en

names in breadcrumbs

Aquatic adult tiger salamanders live up to 25 years in captivity. Normal adults have reached ages of 16 years.

Range lifespan

Status: captivity: 25 (high) years.

Average lifespan

Status: captivity: 25.0 years.

Average lifespan

Status: captivity: 10.3 years.

Tiger salamanders are eaten by badgers, snakes, bobcats, and owls. Larvae are eaten by aquatic insects, the larvae of other salamanders, and snakes.

Adult Length 17-33 cm.

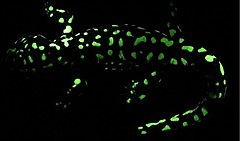

The adult tiger salamander is a thick-bodied creature generally with yellow blotches or spots against a black background. Once in a while there will be one with blotches that are tan or olive green in color. The spots or blotches are never in any set shape, size or position. Actually you may even be able to tell its origin by the color and pattern of the background and/or spots (Indiviglio 1997). A. tigrinum has a rather large head and a broad rounded snout. Their eyes are round. The belly is usually yellowish or olive with invading dark pigment. It has about 12-13 coastal grooves (Harding 1997). Males tend to be proportionally longer, with a more compressed tail and longer stalkier hind legs than the females. During the breeding season the males have a swollen vent area. The larvae have a yellowish green or olive body with the dark blotches and a stripe along each side. They also have a whitish belly. As they grow, specimens tend to be grayish or greenish in color, and within a few weeks they start to show yellow or tan spots and gradually merge into the patterns of the adult bodies (Harding 1997).

Other Physical Features: ectothermic ; heterothermic ; bilateral symmetry

Average mass: 9.402 g.

Average basal metabolic rate: 0.00196 W.

Fully metamorphosed adults lead a terrestrial existance and, depending upon where in the country they are found, some may inhabit forests, grasslands, or marshy areas (Petranka 1998). Tiger salamanders are less dependent on the forest than most other Ambystomids. One general requirement seems to be soil in which they are able to burrow or in which the burrow of other species of other animals might be utilized (Petranka1998). While they are well suited for terrestrial existence in terms of their skin consistency and thickness, they do need to be able to burrow underground in order to seek the proper humidity levels. Another requirement is that they live close enough for permanent access to ponds and othe small waters for their breeding. During dry periods, large numbers of tiger salamanders have been found lying in piles beneath suitable cover or underground (Indiviglio 1997).

Terrestrial Biomes: forest

This mole salamander is the largest land dwelling salamander in North America. It also has the greatest range of any other North American salamander, spreading in range from southeastern Alaska east to the southern part of Labrador, and south throughout all of the United States down to the southern edge of the Mexican Plateau (Indiviglio 1997).

Biogeographic Regions: nearctic (Native )

The tiger salamander's food source consists of worms, snails, insects, and slugs in the wild; while captive specimens rely on smaller salamanders, frogs, newborn mice, and baby snakes. Tiger salamanders in the wild also tend to eat the same thing as captives, if opportunity presents itself (Indviviglio 1997). The larvae begin feeding on small crustaceans and insect larvae and once grown, they will feast on tadpoles and smaller salamander larvae and even small fish (Harding 1997).

They are efficient predators in their aqautic and subterranean environment, and their prey includes some insect pests.

In some places Ambystoma tigrinum are captured and sold for fish bait (Harding 1997).

The larvae are sometimes considered a nuisance in fish hatcheries. Large larvae will feed on very small fish, but their main effect might be to act as competitors with the fish. As the fish grow larger they can turn the tables and feed on the salamander larvae.

Eggs are laid in small pools and hatch within a time period of 19 to 50 days. The larvae remain in the pond until they turn into adults at 2.5 to 5 months of age. Sometimes, adult tiger salamanders remain in the aquatic larval form for their entire lives.

Development - Life Cycle: metamorphosis

Populations in the southeastern U.S. have been affected by deforestation and loss of wetland habitats and appear to be declining in many areas. According to studies in the Colorado Rockies done by Harte and Hoffman, acid rain may be responsible for this. Other studies indicate that it might not have anything to do with it (Petranka 1998). Other threats for these salamanders are being hit by cars and polluting of their ponds and habitats.

US Federal List: no special status

CITES: no special status

State of Michigan List: no special status

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: least concern

Ambystoma tigrinum migrates to the breeding ponds in late winter or early spring, usually after a warm rain that thaws out the ground's surface. Males tend to arrive earlier than the females, probably due to the fact that they live closer to the ponds during the winter months. Courtship happens during the night where the males nudge and bump other salamanders. Upon coming across a female, the male will nudge her with his snout to get her away from the other males (Harding 1997). Once away from the other males, the male walks under the females chin, leading her forward and then she nudges his tail and vent area. This behavior stimulates the male to deposit a spermatophore. The female moves her body so that the spermatophore contacts her vent, thus allowing her to take sperm into her cloaca. This behavioral movement continues and produces more spermatophores. The competition for breeding is great in this species and sometimes other males may interupt the courting pairs and replaces the spermatophores with its own. The laying of eggs occurs a night, usually 24-48 hours after the courtship and insemination. They lay the eggs and attach them with twigs, grass stems and leaves that have decayed on the bottom floor of the pond. Each mass can obtain up to 100 eggs (Harding 1997). When large enough, the masses can resemble that of a spotted salamander but the mass of a tiger salamander is less firm and is very fragile if handled. Each female produces anything from 100 to 1000 eggs per season (Harding 1997).

Key Reproductive Features: seasonal breeding ; gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); sexual ; fertilization (Internal ); oviparous

Average time to hatching: 28 days.

Average number of offspring: 37.

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male)

Sex: male: 1460 days.

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female)

Sex: female: 1460 days.

The tiger salamander (Ambystoma tigrinum) is a species of mole salamander[2] and one of the largest terrestrial salamanders in North America.[3]

These salamanders usually grow to a length of 6–8 in (15–20 cm) with a lifespan of around 12–15 years.[4] They are characterized by having markings varying in color on the back of their head, body, and tail.[5] The coloring of these spots range from brownish yellow to greenish yellow, while the rest of their back is black or dark brown.[3] They have short snouts, thick necks, strong legs, and lengthy tails.[6] Tiger salamanders are a sexually dimorphic species, as the males are larger in body size, as well as have longer and higher tails than females.[7] Their diet consists largely of small insects, snails, slugs, frogs, and worms, although it is not rare for an adult to turn cannibalistic and consume its own kind.[5][8] Cannibalism in these salamanders can almost always be traced back to a large volume of competing predators and lack of prey in the area.[9] If the opportunity presents itself, tiger salamanders will even feed on other smaller salamander species, lizards, snakelets (baby snakes), and newborn mice.[8][10]

Illinois citizens voted for the eastern tiger salamander as state amphibian in 2004, and the legislature enacted it in 2005.[11]

Tiger salamanders habitats range from woodlands crowded with conifer and deciduous trees to grassy open fields.[3] These amphibians are secretive creatures who spend most of their lives underground in burrows, making them difficult to spot.[4] One significant requirement these salamanders need to thrive is loose soil for burrowing.[12] Tiger salamanders are almost entirely terrestrial as adults, and usually only return to the water to breed. The ideal breeding condition for tiger salamanders ranges from wetlands, such as cattle ponds and vernal pools, to flooded swamps.[5] The colonization of wetlands by tiger salamanders has been postively related to the area of the wetlands.[13] This species is most commonly found on the Atlantic coast from New York down to Florida.[14] They are known, however, to be the widest ranging species of salamander in North America and have been found in smaller populations from coast to coast.[6] Ambystoma tigrinum populations occurring in northern and eastern regions of the United States are thought to be native populations as evidence from a study uncovered the species in these regions seem to be from relict populations. The species which occur on the west coast of the United States are not necessarily native occurring to the region and occur as a result of introduction for sport fishing bait, which has resulted in hybridization.[15] Though tiger salamanders are not indicators of an ecosystem, they are good indicators of a healthy environment because they need good moist soil to burrow in. But pond disturbance, invasive fish, and road construction threaten the annual population.[16]

Like all ambystomatids, they are extremely loyal to their birthplaces, and will travel long distances to reach them. Some research has shown that females will travel farther than males.[17] However, a single tiger salamander has only a 50% chance of breeding more than once in its lifetime. In a study conducted in South Carolina, breeding migrations of adult tiger salamanders began in late October or November for males and November through February for females.[18] The tiger salamander's ideal breeding period is somewhere between the late winter and early spring, once the ground is warm enough and the water is thawed.[12] Males nudge a willing female to initiate mating, and then deposit a spermatophore on the lake bottom. Some males known as sneaker males will mimic female behavior in order to trick females in taking their spermatophore without alerting the male rival.[19] There appears to be no relation between size and mating success.[20] However, females prefer mates with longer tails over mates with shorter tails.[7] About 48 hours after insemination, the female is ready to deposit her eggs in the breeding pool.[12] One female can lay up to 25–30 eggs per egg mass. She carefully attaches the eggs to secure twigs, grass, and leaves at the bottom of the pool to ensure her eggs safety.[21] In about 12–15 days time, the eggs will be fully hatched and ready to mature in the pool.[21] It takes a tiger salamander approximately three months to reach full maturity and leave the breeding pool.[21] Large-scale captive breeding of tiger salamanders has not been accomplished, for unknown reasons.

The larva is entirely aquatic, and is characterized by large external gills[22][23] and a prominent caudal fin that originates just behind the head, similar to the Mexican axolotl. Limbs are fully developed within a short time of hatching. Some larvae, especially in seasonal pools and in the north, may metamorphose as soon as feasible. These are known as small morph adults. Other larvae, especially in ancestral pools and warmer climates, may not metamorphose until fully adult size. These large larvae are usually known as 'waterdogs',[24] and are used extensively in the fishing bait and pet trades. Some populations may not metamorphose at all, and become sexually mature while in their larval form. These are the neotenes, and are particularly common where terrestrial conditions are poor.

Although immune themselves, tiger salamanders transmit Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, which is a major worldwide threat to most frog species by causing the disease chytridiomycosis.[25] Tiger salamanders also carry ranaviruses, which infect reptiles, amphibians, and fish. Using tiger salamander larvae as fishing bait appears to be a major source of exposure and transport to wild populations. One of these ranaviruses is even named the Ambystoma tigrinum virus (ATV). This ranavirus only transmits to other salamanders and was not found in fish or other amphibians.[26] Severe mortality of tiger salamander larvae sometimes occurs from recurring ranavirus infections.

The California tiger salamander (Ambystoma californiense)[27] (listed at Vulnerable), the barred tiger salamander (A. mavortium), and the plateau tiger salamander (A. velasci) were all once considered subspecies of A. tigrinum, but are now considered separate species. Genetic studies made it necessary to break up the original A. tigrinum population, though some hybridization between groups occurs.

The California tiger salamander is now federally listed as an endangered species mostly due to habitat loss; however, very few studies have been performed on this species.[28]

The axolotl is also a relative of the tiger salamander.[29][30] Axolotls live in a paedomorphic state, retaining most characteristics of their larval stage for their entire lifespans. While they never metamorphose under natural conditions, metamorphosis can be induced in them, resulting in a form very similar to the plateau tiger salamander. This is not, however, their natural condition, and dramatically shortens their lifespan.

The tiger salamander (Ambystoma tigrinum) is a species of mole salamander and one of the largest terrestrial salamanders in North America.