englisca nama cymþ fram Þēodsce and Niðerlendisce) is slincend þe wunaþ synderlīce on þǣre Norþīege Nīwes Sǣlandes. Þēah hēo hæfþ andsīne gelīc āðexan, nis is hēo āðexe wesan gesmēad.

Hēo is grēnbrūn and 80 hundtēontigoðena metera lang. Hēo wegeþ swā micel swā 1.3 þūsenda cornwihta. Brycgāðexan habbaþ tindihtne camb on bæce, þe is ānlīce beorht on werum.

Tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus) are reptiles endemic to New Zealand. Despite their close resemblance to lizards, they are part of a distinct lineage, the order Rhynchocephalia.[7] The name tuatara is derived from the Māori language and means "peaks on the back".[8] The single extant species of tuatara is the only surviving member of its order.[9] Rhynchocephalians originated during the Triassic (~250 million years ago), reached worldwide distribution and peak diversity during the Jurassic and, with the exception of tuatara, were extinct by 60 million years ago.[10][11][12] Their closest living relatives are squamates (lizards and snakes).[13] For this reason, tuatara are of interest in the study of the evolution of lizards and snakes, and for the reconstruction of the appearance and habits of the earliest diapsids, a group of amniote tetrapods that also includes dinosaurs (including birds) and crocodilians.

Tuatara are greenish brown and grey, and measure up to 80 cm (31 in) from head to tail-tip and weigh up to 1.3 kg (2.9 lb)[14] with a spiny crest along the back, especially pronounced in males. They have two rows of teeth in the upper jaw overlapping one row on the lower jaw, which is unique among living species. They are able to hear, although no external ear is present, and have unique features in their skeleton, some of them apparently evolutionarily retained from fish.

Tuatara are sometimes referred to as "living fossils",[7] which has generated significant scientific debate. This term is currently deprecated among paleontologists and evolutionary biologists. Although tuatara have preserved the morphological characteristics of their Mesozoic ancestors (240–230 million years ago), there is no evidence of a continuous fossil record to support this.[15][16] The species has between 5 and 6 billion base pairs of DNA sequence, nearly twice that of humans.[17]

The tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus) has been protected by law since 1895.[18][19] A second species, the Brothers Island tuatara S. guntheri, (Buller, 1877), was recognised in 1989,[14] but since 2009 it has been reclassified as a subspecies (S.p. guntheri).[20][21] Tuatara, like many of New Zealand's native animals, are threatened by habitat loss and introduced predators, such as the Polynesian rat (Rattus exulans). Tuatara were extinct on the mainland, with the remaining populations confined to 32 offshore islands[12] until the first North Island release into the heavily fenced and monitored Karori Wildlife Sanctuary (now named "Zealandia") in 2005.[22]

During routine maintenance work at Zealandia in late 2008, a tuatara nest was uncovered,[23] with a hatchling found the following autumn.[24] This is thought to be the first case of tuatara successfully breeding in the wild on New Zealand's North Island in over 200 years.[23]

Tuatara are the largest reptile in New Zealand.[25] Adult S. punctatus males measure 61 cm (24 in) in length and females 45 cm (18 in).[26] Tuatara are sexually dimorphic, males being larger.[26] The San Diego Zoo even cites a length of up to 80 cm (31 in).[27] Males weigh up to 1 kg (2.2 lb), and females up to 0.5 kg (1.1 lb).[26] Brother's Island tuatara are slightly smaller, weighing up to 660 g (1.3 lb).[28]

Their lungs have a single chamber with no bronchi.[29]

The tuatara's greenish brown colour matches its environment, and can change over its lifetime. Tuatara shed their skin at least once per year as adults,[30] and three or four times a year as juveniles. Tuatara sexes differ in more than size. The spiny crest on a tuatara's back, made of triangular, soft folds of skin, is larger in males, and can be stiffened for display. The male abdomen is narrower than the female's.[31]

The ancestor of diapsids had a skull with two openings in the temporal region – upper and lower temporal fenestra on each side of the skull bounded by complete arches. The upper jaw is firmly attached to the posterior of skull.[26] This makes for a very rigid, inflexible construction. The skull of the tuatara has a similar structure, with both upper and lower temporal openings.[9][32]: 113 However, the lower temporal bar (sometimes called the cheek bone) is incomplete in some fossil Rhynchocephalia, suggesting its presence in the tuatara is a distinctive (autapomorphic) feature rather than one inherited from a common ancestor.[33]

The tip of the upper jaw is beak-like and separated from the remainder of the jaw by a notch.[9] There is a single row of teeth in the lower jaw and a double row in the upper, with the bottom row fitting perfectly between the two upper rows when the mouth is closed.[9] This specific tooth arrangement is not seen in any other reptile;[9] although most snakes have a double row of teeth in their upper jaws, their arrangement and function is different from the tuatara's.

The structure of the jaw joint allows the lower jaw to slide forwards after it has closed between the two upper rows of teeth.[34] This mechanism allows the jaws to shear through chitin and bone. [26] Fossils indicate that the jaw mechanism began evolving at least 200 million years ago.[35] The teeth are not replaced. As their teeth wear down, older tuatara have to switch to softer prey such as earthworms, larvae, and slugs, and eventually have to chew their food between smooth jaw bones.[36] It is a common misconception that tuatara lack teeth and instead have sharp projections on the jaw bone,[37] though histology shows that they have enamel and dentine with pulp cavities.[38]

The brain of Sphenodon fills only half of the volume of its endocranium.[39] This proportion has actually been used by paleontologists trying to estimate the volume of dinosaur brains based on fossils.[39] However, the proportion of the tuatara endocranium occupied by its brain may not be a very good guide to the same proportion in Mesozoic dinosaurs since modern birds are surviving dinosaurs but have brains which occupy a much greater relative volume in the endocranium.[39]

The eyes can focus independently, and are specialised with three types of photoreceptive cells, all with fine structural characteristics of retinal cone cells[40] used for both day and night vision, and a tapetum lucidum which reflects onto the retina to enhance vision in the dark. There is also a third eyelid on each eye, the nictitating membrane. Five visual opsin genes are present, suggesting good colour vision, possibly even at low light levels.[11]

The tuatara has a third eye on the top of its head called the parietal eye. It has its own lens, a parietal plug which resembles a cornea,[41] retina with rod-like structures, and degenerated nerve connection to the brain. The parietal eye is visible only in hatchlings, which have a translucent patch at the top centre of the skull. After four to six months, it becomes covered with opaque scales and pigment.[26] Its use is unknown, but it may be useful in absorbing ultraviolet rays to produce vitamin D,[8] as well as to determine light/dark cycles, and help with thermoregulation.[26] Of all extant tetrapods, the parietal eye is most pronounced in the tuatara. It is part of the pineal complex, another part of which is the pineal gland, which in tuatara secretes melatonin at night.[26] Some salamanders have been shown to use their pineal bodies to perceive polarised light, and thus determine the position of the sun, even under cloud cover, aiding navigation.[42]

Together with turtles, the tuatara has the most primitive hearing organs among the amniotes. There is no eardrum and no earhole,[37] they lack a tympanum, and the middle ear cavity is filled with loose tissue, mostly adipose (fatty) tissue. The stapes comes into contact with the quadrate (which is immovable), as well as the hyoid and squamosal. The hair cells are unspecialised, innervated by both afferent and efferent nerve fibres, and respond only to low frequencies. Though the hearing organs are poorly developed and primitive with no visible external ears, they can still show a frequency response from 100 to 800 Hz, with peak sensitivity of 40 dB at 200 Hz.[43]

Animals that depend on the sense of smell to capture prey, escape from predators or simply interact with the environment they inhabit, usually have many odorant receptors. These receptors are expressed in the dendritic membranes of the neurons for the detection of odours. The tuatara has several hundred receptors, around 472, a number more similar to what birds have than to the large number of receptors that turtles and crocodiles may have.[11]

The tuatara spine is made up of hourglass-shaped amphicoelous vertebrae, concave both before and behind.[37] This is the usual condition of fish vertebrae and some amphibians, but is unique to tuatara within the amniotes. The vertebral bodies have a tiny hole through which a constricted remnant of the notochord passes; this was typical in early fossil reptiles, but lost in most other amniotes.[44]

The tuatara has gastralia, rib-like bones also called gastric or abdominal ribs,[45] the presumed ancestral trait of diapsids. They are found in some lizards, where they are mostly made of cartilage, as well as crocodiles and the tuatara, and are not attached to the spine or thoracic ribs. The true ribs are small projections, with small, hooked bones, called uncinate processes, found on the rear of each rib.[37] This feature is also present in birds. The tuatara is the only living tetrapod with well-developed gastralia and uncinate processes.

In the early tetrapods, the gastralia and ribs with uncinate processes, together with bony elements such as bony plates in the skin (osteoderms) and clavicles (collar bone), would have formed a sort of exoskeleton around the body, protecting the belly and helping to hold in the guts and inner organs. These anatomical details most likely evolved from structures involved in locomotion even before the vertebrates ventured onto land. The gastralia may have been involved in the breathing process in early amphibians and reptiles. The pelvis and shoulder girdles are arranged differently from those of lizards, as is the case with other parts of the internal anatomy and its scales.[46]

The spiny plates on the back and tail of the tuatara resemble those of a crocodile more than a lizard, but the tuatara shares with lizards the ability to break off its tail when caught by a predator, and then regenerate it. The regrowth takes a long time and differs from that of lizards. Well illustrated reports on tail regeneration in tuatara have been published by Alibardi and Meyer-Rochow.[47][48] The cloacal glands of tuatara have a unique organic compound named tuataric acid.

Currently, there are two means of determining the age of tuatara. Using microscopic inspection, hematoxylinophilic rings can be identified and counted in both the phalanges and the femur. Phalangeal hematoxylinophilic rings can be used for tuatara up to ages 12–14 years, as they cease to form around this age. Femoral rings follow a similar trend, however they are useful for tuatara up to ages 25–35 years. Around that age, femoral rings cease to form.[49] Further research on age determination methods for tuatara is required, as tuatara have lifespans much longer than 35 years (ages up to 60[8] are common, and captive tuatara have lived to over 100 years[50][51][52]). One possibility could be via examination of tooth wear, as tuatara have fused sets of teeth.

Tuatara, along with other now-extinct members of the order Sphenodontia, belong to the superorder Lepidosauria, the only surviving taxon within Lepidosauromorpha. Squamates and tuatara both show caudal autotomy (loss of the tail-tip when threatened), and have transverse cloacal slits.[26] The origin of the tuatara probably lies close to the split between the Lepidosauromorpha and the Archosauromorpha. Though tuatara resemble lizards, the similarity is superficial, because the family has several characteristics unique among reptiles. The typical lizard shape is very common for the early amniotes; the oldest known fossil of a reptile, the Hylonomus, resembles a modern lizard.[54]

Tuatara were originally classified as lizards in 1831 when the British Museum received a skull.[55] The genus remained misclassified until 1867, when A.C.L.G. Günther of the British Museum noted features similar to birds, turtles, and crocodiles. He proposed the order Rhynchocephalia (meaning "beak head") for the tuatara and its fossil relatives.[9]

At one point many disparately related species were incorrectly referred to the Rhynchocephalia, resulting in what taxonomists call a "wastebasket taxon".[56] Williston proposed the Sphenodontia to include only tuatara and their closest fossil relatives in 1925.[56] However, Rhynchocephalia is the older name[9] and in widespread use today. Sphenodon is derived from the Greek for "wedge" (σφήν, σφηνός/sphenos) and "tooth" (ὀδούς, ὀδόντος/odontos).[57]

Tuatara have been referred to as living fossils,[7] due to a perception that they retain many basal characteristics from around the time of the squamate–rhynchocephalian split (240 MYA).[10][58] Morphometric analyses of variation in jaw morphology among tuatara and extinct rhynchocephalian relatives have been argued to demonstrate morphological conservatism and support for the classification of tuatara as a 'living fossil',[16] but the reliability of these results has been criticised and debated.[59][60] Paleontological research on rhynchocephalians indicates that the group has undergone a variety of changes throughout the Mesozoic,[61][62][63][15] and the rate of molecular evolution for tuatara has been estimated to be among the fastest of any animal yet examined.[64][65] However, a 2020 analysis of the tuatara genome reached the opposite conclusion: That its rate of DNA substitutions per site is actually lower than for any analysed squamate.[11] Many of the niches occupied by lizards today were formerly held by rhynchocephalians. There was even a successful group of aquatic rhynchocephalians known as pleurosaurs, which differed markedly from living tuatara. Tuatara show cold-weather adaptations that allow them to thrive on the islands of New Zealand; these adaptations may be unique to tuatara since their sphenodontian ancestors lived in the much warmer climates of the Mesozoic. For instance, Palaeopleurosaurus appears to have had a much shorter lifespan compared to the modern tuatara.[66] Ultimately most scientists consider the phrase 'living fossil' to be unhelpful and misleading.[67][68]

A species of sphenodontine is known from the Miocene Saint Bathans Fauna. Whether it is referable to Sphenodon proper is not entirely clear, but is likely to be closely related to tuatara.[69]

While there is currently considered to be only one living species of tuatara, two species were previously identified: Sphenodon punctatus, or northern tuatara, and the much rarer Sphenodon guntheri, or Brothers Island tuatara, which is confined to North Brother Island in Cook Strait.[70] The specific name punctatus is Latin for "spotted",[71] and guntheri refers to German-born British herpetologist Albert Günther.[72] A 2009 paper re-examined the genetic bases used to distinguish the two supposed species of tuatara, and concluded they only represent geographic variants, and only one species should be recognized.[21] Consequently, the northern tuatara was re-classified as Sphenodon punctatus punctatus and the Brothers Island tuatara as Sphenodon punctatus guntheri. Individuals from Brothers Island could also not be distinguished from other modern and fossil samples based on jaw morphology.[59]

The Brothers Island tuatara has olive brown skin with yellowish patches, while the colour of the northern tuatara ranges from olive green through grey to dark pink or brick red, often mottled, and always with white spots.[22][26][30] In addition, the Brothers Island tuatara is considerably smaller.[28] An extinct species of Sphenodon was identified in November 1885 by William Colenso, who was sent an incomplete subfossil specimen from a local coal mine. Colenso named the new species S. diversum.[73]

The most abundant LINE element in the tuatara is L2 (10%). Most of them are interspersed and can remain active. The longest L2 element found is 4 kb long and 83% of the sequences had ORF2p completely intact. The CR1 element is the second most repeated (4%). Phylogenetic analysis shows that these sequences are very different from those found in other nearby species such as lizards. Finally, less than 1% are elements belonging to L1, a low percentage since these elements tend to predominate in placental mammals.[11]

Usually, the predominant LINE elements are the CR1, contrary to what has been seen in the tuatara. This suggests that perhaps the genome repeats of sauropsids were very different compared to mammals, birds and lizards.[11]

The genes of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) are known to play roles in disease resistance, mate choice, and kin recognition in various vertebrate species. Among known vertebrate genomes, MHCs are considered one of the most polymorphic.[74][75] In the tuatara, 56 MHC genes have been identified; some of which are similar to MHCs of amphibians and mammals. Most MHCs that were annotated in the tuatara genome are highly conserved, however there is large genomic rearrangement observed in distant lepidosauria lineages.[11]

Many of the elements that have been analyzed are present in all amniotes, most are mammalian interspersed repeats or MIR, specifically the diversity of MIR subfamilies is the highest that has been studied so far in an amniote. 16 families of SINEs that were recently active have also been identified.[11]

The tuatara has 24 unique families of DNA transposons, and at least 30 subfamilies were recently active. This diversity is greater than what has been found in other amniotes and in addition, thousands of identical copies of these transposons have been analyzed, suggesting to researchers that there is recent activity.[11]

Around 7,500 LTRs have been identified, including 450 endogenous retroviruses (ERVs). Studies in other Sauropsida have recognized a similar number but nevertheless, in the genome of the tuatara it has been found a very old clade of retrovirus known as Spumavirus.[11]

More than 8,000 non-coding RNA-related elements have been identified in the tuatara genome, of which the vast majority, about 6,900, are derived from recently active transposable elements. The rest are related to ribosomal, spliceosomal and signal recognition particle RNA.[11]

The mitochondrial genome of the genus Sphenodon is approximately 18,000 bp in size and consists of 13 protein-coding genes, 2 ribosomal RNA and 22 transfer RNA genes.[11]

DNA methylation is a very common modification in animals and the distribution of CpG sites within genomes affects this methylation. Specifically, 81% of these CpG sites have been found to be methylated in the tuatara genome. Recent publications propose that this high level of methylation may be due to the amount of repeating elements that exist in the genome of this animal. This pattern is closer to what occurs in organisms such as zebrafish, about 78%, while in humans it is only 70%.[11]