fr

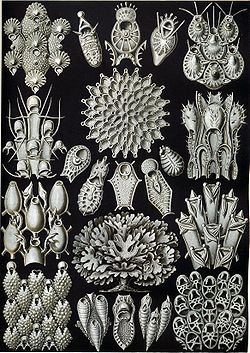

noms dans le fil d’Ariane

One could easily miss the bryozoans (entoprocts) or mistake them as an alga or coral. Bryozoans are a phylum of microscopic, aquatic invertebrates that live in sessile colonies of genetically identical members. The individuals are not autonomous and are termed zooids. They grow as calcified or gelatinous encrusting masses or branching tree-like structures. Having said that, there are notable exceptions, including a genus of solitary species (Monobryozoon), a mobile species (Cristatella mucedo), and a recently found planktonic species (in genus Alcyonidium) that floats as a ball (Peck et al. 1995). Like the phoronids and the brachiopods they feed using a specialized horseshoe-shaped structure called a lophophore. Known also as “moss animals,” there are somewhere between 4000-6000 living species, some estimate that number closer to 8000 species (Ryland 2005). Most bryozans are marine or brackish, fewer than 100 species live in freshwater (Massard and Geimer 2007). About 15,000 fossil species have been found, dating from the early Ordovician/late Cambrian. Molecular phylogenetic analyses indicate that bryozoans originated earlier in the Cambrian period (along with almost all other invertebrate phyla) and that the earliest bryozoans were non-calcified, thus did not fossilize (Fuchs et al. 2009).

Marine bryozoans are bountiful world wide, especially in tropic zones, but are found in all latitudes and depths, even in the cold waters of Antarctica (Brusca and Brusca 2003; Kozloff 1990).

The bryozoans are divided into three very distinct monophyletic classes (Fuchs et al. 2009). Members of the class Phylactolaemata are entirely freshwater species; the Stenolaemata are exclusively marine, and Gymnolaemata, the largest class, containing 75% of living bryozoan species, is primarily marine, although some species inhabit brackish water (Brusca and Brusca 2003; Kozloff 1990).

The fertilized egges in some bryozoans in the class Stenolaemata divide so that up to one hundred identical eggs are brooded at a time in specialized zooids. There is great diversity in the types of bryozoan larva, some feed, some are flattened, some have a shell, some are zooid-like, but all form a ciliated, free-swimming larva for some length of time, then settle and undergo dramatic reorganization to reach their mature form.

A bryozoan colony begins with an ancestrula (the primary zooid), which is formed sexually. The colony then grows by asexual budding, in a pattern dictated by the particular taxon. Bryozoan colonies are found in a wide array of colony formations. Encrusting forms (most common) can cover large areas of rocks, algae, shells or exoskeletons of other invertebrates, ship hulls, and other hard substrates. Other forms include arboristic, branching, discus, amorphous blob shapes or (especially in freshwater taxa) the zooids can grow as buds along a cord-like stolon. There is one genus of mobile bryozoans, Cristatella, which, in the shape of a caterpillar, crawls along substrates at very slow speed! Some freshwater taxa also form new colonies by asexually producing statoblasts, which drop to the bottom if the parent colony does not survive and survive harsh conditions in a dormant mode. The statoblast then generates a new zooid when conditions are more optimal. (Brusca and Brusca 2003; Kozloff 1990)

The individual zooid each live in a box shaped or bud-shaped exoskeleton (zoecium) which can be mineralized, gelatinous or chitinous, and in some taxa may have an operculum over its little opening at the top. Typically suspension feeders, the zooid protracts through this opening a special feathery feeding organ called the lophophore, which is composed of a circle or horseshoe of tentacles. Cilia on the lophophore tentacles create water currents to carry appropriate sized food particles (including protists and invertebrate larvae) along food grooves on the lophophore which lead to the mouth.

Within a colony, individual zooids may be more or less connected to one another; many taxa have pores or a cord (funiculus) linking individuals in a colony, through which the individuals share coelomic fluids. In some kinds of colonies zooids function together to create more powerful water currents to bring in more food. All colonies contain autozooids, which feed and excrete wastes, some colonies also have non-feeding heterozooids, individuals specialized for gamete production, protection, or other functions and are supported with nutrients shared by surrounding zooids. Zooids may have spines on their zoecium, some that produce toxins, to ward off predators. Protective zooids may have their operculum modified into a protective structure, either an avicularium – a movable beak-like structure to rid the colony of pests, or a vibraculum – a long, movable setae-like structure thought to help in cleaning off the colony. Grazing by nudibranchs, snails, sea urchins and crustaceans is a common threat to bryozoans (Brusca and Brusca 2003; Kozloff 1990).

Bryozoans do not have nephridia or a circulatory system, instead gas exchange and nitrogenous excretions occurs passively by diffusion in the tiny zooids. When more complex wastes build up, the zooid forms a “brown body”, in which the soft tissue and lophophore (together called the polypide) degenerate within their casing (called the cystid). The cystid can then regenerate a new polypide, with the old brown body in its gut. The brown body in some taxa is then excreted through the anus (located near the mouth, but on the outside of the lophophore). In taxa with zooids arranged on stolons, the brown body simply falls off the shoot and a new zooid is regenerated. The nervous system in bryozoans is minimal, including a ganglion, nerve ring around the pharynx, and nerve net that extends into the tentacles and vicera. Sensory structures are limited to tactile cells on the lophophore (Brusca and Brusca 2003; Kozloff 1990).

Bryozoans are generally hermaphroditic. Rather than having discrete gonads, transient germ tissues on the zooid’s body wall peritoneum or on the funiculus (which connects the gut to the body wall) produce gametes. While sperm is spawned through pores in lophophore tentacles, eggs are usually harbored inside the body wall, and are internally fertilized by sperm, coming in on lophophore feeding currents (Brusca and Brusca 2003; Kozloff 1990).

Individual bryozoan zooids are typically about 0.5 mm long. The colonies can reach sizes up to a meter across (Brusca and Brusca 2003).

The distinct lophophore organ of the bryozoans is also found in the brachiopods and phoronids, and these three phyla have long been associated as close relatives. However recent phylogenetic work now places the bryozoans quite distinct from the brachiopods and phoronids, as a more basal group in the containing superphylum Lophotrochozoa (Halanych 2004).

Briozoylar (lat. Ectoprocta və ya Bryozoa) — İlkağızlılar yarımbölməsindən onurğasız heyvan tipi.

Hazırda 4000 növü məlumdur, onlardan Xəzər dənizində 6 növ qeyd edilmişdir. Bowerbankia imbricata, Bowerbankia grasilis, Paludicella articulata, Victorella pavida Xəzərdə geniş yayılmışlar. Conopeum seurati Xəzər dənizinə 1958-ci ildə Azov dənizindən gəlmişdir. Hazırda bioloji örtüklərin əmələ gəlməsində mühüm rol oynayır.

Ectoprocta (Nitsche, 1869)

Briozoylar oturaq həyat tərzi keçirən dəniz heyvanları olub, nadir hallarda şirin sularda rast gəlinir. Briozoylar koloniya halında yaşayırlar, onların koloniyaları hidroid və mərcan poliplərinin əmələ gətirdikləri koloniyaları xatırladır. Koloniyalar bir neçə on santimetrlə ölçülür , koloniyanı təşkil edən hər bir fərdin ölçüsü isə 1mm- dən böyük olmur. Briozoy koloniyaları şaxəli budaq, yarpaq dəstəsi , bəzən bir müstəvi üzərində yerləşən lövhə şəklində olur. Koloniyalar polimerf və monomorf tipdə olur. Dənizdə yaşayan növlər hər iki tipdə , şirin su formaları isə yalnız monomorf olur. Monomorf koloniyadakı fərdlər quruluşca oxşar olub , eyni funksiya yerinə yetirirlər. Polimorf koloniyanın üzvləri həm quruluşuna , həm də yerinə yetirdikləri funksiyaya görə fərqlənirlər. Polimorf koloniyada bir qrup fərdlər ayırd edilir. Birinci qrup – adi fərdlər olub, lofofora , çıxıntılar tacına , cinsi məhsullar, hazırlayan sadə quruluşlu bağırsağa malikdir. Belə fərdlər koloniyada sayca üstünlük təşkil edir. Onlar qidanın tutulmasında , həzm edilməsində , mənimsənilməsində iştirak edir və bütün koloniyanı qidalandırır . Bununla əlaqədar olaraq, belə fərdlər qidalandırıcı və ya adi fərdlər adlanır. Çox vaxt bu fərdlərin üzərində və yanında oetsiya adlanan xüsusi fərdlər əmələ gəlir. Onlar yumurta hüceyrələrinin inkişaf etdiyi rüşeym kamerasına malik olurlar. İkinci qrup fərdlərin bir qismi substrata yapışmağa xidmət edir, bir qismi isə müdafiə funksiya daşıyır, koloniyanı kiçik qurdlardan , xərçənglərdən , və digər kiçik yırtıcılardan qoruyur.Belə fərdlərin arasında avikulyarilər adlanan «quş başı»na oxşar fərdlər yerləşir. Onların çıxıntıları olmadığına görə sərbəst qidalana bilmirlər, adi fərdlərin hesabına qidalanırlar. Avikulyarilərdə «alt çənəyə» oxşar törəmə inkişaf edir ki, xüsusi əzələlərin yığılması nəticəsində bu törəmə qapana bilir. Avikulyarilərin belə uyğunlaşma qabiliyyəti koloniyanı düşmənlərin təqibindən müdafiə edir. Koloniyada nadir hallarda vibrakulyarilər adlanan, müdafiə funksiyası daşıyan fərdlər olur. Vibrakulyarilərdə uzun hərəkətli qamçılar inkişaf edir ki, bunlar xüsusi əzələlərin köməyi ilə titrəyərək düşmənlərini koloniyaya yaxınlaşmağa qoymur. Avikulyarilərdə və vibrakulyarilərdə olan xüsusi hissedici törəmələr sinir sistemi ilə əlaqəlidir və düşmənin yaxınlaşmasını xəbər verir. Koloniya aktiv müdafiə edən belə fərdlərdən əlavə, əksər formaların xarici divarında passiv müdafiə orqan olan müxtəlif çıxıntılar – tikancıqlar inkişaf edir. Bir sıra formalarda bu çıxıntılar bütün koloniyanı əhatə edərək, onu tikanlı edir və düşmənlərini qorxudur. Sibir dənizlərində yayılan Uschakovia gorbunovi növündə bütün koloniya uzun tikanlı çıxıntılarla örtülmüşdür və bu da onu düşmənlərin təqibindən mühafizə edir. Bu növə 700m-ə qədər dərinlikdə , -0,9º -1,4ºC temperaturda rast gəlinir. Bu növün digər maraqlı cəhəti odur ki, koloniyanın aşağı hissəsində çıxıntılarda məhrum , cinsi məhsullar əmələ gətirməyən fərdlər yerləşir. Bu fərdlərin yuvacıqlarında ağ dənəvər kütlə toplanır. Bu özünəməxsus yuvacıqlar koloniyadakı fərdlərin şəkildəyişməsində əmələ gəlib, mürəkkəb koloniyanın böyüməsi üçün lazım olan ehtiyat qida maddələri saxlayır. Şirinsu briozoy koloniyaları az rəngarəngdir. Onlar suyun dibindəki əşyalarda , su bitkilərində budaqlanmış nazik boru şəklində yerləşirlər. Əksər hallarda sualtı əşyalarda – daşlarda, batmış ağac kötüklərində , bitkilərdə , bəzən heyvanlarda – molyusklarda, xərçənglərdə iri həcimli koloniyalar əmələ gətirirlər. Briozoy koloniyaları çoxlu kiçik fərdlərdən ibarət olur . Məsələn, Flustra foliacea koloniyasının 1 q kütləsində 1330 –a qədər fərd olur . Hər bir fərd geniş boşluğu olan ayrı-ayrı yuvacıqlarda yerləşir və zooid adlanır. Zooidin bədəni polipid adlanan ön, sistid adlnan dal hissədən ibarətdir. Sistid hissə xarici epitelinin törətdiyi kutikula qatı ilə əhatə olunmuşdur. Polipid hissə zərifdir və qalın kutikula qatından məhrumdur. Bu hissədə uzun çıxıntılarla əhatə olunmuş ağız dəliyi yerləşir. Ağız örtüyü briozoylarda dilşəkilli kiçik ağızönü pərlə və ya epistomla qapanır. Çılpaqağızlı briozoylarda isə ağız açıq olur. Çıxıntılar lotofor adlanan əsası nal şəklində olan pərin üzərində oturur . Çıxıntıların üzəri kirpikli epiteli hüceyrələri ilə örtülüdür . Polipid hissə çıxıntılarla birlikdə sistid hissənin içərisinə doğru tam çəkilə bilir. Bu çəkilmə iki əzələnin – retraktorun köməyi ilə baş verir . Retraktor bağırsağın yan tərəflərində yerləşərək , ön uca ilə polipid hissənin divarında ,dal ucu ilə sistidin əsasına birləşir. Briozoylar ikinci bədən boşluğuna - seloma malik heyvanlardır.Selom nazik arakəsmələrlə üç şöbəyə ayrılır: ön şöbə kiçik ölçülü olub, epistomda yerləşir . Bədən boşluğunun orta şöbəsini udlağı əhatə edən həlqəvi kanal təşkil edir və kor şaxələrlə çıxıntıların içərisinə daxil olur . Nisbətən böyük ölçülü arxa şöbə bütün bədəni tutaraq , gövdə selomu adlanır. Bir çox briozoylarda epistom selomla birlikdə reduksiya olunur .

Briozoylar qidasını təşkil edən detrit və ibtidai orqanizmləri çıxıntıların üzərində olan kirpikli hüceyrələrin titrək hərəkəti ilə ağıza doğru qovurlar . Ağıza düşmüş qida qısa udlağa , sonra isə uzun qida borusuna keçir. Briozoyların həzm sistemi ön, orta və dal şöbədən ibarətdir. Ön şöbəni – ağız, udlaq , qida borusu , orta şöbəni ilgək şəklində əyilmiş iri həcmli bağırsaq təşkil edir. Dal şöbə qısa dal bağırsaqdan ibarət olub anal dəliyi ilə nəhayətlənir . Anal dəliyi bədənin ön hissəsindəki çıxıntılar olan tacın arxasında yerləşir və birbaşa xaricə açılır. Bağırsağın xarici divarı peritoneal epiteli ilə örtülmüşdür . Rekraktor adlanan əzələ orta bağırsağın ilgək şəklində əyilmiş hissəsinə birləşir, onun yığılması nəticəsndə əvvəlcə bağırsaq , sonra isə polipid hissə bütövlükdə sistid hissənin içərisinə doğru çəkilir.

Sinir sistemi oturaq həyat tərzi ilə əlaqədar çox sadədir və demək olar ki, hiss orqanlarından məhrumdur. Sinir sistemi udlaq ilə dal bağırsağın arasında yerləşən tək udlaqüstü sinir düyünündə və ondan uzanan sinirlərdən ibarətdir. Çıxıntıların üzərində hissedici tükcüklər yeganə hiss orqanlarıdır. Briozoyların tənəffüs və qan –damar sistemi yoxdur . Tənəffüs bütün bədən səthini , çıxıntılar tənəffüs orqanı rolunu oynayır . Briozoyların qan –damar sisteminin reduksiya etməsi onların kiçik ölçülü olmaları və koloniya halında yaşamaları ilə izah olunur.

İfrazat orqanları yoxdur .İfrazat məhsulları bağırsağın və çıxıntıların divarındakı faqosit hüceyrələr vasitəsilə xaric edilir .

Cinsi orqanlar sisteminə görə briozoylar hermofrodit orqanizmlərdir . Onlar cinsi və qeyri – cinsi yolla çoxalırlar

Briozoylarda cinsi məhsullar selomun epiteli hüceyrələrində əmələ gəlir . Şirinsu briozoylarının sürfələri dəniz briozoylarının sürfələrinə nisbətən daha sadə quruluşludur. Hazırda briozoyların 4000 - ə qədər növü məlumdur . Qazıntı halında tapılan növlərin sayı isə 15000 –dən çoxdur . [1]

B.İ.Ağayev, Z.A.Zeynalova. Onurğasızlar zoologiyası. Bakı , «Təhsil» 2008 , 568 səh

Briozoylar (lat. Ectoprocta və ya Bryozoa) — İlkağızlılar yarımbölməsindən onurğasız heyvan tipi.

Hazırda 4000 növü məlumdur, onlardan Xəzər dənizində 6 növ qeyd edilmişdir. Bowerbankia imbricata, Bowerbankia grasilis, Paludicella articulata, Victorella pavida Xəzərdə geniş yayılmışlar. Conopeum seurati Xəzər dənizinə 1958-ci ildə Azov dənizindən gəlmişdir. Hazırda bioloji örtüklərin əmələ gəlməsində mühüm rol oynayır.

Els briozous (Briozoa) o ectoproctes són un embrancament d'animals invertebrats aquàtics petits, caracteritzats per la presència d'un lofòfor i tentacles ciliats que serveixen per capturar aliment. Normalment mesuren uns 0,5 mm de longitud. S'han descrit unes 4.000 espècies. La majoria d'espècies marines viuen en aigües tropicals, però unes poques habiten a fosses marines, i altres habiten en aigües polars. Una classe viu únicament en una varietat d'entorn d'aigua dolça, i uns pocs membres d'una classe majoritàriament marina prefereixen les aigües salobres. Exceptuant un gènere, els briozous formen grans colònies de membres microscòpics. Es depositen a les costes quan hi ha vents forts o activitat en un llac. També se'ls coneix com "animal molsa", ja que moltes vegades el seu aspecte recorda una coberta subaquàtica de molsa.

Com els braquiòpodes, es caracteritzen per presentar un lofòfor evaginable, tret que situa als braquiòpodes i als briozous dins del clade Lophotrochozoa; la seva funció és principalment l'alimentació. Es tracta d'una corona de tentacles que generen corrents d'aigua cap a la boca de l'individu; al seu torn, aquests tentacles secreten una substància enganxosa que afavoreix la captura del plàncton, principal dieta dels briozous, i el dirigeixen cap a la boca.

El zoeci, o coberta protectora, pot ser quitinós o calcari, de forma cilíndrica i amb una obertura per a la sortida del polípide. Aquesta obertura pot presentar opercle o no.

En molts grups pot haver zooides especialitzats, donant un tret més avançat al grup. Els zooides especialitzats en la defensa de la colònia se'ls coneix com "avicularis". Els encarregats de la neteja, "vibracularis", i els que s'ocupen exclusivament de la reproducció, "gonanfis".

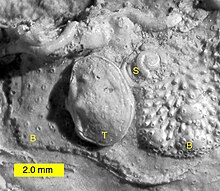

Briozous de l'ordovicià a una pissarra bituminosa trobada a Estònia

Els briozous (Briozoa) o ectoproctes són un embrancament d'animals invertebrats aquàtics petits, caracteritzats per la presència d'un lofòfor i tentacles ciliats que serveixen per capturar aliment. Normalment mesuren uns 0,5 mm de longitud. S'han descrit unes 4.000 espècies. La majoria d'espècies marines viuen en aigües tropicals, però unes poques habiten a fosses marines, i altres habiten en aigües polars. Una classe viu únicament en una varietat d'entorn d'aigua dolça, i uns pocs membres d'una classe majoritàriament marina prefereixen les aigües salobres. Exceptuant un gènere, els briozous formen grans colònies de membres microscòpics. Es depositen a les costes quan hi ha vents forts o activitat en un llac. També se'ls coneix com "animal molsa", ja que moltes vegades el seu aspecte recorda una coberta subaquàtica de molsa.

Com els braquiòpodes, es caracteritzen per presentar un lofòfor evaginable, tret que situa als braquiòpodes i als briozous dins del clade Lophotrochozoa; la seva funció és principalment l'alimentació. Es tracta d'una corona de tentacles que generen corrents d'aigua cap a la boca de l'individu; al seu torn, aquests tentacles secreten una substància enganxosa que afavoreix la captura del plàncton, principal dieta dels briozous, i el dirigeixen cap a la boca.

El zoeci, o coberta protectora, pot ser quitinós o calcari, de forma cilíndrica i amb una obertura per a la sortida del polípide. Aquesta obertura pot presentar opercle o no.

En molts grups pot haver zooides especialitzats, donant un tret més avançat al grup. Els zooides especialitzats en la defensa de la colònia se'ls coneix com "avicularis". Els encarregats de la neteja, "vibracularis", i els que s'ocupen exclusivament de la reproducció, "gonanfis".

Briozous de l'ordovicià a una pissarra bituminosa trobada a Estònia

Mechovci (Bryozoa) je kmen vodních prvoústých živočichů ze skupiny Lophotrochozoa. Patří k nim asi 5000 recentních druhů a několikanásobně více těch fosilních.[1] Jsou na první pohled podobní žahavcům, ale mají mnohem komplexnější tělní stavbu.[2][3]

Žijí obvykle koloniálně nebo ve skupinách vzájemně propojených jedinců, složených až z několika milionů těl. Jeden jedinec jen zřídka přesahuje velikost v řádu několika milimetrů, ale kolonie mohou dosahovat v některých případech až několika metrů. Vytváří povlaky na skalním podloží, lasturách či na stélkách řas. Někdy dokonce tvoří masivní povlaky na lodích: tyto mohou někdy způsobit zhoršení směrovatelnosti a účinnosti lodi; jindy zase mohou ucpávat kanalizační systémy.[1]

Tělo jedince (zooida) je tvořeno kalichem, který nese věnec obrvených chapadel. Ta umožňují příjem potravy, která sestává zejména z planktonu a detritu. Potrava postupuje do trávicí soustavy, která má tvar U - ústa i řitní otvor jsou uprostřed věnce chapadel.[3]

Aktuální klasifikace (2013) dělí kmen na tři třídy:[4]

(české názvy podle BioLib[5])

Kmen: Bryozoa Ehrenberg, 1831 – mechovci

Mechovci (Bryozoa) je kmen vodních prvoústých živočichů ze skupiny Lophotrochozoa. Patří k nim asi 5000 recentních druhů a několikanásobně více těch fosilních. Jsou na první pohled podobní žahavcům, ale mají mnohem komplexnější tělní stavbu.

Mosdyr (Bryozoa ) er en række af små vandlevende, fastsiddende, hvirvelløse dyr. De enkelte dyr er normalt under 1 mm store, men lever i kolonier som kan blive mange cm store. Mosdyr er filterædere, og filtrerer fødepartikler fra vandet ved en udskydelig "krone" af tentakler besat med fimrehår. Dyrenes bagkrop danner en skal (kaldet "zooecium") som hele dyret kan trække sig ind i. Kolonier af mosdyr dannes af mange sådanne zooecier siddende i et tæt "net", og kan danne en hvidlig overflade på sten, muslinger, alger og endog krebsdyr.

Mosdyr lever i eller i forbindelse med vand, enten permanent under vandet eller langs med kyster hvor de overskylles jævnligt. Visse arter lever på dybere vand, f.eks. i ocean-gravene. De fleste lever i tropiske vande, men der findes også arter som lever i koldere og endog arktiske vande. De flese lever i saltvand, men der findes også arter der lever brak- eller ferskvand. [1] [2] [3]

Mosdyr (Bryozoa ) er en række af små vandlevende, fastsiddende, hvirvelløse dyr. De enkelte dyr er normalt under 1 mm store, men lever i kolonier som kan blive mange cm store. Mosdyr er filterædere, og filtrerer fødepartikler fra vandet ved en udskydelig "krone" af tentakler besat med fimrehår. Dyrenes bagkrop danner en skal (kaldet "zooecium") som hele dyret kan trække sig ind i. Kolonier af mosdyr dannes af mange sådanne zooecier siddende i et tæt "net", og kan danne en hvidlig overflade på sten, muslinger, alger og endog krebsdyr.

Mosdyr lever i eller i forbindelse med vand, enten permanent under vandet eller langs med kyster hvor de overskylles jævnligt. Visse arter lever på dybere vand, f.eks. i ocean-gravene. De fleste lever i tropiske vande, men der findes også arter som lever i koldere og endog arktiske vande. De flese lever i saltvand, men der findes også arter der lever brak- eller ferskvand.

Moostierchen (Ectoprocta (Gr.: mit äußerem After)), auch Bryozoa oder Polyzoa genannt, sind vielzellige Tiere, die im Wasser leben. Aufgrund ihrer mikroskopischen Größe sind Einzeltiere schwer auszumachen, ausgedehntere Kolonien sind aber leicht als flächige Struktur, zum Beispiel auf angeschwemmtem Seetang, zu erkennen.

Moostierchen gehören zu den Lophotrochozoen, also einer Großgruppe der Urmünder (Protostomia). Ihr genaues Verwandtschaftsverhältnis zu anderen Lophotrochozoa-Stämmen ist zurzeit unklar. Weder die häufig vermutete Beziehung zu den Kelchwürmern (Entoprocta), noch zu den Hufeisenwürmern (Phoronida) und Armfüßern (Brachiopoda) konnte durch molekulargenetische Testmethoden bestätigt werden. In älteren Lehrbüchern findet man sie aber oft mit den Phoronida und Brachiopoda zum Stamm der Tentaculata vereinigt.

Moostierchen bilden meist Kolonien (Zoarium) aus mehreren Einzeltieren (Zooiden). Das einzelne Zooid besteht aus einem Weichkörper und einer schützenden Schale, dem es umgebenden, extrazooidalem, Skelett (Zooecium). Der Weichkörper besteht aus dem Polypid (= Vorderkörper; frei bewegliche Teile) und dem Cystid (= Hinterkörper; in den das Polypid mittels Rückziehmuskeln komplett eingezogen werden kann). Das Polypid wird aus dem Cystid gebildet. Das Verdauungssystem ist in Mund, Mitteldarm, Enddarm und After gegliedert. Der After ist dabei nicht endständig, sondern kommt durch den U-förmigen Darm in der Nähe des Mundes außerhalb des Tentakelkranzes (Lophophor) zu liegen. Den Mund umgeben Tentakel, die auf einem kreisförmigen oder zweiteiligen Lophophor sitzen. Die Darmkanäle der Einzeltiere stehen nicht wie bei den Nesseltierkolonien miteinander in Verbindung.

Innerhalb der Kolonien kommt es zu Arbeitsteilungen. Stark rückgebildete Tiere bilden Stielglieder, Ranken oder Wurzelfäden. Andere Einzeltiere bilden Geschlechtszellen, wieder andere werden zu Ammentieren oder zu vogelkopfähnlichen Avicularien oder Vibrakularien, die das Festsetzen von Fremdorganismen auf der Kolonie verhindern. Bei den spezialisierten Tieren der Kolonie sind sowohl die Tentakelkrone als auch meist der Darm zurückgebildet.

Trugkoralle

(Myriapora truncata)

Kolonie von Cristatella mucedo (Süßwassermoostierchen)

Die Tiere können sich geschlechtlich oder ungeschlechtlich fortpflanzen.

Aus der geschlechtlichen Fortpflanzung gehen zwei verschiedene Typen von Larven hervor: Die als Cyphonaut bezeichnete planktotrophe Larve stellt die "primitive" Form dar. Sie ernährt sich über Wochen oder sogar Monate hinweg im Plankton. Die lecitothrophe Larve setzt sich schon nach einigen Stunden mit der Ventralfläche fest. Durch Metamorphose entsteht Ancestrula, die ersten 1–6 Zooide einer neuen Kolonie. Darauf folgt dann die ungeschlechtliche Fortpflanzung, durch welche die Kolonie weiter wächst.

Die ungeschlechtliche Fortpflanzung geschieht durch Knospen, ähnlich wie bei einer Pflanze, die bei den Süßwasserarten als Statoblasten bezeichnet werden. Dadurch können große Kolonien entstehen. Die durch ungeschlechtliche Fortpflanzung entstandenen Zooide innerhalb einer Kolonie sind folglich Klone, genetisch identische Nachkommenschaft der Ursprungs-Larve.

Es sind heute ca. 5.600 rezente und 16.000 fossile Arten von Moostierchen in Süß- und Salzwasser beschrieben. Die Klasse der Süßwassermoostierchen (Phylactolaemata) umfasst alle limnischen Arten.

In der Geologie haben sie aufgrund der weiten Verbreitung seit dem Ordovizium (Cyclostomata und Ctenostomata) eine hohe Bedeutung als Leitfossilien und für stratigraphische Bestimmungen. Im November 2021 wurde ein Fossil aus dem Kambrium gefunden. Es vereinigt Merkmale der Gruppen Stenolaemata und Ctenostomata. Zuvor waren keine sicheren Fossilien vor dem Ordovizium bekannt. Die neu entdeckte Art Protomelission gatehousei besitzt kein Kalk-Skelett (ein Merkmal der Ctenostomata) und eine zweiseitige Kolonialstruktur, ähnlich einem Blatt, mit Zooiden auf jeder Seite (wie bei den Stenolaemata). Von daher ist es anzunehmen, das Protomelission gatehousei einer der frühesten Vorfahren der Moostierchen ist.[1]

Über 125 Arten verursachen durch starkes Wachstum Schäden bzw. Unterhaltungskosten an Schiffen, Hafenanlagen und wasserwirtschaftlichen Anlagen (z. T. auch im Süßwasser).

Andererseits produzieren Bryozoen chemische Wirkstoffe, die hinsichtlich ihrer Wirkung Gegenstand medizinischer Forschung sind, darunter das mögliche Antikrebsmittel Bryostatin 1.

Moostierchen (Ectoprocta (Gr.: mit äußerem After)), auch Bryozoa oder Polyzoa genannt, sind vielzellige Tiere, die im Wasser leben. Aufgrund ihrer mikroskopischen Größe sind Einzeltiere schwer auszumachen, ausgedehntere Kolonien sind aber leicht als flächige Struktur, zum Beispiel auf angeschwemmtem Seetang, zu erkennen.

Moostierchen gehören zu den Lophotrochozoen, also einer Großgruppe der Urmünder (Protostomia). Ihr genaues Verwandtschaftsverhältnis zu anderen Lophotrochozoa-Stämmen ist zurzeit unklar. Weder die häufig vermutete Beziehung zu den Kelchwürmern (Entoprocta), noch zu den Hufeisenwürmern (Phoronida) und Armfüßern (Brachiopoda) konnte durch molekulargenetische Testmethoden bestätigt werden. In älteren Lehrbüchern findet man sie aber oft mit den Phoronida und Brachiopoda zum Stamm der Tentaculata vereinigt.

Ang Bryozoa ay isang phylum sa kahariang Animalia.

|doi_brokendate= ignored (tulong) |month= ignored (tulong) ![]() Ang lathalaing ito na tungkol sa Hayop ay isang usbong. Makatutulong ka sa Wikipedia sa nito.

Ang lathalaing ito na tungkol sa Hayop ay isang usbong. Makatutulong ka sa Wikipedia sa nito.

Bryozoa (an aw kent as the Polyzoa, Ectoprocta or commonly as moss ainimals)[6] are a phylum o aquatic invertebrate ainimals.

Bryozoa (an aw kent as the Polyzoa, Ectoprocta or commonly as moss ainimals) are a phylum o aquatic invertebrate ainimals.

Classicament apelat grop dels briozoaris o Bryozoa.

Aqueste grop qu'aparten al superembrancament dels Lophophorata, aparegut a l'Ordovician, es totjorn actual.

Aquestes pichons animals son apelats los zoïdes, vivon dins de lòtjas successivas, las zoecias, que fòrman una colonia, lo zoarium. Produson de matèria carbonatada.

Briozones, ance nomida Polizon o Ectoprocto.

└─o Ectoprocto o Briozon ├─o Filactolamato o Plumatelido └─o ├─o Stenolemato │ ├─? Ederelido (estinguida) │ ├─o Trepostomato (estinguida) │ ├─o Sistoporato (estinguida) │ │ ├─o Seramoporino (estinguida) │ │ └─o Fistuliporino (estinguida) │ ├─o Criptostomato (estinguida) │ │ ├─o Streblotripino (estinguida) │ │ ├─o Goldfusitripino (estinguida) │ │ ├─o Timanodictino (estinguida) │ │ ├─o Rabdomesino (estinguida) │ │ └─o Ptilodictino (estinguida) │ ├─o Fenestrato (estinguida) │ └─o Tubuliporato o Cyclostomato │ ├─o Fasiculino │ ├─o Canselato │ ├─o Serioporino │ ├─o Rectangulato o Licenoporido │ ├─o Articulato │ ├─o Paleotubuliporino │ └─o Tubuliporino └─o Jimnolemato ├─o Ctenostomato │ ├─o Benedeniporoideo o Protoctenostomato │ ├─o Alsionidino │ ├─o Flustrelidrino │ │ └─o Flustrelidroideo │ ├─o Victorelino │ ├─o Paludiselino o Paludiselido │ ├─o Vesicularino │ └─o Stoloniferino │ ├─o Everilioideo │ ├─o Ualkerioideo │ ├─o Vesicularioideo │ └─o Terebriporoideo └─o Celostomato ├─o Inovicelato o Etedo ├─o Scruparino ├─o Malacostego o Membraniporoideo ├─o Flustrino │ ├─o Caloporoideo │ ├─o Buguloideo │ ├─o Selarioideo │ └─o Microporoideo └─o Ascoforo ├─o Acantostego │ ├─o Cribrilinoideo │ ├─o Bifaxarioideo │ ├─o Nefroporideo │ └─o Cateniseloideo ├─o Ipotomorfo ├─o Umbonulomorfo │ ├─o Aracnopusioideo │ ├─o Adeonoideo │ └─o Lepralieloideo └─o Lepraliomorfo ├─o Batoporoideo ├─o Seleporoideo ├─o Mamiloporoideo ├─o Urseoliporoideo ├─o Smitinoideo └─o Scizoporeloideo

Briozones, ance nomida Polizon o Ectoprocto.

Mahovnjaci (lat. Bryozoa – poznati i kao Polyzoa ili Ectoprocta[3] – su koljeno vodenih životina iz grupe beskičmenjaka. Obično su dugi oko 0,5 mm, a hrane se filtriranjem i prosijavanjem čestica hrane iz vode, koristeći se uvlačivim lofoforama, "krunama" pipaka koji su obloženi cilijama. Većina morskih vrsta živi u tropskim vodama, ali nekoliko vrsta je pronađeno u okeanskim brazdama, dok su drugi pronađeni i u polarnim vodama. Vrste jednog razreda žive samo u različitim slatkovodnim okruženjima, a nekoliko vrsta (uglavnom morskog razreda) vole slane vode. Danas je poznato više od 4.000 vrsta. Vrste jednog roda žive samotnjački, a ostale su grupisane u kolonijama.[4]

Koljeno se prvobitno zvalo "Polyzoa", ali ovaj naziv je zamijenjen sa "Bryozoa" 1831. godine. Druga grupa životinja koja je otkrivena kasnije, a čiji je mehanizam filtriranja izgledao slično, također je uključena u "Bryozoa" sve do 1869. godine. Međutim, tada se pokazalo da su dvije grupe bile međusobno veoma različite. Šta više, tada je nedavno otkrivena grupa dobila ime Entoprocta, dok su prvobitne "Bryozoa" zvali "Ectoprocta". Međutim, za drugu grupu je u širokoj upotrebi ostao naziv Bryozoa.

Mahovnjaci obuhvataju prepoznatljivu i izdvojenu grupu morskih, rjeđe slatkovodnih, sitnih beskičmenjaka, koja je izdvojena iz koljena Tentaculata ili Lophophorata. Imaju sesilni način života organiziran u kolonijama. Obično prekrivaju stijene, druge predmete i biljke, osobito alge i to u gustim nakupinama koje liče na mahovine.

Tijelo mahovnjaka je u obliku čašice sa peteljkom koja je pričvršćena za podlogu. Donji dio izlučuje kućicu od sluzi, hitina ili krečnjaka, a na gornjem, mehkom kraju nalaze se usta s vjenčićem treplji koje stvaraju vrtložna strujanja sa sitnijim česticama hrane. Nemaju sistem provođenja tjelesnih tečnosti, a većina je hermafroditna. Morski oblici se razmnožavaju vanjskim, a slatkovodni unutrašnjim pupanjem. Kada se razmnožavaju spolno, iz oplođenih jaja razvija se larva, koja neko vrijeme slobodno pliva, a zatim se spusti na dno i preobrazi u odraslu životinju.[4]

Jedinke u kolonijama briozoa (Ectoprocta) nazivaju se zooidi, jer nisu u potpunosti nezavisne životinje. Sve kolonije sadrže autozooide, koji su odgovorni za hranjenje i izlučivanje. Kolonije nekih razreda imaju različite vrste nehranećih zooida specijalista od kojih su neke mrijestilišta za oplođena jaja, a neke klase imaju posebne zooide za odbranu kolonije. Najveći broj vrsta je u razredu Cheilostomata, možda zato što imaju najširi spektar specijalističkih zooida. Nekoliko vrsta može se uvući vrlo polahko pomoću bodljikavih defanzivnih zooida kao noge.

Autozooidi snabdijevaju hranjivim tvarima nehranjive zooide kanalima koji variraju između klasa. Svi zooidi, uključujući i one u usamljeničkih vrsta, sastoje se od cistida koji daje tjelesni zid i proizvodi egzoskelet i polipide koji sadrže unutrašnje organe i lofofore ili druge specijalizirana proširenja. Zooidi nemaju posebne organe za izlučivanje, a polipidi autozooida bivaju odbačeni kada polipidi postanu preopterećeni otpadnim proizvodima. Tada obično tjelesni zid raste zamjenjujuči polipide. Autozooidi imaju želudac je u obliku slova U, s ustima unutar "krune" pipaka i anusom izvan nje. Kolonije se razvijaju u različitim oblicima, uključujući uvijene, žbunaste i listaste. Cheilostomata proizvode mineralizirani egzoskelet i stvaraju jednoslojne listove koji prožimaju površine.

Zooidi svih slatkovodnih vrsta su simultani hermafroditi. Iako kao mnoge morske vrste funkcioniraju prvo kao mužjaci, a zatim kao ženke, njihove kolonije uvijek sadrže kombinaciju zooida koji su u svojim muškim i ženskim fazama. Sve vrste otpuštaju spermu u vodu. Neki otpuštaju jaja u vodu, dok drugi hvataju spermu pomoću pipaka i interno oplode svoja jaja. U nekih vrsta larve imaju velika žumanca, kojima se hrane i brzo se poravnaju na površini. Druge proizvode larve koje imaju malo žumance, ali plivaju i hrane za nekoliko dana prije toga. Nakon iscrpljivanja hrane, sve larve prolaze kroz radikalnu metamorfozu koja uništava i obnavlja gotovo sva unutrašnja tkiva. Slatkovodne vrste proizvode statoblaste koji leže uspavano dok su povoljni uslovi, što omogućava lozi kolonije da preživi, čak i ako se u teškim uslovima ubije matična kolonija.

U predatore morskih mahovnjaka spadaju: morski puževi, ribe, morski ježevi, piknogonide, rakovi, grinje i morske zvijezde. Slatkovodni mahovnjaci su plijen puževima, insektima i ribama. U Tajlandu, mnoge populacije jedne slatkovodne vrste su iskorijenjene dolaskom uvedene vrste puža. Brzo rastuća invazivna bryozoa sa sjeveroistočnih i sjeverozapadnih obala SAD-a je ograničila je kelpske šume do te mjere da je pogodila lokalne populacije riba i beskičmenjaka. Mahovnjaci su se proširili kao bolesti ribnjaka i ribara. Hemikalije koje su izvučene iz morskih vrsta mahovnjaka su u fazi istraživanja za liječenje raka i Alzheimerove bolesti, ali analize nisu ohrabrujuće.

Mineralizirani skeleti mahovnjaka prvo su se pojavili u stijenama sa početka ordovicijskog perioda,[1] čineći posljednje veliko koljeno koje se pojavilo u fosilnom zapisu. To je dovelo istraživače na sumnju da su mahovnjaci nastali ranije, ali su na početku bili nemineralizirani i možda su se značajno razlikovali od fosiliziranih i modernih oblicika. Rani fosili su uglavnom uspravnog oblika, ali inkrustrirani oblici postupno su postali preovladavajuċi. Neizvjesno je da li je koljeno monofiletsko. Evolucijski odnos mahovnjaka prema drugim koljenima su nejasni, dijelom zbog toga što je pogled naučnika na porodično stablo životinja uglavnom pod uticajem poznatijih koljena. Morfološka i molekulskofilogenijska analiza se ne slažu oko odnosa mahovnjaka s entoproktama, u tome da li mahovnjake treba grupisati sa brahiopodama i [[foronoid]ima u Lophophorata i da li mahovnjke treba svrstati u protostome ili deuterostome.

Struktura svih glista u peharu vrlo je ujednačena. Sastoje se od mišiće stapke, na čijem je donjem kraju oblikovano stopalo s ljepljivom žlijezdom i čašice, koja predstavlja stvarno tijelo i ima krunu šiljatih bodlji i čekinja. Veličina pojedinih životinja (zooida) obično je oko milimetar; najmanja poznata vrsta je Loxomespilon perezi s oko 0,1 milimetra, a najveća Barentsia robusta s visinom od oko sedam milimetara. Pojedinačne životinje su bilateralno simetrične strukture i slične površnine polipa u Hydrozoa, uključujući i Cnidariansu Za razliku od njih, čašice entoprokta nisu uvučene, već se mogu samonamotati.

Vanjski sloj životinja formira jednoslojna epiderma, koja je na vanjskoj strani ograničena želatinoznim slojem . Muskulatura, koja se sastoji od nagnutih vlakana u predjelu čašice i spaja se u uzdužnu mišiće u stabljici, leži ispod. Tjelesna šupljina kod ovih životinja je pseudocelom ispunjen tečnošću sa izoliranim nakupinama mezenhimskih ćelija, u kojima nema epitelnih obloga slobodnog prostora. Organi životinja se nalaze u peharu, pri čemu je crijevni kanal u obliku slova U i zauzima većinu prostora. Crijevo nema vlastite mišiće, a u unutrašnjosti se nalaze cilije , koje transportuju hranu do centralnog dijela, želuca. Tu se odvija probava i apsorpcija hranjivih sastojaka.Povrh toga, krov želuca, poput jetre kičmenjaka, glavno je skladište i metabolički organ, a služi i za izlučivanje, jer se krajnji metabolički proizvodi izbacuju iz tjelesne šupljine u crijevni trakt. Usni otvor i anus otvaraju se prema gore u predjelu atrija, u kojem se nalazi pipci. Kao organi za izlučivanje i osmoregulaciju služe uparene protonephridije, kao i za odvod iz kesastih gonada .

Nervni sistem je jednostavan i ima jednostavnu gangliju u obliku crijeva. Nervni snopovi od toga idu do mišića čašice, šipki i stapke. Na površini pehara nalaze se mehanoreceptori i dodatni čulni organi s unutarnje strane atena. Ove životinje nemaju organe osjetljive za svjetlost.

Larva ima prosječni promjer od samo 50 do 100 mikrometra i pokazuje niz sličnosti sa rasprostranjenom larvom zvanom trohrofora. Razlike postoje između ostalog i u kupolastoj izvedbi gornje polovine (episfera) s krunskim pločama na gornjem, apikalnom kraju. Zbog ove kupole, dolazi naziv "trohoforna larva" (grčkli throchos = kupolasti krov, svod) predložen (Salvini-Plawen) 1980. Na dnu episfere uzdiže se vijenac koji služi za kretanje tokom početnog plutajućeg (pelagiškog) načina života larve. U većini vrsta na epizefiri je formiran senzorni organ koji se sastoji od trepljastog nabora i para svjetlosnih senzornih organa (ocela) kod životinja koje bi se kasnije mogle oživjeti (predoralni organ). Praoralni organ je uparen u kasnijim samotnim oblicima, neparni u slučaju oblika koji formiraju kolonije. Donja polovina larve, hiposfera, u potpunosti je uronjena u episferu tokom plivanja i zato je spolja teško vidljiva. To je bio glavni razlog početnog izjednačavanja sa larvom trohofora. Tek kada je postalo jasno da se u drugoj, živoj sredini (bentoskoj), transformirana hiposfera koristi kao puzajuća potplata, izjednačavanje s trohoforom je relativizirano (međutim, kod nekih vrsta Kamptozoa, nema ove druge faza života u tlu).

Usni otvor je na rubu hiposfere, ispod vijenaca treplji i vodi kroz crijevni kanal u obliku slova U do anusa, koji je takođe u hiposferi. Trohofora takođe ima protonefridije, koje služe za izlučivanje tjelesnog otpada.

Peharasti crvi žive kao filtrirajući suspendirane materije iz vode, uz pomoć svojih antena i ostalih dodataka. Oni izlučuju ljepljivu sluz, na koju se čestice lijepe, na cilijaa pipaljki dovodeći ih do usnog otvora. Stiskanjem uzdužnih mišićnih vlakana, pojedine životinje izvode kretnje u vidu kretanja klatna i karakteristične pokrete pehara kako bi povećale performanse filtracije.

Većina vrsta su solitarni (samotni) oblici, pričvršćen za podlogu, ali otprilike trećina vrsta također formira kolonije s nekoliko jedinki, čije su grane povezane pomoću stapki.

Kamptozoa se mogu razmnožavati i seksualno i aseksualno. U porodici Pedicellinidae u osnovi su istovremeno hermafroditi , tj. trajno imaju i muške i ženske genitalne organe, Loxosomatidae su protandrični hermafroditi, što znači da se prvo razvijaju muški, a potom i ženski spolni organi.

Barentsidae imaju razdvojene spolove, a se javljaju u koloniji. U osnovi, mužjaci s testisima uvijek se formiraju prvi, a razvoj ženskih zooida ovisi o prisutnosti potpuno razvijenih mužjaka u koloniji. Životni vijek pojedinih životinja je oko šest nedjelja.

Bespolna reprodukcija nastaje pupanjem ektoderma čašičnog zida, što je rezultira pojavom genetički iz identičnog (klonskog) potomstvA. Pupoljci nastaju u ZIDU čašice u predjelu usta ili, u slučaju oblika KOJI formiranja kolonije, na DRŠCI. Tek nakon završetka stvaranja pupoljka, majčinske mezenhimske ćelije migriraju u novostvorenu životinju i formiraju mišiće i vezivno tkivo. U kolonijalnim vrstama, mlade životinje ostaju povezane s matičnom životinjom preko stabljike i produžujući spojnu dršku na mjestu spajanja. Kao rezultat toga, nastaju matične ili visoko razgranate drvolike kolonije, koje kod nekih vrsta poput Pedicellinopsis fructiosa dostižu visine i do 2,5 centimetra s hiljadama pojedinih zooida . Regeneracijskii kapacitet od Kamptozoa je relativno ograničen i samo utiče na regeneraciju oštećenih pipaka. Pomoću stablolikih oblika kolonija mogu se obnoviti stabljike iz blastoderma stabljike, pa one mogu služiti kao stadiji opstanka (posebno u porodici Barentsiidae). Neke kolonije tvore i vrlo zakašnjele pupove, koji postaju pravi zooidi tek kada je ostatak kolonije ugine.

U slučaju seksualne reprodukcije, muške životinje ispuštaju spermu u slobodnu vodu, odakle se unosi u ženske životinje. Oplodnja se odvija u jajniku ženki, odakle oplođeni zigoti migriraju u atrij i skladište se u posebnim parovima džepova koji se nalaze na obje strane rektuma . U embrionskom razvoju spiranom gastrulacijom, svaka od formirane dvije manje (mikromere) i dvije veće ćelija (makromere) postavljaju se spiralno jedne protiv drugih. Od 4d ćelija razvijaju se telomezoblasne ćelije, porijeklom iz mezodermnog tkiva. To je kod Spiralia tipski spiralni kvartet-4D-brazdanja. Zbog ove osobine potrebno je uzeti u obzir bliski odnos vrčastog crva i drugih spiralijaa. Glavni fokus ovdje je na crve i mehkušce.

Peharasti crvi mogu se naći širom svijeta, u vodama obalnih područja. Većina vrsta je morska, a rasprostranjena Urnatella gracilis jedina je vrsta koja živi u slatkoj vodi. Njena veća brojnost je pronađena samo u Sjevernoj Americi, i odakle je unesena u Evropu i Aziju.

Pojedine životinje vrlo često se nastanjuju na drugim beskičmenjacima kao što su spužve, plućašice, bodljokošcii, a rjeđe i rakovi, gdje imaju koristi od turbulencije vode zbog kretanja i hranjenja većih životinja. Kolonije žive na svim podlogama koje su izložene struji, posebno na hidrodnim štapovima, školjkama i puževima .

Mahovnjaci, foronidi i brahiopodi hrane se iz vode, filtrirajući čestice pomoću lofofora, "krune" šupljeg pipka. Mahovnjaci stvaraju kolonije koje se sastoje od klonova zvanih zooidi, koji su obično dugi oko 0,5 mm, rijetko 1 mm. Foronidi u cjelini imaju mahovnjačke zooide, ali su dugi oko 2 do 20 cm i iako često rastu u gomilam, ne stvaraju kolonije koje se sastoje od klonova.

Za brahiopode se općenito misli da su blisko srodni mahovnjacima i foronidima, ali se razlikuju po tome što imaju ljušturu koja liči na onu kod školjki Bivalvia. Svatri koljena imaju celom, unutrašnju duplju koja je prekrivena mezotelom.

Neke kolonije inkrustrirane mimahovnjacima sa mineraliziranim egzoskeletom izgledaju kao mali korali. Međutim, mahovnjačke kolonije osniva ancestrula koja je okrugla, a ne u obliku normalnog zooida date vrste. S druge strane, osnivački polip korala ima oblik kao i njegove kćeri polipi, a koralni zooidi nemaju celom ili lofofore.

Entoprokti, drugo koljeno sa filtriranjem hrane po tome dosta liče na mahovnjake, ali njihove strukture za uzimanje hrane koje liče na lofofore, imaju čvrste pipke i anus koji se nalazi u unutrašnjosti, a ne izvan baze "krune" i nemaju celom.

Pregled razdvajajućih svojstavaZbog svoje male veličine i nedostatka tvrdih tvari u njihovim tijelima, filogenetski dokazi o peharasim crvima vrlo su nepotpuni. Najstariji poznati oblici potječu iz kasnog jure, a nađeni su u Engleskoj.

Vanjska klasifikacija peharastih crva još uvijek nije u potpunosti razjašnjena. Prvobitno su ih potpuno svrstali umahovnjake (Bryozoa), ali većina je urednika odbacila ovu klasifikaciju. Na temelju ontogenetskih opažanja pojedini autori, posebno Nielsen (1979), ih smještaju u neposrednu blizinu Bryozoa. Ax 1999 [2] , s druge strane, predlaže alternativnu klasifikaciju u srodstvu sa mehkušcima (Mollusca) i rezultirajući takson naziva Lacunifera, uzimajući, kao argumente, u obzir finu strukturu kutikule, strukturu tjelesne šupljine kao sistem lakuna i finu strukturu cilija. Još jedna prednost ove hipoteze vidi se u činjenici da se između trohoforskih liarvi nekih mehkušaca i peharastih crva može uspostaviti evolucijska povezanost koja izgleda kao da je puzajuća larva (u ekstremnim slučajevima čak i stopalo pauka mehkušca potiče od larve crvenog luka!) , S molekularnobiološkog gledišta , međutim, ne može se potvrditi blizina vrčatih glista i Bryozoa niti aksijanska hipoteza Lacunifera. Ako se smatra da su larve celomskih crva modificirane trohofore, potrebno je formulirati najmanje dva evolucijska modela u odnosu na njihovo porijelo, od kojih se u svakom podrazumijeva loza tjelesnih slojeva sličnih Annelidama u najširem smislu. Zbog organizacije Entoprocta kao celomskih životinja sa spiralnim brazdanjem, ponekad se ne sumnja na bilo kakvu prepoznatljivu strukturu po kojoj se peharasti crvi mogu pratiti izravno do porodice Trochophorae, koji su već odrasli i u adolescenciji (progenetske Trochophorae). U drugoj verziji vide se Entoprocta, koji se postepeno selekcioniraju i transformiraju. Promjene u obliku larve odvijale bi se paralelno s preobražajem odraslih oblika. Izvjesna blizina vilinskih glista, potvrđena je prvim molekulskogenetičkim istraživanjima rRNK (Mackay i sur. 1995.), međutim mnoge druge linije Lophotrochozoa također pokazuju molekulskogenetičke sličnosti s oblim glistama (uključujući i mehkušce). Prema posljednjim genetičkim istraživanjima, trakavice formiraju sestrinsku grupu drugog sjedećeg patuljastog oblika, Cycliophora, koji je opisan tek 1995. (Halanych 2004). Stoga bi se mogla odbaciti pretpostavka odnosa sestrinske grupe prema mahovnjacima ili mehkušcima. Postoji oko 150 vrsta peharastih glista koje su razvrstani u četiri porodice. Izvorno smatrane kao samotne, Loxosomatidae sadrže oko dvije trećine poznatih vrsta i u poređenju s drugim porodicama nalaze se kao bazna sestrinska grupa Solitaria. Predstavnici ostalih porodica formiraju kolonije i svrstane su kao Coloniales; ovdje se Astolonata (Loxokalypodidae) opet uspoređuju sa Stolonata. Kao filogenetski sistem, to rezultira u:

Kelchwürmer ColonialesAstolonata (Loxokalypodidae)

Solitaria (Loxosomatidae)

Pojedinačno sadrže sljedeće rodove:

Mahovnjaci (lat. Bryozoa – poznati i kao Polyzoa ili Ectoprocta – su koljeno vodenih životina iz grupe beskičmenjaka. Obično su dugi oko 0,5 mm, a hrane se filtriranjem i prosijavanjem čestica hrane iz vode, koristeći se uvlačivim lofoforama, "krunama" pipaka koji su obloženi cilijama. Većina morskih vrsta živi u tropskim vodama, ali nekoliko vrsta je pronađeno u okeanskim brazdama, dok su drugi pronađeni i u polarnim vodama. Vrste jednog razreda žive samo u različitim slatkovodnim okruženjima, a nekoliko vrsta (uglavnom morskog razreda) vole slane vode. Danas je poznato više od 4.000 vrsta. Vrste jednog roda žive samotnjački, a ostale su grupisane u kolonijama.

Koljeno se prvobitno zvalo "Polyzoa", ali ovaj naziv je zamijenjen sa "Bryozoa" 1831. godine. Druga grupa životinja koja je otkrivena kasnije, a čiji je mehanizam filtriranja izgledao slično, također je uključena u "Bryozoa" sve do 1869. godine. Međutim, tada se pokazalo da su dvije grupe bile međusobno veoma različite. Šta više, tada je nedavno otkrivena grupa dobila ime Entoprocta, dok su prvobitne "Bryozoa" zvali "Ectoprocta". Međutim, za drugu grupu je u širokoj upotrebi ostao naziv Bryozoa.

Mieschdierli (Ectoprocta (Gr.: mit usserem After)), au Bryozoa oder Polyzoa gnännt, sin vylzälligi Dierer, wu im Wasser läbe. Wäg ihre mikroskopische Greßi sin Ainzeldierer schwär uuszmache, uusdehnteri Kolonie sin aber lycht as flechigi Struktur, zem Byschpel uf aagschwämmtem Seetang, z chänne.

Mieschdierli ghere zue dr Lophotrochozoe, ere Großgruppe vu dr Urmyyler (Protostomia). Ihre gnau Verwandtschaftsverhältnis zue anderene Lophotrochozoa-Stämm isch zurzyt uuklar. Di hyfig vermuetet Beziehig zue dr Chelchwirmer (Entoprocta) het dur molekulargenetischi Teschtmethode nit chenne bstetigt wäre, au nit e necheri Verwandtschaft zue Huefyysewirmer (Phoronida) un dr [[ArmfüßerTentaculata verainigt.

Mieschdierli bilde zmaischt Kolonie (Zoarium) us mehrere Ainzeldierer (Zooide). S ainzel Zooid bstoht us eme Waichlyyb un ere Schale as Schutz, em extrazooidale Skelett (Zooecium). Dr Waichlyyb bstoht us em Polypid (= Vorderlyyb; frei bewegligi Dail) un em Cystid (= Hinterlyyb; wu s Polypid dur Ruckziemuskle komplett cha yyzoge wäre). S Polypid wird us em Cystid bildet. S Verdauigssyschtem isch in Muul, Mitteldarm, Änddarm un After glideret. Dr After isch doderby nit ändständig, är lyt dur dr U-fermig Darm in dr Neche vum Muul usserhalb vum Tentakelchranz (Lophophor gnännt). S Muul isch umgee vu Tentakle, wu uf eme chraisfermige oder zwaidailige Lophophor hocke. D Darmkanäl vu dr Ainzeldierer stehn nit wie bi dr Nesseldierkolonie mitenander in Verbindig.

Innerhalb vu dr Kolonie chunnt s zue Arbetsdailige. Stark ruckbildeti Dierer bilde Stiilgliider, Hoke oder Wurzelfäde. Anderi Ainzeldierer bilde Gschlächtszälle, wider anderi wäre zue Ammedierer oder zue vogelchopfähnlige Avicularie oder Vibrakularie, wu s Feschtsetze vu Främdorganisme uf dr Kolonie verhindere. Bi dr spezialisierte Dierer vu dr Koloni sin d Tentakelchrone un au zmaischt dr Darm zruckbildet.

D dierer chenne sich gschächtlig oder uugschlächtlig furtpflanze.

Us dr gschlächtlige Furtpflanzig gehn zwee verschideni Type vu Larven firi: Di Cyphonaut gnännt planktotroph Larve stellt di "primitiv" Form dar. Si nehrt sich iber Wuche oder sogar Monet vu Nahrigspartikel im Plankton. Di lecitothroph Larve setzt sich scho no ne baar Stund mit dr Ventralflechi fescht. Dur Metamorfos entstehn Ancestrula, di erschte 1-6 Zooide vun ere Koloni. Derno chunnt di uugschlächtlig Furtpflanzig, wu d Koloni wyter derdur wachst.

Di uugschlächtlig Furtpflanzig gschiht dur Chnoschpen, ähnlig wie bin ere Pflanze, wu bi dr Sießwasserarte Statoblaschte gnännt wäre. Doderdur chenne groß Kolonie entstoh. Di dur uugschlächtligi Furtpflanzig entstandene Zooide innerhalb vun ere Koloni sin wäge däm Klon, genetisch idäntischi Noochuu vu dr Ursprungs-Larve.

Hite sin rund 5.600 rezenti un 16.000 fossili Arte vu Mieschdierli in Sieß- un Salzwasser bschribe. D Klasse vu dr Sießwassermieschdierli (Phylactolaemata) umfasst alli limnische Arte.

In dr Geologi hän d Mieschdierli wäg ihre wyter Verbraitig syt em Ordovizium (Cyclostomata un Ctenostomata) e großi Bedytig as Laitfossilie un fir stratigrafischi Bstimmige.

Iber 125 Arte verursache dur stark Wachstum Schäde bzw. Unterhaltigscheschte an Schiff, Hafenaalage un wasserwirtschaftligen Aalage, zum Dail au im Sießwasser.

Uf dr andere Syte produziere Bryozoe chemischi Wirkstoff, wu di medizinisch Wirkig vun ene untersuecht wird, dodrunter s meglig Antichräbsmittel Bryostatin 1.

De mosbieëster, mosbieësjkes of mosdeerkes (Letien: Bryozoa of Ectoprocta; neet te verwarre mit de waterbaerkes) vörmen 'ne stam van oermunjige (Protostomata) die veural inne zieë laeve. Zoeaget 6000 laevendje saorte zeen besjreve geworen in deze stam, worónger de vleescelpoliep en 't blaadechtig häörewier.

Dees hoeagoet 1 mm lang waterbieësjkes laeven in doeasvörmige, toet kelonies verkitje huuskes. Sómtieds vörme ze koosjten op rotsen en zieëwier. Anger saorte vertuuenen euvereinkumste mit mos, det inne struiming haer en trögk wuuertj geweeg. Aafgestorve kelonies waere döks 't strandj op geworpe, wo ze waeren aangezeen veur verdruueg zieëwier. Mosbieëster gaeven euveren algemein de veurkäör aan werm, troeapische watere, meh kómmen euvere ganse werreld veur.

Binne de geologie, en mit naam de paleontologie, zeen Bryozoa wichtige indicatore veur 't aafzèttingsmiljeu van 'n bepaoldj saort aan stein. Ómdet de Bryozoa delicaat organisme zeen is 't veurkómme daovan in sedimentaire stein 'n indikaasje veur e roewig aafzèttingsmiljeu. Wen de Bryozoa hieël opgebraoke zeen (en zoea-geneumdje bioklaste vörme) is de innerzjie hoger gewaes t'n tieje vanne aafzètting.

De mosbieëster, mosbieësjkes of mosdeerkes (Letien: Bryozoa of Ectoprocta; neet te verwarre mit de waterbaerkes) vörmen 'ne stam van oermunjige (Protostomata) die veural inne zieë laeve. Zoeaget 6000 laevendje saorte zeen besjreve geworen in deze stam, worónger de vleescelpoliep en 't blaadechtig häörewier.

Dees hoeagoet 1 mm lang waterbieësjkes laeven in doeasvörmige, toet kelonies verkitje huuskes. Sómtieds vörme ze koosjten op rotsen en zieëwier. Anger saorte vertuuenen euvereinkumste mit mos, det inne struiming haer en trögk wuuertj geweeg. Aafgestorve kelonies waere döks 't strandj op geworpe, wo ze waeren aangezeen veur verdruueg zieëwier. Mosbieëster gaeven euveren algemein de veurkäör aan werm, troeapische watere, meh kómmen euvere ganse werreld veur.

Binne de geologie, en mit naam de paleontologie, zeen Bryozoa wichtige indicatore veur 't aafzèttingsmiljeu van 'n bepaoldj saort aan stein. Ómdet de Bryozoa delicaat organisme zeen is 't veurkómme daovan in sedimentaire stein 'n indikaasje veur e roewig aafzèttingsmiljeu. Wen de Bryozoa hieël opgebraoke zeen (en zoea-geneumdje bioklaste vörme) is de innerzjie hoger gewaes t'n tieje vanne aafzètting.

Mööskdiarten (Ectoprocta, Bryozoa of Polyzoa) san en stam faan diarten, diar uun't weeder lewe. Jo san böös letj, grater koloniin koon am oober sä üüb song.

Mööskdiarten (Ectoprocta, Bryozoa of Polyzoa) san en stam faan diarten, diar uun't weeder lewe. Jo san böös letj, grater koloniin koon am oober sä üüb song.

Мовести животни е заедничко име за два типа (Endoprocta и Ectoprocta) на мали и едноставни водни животни кои се хранат со помош на круна од пипала наречена лофофор и кои обично формираат прикрепени, мовести колонии. Класификацијата на овие два типа варирала во зависност од промената во мислењата за врската на мовестите животни со другите типови на животни. Авторите кои мислат дека двете групи имаат близок заеднички предок го задржуваат името Bryozoa и ги третираат ендопроктите (мовести животни кај кои устата и аналниот отвор се наоѓаат во лофофорот) и ектопроктите (мовести животни каде анусот е надвор од лофофорот) како класи. Други го користат терминот бриозои само за ектопроктите.

Ендопроктите, кои се морски форми со исклучок на еден слатководен вид, имаат глобуларно тело кое е потпрено на дршка. Лофофорот ги обиколува и устата и анусот. Се размножуваат полово и бесполово, често формирајќи колонии на поврзани индивидуи. Кај ектопроктите, кои се воглавно морски, лофофорот не го обиколува анусот. Колониите кои ектопроктите ги формираат по пат на бесполово размножуавње се со различна структура, и секој член обично има цврста заштитна покривка.

Ендопроктите и ектопроктите се ситни, често микроскопски животни кои ретко достигнуваат повеќе од 1 mm во должина. Повеќето видови живеат во плитки води, иако некои се забележани и на длабочини оф 5,500 m. Многу видови се хермафродити.

Мовести животни е заедничко име за два типа (Endoprocta и Ectoprocta) на мали и едноставни водни животни кои се хранат со помош на круна од пипала наречена лофофор и кои обично формираат прикрепени, мовести колонии. Класификацијата на овие два типа варирала во зависност од промената во мислењата за врската на мовестите животни со другите типови на животни. Авторите кои мислат дека двете групи имаат близок заеднички предок го задржуваат името Bryozoa и ги третираат ендопроктите (мовести животни кај кои устата и аналниот отвор се наоѓаат во лофофорот) и ектопроктите (мовести животни каде анусот е надвор од лофофорот) како класи. Други го користат терминот бриозои само за ектопроктите.

Ендопроктите, кои се морски форми со исклучок на еден слатководен вид, имаат глобуларно тело кое е потпрено на дршка. Лофофорот ги обиколува и устата и анусот. Се размножуваат полово и бесполово, често формирајќи колонии на поврзани индивидуи. Кај ектопроктите, кои се воглавно морски, лофофорот не го обиколува анусот. Колониите кои ектопроктите ги формираат по пат на бесполово размножуавње се со различна структура, и секој член обично има цврста заштитна покривка.

Мшанкалар (лат. Bryozoa) – шапалактуулар тибиндеги суу жандыктарынын классы. Колониялуу организмдер, колониясы дарак сымал, чанда көлөмү чоң (бир нече смге чейин). Өзүнчө особдор – зооиддерден (узундугу 1 мм дей) турат. Ар бир особдун назик алдынкы бөлүгү – полипид колониянын үстүнө бир аз чыгып турат жана бир аз дүүлүктүргөндө арткы бөлүгү – цистиддин ичине кирип кетет. Полипидинде тегереги шапалакчалар менен курчалган оозу жана жон анусу жайгашкан. Денесинин экинчилик көңдөйү (целому) жука тосмо менен арткы (дене) жана алдынкы (шапалактуу) бөлүккө бөлүнгөн. Дем алуу жана бөлүп чыгаруу системасы жок. Ичегиси илмек сымал, нерв системасы ганглийден турат, андан нервдер чыгат. Гермофродиттер, жумурткасы сууда, дене көңдөйүндө же атайын камерасында өөрчүйт. Личинкасы раковиналуу же кээ биринде жок. Личинкасы суу түбүнө түшүп, колонияны пайда кылат. Мшанкалардын 4 түркүмү, 4,5 миңдей азыркы, 1,5 миңдей тукуму курут болгон түрү белгилүү. Деңизде, чандасы тузсуз сууда жашайт.

Bryozoa (also known as the Polyzoa, Ectoprocta or commonly as moss animals)[6] are a phylum of simple, aquatic invertebrate animals, nearly all living in sedentary colonies. Typically about 0.5 millimetres (1⁄64 in) long, they have a special feeding structure called a lophophore, a "crown" of tentacles used for filter feeding. Most marine bryozoans live in tropical waters, but a few are found in oceanic trenches and polar waters. The bryozoans are classified as the marine bryozoans (Stenolaemata), freshwater bryozoans (Phylactolaemata), and mostly-marine bryozoans (Gymnolaemata), a few members of which prefer brackish water. 5,869 living species are known.[7] At least two genera are solitary (Aethozooides and Monobryozoon); the rest are colonial.

The terms Polyzoa and Bryozoa were introduced in 1830 and 1831, respectively.[8][9] Soon after it was named, another group of animals was discovered whose filtering mechanism looked similar, so it was included in Bryozoa until 1869, when the two groups were noted to be very different internally. The new group was given the name "Entoprocta", while the original Bryozoa were called "Ectoprocta". Disagreements about terminology persisted well into the 20th century, but "Bryozoa" is now the generally accepted term.[10][11]

Colonies take a variety of forms, including fans, bushes and sheets. Single animals, called zooids, live throughout the colony and are not fully independent. These individuals can have unique and diverse functions. All colonies have "autozooids", which are responsible for feeding, excretion, and supplying nutrients to the colony through diverse channels. Some classes have specialist zooids like hatcheries for fertilized eggs, colonial defence structures, and root-like attachment structures. Cheilostomata is the most diverse order of bryozoan, possibly because its members have the widest range of specialist zooids. They have mineralized exoskeletons and form single-layered sheets which encrust over surfaces, and some colonies can creep very slowly by using spiny defensive zooids as legs.

Each zooid consists of a "cystid", which provides the body wall and produces the exoskeleton, and a "polypide", which holds the organs. Zooids have no special excretory organs, and autozooids' polypides are scrapped when they become overloaded with waste products; usually the body wall then grows a replacement polypide. Their gut is U-shaped, with the mouth inside the crown of tentacles and the anus outside it. Zooids of all the freshwater species are simultaneous hermaphrodites. Although those of many marine species function first as males and then as females, their colonies always contain a combination of zooids that are in their male and female stages. All species emit sperm into the water. Some also release ova into the water, while others capture sperm via their tentacles to fertilize their ova internally. In some species the larvae have large yolks, go to feed, and quickly settle on a surface. Others produce larvae that have little yolk but swim and feed for a few days before settling. After settling, all larvae undergo a radical metamorphosis that destroys and rebuilds almost all the internal tissues. Freshwater species also produce statoblasts that lie dormant until conditions are favorable, which enables a colony's lineage to survive even if severe conditions kill the mother colony.

Predators of marine bryozoans include sea slugs (nudibranchs), fish, sea urchins, pycnogonids, crustaceans, mites and starfish. Freshwater bryozoans are preyed on by snails, insects, and fish. In Thailand, many populations of one freshwater species have been wiped out by an introduced species of snail.[12] A fast-growing invasive bryozoan off the northeast and northwest coasts of the US has reduced kelp forests so much that it has affected local fish and invertebrate populations. Bryozoans have spread diseases to fish farms and fishermen. Chemicals extracted from a marine bryozoan species have been investigated for treatment of cancer and Alzheimer's disease, but analyses have not been encouraging.[13]

Mineralized skeletons of bryozoans first appear in rocks from the Early Ordovician period,[1] making it the last major phylum to appear in the fossil record. This has led researchers to suspect that bryozoans arose earlier but were initially unmineralized, and may have differed significantly from fossilized and modern forms. In 2021, some research suggested Protomelission, a genus known from the Cambrian period, could be an example of an early bryozoan,[14] but later research suggested that this taxon may instead represent a dasyclad alga.[3] Early fossils are mainly of erect forms, but encrusting forms gradually became dominant. It is uncertain whether the phylum is monophyletic. Bryozoans' evolutionary relationships to other phyla are also unclear, partly because scientists' view of the family tree of animals is mainly influenced by better-known phyla. Both morphological and molecular phylogeny analyses disagree over bryozoans' relationships with entoprocts, about whether bryozoans should be grouped with brachiopods and phoronids in Lophophorata, and whether bryozoans should be considered protostomes or deuterostomes.

Bryozoans, phoronids and brachiopods strain food out of the water by means of a lophophore, a "crown" of hollow tentacles. Bryozoans form colonies consisting of clones called zooids that are typically about 0.5 mm (1⁄64 in) long.[15] Phoronids resemble bryozoan zooids but are 2 to 20 cm (1 to 8 in) long and, although they often grow in clumps, do not form colonies consisting of clones.[16] Brachiopods, generally thought to be closely related to bryozoans and phoronids, are distinguished by having shells rather like those of bivalves.[17] All three of these phyla have a coelom, an internal cavity lined by mesothelium.[15][16][17] Some encrusting bryozoan colonies with mineralized exoskeletons look very like small corals. However, bryozoan colonies are founded by an ancestrula, which is round rather than shaped like a normal zooid of that species. On the other hand, the founding polyp of a coral has a shape like that of its daughter polyps, and coral zooids have no coelom or lophophore.[18]

Entoprocts, another phylum of filter-feeders, look rather like bryozoans but their lophophore-like feeding structure has solid tentacles, their anus lies inside rather than outside the base of the "crown" and they have no coelom.[19]

All bryozoans are colonial except for one genus, Monobryozoon.[24][25] Individual members of a bryozoan colony are about 0.5 mm (1⁄64 in) long and are known as zooids,[15] since they are not fully independent animals.[26] All colonies contain feeding zooids, known as autozooids. Those of some groups also contain non-feeding heterozooids, also known as polymorphic zooids, which serve a variety of functions other than feeding;[25] colony members are genetically identical and co-operate, rather like the organs of larger animals.[15] What type of zooid grows where in a colony is determined by chemical signals from the colony as a whole or sometimes in response to the scent of predators or rival colonies.[25]

The bodies of all types have two main parts. The cystid consists of the body wall and whatever type of exoskeleton is secreted by the epidermis. The exoskeleton may be organic (chitin, polysaccharide or protein) or made of the mineral calcium carbonate. The body wall consists of the epidermis, basal lamina (a mat of non-cellular material), connective tissue, muscles, and the mesothelium which lines the coelom (main body cavity)[15] – except that in one class, the mesothelium is split into two separate layers, the inner one forming a membranous sac that floats freely and contains the coelom, and the outer one attached to the body wall and enclosing the membranous sac in a pseudocoelom.[27] The other main part of the bryozoan body, known as the polypide and situated almost entirely within the cystid, contains the nervous system, digestive system, some specialized muscles and the feeding apparatus or other specialized organs that take the place of the feeding apparatus.[15]

The most common type of zooid is the feeding autozooid, in which the polypide bears a "crown" of hollow tentacles called a lophophore, which captures food particles from the water.[25] In all colonies a large percentage of zooids are autozooids, and some consist entirely of autozooids, some of which also engage in reproduction.[28]

The basic shape of the "crown" is a full circle. Among the freshwater bryozoans (Phylactolaemata) the crown appears U-shaped, but this impression is created by a deep dent in the rim of the crown, which has no gap in the fringe of tentacles.[15] The sides of the tentacles bear fine hairs called cilia, whose beating drives a water current from the tips of the tentacles to their bases, where it exits. Food particles that collide with the tentacles are trapped by mucus, and further cilia on the inner surfaces of the tentacles move the particles towards the mouth in the center.[20] The method used by ectoprocts is called "upstream collecting", as food particles are captured before they pass through the field of cilia that creates the feeding current. This method is also used by phoronids, brachiopods and pterobranchs.[29]

The lophophore and mouth are mounted on a flexible tube called the "invert", which can be turned inside-out and withdrawn into the polypide,[15] rather like the finger of a rubber glove; in this position the lophophore lies inside the invert and is folded like the spokes of an umbrella. The invert is withdrawn, sometimes within 60 milliseconds, by a pair of retractor muscles that are anchored at the far end of the cystid. Sensors at the tips of the tentacles may check for signs of danger before the invert and lophophore are fully extended. Extension is driven by an increase in internal fluid pressure, which species with flexible exoskeletons produce by contracting circular muscles that lie just inside the body wall,[15] while species with a membranous sac use circular muscles to squeeze this.[27] Some species with rigid exoskeletons have a flexible membrane that replaces part of the exoskeleton, and transverse muscles anchored on the far side of the exoskeleton increase the fluid pressure by pulling the membrane inwards.[15] In others there is no gap in the protective skeleton, and the transverse muscles pull on a flexible sac which is connected to the water outside by a small pore; the expansion of the sac increases the pressure inside the body and pushes the invert and lophophore out.[15] In some species the retracted invert and lophophore are protected by an operculum ("lid"), which is closed by muscles and opened by fluid pressure. In one class, a hollow lobe called the "epistome" overhangs the mouth.[15]

The gut is U-shaped, running from the mouth, in the center of the lophophore, down into the animal's interior and then back to the anus, which is located on the invert, outside and usually below the lophophore.[15] A network of strands of mesothelium called "funiculi" ("little ropes")[30] connects the mesothelium covering the gut with that lining the body wall. The wall of each strand is made of mesothelium, and surrounds a space filled with fluid, thought to be blood.[15] A colony's zooids are connected, enabling autozooids to share food with each other and with any non-feeding heterozooids.[15] The method of connection varies between the different classes of bryozoans, ranging from quite large gaps in the body walls to small pores through which nutrients are passed by funiculi.[15][27]

There is a nerve ring round the pharynx (throat) and a ganglion that serves as a brain to one side of this. Nerves run from the ring and ganglion to the tentacles and to the rest of the body.[15] Bryozoans have no specialized sense organs, but cilia on the tentacles act as sensors. Members of the genus Bugula grow towards the sun, and therefore must be able to detect light.[15] In colonies of some species, signals are transmitted between zooids through nerves that pass through pores in the body walls, and coordinate activities such as feeding and the retraction of lophophores.[15]

The solitary individuals of Monobryozoon are autozooids with pear-shaped bodies. The wider ends have up to 15 short, muscular projections by which the animals anchor themselves to sand or gravel[31] and pull themselves through the sediments.[32]

Some authorities use the term avicularia (plural of avicularium) to refer to any type of zooid in which the lophophore is replaced by an extension that serves some protective function,[28] while others restrict the term to those that defend the colony by snapping at invaders and small predators, killing some and biting the appendages of others.[15] In some species the snapping zooids are mounted on a peduncle (stalk), their bird-like appearance responsible for the term – Charles Darwin described these as like "the head and beak of a vulture in miniature, seated on a neck and capable of movement".[15][28] Stalked avicularia are placed upside-down on their stalks.[25] The "lower jaws" are modified versions of the opercula that protect the retracted lophophores in autozooids of some species, and are snapped shut "like a mousetrap" by similar muscles,[15] while the beak-shaped upper jaw is the inverted body wall.[25] In other species the avicularia are stationary box-like zooids laid the normal way up, so that the modified operculum snaps down against the body wall.[25] In both types the modified operculum is opened by other muscles that attach to it,[28] or by internal muscles that raise the fluid pressure by pulling on a flexible membrane.[15] The actions of these snapping zooids are controlled by small, highly modified polypides that are located inside the "mouth" and bear tufts of short sensory cilia.[15][25] These zooids appear in various positions: some take the place of autozooids, some fit into small gaps between autozooids, and small avicularia may occur on the surfaces of other zooids.[28]

In vibracula, regarded by some as a type of avicularia, the operculum is modified to form a long bristle that has a wide range of motion. They may function as defenses against predators and invaders, or as cleaners. In some species that form mobile colonies, vibracula around the edges are used as legs for burrowing and walking.[15][28]

Kenozooids (from the Greek kenós 'empty')[33] consist only of the body wall and funicular strands crossing the interior,[15] and no polypide.[25] The functions of these zooids include forming the stems of branching structures, acting as spacers that enable colonies to grow quickly in a new direction,[25][28] strengthening the colony's branches, and elevating the colony slightly above its substrate for competitive advantages against other organisms. Some kenozooids are hypothesized to be capable of storing nutrients for the colony. [34] Because kenozooids' function is generally structural, they are called "structural polymorphs."

Some heterozooids found in extinct trepostome bryozoans, called mesozooids, are thought to have functioned to space the feeding autozooids an appropriate distance apart. In thin sections of trepostome fossils, mesozooids can be seen in between the tubes that held autozooids; they are smaller tubes that are divided along their length by diaphragms, making them look like rows of box-like chambers sandwiched between autozooidal tubes. [35]

Gonozooids act as brood chambers for fertilized eggs.[25] Almost all modern cyclostome bryozoans have them, but they can be hard to locate on a colony because there are so few gonozooids in one colony. The aperture in gonozooids, which is called an ooeciopore, acts as a point for larvae to exit. Some gonozooids have very complex shapes with autozooidal tubes passing through chambers within them. All larvae released from a gonozooid are clones created by division of a single egg; this is called monozygotic polyembryony, and is a reproductive strategy also used by armadillos.[36]

Cheilostome bryozoans also brood their embryos; one of the common methods is through ovicells, capsules attached to autozooids. The autozooids possessing ovicells are normally still able to feed, however, so these are not considered heterozooids. [37]

"Female" polymorphs are more common than "male" polymorphs, but specialized zooids that produce sperm are also known. These are called androzooids, and some are found in colonies of Odontoporella bishopi, a species that is symbiotic with hermit crabs and lives on their shells. These zooids are smaller than the others and have four short tentacles and four long tentacles, unlike the autozooids which have 15–16 tentacles. Androzooids are also found in species with mobile colonies that can crawl around. It is possible that androzooids are used to exchange sperm between colonies when two mobile colonies or bryozoan-encrusted hermit crabs happen to encounter one another. [38]

Spinozooids are hollow, movable spines, like very slender, small tubes, present on the surface of colonies, which probably are for defense.[39] Some species have miniature nanozooids with small single-tentacled polypides, and these may grow on other zooids or within the body walls of autozooids that have degenerated.[28]

Although zooids are microscopic, colonies range in size from 1 cm (1⁄2 in) to over 1 m (3 ft 3 in).[15] However, the majority are under 10 cm (4 in) across.[18] The shapes of colonies vary widely, depend on the pattern of budding by which they grow, the variety of zooids present and the type and amount of skeletal material they secrete.[15]

Some marine species are bush-like or fan-like, supported by "trunks" and "branches" formed by kenozooids, with feeding autozooids growing from these. Colonies of these types are generally unmineralized but may have exoskeletons made of chitin.[15] Others look like small corals, producing heavy lime skeletons.[40] Many species form colonies which consist of sheets of autozooids. These sheets may form leaves, tufts or, in the genus Thalamoporella, structures that resemble an open head of lettuce.[15]

The most common marine form, however, is encrusting, in which a one-layer sheet of zooids spreads over a hard surface or over seaweed. Some encrusting colonies may grow to over 50 cm (1 ft 8 in) and contain about 2,000,000 zooids.[15] These species generally have exoskeletons reinforced with calcium carbonate, and the openings through which the lophophores protrude are on the top or outer surface.[15] The moss-like appearance of encrusting colonies is responsible for the phylum's name (Ancient Greek words βρύον brúon meaning 'moss' and ζῷον zôion meaning 'animal').[41] Large colonies of encrusting species often have "chimneys", gaps in the canopy of lophophores, through which they swiftly expel water that has been sieved, and thus avoid re-filtering water that is already exhausted.[42] They are formed by patches of non-feeding heterozooids.[43] New chimneys appear near the edges of expanding colonies, at points where the speed of the outflow is already high, and do not change position if the water flow changes.[44]

Some freshwater species secrete a mass of gelatinous material, up to 1 m (3 ft 3 in) in diameter, to which the zooids stick. Other freshwater species have plant-like shapes with "trunks" and "branches", which may stand erect or spread over the surface. A few species can creep at about 2 cm (3⁄4 in) per day.[15]

Each colony grows by asexual budding from a single zooid known as the ancestrula,[15] which is round rather than shaped like a normal zooid.[18] This occurs at the tips of "trunks" or "branches" in forms that have this structure. Encrusting colonies grow round their edges. In species with calcareous exoskeletons, these do not mineralize until the zooids are fully grown. Colony lifespans range from one to about 12 years, and the short-lived species pass through several generations in one season.[15]

Species that produce defensive zooids do so only when threats have already appeared, and may do so within 48 hours.[25] The theory of "induced defenses" suggests that production of defenses is expensive and that colonies which defend themselves too early or too heavily will have reduced growth rates and lifespans. This "last minute" approach to defense is feasible because the loss of zooids to a single attack is unlikely to be significant.[25] Colonies of some encrusting species also produce special heterozooids to limit the expansion of other encrusting organisms, especially other bryozoans. In some cases this response is more belligerent if the opposition is smaller, which suggests that zooids on the edge of a colony can somehow sense the size of the opponent. Some species consistently prevail against certain others, but most turf wars are indecisive and the combatants soon turn to growing in uncontested areas.[25] Bryozoans competing for territory do not use the sophisticated techniques employed by sponges or corals, possibly because the shortness of bryozoan lifespans makes heavy investment in turf wars unprofitable.[25]