en

names in breadcrumbs

Perception Channels: tactile ; chemical

Other Physical Features: endothermic ; bilateral symmetry

Key Reproductive Features: gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); sexual

Diversity of Living Camelids

The Camelidae (camels and relatives) are sufficiently distinct from other families in the mammal order Artiodactyla that they are placed in their own suborder, Tylopoda ("padded foot"). This suborder includes only the family Camelidae, which is divided into two tribes, the Camelini and Lamini. The Camelini includes just two living representatives, the Bactrian Camel (Camelus bactrianus) and the Dromedary (Camelus dromedarius). The Lamini includes four species: Guanaco (Lama guanicoe), Llama (Lama glama), Viçuna (Vicugna vicugna), and Alpaca (Vicugna pacos).

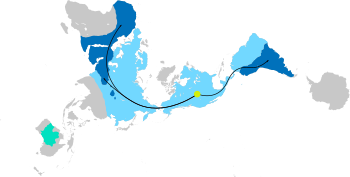

The earliest camelids evolved in North America, where they flourished for forty to fifty million years, with the last known North American camelids disappearing only around 10,000 years ago. Six to seven million years ago, camels that would give rise to the Dromedary and Bactrian Camel spread into Asia, across Europe, and as far west as Spain. Three to four million years ago, camelids that would give rise to the current day South American species spread south across the Panamanian Land Bridge. Because of their their ability to thrive under tough conditions of extreme temperature and scarce food and water, domesticated camelids have been extremely important to the development of human cultures in the steppes of Eurasia, the deserts of Africa, and the arid Andes of South America.

All camelids are diurnal and are adapted to harsh and dry climates. They are all highly social.

Six living species of camelids are recognized by Franklin (2011), three of which are domesticated forms.

1) Bactrian Camel (Camelus bactrianus). The Bactrian Camel is associated with Central Asia. The wild form (known to science only since 1878) is critically endangered in its remote Gobi Desert homeland, but the domesticated form is found widely in Asia. The relationship between the wild and domesticated forms remains unclear. Bactrian Camels were domesticated 4,000-6,000 years ago. Some authorities recognize the wild form as a distinct species, Camelus ferus, in part based on preliminary genetic evidence that the wild and domestic "Bactrian Camel" lineages actually diverged hundereds of thousands of years ago.

2) Dromedary (Camelus dromedarius). This one-humped camel is associated with northern Africa and southwestern Asia. This camel is entirely domesticated (except for a free-ranging feral population in central Australia that was introduced in the late 1800s). The Dromedary was domesticated around 4000-5000 years ago; the wild form is believed to have gone extinct by 2000-5000 years ago. The Dromedary's hump contains a large fat reservoir that sustains it through times of scarcity. When the animal is well fed, the hump is plump and erect, but in starved animals it shrinks or flops to one side. Even when food is plentiful, Dromedaries may travel 30 km/day. A range of domesticated Dromedary varieties have been bred as pack or riding animals or for milk or meat. In the wet season, when lush, green plants are available, Dromedaries can go eight months without drinking. They can tolerate water loss greater than 30% of body weight (half this loss is fatal for most mammals).

3) Guanaco (Lama guanicoe). The heart of this species' range is Patagonia, in southern South America, but this is the most widely distributed wild artiodactyl in South America and occurs in four of the continent's 10 major habitats: desert and xeric shrublands, montane and lowland grasslands, savannas and shrublands, and wet temperate forests. Guanacos are both grazers and browsers and range from coastal forests at sea level to sparsely vegetated alpine deserts at 4500 m. In some areas, they may be found in isolated but productive meadows. Galloping Guanacos can exceed 55 km/h.

4) Llama (Lama glama). This species, domesticated largely as a pack animal and meat source (although there is a less common long-wooled form valued for its wool), is derived from the Guanaco lineage. Llamas were domesticated between 4000 and 6000 years ago. With a mass of up to 220 kg, Llamas are the largest of the four South American camelids and the tallest Neotropical mammals.

5) Viçuna (Vicugna vicugna). This species is far more specialized in its habitat needs than is the Guanaco, being restricted to the high Andean Puna at 3200-4800 m. The Viçunaand Guanaco lineages are believed to have diverged between two and three million years ago. The unique equatorial high-altitude short grassland in which the viçuna lives is found above the treeline but below the snowline. With their gazelle-like build, viçuna are the smallest camelids. The Viçuna and Alpaca are the only living ungulates with continuously growing incisors, like rodents. Viçuna and Alpacas need to drink frequently, unlike other camelids.

6) Alpaca (Vicugna pacos). This species, domesticated largely as a wool producer, is derived from the Viçuna lineage. Its long, thick wool can give an alpaca the bulky appearance of a Llama (in fact, it was at one time placed in the genus Lama, before its much closer relationship with the Viçuna was recognized). More than a million small producers in the central Andes depend upon the Alpaca and Llama as their pricipal means of subsistence. Most Alpacas are kept in herds of fewer than 50 individuals, but some commercial herds can reach 50,000 animals. Alpacas are believed to have been domesticated between 5500 and 6500 years ago.

Llamas and Alpacas have hybridized extensively.

Camels and Humans

Camelids have played critical roles in a range of human societies. For thousands of years in Central Asia and Asia Minor, domestic Bactrian Camels have served as pack animals in times of peace and war and as draft animals for ploughing and pulling carts. They connected the East and West over the Silk Road, bringing Siberian and Indian goods to the Persians. They have also provided meat, milk, and wool, without which the Gobi Desert would have been uninhabitable for humans. Because these camels are intolerant of high temperature for long periods while they are working, caravans traveling westward from China across the Gobi Desert always traveled in winter. Since at least 1000 BC, Bactrian Camels have been intentionally hybridized with Dromedaries, yielding especially strong pack animals known as Bukhts. Hybrids are also produced in an effort to combine the higher milk production of the Dromedary with the cold tolerance of the Bactrian. The world population of domestic Bactrians is estimated to be somewhere between around 750,000 and one million (according to some sources, as many as two million), with most of these animals found in Mongolia and China.

In the hot deserts of North Africa, Dromedaries have served as beasts of burden and provided meat, milk, fat, and fuel, as well as soft wool for clothing and tents. In some areas, live Dromedaries are bled for consumption of the blood (with a single individual yielding up to 35 liters per year).

Around 95% of the camelids in the Old World are Dromedaries, with nearly all of the remaining 5% being domestic Bactrian Camels (there are no more than a few thousand wild Bactrian Camels). In the New World, around 47% of camelids are Llamas, 41% Alpacas, 8% Guanacos, and 4% Viçunas.

(Franklin 2011 and references therein)

Camelids are members of the biological family Camelidae, the only currently living family in the suborder Tylopoda. The seven extant members of this group are: dromedary camels, Bactrian camels, wild Bactrian camels, llamas, alpacas, vicuñas, and guanacos. Camelids are even-toed ungulates classified in the order Cetartiodactyla, along with species including whales, pigs, deer, cattle, and antelopes.

Camelids are large, strictly herbivorous animals with slender necks and long legs. They differ from ruminants in a number of ways.[2] Their dentition show traces of vestigial central incisors in the incisive bone, and the third incisors have developed into canine-like tusks. Camelids also have true canine teeth and tusk-like premolars, which are separated from the molars by a gap. The musculature of the hind limbs differs from those of other ungulates in that the legs are attached to the body only at the top of the thigh, rather than attached by skin and muscle from the knee upwards. Because of this, camelids have to lie down by resting on their knees with their legs tucked underneath their bodies.[1] They have three-chambered stomachs, rather than four-chambered ones; their upper lips are split in two, with each part separately mobile; and, uniquely among mammals, their red blood cells are elliptical.[2] They also have a unique type of antibodies, which lack the light chain, in addition to the normal antibodies found in other mammals. These so-called heavy-chain antibodies are being used to develop single-domain antibodies with potential pharmaceutical applications.

Camelids do not have hooves; rather, they have two-toed feet with toenails and soft foot pads (Tylopoda is Greek for "padded foot"). Most of the weight of the animal rests on these tough, leathery sole pads. The South American camelids have adapted to the steep and rocky terrain by adjusting the pads on their toes to maintain grip.[3] The surface area of Camels foot pads can increase with increasing velocity in order to reduce pressure on the feet and larger members of the camelid species will usually have larger pad area to help distribute weight across the foot.[4] Many fossil camelids were unguligrade and probably hooved, in contrast to all living species.[5]

Camelids are behaviorally similar in many ways, including their walking gait, in which both legs on the same side are moved simultaneously. While running, camelids engage a unique "running pace gait" in which limbs on the same side move in the same pattern they walk, with both left legs moving and then both right, which ensures that the fore and hind limb will not collide while in fast motion. During this motion, all four limbs momentarily are off the ground at the same time.[6] Consequently, camelids large enough for human beings to ride have a typical swaying motion.

Dromedary camels, bactrian camels, llamas, and alpacas are all induced ovulators.[7]

The three Afro-Asian camel species have developed extensive adaptations to their lives in harsh, near-waterless environments. Wild populations of the Bactrian camel are even able to drink brackish water, and some herds live in nuclear test areas.[8]

Comparative table of the seven extant species in the family Camelidae:

C. kansanus

C. hesternus

C. minodokae

Camelids are unusual in that their modern distribution is almost the inverse of their area of origin. Camelids first appeared very early in the evolution of the even-toed ungulates, around 50 to 40 million years ago during the middle Eocene, in present-day North America. Among the earliest camelids was the rabbit-sized Protylopus, which still had four toes on each foot. By the late Eocene, around 35 million years ago, camelids such as Poebrotherium had lost the two lateral toes, and were about the size of a modern goat.[5][10]

The family diversified and prospered, with the two living tribes, the Camelini and Lamini, diverging in the late early Miocene around 17 million years ago, but remained confined to the North American continent until about seven million years ago, when Paracamelus crossed the Bering land bridge into Eurasia, giving rise to the modern camels, and about three million years ago, when Hemiauchenia emigrated into South America (as part of the Great American Interchange, giving rise to the modern llamas. A population of Paracamelus continued living in North America and evolved into the high arctic camel, which survived until the middle Pleistocene.

The original camelids of North America remained common until the quite recent geological past, but then disappeared, possibly as a result of hunting or habitat alterations by the earliest human settlers, and possibly as a result of changing environmental conditions after the last ice age, or a combination of these factors. Three species groups survived - the dromedary of northern Africa and southwest Asia; the Bactrian camel of central Asia; and the South American group, which has now diverged into a range of forms that are closely related, but usually classified as four species - llamas, alpacas, guanacos, and vicuñas. Camelids were domesticated by early Andean peoples,[11] and remain in use today.

Fossil camelids show a wider variety than their modern counterparts. One North American genus, Titanotylopus, stood 3.5 m at the shoulder, compared with about 2.0 m for the largest modern camelids. Other extinct camelids included small, gazelle-like animals, such as Stenomylus. Finally, a number of very tall, giraffe-like camelids were adapted to feeding on leaves from high trees, including such genera as Aepycamelus and Oxydactylus.[5]

Whether the wild Bactrian camel (Camelus ferus) is a distinct species or a subspecies (C. bactrianus ferus) is still debated.[12][13] The divergence date is 0.7 million years ago, long before the start of domestication.[13]

Family Camelidae

Camelids are members of the biological family Camelidae, the only currently living family in the suborder Tylopoda. The seven extant members of this group are: dromedary camels, Bactrian camels, wild Bactrian camels, llamas, alpacas, vicuñas, and guanacos. Camelids are even-toed ungulates classified in the order Cetartiodactyla, along with species including whales, pigs, deer, cattle, and antelopes.