en

names in breadcrumbs

Perception Channels: visual ; tactile ; acoustic ; chemical

For Greylag geese, threats from the air include golden eagles, ravens, and hawks, and on the ground, prowling dogs, foxes, and humans. (Lorenz 1991)

Known Predators:

Greylag goose plumage is grayish-brown, with pale margins on feathers in the upper part. In the lower part it has a white belly, and grayish shading on the lower breast. Similar to all of this is the neck and the head. It has an orange, large bill. The feet and legs are flesh tissue colored, and in most adults there is spotting and blotching in most adults. Young birds do not have this characteristic, and have grayish legs. On average the length of a mature bird is 80 cm (31 inches). The mass of the birds tends to be in the range of 2500 to 4100 g. The average weight of males is 36 g (1.3 oz) and for females is 32 g (1 oz). Wingspan reaches 76 to 89 cm. (Soothill & Whiteherd, 1996; Dunning, 1993)

Range mass: 2160 to 4560 g.

Range length: 76 to 89 cm.

Average length: 80 cm.

Range wingspan: 147 to 180 cm.

Average wingspan: 163 cm.

Other Physical Features: endothermic ; bilateral symmetry

Most Greylag geese live until they are twenty years old. (Lorenz, 1991)

Typical lifespan

Status: wild: 243.33 (high) months.

Average lifespan

Status: wild: 243.33 months.

Typical lifespan

Status: captivity: 20 (low) years.

Range lifespan

Status: wild: 21 (high) years.

During the breeding season Greylag geese live in lowland marshes and fens that have a lot of vegetation, as well as offshore islands. Outside of the breeding season they spend time in fresh-and salt-water marshes, estuaries, stubble fields, pasture lands, and potato fields. (Soothill & Whiteherd, 1996)

Habitat Regions: temperate ; terrestrial

Terrestrial Biomes: tundra

Wetlands: marsh ; swamp

Other Habitat Features: agricultural ; riparian ; estuarine

During the summer the Graylag Geese, Anser anser, live in Scotland, Iceland; Scandinavia and Eastward to Russia, as well as Poland and Germany. The Iceland birds migrate in autumn to the British Isles, and usually arrive in October. The Netherlands, Spain, France, eastern Mediterranean, and North Africa are places in which the rest of the European population spends winter. (Soothill & Whiteherd, 1996)

Biogeographic Regions: palearctic (Native )

Food include grasses, rhizomes of marsh plants, and roots, and some small aquatic animals. They also eat spilled grain in stubbles, and different kinds of root crops, as well as turnips, carrots, and potatoes. (Soothill & Whiteherd, 1996)

Animal Foods: amphibians; fish; insects; mollusks; aquatic crustaceans

Plant Foods: leaves; roots and tubers; seeds, grains, and nuts; fruit; algae

Primary Diet: herbivore (Granivore )

Thousands of years ago Greylag geese were domesticated and used for many purposes. One of the purposes of raising geese is because of the meat, which is very rich in flavor . The down (soft feathers) of the birds has also been very useful for many commodities such as stuffing in pillows, as a lightweight, mattresses, outdoor clothing sleeping bags, and insulating material. (Austic, 2001)

Positive Impacts: food

Farming has been affected due to overpopulation. Greylag geese flocks have been known to harm potato and carrot fields in different parts of Europe. (Schneck, 1999)

Negative Impacts: crop pest

Greylag Geese once were very common in Western Europe, but due to the draining of marshes there has been a severe drop in numbers. Currently, this species has increased in numbers up to a point of reaching flocks of tens of thousands. (Schneck 1999)

US Migratory Bird Act: no special status

US Federal List: no special status

CITES: no special status

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: least concern

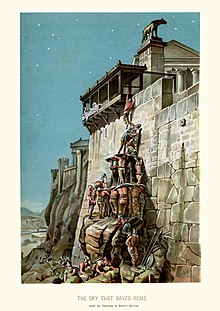

An interesting fact about Greylag geese is that they were once considered sacred by the Romans after reportedly saving the city of Rome in 390 BC. When the Gauls tried to climb in, the geese warned the Romans with their loud calls about the attempted invasion. After this, Caesar believed that the geese were sacred and it was ordered that the geese were to not be eaten in Pre-Roman Britain. (Schneck 1999)

Mating System: monogamous

In Iceland, the breeding season starts in early May, and in Scotland it begins in late April. In middle Europe the breeding season starts a bit earlier. The nests are built among reeds and bushes. They are also build in high and elevated places, as well as marshy regions, and small isles to keep eggs and goslings safe from predators.

The number of eggs varies from three to twelve, but is usually only four to six. The eggs are creamy white, and about 85 x 58mm (3.3 to 2.3 inches) in size. The eggs are incubated only by the female, and take 27 to 28 days to hatch. After hatching, the goslings usually wait until drying out to leave the nest. With the supervision of their parents the young birds feed themselves, and in about eight weeks they are fully independent.

Geese take from 2 to 3 years to reach sexual maturity but usually mature at 3 years. (Soothill & Whiteherd, 1996; del Hoyo et al., 1992)

Breeding season: Spring

Range eggs per season: 3 to 12.

Average eggs per season: 6.

Range time to hatching: 27 to 28 days.

Range fledging age: 50 to 60 days.

Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female): 2 to 3 years.

Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male): 2 to 3 years.

Key Reproductive Features: iteroparous ; seasonal breeding ; gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); sexual ; oviparous

Parental Investment: precocial ; male parental care ; female parental care

Accidental visitor.

The greylag goose or graylag goose (Anser anser) is a species of large goose in the waterfowl family Anatidae and the type species of the genus Anser. It has mottled and barred grey and white plumage and an orange beak and pink legs. A large bird, it measures between 74 and 91 centimetres (29 and 36 in) in length, with an average weight of 3.3 kilograms (7 lb 4 oz). Its distribution is widespread, with birds from the north of its range in Europe and Asia migrating southwards to spend the winter in warmer places. It is the ancestor of most breeds of domestic goose, having been domesticated at least as early as 1360 BC. The genus name is from anser, the Latin for "goose".[2]

Greylag geese travel to their northerly breeding grounds in spring, nesting on moorlands, in marshes, around lakes and on coastal islands. They normally mate for life and nest on the ground among vegetation. A clutch of three to five eggs is laid; the female incubates the eggs and both parents defend and rear the young. The birds stay together as a family group, migrating southwards in autumn as part of a flock, and separating the following year. During the winter they occupy semi-aquatic habitats, estuaries, marshes and flooded fields, feeding on grass and often consuming agricultural crops. Some populations, such as those in southern England and in urban areas across the species' range, are primarily resident and occupy the same area year-round.

Anser anser, the greylag goose, is a member of the waterfowl family Anatidae. It was first described by the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus in 1758 as Anas anser, but was transferred two years later to the new genus Anser, erected by the French zoologist Mathurin Jacques Brisson, where it is the type species. Two subspecies are recognised; A. a. anser, the western greylag goose, which breeds in Iceland and northern and central Europe; A. a. rubrirostris, the eastern greylag goose, which breeds in Romania, Turkey, and Russia eastwards to northeastern China. The two subspecies intergrade where their ranges meet. The greylag goose sometimes hybridises with other species of goose, including the barnacle goose (Branta leucopsis) and the Canada goose (Branta canadensis), and occasionally with the mute swan (Cygnus olor).[3] The greylag goose was one of the first animals to be domesticated; this happened at least 3,000 years ago in Ancient Egypt, the domestic subspecies being known as A. a. domesticus.[4] As the domestic goose is a subspecies of the greylag goose they are able to interbreed, with the offspring sharing characteristics of both wild and domestic birds.[5]

The greylag is the largest and bulkiest of the grey geese of the genus Anser, but is more lightly built and agile than its domestic relative. It has a rotund, bulky body, a thick and long neck, and a large head and bill. It has pink legs and feet, and an orange or pink bill with a white or brown nail (hard horny material at tip of upper mandible).[6] It is 74 to 91 centimetres (29 to 36 in) long with a wing length of 41.2 to 48 centimetres (16+1⁄4 to 19 in). It has a tail 6.2 to 6.9 centimetres (2+7⁄16 to 2+11⁄16 in), a bill of 6.4 to 6.9 centimetres (2+1⁄2 to 2+11⁄16 in) long, and a tarsus of 7.1 to 9.3 centimetres (2+13⁄16 to 3+11⁄16 in). It weighs 2.16 to 4.56 kilograms (4 lb 12 oz to 10 lb 1 oz), with a mean weight of around 3.3 kilograms (7 lb 4 oz). The wingspan is 147 to 180 centimetres (58 to 71 in).[7][8][9] Males are generally larger than females, with the sexual dimorphism more pronounced in the eastern subspecies rubirostris, which is larger than the nominate subspecies on average.[6]

The plumage of the greylag goose is greyish brown, with a darker head and paler breast and belly with a variable amount of black spotting. It has a pale grey forewing and rump which are noticeable when the bird is in flight or stretches its wings on the ground. It has a white line bordering its upper flanks, and its wing coverts are light coloured, contrasting with its darker flight feathers. Its plumage is patterned by the pale fringes of the feathers. Juveniles differ mostly in their lack of black speckling on the breast and belly and by their greyish legs.[6][10] Adults have a distinctive 'concertina' pattern of folds in the feathers on their necks.

The greylag goose has a loud cackling call similar to that of the domestic goose, "aahng-ung-ung", uttered on the ground or in flight. There are various subtle variations used under different circumstances, and individual geese seem to be able to identify other known geese by their voices. The sound made by a flock of geese resembles the baying of hounds.[11] Goslings chirp or whistle lightly, and adults hiss if threatened or angered.[6]

This species has a Palearctic distribution. The nominate subspecies breeds in Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Finland, the Baltic States, northern Russia, Poland, eastern Hungary and Romania. It also breeds locally in the United Kingdom, Denmark, Germany, Austria, the Czech Republic, Slovakia and North Macedonia. The eastern race extends eastwards across a broad swathe of Asia to China.[11] European birds migrate southwards to the Mediterranean region and North Africa. Asian birds migrate to Azerbaijan, Iran, Pakistan, northern India, Bangladesh and eastward to China.[11] In North America, there are both feral domestic geese, which are similar to greylags, and occasional vagrant greylags.[10] Greylag geese seen in the wild in New Zealand probably originated from the escape of farmyard geese,[12] and a similar situation has occurred in Australia, where feral birds are now established in the east and southeast of the country.[13]

In their breeding quarters, they are found on moors with scattered lochs, in marshes, fens and peat-bogs, besides lakes and on little islands some way out to sea. They like dense ground cover of reeds, rushes, heather, bushes and willow thickets. In their winter quarters, they frequent salt marshes, estuaries, freshwater marshes, steppes, flooded fields, bogs and pasture near lakes, rivers and streams. They also visit agricultural land where they feed on winter cereals, rice, beans or other crops, moving at night to shoals and sand-banks on the coast, mud-banks in estuaries or secluded lakes.[11] Large numbers of immature birds congregate each year to moult on the Rone Islands near Gotland in the Baltic Sea.[14]

Since the 1950s, increases in winter temperatures have resulted in greylag geese breeding in central Europe, reducing their winter migration distances. Wintering grounds closer to home can therefore be exploited, meaning that the geese can return to set up breeding territories earlier the following spring.[15]

In Great Britain, their numbers had declined as a breeding bird, retreating north to breed wild only in the Outer Hebrides and the northern mainland of Scotland. However, during the 20th century, feral populations have been established elsewhere, and they have now re-colonised much of England. These populations are increasingly coming into contact and merging.[16]

The greylag goose has become a pest species in several areas where its population has increased sharply. In Norway, the number of greylag geese is estimated to have increased three- to fivefold between 1995 and 2015. As a consequence, farmers' problems caused by goose grazing on farmland have increased considerably. This problem is also evident for the pink-footed goose. In the Orkney islands the population has increased dramatically: there were 300 breeding pairs, increasing to 10,000 in 2009, and 64,000 in 2019. Due to extensive damage caused to crops, the hunting season for the greylag goose in the Orkney islands is now most of the year.[17]

Greylag geese are largely herbivorous and feed chiefly on grasses. Short, actively growing grass is more nutritious and greylag geese are often found grazing in pastures with sheep or cows.[18] Because of its low nutrient status, they need to feed for much of their time; the herbage passes rapidly through the gut and is voided frequently.[19] The tubers of sea clubrush (Bolboschoenus maritimus) are also taken as well as berries and water plants such as duckweed (Lemna) and floating sweetgrass (Glyceria fluitans). In wintertime they eat grass and leaves but also glean grain on cereal stubbles and sometimes feed on growing crops, especially during the night. They have been known to feed on oats, wheat, barley, buckwheat, lentils, peas and root crops. Acorns are sometimes consumed, and on the coast, seagrass (Zostera sp.) may be eaten.[11] In the 1920s in Britain, the pink-footed goose "discovered" that potatoes were edible and started feeding on waste potatoes. The greylag followed suit in the 1940s and now regularly searches for tubers on ploughed fields.[14] They also consume small fish, amphibians, crustaceans, molluscs and insects.[20]

Greylag geese tend to pair bond in long-term monogamous relationships.[21] Most such pairs are probably life-long partnerships, though 5 to 8% of the pairs separate and re-mate with other geese.[21] Birds in heterosexual pairs may engage in promiscuous behavior, despite the opposition of their mates.[21]

Homosexual pairs are common (14 to 20% of the pairs may be ganders, depending on flock), and share the characteristics of heterosexual pairs with the exceptions that the bonds appear to be closer, based on the intensity of their displays.[21] Same-sex pairs also engage in courtship and sexual relations, and often assume high-ranking positions in the flock as a result of their superior strength and courage, leading some to speculate that they may serve as guardians of the flock.[21] The sexual preference of the birds is generally flexible, as more than half of widowers re-pair with a bird of the opposite sex.[21]

The nest is on the ground among heather, rushes, dwarf shrubs or reeds, or on a raft of floating vegetation. It is built from pieces of reed, sprigs of heather, grasses and moss, mixed with small feathers and down. A typical clutch is four to six eggs, but fewer eggs or larger numbers are not unusual. The eggs are creamy-white at first but soon become stained, and average 85 by 58 millimetres (3+3⁄8 by 2+5⁄16 in). They are mostly laid on successive days and incubation starts after the last one is laid. The female does the incubation, which lasts about twenty-eight days, while the male remains on guard somewhere near. The chicks are precocial and able to leave the nest soon after hatching. Both parents are involved in their care and they soon learn to peck at food and become fully-fledged at eight or nine weeks,[11] about the same time as their parents regain their ability to fly after moulting their main wing and tail feathers a month earlier. Immature birds undergo a similar moult, and move to traditional, safe locations before doing so because of their vulnerability while flightless.[18]

Greylag geese are gregarious birds and form flocks. This has the advantage for the birds that the vigilance of some individuals in the group allows the rest to feed without having to constantly be alert to the approach of predators. After the eggs hatch, some grouping of families occur, enabling the geese to defend their young by their joint actions, such as mobbing or attacking predators.[18] After driving off a predator, a gander will return to its mate and give a "triumph call", a resonant honk followed by a low-pitched cackle, uttered with neck extended forward parallel with the ground. The mate and even unfledged young reciprocate in kind.[11]

Young greylags stay with their parents as a family group, migrating with them in a larger flock, and only dispersing when the adults drive them away from their newly established breeding territory the following year.[19] At least in Europe, patterns of migration are well understood and follow traditional routes with known staging sites and wintering sites. The young learn these locations from their parents which normally stay together for life.[14] Greylags leave their northern breeding areas relatively late in the autumn, for example completing their departure from Iceland by November, and start their return migration as early as January. Birds that breed in Iceland overwinter in the British Isles; those from Central Europe overwinter as far south as Spain and North Africa; others migrate down to the Balkans, Turkey and Iraq for the winter.[22]

The greylag was once revered across Eurasia. It was linked with the goddess of healing, Gula, a forerunner of the Sumerian fertility goddess Ishtar, in the cities of the Tigris-Euphrates delta over 5,000 years ago.[23] In Ancient Egypt, geese symbolised the sun god Ra. In Ancient Greece and Rome, they were associated with the goddess of love, Aphrodite, and goose fat was used as an aphrodisiac. Since they were sacred birds, they were kept on Rome's Capitoline Hill, from where they raised the alarm when the Gauls attacked in 390 BC.[23]

The goose's role in fertility survives in modern British tradition in the nursery rhyme Goosey Goosey Gander, which preserves its sexual overtones ("And in my lady's chamber"), while "to goose" still has a sexual meaning.[23] The tradition of pulling a wishbone derives from the tradition of eating a roast goose at Michaelmas, where the goose bone was once believed to have the powers of an oracle. For that festival, in Thomas Bewick's time, geese were driven in thousand-strong flocks on foot from farms all over the East of England to London's Cheapside market, covering some 13 or 14 kilometres (8 or 9 mi) per day. Some farmers painted the geese's feet with tar and sand to protect them from road wear as they walked.[23] Greylag geese were domesticated by at least 1360 BC, when images of domesticated birds resembling the eastern race, Anser anser rubirostris (which like modern farmyard geese, but unlike western greylags, have a pink beak) were painted in Ancient Egypt. Goose feathers were used as quill pens, the best being the primary feathers of the left-wing, whose "curvature bent away from the eyes of right-handed writers".[24] The feathers also served to fletch arrows.[23] In ethology, the greylag goose was the subject of Konrad Lorenz's pioneering studies of imprinting behaviour.[25]

Egg, Collection Museum Wiesbaden

On Texel, Netherlands

In Ystad

The greylag goose or graylag goose (Anser anser) is a species of large goose in the waterfowl family Anatidae and the type species of the genus Anser. It has mottled and barred grey and white plumage and an orange beak and pink legs. A large bird, it measures between 74 and 91 centimetres (29 and 36 in) in length, with an average weight of 3.3 kilograms (7 lb 4 oz). Its distribution is widespread, with birds from the north of its range in Europe and Asia migrating southwards to spend the winter in warmer places. It is the ancestor of most breeds of domestic goose, having been domesticated at least as early as 1360 BC. The genus name is from anser, the Latin for "goose".

Greylag geese travel to their northerly breeding grounds in spring, nesting on moorlands, in marshes, around lakes and on coastal islands. They normally mate for life and nest on the ground among vegetation. A clutch of three to five eggs is laid; the female incubates the eggs and both parents defend and rear the young. The birds stay together as a family group, migrating southwards in autumn as part of a flock, and separating the following year. During the winter they occupy semi-aquatic habitats, estuaries, marshes and flooded fields, feeding on grass and often consuming agricultural crops. Some populations, such as those in southern England and in urban areas across the species' range, are primarily resident and occupy the same area year-round.