mk

имиња во трошки

Accidental visitor.

La chova de picu roxu (Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax) ye un ave de la familia de los córvidos, orde paseriformes.

En munches zones del llevante español como en Murcia, son llamaes cucalas.[ensin referencies]

D'un llargor averáu de 40 cm, suel tener les plumes de color negru polencu con rellumos metálicos que según la incidencia del sol dan-y unos matices azules y verdosos, les pates coloraes, y el picu coloráu, llargu y curváu (anaranxáu nes aves más nueves).

Habita en zones de mariña y monte con cantiles, cuantimás nes proximidaes de zones ganaderes o cortaos fluviales. Amás, en Trujillo, Cáceres, hai una colonia de choves que supera a la de palombos.

Aliméntense principalmente d'inseutos, especialmente de viermes y los sos bárabos.

Los niales de les colonies asitiar en cueves y repises de ribayos y cantiles. La puesta consta de 3 ó 6 güevos que pon a abril y xunu.

Esta páxina forma parte del wikiproyeutu Aves, un esfuerciu collaborativu col fin d'ameyorar y organizar tolos conteníos rellacionaos con esti tema. Visita la páxina d'alderique del proyeutu pa collaborar y facer entrugues o suxerencies.

Esta páxina forma parte del wikiproyeutu Aves, un esfuerciu collaborativu col fin d'ameyorar y organizar tolos conteníos rellacionaos con esti tema. Visita la páxina d'alderique del proyeutu pa collaborar y facer entrugues o suxerencies. La chova de picu roxu (Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax) ye un ave de la familia de los córvidos, orde paseriformes.

En munches zones del llevante español como en Murcia, son llamaes cucalas.[ensin referencies]

Dağqarğası (lat. Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax) — qarğakimilər fəsiləsindən quş.

Uzunluğu 37–42 sm, kütləsi 220–450 q-dır; erkəkləri dişilərindən iri olur. Dimdiyi uzun, ensiz, aşağıya oraqşəkilli əyilmiş qanadları uzundur. Lələk örtüyü yaşıl, göy və al-qırmızı çalarlı qaradır; dimdiyivə ayaqları qırmızıdır. Əsasən, Mərkəzi və Cənubi Avropanın, Şimal-Qərbi və Şərqi Afrikanın (Efiopiya), Cənubi Sibirin, Cənub-Qərbi, Orta və Mərkəzi Asiya dağlarının çöl və çəmənlərində yaşayır. Qafqaz, Altay, Sayan və Baykalarxasında yayılmışdır. Dəniz səviyyəsindən nival qurşağadək, adətən, 1200–4800 m-ədək daha yüksəklikdə yuvalayır; dağlarda mövsümi yerdəyişmələr edir. Yüksəklikdə manevr edən quşdur. Əsasən, sürü halında yaşayır. Azərbaycanda bu quş bəzən qırmızıdimdik dağqarğasıda adlanır. Qobustan, Zuvand və Naxçıvanda məskunlaşmışdır. Hərşeyyeyən quşlardır; rasionunun əsas hissəsini torpaq cücüləri, bitki toxumları (o cümlədən, becərilən taxıl bitkilərini), giləmeyvə təşkil edir; həmçinin xırda sürünənləri, quşları və onların yumurtalarını, tullantı və cəmdəyi də yeyir. Dik qayalar arasında, sıldırımlı sahillərdə və tikililərdə ayrı-ayrı cütlər şəklində və kiçik koloniyalarla yuvalayırlar. Yuvası iri, kasaşəkilli, yaxud çoxlu yun və tükdən ibarət qalın döşənəkli platforma şəklində olur. 1–6 (adətən, 3–5) yumurta qoyur, dişi 17–18 gün kürt yatır; erkək bu dövrdə onu yemləyir. Ətcəbalalar yuvada 31–41 gün qalır.[1]

![]() Evit sterioù all ar ger kavan, gwelit ar pennad Kavan (disheñvelout).

Evit sterioù all ar ger kavan, gwelit ar pennad Kavan (disheñvelout).

Ar c'havan beg ruz a zo un evn eus kerentiad ar brini, Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax an anv skiantel anezhañ.

Bevañ a ra an evn er menezioù ha war an aodoù dreist-holl.

E Breizh ne vez kavet ken nemet un dornadig koubladoù en inizi (Eusa, ar Gerveur,... ) ha war tornaodoù ar C'hab ha Kraozon.

E-tro ar bloavezhioù 1985 e oa etre 25 ha 35 koublad e Breizh[1].

Loen arouez Kernev-Veur eo ar c'havan beg ruz ha graet e vez palores anezhañ e kerneveureg.

![]() Evit sterioù all ar ger kavan, gwelit ar pennad Kavan (disheñvelout).

Evit sterioù all ar ger kavan, gwelit ar pennad Kavan (disheñvelout).

Ar c'havan beg ruz a zo un evn eus kerentiad ar brini, Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax an anv skiantel anezhañ.

La gralla de bec vermell (Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax) és un ocell de l'ordre dels passeriformes.

Fa un niu amb palets entre les esquerdes dels penya-segats (a 1000-2100 m d'altitud) i a l'abril-maig hi pon 3 o 6 ous. La femella els cova durant 18-21 dies i alimenten els pollets que en neixen durant 40 dies.[1]

Menja cucs, insectes, aràcnids i deixalles dels excursionistes que cerquen als prats alpins.

Els seus depredadors més habituals com a adult són el falcó pelegrí, l'àliga daurada i el duc, mentre que durant la seua etapa al niu com a immadur pot arribar a ésser devorat pel corb. És parasitat pel cucut reial.

Viu a gairebé totes les muntanyes d'Euràsia. Generalment, viu per sobre dels 1000 m d'altitud, sempre que hi hagi cingleres i fa moviments de caràcter altitudinal a l'hivern que la poden portar a zones veïnes de menor altitud, i al litoral, on és molt rara o ocasional.

Les seues vuit subespècies viuen a Irlanda, Gran Bretanya, l'Illa de Man, sud d'Europa, els Alps, Àfrica del Nord, Etiòpia, Àsia Central, Índia i Xina.

Als Pirineus pugen durant l'estiu però, fonamentalment, viuen al Prepirineu. Així mateix, també és present al sud de Lleida i a les muntanyes de l'interior de Tarragona.

És sociable, gregària, sedentària i increïblement àgil en el vol acrobàtic arran de les parets on nia, fins i tot durant els cops de vent més huracanats.

La gralla de bec vermell (Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax) és un ocell de l'ordre dels passeriformes.

Aelod o'r genws Pyrrhocorax yn nheulu'r brain yw'r Frân goesgoch (enw gwyddonol: Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax; Saesneg: Red-billed chough).

Mae'n aderyn gweddol fawr, 37–41 cm o hyd a 68–80 cm ar draws yr adenydd, ac mae'r pig a choesau coch yn ei wneud yn hawdd ei adnabod. Mae'n nythu ym Mhrydain, de Ewrop yn enwedig yr Alpau, rhannau mynyddig o ganolbarth Asia ac yn yr Himalaya, lle gall fod yn gyffredin iawn, er enghraifft yn Bhutan mae'n un o'r adar mwyaf cyffredin. Ceir hefyd boblogaeth yn ucheldiroedd Ethiopia. Fel rheol mae'n nythu mewn creigiau, un ai yn y mynyddoedd neu ar yr arfordir.

Fe'i ceir hefyd o gwmpas arfordir Ynys Môn, Llŷn a Sir Benfro ac yn y mynyddoedd, yn enwedig yn Eryri.

Yng ngwledydd Prydain mae'n aderyn sy'n gyfyngedig i'r ardaloedd Celtaidd, gorllewin yr Alban, Ynys Manaw, Cymru a Chernyw. Mae'n ymddangos ar arfbais Cernyw ac yn cael ei ystyried yn symbol o'r wlad, ond dim ond yn ddiweddar y mae ychydig o barau wedi dychwelyd i nythu yno ar ôl bod yn absennol am flynyddoedd lawer.

Ymddengys y frân goesgoch ar arfbais Sir Fflint, yn ogystal â bod yn aderyn cenedlaethol Cernyw. Caiff ei dangos hefyd ar arfbais Ysgol Maelor, Llannerch Banna oherwydd roedd y pentref ei hun unwaith oyn cael ei gynnwys yn ffiniau hen Sir Fflint.

Dyma ysgrifennodd Gilbert White yn 1778:

Dyma brawf i frain coesgoch ymledu llawer yn ehangach ar un adeg, gan gynnwys yr ardal yn nrama’r Brenin Llŷr gan Shakespeare, sef Caint. Mae’r mosaic Rufeinig yma [2] o Fila Rufeinig Brading hefyd yn dangos bod brain coesgoch yn byw yn ardal Ynys Wyth ddwy fil o flynyddoedd yn ôl, tan yr 1880au meddai haneswyr lleol[1]. Ac yng Nghaersallwg (Salisbury) bu tafarn o’r enw The Chough Inn (The Blue Boar erbyn heddiw) sydd yn dyddio’n ôl i’r 19g.

Rhestr Wicidata:

rhywogaeth enw tacson delwedd Aderyn rhisgl Falcunculus frontatus Aradrbig Eulacestoma nigropectus Brân paith Stresemann Zavattariornis stresemanni Cigydd gwrychog Pityriasis gymnocephala Cigydd-sgrech gribog Platylophus galericulatus Pêr-chwibanwr llwyd Colluricincla harmonica Piapiac Ptilostomus afer Pioden adeinlas Cyanopica cyanus Pioden adeinwen y De Platysmurus leucopterus Sgrech frown Psilorhinus morio Sgrech Pinyon Gymnorhinus cyanocephalus Sgrech-bioden gynffon rhiciog Temnurus temnurusAelod o'r genws Pyrrhocorax yn nheulu'r brain yw'r Frân goesgoch (enw gwyddonol: Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax; Saesneg: Red-billed chough).

Mae'n aderyn gweddol fawr, 37–41 cm o hyd a 68–80 cm ar draws yr adenydd, ac mae'r pig a choesau coch yn ei wneud yn hawdd ei adnabod. Mae'n nythu ym Mhrydain, de Ewrop yn enwedig yr Alpau, rhannau mynyddig o ganolbarth Asia ac yn yr Himalaya, lle gall fod yn gyffredin iawn, er enghraifft yn Bhutan mae'n un o'r adar mwyaf cyffredin. Ceir hefyd boblogaeth yn ucheldiroedd Ethiopia. Fel rheol mae'n nythu mewn creigiau, un ai yn y mynyddoedd neu ar yr arfordir.

Fe'i ceir hefyd o gwmpas arfordir Ynys Môn, Llŷn a Sir Benfro ac yn y mynyddoedd, yn enwedig yn Eryri.

Yng ngwledydd Prydain mae'n aderyn sy'n gyfyngedig i'r ardaloedd Celtaidd, gorllewin yr Alban, Ynys Manaw, Cymru a Chernyw. Mae'n ymddangos ar arfbais Cernyw ac yn cael ei ystyried yn symbol o'r wlad, ond dim ond yn ddiweddar y mae ychydig o barau wedi dychwelyd i nythu yno ar ôl bod yn absennol am flynyddoedd lawer.

Ymddengys y frân goesgoch ar arfbais Sir Fflint, yn ogystal â bod yn aderyn cenedlaethol Cernyw. Caiff ei dangos hefyd ar arfbais Ysgol Maelor, Llannerch Banna oherwydd roedd y pentref ei hun unwaith oyn cael ei gynnwys yn ffiniau hen Sir Fflint.

Alpekragen (latin: Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax) er en fugleart blandt kragefuglene. Den er udbredt fra de Britiske Øer i øst videre gennem Sydeuropa og Nordafrika til Centralasien, Indien og Kina. Alpekragen er cirka 40 centimeter i længden med et vingefang på op til 90 centimeter. Fjerdragten er sort. Næbbet er rødt, langt og nedadbøjet. Benene er røde.

Alpekragen (latin: Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax) er en fugleart blandt kragefuglene. Den er udbredt fra de Britiske Øer i øst videre gennem Sydeuropa og Nordafrika til Centralasien, Indien og Kina. Alpekragen er cirka 40 centimeter i længden med et vingefang på op til 90 centimeter. Fjerdragten er sort. Næbbet er rødt, langt og nedadbøjet. Benene er røde.

Die Alpenkrähe (Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax) ist eine Vogelart aus der Familie der Rabenvögel (Corvidae). Die schwarz gefiederten Vögel mit schmalem, gebogenem rotem Schnabel waren während der letzten Kaltzeit in weiten Teilen Eurasiens beheimatet. Heute sind sie meist nur noch in den Gebirgen, Hochländern und Küstenregionen der Paläarktis und Äthiopiens anzutreffen. Insbesondere durch den Wandel der Landwirtschaft ab dem 19. Jahrhundert ging die Art in Europa noch weiter zurück. Ihr Habitat besteht aus Weideland und offenen Flächen mit niedriger, spärlicher Grasvegetation. Dabei ist die Alpenkrähe vor allem auf ein ausreichendes Angebot an Felsnischen zur Brut angewiesen. Sie ernährt sich vorwiegend von Samen und Beeren sowie von Insekten und anderen Wirbellosen. Die Art bildet monogame, lebenslange Brutpaare und baut ihr Nest für gewöhnlich auf überdachten Felsvorsprüngen, aber bisweilen auch in Gebäudenischen oder Tierbauten. Die Gelegegröße schwankt zwischen einem und sechs Eiern, meist legt das Weibchen drei bis fünf Eier.

Die Erstbeschreibung der Alpenkrähe durch Carl von Linné stammt aus dem Jahr 1758. Ihre nächste Verwandte ist die Alpendohle (Pyrrhocorax graculus), mit der sie die Gattung der Bergkrähen (Pyrrhocorax) bildet. Insgesamt werden acht rezente und eine ausgestorbene Unterart unterschieden, ihre Abgrenzung ist aber oft problematisch. Zwar gilt die Alpenkrähe global als nicht bedroht, in Europa ist ihr Bestand allerdings weiterhin rückläufig. Die Art ist deshalb in mehreren Ländern Gegenstand von Schutzprogrammen.

Mit 38–41 cm Körperlänge gehört die Alpenkrähe zu den mittelgroßen Vertretern der Rabenvögel. Sie ist schlank gebaut und zeichnet sich vor allem durch ihre langen Beine und den schmalen, länglichen und gebogenen Schnabel aus. Wie für Bergkrähen typisch fehlt ihr die Täfelung der Beine, die bei anderen Rabenvögeln üblich ist. Die Nasalborsten sind äußerst kurz und bedecken nur knapp die Nasenlöcher. Weibchen sind im Mittel geringfügig kleiner als Männchen aus der gleichen Population. Am größten sind in der Regel Alpenkrähen im Himalaja, am kleinsten Vögel von den britischen Inseln. Gewicht und Größe nehmen generell mit der geographischen Breite und mit der Höhenlage zu. Weibchen erreichen je nach Region ein Gewicht von 230–390 g und eine Flügellänge von 266–323 mm. Der weibliche Schwanz misst 125–150 mm, ihr Schnabel wird (gemessen von Spitze bis Ansatz) 47–58 mm lang. Der Laufknochen weiblicher Vögel misst zwischen 48 und 56 mm. Männliche Alpenkrähen wiegen ausgewachsen zwischen 230 und 450 g und erreichen Flügellängen von 253–357 mm. Ihr Schwanz wird 120–166 mm lang. Der Schnabel adulter Männchen misst 51–70 mm, ihr Lauf hat eine Länge von 49–63 mm.[2]

In der Färbung bestehen zwischen Weibchen und Männchen keine Unterschiede. Beide Geschlechter besitzen ein tiefschwarzes, glänzendes Alterskleid, einen roten Schnabel und rote Beine. Der metallische Schimmer des eng anliegenden Gefieders ist je nach Population unterschiedlich stark ausgeprägt und kann bläulich oder grünlich sein. Mit der Zeit verlieren die Federn ihren Glanz und ihre Sättigung und bleichen ins Mattbraune aus, bevor sie bei der nächsten Mauser durch neue ersetzt werden. Schnabel und Beine sind bei ausgewachsenen Vögeln karminrot. Ihre Iris ist dunkelbraun, die Krallen schwarz. Jungtiere unterscheiden sich von Altvögeln durch ihr kürzeres und lockereres Gefieder. Ihnen fehlt der metallische Schimmer adulter Individuen und ihr Gefieder erscheint heller und schmutziger. Juvenile Alpenkrähen haben bis zum ersten Herbst einen eher orangen Schnabel, der deutlich kürzer ist als der ausgewachsener Individuen.[3] Leichte Unterschiede zeigen sich auch bei den Krallen der Jungtiere, die eher dunkelbraun sind und eine helle Spitze aufweisen.[4]

Die rötliche Färbung von Schnabel und Beinen inspirierte verschiedene Legenden in der europäischen Folklore. So wurden die Vögel im mittelalterlichen und frühneuzeitlichen Großbritannien als die Wiedergänger Artus’ betrachtet, die vom Blut seiner letzten Schlacht noch immer rot gefärbt seien. Der britische Volksglaube verdächtigte sie wegen ihrer roten Schnäbel und Beine zudem als Brandstifter, was durch die Beobachtungen von brütenden Alpenkrähen bekräftigt wurde, die Zweige oder Stroh – vermeintliches Brennmaterial – in Gebäude trugen. Ihr charakteristisches Erscheinungsbild ließ die Alpenkrähe regional auch zum Wappenraben werden, etwa für Cornwall oder Thomas von Canterbury.[5]

Alpenkrähen sind wendige und vielseitige Flieger. Von Alpendohlen unterscheiden sie sich im Flug vor allem durch die rechteckigen und tiefer gefingerten Flügel, den geraden Hinterrand des Schwanzes und den längeren Hals und Schnabel. Im Streckenflug fliegen sie zügiger als Raben und Krähen (Corvus spp.), ähneln diesen aber in ihren gleichmäßigen, kräftigen Flügelschlägen. Häufig verfällt die Alpenkrähe in akrobatische Flugmanöver. So vollführt sie beispielsweise Sturzflüge mit bis zu 100 km/h, die sie erst kurz vor dem Boden wieder abbremst. Die Tiere sind in der Lage, fast senkrecht nach oben oder gegen Wind der Stärke 9 anzufliegen. Ihre Flugmanöver vollführt die Alpenkrähe meist dicht an Felsklippen oder knapp über dem Boden, während die nahe verwandte Alpendohle dafür den offenen Luftraum bevorzugt. Auf dem Boden schreitet die Art mit gemessenem Schritt oder hüpft in großen Sprüngen. In Hast verfällt sie in den für Rabenvögel typischen Trippelschritt, wobei sie hüpft, mit beiden Beinen kurz hintereinander aufsetzt und dann wieder hüpft. Anders als viele Arten der Familie nutzt die Alpenkrähe kaum Bäume oder Büsche als Sitzwarten und verbringt den Großteil ihrer Zeit auf dem Boden.[6]

Pfeifende, zwitschernde oder quäkende Rufe prägen das Lautrepertoire der Alpenkrähe. Sie können gedehnt oder abgehackt, melodiös oder rau ausfallen, unterscheiden sich jedoch in der Regel deutlich von den krächzenden oder schäkernden Lautäußerungen anderer Rabenvögel. Viele Rufe der Art sind auch von der Alpendohle bekannt, erfüllen dort aber offenbar andere Funktionen in der Kommunikation. Das Vokabular der Alpenkrähe gilt als komplex, weil es sehr variabel ist und der gleiche Ruf je nach Kontext, Individuum oder Betonung unterschiedliche Botschaften transportieren kann. Ein häufiger Ruf ist der sogenannte Triller, der wie griää, tschiouu oder auch querschlägerartig tijaff klingen kann. Er ist hoch, gedehnt und endet meist abgehackt. In Unruhe lässt die Alpenkrähe ein kju vernehmen, das an Dohlen gemahnt. Bei Alarm oder im Streit verfällt sie in ein raues ker ker ker. Einen Balz- oder Reviergesang im eigentlichen Sinne besitzen Alpenkrähen nicht. Mitunter lassen sie aber einen leisen Subsong vernehmen, der trällernd und schwätzend Versatzstücke anderer Rufe aneinanderreiht.[7]

Pyrrhocorax-Fossilien finden sich bereits im späten Pliozän Europas,[8] die Alpenkrähe lässt sich das erste Mal an der Plio-Pleistozän-Grenze (Villafranchium, etwa 2,6 mya) für das heutige Ungarn und Spanien nachweisen. Wie auch die Alpendohle war sie ein typischer Vertreter der Eiszeitfauna und bewohnte weite Teile der damals vorherrschenden Mammutsteppe von Gibraltar bis ins heutige Hessen und Tschechien. Durch das Vorrücken der Wälder im Holozän verschwand die Alpenkrähe weitgehend aus den gemäßigten Breiten. Vereinzelt wirkte die menschliche Weidewirtschaft dieser Entwicklung entgegen, indem sie offene Flächen schuf und erhielt und den Vögeln eine Nahrungsgrundlage in Form von Trockenrasen bot. Frühe naturgeschichtliche Werke deuten darauf hin, dass die Alpenkrähe im frühen 16. Jahrhundert noch ein weit größeres europäisches Areal als heute bewohnte. So wurde sie etwa von Valerius Cordus als Bewohner der Donaufelsen bei Kelheim und Passau erwähnt. Mit der Intensivierung der Landwirtschaft und dem Rückgang der Schafweidewirtschaft ab dem 19. Jahrhundert verschwand die Alpenkrähe vielerorts von ihren angestammten europäischen Brutplätzen. Die Verfolgung durch den Menschen trug zu dieser Entwicklung bei. So verschwand die Art in weiten Teilen der Alpen, der britischen Inseln und von allen Kanareninseln außer La Palma. Im Gegensatz dazu blieb die Art in Asien weitgehend unbehelligt und wird bis heute nicht verfolgt, auch die Weidewirtschaft ist dort noch weit verbreitet. Dementsprechend ist das asiatische Artareal der Alpenkrähe größer und geschlossener als das europäische.[9]

Das heutige Verbreitungsgebiet der Alpenkrähe zerfällt in drei Teile: ein großflächiges asiatisches Areal, eine Vielzahl zersplitterter und kleinräumiger Brutgebiete in Europa und Nordafrika sowie vier kleine Brutpopulationen im Äthiopischen Hochland. In Asien reicht die Verbreitung vom Gelben Meer über den Nordwesten Chinas, das südöstliche Sibirien und die Mongolei bis auf das mongolische und tibetische Plateau.[10] Von dort aus folgt das Artareal den großen Gebirgsketten Südasiens, dem Himalaya, dem Hindukusch, dem Elburs und dem Zāgros-Gebirge westwärts bis in den Kaukasus und nach Anatolien. Die großen Trockensteppen und Wüsten werden von der Alpenkrähe gemieden. In der Türkei ist sie überwiegend entlang der südlichen Gebirgsketten anzutreffen. Westlich davon schließen sich einige kleinräumige Vorkommen in der Ägäis und auf dem Balkan an. Während die Alpenkrähe noch in weiten Teilen des Apennins und im Norden Siziliens brütet, ist sie aus den Ostalpen seit Jahrzehnten verschwunden. Nur im Westen des Gebirgszugs kommt sie noch vor. Entlang der europäischen Atlantikküsten in Irland, Großbritannien und Frankreich bestehen versprengte, aber weitgehend stabile Populationen. Mehr oder weniger flächendeckend kommt die Alpenkrähe nur in den Pyrenäen und auf der Iberischen Halbinsel vor. Jenseits der Straße von Gibraltar schließen sich Vorkommen im Atlas an, eine heute stark isolierte Population besteht darüber hinaus auf La Palma.[11] Die Vorkommen im nördlichen und südlichen Hochland von Abessinien sind durch die Sahara und die arabischen Wüsten von den anderen Populationen getrennt.[12] Alpenkrähen sind Standvögel und haben nur schwache Wanderungstendenzen. Im Winter verlassen einige Populationen die Gipfelregionen von Gebirgen und ziehen ins Tiefland und in die Täler hinab. Die Nahrungssuche veranlasst die Tiere bisweilen zu längeren Wanderungen, dabei legen sie aber selten mehr als zehn Kilometer zurück.[13]

Die Alpenkrähe bewohnt zwei verschiedene Habitattypen: einerseits weitläufige, offene Viehweiden mit Felsen in der näheren Umgebung und andererseits Steilklippen an den europäischen Westküsten. Als Nahrungshabitat sind Strände und magere, trockene Rasen (2–4 cm Höhe) mit hohem Insektenaufkommen wichtig. Im westlichen Teil des kontinentalen Verbreitungsgebiets sind dies seit dem Holozän vor allem Schafweiden, weiter östlich ist die Alpenkrähe auch auf Pferde- und Yakweiden zu finden. Abseits der Weidewirtschaft können Wind, Hanglage oder Sonneneinstrahlung dazu beitragen, dass geeignete Nahrungshabitate für die Art entstehen. Wichtig ist offenbar auch Trinkwasser im Lebensraum. Wo Brutmöglichkeiten in Felsen fehlen, nimmt die Alpenkrähe auch Nistplätze in Gebäuden an. Dabei kann es sich um Ruinen, moderne Betonbauten oder auch um bewohnte Häuser handeln, solange das Nest und seine nähere Umgebung ungestört bleiben. In Zentralasien sind die Vögel oft sogar in der Nähe von oder in Dörfern anzutreffen, in Westchina und der Mongolei sind sie vielerorts ganzjährige Bewohner von Städten. Dort fungieren meist innerstädtische Grasflächen als Nahrungsgründe.[14]

Die kontinentalen Lebensräume der Alpenkrähe liegen meist zwischen 2000 und 3000 m über Meereshöhe. Vereinzelt – etwa in Andalusien – nutzt die Art zwar auch tiefer gelegene Habitate, in höheren Lagen ist sie aber in aller Regel häufiger.[15] Wo es der landschaftliche Raum zulässt, steigt sie oft noch weiter aufwärts. So ist sie im Himalaya im Sommer bis auf 6000 m anzutreffen, am Mount Everest wurden noch in 7950 m Höhe Individuen gesichtet.[14]

Alpenkrähen sind wie die meisten Rabenvögel Allesfresser, ernähren sich aber vorwiegend von Insekten und anderen Wirbellosen. Der Magen der Art ist ein ausgeprägter Weichfressermagen, der auf die Verdauung weicher, flüssigkeitsreicher Nahrungsstücke ausgelegt ist. Ergänzt wird das Nahrungsspektrum vor allem durch Samen, Beeren und andere Früchte. Je nach Habitat und Jahreszeit können unterschiedliche Wirbellosen-Gruppen zur wichtigsten Nahrungsquelle werden. Häufig bilden Ameisen, Käfer oder Regenwürmer den Hauptbestandteil des Futters. Mit dem Rückgang der Insektenvorkommen im Herbst und Winter rücken zunehmend Getreidesamen und Beeren in den Vordergrund. Das Spektrum reicht dabei von Schlehen, Kreuzdorn-Beeren und Oliven über kultivierte Äpfel und Feigen bis hin zu Hafer oder Gerste. Bevorzugt wird offenbar Getreide, Früchte frisst die Alpenkrähe weniger gern als die Alpendohle. Vereinzelt fressen die Vögel auch Kleinsäuger wie Spitzmäuse, Eidechsen oder die Eier anderer Arten, dies bildet aber eher die Ausnahme. Im Gegensatz zur Alpendohle und zu den meisten anderen Arten der Familie meidet die Alpenkrähe Aas und menschliche Abfälle für gewöhnlich.[16]

Gliederfüßer und Regenwürmer erbeutet die Alpenkrähe vor allem, indem sie mit ihrem langen, dünnen Schnabel in der obersten Bodenschicht stochert. Ameisen picken die Vögel in sehr schneller Folge von der Erdoberfläche auf. Für die Nahrungssuche bevorzugt die Alpenkrähe vor allem feuchte Stellen im Rasen oder aufgewühlte und bloße Erde. Teilweise hebt sie auf der Suche nach Nahrung auch bis zu 20 cm tiefe Löcher aus. Steine und getrocknete Kotfladen wenden die Vögel, um an darunter lebende Wirbellose zu gelangen. Ihr Schnabel ermöglicht es der Alpenkrähe auch, in weichem Kot nach Insektenlarven zu stochern, ohne dabei das Gefieder zu beschmutzen. Nach Möglichkeit wird die Nahrung am Boden aufgenommen; nur wenn es die Situation erfordert, begibt sie sich auch ins Geäst von Büschen oder Bäumen. Oft versucht sie dann auch, Nahrung im Rüttelflug aufzuspüren. Dass überschüssige Nahrung versteckt wurde, konnte bisher nur bei Vögeln beobachtet werden, die in Volieren gehalten wurden. Die Alpenkrähe trinkt oft, vor allem nach Aufnahme klebriger oder zäher Nahrung.[17]

Alpenkrähen sind gesellige Vögel und leben die meiste Zeit des Jahres in kleinen Schwärmen. Verpaarte Individuen bleiben in der Regel in der Nähe ihres Partners und schließen sich Schwärmen gemeinsam an. Gelegentlich können Schwärme stark anwachsen und dann mehrere Hundert oder Tausend Vögel umfassen. Das kann das ganze Jahr über geschehen, in Europa aber meist im September und Oktober, wenn die ausgeflogenen Jungvögel hinzustoßen. In den Gruppen kann es zu aggressiven Auseinandersetzungen, Imponiergehabe oder akustisch einberufenen Ansammlungen kommen, gewalttätige Angriffe mit Verletzungen sind aber sehr selten. Konflikte werden meist durch Drohgesten des überlegenen Tiers (aufrechte Haltung von Oberkörper und Schnabel) beendet. Schwärme nächtigen für gewöhnlich gemeinsam und gehen auch geschlossen auf Nahrungssuche. Wo sich die Verbreitungsgebiete überlappen, sind Alpenkrähen gelegentlich mit Dohlen und Alpendohlen vergesellschaftet. Zur Konkurrenz und Auseinandersetzung kommt es dabei nicht, weil die Ernährungsweisen der Arten sehr unterschiedlich sind, auch Nistplatzkonkurrenz besteht in der Regel nicht. Seltener schließen sich Alpenkrähen mit größeren Rabenvögeln wie Aaskrähen (Corvus corone) oder Kolkraben (C. corax) zusammen. Fressfeinde werden von den Schwarmvögeln gemeinsam gehasst. Das begrenzte und oft gedrängte Nistplatzangebot veranlasst die Art gelegentlich dazu, in kleinen, lockeren Kolonien zu brüten. Die Brutpaare verteidigen dabei die unmittelbare Nestumgebung von wenigen Hundert Metern gegen Artgenossen, Nahrungsreviere werden dagegen nicht verteidigt.[18]

Brutpartner finden sich bei der Alpenkrähe in den Nichtbrüterschwärmen zusammen. Das Weibchen wird dabei vom Männchen mit einem Balztanz umworben, auf den Gefiederkraulen folgt. Anschließend bietet es dem Weibchen ein hochgewürgtes Nahrungsstück an. Auch nach der erfolgreichen Verpartnerung füttert das Männchen das Weibchen regelmäßig, wenn es von ihm dazu aufgefordert wird. Brutpaare, die das zweite Jahr überstanden haben, bleiben meist bis zum Tod eines Partners zusammen. Zur ersten Brut kommt es frühestens im Alter von zwei Jahren, erfolgreiche Brüter sind aber in aller Regel drei Jahre alt oder älter. Das Nest wird im Spätwinter von beiden Partnern gemeinsam gebaut und befindet sich, wenn möglich, abseits von den Nestern anderer Paare. Als Nistplätze werden überdachte Felsnischen und Schächte bevorzugt. Die Alpenkrähe ist aber kein Höhlenbrüter im eigentlichen Sinne, die Nestzugänge sind meist breit und offen, sodass das Nest im Flug erreicht werden kann. Neben Felsen werden lokal auch Lehmhänge, Fenstersimse, Dachstühle oder Schornsteine zur Brut verwendet. Voraussetzung ist, dass der Nistplatz ausreichend geschützt, zugänglich und ungestört ist. Das Nest besteht aus einer unförmigen Schüssel von bleistiftdicken, miteinander verwobenen Zweigen, die mittig mit Wolle, Haaren und Pflanzensamen gepolstert wird. Der Nestbau nimmt zwei bis vier Wochen in Anspruch.[19]

Die Gelege der Alpenkrähe bestehen aus einem bis sieben, meist drei bis fünf Eiern mit beiger bis hellbrauner Farbe und dunklen Sprenkeln. Das Weibchen legt sie in der Regel acht bis zehn Tage nach Abschluss des Nestbaus.[20] In Eurasien findet das überwiegend zwischen Mitte April und Mai statt. Das Weibchen bebrütet die Eier alleine, während es vom Männchen mit Futter versorgt wird. Gelegentlich werden Artgenossen, wahrscheinlich Jungen aus Vorjahresbruten, als Bruthelfer tätig. Die Jungen schlüpfen nach 17–21 Tagen und werden nach 36–41 Tagen flügge. Nach dem Ausfliegen bleiben sie noch etwa 50 Tage im Familienverband, bevor sich die Familie einer größeren Gruppe von Artgenossen anschließt.[21] Die Ausflugrate liegt auf den britischen Inseln (ohne Komplettverluste des Geleges) zwischen 42 und 76 %; die Totalverluste schlagen örtlich mit 32 % zu Buche. Neben Nesträubern kann auch der Befall der Gelege durch den Häherkuckuck (Clamator glanduarius) eine Ursache für das Scheitern von Bruten sein.[22]

Zu den Fressfeinden der Alpenkrähe zählen Uhu (Bubo bubo), Wanderfalke (Falco peregrinus)[23] oder auch Zwergadler (Hieraaetus pennatus).[24] Örtlich wird sie vom Menschen auch immer noch als Schädling oder zu Sportzwecken abgeschossen. Im Gefieder der Art fanden sich unter anderem die Milbe Neotrombicula autumnalis[25] sowie die Kieferläuse Bruelia biguttata, Philopterus thryptocephalus, je eine Menacanthus- und Myrsidea-Art[26] sowie Gabucinia delibata. Bei letzterer ist umstritten, ob es sich um einen echten Parasiten oder um einen mutualistischen Symbionten handelt. Alpenkrähen mit G. delibata im Gefieder haben nach Feldstudien in der Regel eine bessere Kondition als Individuen, denen dieser Federling fehlt.[27] Gegenüber Blutparasiten der Gattungen Plasmodium und Babesia zeigte die Art in Feldstudien eine äußerst geringe Anfälligkeit von 1 %.[28] Vereinzelt führt jedoch der Luftröhrenwurm (Syngamus trachea) zu hohen Sterblichkeitsraten in Alpenkrähen-Populationen.[22]

Die Mortalitätsrate unter Vögeln einer schottischen Population lag in Untersuchungen im ersten Lebensjahr bei 29 %, im zweiten Lebensjahr bei 26 %. Der älteste Vogel, der in freier Wildbahn gefangen wurde, war ein 17 Jahre altes Männchen, das immer noch brütete. Ein unmarkiertes Weibchen lebte vermutlich 27 Jahre lang in Cornwall. Zoo- und Volierenvögel erreichten ein Alter von 28 und 31 Jahren, brüteten aber in den letzten Lebensjahren oft nicht mehr.[29]

Die Erstbeschreibung der Alpenkrähe stammt aus der 10. Auflage der Systema Naturae von Linné aus dem Jahr 1758.[1] Von Linné stellte sie aufgrund ihres länglichen, gebogenen Schnabels als Upopa Pyrrhocorax zu den Wiedehopfen, ordnete sie aber in der 12. Auflage der Gattung Corvus zu, die damals noch alle Rabenvögel umfasste. Marmaduke Tunstall errichtete schließlich 1771 die Gattung Pyrrhocorax für beide Bergkrähen und machte die Alpenkrähe durch Homonymie zu ihrer Typusart.[30] Der Name Pyrrhocorax entstammt dem Altgriechischen und bedeutet mit Verweis auf die Bein- und Schnabelfarbe der Art so viel wie „feuerroter Rabe“.

Mit ihrer Schwesterart, der Alpendohle (P. graculus), kann die Alpenkrähe Hybriden zeugen. Diese Vögel sind äußerlich eine Mischung aus beiden Arten und verfügen über das Vokabular von Vater und Mutter. Zu Hybridisierung kann es sowohl in Gefangenschaft als auch in freier Wildbahn kommen.[31] Für die Alpenkrähe werden von den meisten Autoren heute eine ausgestorbene und acht lebende Unterarten anerkannt, die Unterschiede in Verhalten und Morphologie sind aber oft nur gering. DNA-gestützte phylogenetische Analysen liegen weder für Alpendohle und Alpenkrähe noch für die einzelnen Alpenkrähen-Unterarten vor. Untersuchungen, die Maße und Lautäußerungen verschiedener Populationen verglichen, fanden keine Unterschiede zwischen den europäischen Unterarten, ordneten die Vorkommen aus Tian Shan und Äthiopien aber als basal ein.[32]

Auf Basis europäischer Bestandsschätzungen geht BirdLife International von 43.000–110.000 Brutpaaren in der Region aus, was in etwa 129.000–330.000 Individuen entspricht. Für China wird von 10.000–100.000 Brutpaaren ausgegangen. Auf Basis der europäischen Zahlen schätzt BirdLife den Weltbestand auf 263.000–1.320.000 Vögel, mahnt aber solidere Hochrechnungen an. In Europa waren die Bestände der Alpenkrähe zumindest bis in die 1980er Jahre rückläufig, seitdem ergeben sich keine klaren Trends. Ursache war vor allem der Verlust von geeigneten Brut- und Nahrungshabitaten.[11] Im Gegensatz zur Alpendohle konnte sich die Alpenkrähe nicht an den Strukturwandel seit dem 19. Jahrhundert anpassen oder gar vom Gebirgstourismus profitieren. Leichte Bestandszuwächse sind auf den Britischen Inseln und der Iberischen Halbinsel zu verzeichnen. Anders als die meisten europäischen Vorkommen gelten die Populationen im Atlas, in Klein-, Zentral- und Ostasien als groß und weitgehend stabil.[21] In ihrem asiatischen Areal gilt die Alpenkrähe als relativ, örtlich auch als sehr häufig.[14] Die vier äthiopischen Brutvorkommen umfassen nach Hochrechnungen 1.000–1.300 Individuen und kommen entsprechenden Studien zufolge für eine Einstufung als gefährdet oder stark gefährdet in Frage.[44]

Umfangreiche Schutz- und Wiederansiedlungsprogramme wurden in den letzten Jahrzehnten vor allem in Großbritannien unternommen. Dabei wurden Nisthilfen errichtet und die traditionelle Schafbeweidung gefördert, was unter Umständen mit zur Wiederansiedlung der Art im Süden Großbritanniens beitrug.[21] Die Schweiz, die aktuell noch etwa 50 Brutpaare beherbergt, stuft die Alpenkrähe auf ihrer nationalen Roten Liste als stark gefährdet ein. Als wichtigste Faktoren für den Erhalt der europäischen Bestände gelten die Erhaltung von Trockenrasen und vergleichbaren Flächen sowie der Schutz vor touristischer Erschließung und direkter Verfolgung.[45]

Die Alpenkrähe (Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax) ist eine Vogelart aus der Familie der Rabenvögel (Corvidae). Die schwarz gefiederten Vögel mit schmalem, gebogenem rotem Schnabel waren während der letzten Kaltzeit in weiten Teilen Eurasiens beheimatet. Heute sind sie meist nur noch in den Gebirgen, Hochländern und Küstenregionen der Paläarktis und Äthiopiens anzutreffen. Insbesondere durch den Wandel der Landwirtschaft ab dem 19. Jahrhundert ging die Art in Europa noch weiter zurück. Ihr Habitat besteht aus Weideland und offenen Flächen mit niedriger, spärlicher Grasvegetation. Dabei ist die Alpenkrähe vor allem auf ein ausreichendes Angebot an Felsnischen zur Brut angewiesen. Sie ernährt sich vorwiegend von Samen und Beeren sowie von Insekten und anderen Wirbellosen. Die Art bildet monogame, lebenslange Brutpaare und baut ihr Nest für gewöhnlich auf überdachten Felsvorsprüngen, aber bisweilen auch in Gebäudenischen oder Tierbauten. Die Gelegegröße schwankt zwischen einem und sechs Eiern, meist legt das Weibchen drei bis fünf Eier.

Die Erstbeschreibung der Alpenkrähe durch Carl von Linné stammt aus dem Jahr 1758. Ihre nächste Verwandte ist die Alpendohle (Pyrrhocorax graculus), mit der sie die Gattung der Bergkrähen (Pyrrhocorax) bildet. Insgesamt werden acht rezente und eine ausgestorbene Unterart unterschieden, ihre Abgrenzung ist aber oft problematisch. Zwar gilt die Alpenkrähe global als nicht bedroht, in Europa ist ihr Bestand allerdings weiterhin rückläufig. Die Art ist deshalb in mehreren Ländern Gegenstand von Schutzprogrammen.

Al'puvaroi (Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax) on lindu.

'S e eun a th' ann an cathag nan casan dearg (Laideann: Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax; Beurla: Red-billed Chough). Canar feannag na casan dearg, cathag dhearg-chasach neo cnàmhach ris cuideachd. Tha e a' buntainn don teaghlach Corvidae. Tha iad a' neadachadh anns na beanntan is na creigean faisg air a chosta, gu h-àraid ann an Èirinn, Eòrpa a Deas, Afraga a tuath is Àisia meadhanach is na h-Innseachan.

'S e eun a th' ann an cathag nan casan dearg (Laideann: Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax; Beurla: Red-billed Chough). Canar feannag na casan dearg, cathag dhearg-chasach neo cnàmhach ris cuideachd. Tha e a' buntainn don teaghlach Corvidae. Tha iad a' neadachadh anns na beanntan is na creigean faisg air a chosta, gu h-àraid ann an Èirinn, Eòrpa a Deas, Afraga a tuath is Àisia meadhanach is na h-Innseachan.

The reid-leggit craw (Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax), is a bird in the craw faimily, ane o anly twa species in the genus Pyrrhocorax.

The reid-leggit craw (Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax), is a bird in the craw faimily, ane o anly twa species in the genus Pyrrhocorax.

Tindakráka (frøðiheiti - Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax) er ein fuglur, eitt slag av kráku.

Tindakráka (frøðiheiti - Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax) er ein fuglur, eitt slag av kráku.

Togʻ qargʻa (Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax) — chumchuqsimonlar turkumining kargʻalar oilasiga mansub qush. Kattaligi zogʻchadek. Tanasining uz. 45 sm cha, ogʻirligi 270—370 g . Patlari qora rangda, dum va qanoti yashil tovlanadi; tumshugʻi va oyogʻi qizil. Markaziy va Jan. Yevropa, Shim.Gʻarbiy Afrika, Efiopiya, Oʻrta Osiyo togʻlarida tarqalgan. Oʻtroq hayot kechiradi. Togʻlarning alp mintaqasida yashaydi. 4—5 ta tuxum qoʻyib, 17—18 kun modasi bosadi. Hasharotlar, chuvalchanglar va umurtqasizlar, baʼzan mevalar bilan oziklanadi.

Η Κοκκινοκαλιακούδα είναι πτηνό της οικογενείας των Κορακιδών, που απαντά κυρίως στην κεντρική Ασία, αλλά και σε απομονωμένους πληθυσμούς σε μέρη της Ευρώπης (και στον ελλαδικό χώρο) και της βόρειας Αφρικής. Η επιστημονική ονομασία του είδους είναι Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax και περιλαμβάνει 8 υποείδη.[1]

Στην Ελλάδα απαντά το υποείδος Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax docilis (S. G. Gmelin, 1774).[1]

Είναι είδος προσαρμοσμένο να ζει σε μεγάλα υψόμετρα, μικρότερα πάντως από εκείνα της συγγενικής κιτρινοκαλιακούδας.

Η ονομασία του γένους είναι σύνθετη ελληνική και προέρχεται από τις επί μέρους λέξεις πυρρός (= αυτός που έχει το χρώμα του πυρός, της φωτιάς) + κόραξ (=ο κόρακας, το κοράκι). Γι’ αυτό ο σωστός συλλαβισμός είναι με δύο και όχι με ένα ρ, διότι η λέξη δεν προέρχεται από το πυρ: πυρρός, -ά, -όν (αρχαιοπρ.) αυτός που έχει το χρώμα της φωτιάς, ο ξανθοκόκκινος. [ΕΤΥΜ. αρχ. επίθ. (ήδη μυκ. ανθρωπωνύμια Pu-wo, Pu-wa, Pu-wi-no), που συνδ. με τις λ. πυρ και πυρσός (δωρ.). Σύμφωνα με την πιο ασφαλή ερμηνεία, οι τ. πυρρός και πυρσός προέρχονται από το ουσ. πυρ, αλλά παράγονται από διαφορετικά επιθήματα: πυρρός < *πυρ-Ρός (όπως επιμαρτυρούν οι τ. τής Μυκηναϊκής) < πυρ + επίθημα -Εός (πβ. πολιός < *πολι-Ρός), ενώ πυρσός < πυρ + επίθημα -σός. Η υιοθέτηση κοινού αρχικού τ. *πυρσ-Ρός δεν προσφέρει ικανοποιητικές απαντήσεις].[2]

Η ελληνική λαϊκή ονομασία έχει τις ρίζες της στην αρχαία ελληνική λέξη κολοιός, αγνώστου λοιπής ετυμολογίας. Η λέξη αυτή αναφέρεται συχνά τόσο στον Αριστοτέλη όσο και στον Αριστοφάνη και πιθανότατα σήμαινε το συγκεκριμένο πουλί (βλ. Κουλτούρα). Από τη λέξη αυτή προήλθε η, μεγεθυντικής σημασίας, λέξη κάλοιακας, η οποία με το επίθημα -ούδα έδωσε τη σημερινή λέξη: ΕΤΥΜ. < κάλοιακας (+ επίθημα -ούδα,πβ. πεταλ-ούδa) < κόλοιακας < αρχ. κολοιός, ίδια σημ. (κατ' αναλογίαν προςτο κόρακας), αγν. ετύμου].[3]

Η αγγλική ονομασία του είδους chough, είναι προϊόν ονοματοποιίας και οφείλεται στην χαρακτηριστική υψίσυχνη φωνή του πτηνού.[5]

Η ελληνική λαϊκή ονομασία παραπέμπει στο χρώμα του ράμφους -και των ταρσών- του πτηνού.

Απολιθώματα του γένους βρίσκονται ήδη από τα τέλη του Πλειόκαινου της Ευρώπης,[6] στη σημερινή Ουγγαρία και Ισπανία. Όπως και η κιτρινοκαλιακούδα, υπήρξε τυπικός εκπρόσωπος της ορνιθοπανίδας της Εποχής των Παγετώνων. Λόγω της επέκτασης των δασών κατά την Ολόκαινο Περίοδο εξαφανίστηκε σε μεγάλο βαθμό από τα εύκρατα γεωγραφικά πλάτη. Η ανάκαμψη άρχισε με την κτηνοτροφία και τη δημιουργία ανοικτών χώρων που προσφέρουν στα πτηνά πηγές διατροφής σε μορφή ξηρού χόρτου. Αρχειακές καταγραφές δείχνουν ότι η κοκκινοκαλιακούδα, στις αρχές του 16ου αιώνα, επεκτεινόταν σε πολύ μεγαλύτερο ευρωπαϊκό χώρο από ό, τι σήμερα. Με την εντατικοποίηση της γεωργίας και της επακόλουθης μείωσης των ζώων βοσκής, κυρίως των προβάτων, κατά τον 19ο αιώνα, εξαφανίστηκε από πολλές θέσεις της «πατρογονικής» ευρωπαϊκής επικράτειας αναπαραγωγής της. Η δίωξη από τον άνθρωπο, συνέβαλε πολύ σε αυτή την εξέλιξη. Έτσι, το είδος εξαφανίστηκε από πολλά μέρη των Άλπεων, τις Βρετανικές Νήσους (μέχρι το 2000, περίπου) και αλλού. Αντίθετα, το είδος παρέμεινε στην Ασία, κυρίως λόγω έλλειψης όχλησης και επειδή η βόσκηση είναι ακόμη ευρέως διαδεδομένη.

Η κοκκινοκαλιακούδα περιγράφηκε για πρώτη φορά από τον Λινναίο ως Upupa Pyrrhocorax, στο περίφημο έργο του Systema Naturae το 1758.[7] Μεταφέρθηκε στο σημερινό του γένος, Pyrrhocorax, από τον Άγγλο ορνιθολόγο Marmaduke Tunstall το 1771 στο έργο του Ornithologia Britannica,[8] μαζί με το μοναδικό άλλο μέλος του γένους, την Κιτρινοκαλιακούδα, P. graculus.[9] Οι πιο στενοί συγγενείς τους θεωρείτο παλαιότερα ότι, ήσαν τα κορακοειδή του γένους Corvus, ειδικά οι κάργιες,[10] αλλά οι αναλύσεις DNA του κυτοχρώματος β δείχνουν ότι το γένος Pyrrhocorax, μαζί με το γένος Temnurus, είχαν αποκλίνει νωρίς από τα υπόλοιπα μέλη της οικογένειας Corvidae.[11]

Τα υποείδη της κοκκινοκαλιακούδας κατανέμονται σε μια σχετικά στενή και κατακερματισμένη ζώνη που μοιάζει πολύ με εκείνην της συγγενικής κιτρινοκαλιακούδας. Συγκεκριμένα, εκτείνεται κατά μήκος των ορέων της νότιας Παλαιαρκτικής, με δυτικότερο όριο την Ιβηρική Χερσόνησο και τη ΒΔ. Αφρική και, ανατολικότερο όριο, την Α. Κίνα και τη Β. Ινδοκίνα.

Στην Ευρώπη, η κατανομή είναι έντονα κατακερματισμένη, με πληθυσμούς απομακρυσμένους μεταξύ τους, στο Ηνωμένο Βασίλειο, στην Ιβηρική, στην Ιταλία και στα Βαλκάνια. Απαντά ακόμη στις δυτικές Άλπεις, αλλά όχι στις ανατολικές.

Η Ασία, αποτελεί την κυριότερη επικράτεια του είδους, με τα εκεί υποείδη να συγκροτούν μια «συμπαγή» δομή, σε ευρεία ζώνη που αρχίζει από τη Μικρά Ασία και φθάνει ανατολικά μέχρι τη Σινική Θάλασσα.

Στην Αφρική, τέλος, απαντά στον μαροκινό Άτλαντα και στην Αλγερία, κυρίως όμως σε δύο -κατ’ άλλους ερευνητές, τέσσερις- απομονωμένους πληθυσμούς στην Αιθιοπία (βλ. Γεωγραφική κατανομή]], που συγκροτούν ενδημικό υποείδος.

Πηγές:[1][5][9][12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20]

(σημ. με έντονα γράμματα το υποείδος που απαντά στον ελλαδικό χώρο)

Η κοκκινοκαλιακούδα είναι ένα τυπικό μη-μεταναστευτικό είδος, με υψηλά ποσοστά ενδημισμού. Σε όλες σχεδόν τις περιοχές της επικρατείας της, ζει και αναπαράγεται μόνιμα, καθ’όλη τη διάρκεια του έτους.

Τυχαίοι, περιπλανώμενοι επισκέπτες έχουν αναφερθεί μεταξύ άλλων από το Βέλγιο, το Γιβραλτάρ, την Βουλγαρία, την Ουγγαρία, την Σλοβακία, την Αίγυπτο και την Κορέα.[21]

Στην Ελλάδα, η κοκκινοκαλιακούδα είναι επιδημητικό είδος, απαντά δηλαδή μόνιμα στις ορεινές περιοχές όλης της χώρας, αλλά είναι περιορισμένο τοπικά και δεν είναι εύκολο να την συναντήσει κάποιος.

Η κοκκινοκαλιακούδα είναι ένα τυπικό πτηνό μεγάλου υψομέτρου, αφού ο κύριος οικότοπος του είδους είναι τα ψηλά βουνά. Απαντά μεταξύ 2.000 και 2.500 μέτρων στη Β. Αφρική και, κυρίως, μεταξύ 2.400 και 3.000 μ. στα Ιμαλάια. Σε αυτή την οροσειρά φθάνει μέχρι και τα 6.000 μ. το καλοκαίρι, ενώ έχει καταγραφεί στα 7.950 μ. στο όρος Έβερεστ.[9] Συνήθως, διαχειμάζει χαμηλότερα, στα 1450-2135 μ., στα «αλπικά» λιβάδια.[22] Ωστόσο, δεν φθάνει στα υψόμετρα της συγγενικής της κιτρινοκαλιακούδας,[23] ιδιαίτερα όταν αναπαράγεται, διότι εκείνη εμφανίζει διατροφή καλύτερα προσαρμοσμένη σε μεγαλύτερα υψόμετρα.[24]

Στην Ιρλανδία, την Μεγάλη Βρετανία και την Βρετάνη αναπαράγεται επίσης στις παράκτιες βραχώδεις ακτές, αναζητώντας την τροφή της στις προσκείμενα λιβάδια χαμηλής βλάστησης, 2-4 εκ. ύψους (machair). Στο παρελθόν υπήρξε ακόμη πιο διαδεδομένη στις ακτές, αλλά περιορίστηκε λόγω της απώλειας των εξειδικευμένων της οικοτόπων.[25][26]

Στην Ελλάδα, οι κύριοι οικότοποι περιλαμβάνουν γκρεμούς και πλαγιές απότομων βράχων, σε απρόσιτες ορεινές θέσεις,[27] σε υψόμετρο που κυμαίνεται από 1.000 μέχρι 2.300 μ., σχεδόν αποκλειστικά στους υψηλότερους ορεινούς όγκους της ηπειρωτικής Ελλάδας και της Κρήτης (Handrinos & Akriotis 1997, Delestrade 1998, Ξηρουχάκης & Δρετάκης 2006). Τον χειμώνα παρατηρείται και σε χαμηλότερο υψόμετρο (μέχρι τα 400 μ.), ακόμη και κοντά σε καλλιέργειες, ειδικά σε περιόδους έντονης κακοκαιρίας. Ο βιότοπος τροφοληψίας της περιλαμβάνει βραχώδεις εκτάσεις με χέρσα χωράφια, αλπικά λιβάδια με απότομα διάσπαρτα βράχια, οροπέδια και ορεινούς βοσκότοπους με αραιή φυτοκάλυψη.[28]

Η κοκκινοκαλιακούδα, γενικά, είναι ένα μέσου μεγέθους κορακοειδές που, μπορεί να μην είναι εύκολο να παρατηρηθεί, λόγω του απρόσιτου των βιοτόπων της, αλλά είναι από τα ευκολότερα πτηνά, στην αναγνώριση πεδίου, δεδομένου ότι είναι το μοναδικό κορακοειδές με καρμινοκόκκινο ράμφος και κοκκινωπά κάτω άκρα (ταρσοί και πόδια). Ωστόσο, από κάποια απόσταση, επειδή δεν διακρίνονται αυτά τα χαρακτηριστικά, μοιάζει με την κιτρινοκαλιακούδα, ενώ σε σχέση με το κοράκι είναι σημαντικά μικρότερη σε μέγεθος. Κατά την πτήση, είναι διακριτές οι σχετικά τετραγωνισμένες πτέρυγες και η, επίσης, τετραγωνισμένη ουρά της. Όταν οι πτέρυγες είναι κλειστές, τα πρωτεύοντα ερετικά φθάνουν σχεδόν εκεί όπου τελειώνει η ουρά (στην κιτρινοκαλιακούδα, η ουρά προεξέχει σαφώς σε σχέση με τα πρωτεύοντα).[29]

Χαρακτηρίζεται από το κόκκινο, μυτερό και αρκετά καμπυλωτό ράμφος της, αρκετά μεγαλύτερο και κυρτότερο σε σύγκριση με εκείνο της κιτρινοκαλιακούδας (P. graculus). Στη βάση του ράμφους υπάρχουν πολλές, κοντές σμήριγγες, οι οποίες μόλις που καλύπτουν τα ρουθούνια. Επίσης, κατά την πτήση, τα πρωτεύοντα ερετικά πτερά φαίνονται να εξέχουν από την πτέρυγα περισσότερο. Το πτέρωμά της είναι στιλπνό μαύρο με κάποια ελαφρά, ιριδίζουσα πρασινωπή απόχρωση, ενώ κάποια υποείδη διαθέτουν απαλή μπλε απόχρωση στα φτερά τους. Με το πέρασμα του χρόνου το πτέρωμα χάνει τη στιλπνότητά του, έως ότου ακολουθήσει η επόμενη έκδυση (moult). Η ίριδα είναι σκούρα καφεκόκκινη και τα νύχια μαύρα.

Τα δύο φύλα είναι παρόμοια, με τα θηλυκά λίγο μικρότερα σε μέγεθος, αλλά αυτό είναι δυσδιάκριτο από απόσταση. Οι ενήλικες μπορούν να ξεχωρίσουν με παρατήρηση στο χέρι (sic), από το μήκος πτέρυγας, ταρσού και ράμφους, σε ακραίες μετρήσεις. Για παράδειγμα, το ράμφος των αρσενικών ατόμων είναι γύρω στα 65 χιλιοστά, ενώ των θηλυκών, γύρω στα 50 χιλιοστά. Ωστόσο, αυτό είναι αδύνατον να διαπιστωθεί στην παρατήρηση πεδίου.[30]

Τα νεαρά άτομα έχει λιγότερο στιλπνό πτέρωμα από τους ενήλικες, ενώ διαθέτουν σημαντικά μικρότερο κίτρινο ράμφος -που σταδιακά γίνεται πορτοκαλί- [31] και ροζ πόδια μέχρι το 1ο τους φθινόπωρο.[9] Επίσης, η ίριδα των οφθαλμών είναι κατάμαυρη και τα νύχια των ποδιών σκούρα καφέ.[30][32]

Υπάρχει η θεωρία ότι το μέγεθος των υποειδών αυξάνεται, από τα δυτικά προς τα ανατολικά, ακολουθώντας τον Κανόνα του Μπέργκμαν, που υποστηρίζει ότι το μέγεθος αυξάνεται παράλληλα με το υψόμετρο και τη μείωση της θερμοκρασίας (τα ασιατικά υποείδη ζουν σε υψηλότερες και ψυχρότερες περιοχές).[9][23] Ωστόσο, οι επί μέρους μετρήσεις δίνουν, κάποιες φορές, μια διαφορετική εικόνα. Για παράδειγμα, αν και οι κινεζικοί πληθυσμοί είναι κατά μέσο όρο μεγαλύτεροι σε μέγεθος από τους ευρωπαϊκούς, έχουν εν τούτοις κοντύτερα πόδια και ράμφος.[33][34] (Πηγές:[22][35][36][37][38][27][39][29][31][30][40])

(Για τα Υποείδη, βλ. Γεωγραφική κατανομή, το Μήκος σε χιλιοστά, το Βάρος σε γραμμάρια Πηγή: Cramp & Perrins 1994, pp. 105–120)

Η κοκκινοκαλιακούδα θα μπορούσε να καταταγεί στα παμφάγα κορακοειδή με, τόσο ζωϊκή, όσο και φυτική ύλη στο διαιτολόγιό της. Η φυσιολογία του στομαχιού της δείχνει ότι ανήκει στους οργανισμούς που καταναλώνουν μάλλον μαλακή, πλούσια σε υγρά, τροφή. Η λεία του είδους αποτελείται σε μεγάλο βαθμό από έντομα, αράχνες, σαλιγκάρια, σκουλήκια [31] και άλλα ασπόνδυλα που λαμβάνονται από το έδαφος, με τα μυρμήγκια, ίσως, το πιο σημαντικό θήραμα.[9] Οι κοκκινοκαλιακούδες του υποείδους της Κ. Ασίας P. p. centralis συνηθίζουν να ανεβαίνουν στη ράχη των άγριων ή οικόσιτων θηλαστικών και να τρέφονται με παράσιτα.[41] Αν και τα ασπόνδυλα αποτελούν το μεγαλύτερο μέρος της διατροφής τους, μπορούν να τραφούν και με φυτικό υλικό, συμπεριλαμβανομένων πεσμένων σπερμάτων από δημητριακά, ιδιαίτερα με την έλευση του φθινοπώρου. Μάλιστα, στα Ιμαλάια έχει αναφερθεί ότι προκαλούν ζημιές στις καλλιέργειες κριθαριού διαρρηγνύοντας τους καρπούς για να πάρουν τα σπέρματα.[9] Στις ακτές, συνηθίζουν να αρπάζουν τα αβγά από τις φωλιές των πουλιών που φωλιάζουν στην περιοχή.[37] Τέλος, αντίθετα με την κιτρινοκαλιακούδα, δεν δέχονται ανθρώπινη «τεχνητή» τροφή, όπως ψωμιά, γλυκά κ.λ.π.[42]

Τα προτιμώμενα ενδιαιτήματα αναζήτησης τροφής είναι εκείνα με χαμηλή βλάστηση, που δημιουργούνται από τη βόσκηση, π.χ. από τα πρόβατα και τα κουνέλια, οι αριθμοί των οποίων συνδέονται με την αναπαραγωγική επιτυχία του είδους. Μπορεί, επίσης, να προκύψουν κατάλληλες περιοχές σίτισης, εκεί όπου η ανάπτυξη των φυτών παρεμποδίζεται από την έκθεση σε ρεύματα ανέμου κορεσμένα με αλάτι, ή σε φτωχά εδάφη.[43][44]

Η κοκκινοκαλιακούδα χρησιμοποιεί το μεγάλο, καμπυλωτό ράμφος της για να συλλάβει μυρμήγκια, σκαθάρια και μύγες από την επιφάνεια, ή για να σκάψει για προνύμφες και άλλα ασπόνδυλα. Το τυπικό βάθος που ψάχνει είναι στα 2-3 εκατοστά, που σημαίνει ότι σιτίζεται σε εδάφη με λεπτή επιφάνεια και στα βάθη όπου διαβιούν πολλά ασπόνδυλα, είναι όμως ικανή να διατρυπήσει το έδαφος ακόμη και σε βάθος 10-20 εκ., εάν παραστεί ανάγκη.[45][46] Επίσης, θα αναζητήσει στιγμιαία τη λεία της σε δένδρα ή θάμνους, μόνον όταν δεν βρίσκει αλλού τροφή. Πίνει νερό πολύ συχνά, ιδιαίτερα όταν καταναλώνει σκληρή ή κολλώδη λεία.

Όταν τα δύο είδη καλιακούδας εμφανίζονται μαζί, υπάρχει μόνο περιορισμένος ανταγωνισμός για τροφή. Ιταλική μελέτη έδειξε ότι, κατά τη διάρκεια του χειμώνα, η διατροφή για την κοκκινοκαλιακούδα ήταν σχεδόν αποκλειστικά βολβοί γκάγκεας (Gagea sp.), ενώ η κιτρινοκαλιακούδα στρεφόταν σε βατόμουρα και καρπούς τριανταφυλλιάς. Επίσης, τον Ιούνιο, οι κοκκινοκαλιακούδες τρέφονται με προνύμφες Λεπιδοπτέρων, ενώ οι κιτρινοκαλιακούδες με νύμφες Τιπουλίδων. Αργότερα, μέσα στο καλοκαίρι, οι κιτρινοκαλιακούδες καταναλώνουν κυρίως ακρίδες, ενώ οι κοκκινοκαλιακούδες, νύμφες Τιπουλίδων, προνύμφες Διπτέρων και σκαθάρια.[24]

Η πτήση της κοκκινοκαλιακούδας είναι ισχυρή αλλά ταυτόχρονα ντελικάτη,[38], κατά την οποία διακρίνονται τα πρωτεύοντα ερετικά να εξέχουν από την πτέρυγα και να διαχωρίζονται καλά μεταξύ τους (λιγότερο διαχωρισμένα στην κιτρινοκαλιακούδα), ενώ και η ουρά εμφανίζεται σχετικά κοντή (σχέση μήκους/πλάτους, σχεδόν 1:1). Πολύ συχνά γυροπετάει (soaring).[38][39]

Η κοκκινοκαλιακούδα φημίζεται για τις εναέριες «καταδύσεις» και τους επιδέξιους ελιγμούς της που, πολλές φορές, συνοδεύονται από ακροβατικές κινήσεις. Έχει την ικανότητα να εκτελεί κάθετη εφόρμηση μέχρι 100 χλμ/ώρα, με διπλωμένες τις πτέρυγες, ή ανάποδη πτήση με περιστροφή του σώματος γύρω από τον εαυτό της και άρθρωση χαρακτηριστικής στριγγής κραυγής. Επίσης, είναι από τα λίγα πτηνά που μπορούν να κερδίζουν ύψος εντελώς κάθετα προς την επιφάνεια του εδάφους. Τα ακροβατικά αυτά έχουν, πολύ εύστοχα, παρομοιαστεί με εκείνα που εκτελούν οι πιλότοι των παλαιών διπλάνων.[29]

Γενικά, η κοκκινοκαλιακούδα θεωρείται αρκετά προσιτή και δεν φαίνεται ιδιαίτερα δειλό πτηνό, ενώ είναι κοινωνικό είδος σχηματίζοντας μικρές αγέλες,[27] εκτός από την περίοδο αναπαραγωγής.[29] Αυτό μπορεί να συμβεί καθ’ όλη τη διάρκεια του έτους, αλλά κυρίως στην Ευρώπη το Σεπτέμβριο και τον Οκτώβριο, όταν τα νεαρά πτηνά ενταχθούν στο κοπάδι. Ωστόσο, στο Νεπάλ και στην ευρύτερη περιοχή των Ιμαλαΐων, μπορεί να σχηματίζει κοπάδια που αριθμούν εκατοντάδες άτομα.[22] Συχνά, κινεί νευρικά τις πτέρυγες και την ουρά της, όταν αρθρώνει διάφορα καλέσματα εν στάσει. Αντίθετα με άλλα κορακοειδή, δεν ανεβαίνει σχεδόν ποτέ σε δένδρα ή θάμνους, προτιμώντας το έδαφος, όπου είναι πολύ «νευρική» και κινητική, μετακινούμενη με βάδισμα, τρέξιμο ή μικρά τριπλά άλματα.[39][48]

Οι κοκκινοκαλιακούδες είναι σε θέση να αναπαράγονται από την ηλικία των τριών ετών αν και η ηλικία της πρώτης αναπαραγωγής είναι μεγαλύτερη στους μεγάλους πληθυσμούς.[49] Η ωοτοκία πραγματοποιείται άπαξ κάθε χρόνο, από τα τέλη Απριλίου μέχρι τις αρχές Μαΐου, αλλά κάποιες φορές υπάρχει και δεύτερη ωοτοκία, μόνον όμως σε περίπτωση που χαθεί η πρώτη.[50] Τα ζευγάρια εμφανίζουν ισχυρό δεσμό, από τη στιγμή που είναι επιτυχής η πρώτη ωοτοκία.[51] Φωλιάζει μοναχικά, αλλά μπορεί να σχηματίζει μικρές αποικίες, μερικές φορές μαζί με την κιτρινοκαλιακούδα, ιδιαίτερα όταν οι καλές θέσεις είναι περιορισμένες.[29]

Η ογκώδης φωλιά αποτελείται από ρίζες και βλαστούς από ρείκια, αγκαθωτά ψυχανθή (Ulex sp. ) ή άλλα φυτά και είναι επενδεδυμένη με μαλλί ή τρίχες.[23] Στην Κ. Ασία, μάλιστα, οι τρίχες μπορούν να αποκόπτονται από το τρίχωμα των οικόσιτων θηλαστικών, όπως του Hemitragus jemlahicus.[41] Η φωλιά είναι κατασκευασμένη σε μια σπηλιά ή σχισμή, σε βράχο ή ορθοπλαγιά, μερικές φορές σε λαγούμια άλλων ζώων, σε ορεινές τοποθεσίες αλλά και κοντά στην ακτή, ανάλογα με τον οικότοπο του πτηνού.[23][50] Εάν το πέτρωμα είναι μαλακός ψαμμίτης, τα πουλιά μπορούν να σκάβουν τρύπες σχεδόν μέχρι ένα (1) μέτρο βάθος.[52] Επίσης, μπορούν να χρησιμοποιηθούν παλαιά κτήρια, ενώ τα μοναστήρια στο Θιβέτ αποτελούν πολλές φορές χώρους φωλιάσματος, όπως και σύγχρονα κτήρια στις πόλεις της Μογγολίας, συμπεριλαμβανομένης της πρωτεύουσας Ουλάν Μπατόρ.[9] Δυνατόν να χρησιμοποιούνται και άλλες «τεχνητές» θέσεις, όπως λατομεία και ορυχεία, όπου αυτά είναι διαθέσιμα.[53] Η φωλιά κατασκευάζεται και από τους δύο εταίρους, σε 2-4 εβδομάδες.[50]

Η γέννα αποτελείται συνήθως από 3-4 αβγά (σπανίως 2 ή μέχρι 7),[54] διαμέτρου 40,6Χ28,7 χιλιοστών και βάρους 15,7 γραμμαρίων, περίπου, εκ των οποίων το 6% είναι κέλυφος.[54][55] Το μέγεθος των αβγών είναι ανεξάρτητο από το μέγεθος της ωοτοκίας και την θέση της φωλιάς, αλλά μπορεί να ποικίλλει μεταξύ των διαφορετικών θηλυκών.[56]

Η επώαση αρχίζει μετά την εναπόθεση του 1ου αβγού, πραγματοποιείται μόνον από το θηλυκό, ενώ το αρσενικό την εφοδιάζει με τροφή, διαρκεί δε 17-23 ημέρες -συνήθως 18 με 19- , περίπου.[37][54] Οι νεοσσοί είναι φωλεόφιλοι, γεννιούνται δηλαδή ανήμποροι και χρειάζονται για καιρό την προστασία των γονέων τους, σε αντίθεση με εκείνους της κιτρινοκαλιακούδας, που διαθέτουν ήδη ένα πυκνό κάλυμμα από υποτυπώδεις τρίχες.[57] Τη σίτισή τους αναλαμβάνει το θηλυκό για 2-3 εβδομάδες, με τροφή που φέρνει το αρσενικό. Αφήνουν τη φωλιά στις 38 ημέρες, περίπου, αλλά παραμένουν κοντά στους γονείς του για 3-4 εβδομάδες ακόμη.[54]

Τα νεαρά άτομα επιζούν σε ποσοστό 43% μέχρι το 1ο έτος ζωής τους, και ο ετήσιος ρυθμός επιβίωσης των ενηλίκων είναι περίπου 80%. Η μέση διάρκεια ζωής κυμαίνεται, περίπου, στα 7 χρόνια,[58] αν και έχει καταγραφεί ηλικία 17 ετών.[45] Η θερμοκρασία και η βροχόπτωση κατά τους μήνες που προηγούνται της αναπαραγωγής, φαίνεται να σχετίζονται με τον αριθμό των νεοσσών που αποκτούν το πρώτο πτέρωμα κάθε χρόνο, καθώς και με το ποσοστό επιβίωσής τους. Οι νεοσσοί που αναπτύσσουν το πρώτο πτέρωμα υπό καλές συνθήκες, είναι πιο πιθανό να επιβιώσουν μέχρι την ηλικία αναπαραγωγής και, έχουν μπροστά τους περισσότερα έτη για να αναπαραχθούν, σε σχέση με εκείνους που ανέπτυξαν το πρώτο πτέρωμα υπό κακές συνθήκες.[49]

Οι κυριότεροι φυσικοί θηρευτές της κοκκινοκαλιακούδας είναι ο πετρίτης, ο χρυσαετός και ο μπούφος, ενώ την φωλιά της λεηλατεί συχνά το κοράκι.[59]"Release Update December 2003" (PDF). Operation Chough. Retrieved June 2014[60][61] Επίσης, η κοκκινοκαλιακούδα αποτελεί ένα από τα είδη-ξενιστές πάνω στα οποία παρασιτεί ο κισσόκουκος (Clamator glandarius).[62]

Πολλά άτομα μπορούν επίσης να φέρουν ακάρεα, αλλά μια μελέτη που έγινε για το άκαρι Gabucinia delibata, που παρασιτεί στο πτέρωμα των νεαρών πτηνών, λίγους μήνες μετά την ανάπτυξη του πρώτου φτερώματος όταν ενταχθούν στις αποικίες, έδειξε ότι το συγκεκριμένο παράσιτο βελτιώνει στην πραγματικότητα την σωματική κατάσταση του ξενιστή του. Είναι πιθανό ότι τα ακάρεα ενισχύουν την φυσιολογική υγιεινή του πτερώματος αποτρέποντας την ανάπτυξη παθογόνων παραγόντων.[44] Ταυτόχρονα ενισχύει τα άλλα «μέτρα προστασίας» του πτερώματος, όπως είναι η ηλιοθεραπεία και η τριβή του πτερώματος με μυρμήκια (sic!), των οποίων το –τοξικό- μυρμηκικό οξύ θανατώνει τους παθογόνους μικροοργανισμούς.[9]

Tο είδος, συνολικά, δεν θεωρείται ότι προσεγγίζει τα κατώτατα όρια του κριτηρίου μείωσης για τον παγκόσμιο πληθυσμό της IUCN Red List (δηλαδή, μείωση κατά περισσότερο από 30%, μέσα σε δέκα χρόνια ή τρεις γενεές), και ως εκ τούτου αξιολογείται ως Ελαχίστης Ανησυχίας (LC).[21]

Ωστόσο, οι ευρωπαϊκές επικράτειες έχουν μειωθεί και κατακερματιστεί λόγω της απωλείας των παραδοσιακών μεθόδων κτηνοτροφίας, της δίωξης και, ίσως, όχλησης στην αναπαραγωγή και το φώλιασμα, αν και οι αριθμοί στη Γαλλία, τη Μεγάλη Βρετανία και τη Ιρλανδία μπορεί τώρα να έχουν σταθεροποιηθεί.[23] Από τους άλλους ευρωπαϊκούς πληθυσμούς μόνο στην Ισπανία το είδος εξακολουθεί να είναι διαδεδομένο. Στις άλλες περιοχές αναπαραγωγής οι επικράτειες είναι αποσπασματικές και μεμονωμένες, γι’ αυτό και το είδος έχει χαρακτηριστεί ως Ευάλωτο (VU) στην Ευρώπη. Γι’ αυτό, σε πολλές ευρωπαϊκές χώρες, η κοκκινοκαλιακούδα αποτελεί το αντικείμενο πολλών προγραμμάτων διατήρησης και προστασίας.

Μια μικρή ομάδα από άγριες κοκκινοκαλιακούδες έφτασε από την ηπειρωτική Ευρώπη στην Κορνουάλη, το 2001 και, μάλιστα, φώλιασε μέσα στο επόμενο έτος. Αυτή ήταν η πρώτη καταγραφή αναπαραγωγής του είδους στη Βρετανία, από το 1947, και μια σταδιακή αύξηση του πληθυσμού έχει παρατηρηθεί έκτοτε, κάθε επόμενο έτος.[63]

Τους μεγαλύτερους καταγεγραμμένους αναπαραγωγικούς πληθυσμούς στην Ευρώπη, διαθέτουν η Ρωσία, η Ισπανία, η Ιταλία, η Γαλλία και η Ελλάδα.[64]

Το πτηνό αναφέρεται ήδη στον Αριστοτέλη και τον Αριστοφάνη με γλαφυρό τρόπο, που σημαίνει ότι ήταν πολύ γνωστό στην αρχαία Ελλάδα, και το χρησιμοποιούσαν ως βασικό θέμα για τα γνωμικά και τις παροιμίες τους. Βέβαια, δεν είναι καθορισμένο ποιο από τα δύο είδη εννοούσαν στις αναφορές τους, αυτό όμως, έχει μικρή σημασία διότι μοιάζουν μεταξύ τους.

Στην ελληνική μυθολογία, η κοκκινοκαλιακούδα, επίσης γνωστή ως «κοράκι της θάλασσας», θεωρείτο ιερό πτηνό του Κρόνου και κατοίκησε στο «ευλογημένο νησί» της Καλυψούς.[66]

Στο Ηνωμένο Βασίλειο, η κοκκινοκαλιακούδα συνδέεται από τα αρχαία χρόνια με την Κορνουάλη, και εμφανίζεται στον θυρεό της.[67] Σύμφωνα με τον μύθο, ο Βασιλιάς Αρθούρος δεν πέθανε μετά την τελευταία του μάχη, αλλά η ψυχή του «μετανάστευσε» στο σώμα μιας κοκκινοκαλιακούδας και, το κόκκινο χρώμα του ράμφους και των ποδιών του πτηνού, προέρχονται από το αίμα αυτής της τελευταίας μάχης.[68] Γι’ αυτό, ήταν γρουσουζιά να σκοτώνει κάποιος μια κοκκινοκαλιακούδα,[66] ενώ η παράδοση υποστηρίζει, επίσης, ότι μετά την τελευταία αναχώρηση από την Κορνουάλη, τότε η επιστροφή της, θα σηματοδοτήσει την επιστροφή του Βασιλιά Αρθούρου.[69]

Στην εραλδική, απεικονίζεται στο οικόσημο του Τόμας Μπέκετ (Thomas Becket), Αρχιεπισκόπου του Κάντερμπερι, αλλά και την πόλη του Κάντερμπερι, λόγω της σύνδεσής του με αυτόν.[70]

Στον ελλαδικό χώρο η Κοκκινοκαλιακούδα απαντά και με την ονομασία Κορωνοπούλι (Ταΰγετος) [71] Άλλες λόγιες ονομασίες είναι: Πυρροκόραξ ο ερυθρόραμφος, Πυρροκόραξ ο γνήσιος, Κορώνη η ειναλία [71]

i. ^ Η λόγια ονομασία του είδους «ερυθρόραμφος» [71] είναι τεχνητή και δεν αντιστοιχεί στην λατινική «pyrrhocorax», ωστόσο χρησιμοποιείται κατ’ αντιστοιχίαν της απόδοσης «κιτρινόραμφος», για τη συγγενική κιτρινοκαλιακούδα (βλ. Ονοματολογία)

Η Κοκκινοκαλιακούδα είναι πτηνό της οικογενείας των Κορακιδών, που απαντά κυρίως στην κεντρική Ασία, αλλά και σε απομονωμένους πληθυσμούς σε μέρη της Ευρώπης (και στον ελλαδικό χώρο) και της βόρειας Αφρικής. Η επιστημονική ονομασία του είδους είναι Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax και περιλαμβάνει 8 υποείδη.

Στην Ελλάδα απαντά το υποείδος Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax docilis (S. G. Gmelin, 1774).

Είναι είδος προσαρμοσμένο να ζει σε μεγάλα υψόμετρα, μικρότερα πάντως από εκείνα της συγγενικής κιτρινοκαλιακούδας.

КъуанщӀэпэплъ (лат-бз. Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax) — вынд теплъэ лъэпкъым щыщ лӀэужьыгъуэщ.

Къуалэм хуэдизынщ, къешэч г. 270-370. Теплъэр фӀыцӀэ-лыдщ, дамэхэмрэ кӀэмрэ удзыфэ къащӀоуэ. И пэ псыгъуэ кӀыхь мащӀэу гъэшамрэ лъакъуэхэмрэ плъыжь-лыдщ.

Еуропэм, Азиэм, Африкэм я къущхьэхэм щопсэу. Лъэтэжкъым. Гуп-гупурэ абгъуэ щащӀ къыр нэӀухэм, нэпкъ задэхэм. Къаукъазым и къущхьэ щӀыпӀэхэм мылъэтэжу куэду щопсэу.

Яшх хьэпщхупщ, хьэмблу, къэкӀыгъэ жылэ.

Црвеноклуната галица (науч. Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax) е врапчевидна птица од фамилијата на враните (Corvidae), еден од двата вида на родот галици (Pyrrhocorax). Нејзините осум подвида се размножуваат низ планините и крајбрежните грбени од западниот брег на Ирска и Велика Британија, на исток низ јужна Европа и северна Африка до централна Азија, Индија и Кина. Оваа птица порано била распространета и низ Македонија, но сега кај нас повеќе не се размножува.

Таа има сјајни црни пердуви и долг надолу свиен црвен клун, црвени нозе и гласен, ѕвонлив повик. Лета со лебдење и раширени примарни пердуви на крилјата. Се спарува за цел живот и живее на истата територија.

Црвеноклуната галица за првпат беше опишана од Linnaeus во неговата Систем на природата, 1758 како Upupa pyrrhocorax.[2] Преместена е во сегашниот род галици (Pyrrhocorax), од Мармадјук Тунстал (Marmaduke Tunstall), 1771 во неговата Орнитологија Британика.[3] Името на родот потекнува од грчкото πύρρος (purrhos) - „со боја на оган“ и κόραξ (korax)- „гавран“.[4] Единствен втор член на родот е жолтоклуната галица (Pyrrhocorax graculus).[5]

Има осум подвида, иако разликите меѓу нив се многу мали:[6]

Црвеноклуната галица е долга 39-40 см, има распон на крилјата 73-90 см и тежи околу 310 грама.[4] Перјето ѝ е кадифеноцрно со зеленкав сјај и има долг црвен, надолу свиен клун и црвени нозе. Половите се исти, но младенчињата имаат портокалов клун и розови нозе, до првата есен и понесјајни пердуви.[6]

Повикот ѝ е силен, ѕвонлив чии-оу.

Црвената галица е постојан жител, не е преселница, а нејзиното живеалиште се високите планини меѓу 2.000 и 2.500 метри надморска височина во северна Африка, 2.400-3.000 на Хималаите, а се лете се среќава на височина од 6.000 па дури и до 7.950 метри, на Монт Еверест.[6]

Црвената галица, главно се храни со инсекти, пајаци и други без'рбетници од земјата, а најмногу со мравките кои веројатно се најзначаен дел од исхраната.[6] Во централна Азија стојат на диви или домашни цицачи и се хранат со нивните паразити.[14] Иако без’рбетниците го сочинуваат најголемиот дел од исхраната, сепак, тие јадат и растителна храна, како жито, јачмен и сл. Најчесто се хранат на испасена трева (или искосена).

Црвеноклуната галица сексуалната зрелост ја достигнува на тригодишна возраст и вообичаено има по едно легло годишно. Откако ќе се спарат, остануваат заедно цел живот. Гломазното гнездо го градат во пукнатини на карпи, гребени, или копаат длабока дупка во песок (речиси 1 метар), а понекогаш и на зградите во урбаните средини (во Монголија). Однадвор е направено од груби гранки и корења, а внатре го постилаат со волна или влакна. Несат 3-5 јајца, кремави со кафеави и сиви точки и дамки.

Женката ги инкубира 17–18 дена, а за тоа време мажјакот ја храни. Пилињата ги хранат обата родитела додека да се оперјат за 31-41 ден.[4] Просечниот животен век на овие птици е 7 години,[4] но регистрирана е старост од 17.[15]

Црвеноклуната галица има широка распростанетост на околу 10 милиони км² и популација од 86,000 до 210,000 поединци во Европа и глобално таа не е во опаѓање. Затоа спред Црвениот список на МСЗП е вид со најмала загриженост од исчезнување.[1]

Но, Европската популација опаднала и се фрагментирала поради загубата на традиционалното земјоделство, прогон или уништување на местата за гнездење. На некои места популацијата сега е стабилизирана, а само во Шпанија има широка распространетост. Всушност, во Европа, се смета за ранлив вид.[16]

Во старогрчката митологија, оваа птица, позната како „морска врана“ се сметала за света на титанот Крон кој живеел на Калипсовиот Блажен Остров.[17]

Црвеноклуната галица (науч. Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax) е врапчевидна птица од фамилијата на враните (Corvidae), еден од двата вида на родот галици (Pyrrhocorax). Нејзините осум подвида се размножуваат низ планините и крајбрежните грбени од западниот брег на Ирска и Велика Британија, на исток низ јужна Европа и северна Африка до централна Азија, Индија и Кина. Оваа птица порано била распространета и низ Македонија, но сега кај нас повеќе не се размножува.

Таа има сјајни црни пердуви и долг надолу свиен црвен клун, црвени нозе и гласен, ѕвонлив повик. Лета со лебдење и раширени примарни пердуви на крилјата. Се спарува за цел живот и живее на истата територија.

टुङ्गा (/ˈtʃʌf/ chuff) (Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax) कागको प्रजातिको एक प्रकारको चरा हो । यो चरा नेपाल लगायत दक्षिणी युरोप, उत्तर अफ्रिका तथा मध्य एसियाका राष्ट्रहरूका उच्च हिमाली भूभाग तथा तटिय चट्टानहरूमा पाइने गर्छ ।

टुङ्गा (/ˈtʃʌf/ chuff) (Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax) कागको प्रजातिको एक प्रकारको चरा हो । यो चरा नेपाल लगायत दक्षिणी युरोप, उत्तर अफ्रिका तथा मध्य एसियाका राष्ट्रहरूका उच्च हिमाली भूभाग तथा तटिय चट्टानहरूमा पाइने गर्छ ।

Palores (Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax) yw eghenn a edhen ow kul rann a'n teylu a vrini, Corvidae. Eghenn arall y'n keth bagas yw Pyrrhocorax graculus. Yma'n balores ow triga yn Ynysow Breten Veur, Manow, ha Wordhon warbarth gans powyow Europa dheghow, an Alpow, ha mynydhyow a-dreus kres Asi bys Eynda ha China.

Yn Breten Veur, yma paloresow ow triga yn ugheldiryow hag alsyow howlsedhes Kembra hag Alban, mes yn tiwedhes i re drevesigas yn Kernow arta.[1] Yma'n balores war gota arvow Kernow, hag aswonnys avel edhen genedhlek Kernow yw hi. Yth esa paloresow moy kemmyn nans yw niver a vlydhynyow, mes an chogha (Corvus monedula) re gesstrivas erbynn an balores rag tiredh.

Diwwarr an balores yw kogh; hy fluvennow yw du; ha'y gelvin yw kogh. Yma hi ow tybri hwesker ha miles heb mell keyn. Kri an balores yw galow hir – sort a "kyy-oo" ughel – hag yw moy diblans ages huni an chogha.

An balores a's teves nij neuvelladow hag es.

Neyth an balores yw tew, gonedhys a rug, eythin, po plansow erell, ha linys gans gwlan po blew. Yma tri bys hwegh oy brith, dedhwys mis Ebryl po mis Me.

"An Balores" yw hanow gwari berr gans Robert Morton Nance ynwedh.

The red-billed chough, Cornish chough or simply chough (/ˈtʃʌf/ CHUF; Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax), is a bird in the crow family, one of only two species in the genus Pyrrhocorax. Its eight subspecies breed on mountains and coastal cliffs from the western coasts of Ireland and Britain east through southern Europe and North Africa to Central Asia, India and China.

This bird has glossy black plumage, a long curved red bill, red legs, and a loud, ringing call. It has a buoyant acrobatic flight with widely spread primaries. The red-billed chough pairs for life and displays fidelity to its breeding site, which is usually a cave or crevice in a cliff face. It builds a wool-lined stick nest and lays three eggs. It feeds, often in flocks, on short grazed grassland, taking mainly invertebrate prey.

Although it is subject to predation and parasitism, the main threat to this species is changes in agricultural practices, which have led to population decline, some local extirpation, and range fragmentation in Europe; however, it is not threatened globally. The red-billed chough, which derived its common name from the jackdaw, was formerly associated with fire-raising, and has links with Saint Thomas Becket and Cornwall. The red-billed chough has been depicted on postage stamps of a few countries, including the Isle of Man, with four different stamps, and the Gambia, where the bird does not occur.

The red-billed chough was first described by Carl Linnaeus in his 1758 10th edition of Systema Naturae as Upupa pyrrhocorax.[2] It was moved to its current genus, Pyrrhocorax, by Marmaduke Tunstall in his 1771 Ornithologia Britannica.[3] The genus name is derived from Greek πυρρός (pyrrhos), "flame-coloured", and κόραξ (korax), "raven".[4] The only other member of the genus is the Alpine chough, Pyrrhocorax graculus.[5] The closest relatives of the choughs are the typical crows, Corvus, especially the jackdaws in the subgenus Coloeus.[6]

"Chough" was originally an alternative onomatopoeic name for the jackdaw, Corvus monedula, based on its call. The similar red-billed species, formerly particularly common in Cornwall, became known initially as "Cornish chough" and then just "chough", the name transferring from one species to the other.[7] The Australian white-winged chough, Corcorax melanorhamphos, despite its similar shape and habits, is only distantly related to the true choughs, and is an example of convergent evolution.[8]

There are eight extant subspecies, although differences between them are slight.[9]

There is one known prehistoric form of the red-billed chough. P. p. primigenius, a subspecies that lived in Europe during the last ice age, which was described in 1875 by Alphonse Milne-Edwards from finds in southwest France.[18][19]

Detailed analysis of call similarity suggests that the Asiatic and Ethiopian races diverged from the western subspecies early in evolutionary history, and that Italian red-billed choughs are more closely allied to the North African subspecies than to those of the rest of Europe.[20]

The adult of the "nominate" subspecies of the red-billed chough, P. p. pyrrhocorax, is 39–40 centimetres (15–16 inches) in length, has a 73–90 centimetres (29–35 inches) wingspan,[21] and weighs an average 310 grammes (10.9 oz).[4] Its plumage is velvet-black, green-glossed on the body, and it has a long curved red bill and red legs. The sexes are similar (although adults can be sexed in the hand using a formula involving tarsus length and bill width)[22] but the juvenile has an orange bill and pink legs until its first autumn, and less glossy plumage.[9]

The red-billed chough is unlikely to be confused with any other species of bird. Although the jackdaw and Alpine chough share its range, the jackdaw is smaller and has unglossed grey plumage, and the Alpine chough has a short yellow bill. Even in flight, the two choughs can be distinguished by Alpine's less rectangular wings, and longer, less square-ended tail.[9]

The red-billed chough's loud, ringing chee-ow call is clearer and louder than the similar vocalisation of the jackdaw, and always very different from that of its yellow-billed congener, which has rippling preep and whistled sweeeooo calls.[9] Small subspecies of the red-billed chough have higher frequency calls than larger races, as predicted by the inverse relationship between body size and frequency.[23]

The red-billed chough breeds in Ireland, western Great Britain, the Isle of Man, southern Europe and the Mediterranean basin, the Alps, and in mountainous country across Central Asia, India and China, with two separate populations in the Ethiopian Highlands. It is a non-migratory resident throughout its range.[9]

Its main habitat is high mountains; it is found between 2,000 and 2,500 metres (6,600 and 8,200 ft) in North Africa, and mainly between 2,400 and 3,000 metres (7,900 and 9,800 ft) in the Himalayas. In that mountain range it reaches 6,000 metres (20,000 feet) in the summer, and has been recorded at 7,950 metres (26,080 feet) altitude on Mount Everest.[9] In the British Isles and Brittany it also breeds on coastal sea cliffs, feeding on adjacent short grazed grassland or machair. It was formerly more widespread on coasts but has suffered from the loss of its specialised habitat.[24][25] It tends to breed at a lower elevation than the Alpine chough,[21] that species having a diet better adapted to high altitudes.[26]

The red-billed chough breeds from three years of age, and normally raises only one brood a year,[4] although the age at first breeding is greater in large populations.[27] A pair exhibits strong mate and site fidelity once a bond is established.[28] The bulky nest is composed of roots and stems of heather, furze or other plants, and is lined with wool or hair;[21] in central Asia, the hair may be taken from live Himalayan tahr. The nest is constructed in a cave or similar fissure in a crag or cliff face.[21] In soft sandstone, the birds themselves excavate holes nearly a metre deep.[29] Old buildings may be used, and in Tibet working monasteries provide sites, as occasionally do modern buildings in Mongolian towns, including Ulaanbaatar.[9] The red-billed chough will utilise other artificial sites, such as quarries and mineshafts for nesting where they are available.[30]

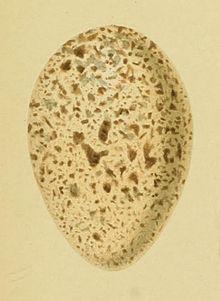

The chough lays three to five eggs 3.9 by 2.8 centimetres (1.5 by 1.1 inches) in size and weighing 15.7 grammes (0.55 oz), of which 6% is shell.[4] They are spotted, not always densely, in various shades of brown and grey on a creamy or slightly tinted ground.[21]

The egg size is independent of the clutch size and the nest site, but may vary between different females.[31] The female incubates for 17–18 days before the altricial downy chicks are hatched, and is fed at the nest by the male. The female broods the newly hatched chicks for around ten days,[32] and then both parents share feeding and nest sanitation duties. The chicks fledge 31–41 days after hatching.[4]

Juveniles have a 43% chance of surviving their first year, and the annual survival rate of adults is about 80%. Choughs generally have a lifespan of about seven years,[4] although an age of 17 years has been recorded.[28] The temperature and rainfall in the months preceding breeding correlates with the number of young fledging each year and their survival rate. Chicks fledging under good conditions are more likely to survive to breeding age, and have longer breeding lives than those fledging under poor conditions.[27]

The red-billed chough's food consists largely of insects, spiders and other invertebrates taken from the ground, with ants probably being the most significant item.[9] The Central Asian subspecies P. p. centralis will perch on the backs of wild or domesticated mammals to feed on parasites. Although invertebrates make up most of the chough's diet, it will eat vegetable matter including fallen grain, and in the Himalayas has been reported as damaging barley crops by breaking off the ripening heads to extract the corn.[9] In the Himalayas, they form large flocks in winter.[33]

The preferred feeding habitat is short grass produced by grazing, for example by sheep and rabbits, the numbers of which are linked to the chough's breeding success. Suitable feeding areas can also arise where plant growth is hindered by exposure to coastal salt spray or poor soils.[34][35] It will use its long curved bill to pick ants, dung beetles and emerging flies off the surface, or to dig for grubs and other invertebrates. The typical excavation depth of 2–3 cm (3⁄4–1+1⁄4 in) reflects the thin soils which it feeds on, and the depths at which many invertebrates occur, but it may dig to 10–20 cm (4–8 in) in appropriate conditions.[36][37]

Where the two chough species occur together, there is only limited competition for food. An Italian study showed that the vegetable part of the winter diet for the red-billed chough was almost exclusively Gagea bulbs, whilst the Alpine chough took berries and hips. In June, red-billed choughs fed on Lepidoptera larvae whereas Alpine choughs ate cranefly pupae. Later in the summer, the Alpine chough mainly consumed grasshoppers, whilst the red-billed chough added cranefly pupae, fly larvae and beetles to its diet.[26] Both choughs will hide food in cracks and fissures, concealing the cache with a few pebbles.[38]

The red-billed chough's predators include the peregrine falcon, golden eagle and Eurasian eagle-owl, while the common raven will take nestlings.[39][40][41][42] In northern Spain, red-billed choughs preferentially nest near lesser kestrel colonies. This small insectivorous falcon is better at detecting a predator and more vigorous in defence than its corvid neighbours. The breeding success of the red-billed chough in the vicinity of the kestrels was found to be much higher than that of birds elsewhere, with a lower percentage of nest failures (16% near the falcon, 65% elsewhere).[42]

This species is occasionally parasitised by the great spotted cuckoo, a brood parasite for which the Eurasian magpie is the primary host.[43] Red-billed choughs can acquire blood parasites such as Plasmodium, but a study in Spain showed that the prevalence was less than one percent, and unlikely to affect the life history and conservation of this species.[44] These low levels of parasitism contrast with a much higher prevalence in some other passerine groups; for example a study of thrushes in Russia showed that all the fieldfares, redwings and song thrushes sampled carried haematozoans, particularly Haemoproteus and Trypanosoma.[45]

Red-billed choughs can also carry mites, but a study of the feather mite Gabucinia delibata, acquired by young birds a few months after fledging when they join communal roosts, suggested that this parasite actually improved the body condition of its host. It is possible that the feather mites enhance feather cleaning and deter pathogens,[46] and may complement other feather care measures such as sunbathing, and anting—rubbing the plumage with ants (the formic acid from the insects deters parasites).[9]

The red-billed chough has an extensive range, estimated at ten million square kilometres (four million square miles), and a large population, including an estimated 86,000 to 210,000 individuals in Europe. Over its range as a whole, the species is not believed to approach the thresholds for the global population decline criterion of the IUCN Red List (i.e., declining more than 30% in ten years or three generations), and is therefore evaluated as least concern.[1]

However, the European range has declined and fragmented due to the loss of traditional pastoral farming, persecution and perhaps disturbance at breeding and nesting sites, although the numbers in France, Great Britain and Ireland may now have stabilised.[21] The European breeding population is between 12,265 and 17,370 pairs, but only in Spain is the species still widespread. Since in the rest of the continent breeding areas are fragmented and isolated, the red-billed chough has been categorised as "vulnerable" in Europe.[30]

In Spain the red-billed chough has recently expanded its range by utilising old buildings, with 1,175 breeding pairs in a 9,716-square-kilometre (3,751 sq mi) study area. These new breeding areas usually surround the original montane core areas. However, the populations with nest sites on buildings are threatened by human disturbance, persecution and the loss of old buildings.[47] Fossils of both chough species were found in the mountains of the Canary Islands. The local extinction of the Alpine chough and the reduced range of red-billed chough in the islands may have been due to climate change or human activity.[48]

A small group of wild red-billed chough arrived naturally in Cornwall in 2001, and nested in the following year. This was the first English breeding record since 1947, and a slowly expanding population has bred every subsequent year.[25]

In Jersey, the Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust, in partnership with the States of Jersey and the National Trust for Jersey began a project in 2010, aimed at restoring selected areas of Jersey's coastline with the intention of returning those birds that had become locally extinct. The red-billed chough was chosen as a flagship species for this project, having been absent from Jersey since around 1900. Durrell initially received two pairs of choughs from Paradise Park in Cornwall and began a captive breeding programme.[49] In 2013, juveniles were released onto the north coast of Jersey using soft-release methods developed at Durrell. Over the next five years, small cohorts of captive-bred choughs were released, monitored, and provided supplemental food.[50]

In Greek mythology, the red-billed chough, also known as 'sea-crow', was considered sacred to the Titan Cronus and dwelt on Ogygia, Calypso's 'Blessed Island',[51] where "The birds of broadest wing their mansions form/The chough, the sea-mew, the loquacious crow."[52]