en

names in breadcrumbs

Little is known of communication and perception in Tarsipes rostratus. In other possum species, it has been suggested that secretions from the holocrine gland are used to mark habitats and signal alarm. There is no evidence indicating that possums use scent marking to attract potential mates.

Communication Channels: chemical

Other Communication Modes: scent marks

Perception Channels: visual ; tactile ; acoustic ; chemical

According to the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, honey possums are a species of “least concern”. Due to their relative abundance and broad distribution, there are no major threats to their existence. However, bushfires can result in significant habitat loss. In addition, water mold (Phytophthora cinnamomi), which is prevalent in many high humidity environments, can cause plant pathogens that could decrease resource abundance for honey possums. Finally, feral cats may have a negative effect on honey possum abundance.

US Federal List: no special status

CITES: no special status

State of Michigan List: no special status

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: least concern

There are no known adverse effects of Tarsipes rostratus on humans.

There are no known positive effects of Tarsipes rostratus on humans.

Honey possums are important pollinators for a number of different plants and are the principle pollinators of nodding banksia (Banksia nutans), which is common on the southern coast of Western Australia.

Ecosystem Impact: pollinates

Tarsipes rostratus consumes pollen and nectar from a variety of flowering plants. It is the only flightless animal that feeds exclusively on pollen and nectar. Large amounts of pollen and nectar are consumed from plants belonging to the families Proteaceae, Epacridaceae, and Myrtacae. Tarsipes rostratus prefers to forage on Banksia spp., which are large plants with widely separated and exposed inflorescences from the family Proteaceae. The Mediterranean climate of south-west Western Australia is prone to recurrent fires, which has a significant effect on the population density of T. rostratus. Areas that remain unburnt for longer periods of time have larger plants, which bear more inflorescences. Plants with more inflorescences are correlated with increased abundance of T. rostratus. Its feet and prehensile tail are used for climbing, while their forepaws with elongated digits are used to manipulate flowers during feeding. In order to acquire the necessary nutrients from nectar, a substantial quantity of fluid must be consumed. As a result of the high water content in their diet in conjunction with their inability to concentrate urine, T. rostratus frequently excretes high volumes of dilute urine.

Plant Foods: nectar; pollen

Primary Diet: herbivore (Nectarivore )

Tarsipes rostratus is native to the south western tip of Western Australia, throughout the coastal-sand plain heathlands, which contains a diverse array plant communities.

Biogeographic Regions: australian (Native )

Preferred habitat of Tarsipes rostratus is banksia woodlands, which are rich in floral diversity. The overstory of banksia woodland habitat along the south western coast of Western Australia is dominated by Banksia attenuata (slender Banksia) and B. menziesii (firewood Banksia). Eucalyptus todtiana (coastal blackbutt), E. gomphocephala (Tuart), E. marginata (Jarrah), Allocasuarina fraseriana (Fraser’s sheoak), Nuytsia floribunda (christmas tree) and other Banksia species also occur, but far less frequently. Interspersed throughout the understory are various species in the families Proteaceae, Myrtaceae, Papilionaceae, and Epacridaceae (Maher et al., 2008).

Habitat Regions: temperate ; terrestrial

Terrestrial Biomes: forest ; scrub forest

Honey possums are relatively short lived, with a lifespan of 1 to 2 years. Lifespan of captive individuals has not been documented.

Range lifespan

Status: wild: 1 to 2 years.

Average lifespan

Status: wild: 2.0 years.

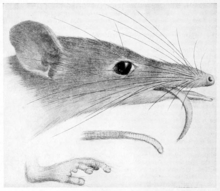

Tarsipes rostratus has grey fur that is brown on the dorsal side with a dark stripe starting from the nape of the neck extending down towards the base of the tail. It has white and yellow ventral pelage on its underbelly that becomes orange on its sides. The head is dorsoventrally flattened with an elongated snout that is approximately two and a half times longer than its maximum width. Tarsipes rostratus has a brush-tipped protrusible tongue that is equal in length to the head. With the exception of the incisors, which are enlarged, the dentition of T. rostratus is greatly reduced. Its hands and feet have rough pads, opposable and elongated digits, with nails that do not project beyond the toe-pads. It has a prehensile tail that is hairless on the ventral surface near the tip. Tarsipes rostratus is sexually dimorphic, with females being approximately a third heavier than males. Females range in mass from 10 to 18 g, have a body length ranging from 70 to 90 mm, and a tail that measures from 75 to 105 mm in length. Males range in mass from 6 to 12 g, have a body length ranging from 65 to 85 mm, and a tail that measures from 70 to 100 mm in length. Despite females being slightly larger, there is no difference in head length between the sexes.

Tarsipes rostratus has a higher basal metabolic rate (BMR) and field metabolic rate (FMR) than most other marsupials. It has an average body temperature of 36.6 C, which is much higher than the typical marsupial, and a BMR of 2.9 cm^3 oxygen/hour. When in torpor, if its body temperature falls below 5 degrees C it is incapable of exiting torpor. Daily energy expenditures range from 25 to 30 kJ/day, which classifies them as hypermetabolic. In order to meet their high energy demands, its diet consists primarily of pollen and nectar.

Range mass: 6 to 18 g.

Range length: 65 to 90 mm.

Average basal metabolic rate: 2.9 cm3.O2/g/hr.

Other Physical Features: endothermic ; homoiothermic; bilateral symmetry

Sexual Dimorphism: female larger

Average basal metabolic rate: 0.162 W.

Aerial predators of honey possums, include barn owls (Tyto alba) and black-shouldered kites (Elanus caesuleus), and common terrestrial predators include red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) and feral cats (Felis domesticus). In certain parts of their range, Fitzgerald River National Park, other potential predators include tiger snakes (Notechis scutatus), southern monitors (Varanus rosenbergi), square-tailed kites (Lophoictinia isura), Australian kestrels (Falco cenchroides), brown falcons (Falco berigora), and boobook owls (Ninox novaeseelandiae). Honey possums are arboreal and are most commonly found in the lower canopy. As a result, the upper canopy likely provides shelter from aerial predators and being elevated off the forest floor likely decreases predation pressure from terrestrial predators.

Known Predators:

Tarsipes rostratus mates several times a year in a non-seasonal pattern. Females are polyandrous and have small litters, usually between 2 and 3 offspring but potentially up to 4, with multiple paternities. Female polyandry results in sperm competition between males. The testes of male T. rostratus are very large relative to their body size, weighing more than 4% of their total body mass. Their testes contain sperm that is larger than any other mammal. Males compete for estrous females and courtship is limited with no ongoing association after copulation.

Mating System: polyandrous

There is a strong association between reproductive success and diet in Tarsipes rostratus. Reproduction occurs during peak flowering periods when resources are abundant. In addition, breeding periods are affected by photoperiod and evidence suggests that the southern summer solstice triggers the first reproduction of the year. In general, breeding occurs from May to June, when day length begins to decrease and from September to October, when day length begins to increase.

Breeding interval: Honey possums breed whenever conditions are favourable.

Breeding season: Honey possums breed year round.

Range number of offspring: 2 to 4.

Range weaning age: 60 (high) days.

Range time to independence: 60 (high) days.

Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female): 90 (high) days.

Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male): 90 (high) days.

Key Reproductive Features: iteroparous ; year-round breeding ; gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); sexual ; viviparous ; embryonic diapause

Average birth mass: 0.004 g.

Average gestation period: 24 days.

Average number of offspring: 3.

Tarsipes rostratus has the smallest young of any mammal, which are reared in the pouch for about 60 days. By 60 days old young are highly mobile, fully-furred, and have eyes that are completely open. Young become sexually mature around 90 days and females often breed before their young disperse. Due to a period of embryonic diapause, gestation in T. rostratus lasts from 60 to 80 days longer than in other marsupials. Unlike other mammals, embyonic diapause in T. rostratus is not controlled by lactation.

Parental Investment: female parental care ; pre-weaning/fledging (Provisioning: Female, Protecting: Female); pre-independence (Provisioning: Female, Protecting: Female)

The honey possum or noolbenger (Tarsipes rostratus), is a tiny species of marsupial that feeds on the nectar and pollen of a diverse range of flowering plants. Found in southwest Australia, it is an important pollinator for such plants as Banksia attenuata, Banksia coccinea and Adenanthos cuneatus.[3]

The first description of the diprotodont species was published by Paul Gervais and Jules Verreaux on 3 March 1842, referring to a specimen collected by Verreaux. The lectotype nominated for this species, held in the collection at National Museum of Natural History, France, was collected the Swan River Colony.[1][4] A description of a second species Tarsipes spenserae,[5] published five days later by John Edward Gray and current until the 1970s, was thought to have been published earlier by T. S. Palmer in 1904[6] and displaced the usage of T. rostratus. A review by Mahoney in 1984 again reduced T. spenserae to a synonym for the species, as was the emendation to its spelling as spencerae cited by William Ride (1970) and others.[7][8][9] Gray's specimen was provided by George Grey to the British Museum of Natural History, the skin of a male also collected at King George Sound.[4] The author was aware of the description prepared by Gervais, who after examining his specimen suggested it represented a second species.

The population is the only known species in the genus Tarsipes, and assigned to a monotypic diprotodont family Tarsipedidae.[10] The name of the genus means "tarsier-foot", given for a resemblance to tarsier's simian-like feet and toes noted by the earliest descriptions.[11]

The poorly resolved phylogeny of ancestral marsupial relationships has presented this taxon, unique in many characteristics, in an arrangement of other higher classifications, including the separation as a superfamily Tarsipedoidea, later abandoned in favour grouping of South American and Australian marsupials as a monophyletic clade that ignores the modern geographic remoteness of these continent's fauna.[12]

The relationships of the monotypic family within the Diprotodontia order as a petauroid alliance may be summarised as,

The closest relationship to other taxa was theorised to be Dromiciops gliroides, another smaller marsupial that occurs in South America and is known as the extant member of a genus that is represented in the Gondwanan fossil record. This was supported by phylogenetic analysis,[9] but this is no longer believed to be true.[13]

At Grey's suggestion, the maiden name of his wife Eliza Lucy Spencer was assigned to the epithet. Eliza or Elizabeth was the daughter of the government resident at King George Sound, Richard Spencer, prompting the unacceptable correction by Ride in 1970.

The common names include those cited or coined by Gilbert, Gould and Ellis Troughton, honey and long-snouted phalanger, tait and noolbenger in the local languages, or the descriptive brown barred mouse. An ethnographic survey of Noongar words recorded for the species found three names were in use, and proposed that these be regularised for spelling and pronunciation as ngoolboongoor (ngool'bong'oor), djebin (dje'bin) and dat.[14] The term honey mouse was recorded by Troughton in 1922 as commonly used in the districts around King George Sound.[8]

A tiny marsupial that climbs woody plants to feed on the pollen and nectar, the honey, of banksia and eucalypts. They resemble a small mouse or the arboreal possums of Australia, and are readily distinguished by the exceptionally long muzzle and three brown stripes from the head to the rump. The pelage is a cream colour below that merges to rufous at the flanks, the overall coloration of the upperparts is a mix of brown and grey hairs. A dark brown central stripe extends from the rump to a mid-point between the ears, this is a more distinct stripe than the two paler adjacent stripes. The length of the tail is from 70 to 100 millimetres, exceeding the combined body and head length of 65 to 85 mm, and has a prehensile ability that assists in climbing. The recorded weight range for the species is 5 to 10 grams.[15] The number of teeth are fewer and most much smaller than is typical for marsupials, with the molars reduced to tiny cones. The dental formula of I2/1 C1/0 P1/0 M3/3 totals no more than 22 teeth.[11] The morphology of the elongated snout's jaws and dentition presents a number of unique characteristics suited to the specialisation as a palynivore and nectivore. Tarsipes tongue is extensible and the end covered in brush-like papillae, with the redundant action of the modified or reduced teeth being replaced by the interaction of the tongue, keel-like lower incisors and a fine combing surface at the palate.[16][11]

The testes are very large in size, noted as proportionally the greatest for a mammal at 4.6 percent of the body weight. The sperm also has an exceptional length; its tail (flagellum) measurement of 360 micrometres also cited as the longest known. Specialised characters of T. rostratus include visual acuity for detecting the bright yellow inflorescence of Banksia attenuata.[17]

They have a typical lifespan between one and two years.[18]

They have trichromat vision, similar to some other marsupials as well as primates but unlike most mammals which have dichromat vision.[19]

The honey possum is mainly nocturnal, but will come out to feed during daylight in cooler weather. Generally, though, it spends the days asleep in a shelter of convenience: a rock cranny, a tree cavity, the hollow inside of a grass tree, or an abandoned bird nest. When food is scarce, or in cold weather, it becomes torpid to conserve energy. In comparison to other marsupials of a similar size, T. rostratus has a high body temperature and metabolic rate that is termed euthermic. Lacking fat reserves, but able to reduce their body temperature, exposure to cooler temperatures or lack of food induces one of two states of torpor. One response is a shallow and brief period, similar to torpid dasyurids, where the body temperature is above 10–15 degrees Celsius, and another deeper state like the burramyids that lasts for multiple days and reduces their temperature to less than 10 °C.[20]

The species is able to climb with the assistance of the prehensile tail and an opposable first toe at the long hindfoot that is able to grip like a monkey's paw. The bristle-like papillae at the upper surface of the tongue increase in length toward the tip, and this is used to gather the pollen and nectar by rapidly wiping it into the inflorescence.[3] Both its front and back feet are adept at grasping, enabling it to climb trees with ease, as well as traverse the undergrowth at speed. The honey possum can also use its prehensile tail (which is longer than its head and body combined) to grip, much like another arm.[18]

Radio-tracking has shown that males particularly are quite mobile, moving distances of up to 0.5 km in a night and use areas averaging 0.8 hectares.[21] Males seem to venture out in a larger range, and some evidence indicates greater distances covered; evidence of pollen found on an individual in a study area was from a banksia not found within three kilometres of the collection site.[9]

The plant species that provide nectar and pollen to T. rostratus are primarily genera of Proteaceae, Banksia and Adenanthos, and Myrtaceae, eucalypts and Agonis, and those of Epacridaceae, shrubby heath plants, although it is also known to visit the inflorescence of Anigozanthos, the kangaroo paws, and the tall spikes of Xanthorrhoea, the grass-trees.[9] Study of the amount of nectar and pollen has concluded that a nine gram individual requires around seven millilitres of nectar and one gram of pollen each day to maintain an energetic balance. This amount of pollen provides sufficient nitrogen for the species high activity metabolism, and the additional nitrogen requirements of females during lactation is available in the pollen of Banksia species. The ingestion of excess water when feeding at wet flowers, a frequent circumstance in the high rainfall regions of its range, is able to be eliminated by kidneys that can process up to two times the animals body weight in water.[22] Pollen grains are digested over the course of six hours, extracting almost all the nutrients they contain.[9]

Breeding depends on the availability of nectar and can occur at any time of the year. Females are promiscuous, mating with a large number of males and may simultaneously carry embryos from different progenitors. Competition has led to the males having very large testicles relative to their body weight, at a relative mass of 4.2% it is amongst the largest known for a mammal. Their sperm is the largest in the mammal world, measuring 365 micrometres.[23]

The development of blastocysts corresponds to day length, induced by a shorter photoperiod, but other reproductive processes are prompted by other factor, probably food availability.[24] Gestation lasts for 28 days, with two to four young being produced. At birth, they are the smallest of any mammal, weighing 0.005 g. Nurturing and development within the pouch lasts for about 60 days, after which they emerge covered in fur and with open eyes, weighing some 2.5 g. As soon as they emerge, they are often left in a sheltered area (such as a hollow in a tree) while the mother searches for food for herself, but within days, they learn to grab hold of the mother's back and travel with her. However, their weight soon becomes too much, and they stop nursing at around 11 weeks, and start to make their own homes shortly thereafter.[18] As is common in marsupials, a second litter is often born when the pouch is vacated by the first, fertilised embryos being stopped from developing.[25]

Most of the time, honey possums stick to separate territories of about one hectare (2.5 acres),[26] outside of the breeding season. They live in small groups of no more than 10, which results in them engaging in combat with one another only rarely. During the breeding season, females move into smaller areas with their young, which they will defend fiercely, especially from any males.[18]

Although restricted to a fairly small range in the southwest of Western Australia, it is locally common and does not seem to be threatened with extinction so long as its habitat of heath, shrubland, and woodland[18] remains intact and diverse. Records of locations held at the Western Australian Museum indicate they are more common in regions of high Proteaceae diversity, areas such as banksia woodlands where species can be found flowering at all times of the year.

Tarsipe rostratus is a keystone species in the ecology of the coastal sands of Southwest Australia, complex assemblages of plants known as kwongan, and are likely to be the primary pollinator of woody shrubs such as banksia and Adenanthos. Their feeding activity involves visits to many individual plants and the head carries a small pollen load that can convey more effectively than the birds that visit the same flowers. The favoured species Banksia attenuata appears to be obliged to this animal as a pollination vector, and both species have evolved to suit their mutualistic interactions.[27]

The effect of fire frequency on the population was evaluated in a study over a twenty three-year period, giving indications of resilience of the species to the first fire in the area and a subsequent burn six years later. The effect of increased frequency and intensity of fire, due to global warming and prescribed burns can adversely affect the suitability of the local habitat.[28] The species is susceptible to the impact of Phytophthora cinnamomi, a soil borne fungal-like species that is associated with forest dieback in the eucalypt forests and banksia woodlands of the region. The flowers of the nine plant species most favoured by T. rostratus provide food throughout the year, and five of these are vulnerable to the withering condition caused by P. cinnamomi pathogen.[17]

It is the only entirely nectarivorous mammal which is not a bat;[29] it has a long, pointed snout and a long, protrusile tongue with a brush tip that gathers pollen and nectar, like a honeyeater or a hummingbird. Floral diversity is particularly important for the honey possum, as it cannot survive without a year-round supply of nectar and, unlike nectarivorous birds, it cannot easily travel long distances in search of fresh supplies.

An animal well known to the Noongar people of southwest, and incorporated into their culture, the name ngoolboongoor from the indigenous language has been proposed for modern usage as a common name, written as noolbenger.[9][14] Honey possums continue to be an iconic animal to the people of the region, and was selected by Amok Island to feature in a large public art project on silos in the wheatbelt.[30] The first report of the species was compiled by John Gilbert, the careful and thorough field collector commissioned by Gould to travel to the new colony at the Swan River on the west coast of Australia. Gilbert obtained access to Noongar informants that provided him with the names and details of the animals habits and, with some difficulty, four specimens for scientific examination. Both he and Gould recognised the unique characters of the unknown species.[9]

The next major field study was undertaken by the mammalogist Ellis Troughton at the suggestion of H. L. White, who provided an introduction to the professional collector F. Lawson Whitlock. Troughton's visit to King George Sound was guided by Whitlock to the source of a specimen he had sent to White, a man in the same region named David Morgan who accommodated the biologist while he searched extensively and unsuccessfully for further specimens. Troughton was eventually provided with a series of a dozen specimens when he was preparing to leave Albany port, a collection assembled over many years by the cats of Hugh Leishman at Nannarup. The collection of the Australian Museum was increased when Morgan continued to forward specimens to Troughton, firstly with two pregnant females that were also killed by a cat, and then with a report of living animals he was able to maintain in captivity for five to six weeks. Morgan reported that his cat would bring a mangled specimen on a daily basis for a period of time, and observed it seeking them in a flowering shrub at dusk, but thought their local appearance was seasonally related and became absent outside the breeding season.[8]

Closer study of the reproductive processes was allowed by the capture, extended observation and dissection of the species in University programs, the first success in captivity beginning in 1974. Examination of the reproductive strategies has allowed comparison to the other modern marsupial families, in particular the evolution of embryonic diapause.[31] The population structure and feeding habits of T. rostratrus was poorly understood until a biological study at the Fitzgerald River National Park was completed in 1984.[9]

A diet consisting entirely of nectar is unusual for a terrestrial vertebrate species, usually birds and flying mammals, and specialisation to the niche provided by the success of plant families Proteaceae and Myrtaceae began around forty million years ago.[9]

The honey possum or noolbenger (Tarsipes rostratus), is a tiny species of marsupial that feeds on the nectar and pollen of a diverse range of flowering plants. Found in southwest Australia, it is an important pollinator for such plants as Banksia attenuata, Banksia coccinea and Adenanthos cuneatus.